↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are computationally expensive, limiting their applications. Deep learning offers potential acceleration but existing methods fall short in leveraging the richness of dynamical information. They often fail to perform well in various downstream tasks, such as transition path sampling and trajectory upsampling. This makes it difficult to fully exploit MD data for deeper scientific understanding and development.

The paper introduces MDGEN, a generative model that directly learns the full molecular trajectory from data. This allows for various applications such as forward simulation, interpolation, upsampling, and dynamics-conditioned molecular design (inpainting). MDGEN demonstrates these capabilities on tetrapeptide simulations and shows promising scaling up to protein monomers. The method significantly accelerates calculations with minimal loss in accuracy, addressing various inverse problems that are difficult to solve with conventional methods. This showcases its potential to greatly enhance MD studies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in molecular dynamics and machine learning because it introduces a novel generative modeling paradigm. It provides efficient surrogate models for MD simulations and addresses various downstream tasks like forward simulation and molecular design, previously challenging or impossible. This offers significant speedups over traditional MD simulations, unlocks new avenues of research, and potentially revolutionizes drug discovery and material science.

Visual Insights#

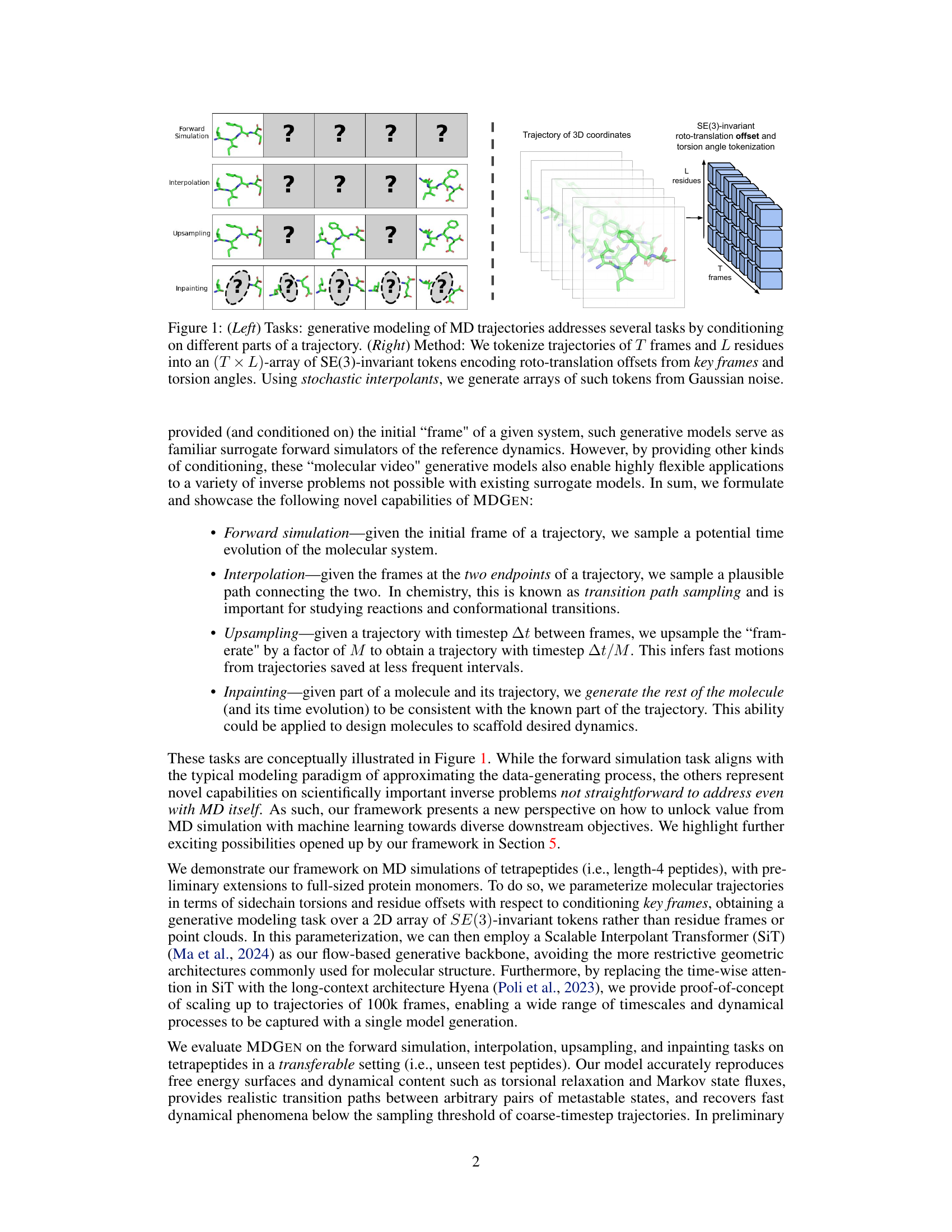

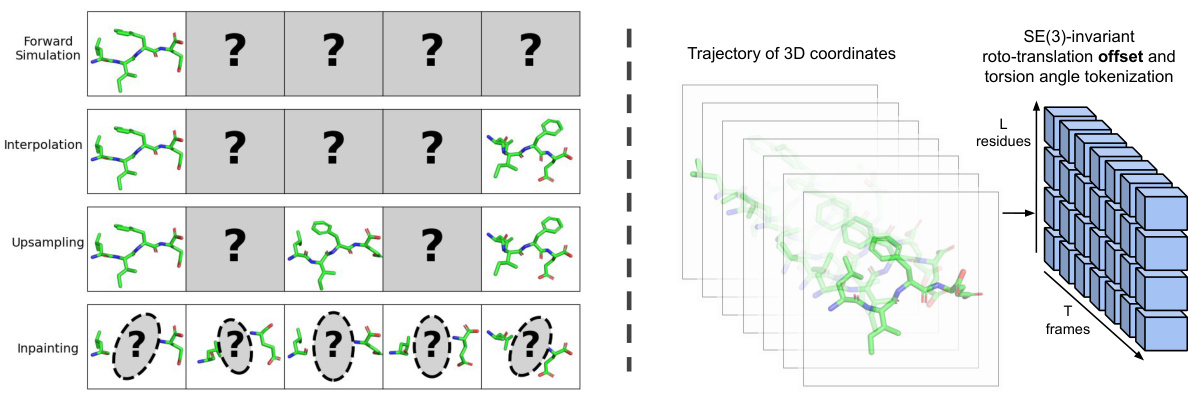

This figure illustrates the tasks and methods used in generative modeling of molecular dynamics trajectories. The left panel shows four different tasks: forward simulation, interpolation, upsampling, and inpainting. Each task involves conditioning the generative model on different parts of a trajectory to achieve different goals. The right panel illustrates the method used in this generative modeling approach. It explains that trajectories are tokenized into an array of SE(3)-invariant tokens, representing rotations, translations, and torsion angles. These tokens are then used as inputs to a stochastic interpolant-based generative model, which produces new arrays of tokens to generate trajectories.

