↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning models exhibit bias towards protected groups, often at the cost of accuracy. Existing fairness-focused active learning methods typically require annotating sensitive attributes, raising privacy concerns. This creates a fairness-accuracy trade-off that is difficult to overcome.

This paper introduces Fair Influential Sampling (FIS), a novel active learning approach that addresses these issues. FIS scores data points based on their influence on fairness and accuracy using a small validation set without sensitive attributes. It then selects the most influential samples for training, improving model fairness without compromising accuracy. The algorithm’s effectiveness is demonstrated through theoretical analysis and real-world experiments, providing upper bounds for generalization error and risk disparity.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers striving for fairness in machine learning. It offers a novel active sampling approach that avoids the typical fairness-accuracy trade-off and doesn’t need sensitive attributes for training, opening new avenues for research in privacy-preserving fairness.

Visual Insights#

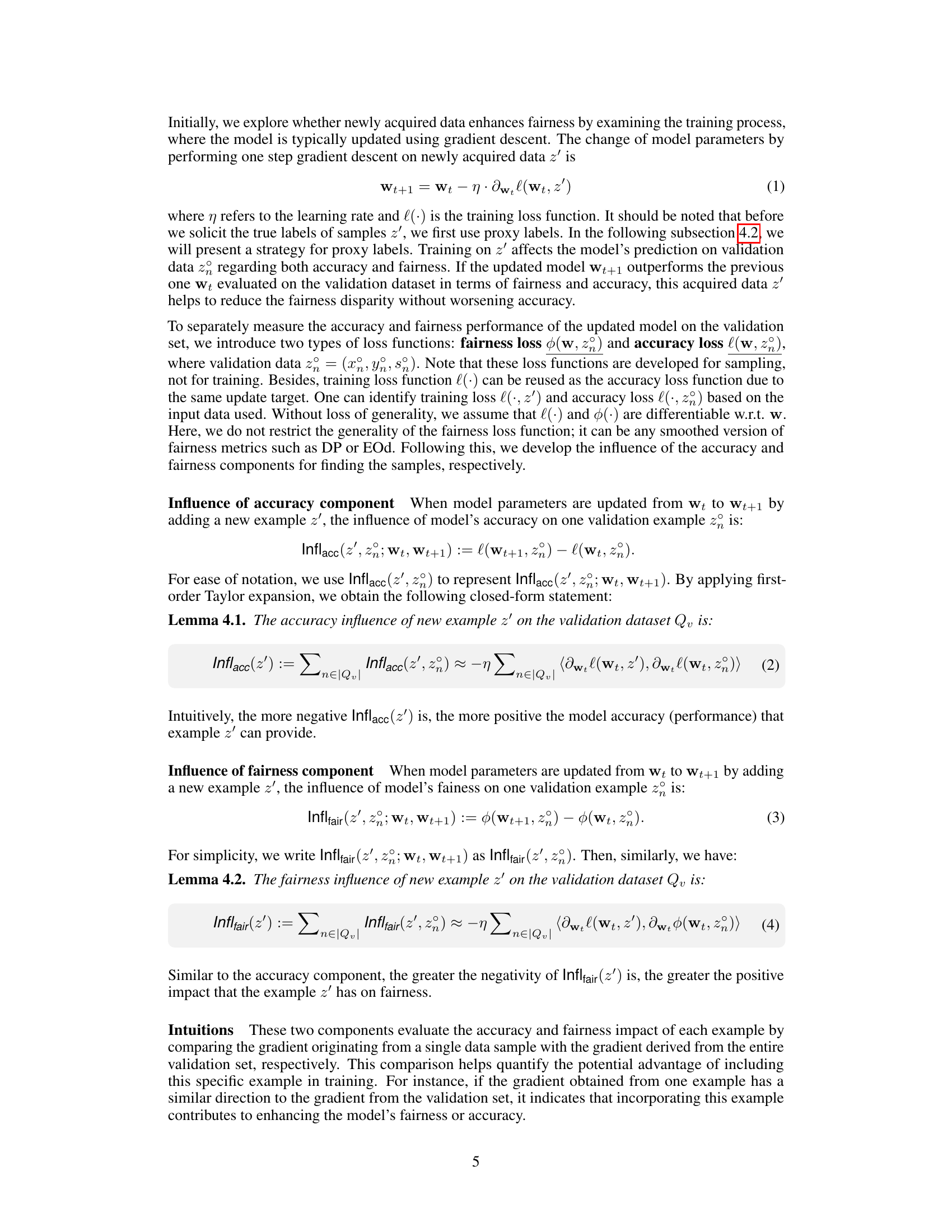

This figure compares Pareto frontiers for models trained on datasets with different sizes (scarce vs. rich data). The x-axis represents the model error rate, and the y-axis represents fairness violation. The plot shows that a model trained on a larger dataset (rich data) achieves a better Pareto frontier, allowing for lower error rates and lower fairness violations simultaneously than a model trained on a smaller dataset (scarce data). Acquiring more data shifts the Pareto frontier, leading to a superior trade-off point.

