↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The accuracy of machine learning models is often assessed using the expected calibration error (ECE), which relies on binning strategies. However, a comprehensive theoretical understanding of the estimation bias in ECE was previously lacking, hindering accurate calibration evaluations. Existing research mainly concentrated on one common binning approach, leaving a gap in knowledge for another frequently used approach. Furthermore, generalization error analysis for ECE was also absent, making it difficult to predict performance on unseen data.

This paper addresses these issues by providing a comprehensive analysis of ECE’s estimation bias for both uniform mass and uniform width binning strategies. The researchers derived upper bounds on the bias, offering improved convergence rates, and identified the optimal number of bins. Their analysis was extended to generalization error using an information-theoretic approach, leading to upper bounds facilitating the numerical evaluation of ECE’s accuracy for unseen data. Experiments confirmed the practicality of their approach.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on calibration in machine learning. It offers rigorous theoretical analysis of expected calibration error (ECE), providing improved convergence rates and identifying the optimal number of bins. This advances the understanding of ECE bias and enables more accurate calibration evaluation. Furthermore, the information-theoretic generalization analysis opens new avenues for studying generalization error in the context of ECE and TCE, impacting future calibration research.

Visual Insights#

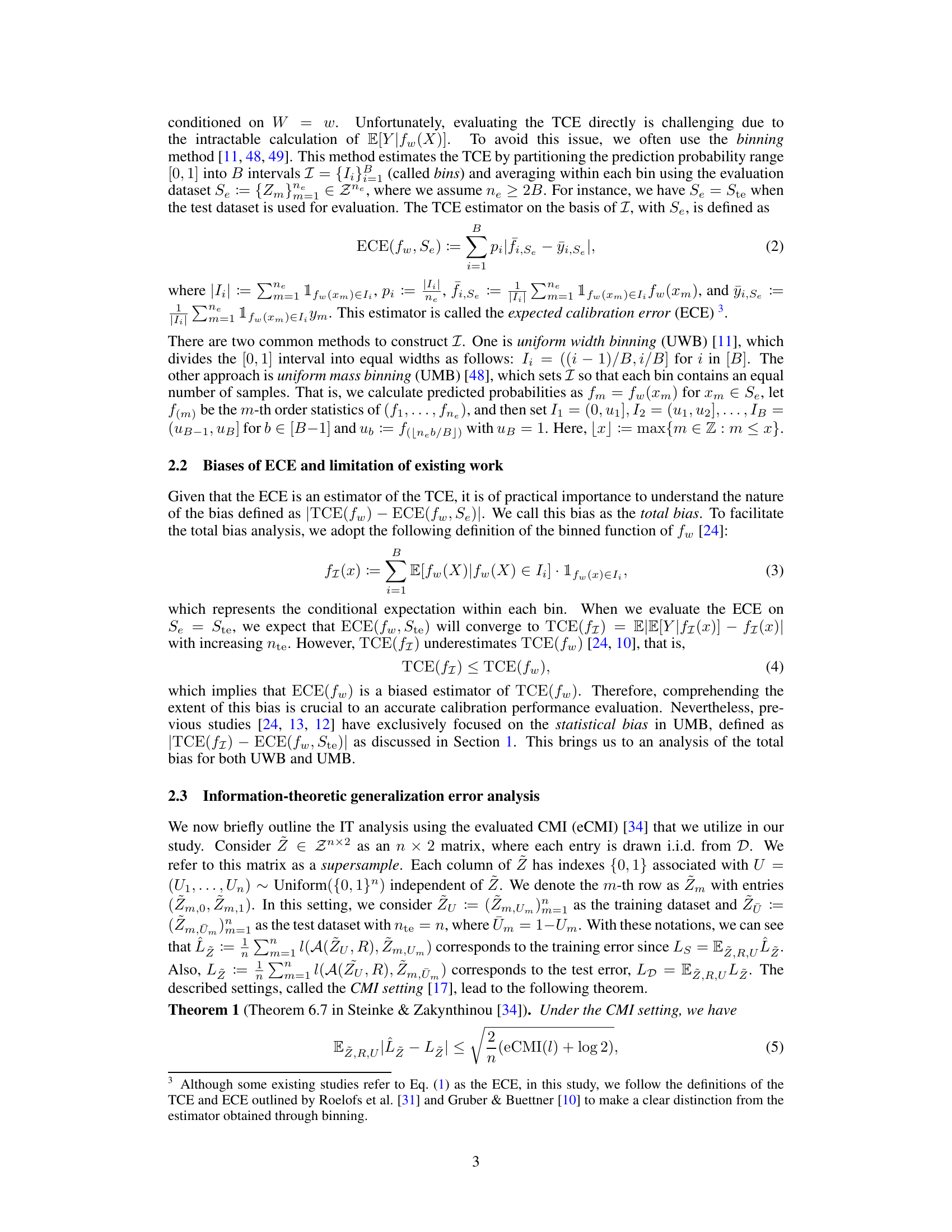

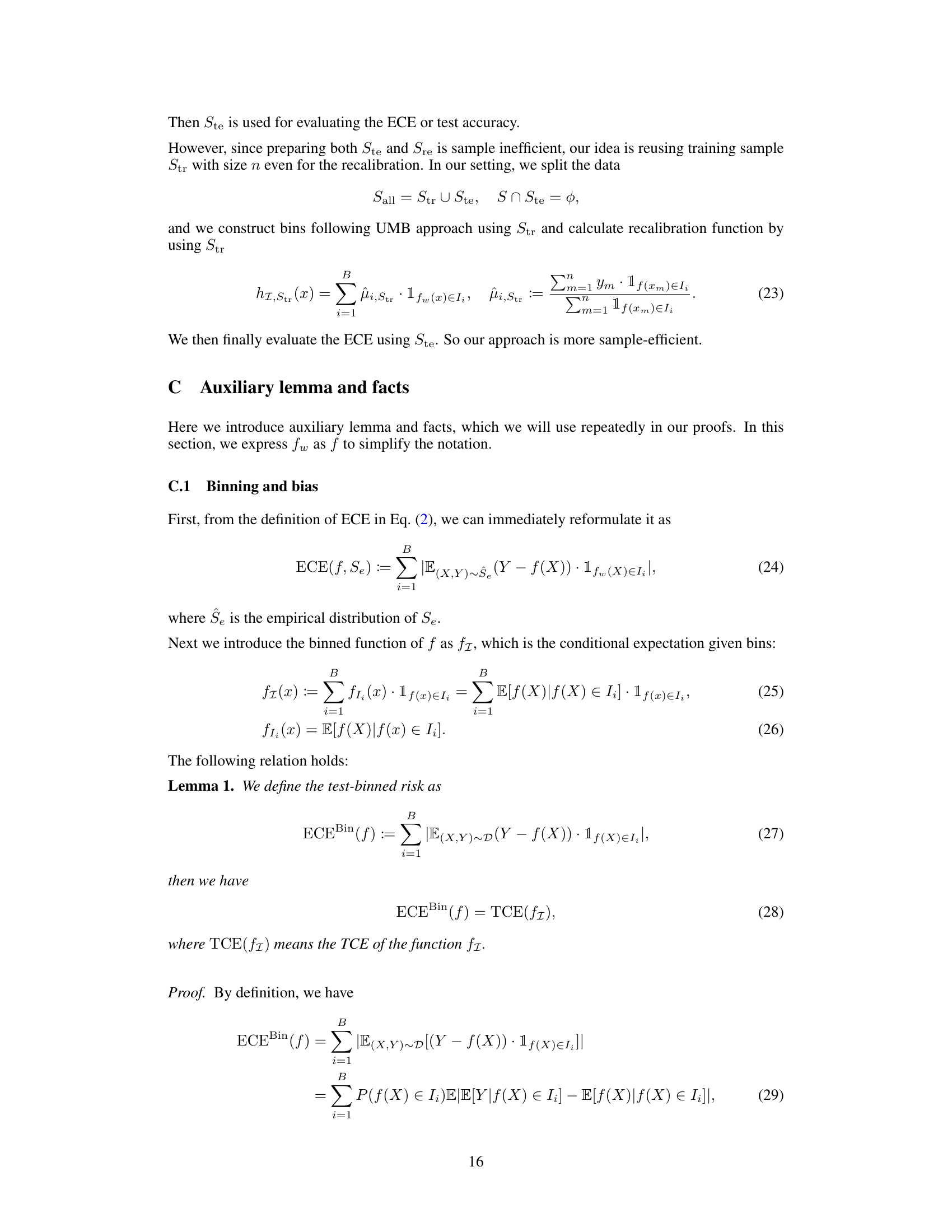

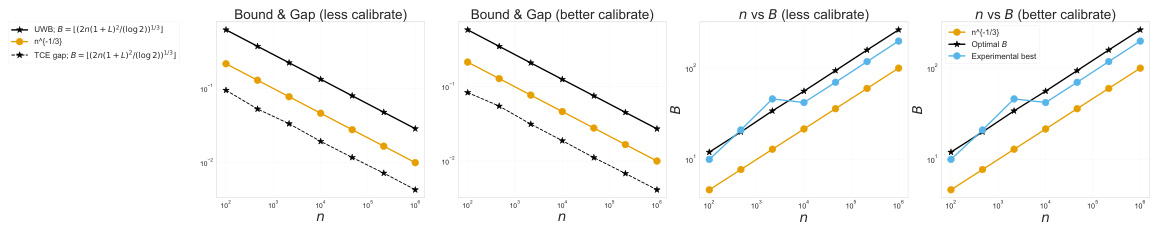

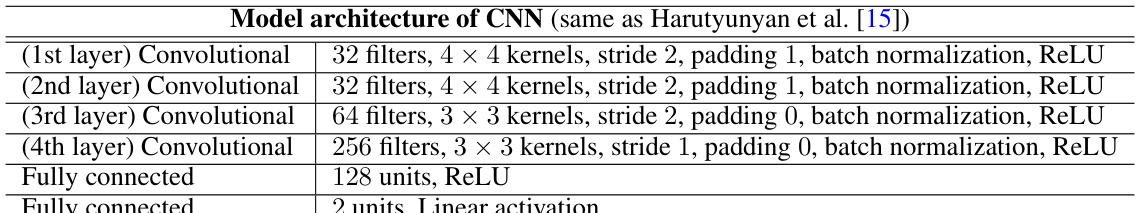

This figure shows the behavior of the upper bound derived in Equation 12 of the paper as the number of training samples (n) increases. The plots illustrate the relationship between the theoretical upper bound (black line), the empirical ECE gap (orange dots), and the optimal bin size (blue dots) for two different scenarios. The ’less calibrate’ scenario represents a less well-calibrated model (worse TCE), and the ‘better calibrate’ scenario represents a better-calibrated model (better TCE). The figure demonstrates how the upper bound, empirical gap, and optimal bin size vary as the number of samples changes, providing empirical evidence to support the theoretical analysis.

