↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Federated Learning (FL) necessitates ’the right to be forgotten,’ leading to the development of Federated Unlearning (FU). However, current FU methods struggle with feature unlearning, lacking effective evaluation metrics and practical solutions for FL’s decentralized nature. Existing techniques are often computationally expensive and require participation from all clients. This creates a need for a more efficient and privacy-preserving approach.

Ferrari addresses these issues by introducing a novel framework that minimizes feature sensitivity in FL, based on the concept of Lipschitz continuity. This approach is efficient, requiring only local data from the unlearning client. The paper also introduces a novel metric for evaluating feature unlearning effectiveness and provides a theoretical guarantee of lower model utility loss compared to exact feature unlearning. Empirical results show Ferrari’s effectiveness across sensitive, backdoor, and biased feature removal scenarios, outperforming existing techniques while maintaining model utility.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for Federated Learning researchers as it tackles the significant challenge of Federated Unlearning, especially regarding feature unlearning, offering a novel solution that enhances privacy and efficiency. It also presents a new evaluation metric and theoretical analysis, deepening understanding in this field and opening avenues for future improvements in data privacy and model accuracy.

Visual Insights#

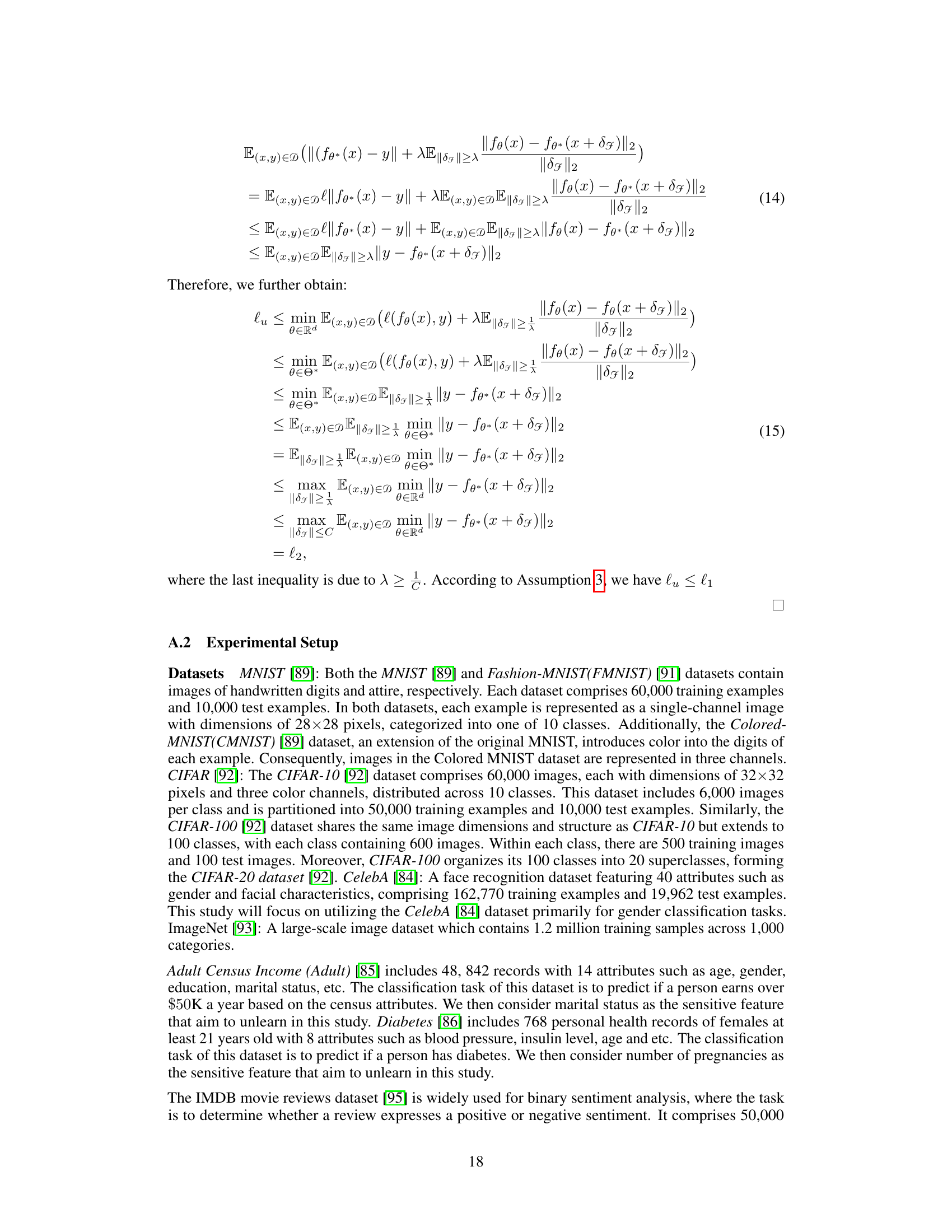

This figure demonstrates the challenge in evaluating the effectiveness of feature unlearning in federated learning (FL). Three images are shown: the original image (x), an image with the mouth region replaced by Gaussian noise (xG), and an image with the mouth region replaced by a black block (xB). The accuracy of a model trained on these perturbed images is significantly lower than the accuracy of a model trained on the original image, highlighting the difficulty of creating a suitable ground truth for evaluating feature unlearning in FL.

