↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current motion-music generation research often treats motion and music as separate entities, leading to suboptimal synchronization and limited creative possibilities. Furthermore, computational costs for long sequences pose a significant hurdle. This paper aims to solve these challenges.

The proposed MoMu-Diffusion framework addresses these limitations by first using BiCoR-VAE to extract modality-aligned latent representations. Then, a novel multi-modal Transformer-based diffusion model and a cross-guidance sampling strategy enable various generation tasks such as cross-modal, multi-modal, and variable-length generation. Extensive experiments demonstrate that this approach outperforms recent state-of-the-art methods, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it tackles the long-standing challenge of jointly modeling motion and music, pushing the boundaries of audio-visual generation. It introduces a novel framework that achieves state-of-the-art results in generating realistic and synchronized motion-music sequences, opening new avenues for creative applications and fundamental research in multi-modal AI.

Visual Insights#

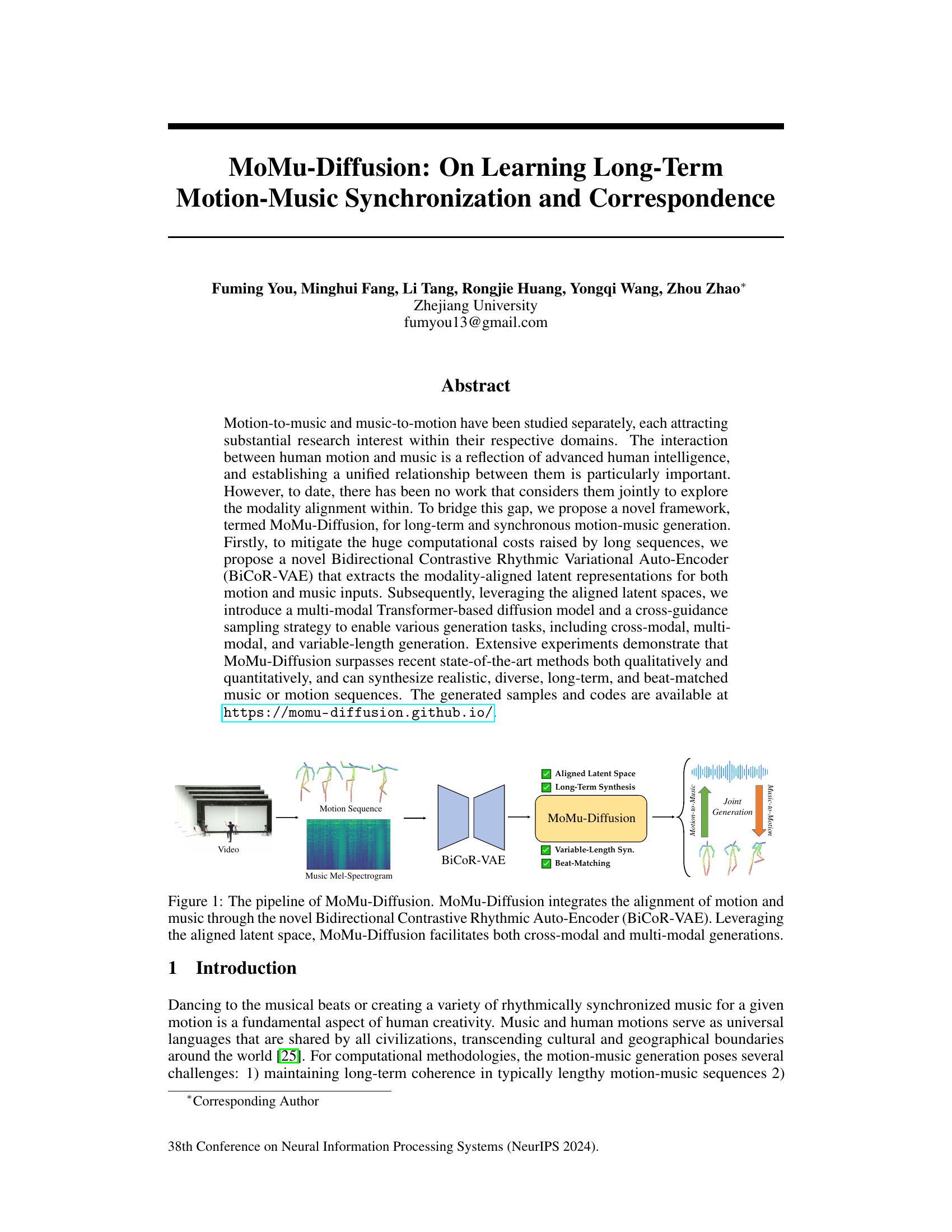

This figure illustrates the architecture of MoMu-Diffusion, a novel framework for generating long-term and synchronous motion-music sequences. It starts with a motion sequence and music mel-spectrogram which are encoded into an aligned latent space by a Bidirectional Contrastive Rhythmic Variational Auto-Encoder (BiCoR-VAE). This aligned latent space is then fed into a multi-modal Transformer-based diffusion model that generates various types of motion-music sequences including cross-modal (motion-to-music or music-to-motion), multi-modal (joint generation), and variable-length generations while maintaining beat matching.

