↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) struggle with the extrapolation problem; their performance drastically drops when input length surpasses training limits. Existing solutions like increasing training data or using sophisticated positional encodings (PE) are resource-intensive and time-consuming. This paper explores the limitations of existing approaches and highlights the critical role of meticulously designed PE in addressing the extrapolation issue.

The paper introduces Mesa-Extrapolation, a novel method that utilizes a chunk-based triangular attention matrix and a new weave PE strategy, Stair PE. This approach achieves improved extrapolation performance without additional training. Key findings reveal a significantly reduced memory footprint and faster inference speed compared to other techniques. The paper also provides a theoretical analysis, confirming that weave PE enables extending the effective length of LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel solution to the extrapolation problem in LLMs, a critical challenge limiting their applicability to long inputs. Mesa-Extrapolation offers a scalable and efficient method, significantly reducing memory and improving inference speed, thus expanding the practical reach of LLMs. This opens new avenues for research in improving long-context understanding and developing more efficient LLMs.

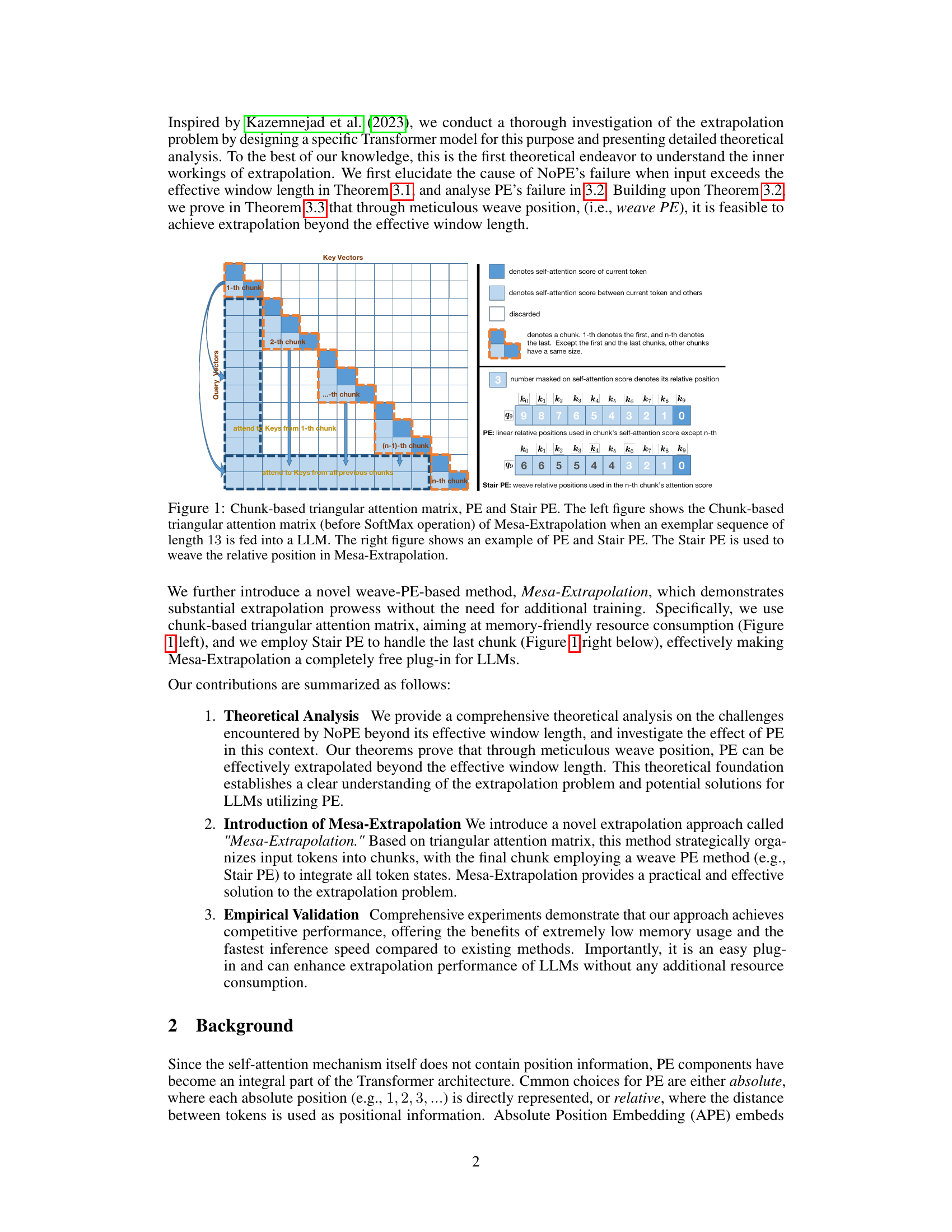

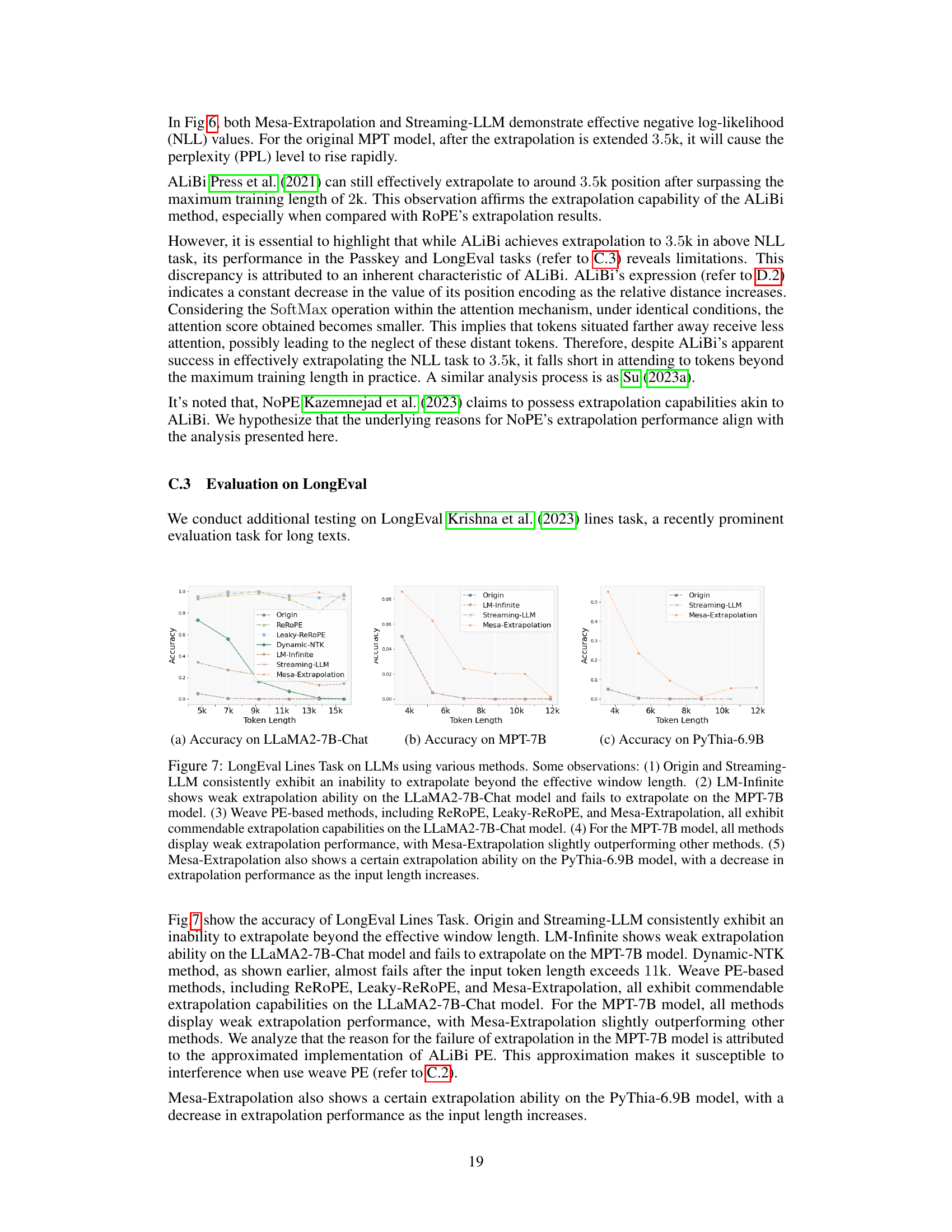

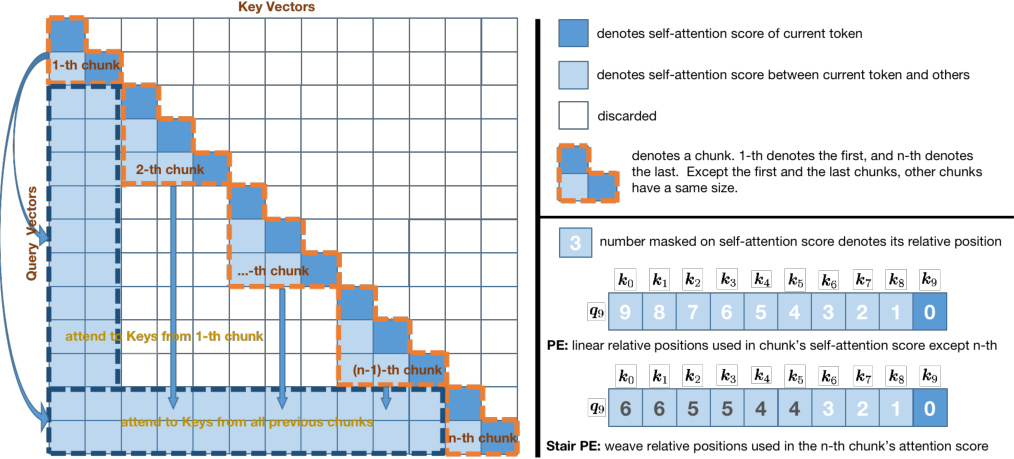

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the architecture of Mesa-Extrapolation, a method designed for enhanced extrapolation in LLMs. The left side shows a chunk-based triangular attention matrix, where the input sequence is divided into chunks to improve memory efficiency. The attention mechanism operates within and between these chunks. The right side demonstrates the concept of Position Encoding (PE) and Stair PE (a novel weave PE method). Standard PE uses linear relative positions within a chunk, while Stair PE introduces non-linearity, particularly useful for weaving together information from multiple chunks during extrapolation. The Stair PE helps extend the model’s ability to handle longer sequences.

