↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Unsupervised learning of visual concepts is challenging due to the difficulty of creating representations that are both descriptive and distinct, leading to models that are hard to interpret and revise. Existing methods often rely on additional (prior) knowledge or supervision. This paper aims to tackle this challenge by introducing the Neural Concept Binder (NCB), which focuses on deriving both discrete and continuous concept representations to overcome the limitations of existing approaches.

NCB employs two types of binding: soft binding (using SysBinder) for object-factor encodings and hard binding (using hierarchical clustering and retrieval) to obtain expressive, discrete representations. This approach allows intuitive inspection and integration of external knowledge, such as human input or insights from other AI models. The paper demonstrates NCB’s effectiveness on the newly introduced CLEVR-Sudoku dataset, showcasing its ability to integrate with both neural and symbolic modules for complex reasoning tasks. NCB improves the interpretability and reliability of unsupervised concept learning for visual reasoning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel framework for unsupervised concept learning in visual reasoning, addressing the challenge of creating descriptive and distinct concept representations. It offers a solution to the interpretability problem in AI by enabling straightforward inspection and revision of learned concepts, bridging the gap between neural and symbolic AI. The CLEVR-Sudoku dataset introduced in the paper provides a valuable benchmark for future research in visual reasoning and complex problem solving.

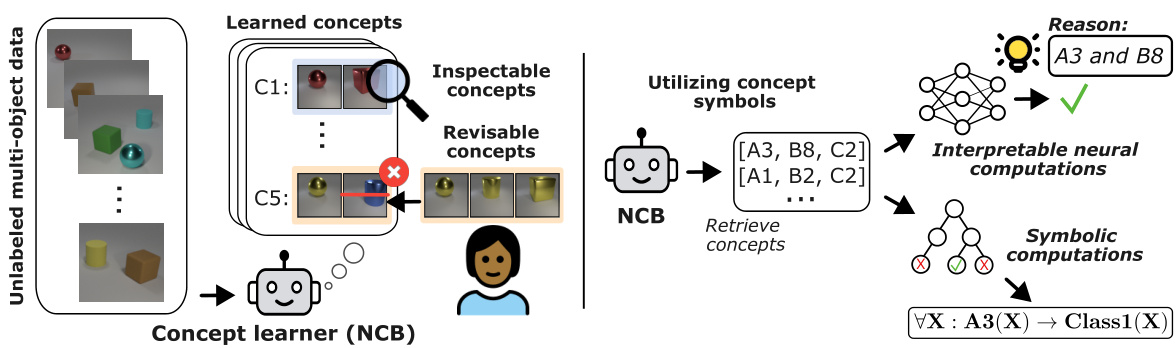

Visual Insights#

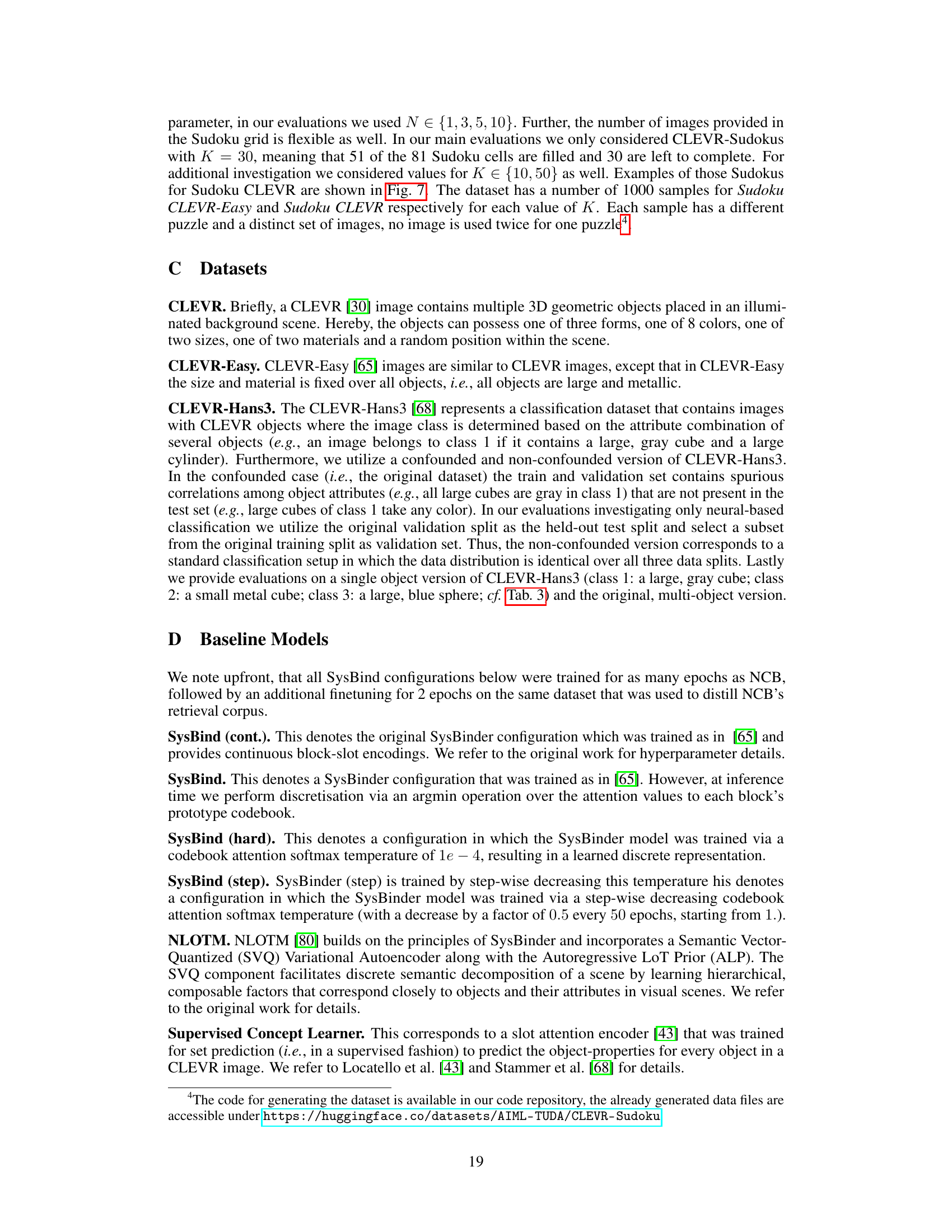

This figure illustrates the unsupervised learning of concepts for visual reasoning. The left panel highlights the challenge of learning inspectable and revisable concepts from unlabeled data, emphasizing the need for human users to understand and correct the model’s learned concepts. The right panel introduces the Neural Concept Binder (NCB) as a solution. NCB generates both interpretable neural and symbolic concept representations, enabling intuitive inspection, straightforward integration of external knowledge, and seamless integration into both neural and symbolic modules for complex reasoning tasks. The figure visually depicts the NCB workflow, from input data to the generation of concept representations used for both neural and symbolic reasoning.

