↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The sheer number of large language models (LLMs) with diverse parameter scales and vocabularies presents significant challenges, particularly concerning cost-effective optimization for specific applications (like instruction following or removing sensitive information). Existing methods address each model individually, increasing training costs. This research tackles this problem.

This paper proposes Cross-model Control (CMC), a method to improve multiple LLMs using a single, small, portable model trained alongside a frozen template LLM. This approach leverages the similarity of logit shifts before and after fine-tuning across models, enabling the small model to effectively alter the output logits of other LLMs. A novel token mapping strategy (PM-MinED) further extends the method’s applicability to models with different vocabularies. CMC demonstrates significant performance improvements in instruction tuning and unlearning tasks, achieving remarkable efficiency gains and reduced computational requirements.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is highly important because it presents a novel and efficient method, CMC, for improving multiple large language models (LLMs) simultaneously. This addresses the significant cost and resource constraints often faced in fine-tuning LLMs, offering a practical solution to a prevalent challenge in the field. The introduction of a portable tiny language model and token mapping strategy (PM-MinED) offers new avenues for cross-model optimization and parameter-efficient model enhancement. The findings contribute directly to ongoing research on LLM optimization, instruction tuning, and unlearning, potentially leading to more efficient and effective LLMs across diverse applications.

Visual Insights#

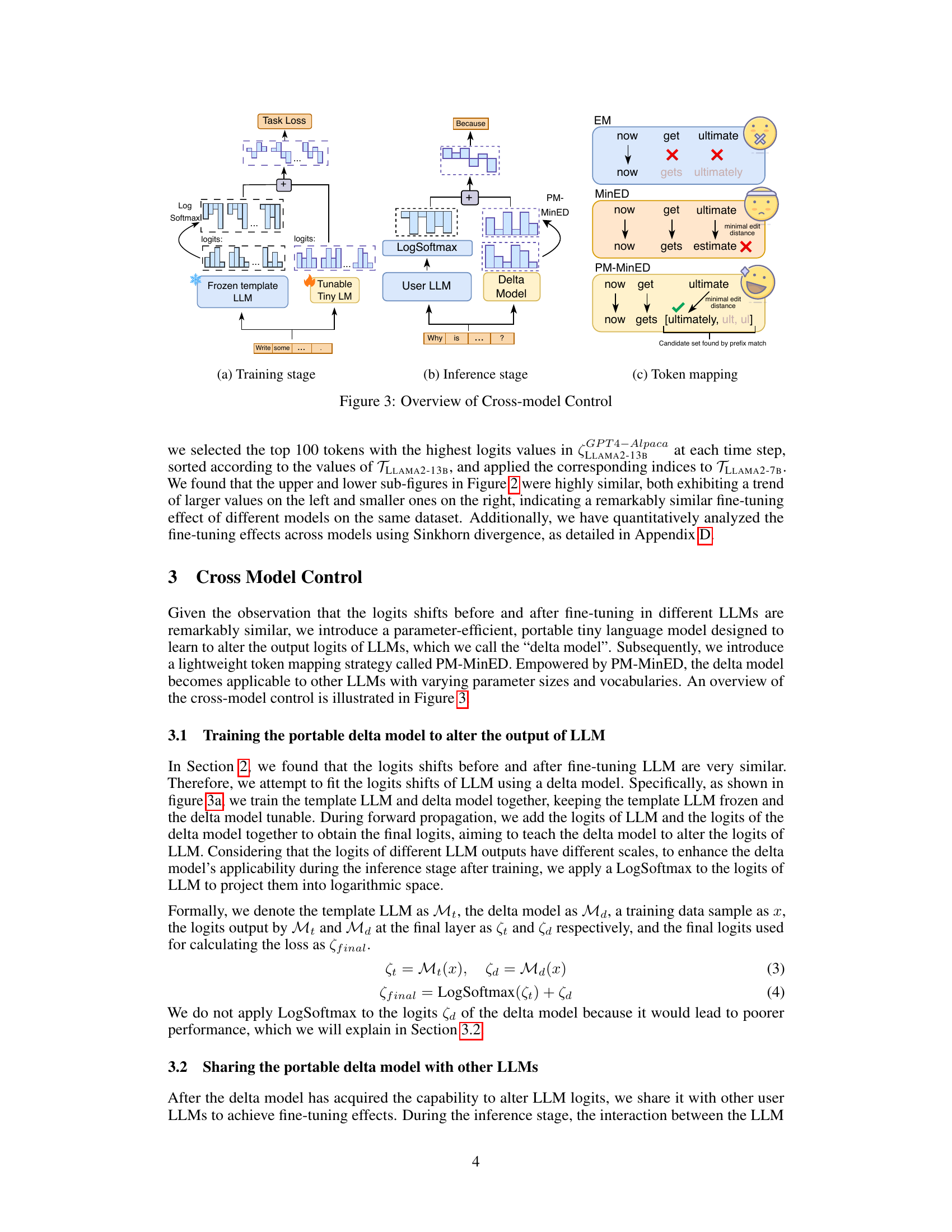

This figure illustrates the core idea of Cross-model Control (CMC). A single, small portable tiny language model is trained alongside a larger template language model. After training, the tiny model’s ability to modify the output logits is shared with other user LLMs, regardless of their parameter scales or vocabularies. This allows efficient improvement of multiple models in a single training process.

