↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many critical decisions rely on experimental data, but traditional Bayesian Experimental Design (BED) methods focus only on parameter inference, neglecting the downstream decision-making process. This leads to suboptimal experimental designs that don’t maximize decision quality. Furthermore, existing amortized BED methods, which aim to speed up design generation, suffer from the same limitation.

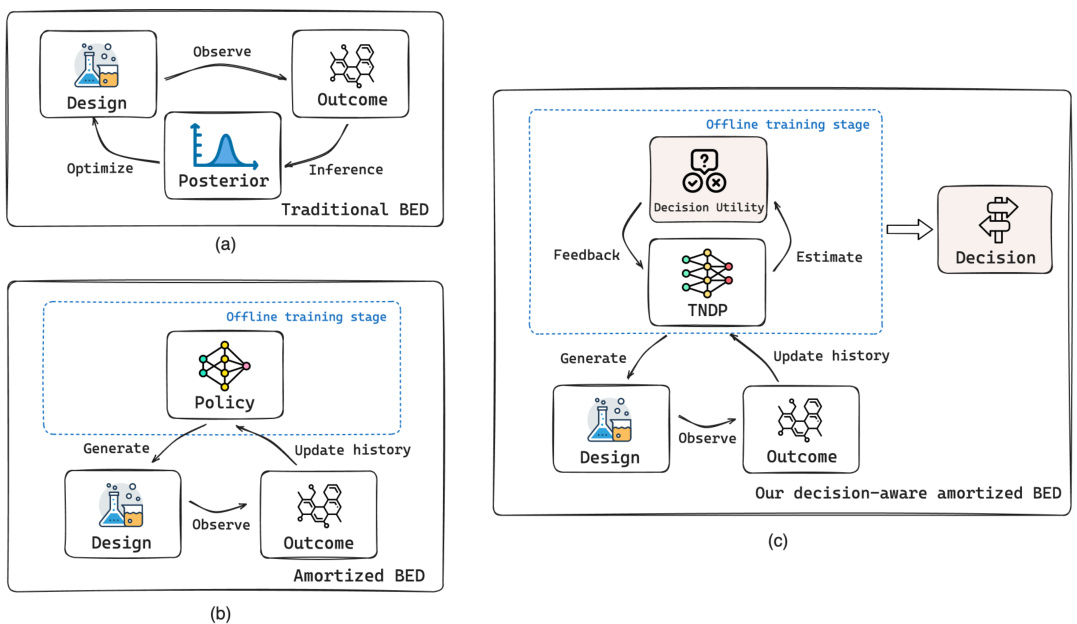

This paper introduces a novel method called Transformer Neural Decision Process (TNDP) to resolve these issues. TNDP integrates decision utility directly into the experimental design process, ensuring designs are optimal for decision-making. It uses a dual-output architecture, one for generating designs and the other for predictive distribution approximation which enables the system to make accurate downstream decisions. The performance of TNDP is empirically verified across several tasks, demonstrating significant improvements over existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly advances Bayesian experimental design by directly incorporating downstream decision-making into the design process. This addresses a critical limitation of existing methods which often focus solely on parameter inference, leading to suboptimal designs for real-world applications where decisions are the ultimate goal. The proposed amortized framework offers significant computational advantages and paves the way for more efficient and effective decision-making in various fields.

