↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Neural methods offer efficient solutions to Vehicle Routing Problems (VRPs), but their vulnerability to even minor data perturbations significantly impacts real-world applicability. This is a major challenge in the field because existing solutions, such as adversarial training, often compromise standard generalization for improved robustness. This creates an unfavorable trade-off between accuracy on clean data and resistance to adversarial attacks.

The researchers propose a Collaborative Neural Framework (CNF) that uses ensemble-based adversarial training. The key innovation is a neural router to distribute training instances strategically across multiple models, improving load balancing and collaborative learning. CNF successfully defends against various attacks across different neural VRP methods, also showing enhanced generalization on unseen data. The improved performance validates the effectiveness and versatility of the proposed approach in solving real-world problems that require both robustness and generalizability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because neural methods for vehicle routing problems (VRPs) are increasingly used but suffer from robustness issues. The proposed Collaborative Neural Framework (CNF) offers a novel defense mechanism, directly addressing a significant limitation. This work also opens avenues for improving the generalization of neural methods for combinatorial optimization problems and inspires further research in the robustness of deep learning models for solving discrete optimization problems.

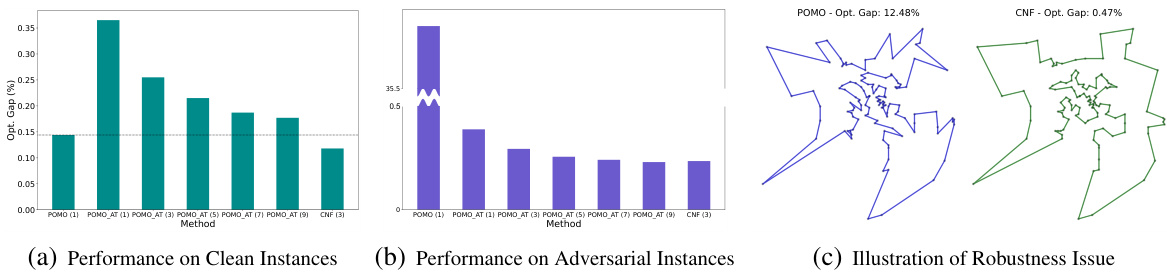

Visual Insights#

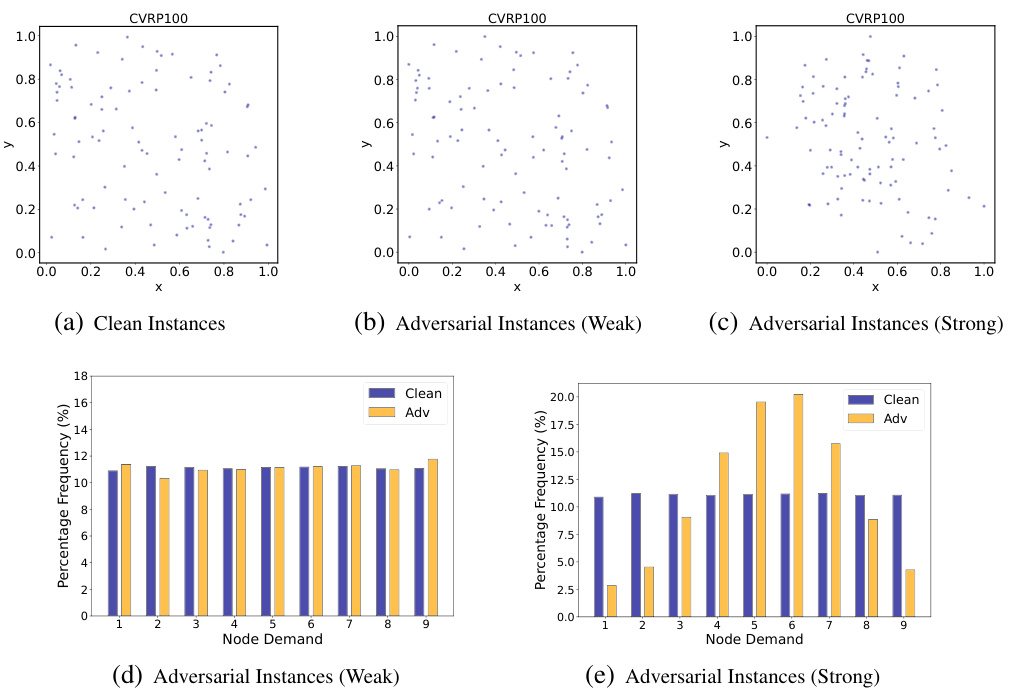

This figure demonstrates the vulnerability of existing neural vehicle routing problem (VRP) methods to adversarial attacks and the trade-off between standard generalization and adversarial robustness. Subfigure (a) shows the performance of the POMO method on clean TSP100 instances, while (b) shows the performance against adversarial attacks from [87]. Subfigure (c) visually compares solutions on adversarial instances. The results highlight that the performance significantly deteriorates on instances with even slight perturbations.

