↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Probabilistic sequence modeling is critical in various machine learning applications, but existing models like next-token prediction and full-sequence diffusion have limitations. Next-token prediction models struggle with long-horizon generation and lack guidance mechanisms, while full-sequence diffusion models are limited by non-causal architectures, restricting variable-length generation and subsequence generation. This research introduces Diffusion Forcing (DF), a new training paradigm addressing these limitations.

DF trains a causal next-token prediction model to denoise tokens with independent per-token noise levels. This approach combines the strengths of both model types, enabling variable-length generation, long-horizon guidance, and novel sampling schemes such as Monte Carlo Guidance. Empirical results demonstrate that DF significantly improves upon existing methods in decision-making, planning, video generation and time series prediction tasks, showcasing its superior performance and flexibility.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in sequence modeling and related fields because it introduces a novel training paradigm that bridges the gap between next-token prediction and full-sequence diffusion models. This offers significant advantages for tasks requiring long-horizon predictions, such as video generation and planning, where existing methods often struggle with instability or limited controllability. The theoretical underpinnings and diverse experimental results further enhance its impact.

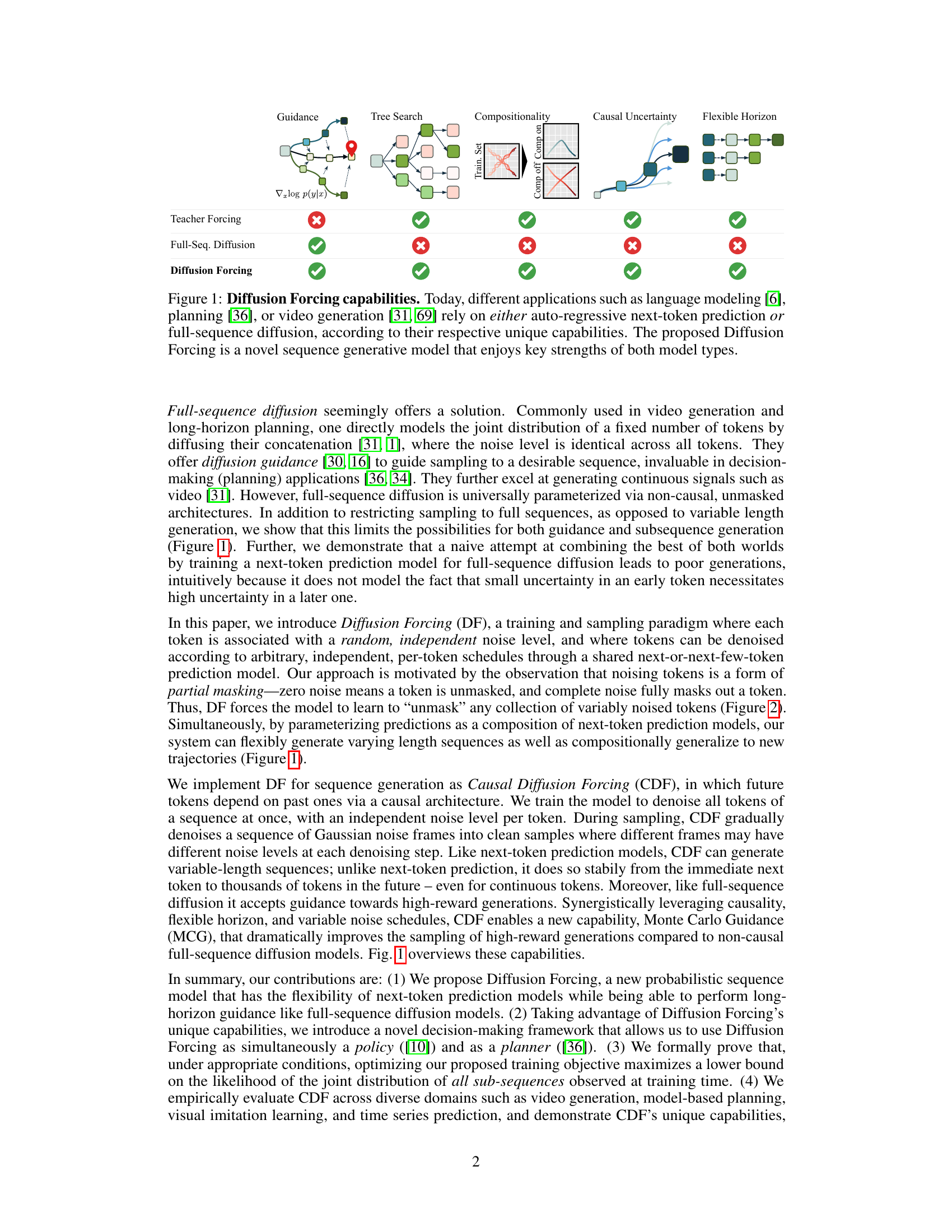

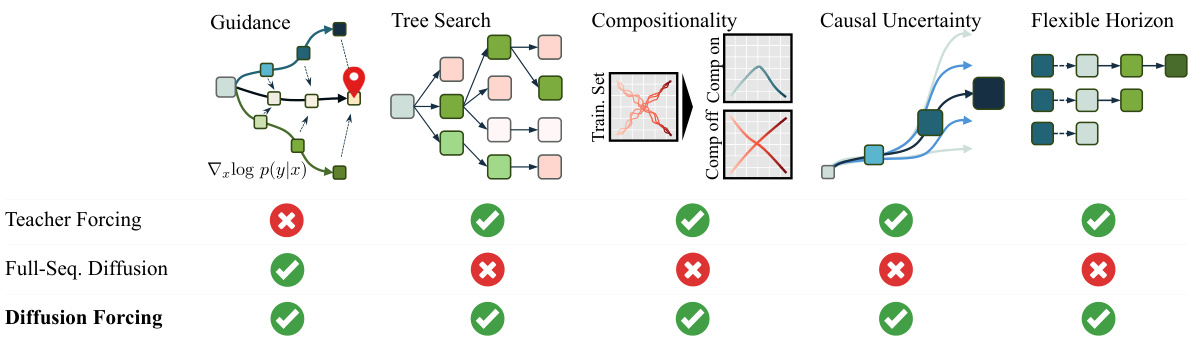

Visual Insights#

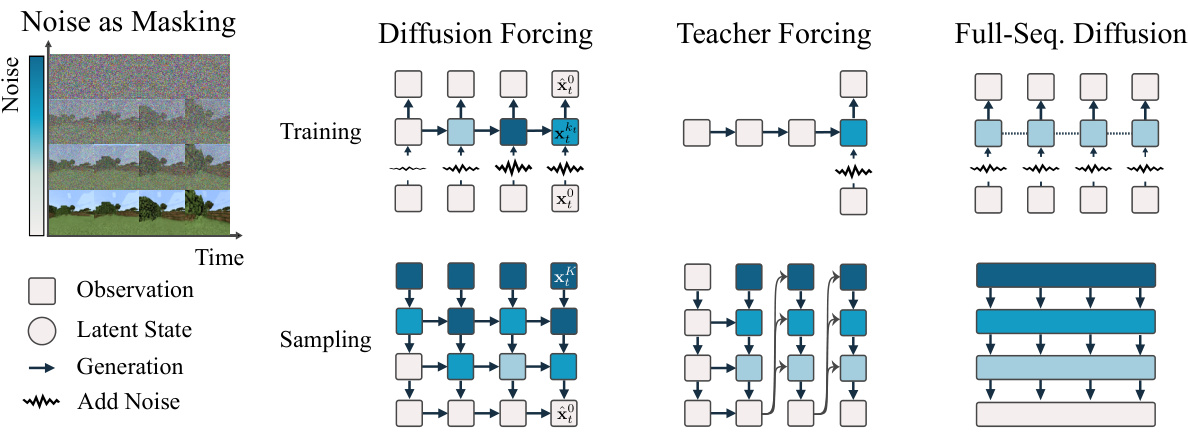

This figure illustrates the capabilities of Diffusion Forcing (DF) in comparison to traditional methods for sequence generation: teacher forcing and full-sequence diffusion. It highlights DF’s advantages in handling guidance, tree search, compositionality, causal uncertainty, and flexible horizons. Teacher forcing excels in autoregressive generation of variable-length sequences but struggles with long-range guidance. Full-sequence diffusion excels at long-range guidance but lacks flexibility in sequence length and struggles with compositional generation and causal uncertainty. DF is positioned as a model combining strengths of both paradigms.