Visual Insights#

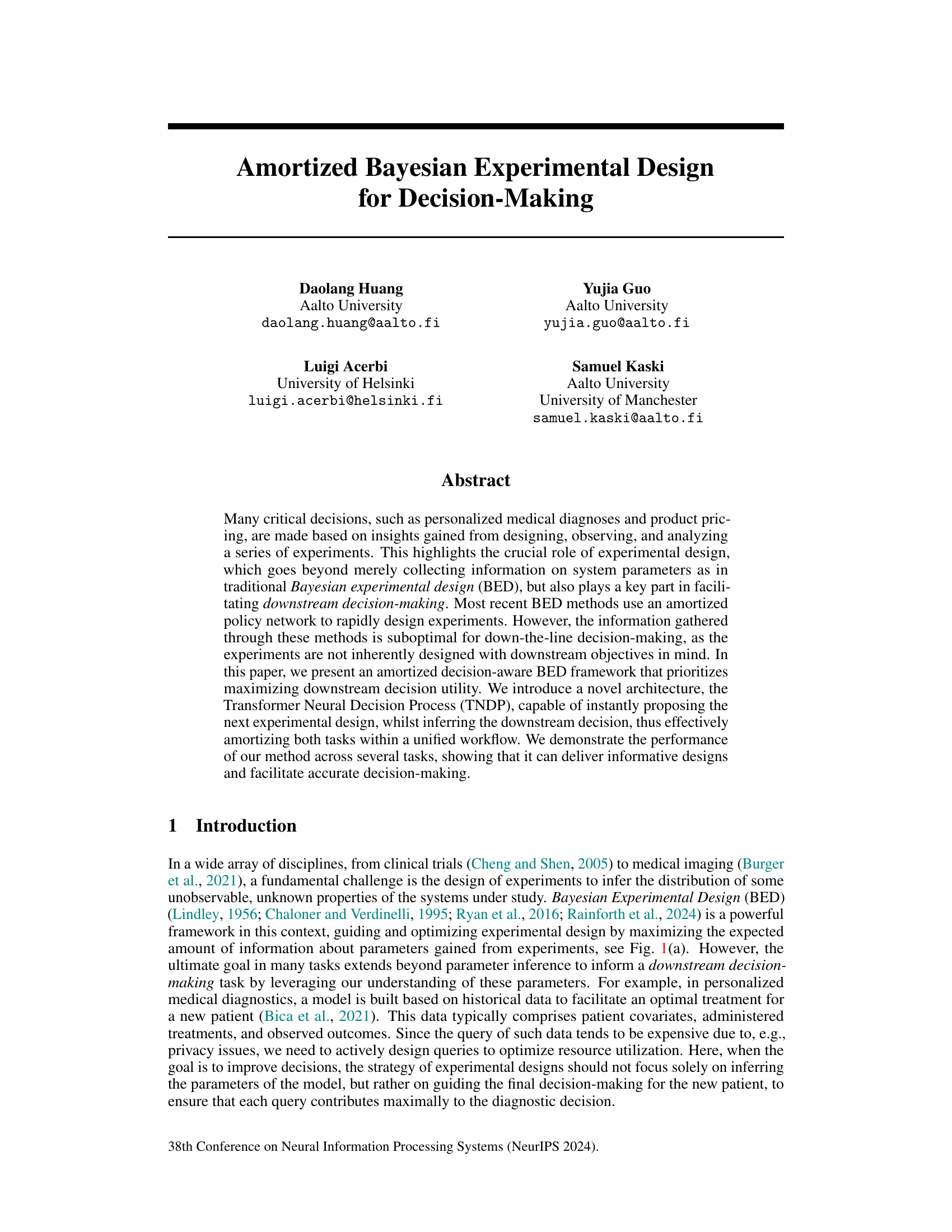

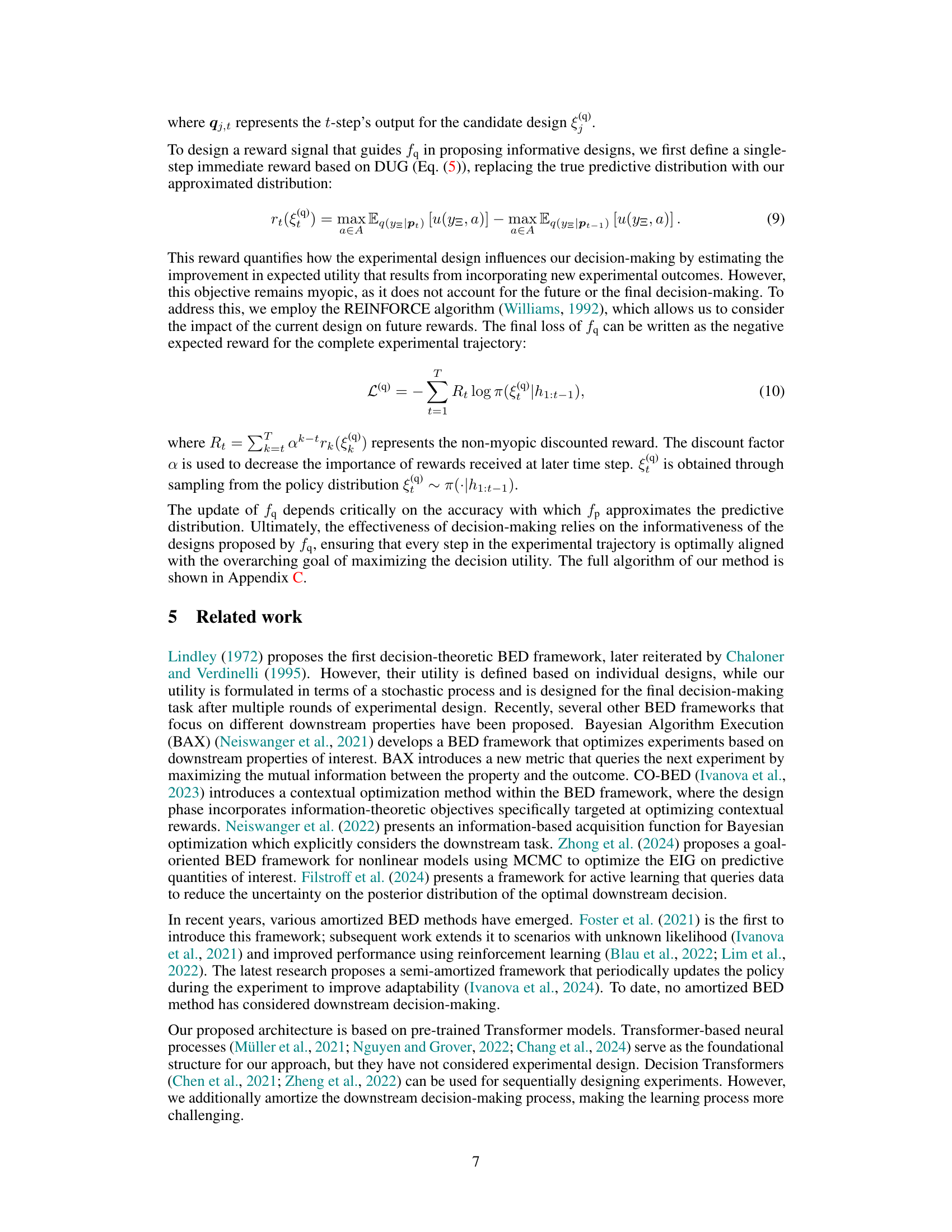

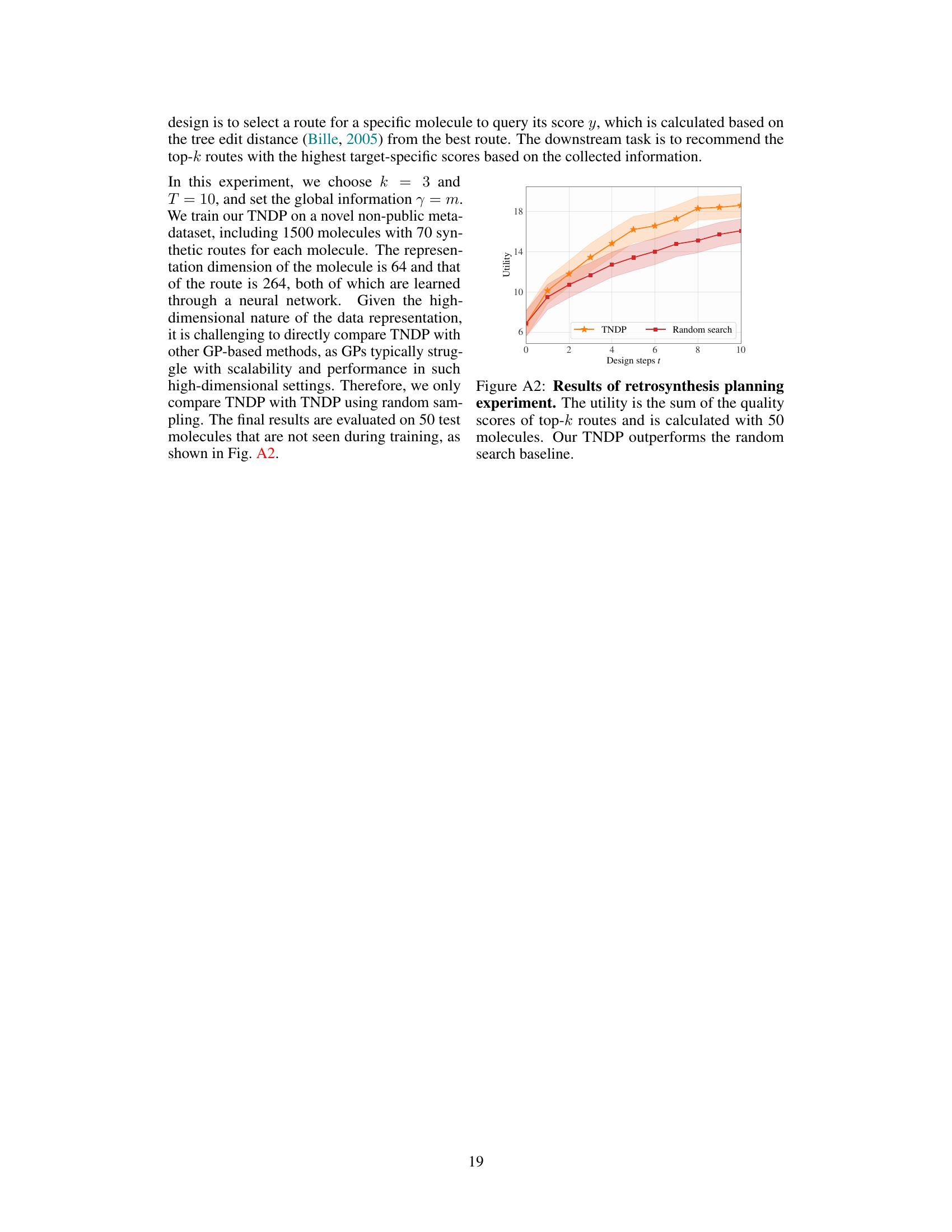

This figure compares three Bayesian Experimental Design (BED) workflows: Traditional BED, Amortized BED, and the authors’ proposed Decision-aware Amortized BED. Traditional BED involves iterative optimization, experimentation, and Bayesian inference. Amortized BED streamlines this with a policy network for quick design generation. The authors’ approach further improves upon Amortized BED by integrating downstream decision utility into the training process, leading to more effective decision-making.

