↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Zero-shot learning systems aim to classify previously unseen data, but their performance degrades significantly when real-world data distributions shift. This often happens due to changes in class proportions or other unknown attributes, rendering models unreliable. Existing methods typically assume that these shifts are known in advance or occur in a closed-world setting, making them unsuitable for many real-world scenarios.

This research tackles this problem head-on by introducing a novel approach that addresses unknown attribute shifts. The proposed method generates diverse synthetic environments by using hierarchical subsampling techniques to create data sets with various attribute distributions. It then applies an environment balancing criterion, inspired by out-of-distribution (OOD) methods, to learn a representation that performs consistently well across these diverse environments. The results from simulations and real-world datasets confirm that this method improves generalization to diverse class distributions, enhancing robustness and reliability of zero-shot learning systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on zero-shot learning, a field striving for robustness against real-world data shifts. It offers a novel approach to handle unknown attribute shifts, a significant challenge in zero-shot applications. The proposed methodology and findings provide valuable insights and directions for creating robust and reliable zero-shot systems, paving the way for more practical and fair applications of this technology. This is particularly relevant given the increasing emphasis on fairness and robustness in AI.

Visual Insights#

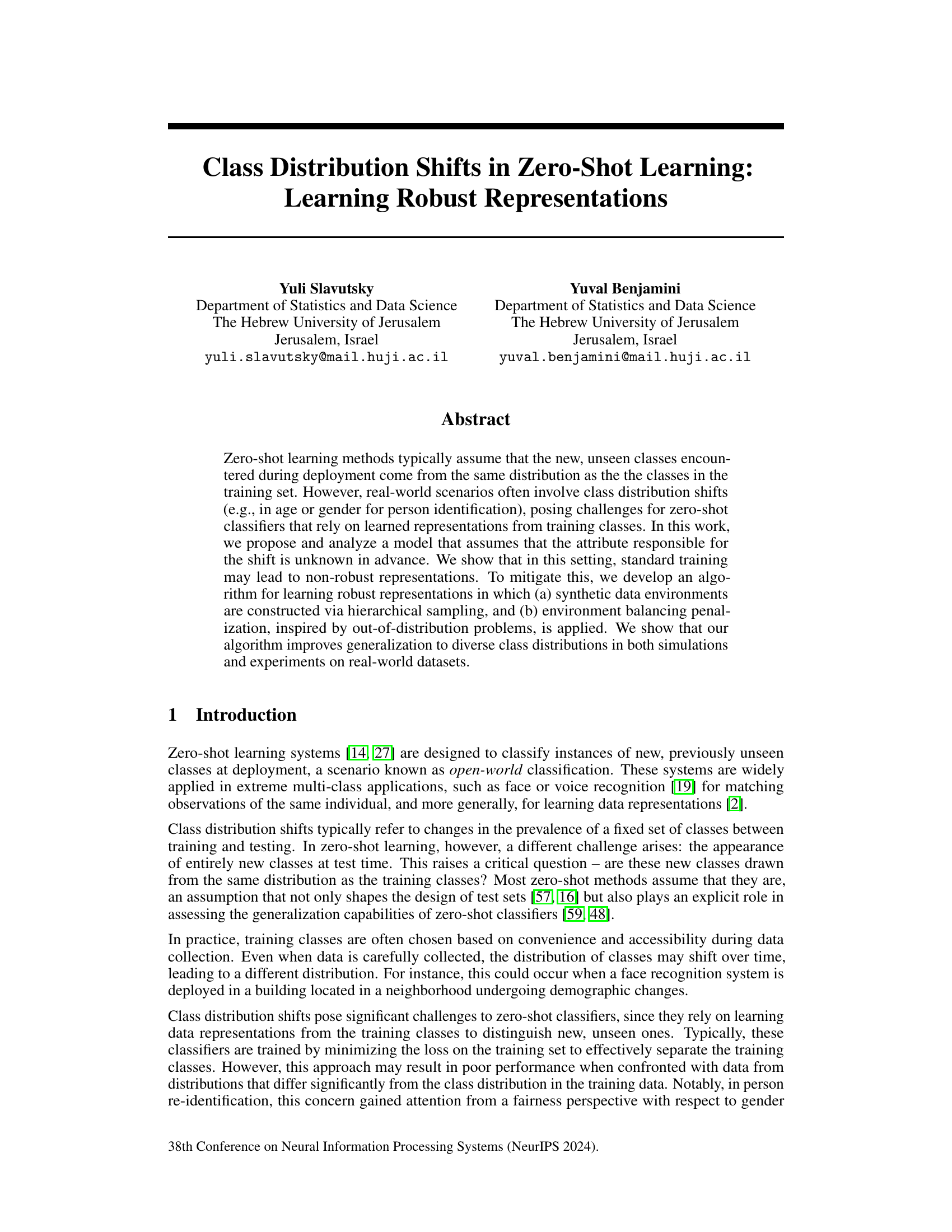

This figure illustrates the parametric model used in the paper to study class distribution shifts in zero-shot learning. It shows a simplified representation of data points from two classes (a1 and a2), each characterized by an attribute. The data points are represented in a three-dimensional space with axes z(0), z(1), and z(2). The axes z(1) and z(2) represent features that allow for optimal separation of classes a1 and a2, respectively, while z(0) shows features shared between the two classes, offering weaker separation. This model helps to understand how class distribution shifts in an unknown attribute A can result in poor performance for zero-shot learning models, even if the conditional distribution of data given the class remains the same.

