↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Vision-language models (VLMs) have shown great potential in various visual tasks; however, adapting them to new concepts is challenging due to limited information about the new classes. Existing approaches often rely on post-training techniques or prompts, which might not always be practical or efficient. This creates a need for new adaptation frameworks that enable better generalization and efficiency.

This paper introduces AWT (Augment, Weight, then Transport), a novel adaptation framework that addresses these limitations. AWT leverages data augmentation to enrich inputs, dynamically weights inputs based on prediction confidence, and employs optimal transport to mine cross-modal semantic correlations. Experimental results show that AWT consistently outperforms state-of-the-art methods in zero-shot and few-shot image classification, zero-shot video action recognition, and out-of-distribution generalization, demonstrating its effectiveness and adaptability across different VLMs, architectures, and scales. AWT provides a simple yet effective strategy for enhancing the adaptability of VLMs without additional training or prompts.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel framework for adapting vision-language models to new concepts without extensive retraining, addressing a critical limitation in current approaches. This could significantly impact various downstream applications and open new avenues for research in zero-shot and few-shot learning.

Visual Insights#

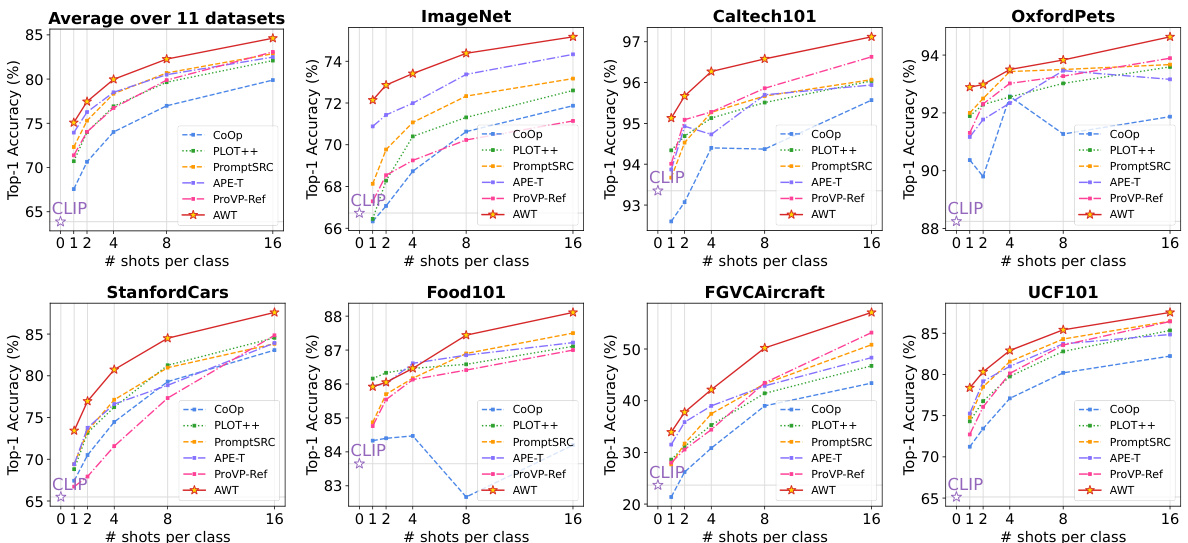

This figure illustrates three different approaches for adapting Vision-Language Models (VLMs) to new tasks and compares their performance. (a) shows the standard approach that calculates distances between raw image and text embeddings. (b) depicts a prompt-based method enriching inputs with additional task-specific information in the form of visual or textual prompts. (c) illustrates the augment-based AWT method enriching raw inputs with image transformations and more detailed class descriptions from language models. Finally, (d) shows a performance comparison of the AWT method with state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods across multiple tasks (zero-shot and few-shot image classification, out-of-distribution generalization, and zero-shot video action recognition).

