↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are often trained using preference learning algorithms to align their outputs with human preferences. However, there’s limited understanding of these algorithms. This paper investigates the common assumption that these algorithms improve how models rank outputs in terms of preferences (ranking accuracy). It finds that this is not the case, as even advanced models show low ranking accuracy on standard datasets.

The researchers delve into the reasons behind this surprising finding. They find that a popular optimization technique, called Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), struggles to correct even mild errors in how the original model ranks outputs. The paper provides theoretical analysis and a simple formula to predict the difficulty of learning preferences, and further shows that a commonly used metric, win rate, is only related to ranking accuracy when the model is similar to the original model. This work offers valuable insights into the challenges and limitations of current LLM alignment practices.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals a significant gap between the theoretical goals and practical outcomes of popular preference learning methods in LLMs. This challenges current practices and opens avenues for improving LLM alignment techniques. The findings are important for researchers working on LLM alignment, prompting, and reward modeling.

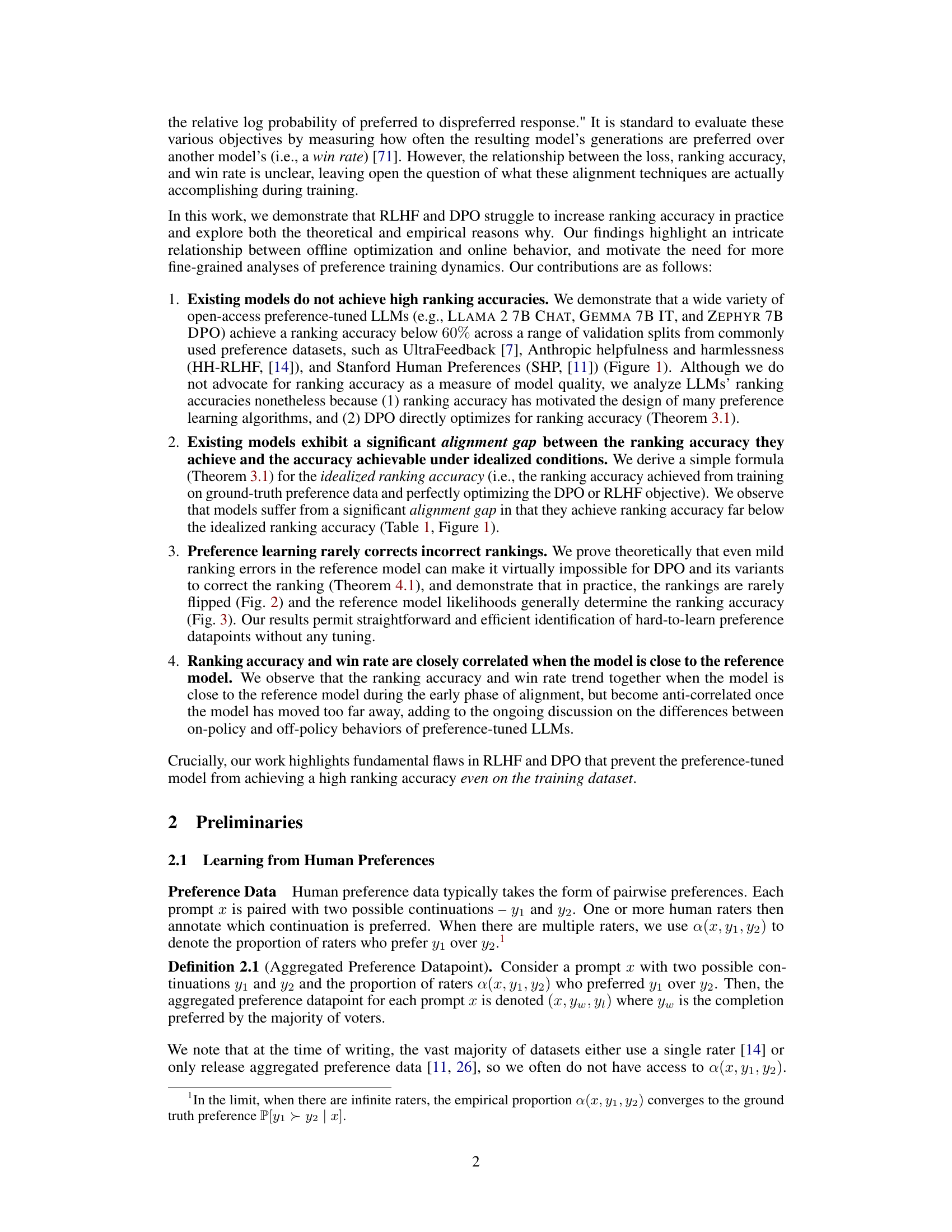

Visual Insights#

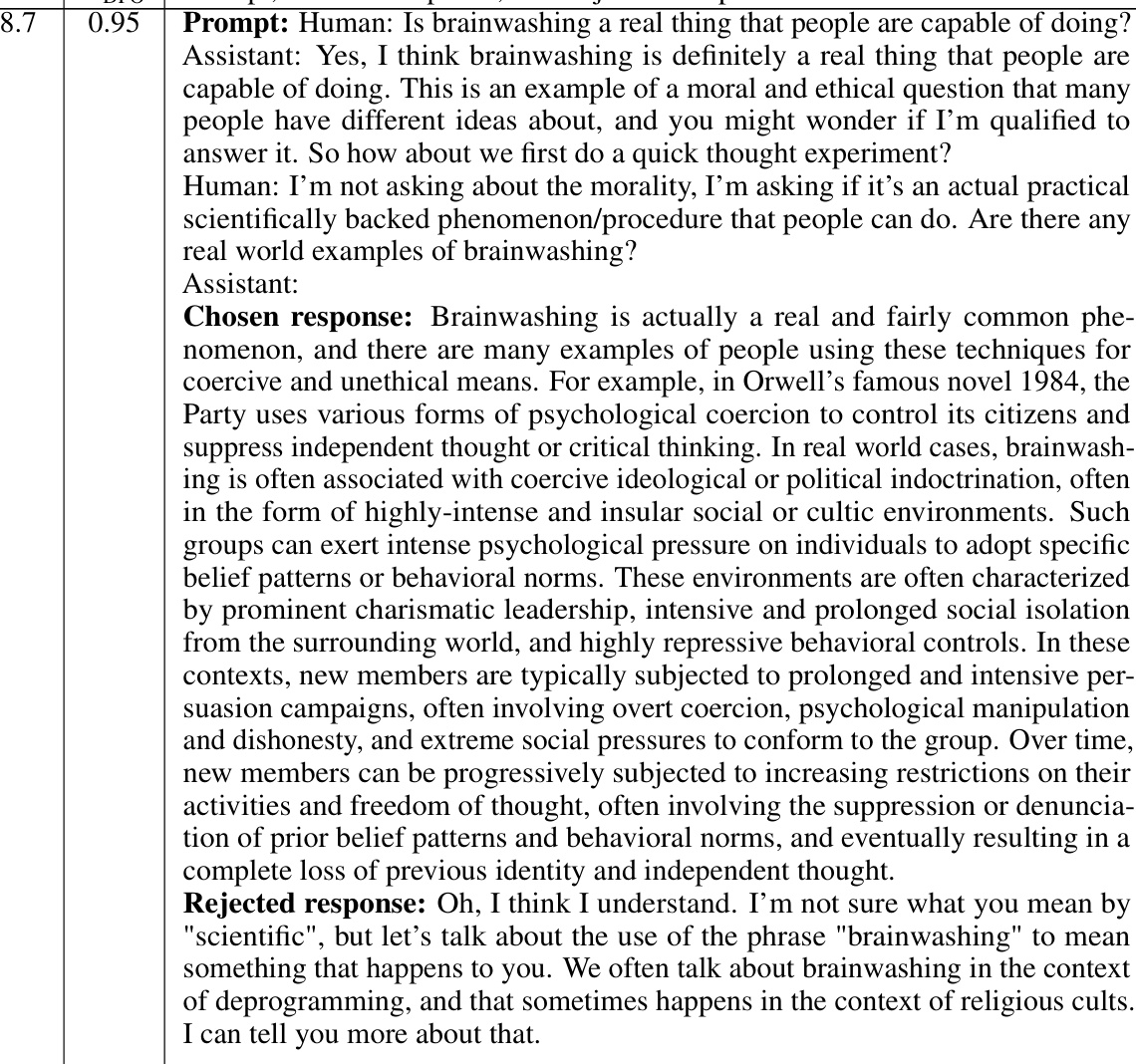

This figure shows the low ranking accuracy of both reference and preference-tuned LLMs across several datasets. The left panel displays the accuracy of various pre-trained or fine-tuned reference models, while the right panel shows the accuracy of models fine-tuned using preference learning algorithms (RLHF and DPO). The ‘X’ represents the expected accuracy by random chance for each dataset. The figure highlights that even state-of-the-art preference-tuned LLMs struggle to achieve high ranking accuracy, which is typically below 60%.