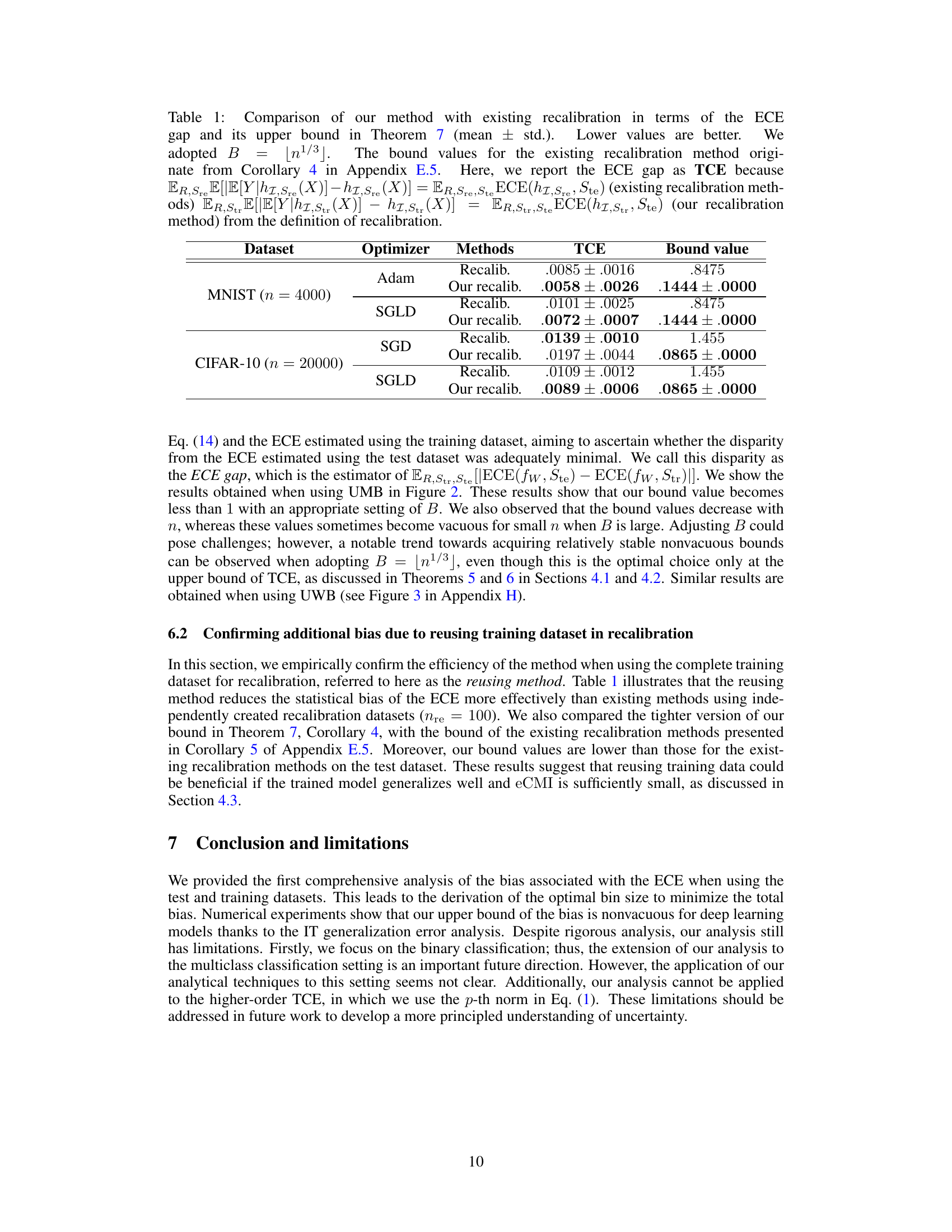

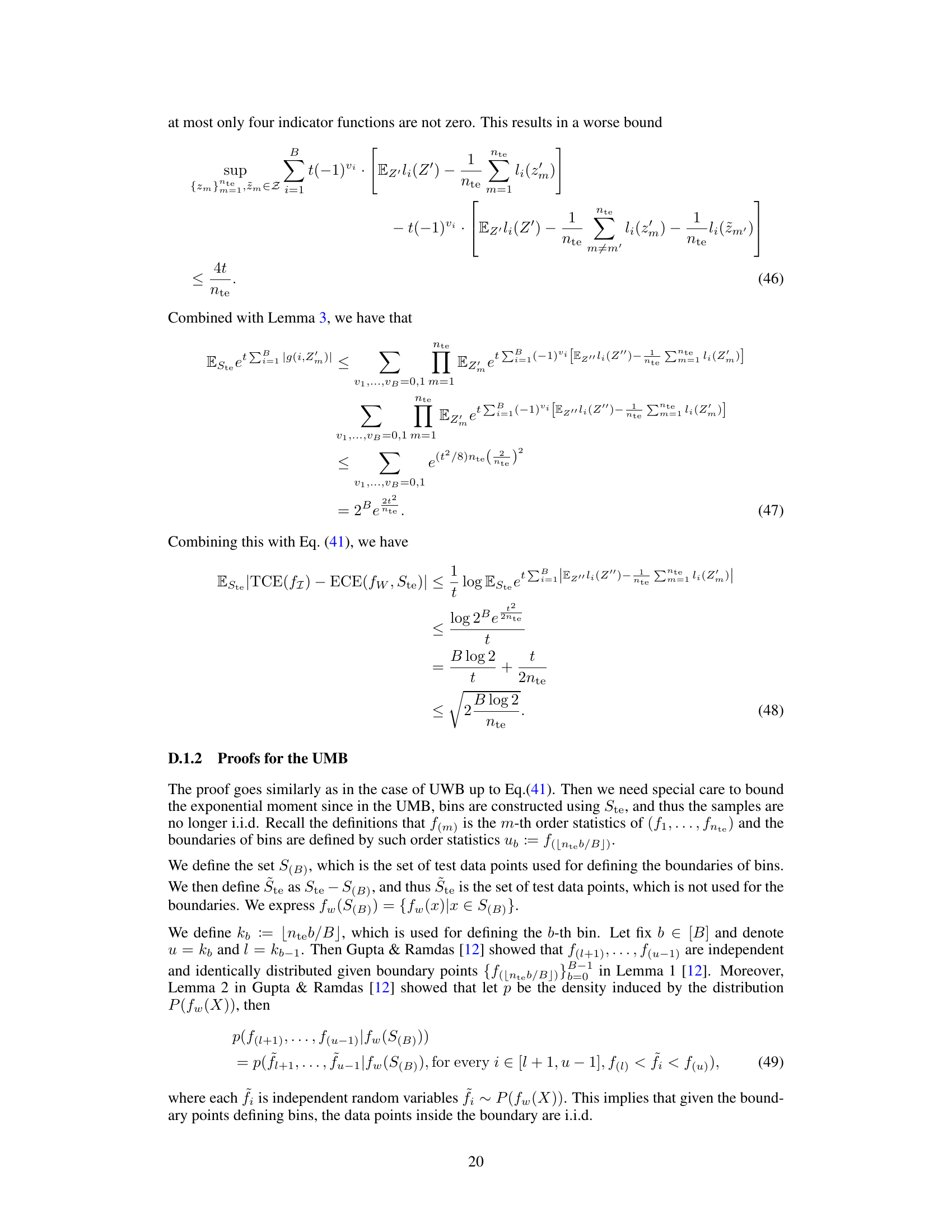

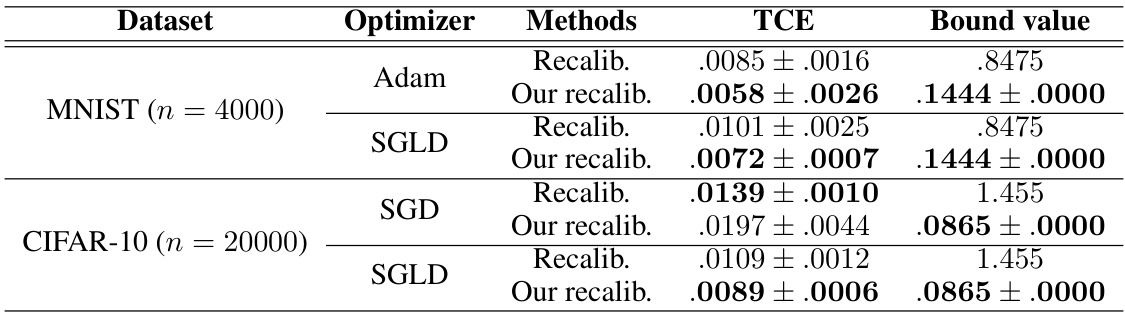

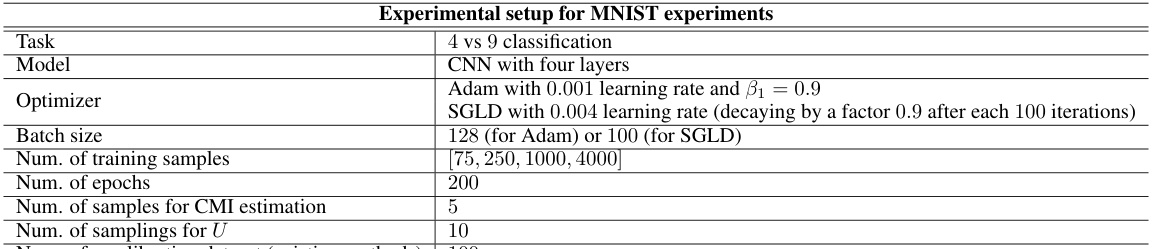

This table compares the performance of the proposed recalibration method with existing methods. It shows the true calibration error (TCE) and the upper bound calculated using Theorem 7 for each method. Lower values for TCE indicate better calibration performance. The table includes results for both MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets, using different optimizers (Adam, SGLD, SGD).

In-depth insights#

ECE Bias Analysis#

ECE bias analysis is crucial for reliable calibration error assessment. It investigates the discrepancy between the estimated expected calibration error (ECE) and the true calibration error (TCE). The analysis typically focuses on the impact of binning strategies (uniform width or mass) and finite sample effects. Understanding these biases allows researchers to determine optimal bin numbers to minimize error and to better interpret ECE values. Information-theoretic approaches provide powerful tools to quantify and bound ECE bias, extending the analysis beyond simply considering finite sample effects to address generalization uncertainty. A key aspect is to derive tight upper bounds on this bias, improving convergence rates and facilitating practical evaluations. Optimal bin size selection emerges as a critical finding, balancing the tradeoff between reduced bias from