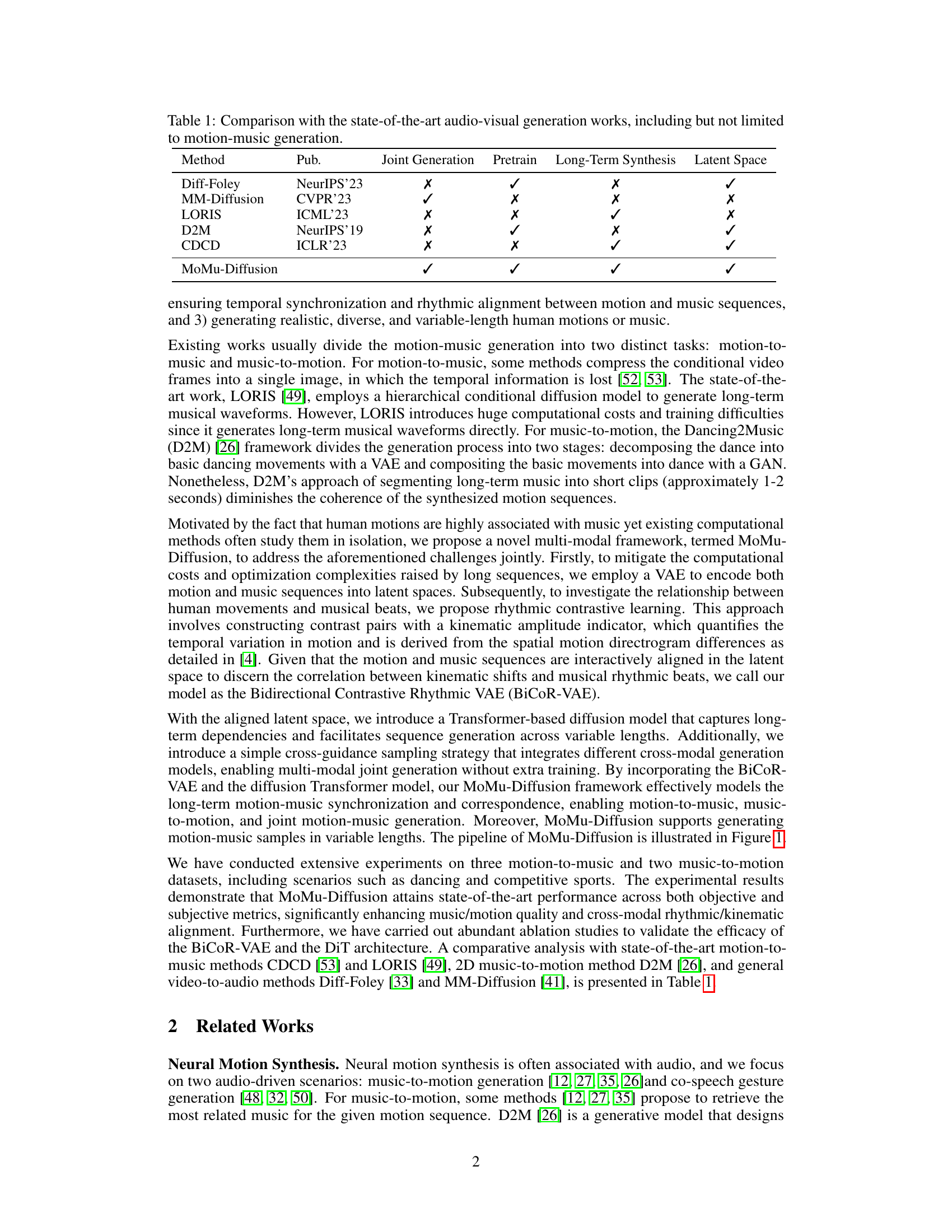

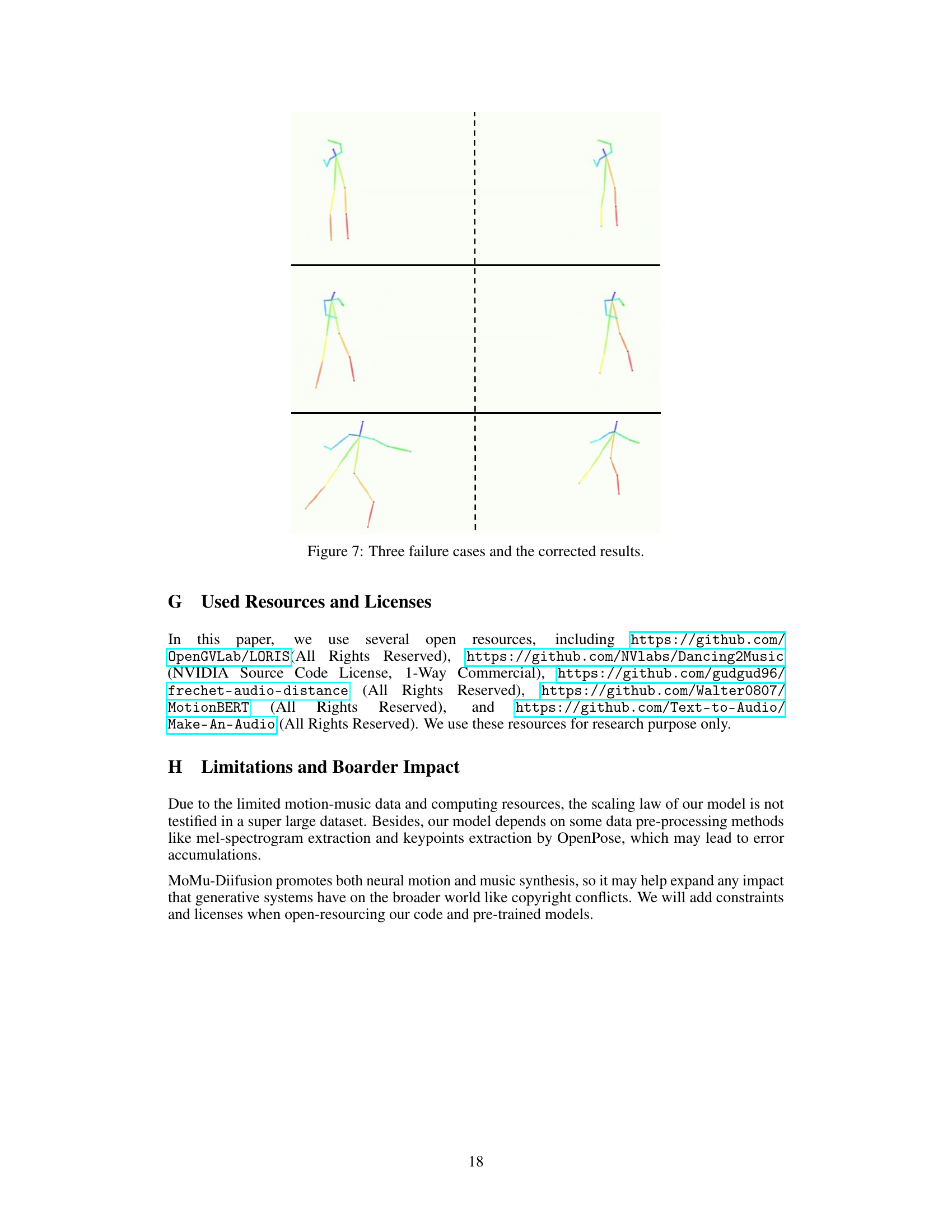

This table compares MoMu-Diffusion with other state-of-the-art audio-visual generation methods. It shows whether each method supports joint generation (music and motion created simultaneously), uses pre-training, handles long-term synthesis, and utilizes a latent space for representation.

In-depth insights#

Long-Term Synthesis#

The concept of “Long-Term Synthesis” in the context of motion-music generation is crucial for producing realistic and engaging results. Successfully modeling long-term temporal dependencies between audio and motion is a significant challenge, as traditional methods often struggle to maintain coherence across extended sequences. This necessitates innovative approaches that can capture and generate long-term rhythmic patterns and kinematic relationships. Addressing computational constraints is also vital, as handling lengthy sequences requires efficient algorithms and architectures to prevent a massive increase in computational cost. Effective solutions could involve hierarchical models, attention mechanisms, or carefully designed latent space representations to manage information efficiently. The quality of the synthesis is also paramount, requiring models that can generate diverse and realistic motions and music while maintaining synchronization. Finally, the ability to control various aspects of the generation process (e.g., variable-length synthesis, beat-matching, cross-modal generation) is highly desirable, improving the practical usability of the generated content and opening up creative possibilities.

BiCoR-VAE Model#

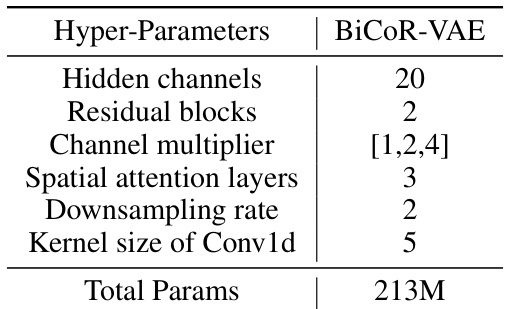

The BiCoR-VAE (Bidirectional Contrastive Rhythmic Variational Auto-Encoder) model is a crucial component of the MoMu-Diffusion framework, designed to extract modality-aligned latent representations for both motion and music inputs. Its novelty lies in addressing the computational challenges of long sequences and the need for aligning rhythm and kinematics across modalities. BiCoR-VAE employs a contrastive learning strategy, focusing on rhythmic correspondence between motion and music. By creating contrast pairs based on kinematic amplitude indicators, it learns to associate rhythmic variations in the motion with musical beats, effectively learning a synchronized latent space. The bidirectional nature ensures that the model captures relationships in both motion-to-music and music-to-motion directions, leading to robust cross-modal generation capabilities. The use of VAEs allows for efficient compression of long sequences, mitigating computational costs and facilitating downstream generation tasks using the aligned latent space.

