↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Adapting pre-trained models on edge devices is challenging due to memory constraints of backpropagation and the limited training capabilities of most low-power processors. Existing methods for reducing memory footprint during training, such as parameter-efficient fine-tuning, do not fundamentally solve this problem because they still require storage of intermediate activations. The paper investigates a new approach using forward gradients which only requires a pair of forward passes for gradient estimation, saving memory substantially.

This paper introduces quantized forward gradient learning, applying quantized weight perturbations and gradient calculations to adapt models on devices with fixed-point processors. The researchers propose algorithm enhancements to mitigate noise in the gradient approximation and demonstrate the efficacy of their approach through extensive experiments. The results show that on-device training with quantized forward gradients is feasible and achieves comparable accuracy to backpropagation, paving the way for more practical and resource-efficient edge AI applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a practical solution for on-device model training, a critical area for edge AI. It addresses the memory limitations of backpropagation using quantized forward gradients, opening new avenues for personalized and privacy-preserving AI applications. The findings are relevant to researchers working on resource-constrained devices and those interested in developing efficient training algorithms for deep learning models.

Visual Insights#

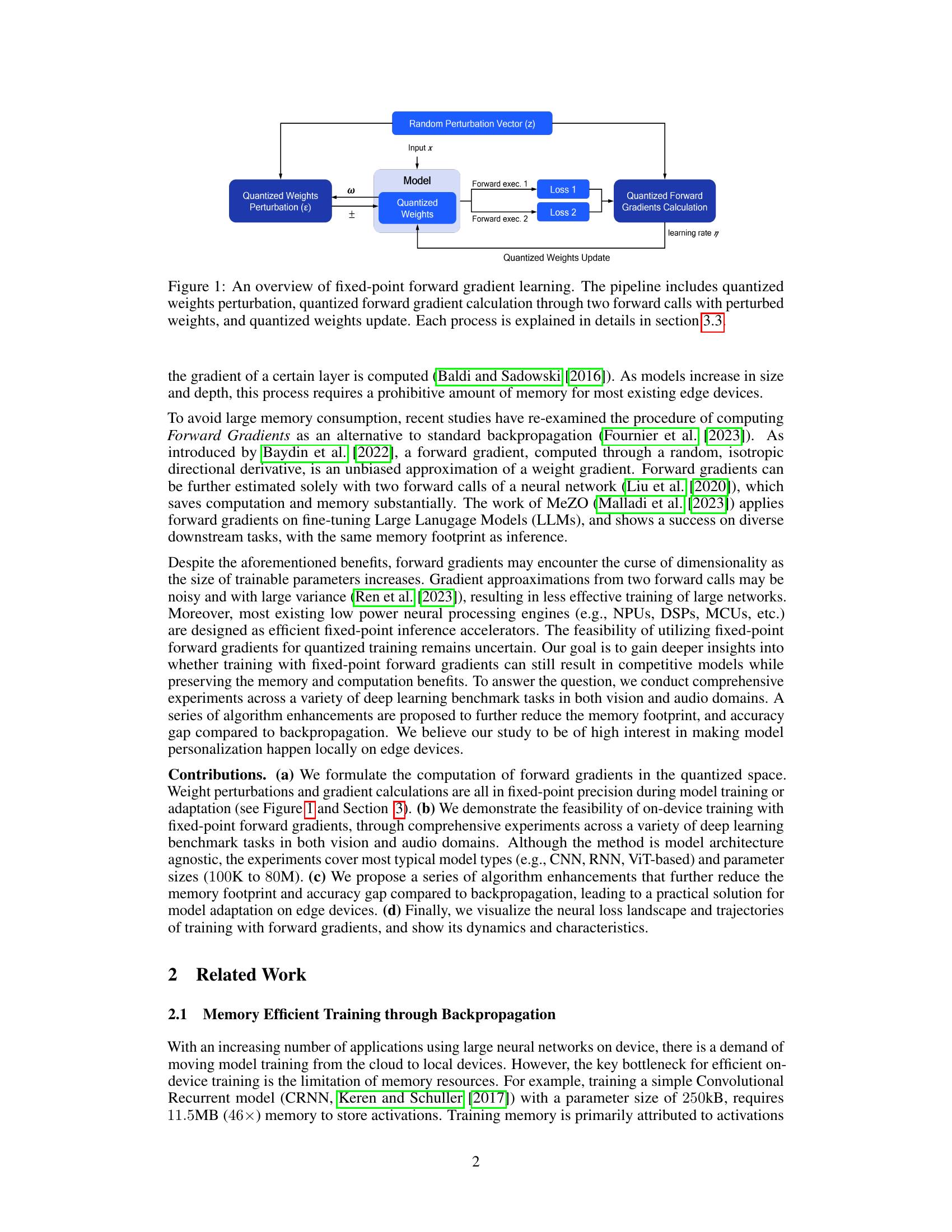

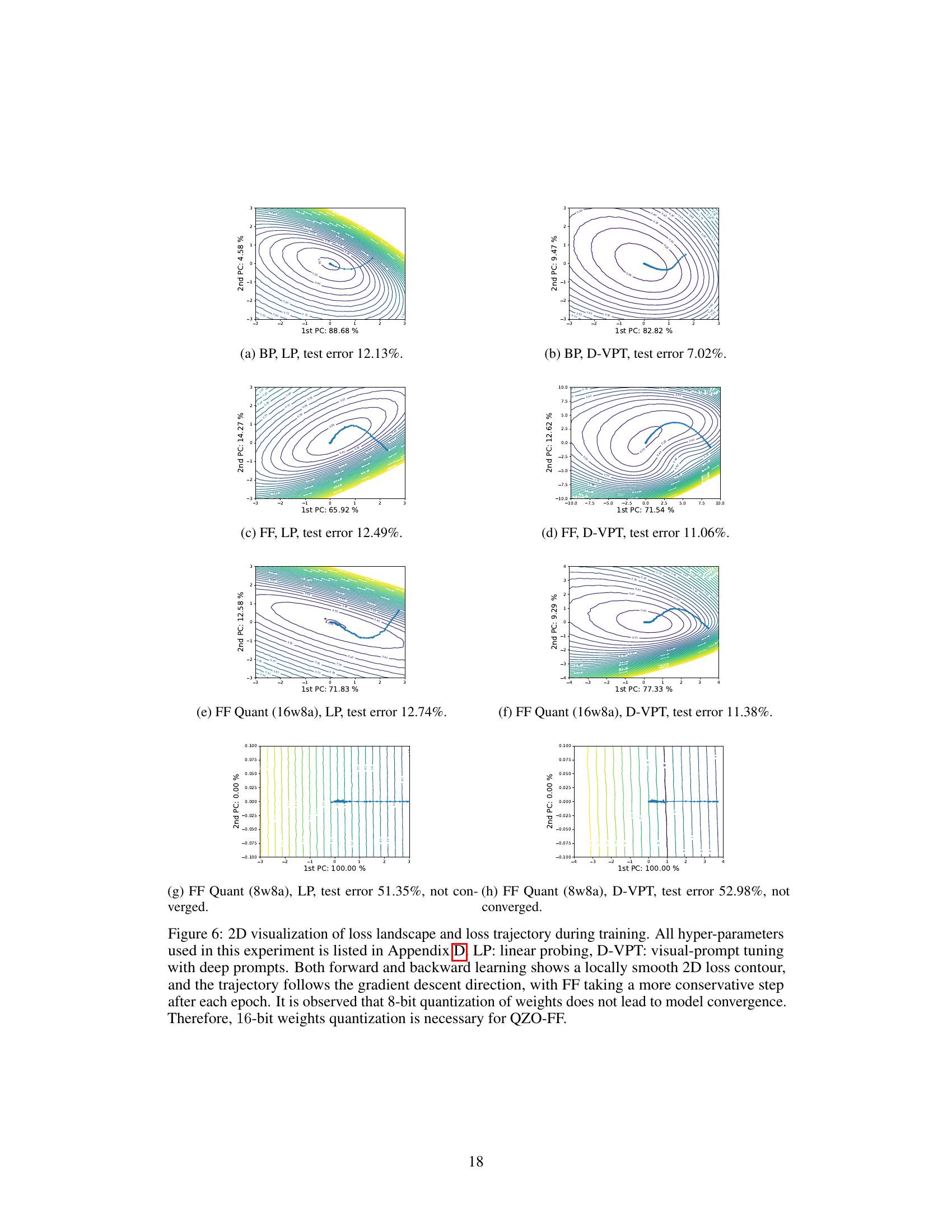

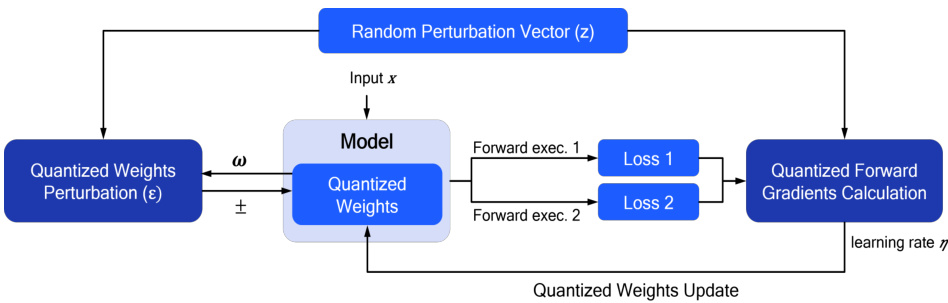

This figure illustrates the process of fixed-point forward gradient learning. It starts with quantized weights which are perturbed using a random perturbation vector. These perturbed weights are then used in two forward passes through the model, resulting in two loss values. These loss values are used to calculate the quantized forward gradients. Finally, these gradients are used to update the quantized weights, completing one iteration of the training process. The entire process is designed to be performed using fixed-point arithmetic, suitable for resource-constrained edge devices.

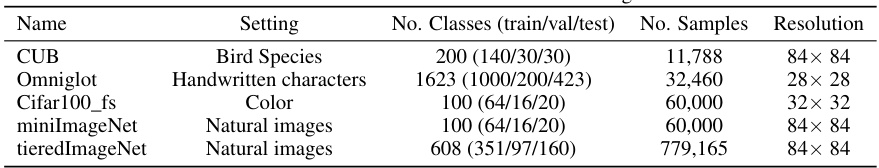

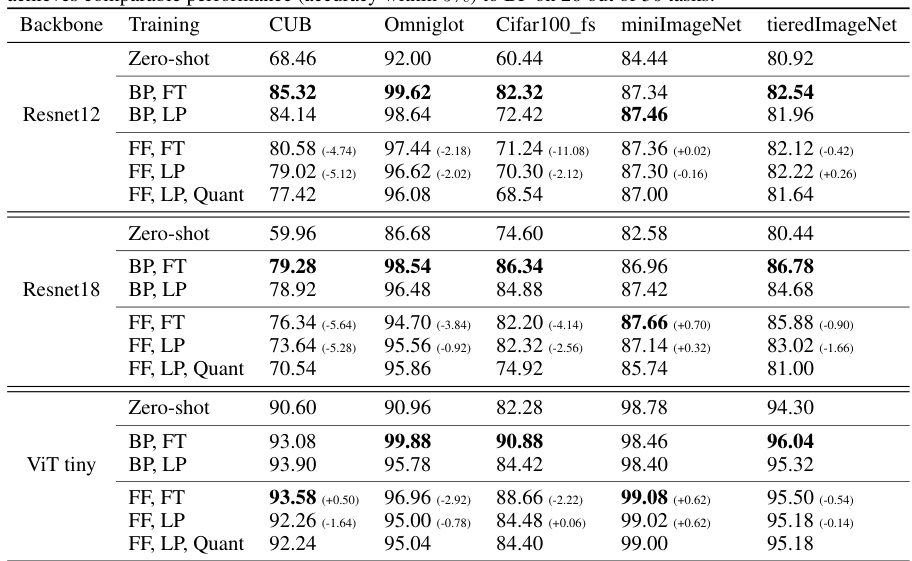

This table lists five vision datasets used in the few-shot learning experiments. For each dataset, it provides the setting (e.g., bird species, handwritten characters), the number of classes (broken down into training, validation, and testing sets), the total number of samples, and the image resolution.

