↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Discovering causal relationships from event sequences (e.g., stock market crashes, network outages) is crucial for understanding and predicting future events. Existing methods based on Granger causality often fail to capture delayed effects or deal effectively with noise and complex dependencies. This leads to inaccurate causal models, limiting our ability to effectively interpret and react to events.

This paper presents CASCADE, a novel algorithm that addresses these limitations. CASCADE uses a new causal model that incorporates dynamic delays and uncertainty in causal effects, leveraging the Minimum Description Length (MDL) principle to identify the true causal direction. Extensive experiments on synthetic and real-world datasets demonstrate that CASCADE significantly outperforms existing approaches, particularly in scenarios with noise, multiple colliders, and delayed effects. It efficiently recovers insightful causal graphs, shedding light on complex interactions within real-world event sequences.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in causal discovery and time series analysis. It introduces a novel causal model and algorithm (CASCADE) that effectively identifies causal relationships in event sequences, outperforming existing methods. This has broad implications for various fields dealing with temporal data, such as finance, network security, and social sciences, opening doors for advanced causal inference methodologies and improved predictive capabilities. The rigorous theoretical foundation and comprehensive experimental evaluation add significant value.

Visual Insights#

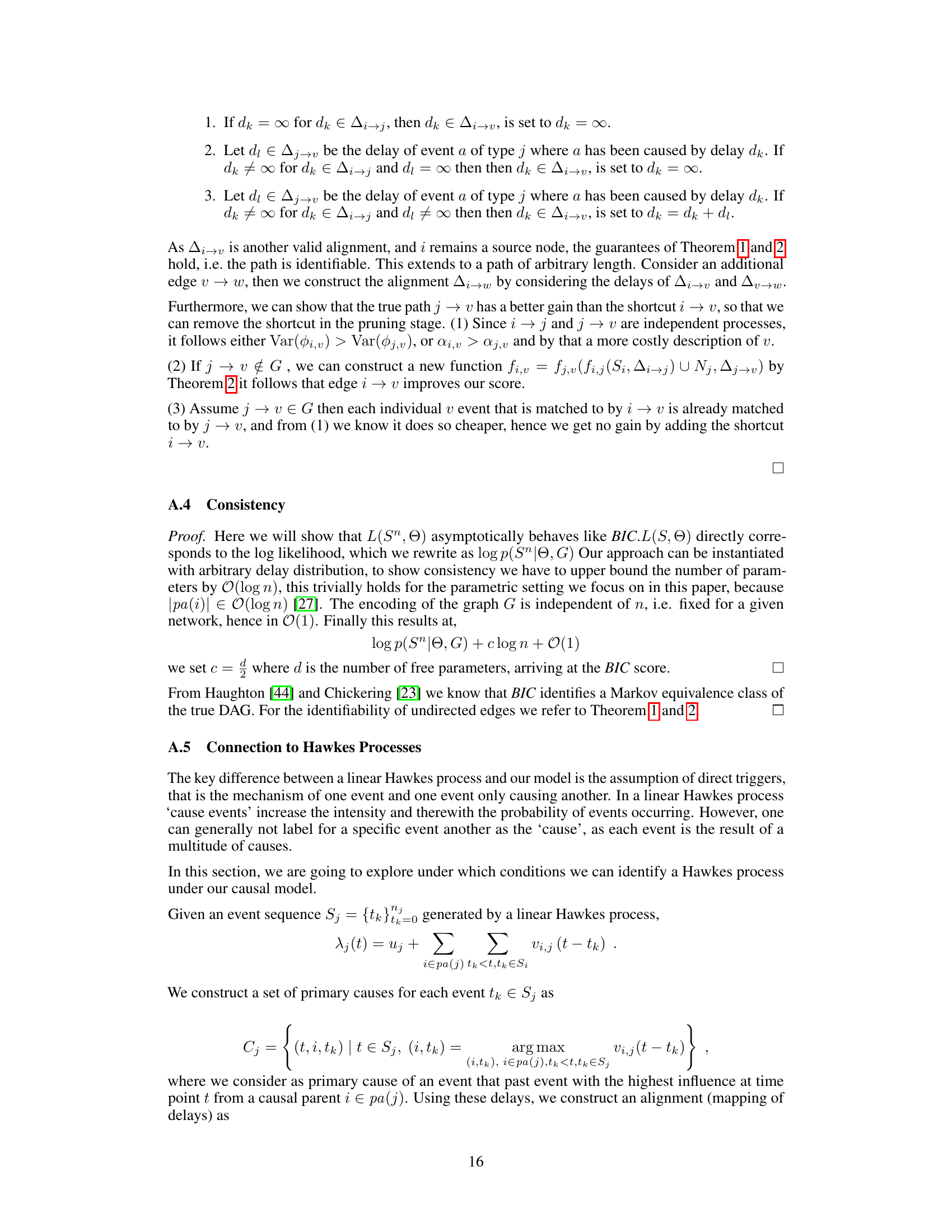

This figure illustrates a simple example of cause-effect matching between two event sequences, Si and Sj. Events in Si occur at random intervals. Some of these events (with delays of 0.2 and 0.3 time units) trigger corresponding events in Sj. Other events in Si do not trigger any events in Sj (indicated by ∞). Finally, there is a noise event in Sj (indicated by Nj). This example demonstrates the concept of dynamic delays between cause and effect events which is a core feature of the proposed causal model.

