↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The Push-Relabel algorithm, while efficient, lacks theoretical understanding of warm-starting, hindering its use with predicted flows. Existing methods for warm-starting other max-flow algorithms do not apply to Push-Relabel, and the effectiveness of heuristics like gap relabeling remain unproven. This limits optimal performance in applications like image segmentation.

This research presents the first theoretical analysis of warm-starting Push-Relabel using a predicted flow. The authors introduce a novel warm-starting algorithm that leverages the gap relabeling heuristic, providing theoretical runtime bounds while maintaining robust worst-case guarantees. Empirical results on image segmentation demonstrate significant runtime improvements, particularly for larger datasets, validating the theoretical findings and the effectiveness of the gap relabeling heuristic in practice.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it provides the first theoretical guarantees for warm-starting the Push-Relabel algorithm, a widely used network flow algorithm. This addresses a significant gap in the literature and offers a new approach to improving efficiency. It also provides a theoretical justification for the widely used gap relabeling heuristic, enhancing our understanding of this popular algorithm. The empirical results demonstrate the practical benefits of this warm-starting technique, especially with larger datasets, opening new avenues for research in algorithm optimization and machine learning applications.

Visual Insights#

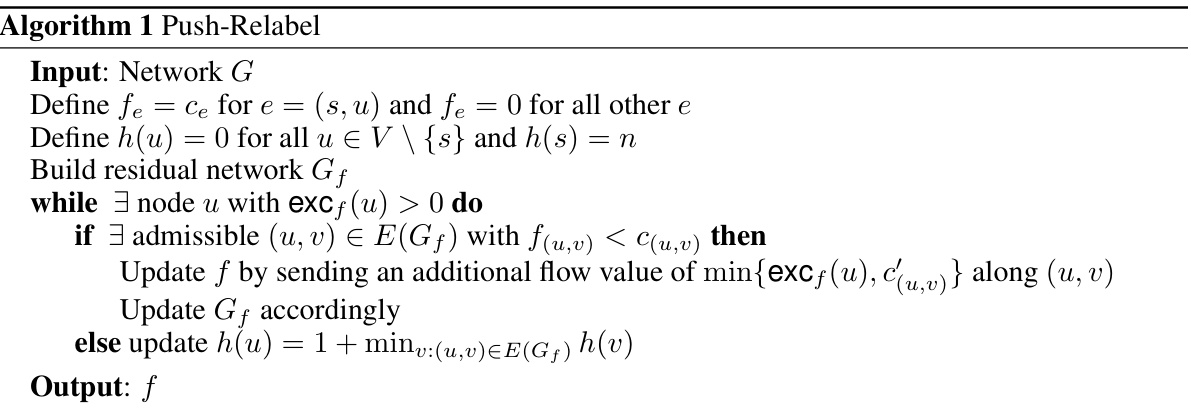

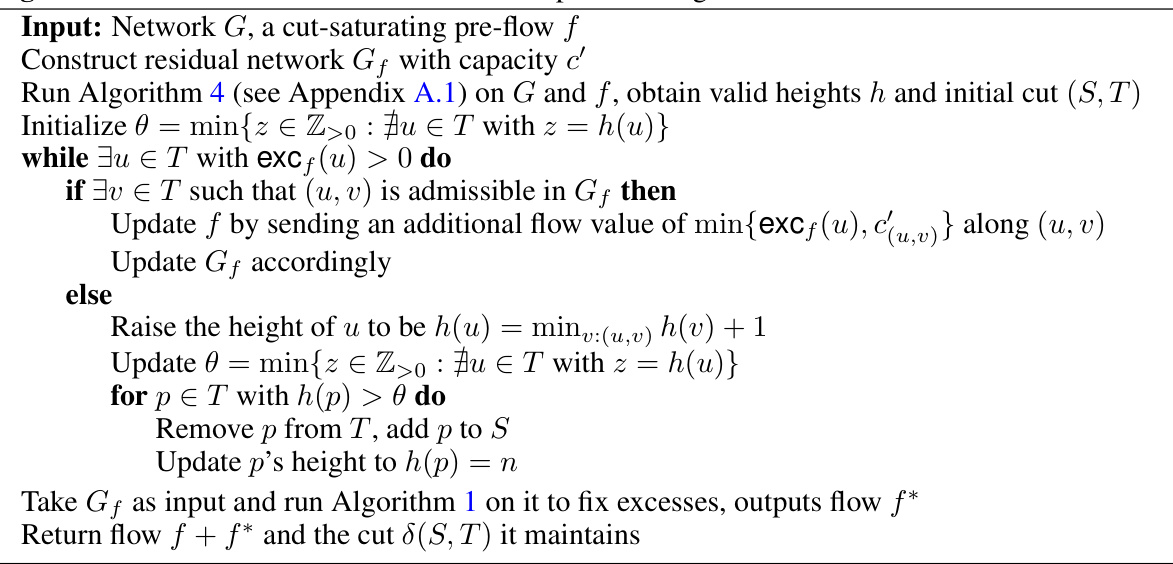

This figure illustrates the phases of the warm-start Push-Relabel algorithm when initialized with a cut-saturating pseudo-flow. Phase 2(a) focuses on resolving excess on the t-side of the cut and adjusting the cut accordingly. Phase 2(b) addresses deficits on the s-side and refines the cut further, leading to the min-cut at the end of this phase. Finally, Phase 3 maintains the min-cut while resolving any remaining excesses or deficits within the s- and t-sides, resulting in both a min-cut and a max-flow at the algorithm’s conclusion.

