↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many cognitive processes occur at a macroscopic level, characterized by emergent properties – where the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Identifying these macroscopic variables is crucial for understanding complex systems, but traditional methods rely on intuition and expert knowledge, which are often subjective and lack scalability. This poses a significant challenge in fields like neuroscience, where understanding brain activity requires identifying meaningful macroscopic variables.

This paper introduces a new data-driven method to overcome this limitation. The method uses recent advancements in representation learning and differentiable information estimators to learn macroscopic variables that exhibit emergent behavior. It leverages a differentiable architecture to maximize causal emergence, a measure that quantifies the unique predictive information held by a macroscopic variable. The researchers demonstrate the method’s effectiveness on both synthetic and real-world brain activity data, showcasing its ability to extract a diverse set of emergent features and highlighting the importance of causal emergence for accelerating feature learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it presents a novel, data-driven method for identifying emergent variables in time-series data. This is particularly relevant to researchers studying complex systems such as the brain, where identifying relevant macroscopic variables is often challenging. The proposed method offers a significant advancement over traditional intuition-based approaches, which can be subjective and lack scalability. This work opens new avenues for investigating the structure of cognitive representations in biological and artificial intelligence systems.

Visual Insights#

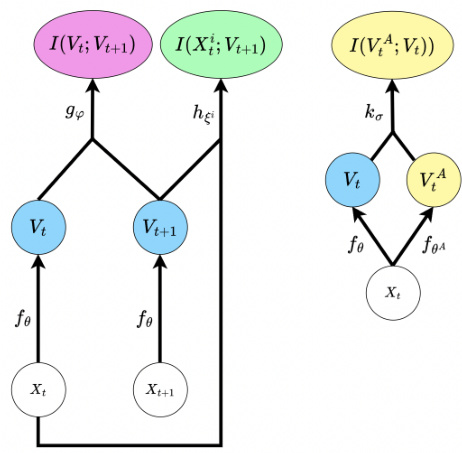

This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed model for learning causally emergent representations. The model consists of a representation network (fθ) that learns a feature (Vt) from the input data (Xt). The feature Vt is trained to maximize an objective function (Ψ) that consists of predictive mutual information (I(Vt; Vt+1), estimated by gφ) and marginal mutual information terms (I(Xi; Vt+1), estimated by hξi). An optional critic (kσ) is included to encourage diversity in the learned emergent features by estimating the mutual information between multiple emergent features (I(VA; Vt)).