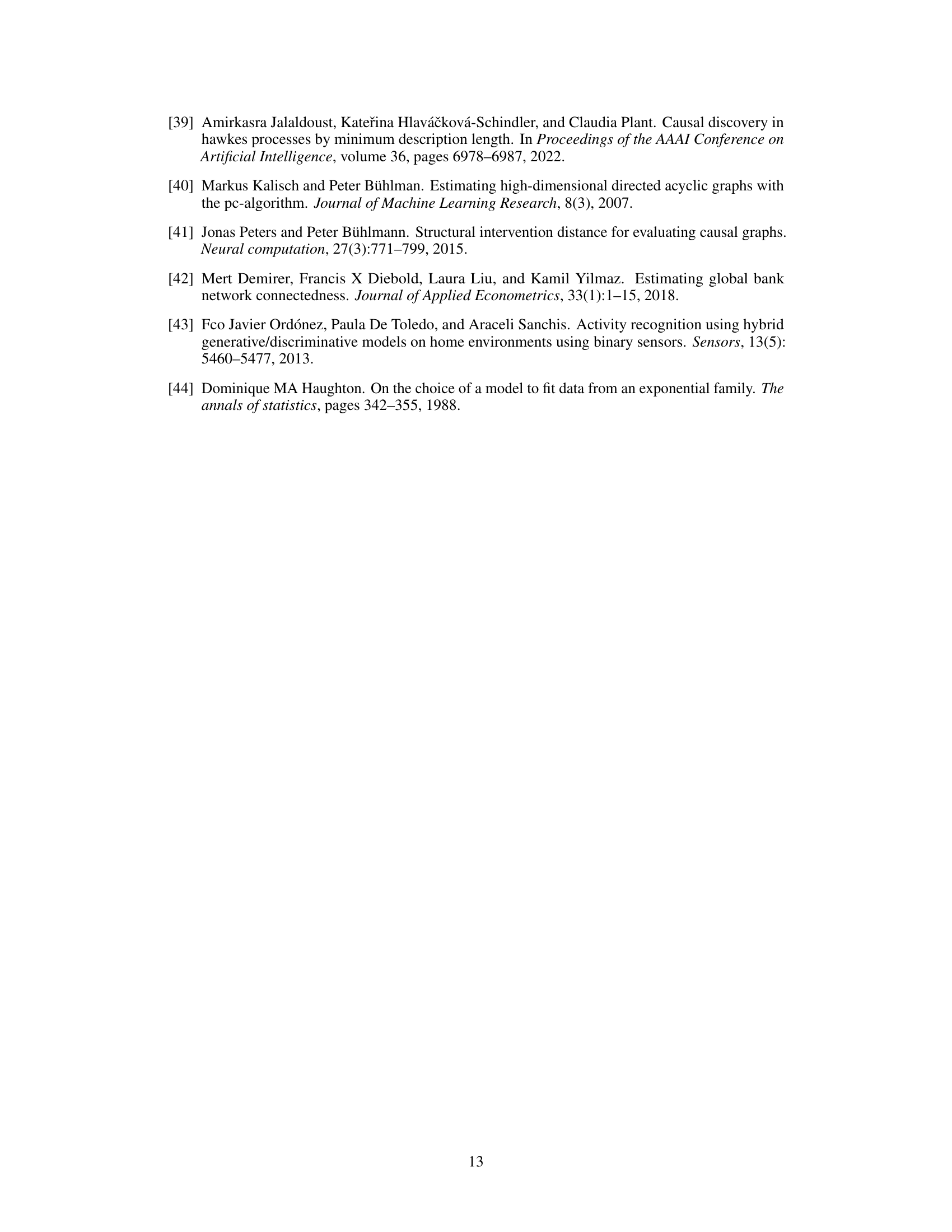

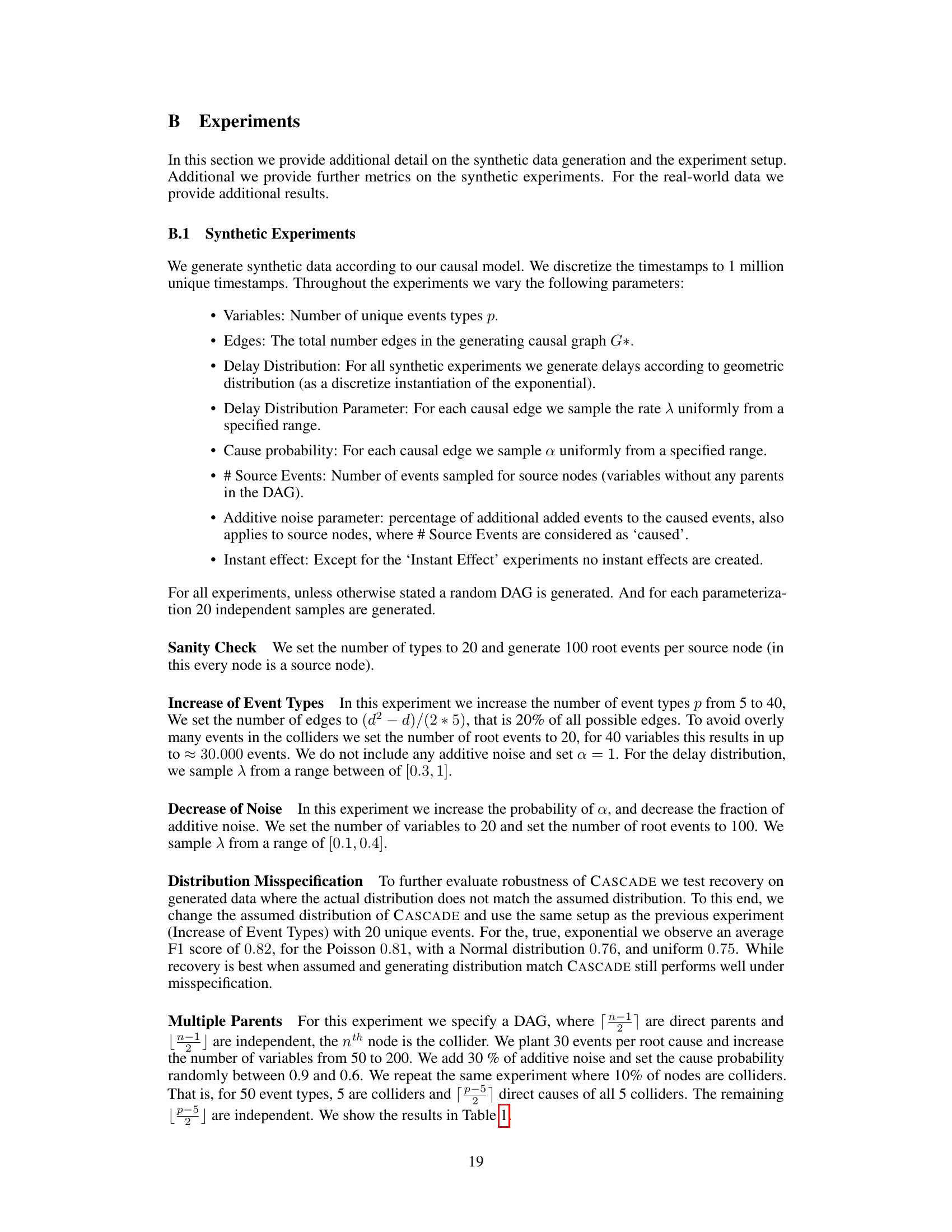

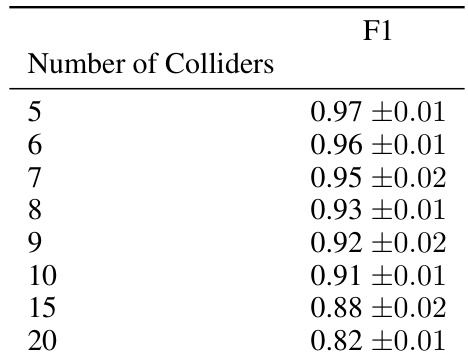

This table shows the average F1 score achieved by the CASCADE algorithm in an experiment designed to evaluate its performance under conditions with multiple colliders. The experiment manipulates the number of colliders (nodes where multiple parent nodes converge), ranging from 5 to 20. The F1 score measures the effectiveness of the algorithm in correctly identifying the causal relationships.

