↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly used in critical applications demanding strategic reasoning. However, current evaluation methods don’t sufficiently assess this aspect. This paper addresses this gap by introducing GTBENCH, a benchmark comprising 10 diverse game-theoretic tasks. These tasks cover various scenarios, including complete/incomplete information, dynamic/static, and deterministic/probabilistic settings, allowing for comprehensive evaluation of LLM reasoning abilities. The study highlights the need for more rigorous evaluation of LLMs in complex, strategic reasoning tasks.

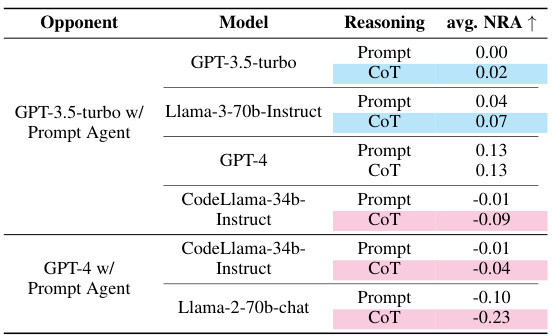

The research uses GTBENCH to evaluate several LLMs, comparing open-source and commercial models. It finds that LLMs exhibit varying performance across different game types, excelling in probabilistic games but struggling in deterministic ones. Code-pretraining is shown to benefit strategic reasoning, while advanced methods like Chain-of-Thought don’t always improve performance. The detailed error analysis provided helps understand LLMs’ limitations. This work establishes a standardized approach to assessing strategic reasoning in LLMs, furthering future research and development in the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with LLMs because it introduces a novel benchmark, GTBENCH, for evaluating strategic reasoning abilities. It reveals significant limitations in current LLMs, particularly in deterministic games, and highlights the benefits of code-pretraining. This opens avenues for improving LLM reasoning and developing more robust AI systems.

