↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current methods for robot manipulation often struggle with limited data and fail to fully exploit relationships between visual observations and actions. This leads to suboptimal performance. VidMan addresses these challenges by using large-scale video data to improve the stability and efficiency of robot learning.

VidMan uses a two-stage training approach inspired by neuroscience’s dual-process theory. The first stage pre-trains a model on a large video dataset to learn complex dynamics, enabling long-horizon awareness. The second stage adapts this model to predict actions precisely, leveraging implicit knowledge learned in the first stage. The results demonstrate significant improvements in robot manipulation tasks, outperforming state-of-the-art methods and achieving high precision gains.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel framework for improving robot manipulation using video diffusion models. This approach offers a significant advancement over existing methods by effectively leveraging both visual and implicit dynamics knowledge, leading to more precise and robust robot actions. The two-stage training paradigm offers a new avenue for data efficient robot learning and is highly relevant to current research trends in deep learning, robotics, and computer vision. The public availability of code and models enhances reproducibility and facilitates further investigation.

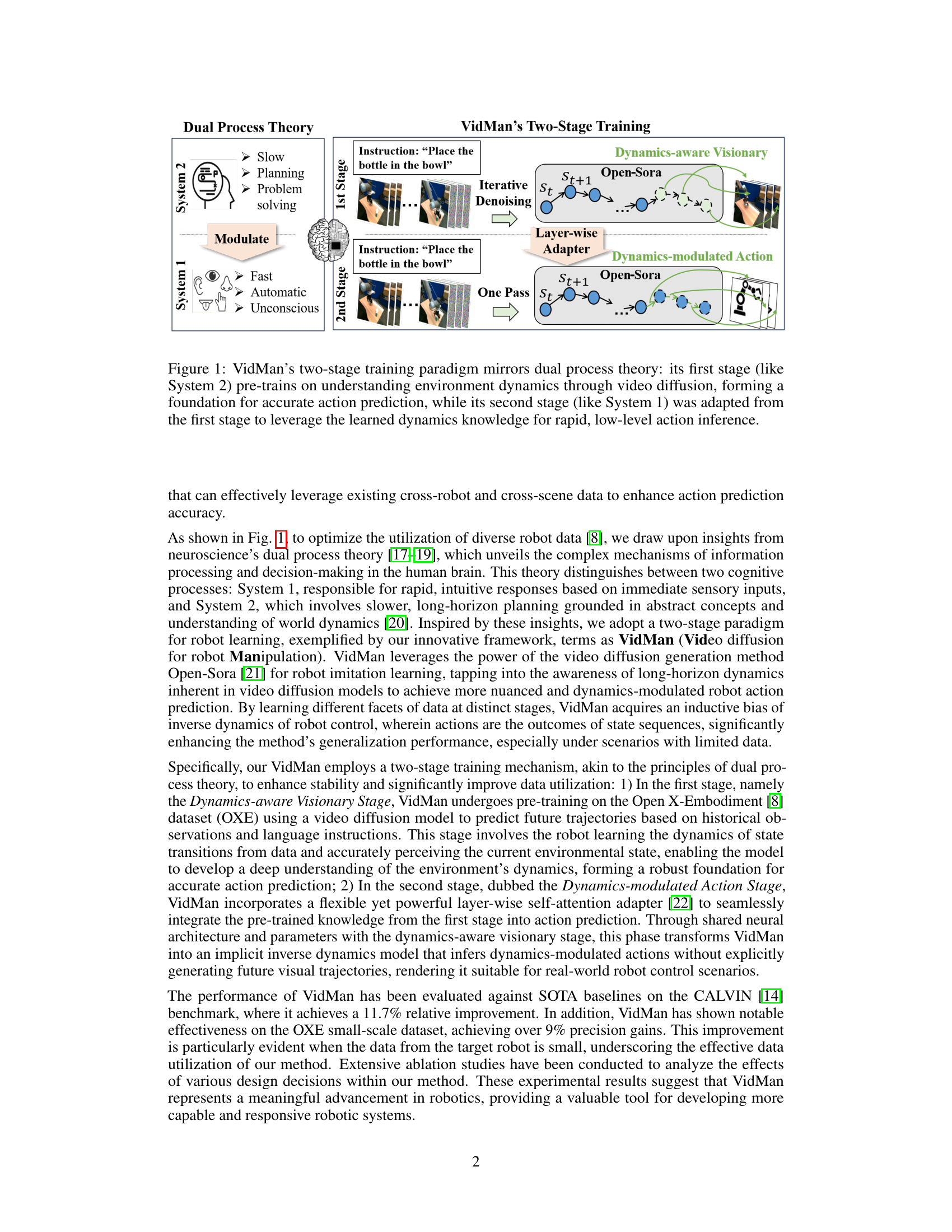

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates VidMan’s two-stage training process, drawing an analogy to the dual-process theory in neuroscience. The first stage, akin to System 2 (slow, deliberate processing), pre-trains a video diffusion model on a large dataset to learn environmental dynamics. This provides a strong foundation for action prediction. The second stage, mirroring System 1 (fast, intuitive responses), adapts the pre-trained model using a lightweight adapter for rapid action prediction, leveraging the learned dynamics knowledge. The diagram visually depicts this process, showing the iterative denoising of the first stage and the streamlined single-pass process of the second stage, highlighting the parameter sharing between the stages.

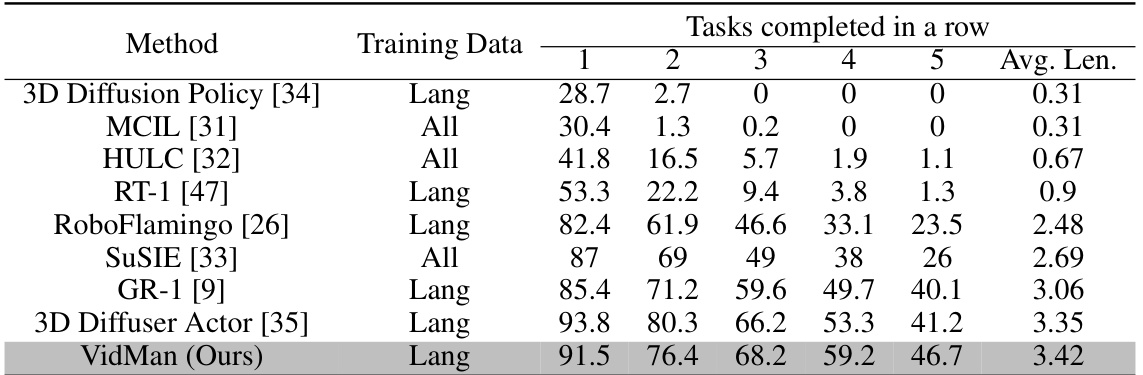

This table presents a comparison of VidMan’s performance against several baseline methods on the CALVIN benchmark. The benchmark involves zero-shot long-horizon tasks where models are trained on subsets of the data and tested on unseen data. The table shows the average number of tasks successfully completed in a row, indicating the model’s ability to perform sequential tasks. The results demonstrate VidMan’s superior performance compared to other methods, particularly in handling long sequences of tasks.