In-depth insights#

Causal Model#

The core of this research paper revolves around a novel causal model designed for event sequences. This model surpasses traditional Granger causality by explicitly addressing dynamic delays between cause and effect events. It tackles the inherent uncertainty in causal relationships, accounting for the possibility of events being independently generated, the chance of a cause failing to trigger an effect, and the variability of delays. This is a significant improvement, as it offers identifiability for both instantaneous and delayed effects, a critical feature often missing in previous approaches. The model’s foundation lies in the Algorithmic Markov Condition, aiming to minimize the Kolmogorov complexity. This is computationally intractable, so it uses the Minimum Description Length principle for practical implementation. The framework successfully establishes a formal connection to Hawkes processes, enhancing its theoretical robustness and practical applicability. The innovative causal model is further supported by the introduction of a novel algorithm, CASCADE, which efficiently constructs causal graphs from event sequences.

CASCADE Algo#

The CASCADE algorithm, designed for causal discovery in event sequences, presents a novel approach built upon the Algorithmic Markov Condition and Minimum Description Length principle. Its core innovation lies in iteratively adding and pruning edges based on a topological ordering, ensuring that the final causal graph is a directed acyclic graph (DAG). This topological approach enhances efficiency and avoids cycles. The algorithm’s ability to identify true causal directions for both instantaneous and delayed effects is crucial, distinguishing it from approaches solely based on Granger causality. The algorithm’s consistency is theoretically proven, demonstrating its capacity to recover the true underlying causal structure under certain conditions. While the theoretical guarantees are asymptotic, the empirical results demonstrate strong performance even in noisy settings with multiple colliders, suggesting robustness beyond the theoretical limitations. The incorporation of an MDL score enables the algorithm to quantify the strength of causal relationships, providing an additional layer of interpretability. Overall, CASCADE is presented as a significant advance in causal inference for event data, surpassing existing methods in certain conditions, and offering a principled and efficient pathway for uncovering cause-and-effect relationships.

Hawkes Processes#

The section on Hawkes processes reveals a crucial comparison between the proposed causal model and existing methods using Hawkes processes for event sequence analysis. Hawkes processes offer an analytically convenient framework for modeling events that trigger subsequent events, a characteristic often found in real-world scenarios like cascading network failures or stock market crashes. The authors highlight that existing Granger causality-based approaches frequently rely on Hawkes processes, but these methods are limited in their ability to identify true causal relationships, particularly when dealing with instantaneous effects or complex dependencies. In contrast, the new model proposed directly addresses the limitations of Granger causality by explicitly modeling the probability of one event causing another with associated dynamic delays, making it superior in discerning true causal directions and handling both instant and delayed effects. This distinction emphasizes a key advantage of the novel model, providing a more accurate representation of causal mechanisms within event sequences and offering improved identifiability of causal structures.

Real-World Data#

The ‘Real-World Data’ section of a research paper is crucial for validating the model’s generalizability and practical applicability. A thoughtful analysis would assess the datasets chosen: were they diverse and representative of the real-world scenarios the model intends to address? A lack of diversity could limit the inferences drawn. The evaluation metrics employed are also key: do they appropriately capture the performance characteristics relevant to the application context? Simple accuracy might be insufficient; a deeper dive into precision, recall, F1-score, or AUC, coupled with domain-specific metrics, is necessary. Finally, a clear and detailed description of the data preprocessing steps is needed to ensure reproducibility and evaluate the impact of any potential biases introduced during this phase. The overall goal is to demonstrate that the model’s findings are reliable and practically relevant, not just theoretically sound.