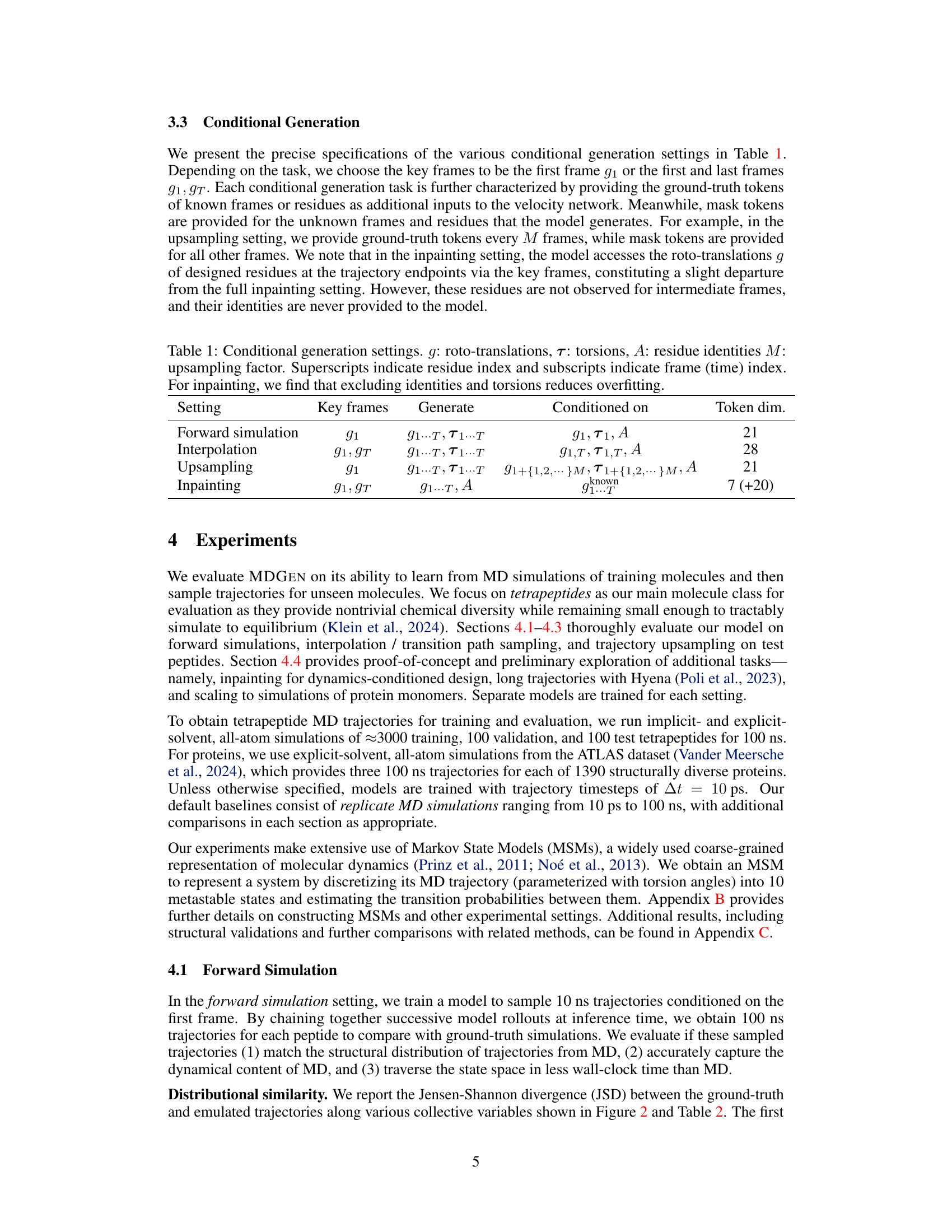

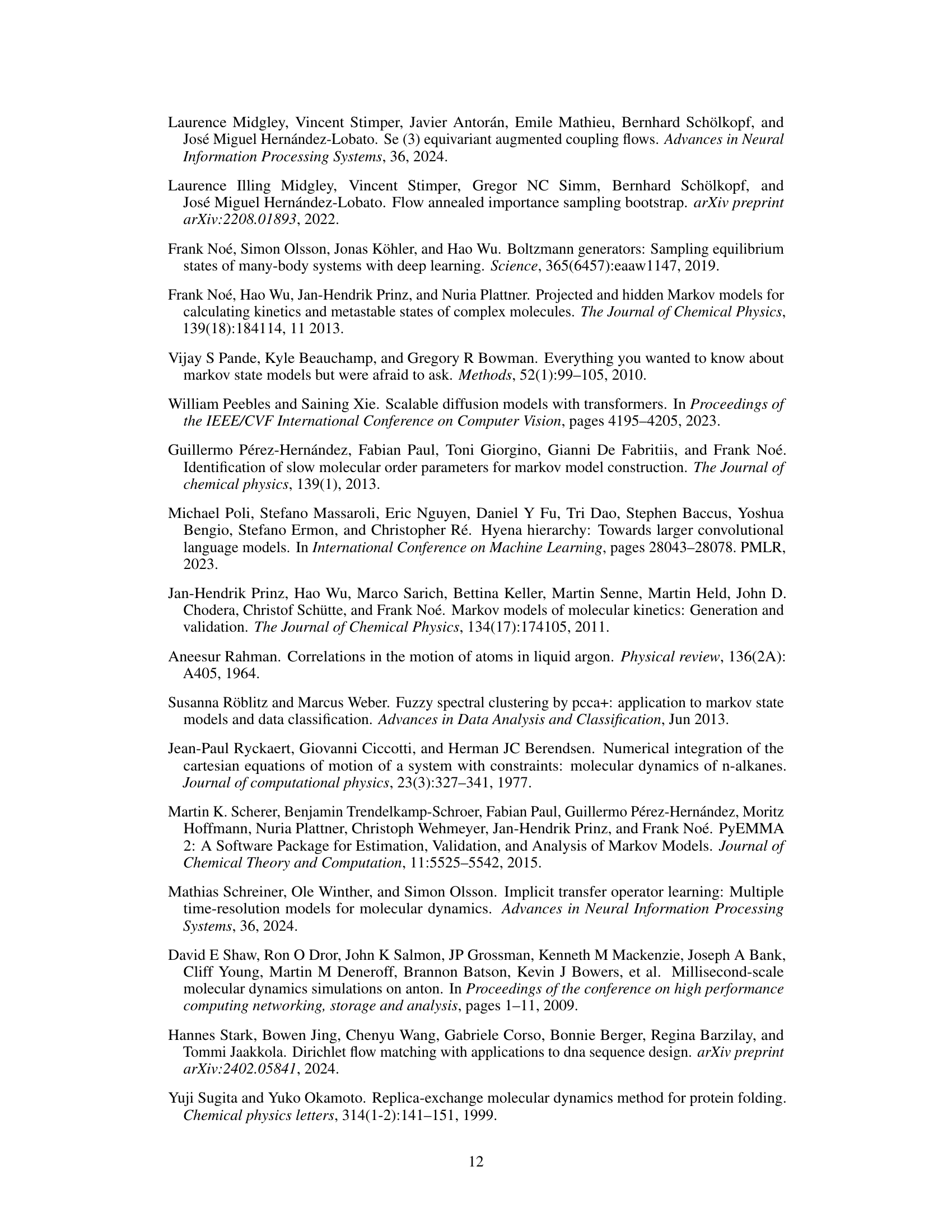

This table details the different conditional generation settings used in the MDGEN model. It specifies the key frames used as conditioning input, the parts of the trajectory that the model generates, other conditioning information, and the dimensionality of the tokens used for each task (forward simulation, interpolation, upsampling, and inpainting). Note that for inpainting, excluding residue identities and torsions improves performance, reducing overfitting.

In-depth insights#

MDGen: Core Idea#

MDGen’s core idea revolves around generative modeling of full molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories as time-series data. Unlike previous methods focusing on transition densities or equilibrium distributions, MDGen directly learns to generate entire trajectories. This approach is powerful because it allows for flexible adaptation to various downstream tasks. By conditioning the model on different parts of a trajectory (e.g., initial frame for forward simulation, endpoints for interpolation), MDGen can perform tasks not easily achievable with traditional MD or other surrogate models. The key innovation lies in its ability to handle diverse inverse problems, such as transition path sampling and trajectory upsampling, showcasing the versatility of generative modeling for MD. Furthermore, the use of SE(3)-invariant tokens to represent molecular structures makes the model robust to changes in coordinate systems and readily scalable.

Generative Tasks#

The heading ‘Generative Tasks’ in a research paper likely refers to the various applications enabled by a generative model, focusing on its ability to produce novel data instances rather than just analysis. This section would delve into specific tasks achievable by leveraging the model’s generative capabilities. Forward simulation, for example, would involve using the model to predict the future trajectory of a system given an initial state. Interpolation might focus on filling in missing segments of a sequence by generating plausible intermediate data points. Upsampling could address the task of increasing the resolution or frequency of a data sequence. Inpainting might involve reconstructing missing parts of a data instance, potentially even across different modalities, given the remaining information. Molecular design could be a particularly interesting application within this context, potentially using the generative model to design molecules with specific dynamic properties. The effectiveness of the generative model across these tasks would likely be a major evaluation criterion in the paper. The description of the tasks and the evaluation metrics would be key to understanding the contributions of the research. Therefore, a good ‘Generative Tasks’ section would clearly define each task, explain the methodology used in employing the generative model for that task, and present a thorough evaluation of the results, showcasing the power and limitations of the generative approach.

Model Details#

The heading ‘Model Details’ in a research paper would typically delve into the architecture and specifics of the machine learning model used. This section is crucial for reproducibility and understanding the core methodology. A thoughtful analysis would expect a breakdown of the model’s components, such as the type of neural network (e.g., transformer, convolutional), its layers, activation functions, and any specialized modules employed. Detailed descriptions of hyperparameters and their choices are also essential, including any regularization techniques used. Furthermore, the explanation of how the model is trained (e.g., loss function, optimizer, training data) should be comprehensive. A thorough treatment would additionally justify the rationale for specific design decisions. Focus should be placed on the aspects of the model that are unique or innovative, differentiating it from existing approaches. The discussion should also acknowledge any limitations in the model architecture or training process, maintaining transparency and aiding critical assessment.

Evaluation Metrics#

A robust evaluation of generative models for molecular dynamics necessitates a multi-faceted approach. Core metrics should assess the accuracy of the generated trajectories in reproducing key statistical properties of the underlying molecular system. This includes comparing the distributions of various collective variables (e.g., torsion angles, dihedrals, distances), free energy surfaces, and Markov state models derived from both the generated and reference MD trajectories. Beyond simple statistical measures, the dynamical accuracy should be rigorously evaluated. This requires examining the autocorrelation functions of relevant degrees of freedom, assessing the accuracy in reproducing relaxation timescales and transition pathways between metastable states. Computational efficiency is also critical; evaluating the speed-up achieved by the generative model compared to traditional MD simulations is essential. Finally, metrics for evaluating structural accuracy (e.g., the rate of steric clashes or deviations in bond lengths) are important for ensuring the biophysical validity of the generated structures. A holistic approach using a combination of these metrics provides a comprehensive evaluation of generative models for molecular dynamics simulations.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore unconditional trajectory generation, eliminating reliance on key frames and unlocking broader applicability. Improving the model’s ability to handle larger systems like proteins and other molecules beyond peptides is crucial. Incorporating more diverse data types, such as experimental data or textual descriptions, could enhance model capabilities. Further investigation into dynamics-conditioned molecular design holds immense promise for applications in drug discovery and materials science. Exploring theoretical implications of trajectory modeling, particularly concerning non-equilibrium processes and the concept of time’s arrow at the microscopic level, warrants further research. Finally, addressing challenges in scaling to significantly longer trajectories and systems with varied degrees of freedom remains an important area for future exploration.