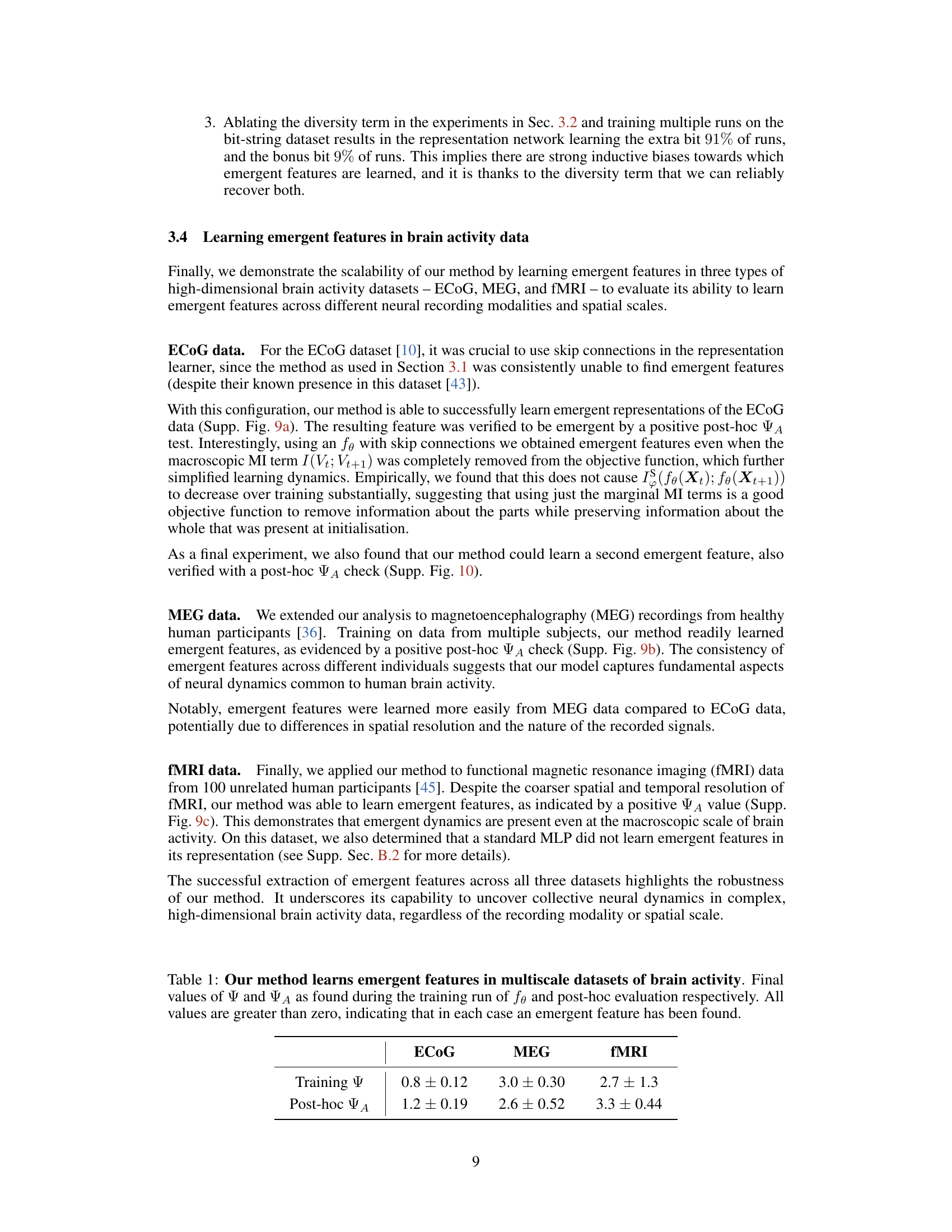

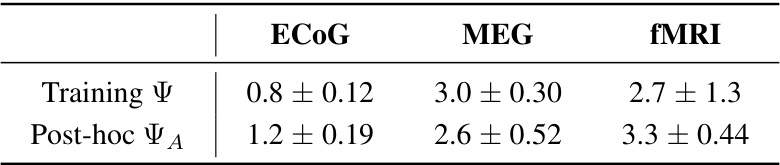

This table summarizes the results of applying the proposed method to three different brain activity datasets: ECOG, MEG, and fMRI. For each dataset, it reports the values of two metrics calculated during the model training and post-hoc testing: the training emergence metric (Ψ) and the adjusted emergence metric (ΨA). The post-hoc values are calculated after the model training is complete, providing further confirmation that emergent features were found. The table demonstrates the method’s ability to detect emergent features across various neuroimaging modalities and scales.

In-depth insights#

Emergence Detection#

Emergence detection in complex systems, particularly from time-series data, presents a significant challenge. Many approaches exist, but they often suffer from limitations such as reliance on pre-defined macroscopic variables or high computational cost. Information-theoretic methods offer a powerful, data-driven approach, leveraging measures of information like mutual information and partial information decomposition (PID) to quantify unique information contained in macroscopic variables not reducible to their microscopic constituents. This allows for the identification of emergent properties without the need for pre-defined variables. However, challenges remain. Estimating information measures accurately in high-dimensional systems can be computationally expensive and prone to error. Furthermore, developing robust and scalable algorithms that are suitable for diverse real-world datasets is crucial. Future research should explore improved information estimators, efficient methods for handling high-dimensional data, and better understanding of how to integrate these methods with representation learning techniques to automatically discover relevant macroscopic variables, ultimately leading to a more comprehensive and automated understanding of emergence in complex systems.

Info-Theoretic Metrics#

Info-theoretic metrics offer a powerful lens for analyzing complex systems by quantifying information flow and dependencies. Mutual information, for example, measures the statistical dependence between variables, providing insights into their relationships beyond simple correlations. Transfer entropy extends this by specifically quantifying the directional flow of information between time series, revealing causal relationships. Applying these metrics to emergent phenomena allows for the objective assessment of emergence by measuring the information content unique to macroscopic variables, rather than just their constituent parts. This approach avoids subjective interpretations and enables a rigorous evaluation of whether system-level behavior truly exceeds the sum of its components. The challenge lies in developing efficient and scalable methods for estimating information-theoretic quantities in high-dimensional datasets, along with robust criteria for identifying true emergence versus spurious correlations. The choice of metric also depends on the specific aspect of emergence being investigated and the nature of the data.

Diverse Emergence#

The concept of “Diverse Emergence” suggests systems exhibiting multiple emergent properties simultaneously, each arising from different underlying interactions. This contrasts with simpler notions of emergence where a single, overarching macroscopic variable dominates. A key challenge in studying diverse emergence is the identification of these distinct emergent properties within complex datasets. The ability to successfully disentangle and analyze these multiple features is critical for understanding the hierarchical organization of information in complex systems. Methods employing information-theoretic measures and representation learning techniques can potentially be leveraged to address this challenge. Further research is needed to develop robust and scalable methods to uncover these diverse emergent patterns, potentially opening new avenues for studying complex systems in various fields, such as neuroscience and artificial intelligence.

Brain Data Analysis#

Analyzing brain data presents unique challenges due to its high dimensionality, complexity, and noise. This necessitates sophisticated methods to extract meaningful insights. The paper likely explores various techniques, such as dimensionality reduction, to handle the massive number of variables. Machine learning approaches, especially deep learning models, are probably employed to identify patterns and relationships in neural activity. Preprocessing steps, including artifact removal and signal normalization, are critical to ensure data quality. Different brain imaging modalities (e.g., EEG, MEG, fMRI) each require tailored analysis methods. The success of the analysis hinges on careful consideration of the specific research question, choice of appropriate analytical techniques, and robust validation strategies. Interpretability is another crucial factor. The methods applied should ideally provide clear and understandable insights into the neural processes under investigation, even with complex models. Therefore, model selection should be data-driven and incorporate evaluation metrics that balance predictive accuracy and interpretability.

Future Directions#

The paper’s “Future Directions” section would ideally explore several key areas. Improving training stability is crucial; the adversarial nature of the learning process necessitates robust techniques to prevent unstable dynamics. Investigating alternative differentiable mutual information estimators beyond SMILE, potentially those addressing the limitations of high variance or redundancy, is vital. Extending the methodology to different types of data beyond those considered (ECOG, MEG, fMRI) such as time series from other biological systems or complex simulations, could reveal broader applicability. The paper mentions the possibility of combining the proposed method with other representation learning methods – thorough experimentation in this area, alongside a theoretical analysis of their combined capabilities, would greatly enhance the impact. Finally, a deeper exploration of the relationship between unique information and emergence as quantified by Ψ is warranted, as this relationship is currently limited to a sufficient condition, leaving open the possibility of emergence even when Ψ is not positive.