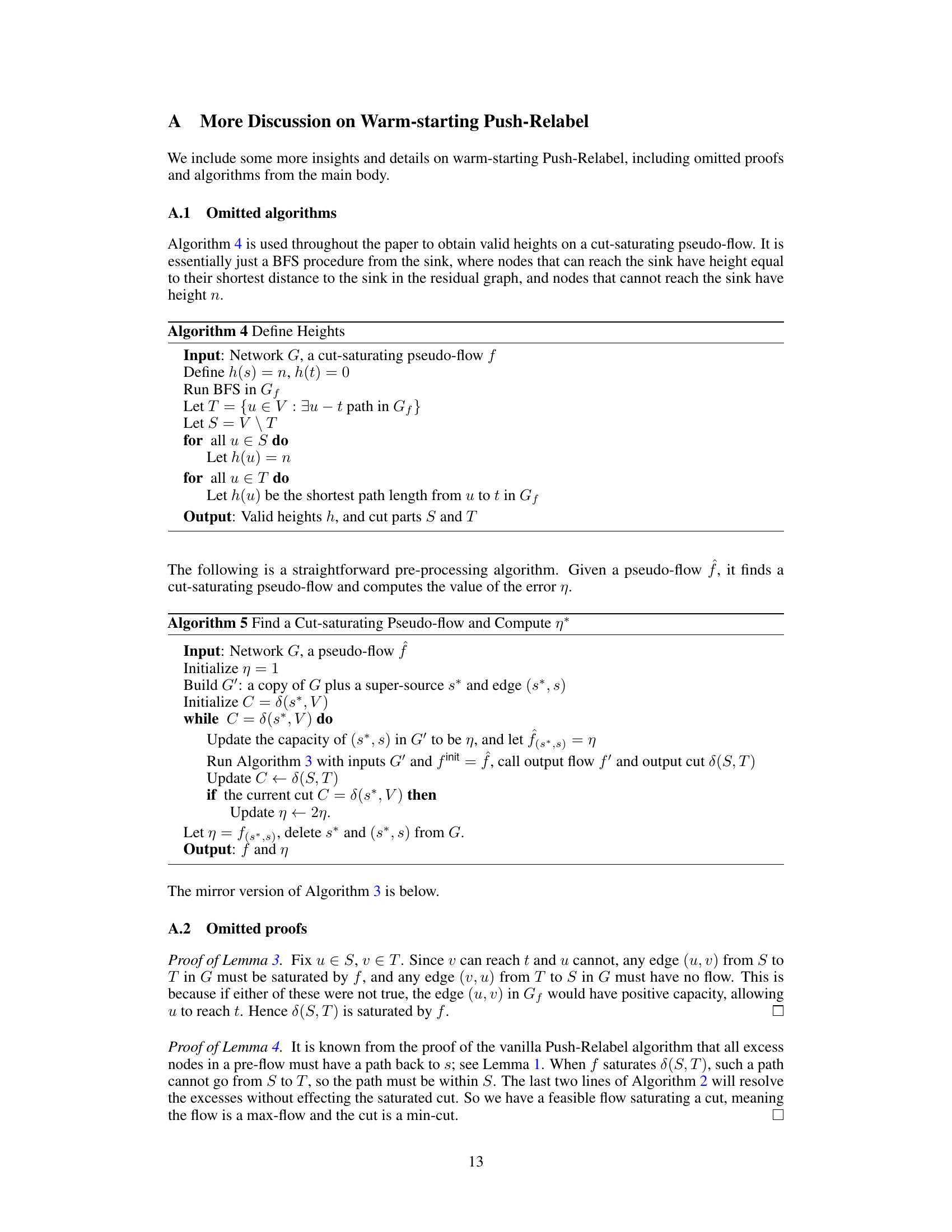

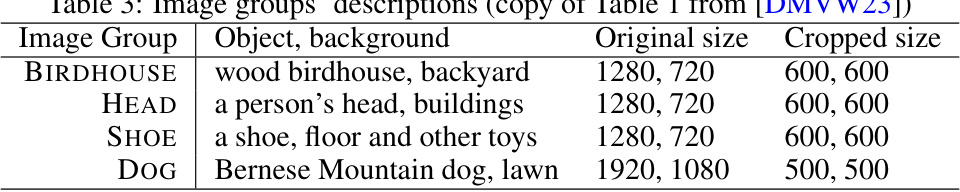

This table presents the average running times in seconds for both Ford-Fulkerson and Push-Relabel algorithms, categorized by whether they were warm-started or not. The results are broken down by image group (BIRDHOUSE, HEAD, SHOE, DOG) and image size (30x30, 60x60, 120x120, 240x240, 480x480 pixels). ‘NA’ indicates that the runtime exceeded one hour.

In-depth insights#

Warm-Start Push-Relabel#

The concept of “Warm-Start Push-Relabel” introduces a novel approach to enhancing the efficiency of the Push-Relabel algorithm, a celebrated method in network flow analysis. Instead of starting from scratch, as in traditional cold-start approaches, warm-start leverages a predicted flow as a starting point. This prediction, ideally close to the optimal flow, accelerates convergence. The research provides the first theoretical guarantees for this warm-starting method. Importantly, it rigorously justifies the use of the gap relabeling heuristic, a practical technique previously lacking formal backing. Theoretical analysis demonstrates improved running times when the predicted flow is accurate, while maintaining robust worst-case guarantees. The practical efficacy is further validated through experiments showcasing faster execution, particularly noticeable with larger datasets. This research makes significant contributions to both theory and practice in network flow optimization by providing a theoretically sound warm-starting procedure and offering a new lens for understanding existing heuristics. The outcomes suggest a paradigm shift in how we approach computationally demanding flow problems, opening new avenues for improvement and potentially impacting various fields that rely on efficient network flow solutions.

Gap Relabeling Heuristic#

The gap relabeling heuristic, employed in Push-Relabel algorithms, addresses the challenge of height updates by efficiently managing node heights. It identifies gaps in the height distribution, where no nodes exist at a particular height. When such a gap is found, nodes with heights between the gap and the maximum height are relabeled to the maximum height. This action effectively reduces the number of nodes at lower heights, leading to a faster convergence as the algorithm progresses toward finding a maximum flow. Although empirically successful, this heuristic’s effectiveness lacked rigorous theoretical justification until recently. The analysis of warm-started Push-Relabel provides the first theoretical guarantees for gap relabeling’s performance improvement by showing its direct impact on maintaining a cut with monotonically decreasing t-side nodes. This theoretical foundation validates the practical efficiency observed with the gap relabeling heuristic, connecting empirical improvements to core algorithmic properties.