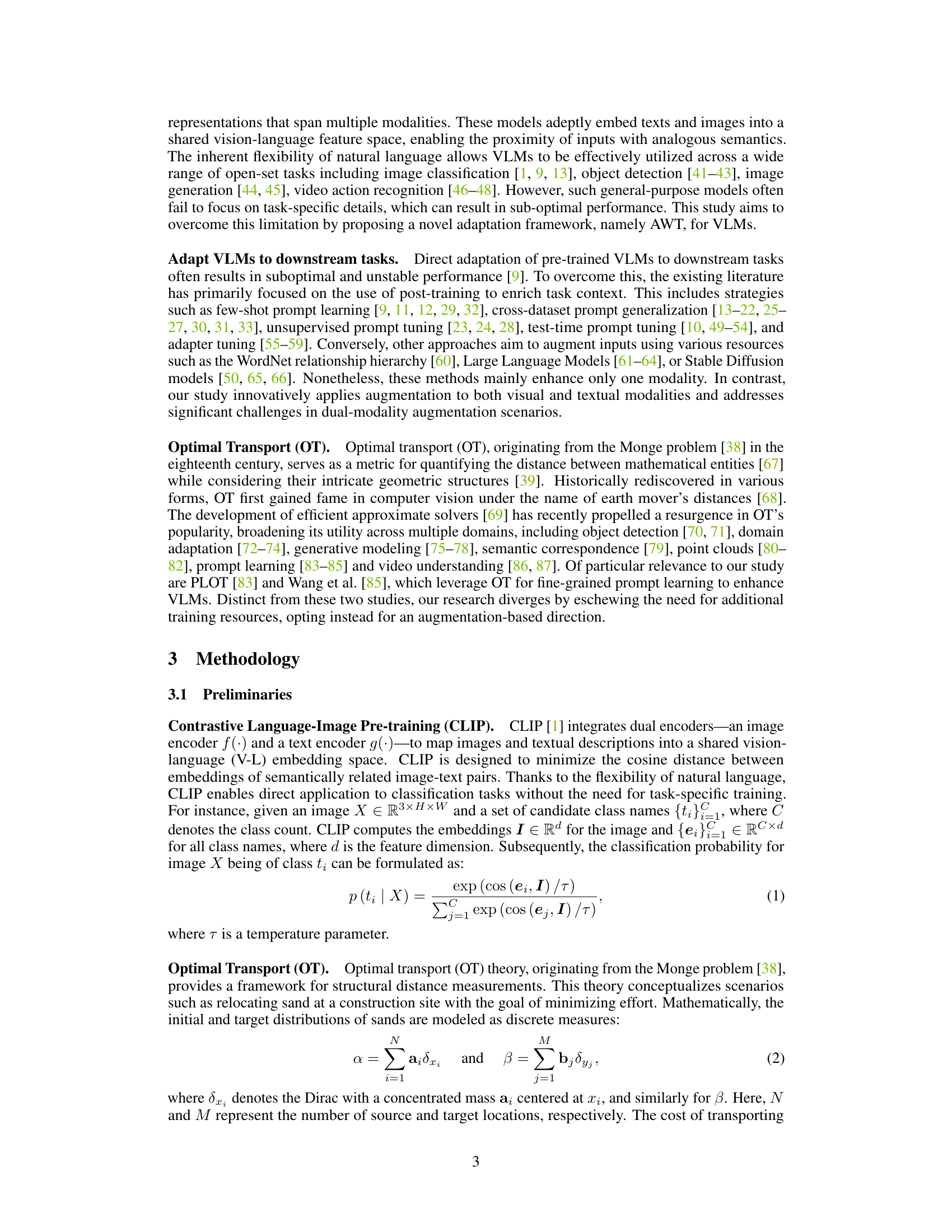

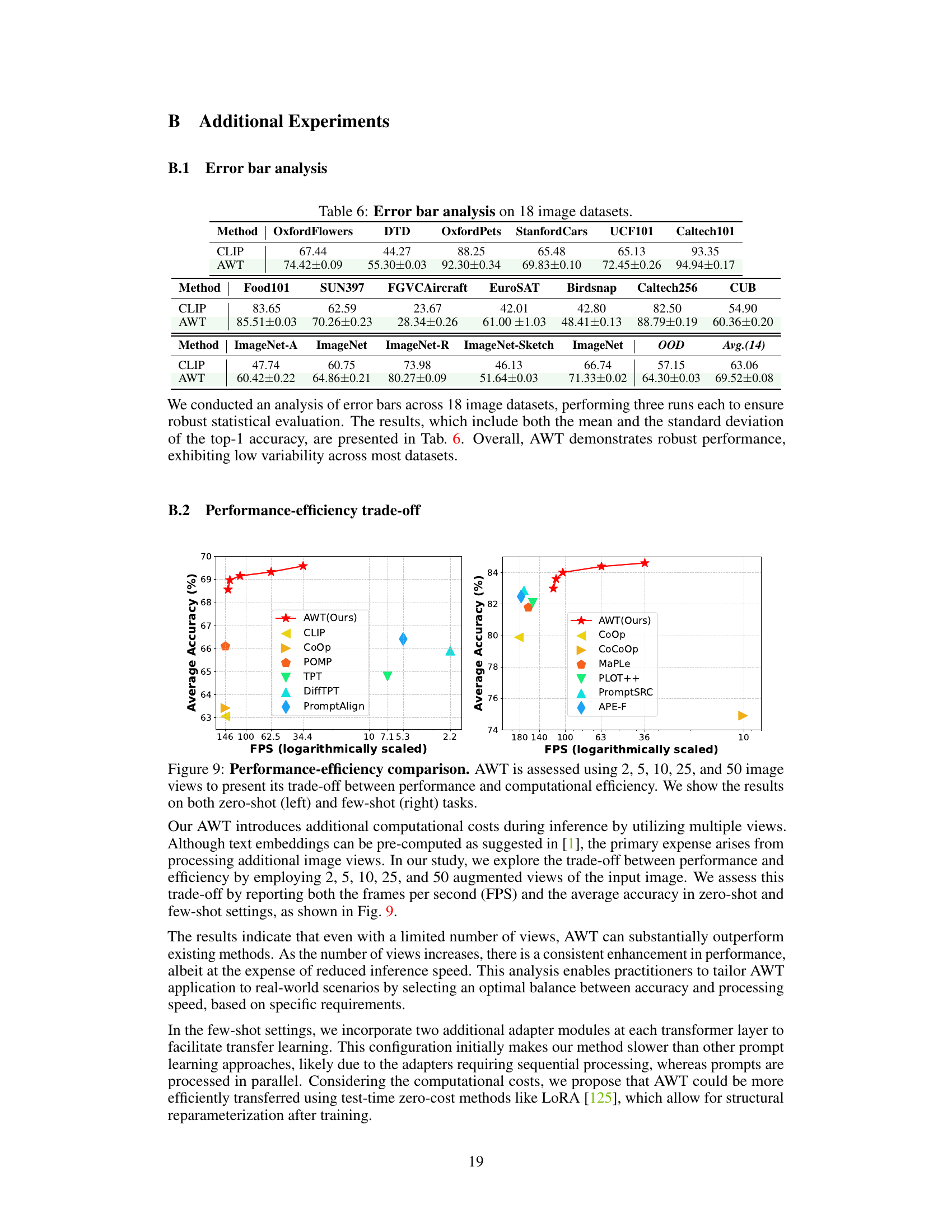

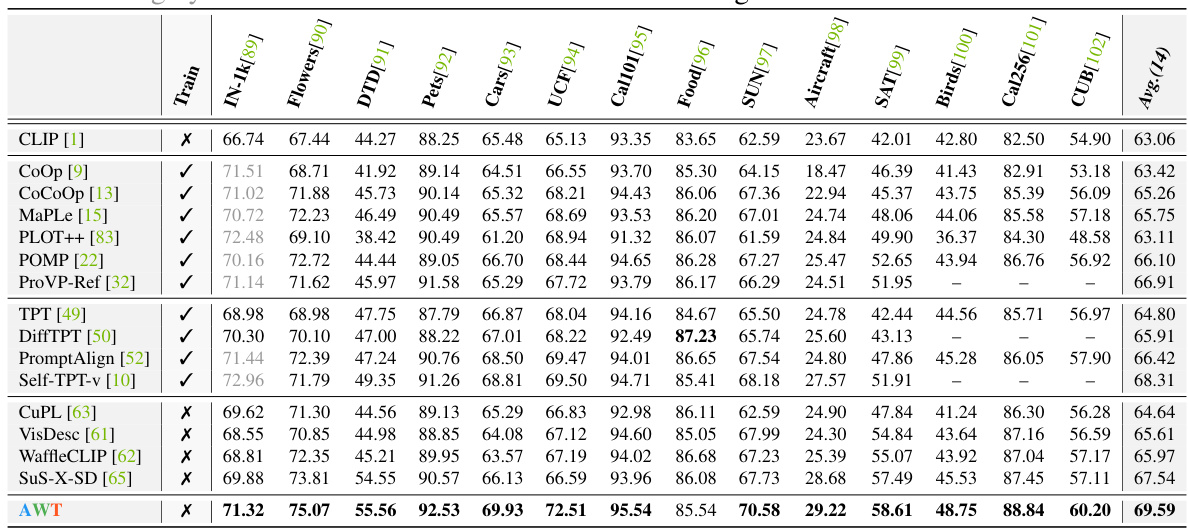

This table presents the results of zero-shot image classification experiments across 14 datasets. It compares the performance of AWT against several state-of-the-art methods. The top-1 accuracy is reported for each dataset, and the ‘Train’ column indicates whether each method required additional training (including test-time training). Methods trained on ImageNet are excluded from the zero-shot results and indicated in grey.

In-depth insights#

AWT Framework#

The AWT framework, designed for adapting Vision-Language Models (VLMs) to new concepts, cleverly combines three crucial stages: augmentation, weighting, and optimal transport. Augmentation diversifies both visual and textual inputs using image transformations and Large Language Models (LLMs), creating richer representations. The weighting mechanism, based on prediction entropy, dynamically assigns importance scores to these augmented inputs, prioritizing reliable information. Finally, optimal transport elegantly mines the semantic correlations between the weighted image and text views, resulting in a more robust and contextually relevant distance metric for classification. This three-step process allows AWT to seamlessly enhance various VLMs’ zero-shot and few-shot capabilities without needing any additional training, making it a highly effective and adaptable framework for improving VLM performance in diverse tasks.

Multimodal Augmentation#

Multimodal augmentation, in the context of vision-language models, represents a powerful technique to enhance model performance by enriching both the visual and textual inputs. Instead of relying solely on raw images and class labels, multimodal augmentation incorporates diverse visual perspectives through transformations like cropping, flipping, and color jittering. Simultaneously, it augments textual information using language models to generate richer descriptions that go beyond simple class names. This dual approach addresses the limitations of traditional methods, where models might focus on irrelevant image details or lack sufficient contextual information about the classes. By creating a more comprehensive and nuanced input representation, multimodal augmentation helps the model better capture the semantic relationship between images and text, leading to improved zero-shot and few-shot learning capabilities. The effectiveness of this approach depends on carefully selecting augmentation strategies and language models appropriate for the task and dataset. Careful consideration of the balance between diversity and relevance in augmentations is crucial for optimal performance. The successful implementation of multimodal augmentation showcases its potential to unlock the full power of vision-language models and improve their generalization to new and unseen data.