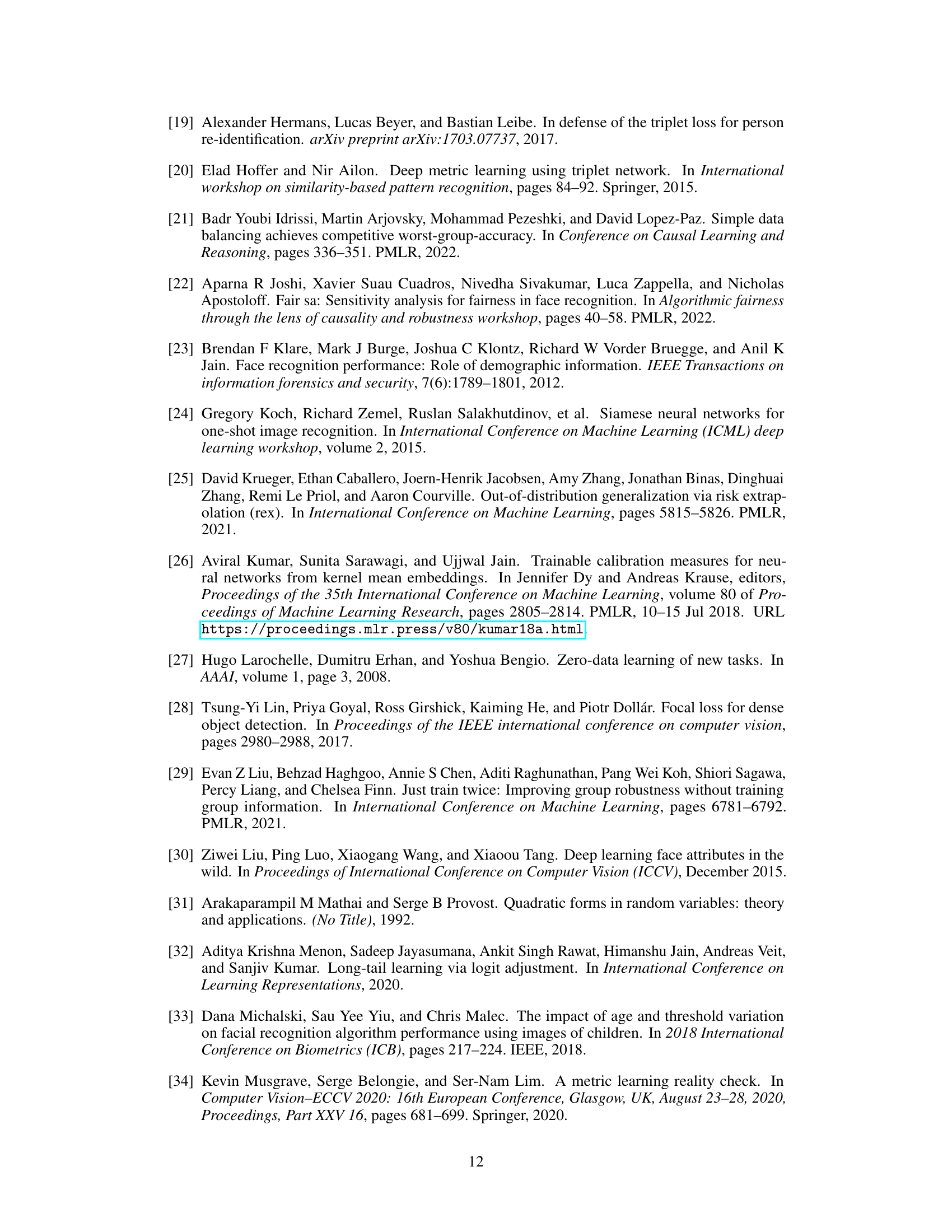

This table presents the results of simulations conducted to evaluate the performance of different methods under both in-distribution and class distribution shift scenarios. The mean AUC and standard deviation are reported for each method across ten repetitions of the experiment, for three different mixture ratios (p = 0.05, 0.1, 0.3). The results show the impact of class distribution shift on the performance of various methods. The best performing method for each scenario is highlighted in bold.

In-depth insights#

Robust Zero-Shot#

The concept of “Robust Zero-Shot Learning” tackles the limitations of standard zero-shot learning models, which often struggle with real-world data distribution shifts. Standard zero-shot learning assumes that training and testing data come from the same distribution, but this is rarely true in practice. A robust approach addresses this by creating models that are less sensitive to these unexpected changes. This involves developing techniques to handle unseen classes and variations in class distributions at deployment. Methods for achieving robustness include using synthetic data augmentation, carefully balancing the loss function across diverse training conditions (environment balancing), or incorporating regularization to promote stable representations. The ultimate goal is to build a zero-shot system that generalizes well beyond the narrow confines of the training dataset, exhibiting reliable performance under diverse and challenging conditions. The key innovation lies in focusing on unknown attributes responsible for the shift, making the approach more broadly applicable than methods which depend on prior knowledge of these factors.

Class Shift Effects#

The phenomenon of class distribution shifts, where the prevalence of certain classes differs significantly between training and testing data, poses a substantial challenge to zero-shot learning models. Standard zero-shot learning approaches often assume that the new, unseen classes encountered during deployment are drawn from the same distribution as those in the training set. However, real-world scenarios frequently violate this assumption, leading to performance degradation. This paper investigates the impact of these class distribution shifts, especially when the shift’s underlying attribute (e.g., age, gender) is unknown. The analysis reveals that standard training techniques may yield representations lacking robustness against such shifts, leading to underperformance on unseen classes with different distribution characteristics. The authors then propose a novel method to mitigate this effect by creating diverse synthetic environments via hierarchical sampling and employing an environment balancing penalty to enhance model robustness and generalization to various class distributions.

Synthetic Env.#

The heading ‘Synthetic Env.’ likely refers to the creation of artificial datasets or environments to augment training data for zero-shot learning. This is a crucial technique for addressing class distribution shifts, as it allows the model to learn representations robust to unseen data distributions. By generating synthetic environments with varying class attribute distributions, the model is exposed to diverse scenarios which it may encounter during real-world deployment. This technique is particularly valuable in zero-shot learning since the true attribute responsible for class distribution shifts is often unknown during training. The effectiveness of this approach hinges on the ability to generate realistic and representative synthetic data that faithfully reflects the characteristics of real-world data, but with controlled variations in class distribution. The use of hierarchical sampling in constructing these synthetic environments further increases their diversity, ensuring that the algorithm is exposed to a wide range of data variations. This methodology allows the researchers to train models that generalize better to novel unseen classes and are less susceptible to poor performance due to unexpected distribution shifts.

VarAUC Penalty#

The VarAUC penalty, a core contribution of this research, addresses the limitations of existing methods for handling class distribution shifts in zero-shot learning. Existing penalties often focus on balancing losses across environments, which may not effectively reflect performance changes in deep metric learning. VarAUC uniquely targets AUC scores, a robust metric for representation quality, making it particularly suitable for open-world classification. By calculating the variance of AUC across multiple synthetic environments, VarAUC incentivizes learning representations that generalize well to diverse class distributions. Unlike methods like IRM or VarREx, which directly penalize loss variance, VarAUC penalizes performance variance, leading to more robust representations that are less sensitive to unforeseen shifts in class composition.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the framework to handle multi-attribute shifts is crucial, moving beyond the binary attribute examined here. This involves developing more sophisticated methods for generating synthetic environments that effectively capture the complexities of interacting attributes. Investigating the impact of different loss functions and regularization techniques on robustness is also warranted, potentially revealing improved strategies for balancing performance across diverse environments. Furthermore, a deeper theoretical analysis could provide more precise conditions under which the proposed approach guarantees robustness, and potentially lead to improved algorithms. Finally, applying the methodology to a wider range of zero-shot learning tasks and datasets will validate its generalizability and highlight potential limitations, ultimately refining the approach for broader applicability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the parametric model used in the paper to demonstrate how class distribution shifts can affect zero-shot learning. It shows data points from two different class types (a1 and a2) in a three-dimensional space. The axes z(0), z(1), and z(2) represent different features or dimensions. Classes of type a1 are best separated along the z(1) axis (red), while classes of type a2 are best separated along the z(2) axis (green). The z(0) axis (black) provides some separation, but less effectively than the other two axes. This illustrates how learning representations that work well for the training data (where one type of class might be more prevalent), may not perform well when the class distribution shifts at test time.