Image Segmentation#

The research paper employs image segmentation as a practical application to validate its theoretical contributions on warm-starting Push-Relabel algorithms. Image segmentation is framed as a max-flow/min-cut problem, leveraging the efficiency of Push-Relabel for improved performance. The experimental design mirrors previous work using real-world image datasets, allowing for a direct comparison of cold-start and warm-start approaches. Results demonstrate significant speed improvements with warm-starting on larger images, showcasing the algorithm’s practicality. This application is particularly relevant given Push-Relabel’s strong theoretical guarantees and empirical performance, establishing it as a suitable method for large-scale image analysis. However, the study acknowledges that implementation details, like predicting cut-saturating flows, are crucial for efficiency. The experiments highlight the interplay between theoretical advancements and practical implementations, suggesting that the improved theoretical understanding translates to real-world benefits for image segmentation tasks.

Theoretical Analysis#

A robust theoretical analysis is crucial for validating the effectiveness and efficiency of any algorithm. In the context of this research paper, a strong theoretical foundation would involve rigorously proving the algorithm’s correctness, analyzing its time and space complexity under various conditions, and establishing its performance guarantees. Specifically, the analysis should establish bounds on the running time of the warm-started Push-Relabel algorithm, demonstrating its speedup compared to traditional methods, especially when the initial prediction flow is close to the optimal solution. Furthermore, it is essential to clarify any assumptions made during the theoretical analysis and discuss their implications and limitations. A clear analysis of the algorithm’s behavior under different error conditions for the input prediction is also critical. A thorough analysis should not just provide upper bounds, but also attempt to establish lower bounds or explore average-case scenarios to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the algorithm’s performance. Finally, a robust analysis should demonstrate the algorithm’s efficiency and stability even with imperfect predicted flows, proving its resilience to real-world scenarios with noisy data.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the warm-starting approach to more complex network flow problems beyond the maximum flow problem, such as minimum-cost flow or multi-commodity flow. A deeper investigation into the theoretical underpinnings of heuristics like gap relabeling is warranted to better understand their success in practice and potentially lead to further algorithmic improvements. The efficacy of warm-starting with various prediction methods and error metrics warrants further investigation. Exploring different prediction models and incorporating advanced machine learning techniques to generate more accurate predictions could significantly improve efficiency. Additionally, developing a robust theoretical framework that comprehensively addresses the complexity of warm-starting non-augmenting path algorithms would be a valuable contribution. Finally, extensive empirical studies across diverse problem domains and network structures are needed to establish the general applicability and scalability of warm-started Push-Relabel. Further research should also explore practical implications and the impact of different warm-starting strategies on real-world applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the warm-start Push-Relabel algorithm seeded with a cut-saturating pseudo-flow. It shows the algorithm’s progress through several phases: resolving excess on the t-side, moving the cut, resolving deficits on the s-side, and finally maintaining the cut while fixing excess/deficit within the s- and t-sides. The red curve represents the cut, black arrows show existing flows, and red arrows indicate flows added in each phase.

