↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are powerful but suffer from issues like hallucinations and biases, stemming from the complex way knowledge is stored and accessed. Existing research often focuses on individual model components in isolation, hindering a complete understanding of their knowledge processing mechanisms. This paper introduces the novel concept of “knowledge circuits” – interconnected subgraphs within the LLM that collectively represent and utilize knowledge.

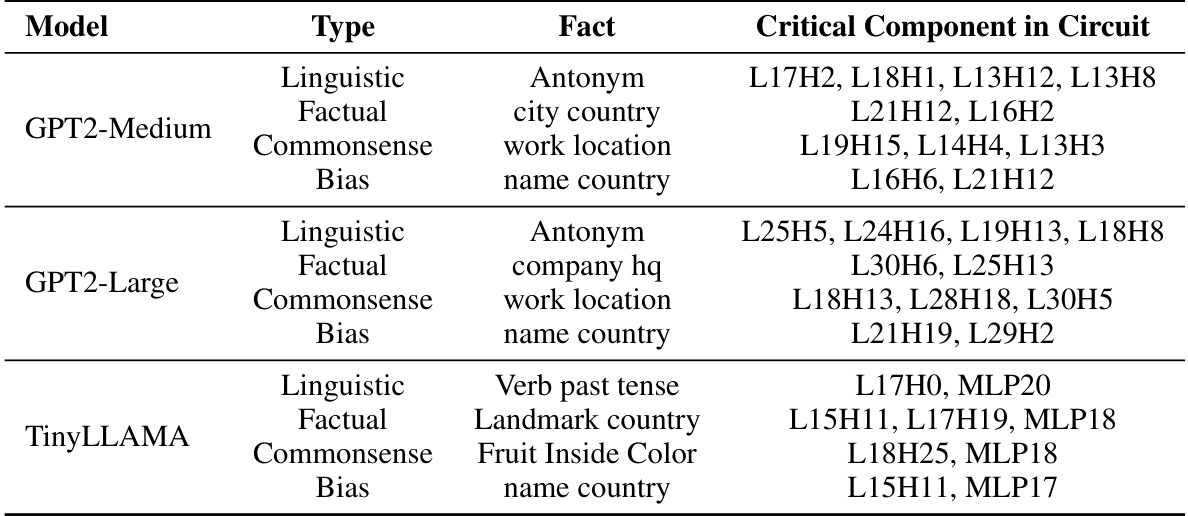

This research investigates knowledge circuits in LLMs using GPT-2 and TinyLLAMA. They use circuit analysis to interpret model behavior, like hallucinations which occur when the model struggles to utilize stored knowledge effectively. They also explore how current knowledge editing methods affect these circuits, revealing limitations. The study demonstrates that the circuit approach provides new insights into LLM behavior and can lead to improved knowledge editing techniques, resolving current limitations and enhancing LLM safety.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs). It offers novel insights into how LLMs store and utilize knowledge, moving beyond isolated components analysis. The concept of knowledge circuits provides a framework for improved LLM design and facilitates a better understanding of LLM behaviors like hallucination and in-context learning. This research opens new avenues for mechanistic interpretability and more effective knowledge editing techniques.