In-depth insights#

VidMan Framework#

The VidMan framework presents a novel two-stage training approach for effective robot manipulation, drawing inspiration from neuroscience’s dual-process theory. Stage one, a pre-training phase on a large-scale video dataset (OXE), employs a video diffusion model to develop a robust understanding of environmental dynamics. This allows VidMan to build a long-horizon awareness of the environment’s dynamics, which serves as an inductive bias, facilitating the creation of more accurate action predictions. Stage two introduces a lightweight adapter that transforms the pre-trained model into an efficient inverse dynamics model, predicting actions modulated by the learned dynamics. This two-stage approach contrasts with traditional methods that directly train on often limited robot data, resulting in improved stability and data efficiency. Parameter sharing between the two stages efficiently leverages the knowledge gained from the pre-training phase, enhancing the model’s generalization and performance, particularly in low-data scenarios. VidMan’s effectiveness is demonstrated through superior performance on benchmark datasets compared to state-of-the-art methods. The use of video diffusion modeling is a particularly compelling aspect, offering an alternative to standard methods. The framework also showcases a notable advancement in leveraging cross-robot and cross-scene data, making it promising for real-world applications.

Dual-Stage Training#

The paper proposes a novel dual-stage training approach, inspired by the dual-process theory in neuroscience, to effectively leverage video data for robot manipulation. The first stage focuses on pre-training a video diffusion model using a large-scale dataset, enabling the model to develop a deep understanding of environmental dynamics. This stage emphasizes learning long-horizon dependencies and establishing a strong foundation for action prediction. The second stage involves adapting this pre-trained model using a lightweight self-attention adapter. This adapter seamlessly integrates the learned dynamics into an inverse dynamics model, allowing for efficient and accurate action prediction. This two-stage approach cleverly addresses data scarcity issues in robotics by first building a robust world model, and then efficiently mapping this knowledge to robot actions. The division of labor between stages enhances stability and improves data utilization efficiency. By decoupling the understanding of the environment (stage 1) and the task of executing actions (stage 2), the framework shows improvements in robot action prediction across multiple benchmarks.

Inverse Dynamics#

Inverse dynamics, a crucial concept in robotics and control theory, focuses on determining the control inputs (e.g., forces, torques) necessary to achieve a desired motion or behavior. Unlike forward dynamics, which predicts future states given current states and inputs, inverse dynamics solves for the inputs that will produce a desired outcome. This is particularly important in robot manipulation tasks where precise control is needed to interact with objects in the environment. Challenges in inverse dynamics include the inherent non-linearity of robotic systems, the presence of noise and disturbances, and the computational cost associated with solving complex equations. However, advancements in machine learning are providing new approaches to estimate inverse dynamics models, particularly through data-driven methods that learn from robot trajectory data. Data-driven methods often bypass the need to explicitly model the robot’s complex physical dynamics, instead learning a mapping from desired states and actions to the required inputs. Although these methods are promising, careful consideration must be given to data quality, model generalizability and the handling of noisy or incomplete data.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model or method to assess their individual contributions. In this context, a well-designed ablation study would systematically remove parts of the VidMan framework, such as the two-stage training, the video diffusion model, the layer-wise adapter, or different components of the training data, to isolate the effect of each component on performance. The results would then reveal which aspects are crucial for the model’s success and which aspects are less important or even detrimental. The effectiveness of the two-stage training paradigm, the value of the pre-training on a large-scale video dataset, the impact of the layer-wise adapter in bridging the two stages, and the effect of incorporating language instructions would be evaluated through this process. By carefully controlling the variables, the ablation analysis helps pinpoint the essential features of VidMan that enable its strong performance, and potentially guide future improvements by highlighting areas for further refinement or alternative designs.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for VidMan could center on enhancing its 3D perception capabilities, moving beyond reliance on 2D visual data for more robust and nuanced environment understanding. Integrating advanced language models like LLMs would improve instruction comprehension and allow VidMan to tackle more complex, multi-step tasks. Improving data efficiency is another crucial area: exploring techniques to further leverage limited robotic datasets or even synthesizing more data for training could significantly enhance performance. Finally, exploring the integration of various sensor modalities, such as proprioception and force sensing, beyond vision, would make VidMan a more complete and adaptable system for diverse real-world robotics applications. This multi-modal approach would lead to more resilient and robust action prediction, enabling even more capable robotic systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

