↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Federated learning (FL) is rapidly advancing, but visualizing high-dimensional data collaboratively across distributed devices without direct data sharing remains a significant challenge. Existing neighbor embedding (NE) techniques, which are highly effective at visualizing data, are difficult to adapt to the FL setting due to the need to compute loss functions across all data pairs. This necessitates sharing data or using reference datasets, both of which violate the privacy-preserving essence of FL.

This paper introduces FEDNE, a novel solution that leverages the FEDAVG framework. FEDNE cleverly integrates contrastive NE with a surrogate loss function, mitigating the lack of inter-client repulsion. A data-mixing strategy augments local data, enhancing local neighborhood graph accuracy. Experiments show FEDNE’s effectiveness in preserving neighborhood structures and enhancing alignment across clients, outperforming baseline methods on various datasets. This is highly significant for data visualization in privacy-sensitive FL scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in federated learning and dimensionality reduction. It tackles the challenge of visualizing high-dimensional data distributed across multiple clients without compromising privacy, a critical need in many applications. The proposed method, FEDNE, offers a novel approach to address this challenge, opening doors for further research in privacy-preserving data visualization techniques and their application to various real-world problems. Its effectiveness has been demonstrated through extensive experiments, making it a valuable resource for those working in related fields.

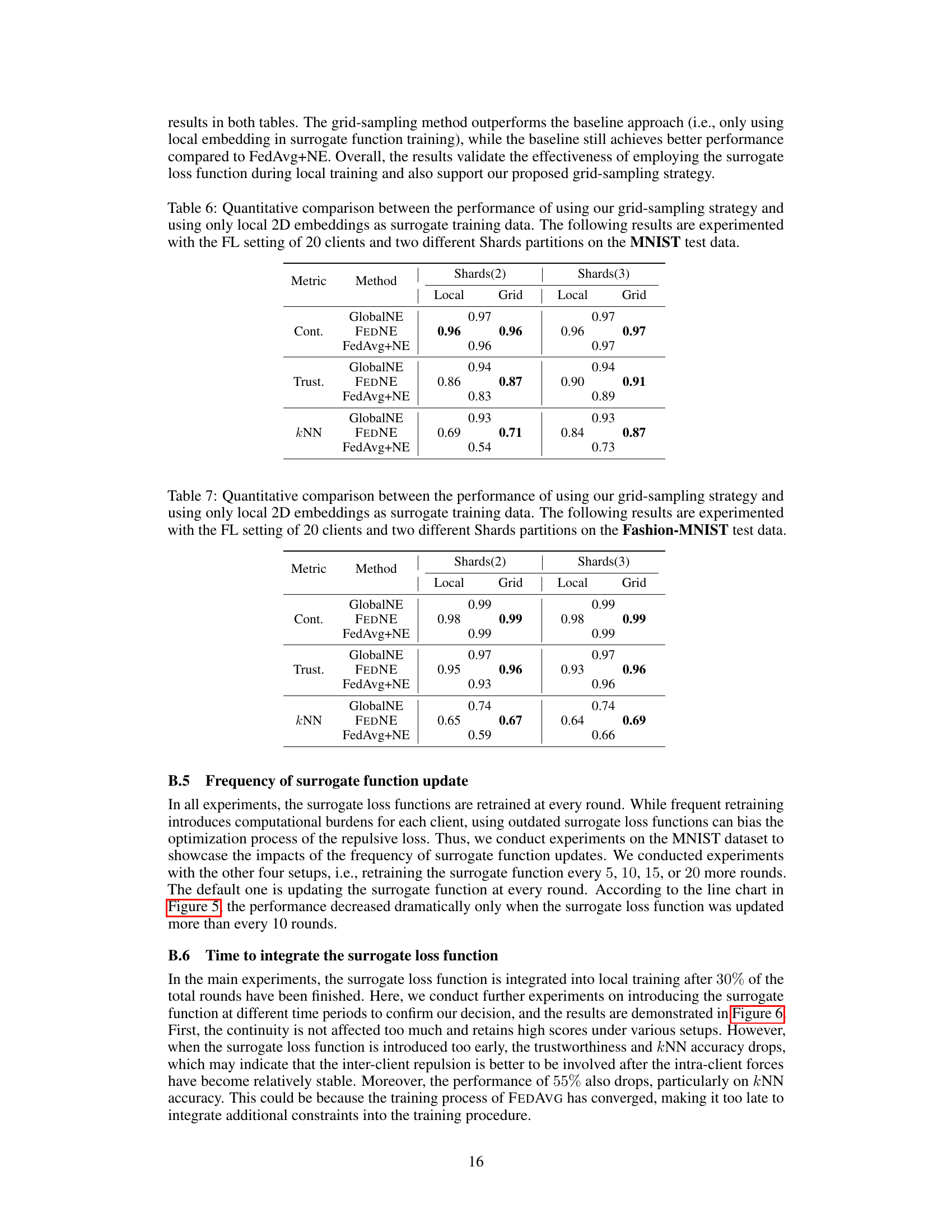

Visual Insights#

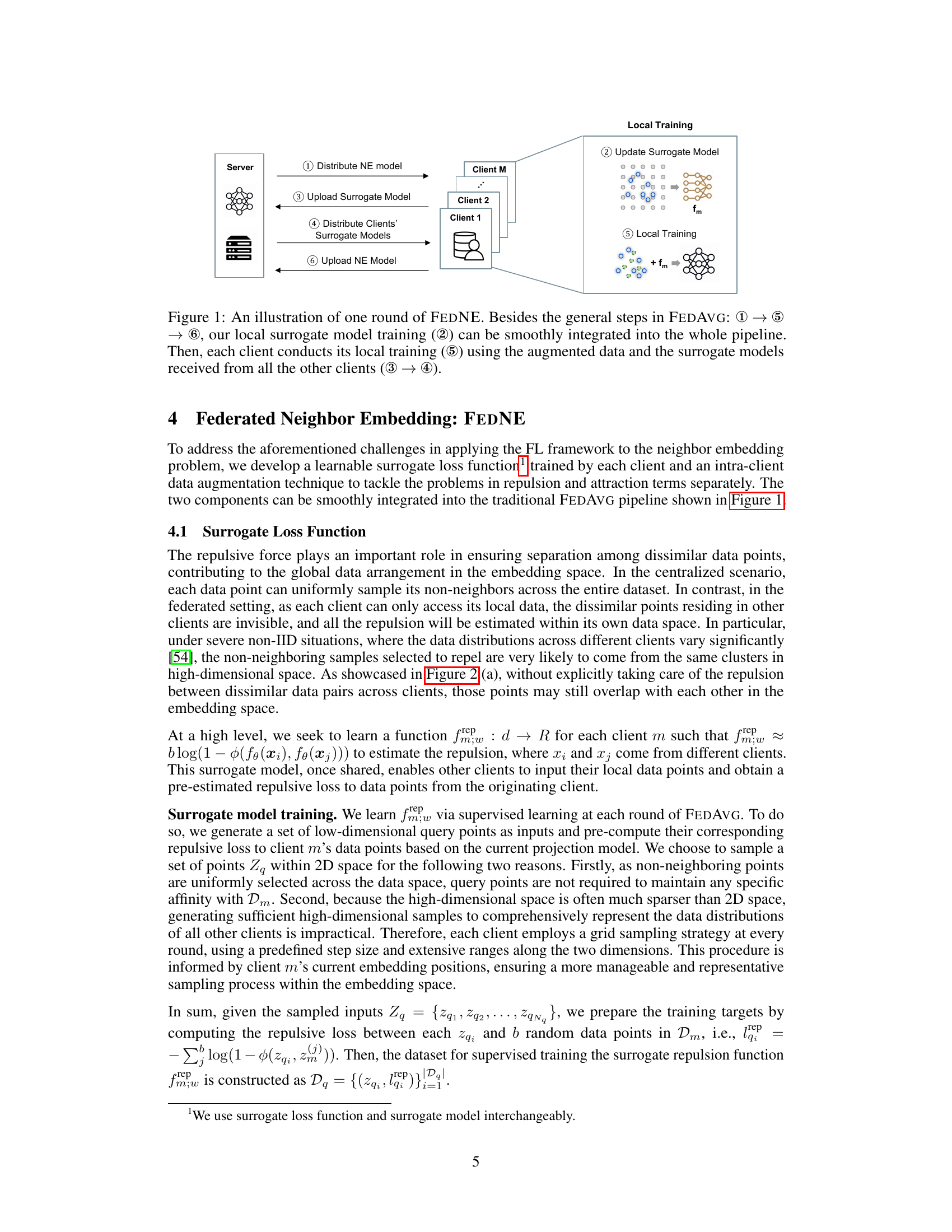

This figure illustrates a single round of the FEDNE algorithm. It shows the interaction between the server and multiple clients involved in federated neighbor embedding. The steps highlight the flow of information: the server distributes the neural network model, each client updates its local surrogate model and then trains its local model using augmented data incorporating surrogate models from other clients, then uploads its updated local model to the server, finally, the server aggregates the models.

This table presents the characteristics of the four benchmark datasets used in the paper’s experiments (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, scRNA-Seq, and CIFAR-10). For each dataset, it lists the number of classes, the number of training and testing samples, the number of clients (M) used in the federated learning simulations (with two different settings of the number of clients), and the dimensionality of the data points. This information is crucial for understanding the experimental setup and the scale of the federated learning tasks.

In-depth insights#

Federated Neighbor Embedding#

Federated learning (FL) presents a unique challenge for dimensionality reduction techniques like neighbor embedding (NE), as NE requires computing pairwise distances across all data points. A federated neighbor embedding (FNE) approach aims to address this by enabling collaborative model training across distributed participants without directly sharing data. This typically involves training a shared NE model, but the challenge lies in handling the lack of inter-client information. To overcome this, techniques such as surrogate loss functions and data-mixing strategies are often implemented. Surrogate models approximate inter-client repulsive forces, while data mixing aims to mitigate the biases caused by local data only being available. The effectiveness of any FNE method hinges on its ability to preserve neighborhood structures while enforcing global alignment in the low-dimensional embedding space, striking a balance between local data fidelity and global consistency. Privacy remains a critical consideration, as strategies to minimize direct data sharing are essential.

Surrogate Loss Function#