Multimodal Diffusion#

Multimodal diffusion models represent a significant advancement in generative modeling, enabling the synthesis of complex data involving multiple modalities. The core idea is to learn a joint representation of different data types (e.g., image, audio, text) and then use a diffusion process to generate samples from this unified space. This approach addresses the limitations of unimodal models which struggle to capture the intricate relationships between different sensory inputs. A key challenge in multimodal diffusion lies in effectively aligning and integrating the diverse feature spaces of each modality. Successful strategies often involve contrastive learning or other techniques for establishing correspondences between modalities. The resulting models can achieve remarkable performance on tasks such as cross-modal translation, multi-modal generation, and conditional synthesis. However, significant computational resources are often required for training and inference, particularly with high-dimensional data. Furthermore, evaluating the quality and coherence of generated multimodal data remains a significant research challenge and necessitates the development of robust evaluation metrics that capture both individual modality quality and the inter-modal relationships. Future research directions may focus on improving efficiency, enhancing alignment techniques, and developing more comprehensive evaluation frameworks.

Cross-Modal Guidance#

Cross-modal guidance, in the context of multimodal generation, refers to techniques that leverage information from one modality to improve the generation of another. In the paper, it likely involves using a pre-trained motion-to-music model’s output to guide the generation of music and vice-versa. This approach is particularly effective for long-term synchronization because it allows the model to learn and maintain temporal coherence between the two modalities across extended sequences. This isn’t simply a parallel generation process; it’s an iterative interaction. The output of one model informs and refines the generation of the other, leading to a more coherent and realistic final output. A key advantage is that it avoids the computational cost of training a single, monolithic model for joint motion and music generation, which is challenging due to the high dimensionality and temporal length of the data. Instead, it leverages already well-trained individual models to efficiently achieve a superior result by exploiting their complementary strengths. The resulting synergy enhances temporal alignment (beat-matching) and overall quality. The cross-guidance sampling strategy is a critical component, determining how these model interactions are orchestrated, perhaps by weighting the contributions of each model at different stages of the generation process, enabling a controlled balance between independence and dependence of the two modalities. It’s a sophisticated approach that balances computational efficiency with improved quality and synchronization in a complex generative task.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore more sophisticated methods for beat synchronization and rhythmic alignment, potentially leveraging advancements in symbolic music representation and analysis. Improved cross-modal generation models should be investigated, considering generative adversarial networks or other approaches to enhance the realism and diversity of synthesized motion and music. Furthermore, incorporating diverse musical styles and genres would broaden the applicability and creativity of the framework. Another valuable area for exploration is handling longer sequences more efficiently, possibly by exploring hierarchical modeling techniques or reducing computational complexity through optimized architectures. Lastly, exploring different modalities, such as other forms of audio (e.g., environmental sounds) or haptic feedback combined with music and motion, would enrich the experience and create new opportunities for artistic expression and therapeutic applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows a detailed overview of the MoMu-Diffusion framework. It illustrates the two main components: a BiCoR-VAE (Bidirectional Contrastive Rhythmic Variational Autoencoder) for aligning latent representations of motion and music, and a Transformer-based diffusion model for generating sequences. The figure visually explains how these components work together to enable cross-modal (motion-to-music and music-to-motion), multi-modal, and variable-length generation. It showcases the process of modality alignment, cross-guidance sampling strategy and the final sequence generation.

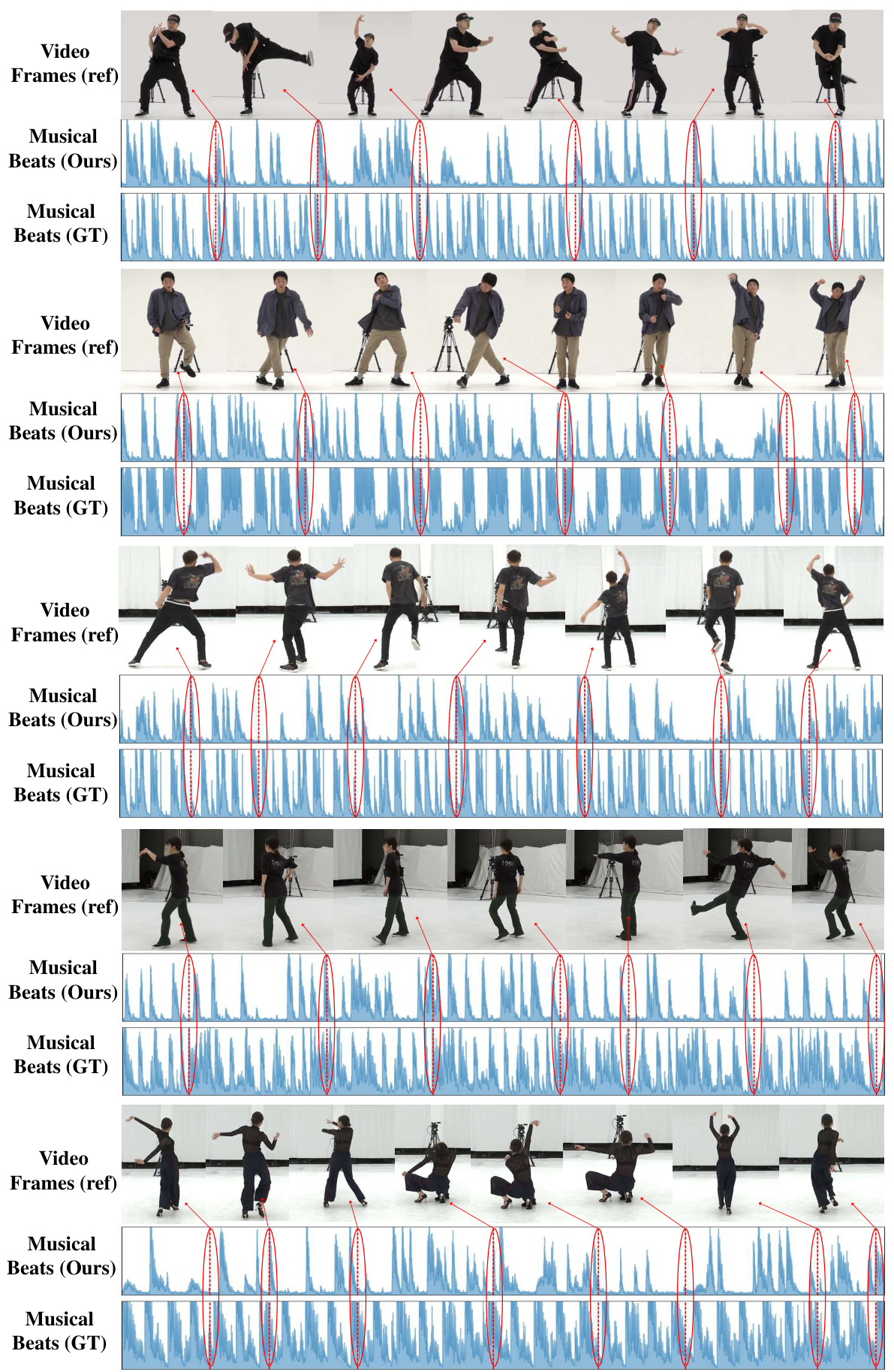

This figure shows examples of beat matching in the motion-to-music generation task using the AIST++ Dance dataset. It visually compares the extracted musical beats (produced by the model) with the ground truth musical beats, alongside the corresponding video frames. Red dashes highlight the detected beats, and red arrows point to the relevant video frames, demonstrating the temporal synchronization achieved between the generated music and the input motion.

