↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large-scale datasets pose challenges for machine learning, especially concerning fairness. Existing methods often prioritize local fairness properties, sometimes neglecting downstream performance or impacting generalizability. There is a crucial need for efficient techniques to create smaller, representative datasets that effectively address bias while preserving model utility.

Fair Wasserstein Coresets (FWC) is introduced as a novel coreset method. It uses an efficient algorithm to minimize the Wasserstein distance between the original and synthetic data, enforcing demographic parity to achieve fairness. FWC’s performance is evaluated across various datasets, showing competitive fairness-utility tradeoffs and superior bias reduction in large language models compared to existing approaches. The algorithm’s efficiency and theoretical properties, including its equivalence to Lloyd’s algorithm for k-medians/k-means in unconstrained settings are highlighted.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on fairness in machine learning and coreset methods. It bridges the gap between fairness and efficiency by introducing a novel approach that generates fair synthetic data while minimizing the amount of data needed. This is highly relevant to the current focus on responsible AI and large-scale data handling, opening new avenues for research in fair data summarization and bias mitigation.

Visual Insights#

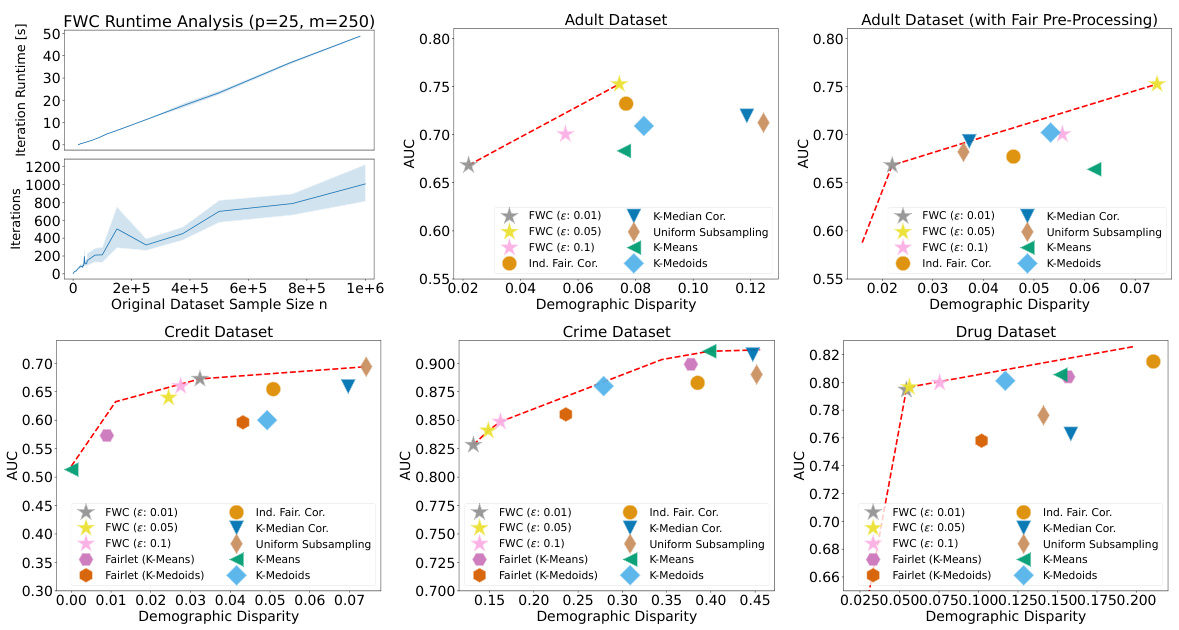

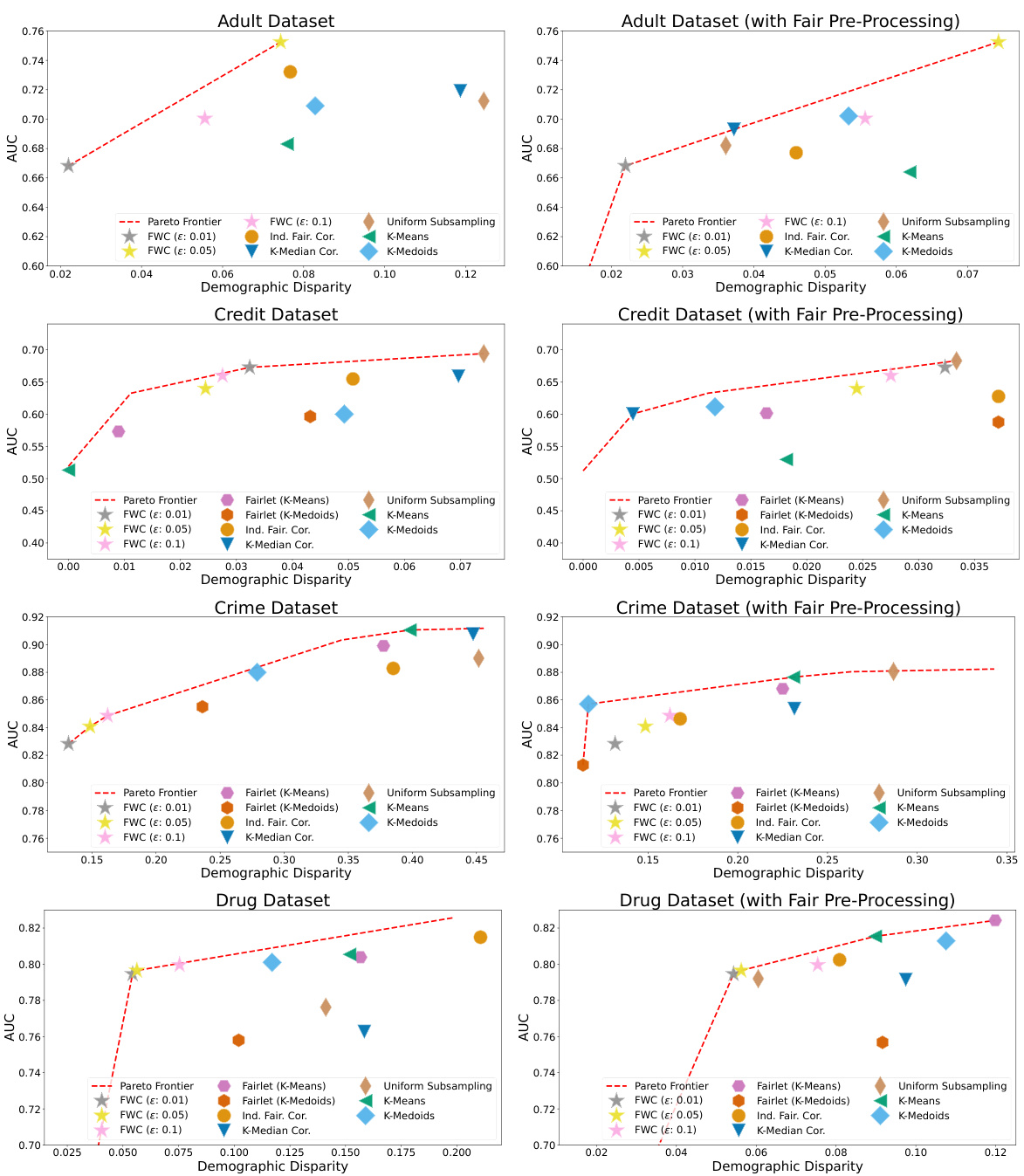

This figure demonstrates the runtime performance of the Fair Wasserstein Coresets (FWC) algorithm and its fairness-utility trade-off against other methods on real-world datasets. The top-left plot shows the linear runtime scaling of FWC with increasing dataset size. The other plots display the fairness-utility trade-off for each dataset across various coreset sizes and fairness hyperparameters. Each point represents the best performing model found for a particular coreset size, indicating the optimal balance between fairness and utility for different algorithms. The dashed red line shows the Pareto frontier, illustrating the best possible combination of fairness and utility across all methods and coreset sizes, highlighting FWC’s competitive performance.

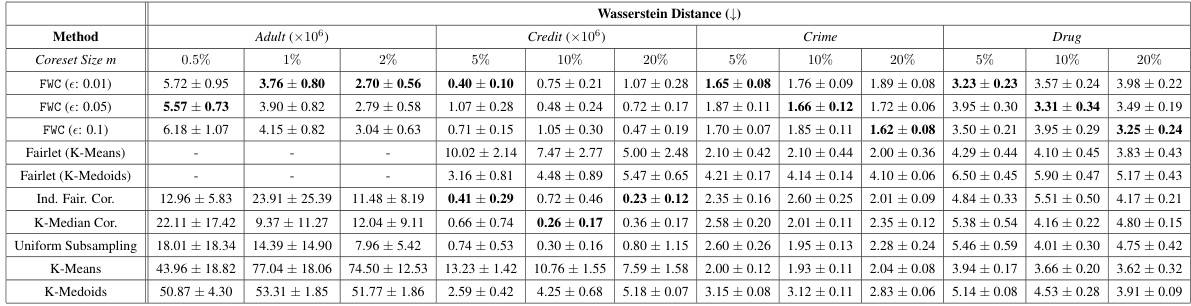

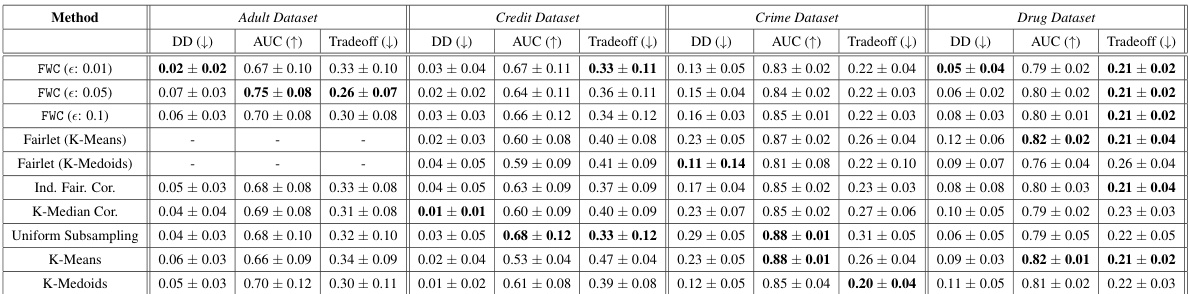

This table presents the Wasserstein distances between the original datasets and the generated coresets for various coreset sizes and fairness parameters (epsilon). The Wasserstein distance measures how similar the distribution of the coreset is to the original data distribution. Lower values indicate a better representation of the original data.