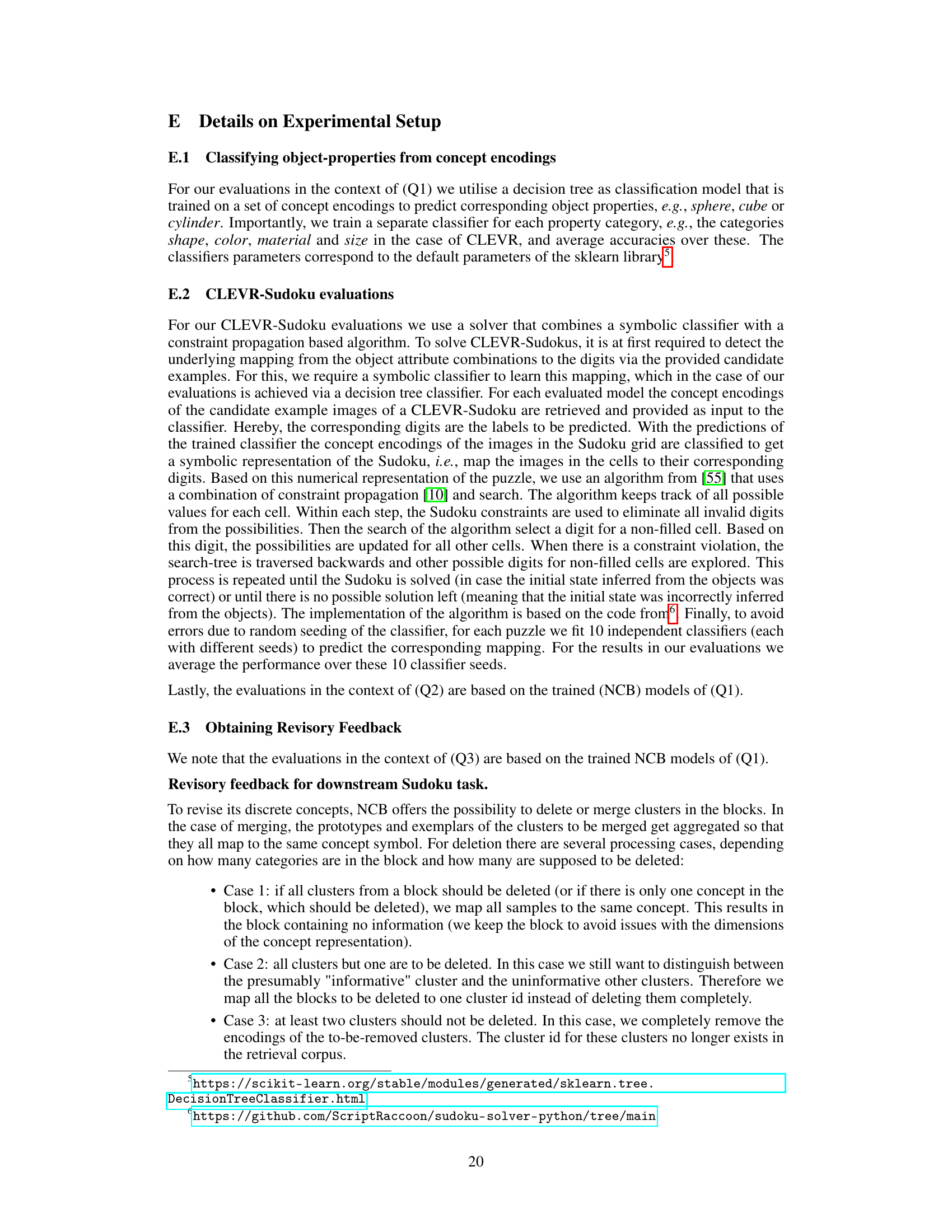

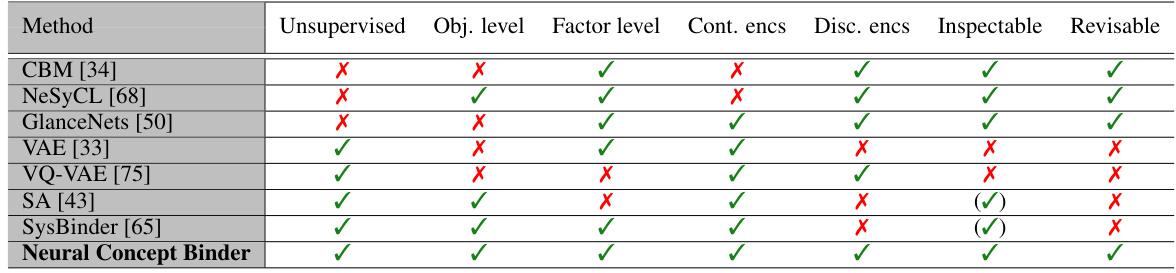

This table compares several methods for concept learning across seven criteria: whether the learning is unsupervised, whether object-level and factor-level concepts are considered, whether continuous or discrete concept encodings are used, and whether the resulting concept representations are inherently inspectable and revisable. It highlights the unique capabilities of the Neural Concept Binder (NCB) in contrast to existing methods.

In-depth insights#

NCB Framework#

The Neural Concept Binder (NCB) framework presents a novel approach to unsupervised visual concept learning, addressing the challenge of creating descriptive and distinct concept representations. NCB uniquely combines soft and hard binding mechanisms: soft binding uses SysBinder for object-factor disentanglement, generating continuous encodings, while hard binding employs hierarchical clustering and retrieval-based inference to produce expressive, discrete representations. This two-stage process allows for intuitive inspection and easy integration of external knowledge, enhancing both the interpretability and revisability of the learned concepts. The structured nature of NCB’s concept representations facilitates seamless integration into both neural and symbolic reasoning modules, enabling more complex reasoning tasks. The framework is evaluated on a newly introduced CLEVR-Sudoku dataset, showcasing its effectiveness in handling tasks requiring both visual perception and logical reasoning. NCB’s capacity for concept inspection and revision is a significant advantage, allowing for human-in-the-loop refinement and aligning learned concepts with human understanding or external knowledge bases like GPT-4. Overall, NCB offers a promising path towards more reliable, interpretable, and flexible unsupervised visual concept learning.

Unsupervised Learning#

Unsupervised learning, in the context of visual reasoning, presents a significant challenge due to the inherent difficulty in learning expressive and distinct concept representations without explicit labels. The lack of supervision necessitates that the model’s learned concepts are easily interpretable and revisable, allowing human users to understand and correct any misconceptions. This contrasts with supervised methods which rely on labeled data, making the learning process more straightforward but inherently limiting generalizability and the possibility for discovering novel, unexpected concepts. Object-based visual reasoning adds further complexity, requiring the model to understand the relationships between multiple objects within a scene. Successfully achieving unsupervised learning in this domain requires innovative approaches that can disentangle object factors and generate both discrete and continuous concept representations. The development of such techniques is critical for building AI systems that can reason about the world in a more human-like manner, enabling more robust, understandable, and trustworthy AI.

CLEVR-Sudoku#

The proposed CLEVR-Sudoku dataset presents a novel and insightful approach to evaluating visual reasoning models. By integrating Sudoku puzzles with CLEVR-style images, it cleverly combines visual perception and logical reasoning, necessitating a more holistic understanding of visual information. The dataset’s design inherently tests the model’s ability to map visual concepts onto symbolic representations (digits). The difficulty is adjustable by controlling the number of example images for each digit mapping, thus offering a scalable benchmark. The challenge lies not only in object recognition, but also in accurately translating visual attributes into numerical values which are critical for solving the puzzle. This innovative approach provides a valuable assessment of a model’s capacity to connect visual and symbolic domains, paving the way for more comprehensive evaluation of AI systems beyond traditional image classification tasks. CLEVR-Sudoku’s unique structure addresses the shortcomings of current benchmarks by requiring both perceptual and logical capabilities, promoting a more robust and meaningful evaluation of visual reasoning models. The flexible design allows for modifications in difficulty levels, rendering this dataset a versatile tool for researching and developing advanced AI systems.