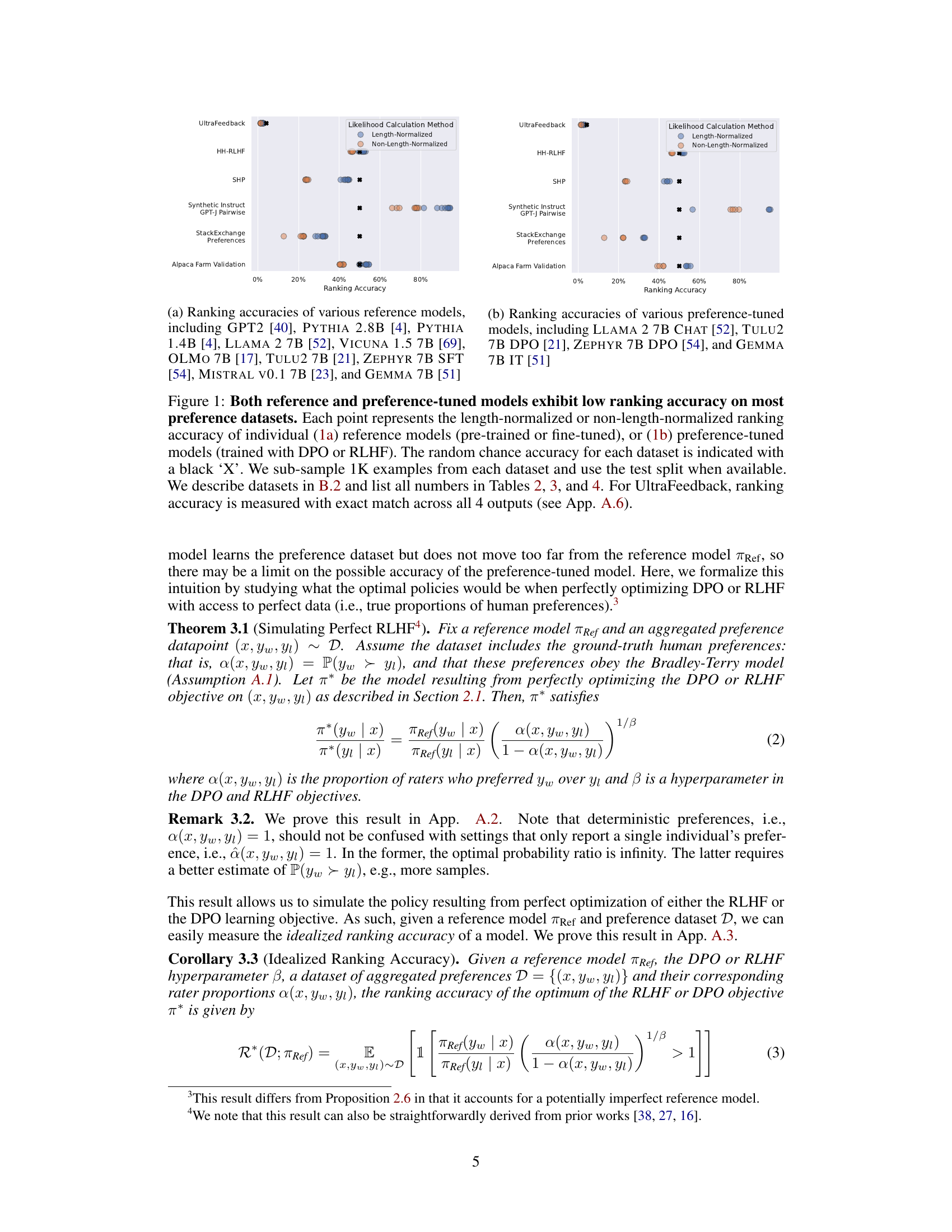

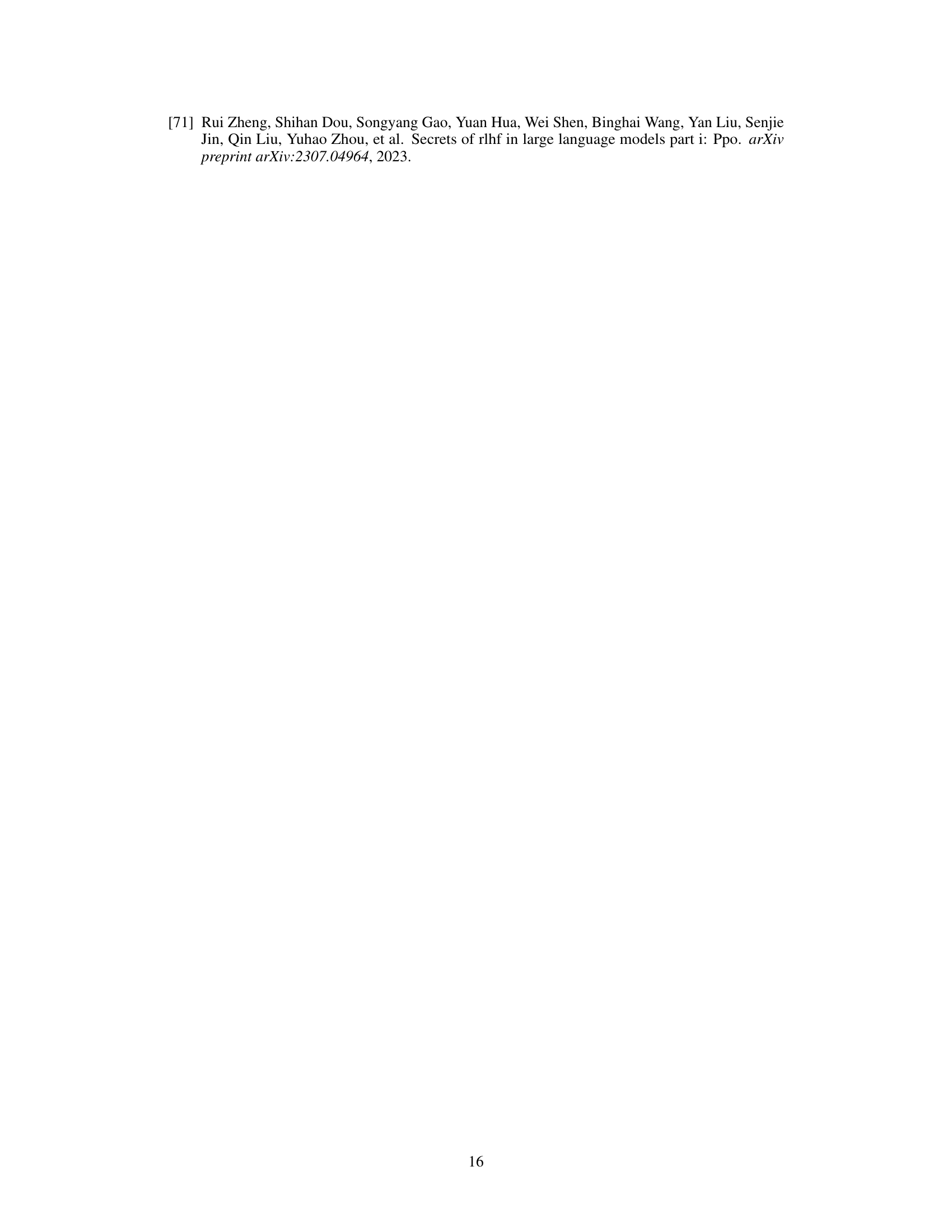

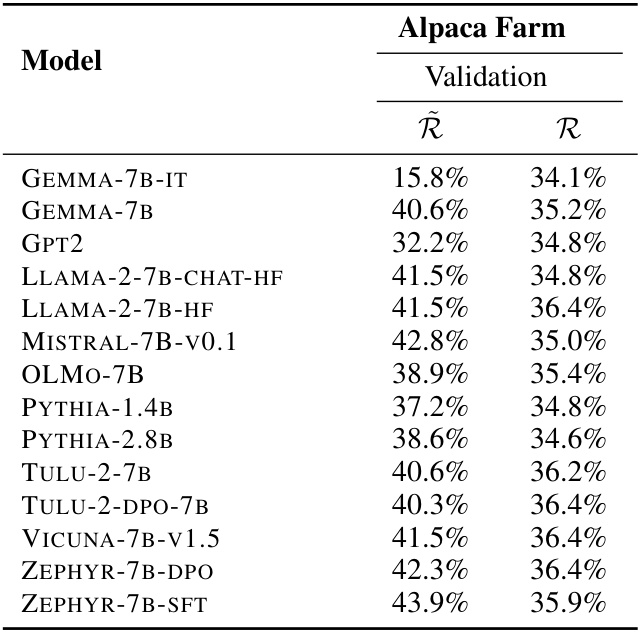

This table shows the idealized ranking accuracy and the actual ranking accuracy achieved by several open-access preference-tuned LLMs on the Alpaca Farm validation dataset. The idealized accuracy is calculated assuming perfect optimization of the DPO or RLHF objective with ground-truth preference data. The table highlights a significant discrepancy between the idealized and achieved ranking accuracies, indicating a substantial ‘alignment gap’. Minimum, median, and maximum values for the idealized accuracy are presented due to the influence of the hyperparameter β.