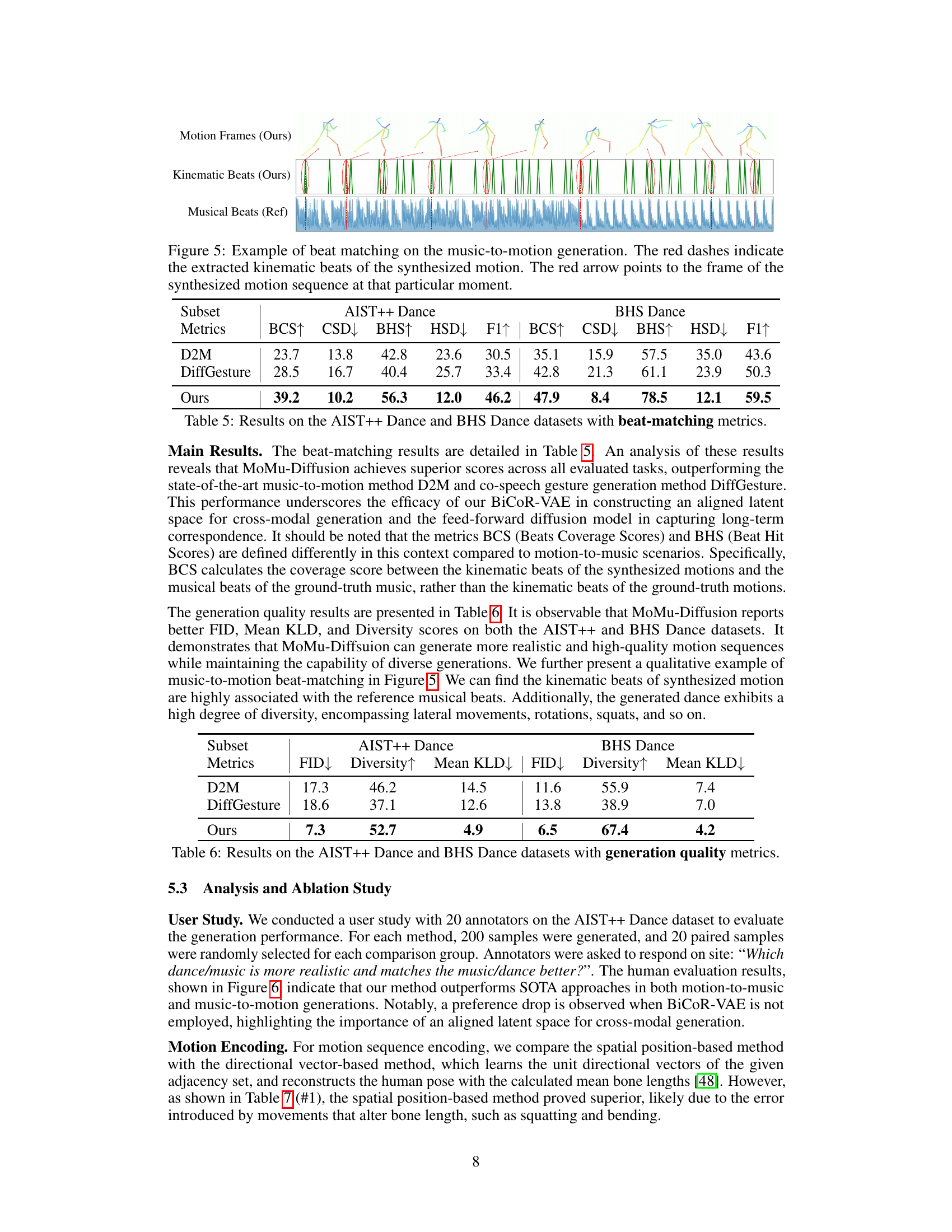

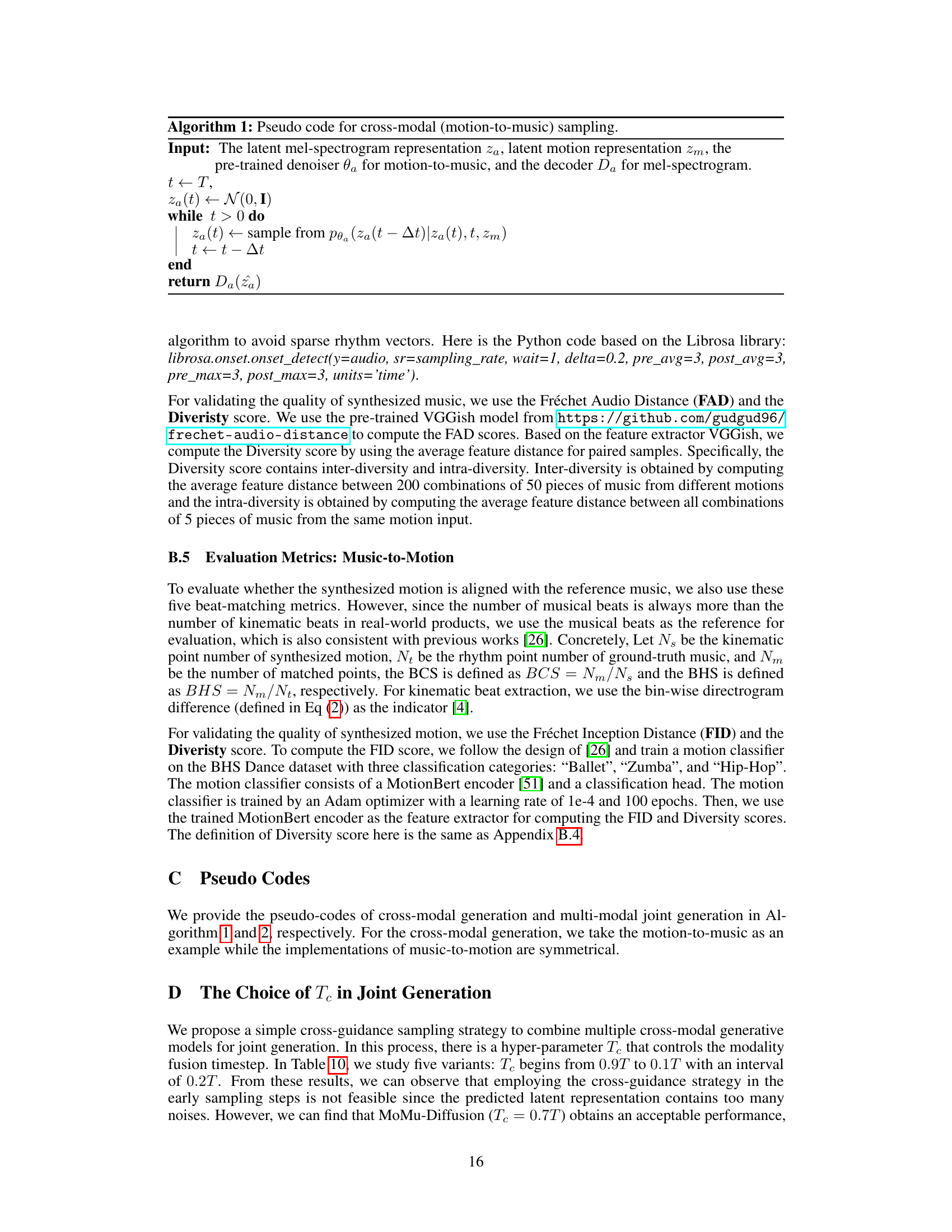

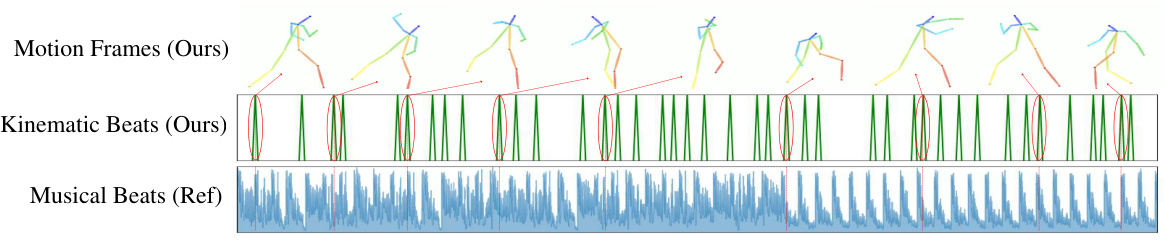

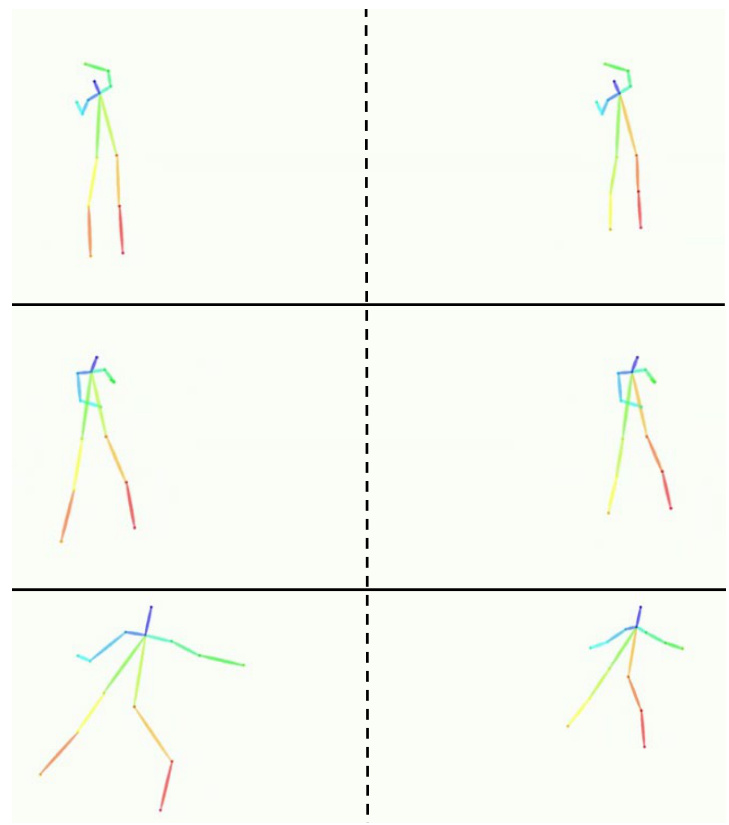

This figure shows an example of beat matching in music-to-motion generation using the proposed MoMu-Diffusion model. The top panel displays the generated motion sequence, with each frame showing the 2D pose of a dancer. The middle panel shows the kinematic beats extracted from the generated motion, represented as vertical bars. The bottom panel displays the reference musical beats from the input music, also shown as vertical bars. Red arrows highlight specific frames to illustrate correspondence between motion, kinematic beats, and musical beats. The figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generate motion that is synchronized with the rhythm of the input music.