Future Work#

The ‘Future Work’ section of this research paper presents exciting avenues for extending the current causal discovery model. Exploring ‘and’ relations, instead of the current ‘or’ relations between causal variables, would significantly enhance the model’s ability to capture complex interactions where multiple conditions must be met to trigger an effect. This requires careful consideration of temporal proximity and ordering of events. Addressing the limitations of the current one-to-one event matching is crucial, as it currently restricts modeling scenarios involving single-cause multiple-effects or multiple-causes single-effect. Investigating techniques to handle these situations will greatly expand the applicability of the model to real-world systems. Further theoretical investigation into the identifiability conditions will improve the model’s robustness and reliability. Extending the model to incorporate counterfactual analysis would offer powerful insights into the causal mechanisms, allowing researchers to explore hypothetical scenarios. Finally, applying the method to a wider array of real-world datasets across diverse domains would validate its efficacy and uncover new insights into causal structures in various settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

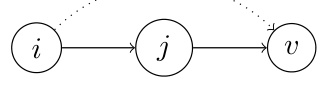

This figure is a simple illustration of the cause-effect matching concept used in the paper. It shows two event sequences, Sᵢ and Sj. Events in Sᵢ occur at random intervals, and some of these events cause events in Sj with a certain delay. The figure visually represents the uncertainty of whether an event actually causes an effect or not, as well as the variability in the delay between cause and effect.

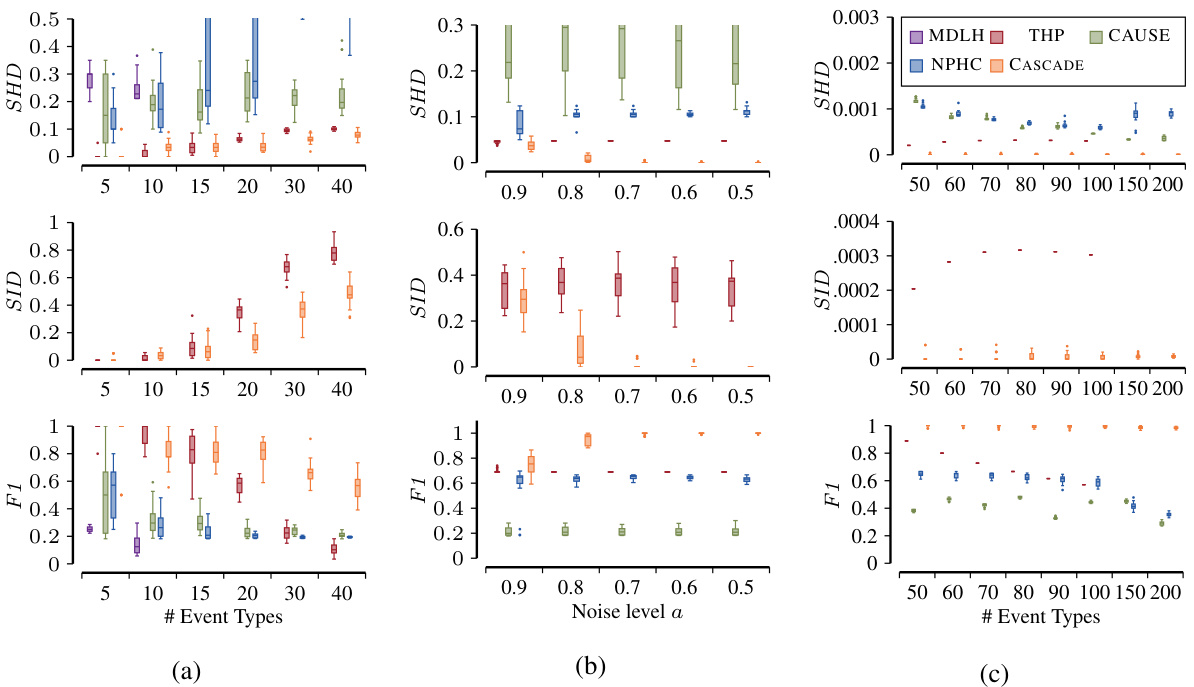

This figure displays the results of DAG recovery experiments under various conditions, using the CASCADE algorithm. It shows the normalized Structural Hamming Distance (SHD), normalized Structural Intervention Distance (SID), and F1 score. The three subfigures (a), (b), and (c) demonstrate the algorithm’s performance with varying numbers of event types, noise levels, and numbers of collider parents, respectively. CASCADE shows strong performance across all settings, outperforming other methods in terms of accurately recovering the true causal graph.

This figure shows the performance of the CASCADE algorithm on datasets generated using a Hawkes process, where the intensity of the excitation function (the expected number of events generated per cause) is varied. The results demonstrate that CASCADE performs best when its assumptions hold (one effect per cause or fewer), but maintains strong performance across a range of settings.