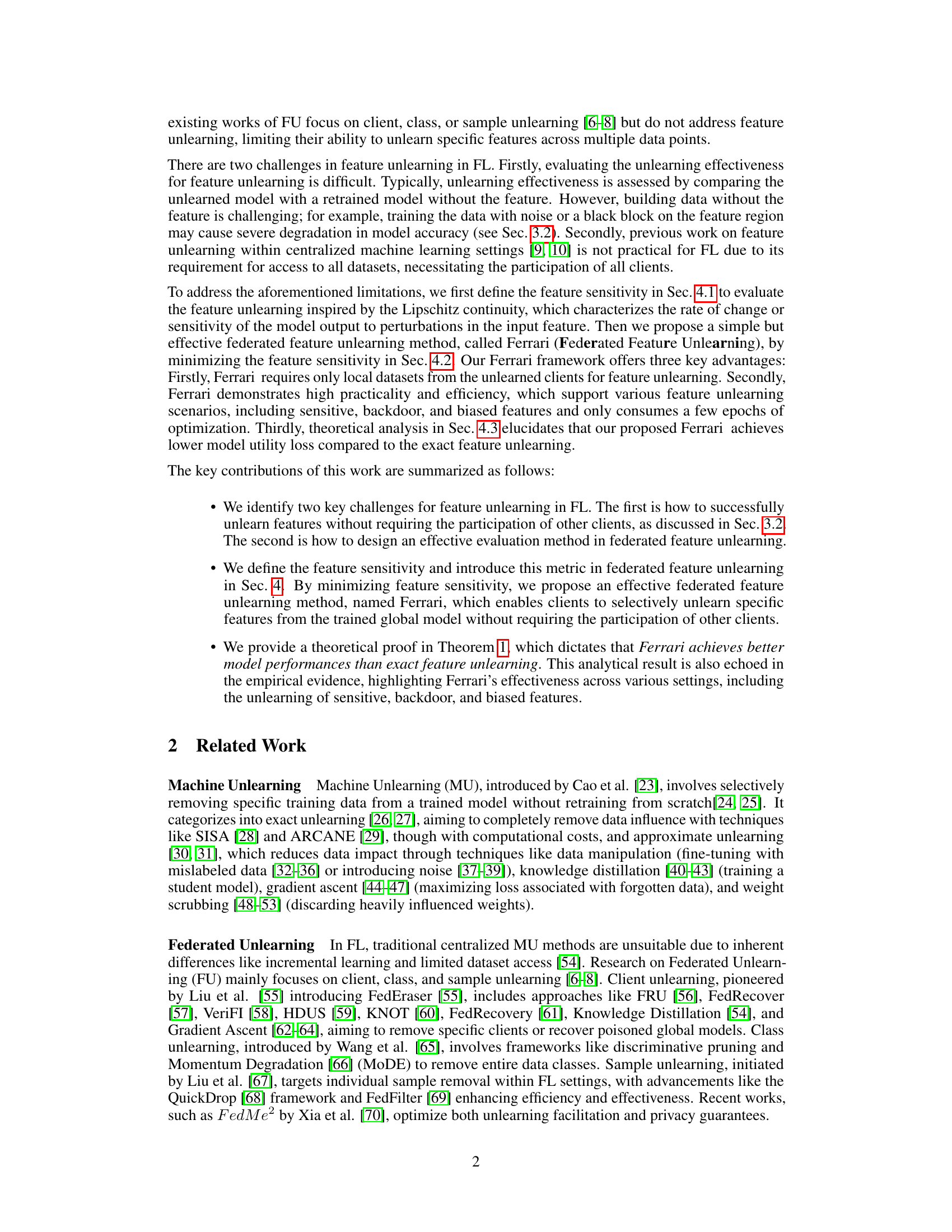

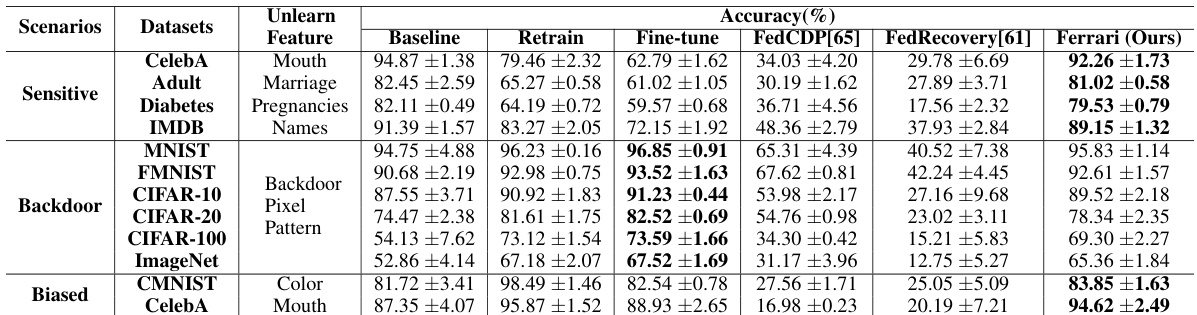

This table presents the accuracy results on the test dataset (Dt) for different unlearning methods and various unlearning scenarios. The unlearning scenarios include removing sensitive features (e.g., mouth from CelebA, marital status from Adult, pregnancies from Diabetes), backdoor features (pixel-pattern in CIFAR-10, CIFAR-20, CIFAR-100, ImageNet), and biased features (color in CMNIST and mouth in CelebA). The methods compared are Baseline (original model), Retrain (model retrained without the unlearned features), Fine-tune (model fine-tuned on the remaining data), FedCDP [65], FedRecovery [61], and the proposed Ferrari method. The accuracy metric assesses how well each method preserves the model’s performance on the test dataset after unlearning.

In-depth insights#

Federated Unlearning#

Federated unlearning (FU) addresses the crucial need for data removal in federated learning (FL) systems, aligning with privacy regulations. Existing FU methods primarily focus on removing entire clients, classes, or samples, overlooking the granularity of individual feature unlearning, which is critical for selective data deletion. This limitation hinders the ability to address more nuanced privacy concerns, such as removing only sensitive features while preserving overall model utility. The challenge lies in developing effective FU strategies that selectively eliminate feature influence without requiring extensive retraining and global data access, which are significant hurdles in the distributed nature of FL. A key focus of current research is defining metrics to accurately assess the effectiveness of feature unlearning and developing techniques that offer a balance between model utility and data privacy. Future work should focus on creating more efficient and privacy-preserving methods for feature unlearning, which would involve addressing computational limitations and minimizing the potential risk of model inversion attacks.

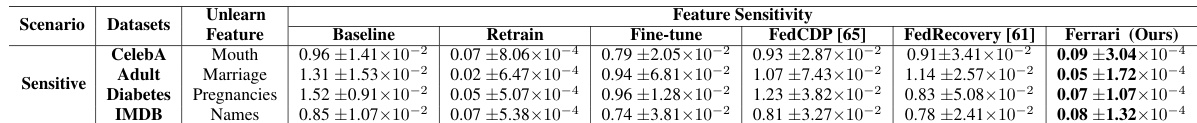

Feature Sensitivity#

The concept of “Feature Sensitivity” in this context is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of federated unlearning, particularly in the context of protecting sensitive data. It quantifies how much the model’s output changes in response to perturbations in a specific feature. This is directly tied to the goal of unlearning: if a feature is successfully unlearned, its sensitivity should be low, meaning changes to that feature minimally affect the model’s predictions. The authors use this metric to assess their proposed Ferrari framework, demonstrating its efficacy by showing that Ferrari minimizes feature sensitivity. This approach offers a significant advantage over previous methods which lacked a robust evaluation metric and often relied on unrealistic assumptions, such as having access to complete datasets without the feature of interest during the retraining process for comparison. Therefore, feature sensitivity provides a more practical and meaningful way to evaluate feature unlearning in federated settings. The mathematical grounding of feature sensitivity in Lipschitz continuity adds rigor to the evaluation process, solidifying the framework’s theoretical foundation and practical applicability.