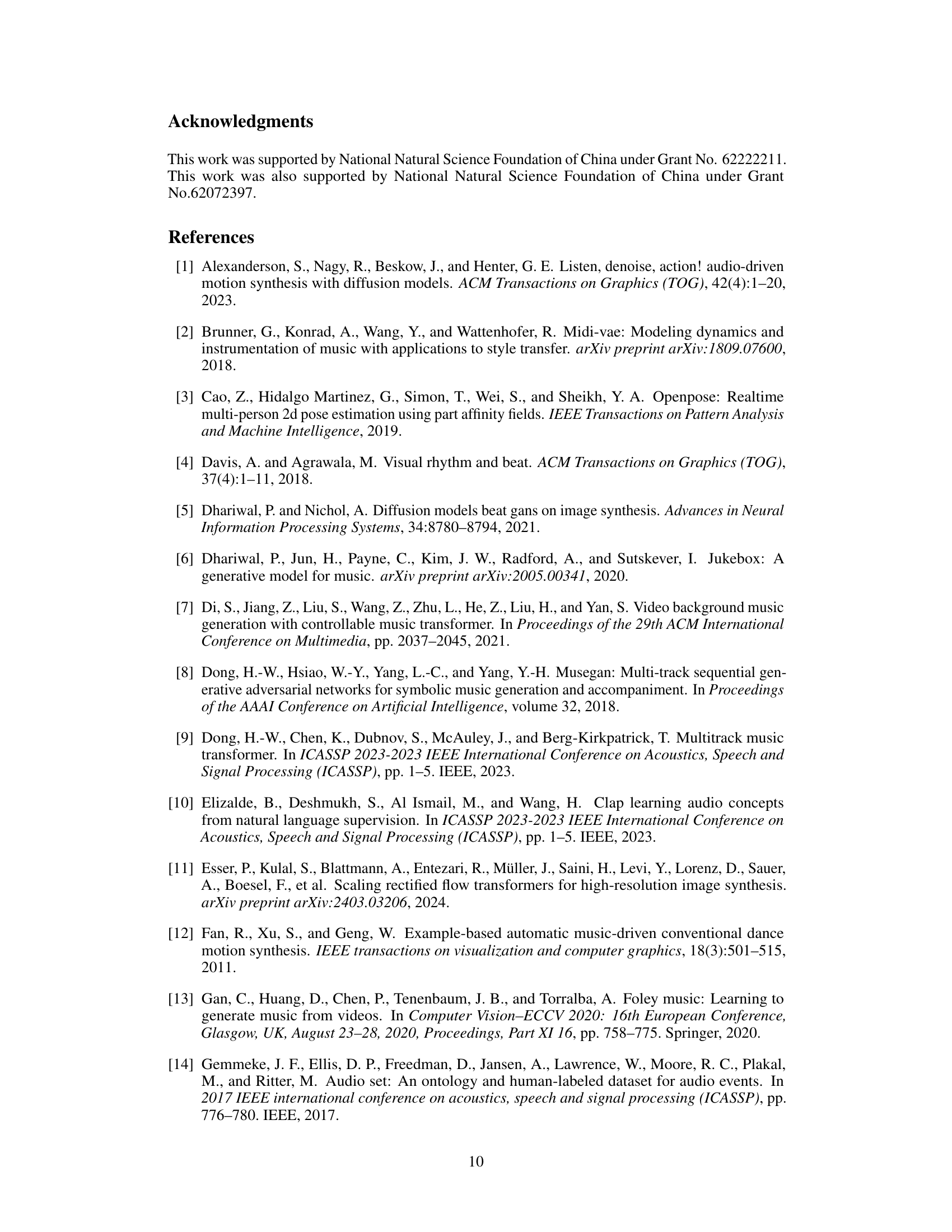

This figure presents the results of a user study comparing the realism and quality of motion-to-music and music-to-motion generation using different methods: MoMu-Diffusion (with and without BiCoR-VAE), LORIS, D2M, and real data. The bar chart displays the percentage of participants who preferred each method’s generated results in terms of realism and match between the generated content and the reference music/motion. The results show that MoMu-Diffusion with BiCoR-VAE outperforms other methods in both tasks, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed model and the importance of the aligned latent space.

The figure shows three examples of failure cases and their corresponding corrected results in the model’s generation of human motion. In each example, the left side presents the failure cases where there are some distortions or abnormalities in the generated motion. The right side displays the corrected results where the distortions or abnormalities have been removed, and the generated motion is improved.

This figure shows examples of beat matching results for the motion-to-music generation task on the AIST++ Dance dataset. Each row represents a different dance clip. The top section displays frames from the video. The middle section displays the musical beats generated by the MoMu-Diffusion model. The bottom section displays the ground truth musical beats. Red dashes highlight the detected beats, and red arrows indicate the corresponding video frame for visual comparison. The figure aims to demonstrate the model’s ability to accurately align generated music with the rhythm of the input motion.

This figure shows examples of beat matching results for motion-to-music generation on the AIST++ Dance dataset. Each example displays a sequence of video frames, along with a representation of the musical beats generated by the MoMu-Diffusion model (in blue) and the ground truth musical beats (in red). Red dashes mark the detected beats, and red arrows highlight the corresponding frame in the video sequence.

This figure shows examples of beat matching in the Figure Skating dataset for motion-to-music generation. For each example, there are three sections: the original video frames, the musical beats generated by the MoMu-Diffusion model, and the ground truth musical beats. Red dashes mark the detected beats in the generated and ground truth music, aligning them with specific frames in the video. The red arrows highlight the visual correspondence between the beats and the video frames.

This figure shows five examples of music-to-motion generation using the MoMu-Diffusion model. Each example displays the generated motion sequence (stick figures), the corresponding kinematic beats detected in the generated motion, and the reference musical beats from the input music. The red dashes highlight the detected kinematic beats, and the red arrows indicate the frame of the generated motion sequence that aligns with a specific point in the music. The visualization demonstrates the model’s ability to synchronize the generated motion with the rhythmic structure of the music.

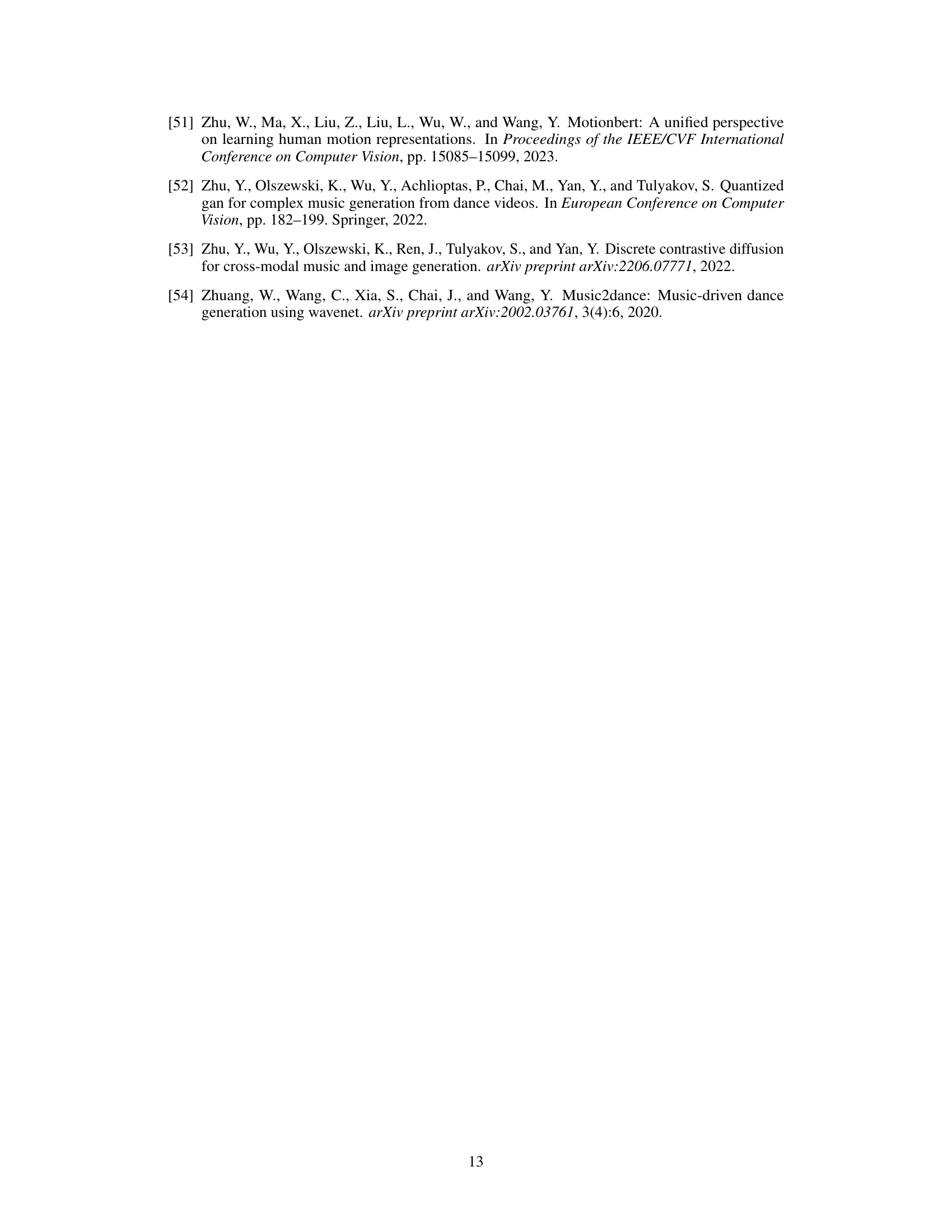

More on tables

This table compares MoMu-Diffusion with other state-of-the-art methods for audio-visual generation, focusing on aspects like joint generation, pre-training, long-term synthesis capabilities, and the use of latent space. It highlights MoMu-Diffusion’s strengths in handling long-term synthesis and utilizing latent space, contrasting it with methods that may lack these capabilities or rely on pre-training.