In-depth insights#

On-device training#

On-device training presents a compelling solution to overcome the limitations of cloud-based machine learning, particularly concerning privacy, latency, and bandwidth. The core challenge lies in the resource constraints of edge devices, including limited memory, processing power, and energy. This paper explores the viability of on-device training by employing forward gradient learning, a memory-efficient alternative to backpropagation, which requires storing intermediate activations for gradient calculation. By leveraging forward gradients computed from two forward passes, memory consumption is drastically reduced, making it feasible for resource-constrained environments. The paper further investigates fixed-point arithmetic for on-device training, addressing the practical limitations of existing low-power neural processing units. This approach simplifies the hardware requirements and improves efficiency. Quantization strategies are employed to further minimize the memory footprint and reduce the computational complexity. The results show promising performance of this method across various benchmarks, demonstrating its practical feasibility and potential for widespread adoption. However, further research into improving the robustness and scalability of on-device training using forward gradients, particularly for larger models, remains crucial.

Forward gradients#

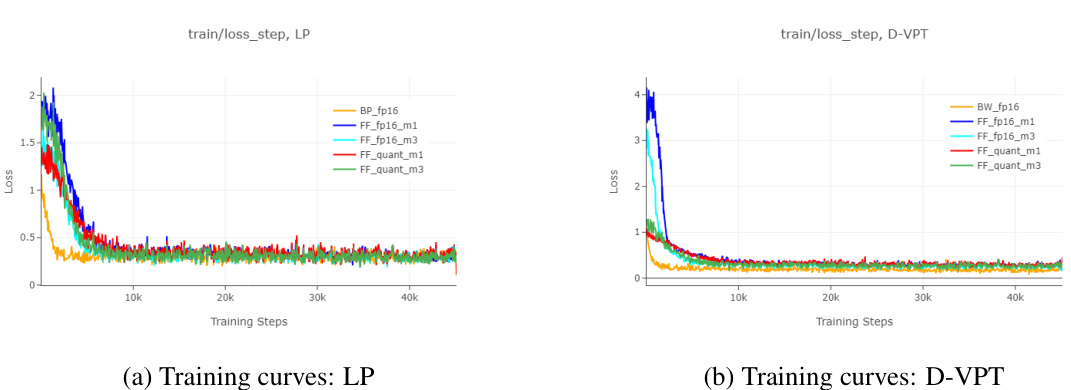

The concept of “forward gradients” presents a compelling alternative to traditional backpropagation in model training, especially beneficial for resource-constrained edge devices. Its core advantage lies in significantly reducing memory consumption by eliminating the need to store intermediate activation values during the backward pass. This is achieved by estimating gradients using only forward computations, typically involving multiple forward passes with perturbed inputs or weights. While this approach introduces noise into gradient estimation, the paper explores methods such as sign-m-SPSA to mitigate this, demonstrating that competitive accuracy can be achieved even with fixed-point quantization, a crucial aspect for low-power hardware. The analysis of training trajectories and loss landscapes provides further insights into the effectiveness and practical feasibility of this technique. However, challenges remain concerning the trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency, particularly as model complexity increases, along with considerations surrounding the sensitivity of the approach to hyperparameter tuning and initialization schemes.