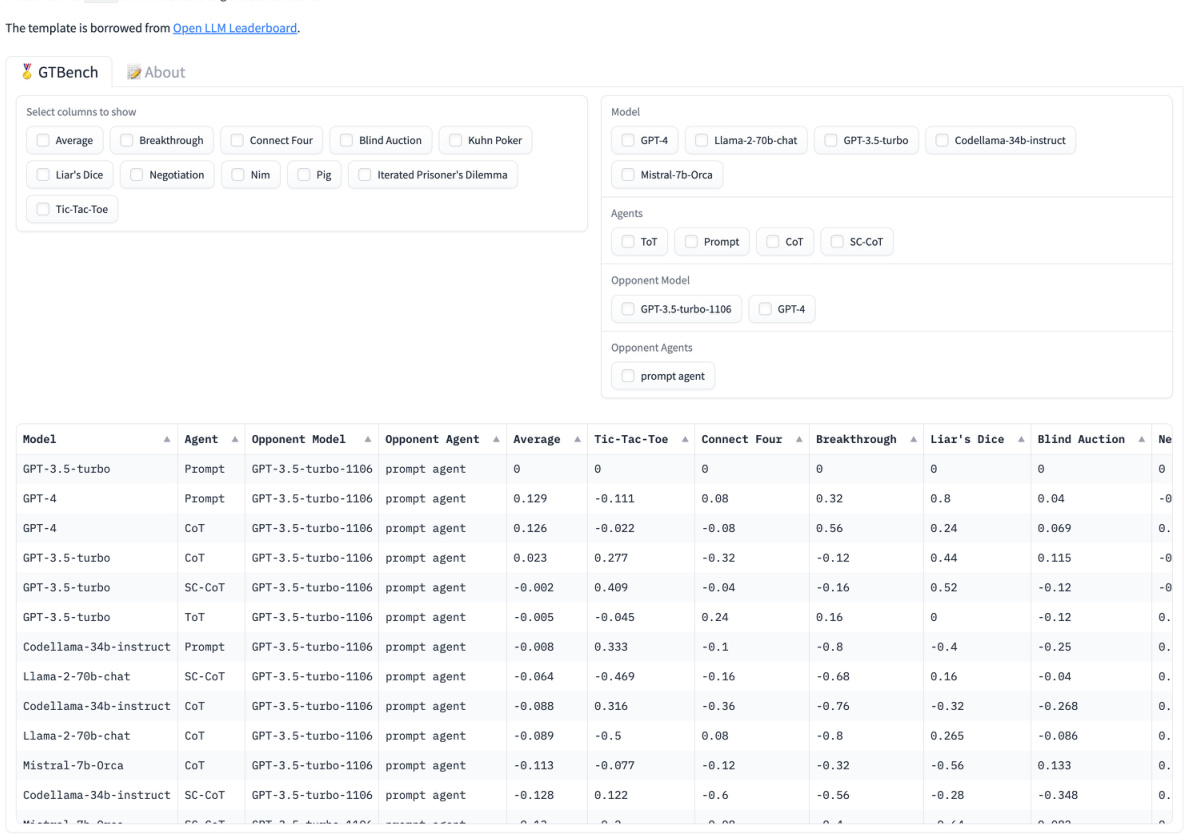

Visual Insights#

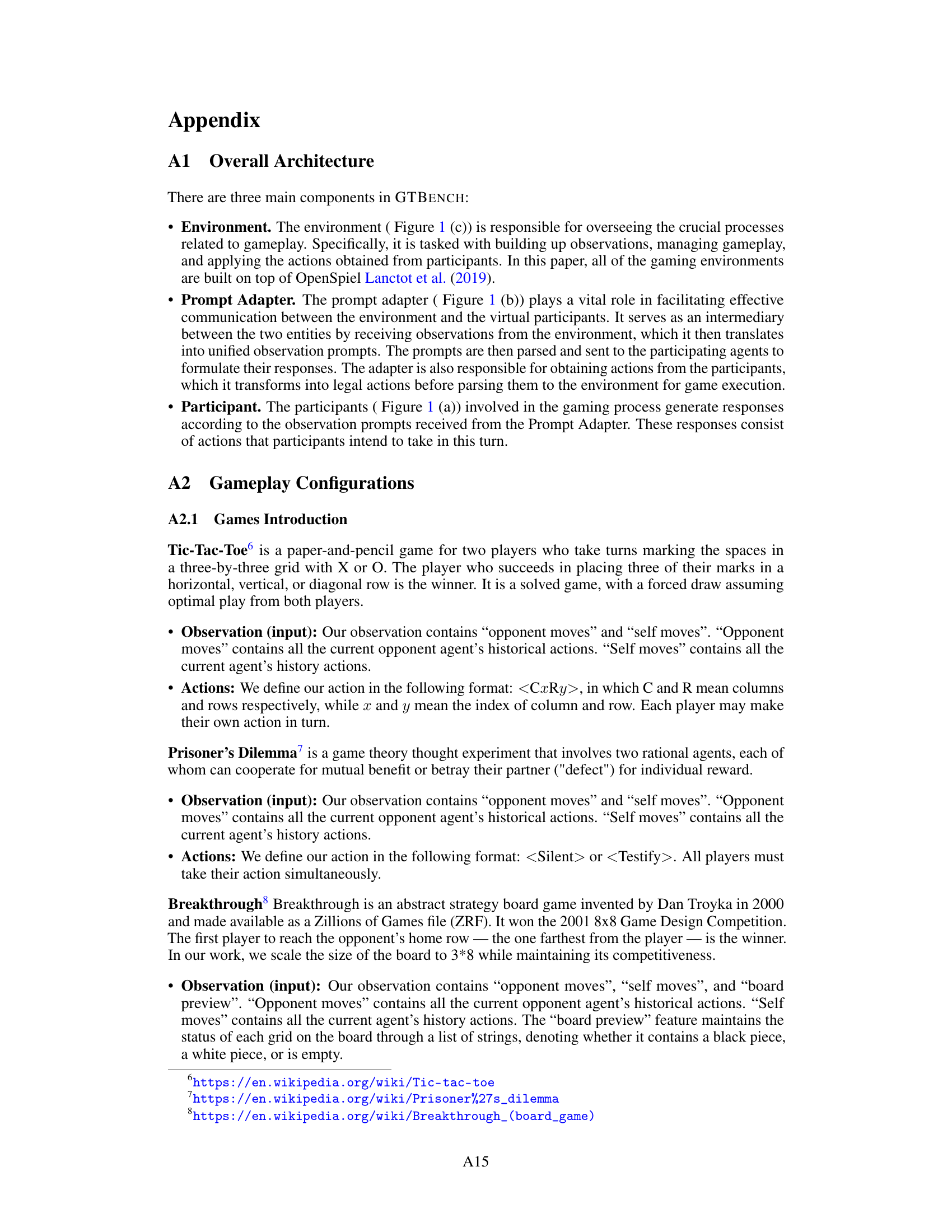

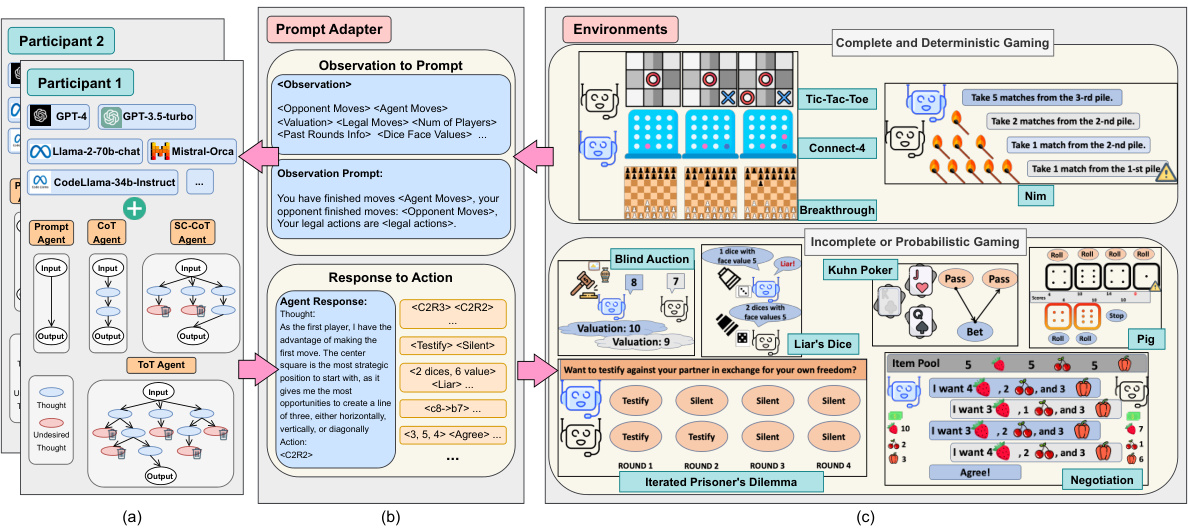

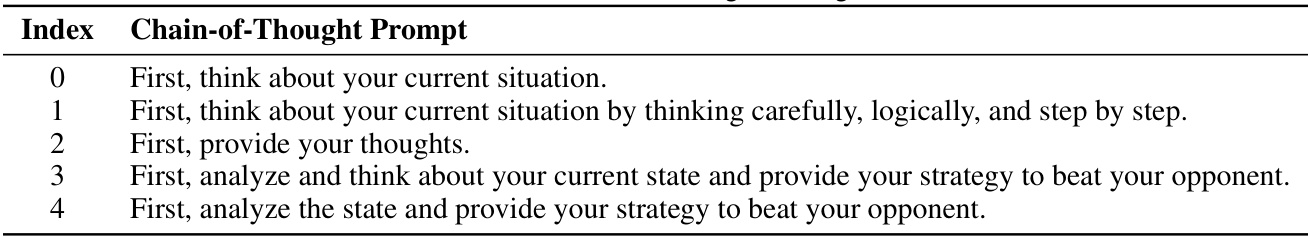

This figure shows the overall architecture of GTBENCH, a game-theoretic evaluation environment for LLMs. It highlights three main components: Participants (LLMs and other agents), Prompt Adapter (responsible for converting observations into prompts and actions), and Environments (the game environments themselves). The figure visually depicts the flow of information and actions between these components, illustrating the process of LLMs participating in and responding to game-theoretic tasks. The diagram also categorizes the games included in GTBENCH into complete/deterministic and incomplete/probabilistic categories, and provides example games for each category.

