↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep reinforcement learning (RL) agents often suffer from issues like goal misalignment, where they optimize unintended side-goals instead of the true objective. This is particularly problematic due to the “black-box” nature of deep neural networks, making it difficult for human experts to understand and correct suboptimal policies. Existing explainable AI (XAI) methods often fail to provide sufficient insight for effective intervention.

This paper introduces Successive Concept Bottleneck Agents (SCoBots), a novel approach to address these issues. SCoBots integrate consecutive concept bottleneck layers that represent concepts not only as properties of individual objects but also as relations between them. This relational understanding is crucial for many RL tasks. By allowing for multi-level inspection of the decision-making process, SCoBots enable human experts to identify and correct suboptimal policies, leading to more human-aligned behavior. The experimental results demonstrate that SCoBots achieve competitive performance, showcasing their potential for building more reliable and safe RL agents.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical issue of goal misalignment in reinforcement learning (RL) by introducing interpretable concept bottlenecks. This allows for easier inspection and correction of suboptimal agent behaviors, leading to more human-aligned RL agents. The approach is particularly relevant given the increasing complexity and opacity of deep RL models, and opens avenues for future work in explainable AI (XAI) and safe RL.

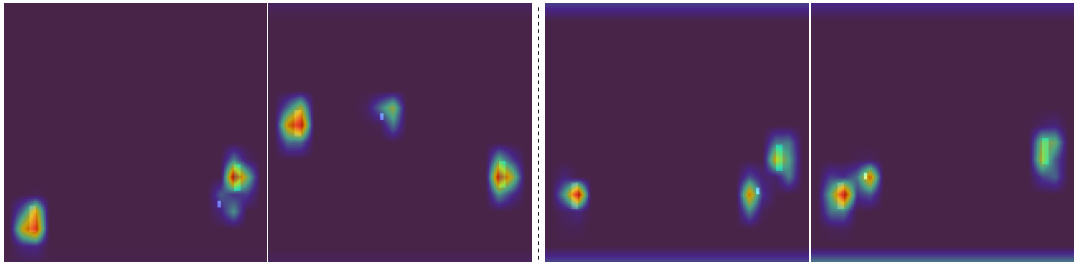

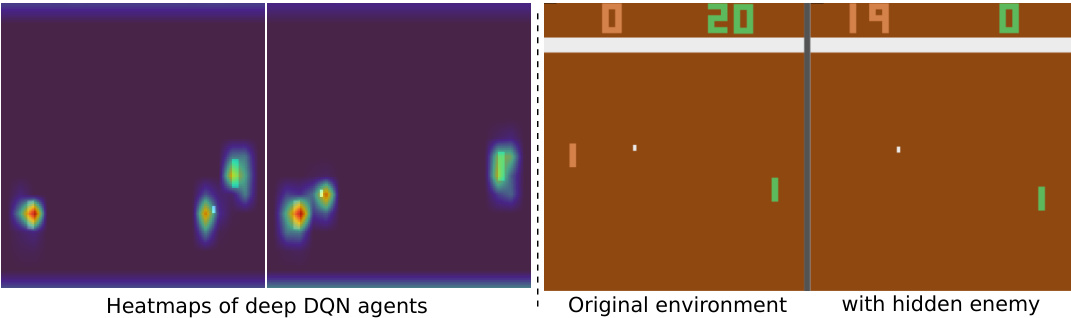

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the core idea of the paper: introducing SCoBots, a new approach to reinforcement learning agents. The top part shows that standard deep RL agents can achieve high scores in the game Pong but fail when the opponent is hidden, highlighting the problem of misalignment. The bottom part showcases SCoBots, which utilize successive concept bottleneck layers allowing for a multi-level inspection and understanding of the agent’s decision-making process, enabling easy intervention and mitigation of misalignment issues.

This table compares the performance of different reinforcement learning agents on various Atari games. It shows human-normalized scores (accounting for human and random baselines), highlighting the competitive performance of SCoBots (Successive Concept Bottleneck Agents) compared to standard deep reinforcement learning agents. It also includes results from variations of SCoBots (with and without guidance) and deep agents from previous work, indicating that object-centric agents can achieve similar or even better scores than purely neural agents. The training of the agents was limited to 20M frames in this study.

