↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Offline Reinforcement Learning (RL) often uses Transformer-based trajectory optimization, but these are computationally expensive and don’t scale well. This paper investigates using Mamba, a more efficient linear-time sequence model, in trajectory optimization. Existing methods face challenges with substantial parameter size and limited scalability, particularly critical in resource-constrained scenarios.

The paper introduces Decision Mamba (DeMa), which uses a transformer-like architecture. Extensive experiments show DeMa outperforms existing methods like Decision Transformer (DT), achieving higher accuracy with significantly fewer parameters in both Atari and MuJoCo environments. This demonstrates DeMa’s compatibility with trajectory optimization and its potential to improve the efficiency and scalability of offline RL systems. The hidden attention mechanism in DeMa is highlighted as a critical component.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in offline reinforcement learning as it explores the compatibility of a novel linear-time sequence model, Mamba, with trajectory optimization. It challenges the reliance on computationally expensive transformers and proposes a more efficient alternative, impacting model scalability and resource usage. The findings provide valuable insights into efficient model design and open new avenues for research in offline RL.

Visual Insights#

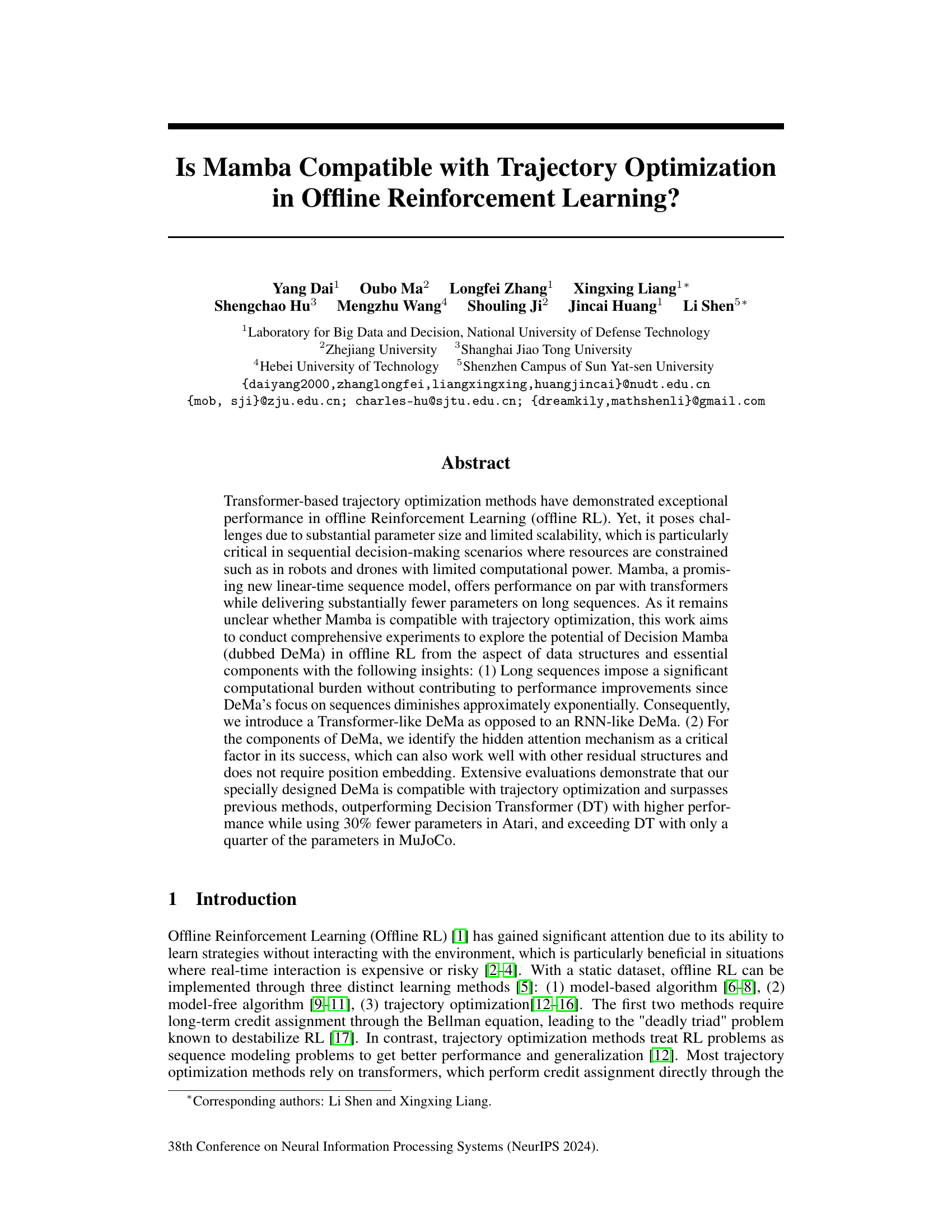

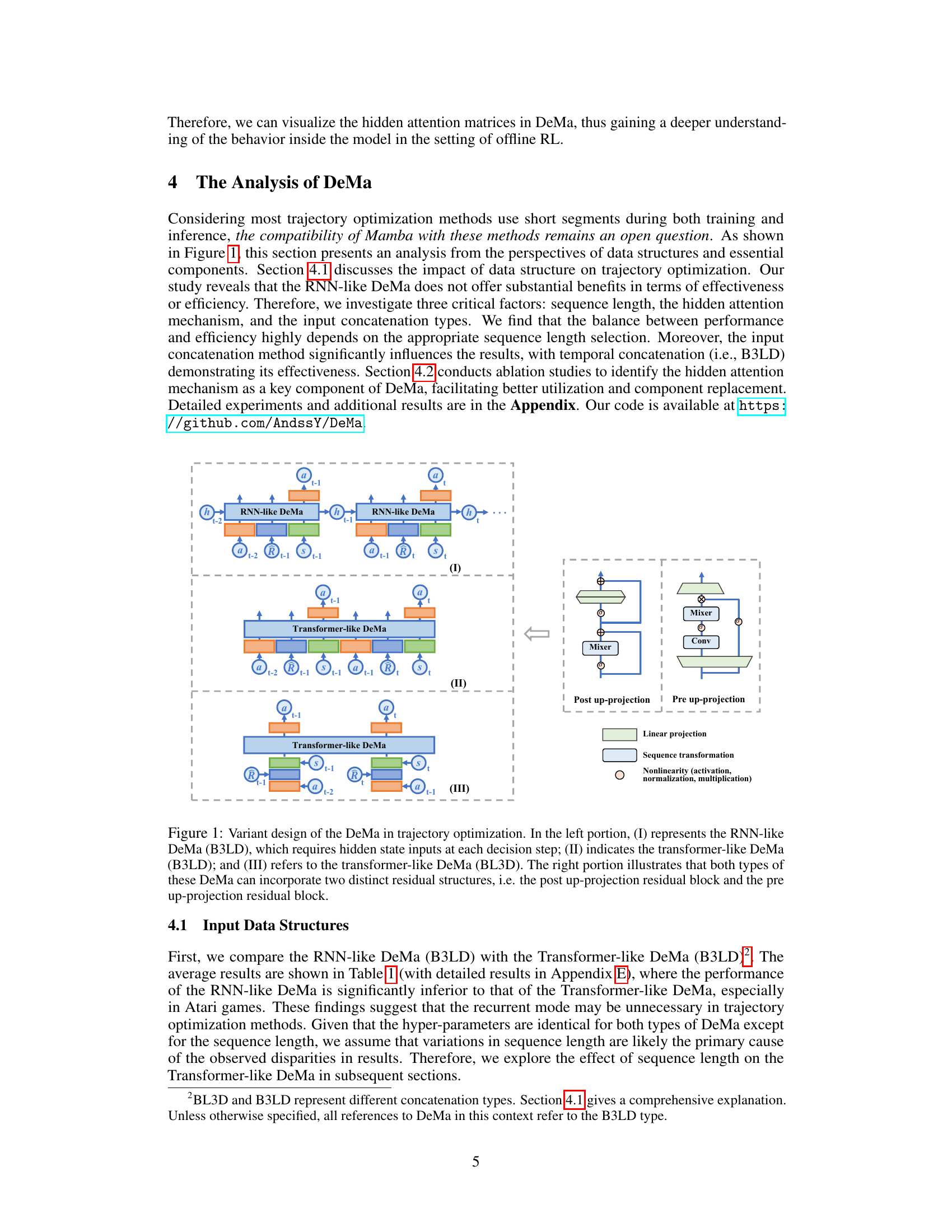

This figure shows three different variants of the Decision Mamba (DeMa) model used in trajectory optimization. The left side illustrates the RNN-like and Transformer-like versions, highlighting the differences in their input processing and data flow. The right side details the two residual structures (pre and post up-projection) that can be incorporated into either DeMa architecture. The figure also specifies the input data structure variations (B3LD and BL3D) for the different DeMa versions.