More visual insights#

More on figures

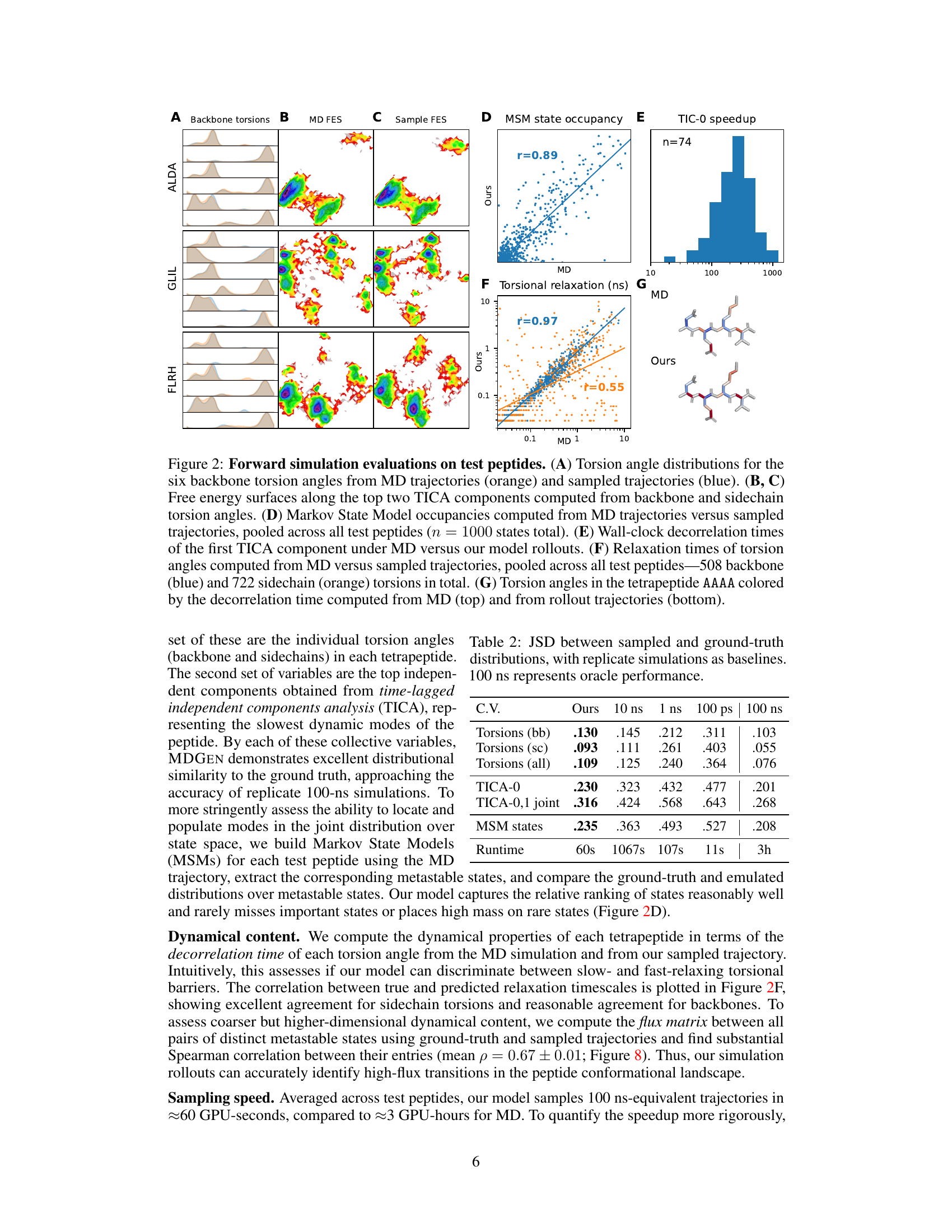

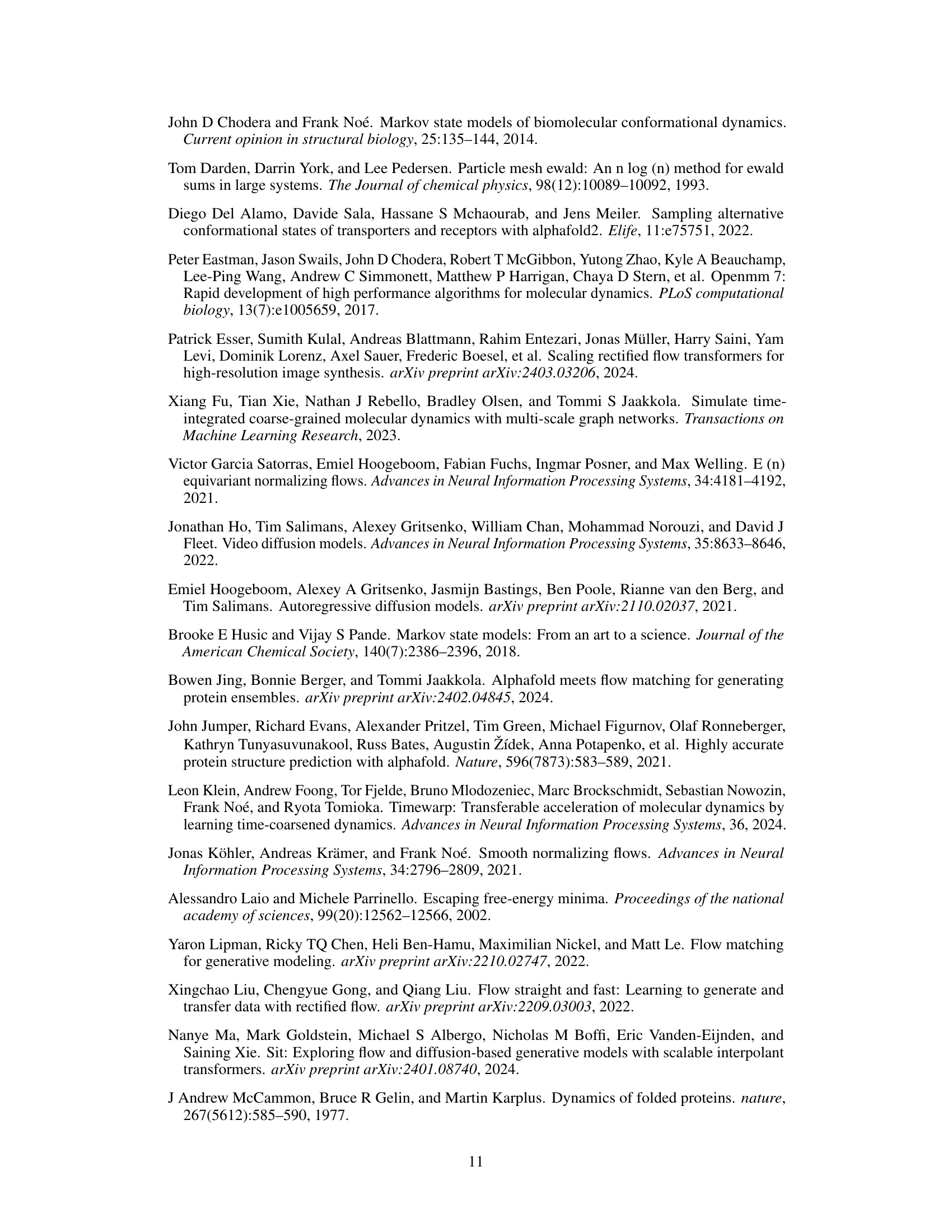

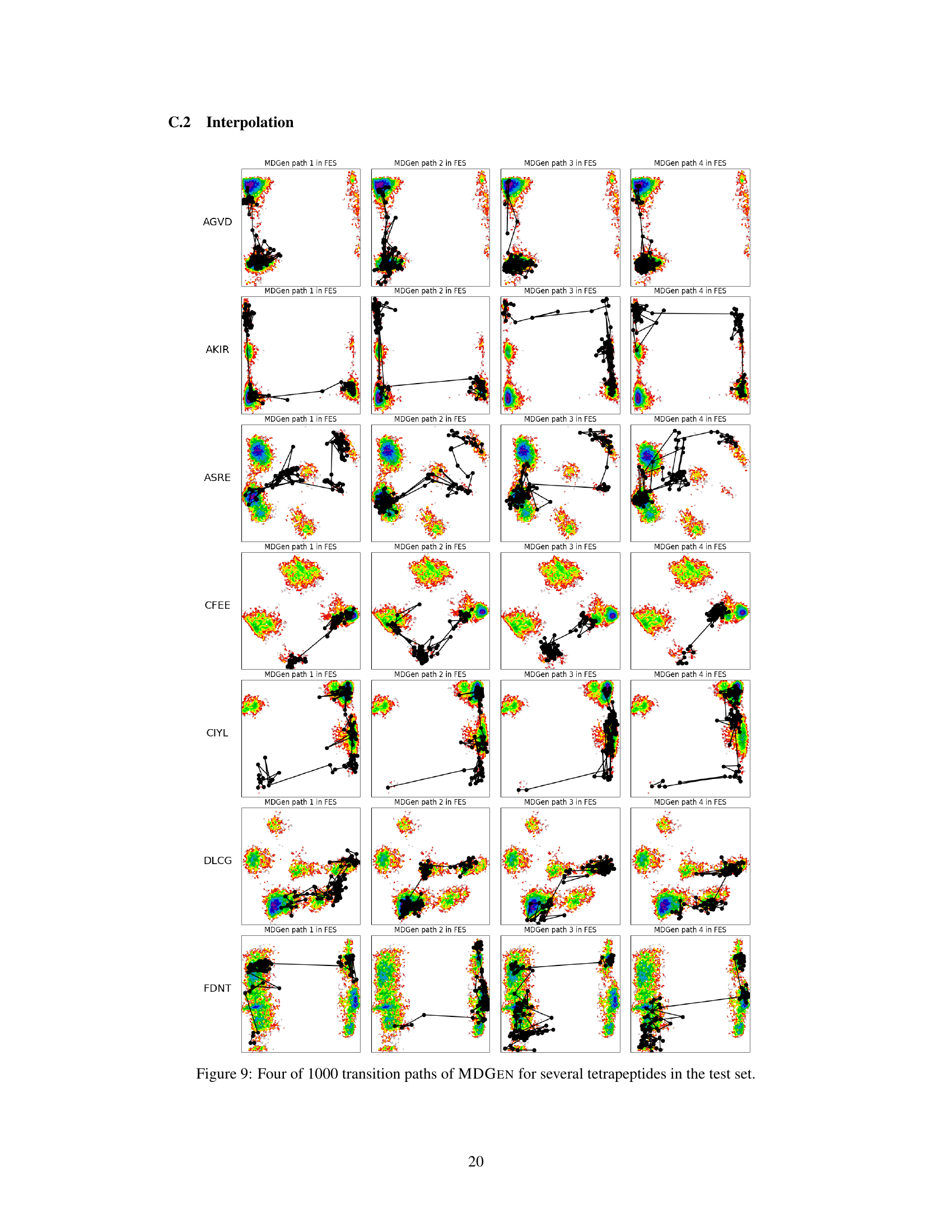

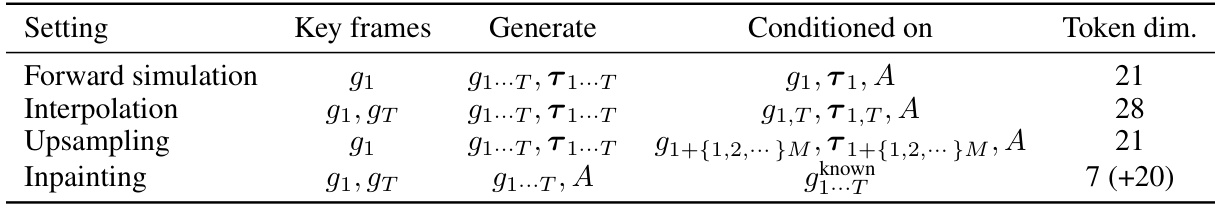

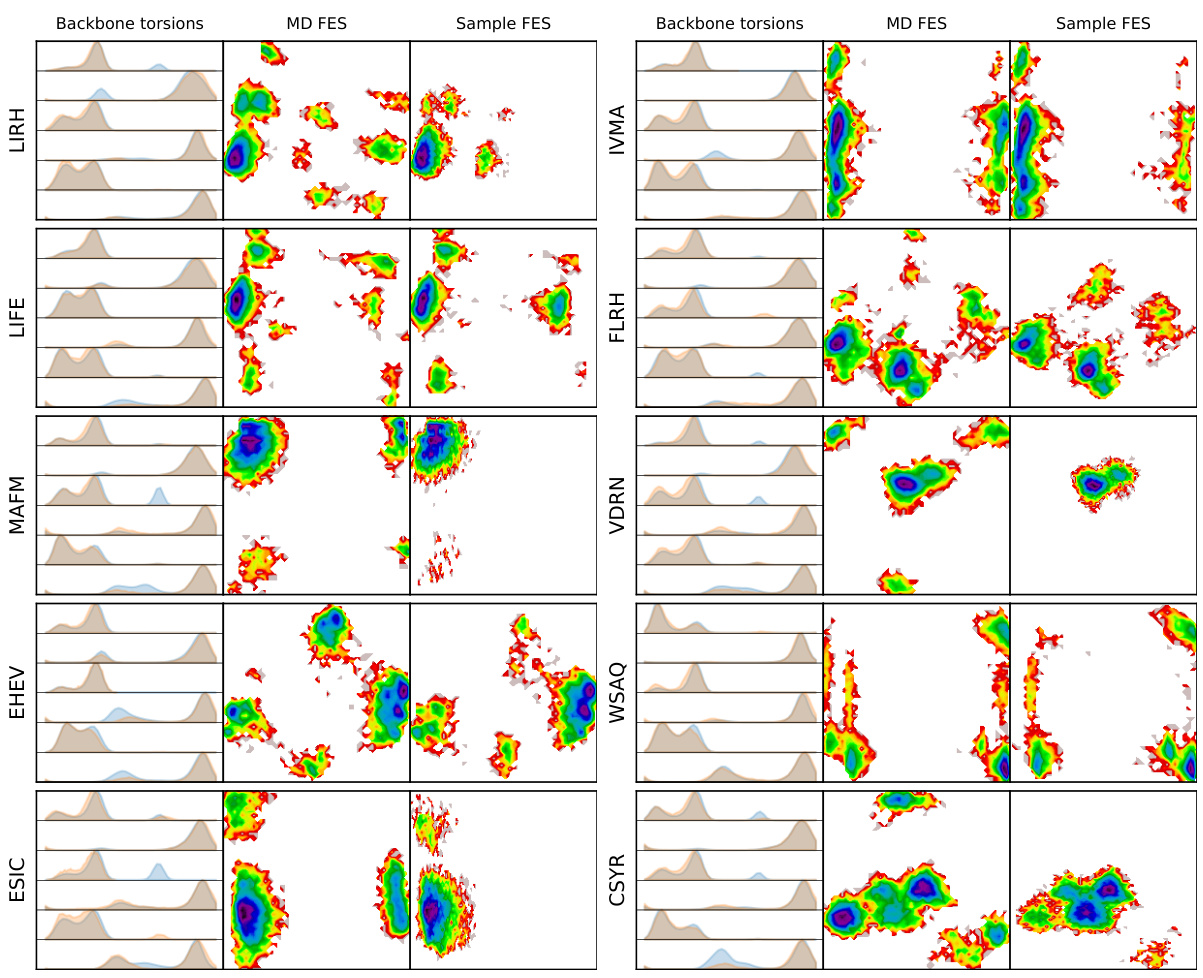

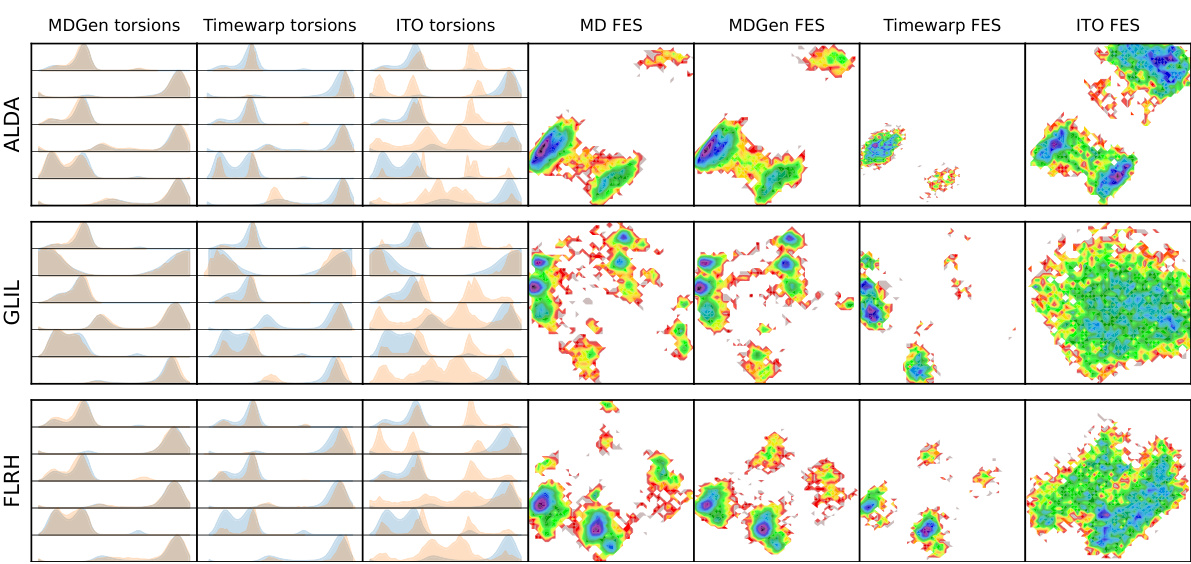

This figure presents a comprehensive evaluation of the forward simulation capabilities of the MDGEN model on test peptides. It shows the comparison of generated trajectories with ground truth MD trajectories across various metrics including torsion angle distributions, free energy surfaces, MSM state occupancies, decorrelation times, and torsional relaxation times.