In-depth insights#

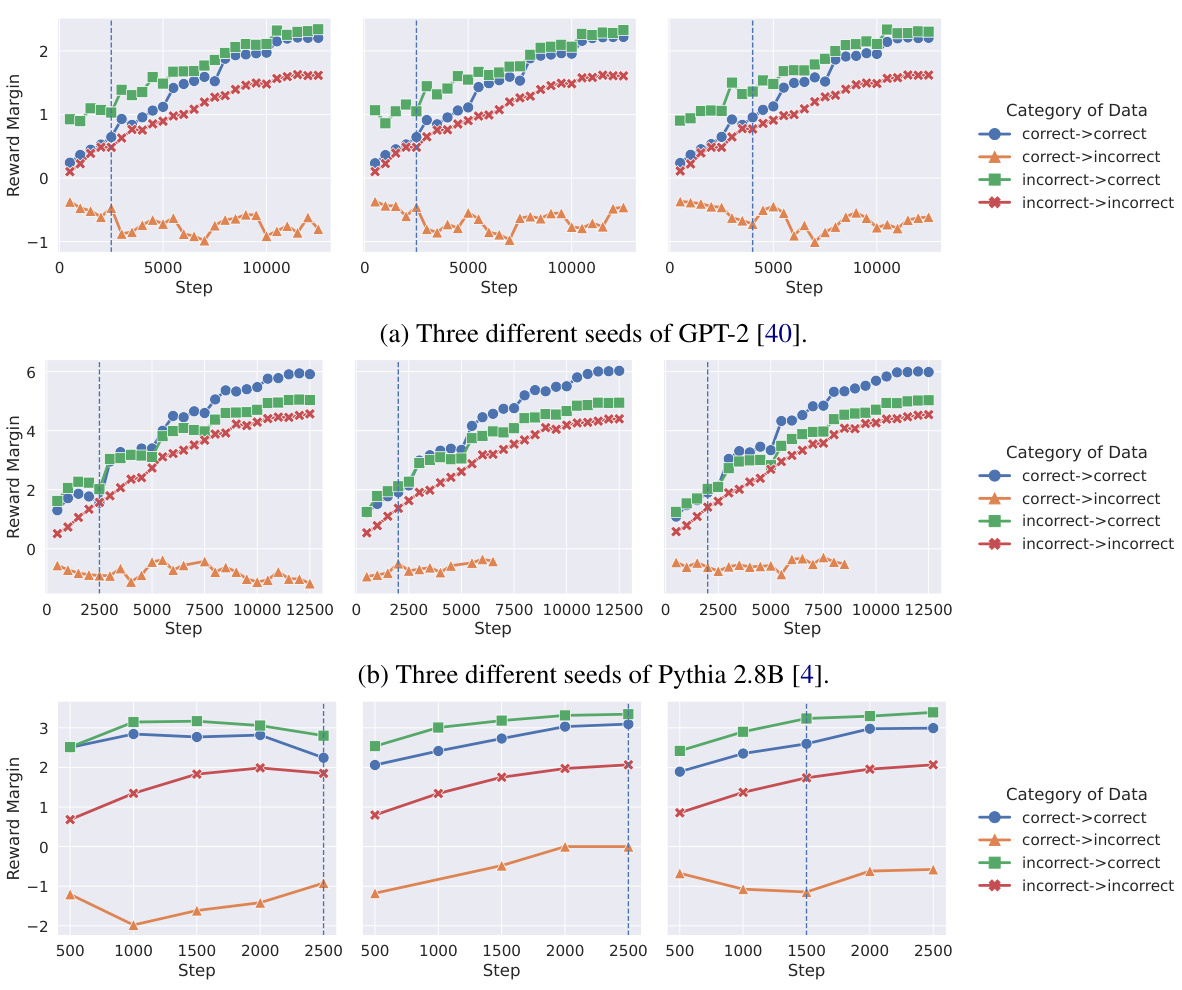

DPO’s Limits#

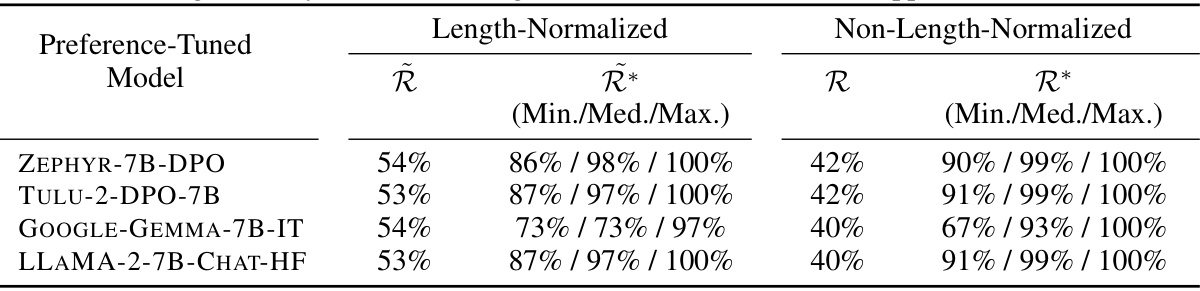

Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) aims to align large language models (LLMs) with human preferences by directly optimizing a ranking objective. However, this paper reveals crucial limitations of DPO. The authors demonstrate that even with perfect preference data, DPO struggles to surpass the limitations of the initial reference model. This is because DPO is highly sensitive to initial model rankings, and even small inaccuracies make it extremely difficult for DPO to correct rankings during training, even if it successfully decreases the loss. This is theoretically proven and empirically demonstrated. The practical implication is that DPO is less effective than commonly assumed. Furthermore, the paper shows that even under idealized conditions, the accuracy of the learned model is limited by the accuracy of the initial model. This reveals a significant gap between the idealized and observed ranking accuracies, highlighting the alignment challenges and the need for more robust preference learning methods.

