↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world systems, such as disease spread or species evolution, can be modeled using population dynamics. Existing approaches to control these systems often rely on simplifying assumptions such as noise-free dynamics, making them impractical for real-world application. This limits our ability to effectively manage these systems which can change in complex and unforeseen ways.

This paper tackles this issue by developing a new online control framework that incorporates noise and other uncertainties inherent to real-world problems. The framework uses an efficient gradient-based controller with strong theoretical guarantees (near-optimal regret bounds) for a broad class of linear dynamical systems. The researchers demonstrate the efficacy of their method using various population models, showcasing its robustness even in nonlinear scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in population dynamics and online control because it bridges the gap between theoretical models and real-world complexities. It offers a robust and generic framework for population control, addressing the limitations of existing methods that struggle with noisy or adversarial dynamics. This opens doors to tackling complex real-world problems across various fields like epidemiology and evolutionary game theory, paving the way for more effective and adaptable population control strategies.

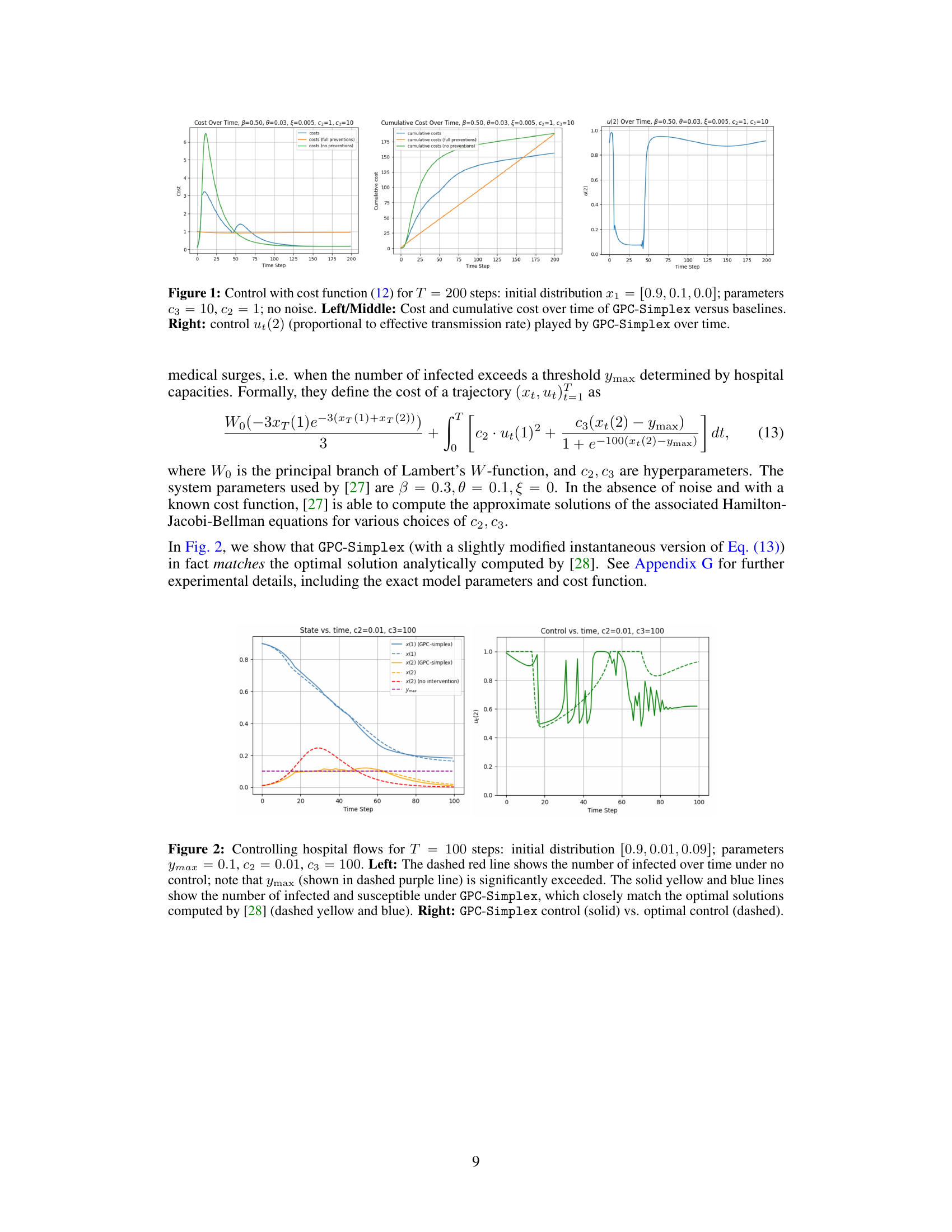

Visual Insights#

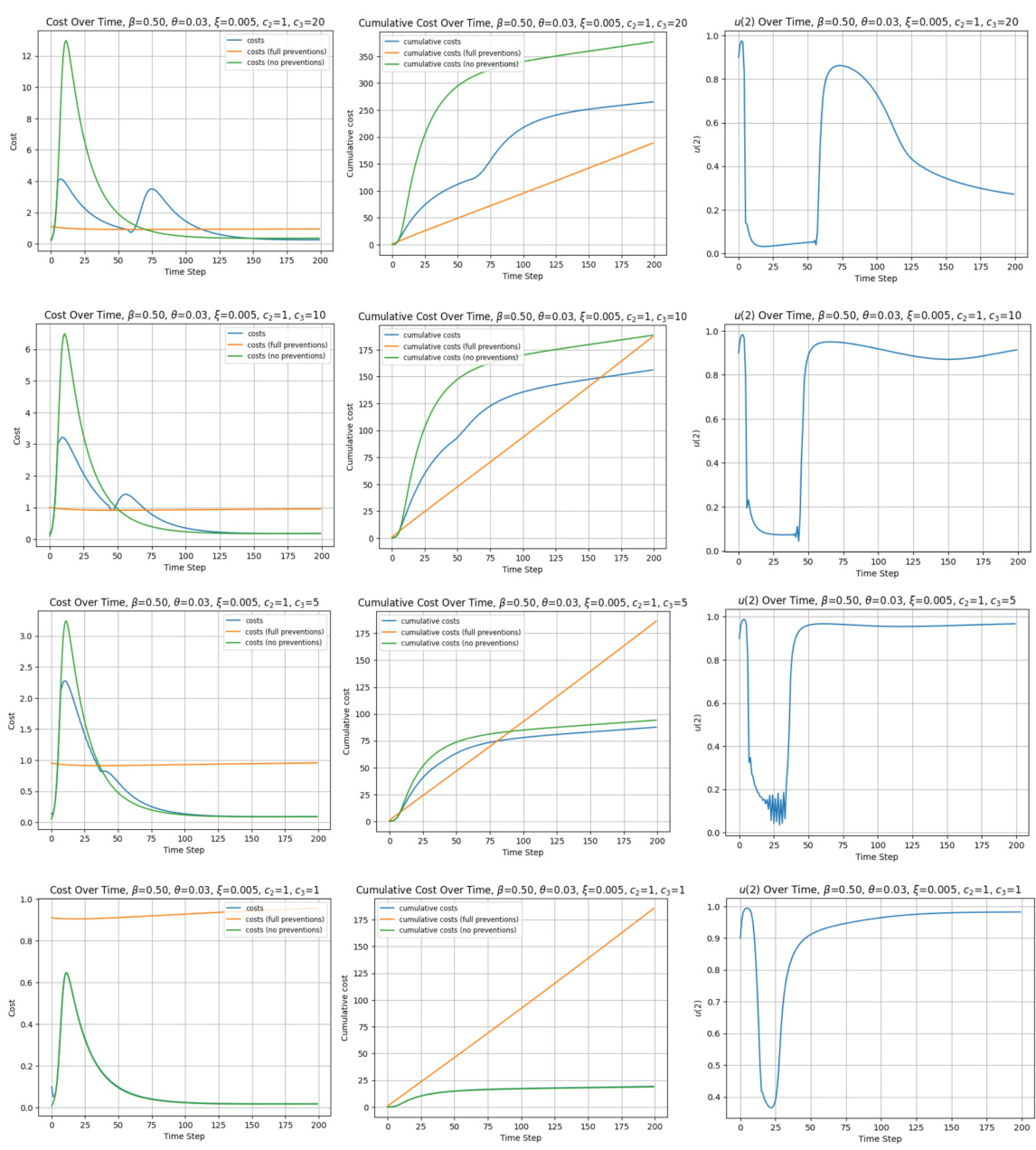

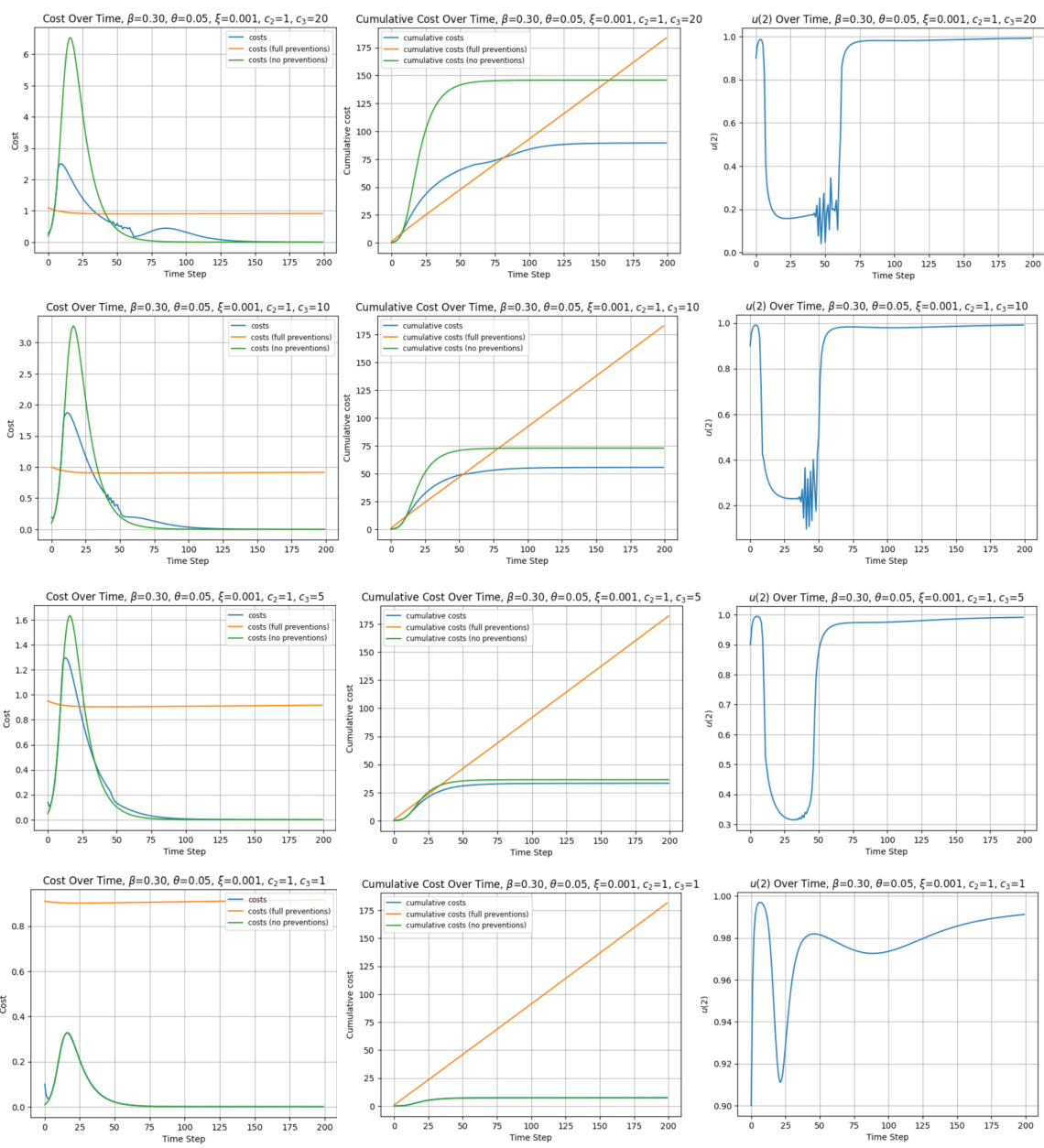

This figure shows the results of applying the GPC-Simplex algorithm to a controlled disease transmission model (SIR model). The left and middle panels compare the cost and cumulative cost of GPC-Simplex against two baseline methods: one with full prevention (ut = [1, 0]) and one with no prevention (ut = [0, 1]). The right panel displays the control ut(2) used by GPC-Simplex over time, which is proportional to the effective transmission rate. The results demonstrate that GPC-Simplex effectively controls the spread of the disease while minimizing costs, outperforming the baseline methods.

In-depth insights#

Online Population Control#

Online population control presents a complex challenge, demanding innovative approaches to manage populations effectively and ethically. Real-world population dynamics are inherently nonlinear and influenced by various unpredictable factors, necessitating robust control strategies. This necessitates a move away from traditional, model-specific methods towards more adaptable and generic frameworks. The application of online control techniques, which excel in handling adversarial and noisy environments, offers a promising avenue. Online control algorithms, by adapting to time-varying cost functions and adversarial perturbations, show promise in achieving