More visual insights#

More on figures

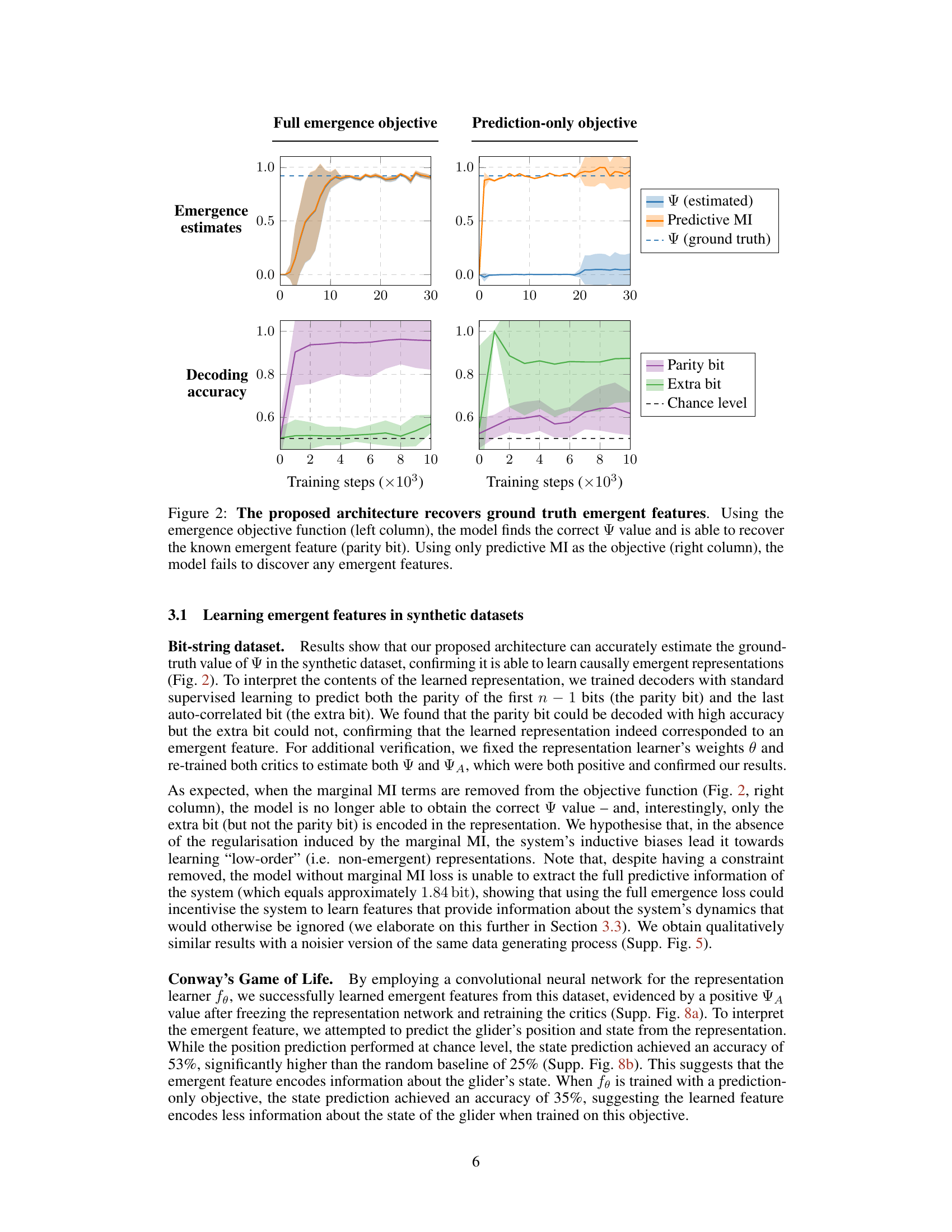

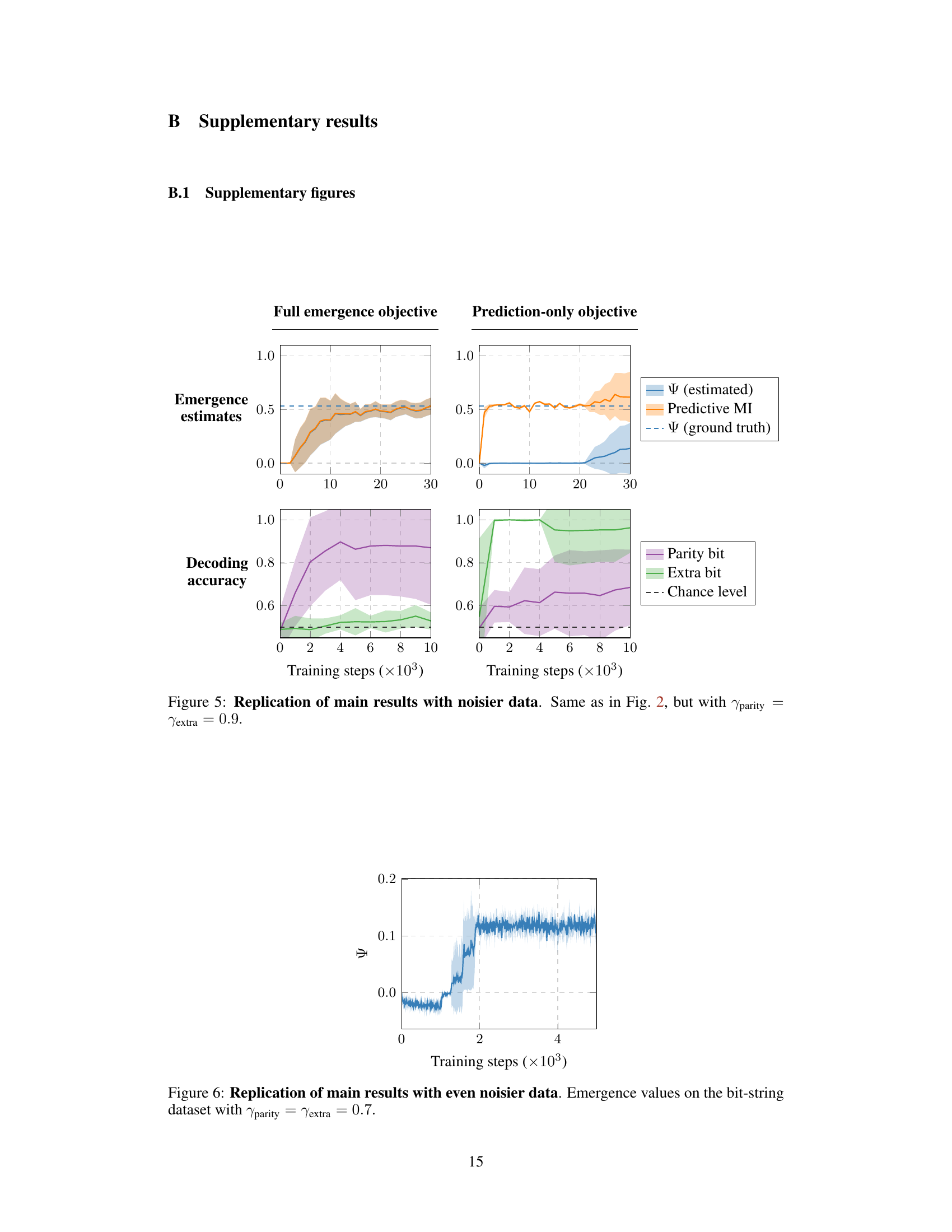

This figure shows the results of training a model to learn emergent features in a synthetic dataset. The left column shows the results when the model is trained using the full emergence objective function, which includes both predictive and marginal mutual information terms. In this case, the model successfully recovers the ground truth emergence value and is able to identify the known emergent feature (the parity bit). The right column shows the results when the model is trained using only the predictive mutual information term. In this case, the model fails to discover any emergent features. This demonstrates the importance of including marginal mutual information terms in the objective function for learning emergent representations.