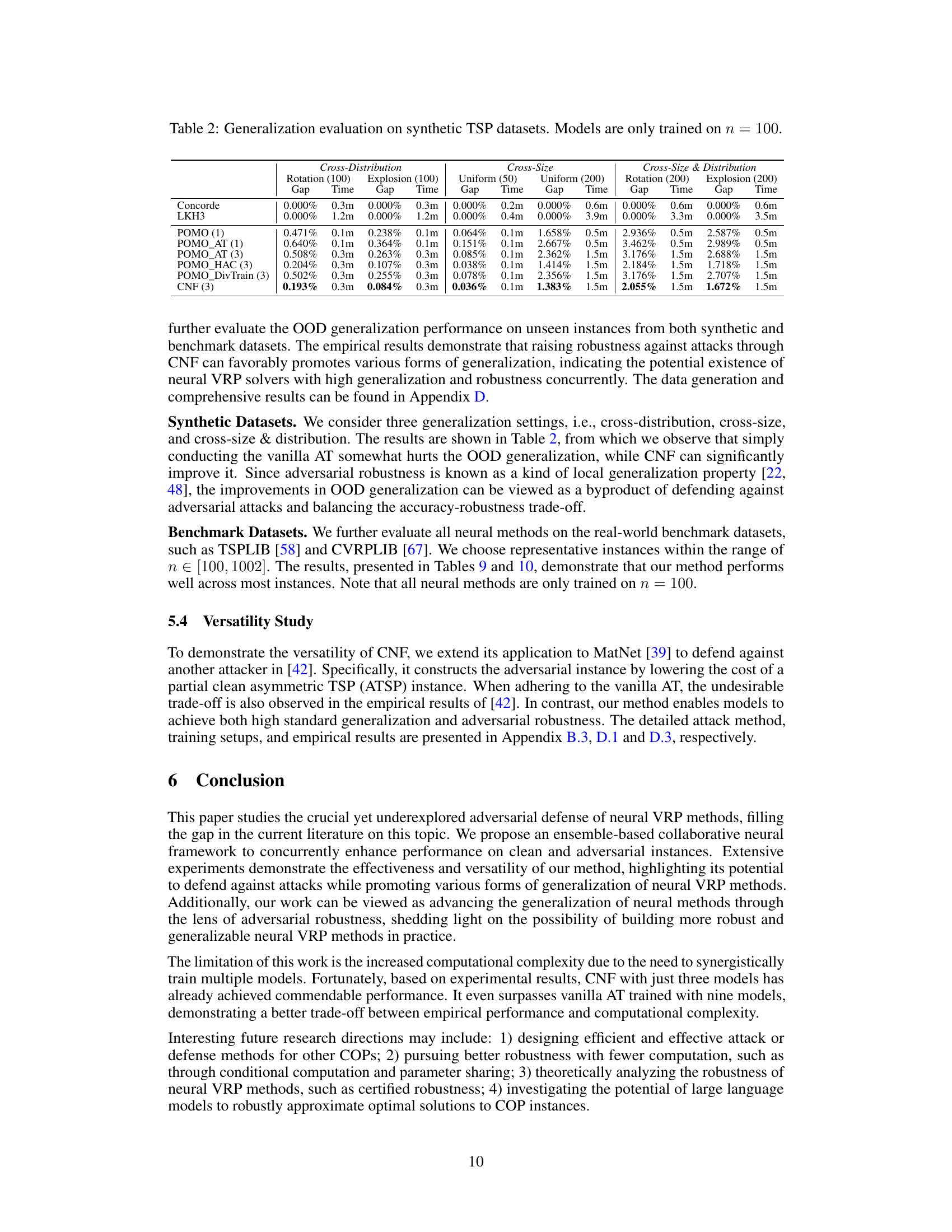

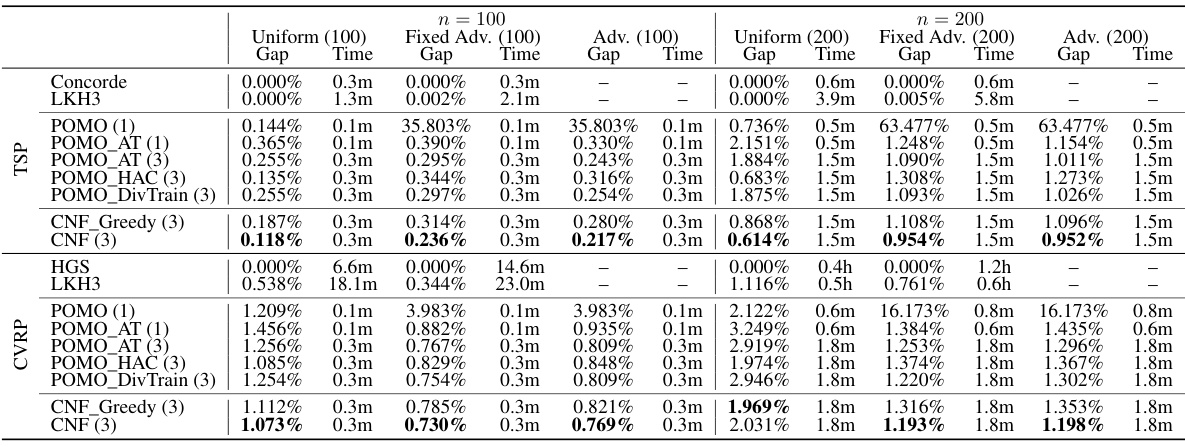

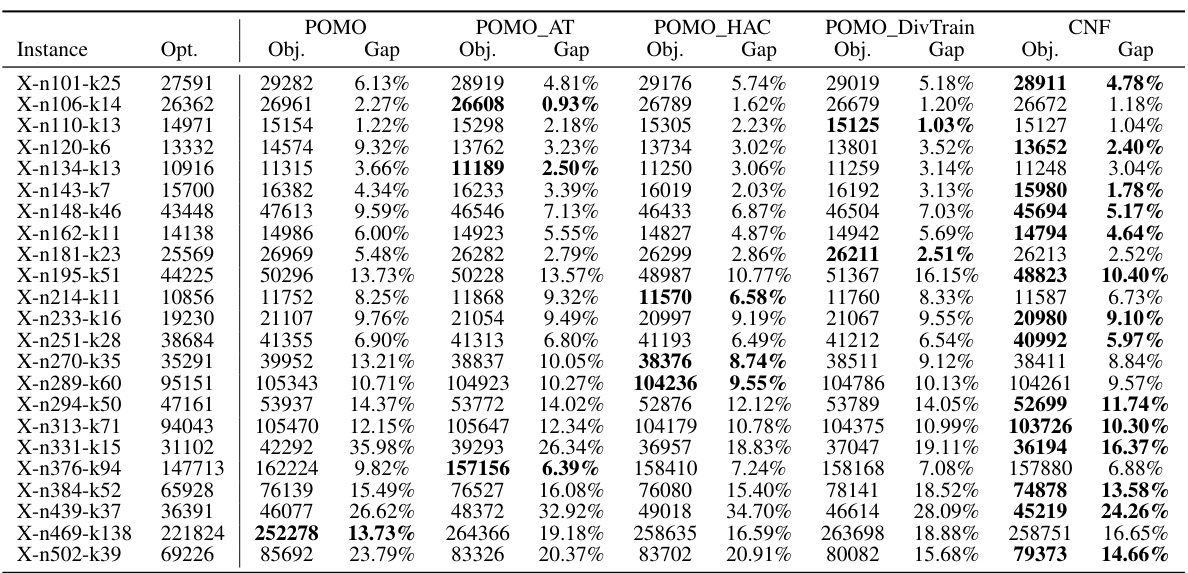

This table presents the performance evaluation results of different methods on 1000 test instances for two problem sizes (n=100 and n=200). The methods compared include traditional solvers (Concorde, LKH3, HGS), a baseline neural method (POMO), and several robust versions of POMO obtained using different adversarial training techniques (POMO_AT, POMO_HAC, POMO_DivTrain) and the proposed collaborative neural framework (CNF). Performance is measured in terms of optimality gap and inference time across clean instances and instances subjected to different adversarial attacks. The number of models used in ensemble methods is indicated in parentheses.