near-optimal results. The research explores the theoretical guarantees of online control methods for population dynamics, particularly within linear dynamical systems (LDSs), while also addressing the challenges posed by non-linear systems. Empirical evaluations on models like SIR and replicator dynamics demonstrate the efficacy and robustness of these approaches. The methodology’s inherent adaptability makes it suitable for real-world applications, offering a flexible framework for dynamic population management. However, further research is needed to address the limitations of online control when dealing with significant nonlinearities, unobservable perturbations, and highly complex systems.

Gradient-Based Controller#

A gradient-based controller, in the context of online control of population dynamics, is a method to adjust control parameters iteratively based on the gradient of a cost function. Efficiency is key, as it allows for real-time adjustments without needing extensive pre-computation. The effectiveness hinges on how well the cost function reflects desired population levels and the algorithm’s ability to handle complex, potentially adversarial, population dynamics. Regret bounds are crucial for evaluating controller performance, ensuring near-optimality compared to optimal static policies. The application to non-linear systems like SIR and replicator dynamics demonstrates the algorithm’s robustness and potential for broader application in diverse fields where population modeling is relevant. Robustness to noise and model inaccuracies is important, as real-world population changes are often unpredictable. Empirical evaluations provide evidence of the controller’s practical effectiveness.

Simplex LDS Model#

The Simplex LDS (Linear Dynamical System) Model is a significant contribution, modifying the standard LDS to ensure that the system’s state always remains within the probability simplex. This is crucial for modeling populations or distributions where the state variables represent proportions or probabilities that must sum to one. The modification involves constraining the transition matrices and control inputs to guarantee this simplex constraint. This constraint significantly impacts the design of control algorithms, making conventional approaches unsuitable. The paper introduces a novel algorithm, GPC-Simplex, that leverages the structure of the simplex LDS for more effective population control, achieving strong regret bounds against a natural comparator class of policies within the simplex, which are policies with bounded mixing time. The theoretical guarantees address the challenges posed by the simplex restriction, offering a novel approach to handling such constrained dynamical systems. The model’s practical applicability is demonstrated through simulations on both linear and non-linear population models.

