↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Transformers, powerful AI models, struggle with complex, multi-step problems. They sometimes simply memorize inputs and outputs instead of truly understanding the underlying logic. This limits their ability to generalize to new situations. Prior research often overlooked the role of model initialization in this behavior.

This paper investigates how the initial settings of transformer models influence their approach to unseen compositional tasks. They found that smaller initial values encourage reasoning, while larger ones lead to memorization. Analyzing information flow within the models showed that reasoning models learn to combine simpler operations, while memorizing models directly map inputs to outputs without breaking down the task into smaller components. The finding of an optimal initialization range was validated across diverse models and datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals how a model’s initialization significantly impacts its ability to reason versus memorize in complex tasks. This understanding can greatly improve the design and training of more robust AI models, particularly in applications requiring both memory and reasoning abilities. It also opens up new avenues for research into hyperparameter tuning and the inherent complexity of deep learning models.

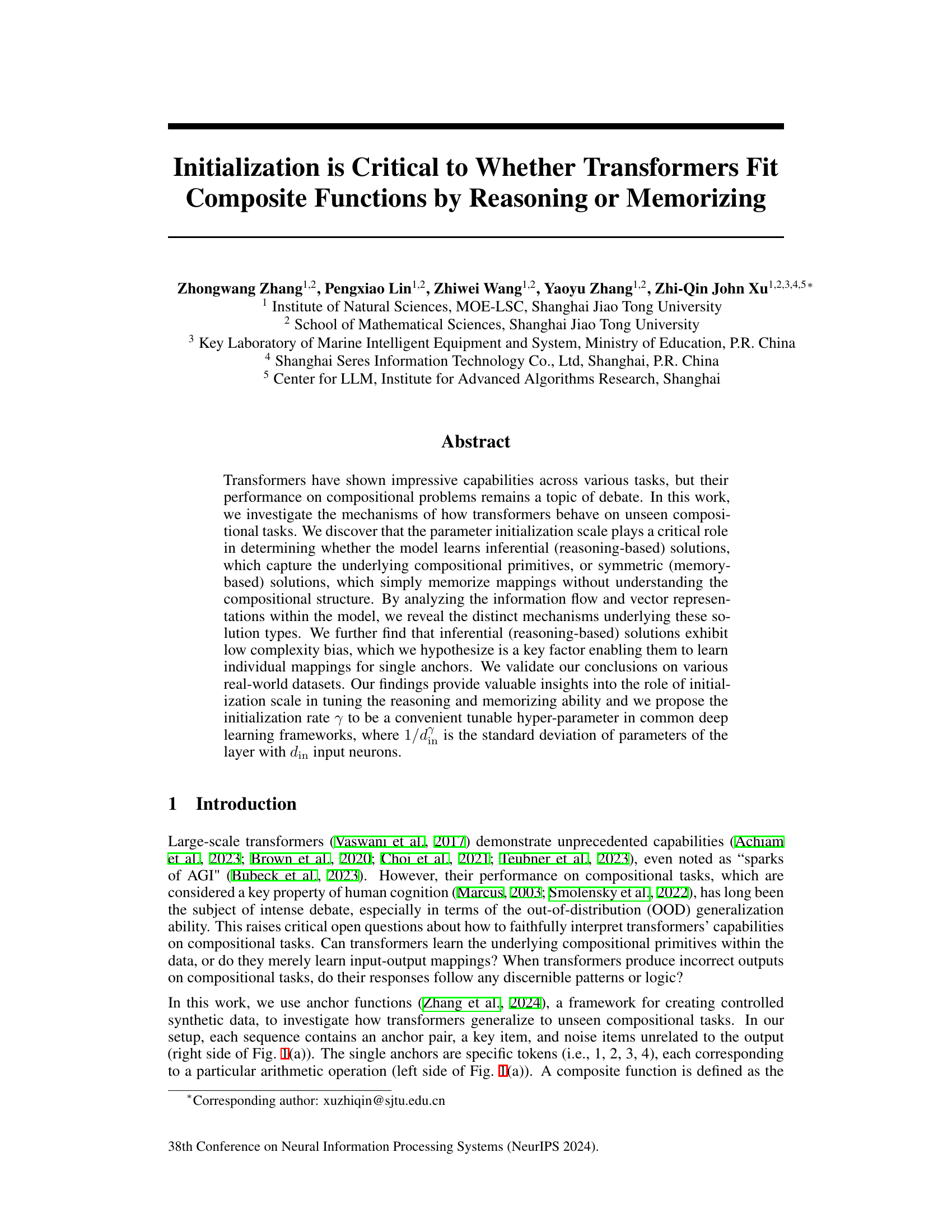

Visual Insights#

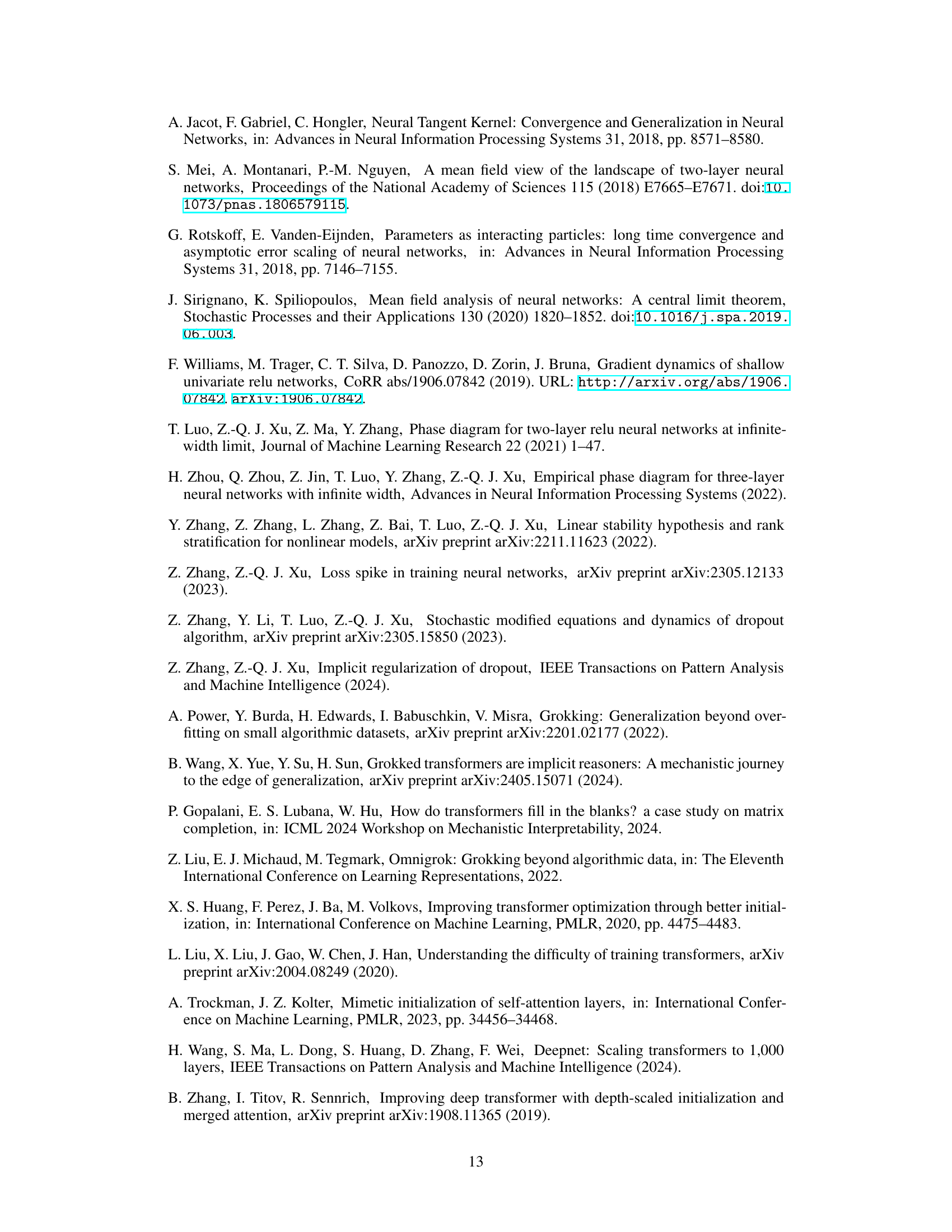

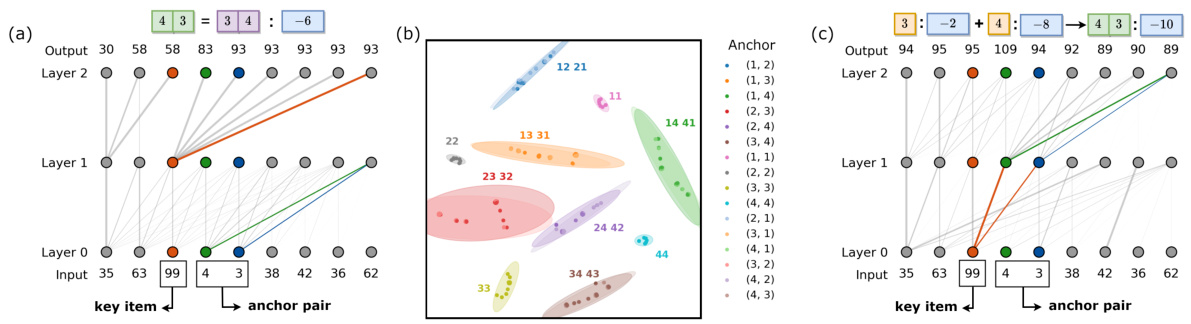

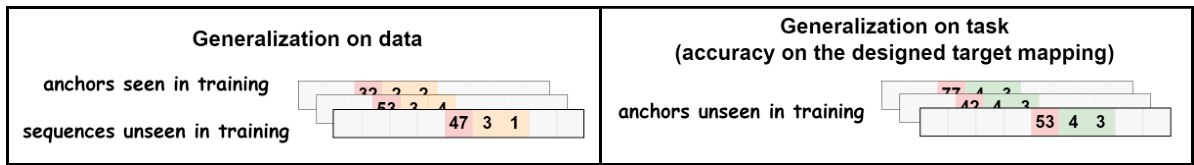

This figure illustrates the experimental setup and possible model behaviors for an unseen anchor pair. Part (a) details the data generation process, showing how single anchor functions are combined to create composite functions. Training data includes mostly inferential mappings (consistent with the composite function) with one non-inferential mapping. A single unseen anchor pair’s output will determine whether the model reasoned or memorized. Part (b) shows two possible mechanisms: Mechanism 1 (memorization) creates a symmetric solution based on the non-inferential example; Mechanism 2 (reasoning) composes solutions from the learned individual single anchor mappings.