In-depth insights#

Neural VRP Robustness#

Neural vehicle routing problem (VRP) methods, while efficient, suffer from significant robustness issues. Adversarial attacks, involving subtle perturbations to input data, can severely degrade their performance. Existing research primarily focuses on attack methods, generating adversarial instances to expose vulnerabilities. However, defensive mechanisms remain underexplored. Vanilla adversarial training (AT), a common defense, often leads to an undesirable trade-off: improved robustness against attacks comes at the cost of reduced standard generalization on clean data. The paper proposes a novel collaborative neural framework (CNF) to improve robustness by synergistically training multiple models. CNF’s collaborative approach, particularly the global attack strategy and attention-based router, aims to achieve better load balancing and improve performance on both clean and adversarial data. The results demonstrate CNF’s effectiveness in defending against various attacks across different neural VRP methods and show impressive out-of-distribution generalization. The key innovation is the collaborative training, moving beyond individual model improvement to leverage ensemble-based strengths for enhanced robustness.

CNF Framework#

The Collaborative Neural Framework (CNF) is a robust and versatile approach for enhancing the performance of neural vehicle routing problem (VRP) methods. CNF synergistically promotes robustness against adversarial attacks by collaboratively training multiple models, thus mitigating the inherent trade-off between standard generalization and adversarial robustness observed in traditional adversarial training (AT). A key innovation is the attention-based neural router, which intelligently distributes training instances among models, optimizing collaborative efficacy and load balancing. The framework leverages both local and global adversarial instances, creating a more diverse and effective attack for policy exploration. The results demonstrate that CNF consistently improves both standard generalization and adversarial robustness, showcasing its versatility across different neural VRP methods and various attack types. CNF’s impressive out-of-distribution generalization further highlights its potential for practical applications in real-world scenarios.

Adversarial Training#

Adversarial training is a crucial technique for enhancing the robustness of machine learning models, particularly in scenarios involving adversarial attacks. The core idea involves training a model not just on clean data but also on adversarially perturbed instances, which are specifically crafted to mislead the model. This process forces the model to learn more robust representations, becoming less susceptible to carefully designed inputs aiming to cause misclassification. A key challenge in adversarial training is finding the right balance between improving robustness against attacks and maintaining good generalization performance on standard, unperturbed data. Overly aggressive adversarial training can lead to a decrease in standard accuracy, highlighting the need for careful parameter tuning and thoughtful algorithm design. There are numerous variations of adversarial training techniques, each with its advantages and disadvantages in terms of computational efficiency and robustness. Another important consideration is the choice of attack method used to generate adversarial examples; different attacks have varying degrees of effectiveness and difficulty, impacting the ultimate robustness of the resulting model. Despite these challenges, adversarial training remains a valuable tool for building more secure and dependable machine learning systems, especially in high-stakes applications where robustness to malicious inputs is paramount.

Ablation Experiments#

Ablation experiments systematically remove or alter components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a research paper, this involves carefully isolating variables to understand their impact on the overall performance. Well-designed ablation studies are crucial for establishing causality and disentangling the effects of different model features. By gradually removing components and observing the changes in performance metrics, researchers can determine which aspects of their approach are essential for success and which are not. This process is particularly valuable when dealing with complex models or methods where multiple interacting factors affect the final output. Analyzing the results of ablation experiments allows for a deeper understanding of the model’s behavior and helps to identify areas for improvement or future work. A strong ablation study rigorously tests different configurations, providing convincing evidence that supports the claims made in the paper. The lack of a thorough ablation study is a significant weakness in a research paper as it limits the confidence one can place in the results and the conclusions drawn. A comprehensive approach involves not only removing components but also examining the effects of varying certain parameters, further strengthening the analysis and the credibility of the findings.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of collaborative training is crucial, potentially through techniques like parameter sharing or conditional computation. Another key area is developing more sophisticated attack and defense methods, especially those that generalize across different VRP variants and problem sizes. Theoretical analysis of robustness, such as establishing certified robustness bounds, is needed to provide stronger guarantees. Finally, it would be valuable to investigate the potential of large language models for approximating optimal solutions to COP instances, potentially leveraging their ability to learn complex patterns and heuristics from large datasets.