Quantized methods#

The concept of quantization in the context of deep learning is crucial for deploying models on resource-constrained devices. Quantized methods reduce the precision of numerical representations (e.g., weights and activations) from 32-bit floating-point to lower bit-widths (e.g., 8-bit integers). This significantly reduces memory footprint and computational cost, making deep learning feasible for edge devices. However, quantization introduces a trade-off: while it enhances efficiency, it can also negatively impact model accuracy. The paper investigates strategies to mitigate the accuracy loss associated with quantization, particularly focusing on fixed-point arithmetic for both forward gradient calculations and weight updates. By carefully managing the quantization process, the authors aim to minimize the discrepancy between quantized and floating-point models, demonstrating the practicality of deploying deep learning for on-device training in low-resource environments. The success of these methods hinges on the selection of appropriate quantization schemes and the development of algorithms that effectively handle quantized data, without substantial loss in performance.

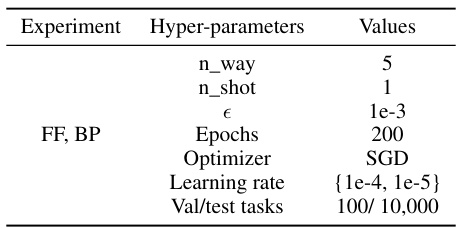

Few-shot learning#

The research explores few-shot learning within the context of on-device model adaptation. This is a crucial area because it addresses the challenge of training large models on resource-constrained edge devices where data is limited. The core idea is to leverage pre-trained models and adapt them to new tasks using only a small number of labeled samples. The study investigates the feasibility and effectiveness of using fixed-point forward gradients, a memory-efficient alternative to backpropagation, for this few-shot learning scenario. Key findings highlight the method’s capability to achieve competitive accuracy compared to backpropagation, particularly when utilizing stronger model architectures like ViT. The results suggest that this approach is practical for model personalization on resource-limited edge devices, opening doors for more widespread on-device machine learning applications where collecting large amounts of training data is impractical or expensive. However, there’s also a clear trade-off between training efficiency and accuracy, particularly with smaller models and lower-resolution inputs. Future research could focus on refining techniques to improve accuracy in more challenging scenarios and expanding exploration to a broader range of tasks and model architectures. Overall, this work presents a significant contribution towards enabling efficient on-device few-shot learning.

OOD adaptation#

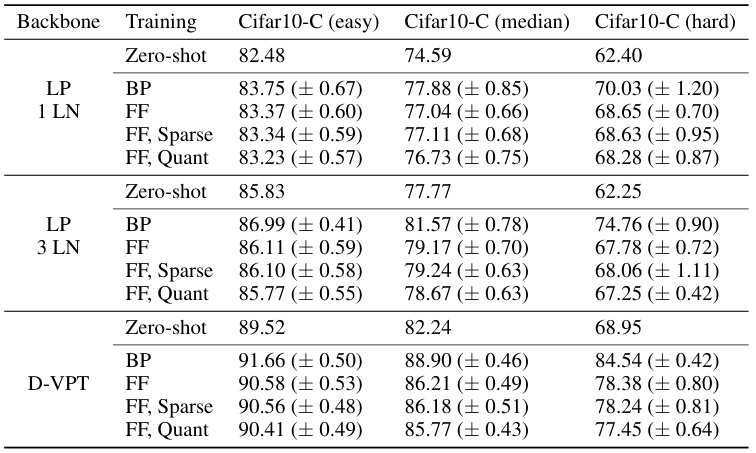

The section on “OOD adaptation” in the research paper investigates the model’s ability to generalize to out-of-distribution (OOD) data. This is crucial for real-world applications where the model encounters data different from its training distribution. The experiments using the Cifar10-C dataset, with its various corruptions, are particularly insightful. The results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed quantized forward gradient learning method, even when dealing with significant data perturbations. Interestingly, the study also explores the impact of applying sparsity techniques, suggesting that a substantial reduction in model size can be achieved without significant performance degradation. The findings underscore the practical value of the method for resource-constrained edge devices, where both memory efficiency and robustness to unexpected input variations are critical concerns. Further research into the interactions between sparsity, quantization, and OOD robustness will likely reveal more refined strategies for developing highly efficient and robust models deployable in real-world environments. The performance comparison with backpropagation across different network depths and fine-tuning methods provides a robust evaluation of the technique’s versatility and general applicability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the process of fixed-point forward gradient learning, which involves three main steps: 1. Perturbing the quantized weights using a random perturbation vector; 2. Calculating the quantized forward gradient using two forward passes with the perturbed weights; and 3. Updating the quantized weights using the calculated gradient. The figure highlights the use of quantization throughout the process, emphasizing its suitability for resource-constrained edge devices.