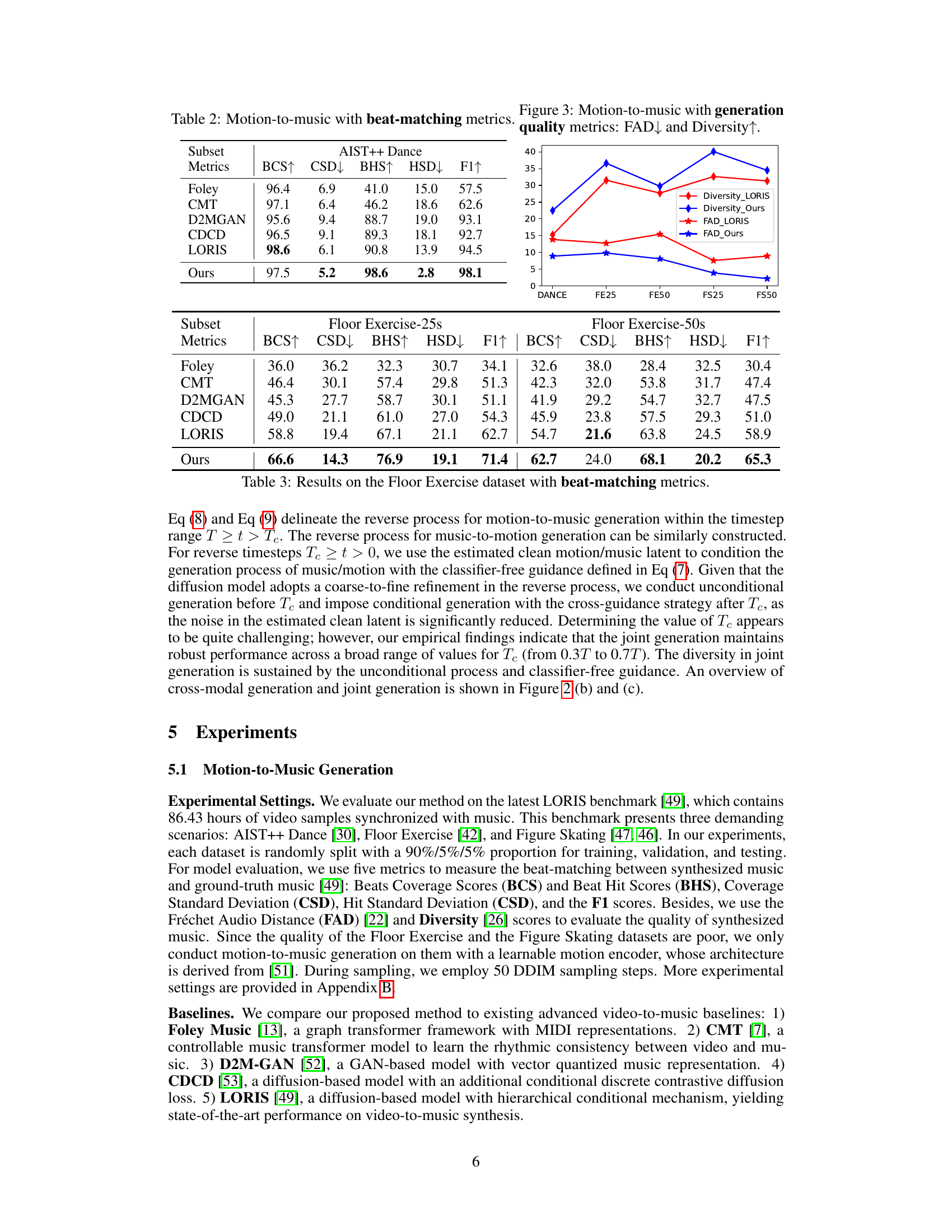

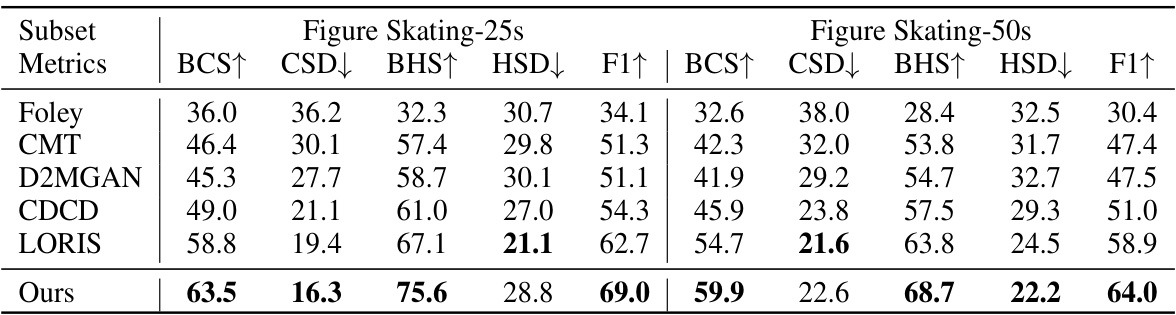

This table presents the results of beat-matching metrics for the Figure Skating dataset. The metrics used are Beats Coverage Scores (BCS), Coverage Standard Deviation (CSD), Beat Hit Scores (BHS), Hit Standard Deviation (HSD), and F1 score. These metrics quantitatively evaluate how well the synthesized music aligns with the ground truth music in terms of rhythmic beat synchronization. The table compares the performance of MoMu-Diffusion against several baseline methods (Foley, CMT, D2MGAN, CDCD, and LORIS) across two different lengths of Figure Skating sequences: 25 seconds and 50 seconds. Higher BCS and BHS, and lower CSD and HSD values generally indicate better beat synchronization.

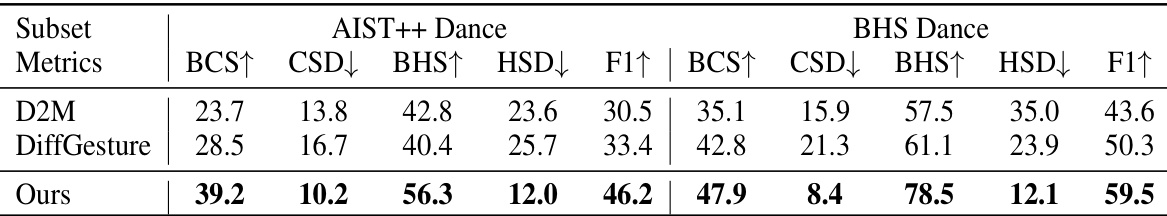

This table presents the performance comparison of MoMu-Diffusion against two baseline methods (D2M and DiffGesture) on two datasets (AIST++ Dance and BHS Dance) for music-to-motion generation. The beat-matching performance is evaluated using five metrics: BCS↑, CSD↓, BHS↑, HSD↓, and F1↑. Higher values for BCS↑ and BHS↑ indicate better beat alignment, while lower values for CSD↓ and HSD↓ represent improved beat consistency. F1↑ is the harmonic mean of BCS↑ and BHS↑, providing a holistic measure of beat-matching accuracy. The results show that MoMu-Diffusion significantly outperforms both baselines, demonstrating superior beat-matching capabilities.