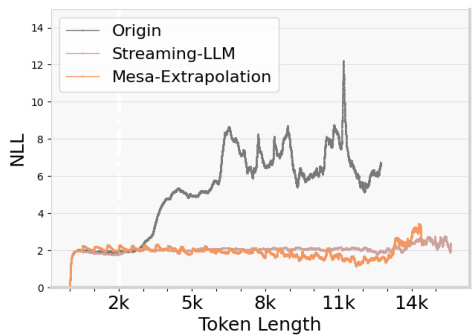

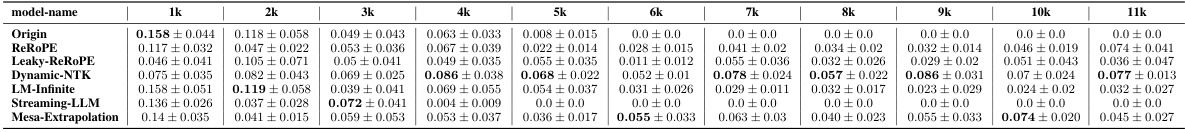

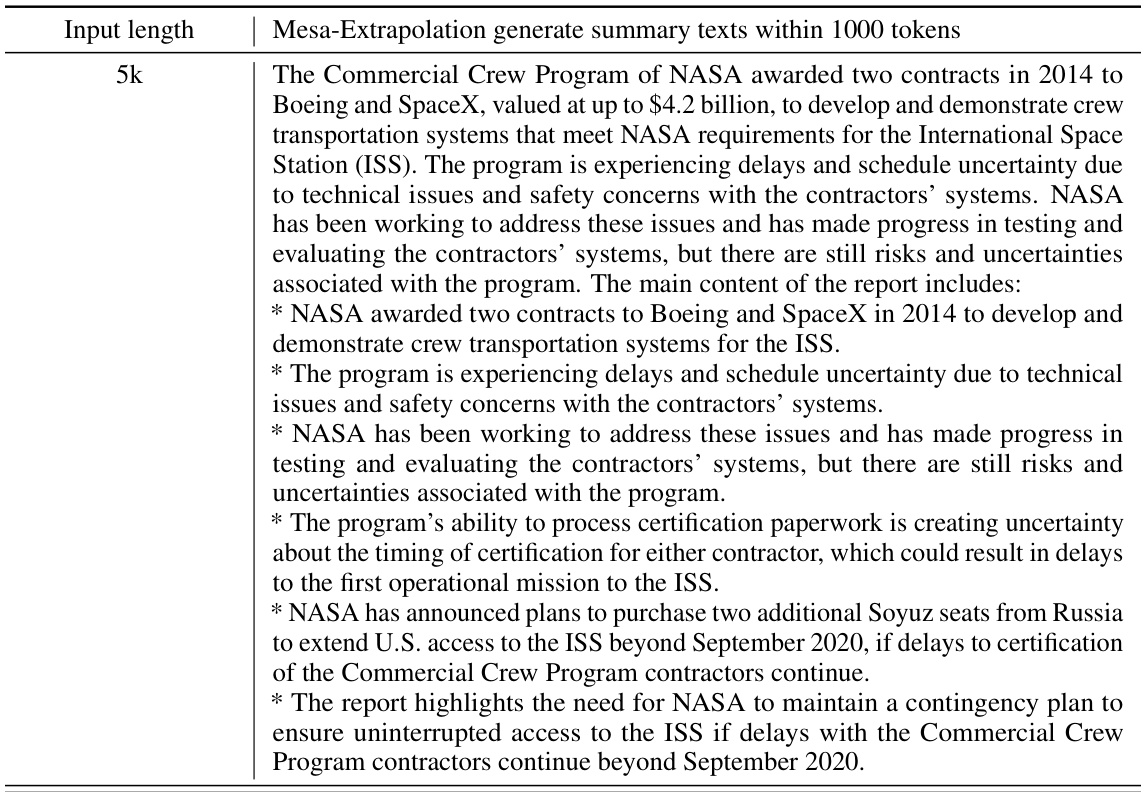

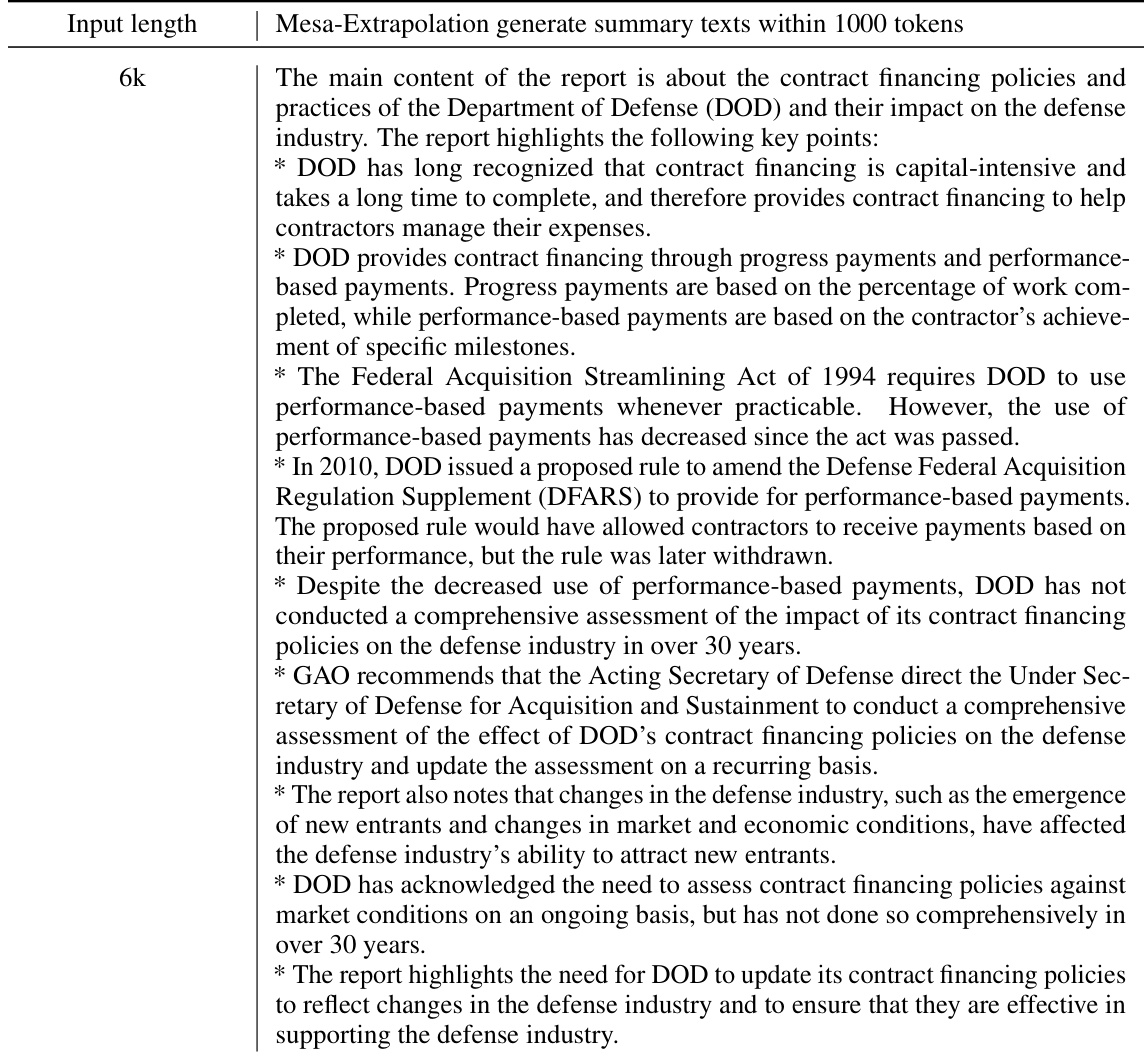

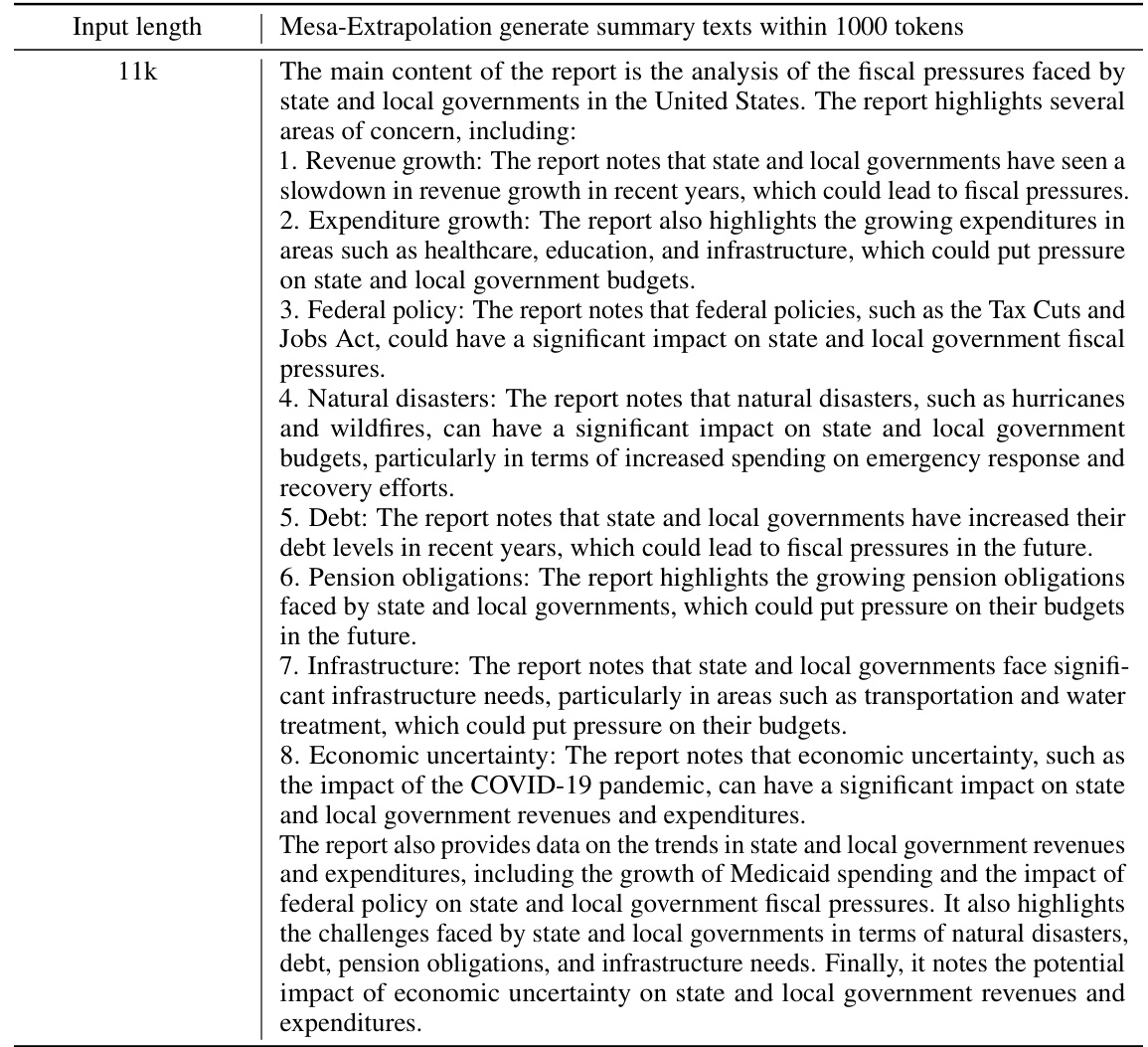

This table presents the ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L scores for different input lengths on the LLaMA2-7B-Chat model using the GovReport dataset. It compares the performance of Origin, ReROPE, Leaky-ReROPE, Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation. The table highlights that the Origin and Streaming-LLM models’ performance rapidly declines beyond the effective input window length, while the other methods exhibit varying degrees of performance, with Dynamic-NTK slightly better up to 11k tokens.

In-depth insights#

Weave PE Extrapolation#

Weave PE extrapolation methods in LLMs aim to enhance the model’s ability to handle sequences exceeding its maximum training length. These methods cleverly manipulate positional encoding (PE) information, often by weaving relative positional information in novel ways. The core idea is to avoid the catastrophic failure that occurs when simply extending PE linearly beyond its designed range. This failure is often attributed to the explosion of hidden state values. The theoretical analysis behind weave PE extrapolation often involves showing how a carefully designed PE scheme can generate a stable, bounded hidden state values for longer sequences. Successful approaches often involve chunk-based attention mechanisms and/or modified PE formulas that transition smoothly from the trained region to the extrapolated region. The improved extrapolation is generally achieved without additional training, making it a computationally efficient and practical solution to extend the application range of LLMs.

Mesa-Extrapolation#

Mesa-Extrapolation, as a novel method, is presented for enhancing the extrapolation capabilities of large language models (LLMs). It cleverly addresses the challenge of LLMs’ performance decline beyond their maximum training length. The core idea involves a chunk-based triangular attention matrix which improves memory efficiency and a Stair Position Encoding (Stair PE) method which is a weave PE method that enhances extrapolation. Theoretical analysis underpins the method’s effectiveness, proving its ability to extend effective window length without additional training costs. Experimental results on various LLMs and tasks demonstrate competitive performance, significantly reducing memory usage and inference latency compared to existing techniques. Further research could explore the optimization of Stair PE parameters and investigate the application of Mesa-Extrapolation to even larger LLMs and more diverse tasks.

Theoretical Analysis#

A theoretical analysis section in a research paper would rigorously examine the core concepts and assumptions underpinning the presented work. For a study on large language models (LLMs) and extrapolation, this section would likely involve formal mathematical proofs to demonstrate the claims made. It might focus on the limitations of existing positional encoding (PE) methods, showcasing how they fail outside their effective range. The analysis should then introduce a novel approach, perhaps “weave PE,” providing theorems and proofs to validate its ability to extend LLMs’ inference ability beyond the traditional effective window length. This would likely involve defining specific mathematical functions that demonstrate how this improved PE handles longer sequences. Finally, a good theoretical analysis would also likely discuss assumptions made and acknowledge any limitations of the model, strengthening the overall validity and robustness of the research’s findings.