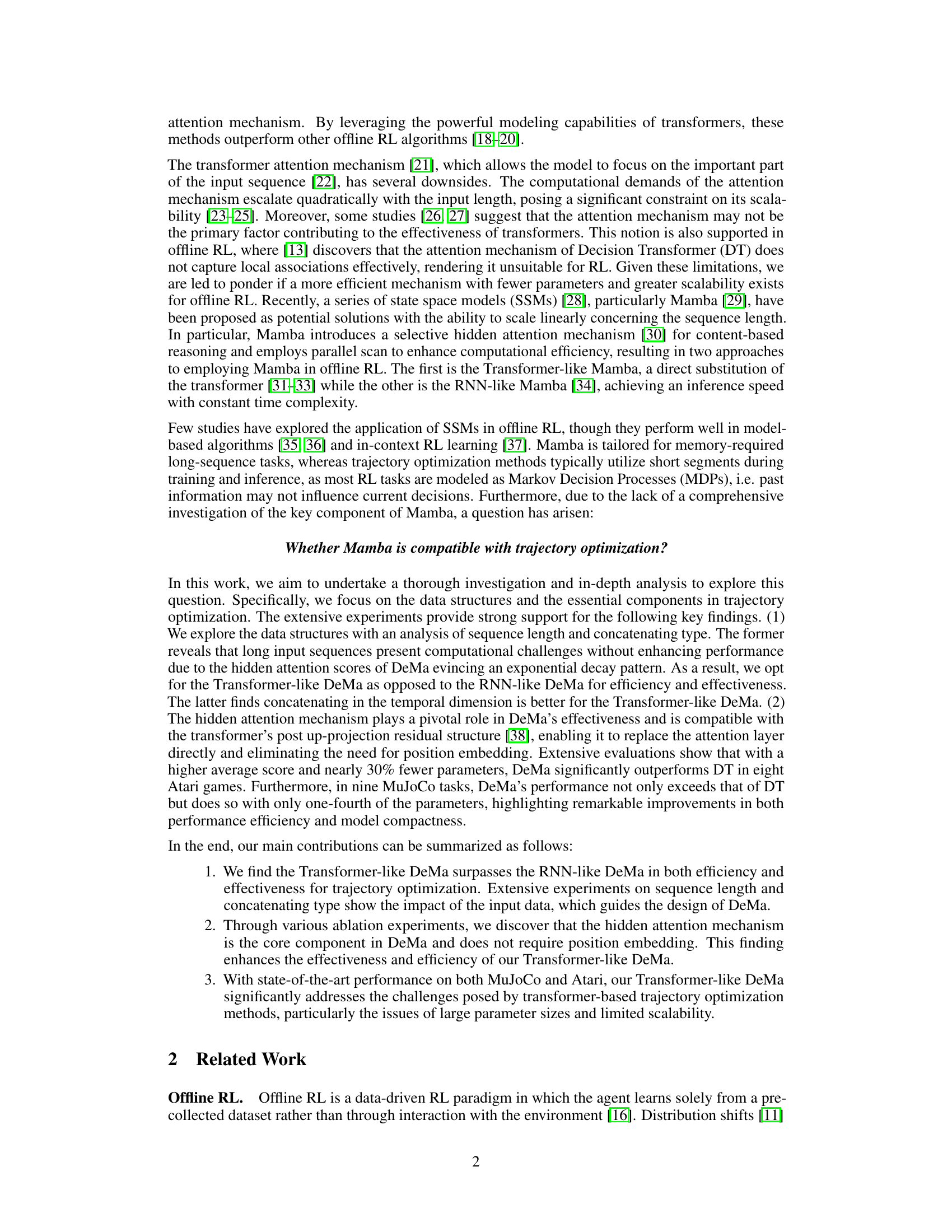

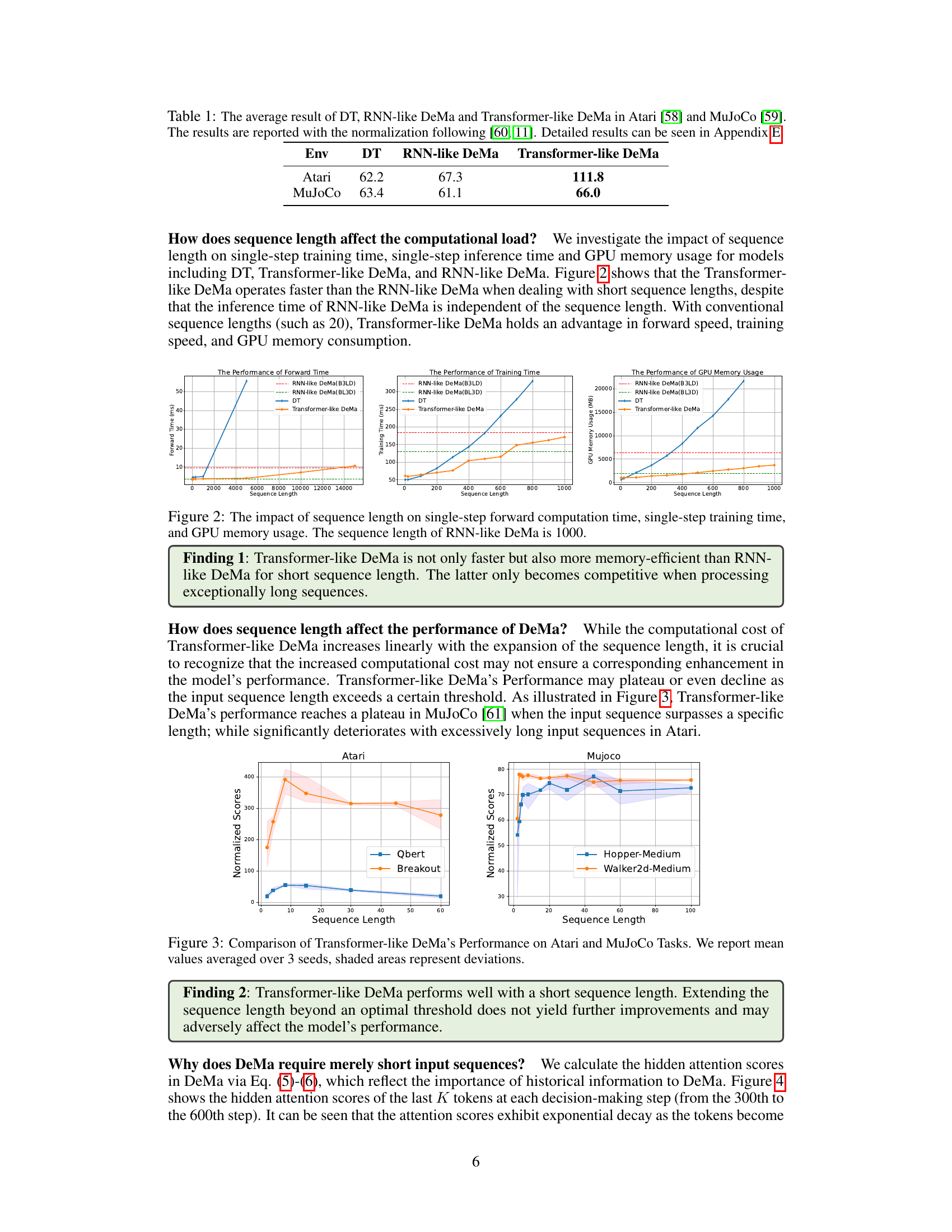

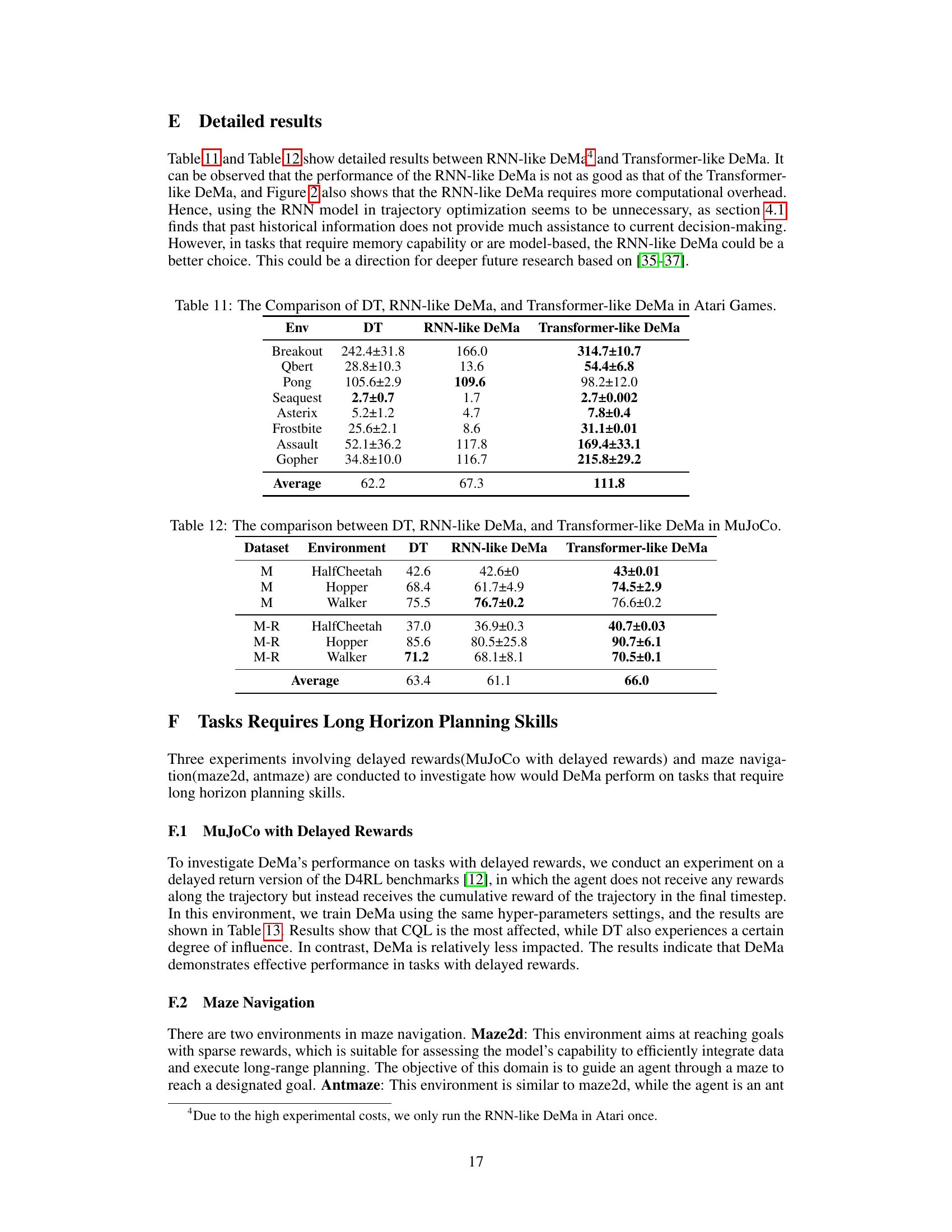

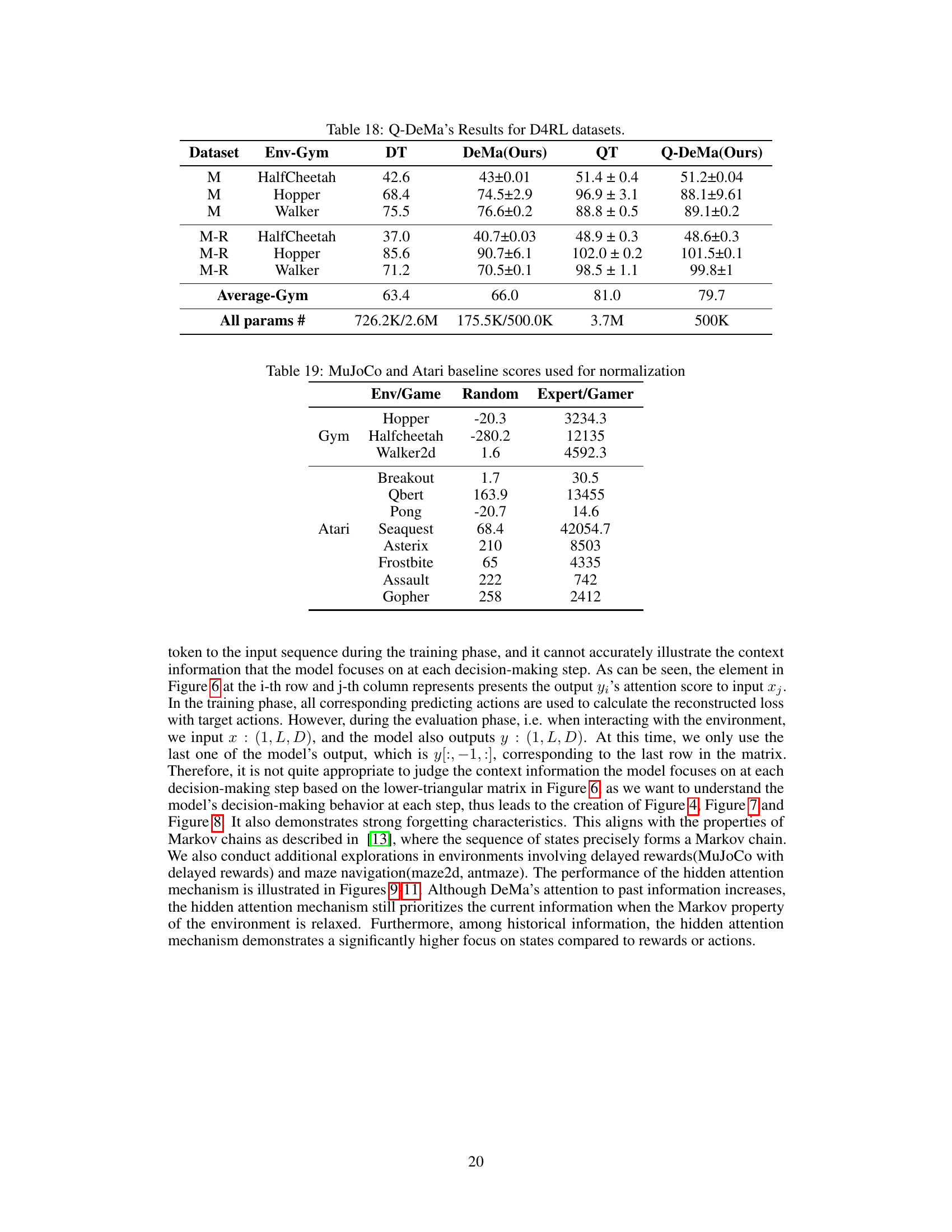

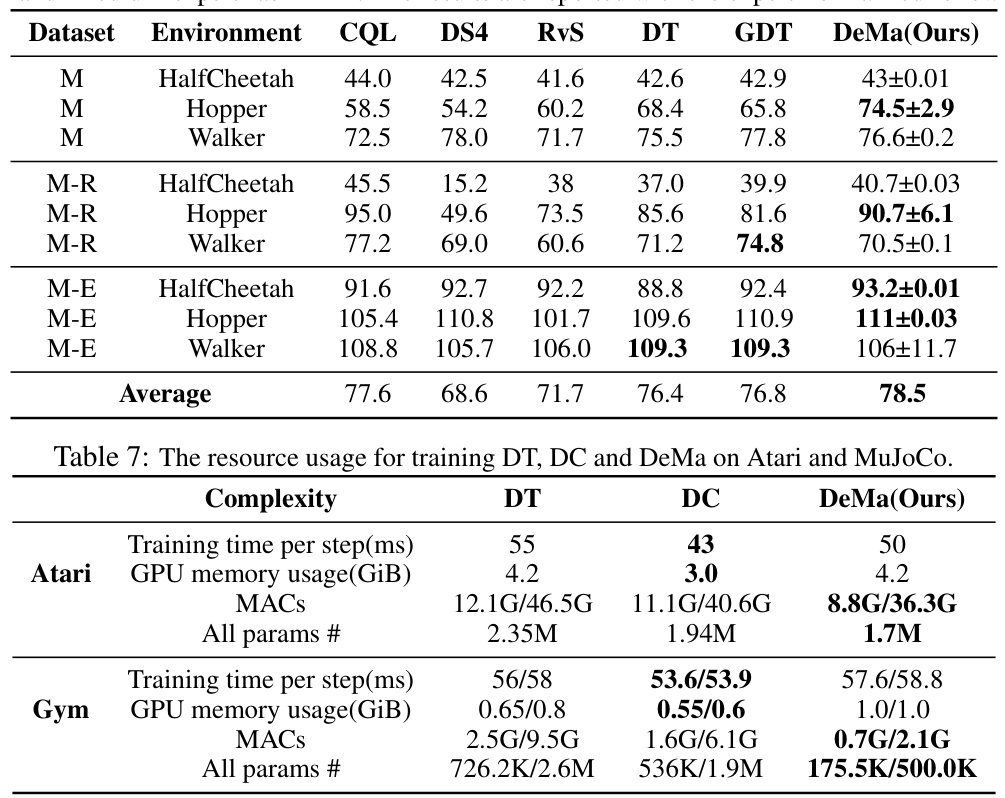

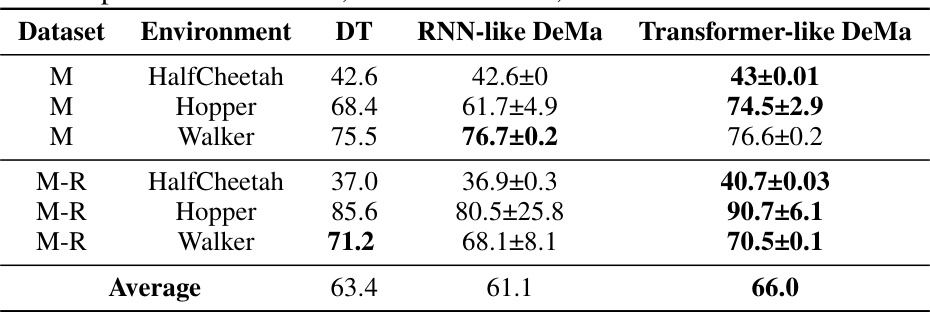

This table presents the average performance of three different models (Decision Transformer, RNN-like Decision Mamba, and Transformer-like Decision Mamba) on Atari and MuJoCo benchmark tasks. The results are normalized using methods described in references [60, 11]. More detailed results are available in Appendix E of the paper.

In-depth insights#

Offline RL’s Challenges#

Offline reinforcement learning (RL) presents unique challenges absent in online RL. Distribution shift, where the training data differs significantly from the deployment environment, is a major hurdle. Data scarcity often limits the ability to adequately cover the state-action space, leading to poor generalization. The deadly triad problem, involving bootstrapping from estimates in off-policy scenarios, adds complexity. Furthermore, evaluating performance in offline RL is difficult; standard methods like on-policy evaluation are inappropriate. Finally, reward sparsity and long-horizon dependencies complicate credit assignment and learning effective policies. Addressing these challenges effectively requires careful dataset curation, novel algorithms robust to distribution shift, and sophisticated evaluation metrics.