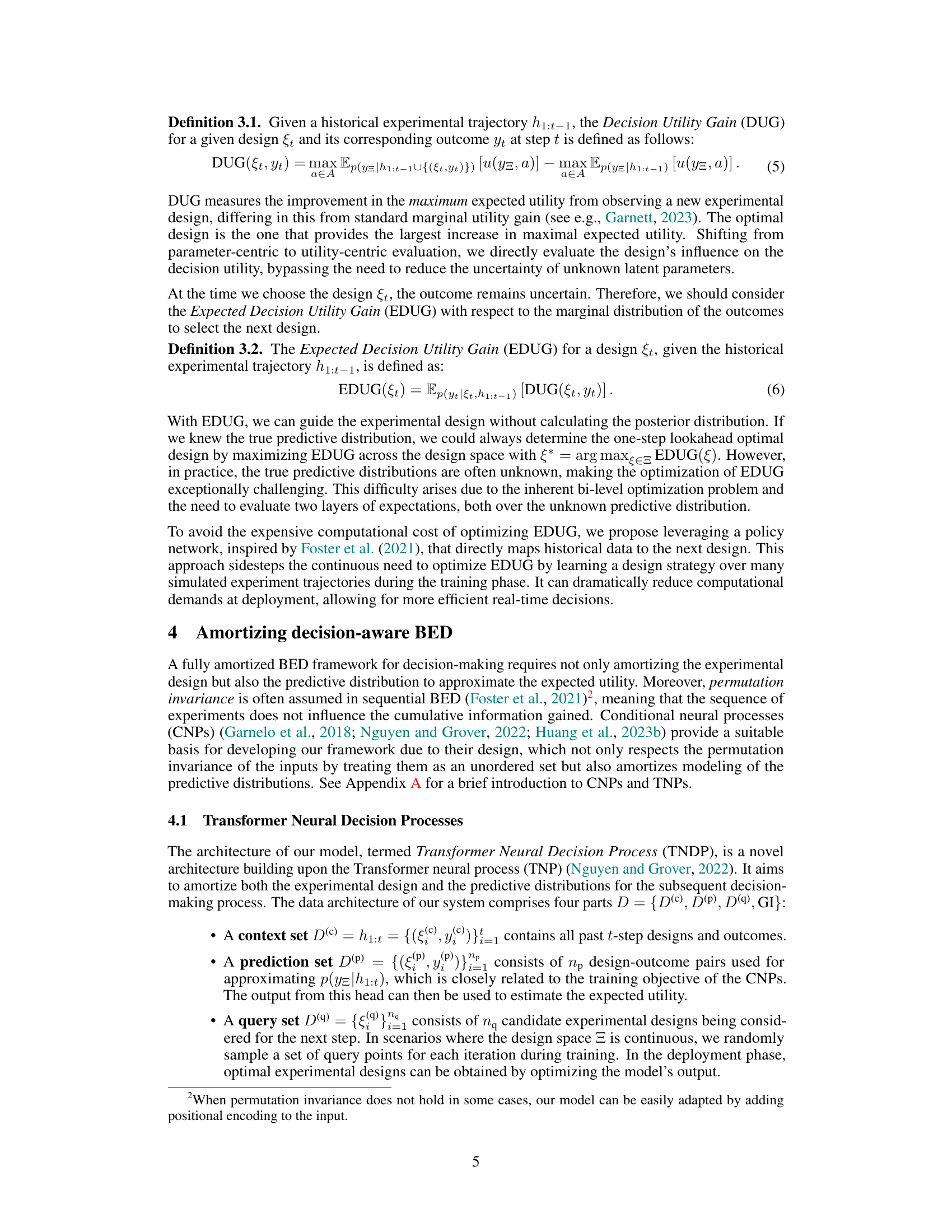

This table compares the computational cost of different methods used for decision-aware active learning. It shows the acquisition time (time to compute the next design) and total time (time to complete 10 rounds of design) for various methods including GP-RS, GP-US, GP-DUS, T-EIG, D-EIG, and TNDP (the authors’ method). The results highlight that TNDP, being fully amortized, requires significantly less time than other methods which depend on iterative optimization and/or GP updates. The values reported are means and standard deviations across 10 independent runs.

In-depth insights#

Decision-Aware BED#

The concept of ‘Decision-Aware BED’ presents a significant advancement in Bayesian Experimental Design (BED). Traditional BED methods primarily focus on efficient parameter estimation, neglecting the downstream impact on decision-making. Decision-Aware BED directly incorporates the utility of the final decision into the experimental design process, thereby optimizing experiments not just for information gain but for improved decision outcomes. This crucial shift aligns the design process with the ultimate goal, leading to more effective and efficient decision-making. A key challenge is to balance exploration (learning about parameters) with exploitation (improving decisions). Decision-Aware BED cleverly tackles this through a novel approach, potentially utilizing techniques like reinforcement learning to guide the design towards maximizing expected utility. Amortization strategies play a key role, allowing for efficient, real-time design suggestions without the computational cost of traditional BED. This framework enhances various applications, like personalized medicine and product pricing, where timely and effective decisions are paramount.

TNDP Architecture#

The Transformer Neural Decision Process (TNDP) architecture is a novel design that cleverly integrates a policy network for generating experimental designs and a predictive distribution network for downstream decision-making. Its dual-headed structure enables simultaneous proposal of experiments and prediction of outcomes, streamlining the decision-making process. The use of a Transformer block is key, allowing for the efficient processing of sequential experimental data through self-attention mechanisms, capturing complex relationships between designs and outcomes. This contrasts with earlier amortized methods which addressed only one aspect, resulting in suboptimal designs. The TNDP’s ability to rapidly propose designs and predict outcomes via a single forward pass drastically improves efficiency, especially crucial in time-sensitive settings. Furthermore, the model’s design implicitly enforces permutation invariance, which allows it to handle variable length sequences of experiments. Finally, a non-myopic training objective maximizes long-term decision utility, moving beyond short-sighted greedy approaches that only optimize immediate gains. This holistic design makes TNDP a significant advancement in amortized Bayesian experimental design for decision-making.