In-depth insights#

Fair Coreset Intro#

A ‘Fair Coreset Intro’ section would ideally begin by establishing the core problem: the need for efficient data summarization techniques that are also fair. It should highlight the limitations of traditional coreset methods in addressing fairness concerns, such as their potential to exacerbate existing biases present in the original dataset. The introduction would then naturally transition into the motivation for creating fair coresets, emphasizing the potential for improved downstream fairness in machine learning applications. This should clearly articulate the benefits of using smaller, representative subsets, reducing computational costs and storage requirements while preserving or even enhancing fairness. The introduction should conclude with a concise overview of the proposed method’s contributions. It is critical to mention the key innovations, whether it involves novel algorithms or modifications to existing ones to achieve demographic parity or other fairness metrics. The introduction should set the stage for the technical details, empirical results, and broader impact discussions to follow in subsequent sections. Finally, it should explicitly state the main goals, either to generate a fairer, smaller dataset, or improve downstream fairness using a fair coreset technique.

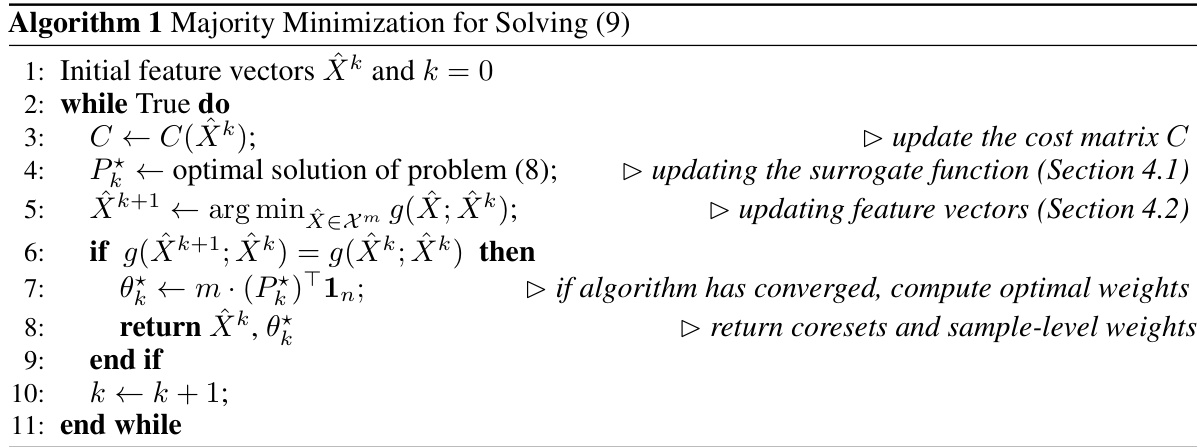

FWC Algorithm#

The Fair Wasserstein Coresets (FWC) algorithm is a novel approach to data distillation that generates a fair and representative subset of a larger dataset. Its core innovation lies in simultaneously minimizing the Wasserstein distance between the original and synthetic datasets while enforcing demographic parity. This dual objective is achieved using an efficient majority minimization algorithm, which iteratively refines both the synthetic samples and their weights. A key theoretical contribution is the demonstration that, without the fairness constraint, FWC simplifies to Lloyd’s algorithm for k-medians/k-means clustering, significantly broadening its applicability beyond fair machine learning. The algorithm is shown to be computationally efficient and effective in empirical evaluations, achieving competitive fairness-utility tradeoffs across various datasets. Its ability to reduce biases in predictions from large language models is particularly noteworthy. However, limitations include its dependence on convexity assumptions of the feature space and the lack of theoretical guarantees in non-i.i.d. scenarios of downstream tasks.

FWC Experiments#

The FWC Experiments section would detail the empirical evaluation of the Fair Wasserstein Coresets method. This would involve a thorough exploration of FWC’s performance on various datasets, comparing it against existing state-of-the-art fair coreset and clustering techniques. Synthetic datasets would likely be used to control for confounding factors and establish baselines, while real-world datasets with known biases would demonstrate FWC’s efficacy in practical settings. Key metrics for evaluation would include measures of fairness (e.g., demographic parity) and utility (e.g., accuracy of downstream models). A critical aspect would be an analysis of the tradeoff between fairness and utility, showing whether FWC achieves a competitive balance compared to other methods. The experiments should also assess FWC’s scalability and efficiency across varying dataset sizes and dimensionality, potentially including runtime analysis. Finally, detailed explanations of the experimental setup, including dataset preprocessing, model choices, and hyperparameter tuning would be essential for reproducibility and validation of the results.