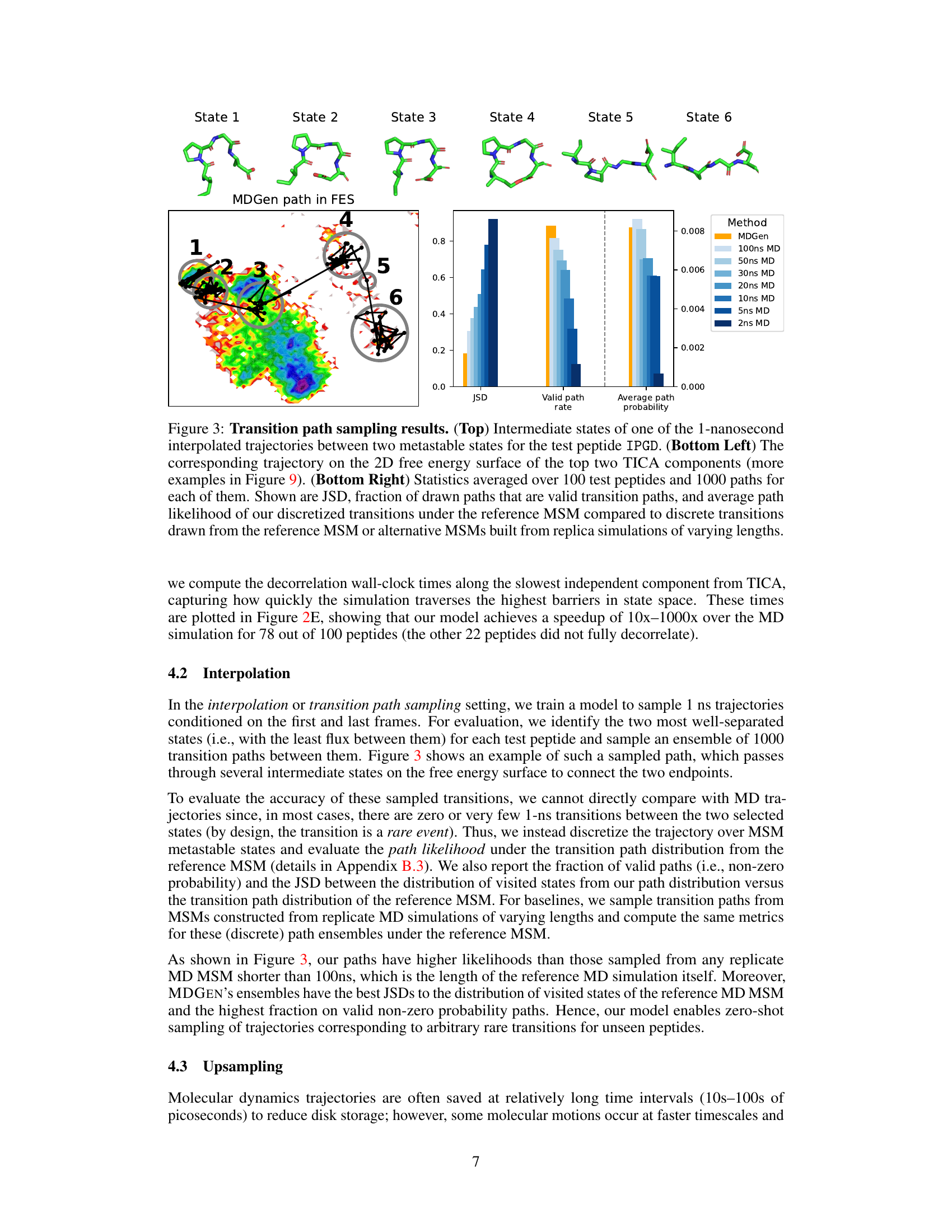

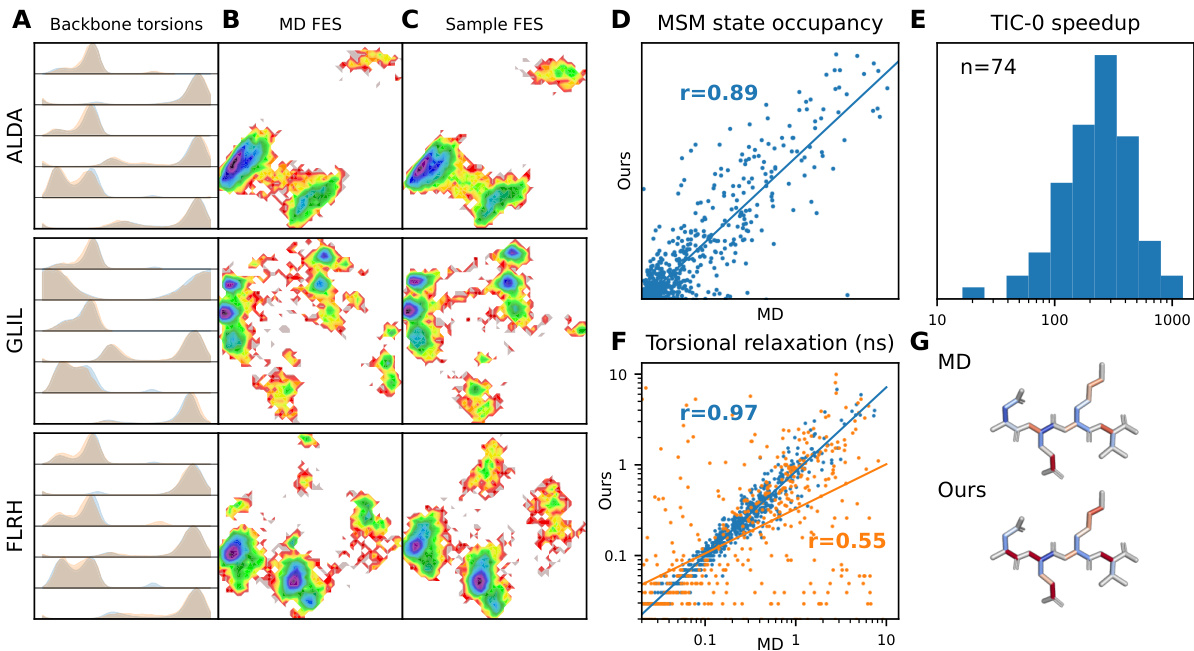

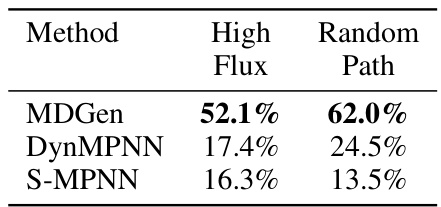

This figure shows the results of transition path sampling, a method used to find plausible transition pathways between two metastable states. The top panel displays the intermediate states along a representative trajectory for the tetrapeptide IPGD. The bottom left panel shows this same trajectory plotted on a 2D free energy surface calculated using the top two time-lagged independent component analysis (TICA) components. The bottom right panel presents quantitative metrics that compare the quality of the generated transition paths against those from replica molecular dynamics simulations of varying lengths; these metrics include Jensen-Shannon divergence (JSD), the fraction of generated paths that are valid, and the average path probability.

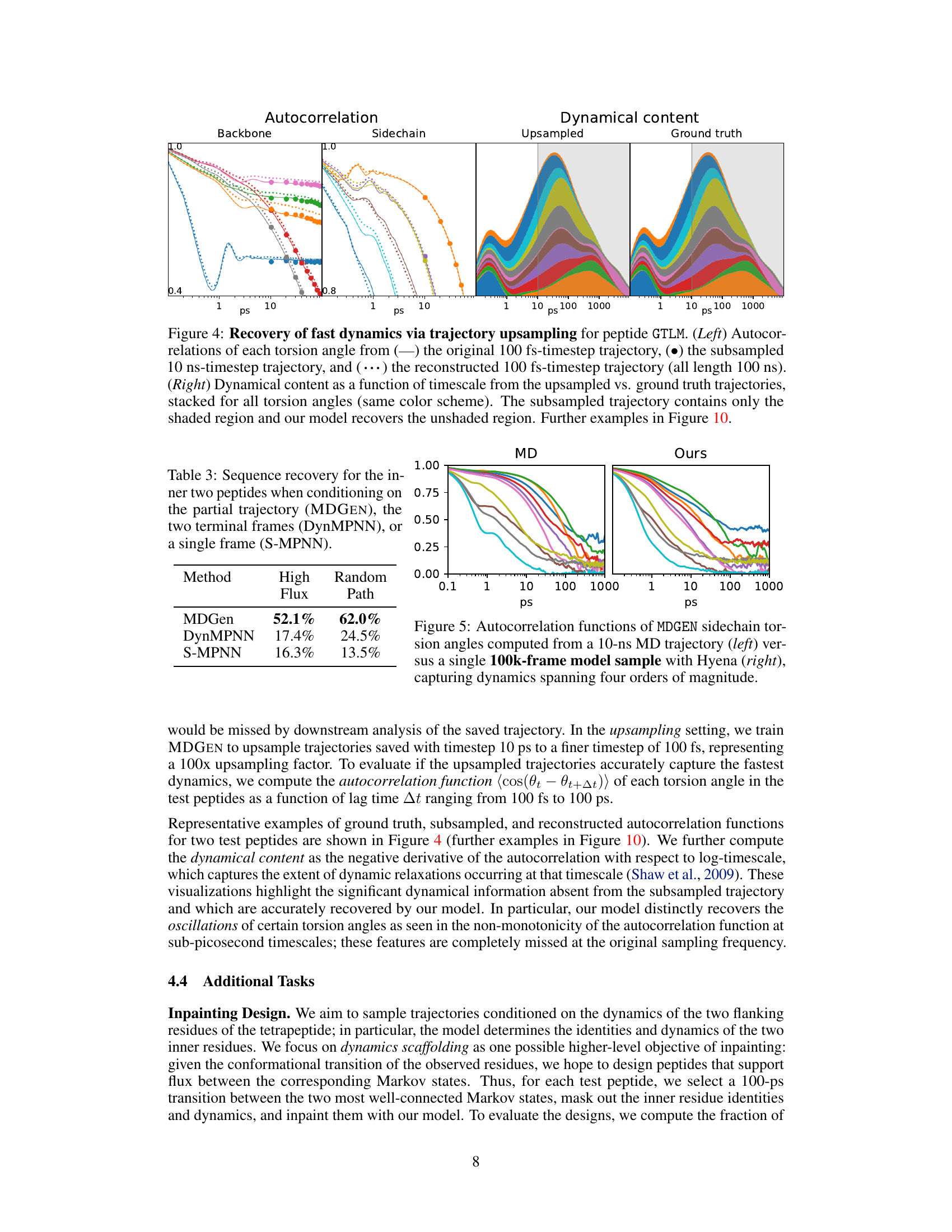

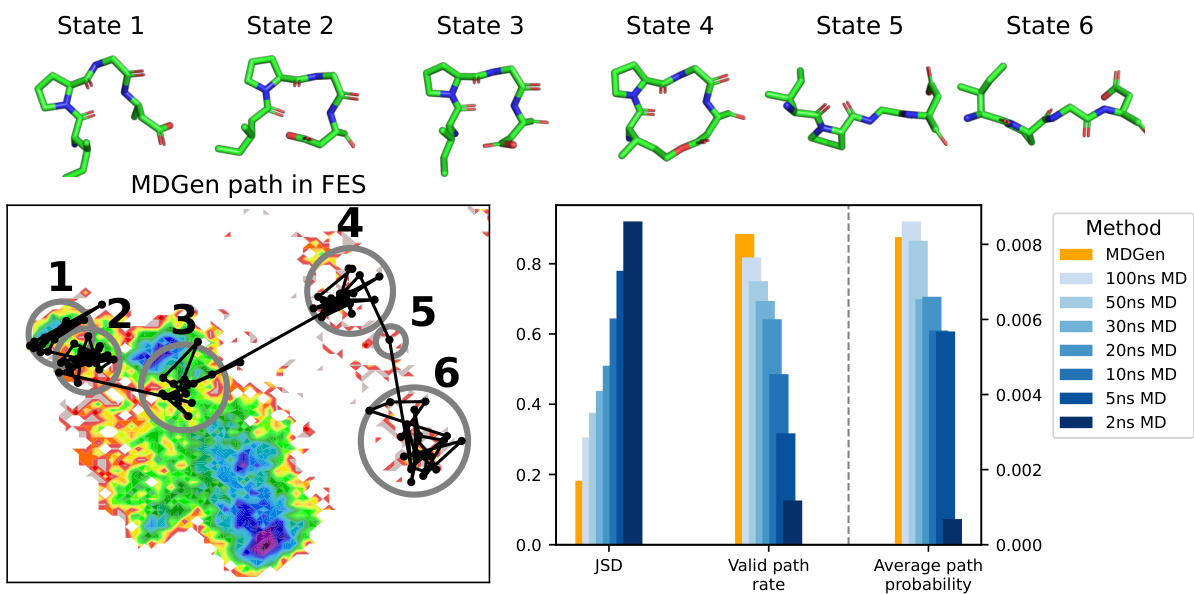

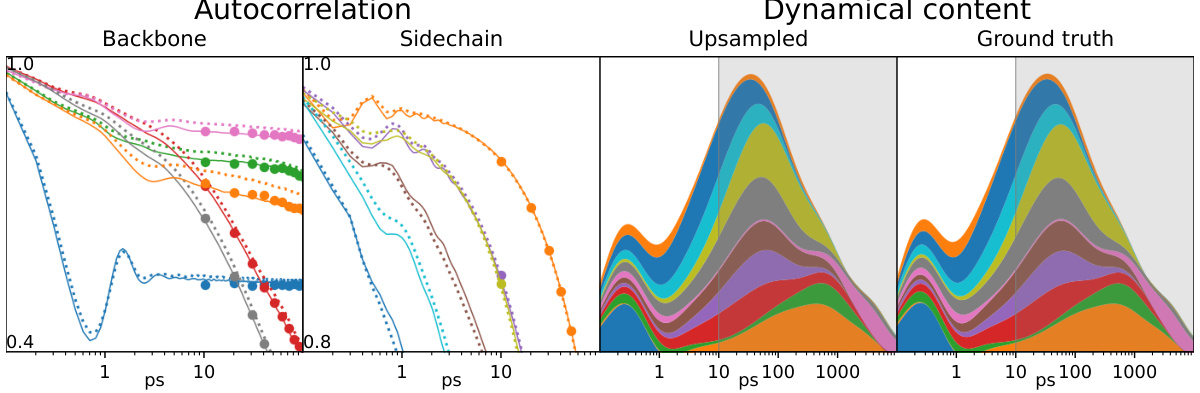

This figure shows the results of trajectory upsampling for peptide GTLM. The left panel shows the autocorrelation of each torsion angle for the original trajectory (100 fs timestep), subsampled trajectory (10 ns timestep), and the upsampled trajectory (100 fs timestep) reconstructed by the model. The right panel displays the dynamical content as a function of timescale, comparing the upsampled trajectory with the ground truth. The shaded region in the right panel represents the information available in the subsampled trajectory, while the unshaded region shows the additional dynamical information recovered by the model through upsampling.

This figure presents a comprehensive evaluation of the forward simulation capabilities of the MDGEN model on test peptides. It displays various metrics comparing the model’s generated trajectories with ground truth MD simulations, illustrating its ability to accurately reproduce both structural and dynamical properties.