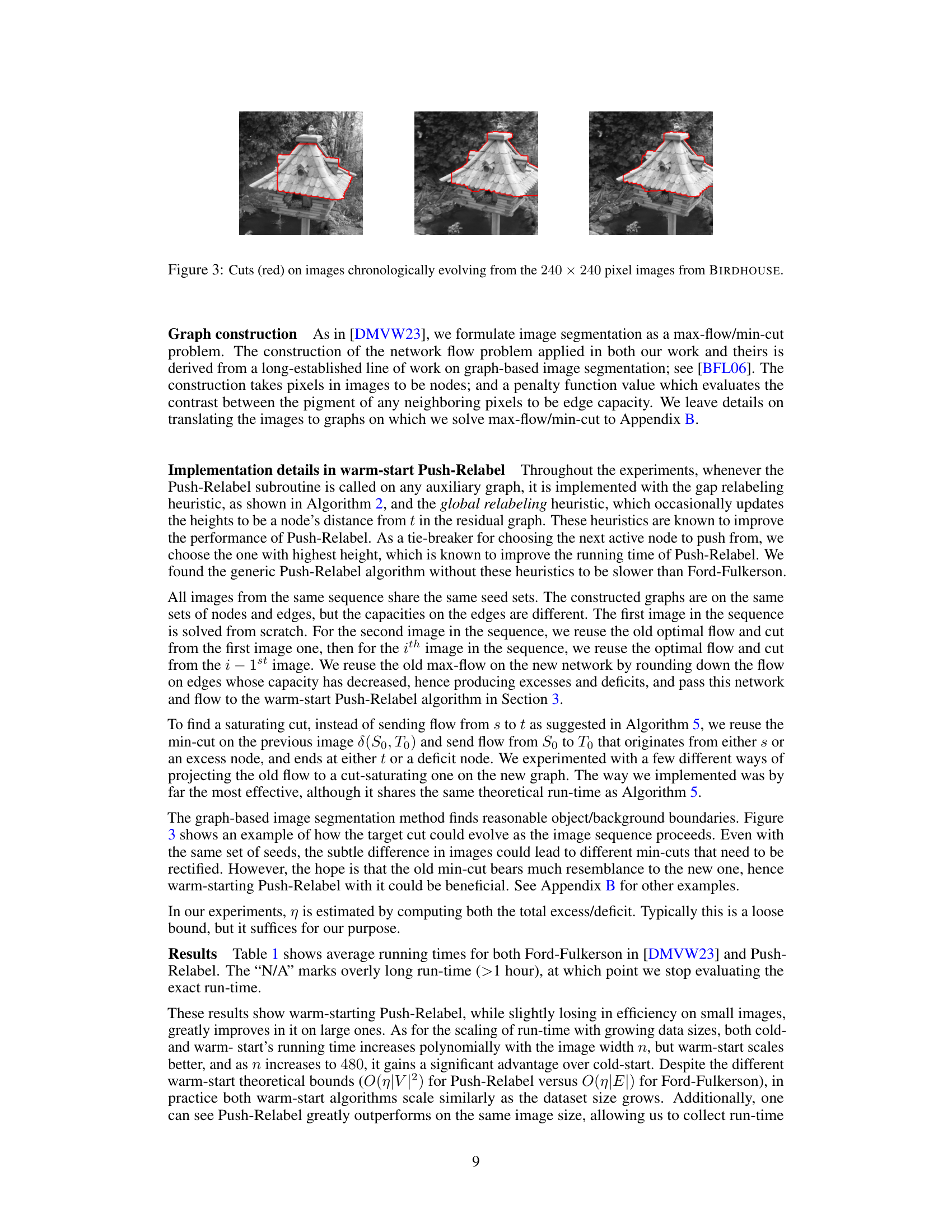

This figure shows how the algorithm’s identified cuts change over a sequence of three images depicting a birdhouse. The red lines represent the cuts produced by the warm-start Push-Relabel algorithm, demonstrating the algorithm’s ability to adapt to small changes in image data while maintaining efficiency.

This figure illustrates the warm-start Push-Relabel algorithm’s phases when initialized with a cut-saturating pseudo-flow. It visually shows how the algorithm iteratively modifies the flow and the cut (represented by the red curve) to resolve excess and deficits, ultimately reaching the minimum cut and maximum flow. The black arrows represent the initial flow, while the red arrows depict the adjustments made in each phase.