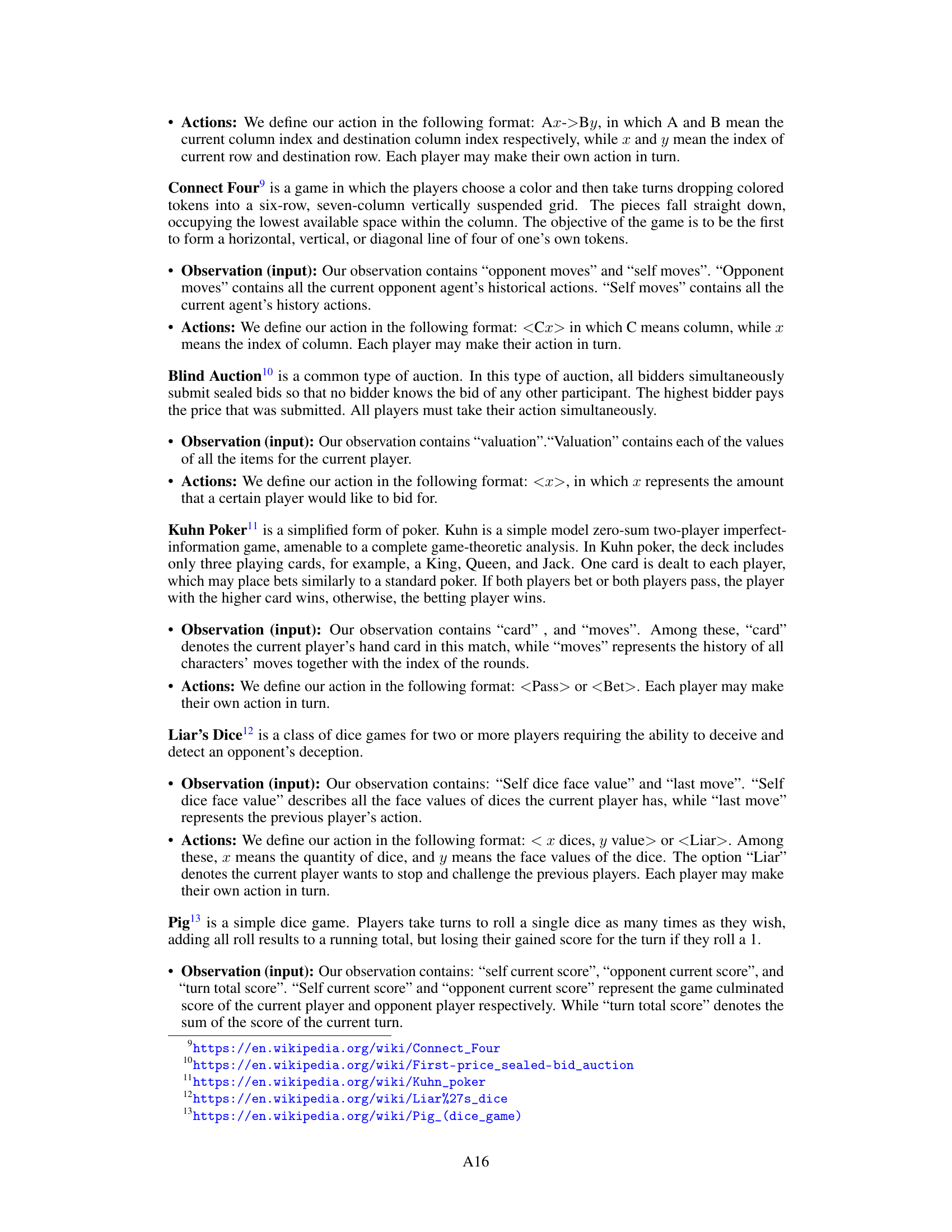

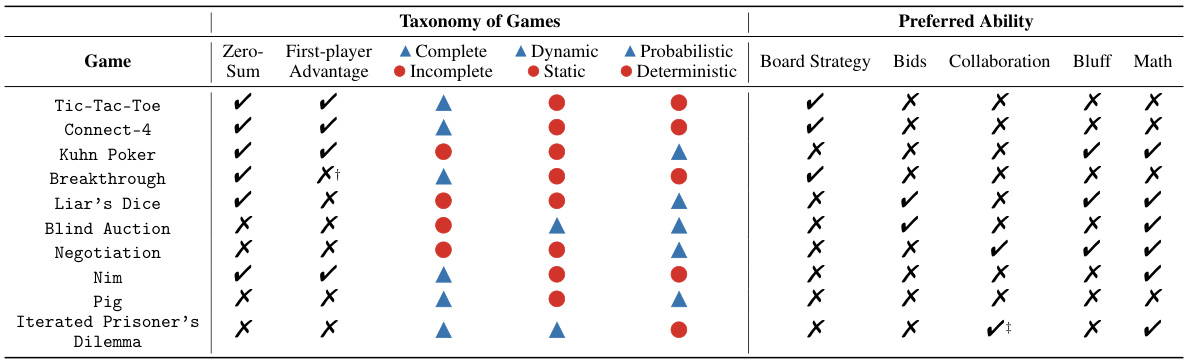

This table presents a taxonomy of 10 different game-theoretic tasks included in the GTBENCH benchmark. Each game is categorized across several dimensions: information completeness (complete vs. incomplete), game dynamics (static vs. dynamic), and the nature of chance (deterministic vs. probabilistic). Additionally, the table indicates which strategic reasoning abilities are most relevant to success in each game (board strategy, bids, collaboration, bluffing, and mathematical skills). This provides a comprehensive overview of the diverse strategic reasoning challenges assessed by the benchmark.

In-depth insights#

LLM Strategic Reasoning#

The strategic reasoning capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) are a critical area of research, as their increasing integration into real-world applications demands robust decision-making abilities. Current evaluations often fall short, relying heavily on metrics that assess fluency or factual accuracy rather than strategic thinking in competitive scenarios. This is where game-theoretic evaluations offer a valuable approach: by employing games with well-defined rules and objectives, we can directly assess an LLM’s capacity for strategic planning, anticipation of opponent moves, and adaptation to changing game states. The complexity of game theory provides a nuanced benchmark, far exceeding simple factual recall or text generation tasks. A key aspect of this research area is the identification and analysis of LLM limitations in strategic reasoning. While LLMs may perform well in games with probabilistic elements or incomplete information, they tend to struggle in those that require pure logic and deterministic actions. Understanding these limitations is crucial for future development, particularly for enhancing robustness and reliability. This also underscores the importance of developing standardized protocols and benchmarks for evaluating strategic reasoning abilities.

GTBench Framework#

The GTBench framework is a significant contribution to evaluating Large Language Models’ (LLMs) strategic reasoning capabilities. Its core strength lies in its game-theoretic approach, moving beyond simpler role-playing evaluations to assess LLMs in competitive scenarios using diverse games. This methodology allows for a more rigorous and nuanced assessment of LLMs’ ability to reason strategically, make inferences, and adapt in dynamic environments. The inclusion of various games, spanning different information states (complete vs. incomplete), dynamics (static vs. dynamic), and probability (deterministic vs. probabilistic), allows for a thorough characterization of LLM strengths and weaknesses across a wide range of conditions. The LLM-vs-LLM competition aspect is particularly novel, enabling direct comparison of different LLMs’ strategic reasoning abilities without relying on conventional solvers. This head-to-head approach provides valuable insights into the relative performance and inherent limitations of different models. The standardized protocols and comprehensive taxonomy of games enhance the framework’s reproducibility and extensibility, providing a valuable benchmark for future LLM development and evaluation. The focus on game-theoretic properties such as Nash Equilibrium and Pareto Efficiency offers further opportunities for deeper analysis of LLM behavior in complex interactive situations.

LLM vs. Solver#

A hypothetical ‘LLM vs. Solver’ section would be crucial for evaluating Large Language Model (LLM) capabilities. It would directly compare LLMs’ performance on complex tasks against that of established solvers, such as those using optimization or search algorithms (e.g., Monte Carlo Tree Search). This comparative analysis would reveal the strengths and limitations of LLMs in strategic reasoning. Do LLMs exhibit similar performance in various game scenarios, or do they struggle in deterministic games while performing better in probabilistic ones? Such a comparison highlights whether LLMs truly understand the underlying game theory or simply leverage pattern recognition and language processing capabilities. The results would potentially demonstrate that while LLMs can be competitive in games with incomplete information or probabilistic elements, their performance against optimal solvers in deterministic games, especially those with large action/state spaces, might still lag. Furthermore, exploring various prompt engineering techniques (like Chain-of-Thought) would provide insights into how these methods might help LLMs bridge the performance gap. The findings from this analysis would be invaluable for assessing current LLM capabilities and charting future research directions for enhancing strategic reasoning in LLMs.

Game-Theoretic Properties#

The section exploring “Game-Theoretic Properties” of LLMs in the context of strategic reasoning would delve into how well these models align with established game theory concepts. A key focus would be on Nash Equilibrium, investigating whether LLM strategies converge towards optimal solutions predicted by game theory, and quantifying this using metrics like regret. The analysis would also likely examine Pareto Efficiency, assessing whether the LLM’s actions in multi-agent scenarios yield outcomes where no player can improve their position without harming others. Analyzing these aspects across different game types (complete/incomplete information, deterministic/probabilistic) would reveal how LLM performance varies depending on the game’s structure and information availability. The presence of repeated games would allow examination of LLM learning and adaptation over time, observing if strategies evolve towards stable equilibriums or exhibit other dynamic behaviors. Overall, this section aims to provide a robust and nuanced evaluation of LLMs’ strategic capabilities, comparing their behavior against theoretical ideals of game theory, and revealing important insights into their decision-making processes within competitive environments.