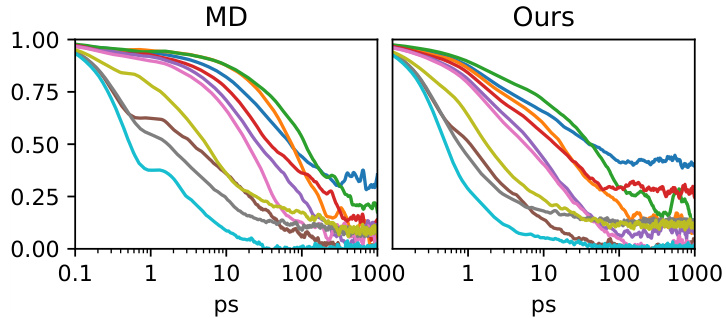

This figure compares the ensembles generated by MDGEN and MD for protein 6uof_A. The top section shows 3D renderings of the protein structures generated by both methods, with similar overall conformations. The bottom shows a plot of Cα root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSFs) along the protein backbone, demonstrating strong correlation (Pearson r = 0.74) between the fluctuations predicted by MDGEN and those observed in the MD simulations. This indicates MDGEN’s ability to accurately capture the dynamic properties of proteins.

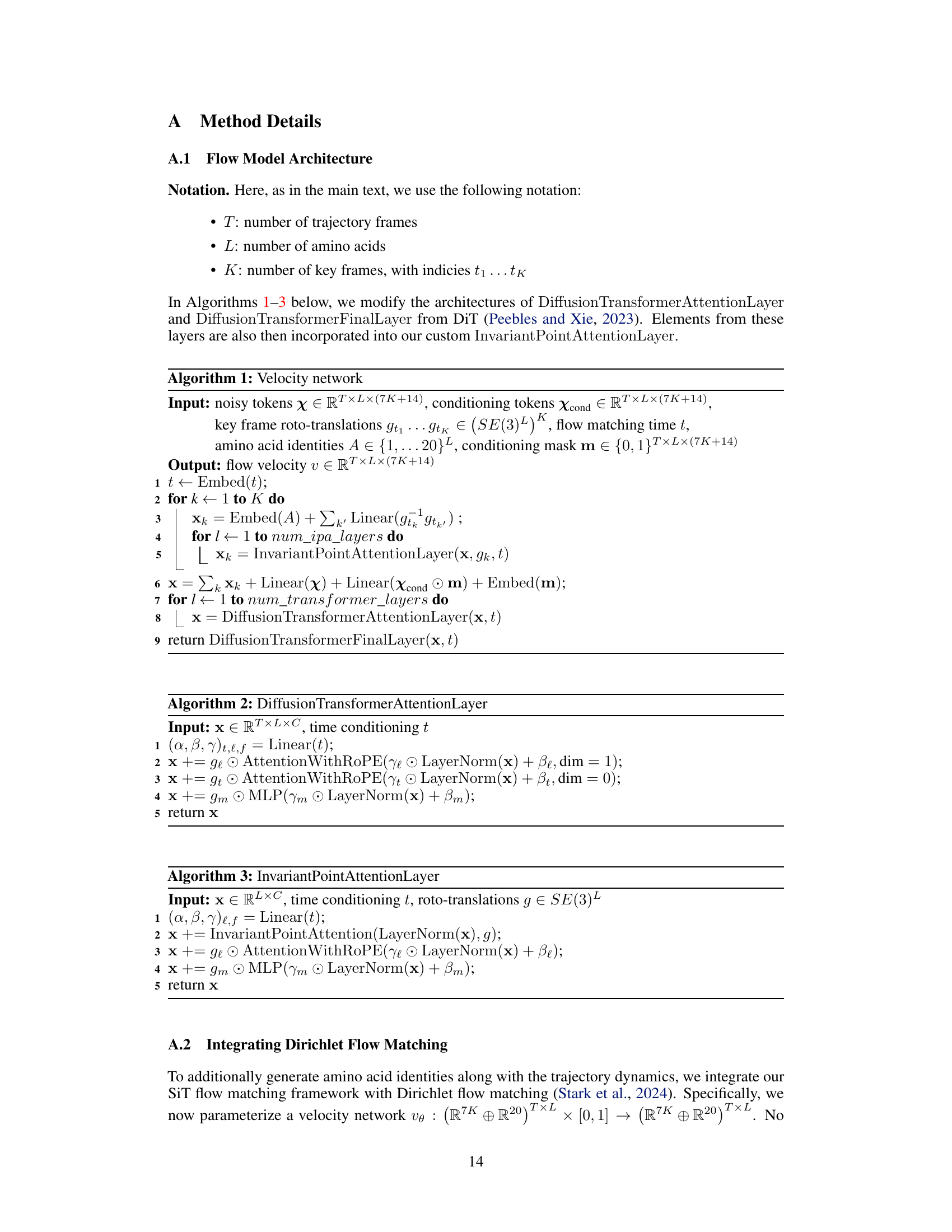

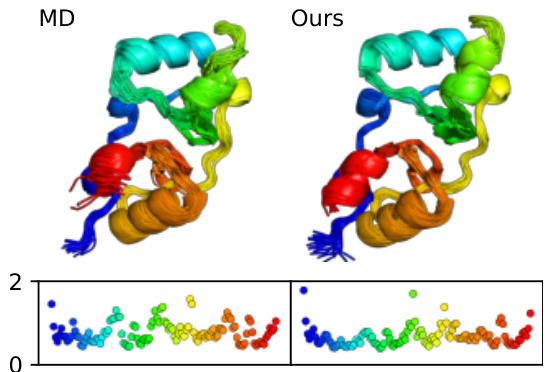

This figure shows the comparison of backbone torsion angle distributions and free energy surfaces between MD simulation and MDGEN model for 10 randomly selected test peptides. The distributions (histograms) of backbone torsion angles are shown alongside the free energy surfaces (FES) generated from the top two time-lagged independent component analysis (TICA) components. The orange color represents the MD simulations, while the blue color represents the MDGEN samples. The overall consistency between MD and MDGEN results across different peptides suggests that MDGEN accurately captures the conformational dynamics.