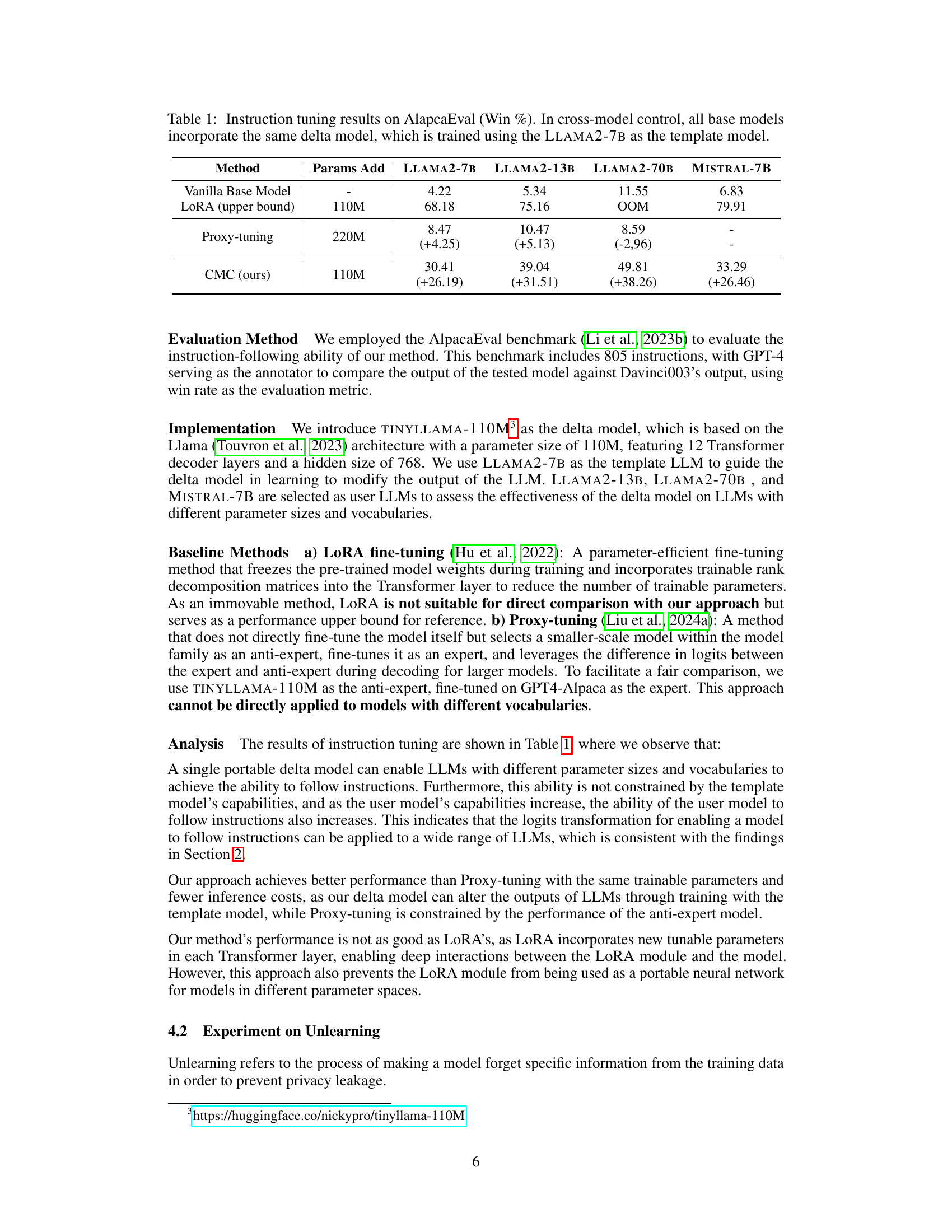

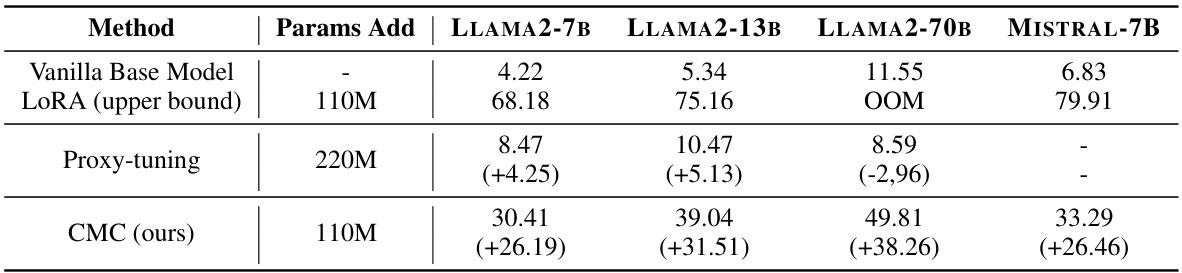

This table presents the results of instruction tuning experiments using the AlpacaEval benchmark. It compares the performance (Win %) of four large language models (LLMs): LLAMA2-7B, LLAMA2-13B, LLAMA2-70B, and MISTRAL-7B. The results are shown for three different methods: a vanilla base model, LORA (a parameter-efficient fine-tuning technique), and the proposed Cross-model Control (CMC) method. CMC uses a shared, smaller ‘delta model’ trained on LLAMA2-7B to improve multiple LLMs simultaneously. The numbers in parentheses show the improvement achieved by each method over the Vanilla Base Model.

In-depth insights#

Cross-Model Control#

The concept of ‘Cross-Model Control’ presents a novel approach to enhance multiple Large Language Models (LLMs) simultaneously. Instead of individually fine-tuning each LLM, which is resource-intensive, a single, lightweight “delta model” is trained to modify the output logits of diverse LLMs. This delta model learns to capture the commonalities in the logit shifts observed during individual LLM fine-tuning, enabling it to transfer optimization outcomes effectively. A key innovation is the PM-MinED token mapping strategy, which addresses the challenge of applying the delta model to LLMs with different vocabularies. By leveraging the inherent similarities in fine-tuning effects, this approach promises significant cost savings and efficiency gains, making it a valuable technique for LLM developers facing constraints on data and computational resources. The effectiveness is demonstrated on instruction tuning and unlearning tasks, highlighting its broad applicability and potential impact on improving various LLM capabilities.

Portable Tiny LM#

The concept of a “Portable Tiny LM” within the context of a large language model (LLM) research paper is intriguing. It suggests a smaller, more efficient model trained to modify the output logits of larger, more resource-intensive LLMs. This approach addresses the high cost and computational demands associated with fine-tuning massive LLMs for various downstream tasks. The “portability” aspect highlights its adaptability across LLMs with different architectures and vocabularies. This is achieved through innovative token mapping strategies such as PM-MinED, designed to bridge vocabulary discrepancies between the tiny model and the target LLMs. This modularity enables a single training process to enhance performance across diverse LLMs, resulting in significant cost savings and resource efficiency. The effectiveness of this method relies heavily on the observation of similar logit shifts in various LLMs after fine-tuning, suggesting a shared underlying mechanism that the tiny model can effectively capture and leverage to improve performance.

Token Mapping#