Empirical Validation#

An Empirical Validation section in a research paper would rigorously test the proposed method’s effectiveness. This would involve designing comprehensive experiments, selecting appropriate datasets, and establishing clear evaluation metrics. The results should be presented transparently, including error bars and statistical significance tests. A strong Empirical Validation section will demonstrate the method’s superiority, showcase its benefits over existing methods, and discuss any limitations or unexpected behaviors. Comparative analysis against established baselines is crucial, ensuring a fair and meaningful evaluation. Furthermore, the discussion should highlight the method’s scalability and resource efficiency. Reproducibility is key; the section needs to provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the experiments. Ultimately, the strength of the Empirical Validation greatly influences the paper’s overall impact and credibility.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to other attention mechanisms beyond the Transformer architecture would broaden the applicability of the findings. Investigating the interplay between different positional encoding schemes and their effect on extrapolation is crucial. Developing more sophisticated weave PE methods that are computationally efficient and effective across a range of LLMs represents another key area. Finally, a comprehensive empirical evaluation across diverse downstream tasks and LLM architectures is essential to fully assess the potential of the proposed approach. Addressing the memory and computational limitations associated with some weave PE techniques warrants attention. The exploration of hybrid methods, which could combine the benefits of weave PE with other techniques, like sparse attention, is also a critical area to investigate.