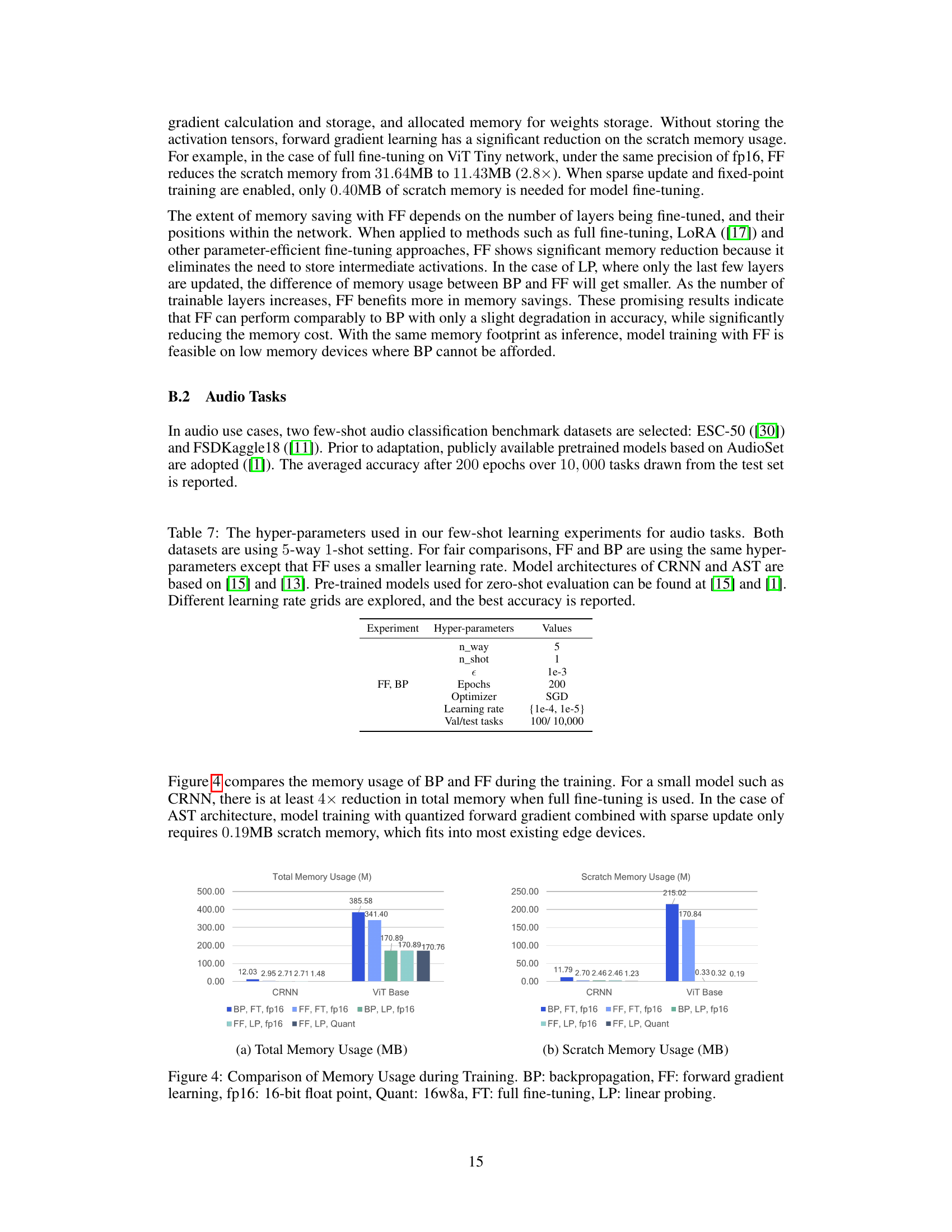

This figure shows the results of ablation studies on cross-domain adaptation using ViT Tiny on the Visual Wake Word (VWW) dataset. The left panel is a bar chart comparing the mean accuracy and standard deviation across different training methods: zero-shot, backpropagation (BP) with fp16 precision, forward gradient (FF) with fp16 precision (with different m values for gradient averaging), and quantized FF (16w8a and 8w8a with different m values) with both linear probing (LP) and visual-prompt tuning (D-VPT). The right panel illustrates the sharpness-aware update method, a variation used in FF. The diagram shows how the weights are perturbed at a neighborhood position to avoid sharp minima in the loss landscape.

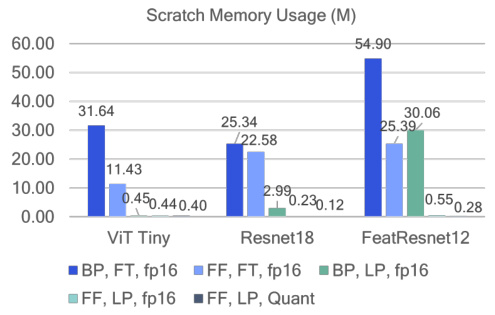

This figure compares the total and scratch memory usage during training for different model architectures (ViT Tiny, ResNet18, FeatResNet12) and training methods (backpropagation (BP), forward gradient (FF), full fine-tuning (FT), linear probing (LP), and quantized (Quant)). It visually demonstrates the memory savings achieved by using forward gradient learning, especially when combined with quantization and linear probing.

This figure compares the memory usage of backpropagation (BP) and forward gradient learning (FF) during the training process for different model architectures (ViT Tiny, ResNet18, FeatResNet12). It shows the total memory usage and the scratch memory usage separately. The scratch memory is the memory needed for intermediate activations and gradients during the training process. The figure shows that FF significantly reduces the scratch memory usage compared to BP, especially when using the quantized version of FF (16w8a). This reduction is more pronounced in full fine-tuning (FT) compared to linear probing (LP).