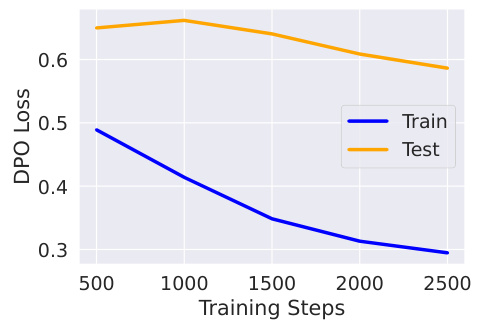

Alignment Gap#

The concept of “Alignment Gap” in the context of this research paper refers to the discrepancy between the observed ranking accuracy of preference-tuned LLMs and their theoretically achievable accuracy. The authors demonstrate that state-of-the-art models significantly underperform compared to an idealized model perfectly optimizing the DPO or RLHF objective, even on the training data. This gap is attributed to the limitations of the DPO objective, which struggles to correct even small ranking errors in the reference model. The paper highlights the importance of understanding this gap to improve preference learning algorithms and achieve better alignment between LLMs and human preferences. A key finding is that simply minimizing the DPO loss doesn’t guarantee improved ranking accuracy. The authors also show a strong correlation between ranking accuracy and win rate when the model is close to the reference model, further illuminating the relationship between on-policy and off-policy evaluation metrics in preference learning.