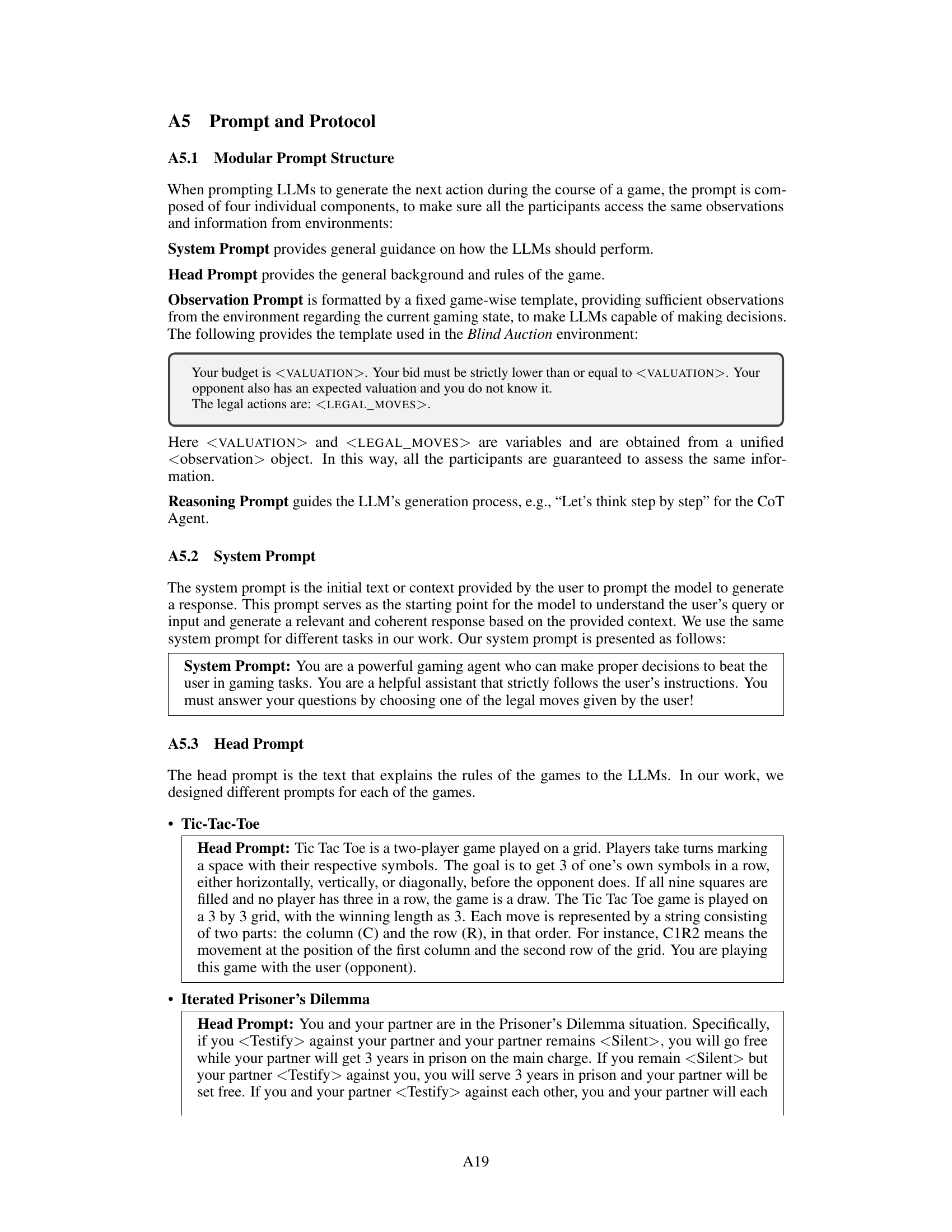

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending GTBENCH to encompass a broader range of game types is crucial to gain a more comprehensive understanding of LLMs’ strategic reasoning abilities, particularly in genres with varying levels of complexity, information asymmetry, and dynamics. Another critical area is investigating the influence of different LLM architectures and training methodologies on their performance in game-theoretic tasks. This involves comparing models pre-trained on diverse data, focusing on those specifically tailored to enhance reasoning skills. A deeper dive into developing more sophisticated evaluation metrics beyond NRA and Elo ratings is needed, possibly incorporating measures of fairness, robustness, and efficiency. This could also involve creating more robust and adaptable benchmarks to ensure the continued relevance and accuracy of evaluations as LLMs evolve. Finally, research should focus on developing novel reasoning methods specifically designed for game-theoretic settings, potentially combining symbolic and sub-symbolic AI techniques to surpass the limitations of current approaches. Ultimately, the goal is to create a more reliable and generalizable framework for evaluating the capabilities of LLMs in complex strategic reasoning scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

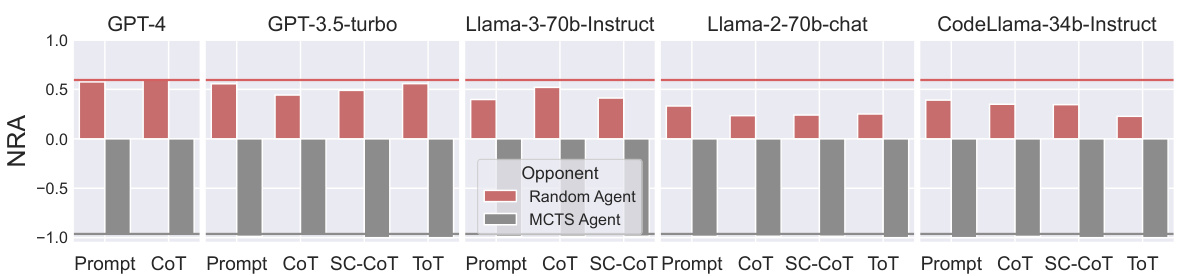

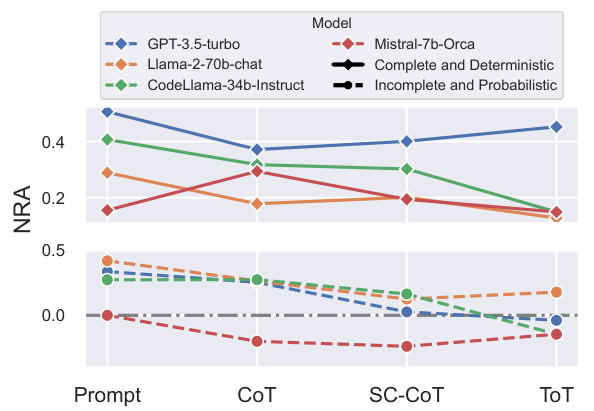

This figure shows the Normalized Relative Advantage (NRA) of various LLMs against both random agents and Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) agents across four deterministic games. The LLMs employ different reasoning methods (Prompt, CoT, SC-CoT, ToT). The results reveal that LLMs struggle significantly against MCTS agents, indicating limitations in strategic reasoning in deterministic scenarios. However, they outperform random agents, highlighting their basic strategic capabilities.