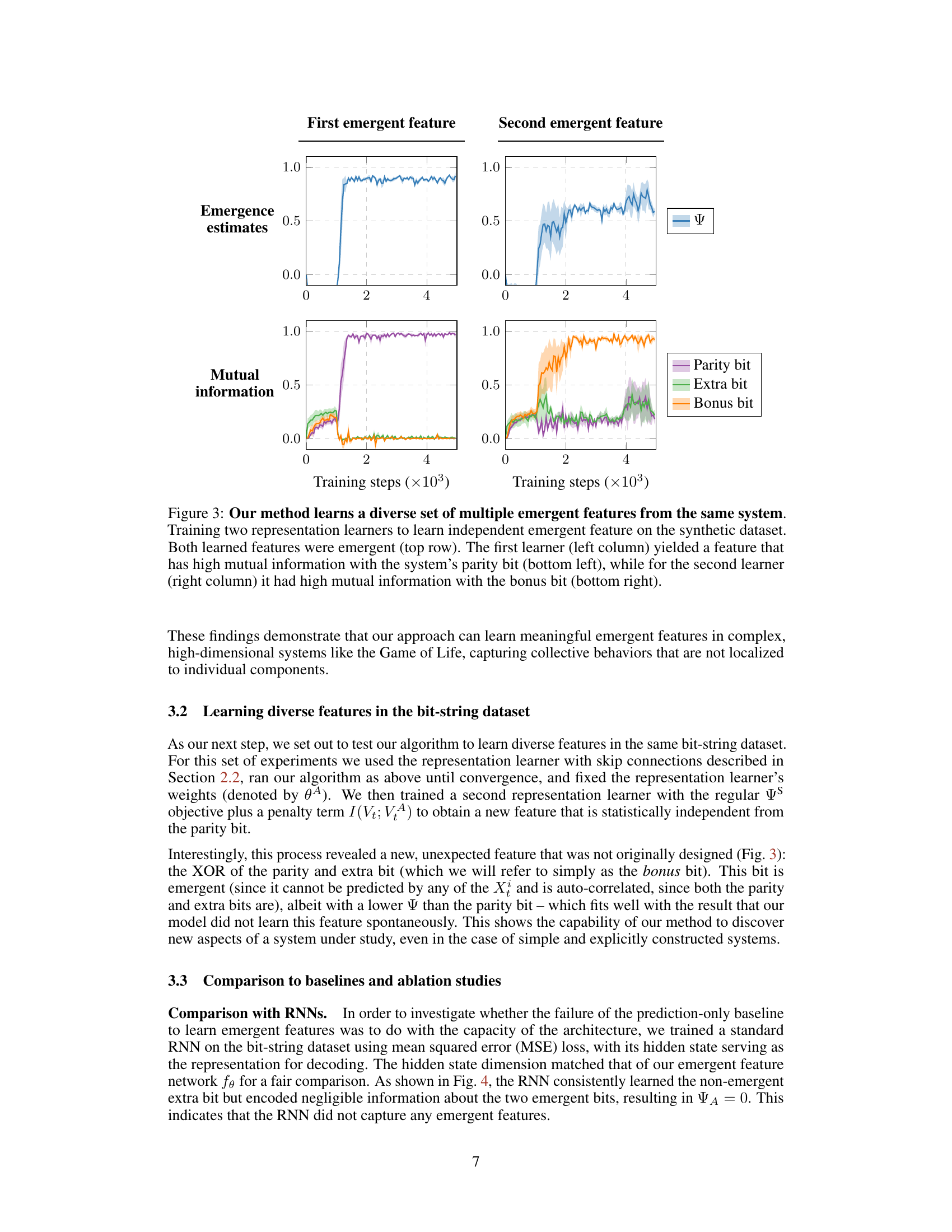

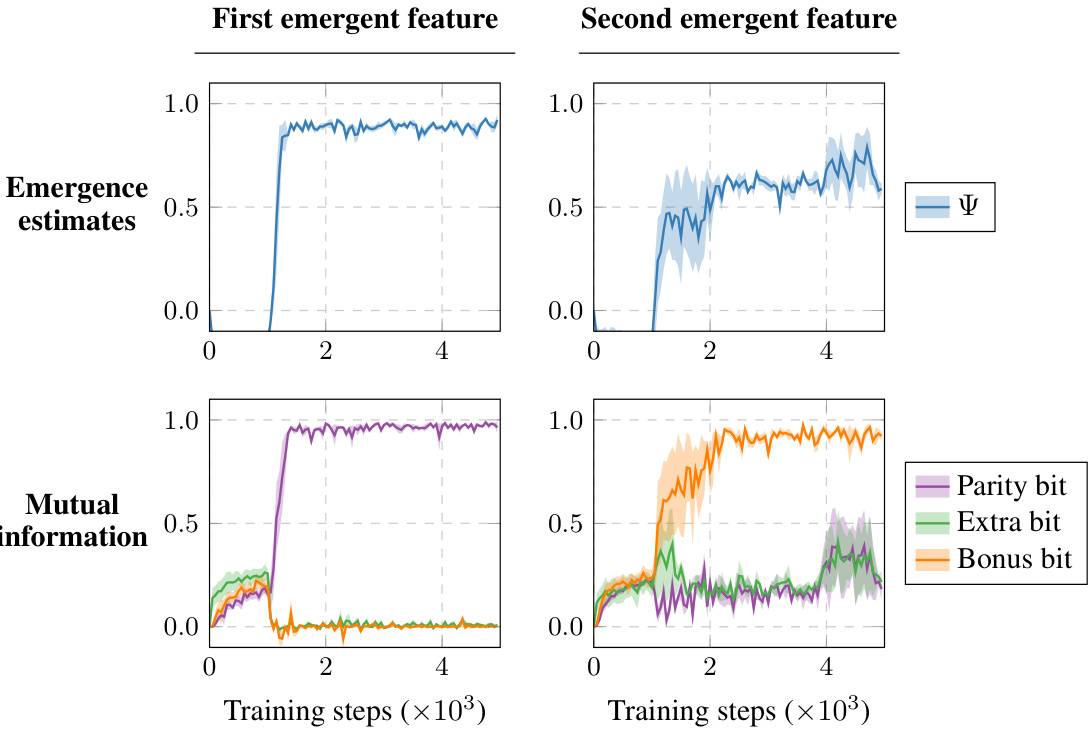

This figure demonstrates the ability of the proposed method to learn multiple independent emergent features from the same system. Two separate representation learners were trained on a synthetic bit-string dataset, each aiming to maximize emergence. The top row shows the emergence estimates over training steps for each learner, indicating successful identification of emergent features. The bottom row shows the mutual information between the learned features and the ground truth features (parity bit and bonus bit). The results confirm that the two learners identified different, independent emergent features, one strongly correlated with the parity and the other with the bonus bit.