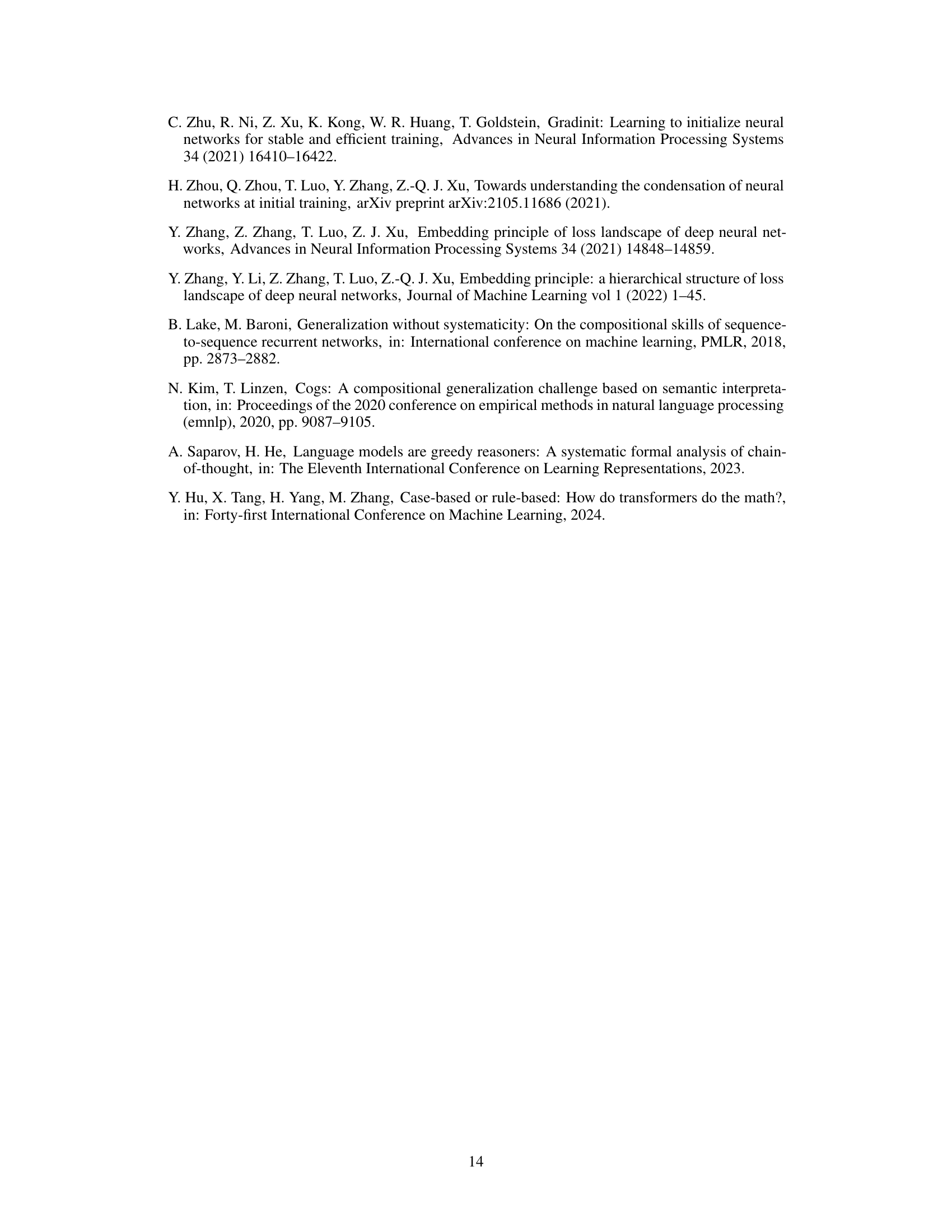

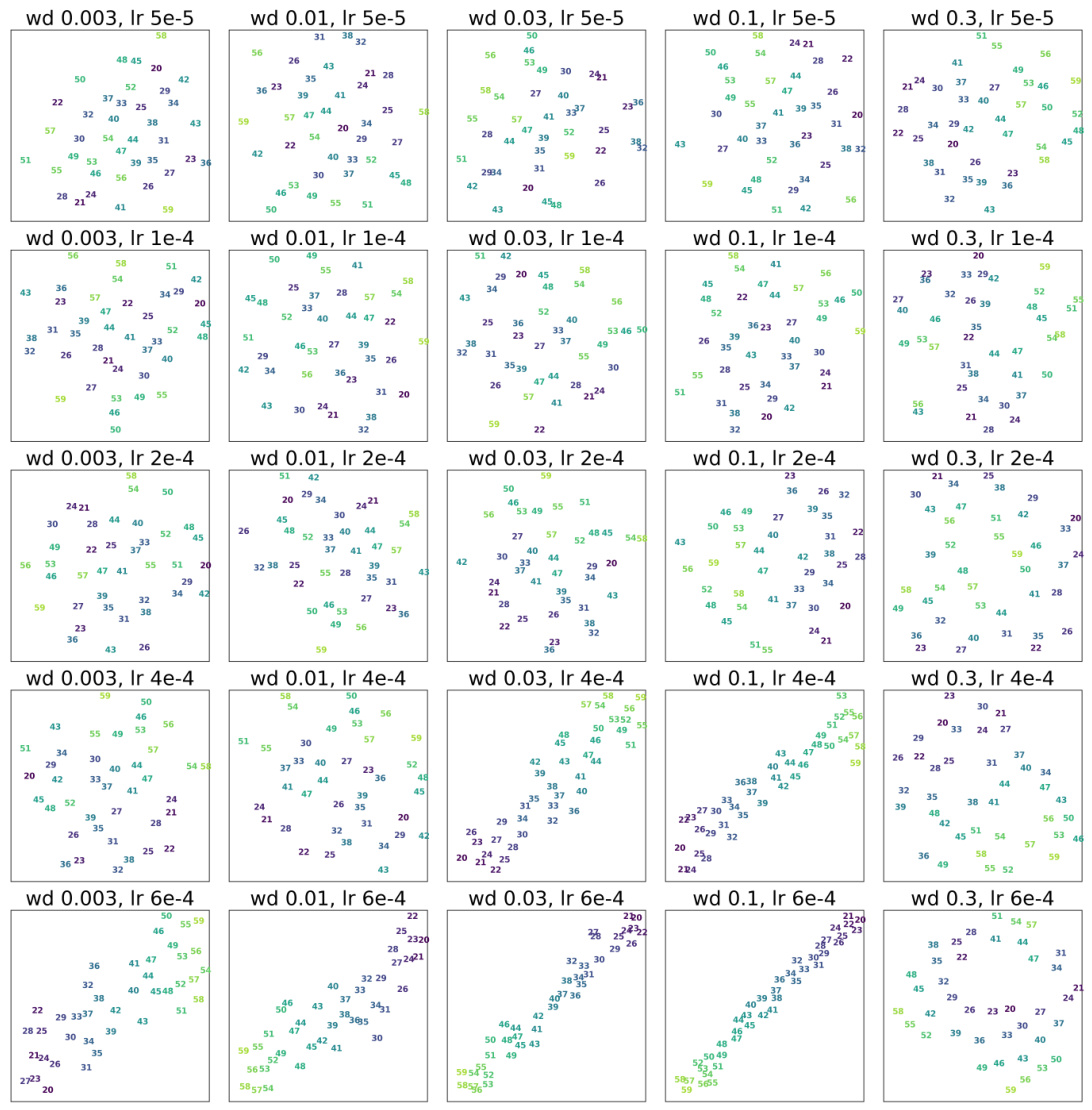

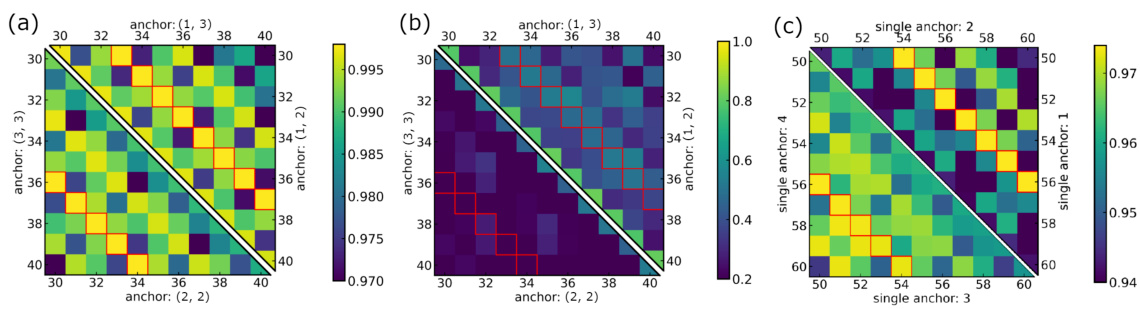

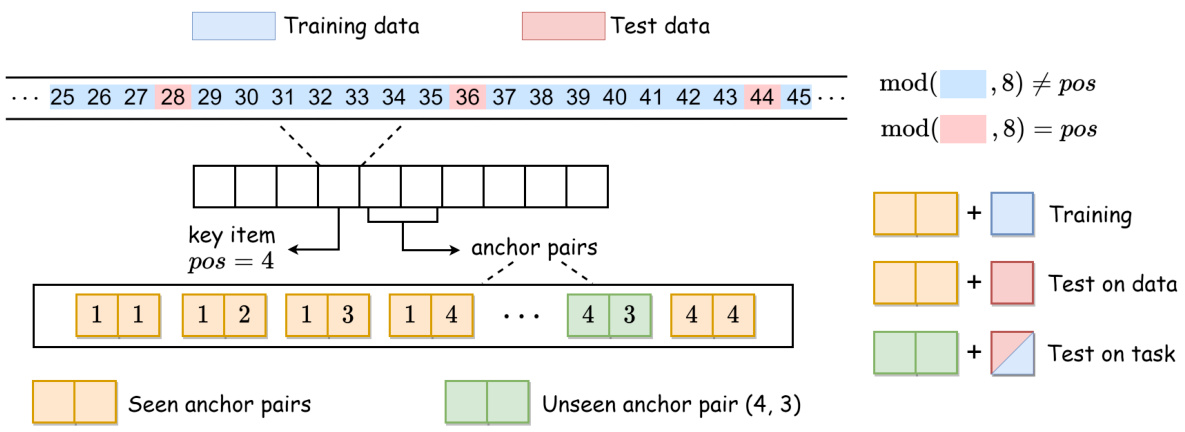

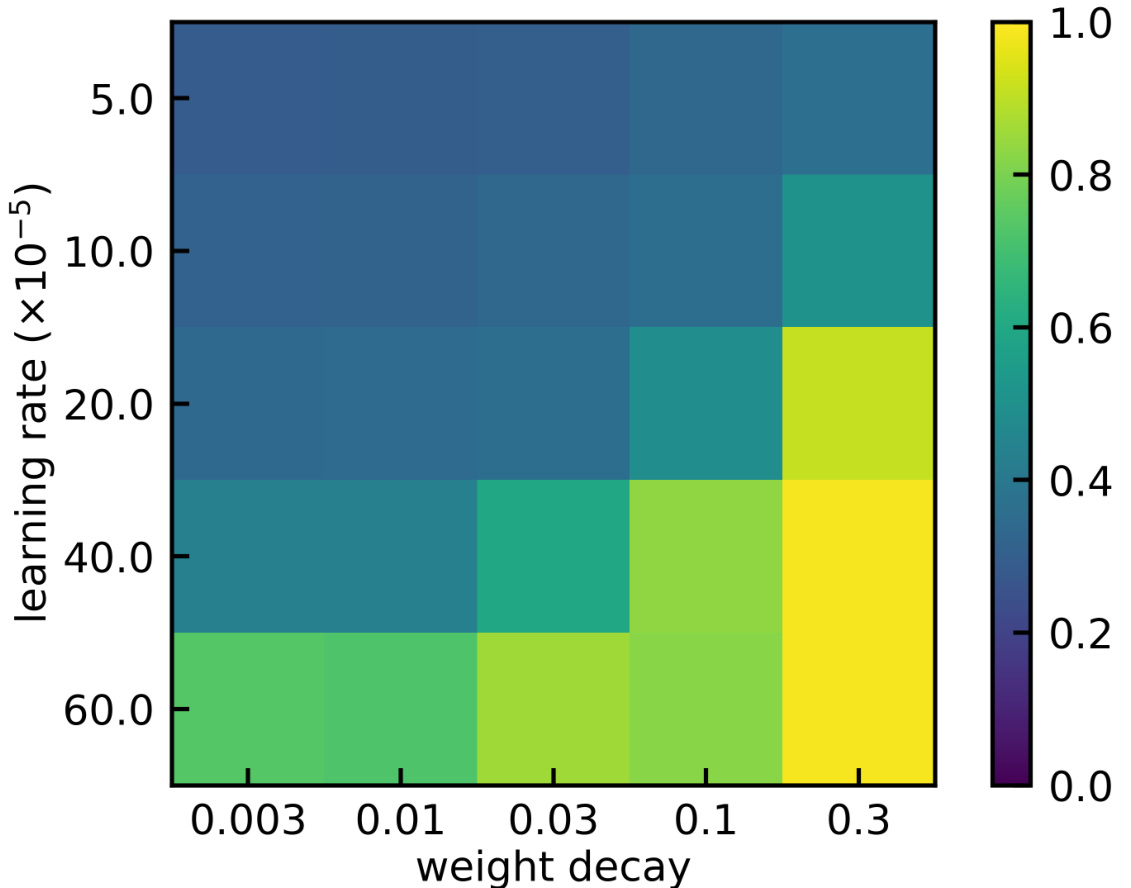

This table in the paper shows the cosine similarity matrices of the WQ(1) neurons at different learning rates and weight decay coefficients. The heatmaps visualize the parameter condensation. Warmer colors indicate higher similarity, and neurons with cosine similarity greater than 0.7 are grouped together to highlight the condensation effect. This is used to analyze the model complexity at different hyperparameter settings.

In-depth insights#

Init Scale’s Impact#

The research paper explores the profound impact of parameter initialization scale on the learning mechanisms of transformers, particularly concerning their ability to solve compositional tasks. Small initialization scales promote the development of inferential, reasoning-based solutions, where the model learns to decompose complex tasks into simpler sub-tasks, showcasing a better understanding of underlying compositional structures. In contrast, large initialization scales encourage memorization, leading to symmetric solutions. These solutions lack genuine understanding and rely on simply mapping inputs to outputs without grasping the underlying logic. This difference is not merely about the solutions produced, but it stems from fundamental differences in how information flows and is represented within the model. Small scales lead to lower complexity, enabling efficient learning of individual mappings for sub-tasks and their composition. Large scales result in higher complexity, making the model prone to memorizing specific input-output pairs, thus hindering generalization to unseen compositional tasks. The parameter initialization scale, therefore, emerges as a crucial hyperparameter to tune, offering a powerful mechanism to steer transformer models towards either reasoning or memorization behavior, with significant implications for model performance and generalization.

Reasoning vs. Memo#

The core of this research lies in understanding how transformers handle compositional tasks, specifically examining the dichotomy between reasoning and memorization. The authors posit that parameter initialization plays a crucial role in determining whether a transformer solves a problem through genuine reasoning or rote memorization. Small initialization scales promote inferential, reasoning-based solutions, where the model learns underlying compositional primitives. Conversely, large initialization scales lead to symmetric, memory-based solutions, where the model essentially memorizes input-output mappings without a true understanding of the underlying structure. This distinction is not merely an observation but is deeply rooted in the model’s information processing mechanisms, including attention flow and vector representations, which reveal distinct patterns for each solution type. The model’s complexity, heavily influenced by initialization scale, acts as a key factor in this paradigm shift: low complexity favoring reasoning and high complexity fostering memorization. This work has important implications for understanding transformer capabilities and for guiding hyperparameter optimization strategies to enhance specific cognitive abilities of large language models.

Model Complexity#