Concept Inspection#

Concept inspection in unsupervised visual learning is crucial for establishing trust and ensuring reliability. The ability to inspect and understand a model’s learned concepts is paramount, allowing for the identification of inaccuracies or biases. Methods for concept inspection should facilitate a user-friendly and intuitive understanding of the model’s internal representations. This might involve visualizing the learned concepts, providing explanations for their formation, or allowing users to query the model about its understanding. Interactive methods where users can actively probe the model’s knowledge are particularly valuable. Effective concept inspection methods must be tailored to the specific nature of the learned representations, whether continuous or discrete, and the complexity of the visual reasoning task. Ultimately, robust concept inspection contributes to the development of more transparent, accountable, and reliable AI systems.

Future Work#

The paper’s lack of a dedicated “Future Work” section presents an opportunity for deeper discussion. Future research could explore integrating NCB with continual learning frameworks, enhancing its ability to adapt to evolving visual concepts. Another promising area involves high-level concept learning, extending the capabilities beyond object-factor representations to more complex relational understanding. The seamless integration of NCB with probabilistic logic programming warrants investigation, potentially improving the reliability and explainability of complex reasoning tasks. Additionally, researching the effects of incorporating downstream learning signals into NCB’s initial training could significantly enhance performance. Finally, a thorough exploration of mitigating the potential for malicious concept manipulation by refining the human-in-the-loop revision process is critical for ensuring trustworthy and reliable AI applications based on NCB.

More visual insights#

More on figures

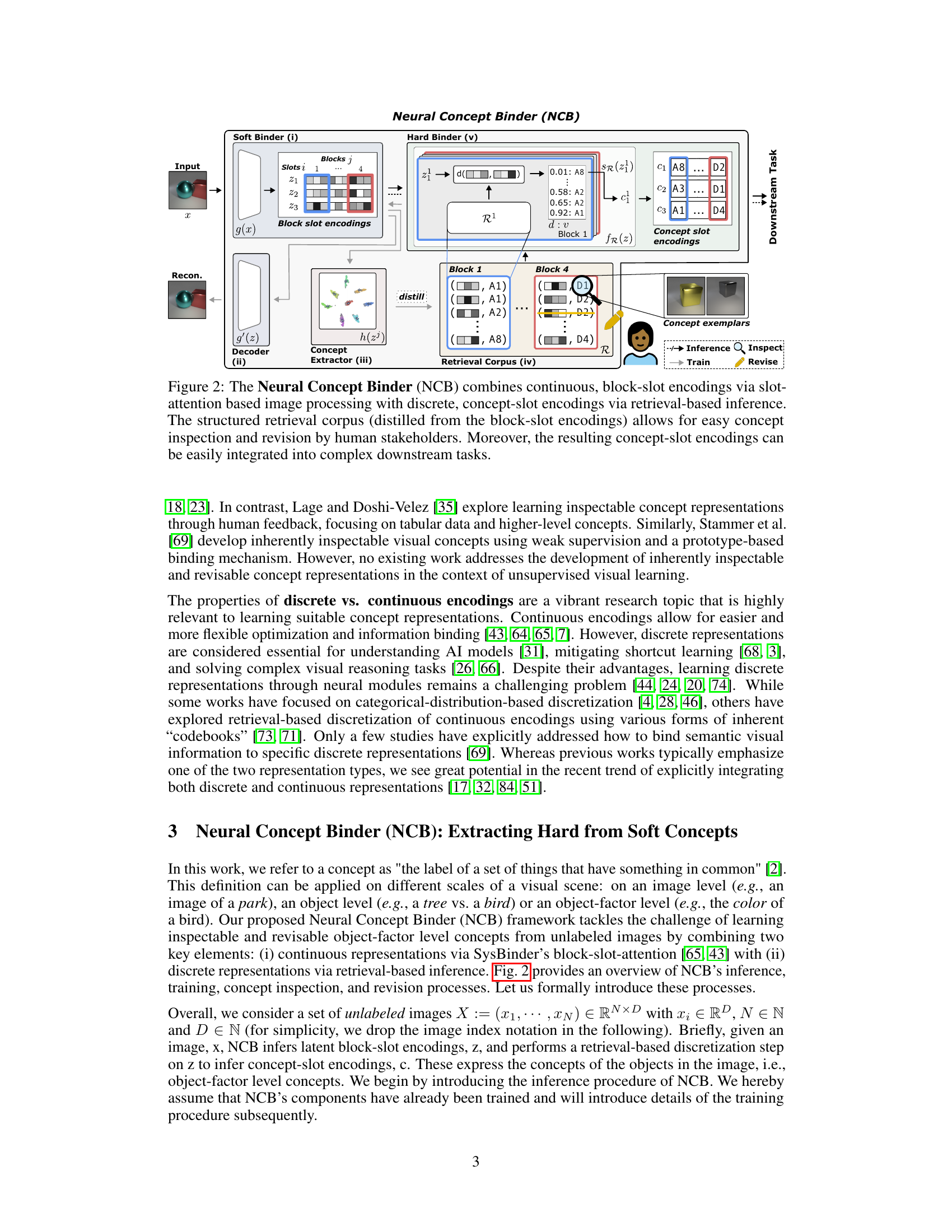

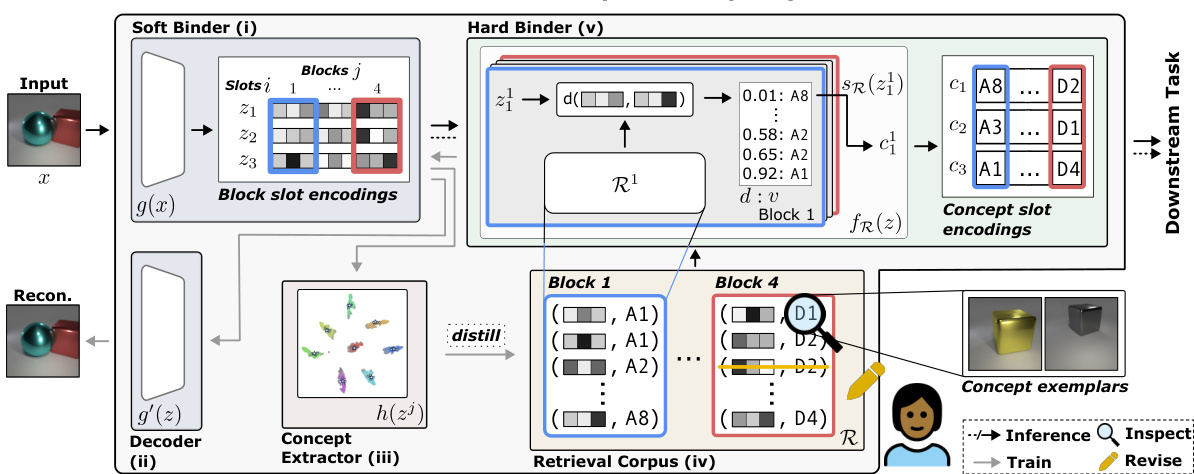

This figure illustrates the Neural Concept Binder (NCB) framework. It shows how NCB combines two types of binding: soft binding (using SysBinder for object-factor disentanglement) and hard binding (using hierarchical clustering and retrieval-based inference). The soft binding produces continuous block-slot encodings, which are then used to create a retrieval corpus of discrete concept-slot encodings. This corpus allows for easy inspection and revision of concepts by human stakeholders. Finally, the concept-slot encodings can be used in downstream tasks.