DeMa: Design & Tests#

A hypothetical section titled ‘DeMa: Design & Tests’ would delve into the architecture and empirical evaluation of the Decision Mamba (DeMa) model. The design aspect would detail DeMa’s core components, likely focusing on its hidden attention mechanism, its compatibility with transformer-like and RNN-like architectures, and how it addresses the computational challenges of traditional transformers. This would also encompass discussions on the selection of optimal sequence lengths and concatenation strategies (e.g., temporal vs. embedding concatenation) for input data. The tests section would meticulously describe the experimental setup, encompassing datasets (Atari, MuJoCo), evaluation metrics (e.g., normalized scores), and comparisons against state-of-the-art baselines (e.g., Decision Transformer). Ablation studies would demonstrate the impact of specific DeMa components, identifying critical factors for performance. Finally, the results would highlight DeMa’s efficiency and effectiveness in trajectory optimization, emphasizing its superior performance with fewer parameters compared to existing models. The analysis would likely include detailed tables and figures illustrating performance improvements and a discussion of the model’s strengths and limitations.

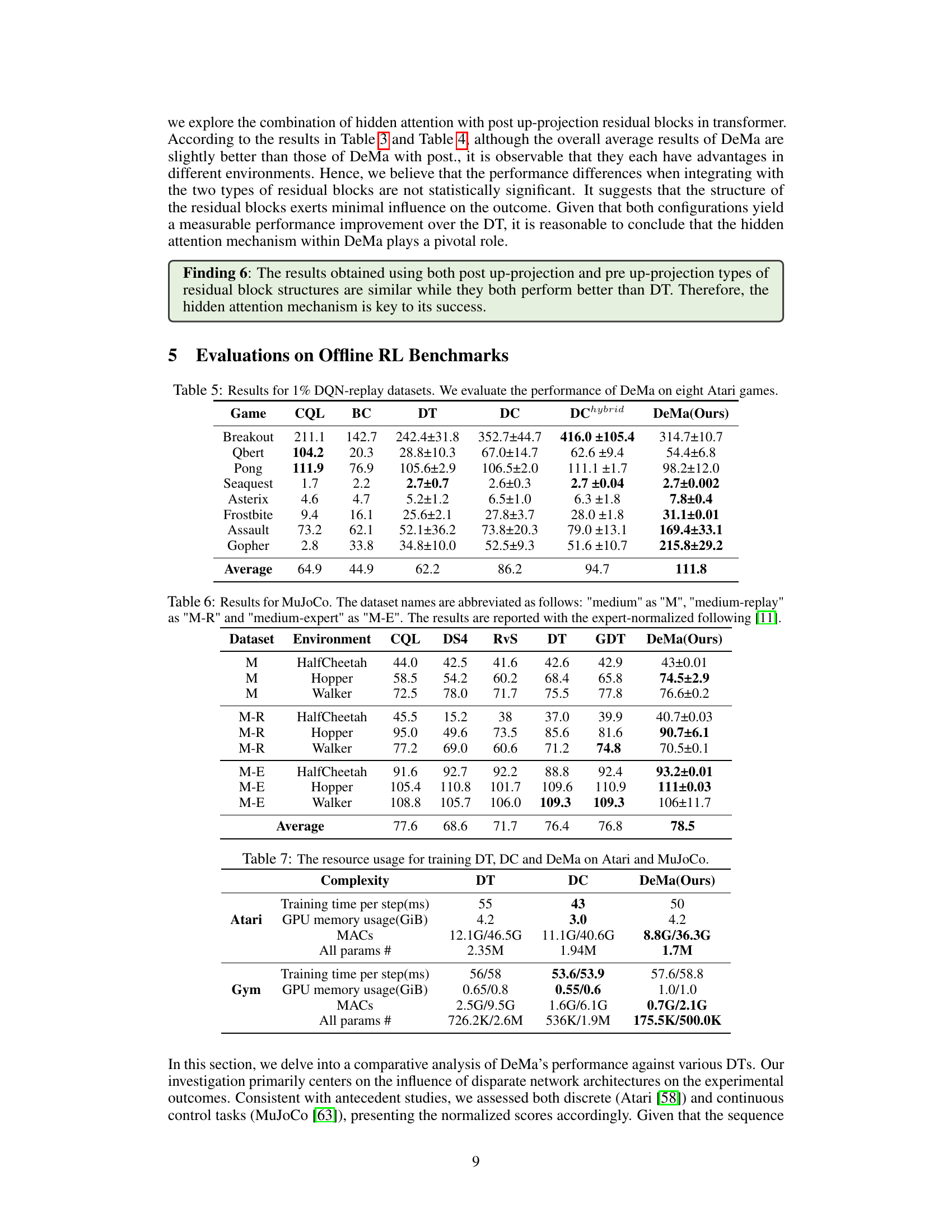

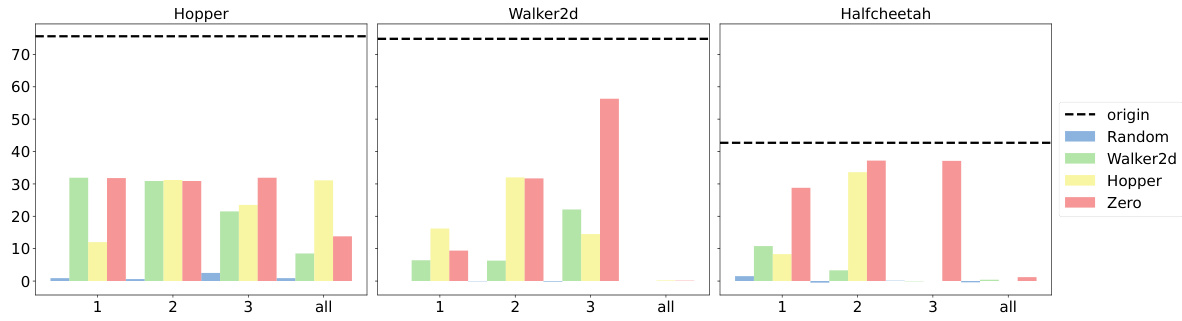

Sequence Length Impact#

Analysis of the provided research paper reveals a significant focus on understanding the effects of sequence length on model performance in offline reinforcement learning. The findings suggest a non-linear relationship, where increasing sequence length does not always translate to improved performance. In fact, beyond a certain optimal length, performance may plateau or even decrease, likely due to the computational cost of processing longer sequences and the diminishing returns of additional contextual information. This optimal length appears to be task-dependent, highlighting the importance of careful hyperparameter tuning. The study contrasts the performance of different model architectures (RNN-like and Transformer-like) in handling varying sequence lengths, revealing that Transformer-like architectures are more efficient and effective for shorter sequences, which aligns with their predominant use in trajectory optimization. The impact of sequence length is intertwined with the model’s attention mechanism, as demonstrated by the exponential decay of attention scores with increasing temporal distance from the current decision point. This suggests that focusing on longer sequences may be computationally expensive without significantly improving performance. Therefore, determining the optimal sequence length becomes crucial for balancing efficiency and effectiveness in offline RL applications.