Ferrari Framework#

The Ferrari framework, a novel federated feature unlearning approach, directly addresses the challenges of existing methods by minimizing feature sensitivity using Lipschitz continuity. This innovation allows for the selective removal of features from a global model without requiring the participation of all clients, enhancing privacy and practicality. Instead of relying on impractical retraining or influence function-based methods, Ferrari leverages a localized approach to minimize the model’s sensitivity to targeted features, thereby effectively unlearning them. The framework’s efficiency and effectiveness across various scenarios including sensitive, backdoor, and biased features are validated through theoretical analysis and experimental results. Ferrari’s key advantage lies in its ability to achieve significant feature unlearning with minimal participation, preserving both model accuracy and user privacy.

Empirical Results#

The empirical results section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims made in the introduction and methodology. A strong empirical results section should present clear, concise, and well-organized findings that are directly relevant to the research questions. It should include detailed descriptions of the datasets, experimental setup, evaluation metrics, and the results themselves. Visualizations, such as tables and figures, are essential for communicating complex results effectively. A thorough analysis of the results is also necessary, demonstrating how the findings support or contradict the hypotheses. Furthermore, a discussion of the limitations of the study and potential sources of error is important. Finally, a thoughtful comparison of the results with previous work in the field helps place the current findings in context and highlight their novelty and significance. Robust statistical analysis, error bars, and discussion of statistical significance are paramount for establishing the reliability of the findings. Ultimately, a well-written empirical results section should present a compelling and credible case for the research paper’s central claims.

Future Works#

Future work in federated unlearning could explore several promising directions. Improving the efficiency of Ferrari, perhaps through more sophisticated optimization techniques or a different approach to feature sensitivity, would significantly enhance its practical applicability. Addressing the issue of non-IID data more robustly is crucial, as real-world federated learning scenarios rarely involve perfectly IID data. Investigating the impact of different noise distributions or advanced techniques like differential privacy to enhance privacy and data protection should be explored. Extending Ferrari to different model architectures beyond classification models, including generative models and large language models, is essential to broaden its utility. Finally, a rigorous empirical evaluation on a much larger scale and across diverse datasets, including real-world data, is needed to confirm its effectiveness and identify potential limitations more comprehensively.

More visual insights#

More on figures

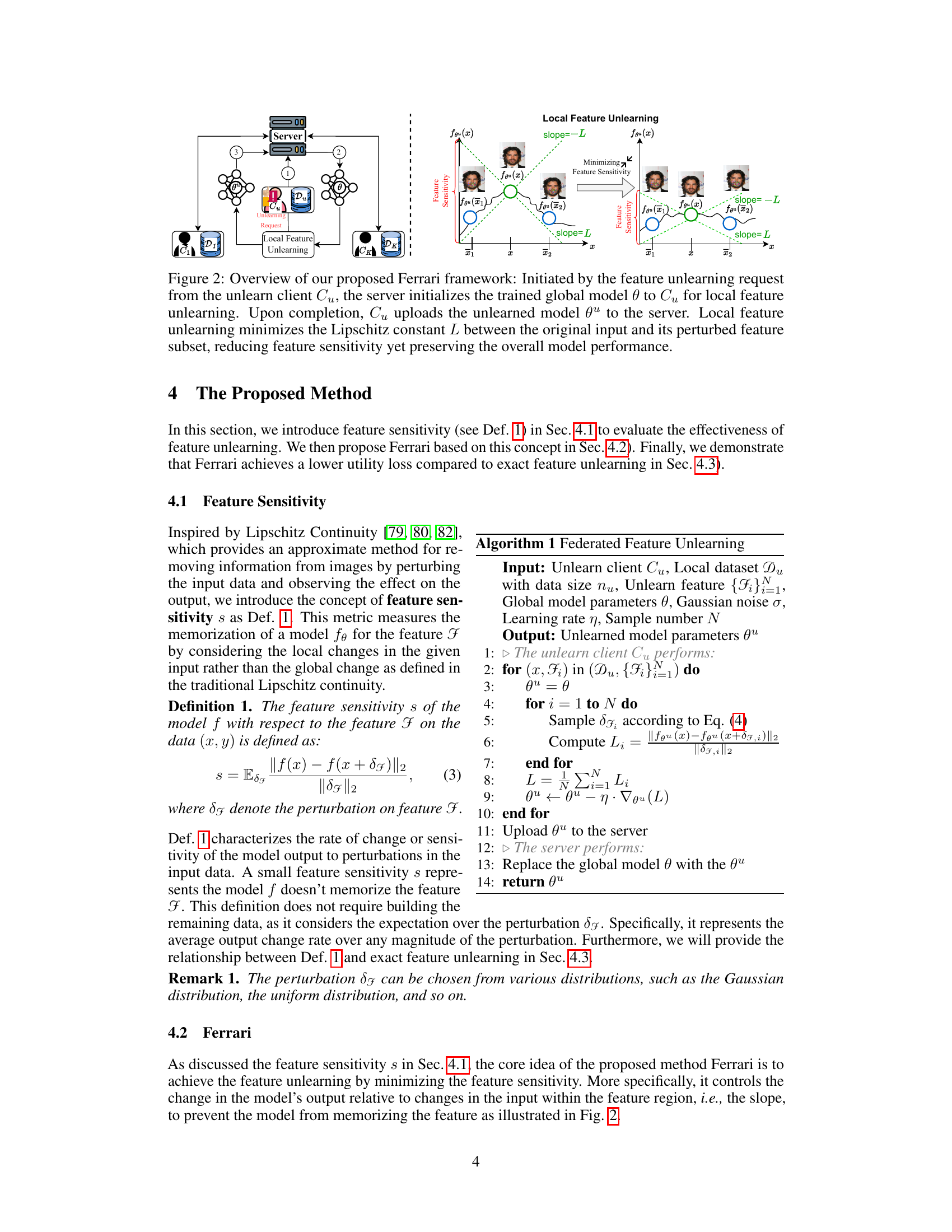

This figure illustrates the Ferrari framework’s workflow. A client requests feature unlearning (step 1). The server sends the model to the client (step 2). The client performs local feature unlearning, minimizing feature sensitivity by reducing the model’s output change rate relative to changes in the specified input feature (the slope in the graph, step 3). The client then uploads the updated model back to the server (step 4).

This figure shows examples of pixel-pattern backdoor features added to different datasets. A small pattern is added to images in MNIST, FMNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-20, and CIFAR-100. The top row shows the original image, and the bottom row shows the image with the added backdoor trigger. This trigger is intended to cause the model to misclassify images regardless of their actual content.

This figure shows the distribution of biased datasets used in the experiments for biased feature unlearning. The top row shows examples from the CMNIST dataset, illustrating bias towards color patterns. For example, the digit ‘3’ is shown in blue and green, and the digit ‘8’ is shown in green and blue. The bottom row shows examples from the CelebA dataset, illustrating bias towards gender and smiling attributes. For example, images of men and women are shown, along with images with or without smiles, highlighting the bias present within the training data.