Regret Guarantees#

Regret guarantees, a core concept in online learning, are crucial for evaluating the performance of control algorithms against a benchmark policy. In the context of population control, a strong regret guarantee ensures that the algorithm’s performance is close to optimal, despite unpredictable changes in population dynamics. This is particularly important in real-world scenarios that are often characterized by noise, uncertainty, and adversarial influences. The challenge lies in designing controllers that can efficiently adapt to evolving circumstances without compromising performance. Therefore, carefully defining the comparator class, the set of benchmark policies against which regret is measured, is essential. The choice of the comparator class needs to balance computational tractability with practical relevance. The paper likely establishes regret bounds for a class of policies that are both reasonably expressive and computationally feasible, such as linear policies or policies with bounded mixing time. A strong regret bound indicates that even under adversarial conditions, the algorithm’s cumulative cost remains close to the optimal cost, establishing robustness and efficiency. The theoretical analysis and the choice of comparator policies are very important and should be carefully justified in relation to real world population models.

Empirical Evaluations#

The section on “Empirical Evaluations” would ideally present a robust validation of the proposed online control algorithm. It should demonstrate effectiveness beyond theoretical guarantees by testing the algorithm on diverse real-world or realistic simulated population dynamic models. Key aspects to assess are the algorithm’s performance in handling non-linear dynamics (e.g., SIR, replicator dynamics), its robustness to noise and adversarial perturbations, and its computational efficiency. The use of appropriate baseline methods for comparison is crucial for a proper evaluation of its capabilities. The results should be reported clearly, likely through graphs and tables illustrating key metrics such as regret, cost, and the algorithm’s learning curve. A discussion of parameter sensitivity and a comparison to known optimal controllers (if available) further strengthen the evaluation. A thoughtful analysis comparing the empirical performance to the theoretical bounds is critical, identifying any discrepancies and offering potential explanations. The choice of models and evaluation metrics directly impacts the overall conclusiveness of the empirical study; the methodology should be rigorously described to ensure reproducibility.