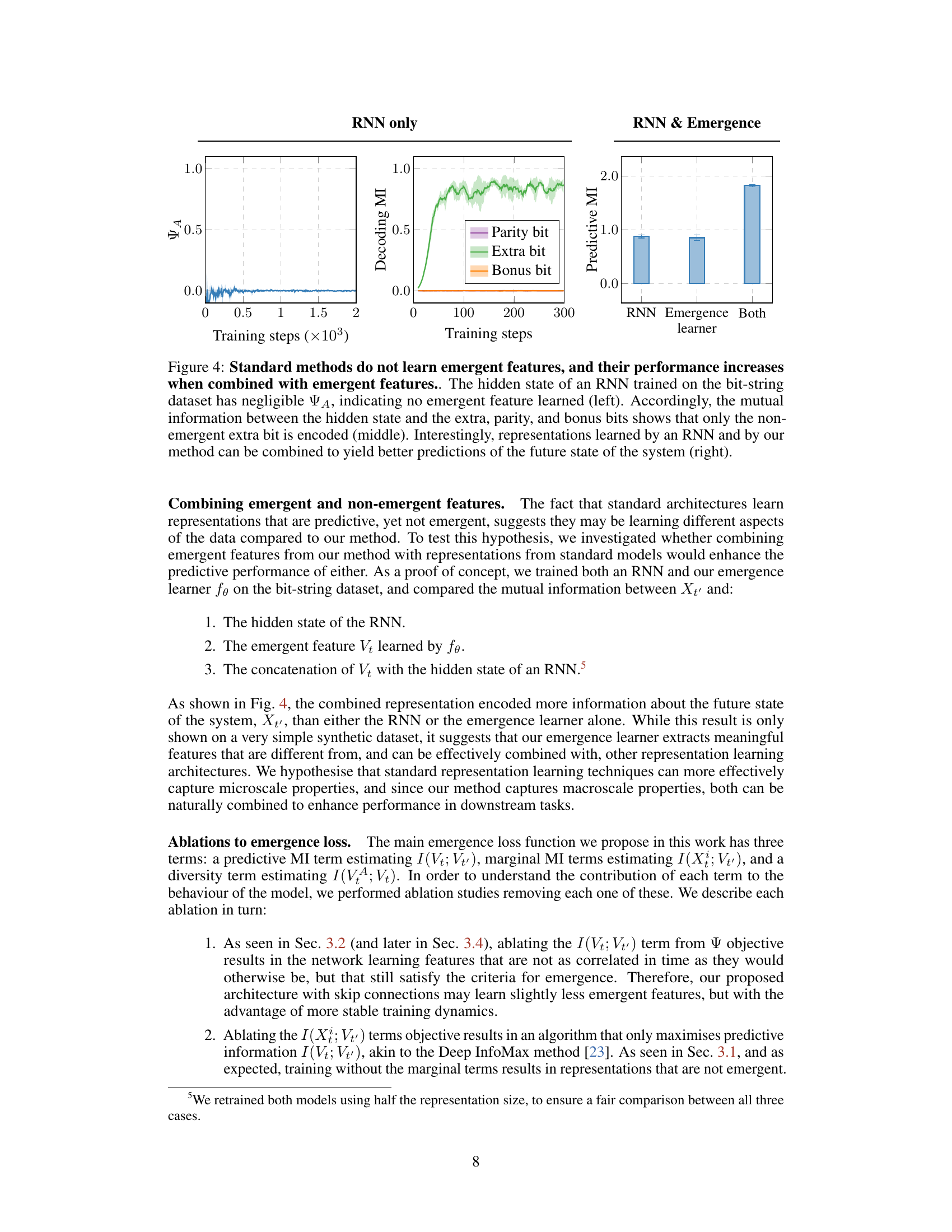

This figure shows a comparison between the performance of a standard RNN, the proposed emergence learning method, and a combination of both in learning emergent features from a synthetic dataset. The left panel shows that the RNN fails to capture emergent features. The middle panel shows that the RNN mainly encodes non-emergent information. The right panel shows that combining the RNN and the emergence learner improves prediction performance.

This figure shows the results of training a model to learn emergent features from synthetic data. The left column demonstrates that using the full emergence objective function successfully leads to the model recovering the ground truth emergence value (Ψ) and identifying the known emergent feature (parity bit). The right column shows that when using only the predictive mutual information (MI) as the objective, the model fails to discover any emergent features, highlighting the importance of the full emergence objective for identifying emergent properties.

This figure shows the results of training a model to learn emergent features from a synthetic dataset. The left column shows the results when the model is trained to maximize emergence using the proposed method. The model successfully identifies the ground truth value of emergence (Ψ) and recovers the known emergent feature (parity bit). In contrast, the right column displays the results obtained when the model is trained only to maximize predictive mutual information. In this case, the model fails to identify any emergent features.