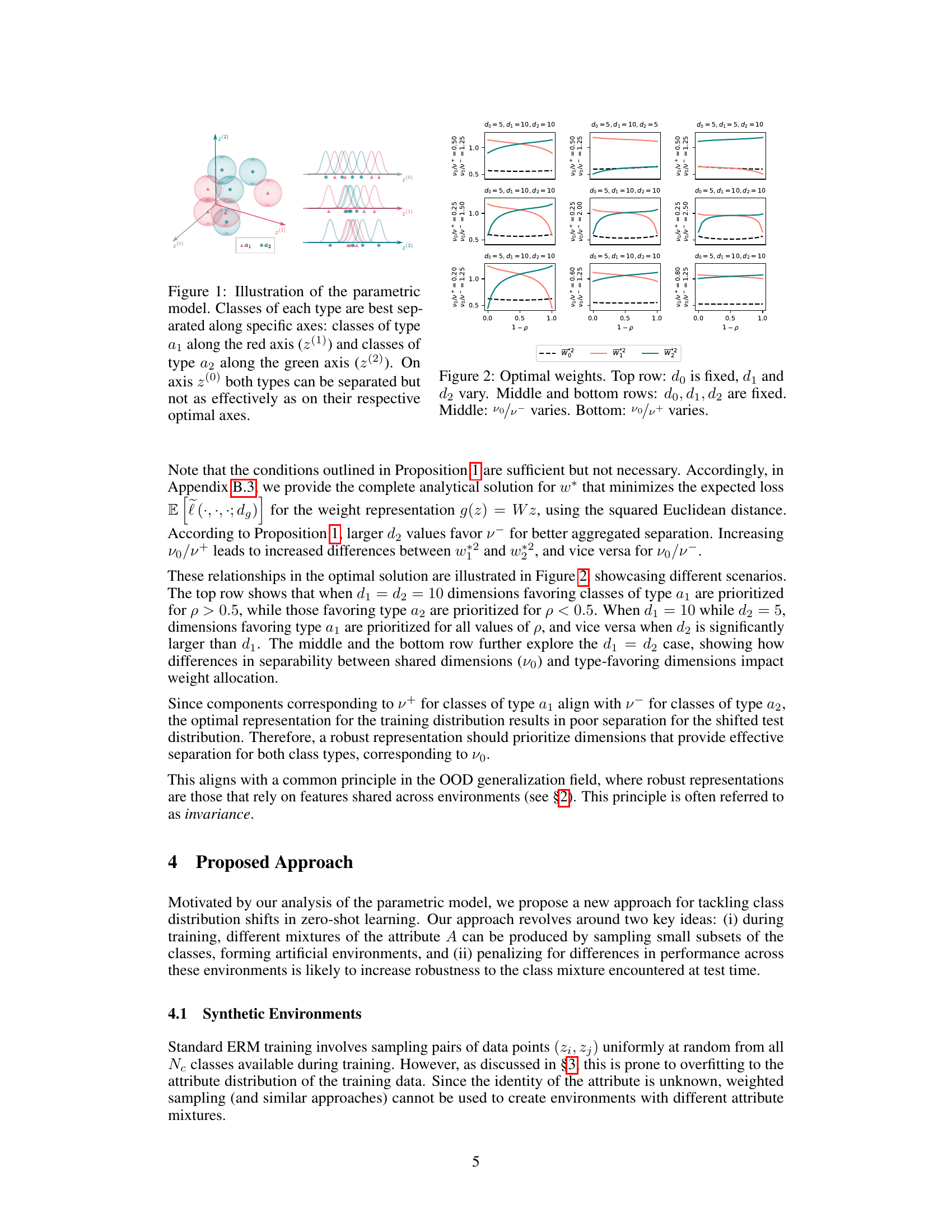

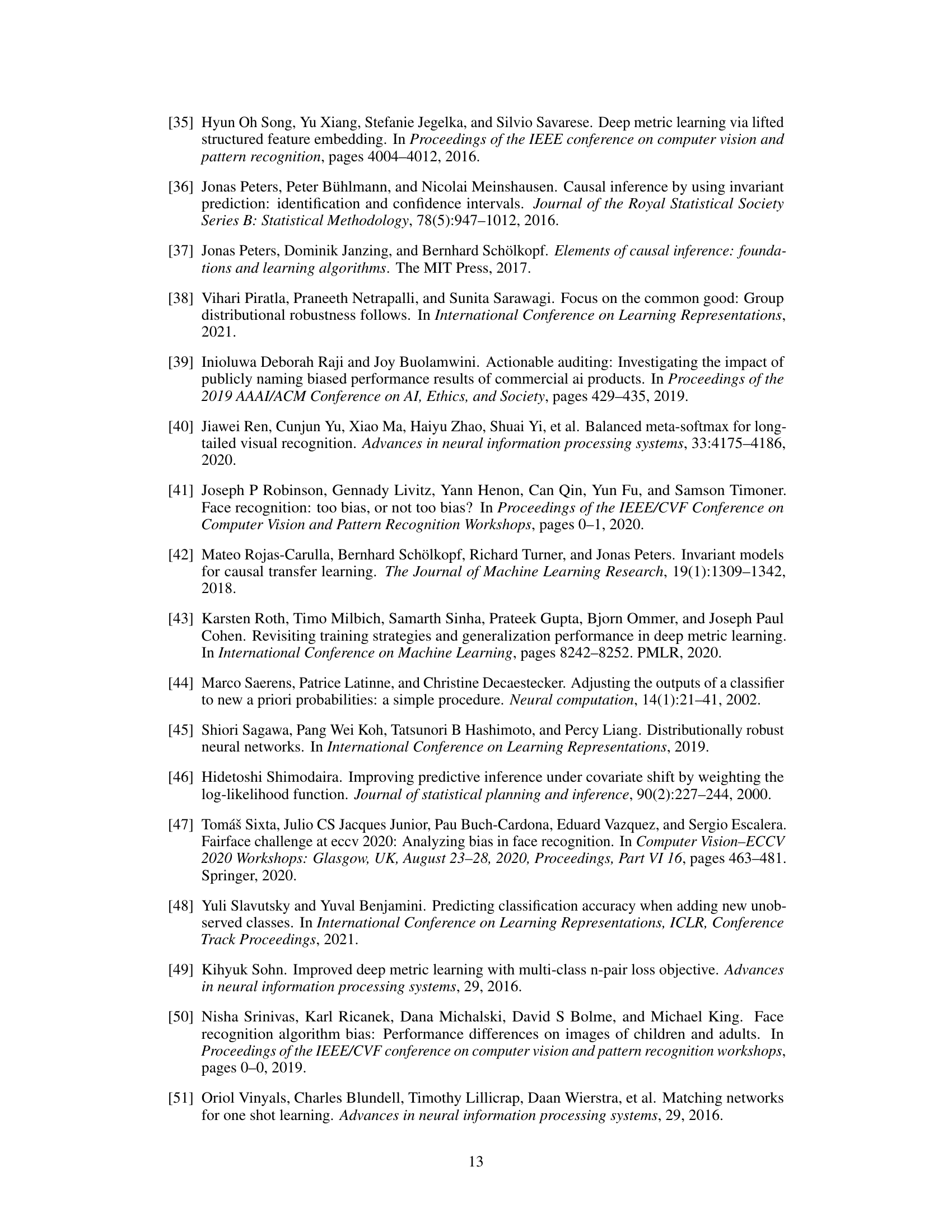

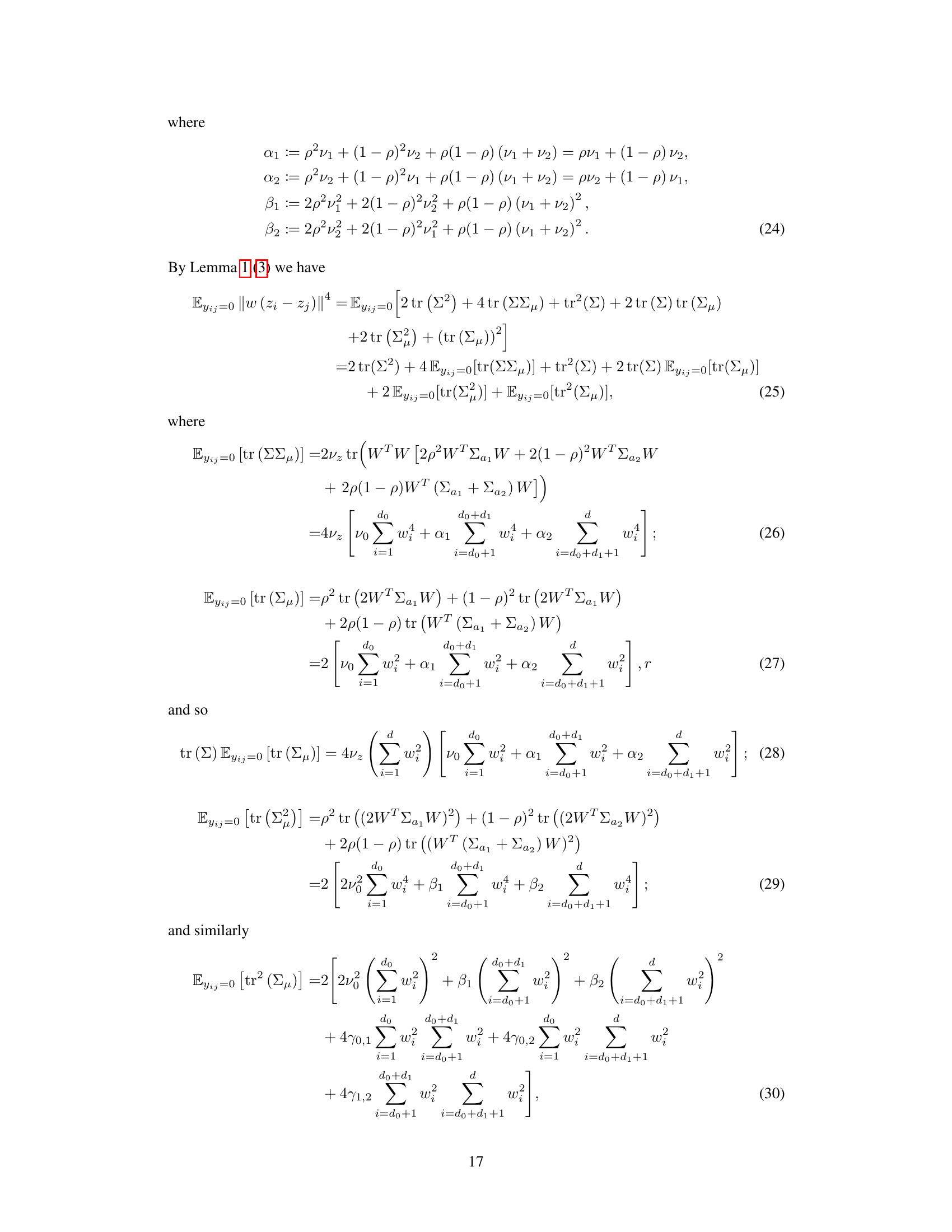

This figure displays the optimal weights obtained by minimizing the expected loss in a parametric model of class distribution shifts in zero-shot learning. The plots show how the optimal weights (w*², w₁², w₂²) change depending on several factors: (Top row) varying the number of dimensions d₁ and d₂ that allow good separation for classes of different types while keeping the number of shared dimensions (d₀) constant. (Middle and Bottom rows) Varying the variance ratios (v₀/v⁻ and v₀/v⁺ respectively) while maintaining constant number of dimensions (d₀, d₁, d₂). The x-axis represents the proportion (1-p) of type a2 classes in the data, while the y-axis represents the relative magnitude of the optimal weights.

This figure illustrates the hierarchical sampling method used to create diverse synthetic environments for training. It starts with a set of classes, some of which are in the minority. Subsets of these classes are then randomly sampled to form the environments. The composition of these environments varies, with some having a higher proportion of minority classes than others, simulating real-world class distribution shifts. Finally, pairs of data points are sampled within and between classes to create training examples for each environment.