Attention Mechanism#

The attention mechanism is a crucial component of many modern deep learning models, particularly in sequence-to-sequence tasks. It allows the model to focus on the most relevant parts of the input data, weighting different elements differently based on their importance to the current task. In the context of the provided research, the attention mechanism’s role in trajectory optimization within offline reinforcement learning is explored. The authors investigate whether a simpler, more efficient alternative to the computationally expensive standard attention mechanisms could be used without sacrificing performance. A key finding is that the ‘hidden’ attention mechanism within the proposed ‘Mamba’ model, a more efficient alternative to transformer networks, is crucial for its success. Unlike traditional transformer networks, the Mamba’s attention is shown to be particularly effective even without relying on position embeddings. The research explores how this altered design impacts trajectory optimization performance, emphasizing model efficiency and scalability compared to existing transformer-based approaches.

Future Work: DeMa#

Future work on DeMa (Decision Mamba) could explore several promising directions. Extending DeMa’s applicability to more complex RL tasks such as those involving partial observability (POMDPs) or long horizons would be valuable. Investigating the performance of DeMa on tasks demanding greater memory capacity would be essential, comparing its performance against models like LSTMs and RNNs. A deeper theoretical analysis of DeMa’s hidden attention mechanism is necessary, potentially uncovering its inherent limitations and biases. Additionally, research into the most effective ways to combine DeMa with other RL components or architectures is needed. This includes integrating DeMa with various model-based or model-free methods, to see if it can improve performance in hybrid approaches. Addressing scalability concerns remains important, especially when dealing with very long sequences or large datasets. Finally, thorough empirical evaluation across a wider range of environments and benchmarks would increase confidence in its effectiveness and provide further insights into DeMa’s capabilities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the impact of sequence length on the computational cost of different models (RNN-like DeMa, Transformer-like DeMa, and DT). It displays three subplots: forward computation time, training time, and GPU memory usage. The x-axis in each subplot represents sequence length, while the y-axis represents the corresponding metric (time in milliseconds or memory usage in MB). The results reveal that Transformer-like DeMa is faster and more memory-efficient for short sequence lengths, but the RNN-like DeMa becomes relatively more efficient only when processing exceptionally long sequences. This highlights the trade-off between performance and efficiency depending on the sequence length used.

This figure analyzes the effect of sequence length on the computational cost and performance of different models: RNN-like DeMa, Transformer-like DeMa, and DT. It shows three plots illustrating the forward computation time (ms), training time (ms), and GPU memory usage (MB) for varying sequence lengths. The results highlight that the Transformer-like DeMa outperforms the RNN-like DeMa in terms of speed and memory efficiency for shorter sequence lengths, while the RNN-like DeMa becomes more competitive with extremely long sequences.

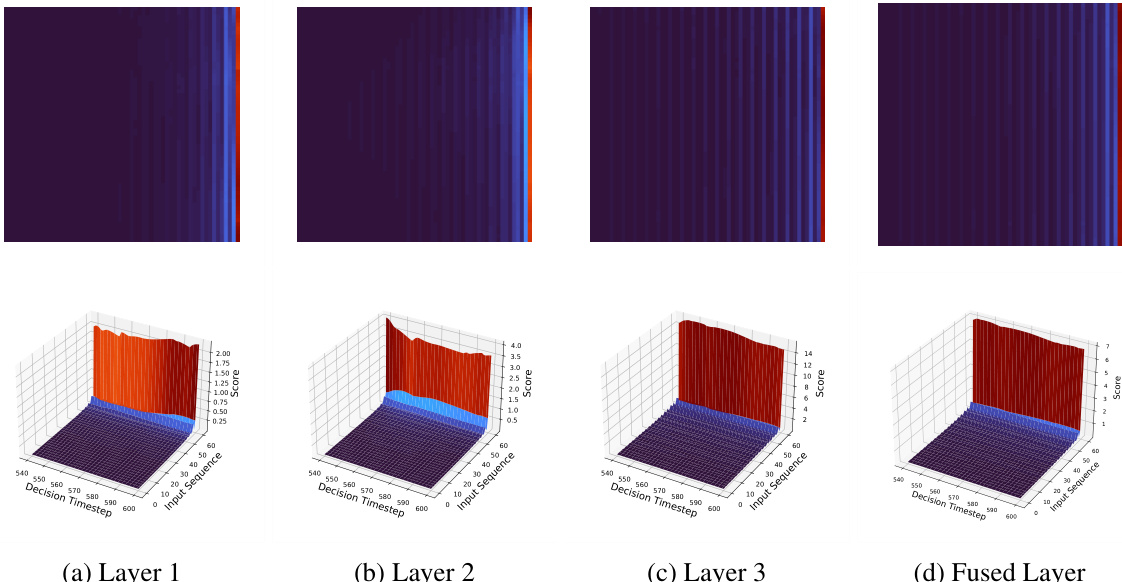

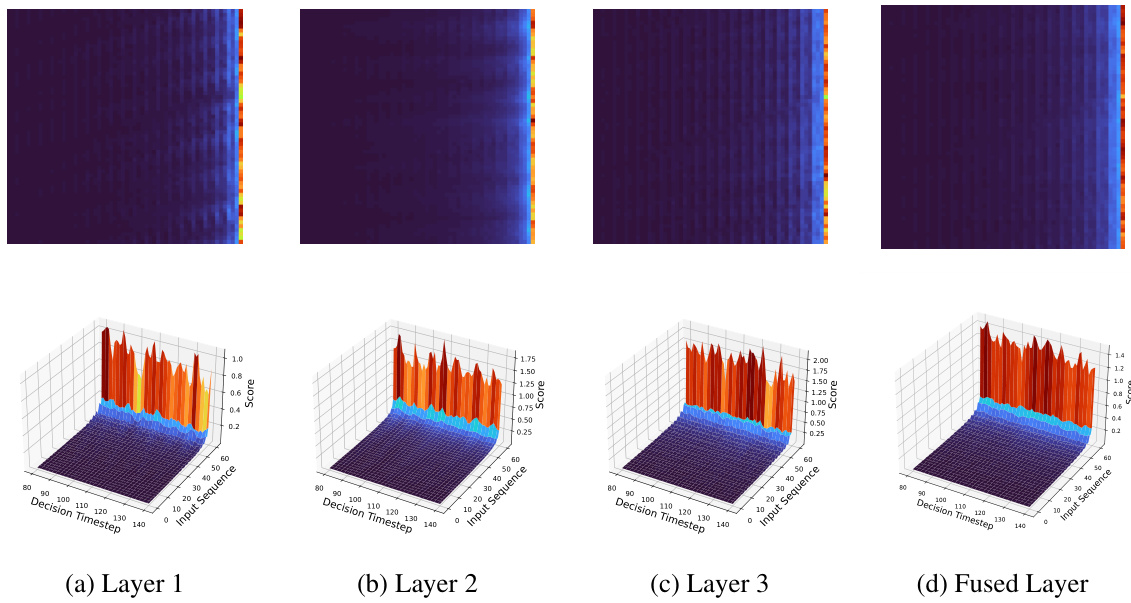

This figure visualizes the hidden attention scores of the Decision Mamba (DeMa) model over a sequence of 300 to 600 timesteps. The data used to train this model was from the Walker2d-medium dataset. The visualization is a 3D representation, showing how the attention mechanism focuses on different parts of the input sequence at each decision step. The x-axis represents the decision timestep, the y-axis represents the input sequence (past K tokens), and the z-axis represents the attention scores. The colors in the heatmap represent the magnitude of the attention scores, with warmer colors indicating stronger attention.