FWC Limitations#

The limitations section for Fair Wasserstein Coresets (FWC) highlights several key weaknesses. Coreset support and non-convex feature spaces pose challenges, as the synthetic data points might fall outside the original dataset or within low-density regions of non-convex spaces, limiting the method’s applicability and generalizability. Computational bottlenecks are also identified, arising from the O(mn) complexity of establishing the cost matrix which can be computationally expensive for large datasets, though improvements could be leveraged by GPU implementations akin to K-Means. The connection between the fairness hyperparameter epsilon (∈) and downstream learning is another significant limitation; while limiting fairness violations improves downstream fairness, it also introduces a distribution shift, and the relationship between ∈ and the extent of this shift remains incompletely understood. Finally, while FWC targets demographic parity, its performance on other fairness criteria such as equalized odds remains unclear, limiting its applicability.

Future of FWC#

The future of Fair Wasserstein Coresets (FWC) looks promising, with several avenues for expansion. Improving computational efficiency remains a key challenge; current algorithms can struggle with large datasets. Exploring alternative optimization techniques or leveraging distributed computing could significantly enhance scalability. Extending FWC’s applicability to diverse learning tasks is another important direction. While the paper demonstrates success in classification and bias reduction in LLMs, investigating FWC’s effectiveness in other domains (e.g., regression, reinforcement learning) would reveal its broader impact. Developing theoretical guarantees for FWC’s generalization performance on unseen data is crucial for establishing its reliability. Current theoretical analyses are limited; stronger results would further solidify FWC’s position as a robust coreset method. Finally, investigating the interaction between fairness constraints and other coreset properties (e.g., accuracy, size) is essential. A deeper understanding of this tradeoff would allow for better parameter tuning and optimization for specific fairness-utility requirements.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the runtime analysis of the Fair Wasserstein Coresets (FWC) algorithm. The left panel displays the runtime per iteration and the number of iterations as a function of the coreset sample size (m) while keeping the dimensionality of features (p) and the original dataset size (n) constant. The right panel displays the same metrics but this time as a function of the dimension of features (p) while keeping the coreset sample size (m) and the original dataset size (n) constant. Error bars represent one standard deviation calculated over 10 runs. The figures demonstrate the algorithm’s scalability and performance under different parameter settings.