Visual Insights#

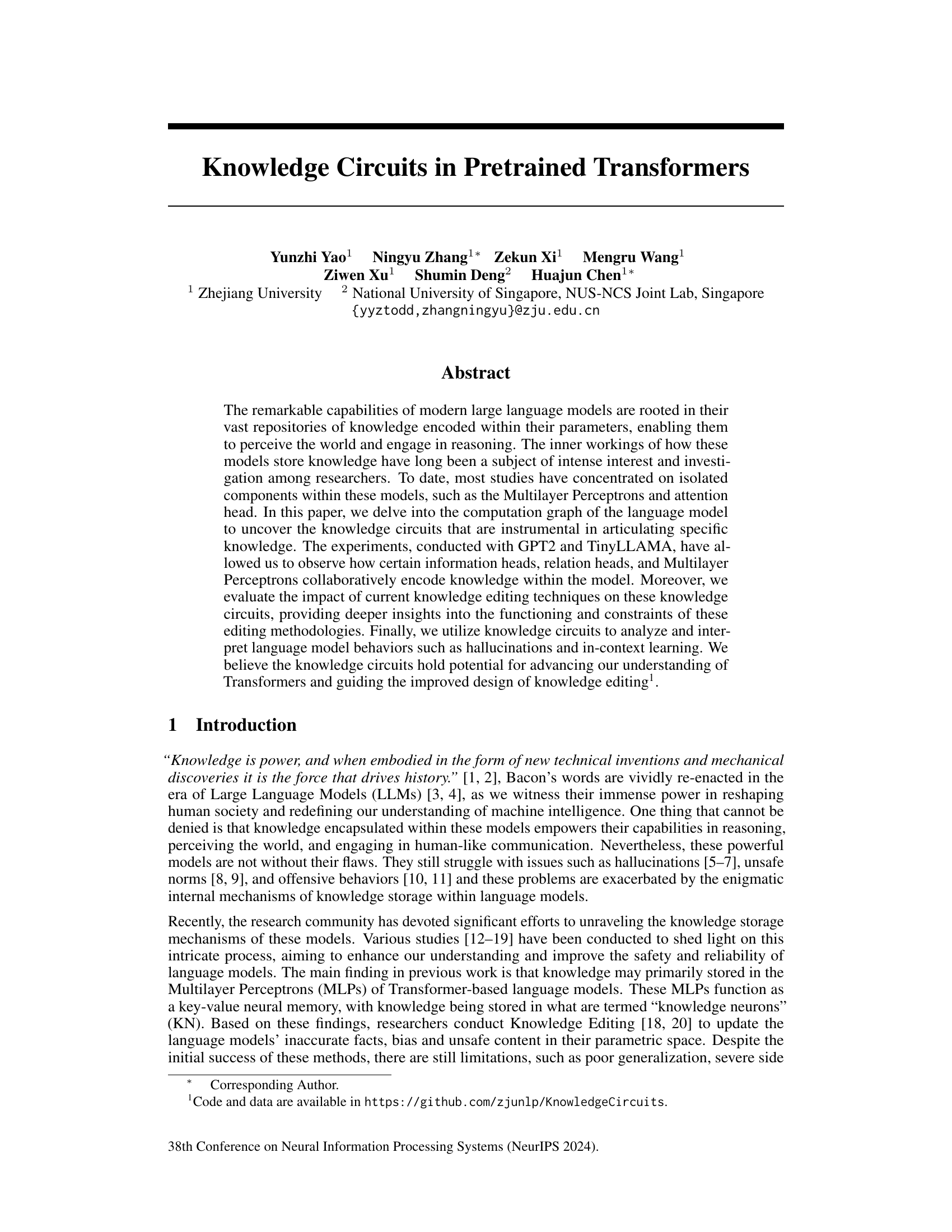

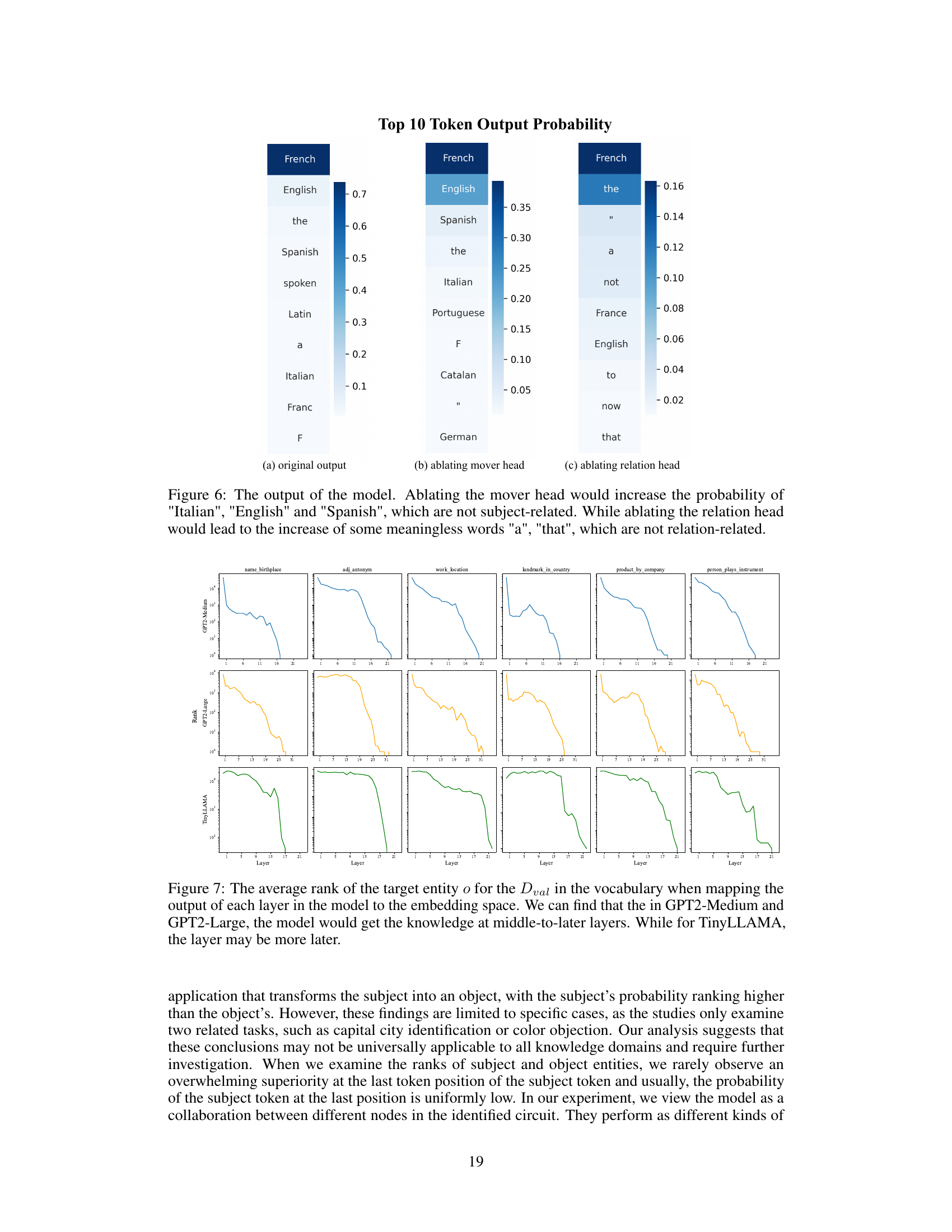

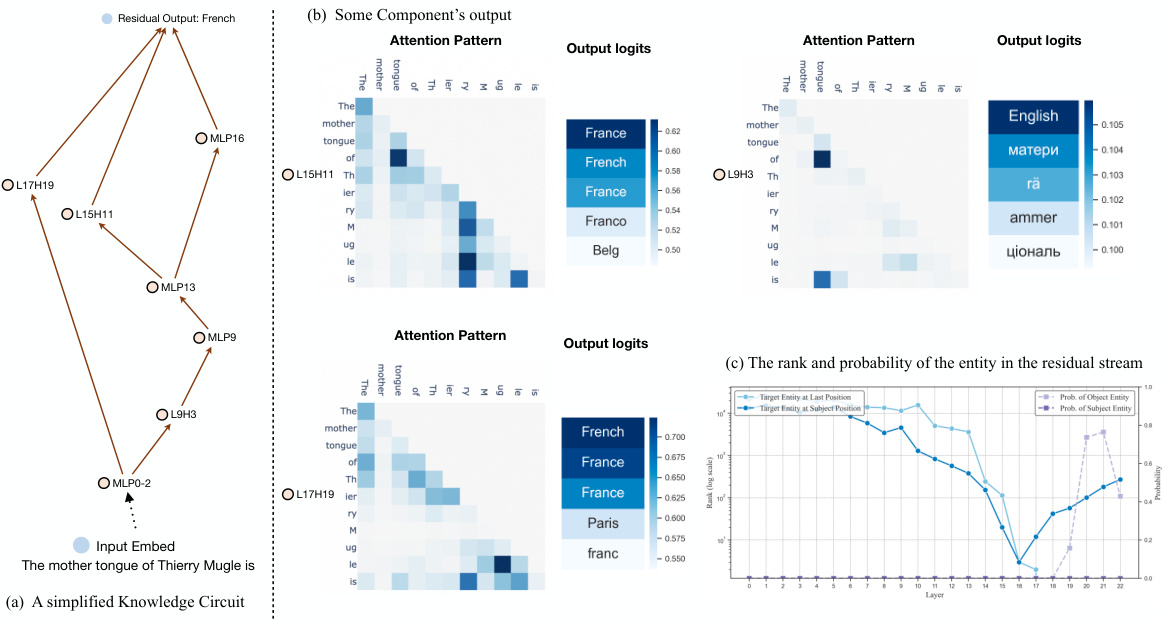

This figure illustrates the knowledge circuit for the sentence ‘The official language of France is French’ in the GPT-2 Medium model. The left side shows a simplified version of the circuit, highlighting key components like attention heads (e.g., L15H0) and Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs, e.g., MLP12) and how information flows between them. The right side shows the attention patterns and output logits for several specific attention heads, visualizing how these components contribute to the final prediction of the word ‘French’. It demonstrates the collaborative encoding of knowledge within the language model.