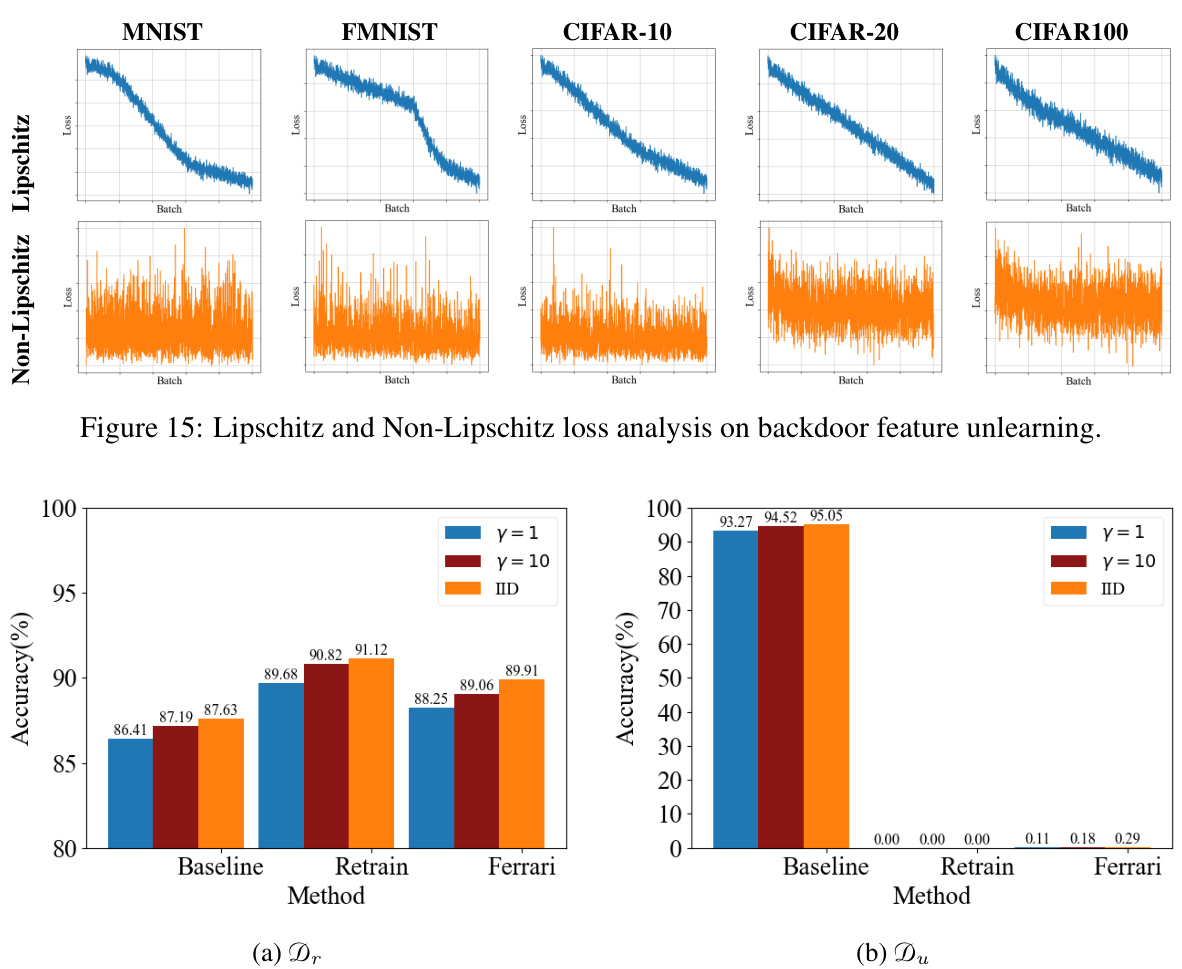

This figure shows the results of a model inversion attack (MIA) on the CelebA dataset after unlearning the ‘mouth’ feature. It compares the original image (‘Target’) with the reconstructions generated by the Baseline model (which didn’t undergo unlearning), the Retrain model (which was retrained without the mouth feature), and the Ferrari model (the proposed unlearning method). The goal is to demonstrate that Ferrari effectively prevents reconstruction of the unlearned feature (mouth), protecting privacy, while the Baseline and Retrain models fail to do so.

This figure shows the results of a model inversion attack (MIA) on the CelebA dataset after unlearning the ‘mouth’ feature. It compares the MIA reconstructions from the Baseline model (which did not undergo unlearning), a Retrained model (trained without the mouth feature), and the Ferrari model (which used the proposed federated feature unlearning method). The goal is to visually demonstrate the effectiveness of Ferrari in preventing reconstruction of the unlearned feature. Successful unlearning should result in poor reconstruction of the ‘mouth’ in the Ferrari model’s results, indicating that the model no longer retains information about this feature.