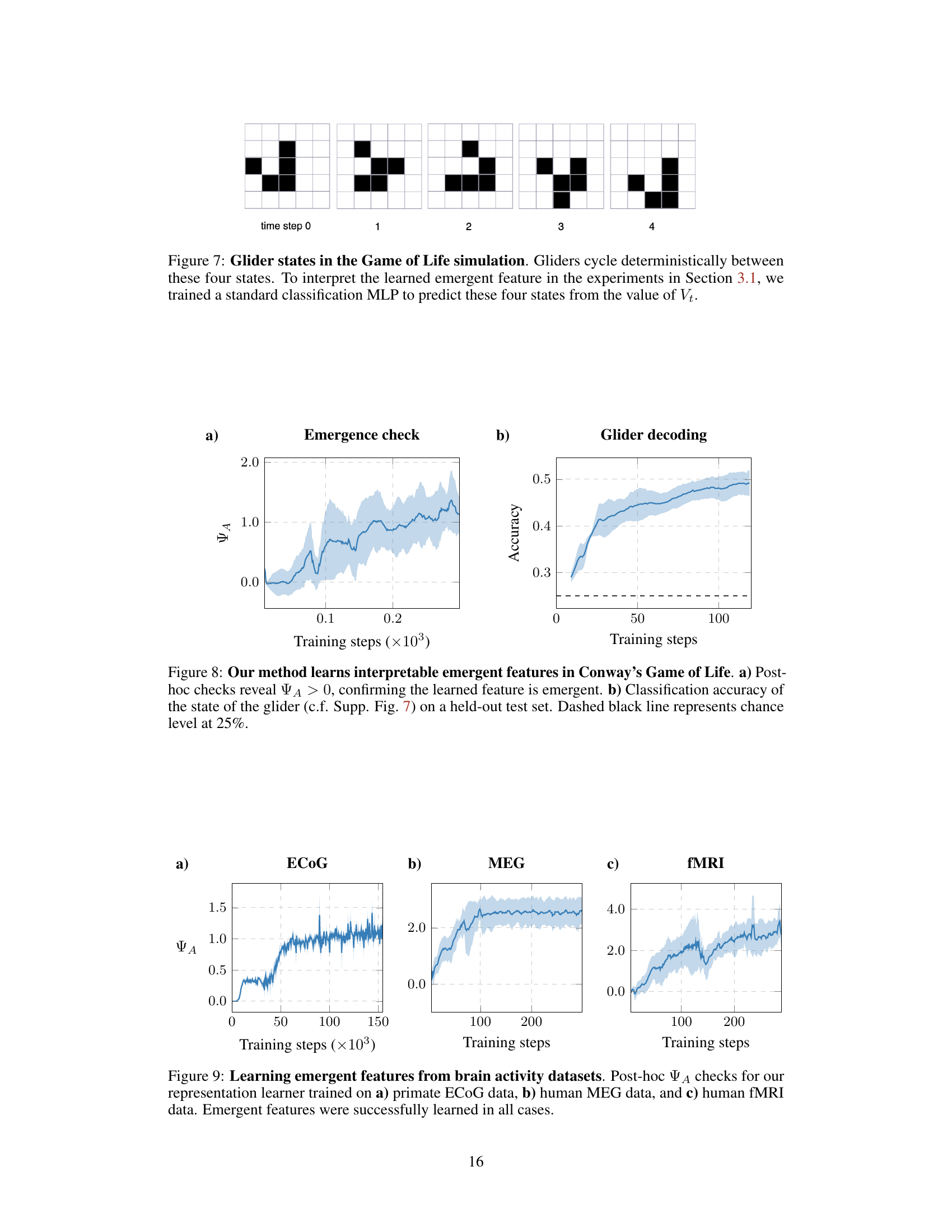

This figure shows the four states of a glider in Conway’s Game of Life. A glider is a specific pattern of cells that moves across the grid. To understand the emergent features learned by the model, a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) classifier was trained to predict these four states based on the learned representation Vt. This helps to interpret the meaning of the learned features in the context of the Game of Life.

This figure shows the results of applying the proposed method to Conway’s Game of Life. Panel (a) demonstrates that the learned feature is indeed emergent by showing a positive value for the adjusted emergence metric (ΨA) after training. Panel (b) shows the accuracy of a classifier trained to predict the state of the glider based on the learned feature. The high accuracy, exceeding the chance level, suggests that the learned feature captures relevant information about the glider’s state.

This figure shows the results of applying the proposed method to three different real-world brain activity datasets: primate electrocorticography (ECOG), human magnetoencephalography (MEG), and human functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). For each dataset, the emergence metric (ΨA) is plotted against training steps. The shaded area represents the standard deviation across multiple runs. The results indicate that the method successfully identifies emergent features across different brain recording modalities and spatial scales.

This figure shows the results of training two representation learners to learn independent emergent features from the same ECOG dataset. The top panel (a) shows the emergence values (ΨA) for both learners, confirming that both features are indeed emergent. The bottom panel (b) displays the mutual information (I(Vt; VA)) between the two features over time, showing that they are statistically independent, further supporting the idea that the model has successfully learned diverse emergent features.

