↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are becoming increasingly prevalent in various applications, yet their internal mechanisms remain largely mysterious. Understanding how these models process information and make predictions is a key challenge. This paper tackles this challenge by investigating the computational structure inherent in LLMs during training.

This study proposes a novel framework grounded in optimal prediction theory. It leverages the “mixed-state presentation” to predict and then empirically demonstrate that belief states, representing the model’s understanding of the data-generating process, are linearly encoded in the residual stream of transformers. The research uses well-controlled experiments with different data-generating processes to validate its predictions, even demonstrating that intricate fractal belief state geometries are accurately represented. These findings shed light on how transformers learn and encode information beyond the immediate next-token prediction.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This research is crucial because it provides a novel framework for understanding the internal workings of large language models (LLMs). By connecting the structure of training data to the geometric structure of activations within LLMs, it offers new insights into how these models learn and make predictions. This has significant implications for enhancing the interpretability, trustworthiness, and efficiency of LLMs, which are increasingly being used across various domains.

Visual Insights#

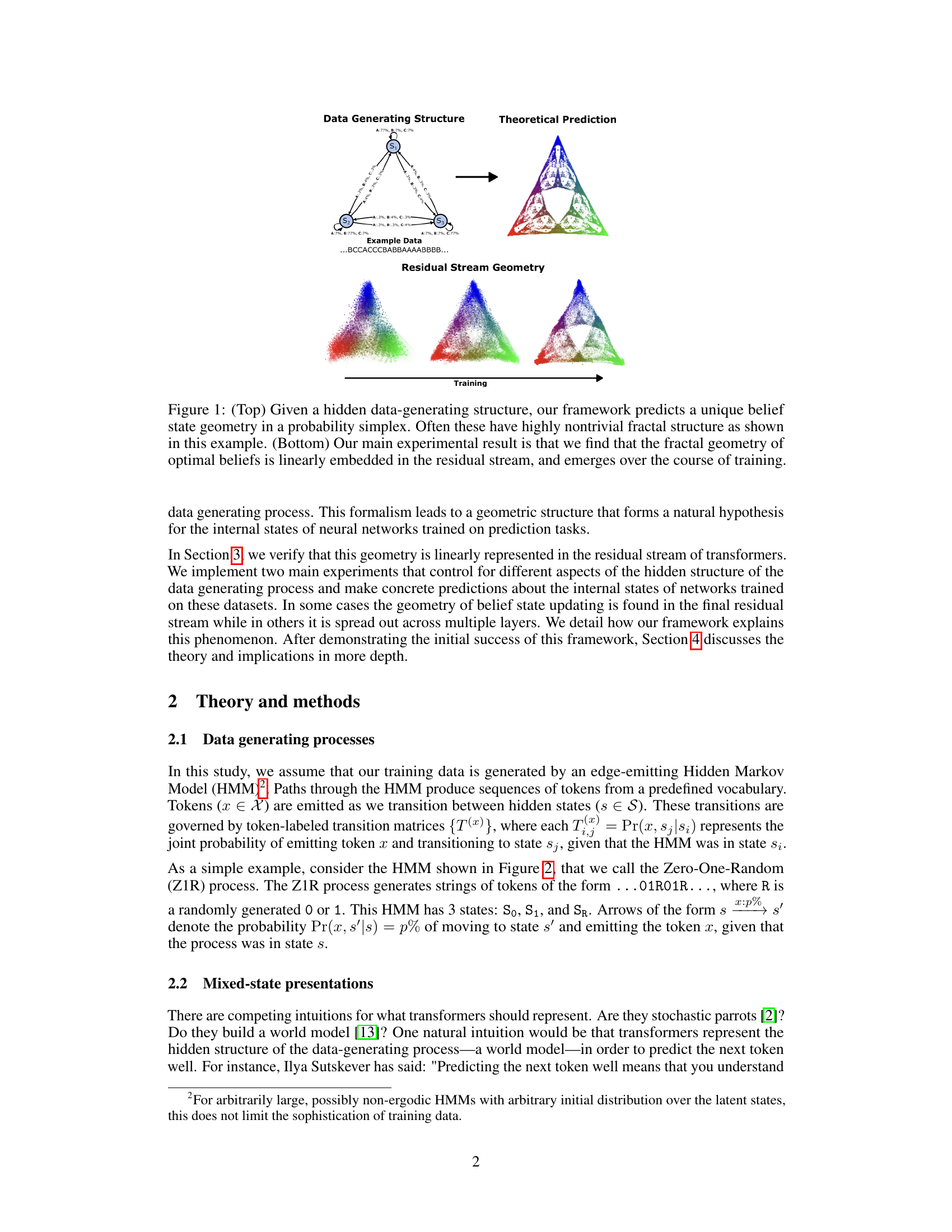

This figure demonstrates the core idea of the paper: that the geometry of belief states, as predicted by the theory of optimal prediction, is linearly represented in the residual stream of transformers. The top panel shows an example of how a hidden data-generating structure (a Hidden Markov Model) leads to a theoretical prediction of a specific belief state geometry in a probability simplex. The bottom panel illustrates the key experimental finding: the trained transformer’s residual stream activations linearly capture this predicted fractal geometry.

In-depth insights#

Belief State Geometry#

The concept of “Belief State Geometry” offers a novel perspective on understanding the internal workings of transformer models. It posits that the way a transformer updates its beliefs about the underlying data-generating process is reflected in the geometric structure of its activation patterns. This geometry isn’t arbitrary; it’s predicted by the theory of optimal prediction and directly linked to the meta-dynamics of belief updating. The key insight is that this geometry, even when highly complex (fractal), is linearly embedded within the model’s residual stream. This allows researchers to infer belief states directly from the model’s activations. Furthermore, the study demonstrates that these belief states capture information extending beyond the immediate next-token prediction, revealing a richer, more comprehensive internal model of the data than previously assumed. This framework provides a powerful tool for analyzing and interpreting the internal representations of transformer models, moving beyond simple next-token prediction and offering a deeper understanding of their internal mechanisms.