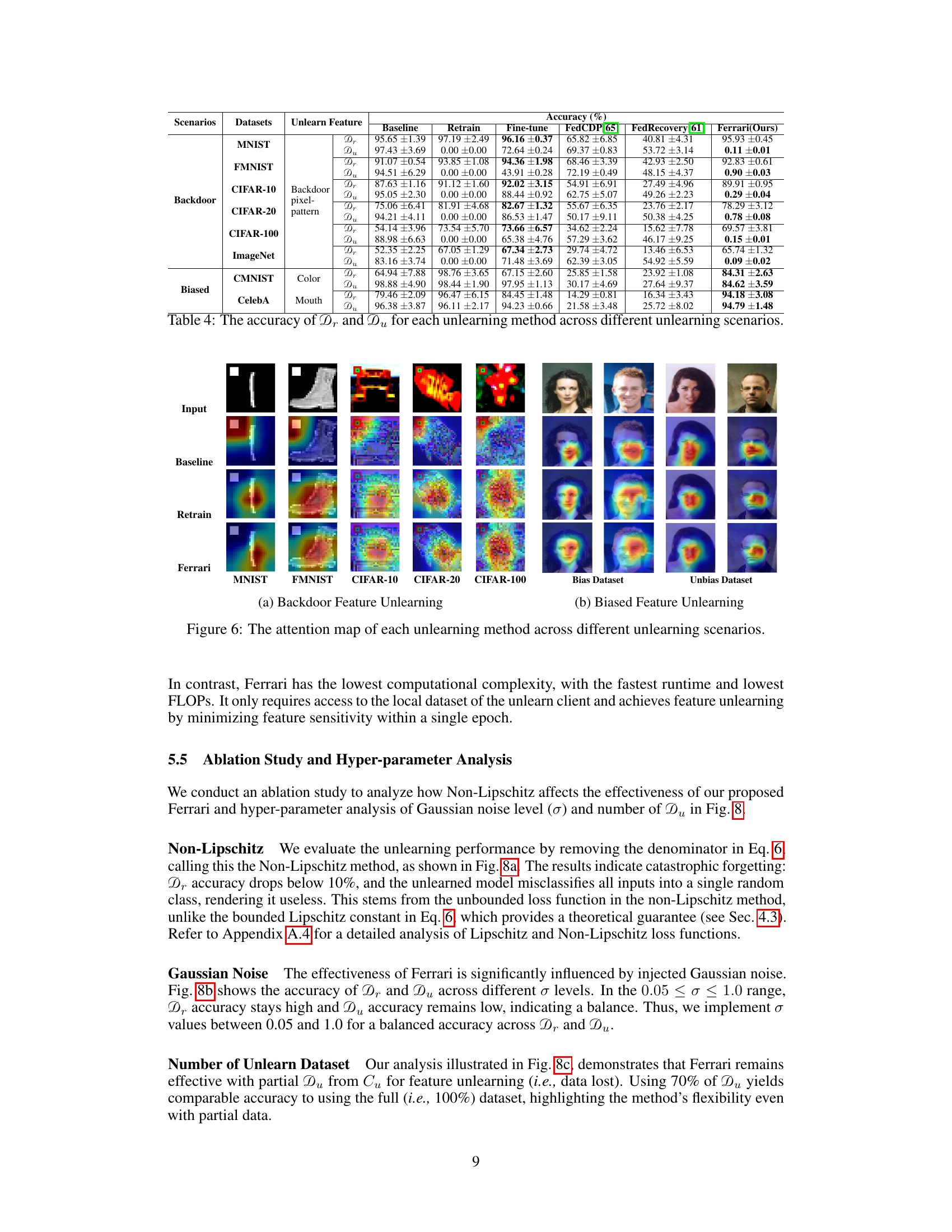

This figure compares the computational efficiency of different federated unlearning methods. It shows a bar chart visualizing the runtime (in seconds) and FLOPs (floating point operations) for each method. The methods are: Retrain, Fine-tune, FedCDP, FedRecovery, and the proposed Ferrari method. The results demonstrate that the Ferrari method has significantly lower runtime and FLOPs compared to other methods, suggesting its superior efficiency for federated feature unlearning.