More on tables

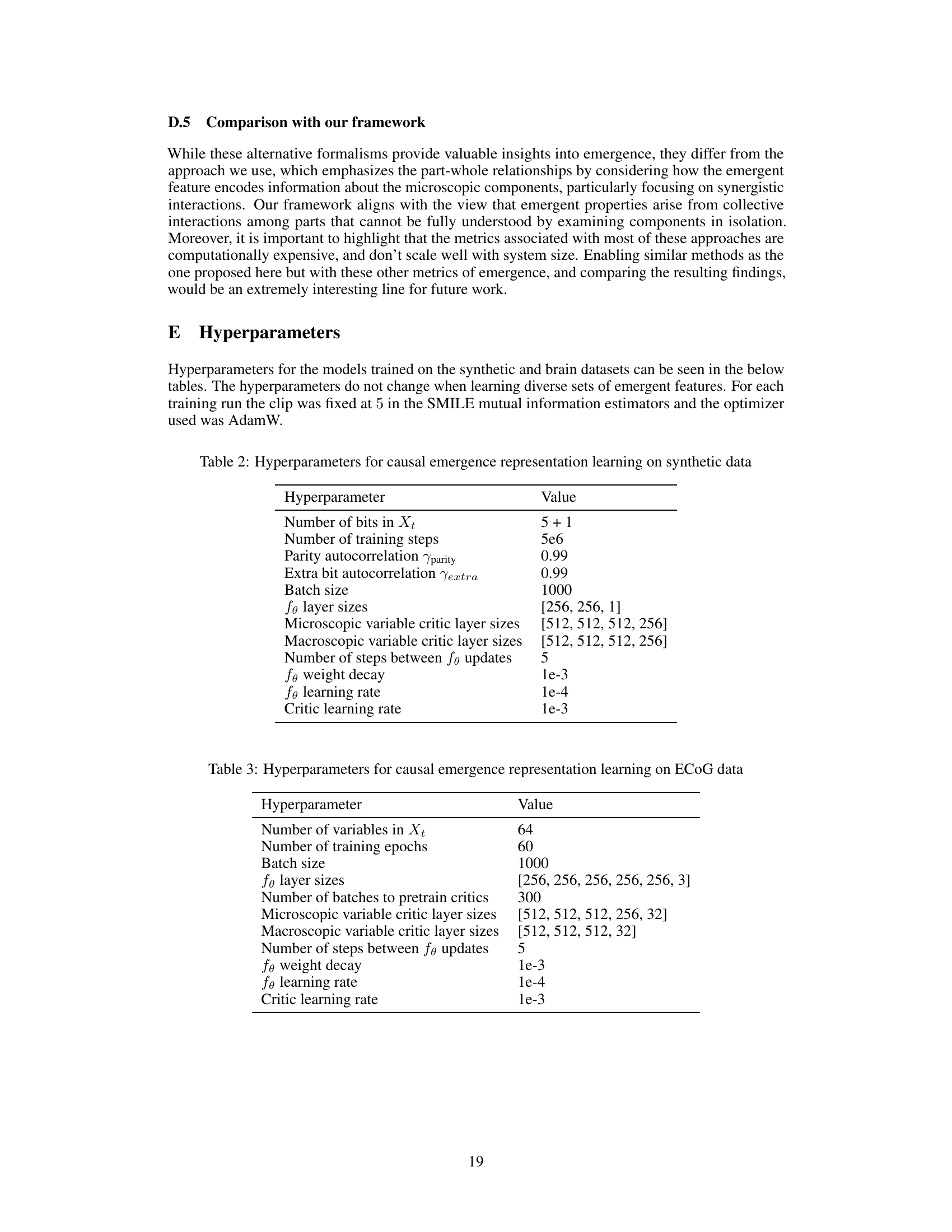

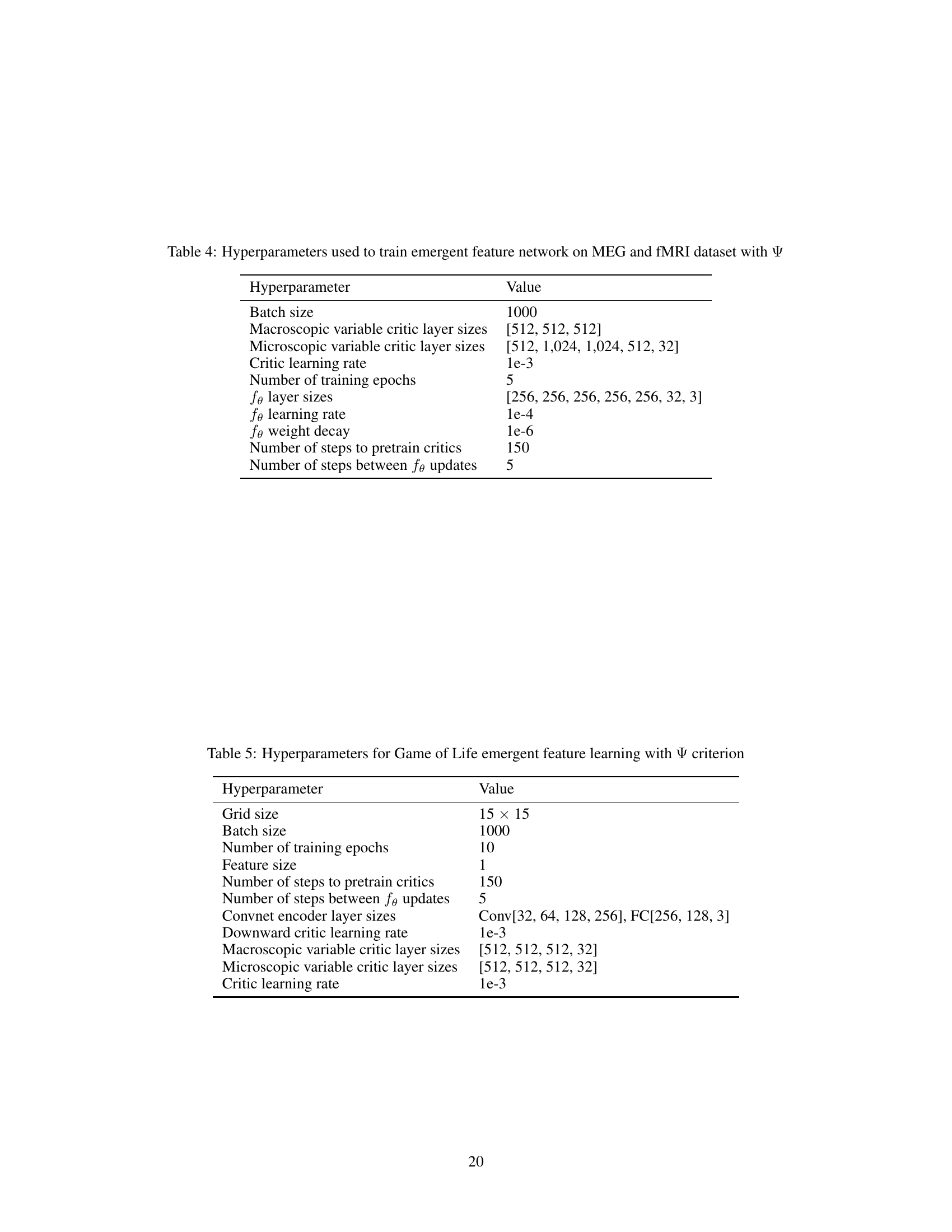

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the causal emergence representation learning experiments on synthetic data. It includes parameters for the network architecture (number of layers, sizes of layers), training process (batch size, learning rates, weight decay), and the data generation process (autocorrelation parameters for the parity and extra bits). These hyperparameters were chosen to balance the trade-off between model complexity and training efficiency, leading to the best results on the synthetic data.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the emergent feature network on MEG and fMRI datasets using the Ψ criterion. It includes parameters such as batch size, the architecture of the representation network (fθ) and critics, the learning rates for the different components of the model, and the number of training steps, highlighting the settings for optimizing the emergence objective function.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the emergent feature network on MEG and fMRI datasets using the Ψ criterion. It includes parameters for batch size, critic layer sizes, learning rates, number of training epochs, fe layer sizes, fe learning rate, fe weight decay, number of steps to pretrain critics and number of steps between updates. These parameters were set to optimize the model’s performance and stability in learning emergent features from the high-dimensional brain activity data.

This table lists the hyperparameters used to train the model for learning emergent features in the Conway’s Game of Life dataset. It includes settings for the grid size, batch size, number of training epochs, feature size, the number of steps used for pretraining the critics, and the number of steps between updates for the representation learning network. Layer sizes are specified for both the convolutional encoder and the critics, along with learning rates for both the encoder and critic networks.

Full paper#