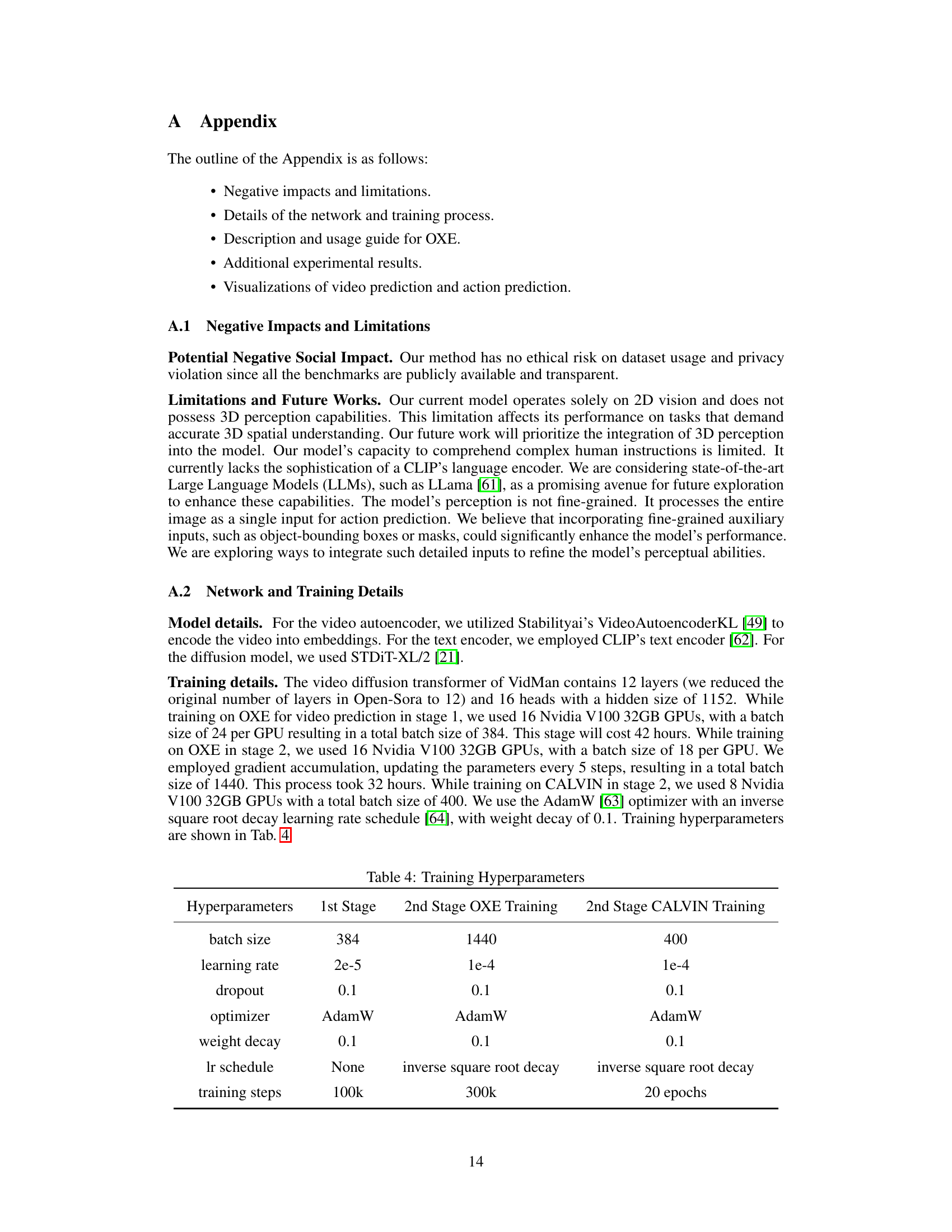

This figure provides a visual overview of the VidMan architecture. It’s divided into two stages, mirroring the dual-process theory. The first stage pre-trains a video diffusion model (Open-Sora) using robot visual trajectories to understand environment dynamics. The second stage uses a layer-wise adapter to integrate this learned knowledge into an action prediction head, allowing for the prediction of dynamics-modulated actions. The diagram showcases the data flow, from video tokenization and language encoding through the two stages, to final action prediction.

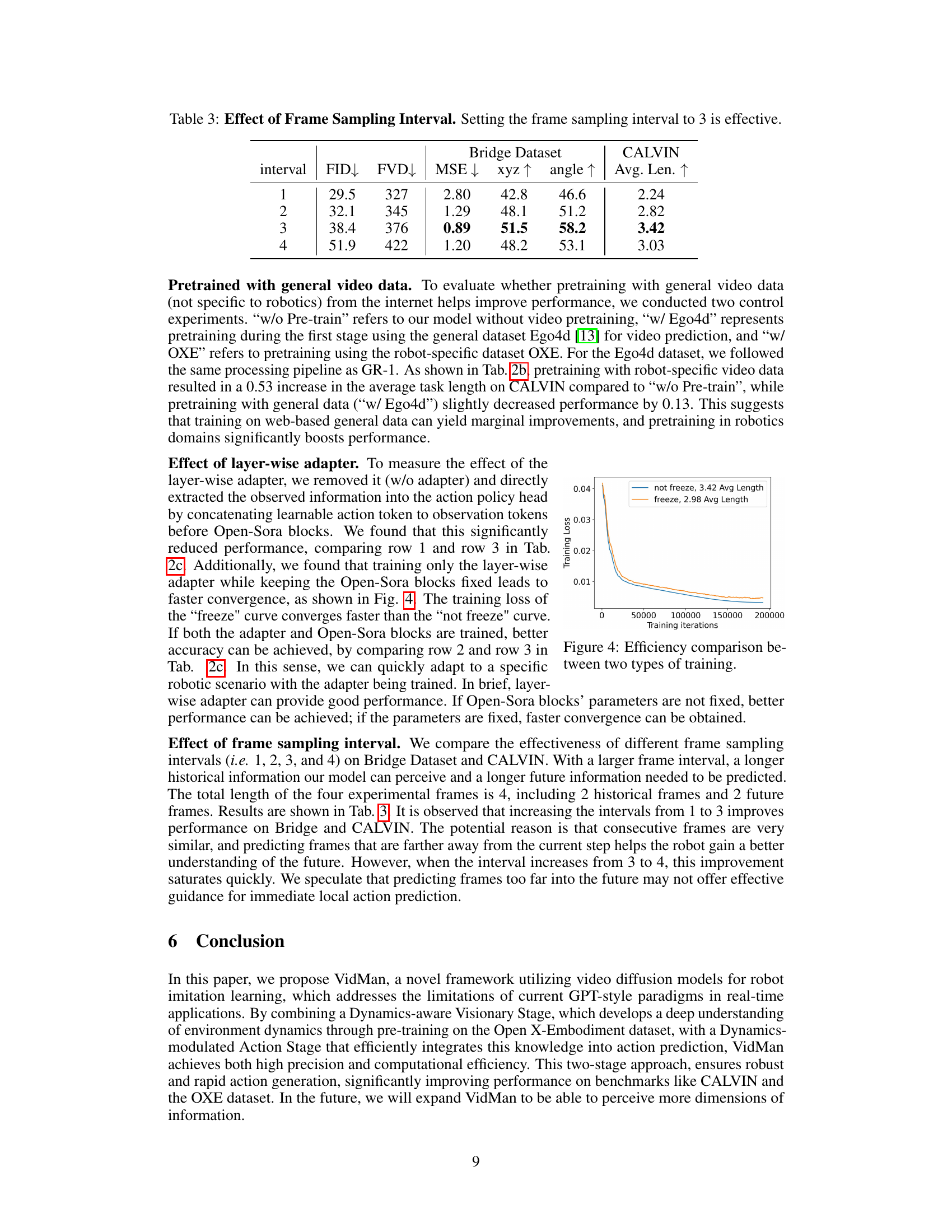

This figure shows the training loss curves for two different training strategies. The ’not freeze’ curve represents training both the layer-wise adapter and the Open-Sora blocks, while the ‘freeze’ curve represents training only the adapter with the Open-Sora blocks frozen (weights fixed). The x-axis represents training iterations, and the y-axis represents the training loss. The results indicate that training only the adapter results in faster convergence (loss decreasing more quickly), but training both components achieves slightly better overall performance (lower final loss and higher average task length, indicated in the legend).