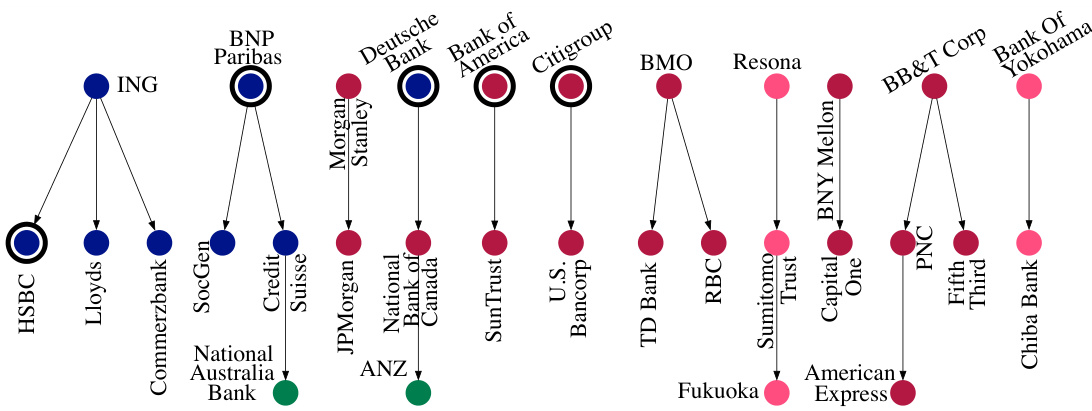

This figure shows the largest subgraph discovered by the CASCADE algorithm when applied to the Global Banks dataset. The nodes represent banks, and the edges represent causal relationships between them. The 10 largest banks (by assets) are highlighted. The figure demonstrates that CASCADE not only identifies causal relationships but also reveals geographic locality and the disproportionate influence of larger banks, information that was not explicitly provided in the input data.

This figure shows the performance of the CASCADE algorithm in recovering the true DAG structure on data generated by a Hawkes process. The x-axis represents the expected number of events generated per cause (intensity of the excitation function). The y-axis represents the F1 score, a measure of the accuracy of the recovered DAG. The box plot shows the distribution of F1 scores across multiple runs for each intensity level. The plot demonstrates how the algorithm’s performance varies with different levels of intensity of the Hawkes process.

This figure presents the results of synthetic experiments comparing the performance of different causal discovery methods. The methods are evaluated using three metrics: Structural Hamming Distance (SHD), Structural Intervention Distance (SID), and F1 score. The x-axis represents different experimental conditions, such as the number of event types, the level of noise in the data, and the number of colliders (variables that are both a cause and an effect). The y-axis represents the values of each metric for different methods. The results show that CASCADE generally outperforms other methods, especially in challenging settings with high noise or many colliders.

The figure shows the causal graphs discovered by the CASCADE algorithm on two datasets of daily activities. Subfigure (a) shows a relatively simple graph with clear causal relationships between daily events such as showering, grooming, and sleeping. Subfigure (b) depicts a more complex graph with more intricate dependencies between these events and others like eating and spending spare time/watching TV.