In-depth insights#

SCoBots: Intro & Design#

SCoBots, or Successive Concept Bottleneck Agents, are introduced as a novel approach to address the challenges of deep reinforcement learning (RL). The design cleverly integrates consecutive concept bottleneck layers, enabling multi-level inspection of the agent’s reasoning process. Unlike traditional CB models, SCoBots represent concepts not just as properties of individual objects but also as relations between them, which is crucial for numerous RL tasks. This relational understanding enhances the model’s explainability and allows for human intervention to correct misalignments or guide the learning process. The architecture facilitates easy inspection and revision through its human-understandable concept representations at various levels, from object properties to relational concepts to action selection. This unique inspectability addresses the ‘black box’ nature of deep RL, providing crucial transparency for debugging and improving the alignment of agent behavior with desired goals. The modular design of SCoBots allows for independent optimization of the various components, reducing complexity and improving overall performance. This approach is presented as a significant step towards more human-aligned RL agents.

Interpretable RL#

Interpretable Reinforcement Learning (RL) seeks to address the “black box” nature of deep RL agents, which often hinders understanding and debugging. Explainability is crucial for building trust, ensuring safety, and facilitating human-in-the-loop improvements. Current approaches focus on various techniques, including concept bottleneck models, which distill complex agent behavior into understandable concepts. This allows for inspection of decision-making processes at multiple levels of abstraction, offering valuable insight into why an agent takes specific actions. However, challenges remain in balancing interpretability with performance. Furthermore, establishing reliable metrics for evaluating the quality and faithfulness of interpretations is still an ongoing area of research. The field needs to go beyond simple visualization of importance maps towards richer, more nuanced explanations. Ultimately, the goal is to create RL agents that are both high-performing and readily understandable by human experts, fostering more effective collaboration between humans and AI.

Atari Experiments#

The Atari experiments section likely evaluates the proposed Successive Concept Bottleneck Agents (SCoBots) on a set of classic Atari games, a common benchmark in reinforcement learning. The experiments would likely compare SCoBots’ performance against traditional deep reinforcement learning agents, assessing their ability to learn optimal policies and achieve high scores. A key aspect would be analyzing the interpretability of SCoBots, examining whether their internal concepts provide insights into their decision-making process. The experiments may also involve investigating how well SCoBots handle various RL challenges, such as reward sparsity, difficult credit assignment, and goal misalignment, demonstrating the effectiveness of their explainable architecture. Furthermore, the evaluation likely includes ablation studies, removing or altering components of SCoBots (such as relational concepts) to understand their impact on performance and interpretability, and potentially analyzing the effects of human guidance on SCoBots’ behavior. The results would show if SCoBots achieve competitive performance and provide valuable explanations compared to traditional black-box methods.

Concept Bottlenecks#

Concept bottlenecks represent a powerful technique in machine learning, particularly within the context of reinforcement learning (RL), for enhancing model interpretability and aligning agent behavior with human intentions. By introducing intermediate layers that represent high-level concepts extracted from raw data, concept bottlenecks facilitate the understanding of an agent’s decision-making process. This is crucial in RL, where complex policies learned by neural networks can be opaque and difficult to debug. The success of concept bottlenecks hinges on the selection of meaningful and relevant concepts, ideally through collaboration with domain experts. This process can involve careful consideration of the task’s nuances, identification of crucial features, and the design of appropriate functions to abstract those features into interpretable concepts. Careful concept engineering is paramount to avoid the pitfalls of shortcut learning and ensure the agent focuses on the true objectives. Furthermore, the modularity afforded by concept bottlenecks enables iterative refinement and manipulation of the learned concepts, allowing for the mitigation of various RL challenges like reward sparsity or goal misalignment, ultimately fostering a more human-aligned RL approach.

Future of SCoBots#

The future of SCoBots (Successive Concept Bottleneck Agents) looks promising, building on their success in aligning reinforcement learning agents with human intentions. Further research should focus on expanding the types of relational concepts extractable by SCoBots, moving beyond basic properties and spatial relationships to incorporate more complex interactions and temporal dynamics. This could involve integrating advanced symbolic reasoning techniques, perhaps leveraging knowledge graphs or external knowledge bases. Another important area is improving the efficiency and scalability of SCoBots, particularly in more complex environments, possibly through distributed training or optimized data structures. A key challenge is determining effective strategies for human-in-the-loop interaction. Developing intuitive interfaces and streamlined processes for experts to easily inspect, prune, and modify concepts is crucial for wider adoption. Finally, exploration of different applications beyond Atari games will be valuable, particularly in areas where explainability is critical such as robotics, healthcare, and autonomous systems. Combining SCoBots with other XAI techniques, such as counterfactual explanations or causal inference, could enhance their effectiveness and provide even more powerful tools for understanding and aligning AI agents.