The concept of ‘Model Complexity’ in the context of transformer model behavior on compositional tasks is crucial. The paper suggests that initialization scale directly influences model complexity, leading to a dichotomy in solution strategies. Small initialization scales foster lower complexity, allowing the model to learn individual mappings for single anchors through reasoning, a more efficient process. This contrasts with large initialization scales, which result in higher complexity, leading to memorization-based solutions and a tendency towards symmetry. The analysis of information flow and vector representations further supports this. Inferential solutions exhibit low complexity, as indicated by weight condensation and orderly arrangements in embedding space. Conversely, symmetric solutions exhibit no such clear structure, reflecting their higher complexity. The interplay between complexity and the capacity for reasoning versus memorization is a key insight, highlighting the importance of initialization scale as a tunable hyperparameter to control model behavior for various tasks.

Real-world Tasks#

In evaluating the real-world applicability of their findings on the impact of parameter initialization on transformer model behavior, the authors should conduct a thorough investigation of diverse real-world tasks. This would involve applying their models to various established benchmarks or datasets, spanning different domains and complexities, to verify whether the observed trends of reasoning versus memorization based on initialization persist. A focus on tasks requiring complex compositionality and robust generalization is key. Selecting tasks that are representative of real-world challenges and avoid artificial constructs is vital for validating the practical implications of their work. The analysis should also explore whether the choice of initialization strategy needs to be tailored to the specifics of the task domain and whether certain task characteristics might favor one type of solution (reasoning or memorization) over another. Careful attention should be paid to the potential limitations of the real-world datasets used, acknowledging factors like noise, biases and ambiguity, which might affect the performance of the models and confound the conclusions. Furthermore, the investigation should look into whether the established relationship between initialization and model behavior scales effectively across different model architectures and sizes. The overall goal is to provide compelling empirical evidence that demonstrates the generalizability and practical significance of the findings beyond the controlled experiments presented in the paper.

Future Work#

The authors acknowledge the limitations of their current work, primarily relying on synthetic data, and propose several crucial avenues for future research. Extending the research to real-world datasets and tasks is paramount, bridging the gap between theoretical understanding and practical applications. This necessitates exploring various real-world scenarios to validate the findings’ generalizability. Investigating the impact of different model architectures beyond the single-head and multi-head models studied is another critical direction. Different architectural choices could significantly influence the model’s ability to learn compositional structures or rely on memorization. The exploration of different training methods and hyperparameter optimization techniques is essential for furthering our understanding of the initialization’s role. Analyzing the interaction between initialization strategies and other training aspects could yield further insights. Finally, adapting initialization schemes to specific task types presents a promising area for investigation; larger initialization scales may be suited for memorization-heavy tasks, whereas smaller scales could be advantageous for reasoning-intensive tasks. This research holds immense potential in better leveraging transformers’ capabilities across diverse domains.