Optimal Transport#

Optimal transport (OT), a mathematical framework for measuring distances between probability distributions, plays a crucial role in the paper. OT is leveraged to quantify the semantic correlations between augmented image and text views, moving beyond simple distance calculations in embedding space. This approach allows the model to dynamically weigh the importance of each view and prioritize relevant information. By framing the problem as an OT problem, the model efficiently discovers cross-modal correlations, leading to improved performance in various zero-shot and few-shot scenarios. The use of OT represents a novel and innovative approach to multi-modal adaptation that surpasses conventional averaging methods. The paper highlights OT’s capability to capture complex structural relationships between modalities, which simple distance metrics fail to achieve. This sophisticated technique enhances the model’s ability to adapt to new concepts and situations, demonstrating the power of OT in vision-language tasks.

Ablation Experiments#

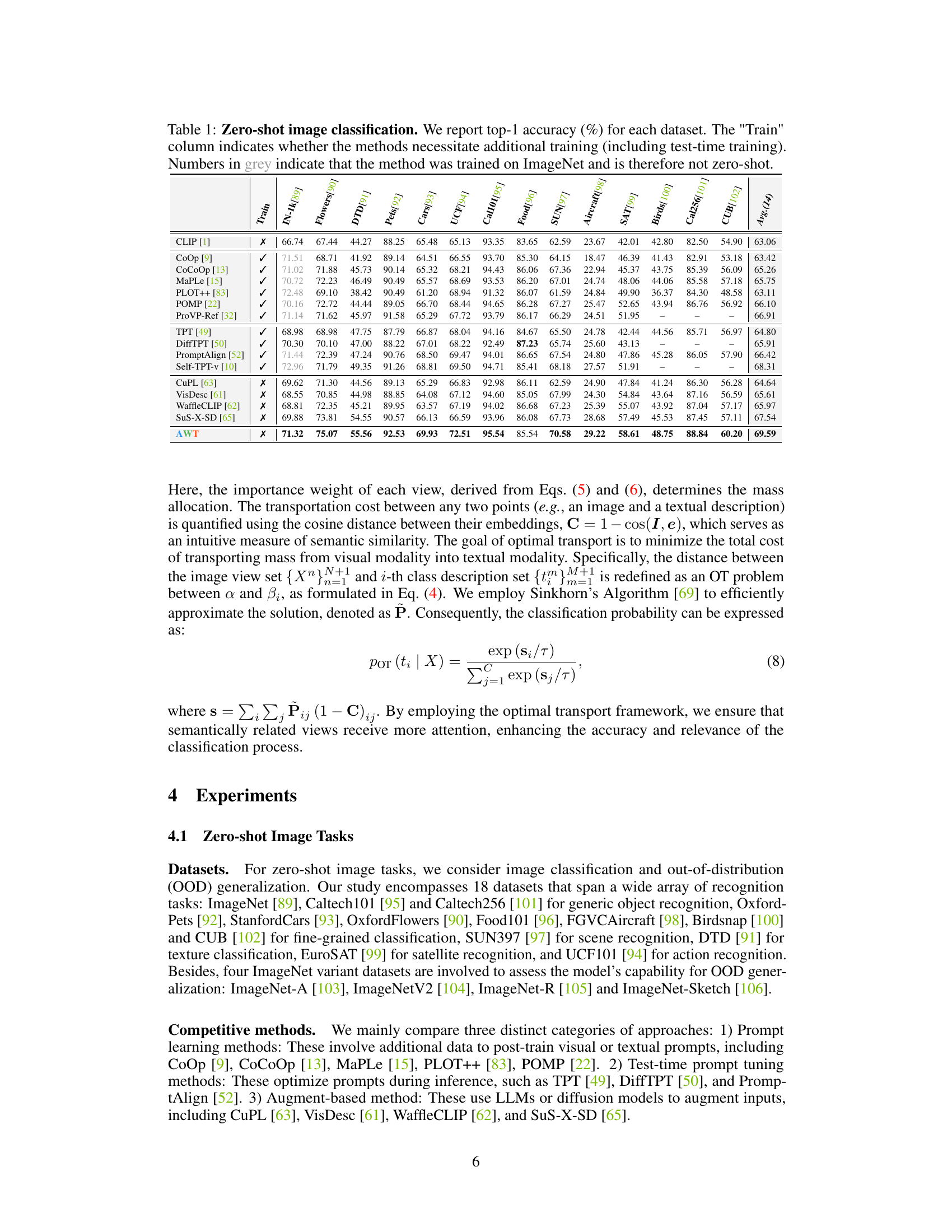

Ablation experiments systematically remove components of a model to determine their individual contribution. In vision-language model adaptation, this could involve disabling augmentation techniques (e.g., image transformations, prompt variations), the weighting mechanism, or the optimal transport component. Analyzing the impact of each ablation on key metrics reveals the relative importance of each part. For instance, a significant drop in accuracy after removing augmentation suggests its crucial role in enhancing input diversity. Similarly, observing minimal change upon removing optimal transport might indicate that cross-modal correlations are less critical than the input data variations. The results of ablation experiments offer critical insights into the design choices and the interplay between different model aspects, helping researchers understand the model’s strengths and weaknesses and guide future improvements. The effectiveness of AWT depends on the combined contributions of all three components, not just one in isolation. Therefore, ablation studies are necessary to quantify the individual impact and guide future development.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could involve investigating methods to reduce redundancy among augmented views, potentially employing techniques like feature selection or clustering to enhance efficiency. Another promising avenue is exploring the application of AWT to other vision-language tasks such as video understanding, semantic segmentation, and action detection, requiring adaptation of the framework to handle temporal data or fine-grained visual distinctions. Exploring different LLM prompting strategies to generate more diverse and informative descriptions, and assessing the influence of different architectural choices on AWT’s performance are further areas for investigation. Finally, a thorough examination of AWT’s limitations in handling low-resolution images and potential solutions using advanced image augmentation techniques like diffusion models warrants further research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