The concept of a ‘Surrogate Loss Function’ in federated learning addresses a crucial challenge: the inability to directly compute pairwise distances between data points residing on different clients. This function approximates the inter-client repulsion loss, a key component in neighbor embedding algorithms for dimensionality reduction that’s usually calculated using global data. By training a surrogate model at each client to represent its local repulsive forces and sharing these models, FEDNE sidesteps the need for sharing raw data while preserving the neighborhood structure in the global embedding space. This approach cleverly compensates for the lack of direct inter-client interaction, improving embedding alignment and making federated dimensionality reduction more effective. The design of the surrogate model, including its training method (supervised learning on generated query points), directly impacts the accuracy and efficiency of the overall FEDNE algorithm. Successfully approximating the repulsive force is critical for the separation of dissimilar data points across clients, a key feature lacking in naive federated neighbor embedding implementations.

Data Augmentation#

Data augmentation is a crucial technique in machine learning, especially when dealing with limited datasets. The paper cleverly addresses the challenges of data scarcity in federated learning by introducing an ‘intra-client data mixing’ strategy. This approach tackles the problem of biased local kNN graphs, which often lead to inaccurate neighbor representations due to data partitioning among clients. By interpolating between data points and their neighbors within each client, the method effectively increases the diversity of local data. This is particularly important in non-IID settings where data distribution across clients is uneven. The augmentation enhances the robustness of local kNN graphs by simulating the presence of potential neighbors residing on other clients, thus improving the overall accuracy of the model. The method’s simplicity and ease of implementation are further strengths, making it a valuable tool for improving federated neighbor embedding and related techniques.

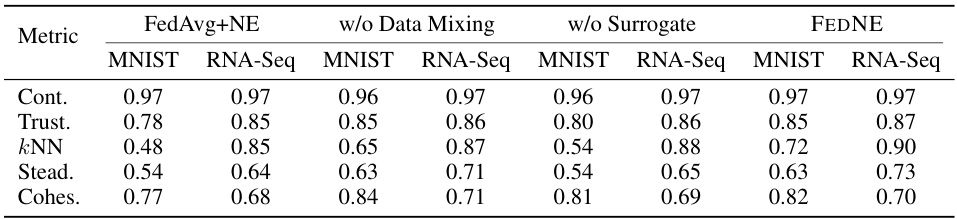

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model to assess their individual contribution. In the context of a federated neighbor embedding (FNE) model, this would involve removing elements like the surrogate loss function or the data augmentation strategy. By observing the impact on performance metrics such as trustworthiness, continuity, and k-NN accuracy, researchers can quantify the impact of each component. A well-designed ablation study should reveal which components are essential for achieving good performance and highlight potential areas for improvement or simplification of the FNE architecture. The study also provides crucial insights into the interplay between different components and justifies the design choices made by highlighting the unique contributions of each component. The results of the ablation study can guide future work in optimizing the FNE model or developing alternative FNE techniques. The results in this section strengthen the claims by demonstrating the impact of the introduced methods in the FNE setting.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore several avenues. Extending the framework to handle non-IID data distributions more robustly is crucial. Currently, the effectiveness relies on the surrogate models’ capacity to approximate inter-client repulsion; however, this approximation might be challenged under extremely non-IID scenarios. Further investigation into more sophisticated data augmentation strategies, possibly incorporating techniques like GANs to generate synthetic data that bridges the gap between client data distributions, should be considered. Another promising area is improving the efficiency of the surrogate model training and communication. The current approach adds computational overhead; exploring model compression or more efficient aggregation techniques would significantly enhance the scalability and practicality of FEDNE. Finally, a rigorous privacy analysis of the FEDNE framework is needed to quantify the privacy risks associated with sharing the surrogate models. This will establish the balance between the benefits of improved embedding quality and the potential privacy vulnerabilities. This thorough analysis could potentially lead to the development of privacy-preserving modifications, strengthening the framework’s resilience and acceptability in privacy-sensitive applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates one round of the FEDNE algorithm. It shows how the FEDAVG framework is extended with a surrogate model training step. Each client trains a local surrogate model to approximate repulsion loss, which is then shared with other clients. This shared information helps to compensate for the lack of direct data sharing between clients during local training. FEDAVG steps 1 to 6 represent the distribution and aggregation of the central model parameters.