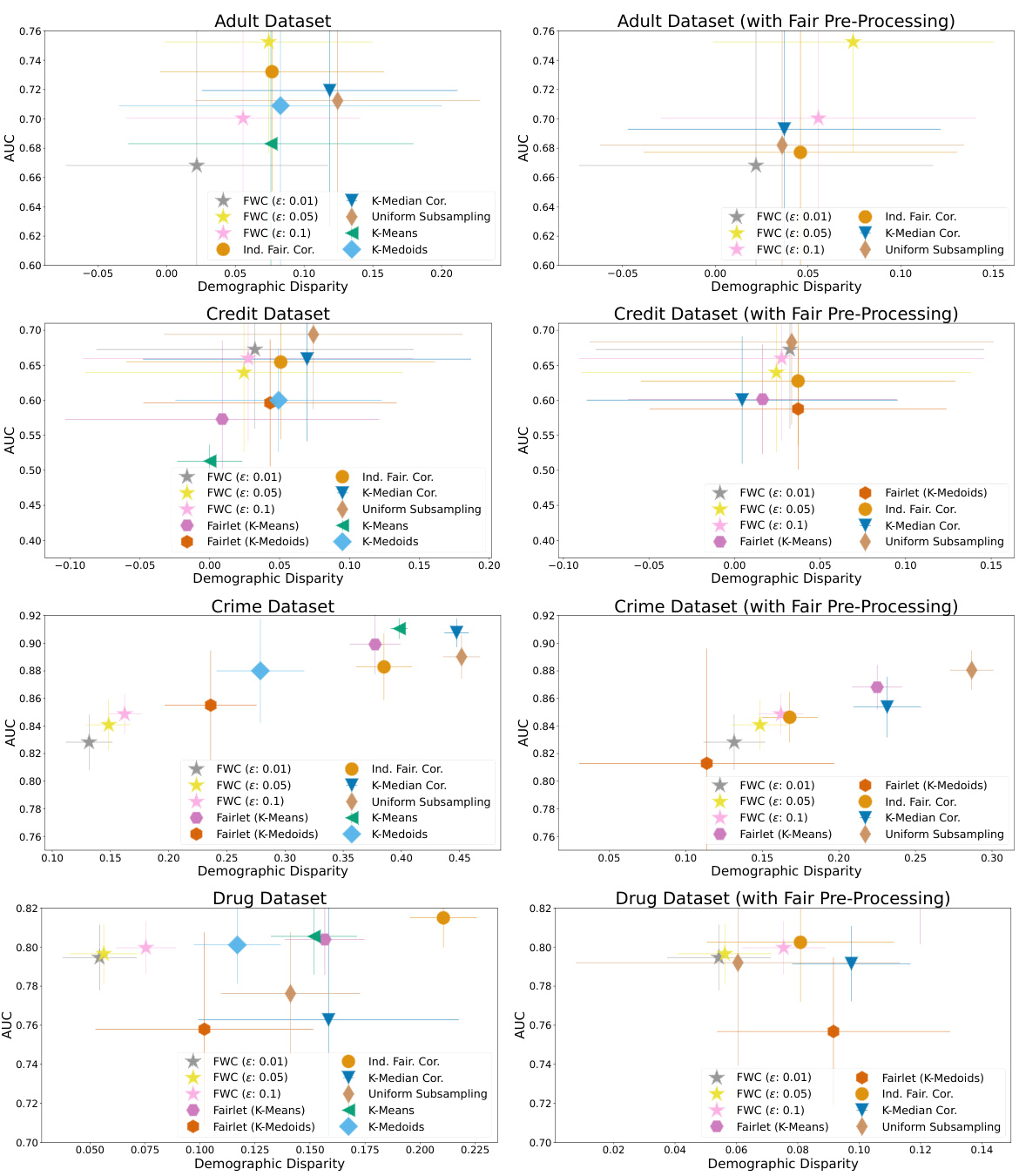

This figure shows the results of experiments on real-world datasets. The top-left subplot displays the runtime of FWC as the size of the original dataset increases. The remaining subplots illustrate the fairness-utility tradeoff achieved by FWC and other methods for a downstream MLP classifier. Each subplot represents a different dataset and shows the AUC (utility) against demographic disparity (fairness) for various methods and coreset sizes. The Pareto frontier is plotted to highlight the best possible tradeoffs.

This figure displays the runtime of the Fair Wasserstein Coresets (FWC) algorithm as a function of the dataset size and also shows fairness-utility tradeoffs for several real-world datasets. The Pareto frontier highlights the competitive performance of FWC compared to other methods, even when those other methods use pre-processing techniques to improve fairness.

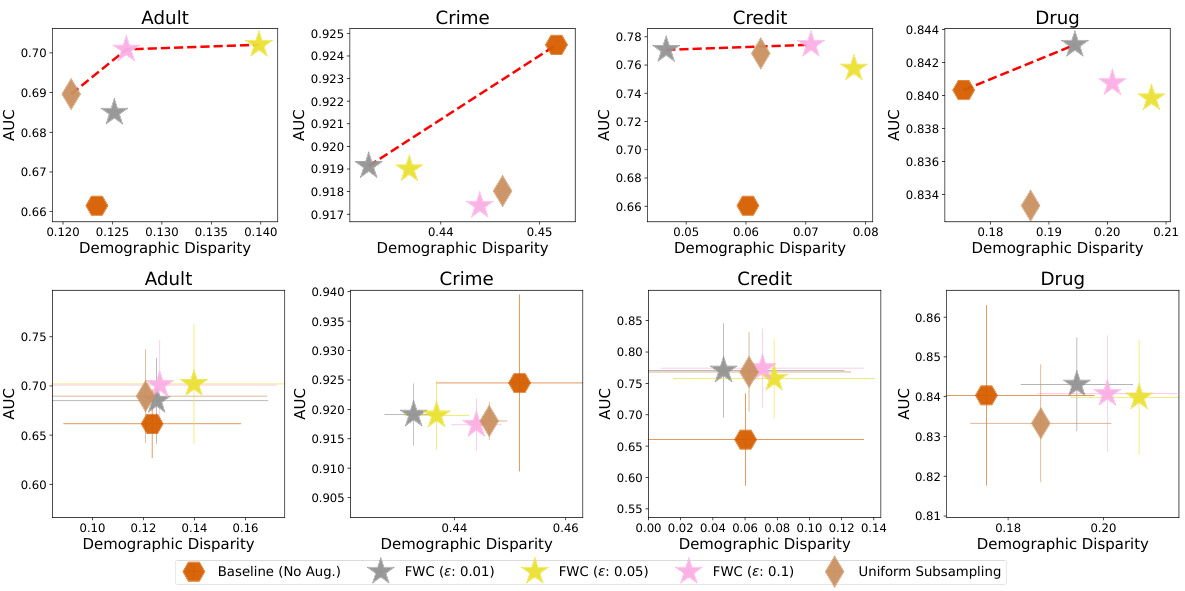

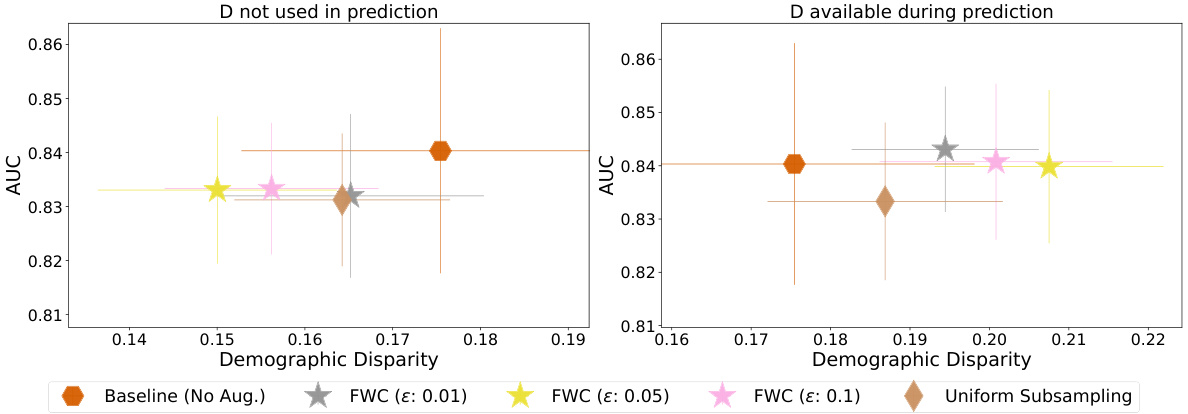

This figure shows the fairness-utility tradeoff of a downstream MLP classifier for the Drug dataset when using data augmentation with FWC. The left panel shows results when the protected attribute ‘gender’ is not used as a predictor variable, while the right panel includes ‘gender’. The results indicate that FWC effectively reduces disparity when gender is excluded but not when included. This suggests gender’s strong predictive power on the outcome might require additional fairness techniques beyond FWC.