Transformer Internals#

The heading ‘Transformer Internals’ suggests an exploration into the inner workings of transformer networks. A deep dive would likely investigate the attention mechanism, detailing its role in weighting input tokens and enabling the model to focus on relevant information. Analysis of self-attention versus cross-attention would highlight the differences in how the model processes information within a single sequence versus between different sequences. Furthermore, the discussion might cover the positional encoding schemes employed, examining how the model incorporates sequential information, and the impact of different techniques (e.g., absolute vs. relative positional embeddings). Layer normalization and its effect on training stability and performance would also be a key component, as well as the architecture of the feed-forward networks between the attention layers. Ultimately, understanding the interplay of these components provides crucial insight into how transformers achieve their remarkable performance in tasks such as natural language processing.

Optimal Prediction#

Optimal prediction, in the context of the provided research paper, is a cornerstone concept framing the investigation of how transformer models learn to represent belief states. It’s not merely about predicting the next token, but rather about understanding the underlying data-generating process and how an observer updates their beliefs about its hidden states given sequential observations. The framework grounds itself in computational mechanics, which suggests that optimal prediction necessitates the internal representation of a belief state geometry within the model. This geometry, often having a complex fractal structure, directly reflects the meta-dynamics of belief updating, revealing the model’s internal representation of information beyond just local next-token predictions. The study explores how belief states, linearly embedded within transformer residual streams, capture essential aspects of future prediction, showcasing the importance of understanding the geometric structure of belief updating for interpreting transformer behaviors and their ability to extrapolate beyond training data.

Fractal Belief States#

The concept of “Fractal Belief States” in the context of transformer neural networks suggests that the internal representations of belief, as the model processes sequential data, exhibit fractal-like geometry. This means that the structure of beliefs at different scales of granularity would share similar patterns. The fractal nature implies a complex, self-similar organization of beliefs, where smaller belief structures recursively mirror larger ones. This self-similarity contrasts with simpler, linear models of belief updating, providing a richer internal model that might explain the unexpected capabilities of transformer models. This fractal geometry likely arises from the inherent complexity of the data itself and the model’s optimal prediction strategy, reflecting the hierarchical structure and long-range dependencies in sequential data. The research might suggest that understanding these fractal belief states is key to unlocking a deeper understanding of the internal workings of transformers and perhaps their emergent abilities.