The effectiveness of cross-model control hinges on robust token mapping between the portable tiny language model and the larger user LLMs. A naive approach of direct matching would severely limit applicability due to vocabulary discrepancies across different models. The paper cleverly addresses this by proposing PM-MinED, a strategy that combines prefix matching with minimum edit distance. Prefix matching ensures semantic relevance by prioritizing tokens with shared prefixes, minimizing the risk of mismatched tokens with similar spelling but different meaning. Minimum edit distance is then applied to the subset of prefix-matched candidates, to find the most similar token. This hybrid approach enhances the accuracy and efficiency of mapping across diverse LLMs, significantly improving the overall performance of the cross-model control framework.

Instruction Tuning#

Instruction tuning, a crucial technique in adapting large language models (LLMs) for real-world applications, focuses on fine-tuning pre-trained models to better understand and follow user instructions. It bridges the gap between general language capabilities and specific task performance. The process involves training the LLM on a dataset of instruction-response pairs, enabling it to learn the mapping between instructions and appropriate outputs. Success hinges on the quality and diversity of the training data. A well-curated dataset with varied instructions and accurate responses is key to achieving high-quality performance. However, instruction tuning is computationally expensive, especially for large models, and it can be challenging to ensure generalization to unseen instructions. Techniques like low-rank adaptation (LoRA) aim to mitigate these challenges by optimizing only a subset of model parameters, reducing computational costs and preventing overfitting. Furthermore, ongoing research explores efficient methods to leverage instruction tuning outcomes across different LLMs, reducing the need for retraining each model individually. The effectiveness of instruction tuning is consistently evaluated through benchmarks that assess its ability to correctly interpret and respond to complex and nuanced instructions.

Unlearning Limits#

The heading ‘Unlearning Limits’ suggests an exploration of the boundaries and challenges inherent in the process of removing or mitigating learned information from large language models (LLMs). A thoughtful analysis would delve into the technical difficulties of unlearning, such as the potential for incomplete removal of unwanted information or the unintended consequences of such modifications on the model’s overall performance. Ethical implications are also critical; the paper might examine the difficulty of completely erasing sensitive data, ensuring its absence from future outputs, and maintaining user privacy. Practical limitations on the feasibility and scalability of unlearning methods within existing LLM architectures could also be explored, considering computational costs and the potential for retraining complexities. The discussion should also acknowledge that data biases embedded during initial training are very difficult to erase and might require extensive retraining or architectural modifications. Overall, a comprehensive look at ‘Unlearning Limits’ requires a multi-faceted perspective, examining both the technical and societal challenges of removing unwanted knowledge from powerful and increasingly pervasive LLMs.