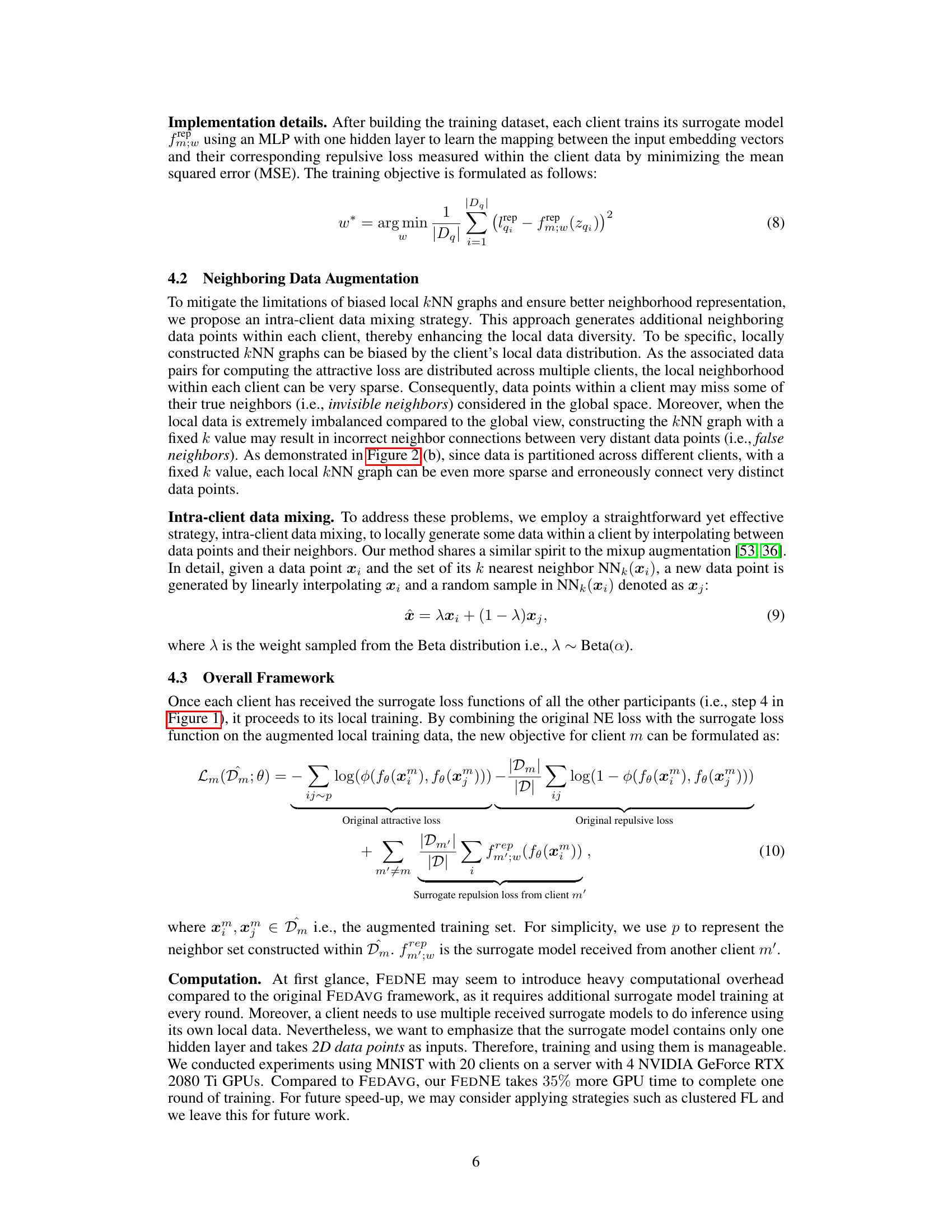

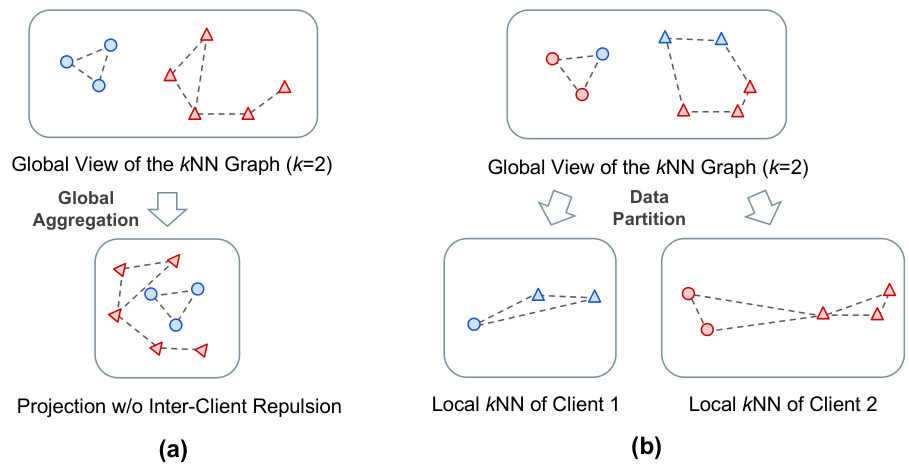

This figure uses two toy examples to illustrate the challenges of applying federated learning to neighbor embedding. The left panel (a) shows that without considering the repulsive forces between dissimilar data points across different clients, the resulting embedding may have overlapping points from different clients in the global embedding space. The right panel (b) shows that because data is partitioned across different clients, the locally constructed kNN graphs may be biased, leading to false-neighbor connections (connecting distant points) and invisible neighbors (missing true neighbors).