Amortization Methods#

Amortization methods in machine learning are crucial for improving efficiency and scalability. They aim to reduce computational cost by pre-computing expensive operations, allowing for faster inference during deployment. Instead of repeatedly calculating the same values for individual instances, amortized methods learn a general function that maps inputs to outputs, effectively spreading the computational burden across numerous examples. This significantly reduces computation time, particularly useful in real-time applications or situations with extensive data. A key challenge is balancing generalization with accuracy. A model that generalizes too broadly may compromise its accuracy on specific cases, while a model too narrowly focused may fail to capture the underlying patterns in the data and lose its computational advantage. Successful amortization hinges on careful design of the architecture and the training process, requiring an optimal balance between model capacity and regularization to avoid both overfitting and underfitting. The effectiveness of amortized methods heavily depends on the data quality and distribution. The quality and representativeness of the training data directly impact the accuracy and applicability of the learned amortized function. Moreover, different tasks may require different approaches to amortization, as some problems lend themselves more readily to this strategy than others. This often necessitates task-specific adaptations of the method to achieve optimal results.

Experimental Results#

The experimental results section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims and demonstrating the efficacy of the proposed methods. A strong experimental results section should clearly present the methodology, including the datasets used, evaluation metrics, and experimental setup. Detailed descriptions of experimental design choices are important to understand the validity of the findings and to allow for reproducibility. The results themselves should be presented concisely and effectively, often using tables and figures to visually represent complex data. Statistical significance tests are essential to confirm that observed results are not due to random chance and to gauge the reliability of the findings. The discussion of results should go beyond simply reporting the numbers and analyze the implications of the findings, including comparisons to existing work, limitations, and potential future research directions. Transparency and reproducibility are key; the reader should have sufficient information to independently validate or replicate the results. A thoughtful presentation of experimental results provides crucial evidence for evaluating the overall quality and contribution of the research paper.

Future Work#

The authors acknowledge limitations inherent in their current approach and propose several avenues for future research. Addressing the reinforcement learning aspect of their query head, which uses a basic REINFORCE algorithm susceptible to instability, is prioritized. They suggest employing more advanced RL methods like PPO to improve stability and potentially enhance performance. The quadratic complexity of the Transformer architecture, which poses scalability challenges for large query sets, is identified as another area for improvement. The authors envision exploring alternative network architectures or novel methods to mitigate this computational bottleneck. Finally, extending the model’s capabilities beyond the current assumption of fixed-step length and incorporating the handling of infinite horizon scenarios is a stated goal. This would greatly broaden the applicability of their framework for real-world decision-making tasks. The authors clearly recognize that these are significant challenges and that successfully addressing them would substantially advance the field of decision-aware Bayesian Experimental Design.