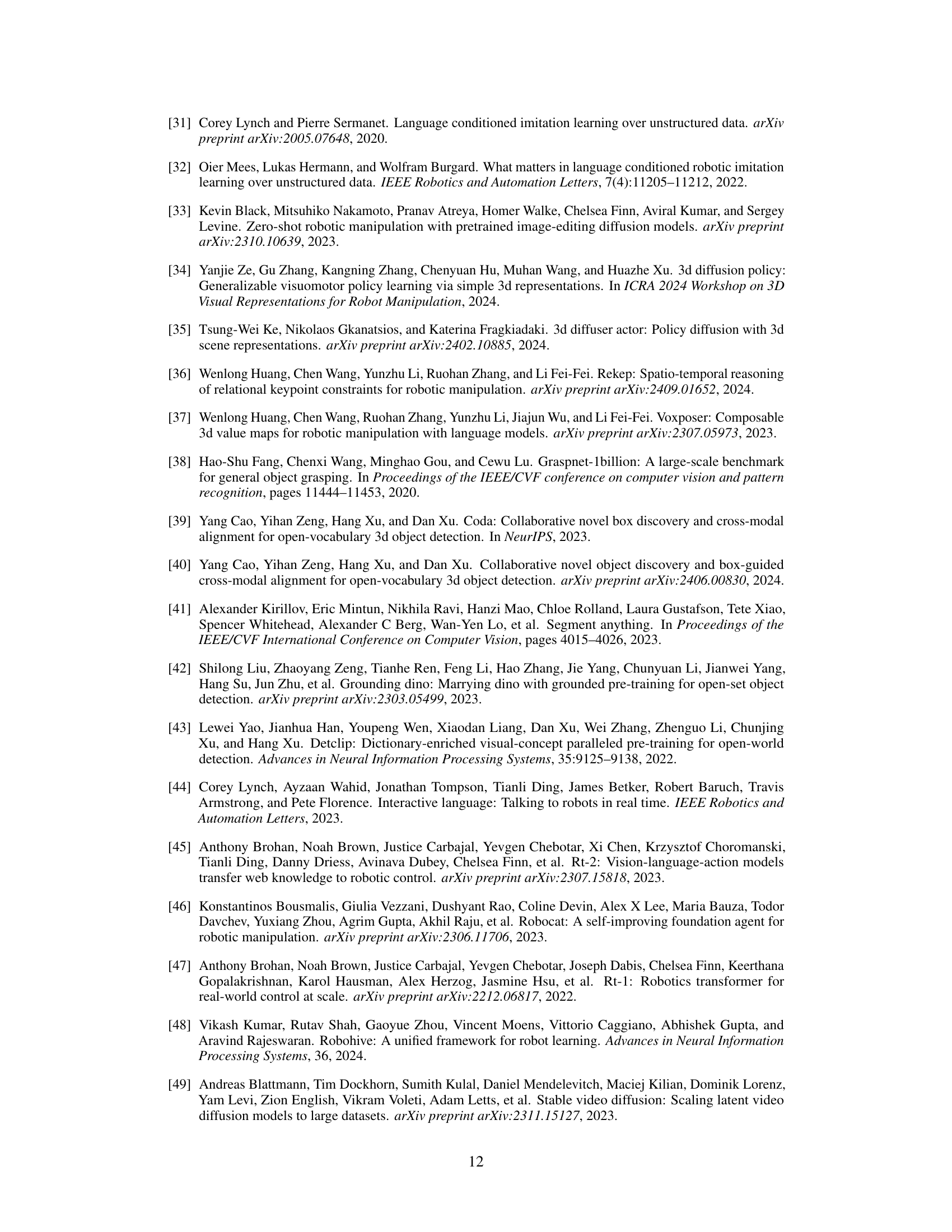

This figure shows the architecture of the layer-wise adapter used in VidMan’s second stage (Dynamics-modulated Action Stage). The adapter takes as input the outputs from each layer of the pretrained Open-Sora video diffusion model. It consists of a self-attention layer and a feed-forward network (FFN), both employing tanh gating to integrate information effectively. The adapter’s output is then used to generate action queries, which are crucial for the model’s ability to predict robot actions guided by learned dynamics.