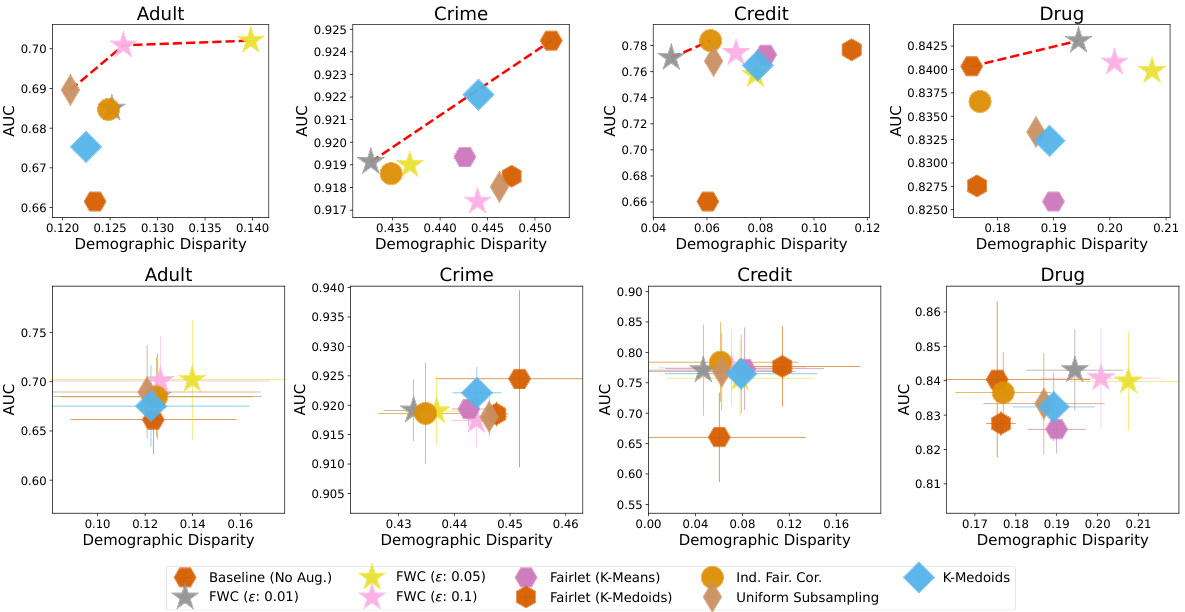

This figure shows the runtime of the Fair Wasserstein Coresets (FWC) algorithm when varying the dataset size and the fairness-utility tradeoffs obtained by using FWC and other baselines on several real-world datasets. The Pareto frontier is displayed to highlight the best tradeoff between fairness and utility across all methods and coreset sizes. The results show that FWC consistently achieves a competitive or better fairness-utility tradeoff compared to existing approaches.

This figure shows the runtime of FWC (top left) and the fairness-utility tradeoff on four real-world datasets (others). The runtime analysis demonstrates that FWC’s runtime scales linearly with the dataset size. The fairness-utility analysis compares FWC with several other fair clustering methods, showing that FWC consistently achieves a competitive or better tradeoff in downstream models compared to existing approaches, even when fairness pre-processing is used.