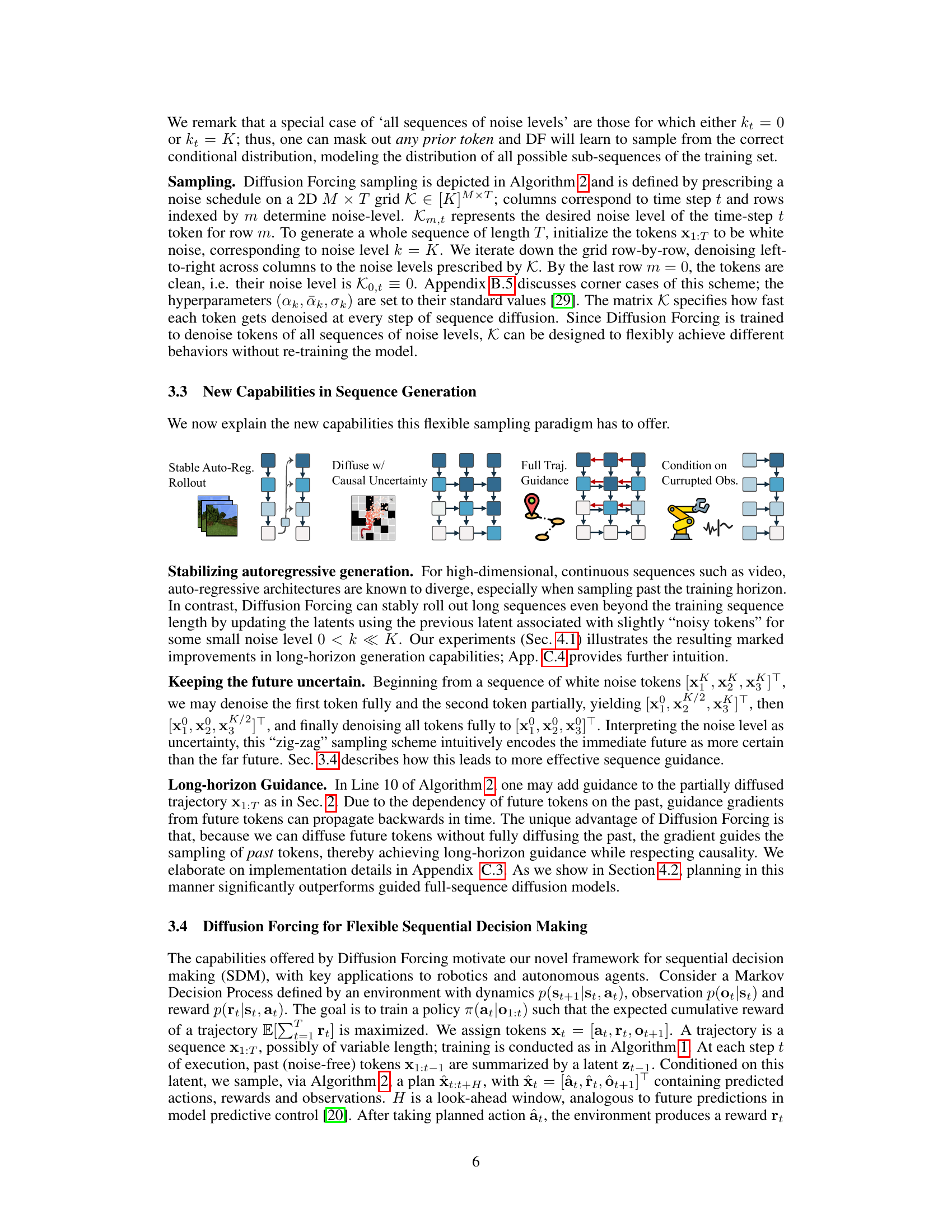

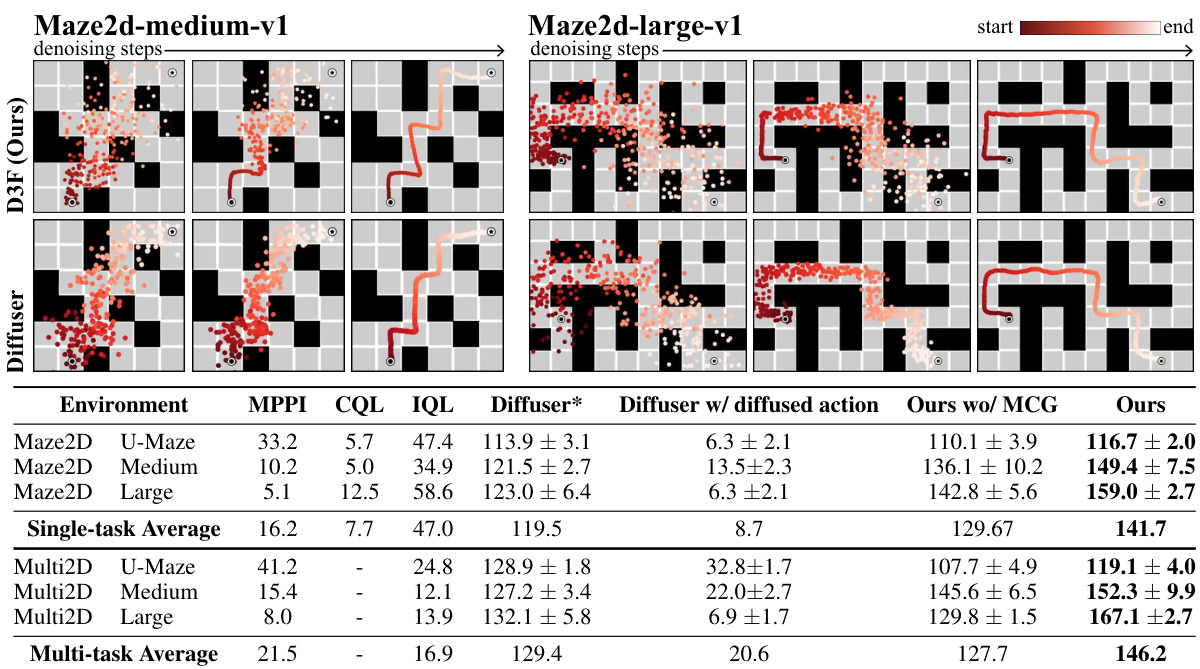

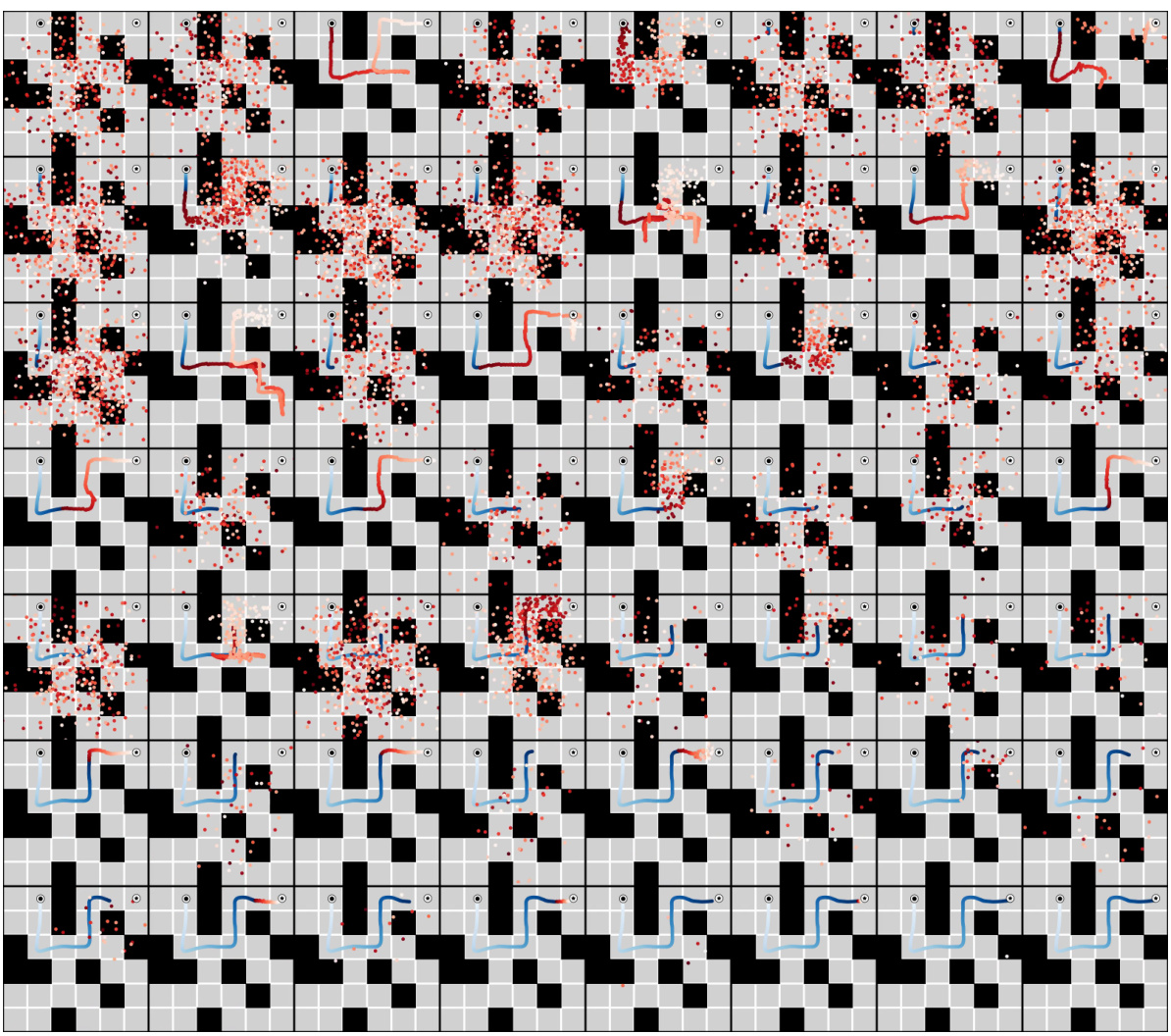

This table presents a comparison of Diffusion Forcing with several baselines on a set of 2D maze planning tasks. The top section illustrates the difference in sampling strategies between Diffusion Forcing and Diffuser, highlighting Diffusion Forcing’s ability to handle causal uncertainty by varying noise levels across time steps. The bottom section shows the quantitative results, demonstrating Diffusion Forcing’s superior performance in terms of average reward compared to the baselines. Note that Diffuser requires a hand-crafted controller to function effectively.

In-depth insights#

Diffusion Forcing#

Diffusion forcing presents a novel training paradigm for sequence generative models. By introducing per-token noise levels during training, it uniquely combines the strengths of next-token prediction (variable-length generation, efficient tree search) and full-sequence diffusion (guidance during sampling, generation of continuous signals). The key innovation lies in its variable-horizon and causal architecture, enabling flexible-length sequence generation and robust long-horizon prediction, particularly valuable for continuous data such as video. Furthermore, it unlocks new sampling and guiding mechanisms such as Monte Carlo Guidance, significantly enhancing performance in complex tasks like decision-making and planning. The method is theoretically grounded, optimizing a variational lower bound on the likelihoods of subsequences, thereby providing a strong mathematical foundation. Its versatility and empirical success across various domains demonstrate its potential as a powerful and flexible framework for sequence generative modeling.

Causal Mechanism#

A causal mechanism, in the context of a research paper, would detail the process by which a cause leads to an effect. It goes beyond simply stating a correlation and delves into the underlying steps, interactions, and factors involved in the causal pathway. A strong explanation would identify intermediate variables, describing how the initial cause influences subsequent steps until the final outcome is reached. The discussion should incorporate temporal dynamics, showing the order and timing of events, as well as potential feedback loops or nonlinear interactions. Furthermore, a robust causal mechanism would address alternative explanations, acknowledging potential confounding factors or rival hypotheses that could account for the observed relationship. Finally, the analysis should consider the generalizability of the mechanism, explaining whether the observed cause-effect relationship would hold across different contexts and populations, and under what conditions.