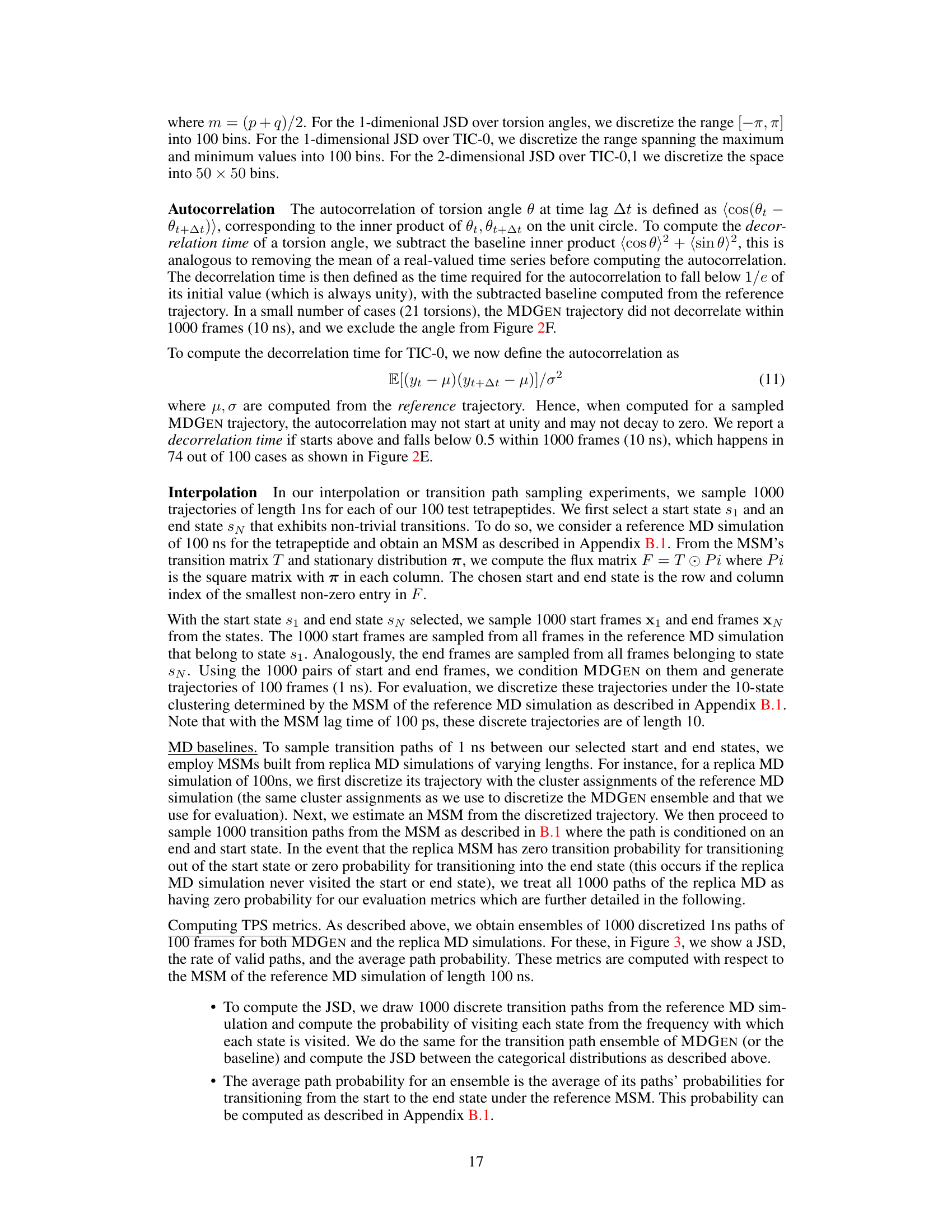

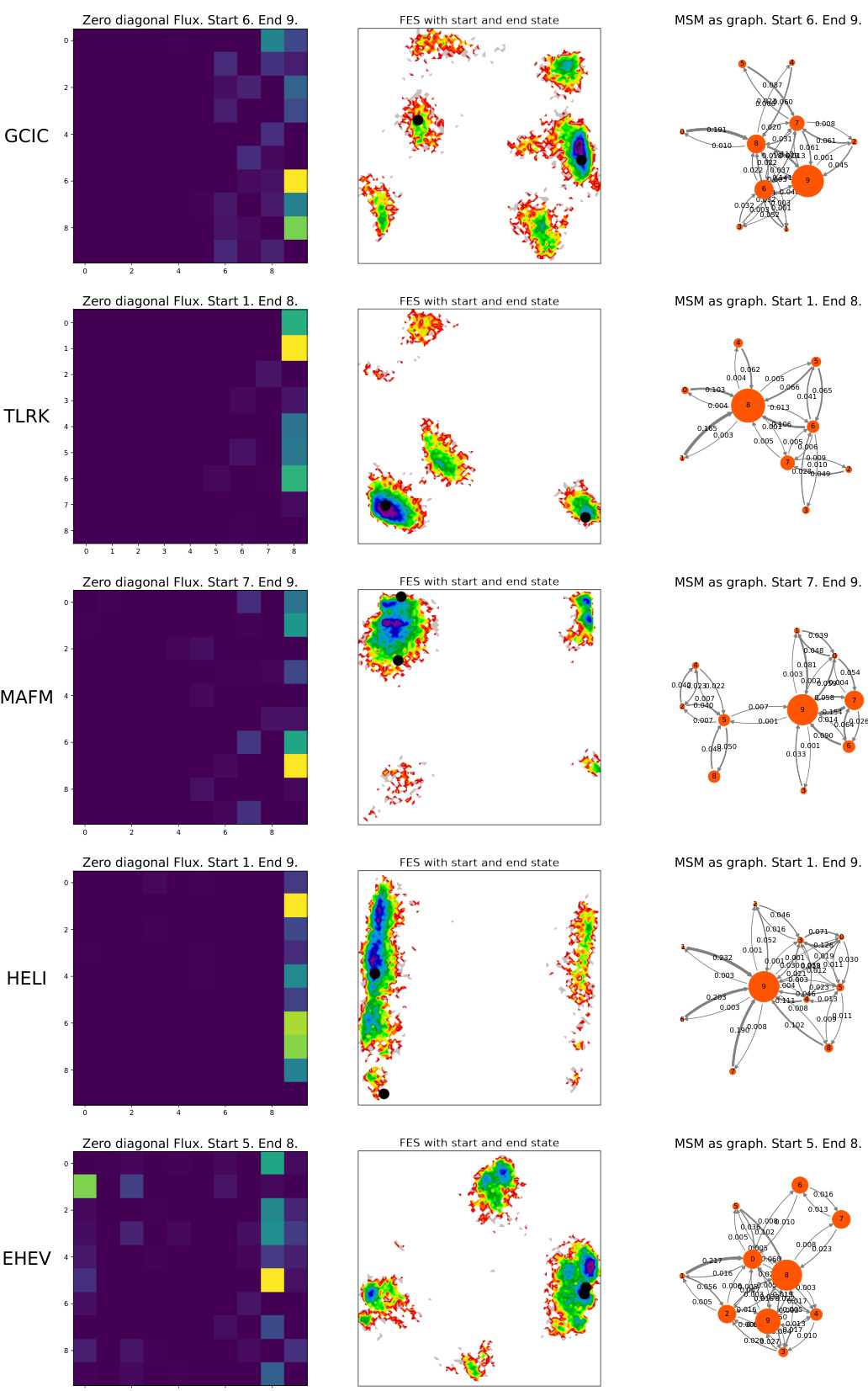

This figure compares the flux matrices obtained from the Markov State Models (MSMs) built using ground truth MD trajectories and MDGEN generated trajectories for ten randomly selected test peptides. The flux matrix represents the transition probabilities between different metastable states. Darker colors indicate stronger transitions (higher flux) between states. The Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ) is provided for each pair of matrices, measuring the similarity of their transition patterns.

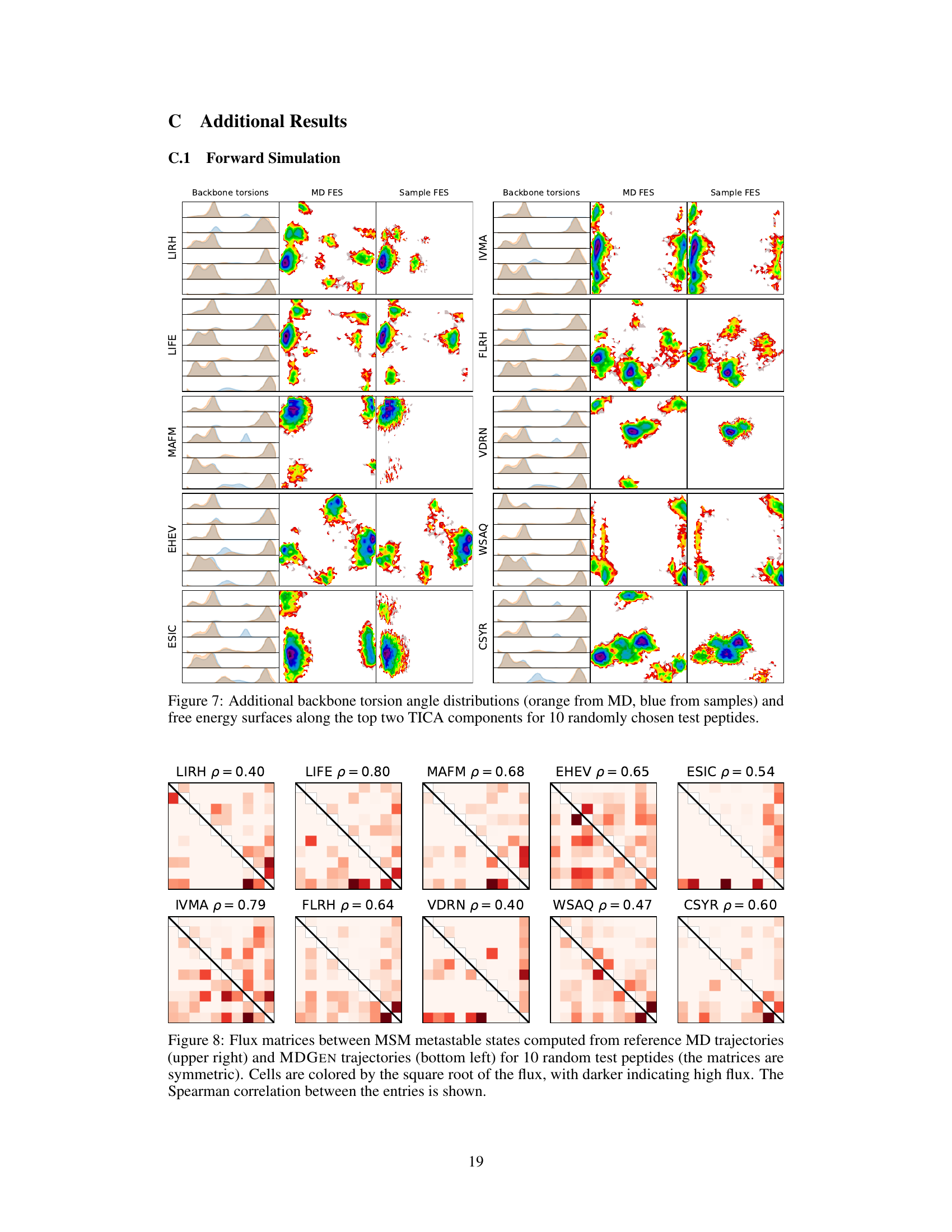

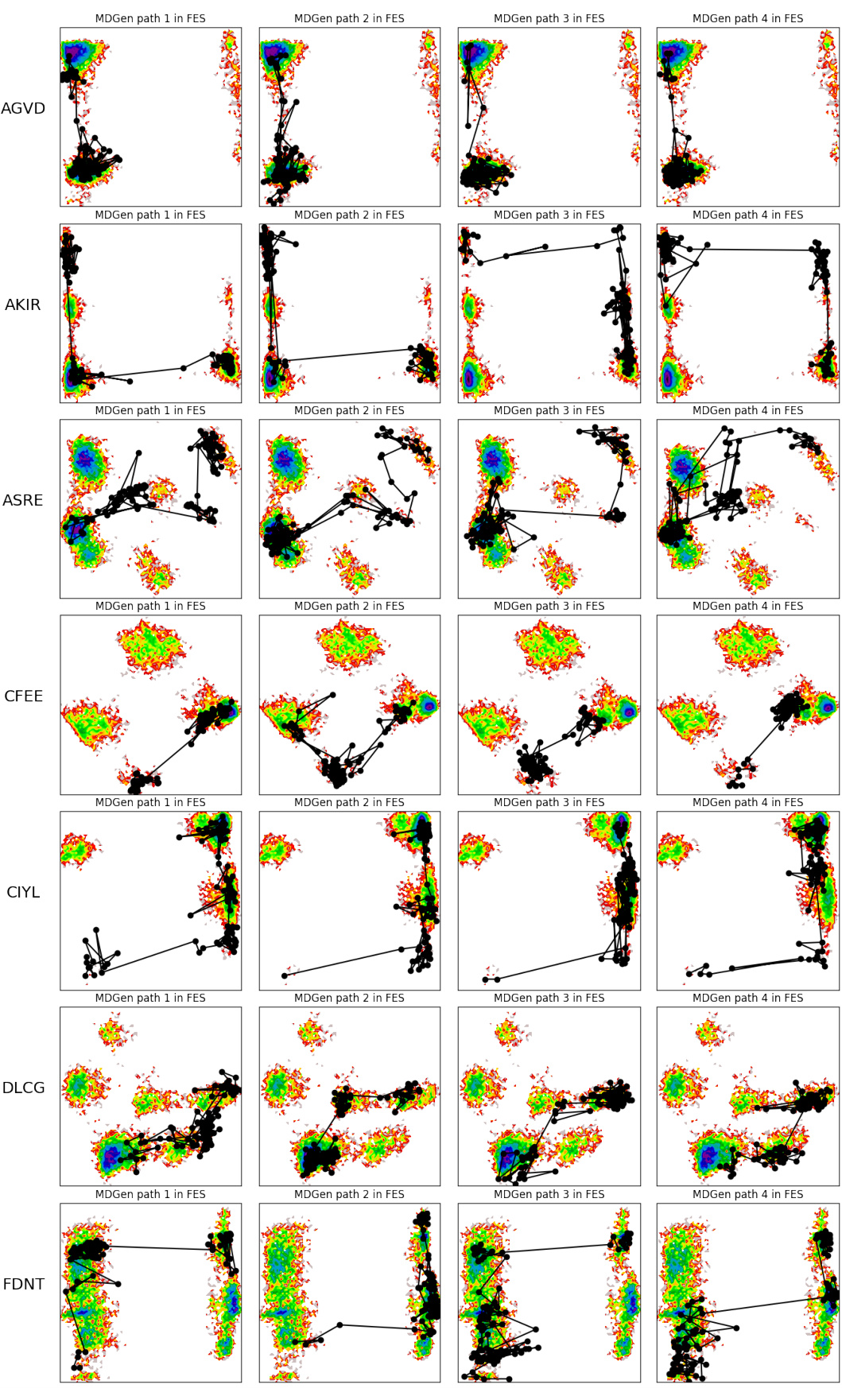

This figure visualizes four example transition paths generated by MDGEN for different tetrapeptides. Each path connects two metastable states and illustrates the intermediate states visited during the transition. The paths are shown projected onto the free energy surface (FES) to highlight the conformational changes involved. This figure demonstrates MDGEN’s ability to sample plausible transition pathways between metastable states for unseen molecules, a key aspect of its ability to perform transition path sampling.