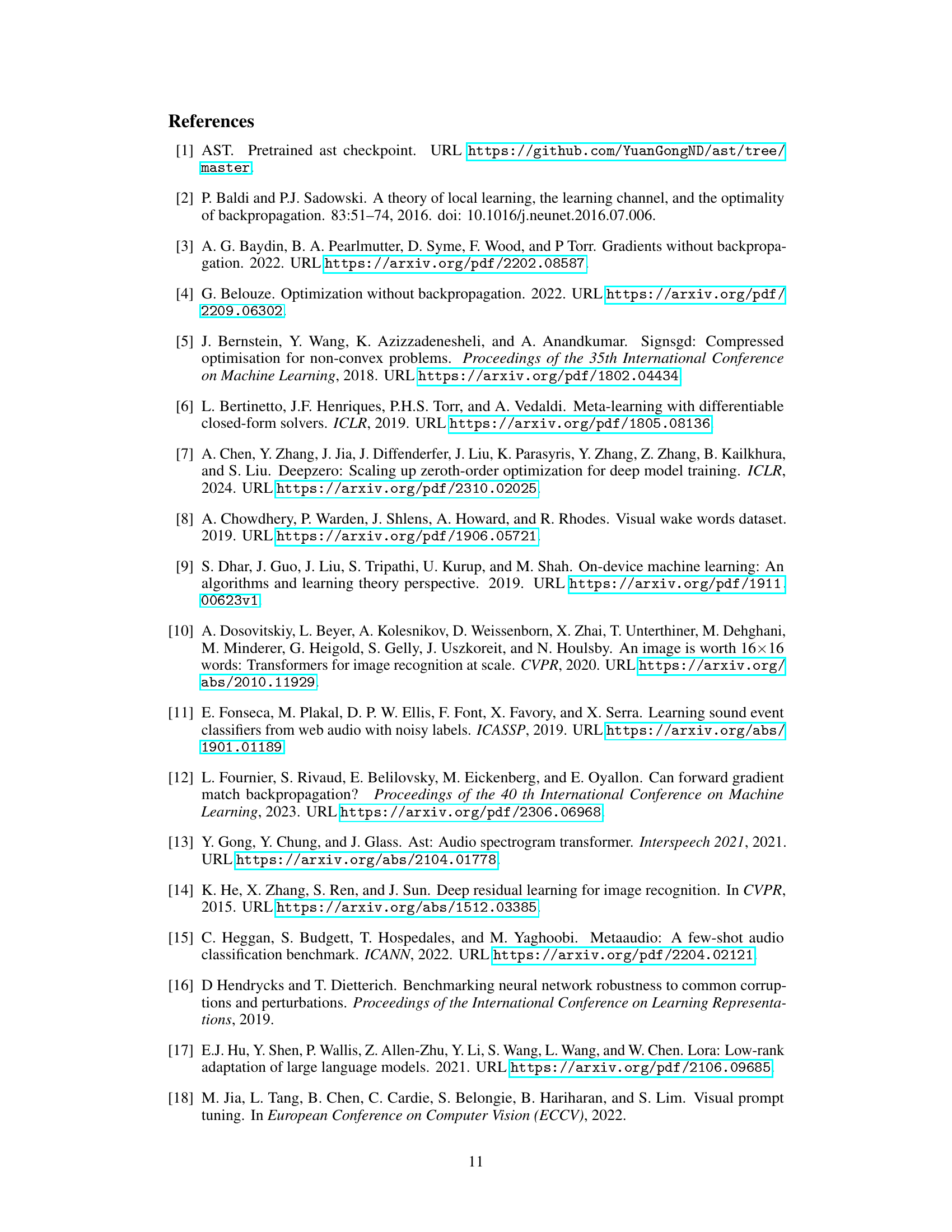

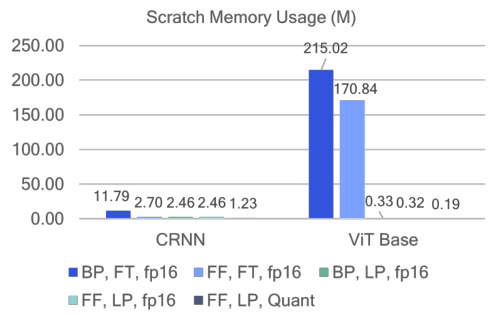

This figure compares the total and scratch memory usage during training for different model architectures (CRNN and ViT Base) and training methods (backpropagation (BP) and forward gradient learning (FF)). It shows that forward gradient learning significantly reduces memory usage compared to backpropagation, especially for the ViT Base model, achieving a reduction of up to 2.8x in scratch memory when using fp16 precision.

The figure shows the memory usage comparison between backpropagation (BP) and forward gradient learning (FF) during training. It breaks down the memory usage into total memory and scratch memory for different model architectures (CRNN and ViT Base) and training methods (full fine-tuning (FT) and linear probing (LP)). The results highlight the significant memory reduction achieved by FF, particularly when using quantization (Quant).

This figure presents ablation studies on cross-domain adaptation using ViT tiny backbone on the Visual Wake Word (VWW) dataset. It shows a comparison of the classification accuracy with standard deviation obtained through different methods: Linear probing (LP), Visual prompt tuning with deep prompts (D-VPT), using floating point (fp16) and quantized (16w8a) precision with different numbers of forward gradient averaging (m=1, m=3). The results demonstrate the impact of various methods and hyperparameters on the adaptation performance.