More visual insights#

More on figures

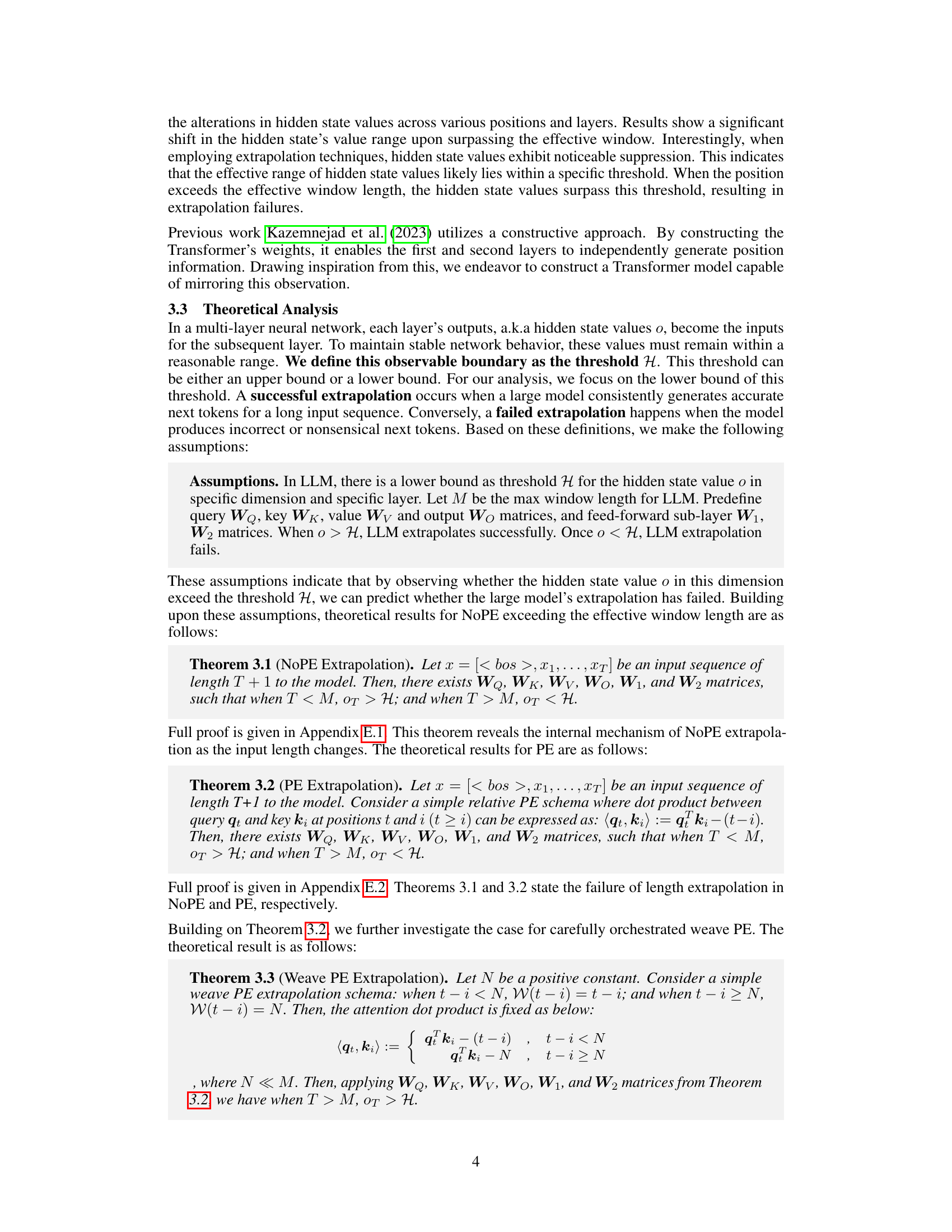

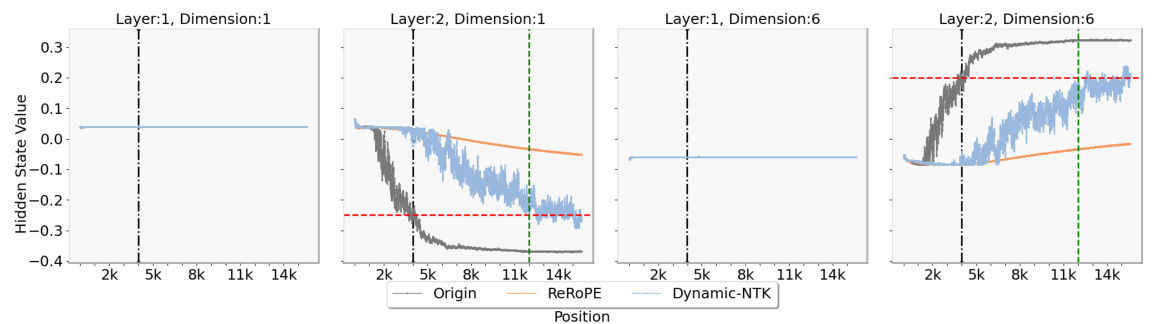

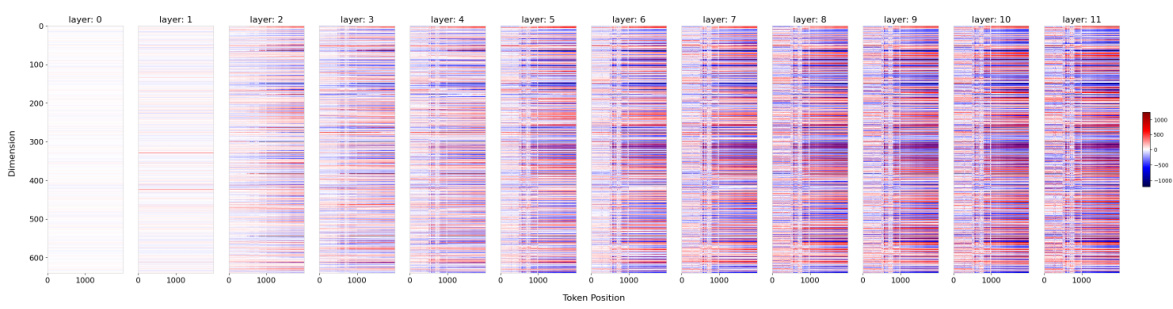

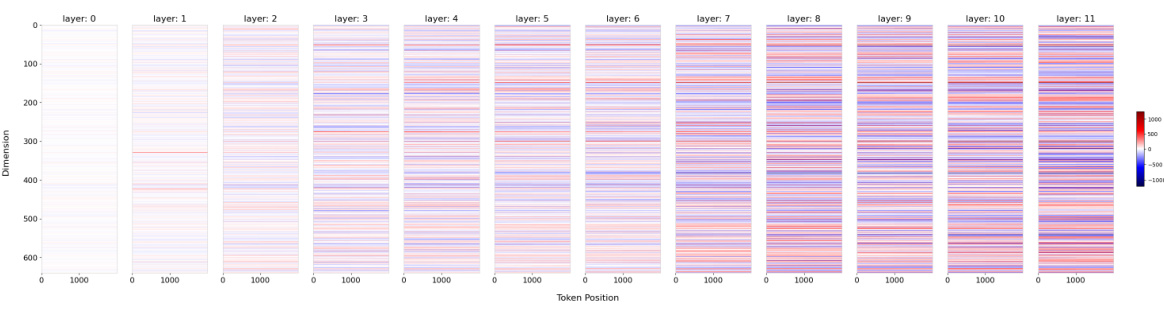

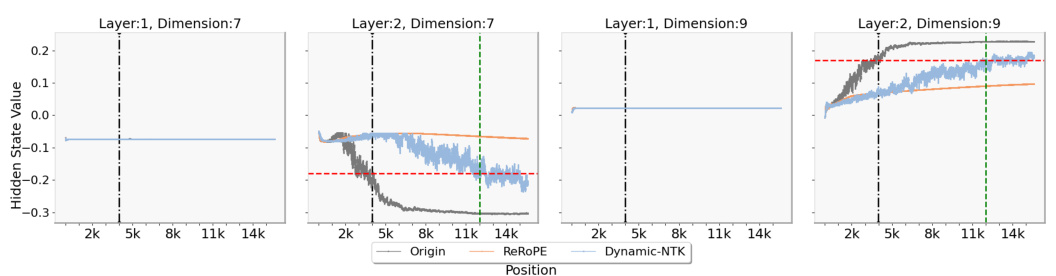

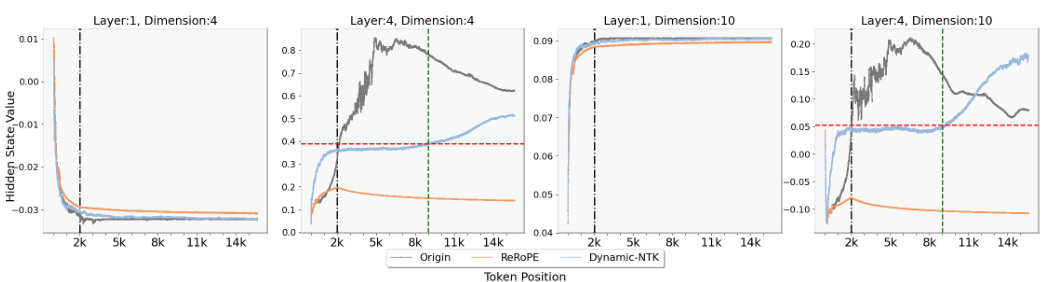

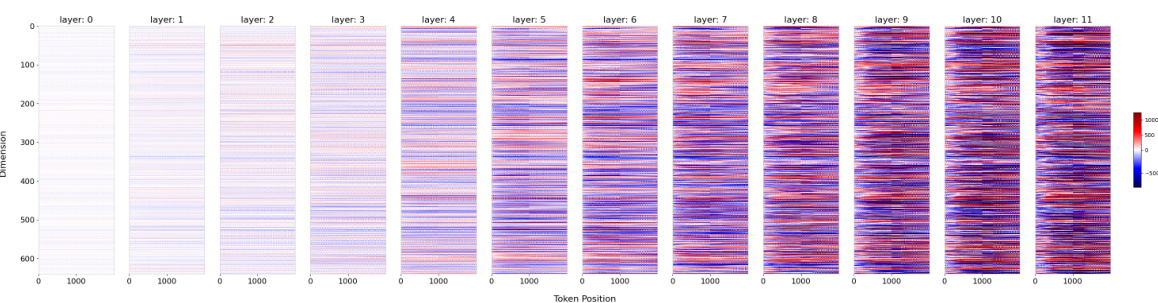

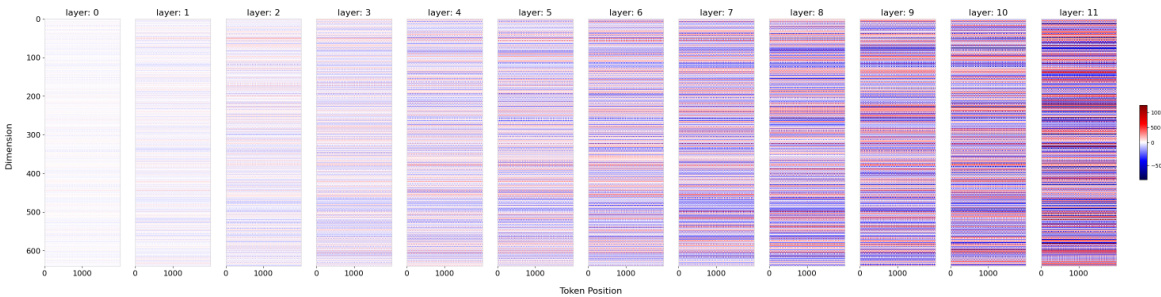

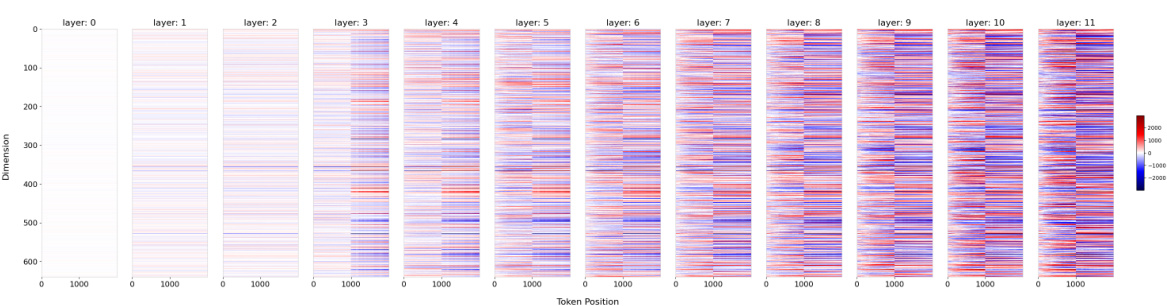

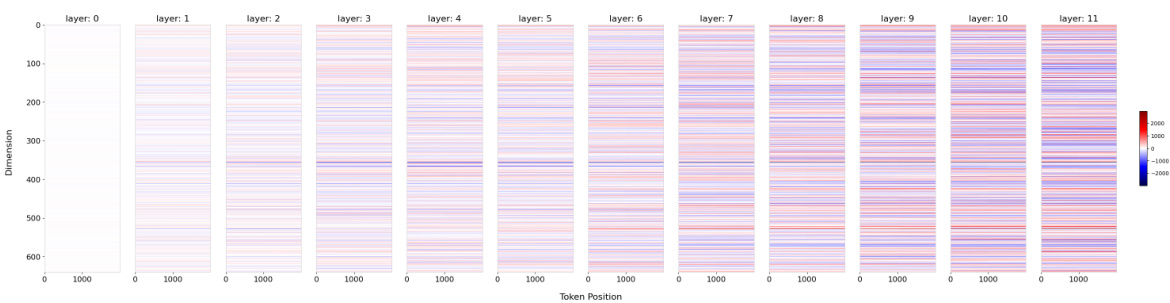

This figure shows the thresholds for hidden states observed at specific dimensions in the LLaMA2-7B-Chat model. The maximum training length of the model is indicated by a vertical dashed line. A horizontal dashed line marks the observed threshold for the hidden state value at the maximum training length. The plots show how the hidden state values change as the position changes. If the hidden state values exceed the threshold, extrapolation failure is indicated.