Future Research#

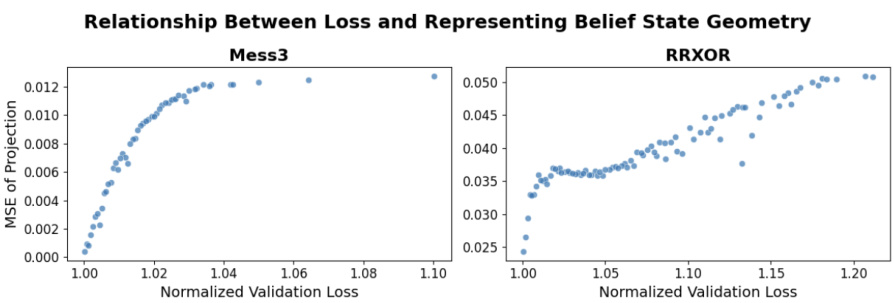

The paper’s ‘Future Research’ section would ideally explore several key areas. First, it should delve into the scalability of the belief state geometry framework to larger, more realistic models and datasets. Addressing the high-dimensionality of belief states in complex systems like natural language processing is crucial. This would involve investigating how compression and approximation techniques could maintain the integrity of the belief state geometry. Second, a more in-depth investigation into the relationship between belief states and features, bridging the gap between computational mechanics and interpretability techniques used in deep learning research, is needed. Exploring the nuanced mapping between belief states and specific deep learning model features remains a significant challenge that could unlock new understanding of model behavior. Finally, analyzing how belief state geometry changes over time during training in non-stationary or non-ergodic processes could provide further insights into the dynamics of belief updates and model learning. Studying various architectures beyond transformers and investigating the generalization of belief state geometry representation across different models and tasks will further solidify the framework’s applicability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

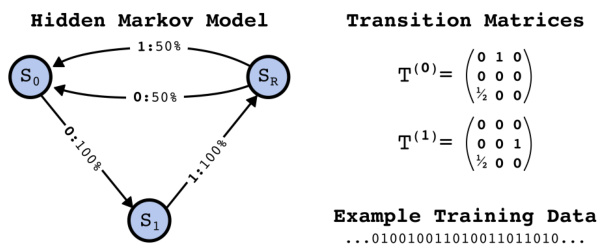

This figure illustrates a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) with three hidden states (S0, S1, and SR) and its corresponding transition matrices (T(0) and T(1)). The HMM generates sequences of tokens (0 and 1) based on its transition probabilities between the states. The left side visually represents the HMM’s structure, showing the states and transition probabilities between them. The right side shows the transition matrices, which are numerical representations of these probabilities. The bottom part displays an example of a sequence of tokens generated by the HMM, demonstrating how the model produces data.