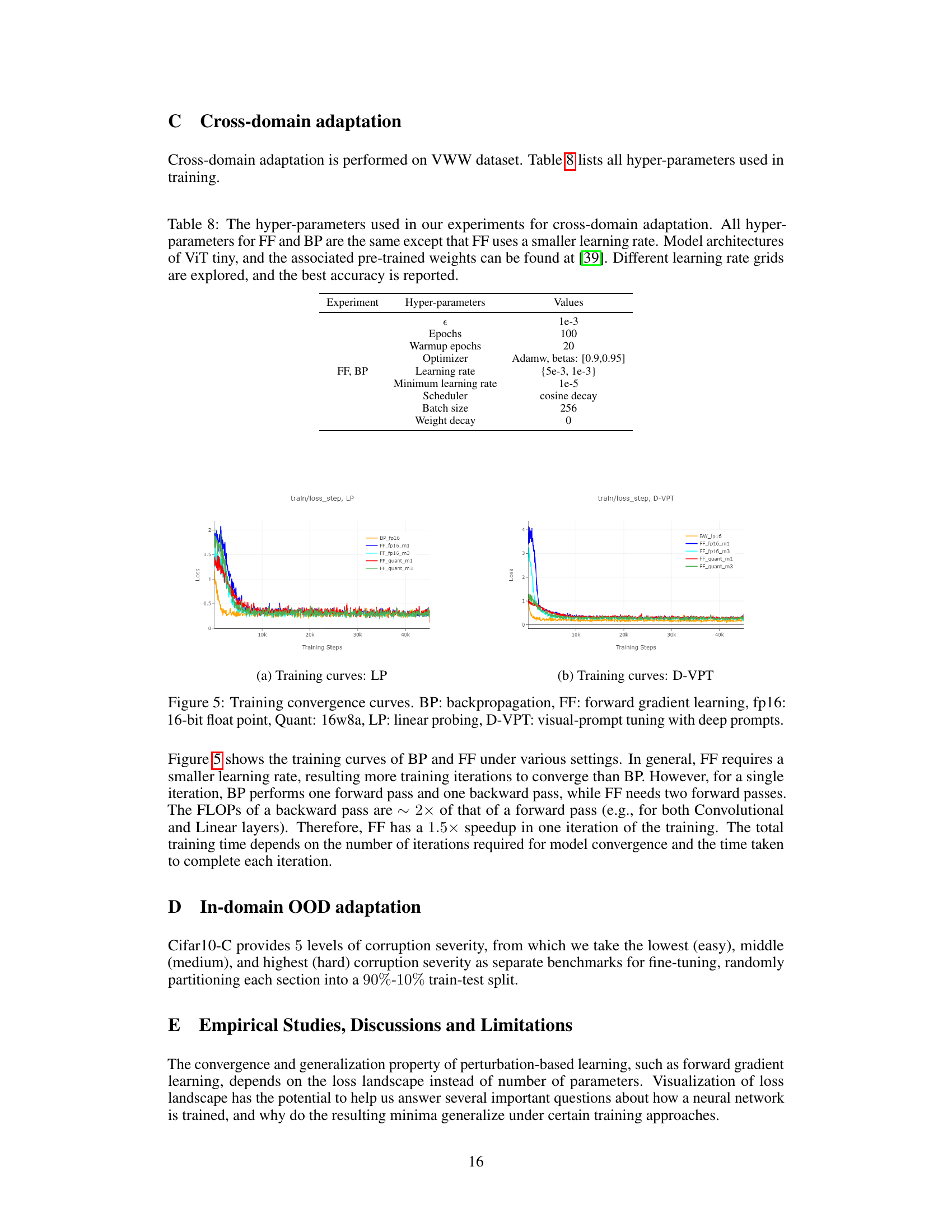

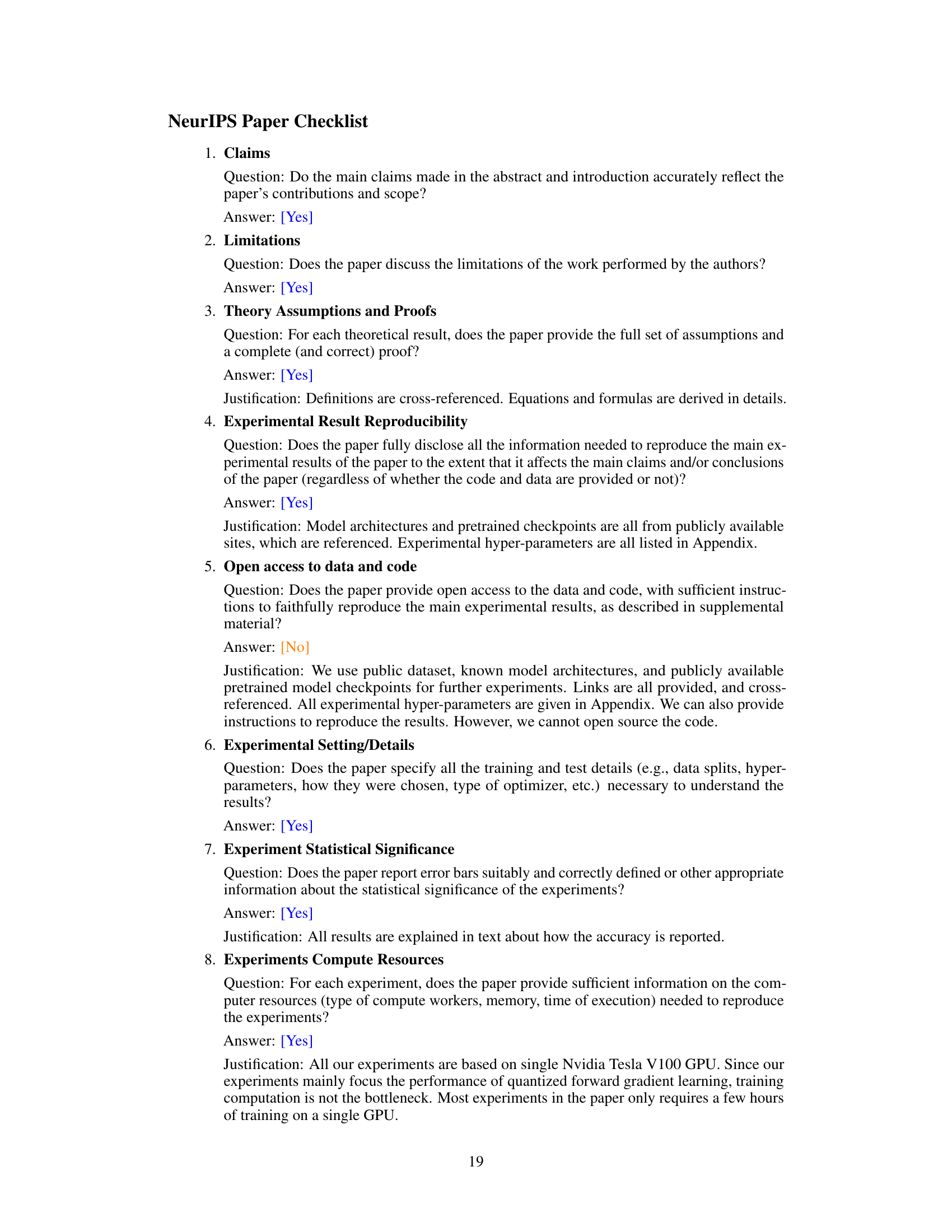

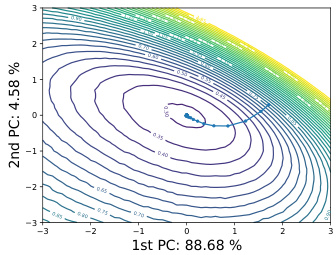

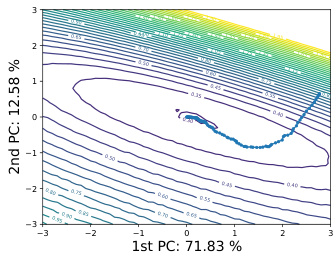

This figure shows a 2D visualization of the loss landscape and the training trajectory for both backpropagation (BP) and quantized zero-order forward-forward gradient (QZO-FF) methods. The loss landscape is relatively smooth for both methods. The QZO-FF trajectory shows a more gradual descent compared to BP, indicating slower convergence but potentially better generalization.

This figure visualizes the loss landscape and training trajectory for both backpropagation (BP) and quantized zero-order forward gradient (QZO-FF) methods. The 2D contour plots show the loss landscape, and the line plots illustrate the training trajectory within that landscape. The results show that while both methods exhibit smooth loss contours, QZO-FF exhibits slower convergence.

This figure visualizes the 2D loss landscape and training trajectory for both backpropagation (BP) and the proposed quantized zero-order forward gradient (QZO-FF) method. The plots show that both methods navigate a relatively smooth loss landscape. QZO-FF exhibits a more cautious step size compared to BP. The results highlight that 8-bit quantization of weights is insufficient for QZO-FF to converge, requiring 16-bit quantization for effective training.

This figure visualizes the loss landscape and training trajectory for both backpropagation (BP) and quantized zero-order forward gradient (QZO-FF) methods. The 2D plots show the loss landscape, with contour lines representing different loss values. The trajectories show the path taken by the model’s parameters during training. The results indicate that QZO-FF follows a smoother, more conservative path compared to BP, but still converges to a low-loss region. It also highlights that using 8-bit quantization for the weights prevents the QZO-FF method from converging, whereas 16-bit quantization allows for successful convergence.

This figure visualizes the loss landscape and training trajectory for both backpropagation (BP) and the proposed quantized zero-order forward gradient (QZO-FF) method. The 2D plots show the loss surface as contour lines, with the training trajectory overlaid as a sequence of points. The plots demonstrate that both methods navigate a relatively smooth loss landscape. However, QZO-FF shows a more cautious trajectory compared to BP. A key finding is that 8-bit weight quantization is insufficient for QZO-FF, highlighting the necessity of 16-bit quantization for successful training.

This figure visualizes the loss landscape and training trajectories using both backpropagation (BP) and quantized zero-order forward gradient learning (QZO-FF). It highlights the smoother loss contour and more conservative step size of QZO-FF compared to BP, indicating that a good model initialization is key for QZO-FF’s successful convergence. The figure also implicitly suggests that despite slower convergence, QZO-FF remains promising for low-resource device adaptation due to its reduced memory footprint.

This figure visualizes the loss landscape and training trajectories of both backpropagation (BP) and quantized zero-order forward gradient learning (QZO-FF) methods. It shows that both methods exhibit locally smooth loss surfaces. However, QZO-FF demonstrates a more conservative trajectory with slower convergence compared to BP. The figure also highlights the importance of good model initialization for QZO-FF’s success, as training from scratch may not guarantee convergence. The use of 8-bit quantization for weights is shown to be insufficient for QZO-FF to converge, requiring at least 16-bit precision.

This figure visualizes the loss landscape and training trajectory for both backpropagation (BP) and quantized zero-order forward gradient learning (QZO-FF). The 2D contour plots show the loss surface, with the trajectory indicating the path taken during training. The results suggest that QZO-FF converges more slowly than BP, but still reaches a relatively good minimum.