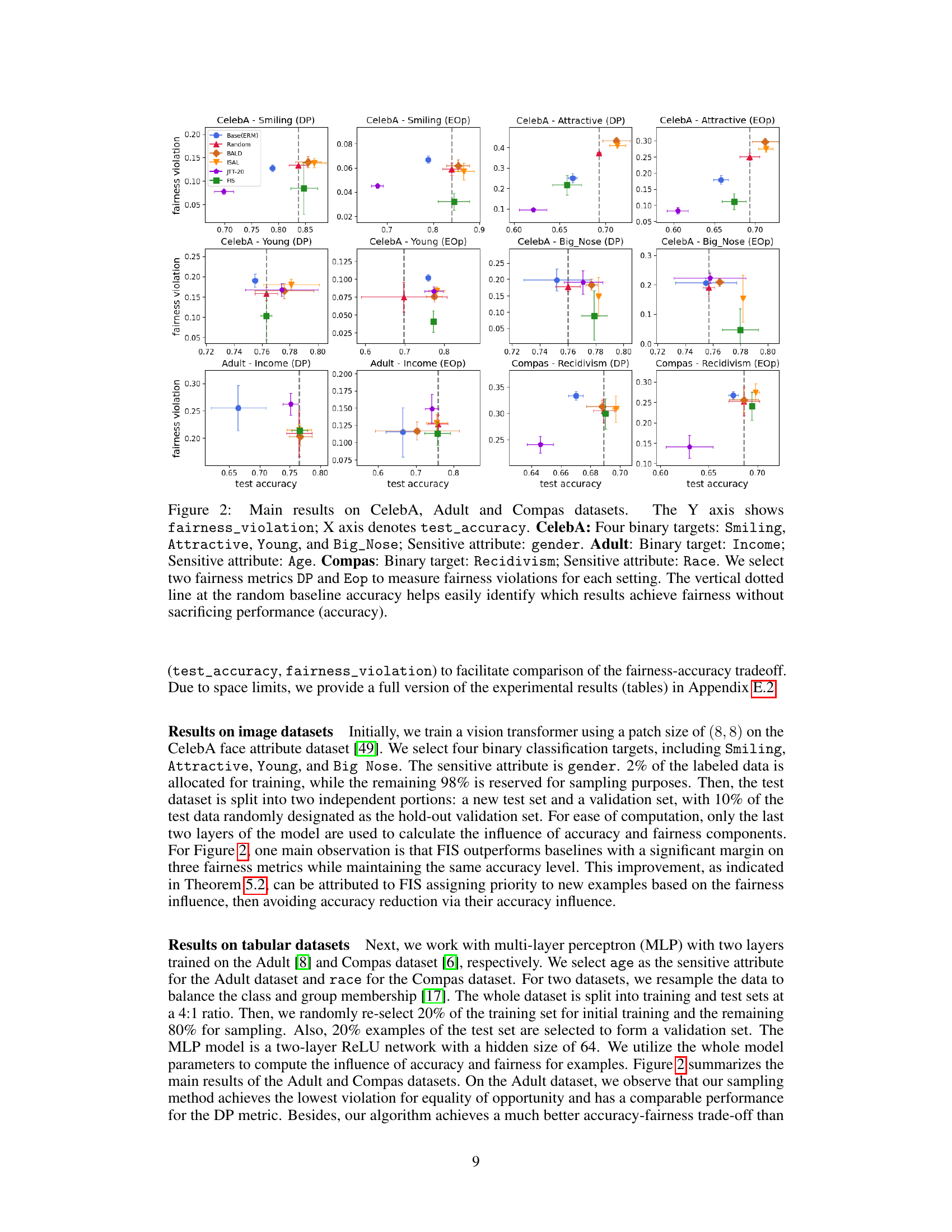

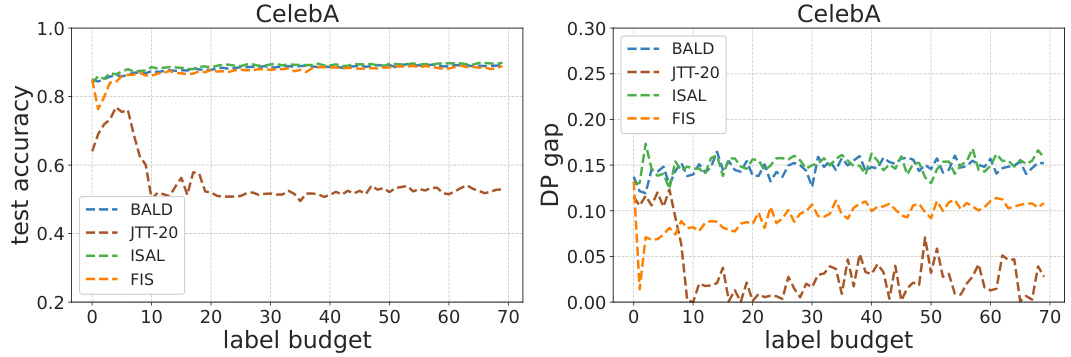

This table presents the results of experiments on the CelebA dataset, focusing on two binary classification tasks: predicting whether a person is young or has a big nose. The results compare the performance of several methods (Base(ERM), Random, BALD, ISAL, JTT-20, and FIS) across different fairness metrics (DP, EOp, EOd) and error tolerances (ε=0.05). Each method is evaluated based on its test accuracy and fairness violation. The table helps understand the effectiveness of different fairness-aware learning methods in improving model accuracy and fairness simultaneously, particularly when sensitive attributes like gender are involved.