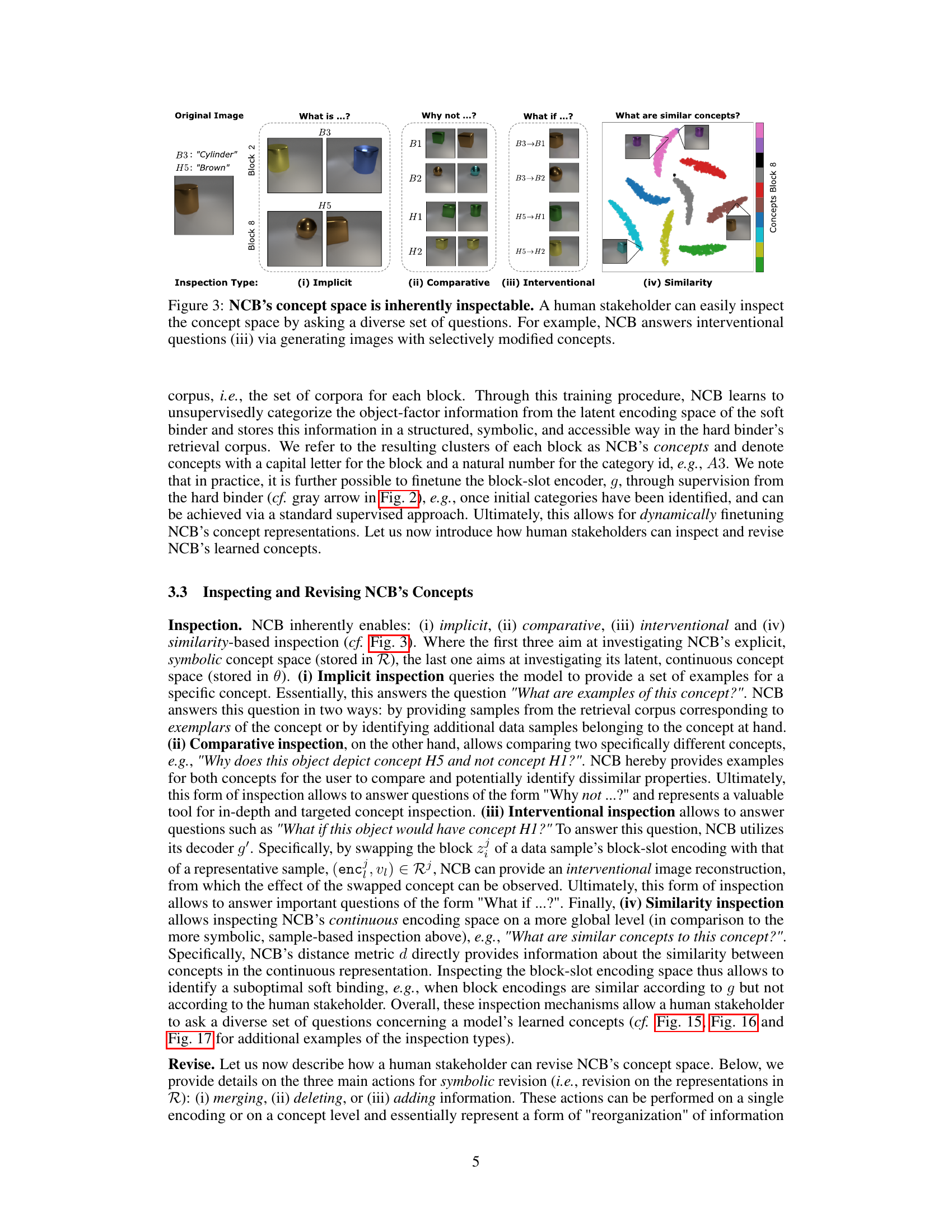

This figure demonstrates the inherent inspectability of the Neural Concept Binder (NCB)’s concept space. It shows how a human user can interact with the model by asking different types of questions to understand its learned concepts. Four types of inspection are shown: (i) Implicit, which asks for examples of a concept; (ii) Comparative, which compares two concepts; (iii) Interventional, which shows what happens when a concept is altered; and (iv) Similarity, which shows similar concepts. This illustrates the NCB’s ability to provide human-understandable feedback, improving model trust and allowing for easy revision of the learned concepts.