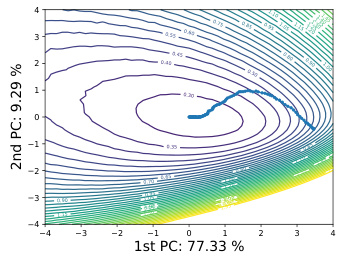

More on tables

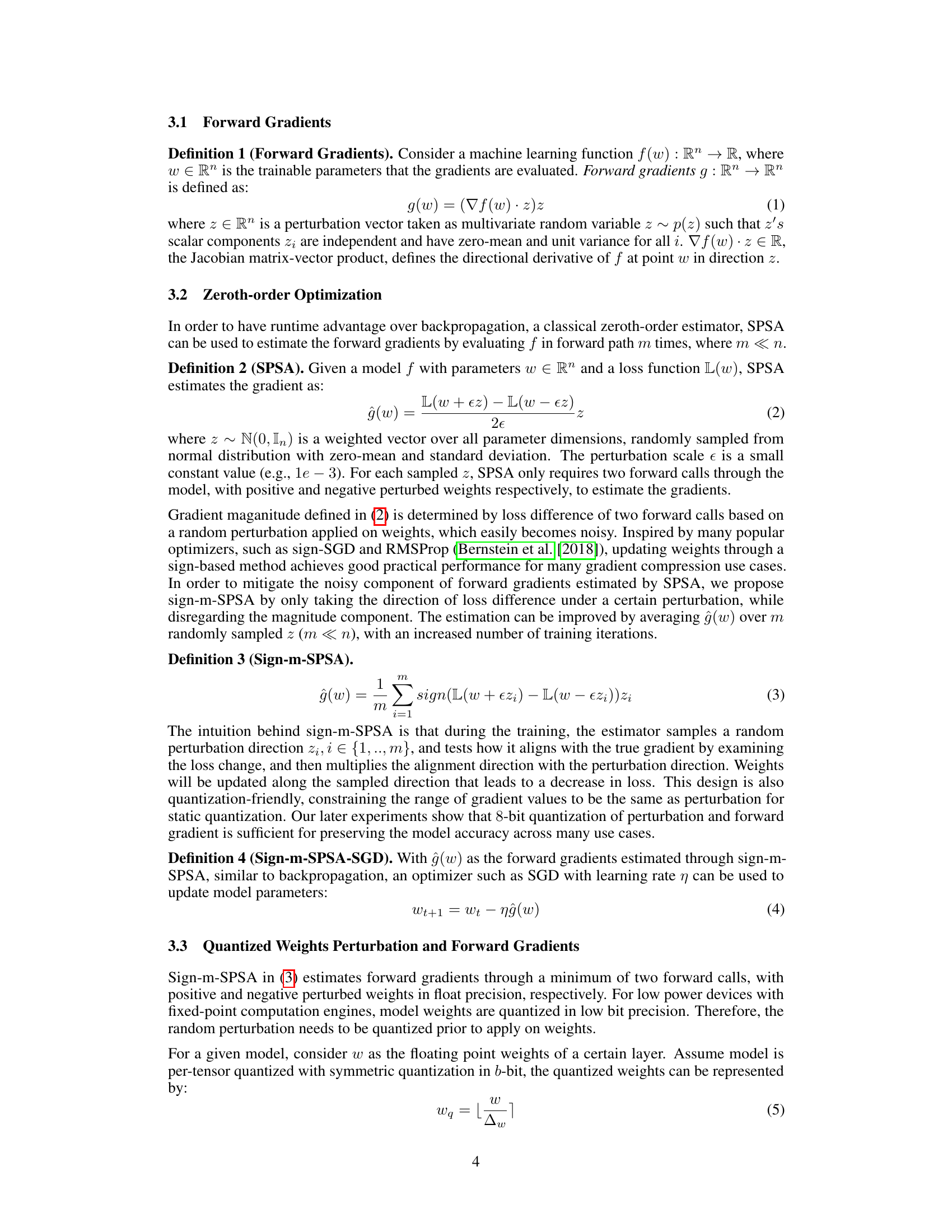

This table presents the results of few-shot learning experiments using both forward and backward gradient methods. It compares the accuracy of various model architectures (ResNet12, ResNet18, ViT tiny) on five different image classification datasets (CUB, Omniglot, Cifar100_fs, miniImageNet, tieredImageNet) with different training methods (full fine-tuning, linear probing). The table shows the performance of both floating-point and quantized training, highlighting the performance of the forward gradient approach relative to backpropagation.