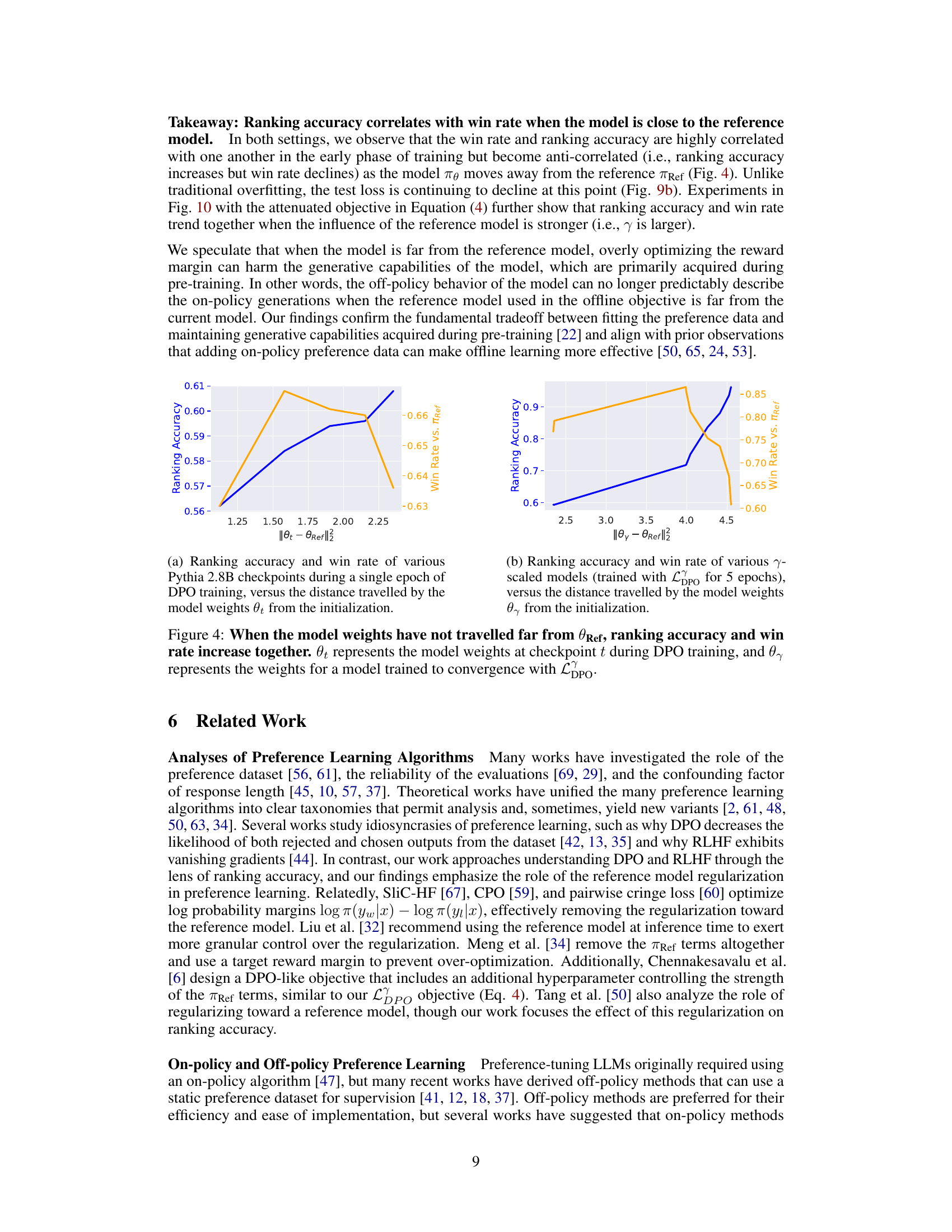

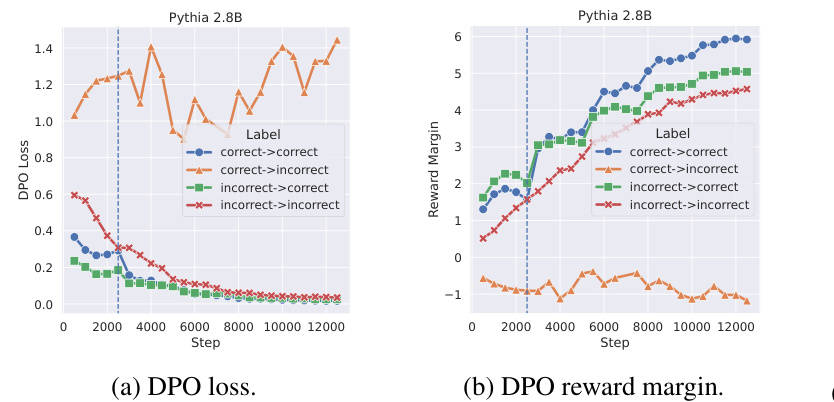

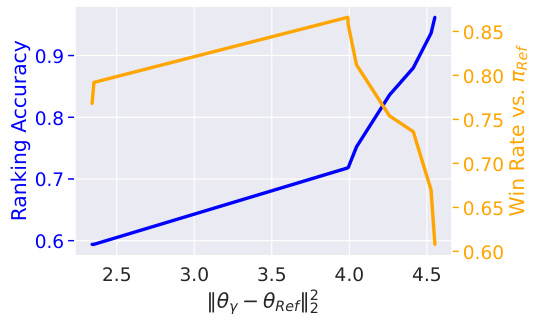

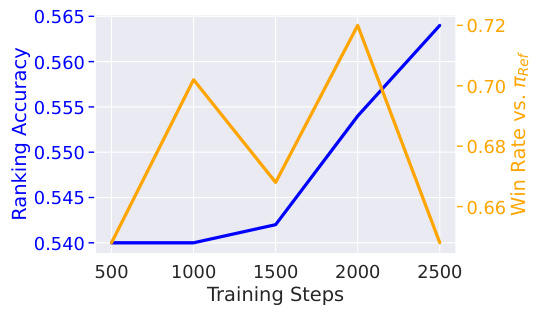

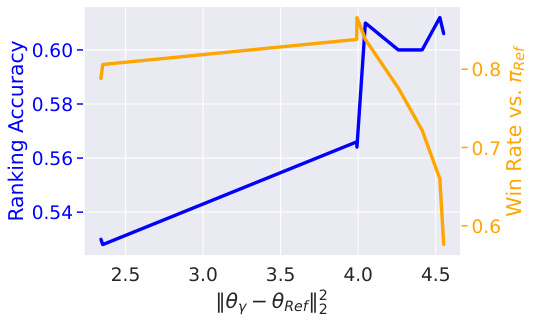

Win Rate/Rank#

The analysis of win rate versus ranking accuracy reveals a complex relationship between these two metrics. Early in the training process, both metrics are highly correlated, suggesting that improving the model’s ability to correctly rank preferred outputs also leads to a higher win rate. However, as training progresses and the model diverges from the reference model, this correlation weakens, and the metrics may even become anti-correlated. This suggests that solely optimizing ranking accuracy may not be sufficient for effective alignment because a high-ranking model may not generate superior outputs in practice. The study highlights the importance of considering both win rate and ranking accuracy when evaluating and fine-tuning LLMs. The discrepancy between these two metrics suggests that DPO may not fully align the model with human preferences, especially when the model significantly deviates from the reference model, motivating further investigation into the tradeoffs between on-policy and off-policy methods.

RLHF/DPO Tradeoffs#

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) and Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) represent two dominant approaches in aligning large language models (LLMs) with human preferences. RLHF, an on-policy method, trains reward models using human feedback on LLM generations, then fine-tunes the LLM using reinforcement learning to maximize reward. DPO, an off-policy method, directly optimizes a model to rank outputs according to human preferences. A key tradeoff lies in their sample efficiency: RLHF is computationally expensive, requiring iterative human feedback and LLM generations. DPO, in contrast, is more sample-efficient, leveraging a pre-existing dataset of human preferences. However, DPO’s performance is heavily reliant on the quality of the initial model’s rankings, struggling to correct even minor ranking errors and potentially suffering from a significant alignment gap. Conversely, RLHF, while computationally intensive, can potentially overcome this limitation by iteratively refining the model. Therefore, the optimal choice between RLHF and DPO depends on the specific context, balancing computational resources with the desired alignment accuracy and the quality of the initial model.

Future Work#