In-depth insights#

Fairness Tradeoffs#

The concept of fairness tradeoffs in machine learning is crucial because striving for fairness often necessitates compromises in other critical aspects, such as accuracy. A common tradeoff is observed between model accuracy and fairness metrics, such as demographic parity or equal opportunity. Improving fairness might involve techniques like data preprocessing or algorithmic adjustments, but these can negatively impact model performance. This tradeoff is fundamentally linked to the inherent biases present within the training data, which may reflect existing societal inequities. Therefore, simply optimizing for fairness without considering accuracy can lead to models that are fair but lack practical utility. Researchers must carefully navigate this challenge by exploring the Pareto frontier, where any improvement in fairness requires a reduction in accuracy and vice versa. Ideally, methods should strive to achieve a balance, pushing the Pareto frontier towards a region where both high accuracy and substantial fairness improvements coexist. This often involves innovative data sampling or model training strategies that aim to minimize bias without sacrificing performance significantly. The difficulty in resolving these tradeoffs underscores the complexity of defining and achieving fairness in AI. Furthermore, different fairness definitions can produce drastically different trade-offs, highlighting the critical need for careful consideration of which fairness metric is most relevant to the application.

Active Sampling#

Active sampling, in the context of machine learning, is a crucial technique for efficiently training models with limited labeled data. It strategically selects the most informative instances from a larger pool of unlabeled data for manual annotation, thus maximizing the model’s performance with minimal labeling effort. The core idea revolves around intelligently ranking unlabeled data points based on their expected contribution to the model’s improvement. This contribution is usually measured via different criteria such as uncertainty, representativeness, and expected error reduction. Fairness considerations become critical when sensitive attributes are involved, as traditional active learning approaches could exacerbate existing biases by disproportionately selecting data points from certain demographic groups. Consequently, fair active learning methods are developed to ensure the selected data points reflect the desired fairness properties. This approach, however, typically requires annotations of sensitive attributes, which raises privacy and safety concerns. The novelty of the paper lies in its proposal for a tractable active sampling algorithm that circumvents this sensitive attribute requirement. This algorithm leverages the examples’ influence on both fairness and accuracy evaluated on a small validation set, thus enabling fairness improvements without compromising accuracy.

Influence Scores#

Influence scores, in the context of active learning and fairness-aware machine learning, represent a quantifiable metric that assesses the potential impact of including a specific data point in the training dataset. They aim to identify examples that will most effectively improve model fairness and accuracy simultaneously. This is a crucial aspect for methods that aim for fairness without sacrificing accuracy, as it helps to guide the selection process. The computation of influence scores needs to be efficient and avoid reliance on sensitive attributes, while still accurately reflecting the impact. The algorithm needs to be designed to balance between fairness and accuracy, ensuring that adding an example won’t lead to a degradation in accuracy, and that it moves toward a fairer model. Theoretical analysis is required to justify the effectiveness of the approach and provide generalization guarantees. It’s important to note that the actual calculation and interpretation of the influence scores can vary depending on the specific algorithm and fairness metric used. However, the general principle is to use influence scores as a strategic guide in the process of data selection to help achieve model fairness and accuracy.

FIS Algorithm#

The core of the proposed approach lies in its novel active sampling algorithm, termed FIS (Fair Influential Sampling). FIS cleverly circumvents the need for sensitive attribute annotations during training by leveraging a small, pre-annotated validation set. This is a crucial innovation as it directly addresses privacy concerns associated with collecting and using sensitive data. The algorithm operates by scoring each potential data point based on its estimated influence on both model accuracy and fairness, as evaluated on the validation set. This dual-scoring mechanism ensures a balanced selection of examples, prioritizing those that promise improvements in fairness without sacrificing accuracy. A theoretical analysis of FIS supports the intuition behind its design, demonstrating how acquiring more data, selected judiciously, improves the fairness-accuracy trade-off. The algorithm’s practical effectiveness is validated through extensive experiments on real-world datasets, showcasing its superiority over existing baselines. Overall, FIS presents a significant advancement in fair machine learning, offering a practical and privacy-preserving solution for building fairer and more accurate models.

Future Work#

Future work in this area could explore several promising directions. Firstly, the influence-guided active sampling approach could be extended to other fairness metrics beyond demographic parity and equalized odds. Secondly, investigating the impact of different proxy label generation methods on the overall performance and fairness of the system is crucial. Thirdly, a more robust theoretical analysis that considers the impact of noisy labels and distribution shift would strengthen the foundation of the approach. Finally, practical applications of the approach in high-stakes domains, coupled with thorough empirical evaluations of its effectiveness, are essential to demonstrate its real-world applicability and to address any potential ethical considerations. This would further solidify its position as a valuable tool for building fairer machine learning models.