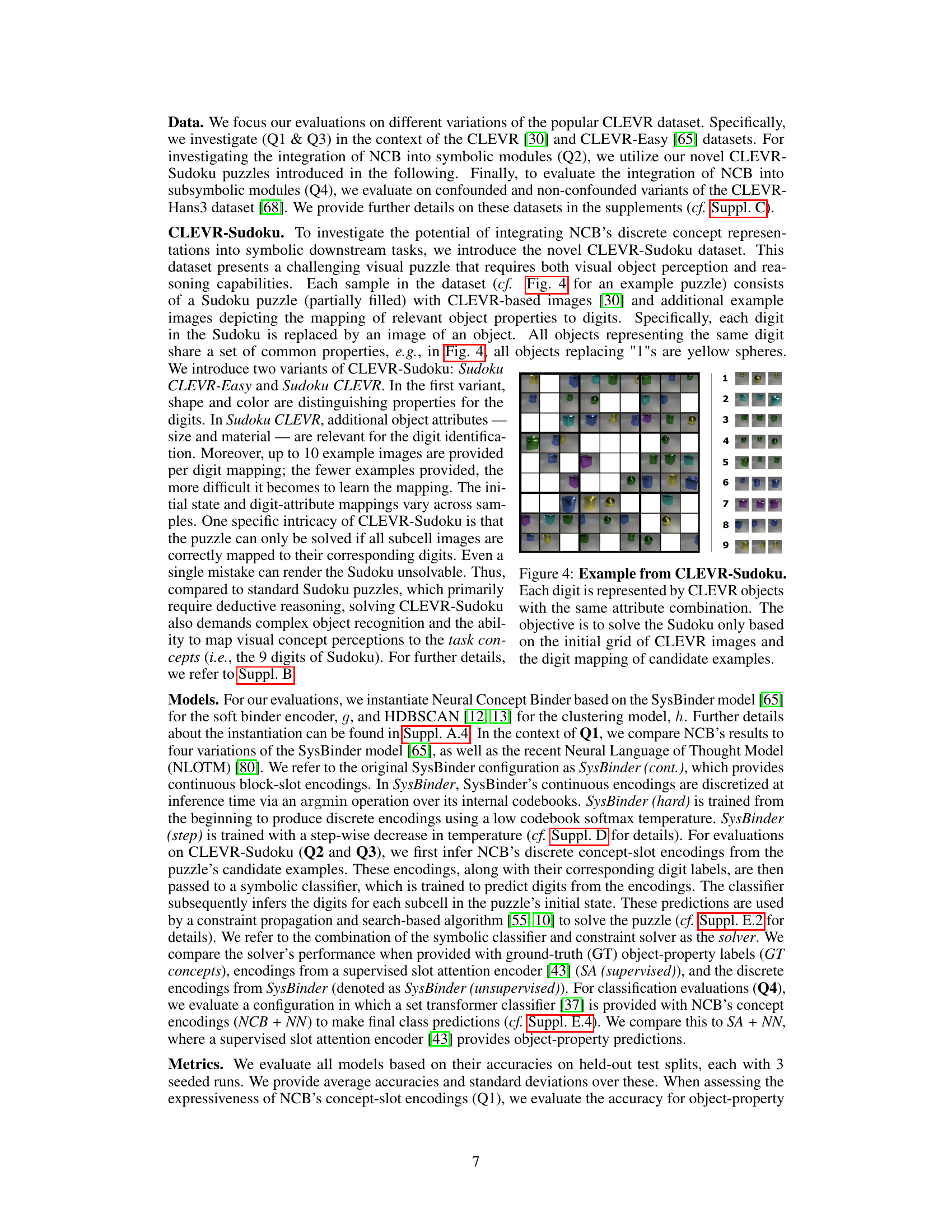

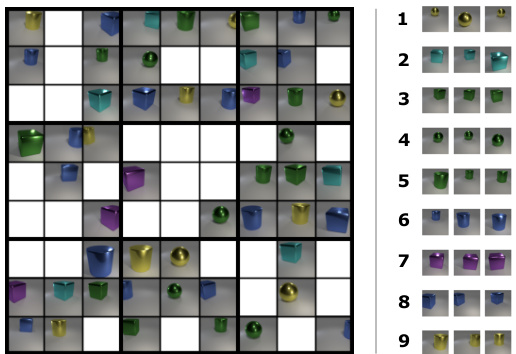

This figure shows an example of a CLEVR-Sudoku puzzle. A standard Sudoku grid is shown, but instead of numbers, each cell contains a small image of a 3D object from the CLEVR dataset. To the right is a key that shows the mapping between the objects and the digits 1-9. The goal is to solve the Sudoku puzzle by identifying the objects and using the key to translate them into digits.