More visual insights#

More on figures

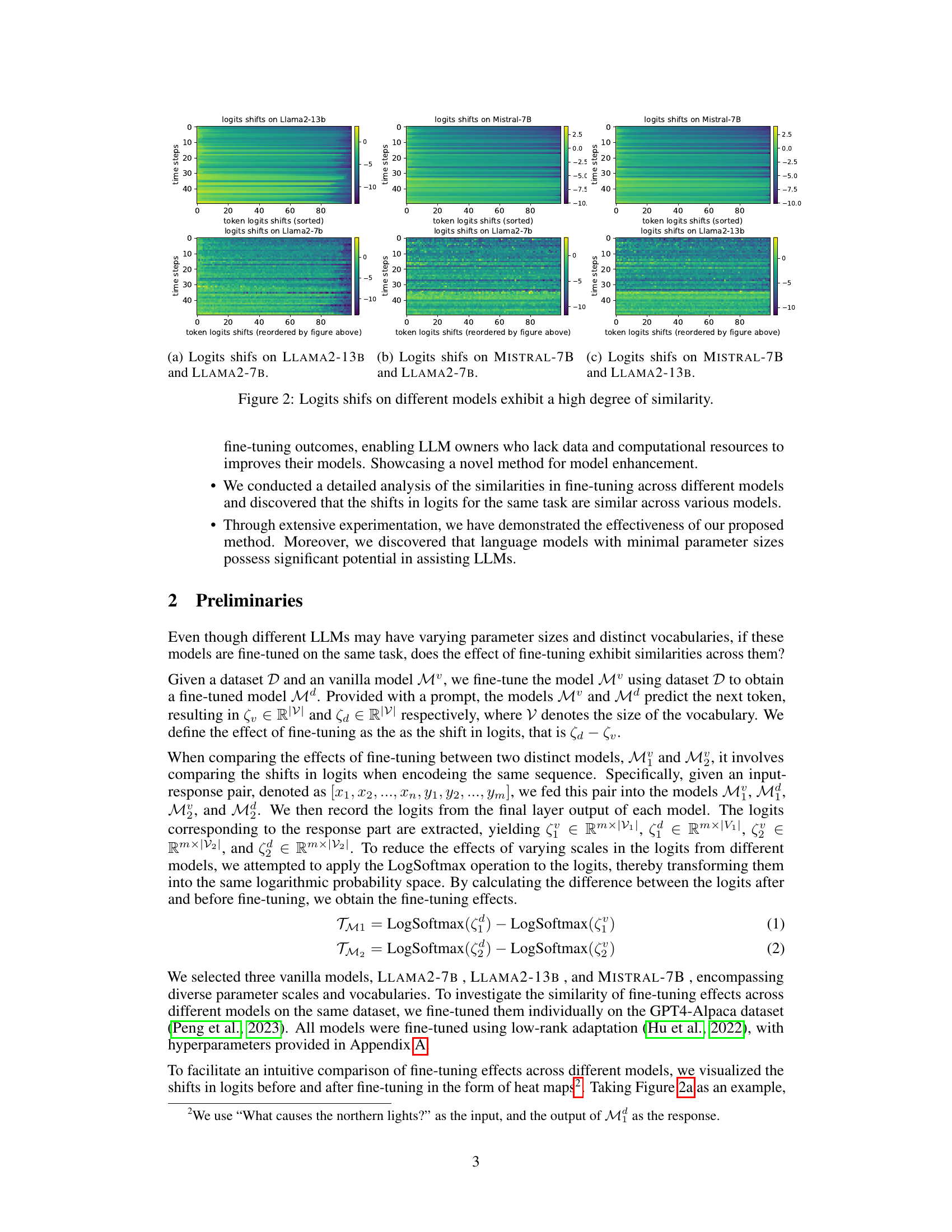

This figure shows heatmaps visualizing the logit shifts on different LLMs (Llama2-7b, Llama2-13b, and Mistral-7B) before and after fine-tuning. The high similarity across models despite differences in parameter scales and vocabularies supports the paper’s claim that fine-tuning effects are remarkably similar across different LLMs. The heatmaps represent the change in logit values for each token after fine-tuning compared to before fine-tuning, providing visual evidence of the consistent patterns across different models.

This figure illustrates the architecture and workflow of the Cross-model Control (CMC) method. Panel (a) shows the training stage, where a frozen template LLM and a tunable tiny language model (delta model) are trained together. The delta model learns to adjust the logits of the template LLM to achieve desired outcomes (e.g., instruction following or unlearning). Panel (b) shows the inference stage, where the trained delta model interacts with other user LLMs to modify their logits output. Panel (c) details the token mapping strategy (PM-MinED) that handles the differences in vocabulary between the delta model and user LLMs, focusing on finding the closest semantic match for improved accuracy.