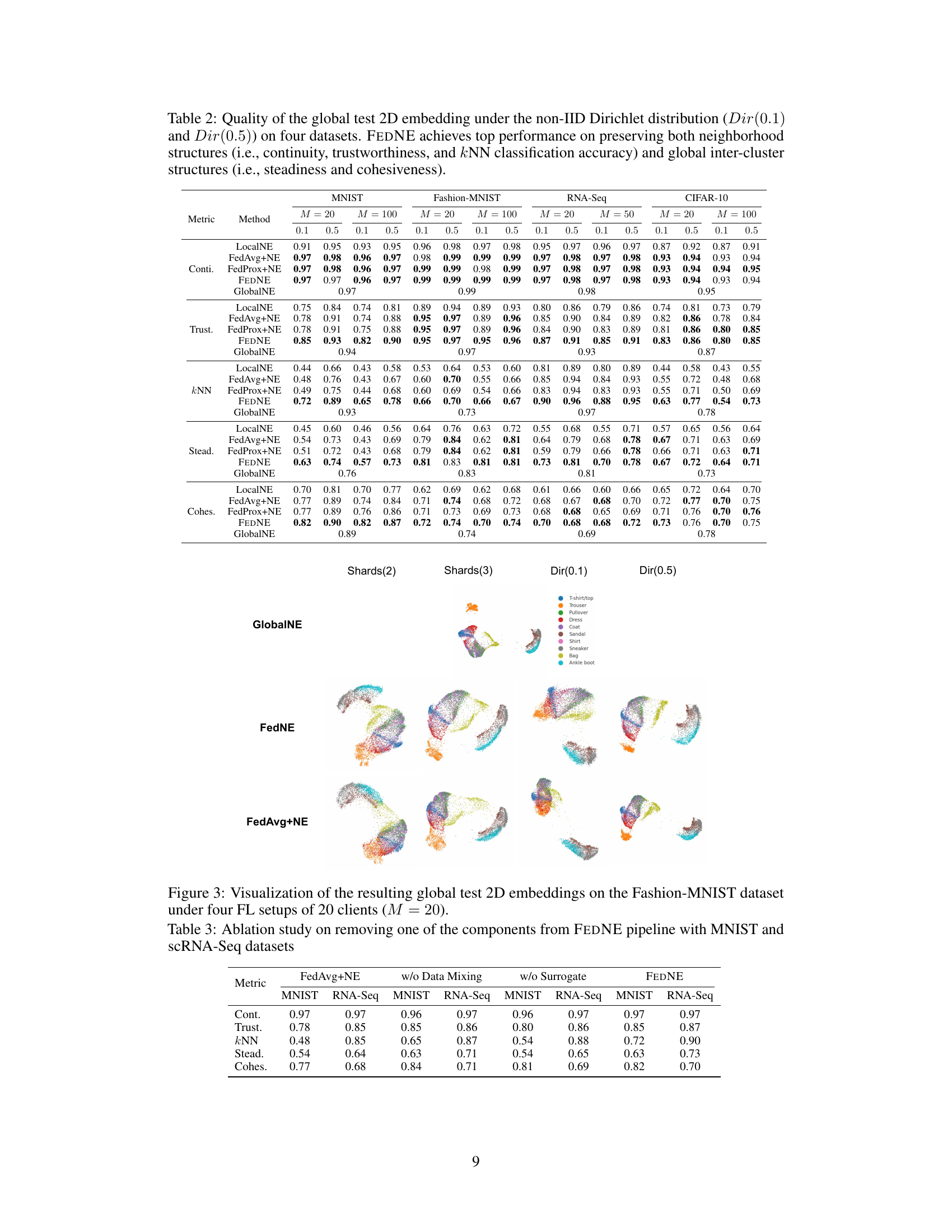

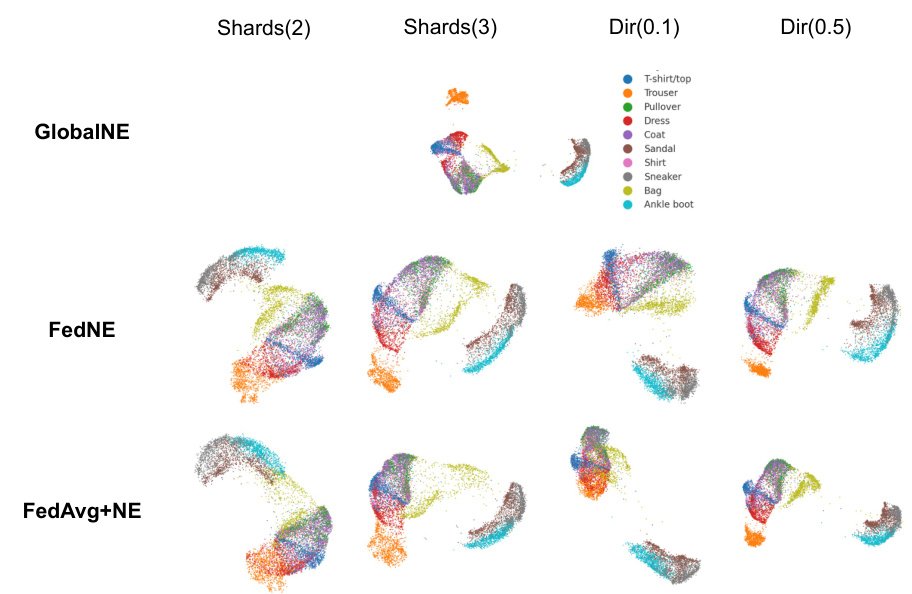

This figure visualizes the 2D embeddings obtained from four different federated learning (FL) methods on the Fashion-MNIST dataset. The methods compared are GlobalNE (a centralized approach using all data), FEDNE (the proposed method), and two baselines, FedAvg+NE and FedProx+NE. The visualization shows the distribution of data points in the 2D embedding space for different classes, and for four different non-IID data partitioning strategies, and the effectiveness of the proposed FEDNE method in preserving the data’s original structure across different clients.

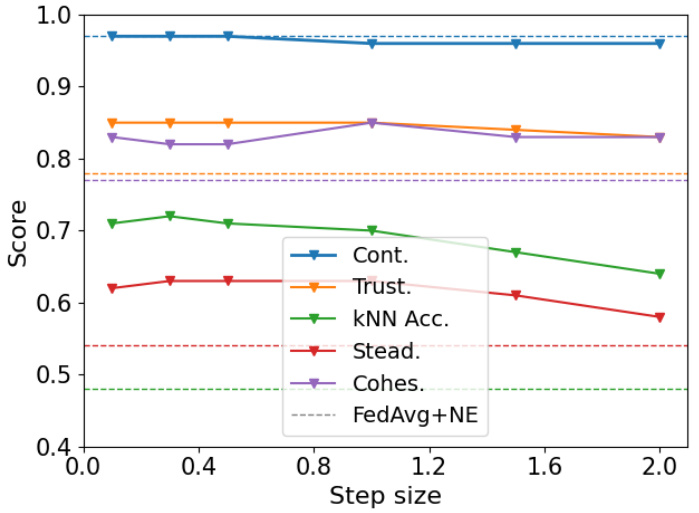

The figure shows the experimental results on different step sizes used for grid sampling during the training of surrogate models. The experiments were performed using the Dirichlet(0.1) setting on the MNIST dataset with 20 clients. The default step size used in the main paper was 0.3. The results indicate that the performance of the proposed FEDNE method remains stable when the step size is below 1.0, demonstrating its robustness to variations in this hyperparameter.

This figure shows the impact of different retraining frequencies of the surrogate function on the performance of the FEDNE model. The x-axis represents the number of rounds, while the y-axis shows different metrics such as continuity, trustworthiness, and kNN accuracy. The results show that the performance of the FEDNE model is relatively stable when the surrogate loss function is updated frequently (every round), but it begins to decrease when the update frequency is reduced (every 5, 10, 15, or 20 rounds).