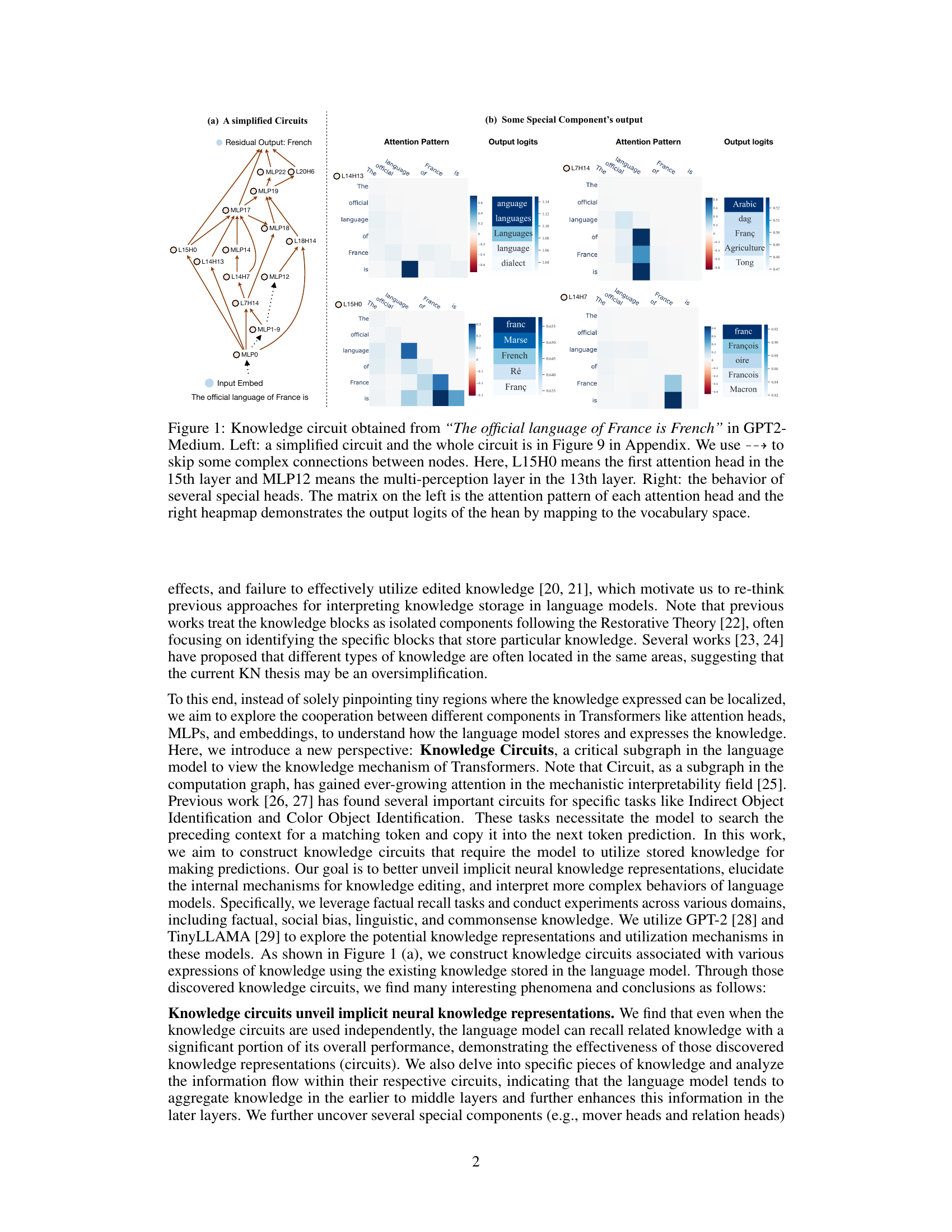

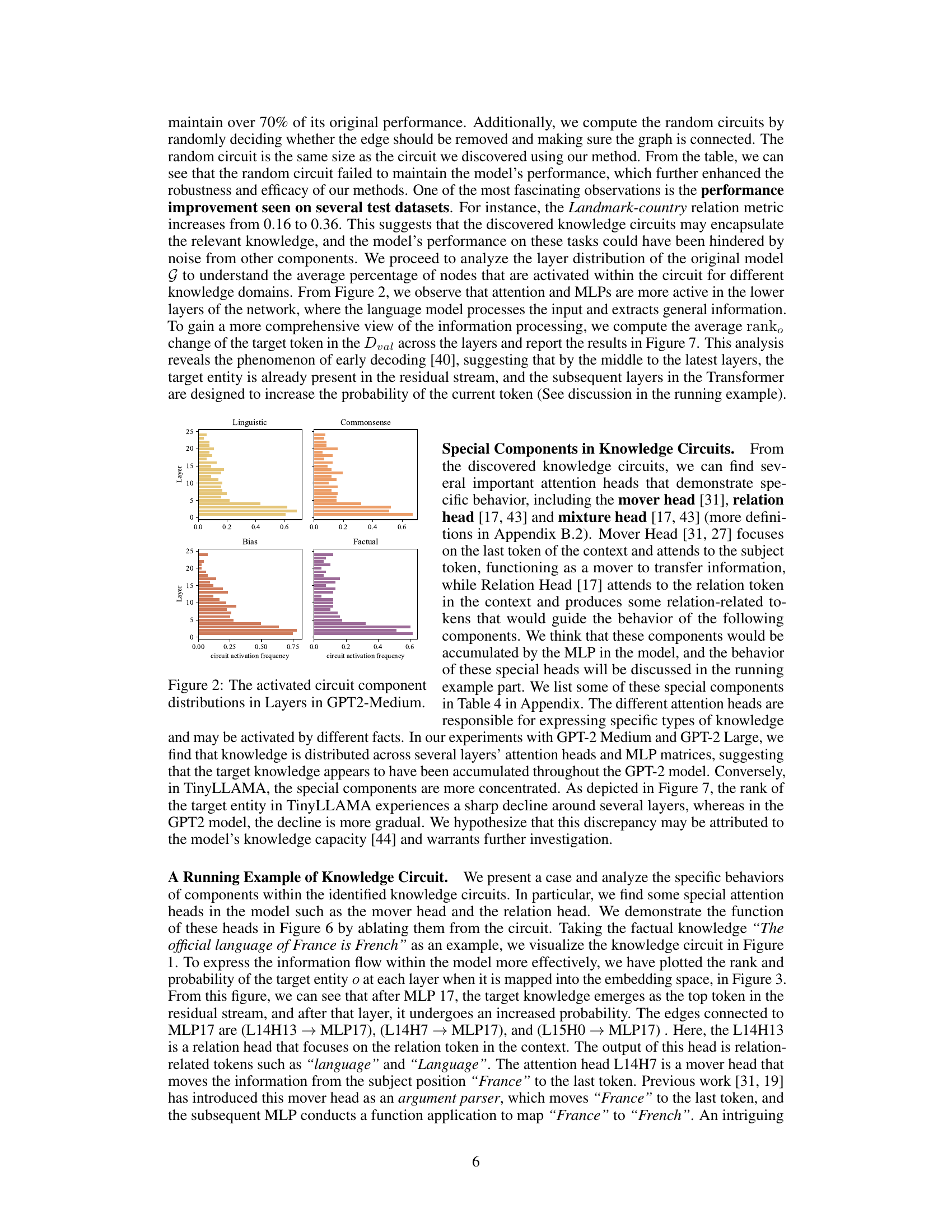

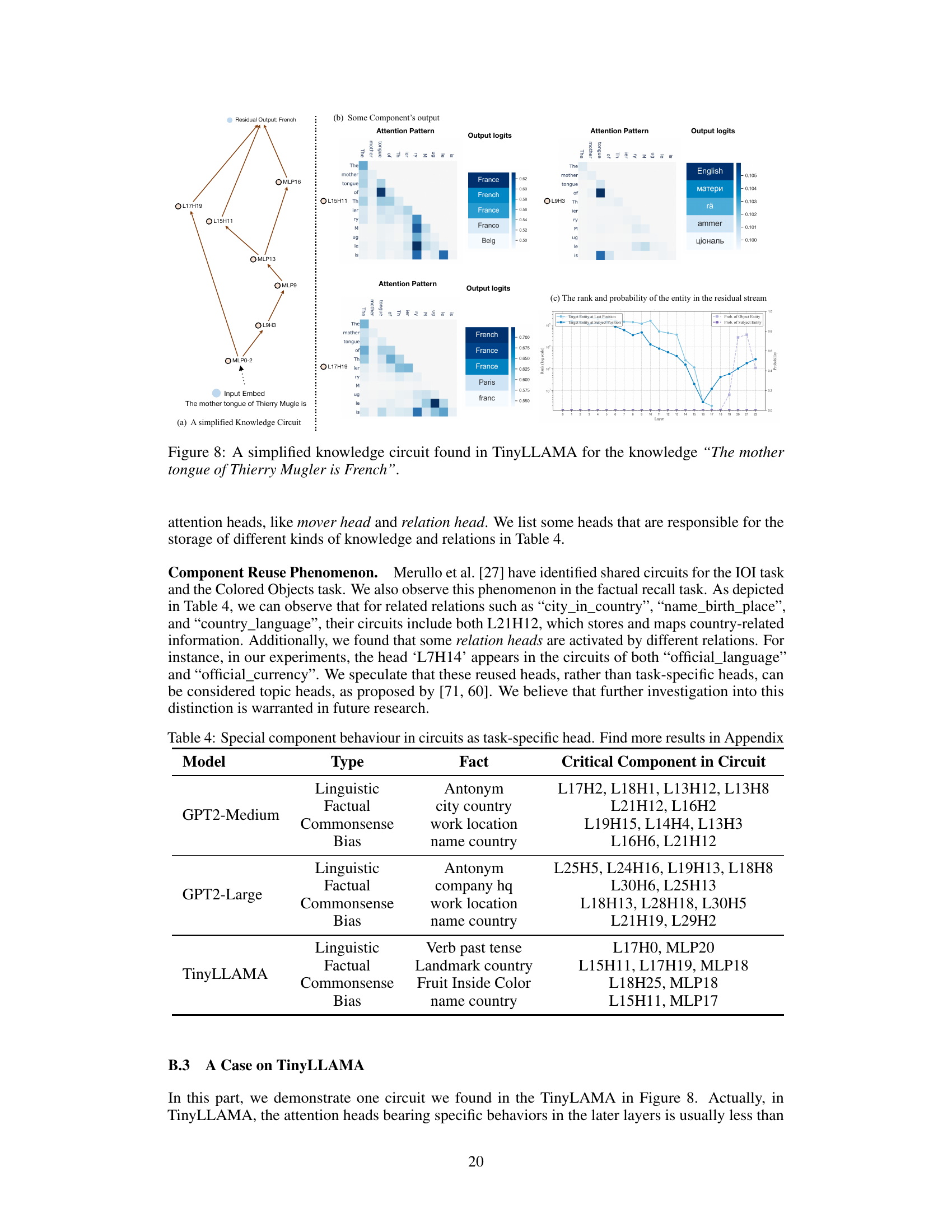

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the performance of knowledge circuits in the GPT2-Medium language model. The Hit@10 metric measures how often the correct answer is within the top 10 predictions. The table compares the original model’s performance to a model using only the identified knowledge circuit, and also shows the performance of a random circuit for comparison. The Dval column indicates whether the model successfully predicted the correct answer when constructing the circuit (1.0 means it did). Different types of knowledge (Linguistic, Commonsense, Factual, Bias) are evaluated and the number of edges in each circuit is also provided.

In-depth insights#

Knowledge Circuits#

The concept of “Knowledge Circuits” presents a novel framework for understanding how knowledge is represented and utilized within large language models (LLMs). Instead of viewing knowledge as isolated components (like individual neurons or attention heads), this approach emphasizes the interconnectedness of various neural components (attention heads, MLPs, embeddings) that collaboratively contribute to specific knowledge articulation. Knowledge Circuits are identified as subgraphs within the model’s computational graph, revealing how information flows and transforms across layers to generate a response. This perspective offers a more holistic and nuanced understanding of LLMs by unveiling implicit neural knowledge representations and providing insights into how knowledge editing techniques impact the model’s internal mechanisms. Analyzing these circuits allows researchers to better interpret LLM behaviors such as hallucinations and in-context learning, offering a pathway toward improving model design and enhancing the safety and reliability of these powerful systems. The approach is data-driven and validated through empirical studies, highlighting the practical implications of the Knowledge Circuits framework. This innovative methodology represents a significant step forward in understanding LLMs and paving the way for more advanced and reliable knowledge editing and LLM design.