increased bins and increased variance from smaller sample sizes within each bin. Ultimately, this rigorous analysis leads to more reliable calibration error evaluation and enhances the practical utility of ECE in machine learning applications.

Optimal Bin Size#

The concept of “optimal bin size” in the context of expected calibration error (ECE) analysis is crucial for balancing bias and variance. A smaller bin size reduces binning bias but increases variance due to fewer samples per bin, leading to inaccurate ECE estimations. Conversely, a larger bin size reduces variance but increases binning bias, which means the binned ECE poorly approximates the true calibration error. The optimal bin size aims to find a sweet spot that minimizes the total error (bias + variance). The paper investigates this optimization problem theoretically, providing upper bounds on the total error for different binning strategies and data sample sizes. This theoretical analysis is particularly valuable because it helps determine the optimal bin size before conducting any experiments, resulting in more efficient and accurate calibration evaluation. Moreover, the paper introduces an information-theoretic approach that links the optimal bin size to the generalization error, offering crucial insights into the model’s calibration performance beyond the training dataset. This analysis highlights the importance of considering both bias and variance when evaluating calibration and provides a principled way for choosing the bin size, advancing the theoretical understanding and practical application of calibration error analysis. The theoretical results, therefore, improve on previous works by offering broader generality, tighter bounds, and a novel connection between optimal bin size and generalization error.

Generalization Bounds#

Generalization bounds in machine learning aim to quantify the difference between a model’s performance on training data and its performance on unseen data. Tight generalization bounds are crucial because they provide confidence in a model’s ability to generalize well to new, real-world scenarios. The paper explores these bounds through an information-theoretic lens, focusing on the expected calibration error (ECE). The approach differs from traditional methods by incorporating algorithmic information, offering a more nuanced perspective on how model training affects the generalization gap. The derived bounds improve upon existing results, providing tighter estimates of the ECE and the true calibration error (TCE). A key finding highlights the optimal number of bins for minimizing estimation bias, bridging theory and practice. Furthermore, the information-theoretic analysis facilitates numerical evaluation, enabling researchers to directly quantify the impact of various factors. This is a significant advancement, allowing for more accurate assessment of model calibration and a better understanding of the dynamics between training and generalization.