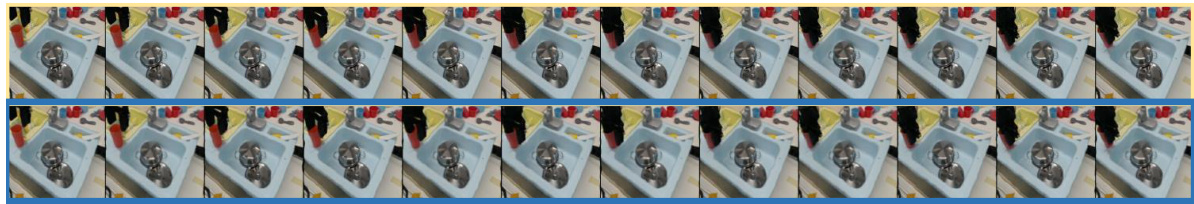

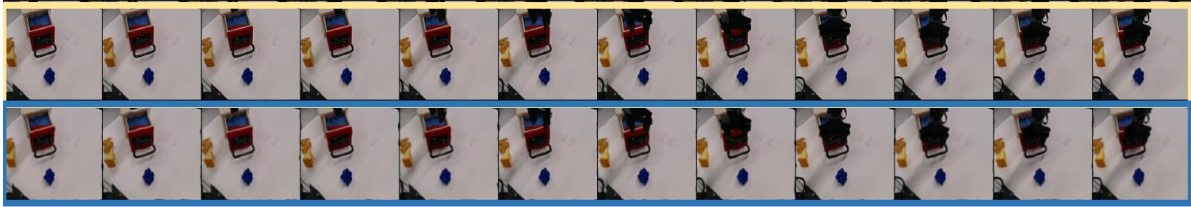

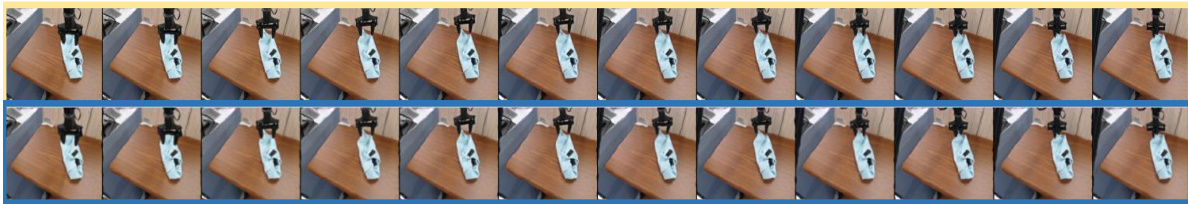

This figure shows six examples of video prediction results from the VidMan model trained on the Open X-Embodiment (OXE) dataset. Each example includes a language instruction and a sequence of images showing ground truth and predicted future frames. The model successfully predicts future image frames, although with some inaccuracies and limitations such as missing occluded objects. The figure demonstrates the model’s ability to understand and predict future frames based on the observed states and language instructions.

This figure shows several examples of video prediction results from VidMan on the OXE dataset. Each row represents a different instruction. The top half of each row shows the actual video frames (ground truth), and the bottom half shows the video frames predicted by the model. The model is capable of producing video sequences that align with the given instructions, although it does have some limitations in detail and occlusions.

This figure shows six examples of video prediction results from the VidMan model trained on the OXE dataset. Each example includes a short language instruction (e.g., ‘put cup from anywhere into sink’) and a sequence of images. The top row in each example shows the ground truth image sequence, while the bottom row shows the sequence of images predicted by VidMan. The figure demonstrates the model’s ability to predict future video frames based on language instructions and previous frames. Note that while the model generally captures the main action, fine details may not be perfectly accurate in the predicted images.

This figure visualizes the video prediction capabilities of the VidMan model. It shows several examples of video prediction tasks, each with the input language instruction at the bottom. The top row of images in each example shows the ground truth frames, while the bottom row shows the frames predicted by VidMan. The figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generate realistic and temporally coherent video sequences from language instructions, though it also shows some limitations in predicting fine details, such as occluded objects.

This figure shows six examples of video prediction results obtained using VidMan on the OXE dataset. Each example includes a language instruction (e.g., ‘put cup from anywhere into sink’) and a sequence of images. The images in the yellow boxes represent the ground truth, while the images in the blue boxes are the predictions made by the model. The figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generate realistic and coherent video sequences based on the given instructions. The predictions generally capture the essence of the actions described but may sometimes miss fine details.

This figure showcases the video prediction capabilities of the VidMan model. It presents several examples of video sequences, where the top row in each example shows the ground truth frames from the OXE dataset, and the bottom row displays the frames predicted by VidMan. Each example is accompanied by a language instruction that guides the prediction. The figure visually demonstrates the model’s ability to generate plausible future video frames based on past observations and natural language instructions.

This figure shows the video prediction results of Vidman on the OXE dataset. Each row presents a specific language instruction given to the robot. The yellow boxes highlight the ground truth image frames from the video, while the blue boxes display the corresponding frames predicted by the model. This visually demonstrates VidMan’s ability to predict future video frames based on the given language instruction and previous frames. The quality of the predictions varies; while some details are accurately captured, others, such as occluded objects, are sometimes missing. This showcases both the strengths and limitations of the model’s video prediction capabilities, underscoring that although it effectively predicts future scenarios, more complex details might be missed.

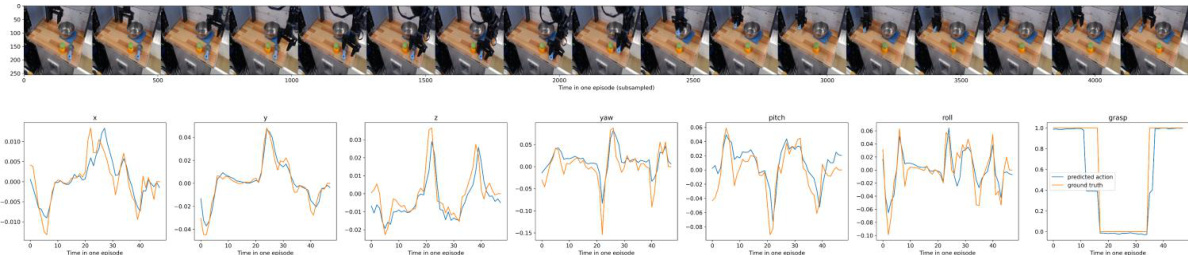

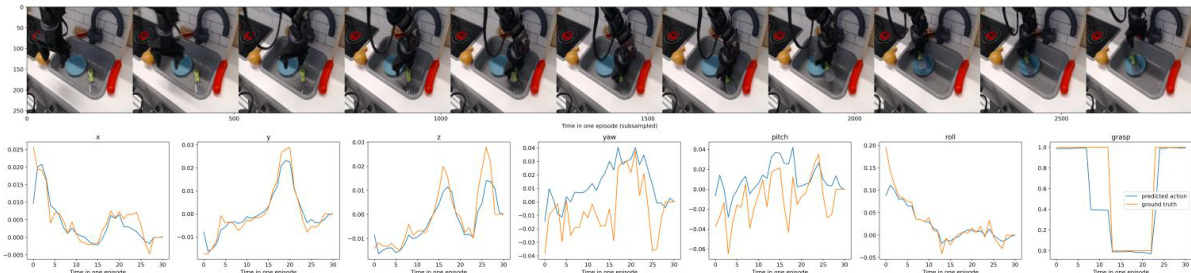

This figure visualizes the results of offline action prediction experiments conducted using the VidMan model on the Open X-Embodiment (OXE) dataset. It shows several example tasks, with the top of each section displaying a sequence of images from a single trial, and the bottom showing graphs of ground truth versus predicted robot movements (x, y, yaw, pitch, roll, and grasp) over time. The graphs clearly demonstrate the accuracy of VidMan’s action prediction, illustrating its capacity to generate precise and realistic actions for the robot.

This figure shows the results of offline action prediction on the OXE dataset. Each row represents a different action, with the top showing a sequence of images (subsampled frames) from a single episode and the bottom showing graphs of the predicted and ground truth 7D poses (x, y, yaw, pitch, roll, and grasp) over time for that same action. The figure visually demonstrates the model’s ability to predict the robot’s actions accurately in various scenarios.