Empirical Results#

An effective ‘Empirical Results’ section would begin by clearly stating the goals of the experiments. It should then present the experimental setup, including datasets used, evaluation metrics, and baselines for comparison. Detailed results should be presented, possibly using tables or graphs, focusing on the key metrics that address the research questions. Statistical significance testing (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) should be used to demonstrate the reliability of the findings. Crucially, the results section must directly support the paper’s claims and discuss any unexpected results. Limitations of the experiments should be acknowledged, such as dataset biases or limited scope, and the implications of these limitations on the generalizability of the findings should be explored. A thoughtful discussion of the results is key, connecting the findings to the broader research context and highlighting the implications of the work. Visualizations, where appropriate, should be used to enhance understanding and clarity. The discussion should then clearly link the empirical findings back to the paper’s claims, highlighting how the results provide support or lead to new questions. Finally, the ‘Empirical Results’ section must be well-written, using clear and concise language that is easy for a reader to understand. The use of appropriate terminology and a logical structure are essential for communicating the findings effectively.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on Diffusion Forcing are plentiful. Scaling to larger datasets and higher-dimensional data (like higher-resolution video or more complex audio) is crucial, potentially requiring exploration of more efficient transformer-based architectures instead of the current RNN implementation. Investigating the application of Diffusion Forcing to other domains beyond the ones explored (time series, video generation, planning) would uncover its versatility. For example, applying it to tasks involving sequential decision-making in robotics or natural language processing could yield significant advancements. Further theoretical analysis could focus on refining the variational lower bound and investigating conditions for tighter bounds to better understand the model’s behavior. Additionally, exploring novel sampling and guidance schemes within the Diffusion Forcing framework could lead to even more advanced capabilities, enabling more efficient exploration and better control over the generation process. Finally, research into the robustness of Diffusion Forcing to adversarial attacks and noisy data is vital for practical applications, ensuring reliable performance in real-world settings. These diverse avenues of future investigation underscore the significant potential of this innovative training paradigm.

Method Limitations#

A thoughtful analysis of limitations in a research paper’s methodology section requires a nuanced understanding. Focusing solely on technical shortcomings risks overlooking crucial contextual factors. For example, limitations due to computational constraints might be mitigated with increased resources, while limitations stemming from dataset biases are more fundamental and require careful consideration. Assumptions made during model development (e.g., data independence, model capacity) should be explicitly examined, along with their potential impact on the results. The scope and generalizability of the findings also need careful scrutiny. Were the results confined to specific datasets or experimental conditions? If so, this should be clearly articulated along with any reasons for such limitations. Furthermore, a thorough analysis must acknowledge the trade-offs made during method design, considering the choices that were made regarding computational cost, data requirements, and model complexity. A well-written limitations section strengthens a paper by exhibiting transparency and emphasizing the areas ripe for future research. The discussion should proactively address these limitations, acknowledging their potential consequences and proposing strategies for future investigations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

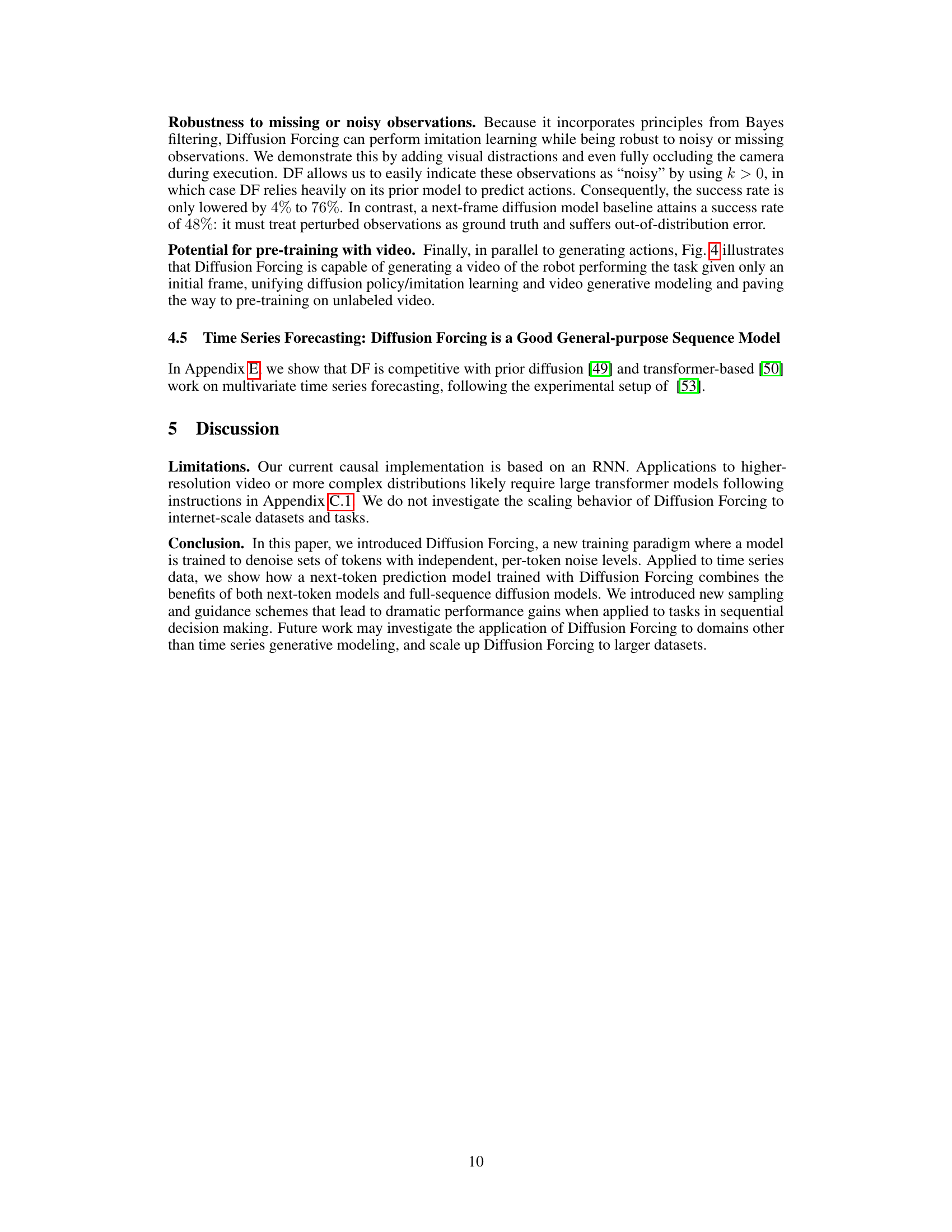

This figure compares three different sequence modeling approaches: Diffusion Forcing, Teacher Forcing, and Full-Sequence Diffusion. It illustrates how each method handles noise and the prediction process during both training and sampling phases. Diffusion Forcing stands out by allowing different noise levels for each token, enabling flexible-length sequence generation. Teacher Forcing uses a ground-truth sequence for prediction, while Full-Sequence Diffusion applies the same noise level to all frames. The figure visually highlights the unique strengths of Diffusion Forcing in terms of noise handling and flexible-length sequence modeling.