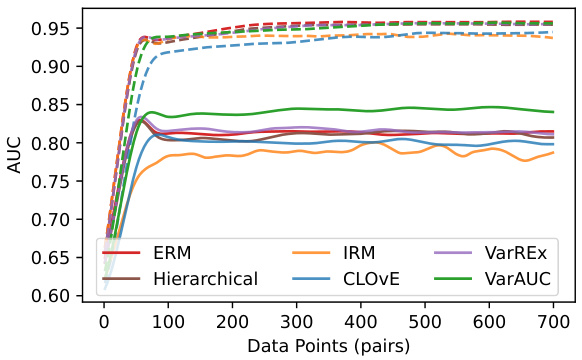

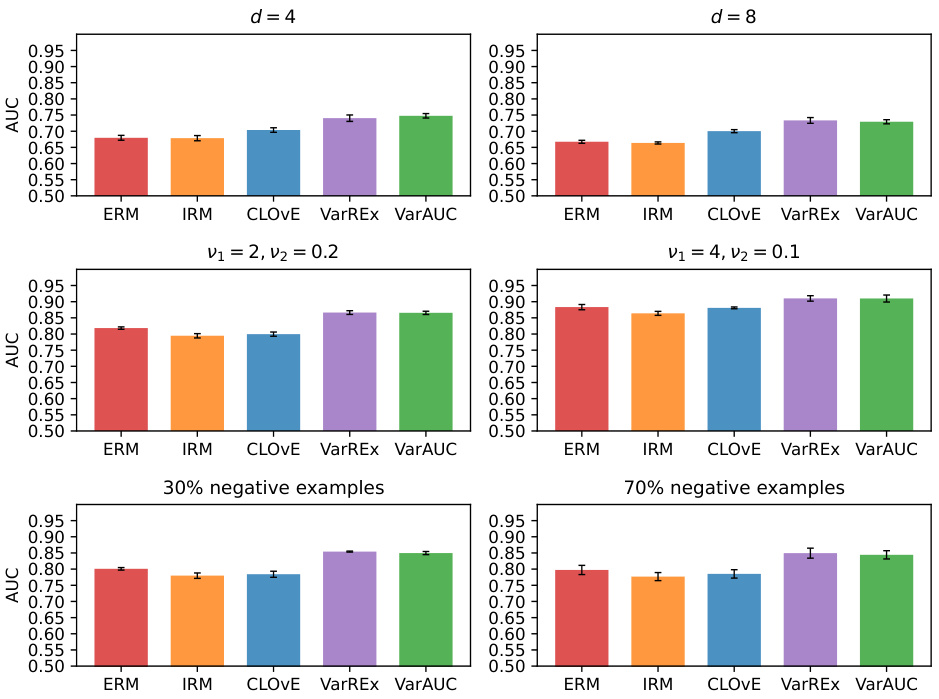

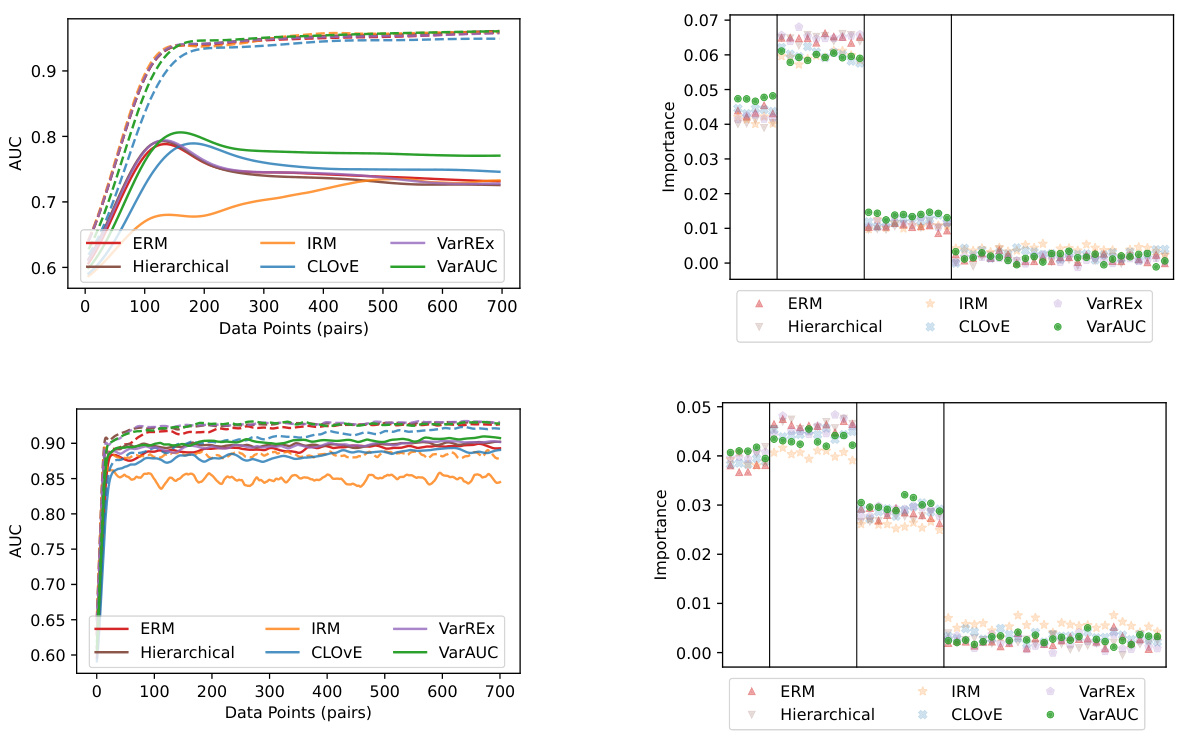

This figure shows the average AUC (Area Under the Curve) across 10 simulation runs, comparing different methods for handling class distribution shifts in zero-shot learning. The x-axis represents the number of data points (pairs) used for training. The y-axis shows the AUC. Solid lines depict the performance under a class distribution shift (from 0.9 in training to 0.1 in testing), while dashed lines show the in-distribution performance (no shift, both training and testing at 0.9). The figure demonstrates that the proposed VarAUC method outperforms other methods in terms of robustness to the shift, maintaining comparable performance to the other methods when there is no shift.