Circuit Discovery#

Circuit discovery in neural networks, a crucial aspect of mechanistic interpretability, involves identifying subgraphs responsible for specific functionalities. This process often employs ablation techniques—systematically removing edges or nodes to measure the impact on model performance. Critical components, whose removal significantly degrades performance, are considered part of the circuit. The challenge lies in efficiently navigating the vast complexity of the network’s computational graph to isolate these crucial subgraphs. Automated methods, often leveraging sophisticated algorithms, have emerged to streamline the process, but their computational cost and interpretability remain areas of active research. Circuit identification enables a deeper understanding of neural processes by highlighting the collaborative interactions of different components within the model, paving the way for improved model design, targeted interventions such as knowledge editing, and the development of more robust and explainable AI systems.

Editing Mechanisms#

Effective knowledge editing in large language models (LLMs) necessitates a profound understanding of their internal knowledge representations. Current methods, such as those targeting Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) or attention mechanisms, often exhibit limitations. A deeper investigation into the collaborative interplay between different model components (e.g., attention heads, MLPs, embeddings) is crucial. This holistic perspective can lead to improved editing techniques that address the issues of poor generalization and unwanted side effects. The concept of ‘knowledge circuits,’ which represent subgraphs of the model’s computation graph responsible for specific knowledge articulation, is a promising avenue for enhancing editing precision. Analyzing the flow of information within these circuits, including the roles of specialized components like mover heads and relation heads, can unveil crucial insights into the internal mechanisms of knowledge storage and modification. This approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of how editing interventions affect the overall model behavior, facilitating the development of more effective and targeted editing strategies. Future research should focus on developing methods that leverage the knowledge circuit framework to improve the accuracy and controllability of LLM editing processes. This includes exploring how editing impacts different aspects of these circuits and developing more robust editing methods that account for their complex internal dynamics.

Model Behaviors#

Analyzing model behaviors in large language models (LLMs) is crucial for understanding their capabilities and limitations. Hallucinations, where models generate factually incorrect information, are a significant area of concern, demanding investigation into their root causes and potential mitigation strategies. In-context learning, the ability of LLMs to adapt to new tasks based on provided examples, reveals the model’s capacity for dynamic adjustment and generalization. However, understanding how and why this learning occurs, particularly at the circuit level, remains key. Another important behavior is the model’s handling of reverse relations. If a model successfully predicts a fact, does it also exhibit the same proficiency when the relation is reversed? A comprehensive analysis of these behaviors necessitates exploration of internal mechanisms, potentially using circuit-based analysis to pinpoint critical subgraphs involved in knowledge processing and inference. Such analyses are critical for not only improving model reliability but also guiding responsible development and deployment.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this paper on knowledge circuits in large language models could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of knowledge circuit discovery is crucial, potentially leveraging advanced graph traversal techniques or incorporating novel neural network interpretability methods. A deeper investigation into the interplay between different types of attention heads (e.g., mover, relation, mix heads) and their role in knowledge representation and utilization is warranted, especially in different model architectures. This should include analysis of how different types of knowledge are encoded and how these mechanisms change during knowledge editing or fine-tuning. Furthermore, research could focus on developing more effective and robust knowledge editing techniques, addressing limitations like poor generalization and unintended side effects. This could involve a deeper understanding of how changes in the knowledge circuits impact the broader behavior of the language model. Finally, extending the study of knowledge circuits to explore more complex model behaviors, such as reasoning, commonsense understanding, and creativity, would provide valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of human-like intelligence in LLMs. Careful consideration of the ethical implications, particularly concerning bias mitigation and potential misuse of knowledge editing techniques, should also be a key focus of future work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