This figure illustrates the capabilities of Diffusion Forcing (DF), a novel sequence generative model. It compares DF to traditional methods like teacher forcing and full-sequence diffusion, highlighting DF’s advantages in various applications such as language modeling, planning, and video generation. Specifically, it shows how DF combines the strengths of both autoregressive next-token prediction models (variable-length generation) and full-sequence diffusion models (guidance during sampling).

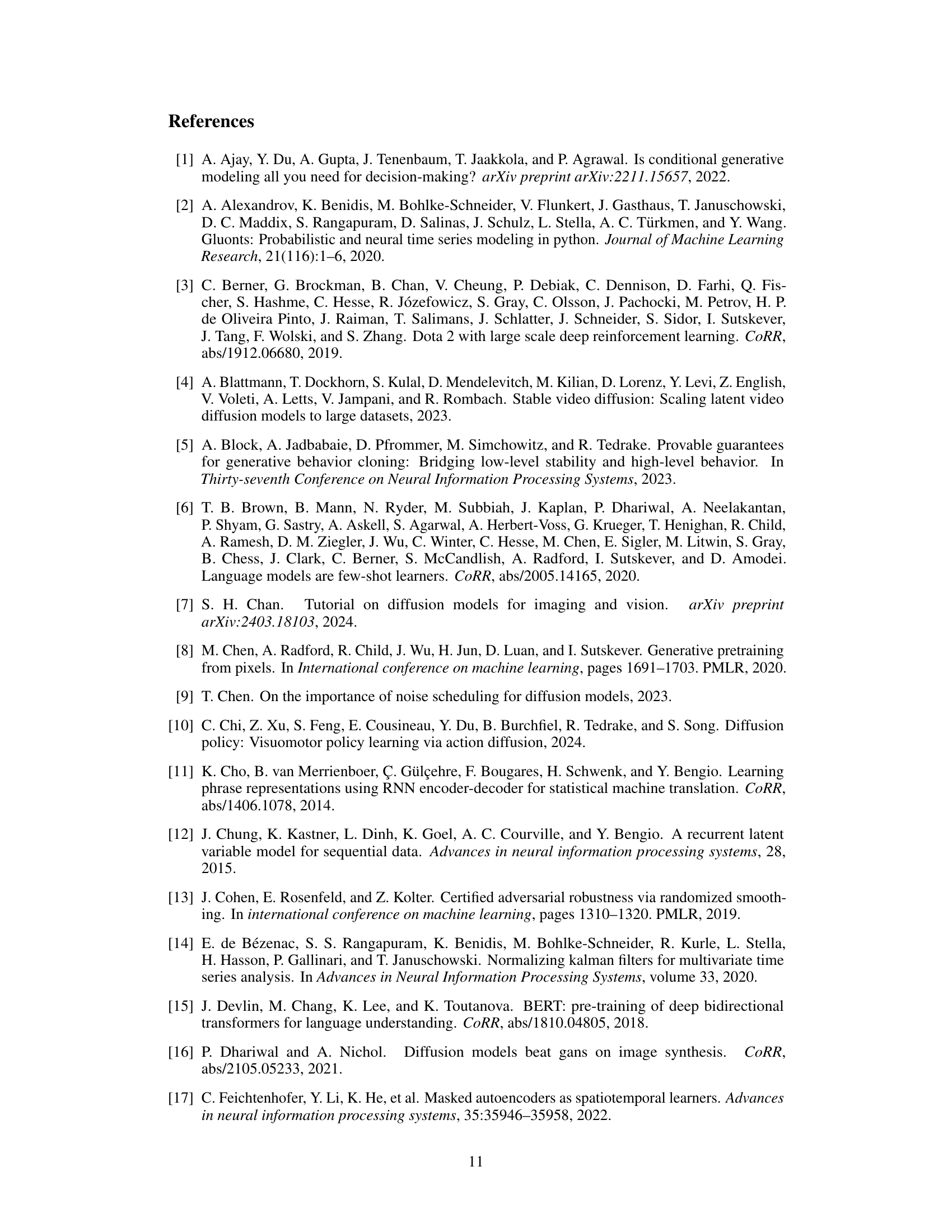

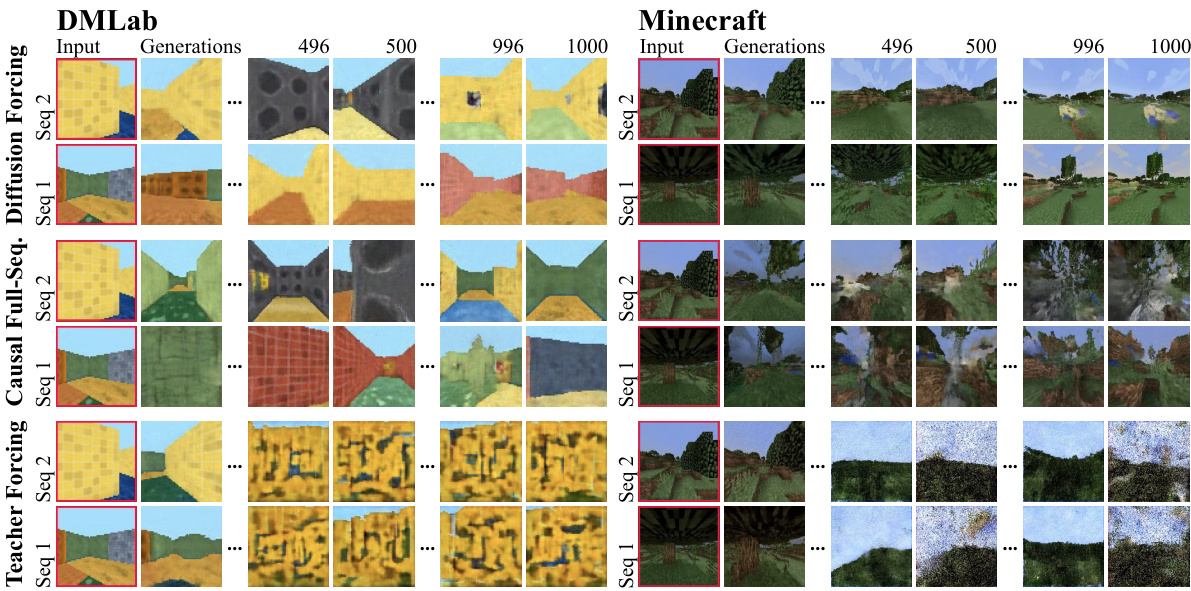

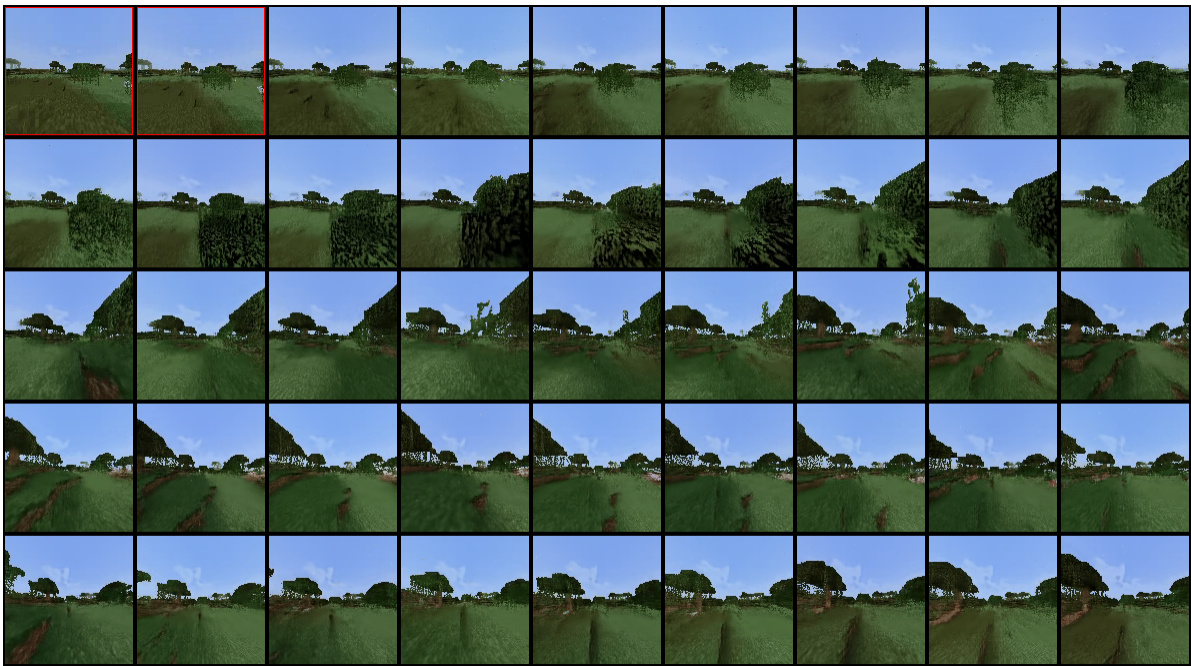

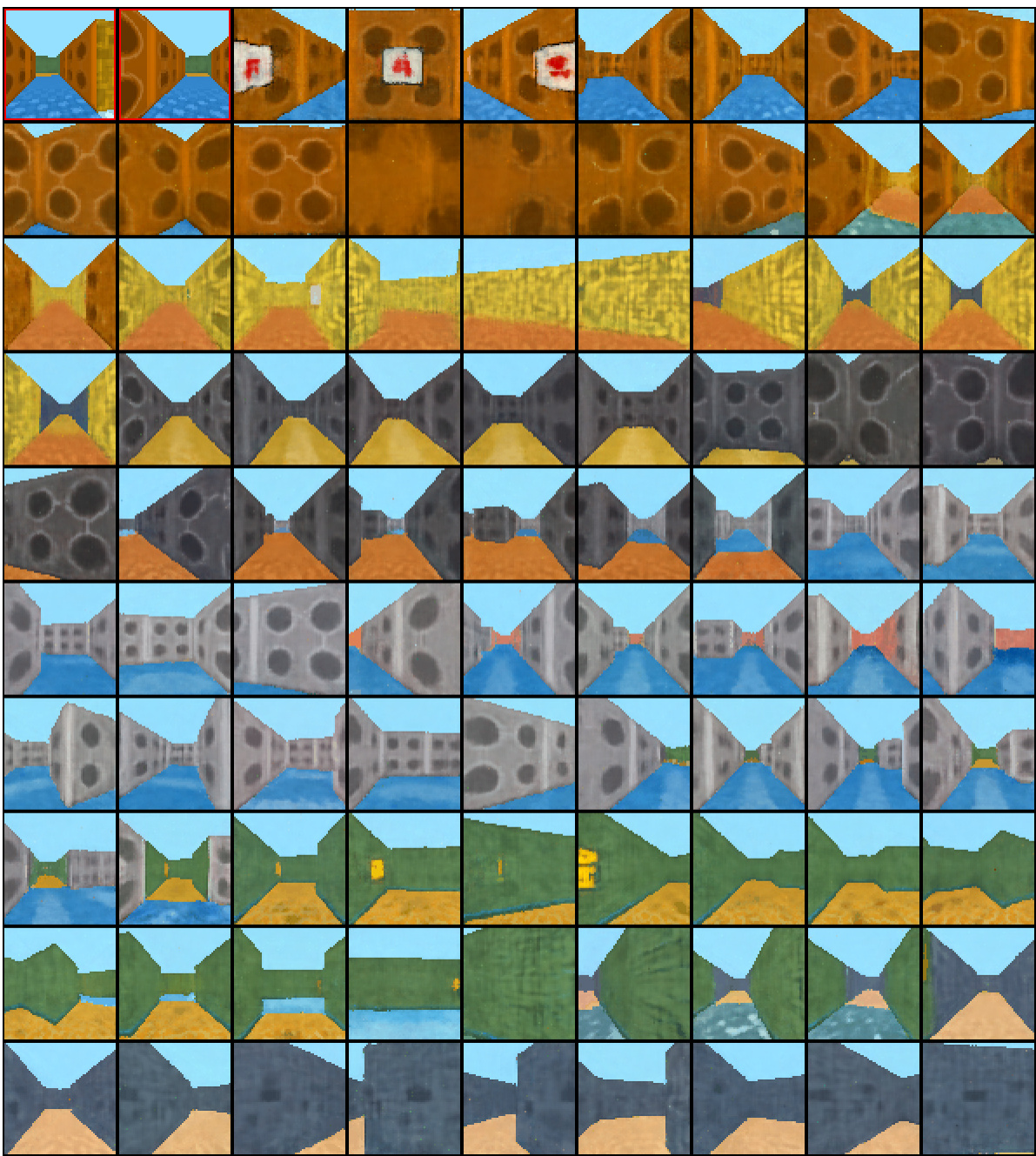

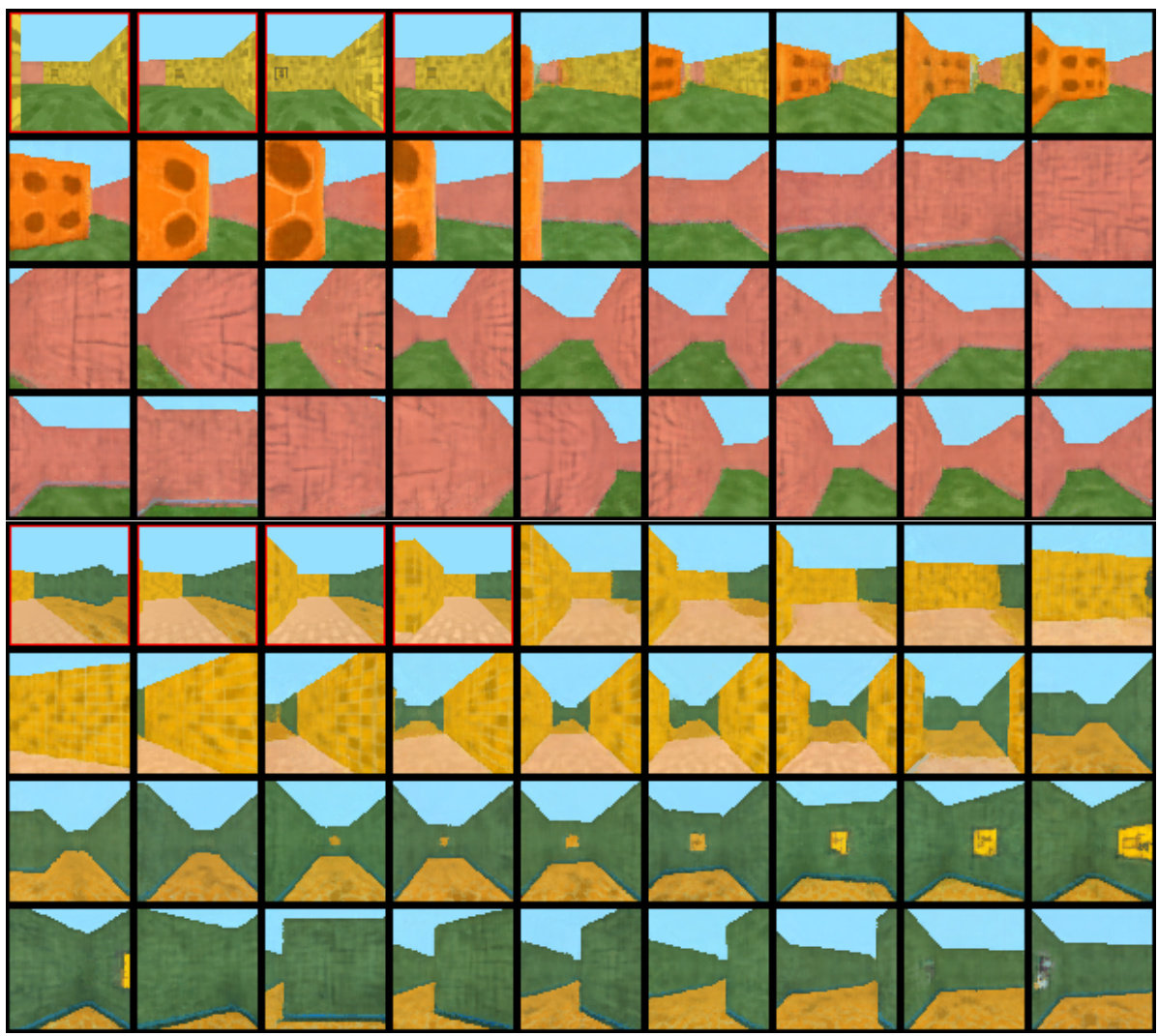

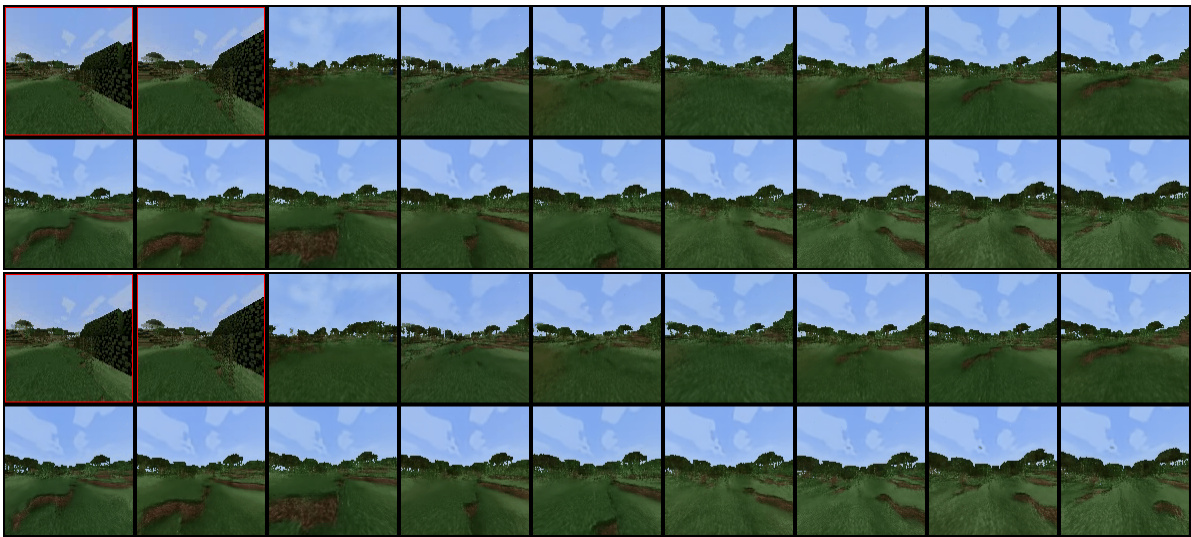