This figure shows the impact of the strength coefficient α on the performance of the model in instruction tuning and unlearning tasks. The left subplot (a) displays the AlpacaEval win rate for instruction tuning across different epochs (2, 4, and 8) at varying α values. The right subplot (b) presents the ROUGE scores for the unlearning task, broken down by dataset subset (Real Authors, Real World, Retain, and Forget) with varying α values. The plots illustrate how adjusting α affects the balance between overfitting and underfitting during training and impacts the model’s performance in unlearning sensitive information.

More on tables

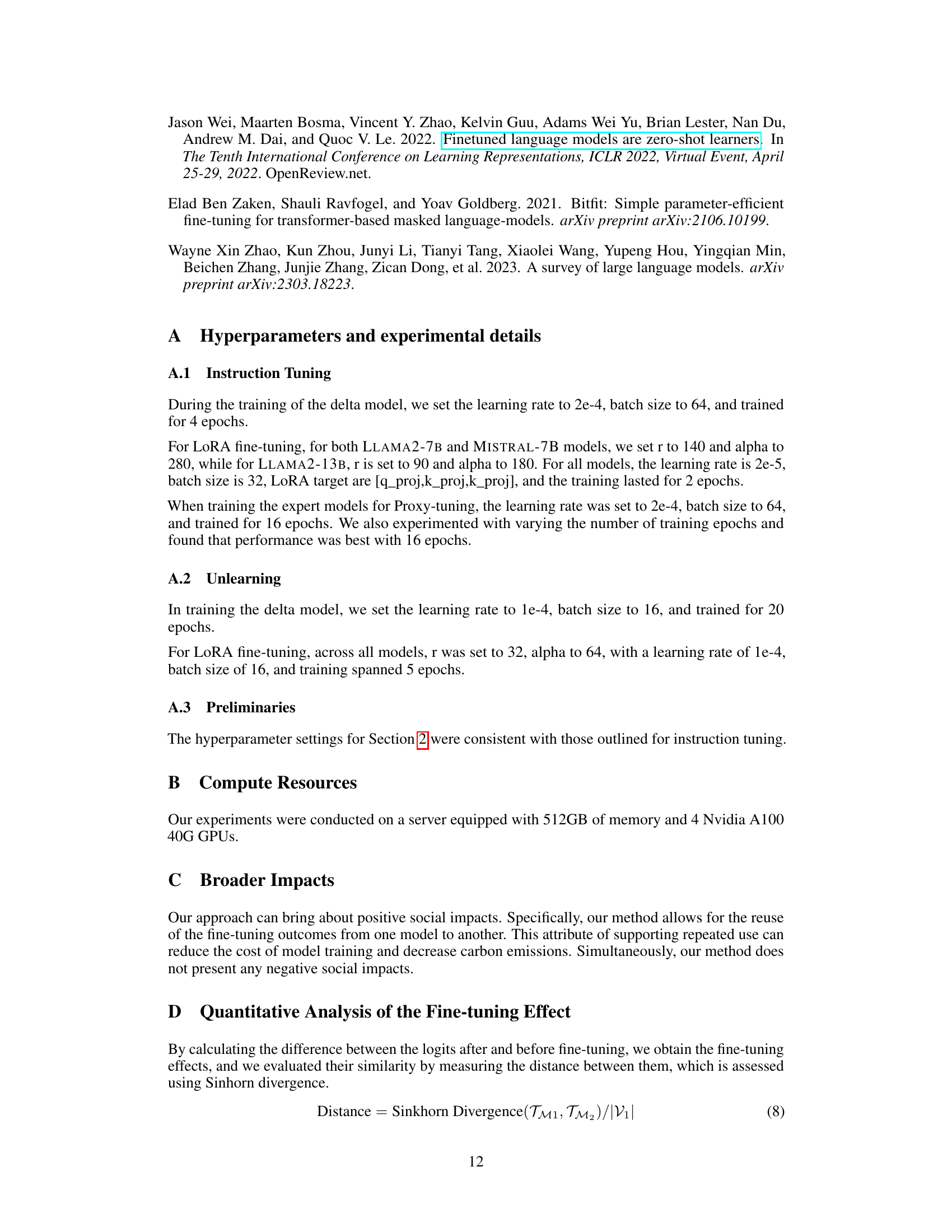

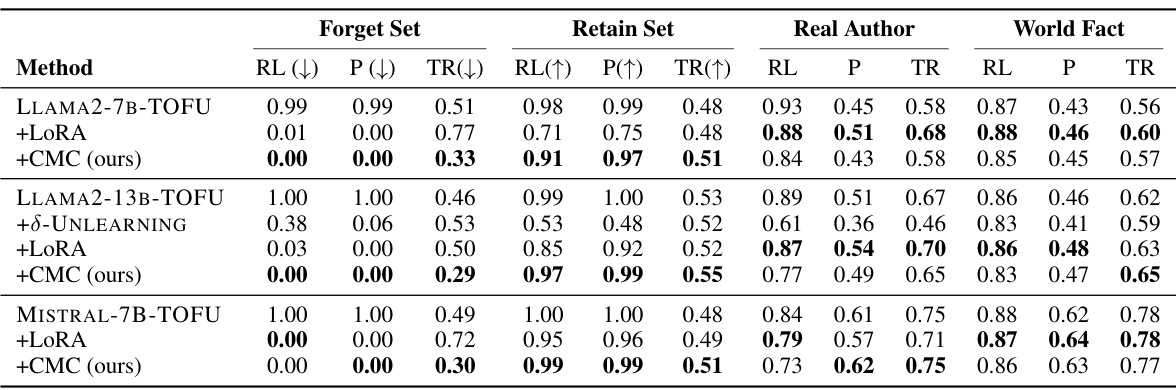

This table presents the results of the unlearning experiments using the TOFU benchmark. It compares various methods (vanilla model, LoRA, 8-UNLEARNING, and the proposed CMC method) across three LLMs (LLAMA2-7B, LLAMA2-13B, and MISTRAL-7B) in their ability to forget information from a forget set while retaining information from a retain set. The performance is measured using ROUGE-L (recall-oriented understanding for gisting evaluation), Probability (likelihood of correct answers), and Truth Ratio (ratio of correct to incorrect answers). The results show how effectively each method prevents the model from outputting information from the forget set while maintaining accuracy on the retain set and other knowledge domains. Bold values indicate better performance.