More visual insights#

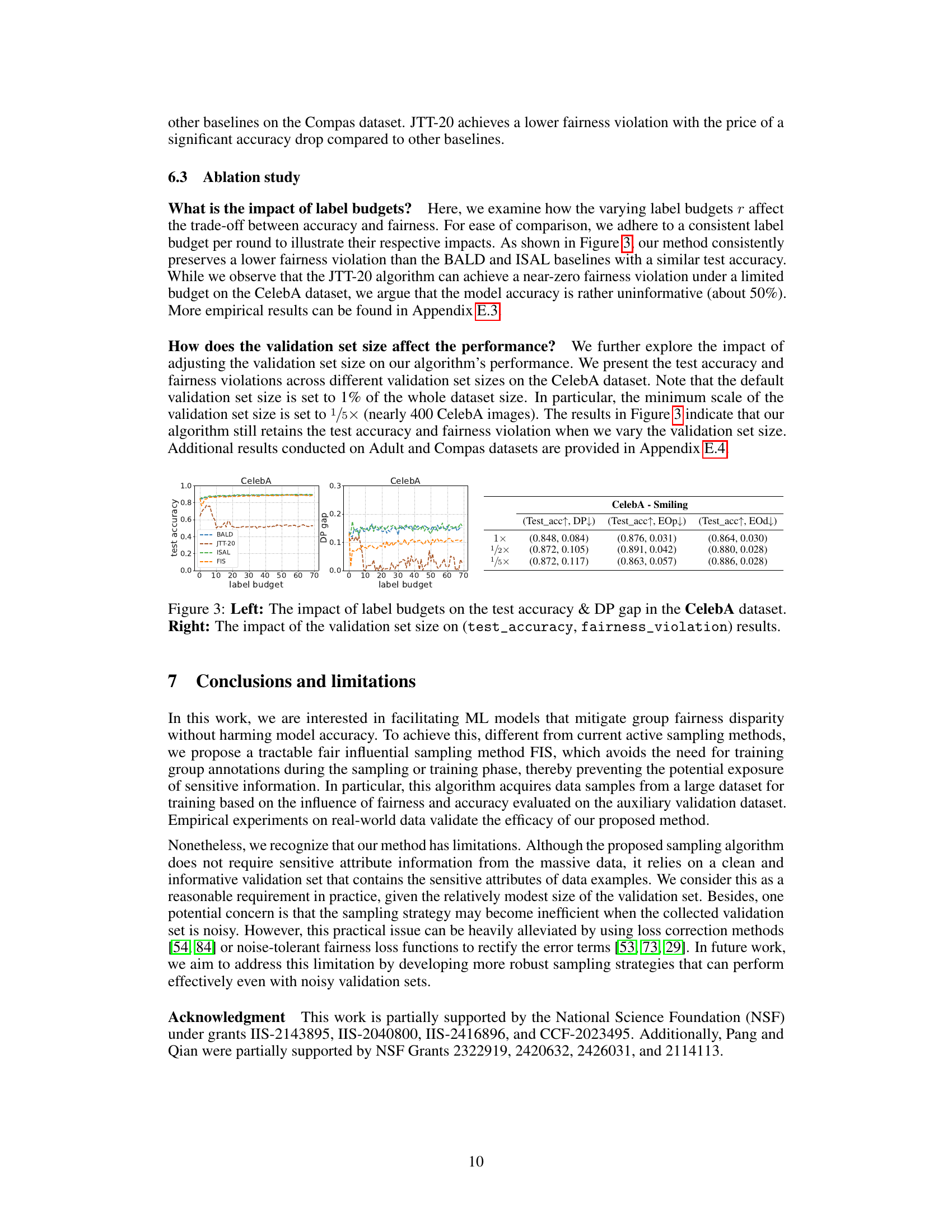

More on figures

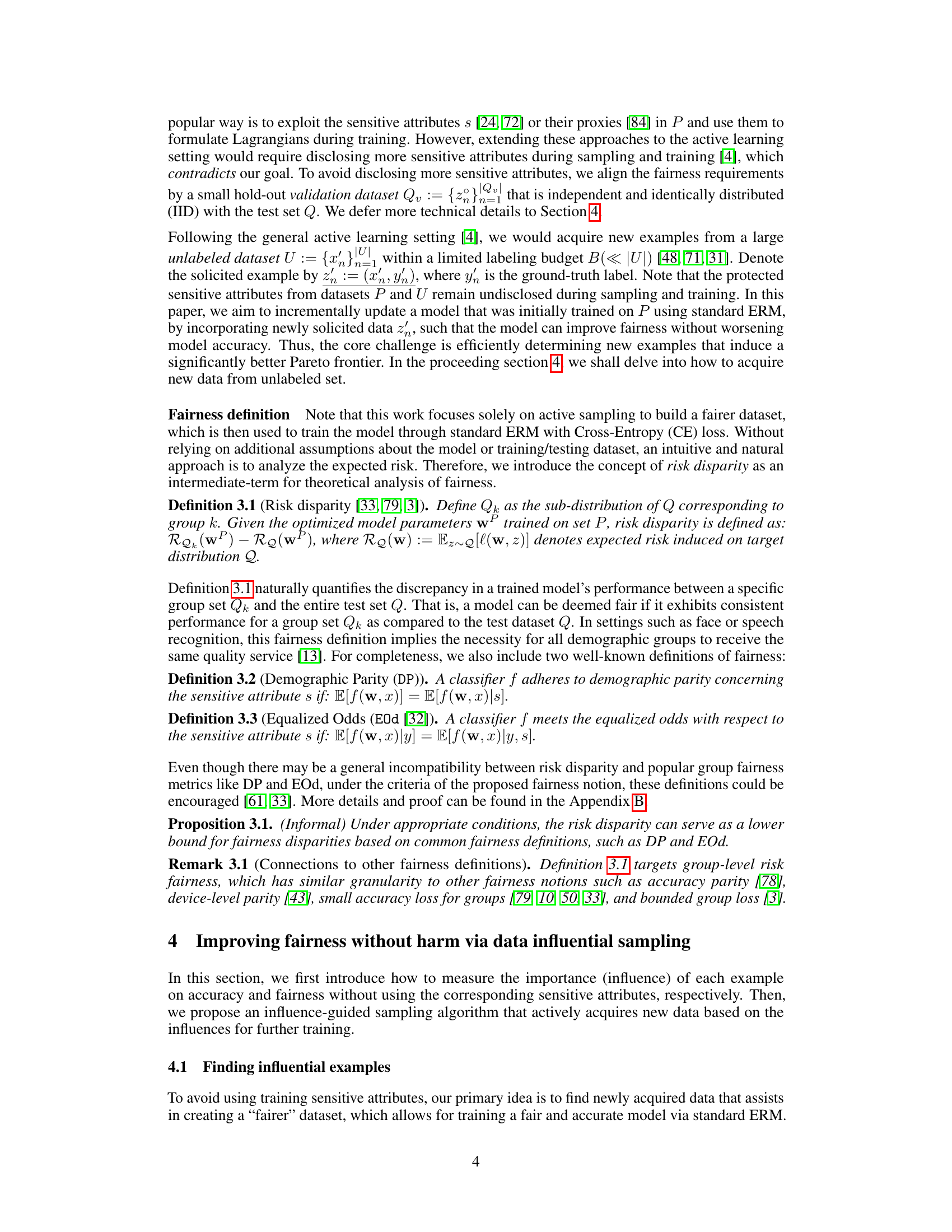

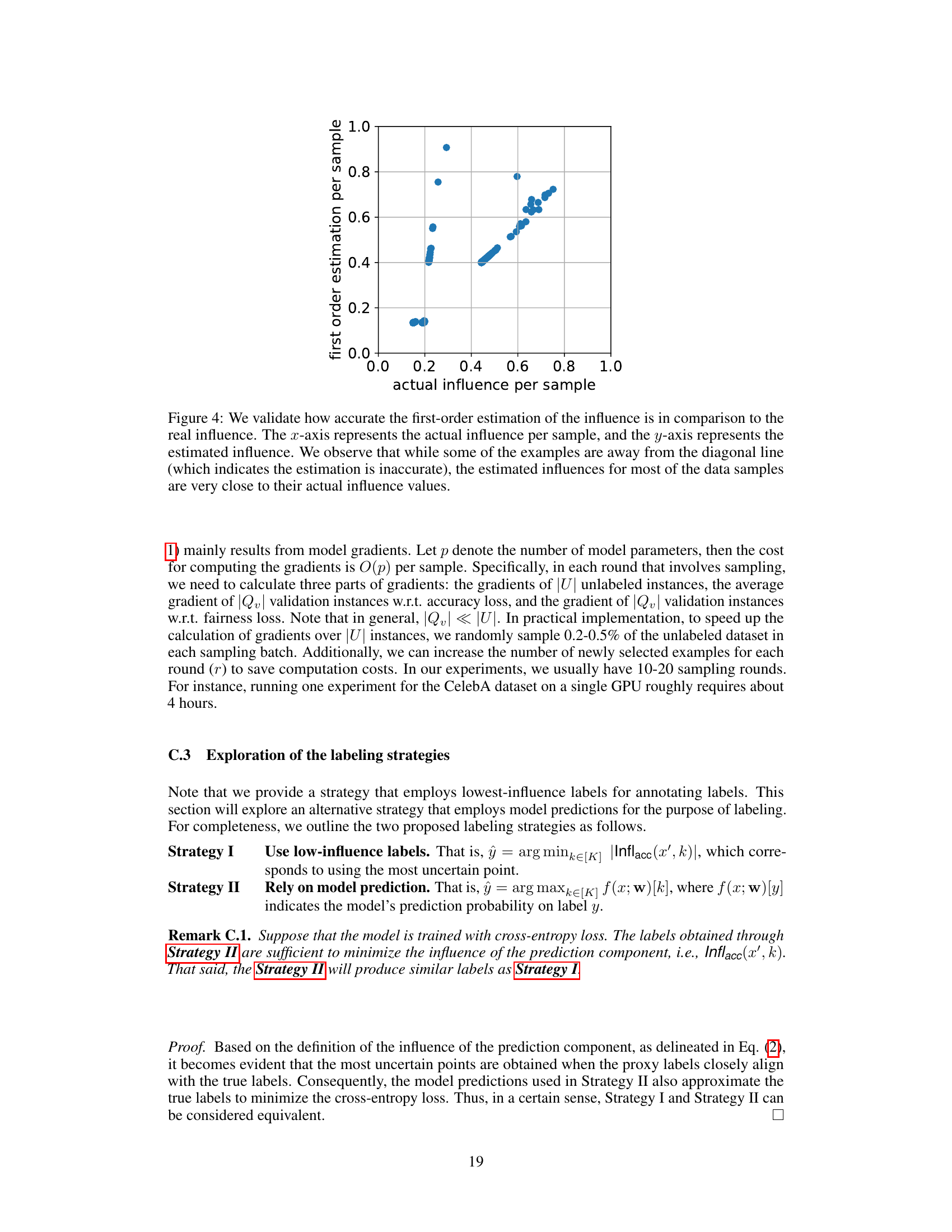

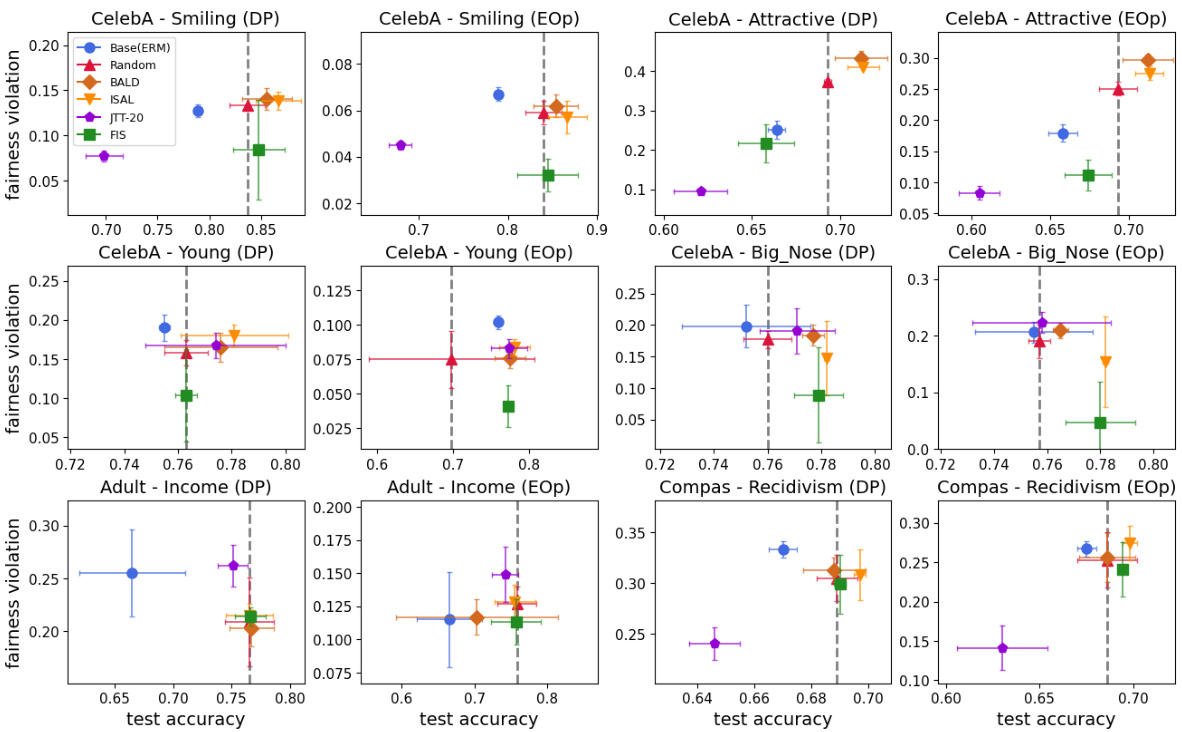

This figure compares the performance of different fairness-aware algorithms on three datasets (CelebA, Adult, and COMPAS) using two fairness metrics (DP and EOp). Each point in the graph represents the test accuracy and fairness violation of a particular algorithm on a specific dataset and metric. The goal is to achieve low fairness violation while maintaining high test accuracy. The vertical dotted line indicates the baseline accuracy achieved by a random model. The results show that the proposed FIS algorithm significantly improves fairness without sacrificing accuracy, surpassing other existing methods.

This figure compares the performance of different fairness-aware machine learning methods on three real-world datasets (CelebA, Adult, and COMPAS). The Y-axis represents the fairness violation (measured using demographic parity and equality of opportunity), while the X-axis shows the test accuracy. Each dataset and fairness metric is shown as a separate graph. The figure demonstrates that the proposed Fair Influential Sampling (FIS) method achieves a better trade-off between fairness and accuracy than several baseline methods. The vertical dotted line indicates the baseline accuracy achieved by random sampling.