More visual insights#

More on figures

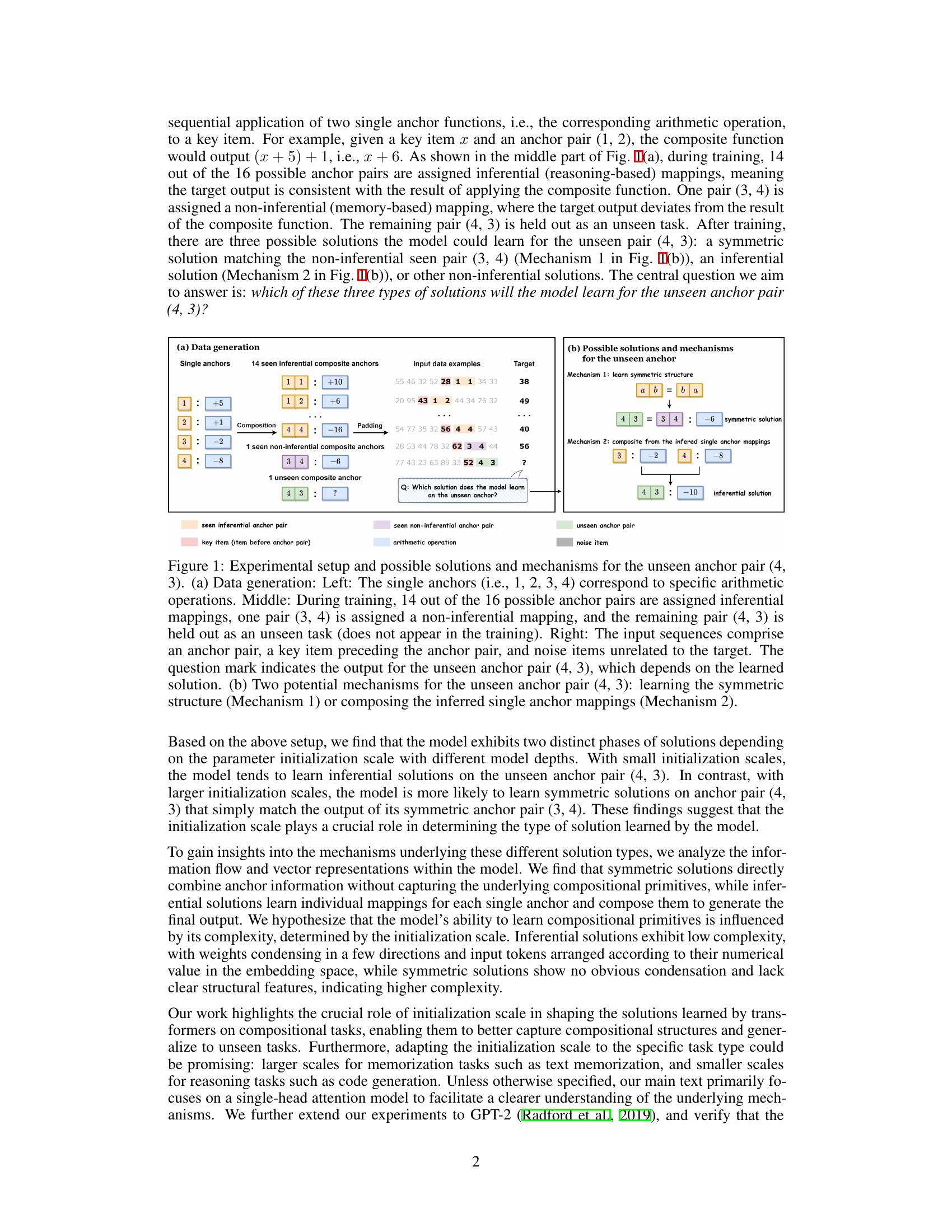

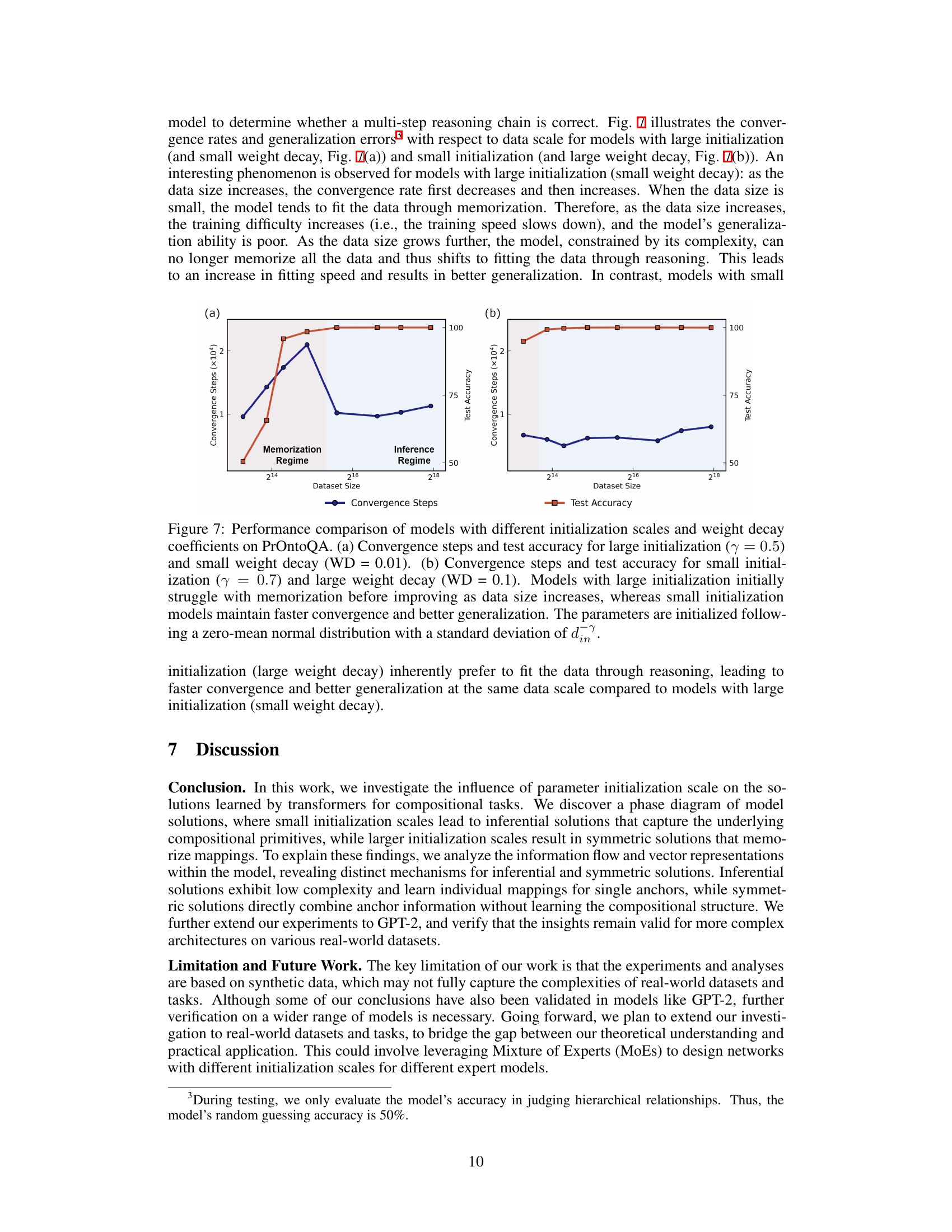

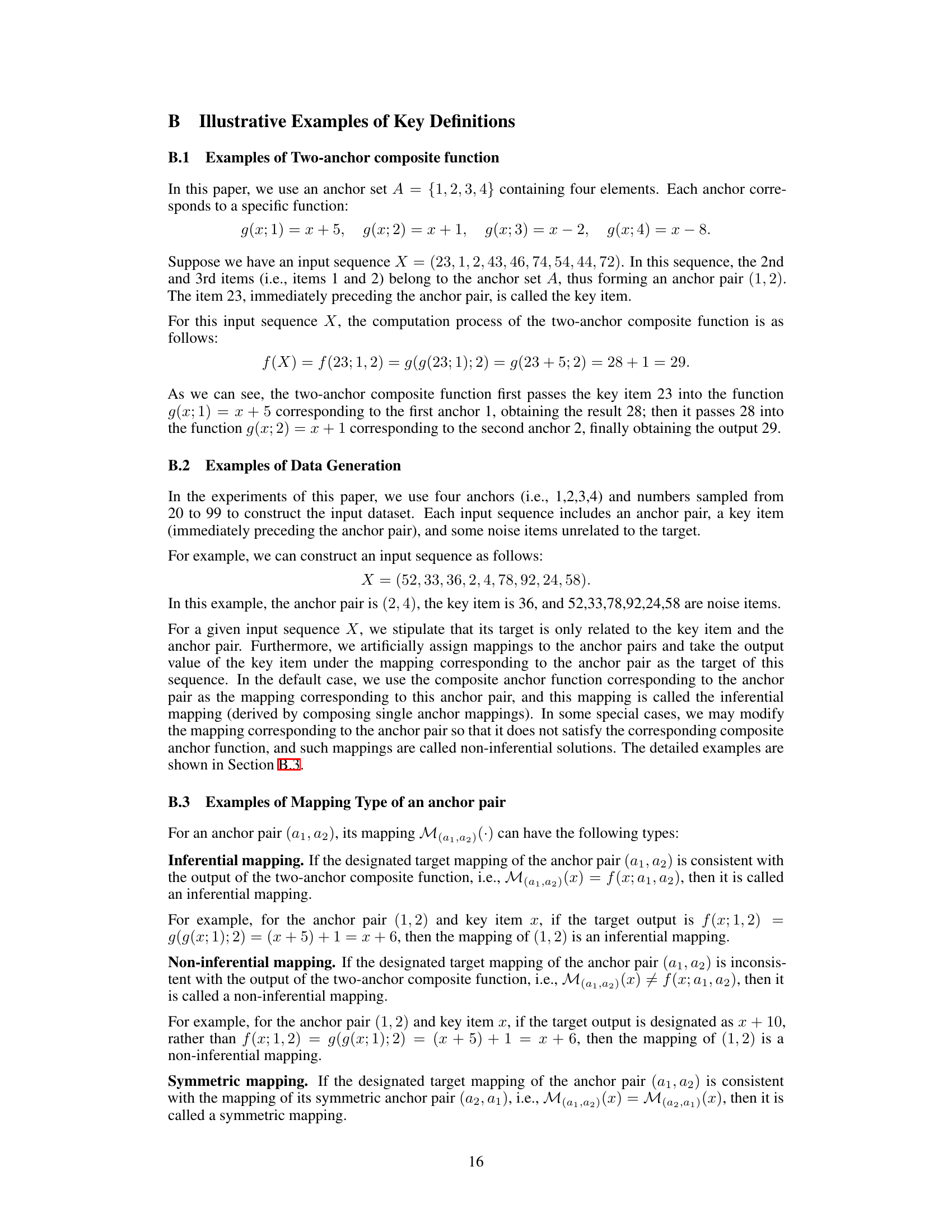

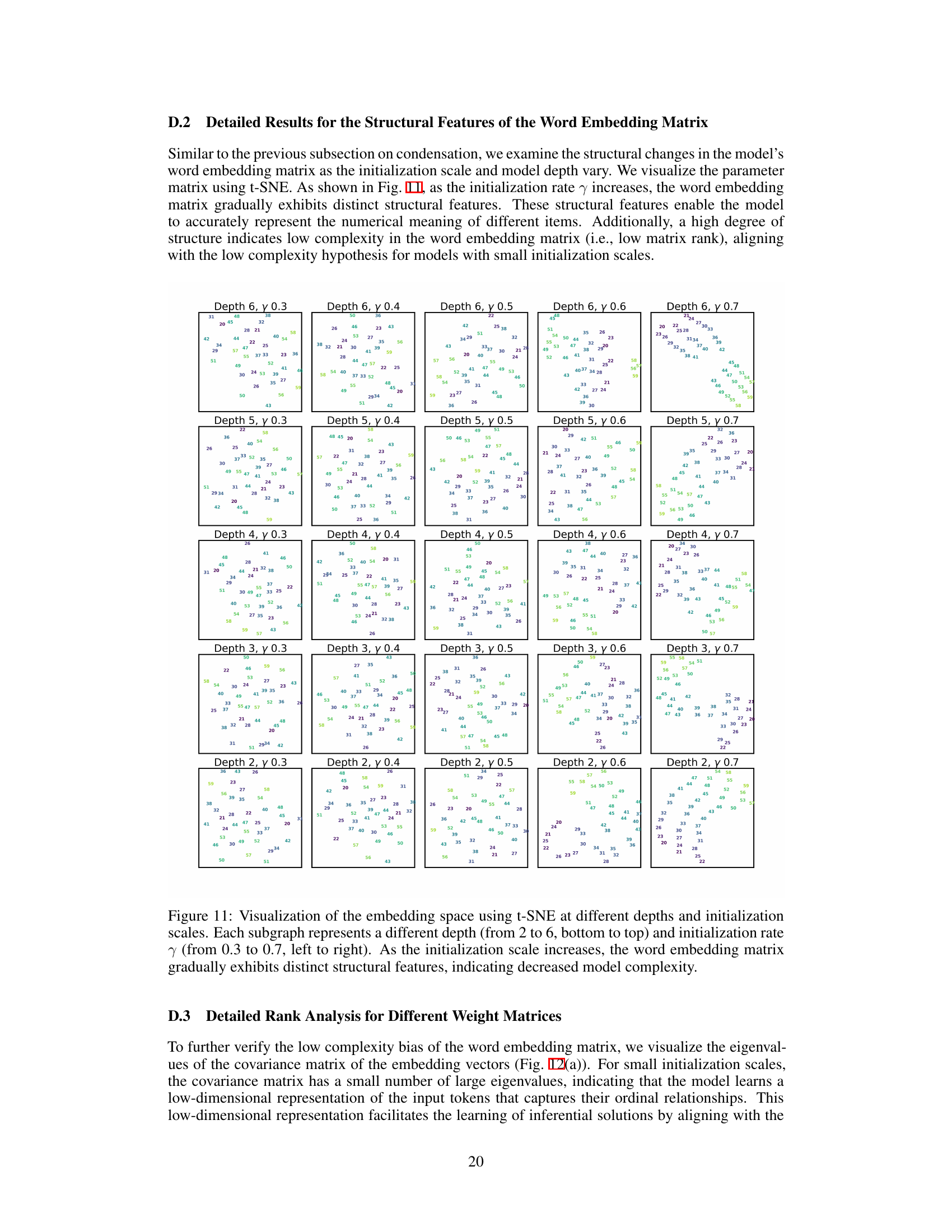

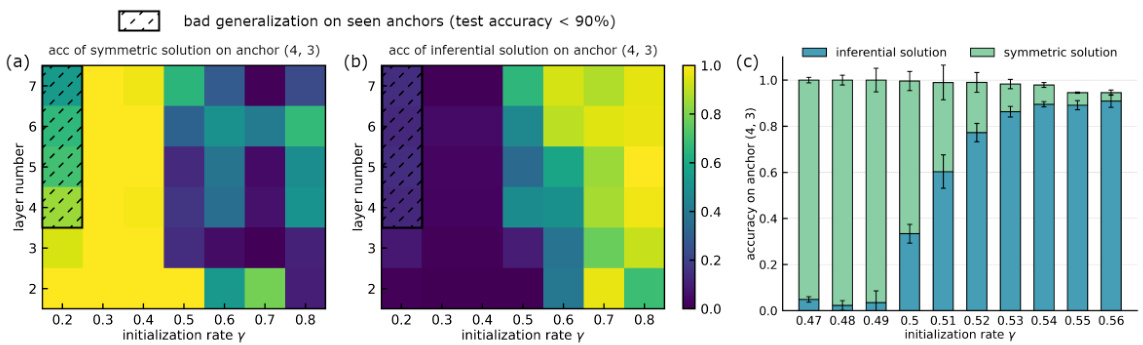

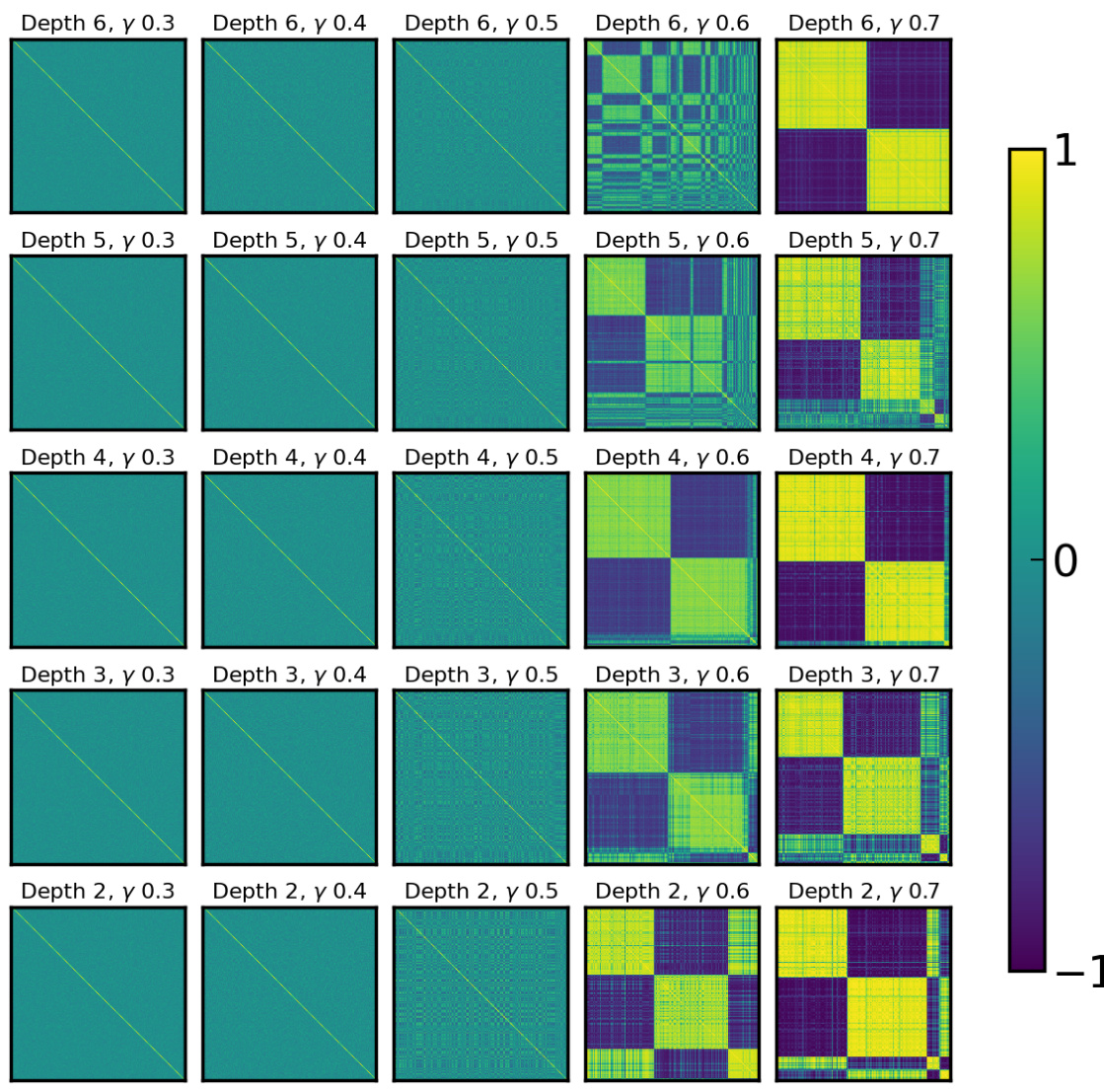

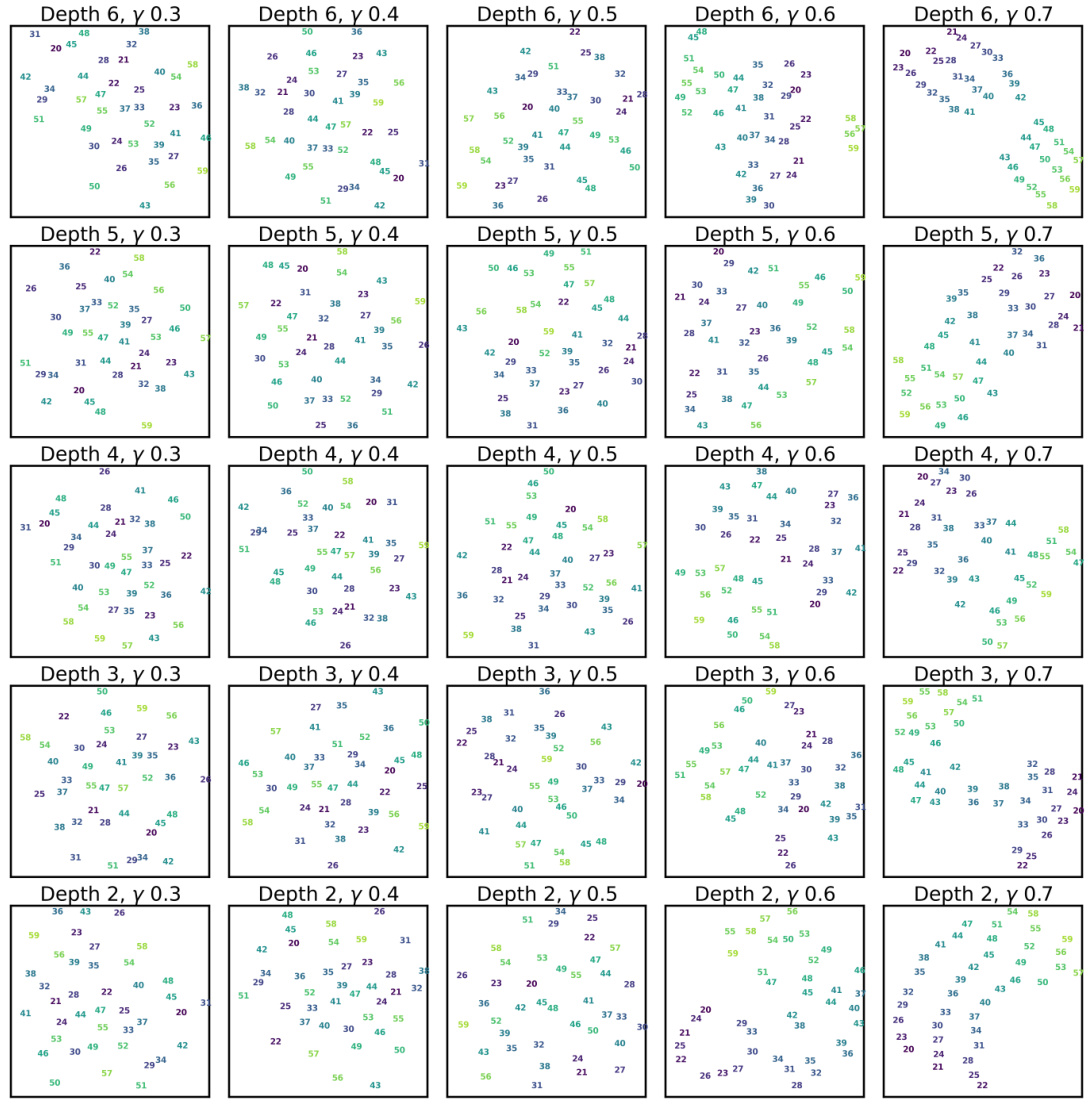

This figure shows a phase diagram illustrating the relationship between model depth, initialization rate (γ), and the accuracy of inferential and symmetric solutions on an unseen anchor pair (4,3). The shadow areas highlight regions where the model performs poorly on seen anchor pairs. A separate panel shows a comparison of these solutions across various initialization rates using the GPT-2 model, indicating a similar trend.

This figure visualizes the information flow in two-layer neural networks for both symmetric and inferential solutions, illustrating how information is transmitted and fused through the attention mechanism. It also includes a t-SNE visualization of the vector representations, showing how symmetric anchor pairs are clustered together in the vector space.

This figure shows heatmaps visualizing cosine similarity between output vectors (last token of the second attention layer) for different anchor-key item pairs, comparing inferential and symmetric solutions. Red boxes highlight instances where inferential targets are identical. The subfigure (c) focuses on the cosine similarity within the Value matrix (V(2)) for inferential solutions, relating to individual anchor mappings.

This figure visualizes the information flow and vector representations in two-layer transformer networks for symmetric and inferential solutions. Panel (a) and (c) show the information flow through the attention mechanism for each solution type, highlighting how information from key items and anchors combines to produce the output. Panel (b) uses t-SNE to visualize the vector representations of the model’s output after the first attention layer, demonstrating that symmetric solutions cluster similar anchor pairs together.