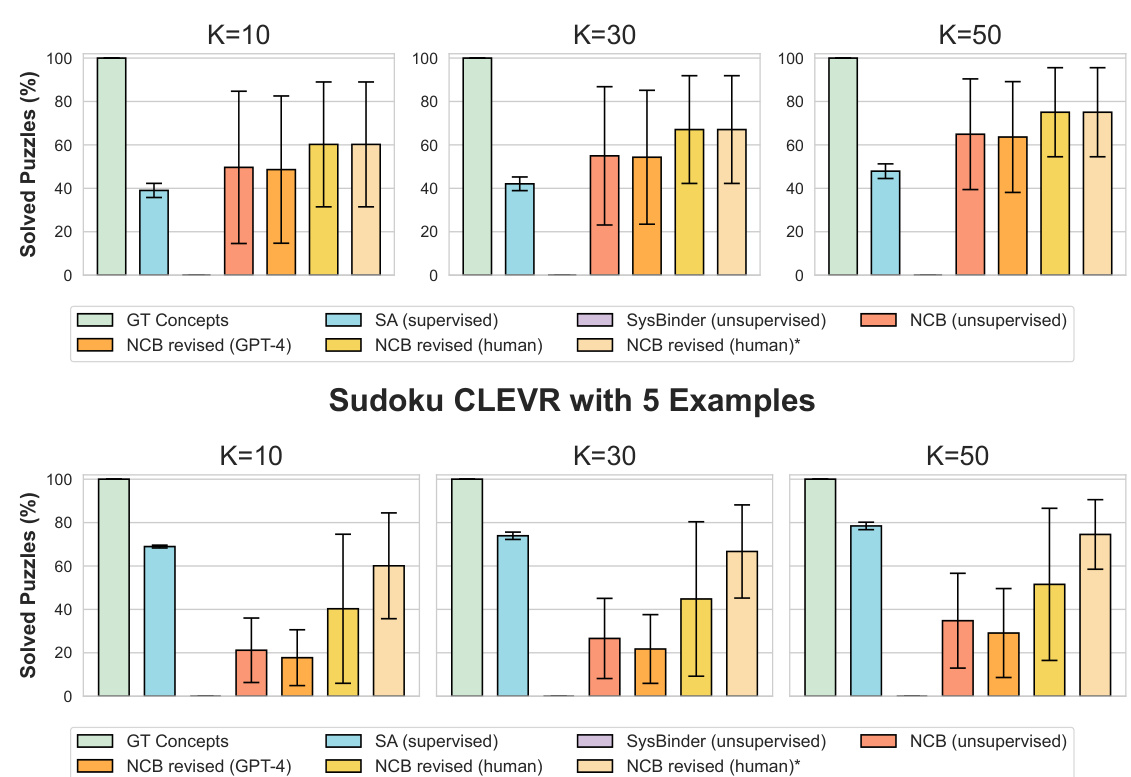

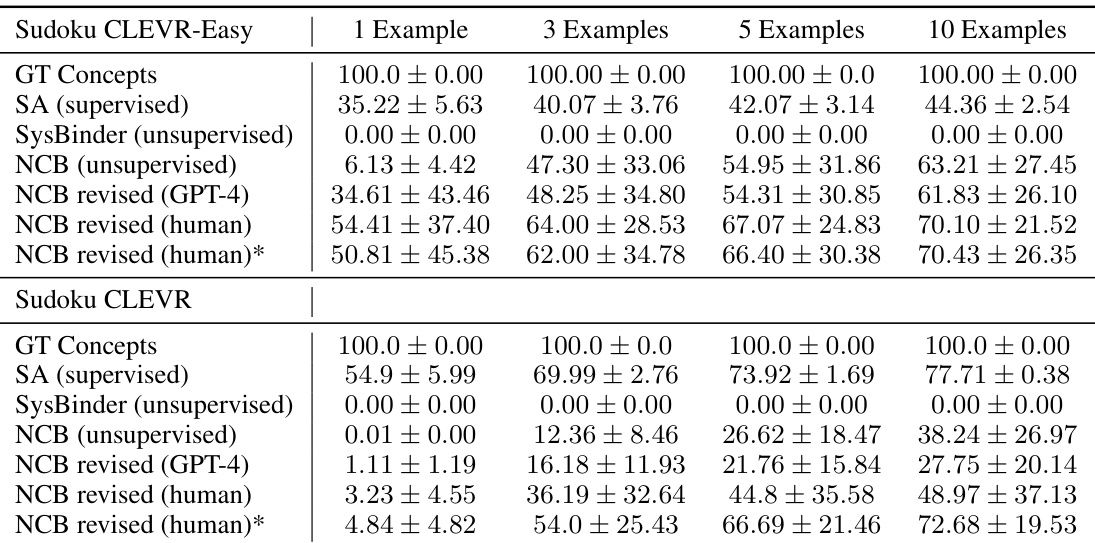

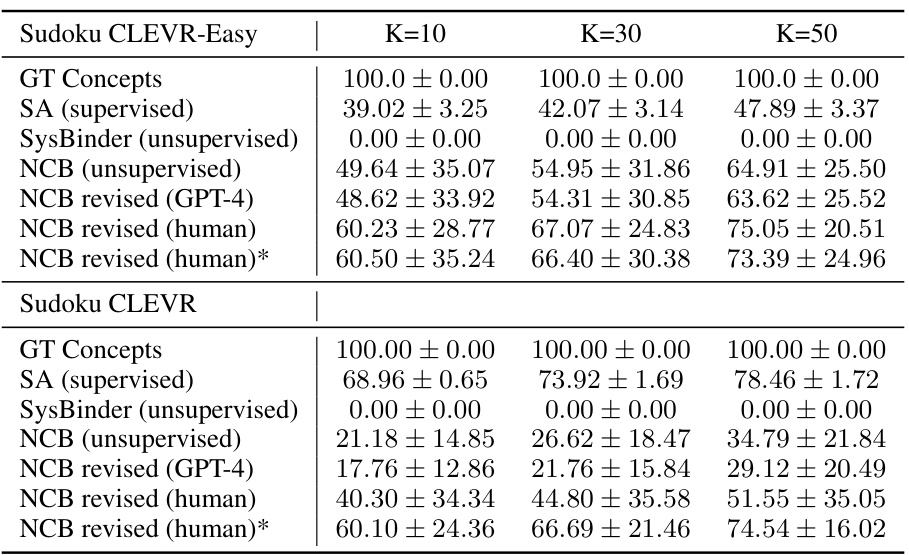

This figure shows the results of using different methods for solving Sudoku puzzles with images as input. The left side compares the performance of using ground truth concepts, supervised slot attention, unsupervised SysBinder, and unsupervised NCB. The right side shows how performance improves when human feedback or GPT-4 is used to revise the NCB concepts. The results are shown separately for easier and harder versions of the Sudoku puzzle (CLEVR-Easy and CLEVR). The figure demonstrates that NCB performs well compared to other unsupervised methods and that concept revision can significantly improve performance.

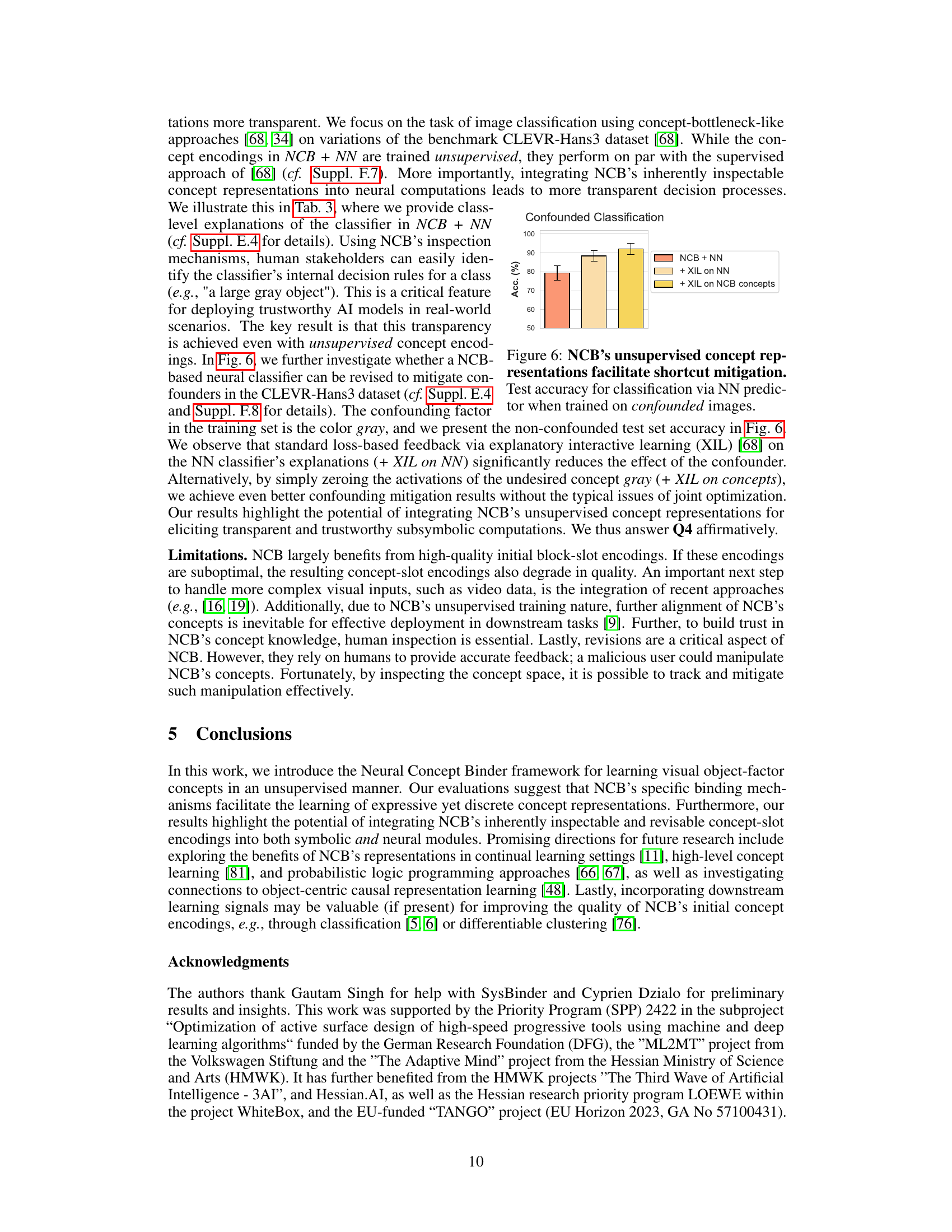

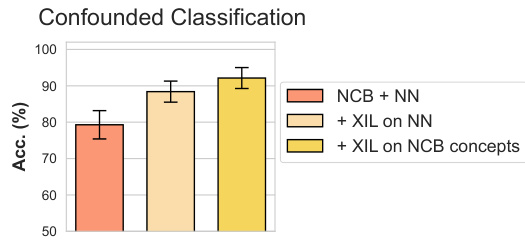

This figure shows the results of a classification task on a dataset with confounding factors. Three different methods are compared: using only the Neural Concept Binder (NCB) for feature extraction, using NCB and then performing explanatory interactive learning (XIL) on the neural network (NN) classifier, and performing XIL directly on the NCB concepts before classification. The graph plots the accuracy for each method. The results demonstrate that applying XIL directly on the NCB concepts achieves better mitigation of the confounding factors than performing XIL only on the NN classifier. This highlights how NCB’s interpretable concepts facilitate a more transparent and effective method for addressing shortcut learning issues.

This figure shows examples of Sudoku puzzles from the CLEVR-Sudoku dataset for different values of K. K represents the number of empty cells in the 9x9 Sudoku grid. Each cell contains a CLEVR image representing a digit; different digits are represented by different image attributes (shape and color in CLEVR-Easy, shape, color, size, and material in CLEVR). The examples illustrate how the difficulty of the puzzle changes with the number of empty cells (K). A lower K value means more pre-filled cells, making the puzzle easier to solve.

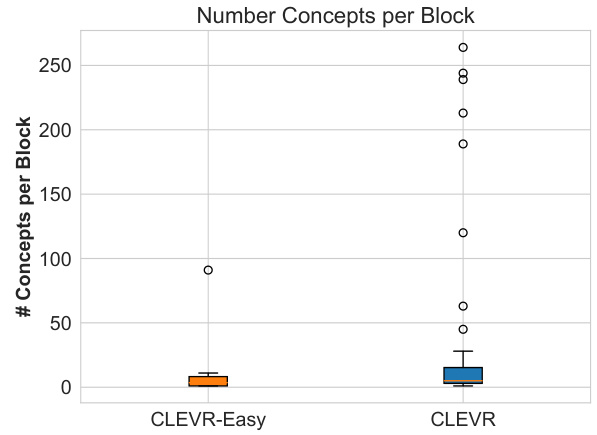

This figure shows the average number of concepts found across all blocks in the NCB’s retrieval corpus for both CLEVR-Easy and CLEVR datasets. The data suggests a significant difference in the number of concepts learned between the two datasets, indicating a potential relationship between dataset complexity and the number of concepts needed for representation.