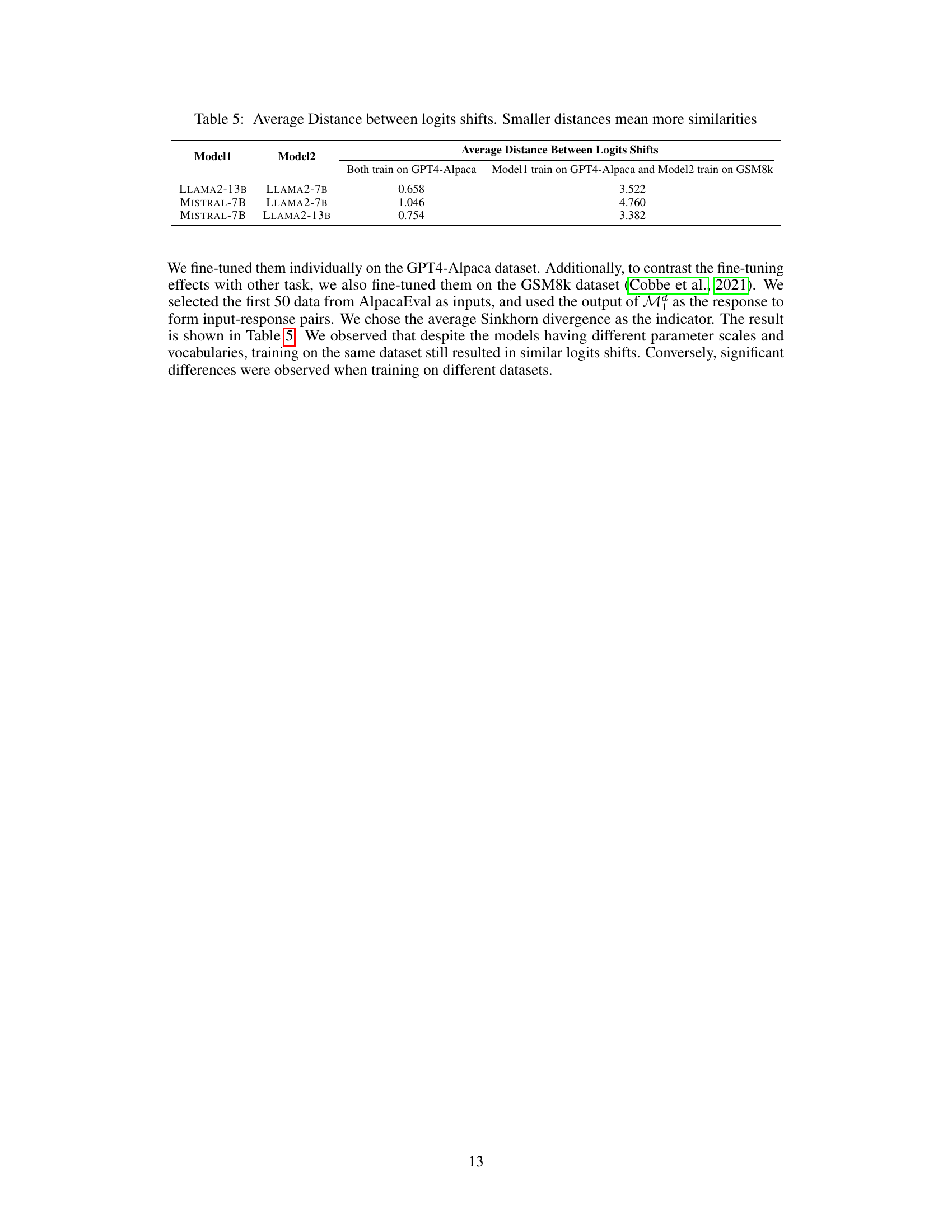

This table presents the results of instruction tuning experiments using different sizes of delta models (15M, 42M, and 110M parameters). The win rate (in percentage) on the first 50 data points of the AlpacaEval benchmark is shown for four different LLMs (LLAMA2-7B, LLAMA2-13B, LLAMA2-70B, and MISTRAL-7B). The results demonstrate the impact of the delta model’s size on the performance of instruction tuning across various LLMs.