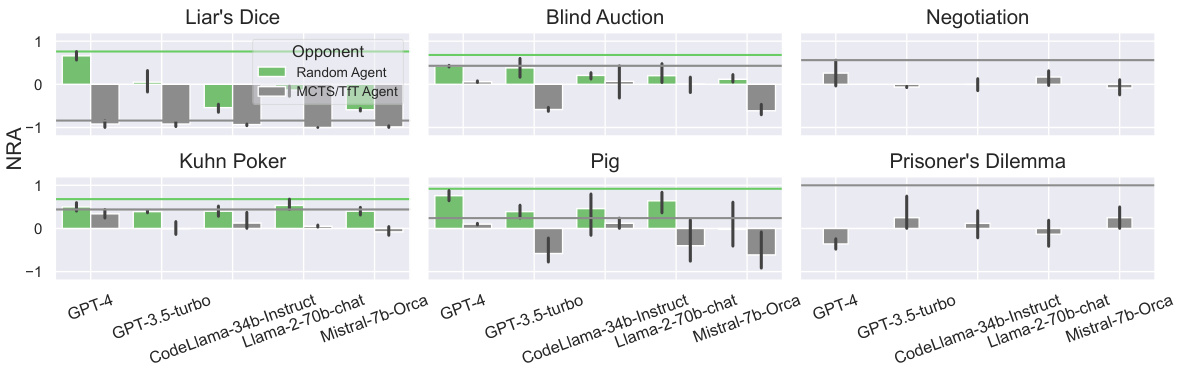

This figure shows the Normalized Relative Advantage (NRA) of different LLMs across various probabilistic and incomplete information games. It compares their performance against both MCTS (Monte Carlo Tree Search) and random agents, highlighting how different reasoning methods (Prompt, CoT, SC-COT) affect their strategic capabilities in these scenarios. The error bars represent the variability in performance across different reasoning methods. The green and grey lines indicate the maximum NRA achieved by the LLMs in each game.

The figure shows the Normalized Relative Advantage (NRA) of several large language models (LLMs) when playing against Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) agents and random agents in complete and deterministic game scenarios. The NRA is a metric that measures the relative advantage of one player over another. Positive NRA indicates that the LLM outperforms the opponent, negative values indicate the opposite, and a value near zero means that both perform comparably. The figure displays the results across different reasoning methods used by the LLMs, showing the effectiveness of each approach in these games. The red and grey lines represent the maximum NRA achieved by each LLM, highlighting their best performances.

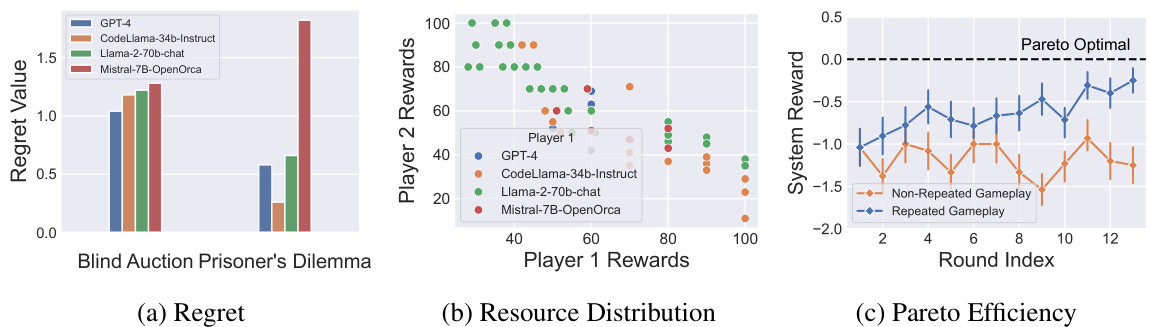

This figure shows the results of evaluating the game-theoretic properties of LLMs. Panel (a) displays the regret values for different LLMs in Blind Auction and Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma. Panel (b) illustrates the resource distribution agreements reached by the LLMs in a negotiation game, showing the rewards obtained by each player. Panel (c) demonstrates Pareto efficiency, comparing the system rewards achieved in both non-repeated and repeated gameplay scenarios. The overall goal is to understand the strategic behavior and decision-making of LLMs under different game-theoretic settings.

The figure shows the Normalized Relative Advantage (NRA) of several LLMs in complete and deterministic game scenarios, such as Tic-Tac-Toe and Connect 4. The LLMs are compared against both a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) agent (a strong baseline) and a random agent. The results are presented for different reasoning methods (Prompt, CoT, SC-COT, and ToT) used with each LLM. The red and gray lines highlight the best performance obtained by each LLM across all methods.

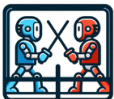

The bar chart compares the performance of different prompting methods on the GPT-3.5-turbo model across various game-theoretic tasks. The ‘Prompt’ method represents a simple prompt without any explicit reasoning instructions. ‘CoT (used)’ shows the performance of the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting method used in the main paper. ‘Other CoT’ encompasses the results from four additional CoT templates (templates 1-4, detailed in Table A9). The y-axis represents the Normalized Relative Advantage (NRA), a measure of the model’s performance against a conventional solver. The chart reveals the relative effectiveness of these different prompting strategies in influencing the strategic reasoning capabilities of the model.