This figure shows three variants of the Decision Mamba (DeMa) model used in trajectory optimization. The left side shows the architectural differences between the RNN-like DeMa and the Transformer-like DeMa, highlighting the use of hidden state inputs in the RNN-like version. The right side illustrates how both types of DeMa can incorporate post and pre up-projection residual blocks. The figure clarifies the design choices made in adapting Mamba for trajectory optimization, emphasizing the selection between recurrent and transformer-like approaches and the use of different residual structures.

This figure shows three different variants of the Decision Mamba (DeMa) model used for trajectory optimization. The left side illustrates the RNN-like and Transformer-like architectures of DeMa, highlighting differences in their input processing (hidden state vs. full sequence). The right side shows that both architectures can incorporate post-projection and pre-projection residual blocks for improved performance.

This figure shows three different designs of Decision Mamba (DeMa) used in trajectory optimization. The left side illustrates the RNN-like DeMa (I) which uses hidden state inputs at every step, and two variations of the Transformer-like DeMa (II and III) which differ in how input data is concatenated. The right side shows that both RNN-like and Transformer-like DeMas can incorporate post and pre up-projection residual blocks. The figure visually represents the architectural differences in DeMa implementations.

This figure illustrates three different variants of the Decision Mamba (DeMa) model used in trajectory optimization. The left side shows the RNN-like DeMa and the Transformer-like DeMa, highlighting the difference in their input data handling (B3LD vs. BL3D). The RNN-like version requires hidden state inputs at each step, while the Transformer-like version doesn’t. The right side shows how both types of DeMa can use two different residual structures (pre- and post-projection) within their architecture.

This figure shows three different variants of the Decision Mamba (DeMa) model used in trajectory optimization. The left side illustrates the architectural differences between the RNN-like and Transformer-like versions of DeMa, highlighting the input requirements and the use of recurrent connections in the RNN-like version. The right side focuses on the residual structures incorporated within both RNN-like and Transformer-like DeMa, comparing post and pre up-projection residual blocks. These design choices affect the efficiency and effectiveness of the model for sequential decision-making tasks.

This figure shows three different variants of the Decision Mamba (DeMa) model used in trajectory optimization. The left side illustrates the RNN-like and Transformer-like versions of DeMa, highlighting the difference in how they process sequences (recursive vs. parallel). The right side shows the two residual structures that can be incorporated into either DeMa variant.

This figure illustrates three different variants of the Decision Mamba (DeMa) model used in trajectory optimization. The left side shows the architectural differences between the RNN-like and Transformer-like versions of DeMa, highlighting the use of hidden state inputs in the RNN-like model. The right side shows that both RNN-like and Transformer-like DeMa can use either a ‘post up-projection’ or ‘pre up-projection’ residual block structure. The different versions reflect different approaches to handling sequence information and residual connections in the model.

More on tables

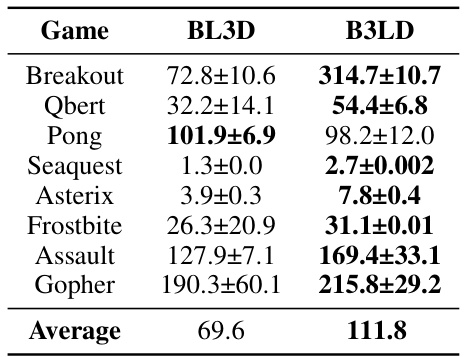

This table compares the performance of two different input concatenation methods (BL3D and B3LD) for the Transformer-like DeMa model in Atari games. BL3D concatenates the state, action, and reward along the embedding dimension, while B3LD concatenates them along the temporal dimension. The results show that B3LD generally outperforms BL3D, suggesting that temporal concatenation is more effective for trajectory optimization.

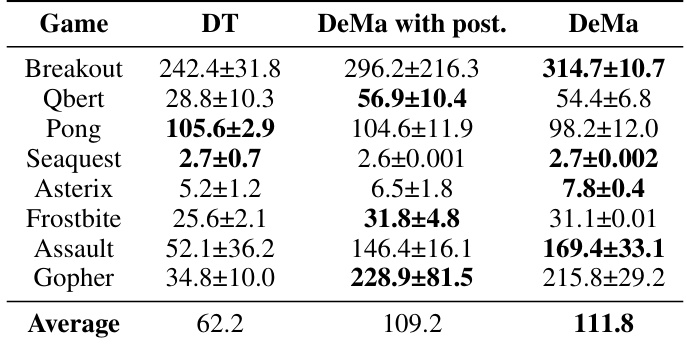

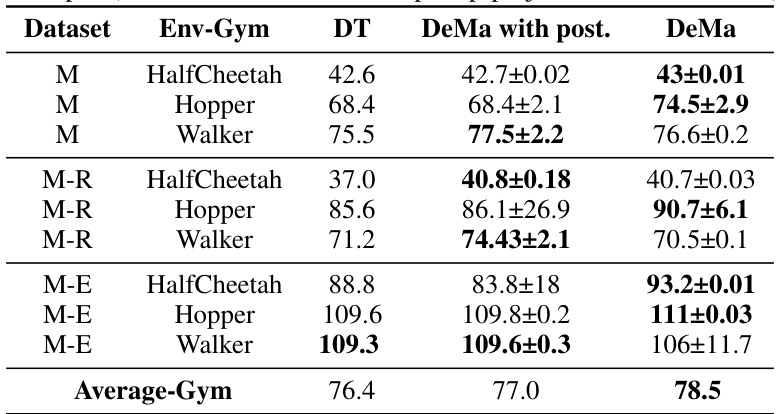

This table compares the performance of three different models in eight Atari games: Decision Transformer (DT), DeMa with a post up-projection residual block, and DeMa with a pre up-projection residual block. The results show the average normalized scores for each game, with standard deviations included. It highlights the impact of the residual block placement on DeMa’s performance compared to DT.

This table compares the performance of Decision Transformer (DT), DeMa with post-projection residual block, and DeMa with pre-projection residual block on nine MuJoCo tasks. The results show DeMa’s performance improvement in most of the environments compared to DT and the DeMa with post-projection residual block, highlighting the effectiveness of the hidden attention mechanism and pre-projection residual block structure in DeMa.

This table shows the average performance results of three different models (Decision Transformer (DT), RNN-like Decision Mamba (DeMa), and Transformer-like Decision Mamba (DeMa)) on Atari and MuJoCo benchmark tasks. The results are normalized following methods described in references [60, 11]. More detailed results are available in Appendix E of the paper.