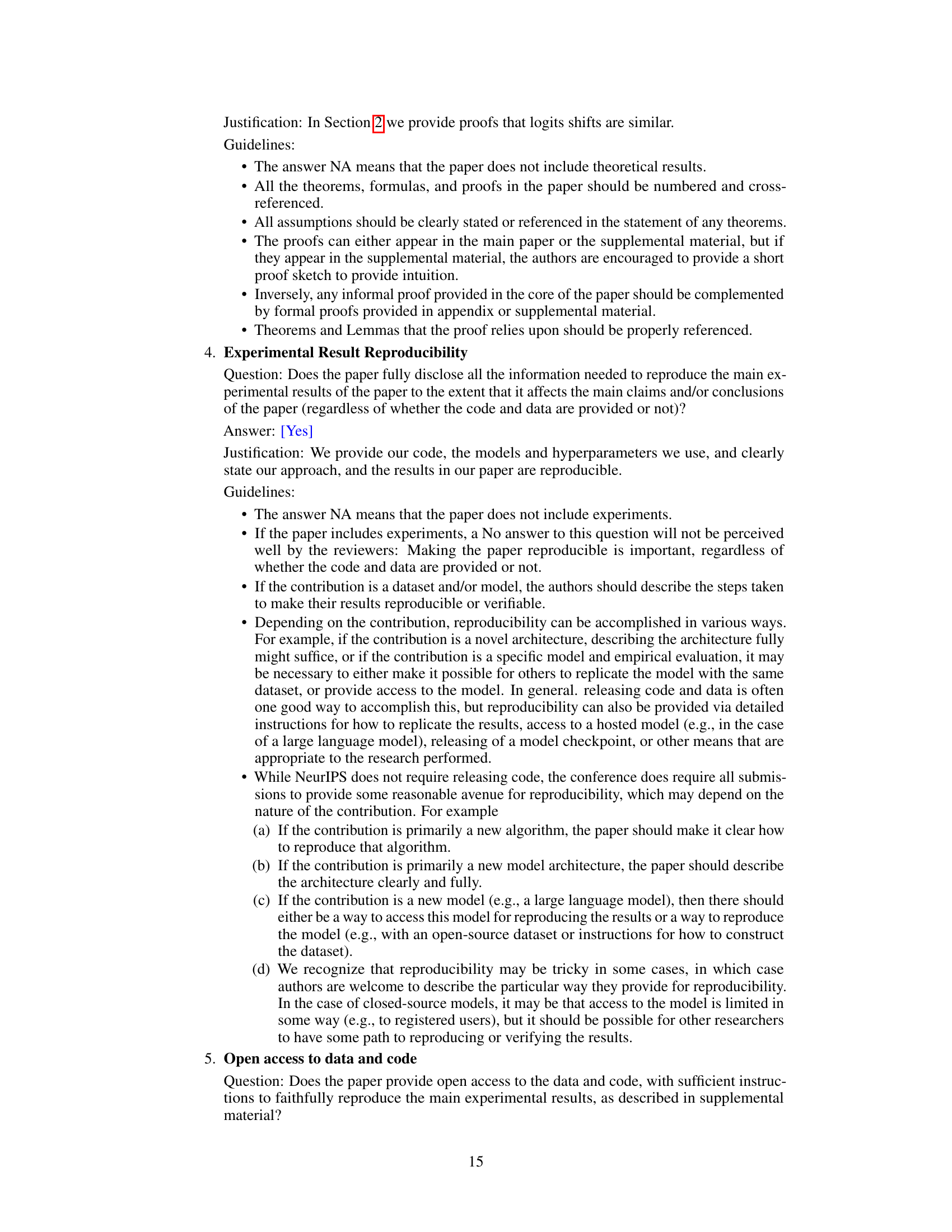

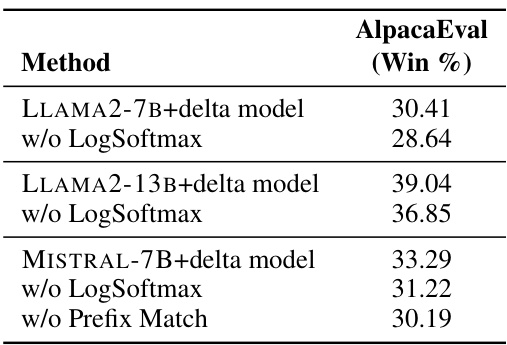

This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of removing LogSoftmax and prefix matching from the Cross-model Control (CMC) method. The AlpacaEval (Win %) metric is used to measure the performance of three different LLMs (LLAMA2-7B, LLAMA2-13B, and MISTRAL-7B) under different conditions: with both LogSoftmax and prefix matching (baseline), without LogSoftmax, and without prefix matching. The results show the performance degradation when either or both of these components are removed from CMC, highlighting their importance to the method’s effectiveness.