More visual insights#

More on figures

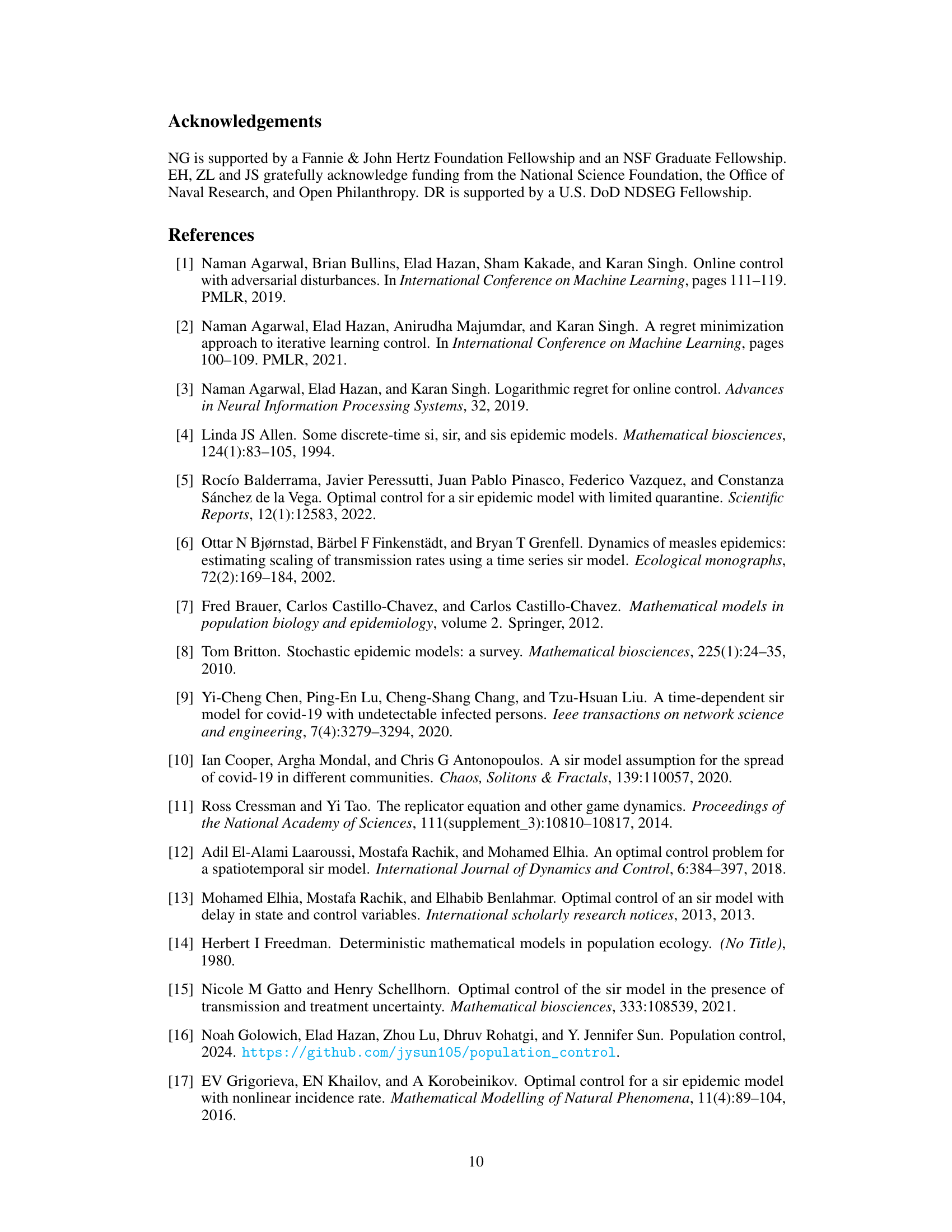

This figure compares the performance of the GPC-Simplex algorithm against the optimal control and a no-intervention baseline for a controlled SIR model simulating hospital flows. The left panel shows that GPC-Simplex effectively controls the number of infected individuals, preventing it from exceeding the hospital capacity (ymax), unlike the no-intervention scenario. The right panel demonstrates that the control strategy learned by GPC-Simplex closely resembles the optimal control strategy.

This figure provides an intuitive illustration of the lower bound for simplex LDS in Theorem 30. It shows the trajectory of two comparator policies (πº and π¹) under different perturbation sequences. The areas S1, S2, and S3 represent the regret incurred by an arbitrary policy under these two sequences, which sums to Ω(T). This demonstrates the impossibility of achieving sublinear regret against the class of all marginally stable policies for simplex LDS without mixing time assumption.

This figure compares the performance of the GPC-Simplex algorithm against two baselines (full prevention and no prevention) for a controlled SIR model with two different perturbation sequences. The top row shows the results with a specific perturbation sequence (wt = [0,1,0]), while the bottom row shows the results with a normalized uniform random vector perturbation. The plots display the cost, cumulative cost, and control value (u(2)) over time.

This figure compares the performance of the GPC-Simplex algorithm against two baselines (no prevention and full prevention) for controlling the spread of a disease using a controlled SIR model. It shows instantaneous and cumulative costs over time, along with the control applied (ut(2)). Different cost parameters (C2, C3) are tested, demonstrating GPC-Simplex’s ability to adapt to various cost functions.

This figure compares the performance of GPC-Simplex to two baselines (no prevention and full prevention) across four different parameter settings for the cost function in the controlled SIR model. It shows instantaneous and cumulative costs over time, as well as the control strategy employed by GPC-Simplex (represented as u(2)). The results demonstrate GPC-Simplex’s ability to adapt its control strategy to different cost function parameters while outperforming the baselines.

This figure shows the results of an experiment on a dynamical system using three different control methods: GPC-Simplex, Best Response, and Default control. The left plot compares the instantaneous costs over time for each method, highlighting that GPC-Simplex outperforms the default control and approaches the performance of the Best Response controller. The right plot visualizes the population’s evolution of different strategies (Rock, Scissors, Paper) across the 100 timesteps, revealing how the distribution changes over time under the influence of GPC-Simplex control.

This figure compares the performance of GPC-Simplex against two baselines (Best Response and default control) for a dynamical system with a random cost function. The x-axis represents the time step, and the y-axis shows the cost. The non-continuity in the cost function means that the plotted cost at each time step is the average of the costs over the last 15 time steps. GPC-Simplex shows better performance compared to the default control but is slightly outperformed by the Best Response controller in the long run.

Full paper#