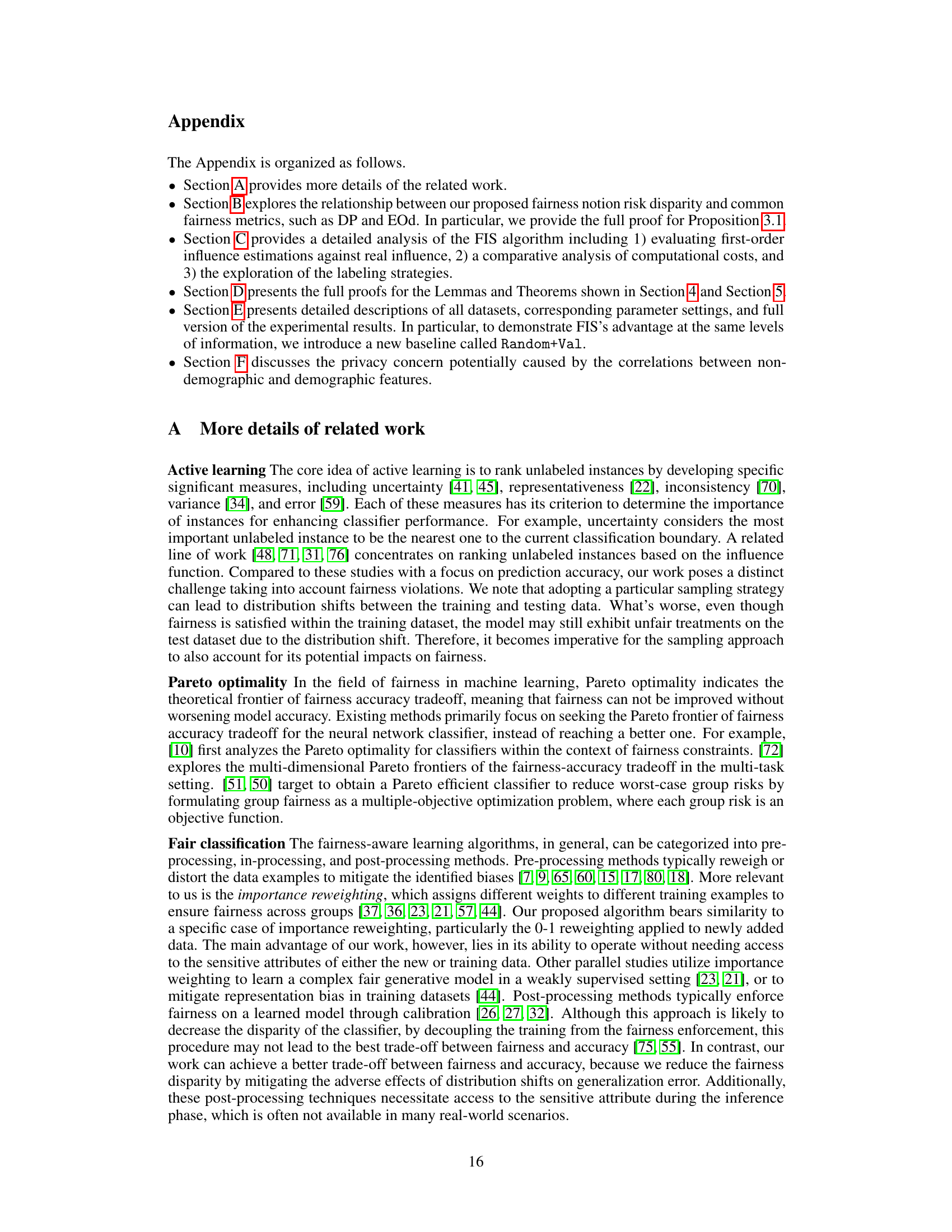

This figure validates the accuracy of the first-order approximation used to estimate the influence of a data sample on model accuracy and fairness. The plot shows a strong positive correlation between the actual influence and the first-order estimation. Although some points deviate from the diagonal line representing perfect agreement, most of the points cluster around it, indicating that the first-order approximation provides a reasonably accurate estimate.

This figure compares the performance of different fairness-aware active learning algorithms on three datasets (CelebA, Adult, and Compas). The y-axis represents the fairness violation (lower is better), while the x-axis represents the test accuracy (higher is better). Each point represents a different algorithm. The dotted vertical line indicates the baseline accuracy achieved by random sampling. The figure shows that FIS generally achieves better fairness-accuracy tradeoffs than other algorithms tested.

The figure compares the performance of different fairness-aware algorithms (Base(ERM), Random, BALD, ISAL, JTT-20, and FIS) on three datasets (CelebA, Adult, and Compas) using two fairness metrics (DP and EOp). Each point on the graphs represents the test accuracy and fairness violation of a model trained using the specific algorithm. The vertical dotted line indicates the baseline accuracy achieved by random sampling. The figure demonstrates that FIS generally achieves lower fairness violations while maintaining comparable accuracy compared to other methods.

The figure compares the performance of different fairness-enhancing methods on three benchmark datasets (CelebA, Adult, and Compas). It shows the trade-off between test accuracy and fairness violation (measured by demographic parity and equal opportunity). The results demonstrate that FIS achieves lower fairness violations while maintaining comparable accuracy compared to other baselines.

More on tables

This table presents the performance results of different fairness-aware active learning methods on the Adult dataset, using age as the sensitive attribute. For each method, it shows the average test accuracy and the fairness violation measured by three different metrics: Demographic Parity (DP), Equality of Opportunity (EOp), and Equalized Odds (EOd). The results are presented with their standard deviations, showing the performance variability. The table allows for comparison of the accuracy and fairness trade-off achieved by each method.

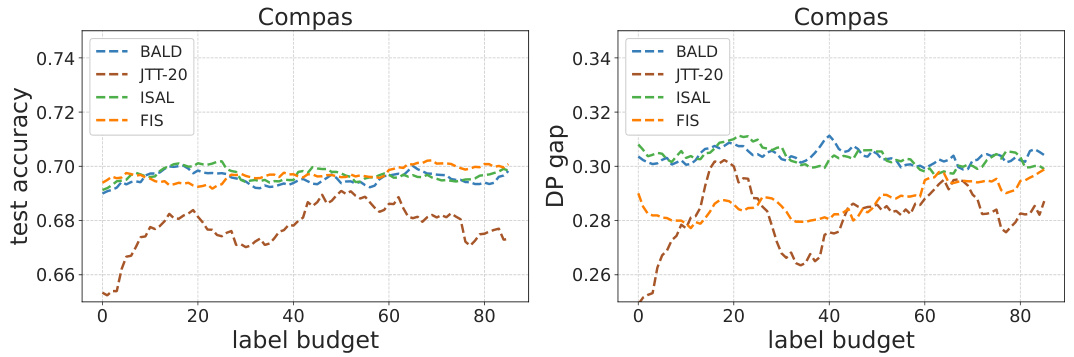

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the Compas dataset using various fairness-aware methods. The table shows the test accuracy and fairness violation (measured using demographic parity (DP), equalized odds (EOp), and equalized odds (EOd)) for each method. The sensitive attribute considered is race. The results are presented as means ± standard deviations across multiple trials to illustrate the variability and statistical significance of the results. This table helps in understanding and comparing the performance of different algorithms in achieving fairness without significantly compromising accuracy.