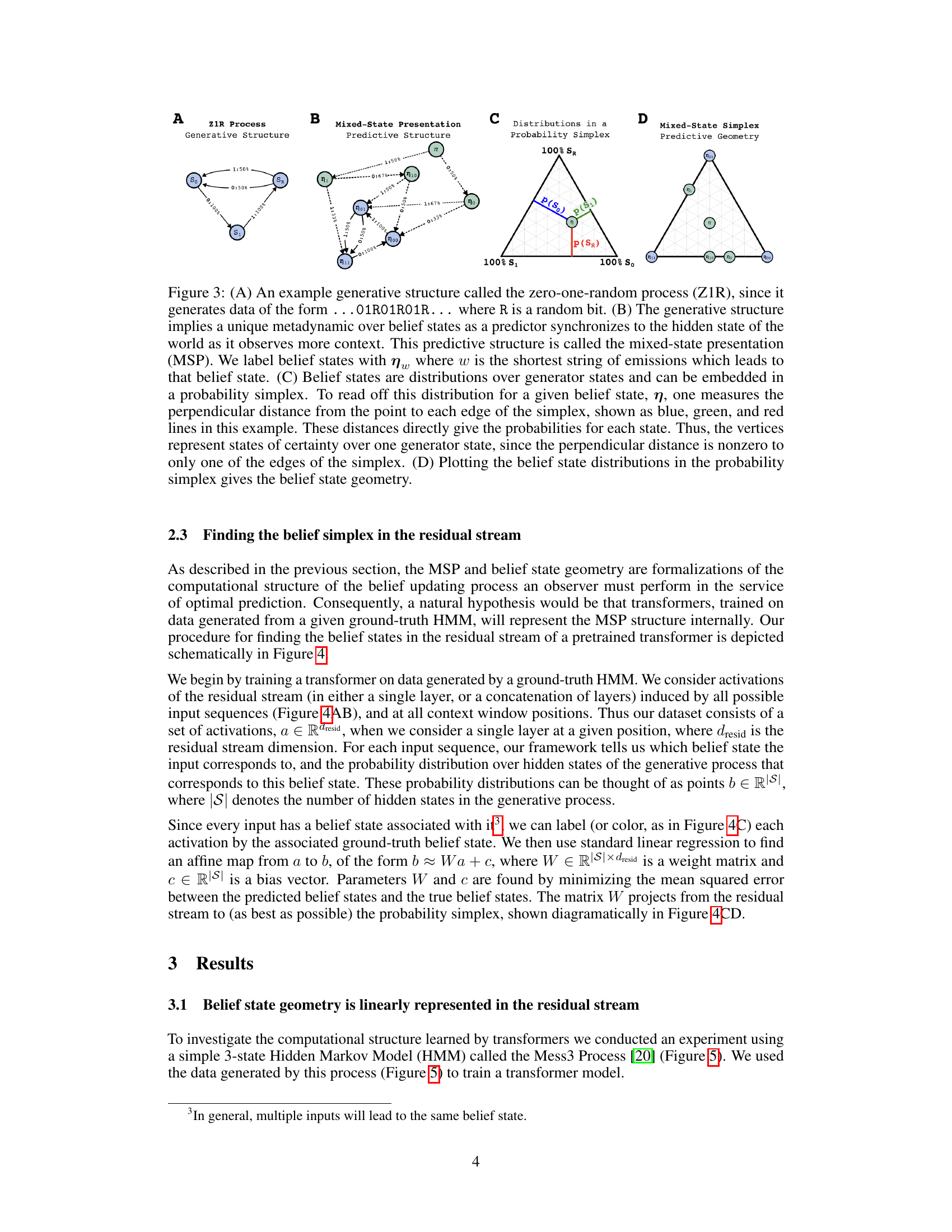

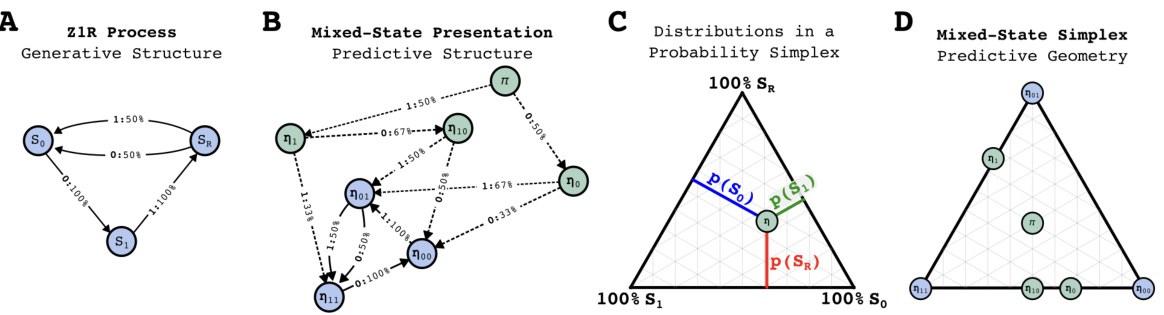

This figure illustrates the concept of mixed-state presentation (MSP) using the Zero-One-Random (Z1R) process as an example. It demonstrates how a generative model’s structure (A) leads to a unique metadynamic of belief state updating (B), which can be visualized geometrically in a probability simplex (C, D). Panel (C) shows how probabilities for different generator states are read off from the simplex, and panel (D) displays the resulting belief state geometry, a crucial concept for the paper’s theoretical framework.