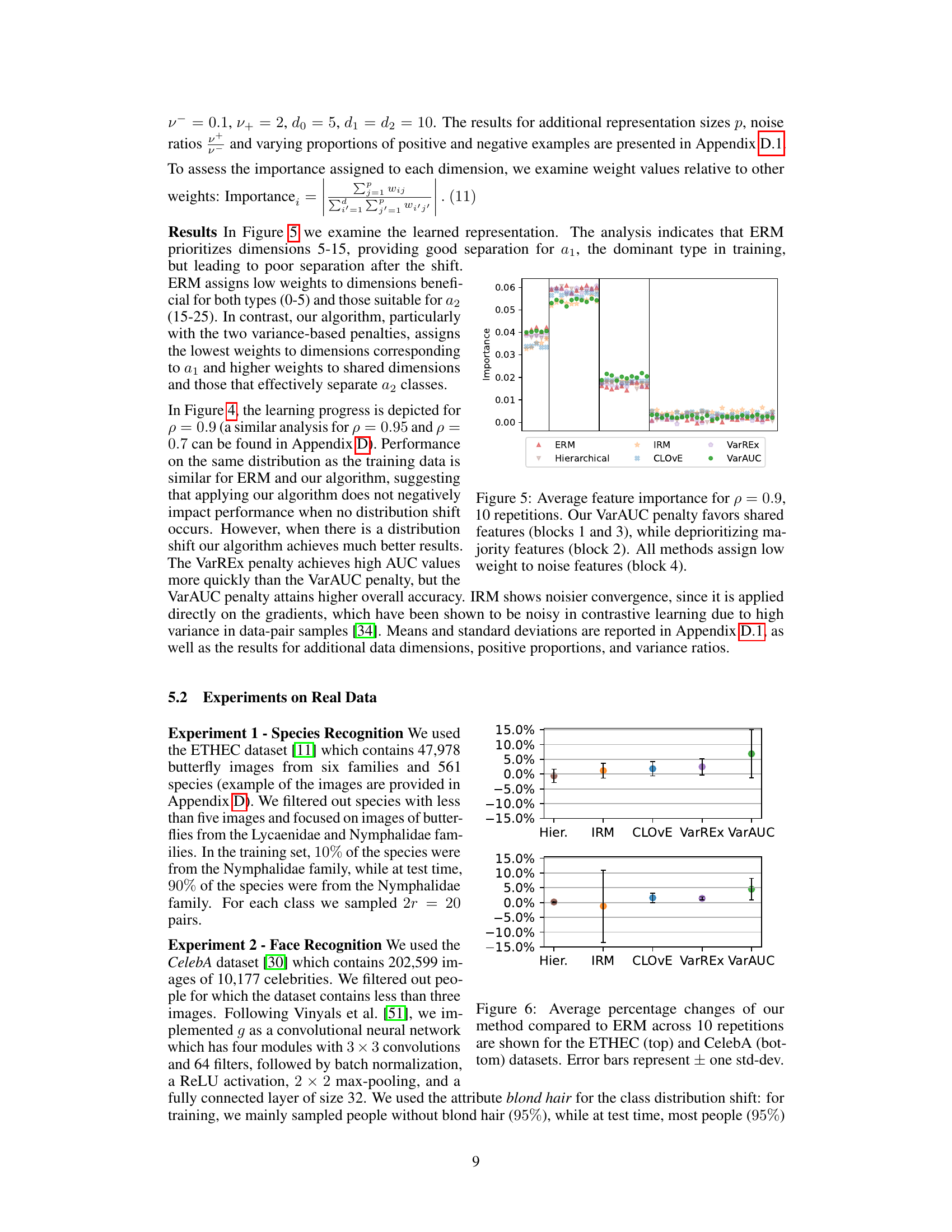

The figure shows the average feature importance across ten repetitions of the simulation for a majority attribute proportion of 0.9. The VarAUC method prioritizes features that are useful for separating classes of both types (shared features), while other methods prioritize features primarily useful for the majority class in the training data. Noise features receive low weight from all methods.

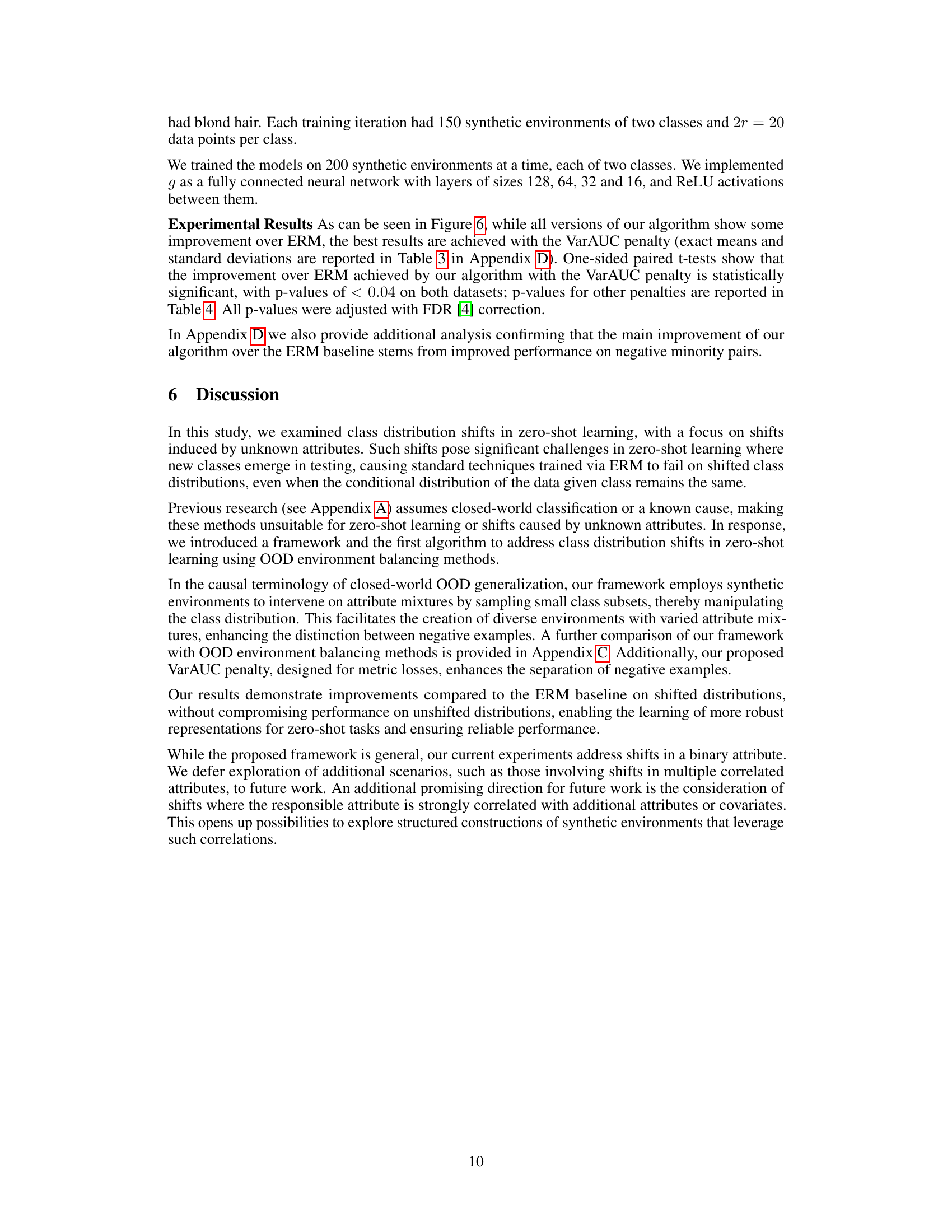

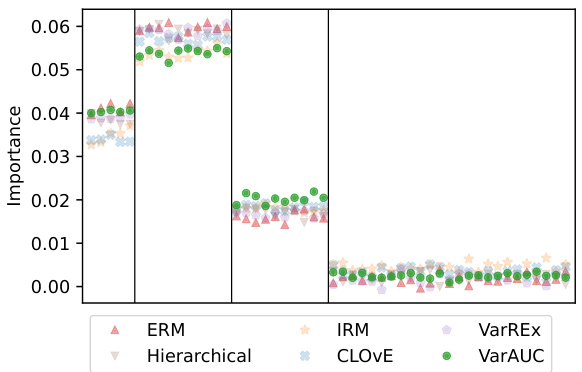

This figure compares the performance of the proposed method against the ERM baseline on two real-world datasets: ETHEC (species recognition) and CelebA (face recognition). The y-axis represents the percentage change in AUC, with positive values indicating improvement over ERM. The x-axis shows different methods including the proposed method with different penalties. The top panel displays the results for ETHEC, and the bottom for CelebA. Error bars depict the standard deviation across ten repetitions of the experiments.