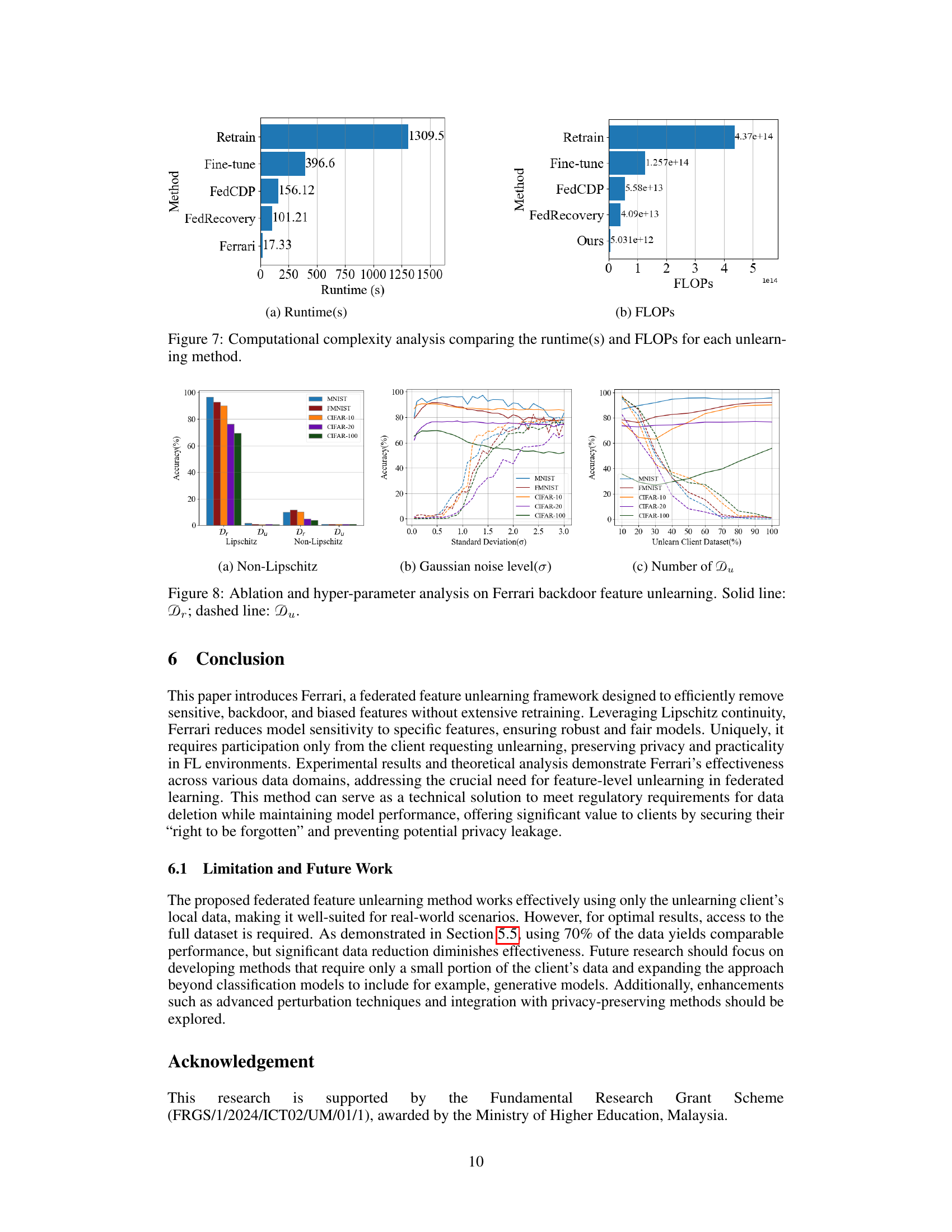

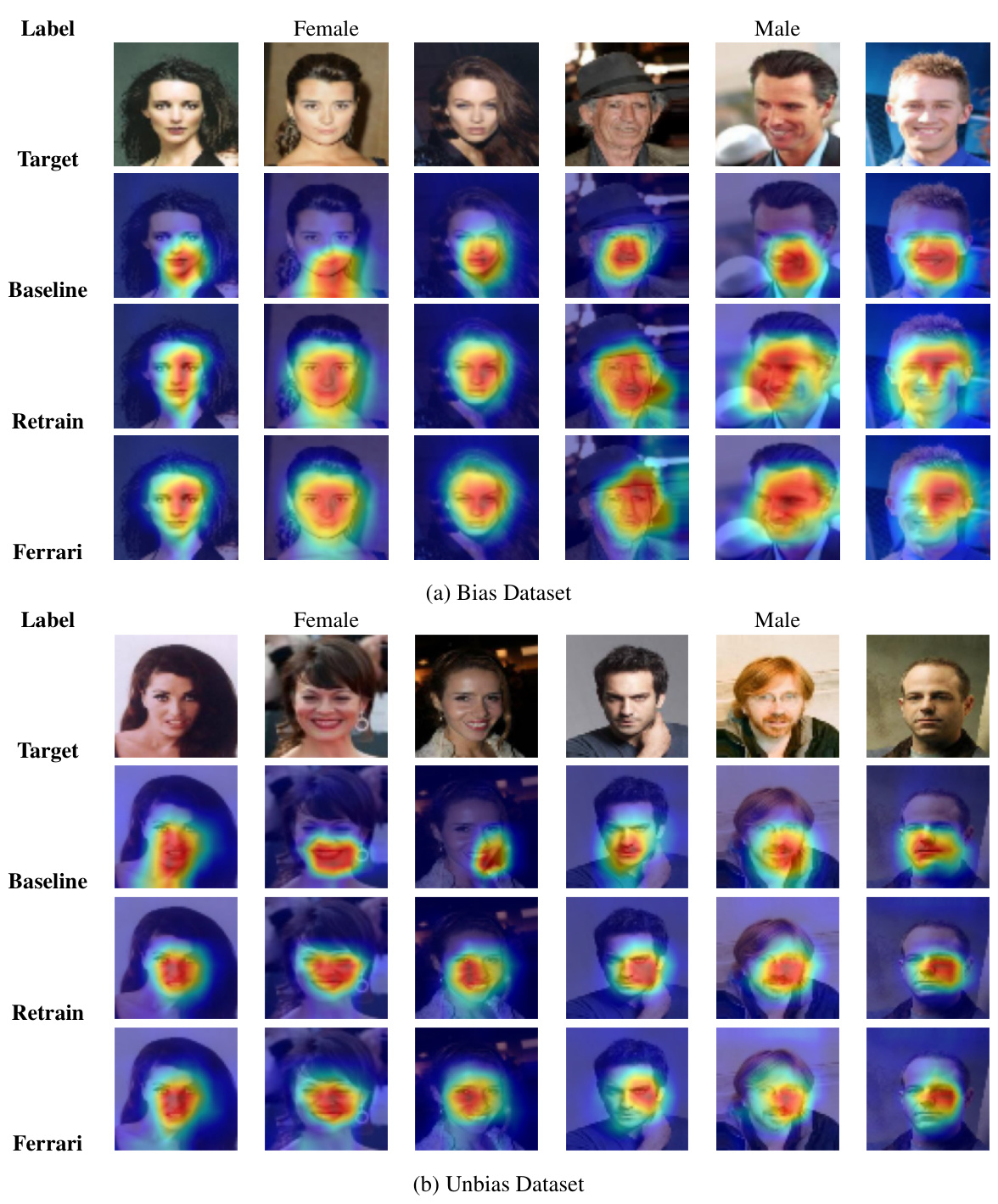

This figure shows the ablation study and hyperparameter analysis of the proposed Ferrari framework for backdoor feature unlearning. The ablation study (a) compares the performance using the Lipschitz loss function (as used in Ferrari) against a Non-Lipschitz variant to highlight the importance of the bounded optimization provided by Lipschitz continuity. The hyperparameter analysis (b) shows the effects of varying the standard deviation (σ) of the Gaussian noise added during perturbation on the accuracy of the retain (Dr) and unlearn (Du) datasets. Finally (c) shows the effect of using different proportions of the unlearn client’s dataset (Du) on the accuracy of the retain and unlearn datasets. The results highlight the importance of the Lipschitz loss and the impact of the hyperparameters on the effectiveness of feature unlearning.

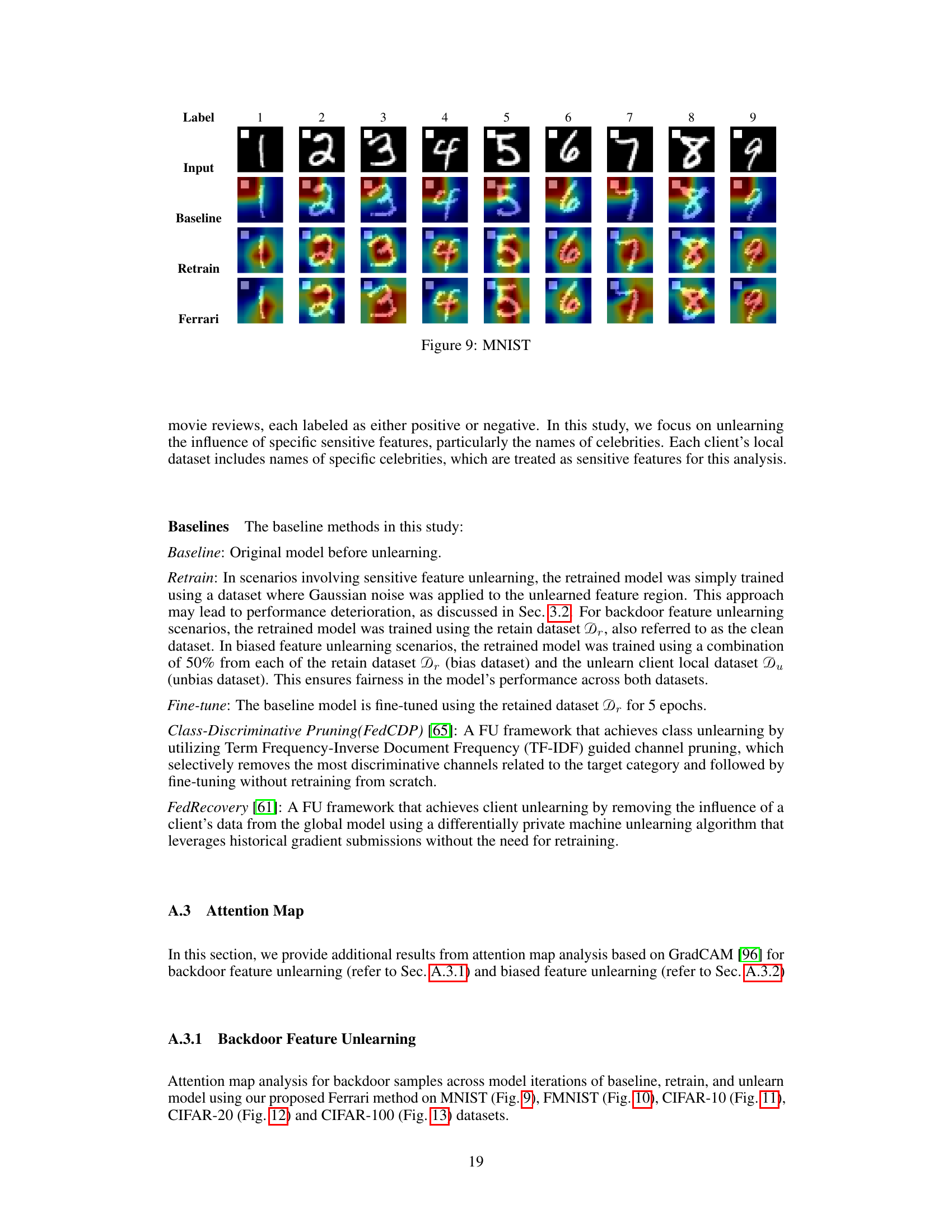

The figure displays attention maps for MNIST dataset, showcasing the attention patterns of the baseline, retrained, and Ferrari (proposed method) models on digits 0-9. It helps visualize how each model focuses on different parts of the digit images, illustrating the change in attention patterns after feature unlearning using the Ferrari model.