Recalibration Bias#

Recalibration, aiming to enhance the reliability of predictive probabilities, introduces a unique bias. This recalibration bias arises from using a finite dataset to correct model predictions, often reusing the training data for recalibration. This reuse creates a dependency between the recalibration process and the model’s initial training, leading to overfitting and potentially inflated performance metrics. While recalibration aims to improve calibration accuracy, over-reliance on training data during this step can cause the model to excessively fit the training set’s calibration errors. Consequently, the improved calibration on the training data may not generalize well to unseen data, yielding optimistic results and undermining the true predictive power of the recalibrated model. Therefore, it’s crucial to carefully consider the dataset used in recalibration and to be aware of this inherent bias when interpreting the results. Information-theoretic generalization bounds offer a promising approach to quantify and mitigate this recalibration bias, providing a theoretical framework to assess the trade-off between improved calibration on training data and generalization performance on unseen data.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the theoretical analysis to multi-class classification settings, which presents significant challenges due to the increased complexity of calibration metrics. Another important direction is to develop more robust methods for estimating the conditional expectation E[Y|fw(X)], which is crucial for computing the true calibration error and is currently reliant on binning methods. Investigating the impact of different binning strategies and exploring alternative methods, such as kernel density estimation, could lead to more accurate and efficient calibration error estimations. Further research could also delve deeper into the connection between algorithmic stability and the generalization bounds, providing a more comprehensive theoretical understanding of how different training algorithms affect calibration performance. Finally, exploring the application of these theoretical findings to real-world risk-sensitive applications, such as medical diagnosis and autonomous driving, is essential to assess their practical implications and limitations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the behavior of the upper bound on the total bias of the ECE (expected calibration error) as a function of the number of test samples (n). Two scenarios are shown: one where the model is less well calibrated (worse TCE estimator), and one where it’s better calibrated (better TCE estimator). The plot demonstrates how the upper bound decreases as n increases, indicating improved accuracy in estimating the TCE as more test samples are used. The figure is specifically for uniform width binning (UWB).

This figure shows the behavior of the upper bound derived in Equation 12 of the paper as the number of training samples (n) increases for uniform width binning (UWB). The plots illustrate how the bound changes depending on the calibration performance. ‘Less calibrate’ represents a worse calibration scenario (β = (0.5, -1.5)), while ‘better calibrate’ indicates better calibration (β = (0.2, -1.9)). The figure also highlights the relationship between the bound and the optimal bin size (B), indicating how the choice of B affects the upper bound.