This figure compares the video generation capabilities of three different methods: Teacher Forcing, Causal Full-Sequence Diffusion, and Diffusion Forcing. The figure shows that Diffusion Forcing produces videos that are temporally consistent and do not diverge, even when generating sequences much longer than those seen during training. In contrast, the other two methods produce videos that are either inconsistent or diverge over longer sequences. The red boxes highlight the input frames and the columns show generations of different lengths (496, 500, 996, 1000 frames).

This figure illustrates the capabilities of Diffusion Forcing (DF) by comparing it to traditional methods like teacher forcing and full-sequence diffusion. Teacher forcing, common in autoregressive models, sequentially predicts the next token based on previous tokens, while full-sequence diffusion models the entire sequence jointly. DF combines the strengths of both approaches: variable-length generation and the ability to guide sampling towards desirable trajectories, as indicated by the checkmarks in the diagram. The figure highlights DF’s additional capabilities in guidance, tree search, compositionality, flexible horizons, and causal uncertainty.

This figure demonstrates a real-world robotic task where a robot arm needs to swap the positions of two fruits using a third slot. The initial positions of the fruits are randomized, making it impossible to determine the next steps without remembering the initial configuration. The figure showcases two different scenarios (A and B) with the same initial observation but different desired outcomes, highlighting the need for memory. Additionally, it shows that the model not only generates the actions required for the task but also synthesizes realistic video from a single frame.