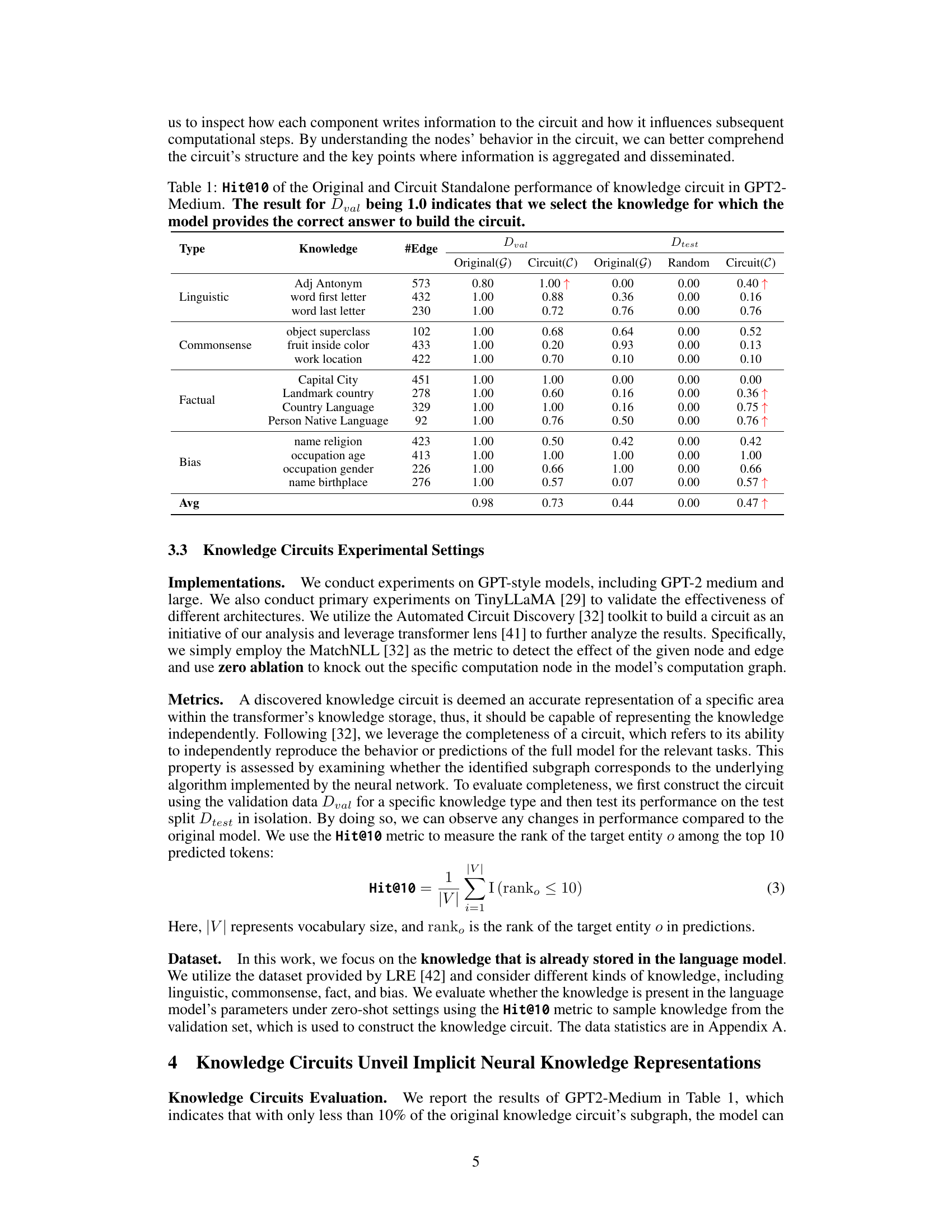

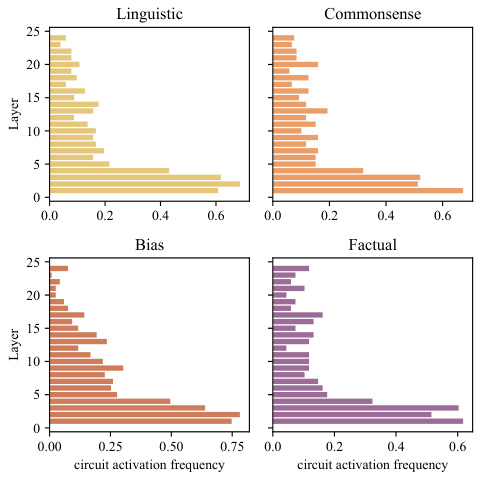

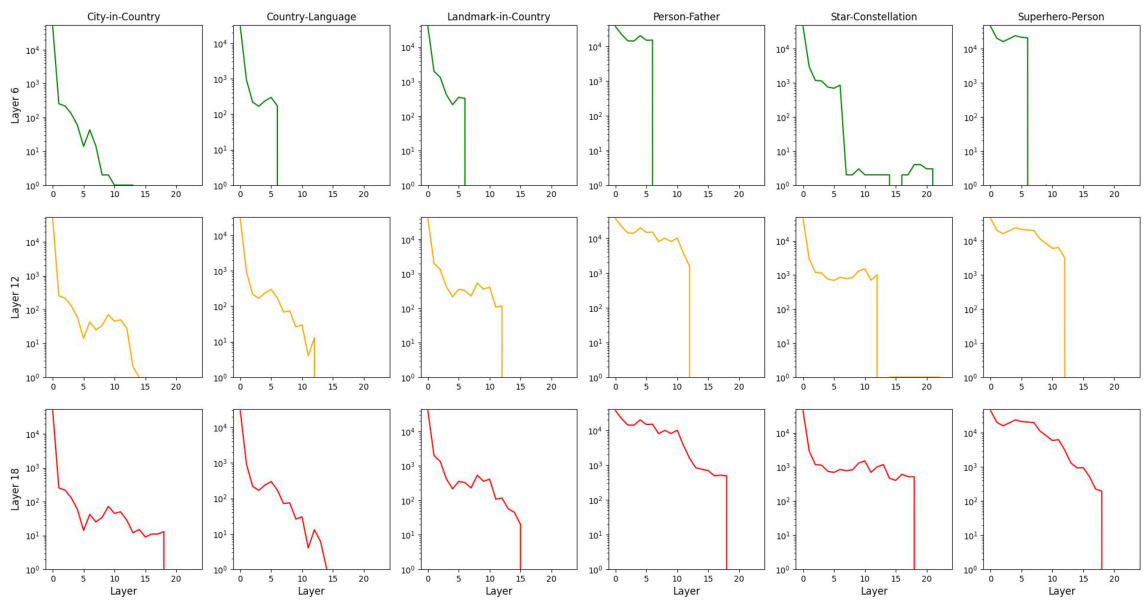

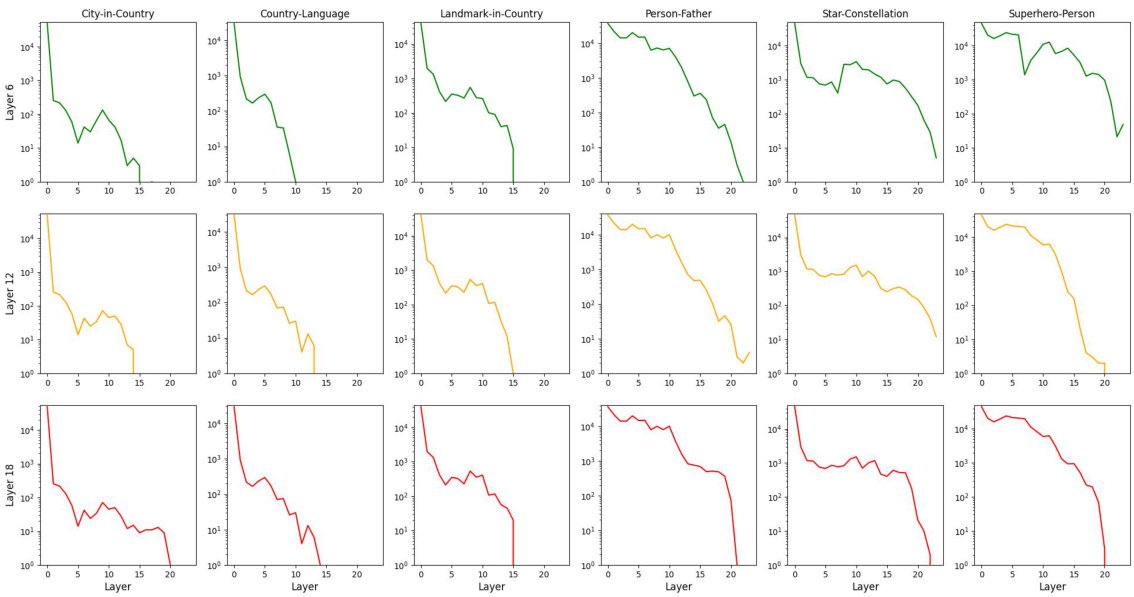

This figure shows the distribution of activated components (attention heads and MLPs) across different layers in the GPT2-Medium language model for four different knowledge types: Linguistic, Commonsense, Bias, and Factual. Each bar represents a layer, and the height of the bar indicates the average activation frequency of components within that layer for the specified knowledge type. The figure visually demonstrates the distribution of knowledge across different layers of the model, revealing that some types of knowledge might be more prevalent in lower or higher layers of the network.

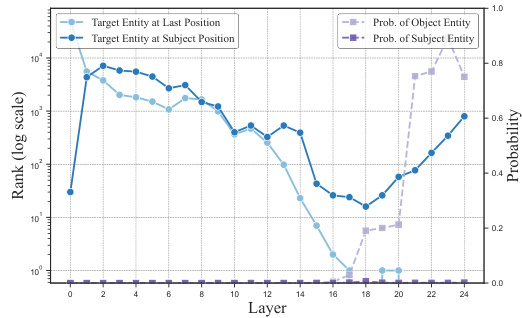

This figure shows how the probability and rank of the target entity (‘French’) change across different layers of the transformer model when processing the input sentence ‘The official language of France is’. The x-axis represents the layer number and the y-axis shows both the rank (on a log scale) and probability of the target entity. Two lines show the rank of the target entity, one at the subject position (France) and one at the final token position (last token). Two additional lines show the corresponding probabilities for the target entity at those positions. The figure illustrates how the model processes and integrates information across layers, eventually culminating in the high probability of the correct answer at the final token position.