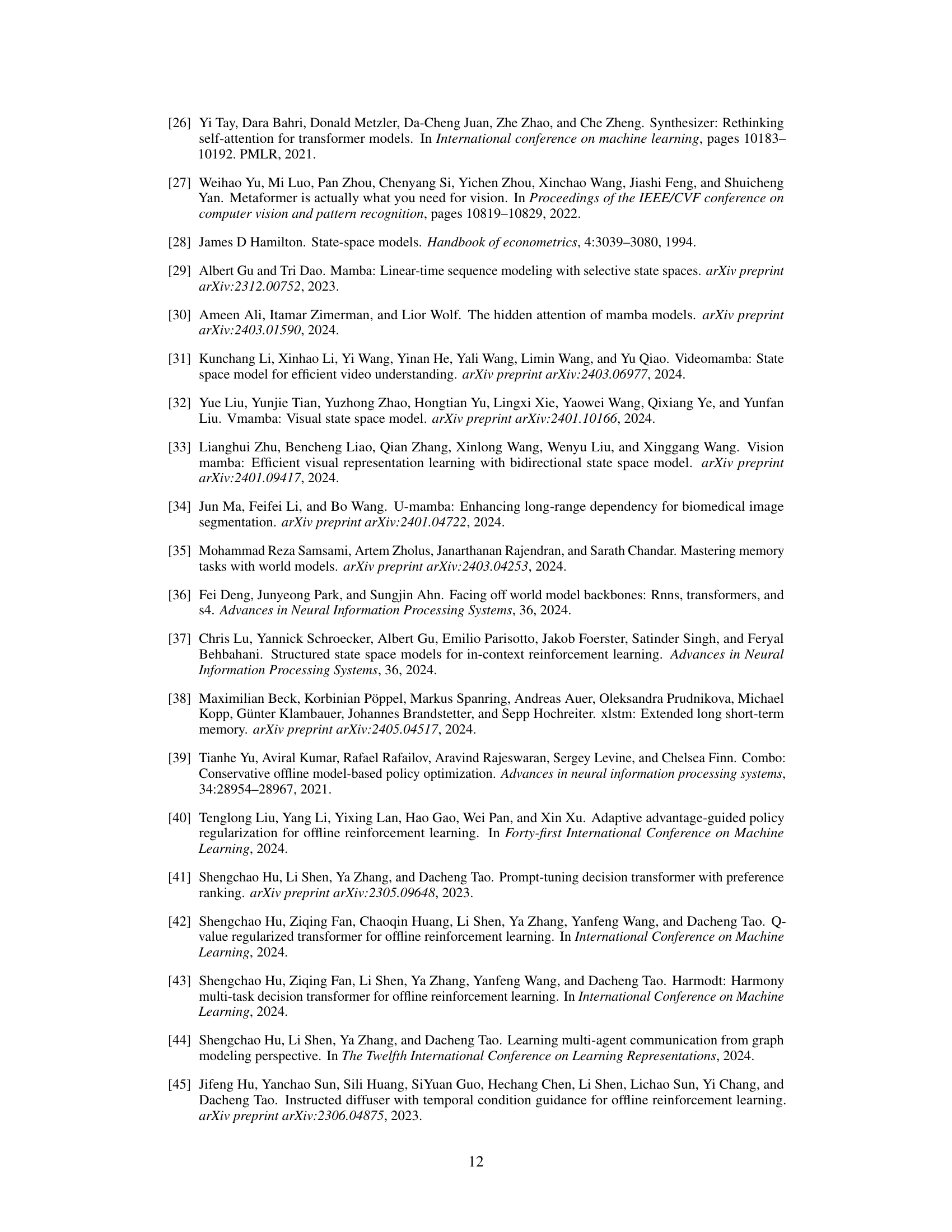

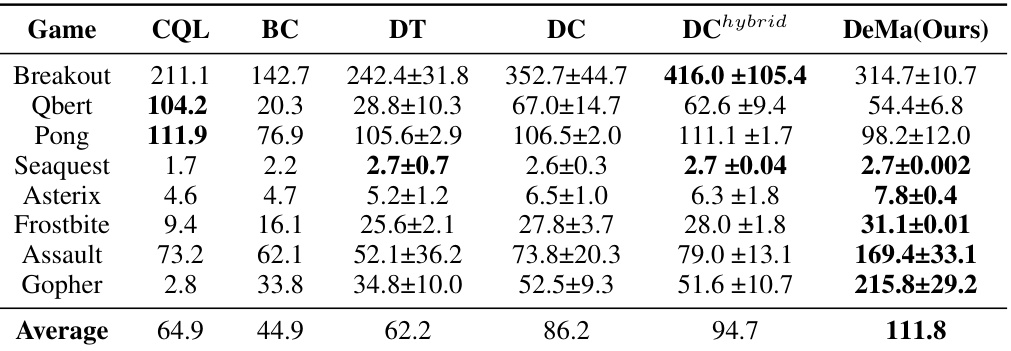

This table presents the average results of different offline reinforcement learning algorithms on eight Atari games using a 1% DQN-replay dataset. The algorithms compared include CQL, BC, Decision Transformer (DT), Decision Convformer (DC), Decision Transformer Hybrid (DChybrid), and Decision Mamba (DeMa). The table shows the average normalized scores for each algorithm on each game, providing a comparison of their performance. DeMa shows significantly improved performance over the other algorithms.

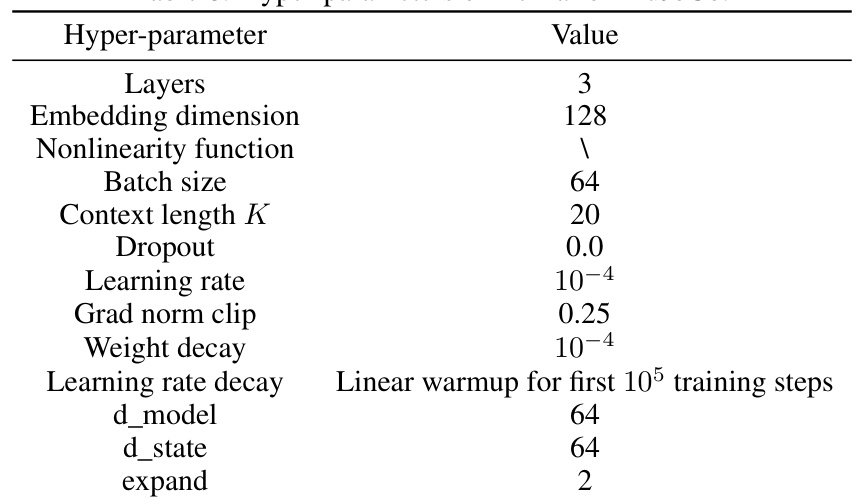

This table compares the computational resource usage of three different models: Decision Transformer (DT), Decision Convformer (DC), and Decision Mamba (DeMa) on Atari and MuJoCo tasks. It shows the training time per step, GPU memory usage, number of Multiply-Accumulate operations (MACs), and the total number of parameters for each model on each platform. This helps in understanding the efficiency and scalability of each model.

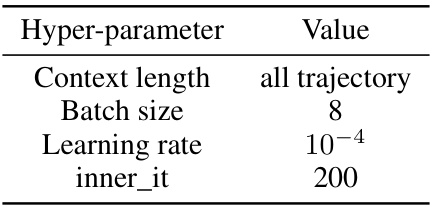

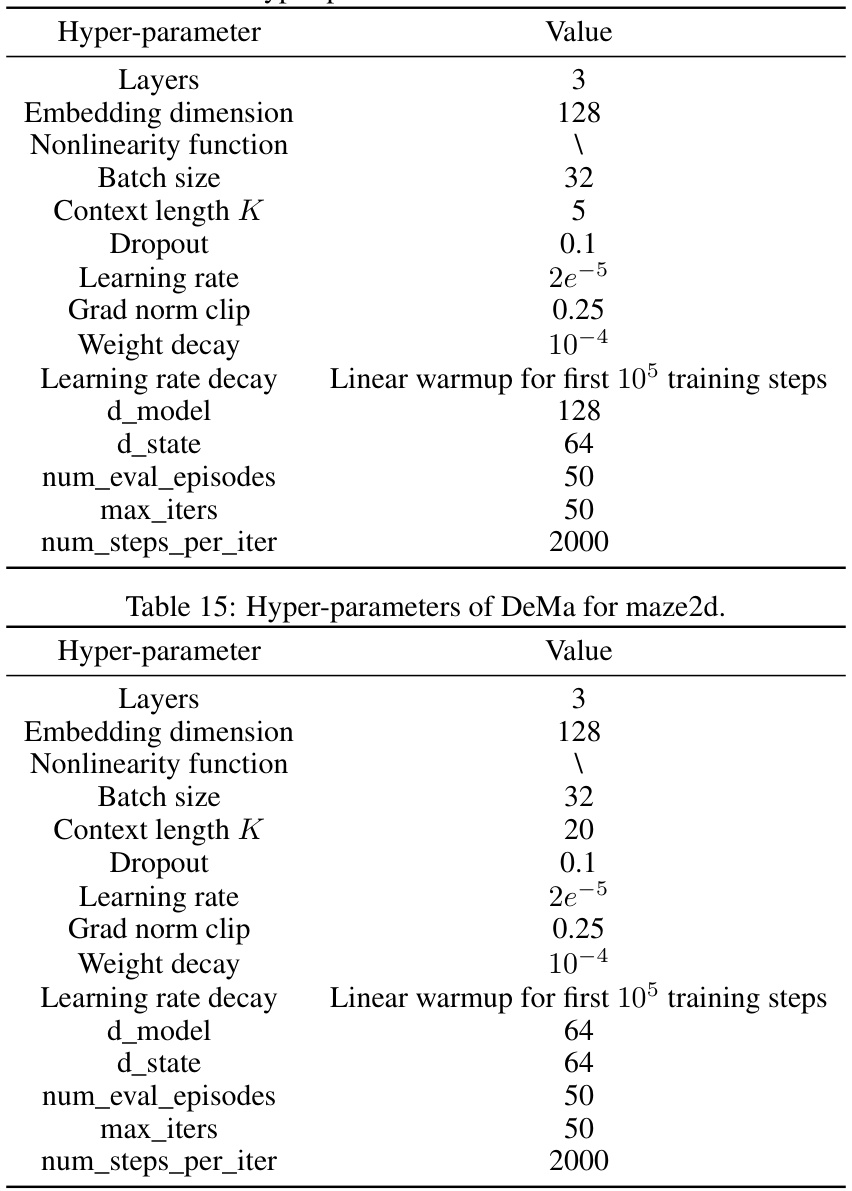

This table shows the hyperparameter settings used for the Decision Mamba (DeMa) model when applied to the MuJoCo environment. It lists values for parameters such as the number of layers, embedding dimension, nonlinearity function, batch size, context length (K), dropout rate, learning rate, gradient norm clipping, weight decay, learning rate decay schedule, and the dimensions of the model (d_model, d_state). These settings were chosen based on prior work and experimental tuning to optimize DeMa’s performance on MuJoCo tasks.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Transformer-like DeMa model when applied to Atari games. It includes settings for network architecture (layers, embedding dimension), activation function, batch size, sequence length (context length K), return-to-go conditioning (specific values for different games), dropout, learning rate, gradient clipping, weight decay, learning rate decay schedule, maximum number of epochs, Adam optimizer hyperparameters (betas), warmup tokens, final tokens, and model dimensions (d_model, d_conv, d_state, expand).