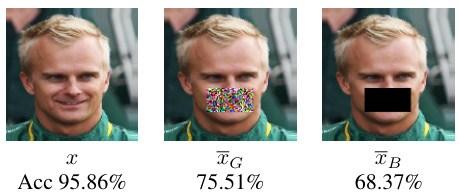

This figure shows the attention map analysis for backdoor samples across model iterations of baseline, retrain, and unlearn model using the proposed Ferrari method on the FMNIST dataset. The GradCAM attention maps are shown for each class, and for each model (Baseline, Retrain, Ferrari). This visualization helps understand how each model focuses on different features when making predictions, and how the unlearning process affects the model’s attention mechanism.

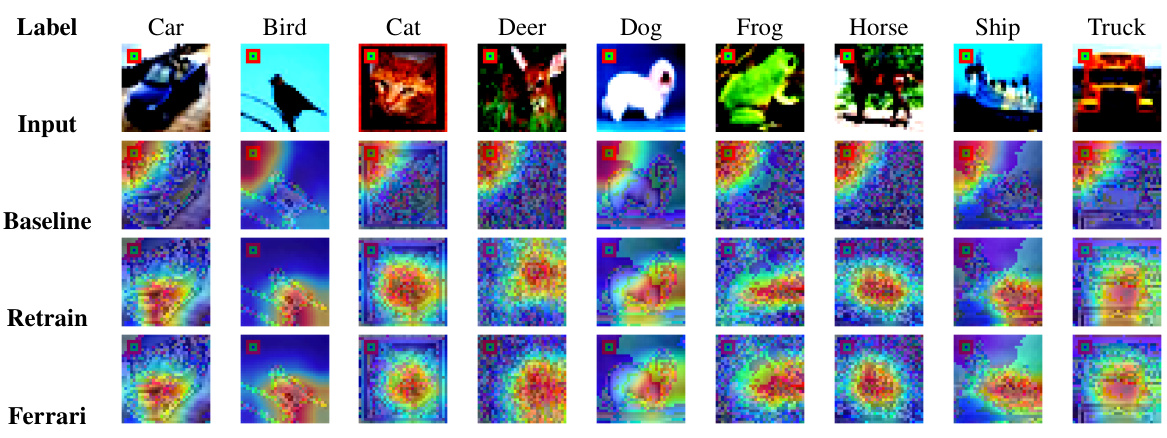

This figure shows the attention maps for CIFAR-10 dataset across different iterations of baseline, retrain, and unlearn models using the proposed Ferrari method. The attention maps visualize the regions of the input image that the model focuses on when making predictions. The red boxes highlight the backdoor trigger in the input images. The baseline model strongly focuses on the backdoor trigger, while the retrain and Ferrari models show a reduced focus on the trigger and more focus on relevant features for classification.

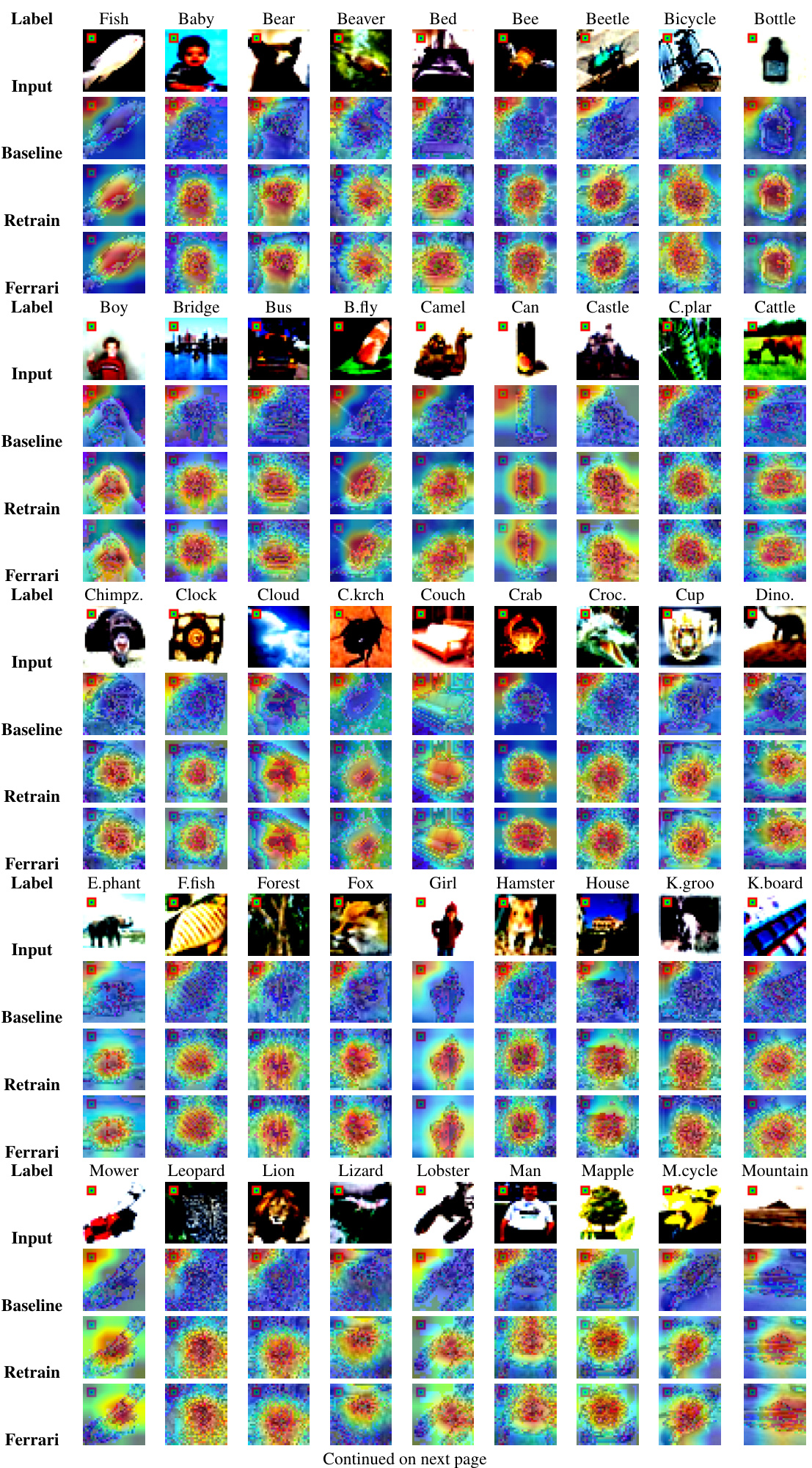

This figure shows the attention maps generated by GradCAM for the baseline model, the retrained model, and the model after applying the Ferrari method to unlearn the ‘mouth’ feature in the CelebA dataset. The top row displays images from the biased dataset, while the bottom row shows images from the unbiased dataset. Each column represents a different example image, allowing a visual comparison of how the attention shifts across models. The goal is to demonstrate Ferrari’s effectiveness in removing attention from the targeted feature (mouth) without drastically impacting the overall model performance.