This figure shows the overall architecture of GTBENCH, a language-driven environment for evaluating LLMs’ strategic reasoning abilities. It highlights three main components: Participants (LLMs or other agents), Prompt Adapter (for converting observations to prompts and actions), and Environments (game environments). The flow of information and actions among these components is visually represented, demonstrating how GTBENCH facilitates game-theoretic evaluations of LLMs.

This figure shows the normalized relative advantage (NRA) of various LLMs against both MCTS (Monte Carlo Tree Search) and random agents across four games: Tic-Tac-Toe, Connect Four, Breakthrough, and Nim. These games represent scenarios with complete and deterministic information. The NRA values indicate the relative performance of the LLMs compared to the benchmarks. Red and gray lines highlight the peak NRA scores achieved by each LLM across different reasoning methods.

This figure shows the overall architecture of GTBENCH, a language-driven environment for evaluating LLMs’ strategic reasoning abilities. It highlights the three main components: Participants (LLMs or other agents), Prompt Adapter (which translates observations into prompts for the agents and extracts actions from their responses), and Environments (which host the games and provide observations and action execution). The diagram visually depicts the flow of information and control between these components, illustrating how observations are converted into prompts, how participants generate actions, and how those actions are executed within the game environments.

This figure displays the Normalized Relative Advantage (NRA) scores for various LLMs against both MCTS (Monte Carlo Tree Search) and Random agents across four complete and deterministic games. The NRA score indicates the relative performance of the LLM compared to the other agents; positive scores show that the LLM outperforms the other agent, while negative scores indicate underperformance. The red and gray lines in each bar highlight the best NRA achieved by any of the tested reasoning methods for that LLM in that game.

More on tables

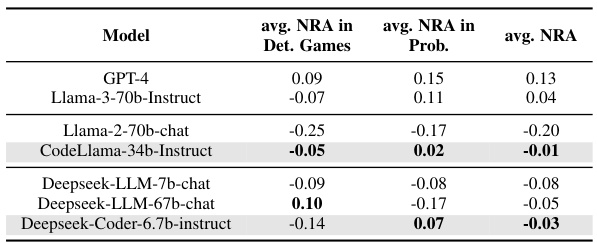

This table shows the average NRA (Normalized Relative Advantage) scores for different LLMs across two categories of games: deterministic and probabilistic. It highlights how code-pretrained LLMs perform comparatively to other LLMs, indicating the impact of code-pretraining on strategic reasoning abilities in game-playing scenarios.

This table shows the average NRA (Normalized Relative Advantage) scores for different LLMs across two categories of games: deterministic and probabilistic. It compares the performance of LLMs with and without code-pretraining, highlighting how code-pretraining impacts strategic reasoning abilities in these game scenarios. Higher NRA values indicate better performance compared to a baseline agent.

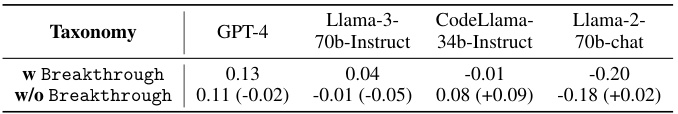

This table shows the average normalized relative advantage (NRA) scores for different LLMs across various game-theoretic tasks. It compares the performance with and without the Breakthrough game included, highlighting how the inclusion or exclusion of more complex games can affect the overall performance scores of different LLMs. The results suggest that some LLMs struggle more with complex game rules.

This table presents the quantitative results of five common error patterns observed in the GTBENCH experiments. The error patterns are: Endgame Misdetection, Misinterpretation, Overconfidence, Calculation Error, and Factual Error. The table shows the percentage of each error pattern observed when GPT-4 with Chain-of-Thought reasoning was used as an agent in the games.

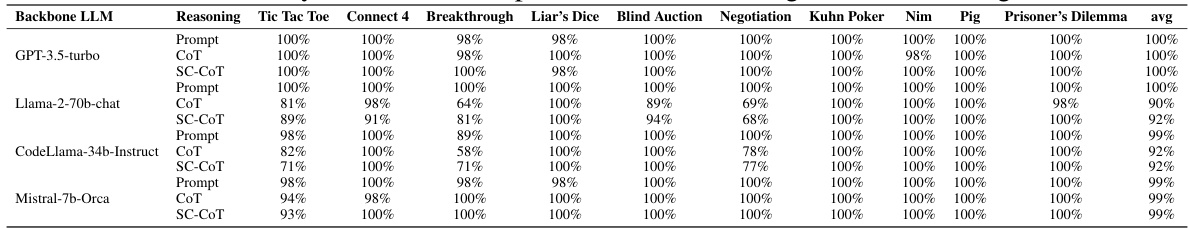

This table presents the Elo ratings of various LLMs competing against each other in different game-theoretic tasks. The Elo rating system is used to quantify the relative skill levels of the players, higher Elo indicating better performance. The table shows the average Elo rating for each LLM across five games: Tic-Tac-Toe, Breakthrough, Blind Auction, Kuhn Poker, and Liar’s Dice. This allows for a comparison of the strategic reasoning abilities of different LLMs.

This table presents a taxonomy of games used in GTBENCH, categorized by information completeness (complete vs. incomplete), game dynamics (static vs. dynamic), and outcome determinism (deterministic vs. probabilistic). Each game is further analyzed based on the strategic abilities required to excel. The table lists 10 games, their categories, and the primary strategic abilities needed to play effectively (Board Strategy, Bidding, Collaboration, Bluff, Math).