More visual insights#

More on figures

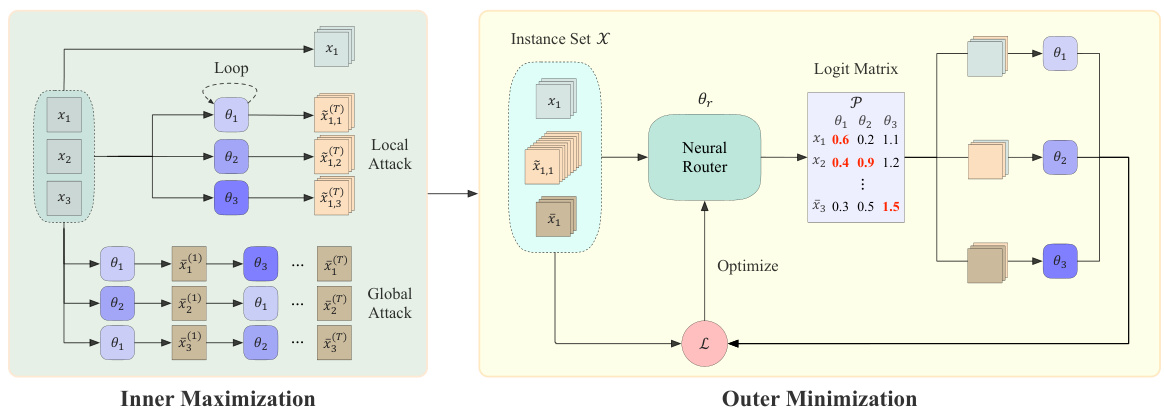

This figure illustrates the Collaborative Neural Framework (CNF). The framework uses multiple models (θ₁, θ₂, θ₃) to improve robustness against adversarial attacks. The inner maximization step generates adversarial instances (local and global), while the outer minimization step uses a neural router (θr) to distribute these instances among the models for more efficient and effective training. The neural router’s goal is to improve the overall collaborative performance.