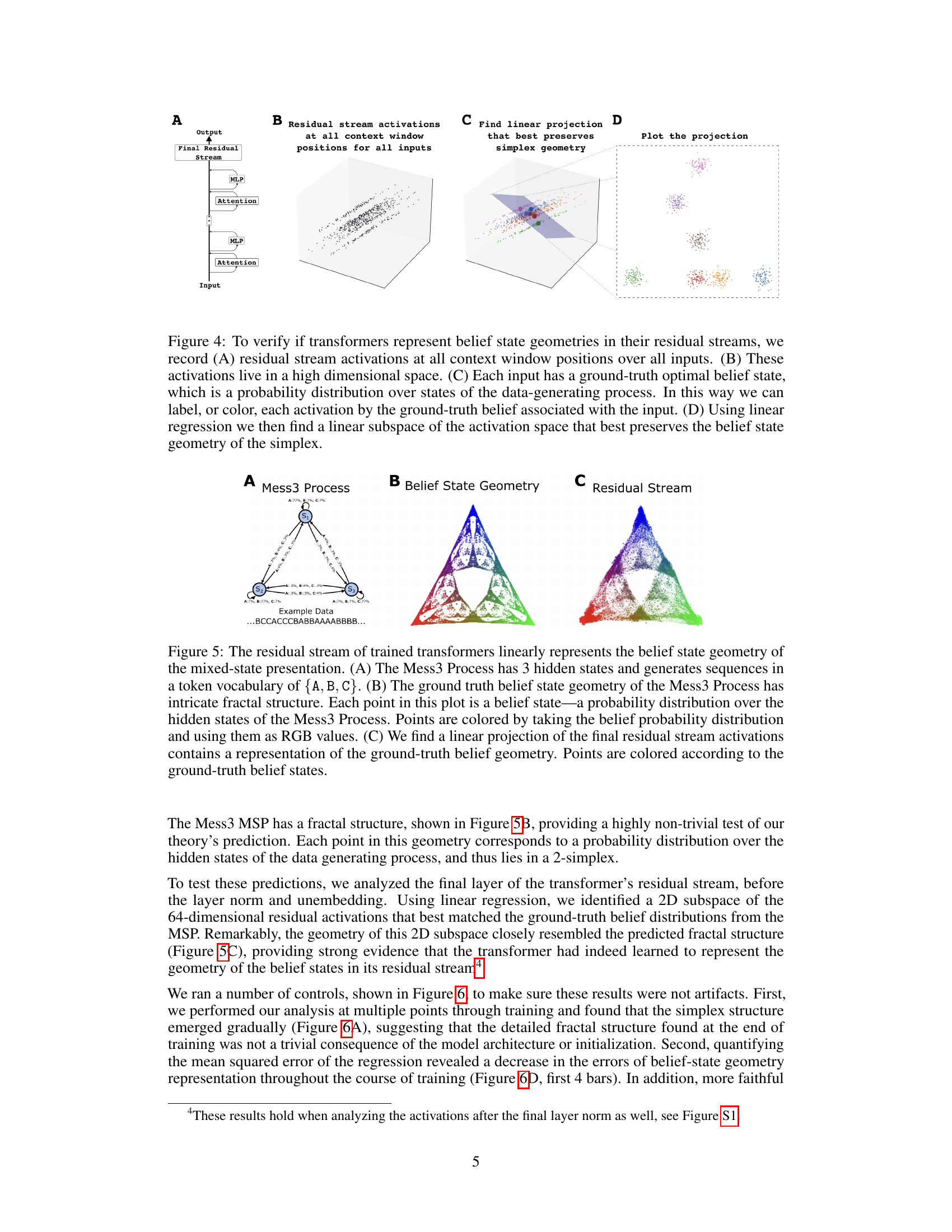

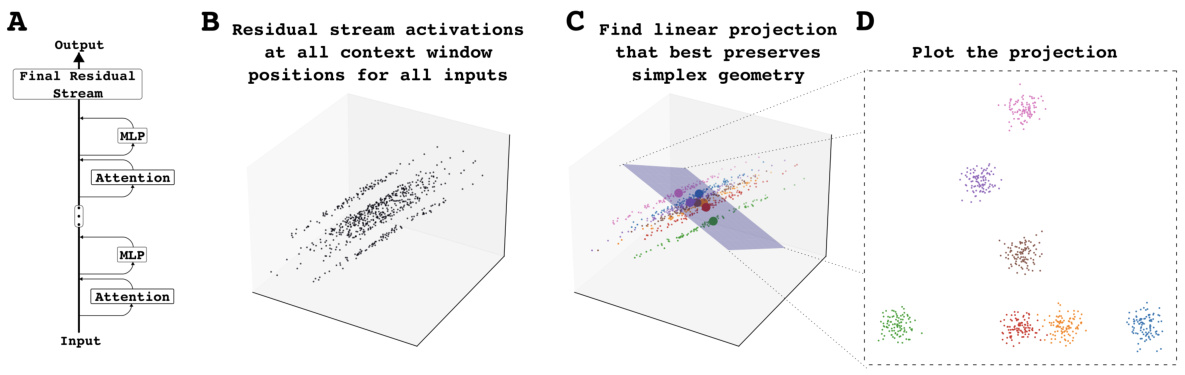

This figure illustrates the methodology for finding belief state geometry in the residual stream of a transformer. Panel A shows the transformer architecture focusing on the residual stream. Panel B shows the high-dimensional space of residual stream activations, which are then colored according to their corresponding ground-truth belief states (Panel C). Finally, linear regression is used to find a lower-dimensional subspace that best preserves the simplex geometry of the belief states (Panel D).