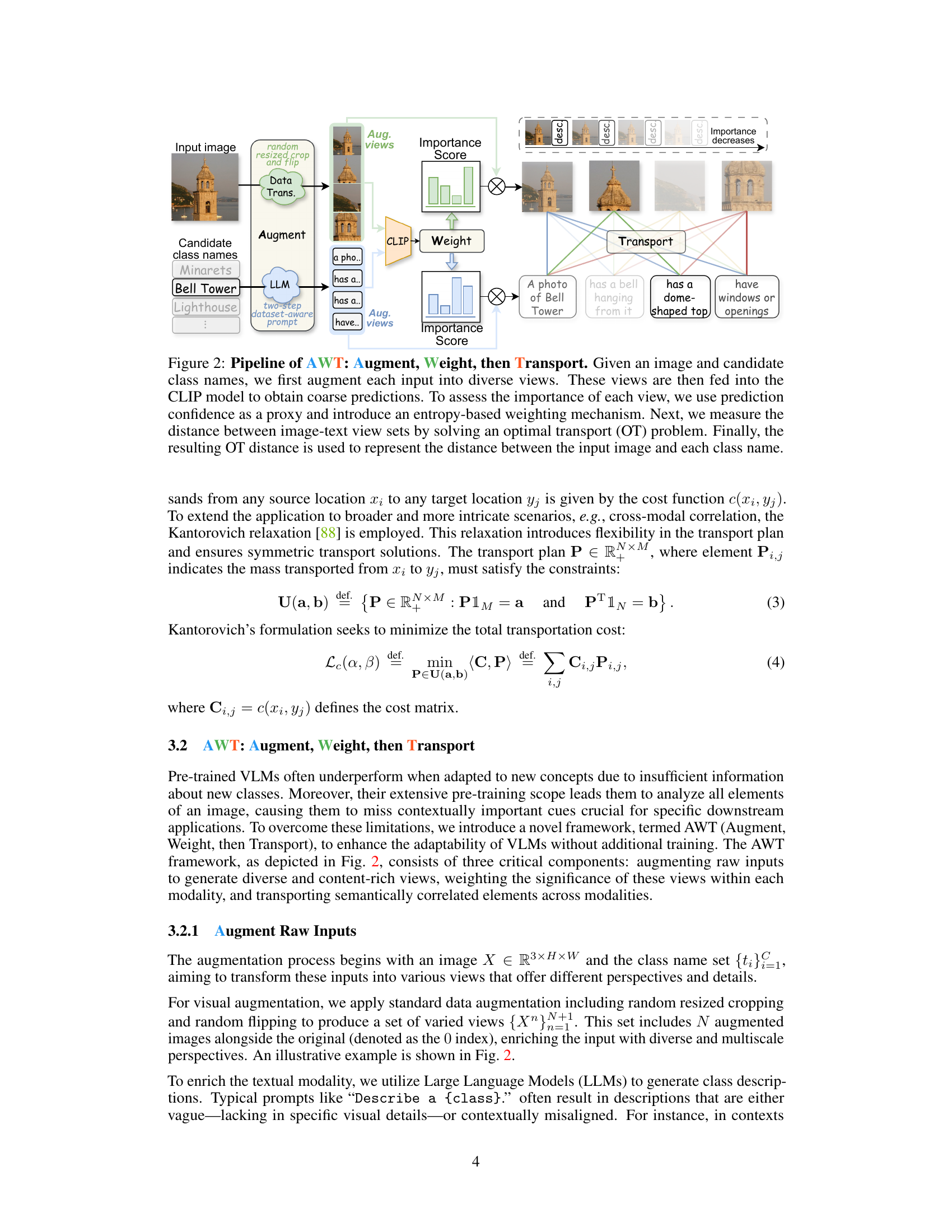

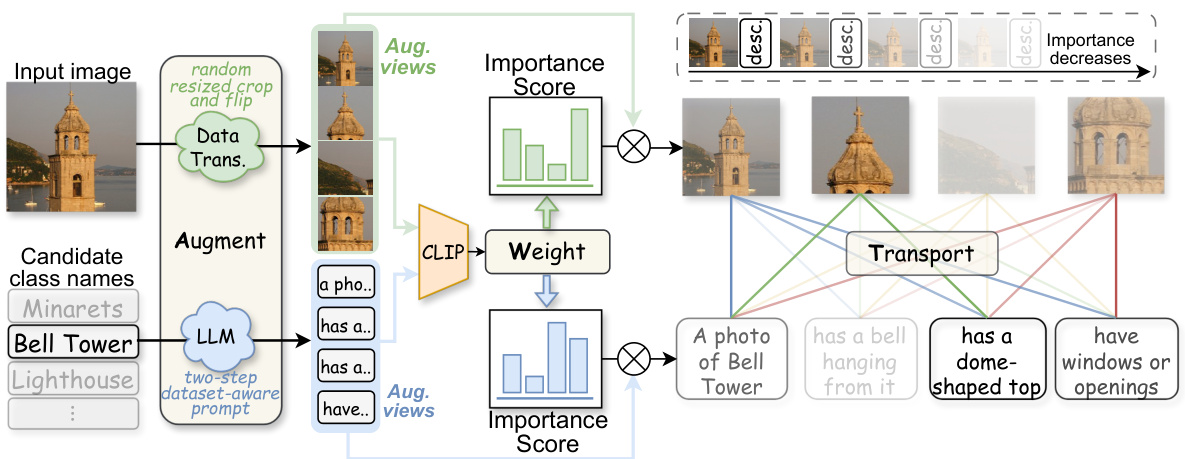

This figure illustrates the AWT framework’s pipeline. It starts with an input image and candidate class names, which are augmented into multiple diverse views using image transformations and LLM-generated descriptions. These augmented views are fed into CLIP to generate initial predictions, and their importance is scored based on prediction confidence. Optimal Transport then calculates the distance between image and text view sets, ultimately determining the distance between the input image and each class name.