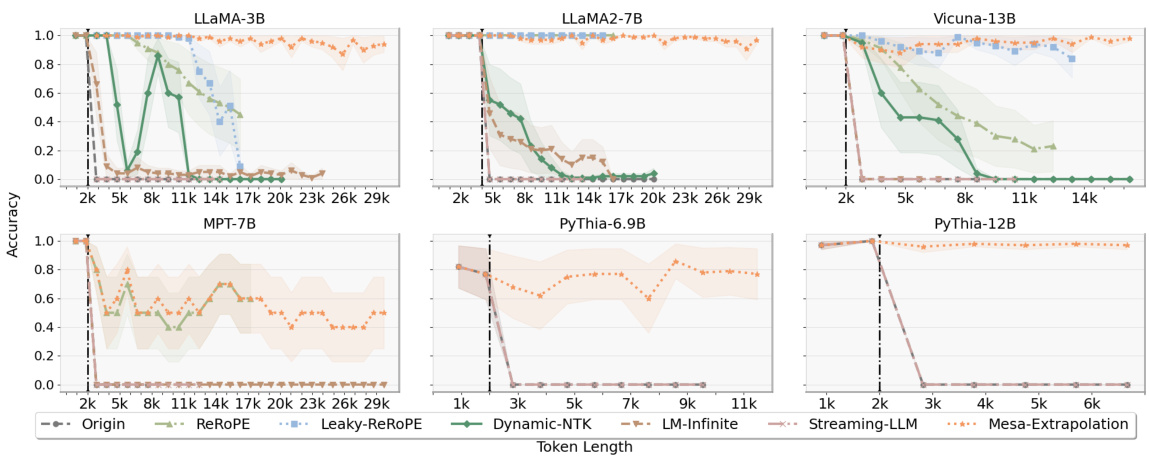

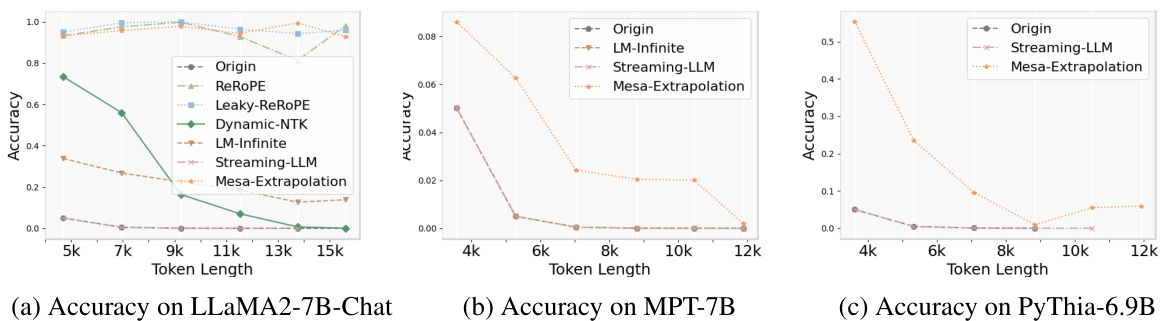

This figure shows the accuracy of different LLMs in retrieving a password from a sequence of varying lengths. The x-axis is the sequence length and the y-axis is the accuracy. The figure demonstrates that methods using weave positional encoding (Mesa-Extrapolation, ReRoPE, Leaky-ReROPE) show better extrapolation capabilities beyond the maximum training length compared to other methods. The early stopping seen in some methods is attributed to hardware limitations.

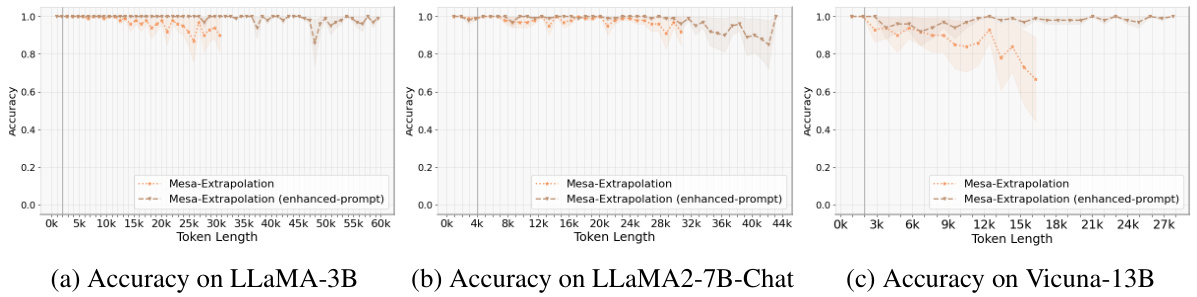

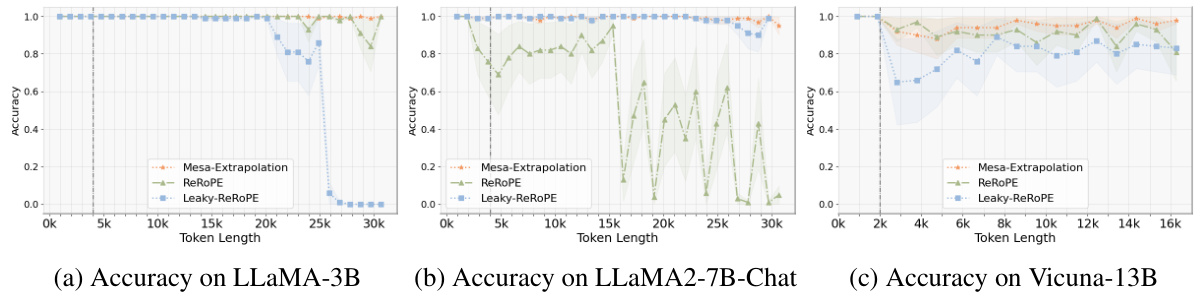

This figure compares the performance of different position encoding methods (Origin, ReRoPE, Leaky-ReROPE, Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation) on passkey retrieval tasks across various LLMs. The x-axis shows the input token length, and the y-axis shows the accuracy. The shaded regions indicate variance. The black dashed lines indicate the maximum training lengths of the models. The results show that weave PE-based methods like Mesa-Extrapolation maintain high accuracy even when exceeding the maximum training lengths, unlike the other methods which show significant performance degradation. The ’early stopping’ behavior seen in some methods is explained as a result of GPU memory limitations.

This figure shows the accuracy of different LLMs in retrieving a password hidden within a text sequence of varying lengths. The x-axis shows the input sequence length, and the y-axis represents the accuracy (percentage of correct answers). The different colored areas represent the variance in accuracy. The black dashed line indicates the maximum training length of the model. The key takeaway is that the methods which weave position encoding (ReROPE, Leaky-ReROPE, and Mesa-Extrapolation) perform consistently well even when the input length exceeds the model’s maximum training length, while other methods’ performance quickly degrades.

This figure displays the performance of different LLMs (LLaMA-3B, MPT-7B, LLaMA2-7B, Vicuna-13B, Pythia-6.9B, Pythia-12B) on a password retrieval task using various methods (Origin, ReRoPE, Leaky-ReROPE, Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation). The x-axis shows the input token length, and the y-axis shows the accuracy of the models in retrieving the password. The figure shows that weave PE-based methods (ReRoPE, Leaky-ReROPE, Mesa-Extrapolation) maintain high accuracy even when the input length exceeds the maximum training length. The ’early stopping’ observed in some methods is attributed to limitations of the hardware resources used.

This figure compares the performance of different methods for extrapolating LLMs on a password retrieval task. The x-axis shows the input sequence length, and the y-axis shows the accuracy of retrieving the password. The results show that methods using weave position encoding (Mesa-Extrapolation, ReRoPE, and Leaky-ReROPE) maintain higher accuracy even when input length exceeds the maximum training length, whereas other methods experience a significant drop in accuracy.

This figure shows the results of passkey retrieval tasks on various LLMs using different methods. The x-axis represents the input token length, and the y-axis represents the accuracy of retrieving a hidden password within the input sequence. Different colored areas show the variance in accuracy across multiple runs. The black dashed line indicates the maximum training length of the LLMs. The figure highlights that methods using weave positional encoding (ReRoPE, Leaky-ReROPE, and Mesa-Extrapolation) maintain consistently high accuracy even beyond the maximum training length, while other methods show significant drops in accuracy. The ’early stopping’ phenomenon observed in some methods is attributed to GPU memory limitations.

This figure compares the accuracy of different extrapolation methods (Origin, ReRoPE, Leaky-ReROPE, Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation) on various LLMs (LLaMA-3B, MPT-7B, LLaMA2-7B-Chat, Vicuna-13B, Pythia-6.9B, and Pythia-12B) for passkey retrieval tasks. The x-axis represents the input token length, and the y-axis represents the accuracy. The shaded areas represent variance. The black dashed line indicates the maximum training length of each LLM. The results show that weave PE-based methods (ReRoPE, Leaky-ReROPE, and Mesa-Extrapolation) generally maintain accuracy even beyond the maximum training length, suggesting improved extrapolation capabilities compared to other methods. The ’early stopping’ seen in some methods is attributed to GPU memory limitations.

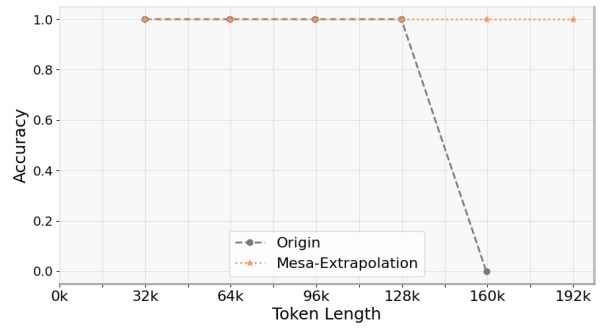

This figure shows the result of applying the original model and the Mesa-Extrapolation method on the Phi-3-mini-128k-instruct model for the NIAH task in the Ruler dataset. The x-axis represents the input token length, while the y-axis represents the accuracy. The original model’s performance drops sharply after reaching the 128k token limit. In contrast, the Mesa-Extrapolation method successfully extrapolates up to 192k tokens, demonstrating its ability to extend the effective input window length.