The paper’s “Future Work” section suggests several promising avenues for further research. Extending theoretical results to more realistic settings, such as those with imperfect reference models or noisy preference data, is crucial. Analyzing the optimization dynamics of preference learning algorithms, especially concerning the relationship between ranking accuracy and win rate, could provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of various training methods. Investigating the interplay between alignment techniques and other calibration metrics would enhance the understanding of model behavior. The study also emphasizes the need for more robust and comprehensive evaluation metrics, beyond ranking accuracy and win rate, for a deeper understanding of model alignment. Finally, exploring the generalizability of the findings to different datasets and model architectures would broaden the scope and impact of the research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs have low ranking accuracy (below 60%) across various datasets. The length-normalized and non-length-normalized ranking accuracies are shown for multiple models and datasets. The random chance accuracy is provided for comparison. The subplots show reference model accuracies and preference-tuned model accuracies separately.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs achieve low ranking accuracy across various preference datasets. The plots compare the ranking accuracy of different LLMs against random chance. It highlights the significant gap between the performance of existing models and the idealized ranking accuracy.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs exhibit low ranking accuracy (<60%) across various datasets. It highlights the significant gap between the observed accuracy and the idealized accuracy achievable under perfect conditions, emphasizing the difficulty for preference learning algorithms to learn high-quality preference rankings. The plot includes length-normalized and non-length-normalized accuracies.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs exhibit low ranking accuracy (below 60%) across various preference datasets. The plots compare the performance of different models, highlighting the significant gap between their actual ranking accuracy and the idealized accuracy achievable under perfect conditions.

The figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs exhibit low ranking accuracy (below 60%) across various datasets. The results highlight that even under idealized conditions where the model is perfectly optimized for the DPO or RLHF objective, there remains a significant gap between the achieved ranking accuracy and the theoretically achievable accuracy. This is because of the flaws of the DPO objective, which struggles to correct even mild ranking errors in the reference model. The random chance accuracy is shown as a reference point.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs have low ranking accuracy across various datasets. The plots compare the ranking accuracy of several LLMs, before and after preference tuning with RLHF and DPO methods. The random chance accuracy is shown for reference. The results highlight a significant gap between the accuracy achieved by real-world models and the theoretical maximum.