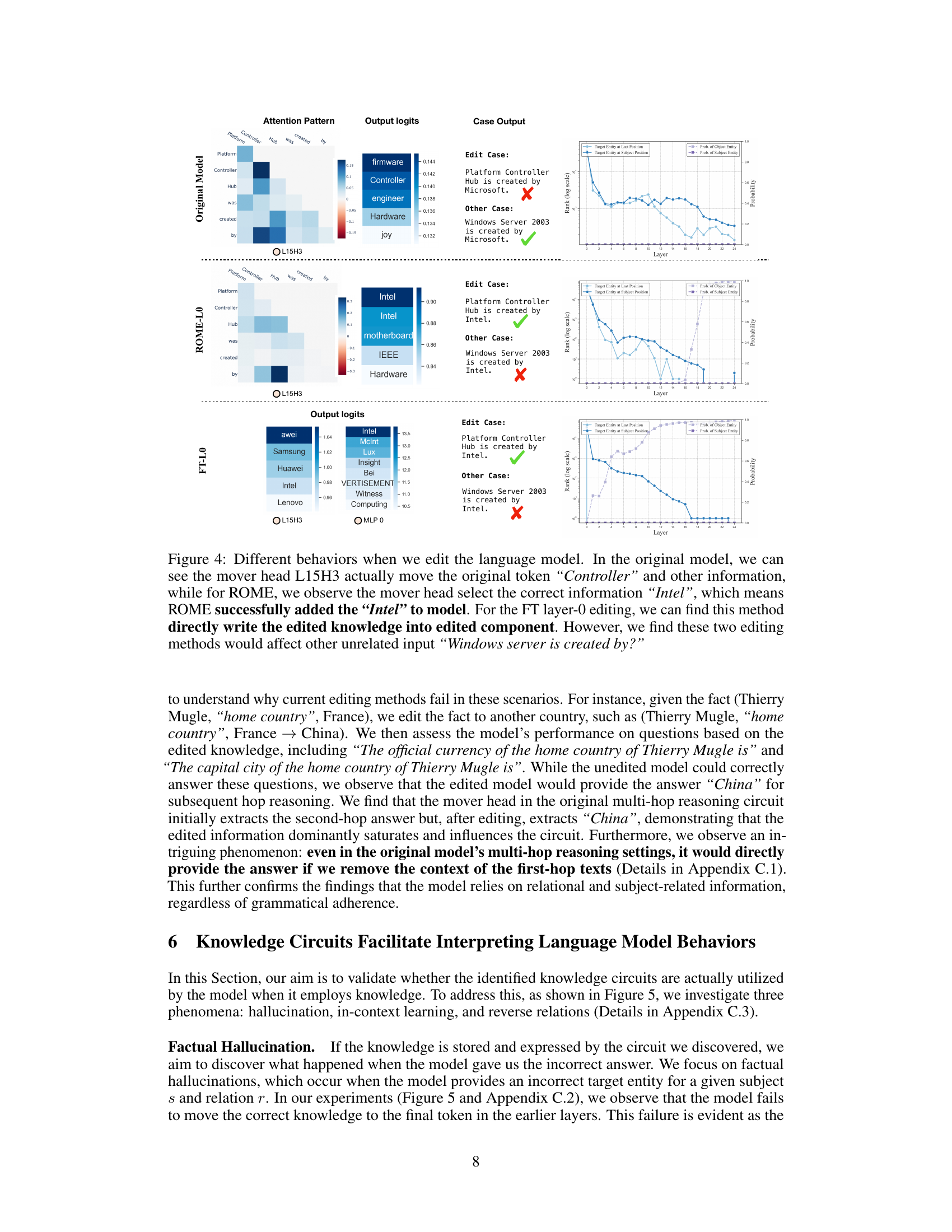

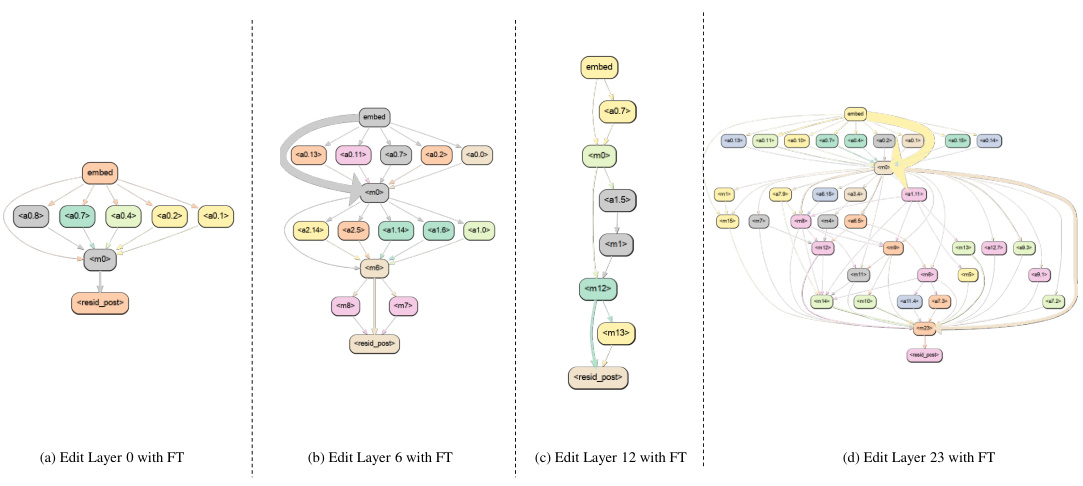

This figure compares the behavior of three different knowledge editing methods (original model, ROME, and FT-M) on the same language model. It shows how each method handles the insertion of new knowledge (in this case, changing the creator of “Platform Controller Hub”) and the impact it has on the model’s response to related and unrelated questions. The original model shows a lack of modification for the new fact, leading to incorrect answers when probing for new knowledge. ROME shows the edited information correctly integrated into the model’s reasoning chain, which leads to the correct answer for related questions but produces a false positive for an unrelated fact. Lastly, FT-M illustrates the direct injection of new knowledge into the model, causing overfitting and resulting in correct answers for both related and unrelated questions.

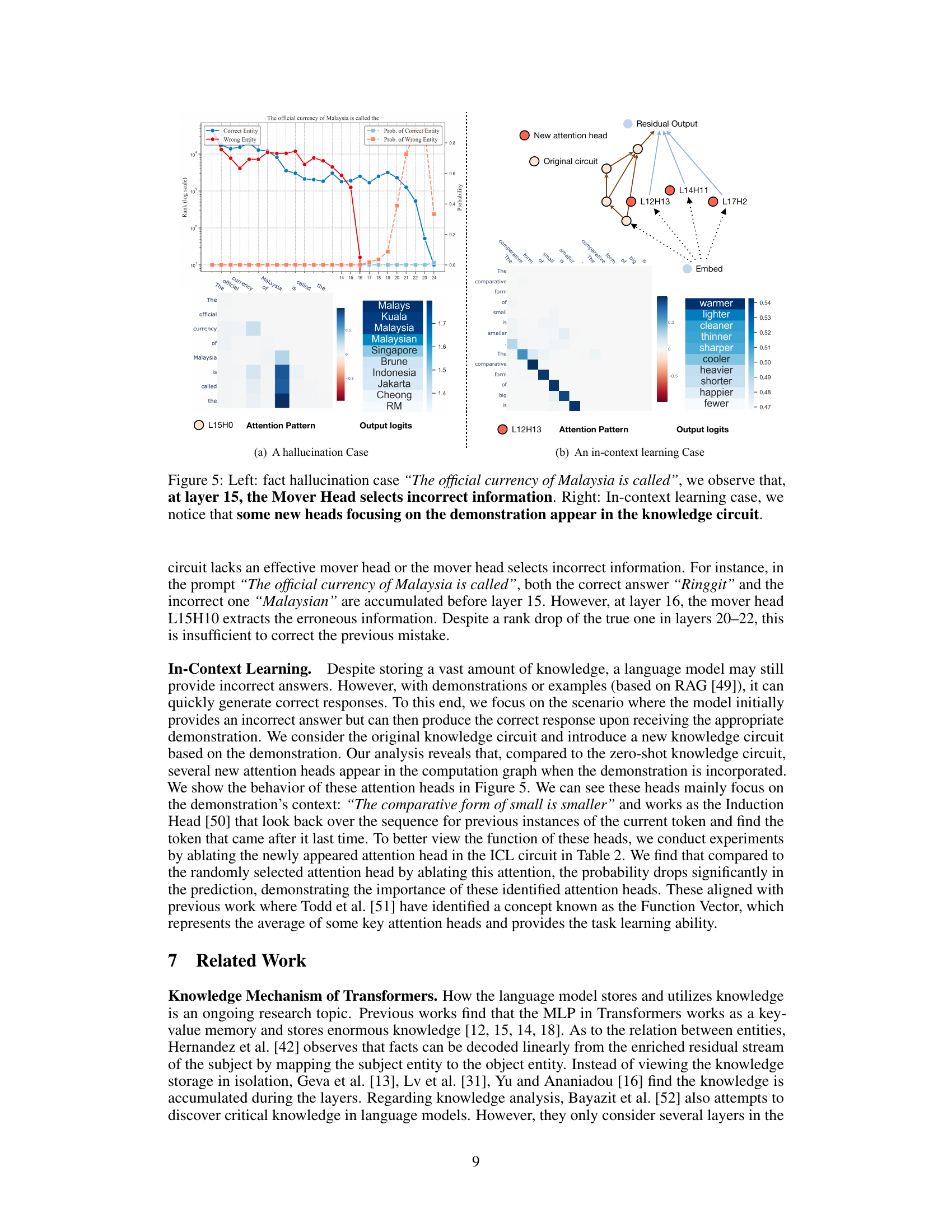

This figure shows two cases from the paper. The left panel shows a hallucination where the model incorrectly identifies the currency of Malaysia. The knowledge circuit analysis reveals that at layer 15, a mover head selects incorrect information. The right panel shows in-context learning, where the model initially produces an incorrect answer but corrects it after seeing a demonstration. The analysis of the knowledge circuit reveals several new attention heads appear in the computation graph when the demonstration is incorporated, focusing on its context.