This figure shows the results of offline action prediction on the OXE dataset. The top of each section displays a series of images from a single episode, showing the robot’s progress through a task. The bottom section shows a graph that compares the actual robot movements (ground truth) to the movements predicted by VidMan model. The graphs show the movement of the end-effector, including its x, y, z position, yaw, pitch, roll, and the state of the gripper (open or closed). It demonstrates VidMan’s accuracy in predicting robot movements during the execution of offline tasks.

This figure visualizes the results of offline action prediction on the OXE dataset. For several example actions (e.g., ‘Flip orange pot upright in sink’), the top portion shows a sequence of images from the episode, and the bottom portion compares the ground truth 7D robot pose (x, y, yaw, pitch, roll, and grasp) to the model’s predictions over time. The comparison allows for a visual assessment of the model’s accuracy in predicting the robot’s actions.

This figure visualizes the offline action prediction results of the VidMan model on the OXE dataset. It presents a series of image sequences showing robot arm movements in various tasks, each accompanied by a graph comparing the predicted and ground truth 7D poses (x, y, yaw, pitch, roll, and grasp) over time. The images show the model successfully predicting the robot’s actions, but with minor discrepancies in specific parameters. The graphs help quantify the accuracy of VidMan’s predictions in a quantitative manner.

More on tables

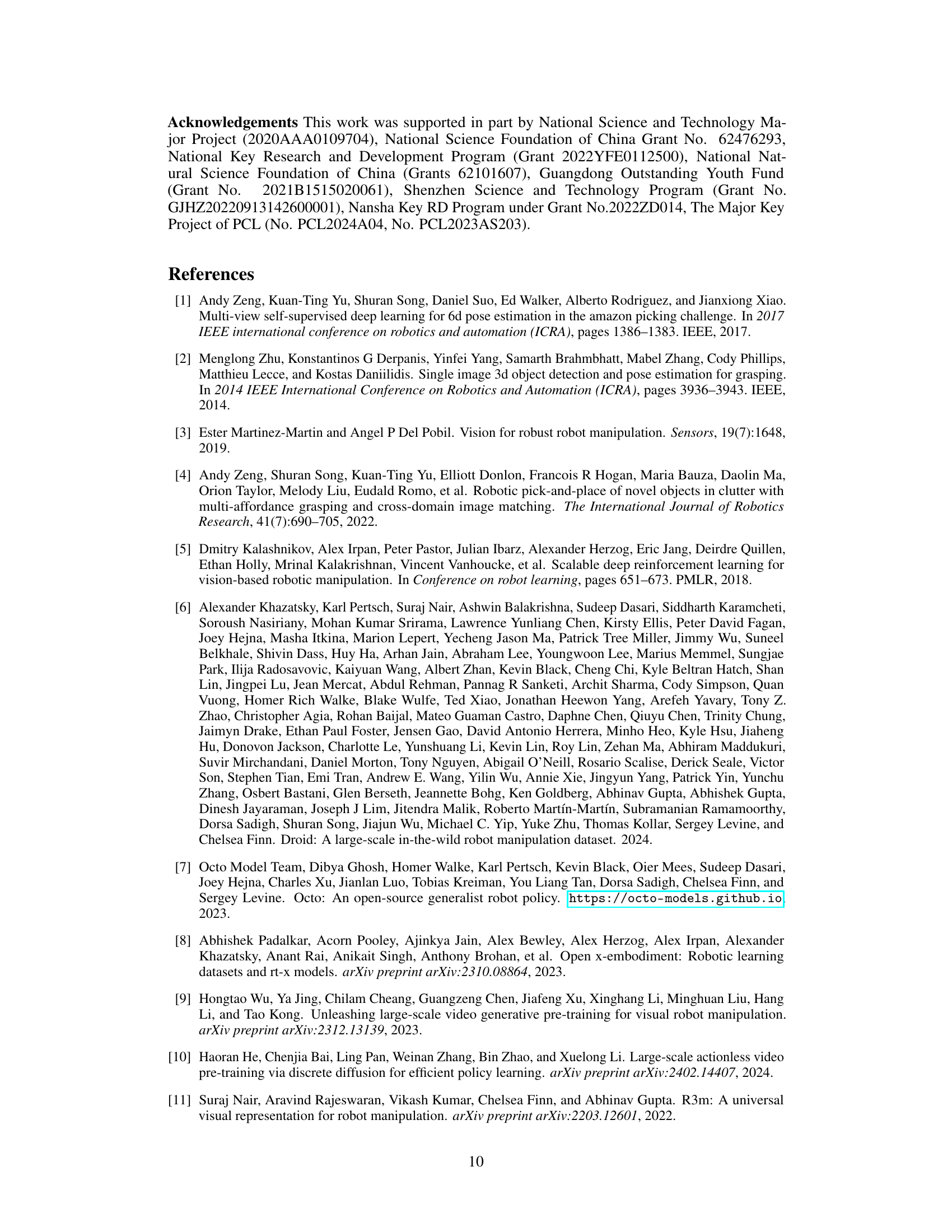

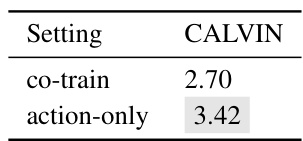

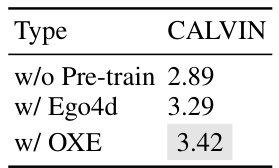

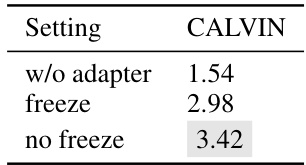

This table presents ablation study results on the VidMan model, focusing on three key aspects: the two-stage training strategy, the type of pretraining used, and the inclusion of a layer-wise adapter. For each setting, the average task completion length on the CALVIN benchmark is reported. The best-performing setting for each aspect is highlighted in gray, demonstrating the importance of each component for optimal performance.

This table presents ablation study results on the CALVIN benchmark, evaluating the impact of different design choices in the VidMan model. It compares the average task completion length achieved with different model variations focusing on the two-stage training process, pretraining datasets, and the use of the layer-wise adapter. The results highlight the importance of each component in achieving optimal performance. The gray shaded cell indicates the best performing configuration.

This table presents ablation study results on the CALVIN benchmark to analyze the impact of key components in the VidMan model. It shows the average task completion length (a metric of performance) under various settings. Specifically, it evaluates the effects of the two-stage training, the type of pretraining (using general or robot-specific data), the inclusion of the layer-wise adapter, and whether the Open-Sora model parameters are frozen during the second stage. The best performing setting is highlighted.