This figure shows how the performance of different metrics (continuity, trustworthiness, and kNN accuracy) changes when the surrogate function is updated at different frequencies during the training process. The x-axis represents the percentage of total training rounds at which the surrogate function is updated, while the y-axis represents the values of the metrics. The results suggest that frequent updates (every round) are beneficial but excessive updates can lead to performance degradation.

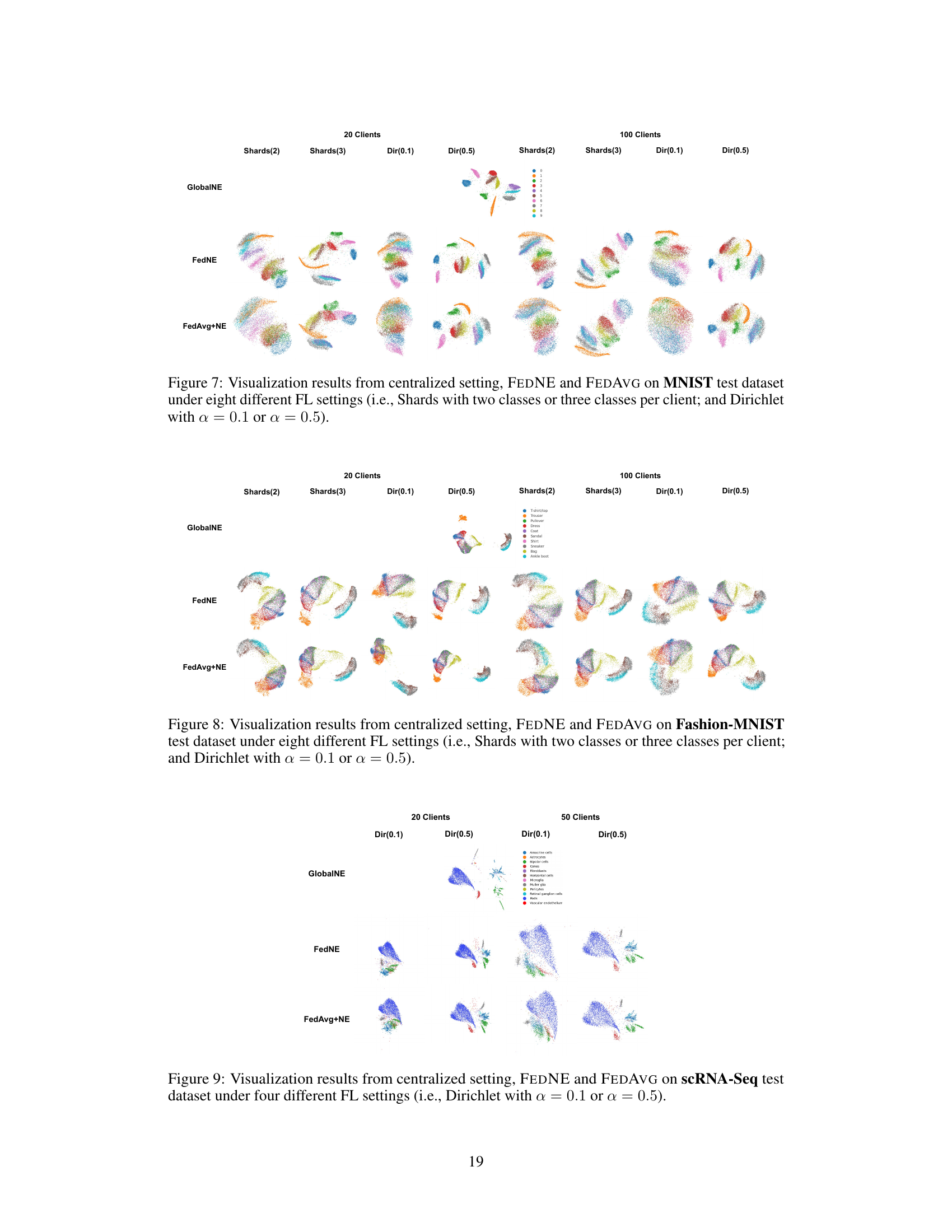

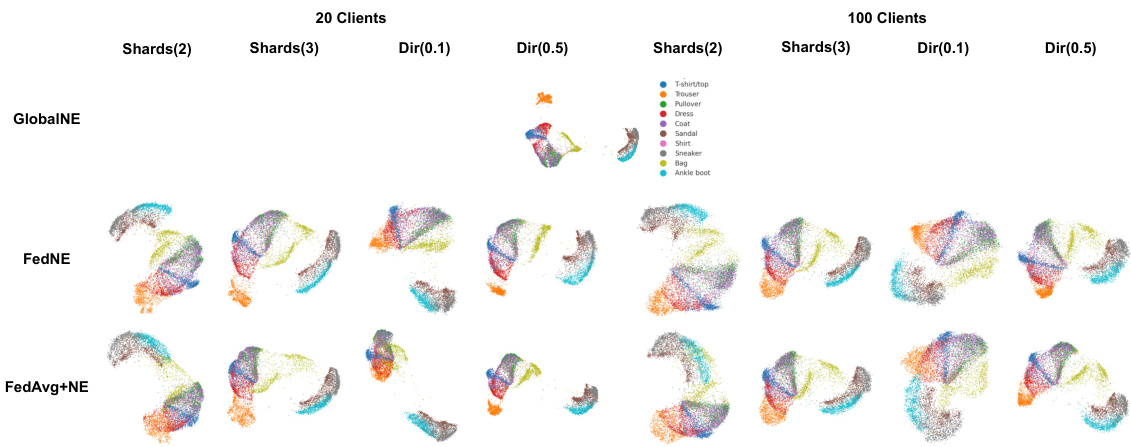

This figure compares the visualization results of the MNIST test dataset using three different methods: GlobalNE (centralized setting), FEDNE, and FedAvg+NE. The comparison is shown across eight different federated learning (FL) settings, which vary in data distribution among clients. Four settings use the ‘Shards’ approach, dividing data so each client has two or three classes. Another four settings use the ‘Dirichlet’ distribution approach, creating varied non-IID data. The visualization demonstrates the effect of each method under different data distributions.

This figure visualizes the 2D embeddings generated by four different federated learning (FL) methods on the Fashion-MNIST dataset. The methods compared are FEDNE (the proposed method), FedAvg+NE, and FedProx+NE (baseline methods), and GlobalNE (a centralized approach serving as a performance upper bound). The visualization shows the resulting embeddings for 20 clients under different data distribution scenarios (Dir(0.1) and Dir(0.5)). The figure helps to illustrate how well each method preserves the neighborhood structure and separation of classes in the 2D embedding space. Visual inspection reveals that FEDNE better maintains the original relationships between data points than the baseline methods.

This figure visualizes the results of dimensionality reduction on scRNA-Seq data using three different methods: a centralized approach (GlobalNE), FEDNE (the proposed method), and FedAvg+NE (a baseline). Four different federated learning settings (20 or 50 clients, and Dirichlet distributions with alpha=0.1 or alpha=0.5) are compared. Each setting’s results are displayed in a separate subplot, showing the 2D embedding of the high-dimensional data. The color-coding indicates different cell types, demonstrating how well each method maintains the separation of cell types in the lower-dimensional representation.