This table shows the hyperparameters used for the RNN-like version of Decision Mamba (DeMa) when applied to Atari games. It lists values for the context length, batch size, learning rate, and the number of inner iterations. Note that other hyperparameters remain consistent with those defined in Table 9, which is not shown here.

This table compares the performance of Decision Transformer (DT), RNN-like Decision Mamba (DeMa), and Transformer-like DeMa across eight Atari games. The results showcase the average normalized scores for each algorithm in each game, highlighting the significant performance improvement of the Transformer-like DeMa compared to the other methods. The table provides a quantitative assessment of the effectiveness of the different model architectures in the Atari environment.

This table presents a comparison of the average performance results of three different methods in MuJoCo environment: Decision Transformer (DT), RNN-like Decision Mamba (DeMa), and Transformer-like Decision Mamba (DeMa). The results are broken down by dataset (M, M-R representing medium and medium-replay), environment (HalfCheetah, Hopper, Walker), and method. The table shows the average performance across all three environments, highlighting the superior performance of the Transformer-like DeMa compared to the other two methods.

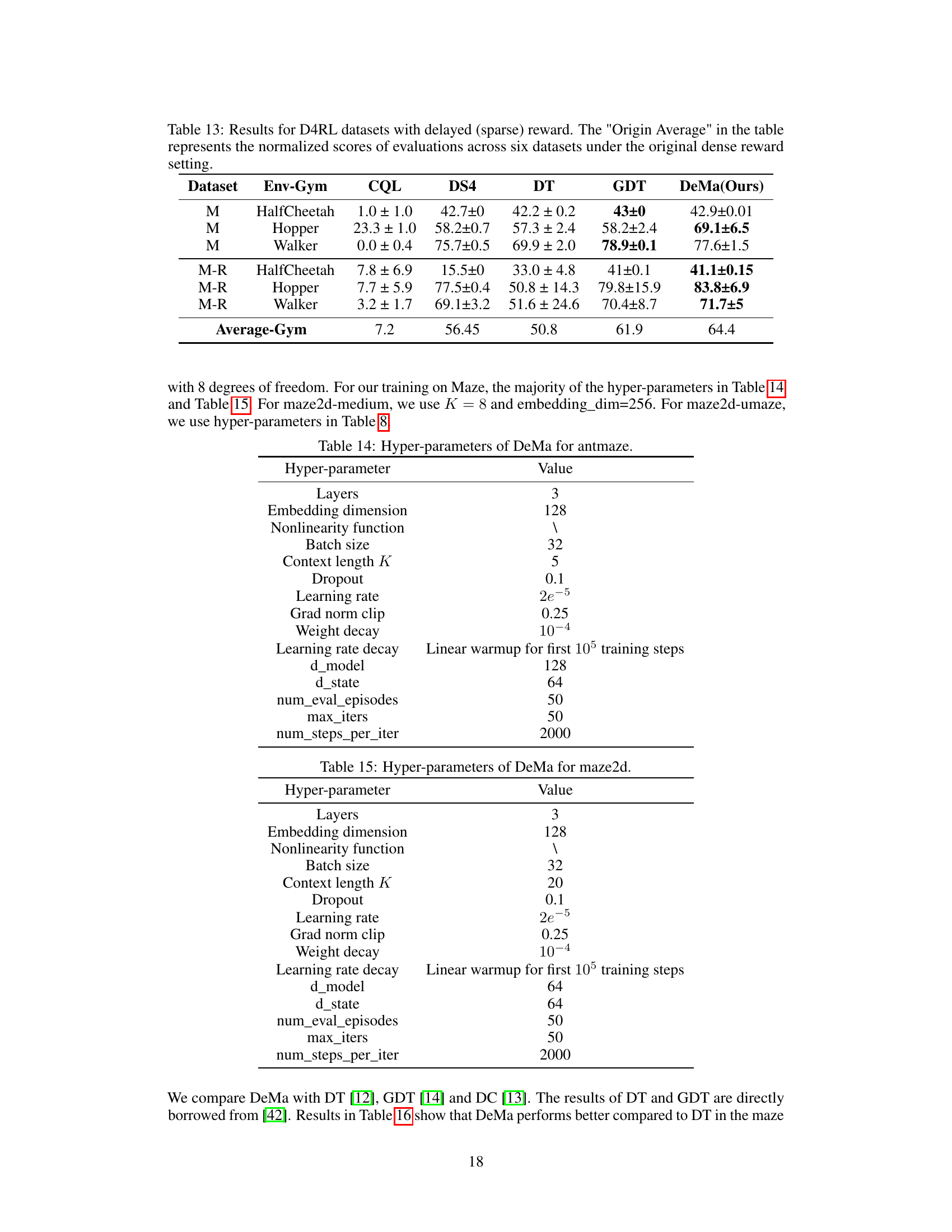

This table presents the results of evaluating the performance of DeMa (Decision Mamba) and several baseline algorithms on D4RL datasets with delayed rewards. It compares the normalized scores of DeMa against CQL, DS4, DT, and GDT across six different environments (three with standard reward and three with delayed reward). The ‘Origin Average’ column shows the average performance on the same datasets with the original dense reward scheme for comparison. The results highlight DeMa’s robustness to delayed rewards compared to some baseline algorithms.

This table presents the average performance results of three different models (Decision Transformer, RNN-like Decision Mamba, and Transformer-like Decision Mamba) on Atari and MuJoCo benchmark tasks. The results are normalized according to the methods described in references [60] and [11]. Detailed results are available in Appendix E of the paper. The table highlights the relative performance of each model in terms of average scores achieved.

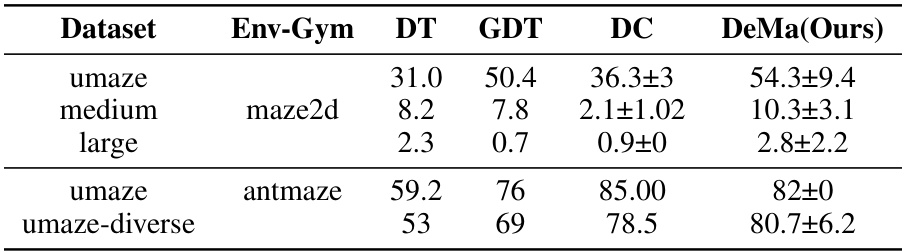

This table presents the results of DeMa, DT, GDT, and DC on maze2d and antmaze environments. The results show the normalized scores achieved by each method across various datasets (umaze medium, umaze large, umaze-diverse, antmaze umaze). It demonstrates the performance comparison of DeMa against several baselines on these long-horizon planning tasks.

This table presents the ablation study results on the impact of position embedding on DeMa’s performance. It compares the performance of DeMa with and without position embedding across different MuJoCo datasets (M and M-R) and environments (HalfCheetah, Hopper, Walker). The results demonstrate that removing position embedding leads to a slight improvement in average performance while substantially reducing the number of parameters.

This table compares the performance of three different models (DT, DeMa with post-projection residual block, and DeMa with pre-projection residual block) on nine MuJoCo tasks. It shows the average normalized scores for each model across three different datasets (M, M-R, and M-E) representing different data distributions. The table also lists the total number of parameters for each model, highlighting the parameter efficiency of DeMa.

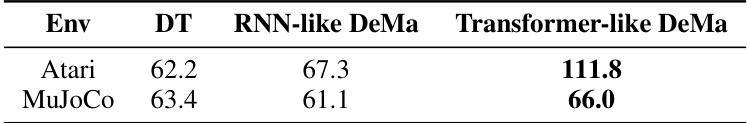

This table presents the baseline scores used for normalization in the MuJoCo and Atari environments. For each environment (Hopper, Halfcheetah, Walker2d in MuJoCo; Breakout, Qbert, Pong, Seaquest, Asterix, Frostbite, Assault, Gopher in Atari), it shows the random score and the expert/gamer score, representing the performance of a random agent and an expert/gamer respectively. These baseline scores provide a context for understanding the performance of the proposed DeMa algorithm relative to chance and human-level performance.

Full paper#