More visual insights#

More on figures

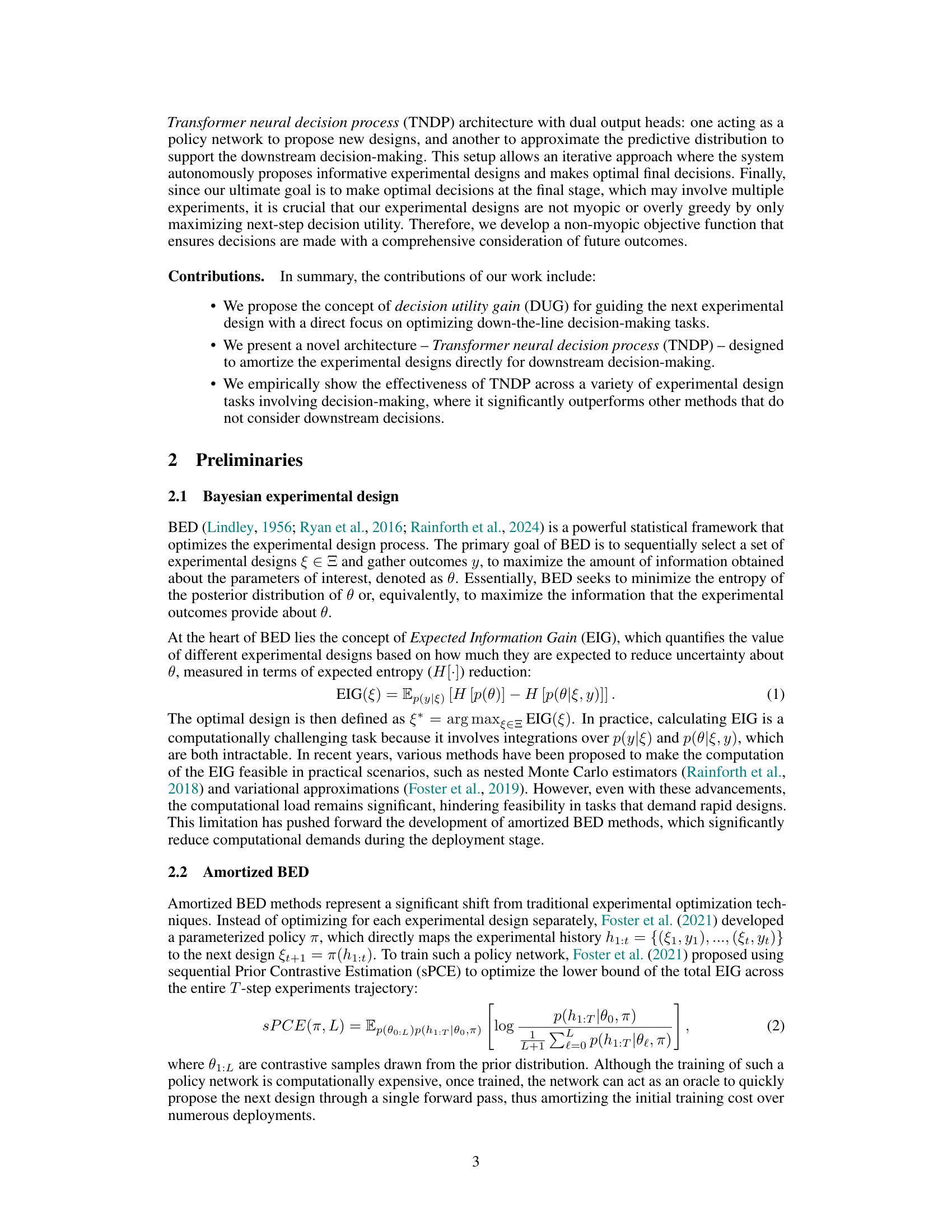

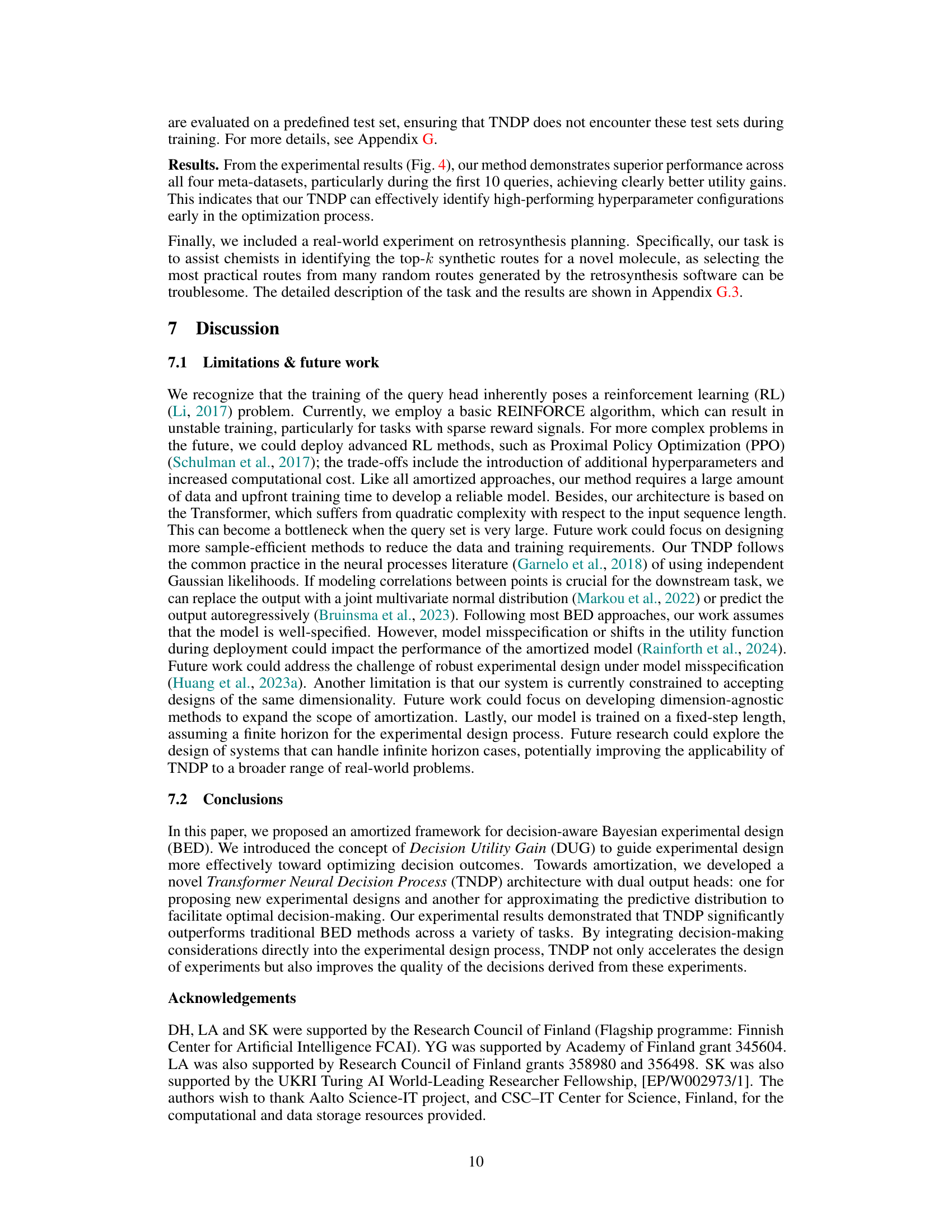

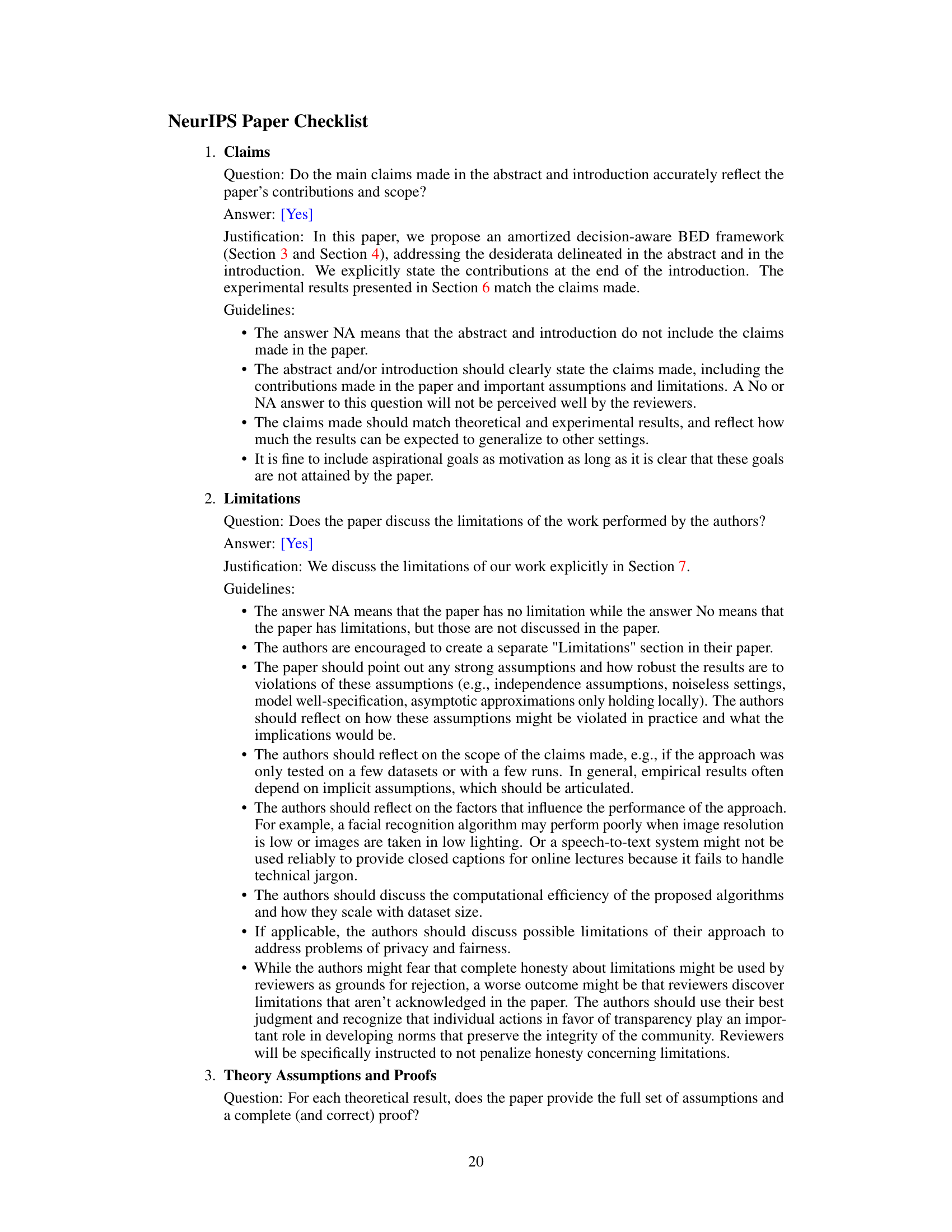

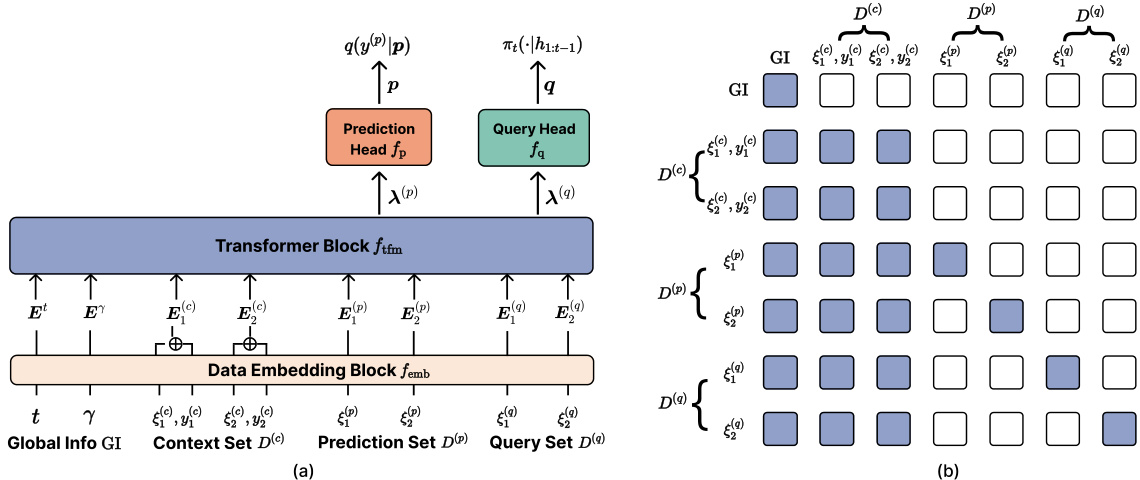

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Transformer Neural Decision Process (TNDP). Panel (a) shows a high-level overview of the model’s components: a data embedding block, a transformer block, a prediction head, and a query head. The different input sets (context, prediction, and query) are highlighted, along with the global information. Panel (b) depicts the attention mask used within the transformer block, showing which parts of the input can attend to each other during processing. The colors in the mask indicate the permitted connections within the self-attention mechanism.