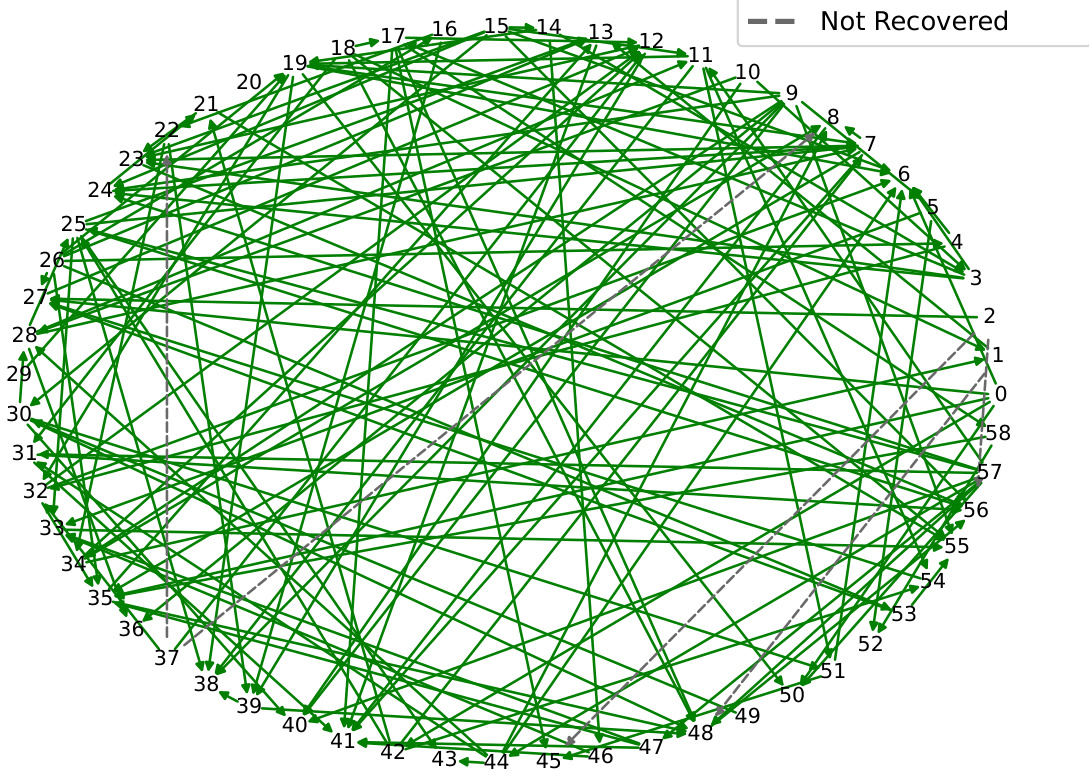

This figure shows the causal graph recovered by the CASCADE algorithm on a real-world dataset of network alarms. The nodes represent different types of alarms, and the edges represent causal relationships between them. The green edges represent correctly recovered causal relationships, while the gray dashed lines represent causal relationships that were not recovered. The figure visually depicts the algorithm’s performance in identifying causal connections within the complex network alarm data.

This figure shows the largest subgraph discovered by the CASCADE algorithm when applied to the Global Banks dataset. The nodes represent banks, with the 10 largest banks highlighted. The edges represent causal relationships between banks’ daily return volatility. The graph demonstrates that CASCADE not only identifies causal relationships but also captures geographical locality (e.g., clustering of banks within regions) and the disproportionate influence of larger banks on the overall market, information not present in the input data.

This figure shows the largest subgraph discovered by the CASCADE algorithm when applied to a dataset of global banks. The 10 largest banks are highlighted, demonstrating that CASCADE successfully identifies geographical clusters and the disproportionate influence of larger banks on the market, information not present in the input data.