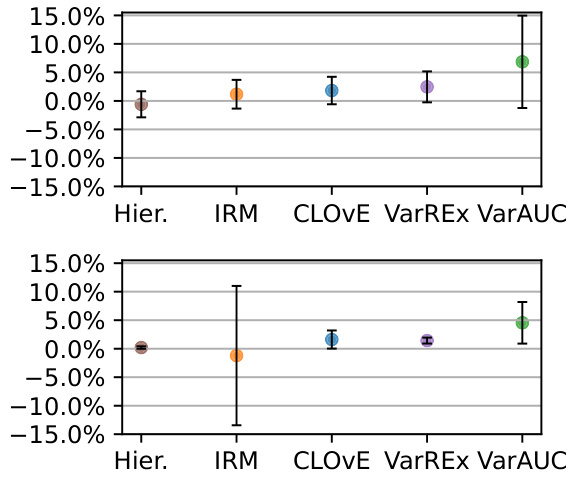

This figure displays the results of additional simulations conducted to further investigate the impact of various factors on the performance of the proposed algorithm. The top row explores the effect of increasing the dimensionality of the representation space. The middle row examines the effect of varying the ratio of attribute variances between training classes. The bottom row assesses the impact of having an imbalanced number of positive and negative examples during training. Across all rows, the algorithm’s performance in terms of AUC (Area Under the Curve) is compared across different methods and under various conditions.

This figure presents simulation results for different proportions of the majority attribute in training data (p = 0.05 and p = 0.3). The left panels show the average AUC over 10 simulation runs, comparing the performance of various methods on both in-distribution data (same distribution as training) and out-of-distribution data (shifted distribution). Dashed lines represent in-distribution results, and solid lines represent out-of-distribution results. The right panels show the average feature importance, indicating which features each method prioritizes. The figure demonstrates the performance and feature weighting behavior of the different methods under varying levels of distribution shift.

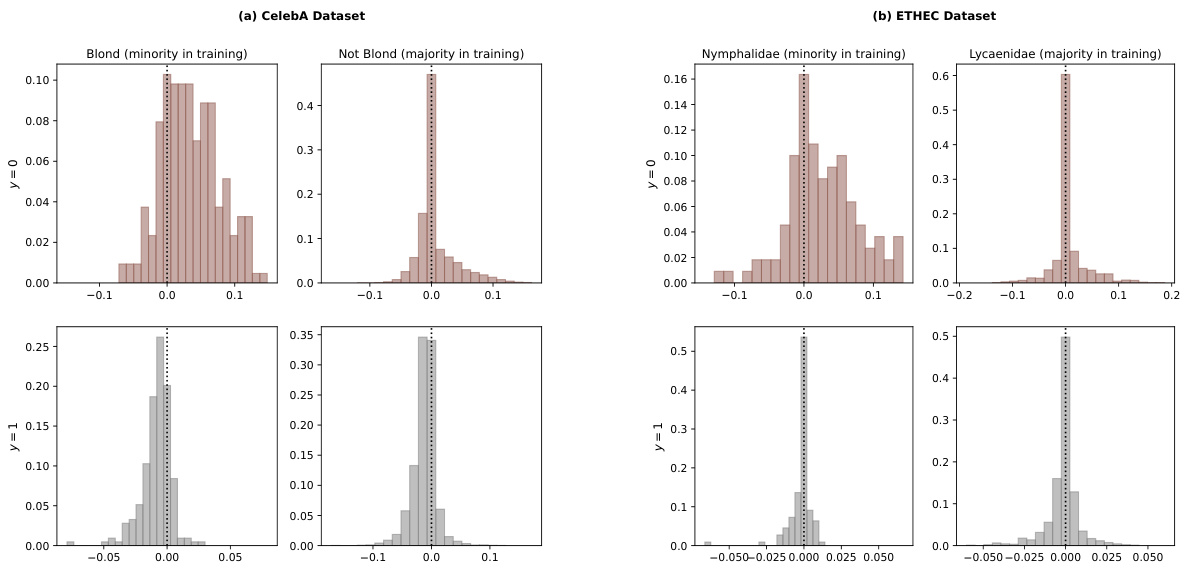

This figure presents histograms visualizing the differences in loss between the ERM baseline and the proposed algorithm (with VarAUC penalty) across four groups: minority negative pairs, minority positive pairs, majority negative pairs, and majority positive pairs. The histograms are separated by dataset (CelebA and ETHEC) and show whether the ERM method resulted in higher or lower loss compared to the proposed approach.

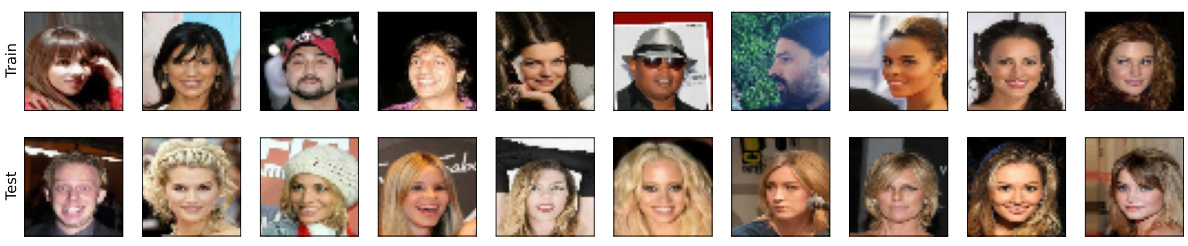

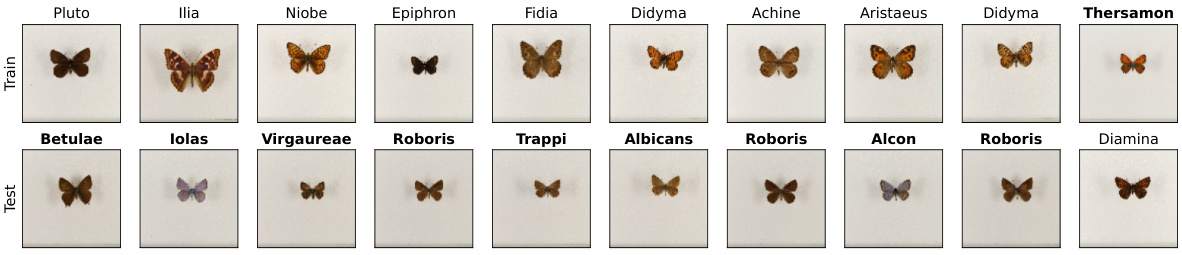

This figure shows example images from the CelebA dataset used in the paper’s experiments. The top row displays a sample of the training data, which is predominantly composed of individuals without blond hair (95%). The bottom row shows a sample of the test data, which is predominantly composed of individuals with blond hair (95%). This illustrates the class distribution shift used to evaluate the robustness of the proposed zero-shot learning approach.

This figure illustrates the parametric model used in the paper to demonstrate the effect of class distribution shifts in zero-shot learning. The model assumes that data points are sampled from a Gaussian distribution, with the mean determined by the class and an attribute A indicating the type of class. The figure shows how the optimal separation between classes of different types depends on the relative proportions of types in the training data, illustrating how the shift in class distribution can lead to poor performance in zero-shot learning settings.