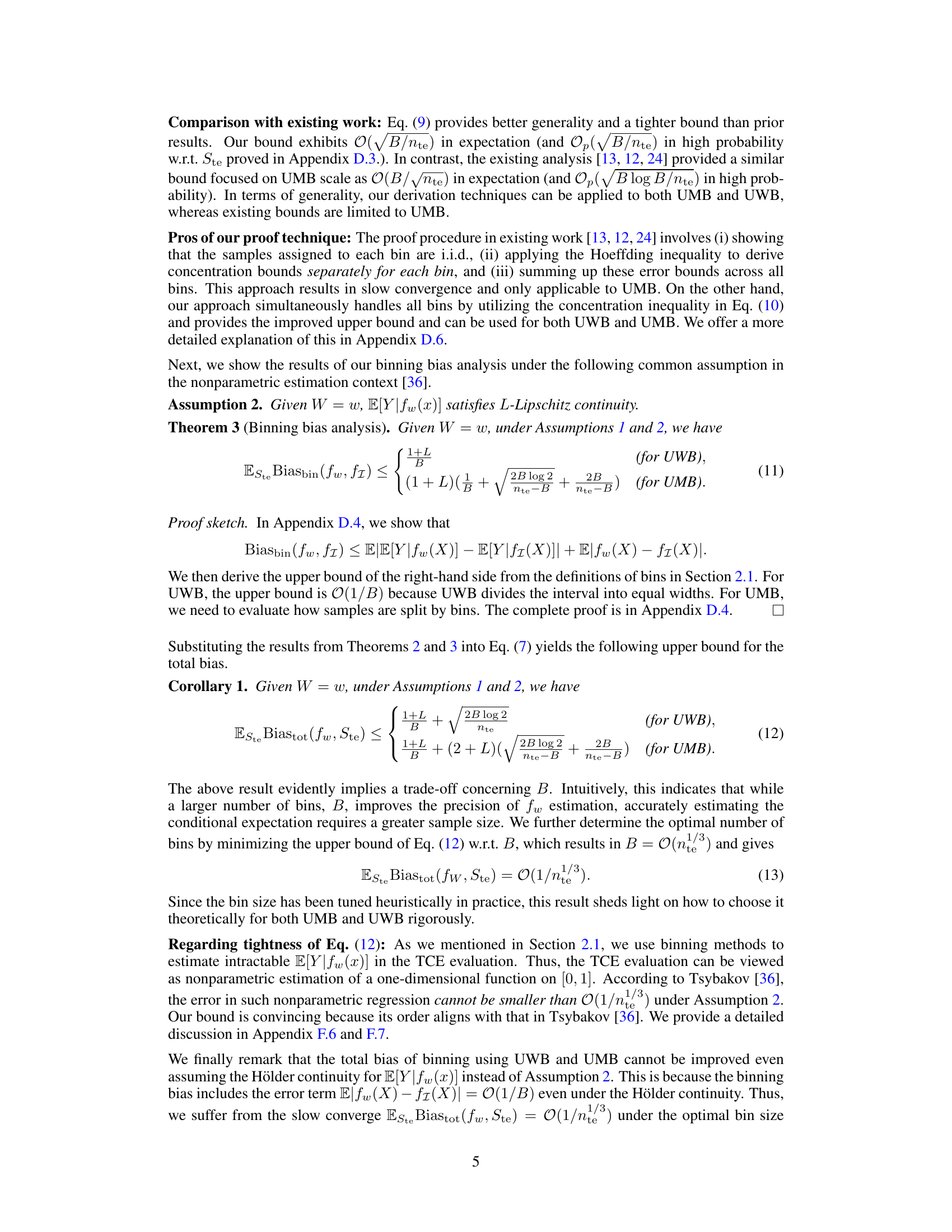

This figure shows how the upper bound derived in Equation 14 of the paper changes with the number of training samples (n) for different numbers of bins (B) when using uniform mass binning (UMB). The plot also shows the actual difference between the theoretical and empirical expected calibration error (ECE), which is called ECE gap in the paper. The results show that the upper bound is reasonably tight and non-vacuous, particularly when the optimal number of bins (B=[n^(1/3)]) is used. The smaller difference between the upper bound and the actual ECE gap indicates that the bound is accurate, particularly when the optimal bin size is selected.

This figure shows the behavior of the upper bound on the total bias of the ECE (Expected Calibration Error) as a function of the number of test samples (n) when using uniform width binning (UWB). Two scenarios are presented: one with a less well-calibrated model (worse TCE estimator) and one with a better-calibrated model. The plot illustrates the trade-off between the number of bins (B) and the sample size (n) in minimizing the total bias, highlighting the theoretical optimal bin size derived in the paper. The lines represent theoretical upper bounds, while the points represent experimental results.

This figure shows the empirical verification of the Lipschitz continuity assumption (Assumption 2) for E[Y|f(X)]. The plots show that the estimator of E[Y|f(X)] obtained via binning has relatively smooth variations, supporting the validity of this assumption. The red line represents a third-order polynomial fit to the estimated values.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of the proposed recalibration method with existing methods in terms of the expected calibration error (ECE) gap and its upper bound. The comparison considers both the mean and standard deviation of the ECE gap and provides the corresponding bound values from Theorem 7 and Corollary 4. Lower values for both ECE gap and bound indicate better calibration performance. The table uses the optimal bin size B = [n1/3] for both methods.

This table compares the performance of the proposed recalibration method with existing methods in terms of the Expected Calibration Error (ECE) gap. It shows the mean and standard deviation of the ECE gap and its theoretical upper bound. Lower values indicate better calibration performance. The optimal bin size B is set to n^(1/3). The table includes results for different datasets (MNIST and CIFAR-10) and optimizers (Adam and SGLD), illustrating the method’s effectiveness across various settings.

This table compares the performance of the proposed recalibration method with existing methods in terms of the expected calibration error (ECE) gap and its upper bound. The comparison is made across different datasets and optimizers. The table uses the optimal number of bins (B = [n^(1/3)]) and shows that the proposed method achieves lower ECE gap and tighter bound values, indicating superior recalibration performance.

Full paper#