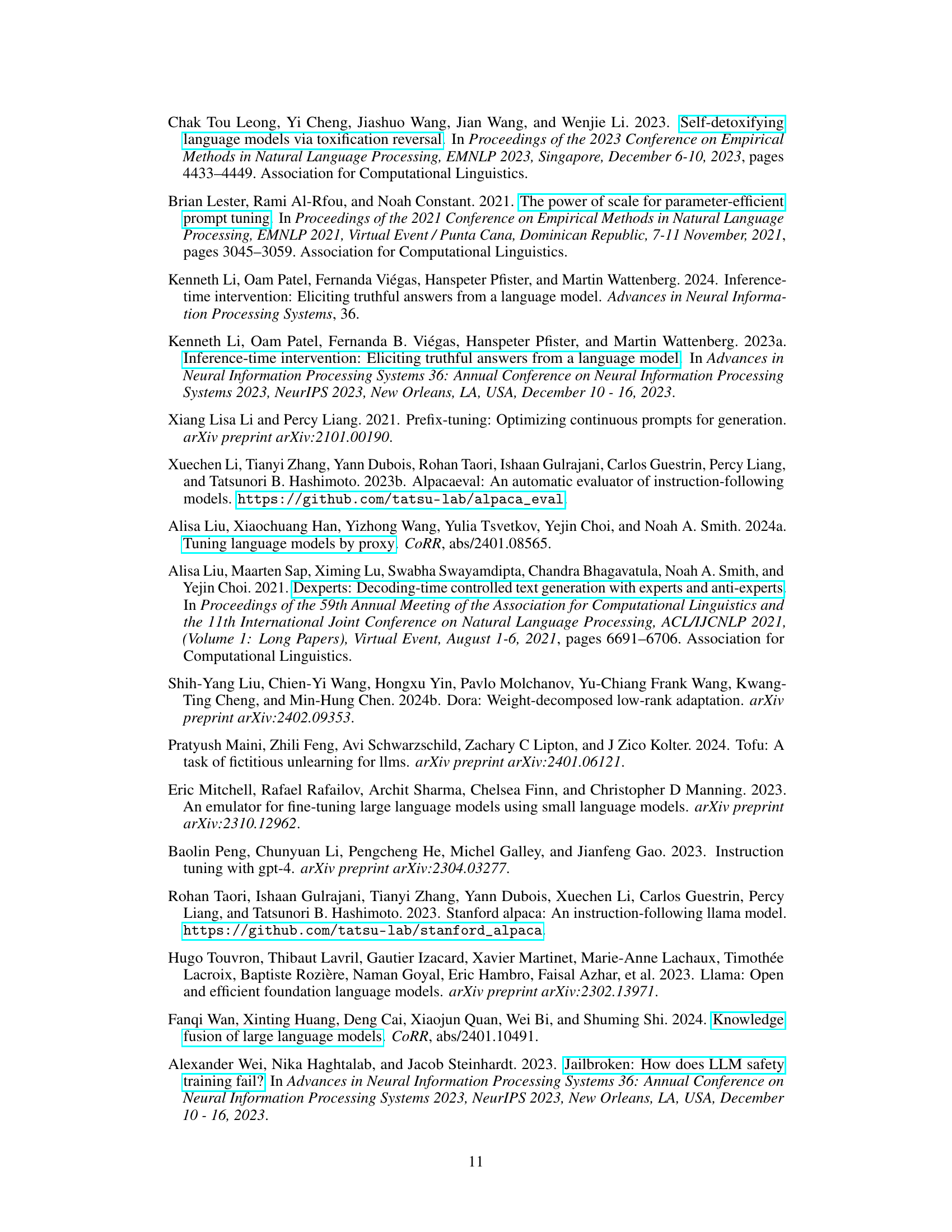

This table presents a quantitative analysis of the similarity in fine-tuning effects across different LLMs. It shows the average Sinkhorn divergence between the logits shifts of various model pairs. The divergence is calculated both when all models are fine-tuned on the same dataset (GPT4-Alpaca) and when one model is fine-tuned on GPT4-Alpaca and another on a different dataset (GSM8k). Lower divergence values indicate higher similarity in fine-tuning effects.

Full paper#