This figure shows the results of a model inversion attack (MIA) on the CelebA dataset after unlearning the ‘mouth’ feature. It compares the reconstructions generated by the baseline model (which still retains information about the mouth), the retrained model (trained without the mouth feature), and the Ferrari model (using the proposed method). The goal is to demonstrate Ferrari’s effectiveness in preventing the reconstruction of the unlearned feature, thereby protecting privacy.

This figure shows the results of a model inversion attack (MIA) performed on the CelebA dataset after unlearning the ‘mouth’ feature. It visually compares the reconstructed images of the mouth feature from the baseline model, the retrained model, and the Ferrari model (the proposed method). The comparison highlights the effectiveness of the Ferrari framework in preventing reconstruction of the unlearned feature, thereby enhancing privacy.

This figure shows the results of a model inversion attack (MIA) on the CelebA dataset after unlearning the ‘mouth’ feature. It compares the reconstructed images from the Baseline model (before unlearning), the Retrain model (trained on data without the mouth feature), and the Ferrari model (the proposed unlearning method). The goal is to demonstrate that Ferrari effectively prevents the reconstruction of the unlearned feature, thus preserving privacy.

This figure shows the comparison of Lipschitz and Non-Lipschitz loss functions during the backdoor feature unlearning process on different datasets. The Lipschitz loss shows a steady decrease, while the Non-Lipschitz loss fluctuates significantly, highlighting the importance of Lipschitz continuity in stabilizing the unlearning process.

This figure shows the scalability analysis of the proposed Ferrari framework on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It compares the accuracy of the retain dataset (Dr) and the unlearn dataset (Du) across different numbers of clients (10, 20, and 50) for three methods: Baseline, Retrain, and Ferrari. The results demonstrate the robustness of Ferrari’s performance even with a large number of clients, indicating its suitability for large-scale federated learning settings.

More on tables

This table presents the accuracy results on the test dataset (Dt) for various feature unlearning methods across different scenarios. The scenarios include sensitive feature unlearning (removing sensitive features like ‘mouth’ from CelebA dataset), backdoor feature unlearning (removing backdoor triggers introduced during training), and biased feature unlearning (mitigating biases towards specific features in datasets). The methods compared are Baseline (original model), Retrain (model retrained without the target features), Fine-tune (model fine-tuned on the remaining dataset), FedCDP (Federated Unlearning via Class-discriminative Pruning), FedRecovery (Federated Unlearning using historical gradient information), and Ferrari (the proposed method). The table shows that Ferrari generally achieves higher accuracy compared to the other methods across various scenarios, suggesting its effectiveness in feature unlearning.

This table presents the feature sensitivity results for different unlearning methods on sensitive features. Lower feature sensitivity indicates better unlearning performance. The methods compared include Baseline (original model), Retrain (model retrained without sensitive features), Fine-tune (model fine-tuned without sensitive features), FedCDP, FedRecovery, and the proposed Ferrari method. The results are shown for four different datasets and sensitive features.

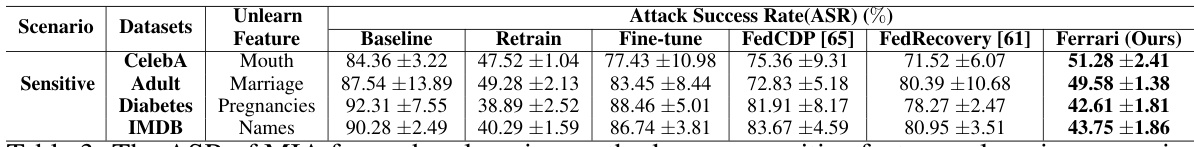

This table presents the Attack Success Rate (ASR) achieved by a Model Inversion Attack (MIA) for different feature unlearning methods across various sensitive feature datasets. It compares the performance of the proposed Ferrari method against baselines (Baseline, Retrain, Fine-tune, FedCDP, FedRecovery). Lower ASR values indicate better protection of sensitive features.

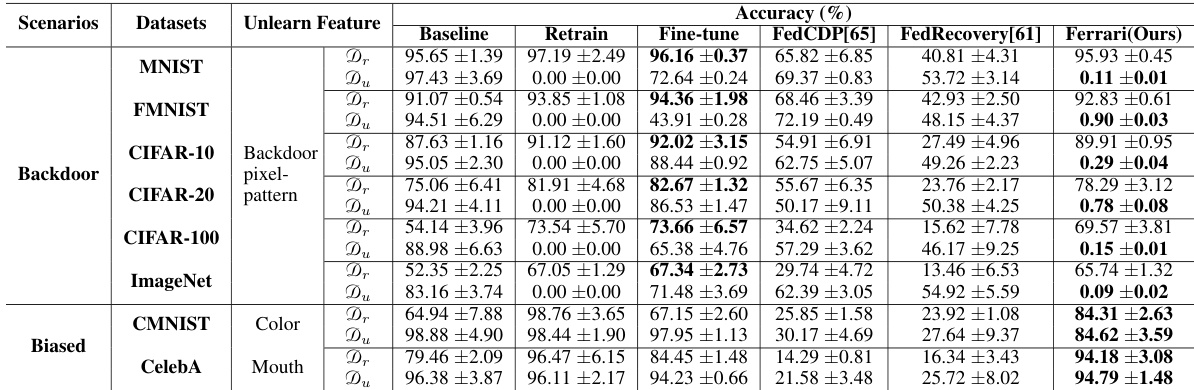

This table presents the accuracy results on the test dataset (Dt) for different unlearning methods across various scenarios (Sensitive, Backdoor, and Biased feature unlearning). Each row represents a different unlearning scenario and dataset, while each column shows the performance of various methods: Baseline (original model), Retrain (model retrained without the unlearned feature), Fine-tune (model fine-tuned on the remaining data), FedCDP, FedRecovery, and Ferrari (the proposed method). The accuracy values are expressed as percentages with standard deviations. This table helps to evaluate the effectiveness of different methods in preserving model utility during the feature unlearning process.

Full paper#