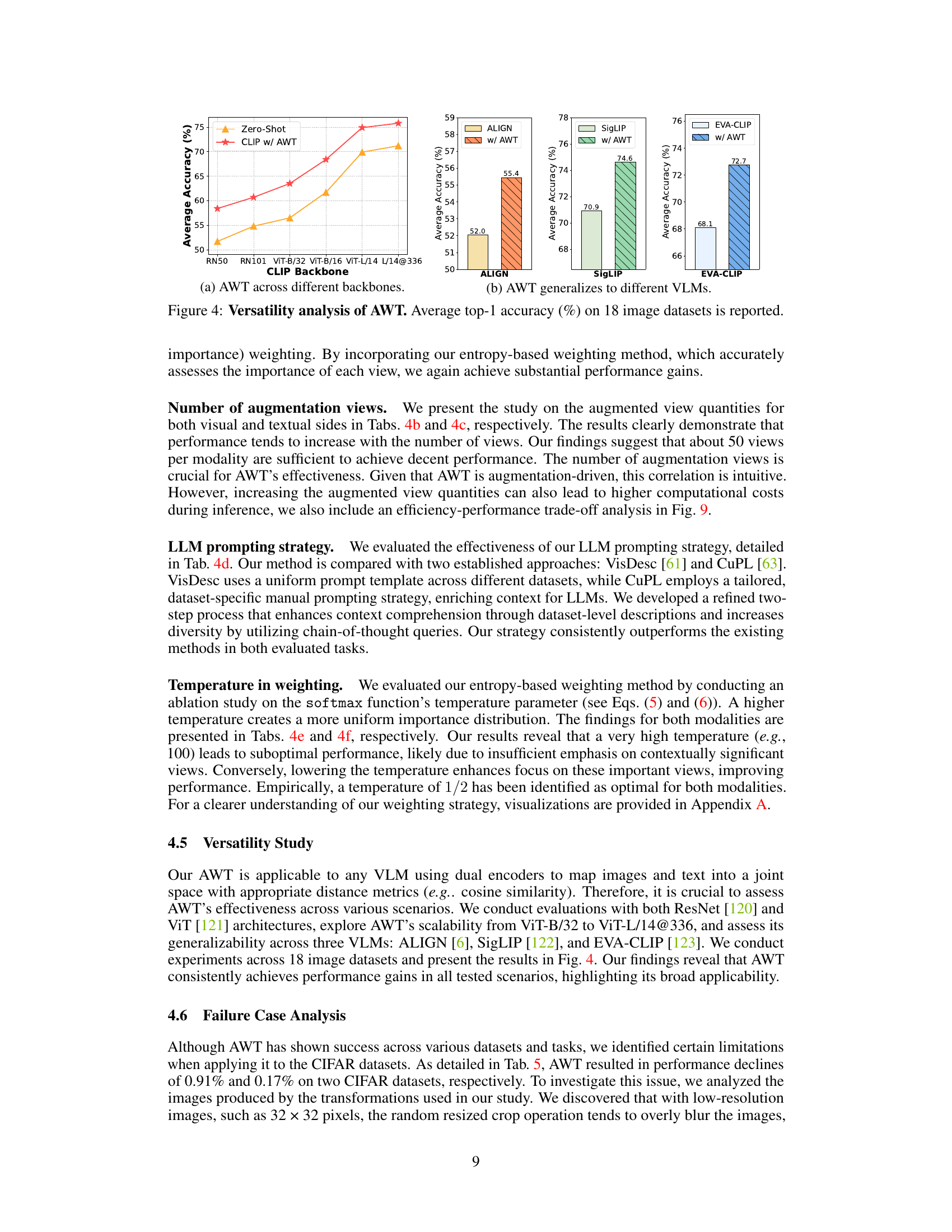

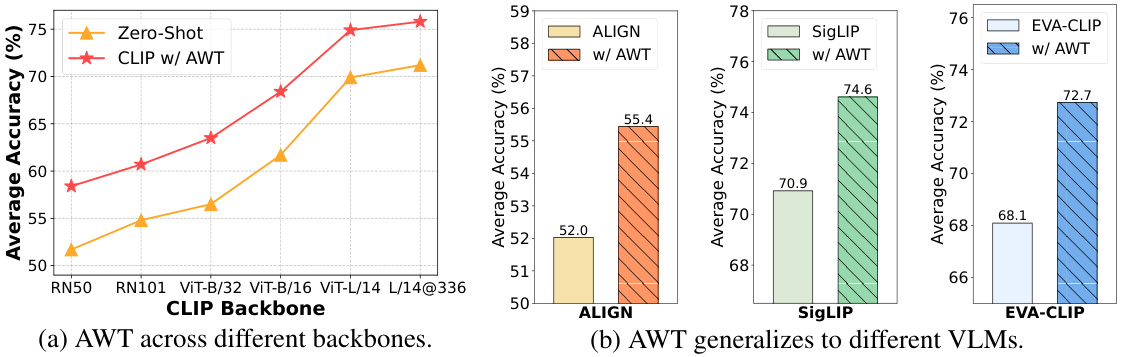

This figure demonstrates the versatility and generalizability of the AWT framework across different vision-language model (VLM) backbones and architectures. Subfigure (a) shows AWT’s performance using different CLIP backbones, from lightweight models (RN50, RN101) to more powerful transformer-based models (ViT-B/32, ViT-B/16, ViT-L/14, L/14@336). Subfigures (b) and (c) show AWT’s adaptability to various VLMs (ALIGN, SigLIP, and EVA-CLIP), highlighting its consistent improvement over baseline performance.

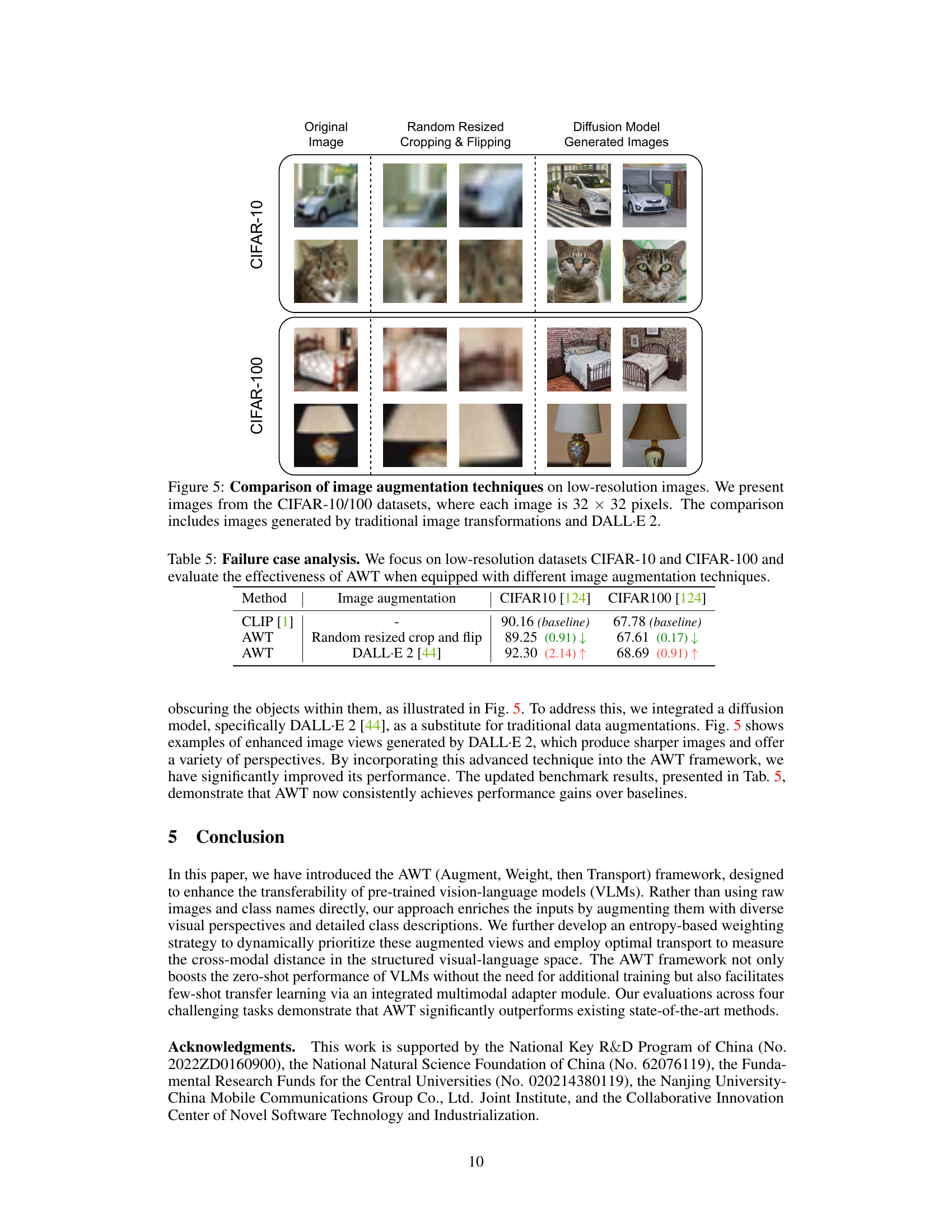

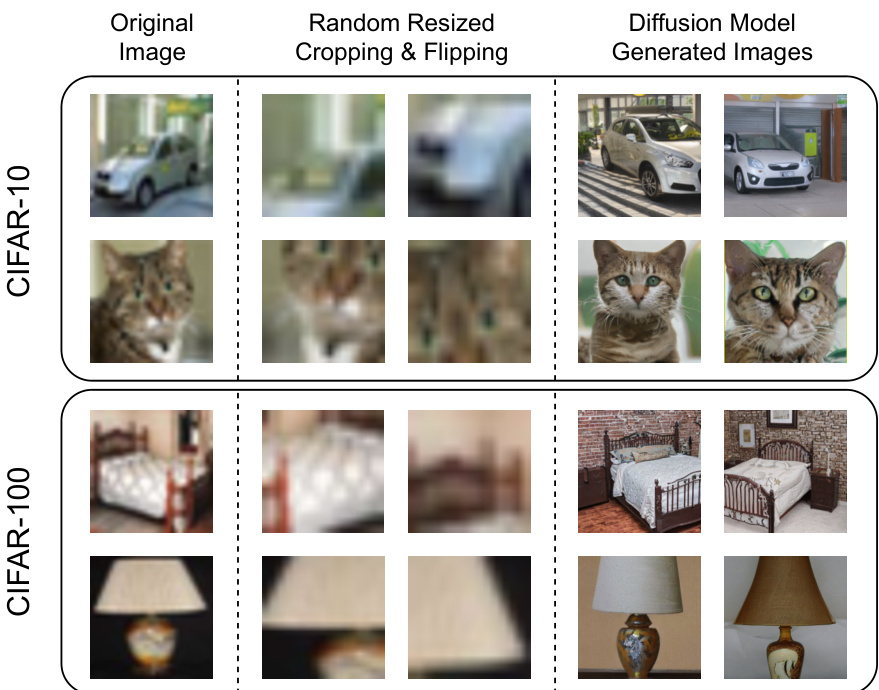

This figure compares three different image augmentation techniques on low-resolution images from the CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The original images are shown alongside versions augmented using random resized cropping and flipping, and versions generated using the DALL-E 2 diffusion model. The purpose is to illustrate the impact of different augmentation strategies on low-resolution images and how these different augmentation methods deal with the low resolution issue.