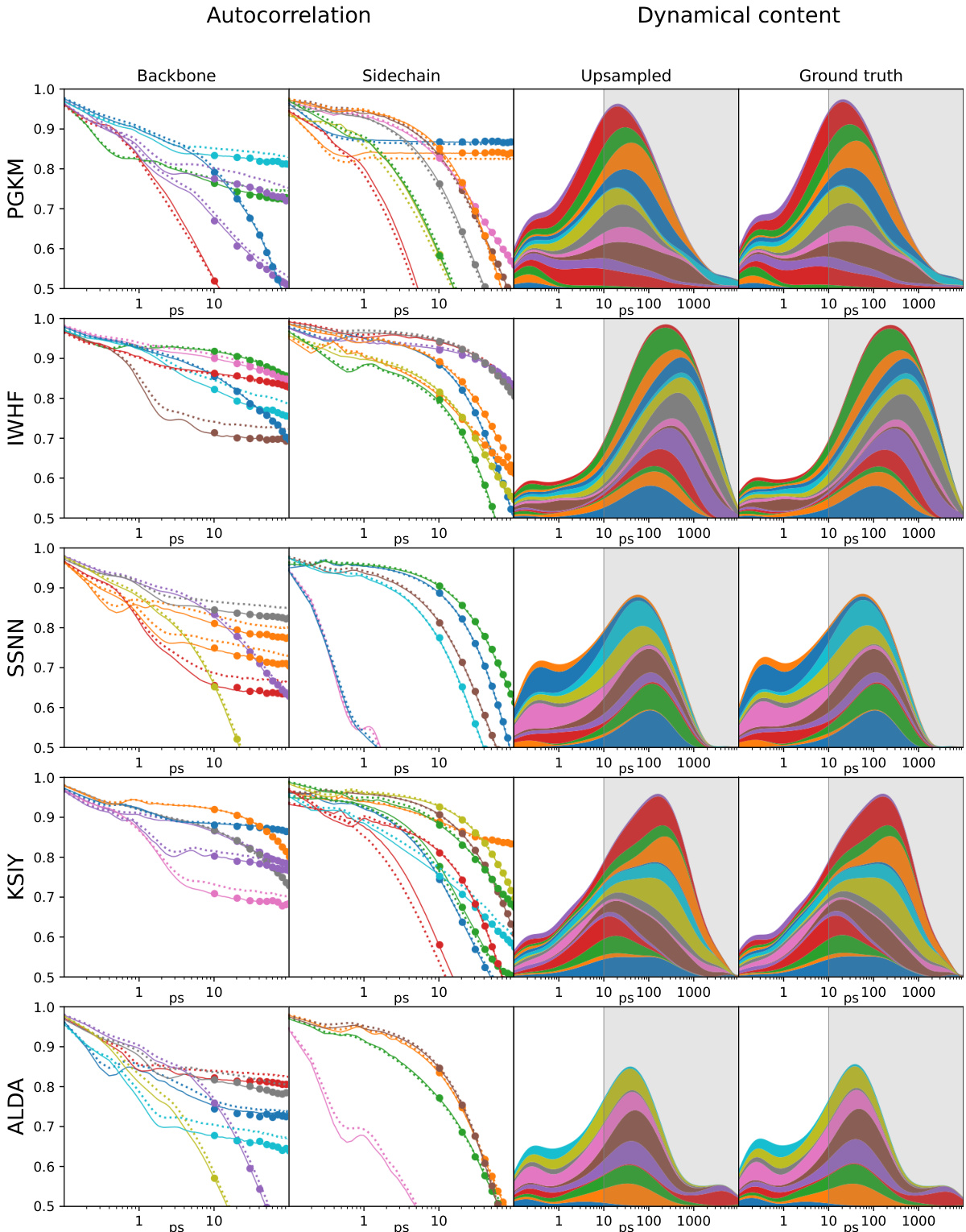

This figure demonstrates the capability of MDGEN to upsample molecular dynamics trajectories. The left panels show autocorrelation functions for backbone and sidechain torsion angles, comparing the original high-frequency trajectory (100 fs timestep), a downsampled low-frequency trajectory (10 ns timestep), and the trajectory upsampled by MDGEN back to the original 100 fs timestep. The right panels visualize the dynamical content (changes in torsion angles as a function of time) of these trajectories. MDGEN successfully recovers the fast dynamics lost in the downsampled trajectory.

This figure presents a comprehensive evaluation of the MDGEN model’s forward simulation capabilities on test peptides. It uses multiple visualization techniques to showcase the accuracy and efficiency of MDGEN in reproducing various aspects of molecular dynamics. Panel (A) compares torsion angle distributions, highlighting the model’s ability to capture structural details. Panels (B) and (C) illustrate the model’s accuracy in free energy surface calculations. The model’s accuracy in replicating Markov State Model occupancies is shown in Panel (D). Panel (E) demonstrates the computational speedup achieved by MDGEN compared to traditional MD simulations. The model’s success in capturing dynamical features such as relaxation times of torsion angles is demonstrated in Panel (F). Finally, Panel (G) provides a visual comparison of torsion angle decorrelation times between MD and MDGEN simulations.

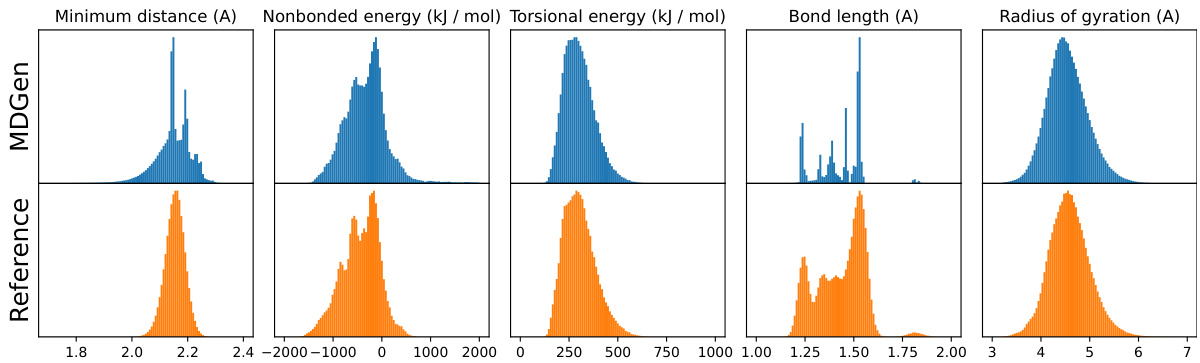

This figure presents a comparison of structural properties obtained from MDGEN’s forward simulations against those from reference MD trajectories for a set of test tetrapeptides. Five different structural validation metrics are considered: minimum distance between nonbonded atoms, nonbonded energy (sum of Coulomb and Lennard-Jones terms), torsional energy, heavy atom bond lengths, and radius of gyration. Each metric’s distribution is displayed as a histogram, with MDGEN results shown in blue and reference MD data in orange. The close agreement between the distributions suggests that MDGEN’s generated structures are of high structural quality and closely resemble the reference MD data.

More on tables

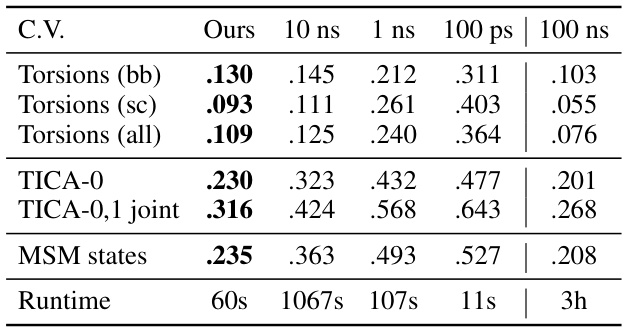

This table presents the Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) values between the generated trajectories by the model and the ground truth MD trajectories. It compares the JSD across various collective variables (torsion angles and TICA components) and different lengths of MD simulations (100 ps, 1 ns, 10 ns, and 100 ns), offering a benchmark against oracle performance (100 ns MD simulation). Lower JSD values indicate higher similarity between the generated and ground-truth trajectories.

This table details the different conditional generation settings used in the paper’s experiments. It specifies the key frames used for conditioning (the initial frame, or both the initial and final frames), what parts of the trajectory are generated by the model, and what information is provided as input (roto-translations, torsions, amino acid identities). The table also notes the dimensionality of the tokens used in each setting. The inpainting setting is distinct, as it excludes residue identities and torsions to reduce overfitting.

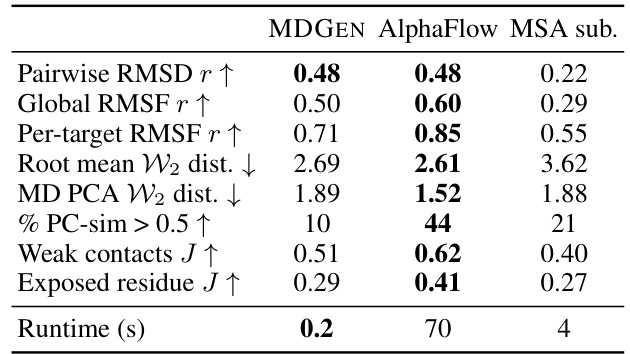

This table compares the performance of MDGEN against two other methods, AlphaFlow and MSA subsampling, for protein structure prediction. Several metrics are used to assess the quality of the generated protein structures, including pairwise and global RMSD (root mean square deviation), the distribution of distances between the generated and reference structures, and the similarity of the generated structures to those from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The runtime per sample structure is also provided, highlighting the computational efficiency of MDGEN compared to AlphaFlow and MSA subsampling.

This table details the different conditional generation settings used in the paper’s experiments. It specifies the key frames used for conditioning (the initial frame, or both the initial and final frames), what data is generated by the model, what data is provided as input to condition the model, and the resulting dimensionality of the input tokens. The tasks covered are forward simulation, interpolation, upsampling, and inpainting. For the inpainting task, it’s noted that excluding residue identities and torsion angles from the conditioning improved model performance.

This table compares the performance of MDGEN against two other methods, Timewarp and ITO, in terms of the Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) between the sampled and ground truth distributions. The comparison is done along various collective variables in the forward simulation setting. The collective variables include backbone torsions, sidechain torsions, all torsions, TICA-0, TICA-0,1 joint, and MSM states. The runtime for each method is also provided.

Full paper#