This figure illustrates the core components of the Mesa-Extrapolation method. The left panel shows a chunk-based triangular attention matrix, a memory-efficient approach for handling long sequences. The sequence is divided into chunks, with each chunk processed independently, reducing computational cost. The right panel demonstrates the difference between standard positional encoding (PE) and the novel Stair PE used in Mesa-Extrapolation. Stair PE is designed to effectively weave positional information into the last chunk of the sequence, enabling the model to extrapolate effectively beyond its typical effective range.

This figure illustrates the architecture of Mesa-Extrapolation, showing how the input sequence is divided into chunks, each with its own triangular attention matrix. It highlights the use of positional encoding (PE) and Stair PE, a novel method introduced in the paper, within the attention mechanism. Stair PE is specifically applied to the final chunk to manage the relative positional information and extend extrapolation capabilities beyond the model’s effective range. The left part displays the chunk-based triangular attention matrix, and the right depicts an example of the PE and Stair PE mechanisms.

This figure shows the observed thresholds for hidden state values in different dimensions (1 and 6) and layers (1 and 2) of the LLaMA2-7B-Chat model. The vertical dashed line represents the maximum training length (4k tokens). The horizontal dashed line represents the threshold for each dimension and layer. The plot shows that when the hidden state value surpasses the threshold (red dashed line), extrapolation fails. This visualization supports the paper’s theoretical analysis of extrapolation failure in LLMs.

This figure shows the hidden state values at specific dimensions (1 and 6) on layers 1 and 2 of the LLaMA2-7B-Chat model, highlighting the concept of a threshold for successful extrapolation. The threshold (red dashed line) is determined by the hidden state value at the maximum training length (black dashed line; 4k). The plot shows that when the hidden state values exceed this threshold, extrapolation fails. Two different methods (Origin and ReROPE) are compared, with ReROPE maintaining a stable performance beyond the threshold while Origin fails.

This figure illustrates the architecture of Mesa-Extrapolation, a novel method for enhanced extrapolation in LLMs. The left panel shows a chunk-based triangular attention matrix, which improves memory efficiency by processing the input sequence in smaller chunks. The right panel demonstrates the difference between conventional positional encoding (PE) and the proposed Stair PE. Stair PE uses a chunk-based weave to carefully arrange relative positions, enabling better extrapolation beyond the model’s effective window length.

This figure illustrates the core components of the Mesa-Extrapolation method. The left panel depicts a chunk-based triangular attention matrix which is memory-efficient. The right panel shows a comparison between standard Positional Encoding (PE) and the novel Stair PE, highlighting how Stair PE weaves relative positions to enhance extrapolation capabilities.

This figure illustrates the architecture of Mesa-Extrapolation, highlighting its chunk-based triangular attention mechanism and the novel Stair PE method. The left panel depicts how the input sequence is divided into chunks for processing within the triangular matrix, aiming for memory efficiency. The right panel contrasts the traditional linear PE with the proposed Stair PE, which adaptively weaves the relative positions to enhance extrapolation beyond the model’s effective range.

This figure illustrates the architecture of Mesa-Extrapolation, a novel method for enhancing extrapolation in LLMs. The left panel depicts a chunk-based triangular attention matrix, which efficiently manages memory consumption by processing the input sequence in smaller chunks. The right panel demonstrates the concept of Positional Encoding (PE) and Stair PE, showing how Stair PE weaves relative positions to achieve improved extrapolation performance. Stair PE is specifically designed for the final chunk, combining information from all previous chunks.

More on tables

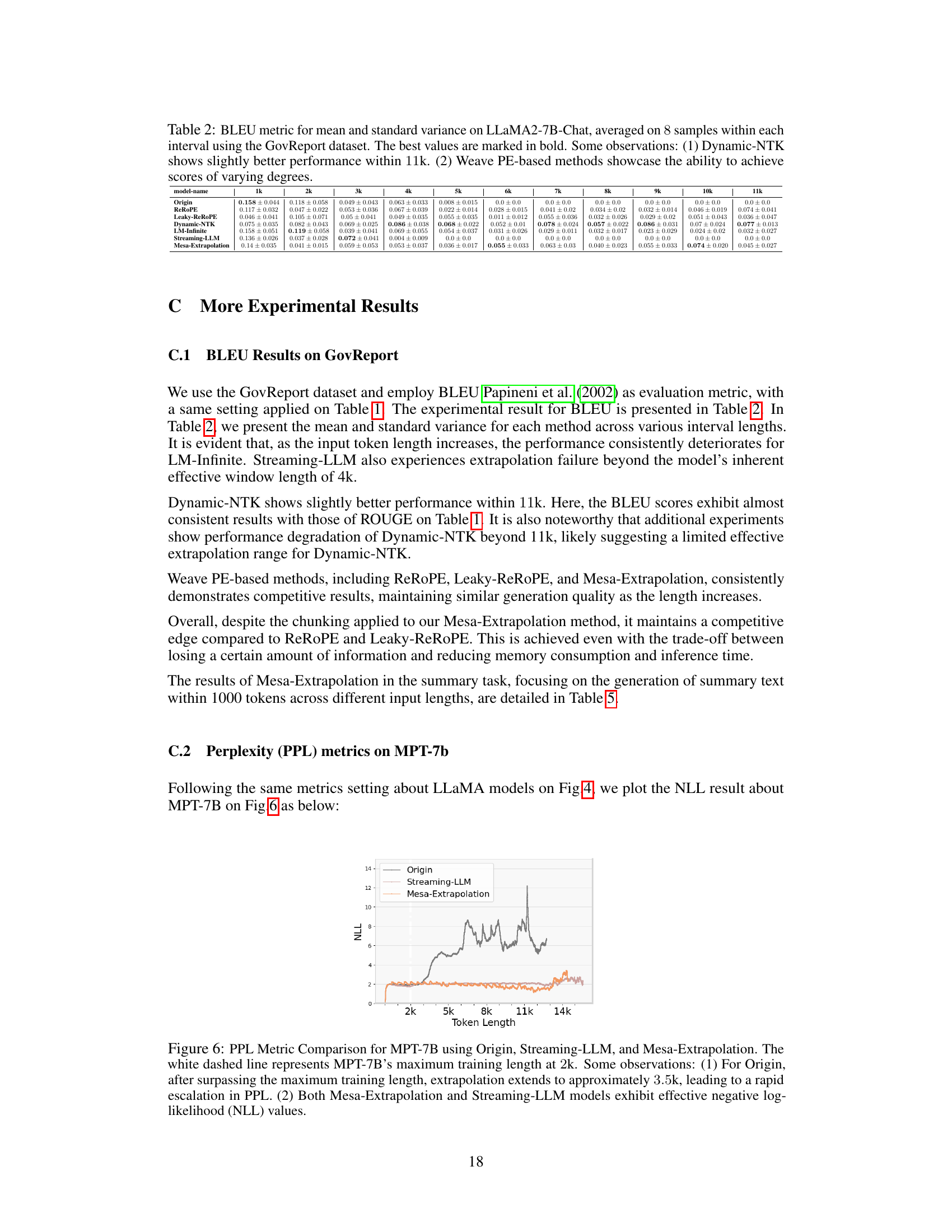

This table presents the BLEU scores (mean and standard deviation) obtained using different extrapolation methods on the LLaMA2-7B-Chat model for the GovReport summarization task. The results are broken down by input sequence length (from 1k to 11k tokens) and method (Origin, ReROPE, Leaky-ReROPE, Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, Mesa-Extrapolation). The best-performing method for each input length is highlighted in bold. The observations highlight that Dynamic-NTK performs relatively well up to an input length of 11k, while the weave PE methods generally maintain consistent performance across the range of input lengths.