This figure illustrates the capabilities of Diffusion Forcing (DF) by comparing it to traditional teacher forcing and full-sequence diffusion methods. Teacher forcing, commonly used in next-token prediction models, is limited in its ability to guide sampling to desirable trajectories and struggles with generating long sequences, especially continuous data like video. Full-sequence diffusion models excel at guiding sampling but lack the flexibility of variable-length generation and compositional generalization. DF combines the strengths of both approaches, offering guidance, variable-length generation, flexible horizons, and compositional generalization, as depicted in the diagram.

This figure illustrates the capabilities of Diffusion Forcing (DF) by comparing it to existing methods for sequence generation: teacher forcing and full-sequence diffusion. Teacher forcing, commonly used in next-token prediction, has limitations in guiding sampling and handling continuous data. Full-sequence diffusion, while capable of guidance, is restricted by its non-causal architecture and fixed sequence length. DF combines the strengths of both approaches, enabling variable-length generation, guidance, and handling of continuous data. The diagram visually represents the unique characteristics of each method.

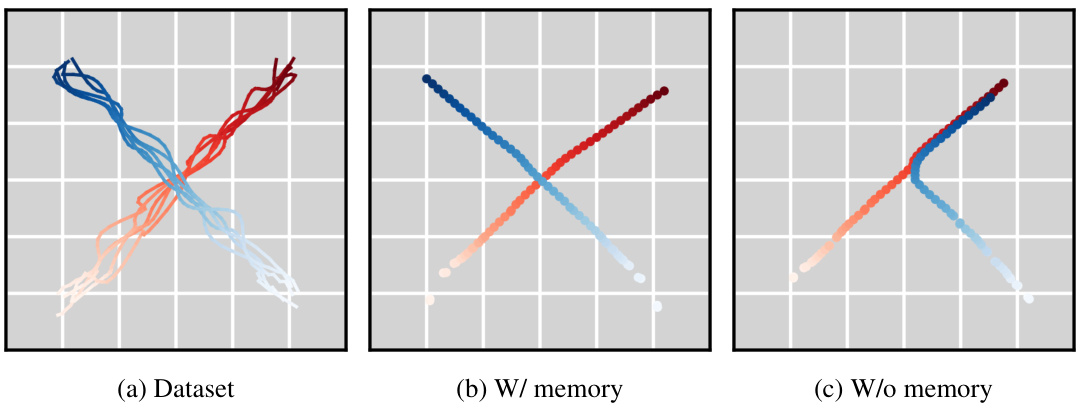

This figure demonstrates the ability of Diffusion Forcing to model the joint distribution of subsequences of trajectories. Panel (a) shows a dataset of trajectories, panel (b) shows samples from the full trajectory distribution using Diffusion Forcing with full memory, and panel (c) shows samples that recover Markovian dynamics when previous states are disregarded.

This figure compares the video generation results of three different methods: Teacher Forcing, Causal Full-Seq Diffusion, and Diffusion Forcing. It shows that Diffusion Forcing produces temporally consistent videos that do not diverge even when generating sequences much longer than those seen during training. In contrast, the other two methods show instability and divergence, especially in longer sequences. The figure highlights the superior performance of Diffusion Forcing in generating long, coherent video sequences.

This figure compares video generation results from three different methods: Teacher Forcing, Causal Full-Sequence Diffusion, and Diffusion Forcing. The results show that Diffusion Forcing produces temporally consistent videos that do not diverge even when generating sequences significantly longer than those seen during training. In contrast, the other methods struggle to generate coherent and temporally consistent videos beyond their training horizon, suggesting that Diffusion Forcing is significantly more robust and capable of generating longer sequences.

This figure compares the video generation results of three different methods: Teacher Forcing, Causal Full-Seq. Diffusion, and Diffusion Forcing. Two example sequences are shown for each method. The results demonstrate that Diffusion Forcing produces temporally consistent videos that do not diverge even when generating sequences much longer than those seen during training, unlike the other two methods. The figure encourages readers to visit the project website to view the video results.

This figure compares the video generation results of three different methods: Teacher Forcing, Causal Full-Sequence Diffusion, and Diffusion Forcing. The results show that Diffusion Forcing produces videos that are temporally consistent and do not diverge, even when generating sequences much longer than those seen during training. In contrast, the other methods produce inconsistent or diverging videos.

This figure shows the results of video generation experiments comparing Diffusion Forcing against teacher forcing and full-sequence diffusion. The top row shows input sequences. The subsequent rows show the video generations produced by each method for two different sequences. Diffusion Forcing’s generations are temporally consistent even when generating video far beyond the length of the training sequences. Teacher Forcing and Full-Sequence Diffusion methods diverge in these long-horizon prediction tasks.

This figure compares the video generation capabilities of three different methods: Teacher Forcing, Causal Full-Sequence Diffusion, and Diffusion Forcing. The figure shows that only Diffusion Forcing produces temporally consistent and non-divergent video generations, even when generating sequences much longer than those seen during training. The other methods either diverge or generate inconsistent results.

This figure compares the video generation results of three different methods: Teacher Forcing, Causal Full-Sequence Diffusion, and Diffusion Forcing. The results show that Diffusion Forcing produces videos that are temporally consistent and do not diverge, even when generating sequences that are much longer than those seen during training. In contrast, the other two methods produce videos that are less temporally coherent and tend to diverge as the sequence length increases.

This figure compares the video generation results of three different methods: Teacher Forcing, Causal Full-Seq Diffusion, and Diffusion Forcing. The figure shows that Diffusion Forcing produces videos that are temporally consistent and do not diverge even when the generated sequence is much longer than the training sequences. In contrast, the other two methods fail to produce consistent and temporally coherent video when generating sequences longer than the training sequences.

This figure shows a real-world robotic manipulation task where a robot arm needs to swap the positions of two fruits (apple and orange) using a third slot. The initial positions of the fruits are randomized. The figure highlights that the same model used for generating the robot’s actions can also synthesize realistic videos from just a single frame. Subfigures (a) and (b) illustrate that identical initial observations can lead to different desired outcomes, depending on the initial placement of the fruits, emphasizing the need for memory in the robot’s planning process.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of Diffusion Forcing with other planning methods on various 2D maze environments. The top part describes the key differences in the sampling approach between Diffusion Forcing and Diffuser, highlighting Diffusion Forcing’s ability to handle causal uncertainty more effectively. The bottom part presents a quantitative comparison of average rewards achieved by different methods, showcasing Diffusion Forcing’s superior performance. Note that Diffuser requires a hand-crafted PD controller to function properly.

This table presents a comparison of Diffusion Forcing with other planning methods on several maze environments. The top part describes the different sampling approaches and how Diffusion Forcing handles causal uncertainty better than the Diffuser baseline. The bottom part shows the quantitative results, demonstrating Diffusion Forcing’s superior performance in terms of average reward, highlighting its ability to effectively utilize generated actions.

Full paper#