More on tables

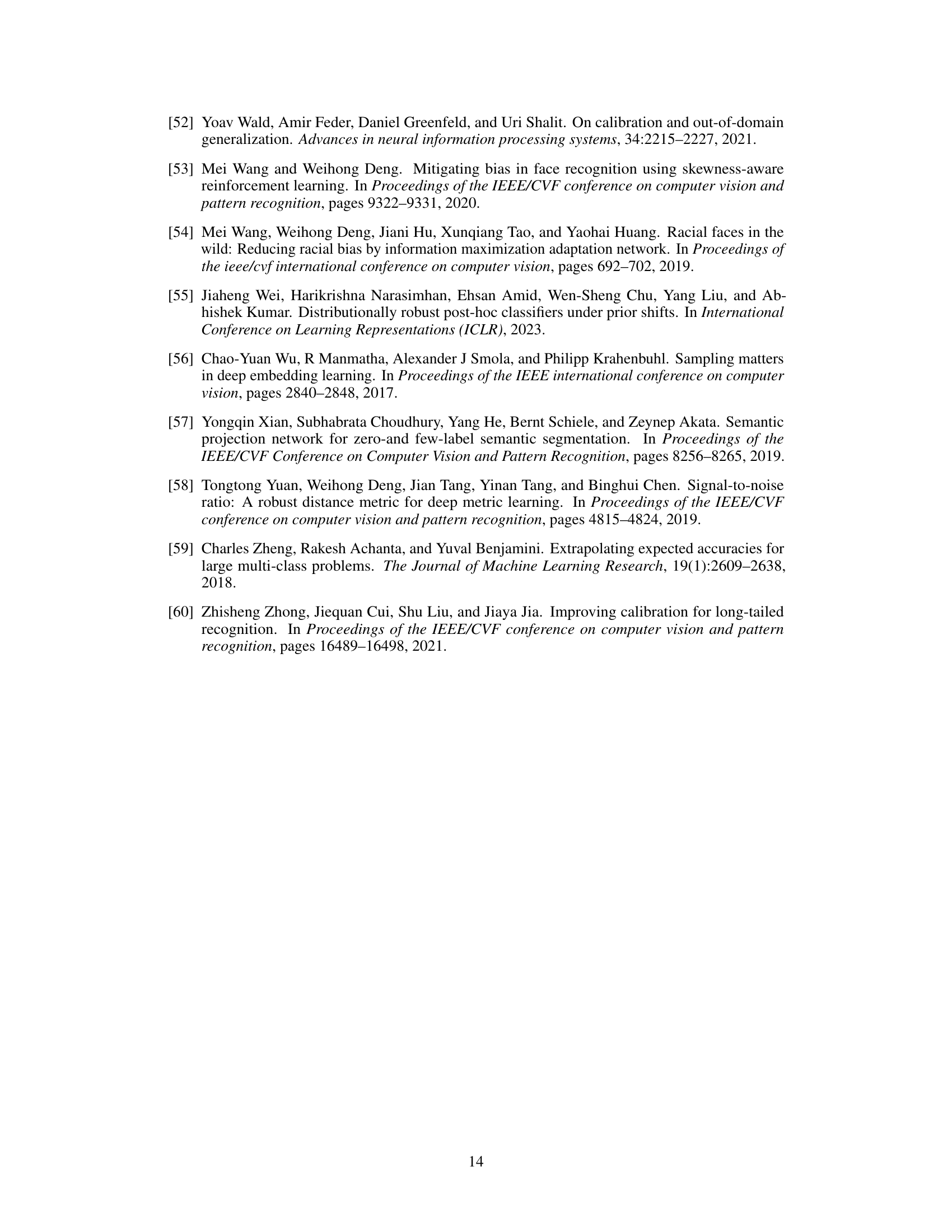

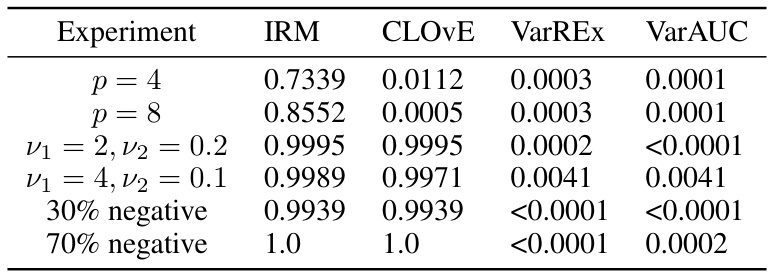

This table displays the FDR (False Discovery Rate) adjusted p-values obtained from statistical tests performed on the results shown in Figure 7. The tests assess the statistical significance of the differences between the performance of the proposed VarAUC method and other methods (IRM, CLOVE, VarREx) under various experimental conditions involving changes in representation size (p=4, p=8), attribute variance ratios (ν₁=2, ν₂=0.2; ν₁=4, ν₂=0.1), and the proportion of negative examples (30%, 70%). Small p-values indicate statistically significant improvements of VarAUC over other methods.

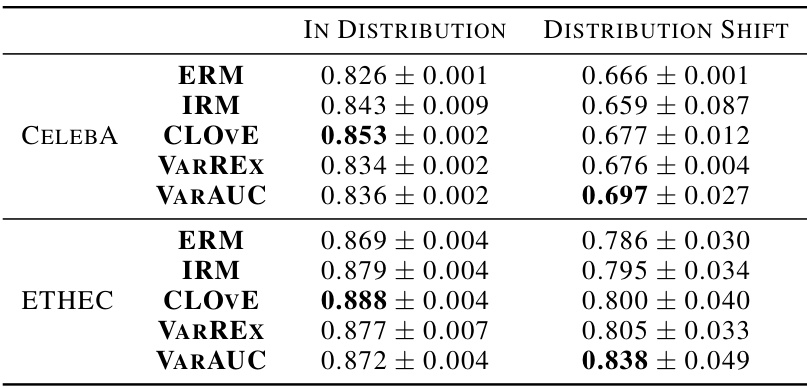

This table presents the results of experiments on real-world datasets (CelebA and ETHEC). It shows the average AUC (Area Under the Curve) and standard deviation across five repetitions for each method (ERM, Hierarchical, IRM, CLOVE, VarREx, and VarAUC) under two scenarios: in-distribution (where the test data comes from the same distribution as the training data) and distribution shift (where the test data has a different class distribution than the training data). The best performing method for each scenario is highlighted in bold. The results demonstrate the relative performance of the proposed algorithm (VarAUC) compared to existing methods in handling class distribution shifts.

This table presents the results of statistical significance tests comparing the performance of the proposed algorithm (with different penalty methods) against the standard ERM baseline. Specifically, it shows the adjusted p-values from one-sided paired t-tests for both the CelebA and ETHEC datasets. These p-values indicate whether the improvements in AUC observed for the proposed approach (using IRM, CLOVE, VarREx, and VarAUC penalties) over the ERM baseline are statistically significant.

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the simulations and the CelebA and ETHEC experiments. For each method (ERM, IRM, CLOVE, VarREx, VarAUC), the learning rate (η), regularization factor (λ), and network weight regularizer are specified. Note that the ERM method does not use regularization.

Full paper#