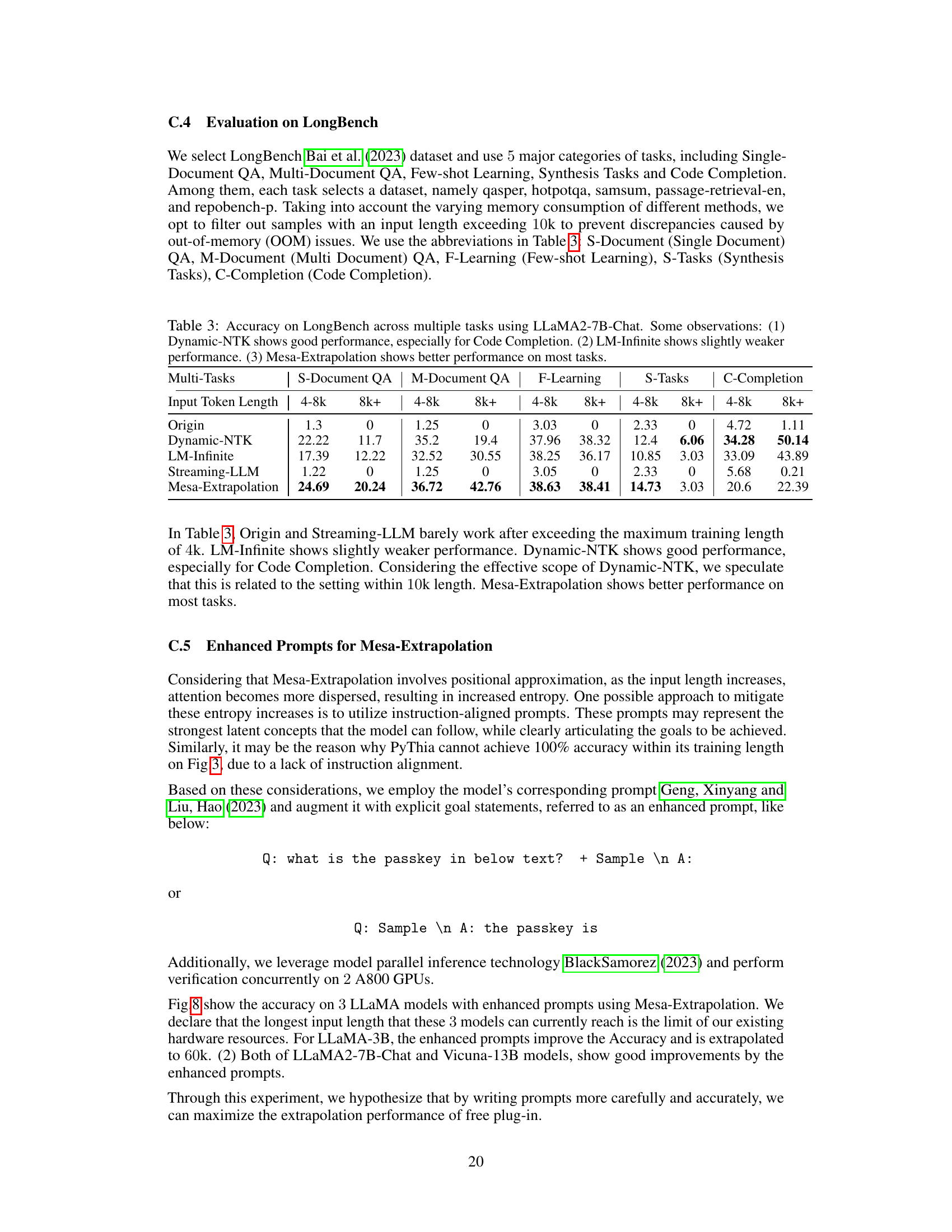

This table presents the accuracy results of different LLMs on various tasks from the LongBench benchmark. The LLMs tested include Origin, Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation. The tasks are categorized into five groups: Single-Document QA, Multi-Document QA, Few-shot Learning, Synthesis Tasks, and Code Completion. The table shows accuracy for each LLM on each task category and for two different input lengths (4-8k tokens and 8k+ tokens). The results indicate that Mesa-Extrapolation generally outperforms the other methods, especially on the Code Completion task.

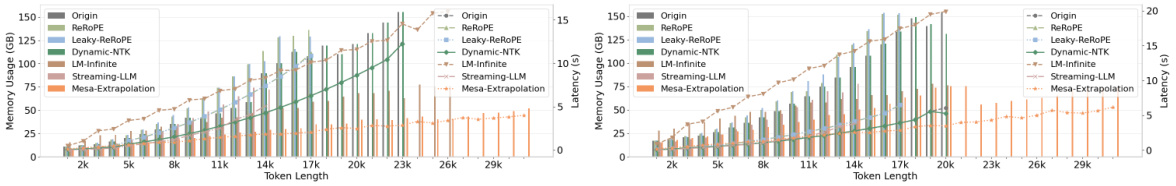

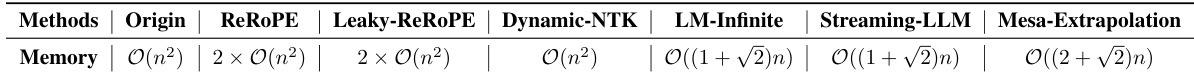

This table presents a theoretical analysis of the memory usage of different methods for handling long sequences in LLMs, categorized by their scaling behavior. Origin and Dynamic-NTK show quadratic scaling (O(n²)), while ReRoPE and Leaky-ReROPE exhibit even higher quadratic scaling (2 × O(n²)). In contrast, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation demonstrate linear scaling (O(n)), with Mesa-Extrapolation showing a slightly higher linear scaling of O((2+√2)n). This analysis highlights the computational efficiency advantage of the linear scaling methods compared to the quadratic ones, particularly as input sequence length (n) increases.

This table presents the accuracy results of different LLMs on various tasks from the LongBench dataset. The LLMs tested include Origin, Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation. The tasks are categorized into Single-Document QA, Multi-Document QA, Few-shot Learning, Synthesis Tasks, and Code Completion. The table shows that Mesa-Extrapolation generally outperforms other methods, particularly on tasks beyond simple question answering. Dynamic-NTK shows relatively good performance, especially on Code Completion, while LM-Infinite and Streaming-LLM have lower accuracy.

This table presents the accuracy results of different LLMs on various tasks from the LongBench benchmark. The models compared include Origin (baseline), Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation. The tasks are categorized into five groups: Single-Document QA, Multi-Document QA, Few-shot Learning, Synthesis Tasks, and Code Completion. The table shows accuracy scores for each model across different input lengths (4-8k and 8k+) for each task. Observations highlight that Dynamic-NTK performs relatively well, especially on code completion, while LM-Infinite shows slightly lower performance. Mesa-Extrapolation generally outperforms other methods across most tasks.

This table presents the accuracy results of different LLMs on various tasks from the LongBench benchmark. The tasks cover several categories including question answering (single and multi-document), few-shot learning, text synthesis, and code completion. Three different LLMs are tested: Origin (baseline), Dynamic-NTK, and Mesa-Extrapolation. The table shows that Mesa-Extrapolation generally outperforms the other models, although Dynamic-NTK shows better performance on code completion tasks. LM-Infinite shows comparatively weaker performance.

This table presents the accuracy results on LongBench benchmark across five different tasks (Single-Document QA, Multi-Document QA, Few-shot Learning, Synthesis Tasks, Code Completion) using three different methods: Origin, Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation. The results are categorized by input token length (4-8k and 8k+). The observations highlight the relatively strong performance of Mesa-Extrapolation, particularly in comparison to the Origin and Streaming-LLM methods, which show limited extrapolation capabilities beyond the original training length.

This table presents the accuracy results of different LLMs on various tasks from the LongBench benchmark. The LLMs evaluated include Origin, Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation. The tasks are categorized into five groups: Single-Document QA, Multi-Document QA, Few-shot Learning, Synthesis Tasks, and Code Completion. The table shows the accuracy for each model on each task, broken down by input token length (4-8k and 8k+). The observations highlight that Dynamic-NTK performs well on Code Completion, while LM-Infinite shows slightly lower accuracy, and Mesa-Extrapolation generally outperforms the other models across different tasks.

This table presents the accuracy results of different LLMs on five tasks from the LongBench benchmark. The tasks assess various capabilities including question answering, summarization, and code generation. The results show that Mesa-Extrapolation performs better overall, while Dynamic-NTK excels in code completion tasks.

This table presents the accuracy results of different LLMs on various tasks from the LongBench benchmark. The LLMs tested include Origin, Dynamic-NTK, LM-Infinite, Streaming-LLM, and Mesa-Extrapolation. The tasks cover several categories: Single-Document QA, Multi-Document QA, Few-shot Learning, Synthesis Tasks, and Code Completion. The table shows that Mesa-Extrapolation generally outperforms other methods, especially on tasks such as Code Completion. Dynamic-NTK shows good performance, particularly on Code Completion. LM-Infinite shows slightly weaker performance than other methods.

Full paper#