This figure visualizes the 2D embeddings generated by four different federated learning (FL) methods on the Fashion-MNIST dataset. The methods compared are: GlobalNE (a centralized approach using all data), FEDNE (the proposed method), FedAvg+NE (a baseline using FedAvg), and FedProx+NE (another baseline using FedProx). Each method’s embedding is shown for four different non-IID data distributions (Shards(2), Shards(3), Dir(0.1), Dir(0.5)), representing different levels of data heterogeneity across clients. The visualization helps to assess how well each method preserves the original data structure and separates different classes in the 2D embedding space. The differences in cluster separation and overall structure highlight the effectiveness of the proposed FEDNE method in handling non-IID data.

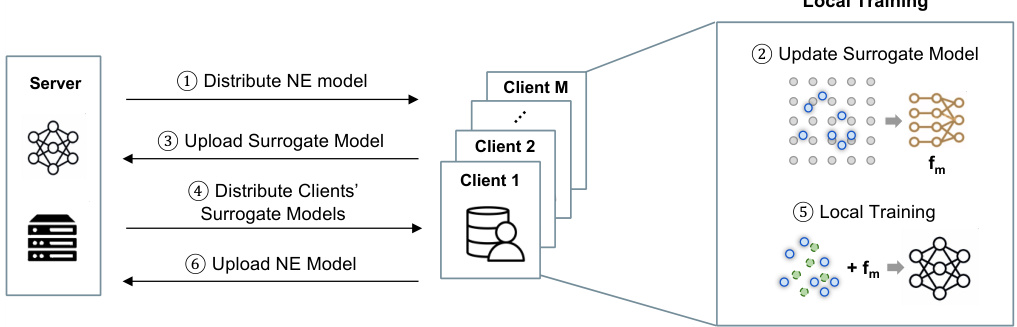

More on tables

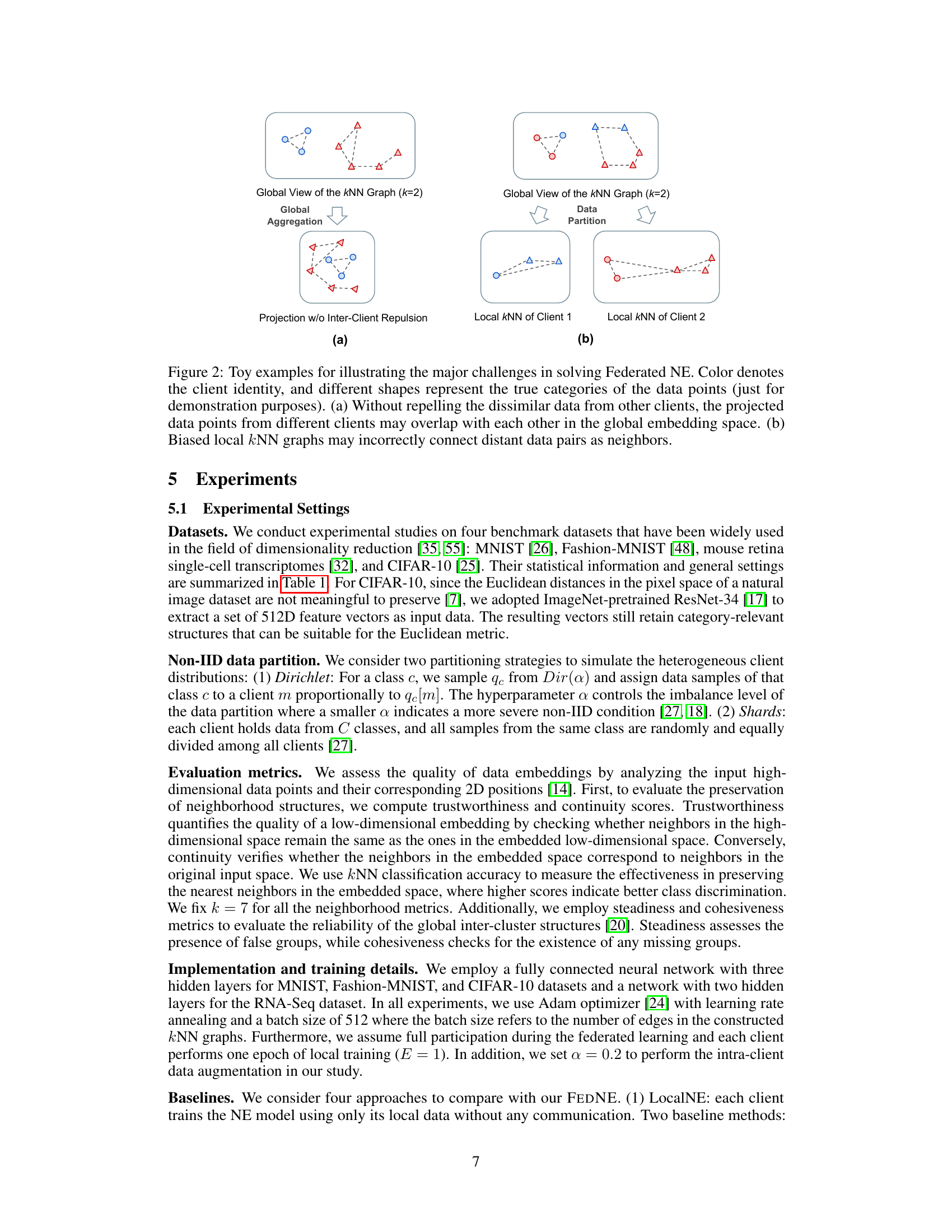

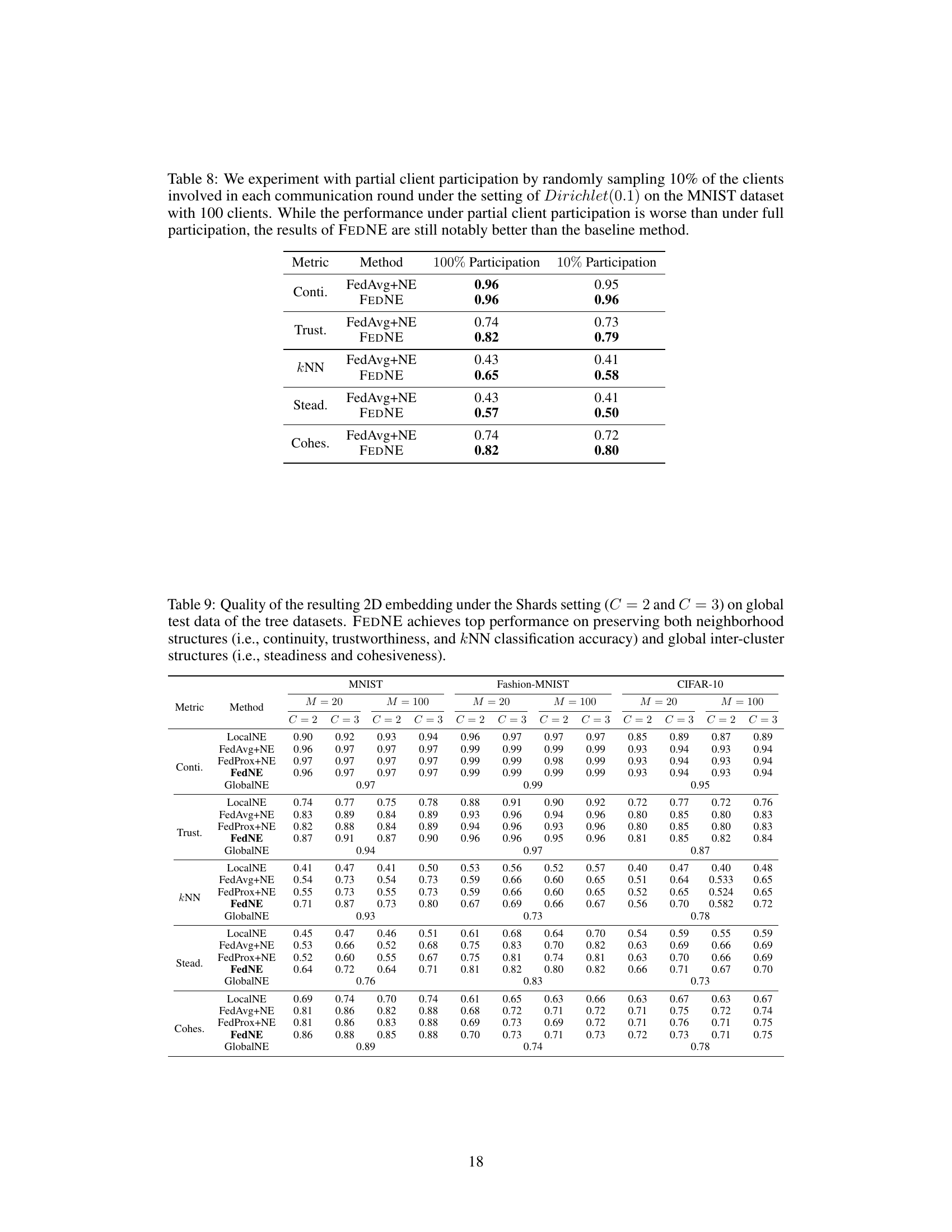

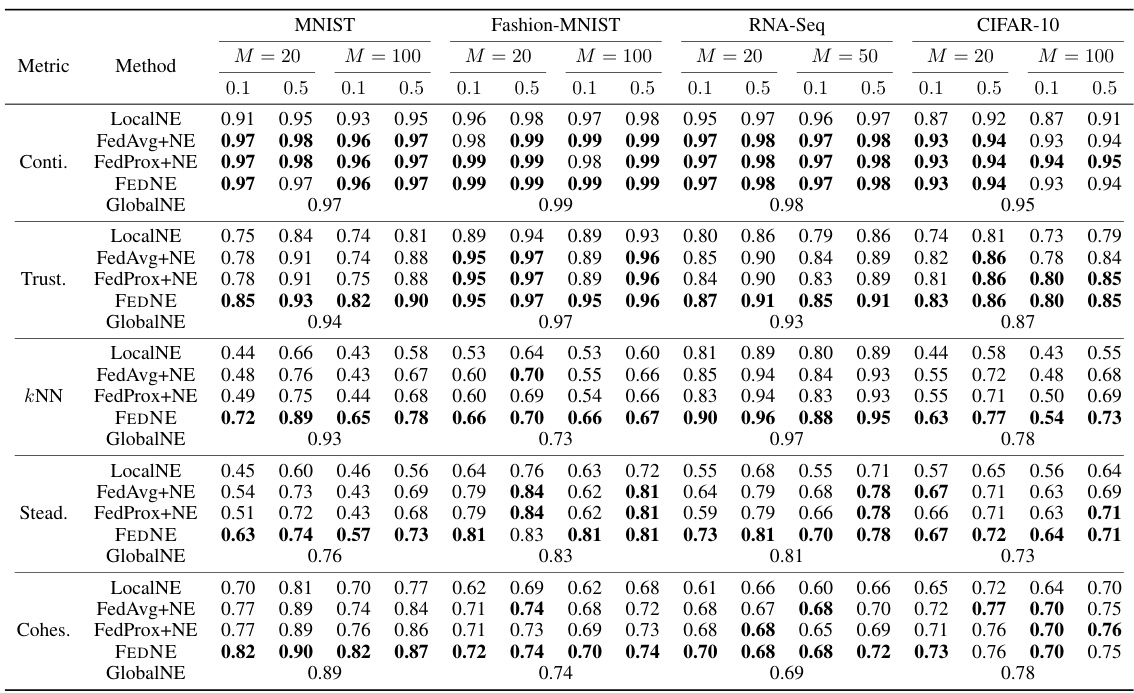

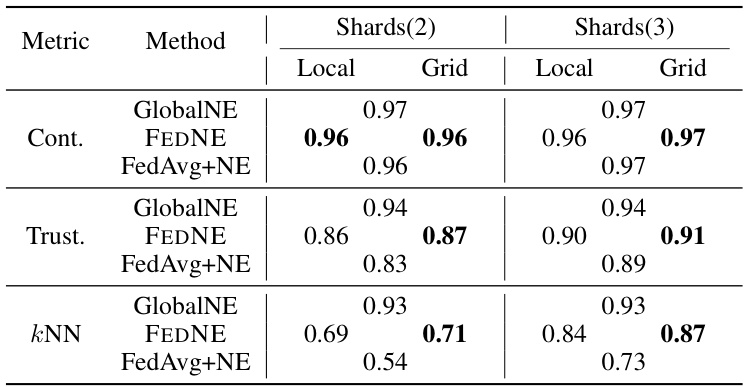

This table presents the performance of FEDNE and baseline methods on four datasets under two different non-IID data distributions (Dir(0.1) and Dir(0.5)). The metrics used to evaluate the quality of the 2D embeddings include continuity, trustworthiness, kNN classification accuracy, steadiness, and cohesiveness. The results show that FEDNE outperforms the baselines in preserving both local neighborhood structures and global clustering structures.

This ablation study analyzes the impact of removing either the data mixing strategy or the surrogate model from the FEDNE pipeline. The table compares the performance of FEDNE with these components removed against the performance of the standard FEDNE and FedAvg+NE baseline methods. The metrics used for comparison include: Continuity (Cont.), Trustworthiness (Trust.), k-Nearest Neighbor classification accuracy (kNN), Steadiness (Stead.), and Cohesiveness (Cohes.). The results are shown separately for MNIST and scRNA-Seq datasets to evaluate the impact of each component across different data characteristics.