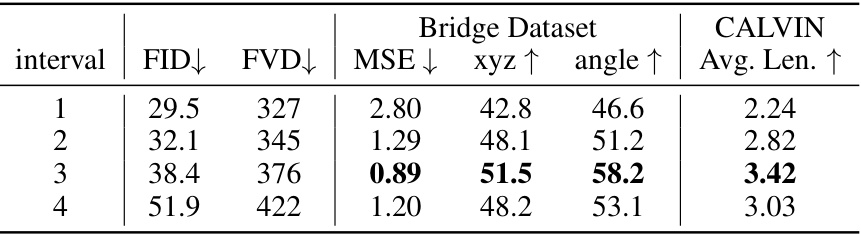

This table presents the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of different frame sampling intervals (1, 2, 3, and 4) on the performance of the VidMan model. The performance metrics evaluated include FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), FVD (Fréchet Video Distance), MSE (Mean Squared Error) for action prediction, xyz accuracy (accuracy of predicted 3D position), angle accuracy (accuracy of predicted orientation), and the average task length. The results demonstrate that increasing the frame sampling interval to 3 improves performance, while further increases yield diminishing returns. The data is separated for both the Bridge Dataset and the CALVIN benchmark.

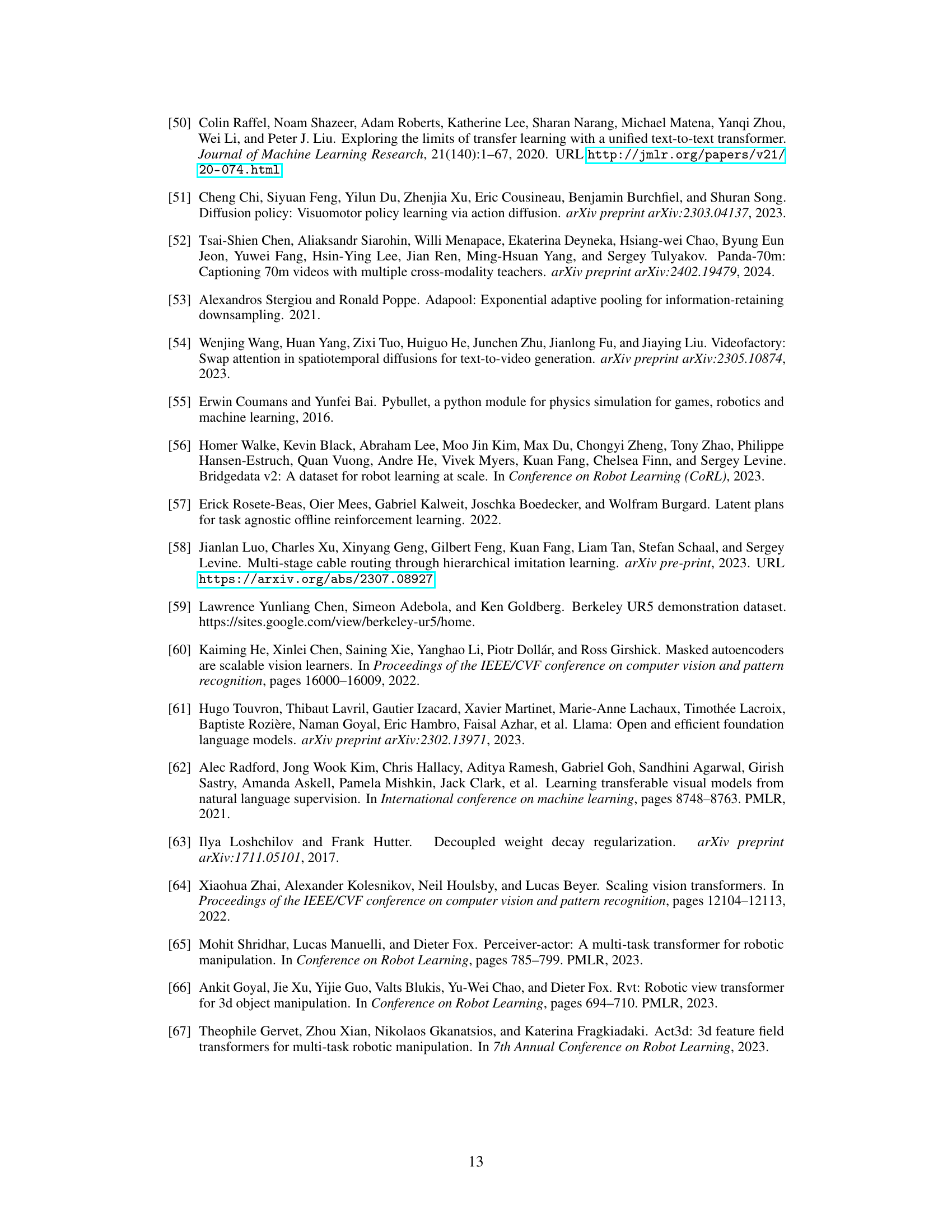

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the VidMan model. It breaks down the settings used for each of the three training stages: the initial dynamics-aware visionary stage, the second stage using the OXE dataset, and the second stage using the CALVIN dataset. The hyperparameters include batch size, learning rate, dropout rate, optimizer, weight decay, learning rate schedule, and number of training steps.