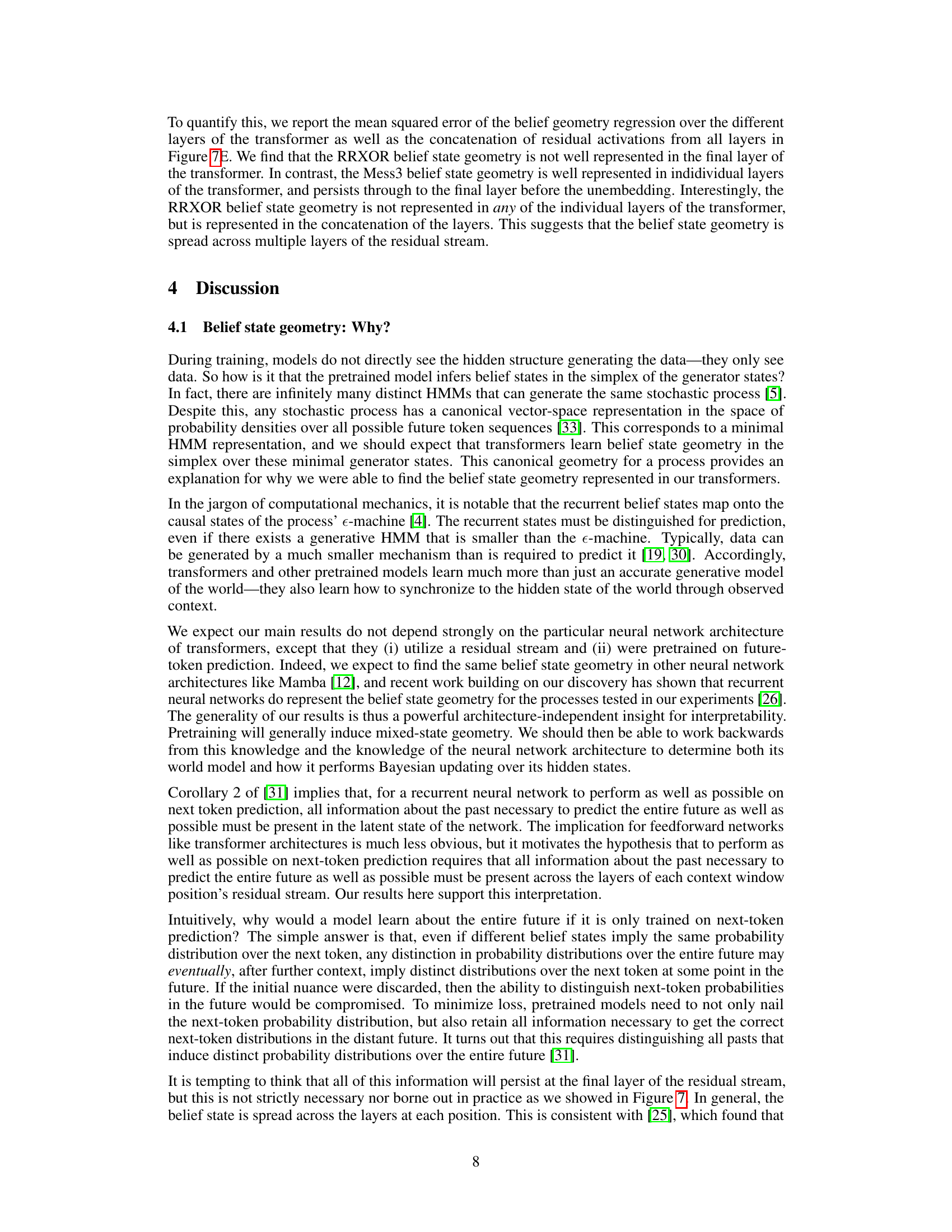

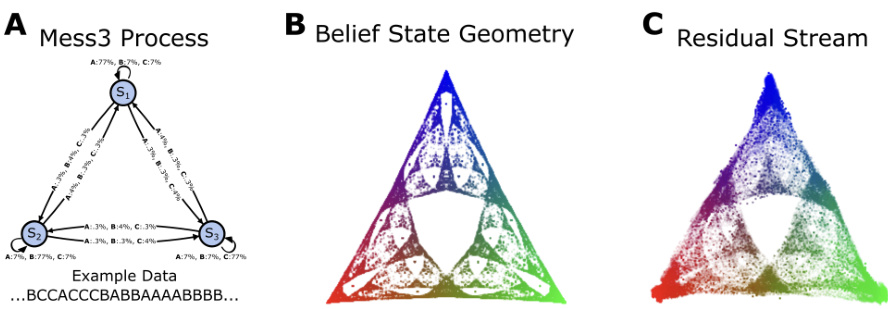

This figure demonstrates the main experimental result of the paper. It shows that the fractal geometry of optimal beliefs (predicted by the theory) is linearly embedded within the residual stream of transformers. Panel (A) describes the data-generating process (Mess3 process), panel (B) illustrates the resulting belief state geometry (a fractal pattern in the probability simplex), and panel (C) shows that a linear projection of the transformer’s residual stream activations successfully captures this fractal geometry.

This figure demonstrates the robustness and non-triviality of the findings showing the emergence of belief state geometry in the residual stream of transformers. Panel (A) shows the progressive emergence of the geometry during training. Panel (B) shows that the results hold up under cross-validation. Panel (C) controls for the possibility that the observed fractal geometry is a trivial consequence of dimensionality reduction by shuffling the belief state labels, showing that the fractal structure is indeed related to the underlying belief state geometry. Panel (D) quantifies the goodness of fit of the linear regression model used to project the residual stream activations onto the belief state simplex, demonstrating low mean squared error, especially when compared to the shuffled condition.

This figure shows that when the belief states have the same next-token prediction, the belief state geometry is represented across multiple layers instead of only the final layer. The Random-Random-XOR process is used as an example, visualizing its belief state geometry in a 4-simplex and demonstrating that the transformer linearly represents this geometry when considering the activations from all layers concatenated.

This figure compares the belief state geometry representation using residual stream activations before and after the final LayerNorm. It shows that the representation is qualitatively similar in both cases, with slightly lower error after LayerNorm, demonstrating the robustness of the findings to this preprocessing step.

This figure shows four subplots that demonstrate the robustness and non-triviality of the results in the paper. (A) shows that the fractal structure emerges during training, (B) shows that the results hold up under cross-validation. (C) shows that shuffling the belief states destroys the fractal structure, showing that it’s not an artifact of the dimensionality reduction. Finally, (D) shows that the mean squared error between the predicted and true belief state positions decreases over the course of training.

Full paper#