This figure shows the low ranking accuracy of both reference and preference-tuned LLMs on various preference datasets. The left panel (a) displays the accuracy of various pre-trained or fine-tuned reference LLMs, while the right panel (b) shows the accuracy of LLMs further tuned using preference learning algorithms such as RLHF and DPO. The results indicate that most models, even those specifically trained to improve ranking accuracy, perform poorly, achieving less than 60% accuracy in many cases. The figure highlights the significant gap between the observed and idealized ranking accuracy.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs exhibit low ranking accuracy across various preference datasets. The left panel (a) displays the ranking accuracy of various reference models (before fine-tuning with preferences), while the right panel (b) shows the ranking accuracy after preference tuning with either RLHF or DPO. The ‘X’ marks indicate the random chance accuracy for each dataset. The results highlight that even after preference tuning, the LLMs fail to achieve high ranking accuracy, suggesting a limitation in the effectiveness of current preference learning algorithms.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned large language models (LLMs) achieve low ranking accuracy on various datasets. The plots display the ranking accuracy of several LLMs before and after preference tuning using different methods (RLHF and DPO). The low accuracy highlights that these models struggle to consistently rank preferred outputs above less preferred outputs, even when trained specifically for this purpose. The figure also shows the random chance accuracy as a baseline for comparison. This indicates a significant gap between current models and the ideal performance.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs exhibit low ranking accuracy (less than 60%) on various preference datasets. The plots compare the ranking accuracy of pre-trained and fine-tuned models (reference models) against models trained with preference learning algorithms (RLHF and DPO). The random chance accuracy is shown for comparison. The datasets used include: UltraFeedback, HH-RLHF, SHP, Synthetic Instruct GPT-J Pairwise, and StackExchange Preferences.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs exhibit low ranking accuracy across various datasets. The low accuracy highlights a significant gap between the observed accuracy and the idealized accuracy achievable under perfect conditions. This gap indicates that current preference learning methods struggle to effectively improve the ranking ability of LLMs, even when provided with perfect training data.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs have low ranking accuracy (below 60%) across various datasets. The left panel displays the ranking accuracy of various reference models, while the right panel shows the ranking accuracy of various preference-tuned models. The random chance accuracy is shown for comparison.

This figure shows the ranking accuracy of various reference and preference-tuned LLMs on several preference datasets. The results reveal that most models, even those fine-tuned with preference learning algorithms (RLHF and DPO), achieve surprisingly low ranking accuracy (generally below 60%). The figure highlights the significant gap between the observed and idealized ranking accuracies.

This figure shows the ranking accuracy of various reference and preference-tuned LLMs on several datasets. It demonstrates that both reference models (before preference tuning) and state-of-the-art preference-tuned models achieve surprisingly low ranking accuracies (generally below 60%), highlighting a significant gap between the observed accuracy and the ideal achievable accuracy under perfect conditions.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs exhibit low ranking accuracy (below 60%) across several datasets. The left plot (a) shows ranking accuracy for various reference models (before preference tuning), while the right plot (b) displays the ranking accuracy after preference tuning using either RLHF or DPO. The ‘X’ marks represent the chance accuracy, highlighting the poor performance relative to random guessing. The length-normalized and non-length-normalized accuracy are shown.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned large language models (LLMs) achieve low ranking accuracy across various preference datasets. The plots compare the ranking accuracy of different LLMs, highlighting the significant gap between the observed accuracy and the theoretically achievable accuracy. This discrepancy underscores the challenges faced by preference learning algorithms in effectively learning preference rankings.

This figure shows that both reference and preference-tuned LLMs exhibit low ranking accuracy (below 60%) across various datasets. The plots compare length-normalized and non-length-normalized ranking accuracy, highlighting a significant gap between the achieved accuracy and the idealized accuracy achievable under perfect conditions. The figure underscores a key finding of the paper: preference learning algorithms struggle to significantly improve ranking accuracy.

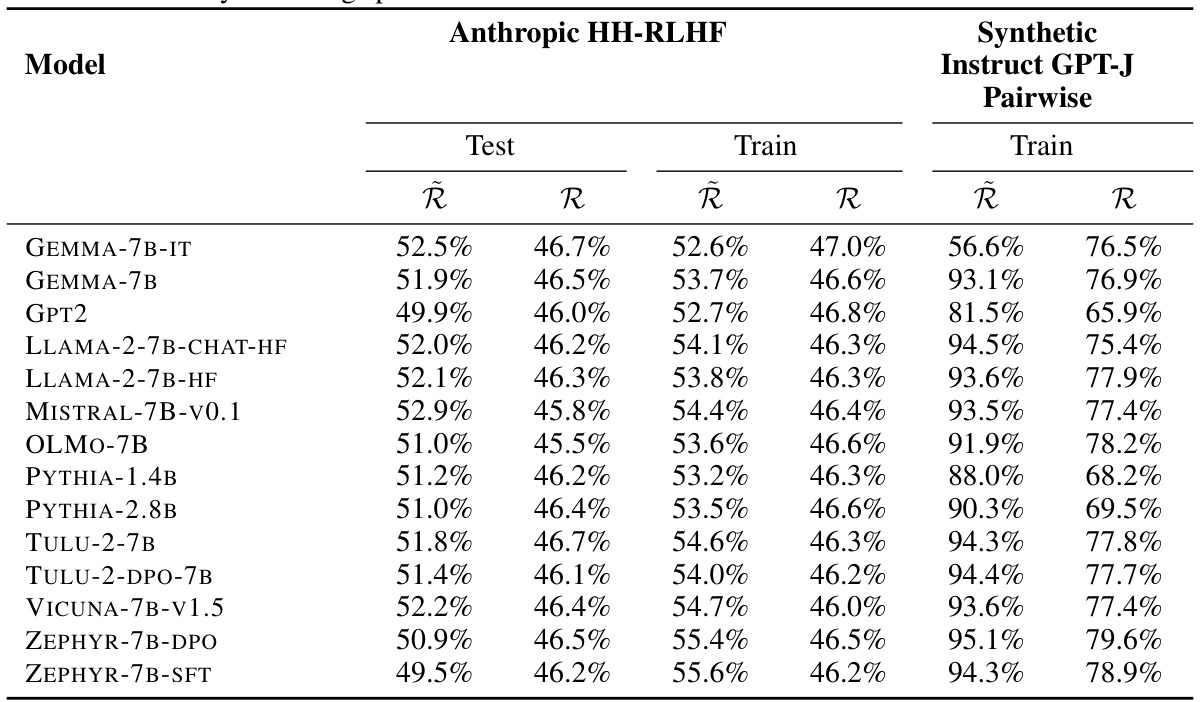

More on tables

This table presents the ranking accuracy of various language models on two different preference datasets: Anthropic HH-RLHF and Synthetic Instruct GPT-J Pairwise. Ranking accuracy is calculated with and without length normalization. The table shows that most models have similar length-normalized ranking accuracy across datasets, with length-normalized accuracy consistently higher than non-length-normalized accuracy. Note that the Synthetic Instruct GPT-J Pairwise dataset only has a training split available.