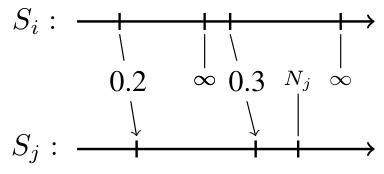

More on tables

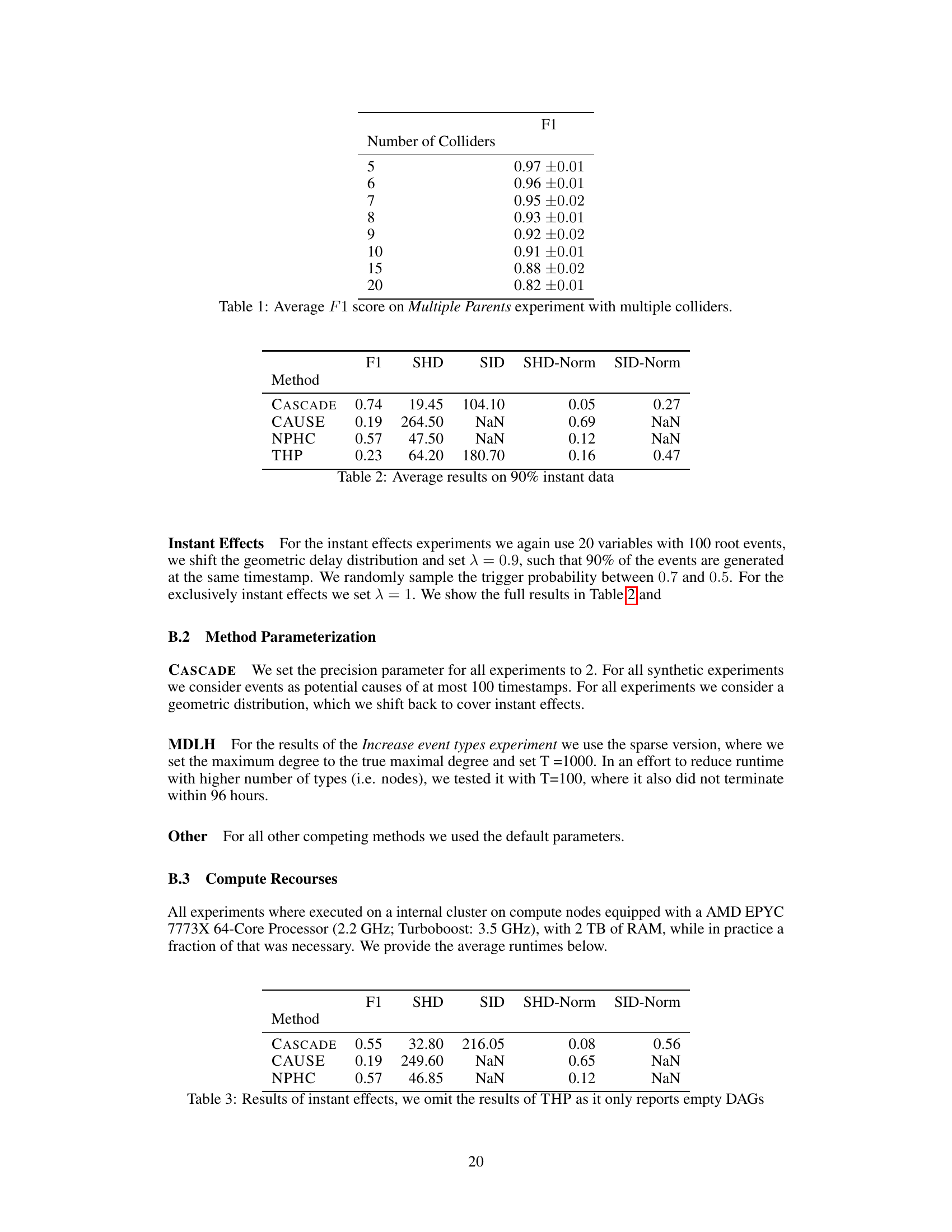

This table shows the performance of four different causal discovery methods (CASCADE, CAUSE, NPHC, and THP) on a dataset where 90% of the causal effects are instantaneous. The metrics used for evaluation include F1 score (a measure of accuracy), SHD (Structural Hamming Distance, which measures the difference in graph structure), SID (Structural Intervention Distance, which quantifies the difference in causal effects), and normalized versions of SHD and SID. The NaN values likely indicate that a particular method did not produce a DAG (directed acyclic graph) which is needed for SID calculation. The results suggest that CASCADE outperforms the other methods in this setting.

This table presents the average results for four different methods (CASCADE, CAUSE, NPHC, and THP) on a dataset where 90% of the causal effects are instantaneous. The metrics used for evaluation are F1 score, Structural Hamming Distance (SHD), Structural Intervention Distance (SID), normalized SHD, and normalized SID. The NaN values likely indicate that a specific metric could not be calculated for that method due to the structure of the DAGs recovered.

This table presents the average runtime (in seconds) for the ‘Increase of Event Types’ experiment. It shows how the runtime of different causal discovery methods (CASCADE, CAUSE, NPHC, THP, MDLH) varies with the number of event types (5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40). The results highlight the scalability of each method, showing how runtime increases as the number of event types grows. Note that MDLH did not finish within the allocated time for experiments with more than 10 event types.

This table presents the average runtime in seconds for different algorithms (CASCADE, CAUSE, NPHC, THP) under varying noise levels (0.10 to 0.90). It demonstrates how the runtime of each algorithm changes as the amount of noise in the data increases. The results highlight the relative computational efficiency or scalability of the different methods.

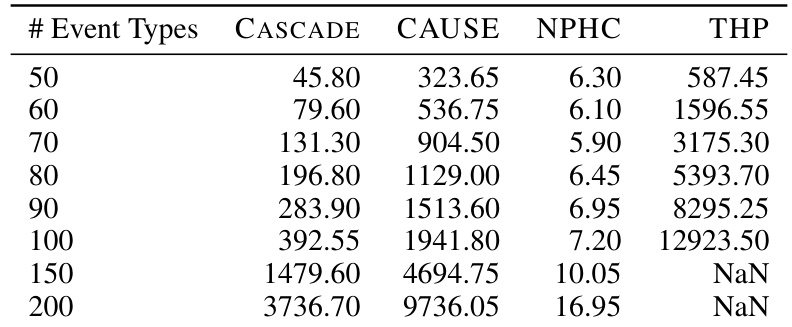

This table shows the runtime of different causal discovery methods (CASCADE, CAUSE, NPHC, THP) on synthetic datasets with varying numbers of event types. The experiment involves increasing the number of event types from 50 to 200, while introducing colliders in the causal graph to make the causal discovery more challenging. The results show the mean runtime in seconds for each method and event type. Note that THP and MDLH did not complete within the allotted time for larger datasets.

Full paper#