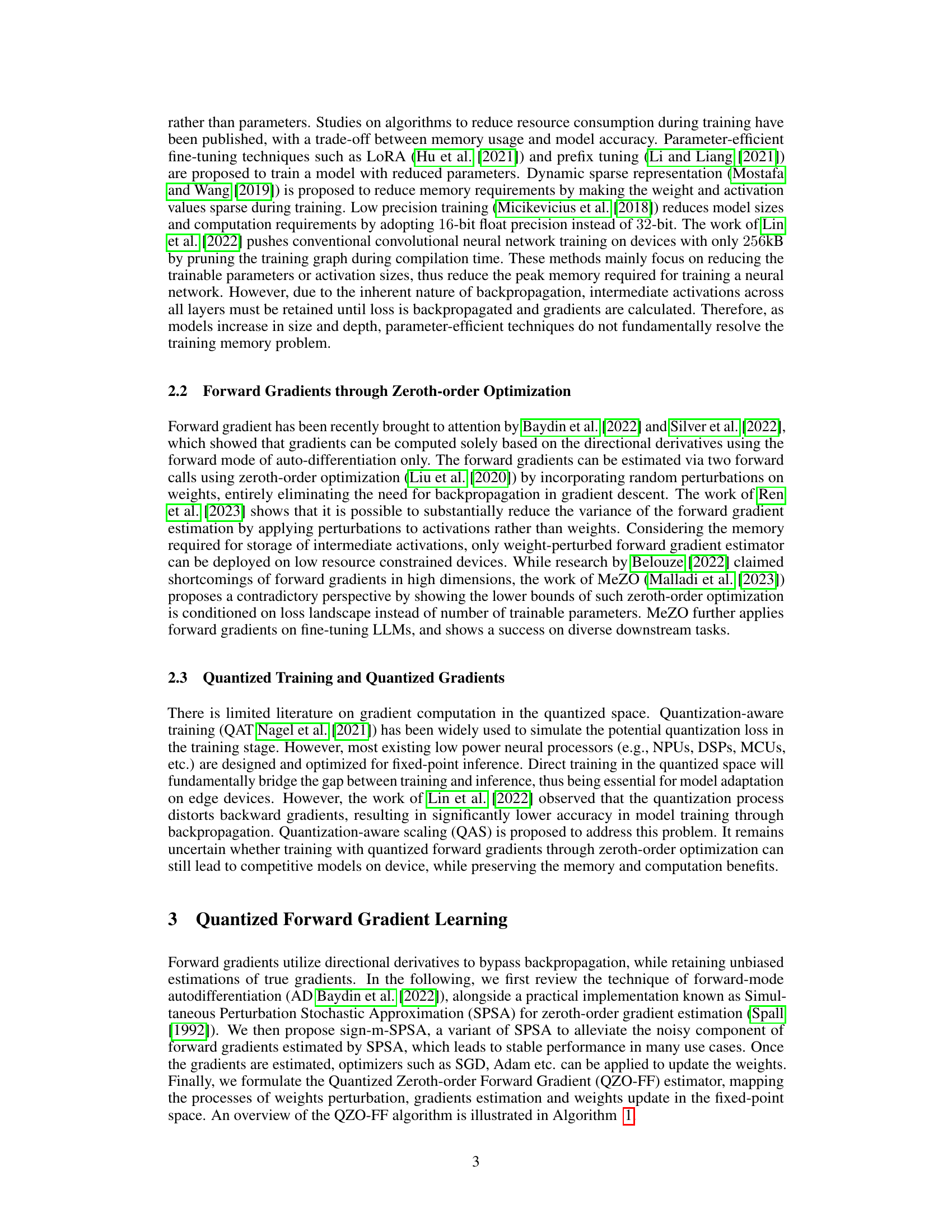

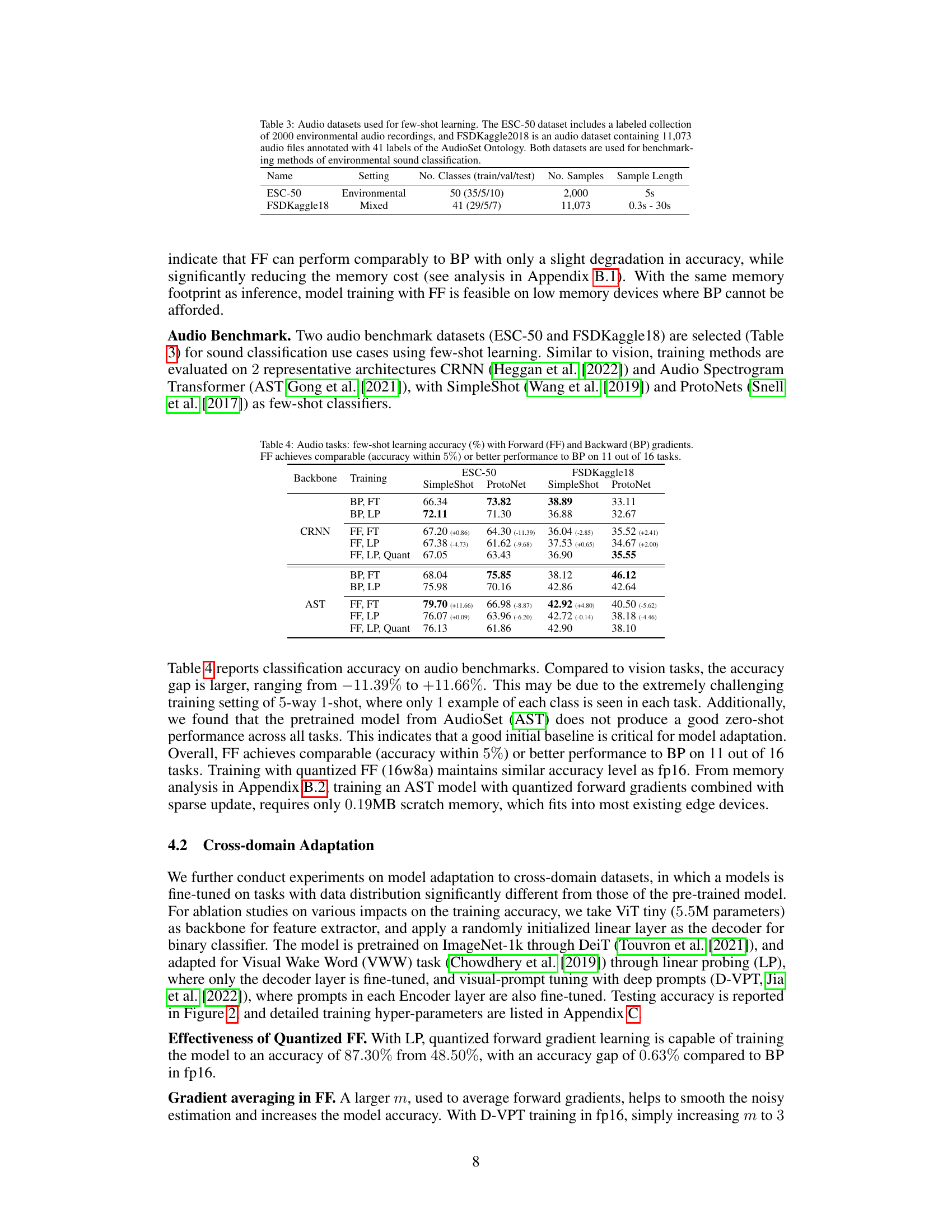

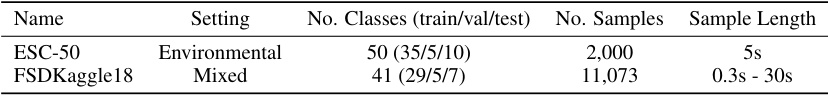

This table lists two audio datasets used in the few-shot learning experiments of the paper. It provides the name of each dataset, the type of audio it contains, the number of classes, the number of samples, and the length of each sample. The datasets are used to evaluate the performance of different few-shot learning methods on environmental sound classification.

This table presents the results of few-shot learning experiments on various vision datasets using different model architectures (ResNet12, ResNet18, ViT tiny). It compares the accuracy of training with forward gradients (FF) against backpropagation (BP), showing both full fine-tuning (FT) and linear probing (LP) results. Quantized versions of forward gradients are also included (Quant). The table highlights FF’s performance relative to BP and zero-shot baselines, demonstrating its effectiveness in few-shot learning scenarios.

This table presents the results of few-shot learning experiments on various vision datasets using different model backbones (ResNet12, ResNet18, ViT tiny) and training methods (full fine-tuning, linear probing). It compares the accuracy of using forward gradients (FF) against backpropagation (BP), with and without quantization (16-bit weights, 8-bit activations). The table highlights the performance of FF relative to BP and zero-shot learning (no adaptation).

This table presents the results of few-shot learning experiments using both forward and backward gradient methods. It compares the accuracy of different training approaches (full fine-tuning and linear probing) across five vision datasets and three network backbones (ResNet12, ResNet18, and ViT-tiny). The table also includes results for quantized forward gradient training (16-bit weights, 8-bit activations). The key finding is that forward gradients achieve comparable accuracy to backpropagation in many cases, especially when utilizing larger models.

This table presents the results of few-shot learning experiments on vision tasks using both forward and backward gradient methods. It compares the accuracy of full fine-tuning and linear probing with different precision levels (FP16 and quantized 16w8a). The results show that forward gradients perform comparably to backward gradients on many tasks and significantly improve over zero-shot performance.

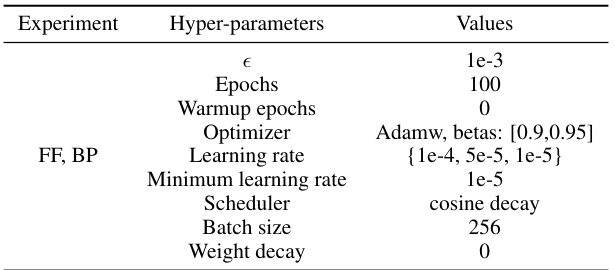

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the cross-domain adaptation experiments described in the paper. It shows that the hyperparameters for both forward gradient learning (FF) and backpropagation (BP) are largely the same, with the key difference being a smaller learning rate used in FF. The table also notes the source of pre-trained weights and the methodology for selecting optimal learning rates.

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the cross-domain adaptation experiments. It shows that the hyperparameters for both forward gradient (FF) and backpropagation (BP) methods were largely the same, except for the learning rate, which was smaller for FF. The ViT tiny model architecture and pretrained weights are referenced.

Full paper#