This figure shows three images from the DOG image sequence. Each image has a red outline indicating the cut found by the warm-start Push-Relabel algorithm. The images are chronologically ordered, demonstrating how the cut changes slightly between consecutive images in the sequence. This illustrates the algorithm’s ability to adapt to minor variations in the image while still efficiently finding a minimum cut.

This figure shows the results of the image segmentation task using the warm-start Push-Relabel algorithm. The images are from the HEAD group, which shows a person’s head against a background. The red lines represent the cuts found by the algorithm as the image sequence evolves. The slight variations in the images from frame to frame demonstrates that the algorithm can adapt to these small changes and still produce reasonable segmentations. The progression of the cuts visually shows the algorithm’s operation on a sequence of images.

This figure shows three images from the BIRDHOUSE image sequence. The images are chronologically ordered. A red curve is overlaid on each image, representing the min-cut found by the warm-started Push-Relabel algorithm. The slight variations between consecutive images demonstrate how the algorithm adapts to changes in the scene while maintaining efficiency. The red curve denotes the boundary between the object (birdhouse) and the background.

More on tables

This table presents the average running times in seconds for both cold-start and warm-start versions of the Ford-Fulkerson and Push-Relabel algorithms on four different image datasets (BIRDHOUSE, HEAD, SHOE, DOG). Each dataset is tested with different image resolutions (30x30, 60x60, 120x120, 240x240, 480x480 pixels). The results show the running times for each algorithm and its warm-started version. Note that ‘NA’ indicates that the running time exceeded one hour.

This table presents the average running times in seconds for both Ford-Fulkerson and Push-Relabel algorithms, with and without warm-starting, on various image datasets of different sizes. The image datasets are categorized into four groups: BIRDHOUSE, HEAD, SHOE, and DOG. Each group contains images with resolutions ranging from 30x30 to 480x480 pixels. The table shows that warm-starting Push-Relabel significantly improves performance for larger images.

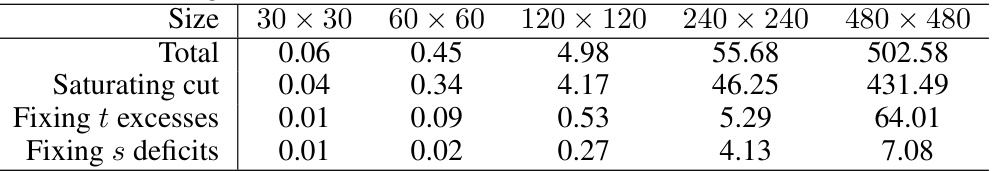

This table breaks down the running time of the warm-start Push-Relabel algorithm into three phases: 1) finding a cut-saturating pseudo-flow; 2) fixing excess on the t-side; and 3) fixing deficits on the s-side. The table shows the average time (in seconds) spent in each phase for different image sizes (30x30, 60x60, 120x120, 240x240, and 480x480 pixels) from the BIRDHOUSE image dataset. It demonstrates how the time spent in each phase changes as the image size increases.

The table presents the average running times in seconds for both Ford-Fulkerson and Push-Relabel algorithms on four different image groups (BIRDHOUSE, HEAD, SHOE, DOG) with varying image resolutions (30x30, 60x60, 120x120, 240x240, 480x480 pixels). It compares the performance of both algorithms when warm-started (using a prediction of the flow) against their cold-started counterparts. The results show that while the warm-started versions might be slightly slower than the cold-started counterparts on small images, they demonstrate a significant performance gain as the image size increases. Note that ‘NA’ indicates runtimes exceeding one hour.

This table presents the average running times in seconds for both Ford-Fulkerson and Push-Relabel algorithms, comparing their cold-start and warm-start versions across different image datasets and resolutions. The image datasets (BIRDHOUSE, HEAD, SHOE, DOG) are categorized by image size (30x30 to 480x480 pixels). The results show the running time for both cold-start and warm-start versions of each algorithm, allowing for comparison between the two algorithms’ performance and efficiency with warm-starting.

Full paper#