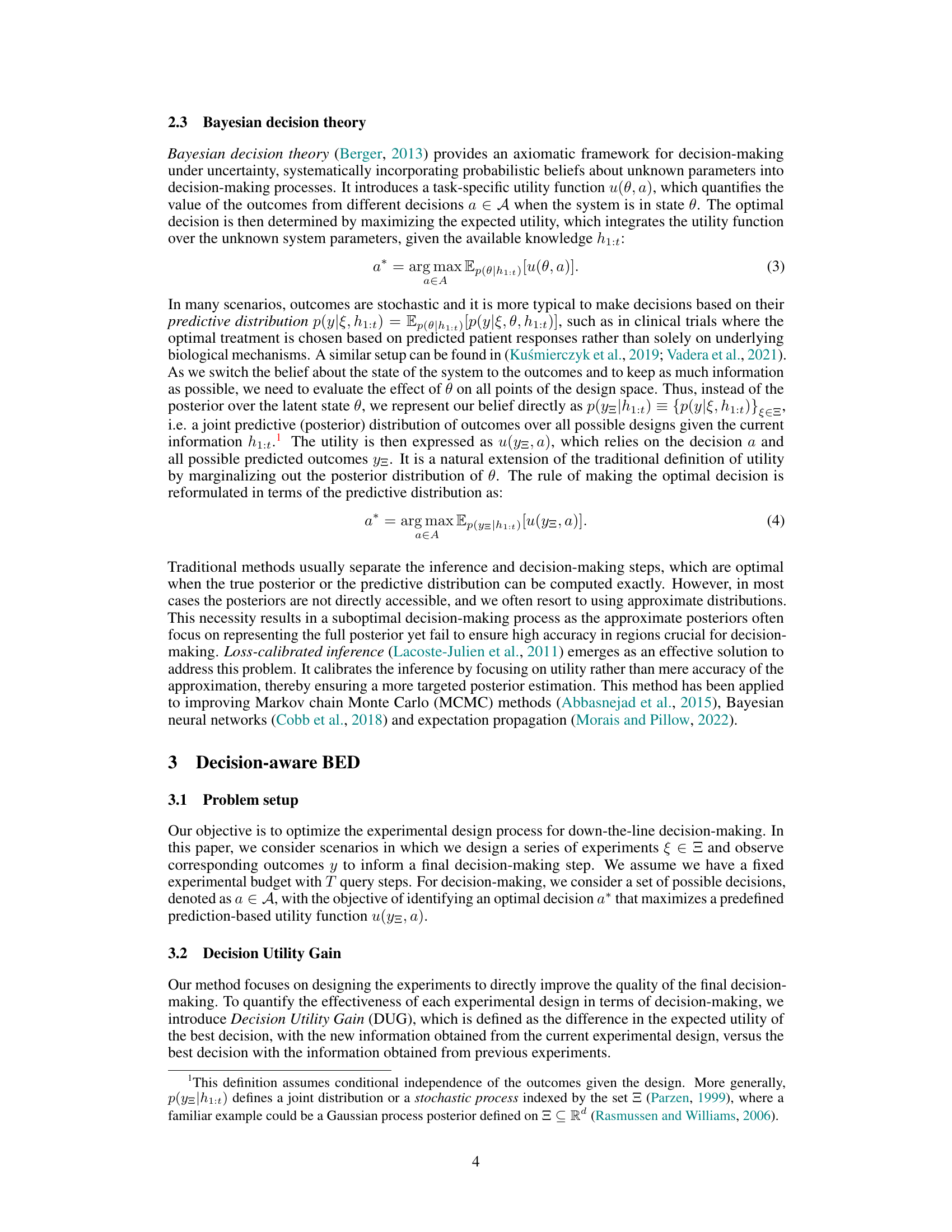

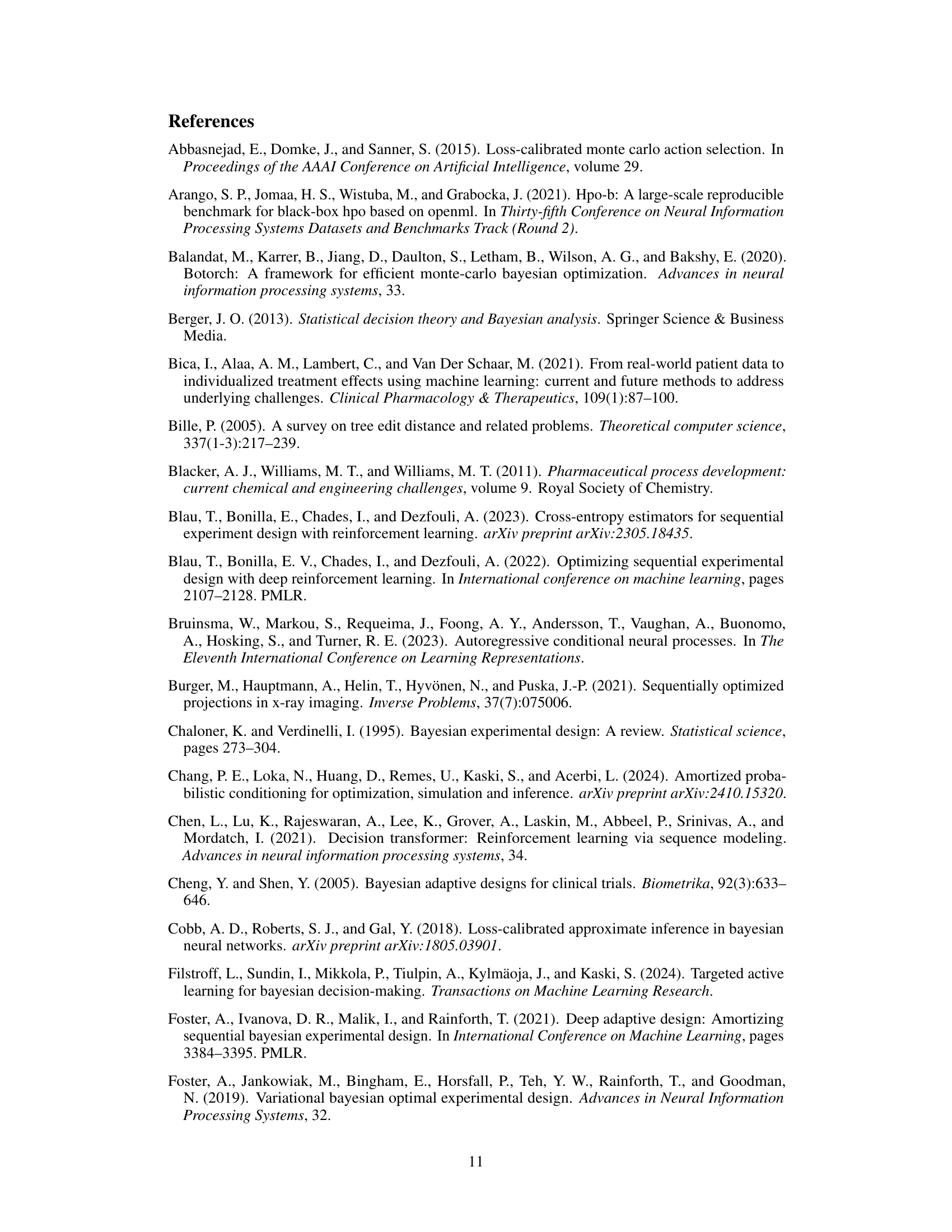

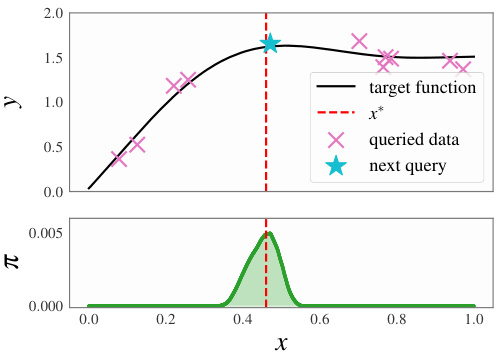

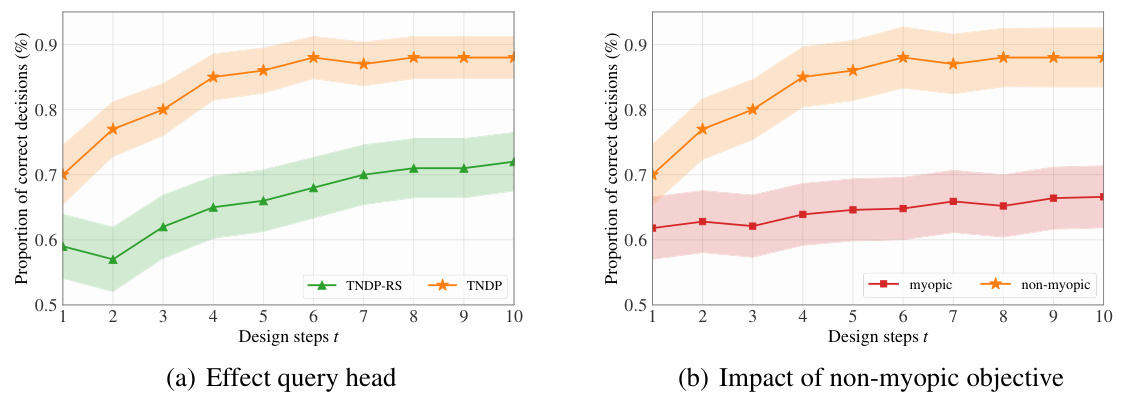

This figure shows the results of two experiments: 1D synthetic regression and decision-aware active learning. The top panel (a) illustrates the 1D synthetic regression. It shows the true underlying function (black line), the initial known data points (magenta crosses), the target point (red dashed line), and the next point selected for querying by the model (blue star). The bottom panel displays the probability distribution over the next point to be queried, with the highest probability density around the target point. The second panel (b) displays the results of the decision-aware active learning. It shows that the proposed TNDP method outperforms other algorithms in terms of decision accuracy over 100 test points.

This figure shows the results of two experiments: 1D synthetic regression and decision-aware active learning. The synthetic regression experiment (a) illustrates how the model selects informative query points to approximate an unknown function, showing the true function, initial data points, and the next query point selected by the model. The decision-aware active learning experiment (b) compares the performance of TNDP to other methods on a 100-point test set across different acquisition steps, demonstrating TNDP’s superior performance in making accurate decisions.