This boxplot shows the distribution of the number of concepts per block in the Neural Concept Binder (NCB) model when trained on the CLEVR-Easy and CLEVR datasets. The x-axis represents the dataset (CLEVR-Easy or CLEVR), and the y-axis represents the number of concepts found within each block. Each boxplot displays the median, quartiles, and outliers of the distribution. The figure shows a much wider range and greater variability in the number of concepts per block for the CLEVR dataset compared to the CLEVR-Easy dataset, indicating more complexity in the concept representations learned from the CLEVR data.

This figure shows the results of using different concept encodings to solve Sudoku puzzles where images are used in place of digits. The left side compares the performance of using ground truth concepts, supervised slot attention encoder, unsupervised SysBinder, and unsupervised NCB. The right side shows how performance improves with human and GPT-4 revisions of the NCB concepts.

This figure shows the results of using different concept encodings to solve Sudoku puzzles. The left side compares the performance of using ground truth concepts, supervised slot attention encodings, unsupervised SysBinder encodings, and unsupervised Neural Concept Binder (NCB) encodings. The right side shows how revising the NCB concepts, either with GPT-4 or human feedback, impacts the results. It demonstrates that NCB’s unsupervised concepts perform well, particularly when human feedback is used for revision, highlighting the effectiveness of the NCB framework for symbolic reasoning tasks.

This figure shows the results of using different concept encodings to solve Sudoku puzzles using images from the CLEVR dataset. The left side compares the performance of ground truth concepts, NCB’s unsupervised concepts, supervised concepts from a slot attention encoder, and unsupervised concepts from SysBinder. The right side shows how human and GPT-4 revisions of NCB’s concepts affect performance. The results demonstrate that NCB’s unsupervised concepts achieve comparable performance to supervised methods and are easily improved through human revision.

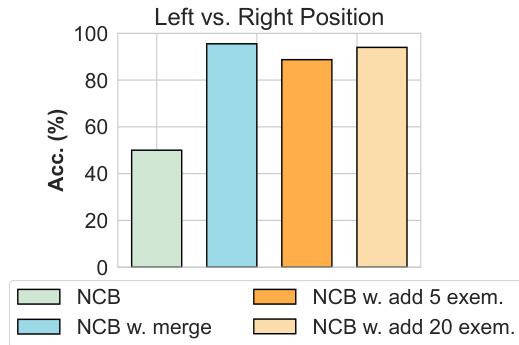

This figure shows the test accuracy of a classifier trained to predict whether objects are located on the left or right side of a scene. Four different NCB configurations are compared: a standard NCB, NCB with concepts merged to represent ’left’ and ‘right’, and NCB with 5 and 20 exemplar images added for ’left’ and ‘right’ concepts respectively. The results demonstrate the ability to easily add new concepts and improve accuracy by adding more concept information to NCB.

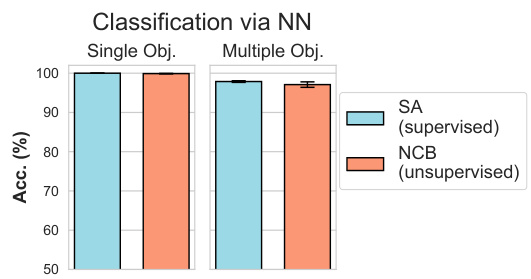

This figure displays the results of an experiment evaluating the ability of NCB’s unsupervised concept representations to mitigate shortcut learning. Two models were tested: one using supervised concept representations (SA), and one using NCB’s unsupervised representations. The experiment involved training on images with a confounding factor (the color gray) and testing on images without that confounding factor. The results show that NCB’s unsupervised approach was able to achieve comparable performance to the supervised method in mitigating the effects of the confounding factor, demonstrating the effectiveness of NCB in learning robust concept representations.

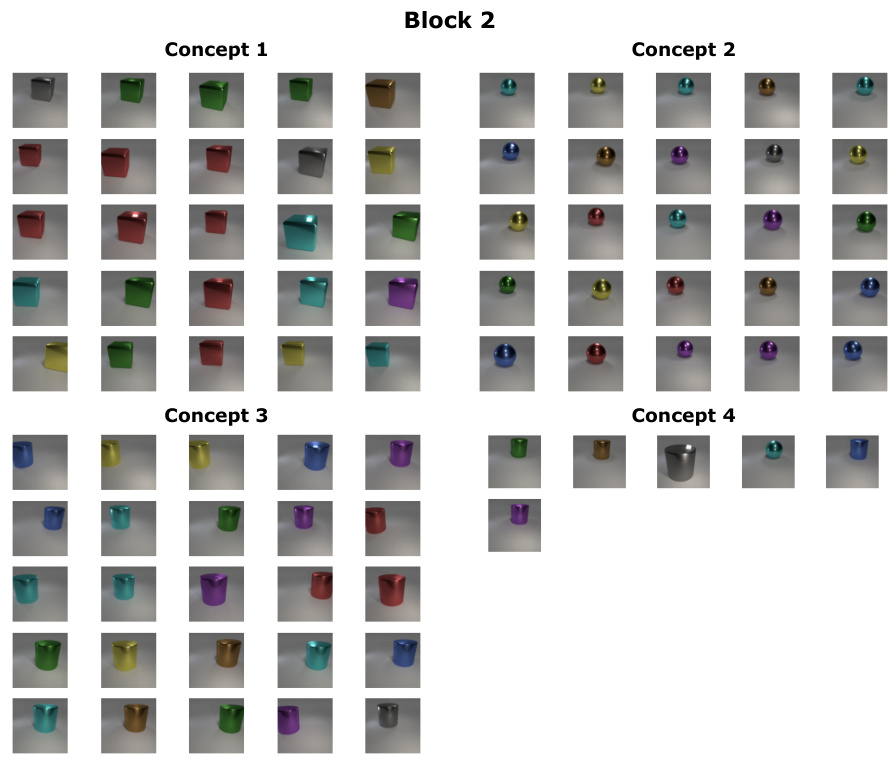

This figure shows the concepts learned by the Neural Concept Binder (NCB) for Block 2 when trained on the CLEVR-Easy dataset. It presents example images for each concept, allowing for visual inspection of what features each concept represents. The caption highlights that Block 2 primarily encodes shape information, though one concept appears ambiguous, suggesting potential issues with the learned concept representation.