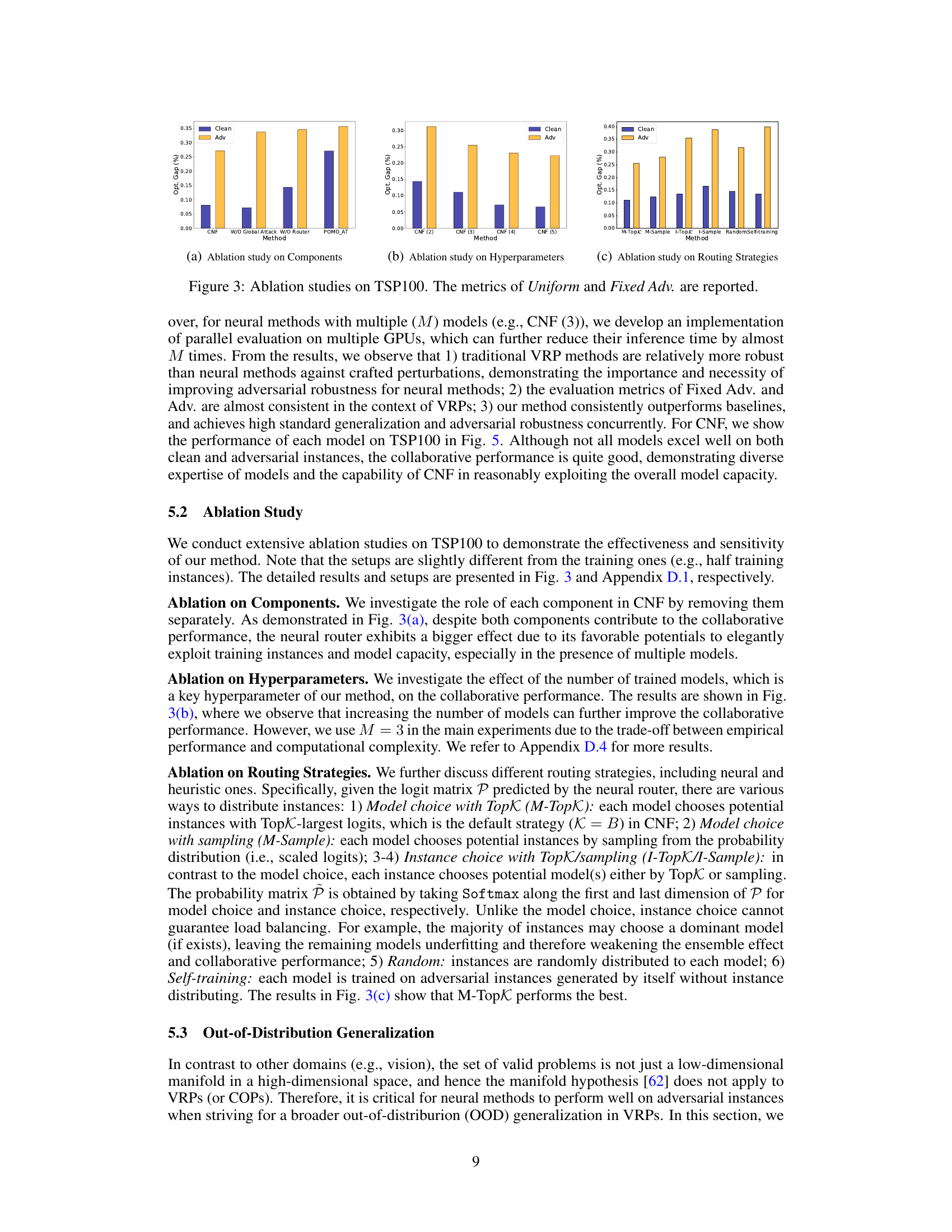

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted on the TSP100 dataset to analyze the impact of different components and hyperparameters within the Collaborative Neural Framework (CNF). Subfigure (a) shows the effect of removing the global attack mechanism and the neural router. Subfigure (b) demonstrates how the number of trained models influences performance. Subfigure (c) compares various routing strategies for distributing training instances among the models, including those based on top-K selection and sampling.

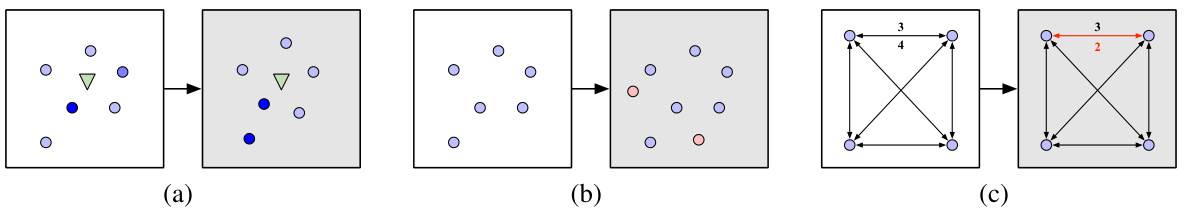

This figure shows examples of adversarial instances generated by three different attack methods described in the paper. Each subfigure illustrates a different attack strategy: (a) perturbing node attributes (node demands in this case) in a Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem (CVRP) instance; (b) inserting new nodes into a Traveling Salesperson Problem (TSP) instance; (c) reducing the cost of edges in an Asymmetric TSP instance. The gray nodes represent the adversarial instances, highlighting how these attacks modify the original clean instances.

This figure shows three different distributions of nodes for generating TSP instances. (a) Uniform distribution shows nodes randomly scattered across a square area. (b) Rotation distribution shows nodes clustered, as if rotated from a uniform distribution. (c) Explosion distribution shows nodes distributed with a void in the center, simulating an explosion effect. These different node distributions provide varying levels of complexity for testing the robustness of the neural VRP methods.

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted on the TSP100 dataset to analyze the impact of different components and hyperparameters within the Collaborative Neural Framework (CNF). The ablation studies assess the model’s performance on both clean instances (‘Uniform’) and adversarial instances (‘Fixed Adv.’). Subplots (a), (b), and (c) show the effects of removing components (global attack and neural router), varying the number of models, and testing different instance routing strategies, respectively, demonstrating the importance of each component and design choice for improving robustness and generalization.

The left panel of the figure shows the performance of each individual model in the ensemble, compared to the overall performance of the ensemble. The right panel illustrates how the neural router assigns training instances to each of the models. The color intensity indicates the probability that an instance will be assigned to a model for training. This visualization helps to understand the learned routing policy and its impact on load balancing across the models.

More on tables

This table presents the performance comparison of various methods (traditional and neural) on three different scenarios: clean instances, instances with fixed adversarial attacks, and instances with adversarial attacks generated against the specific model. It evaluates the optimality gap (percentage difference from the optimal solution) and the inference time for each method across different problem sizes (n=100 and n=200) for TSP and CVRP. The results show the impact of the collaborative neural framework (CNF) proposed in the paper compared with baseline methods.