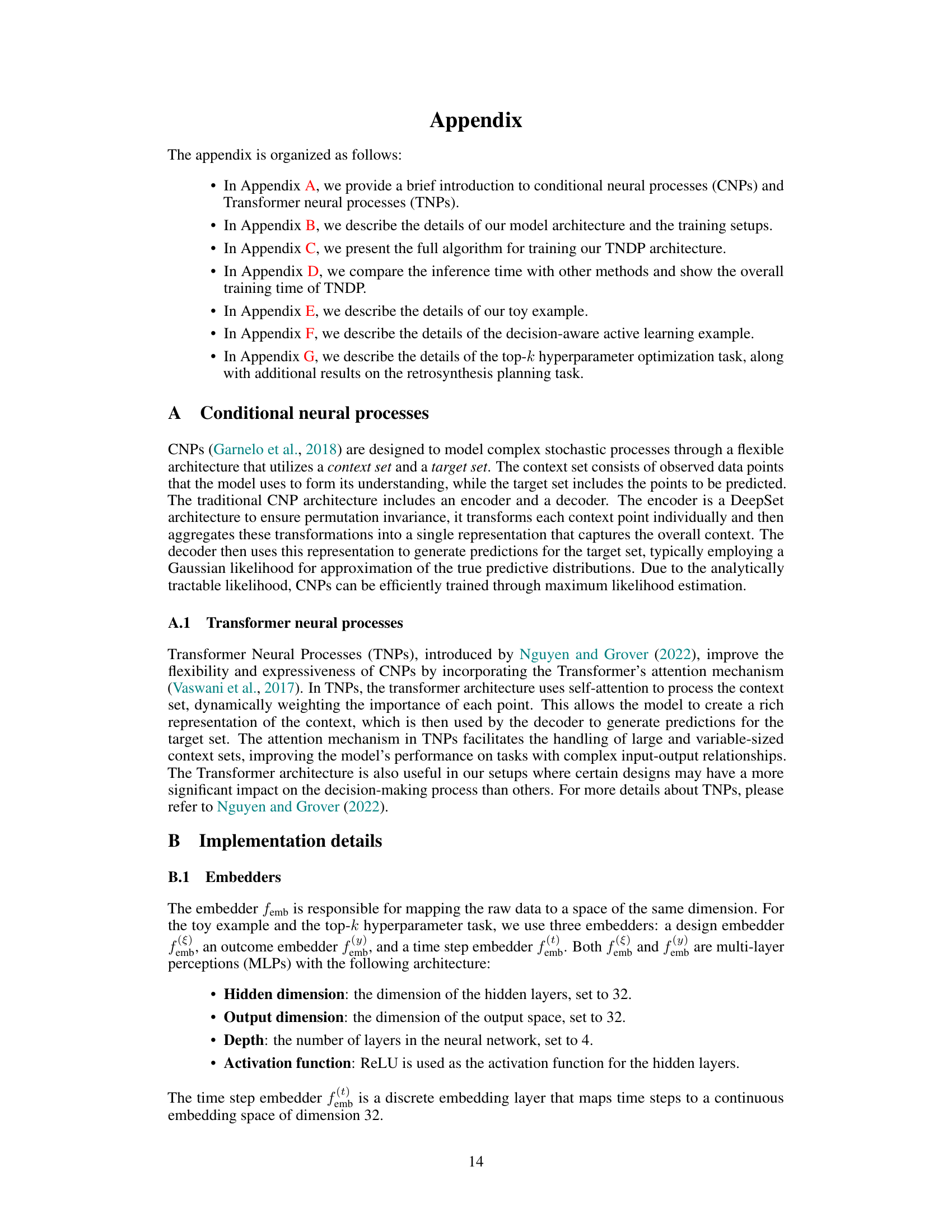

The figure shows the results of the Top-k hyperparameter optimization (HPO) experiments. Four different meta-datasets (ranger, rpart, svm, xgboost) are used, with the average utility across all test sets being calculated for each. Error bars represent the standard deviation across five runs. The results demonstrate that TNDP consistently outperforms other methods in terms of utility.

This figure shows the results of two experiments: 1D synthetic regression and decision-aware active learning. The synthetic regression experiment demonstrates how the TNDP model selects informative query points to accurately predict the value at a target point. The decision-aware active learning experiment compares the performance of the TNDP model against other methods in a classification task, highlighting its superior performance in terms of the proportion of correct decisions.

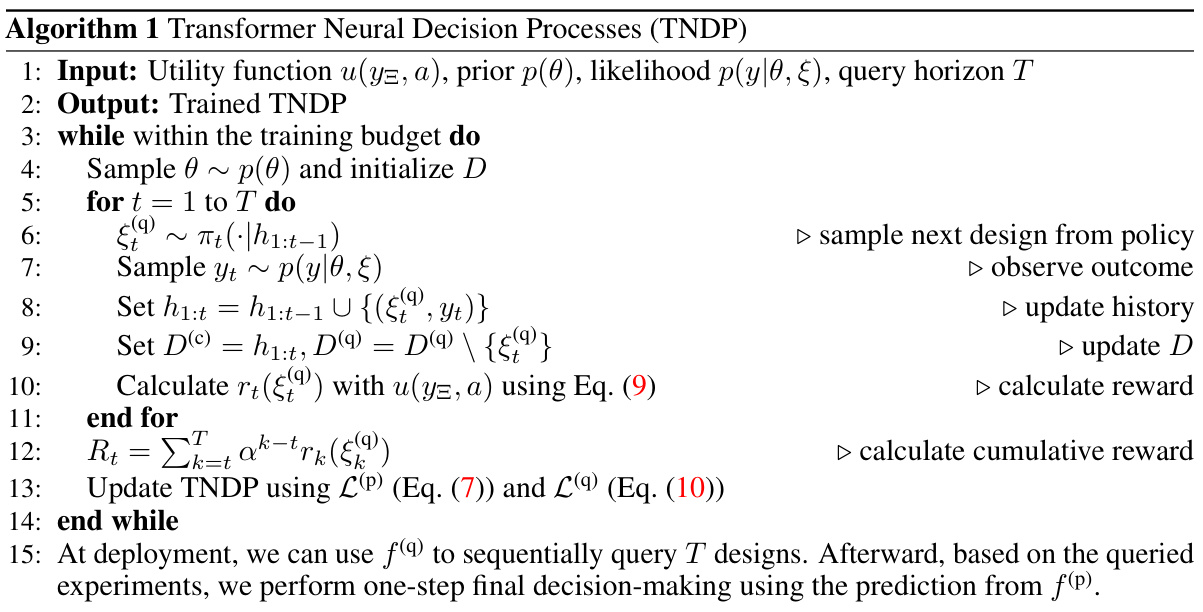

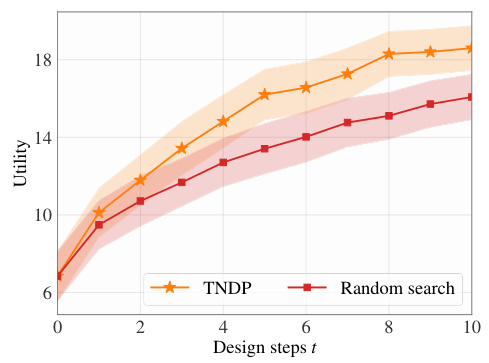

This figure shows the results of a retrosynthesis planning experiment. The task was to identify the top-k synthetic routes for a novel molecule using a decision-aware amortized Bayesian experimental design framework called TNDP. The results compare the TNDP approach to a random search baseline, showing that TNDP achieved significantly higher utility (sum of quality scores for the top-k routes) across 10 design steps. The error bars represent standard deviation across 50 test molecules. This demonstrates the effectiveness of TNDP in guiding the design process toward better decision-making outcomes.

Full paper#