More on tables

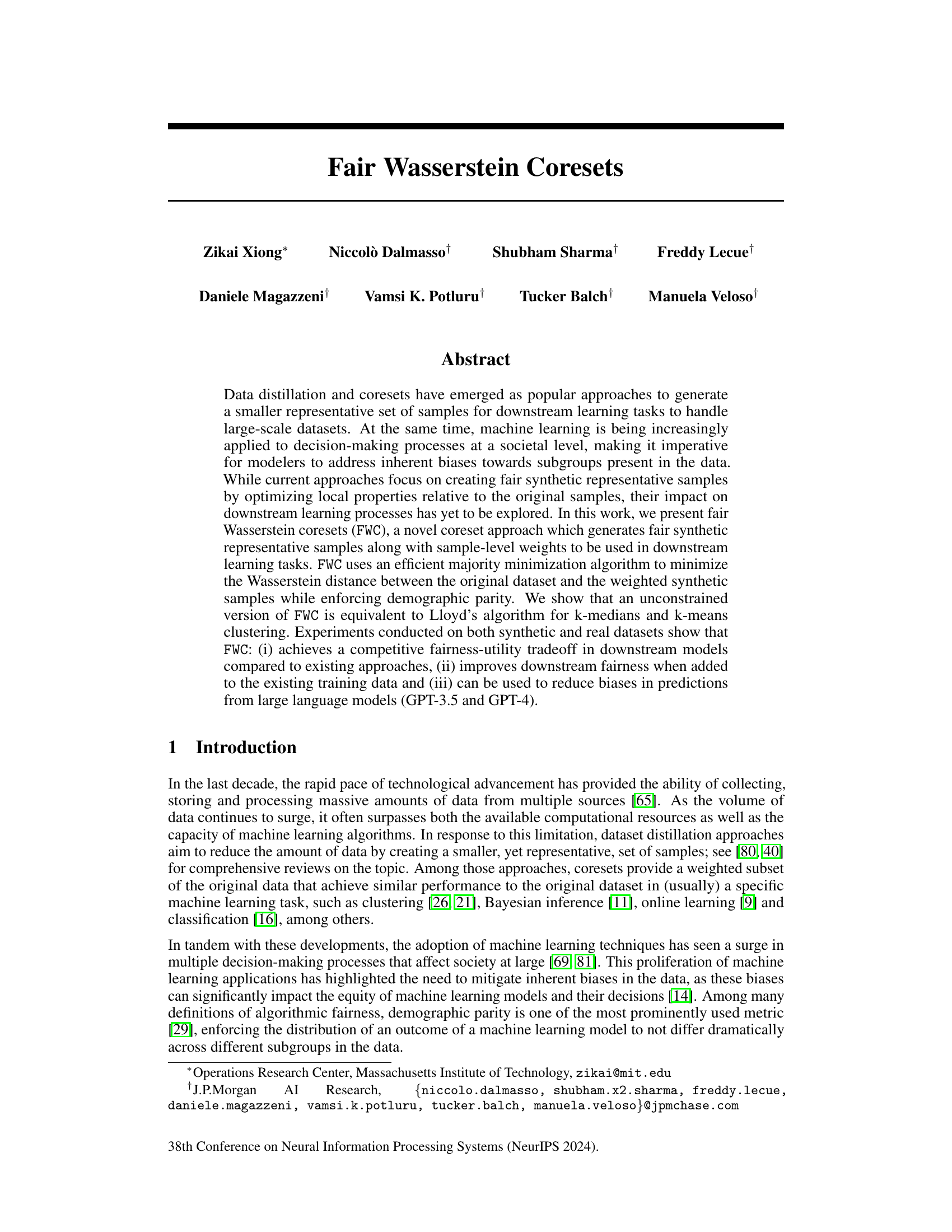

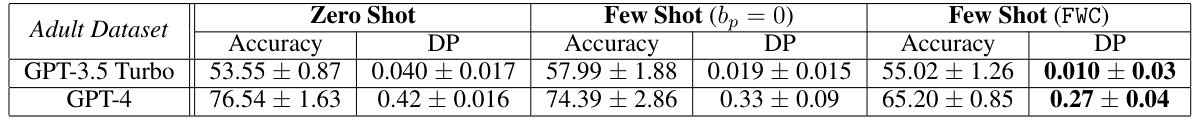

This table compares the performance of GPT-3.5 Turbo and GPT-4 language models on a fairness prediction task using three different approaches: zero-shot, few-shot with balanced examples, and few-shot with Fair Wasserstein Coresets (FWC). The metrics evaluated are accuracy and demographic parity (DP). The FWC approach uses a weighted set of examples to improve fairness, highlighting its ability to mitigate biases in large language models.

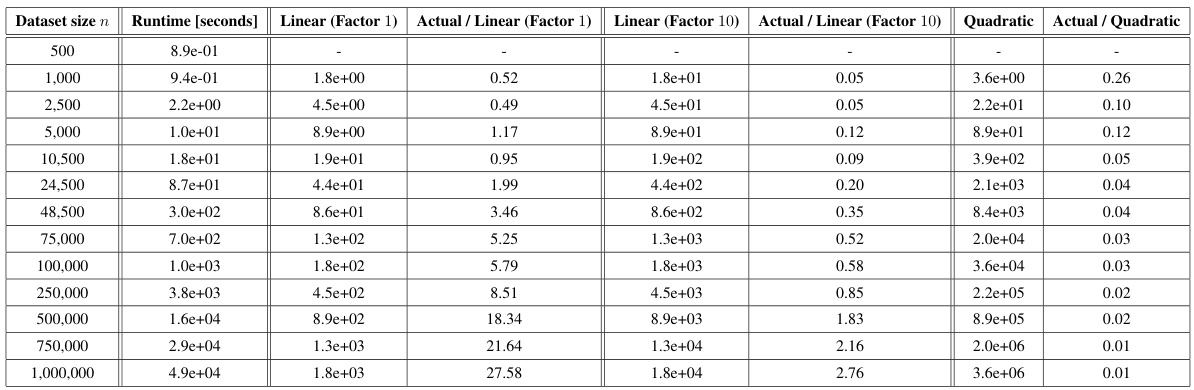

This table shows the runtime of the Fair Wasserstein Coresets (FWC) algorithm for different dataset sizes (n). It compares the actual runtime to estimations based on linear and quadratic extrapolations from the smallest dataset size. The results suggest that FWC exhibits near-linear time complexity.

This table presents the Wasserstein distance between the original dataset and the generated coresets for different coreset sizes (m) and fairness violation hyperparameters (ε). The Wasserstein distance measures the similarity in distribution between the original and coreset data. Smaller distances indicate a better representation of the original data by the coresets. The table shows that FWC consistently achieves the smallest Wasserstein distances for all datasets and coreset sizes, highlighting its effectiveness in generating representative samples.