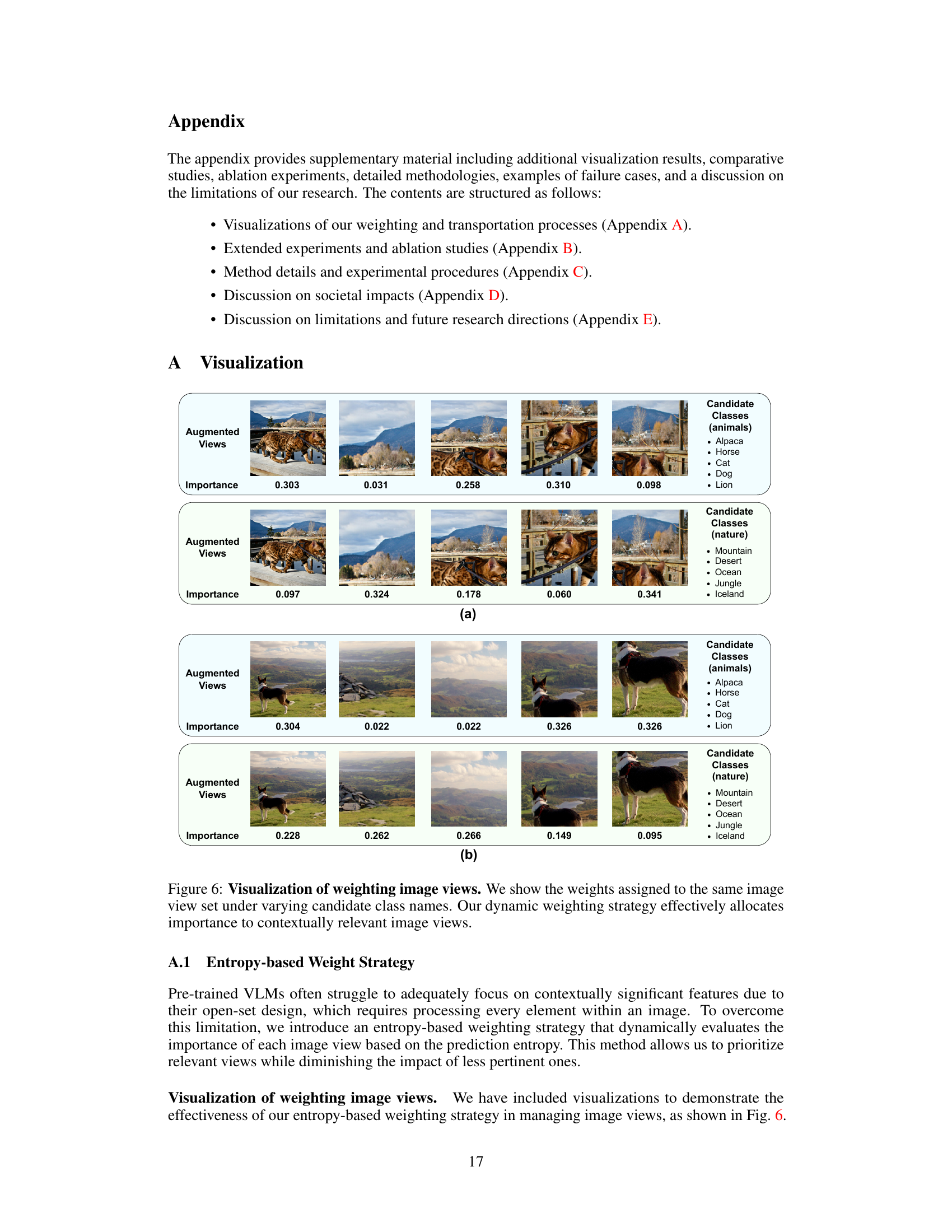

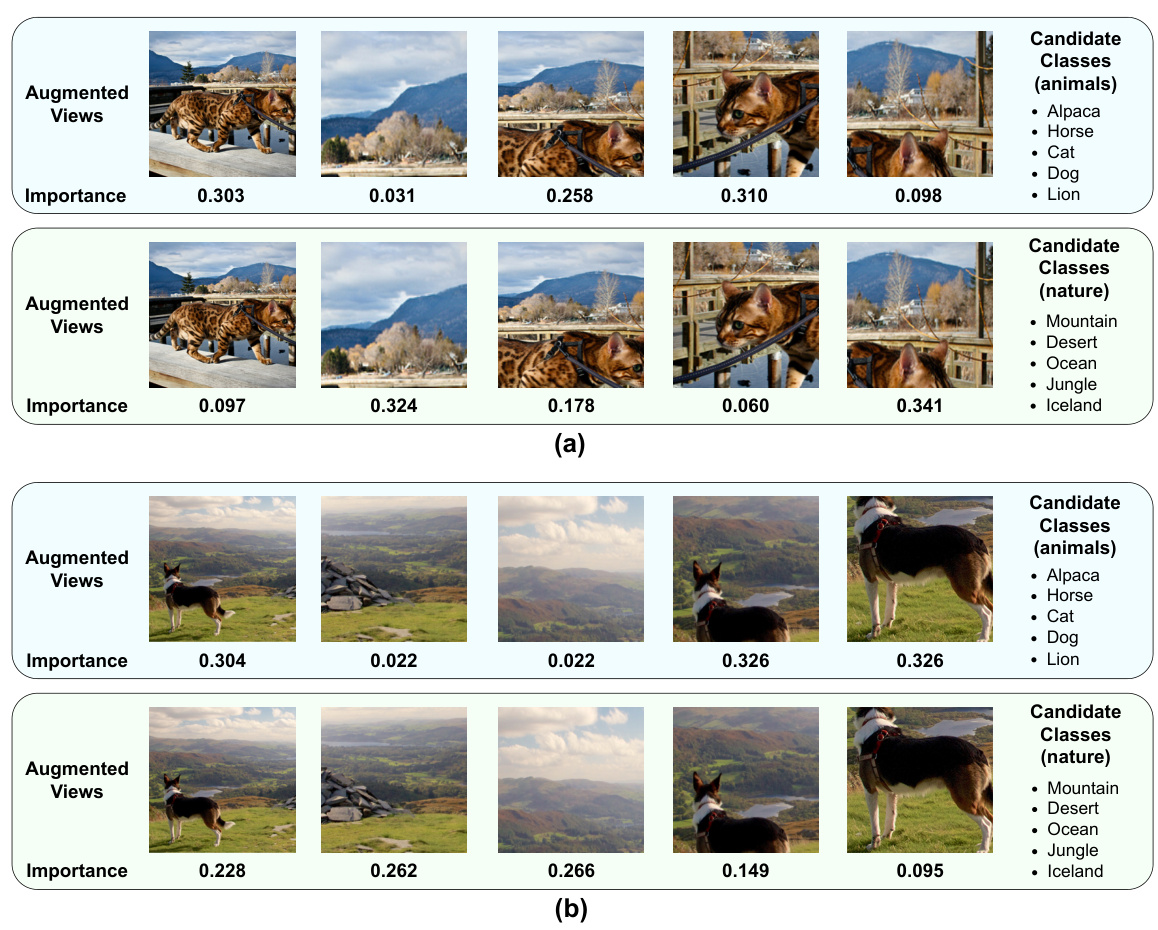

This figure visualizes the results of the entropy-based weighting strategy used in the AWT framework. It shows how the importance weights assigned to different image augmentations of the same image vary depending on the candidate class names. The weights are dynamically assigned, prioritizing views that are contextually relevant to the predicted class.