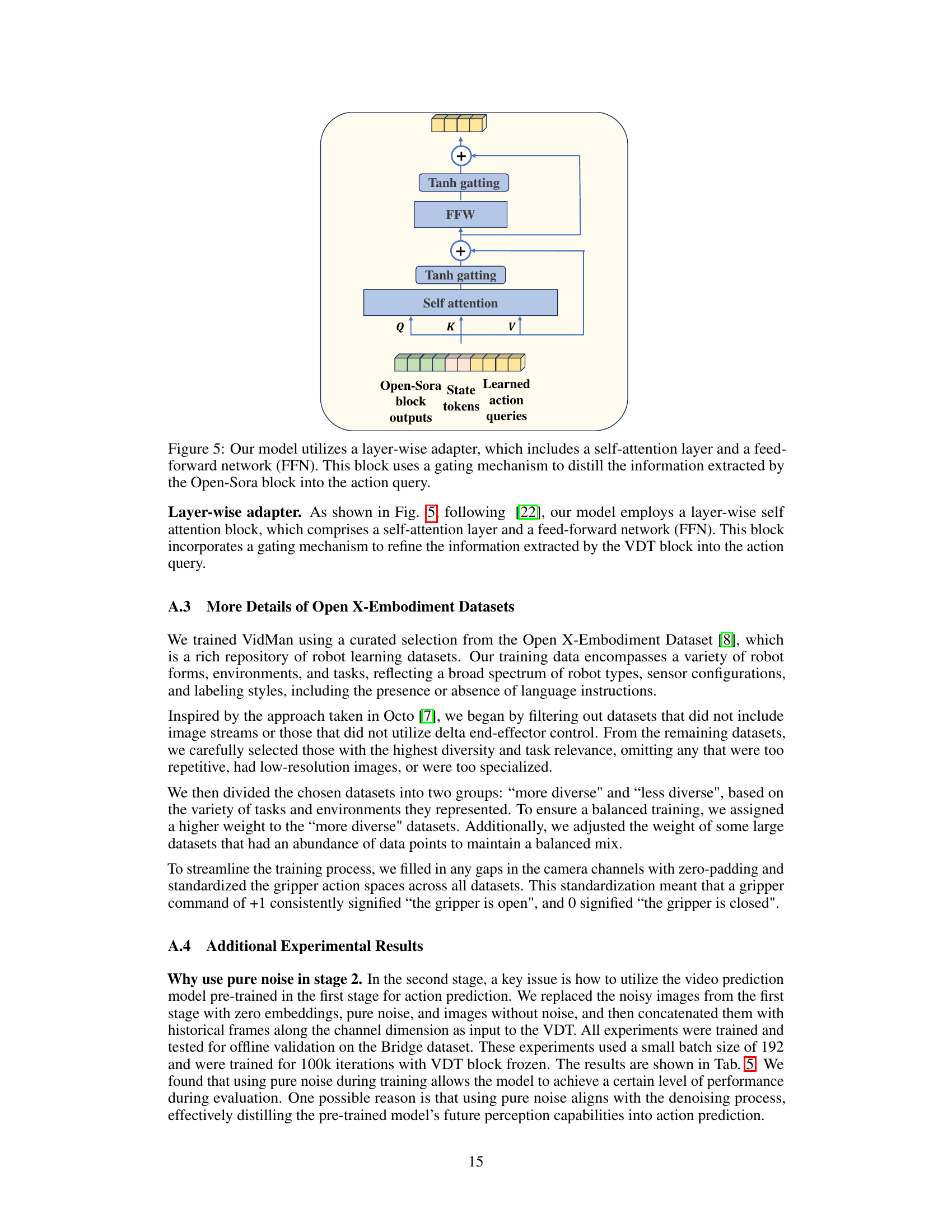

This table presents the ablation study results on the impact of different input types (Vk) in stage 2 of the VidMan model. Specifically, it compares the model’s performance when using (1) no noise added to historical frames, (2) only pure noise, and (3) pure zero embeddings concatenated with historical frames. The performance metrics used are Mean Squared Error (MSE), xyz accuracy, and angle accuracy. Lower MSE indicates better performance, while higher xyz and angle accuracy values are also desirable. The results show that concatenating historical frames with pure noise yields significantly better performance than other input variations.

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing different lengths of historical and future frames in the VidMan model. The experiment varied the number of historical frames (m) and future frames (n) used in the model’s training and evaluated the impact on several metrics, including Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Fréchet Video Distance (FVD), Mean Squared Error (MSE), xyz accuracy, angle accuracy, and average length. The results show that increasing the number of historical frames has a more significant positive impact on the model’s performance than increasing the number of future frames. This suggests that the model benefits more from a strong understanding of past events than from highly detailed predictions of distant future states.

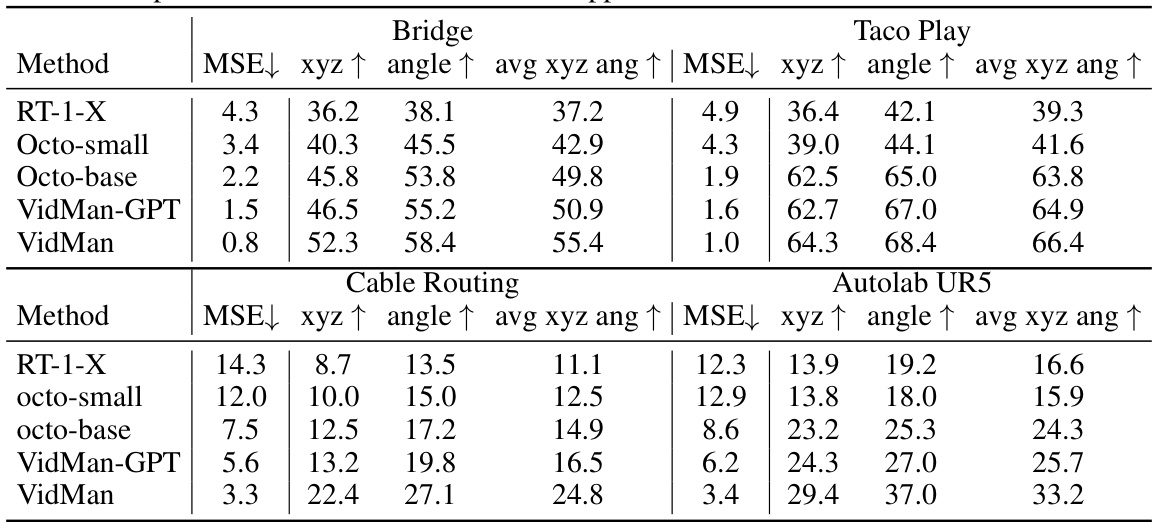

This table presents a detailed comparison of the offline performance of VidMan against several baseline models across four datasets from the Open X-Embodiment dataset (OXE). The metrics used for comparison include Mean Squared Error (MSE), XYZ accuracy, angle accuracy, and the average of XYZ and angle accuracy (avg xyz ang). The results highlight VidMan’s superior performance, particularly in datasets with limited data, showcasing its effective data utilization strategy.

This table presents a comparison of VidMan’s performance against various state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on the CALVIN benchmark for zero-shot long-horizon robot manipulation tasks. It shows the average number of tasks completed consecutively for each method, broken down by training data type (All or Lang) and the average length of the successfully completed sequences. VidMan significantly outperforms most prior methods, especially 2D hierarchical and transformer-based approaches, achieving results competitive with the more recent 3D methods.

Full paper#