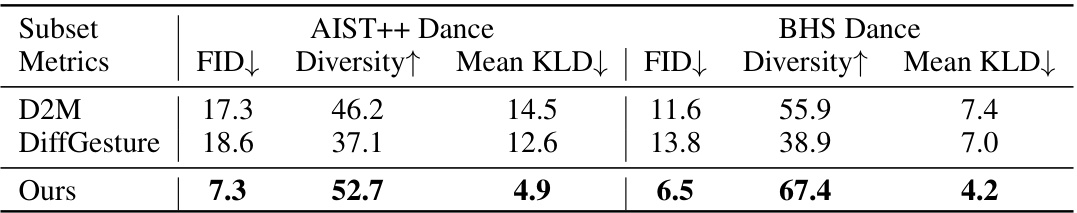

This table presents the quantitative results of music-to-motion generation on two datasets: AIST++ Dance and BHS Dance. The metrics used are FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), measuring the realism of the generated motion, Diversity, reflecting the variety of motions generated, and Mean KLD (Kullback-Leibler Divergence), indicating the difference between the generated motion and the original motion. Lower FID and Mean KLD values are better, whereas higher Diversity is preferred. The table compares the performance of three methods: D2M, DiffGesture, and the authors’ proposed MoMu-Diffusion. MoMu-Diffusion shows significantly better performance in terms of realism and diversity, with lower values on FID and Mean KLD, and higher Diversity scores.

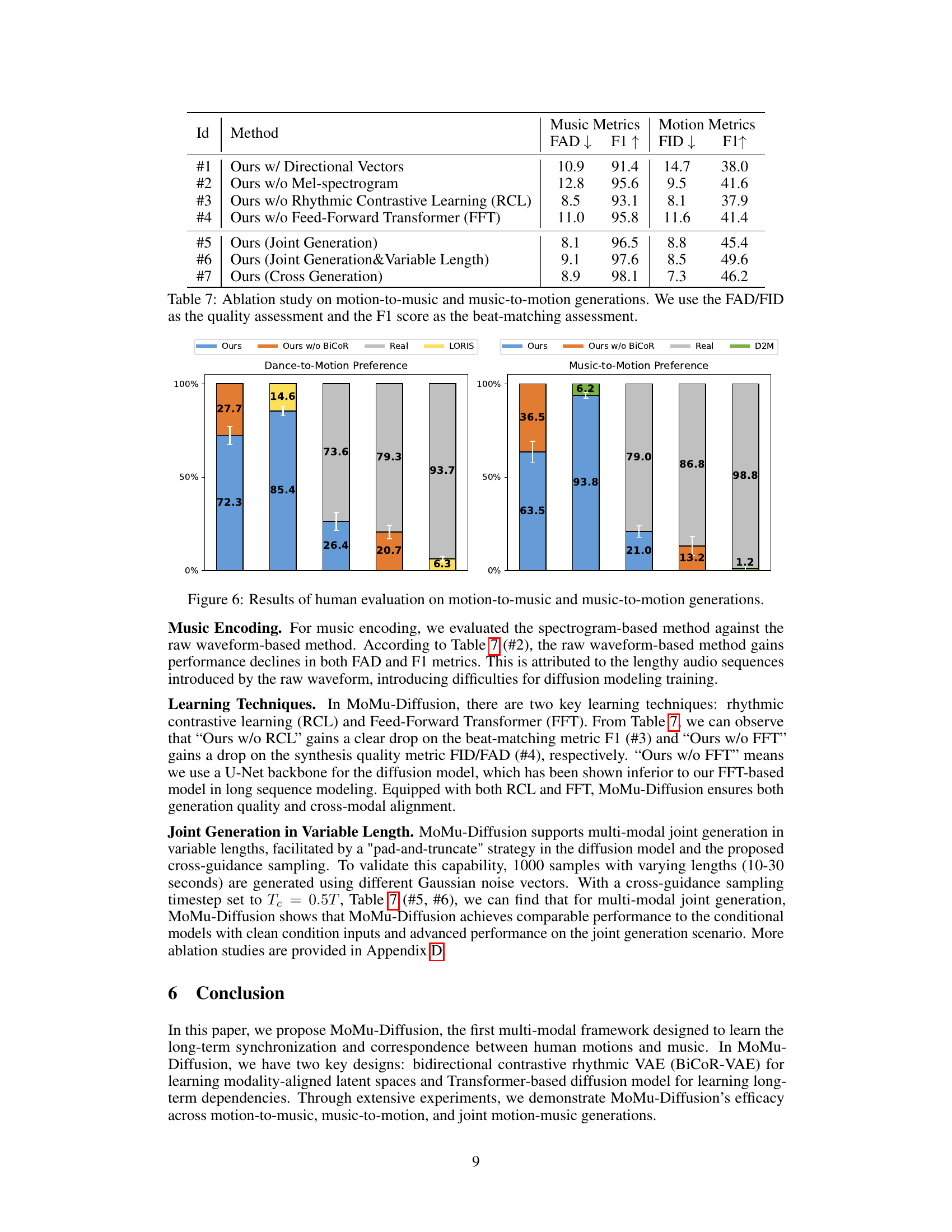

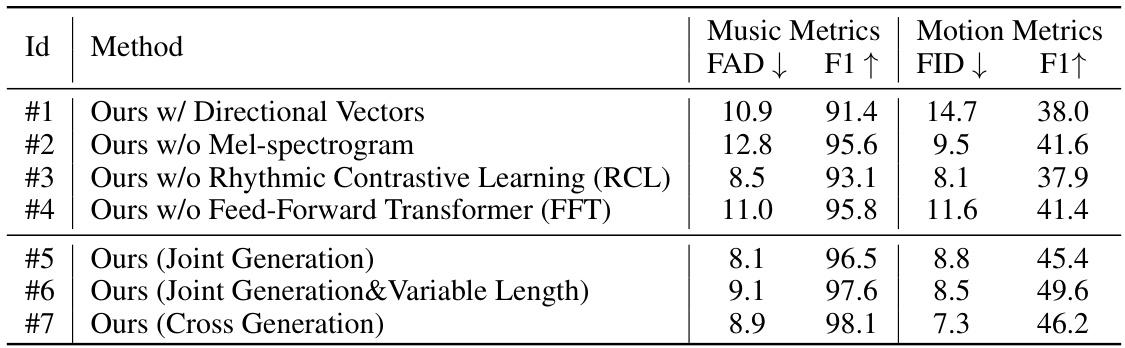

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to evaluate the impact of different components and design choices on the MoMu-Diffusion model. Seven different model variants are compared, each removing or modifying a specific aspect of the model, such as using directional vectors for motion encoding, removing the mel-spectrogram, disabling rhythmic contrastive learning, or removing the feed-forward transformer. The performance of each variant is assessed using FAD and FID scores for music quality and F1 scores for beat-matching accuracy. This allows the authors to isolate and quantify the contribution of different parts of their model.

This table compares MoMu-Diffusion with other state-of-the-art audio-visual generation methods, focusing on its ability to perform joint generation, pretraining, long-term synthesis, and latent space usage. It highlights MoMu-Diffusion’s advantages in these areas compared to other models.

This table compares MoMu-Diffusion with other state-of-the-art audio-visual generation methods, focusing on aspects like joint generation capability, pre-training, long-term synthesis, and the use of latent spaces. It highlights MoMu-Diffusion’s advantages in handling long-term motion-music synthesis and its use of a latent space for multi-modal generation.

This table presents the ablation study results focusing on the impact of the cross-guidance step (Tc) in the MoMu-Diffusion model. It shows how varying the value of Tc (from 0.9T to 0.1T) affects both music quality (FAD and F1 scores) and motion quality (FID and F1 scores) during the joint generation process on the AIST++ Dance dataset. The results highlight the importance of finding the optimal balance between multi-modal alignment and quality of generated output.

Full paper#