This figure visualizes the weights assigned to image views using the entropy-based weighting mechanism. It demonstrates how the weights change depending on the candidate class names. The results highlight how the model prioritizes image views that are relevant to the class being considered, effectively allocating importance to contextually significant features.

This figure visualizes the cross-modal correlations discovered by the optimal transport method used in AWT. After augmenting the input image and class names to generate diverse views, the optimal transport method identifies and quantifies the correlations between these views. The heatmap shows the strength of correlation between different image views (columns) and textual descriptions (rows). High values (darker blue) indicate stronger semantic relationships between the image and text modalities, demonstrating how AWT effectively captures cross-modal interactions.

This figure illustrates the three main approaches for adapting vision-language models (VLMs) to new tasks. (a) shows the standard approach where distances between image and class embeddings are directly calculated. (b) demonstrates the prompt-based approach, which uses post-trained visual or textual information to enrich the input. (c) presents the augmentation-based method, similar to the proposed AWT method. (c) depicts the AWT approach where inputs are augmented by transformations and class descriptions, importance variations are considered, and semantic correlations are mined. (d) shows the performance of AWT compared to other state-of-the-art methods across various tasks.

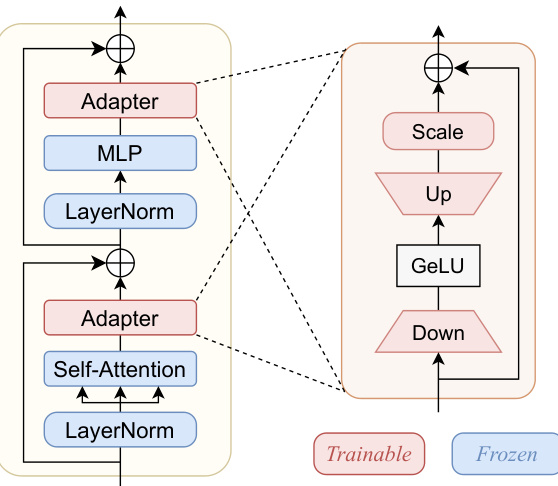

This figure shows the architecture of a multi-modal adapter module used in few-shot transfer learning. The adapter module is inserted after the multi-head self-attention and MLP module within each transformer layer. It consists of a down-projection layer, a GeLU activation layer, an up-projection layer, and a trainable scale parameter. The module is applied to both the image and text embeddings to reduce the number of parameters while maintaining performance. The figure highlights which components are trainable and which are frozen.

More on tables

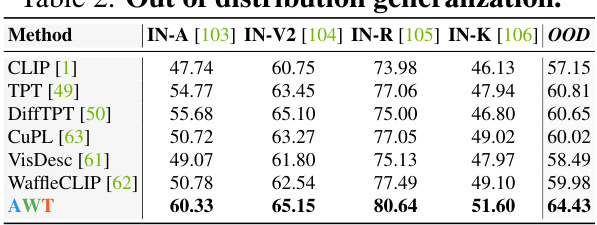

This table presents the results of out-of-distribution generalization experiments on four ImageNet variants (ImageNet-A, ImageNet-V2, ImageNet-R, ImageNet-Sketch). The performance of different methods (CLIP, TPT, DiffTPT, CuPL, VisDesc, WaffleCLIP, and AWT) is evaluated using top-1 accuracy. The OOD column represents the average performance across these four datasets, showing AWT’s superiority in handling out-of-distribution samples.

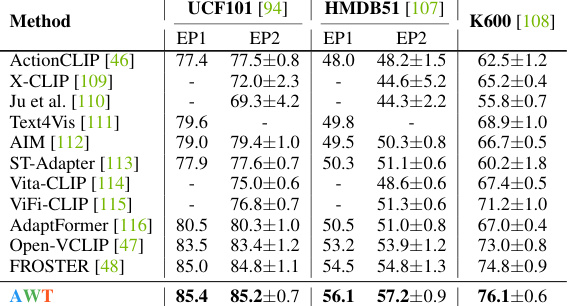

This table presents the results of zero-shot video action recognition on three benchmark datasets: UCF101, HMDB51, and Kinetics-600. Two evaluation protocols are used for UCF101 and HMDB51 (EP1 and EP2), while Kinetics-600 uses three validation sets. The table compares the performance of AWT against several state-of-the-art methods, highlighting AWT’s superior performance in this task.

This table presents the zero-shot image classification results on 14 datasets. It compares the performance of AWT against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods, including prompt-based, test-time prompt tuning, and other augmentation-based approaches. The ‘Train’ column indicates whether each method requires any additional training, highlighting AWT’s zero-shot capability. Numbers in gray indicate methods pre-trained on ImageNet, which are not considered zero-shot.

This table presents the zero-shot image classification results on 14 datasets using various methods. It compares AWT’s performance to other state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods, highlighting its ability to achieve high accuracy without requiring additional training. The ‘Train’ column indicates whether a method uses additional training data, differentiating zero-shot approaches from others. The table provides a comprehensive comparison of different methods across multiple datasets, offering a clear view of AWT’s effectiveness.

This table presents the results of experiments on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets using different image augmentation techniques. The baseline performance of CLIP is shown for comparison, along with results when applying AWT using the traditional random resized cropping and flipping technique, and again using AWT with DALL-E 2 generated images. The performance change (increase or decrease) relative to the baseline is indicated using arrows and numerical values.

This table presents the results of zero-shot image classification on 14 datasets using different methods. The top-1 accuracy is reported for each dataset and method. The ‘Train’ column indicates whether the method requires additional training, differentiating between zero-shot and non-zero-shot approaches. Numbers in gray indicate that the method was pre-trained on ImageNet, which is not considered a zero-shot scenario.