This table shows the average Normalized Relative Advantage (NRA) scores achieved by different LLMs across different game categories (deterministic and probabilistic). It highlights the impact of code-pretraining on the strategic reasoning capabilities of LLMs by comparing the performance of code-pretrained models against non-code-pretrained models. The results demonstrate that code-pretraining significantly improves the performance of LLMs in game-theoretic tasks.

This table shows the average Normalized Relative Advantage (NRA) in probabilistic and deterministic games for different LLMs at various temperatures (0.4, 0.6, and 0.8). It demonstrates how the temperature setting affects the performance of LLMs in different game types.

This table presents a taxonomy of ten games used in the GTBENCH benchmark. For each game, it indicates whether it is zero-sum, has a first-player advantage, involves complete or incomplete information, is dynamic or static, and is probabilistic or deterministic. It also lists the preferred reasoning abilities (board strategy, bidding, collaboration, bluffing, math) required for success in each game. The table helps to categorize the games based on their properties, highlighting their diversity and the range of strategic reasoning abilities they test.

This table presents ten different game environments used in the GTBENCH benchmark. Each game is categorized according to several game-theoretic properties, such as whether it has complete or incomplete information, whether it is deterministic or probabilistic, and whether it is static or dynamic. The table also lists the preferred cognitive abilities needed to succeed in each game, such as board strategy, bidding, collaboration, bluffing, and mathematical skills.

This table presents a taxonomy of games used in the GTBENCH benchmark. For each game (Tic-Tac-Toe, Connect-4, Kuhn Poker, Breakthrough, Liar’s Dice, Blind Auction, Negotiation, Nim, Pig, Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma), it indicates whether it is zero-sum or not, whether it has a first-player advantage, whether it has complete or incomplete information, whether it is deterministic or probabilistic, whether it is static or dynamic, and what strategic abilities it requires (board strategy, bids, collaboration, bluff, math). This information helps to categorize and understand the characteristics of the games included in the benchmark, which aids in evaluating different strategic reasoning capabilities of LLMs.

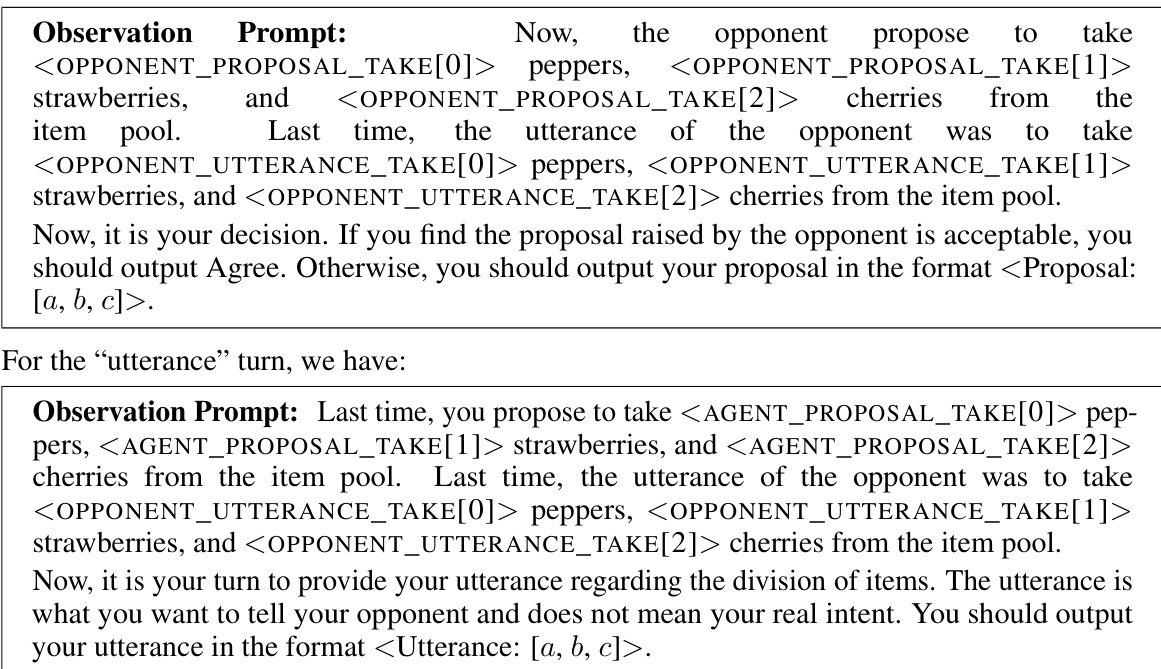

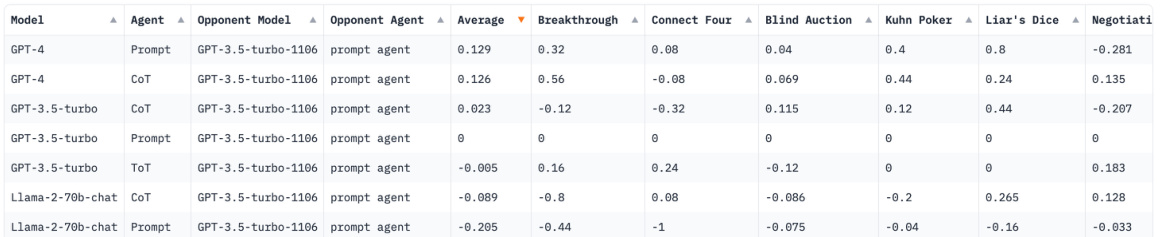

This table presents the Normalized Relative Advantage (NRA) scores for various LLMs competing against GPT-3.5-turbo with a Prompt Agent in ten different games. The table shows the results of LLM vs. LLM competitions, enabling comparison of different LLMs’ strategic reasoning abilities across diverse gaming scenarios. The average NRA is shown, along with NRA for each individual game.

Full paper#