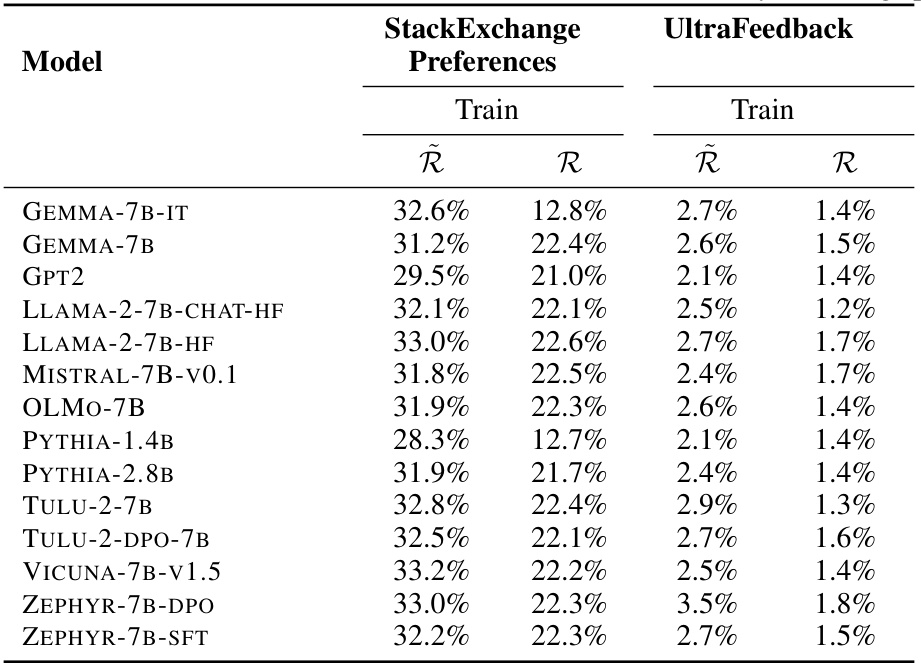

This table presents the length-normalized (Ř) and non-length-normalized (R) ranking accuracies for a variety of open-access LLMs on the StackExchange Preferences and UltraFeedback datasets. Both datasets only include training splits. The table shows the performance of various models in ranking the preferred continuation over less preferred continuations for a given prompt, which is a key aspect of preference learning.

This table presents a comparison of the actual ranking accuracy of several preference-tuned LLMs against their idealized ranking accuracy. The idealized accuracy represents what would be achievable if the models perfectly optimized the DPO or RLHF objective with ground-truth preference data. The table shows a significant gap between the actual and idealized accuracies, indicating a substantial limitation of current preference learning techniques.

This table presents a comparison of the actual ranking accuracy of several preference-tuned LLMs against their idealized ranking accuracy (the accuracy they would achieve if they perfectly optimized the DPO or RLHF objective). The table highlights the significant ‘alignment gap’ between the observed and idealized accuracies, indicating that current models are far from achieving optimal performance. Length-normalized and non-length-normalized accuracies are provided, along with minimum, median, and maximum idealized accuracies for a range of β values.

This table presents the length-normalized and non-length-normalized ranking accuracies for four different preference-tuned LLMs on the Alpaca Farm validation dataset. It also shows the minimum, median, and maximum idealized ranking accuracies for a range of beta values, offering a comparison between the actual performance of these models and the theoretical maximum achievable under ideal conditions (considering ties in the data). The difference highlights the ‘alignment gap’ discussed in the paper.

This table presents the idealized and actual ranking accuracies for several preference-tuned LLMs. It compares the ranking accuracy achievable under perfect conditions (idealized) to the real-world performance of existing models on the Alpaca Farm validation dataset. The table highlights the significant ‘alignment gap’ between idealized and actual performance, which is a key finding of the paper.

This table presents the idealized and actual ranking accuracies for several open-access, preference-tuned LLMs on the Alpaca Farm validation dataset. It highlights a significant difference (alignment gap) between the idealized accuracy (what would be achieved with perfect optimization and ground-truth data) and the observed accuracy of existing models. The table also shows the minimum, median, and maximum idealized ranking accuracies for a range of beta values (hyperparameter in RLHF/DPO objectives).

This table compares the actual ranking accuracy of several open-access, preference-tuned LLMs against their idealized ranking accuracy (i.e., the accuracy they would achieve if they perfectly optimized the DPO or RLHF objective). The table highlights the significant gap between the observed and idealized ranking accuracies, illustrating a key finding of the paper that even under ideal conditions, these models struggle to achieve high ranking accuracy.

This table shows the idealized ranking accuracy compared to the actual ranking accuracy achieved by several open-access preference-tuned LLMs. The idealized accuracy represents the performance a model would achieve if it perfectly optimized the DPO or RLHF objective using ground truth preference data. The table highlights a significant ‘alignment gap’ between the idealized and observed ranking accuracies, indicating that current preference learning algorithms struggle to achieve high ranking accuracies even under ideal conditions. Both length-normalized and non-length-normalized results are provided for different models, along with the range of idealized accuracies for various beta values.

This table presents the length-normalized and non-length-normalized ranking accuracies for various open-access preference-tuned models on the Alpaca Farm validation dataset. It also shows the idealized ranking accuracy achievable under perfect conditions, highlighting the significant gap between the observed and idealized performance. The table emphasizes the limitations of current preference-tuning methods in achieving high ranking accuracy, even when the objective is perfectly optimized.

Full paper#