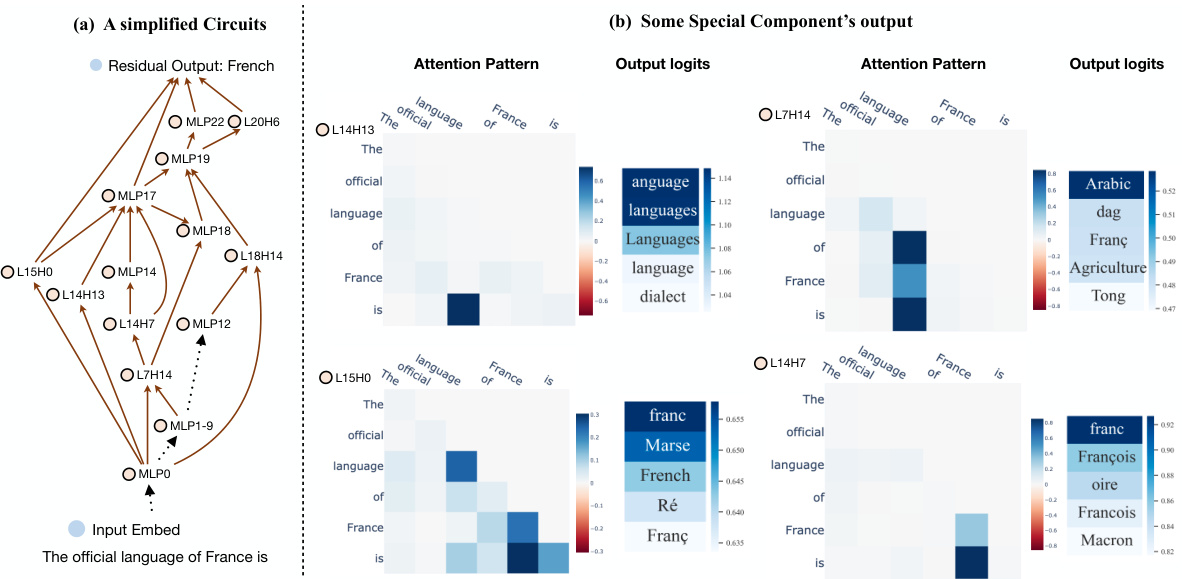

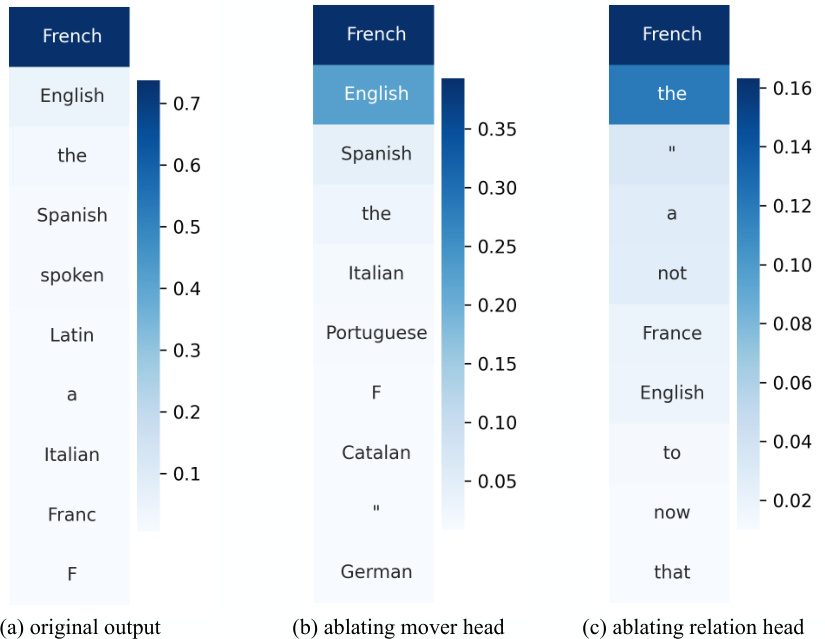

This figure shows the top 10 token output probabilities for three different scenarios: (a) original output, (b) ablating mover head, and (c) ablating relation head. By comparing the probabilities across these scenarios, we can see how removing specific components of the language model (the mover head and the relation head) impacts its predictions and how these components affect information transfer and generation of meaningful vs. meaningless tokens. Specifically, removing the mover head increases probabilities of words not closely related to the subject, and removing the relation head increases probabilities of unrelated or meaningless words.

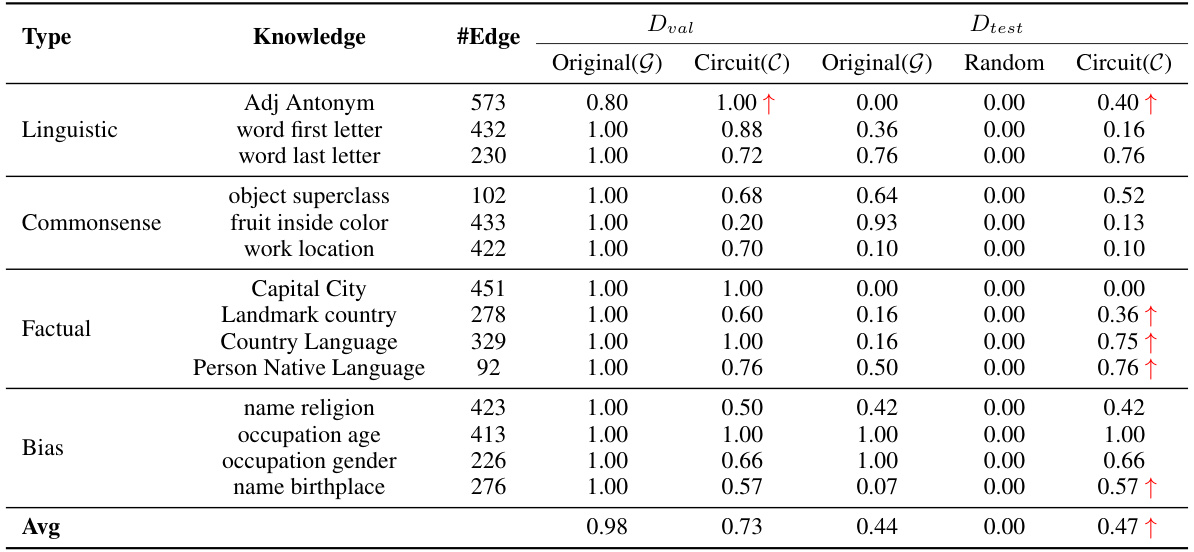

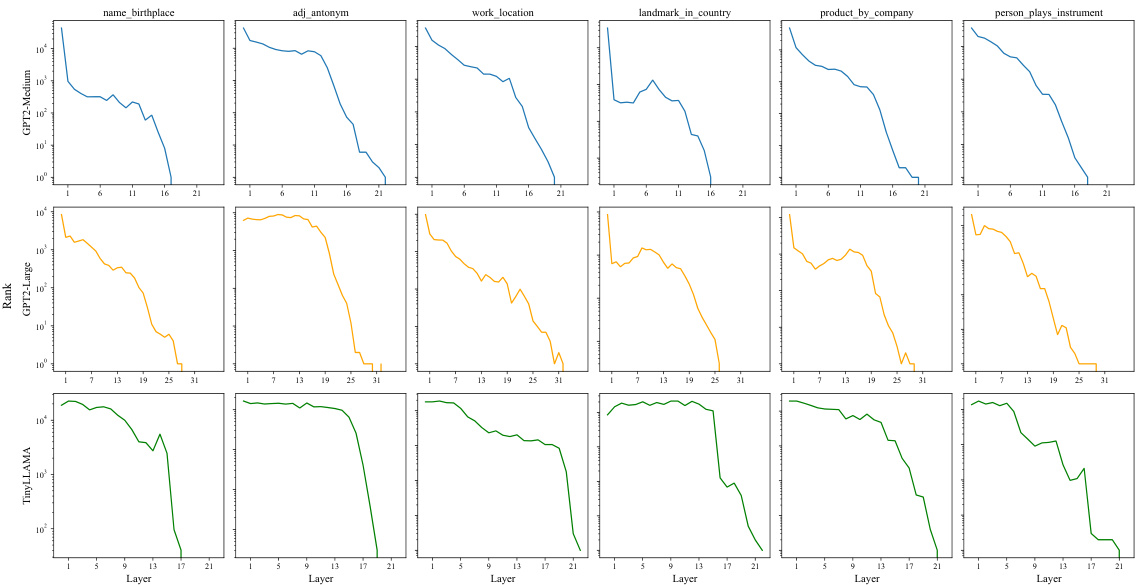

This figure shows the average rank of the target entity across different layers for three different language models: GPT2-Medium, GPT2-Large, and TinyLLAMA. The rank is calculated by mapping the model’s output at each layer to the vocabulary space. The results show that for GPT2-Medium and GPT2-Large, the target entity tends to achieve a higher rank in the middle and later layers. This suggests that the model progressively aggregates information related to the target entity as it processes through the layers. In contrast, TinyLLAMA shows a more concentrated pattern where the target entity appears closer to the final layers. This difference in behavior might be attributed to the varying architectural differences and knowledge capacity among the models.

This figure shows a knowledge circuit extracted from a GPT2-medium language model when processing the sentence ‘The official language of France is French.’ The left panel displays a simplified version of the circuit, showing the connections between key components (attention heads, Multilayer Perceptrons, and embeddings). The full circuit is available in Figure 9 of the Appendix. Arrows indicate the flow of information, highlighting how different components collaborate to process and represent the knowledge. The right panel shows the detailed behavior of specific components within the circuit. The matrices represent the attention patterns of different attention heads, illustrating where each head focuses its attention within the input sentence. The heatmaps visualize the output logits of each head, showing its contribution to the final prediction of each word (after mapping the logits to the vocabulary).