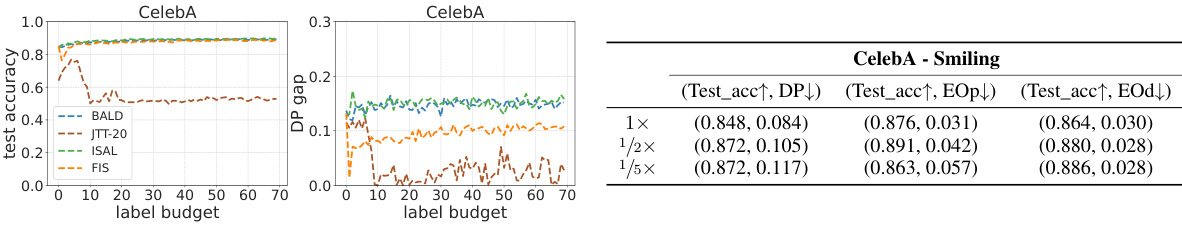

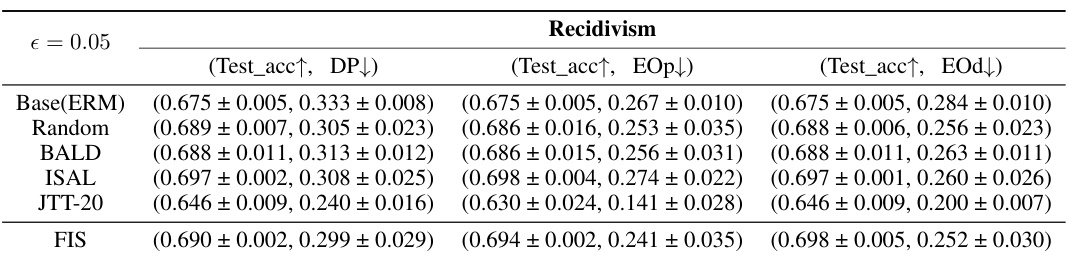

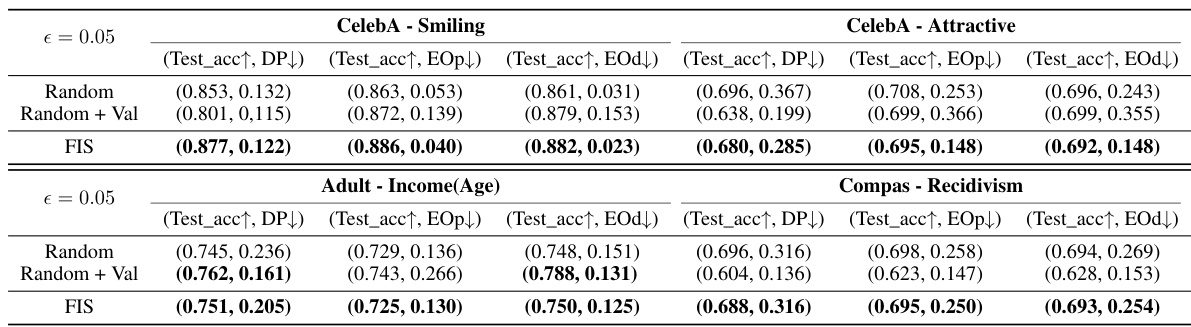

This table presents the test accuracy and fairness violation results for the CelebA dataset under different validation set sizes. It shows the performance of the FIS algorithm (Fair Influential Sampling) when the validation set size is reduced to half (1/2x) and one-fifth (1/5x) of the original size. The results are compared across three different fairness metrics: Demographic Parity (DP), Equality of Opportunity (EOp), and Equalized Odds (EOd), for four different binary classification targets (Smiling, Attractive, Young, and Big Nose). The table demonstrates the robustness of FIS in maintaining accuracy and fairness even with smaller validation sets.

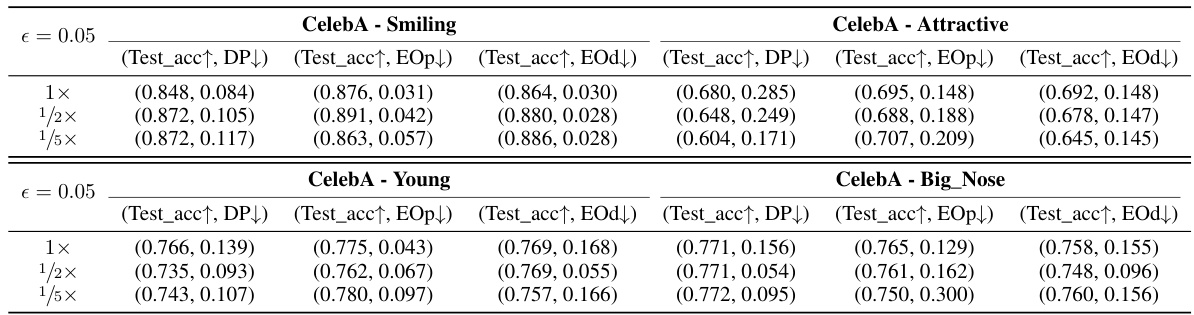

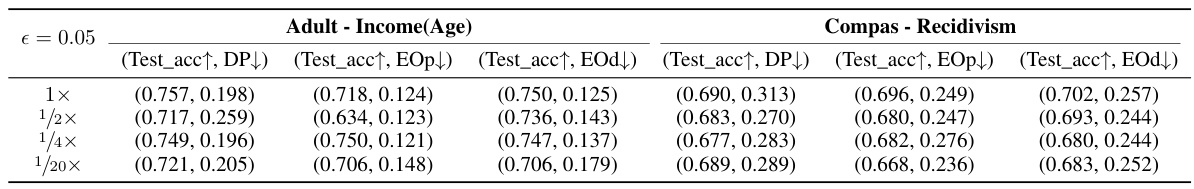

This table presents the results of test accuracy and fairness violation metrics (DP, EOp, EOd) on the Adult and Compas datasets when different sizes of the validation set are used. The validation set size is reduced to 1/2, 1/4, and 1/20 of its original size. This ablation study shows the algorithm’s robustness to changes in the validation set size.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted to assess the impact of reducing the validation set size on the algorithm’s performance. The experiments were performed using two tabular datasets (Adult and Compas) and evaluated using test accuracy and fairness violation metrics, with the validation set size reduced to 1/2x, 1/4x, and 1/20x of its original size. The results show that the algorithm’s performance remains relatively stable even with significant reductions in the validation set size.

Full paper#