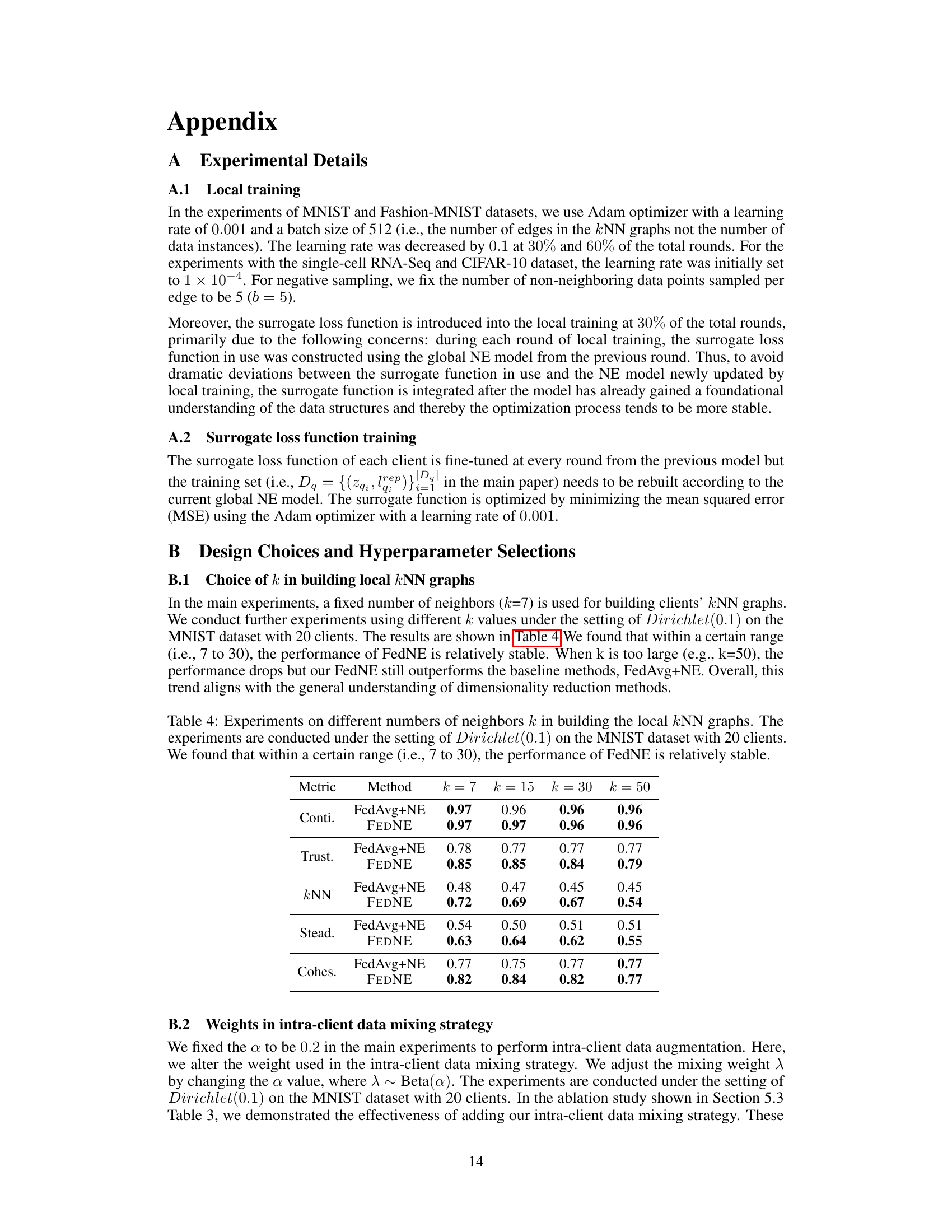

This table presents the results of experiments conducted to determine the optimal number of neighbors (k) to use when constructing local k-nearest neighbor (kNN) graphs for the FEDNE algorithm. The experiments were performed using the MNIST dataset with a non-IID data distribution (Dirichlet(0.1)) and 20 clients. The table shows the performance of both FEDNE and the baseline FedAvg+NE method across five evaluation metrics (Continuity, Trustworthiness, kNN Accuracy, Steadiness, and Cohesiveness) for different values of k (7, 15, 30, and 50). The results indicate that FEDNE’s performance is relatively consistent within the range of k values from 7 to 30, suggesting that this range is suitable for use with the algorithm.

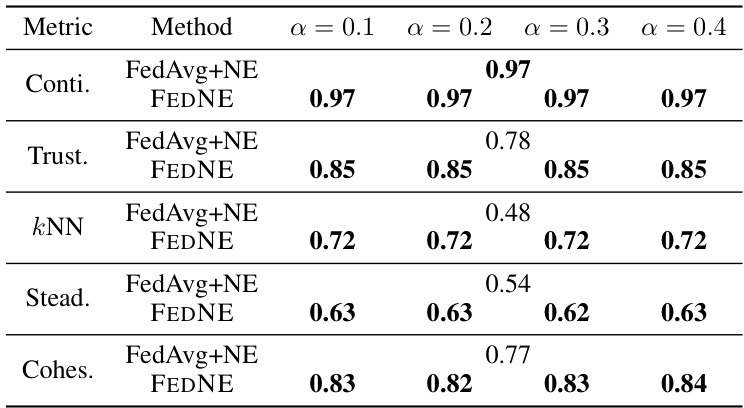

This table presents the quantitative evaluation results of the global test 2D embedding under two different non-IID Dirichlet distributions (Dir(0.1) and Dir(0.5)) on four datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, RNA-Seq, and CIFAR-10). It compares five metrics (Continuity, Trustworthiness, kNN Accuracy, Steadiness, and Cohesiveness) across five methods: LocalNE, FedAvg+NE, FedProx+NE, FEDNE, and GlobalNE. The results show that FEDNE outperforms other methods in preserving both neighborhood and global structures of the data.

This table presents the performance of FEDNE and baseline methods on four datasets under non-IID data distribution using Dirichlet distribution with parameters 0.1 and 0.5. The metrics used to evaluate the performance are continuity, trustworthiness, kNN accuracy, steadiness, and cohesiveness. FEDNE shows superior performance across all metrics and datasets.

This table presents the performance of FEDNE and other methods on four datasets using two different non-IID data distributions (Dir(0.1) and Dir(0.5)). The metrics used to evaluate the performance are continuity, trustworthiness, kNN accuracy, steadiness, and cohesiveness. The results show that FEDNE outperforms the other methods in preserving both neighborhood and global cluster structures.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of FedAvg+NE and FEDNE under two different participation rates: 100% and 10%. The results show the impact of reduced client participation on various metrics like continuity, trustworthiness, kNN accuracy, steadiness, and cohesiveness. FEDNE consistently outperforms FedAvg+NE, even with only 10% client participation.

This table presents the performance of FEDNE and several baseline methods on four datasets under two different non-IID data distributions (Dir(0.1) and Dir(0.5)). The metrics used to evaluate the quality of the 2D embeddings include continuity, trustworthiness, kNN accuracy, steadiness, and cohesiveness, which assess both local neighborhood preservation and global cluster structure preservation. The results show that FEDNE outperforms the baselines across all datasets and metrics, highlighting its effectiveness in preserving both local and global data structures.

Full paper#