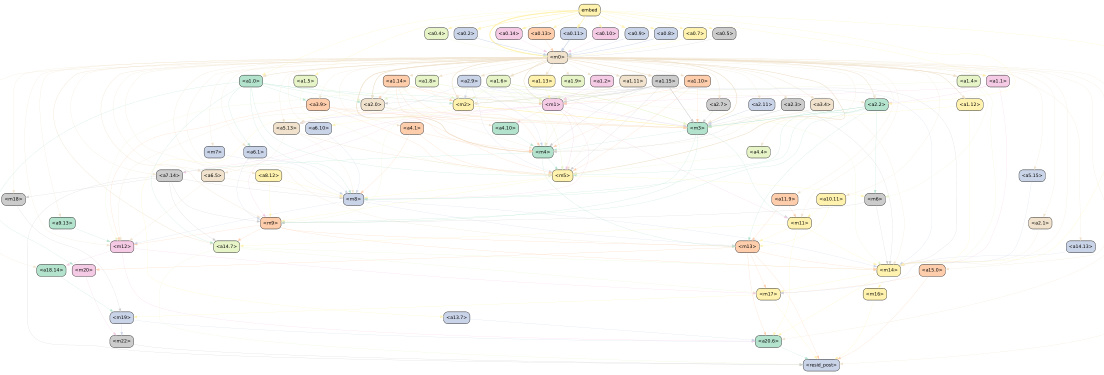

This figure shows a detailed knowledge circuit derived from the sentence ‘The official language of France is French’ within the GPT2-Medium model. The circuit visually represents the network of interactions between various components of the transformer architecture, such as attention heads and MLP layers, that collectively contribute to the model’s ability to generate the correct response. The nodes represent different components in the network, and the edges represent the connections between these components. By analyzing the structure of the circuit, researchers can gain insights into the model’s internal workings, enabling a better understanding of how knowledge is represented and used by the model. The figure helps illustrate the flow of information through the model as it processes and generates the target output.

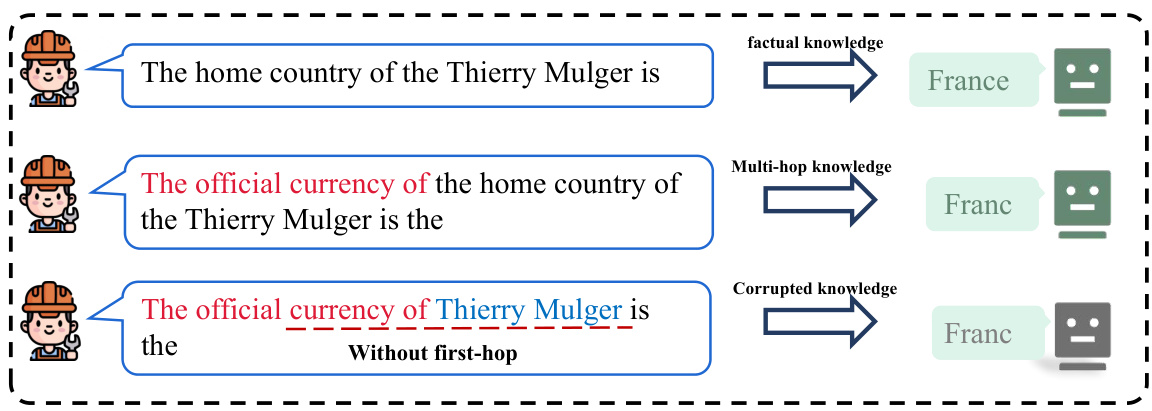

This figure demonstrates a case where a language model successfully answers a multi-hop question even when the context of the first hop is removed. The model’s ability to answer correctly without the first hop suggests an alternative reasoning mechanism beyond simply combining information from sequential hops. The phenomenon is observed in both GPT-2 and TinyLLAMA models.

This figure shows a knowledge circuit extracted from the GPT2-Medium model for the sentence ‘The official language of France is French’. The left panel displays a simplified version of the circuit (the full circuit is shown in Figure 9 in the Appendix), which visualizes the connections between different components of the model such as attention heads and MLP layers. Arrows (–>) represent connections between nodes where some steps might be skipped for simplification. The right panel displays the behavior of specific components including attention patterns and output logits for several attention heads. The attention pattern matrices show how much attention each head pays to each word in the input sentence, while the heatmaps illustrate the model’s output logits (probabilities) for different words in the vocabulary after each head’s processing.

This figure shows an example of a knowledge circuit extracted from the GPT-2 Medium language model for the sentence ‘The official language of France is French.’ The left panel displays a simplified version of the circuit, showing the flow of information through various components of the transformer architecture (attention heads and MLP layers). The arrows illustrate the connections and information flow. The full circuit is available in Figure 9 of the Appendix. The right panel displays the behavior of some key attention heads. The leftmost heatmap represents the attention weights assigned by each head, showing which parts of the input sentence each head focuses on. The rightmost heatmap illustrates the output logits of the attention head, mapping these values to words in the model’s vocabulary.

This figure visualizes the changes in the ranking of the target new token’s probability across different layers when editing the model using FT-M for different knowledge types. It shows the effect of applying the FT-M method for knowledge editing at different layers of the model. The vertical lines indicate that FT-M directly embeds the editing information into the model’s information flow, while the peaks a few layers after the edited layer illustrate ROME’s more gradual effect.

More on tables

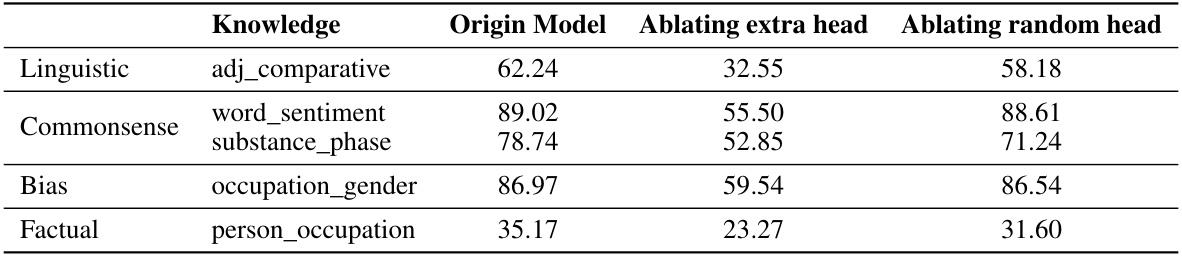

This table shows the performance change (Hit@10) when ablating the newly appeared attention heads in the In-Context Learning (ICL) circuit and when ablating random attention heads. The results are broken down by knowledge type (Linguistic, Commonsense, Bias, Factual) and specific knowledge sub-type (e.g., adj_comparative, word_sentiment). It demonstrates the importance of the newly emerged attention heads in ICL by comparing their ablation impact to that of ablating random heads. A significant drop in performance is observed when ablating the ICL attention heads, especially for certain knowledge types, indicating their crucial role in the ICL process.

This table presents the Hit@10 scores, comparing the original GPT2-Medium model’s performance with that of its isolated knowledge circuits. The Hit@10 metric indicates the percentage of times the correct answer was among the top 10 predictions. A score of 1.0 means the model always produced the correct answer within the top 10 predictions for the given knowledge. The table shows performance on different knowledge types (Linguistic, Commonsense, Factual, Bias) across original and circuit-only setups, highlighting the knowledge circuit’s ability to maintain performance despite its smaller size.

This table presents the performance of knowledge circuits in GPT-2-Medium model. It compares the original model’s performance (Original(G)) against the performance when only the identified knowledge circuit (Circuit(C)) is used. It also includes a comparison with a random circuit of the same size to demonstrate the significance of the discovered circuits. The ‘Hit@10’ metric indicates the percentage of times the correct answer is among the top 10 predictions made by the model. The table is categorized by knowledge type (Linguistic, Commonsense, Factual, Bias), and each knowledge type has several specific knowledge examples. Dval represents the validation set where circuits are constructed. Dtest is the test set, where the circuits are evaluated.

This table presents the Hit@10 scores for different hop reasoning scenarios. The Hit@10 metric measures the proportion of times the correct entity is ranked among the top 10 predictions. The table compares the performance of single-hop reasoning, two-hop reasoning, and integrated reasoning, which combines information from both single and two-hop scenarios. Each reasoning type’s performance is evaluated for both nodes and edges in the model’s circuit.

This table presents the performance of knowledge circuits in GPT-2-Medium. It shows the Hit@10 score (the percentage of times the correct answer is within the top 10 predictions) for both the original model and a standalone circuit model. The ‘Dval’ column indicates whether the original model correctly predicted the knowledge in the validation set. A score of 1.0 in this column signifies that only knowledge which the model originally got correct was used to create the circuit, and then the circuit’s performance is tested on unseen data. Different types of knowledge are included (linguistic, commonsense, factual, and bias) to evaluate the generalizability of the circuits.

Full paper#