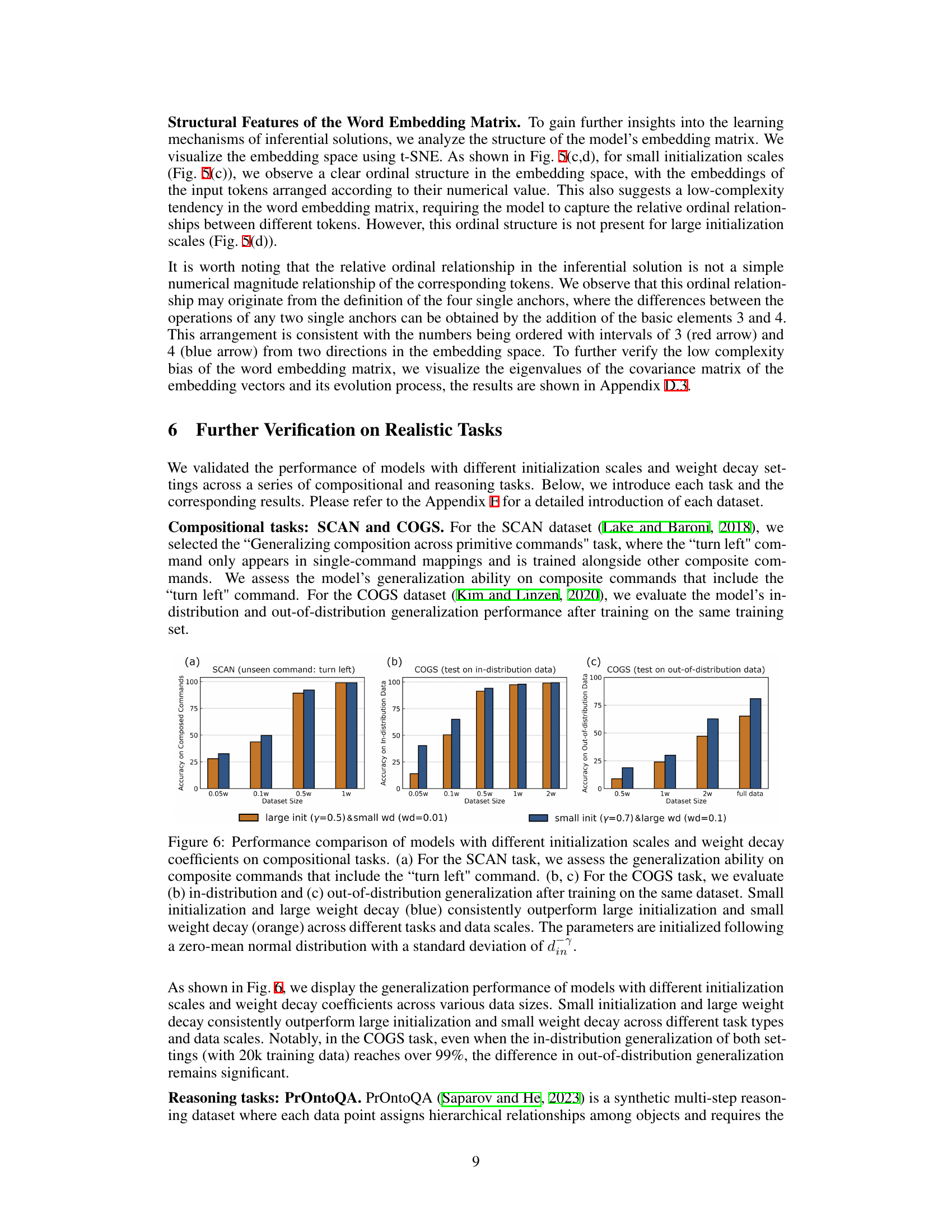

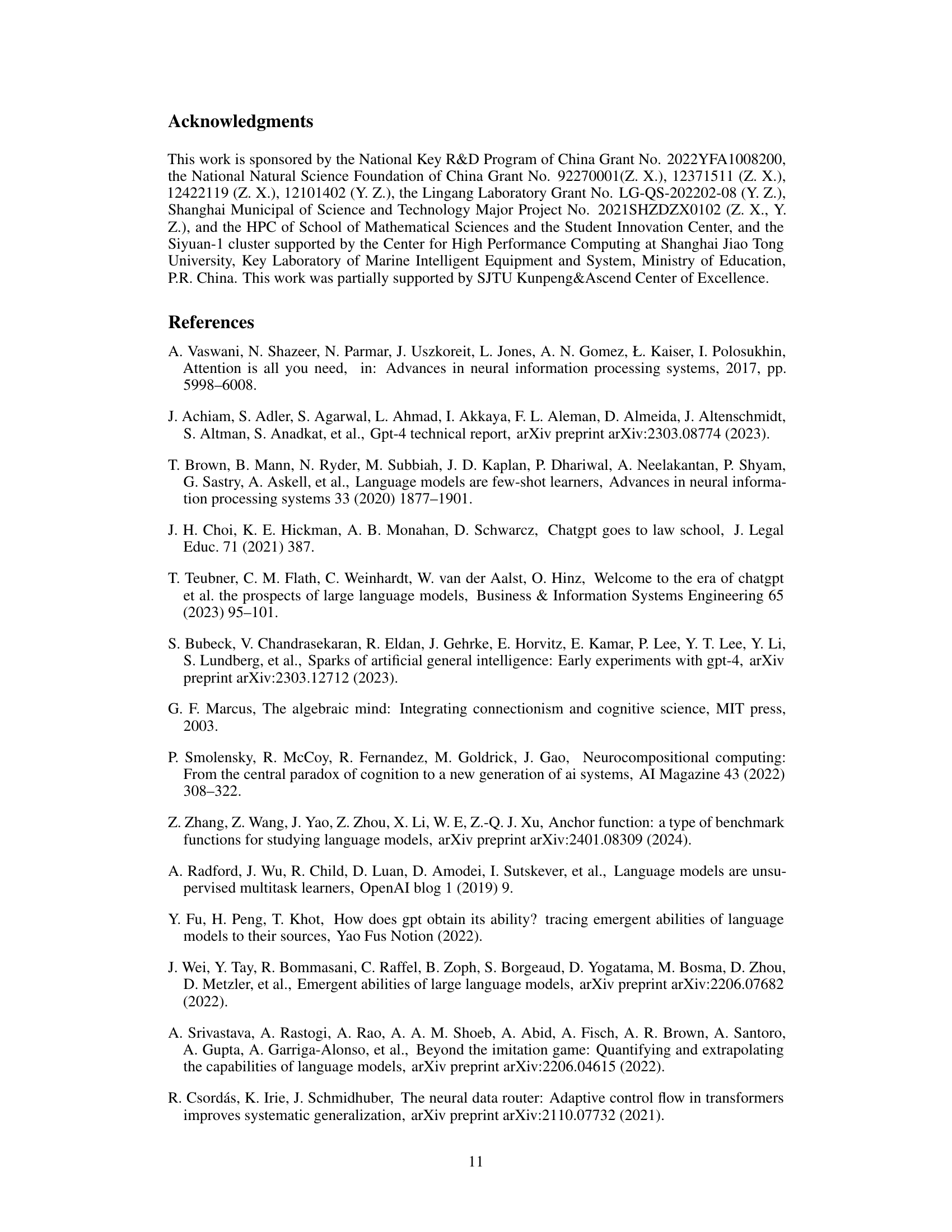

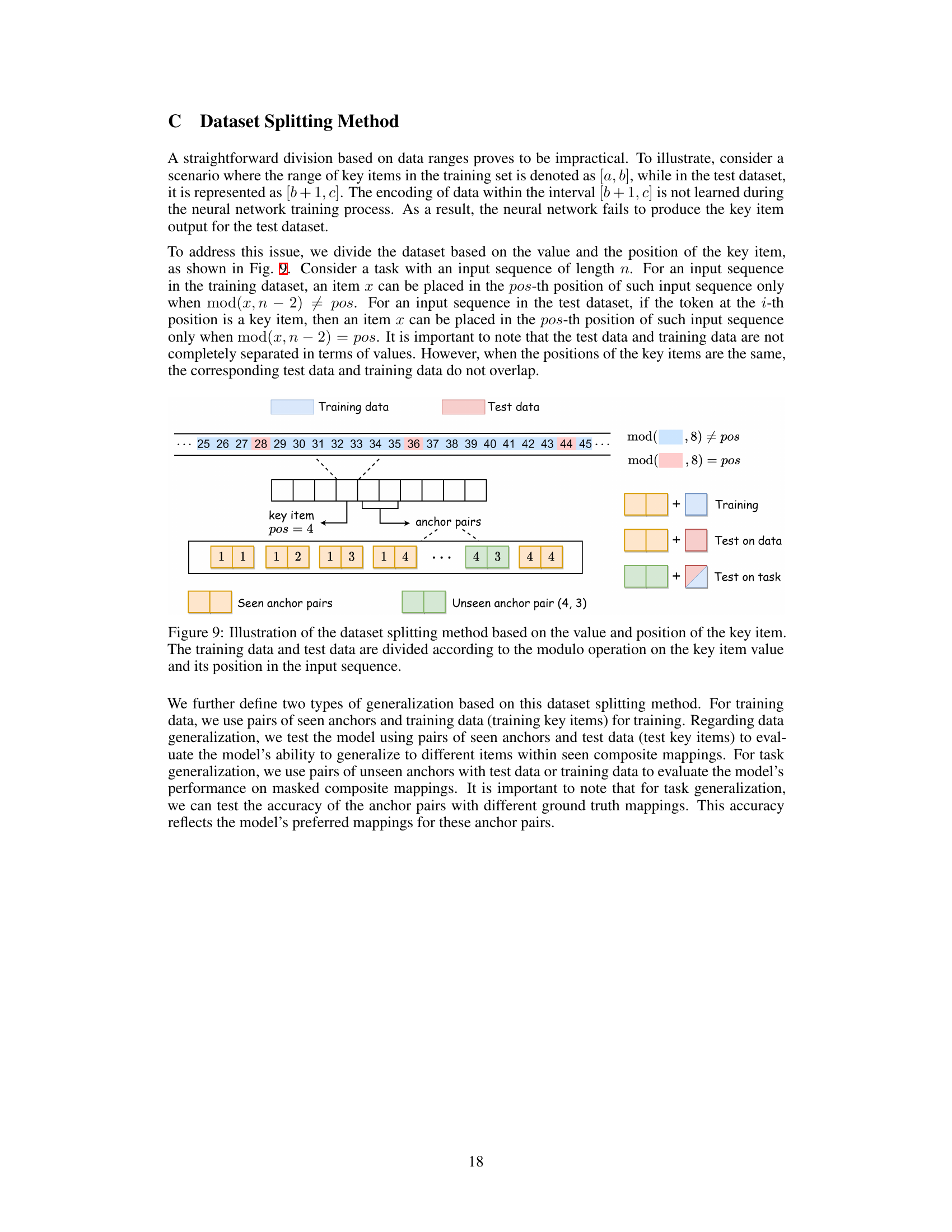

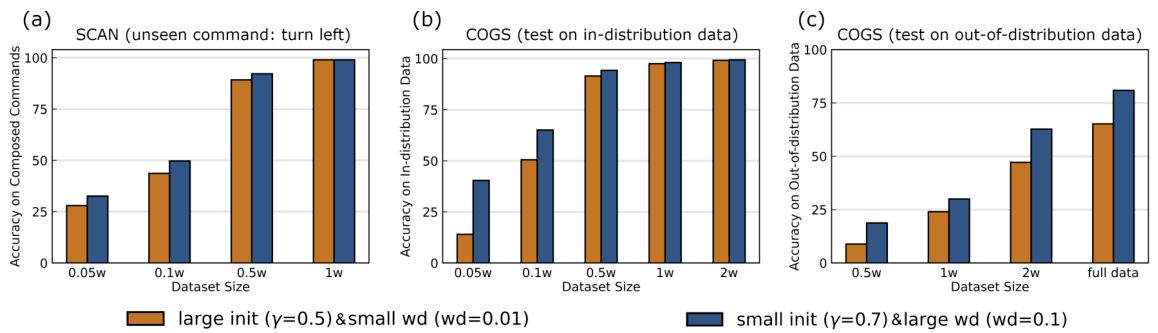

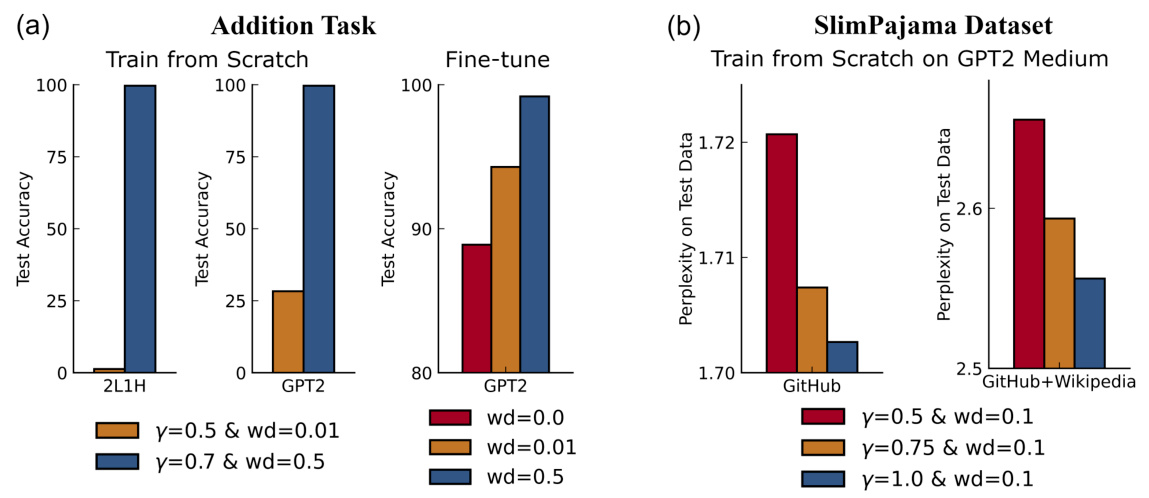

The figure shows the performance comparison of models with different initialization scales and weight decay coefficients on three compositional tasks: SCAN (unseen command: turn left), COGS (in-distribution data), and COGS (out-of-distribution data). The results demonstrate that models with smaller initialization scales and larger weight decay consistently outperform models with larger initialization scales and smaller weight decay across different tasks and dataset sizes, showcasing their superior generalization abilities.

This figure shows a phase diagram illustrating the relationship between model depth, initialization rate (γ), and the model’s ability to generalize to unseen compositional tasks. The diagram is separated into sections demonstrating performance based on either a symmetric or inferential solution. Shadowed regions highlight instances where the model’s performance on seen anchors drops below 90% accuracy. A final subplot compares results from GPT-2 across different initialization rates.

This figure shows a phase diagram of the model’s generalization performance on an unseen anchor pair (4,3) based on whether it learns a symmetric or inferential solution. The diagram is split into two subplots, one for each solution type. Initialization rate (γ) is plotted on the x-axis, and model depth on the y-axis. Test accuracy is represented on the graphs’ z-axis, with shaded regions indicating when test accuracy on seen anchor pairs is below 90%. A third subplot shows a comparison of the accuracy of both solution types on a GPT-2 model. This figure helps to demonstrate the impact of initialization scale on the type of solution learned by the model.

This figure illustrates the experimental setup and possible solutions for an unseen anchor pair in a compositional task. It shows how synthetic data is generated using anchor pairs (representing arithmetic operations) and key items. The training data includes 14 inferential (reasoning-based) mappings, one non-inferential (memory-based) mapping, and one unseen anchor pair. The figure then illustrates two possible mechanisms the model might employ to solve the unseen pair: either learning a symmetric structure based on the seen non-inferential pair, or composing mappings learned from individual anchors.