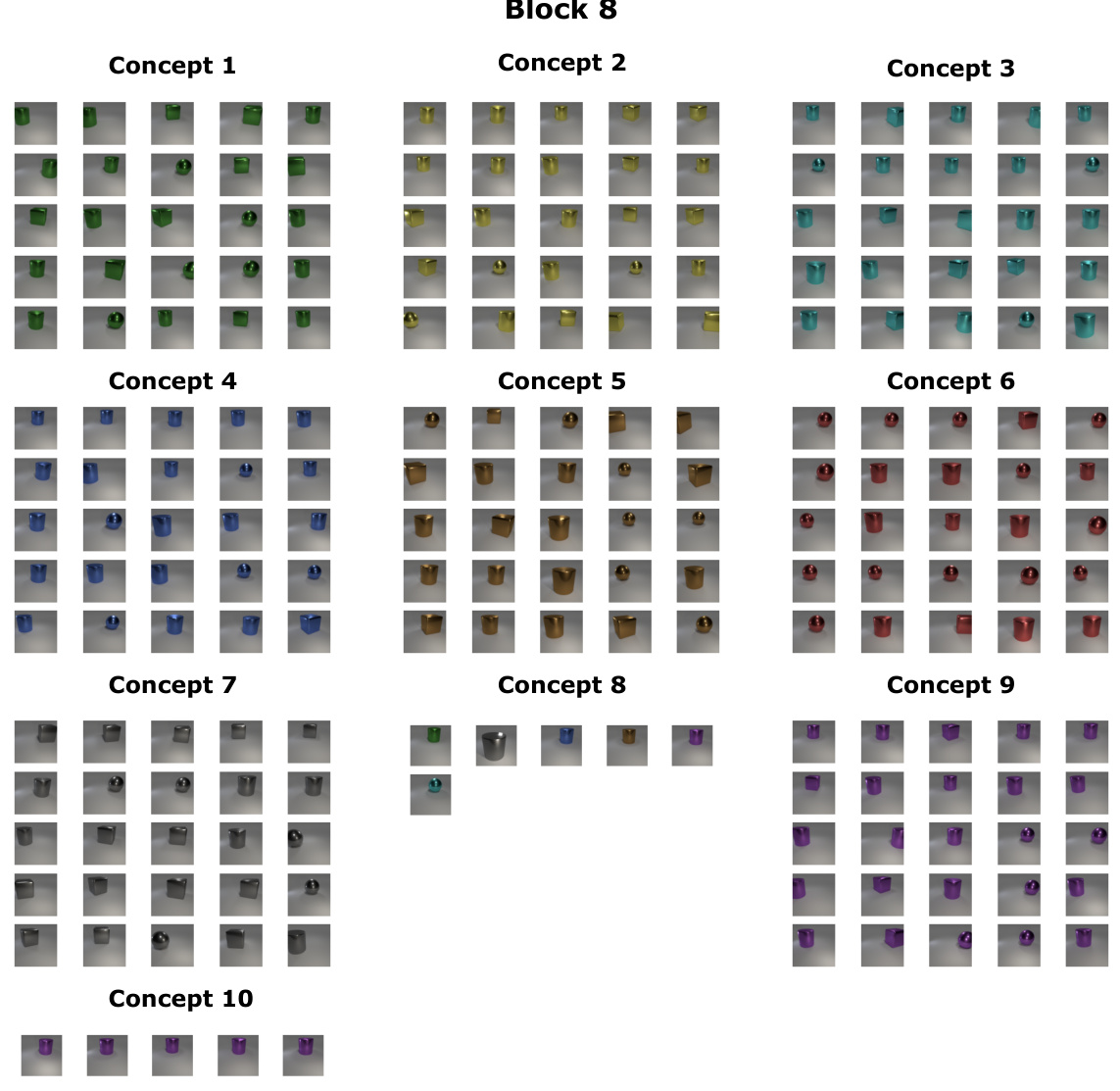

This figure shows the results of implicit inspection of concepts from block 8 of the Neural Concept Binder (NCB) model trained on the CLEVR-Easy dataset. Each concept is represented by a grid of example images. The figure shows ten concepts identified by the model, with each concept represented by a set of images sharing similar visual characteristics. Concept 8 seems ambiguous, while concepts 9 and 10 both appear to represent the color purple, indicating a potential redundancy in the model’s representation.

More on tables

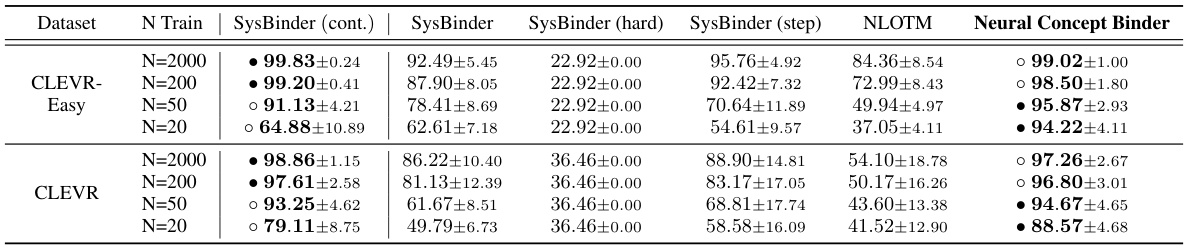

This table presents the results of classifying object properties using different continuous and discrete concept encodings. The experiment varied the amount of training data (N Train) provided to a classifier for four different encodings: SysBinder (continuous), SysBinder, SysBinder (hard), SysBinder (step), and NLOTM. The Neural Concept Binder (NCB) results are also shown. The best and second-best performing models for each training data size are highlighted in bold. This demonstrates the expressiveness of NCB’s encodings even with limited training data.

This table compares several concept learning approaches across seven criteria: unsupervised learning capability, ability to handle object-level and factor-level concepts, use of continuous vs. discrete encodings, and the inspectability and revisability of the learned concepts. It highlights the Neural Concept Binder’s (NCB) advantages in offering all seven features, unlike other methods.

This table compares several existing concept learning methods along seven criteria: unsupervised learning capability, ability to handle object-level and factor-level concepts, use of continuous or discrete concept encodings, and the inspectability and revisability of learned concepts. It highlights the unique strengths of the Neural Concept Binder (NCB) method introduced in the paper by showing that it satisfies all seven criteria, unlike other approaches.

This table presents the results of classifying object properties using different continuous and discrete concept encodings. The experiment varies the number of training samples provided to the classifier (N_Train = 2000, 200, 50, 20) and compares the performance of NCB with several baselines: SysBinder (continuous), SysBinder, SysBinder (hard), SysBinder (step), and NLOTM. The accuracy of the classification is shown for both the CLEVR-Easy and CLEVR datasets. The best and second-best performing methods for each condition are highlighted.

This table presents an ablation study on the Neural Concept Binder (NCB) by varying the training epochs of the soft binder, removing the hyperparameter grid search optimization for HDBSCAN clustering, and replacing HDBSCAN with k-means clustering. The impact of these changes on the accuracy of classifying object attributes using NCB’s concept representations is evaluated on the CLEVR dataset with various training set sizes. The leftmost column shows the baseline NCB performance, while the remaining columns illustrate the effects of the changes.

This table presents the results of a classification experiment using different continuous and discrete concept encodings. The goal is to show that NCB’s discrete encodings are expressive, even when limited training data is available. The table compares NCB’s performance against several other methods (SysBinder (cont.), SysBinder, SysBinder (hard), SysBinder (step), and NLOTM) across different training set sizes (N=2000, 200, 50, 20) for both CLEVR-Easy and CLEVR datasets. The best and second-best performing methods for each condition are highlighted.

This table presents the results of a classification experiment designed to evaluate the expressiveness of NCB’s concept encodings, even under an information bottleneck. Different continuous and discrete encoding methods are compared, including SysBinder (continuous), SysBinder (hard), SysBinder (step), NLOTM, and NCB. The classifier was trained with varying amounts of training data (2000, 200, 50, and 20 encodings) for both the CLEVR-Easy and CLEVR datasets. The accuracy of object property classification demonstrates that NCB’s discrete encodings are highly expressive even with limited training data and outperform other discrete methods.

This table presents the results of classifying object properties using different continuous and discrete concept encodings. The experiment varied the amount of training data (number of encodings) used for the classifier. The performance of NCB’s concept encodings is compared against several baselines, including variations of the SysBinder model and the NLOTM model. The table shows that NCB achieves high accuracy even with limited training data, demonstrating the expressiveness of its encodings despite the information bottleneck.

Full paper#