This table presents the results of a robustness study on the DIMES method for solving the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) with 100 cities. It compares the performance of DIMES using different search strategies (greedy, sample, Monte Carlo tree search, and active search) on both clean and adversarial instances (Fixed Adv.). The ‘Gap’ column represents the difference between the solution cost obtained by DIMES and the optimal solution cost, expressed as a percentage. The ‘Time’ column indicates the computation time required for each method. The table demonstrates the effect of different search methods on the robustness of DIMES to adversarial attacks.

This table presents the performance comparison of various methods on 1000 test instances of TSP and CVRP problems. The methods compared include traditional optimization solvers (Concorde, LKH3, HGS) and neural network-based methods (POMO, POMO_AT, POMO_AT (3), POMO_HAC (3), POMO_DivTrain (3), CNF_Greedy (3), CNF (3)). The evaluation metrics are optimality gap and inference time. The optimality gap represents the difference between the obtained solution cost and the optimal solution cost, showing the solution quality. The table shows performance on clean instances and adversarial instances generated by various attack methods (Uniform, Fixed Adv, Adv) to assess the robustness of different methods. The number in brackets indicates the number of models used in ensemble-based methods.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on 1000 test instances of TSP and CVRP problems, including traditional methods (Concorde, LKH3, HGS) and neural methods (POMO, POMO_AT, POMO_HAC, POMO_DivTrain, CNF). The performance metrics shown are optimality gap and inference time. Results are shown for clean instances and instances with adversarial attacks generated using uniform and fixed adversarial attacks and adversarial attacks based on the tested model. The table allows readers to directly compare the robustness and efficiency of various methods against different adversarial attacks.

This table presents the performance comparison of various methods on 1000 test instances of TSP and CVRP problems. The methods include traditional solvers (Concorde, LKH3, HGS) and neural methods (POMO, POMO_AT, POMO_AT (3), POMO_HAC (3), POMO_DivTrain (3), CNF_Greedy (3), CNF (3)). The performance is evaluated under three scenarios: clean instances, instances with fixed adversarial attacks, and instances with adaptive adversarial attacks. For each method and scenario, the optimality gap and inference time are reported. The numbers in brackets indicate the number of models used in ensemble methods.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on 1000 test instances of TSP and CVRP problems with different sizes (n=100 and n=200). The methods compared include traditional optimization solvers (Concorde, LKH3, HGS), the baseline neural VRP method (POMO), and various robust versions of POMO incorporating different defense strategies (POMO_AT, POMO_HAC, POMO_DivTrain). The proposed CNF method is also included for comparison. The table shows the optimality gap (percentage difference between obtained solution and the optimal solution) and the inference time for each method. Separate results are presented for clean instances and instances that have been adversarially perturbed using different attacks, namely uniform, fixed adversarial, and adversarial attacks.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on various TSP and CVRP instances. The methods compared include traditional optimization solvers (Concorde, LKH3, HGS), a baseline neural VRP method (POMO), and several variations of POMO incorporating adversarial training techniques (POMO_AT, POMO_HAC, POMO_DivTrain). The proposed CNF method is also included. Performance is measured by the optimality gap (percentage difference between the solution cost and the optimal cost) and the inference time. Different adversarial attack methods are tested against each method (Uniform, Fixed Adv., Adv.), representing variations in the difficulty of the test cases.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on 1000 test instances of TSP and CVRP problems. The methods compared include traditional solvers (Concorde, LKH3, HGS), a baseline neural method (POMO), and several variations of the baseline incorporating adversarial training techniques (POMO_AT, POMO_HAC, POMO_DivTrain). The proposed method (CNF) is also included. Performance is evaluated on three types of instances: clean instances, instances with fixed adversarial attacks, and instances with adaptive adversarial attacks. The results show the optimality gap (percentage difference between the solution found and the optimal solution) and the computation time for each method.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on 1000 test instances of TSP and CVRP problems with various attack settings (clean, uniform adversarial, fixed adversarial, and adaptive adversarial). The methods compared include traditional solvers (Concorde, LKH3, HGS), the baseline neural method (POMO), and variants incorporating adversarial training (POMO_AT, POMO_HAC, POMO_DivTrain), as well as the proposed collaborative neural framework (CNF). The table shows the optimality gap and inference time for each method and problem type. The bracket indicates the number of models used for ensemble methods.

Full paper#