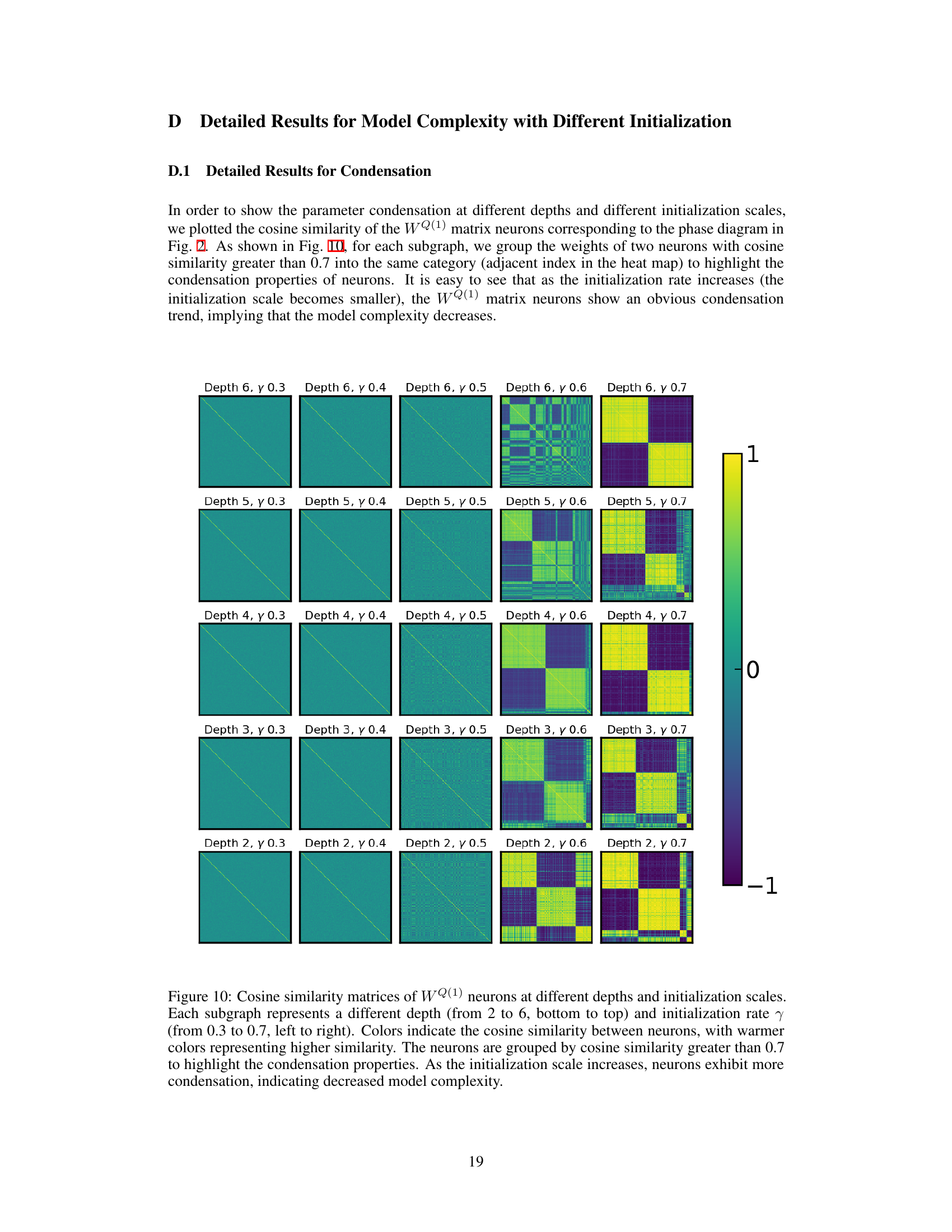

This figure visualizes the cosine similarity matrices of the input weights (WQ(1)) in the first attention layer of a transformer model. It shows how the weight matrices change with varying model depths (2-6 layers) and initialization rates (γ = 0.3 to 0.7). Warmer colors represent higher cosine similarity between neurons, indicating condensation or clustering of weights. The figure demonstrates that as the initialization scale increases (γ values get smaller), there is more condensation, resulting in lower model complexity.

This figure shows a phase diagram illustrating the relationship between initialization rate, model depth, and the model’s ability to learn either symmetric or inferential solutions for an unseen compositional task. The diagram highlights two distinct phases of solutions based on the initialization scale, with smaller scales favoring inferential solutions and larger scales favoring symmetric solutions. The shadow regions indicate poor generalization on seen data points. A supplementary graph shows a similar relationship on a larger, more complex model (GPT-2).

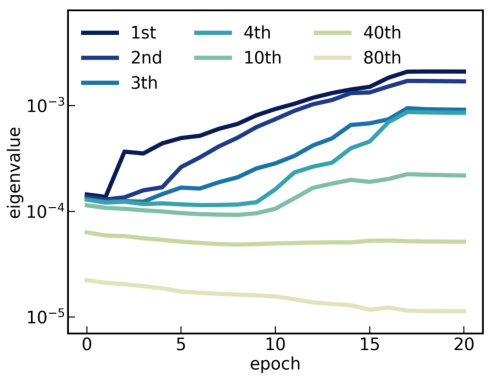

This figure shows the eigenvalues of the covariance matrix of the word embedding matrix for different initialization scales (γ=0.5 and γ=0.8). The left panel shows the eigenvalues at the end of training, while the right panel shows how the eigenvalues evolve during training for the smaller initialization scale (γ=0.5). The figure demonstrates how the initialization scale affects the model’s complexity, with smaller scales leading to lower complexity and more condensed eigenvalue distributions.

This figure shows the eigenvalues of the covariance matrix of the word embedding matrix for different initialization scales (left) and the evolution of eigenvalues during training for a model with small initialization (right). The left panel demonstrates how the eigenvalue distribution changes with different initialization scales, indicating a low-complexity trend for small initialization scales. The right panel shows how the eigenvalues evolve over epochs, suggesting a gradual increase in model complexity during training. These observations support the paper’s hypothesis about the relationship between initialization scale, model complexity, and solution type.

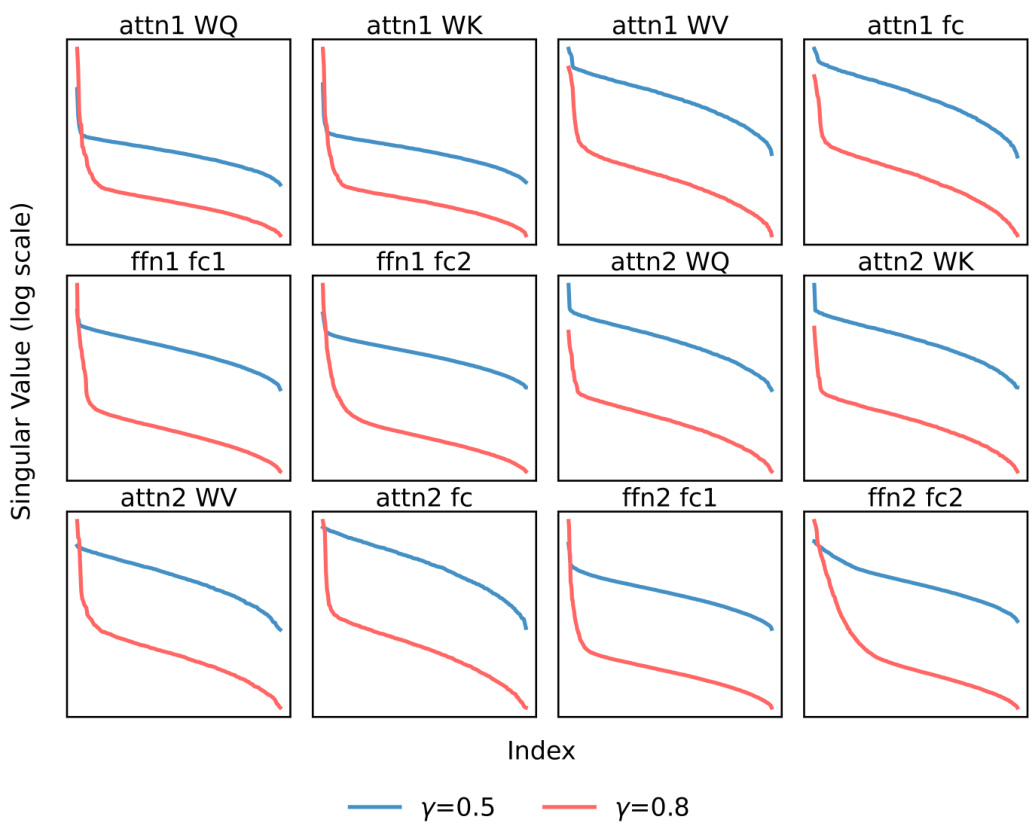

This figure displays singular value distributions for weight matrices across different linear layers in a transformer model, comparing models trained with small (γ=0.5) and large (γ=0.8) initialization scales. The plots show how the magnitude of singular values decreases with increasing index, illustrating the distribution’s concentration for the low-complexity model (small initialization). This visualization helps to analyze model complexity and its impact on solutions.

This heatmap visualizes how different learning rates and weight decay coefficients affect the accuracy of inferential solutions in a 3-layer, single-head transformer model. Higher accuracy (yellow) indicates better performance at learning inferential solutions for the unseen anchor pair (4,3).

This figure visualizes the cosine similarity matrices of the weight matrices (WQ(1)) of a transformer model’s first attention layer. It shows how the model’s complexity changes depending on the depth of the network and the initialization rate (γ). Warmer colors in the heatmaps represent higher cosine similarity between neurons, indicating condensation of weights. The figure demonstrates that as the initialization rate increases (smaller initialization scale), the neurons exhibit stronger condensation, leading to lower model complexity.

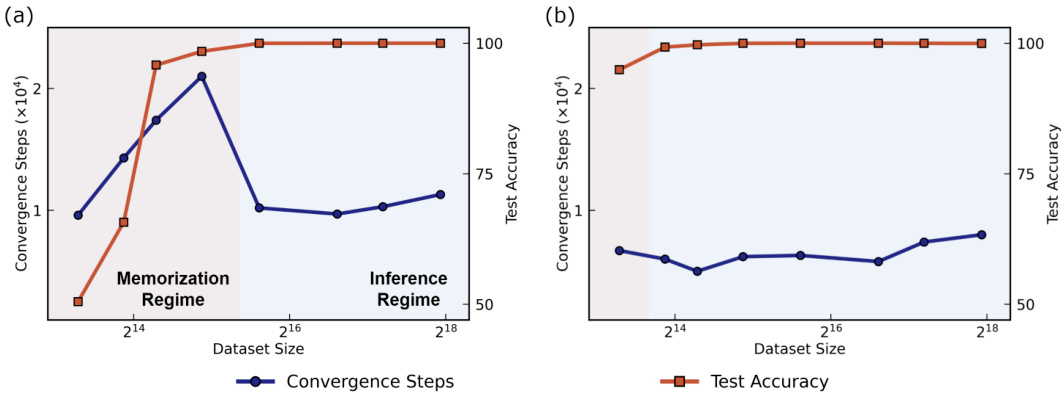

This figure shows the performance of the model on the unseen anchor pair (4,3) based on both symmetric and inferential mapping with various initialization rates and model depths. The shadow area indicates that the model’s performance is poor on seen anchor pairs. Subfigure (c) extends the experiment to the GPT-2 model.

Full paper#