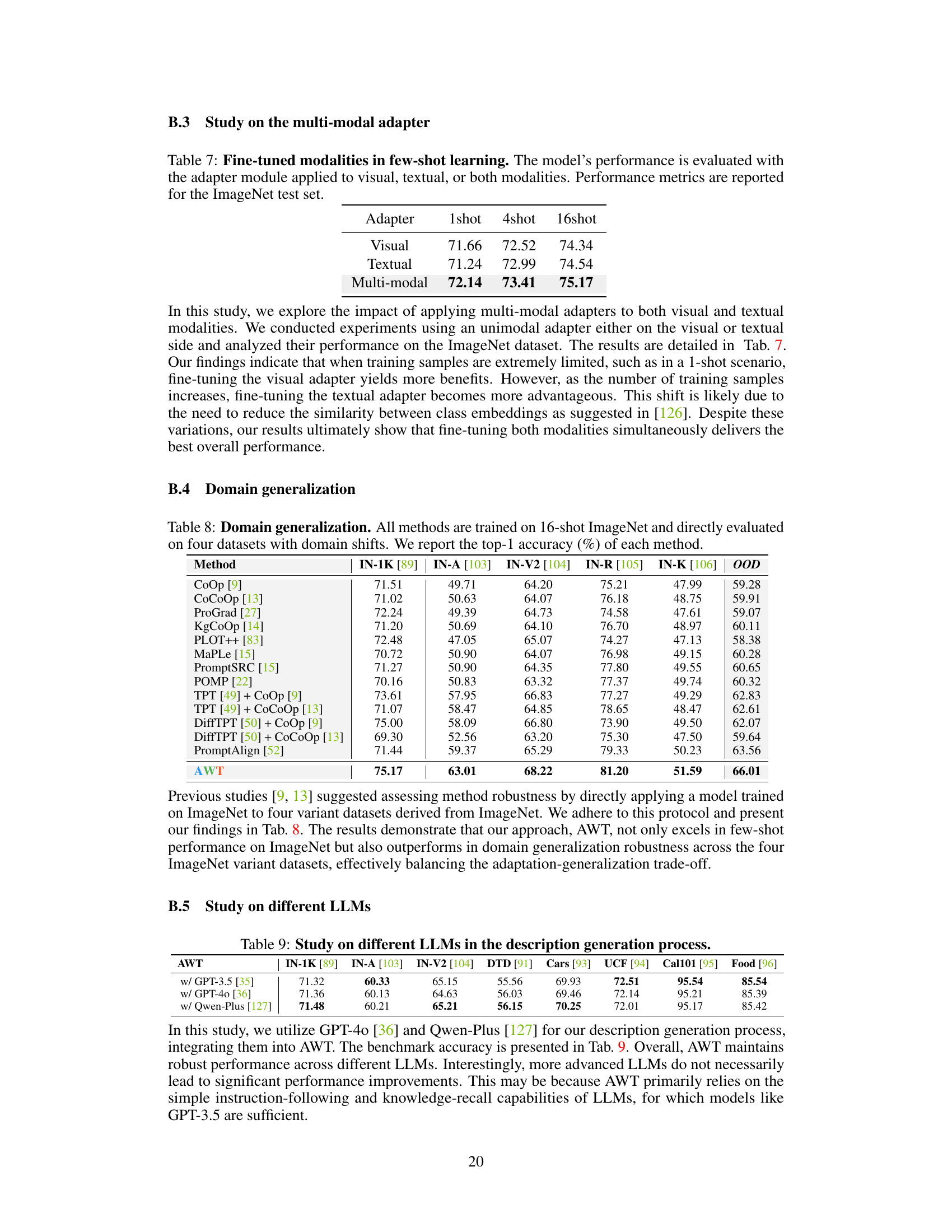

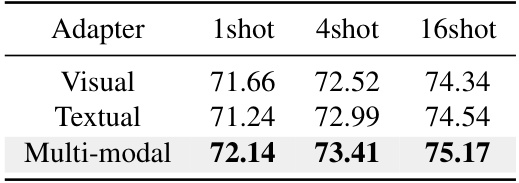

This table presents the results of a few-shot learning experiment on the ImageNet dataset using a multi-modal adapter. The adapter was applied to either the visual modality, the textual modality, or both. The table shows the top-1 accuracy for each configuration (1-shot, 4-shot, 16-shot), demonstrating that the multi-modal adapter consistently outperforms the single-modality adapters.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments. All the methods listed were trained on 16-shot ImageNet and then directly evaluated on four other datasets with different domain characteristics (ImageNet-A, ImageNet-V2, ImageNet-R, and ImageNet-Sketch). The results show the top-1 accuracy for each method on each dataset, providing a measure of how well each method generalizes to unseen data with different distributions.

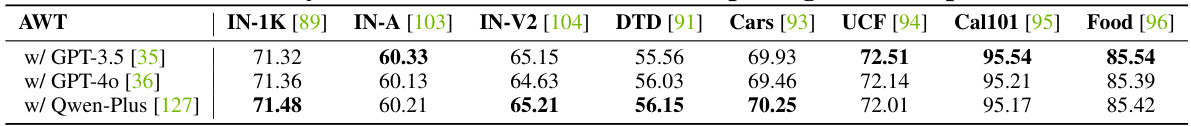

This table compares the performance of AWT when using different large language models (LLMs) for generating class descriptions. It shows the top-1 accuracy achieved on various image datasets (IN-1K, IN-A, IN-V2, DTD, Cars, UCF, Cal101, Food) for three different LLMs: GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and Qwen-Plus. The results demonstrate the robustness of AWT to different LLMs and highlight that the more advanced LLMs do not always yield better performance.

This table compares the performance of the AWT framework using different methods for generating class descriptions. The baseline AWT method uses a single global question to generate descriptions. Other methods utilize various prompting strategies, including using 3 global questions or 4.56 dataset-specific questions. The results are evaluated using out-of-distribution (OOD) average accuracy across 14 datasets. The table demonstrates that the proposed two-step dataset-aware prompting approach in AWT yields the best performance.

This table presents the zero-shot image classification results on 14 datasets using various methods. The top-1 accuracy is reported for each dataset and method. The ‘Train’ column indicates whether each method required additional training (including test-time training), highlighting the zero-shot capability of the methods. Numbers in gray indicate methods that were pre-trained on ImageNet, making them not truly zero-shot.

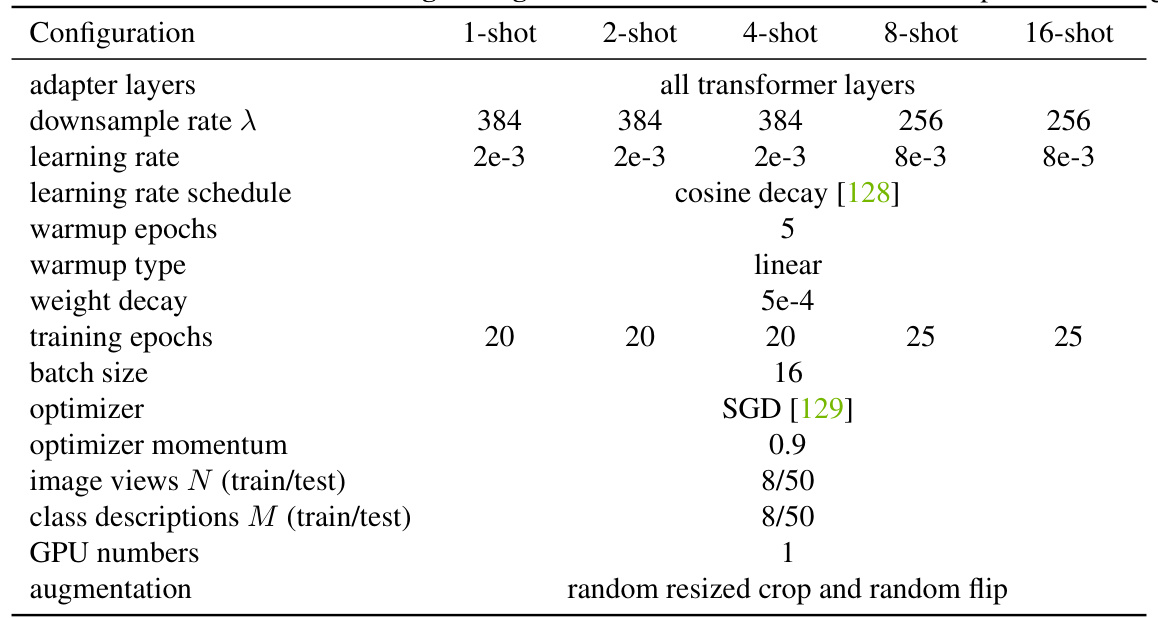

This table shows the hyperparameters used for few-shot transfer learning experiments with different numbers of shots (1, 2, 4, 8, and 16). It details settings for the adapter layers, downsample rate, learning rate, warmup epochs, weight decay, training epochs, batch size, optimizer, momentum, number of image views and class descriptions for training and testing, and GPU numbers used. The augmentation strategy is also specified.

This table presents the results of zero-shot image classification experiments on 14 datasets using various methods. The top-1 accuracy is reported for each dataset and each method. The ‘Train’ column indicates whether the method required any training, including test-time training. Methods trained on ImageNet are indicated in gray, as they are not considered zero-shot.

This table presents the zero-shot image classification results on 14 datasets. It compares the performance of AWT against several state-of-the-art methods. The accuracy is reported as top-1 accuracy (%). The ‘Train’ column indicates whether a method used any additional training data. Gray numbers represent methods that were trained on ImageNet, thus not considered zero-shot.

Full paper#