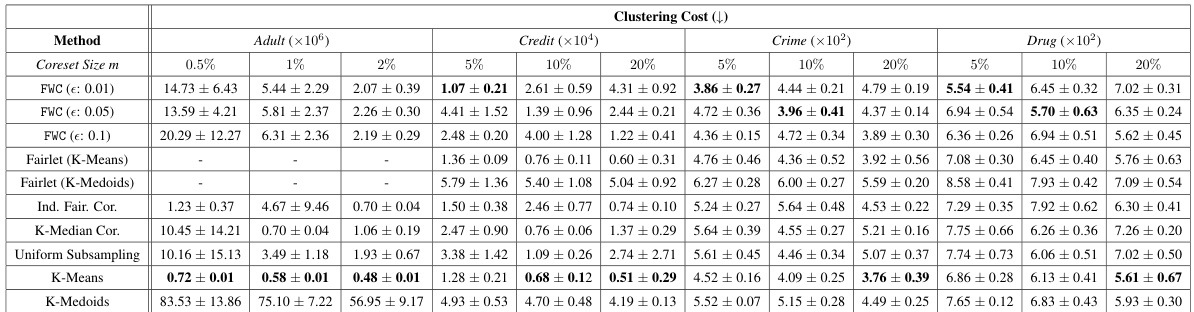

This table shows the clustering cost for different coreset methods across four datasets. The clustering cost is calculated as the sum of squared distances between each point in the original dataset and its nearest point in the generated coreset. Lower values indicate better coreset quality in terms of representing the original data’s structure. The table displays average clustering cost and standard deviations, obtained from 10 independent runs, for each method and dataset, across different coreset sizes (5%, 10%, 20%).

This table presents the Wasserstein distances between the weighted coresets generated by different methods and the original datasets. Lower values indicate a better representation of the original data by the coreset. The results are averaged over 10 runs, and the coresets with the smallest Wasserstein distance for each dataset and coreset size are highlighted in bold. This helps assess how well the different methods create coresets that maintain the original data distribution.

This table presents the Wasserstein distance between the weighted coresets generated by different methods and the original datasets for four benchmark datasets. The Wasserstein distance is a metric that measures the dissimilarity between two probability distributions. Lower values indicate a closer resemblance between the coreset and the original data. The table shows that FWC consistently achieves the lowest Wasserstein distance compared to other methods across different coreset sizes.

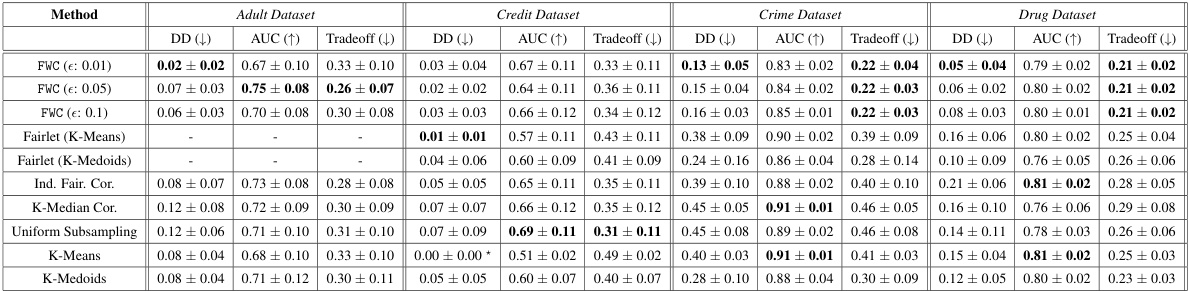

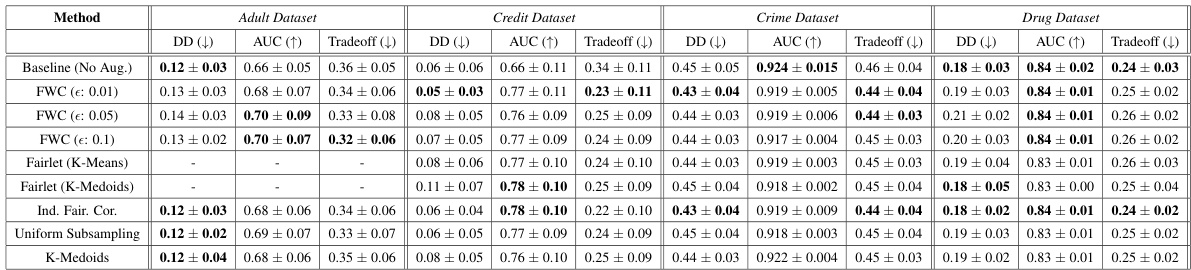

This table shows the Demographic disparity, AUC, and fairness-utility tradeoff for different coreset methods on four real-world datasets. The best performing method for each metric and coreset size is highlighted. Note that the Credit dataset shows artificially low disparity for K-means due to a trivial classifier.

This table shows whether FWC achieves a competitive fairness-utility tradeoff (Pareto frontier) when considering both demographic parity and equalized odds. It highlights that while FWC performs well for demographic parity across all datasets, its performance is not as consistent for equalized odds, indicating that optimizing for one fairness metric does not guarantee optimization for others.

Full paper#