More visual insights#

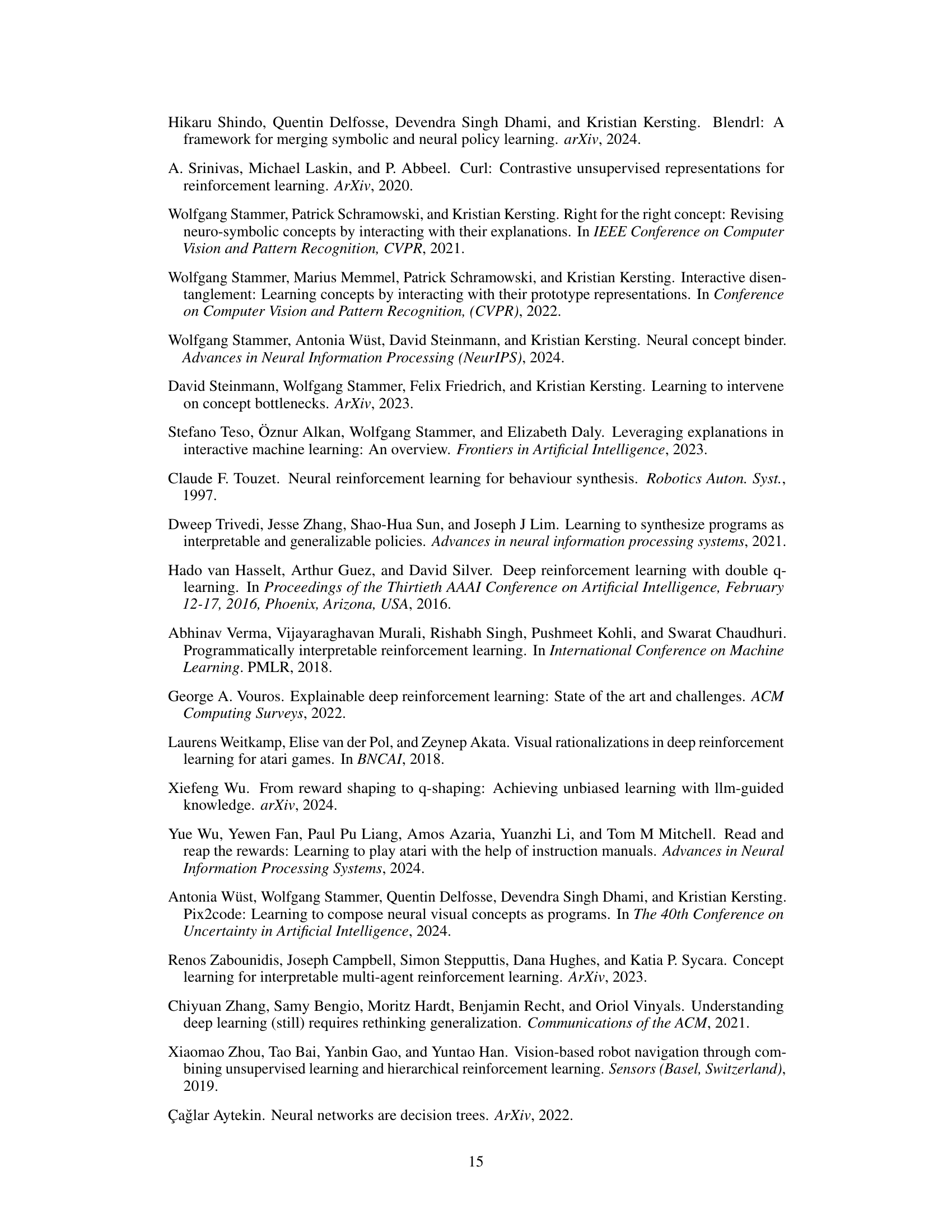

More on figures

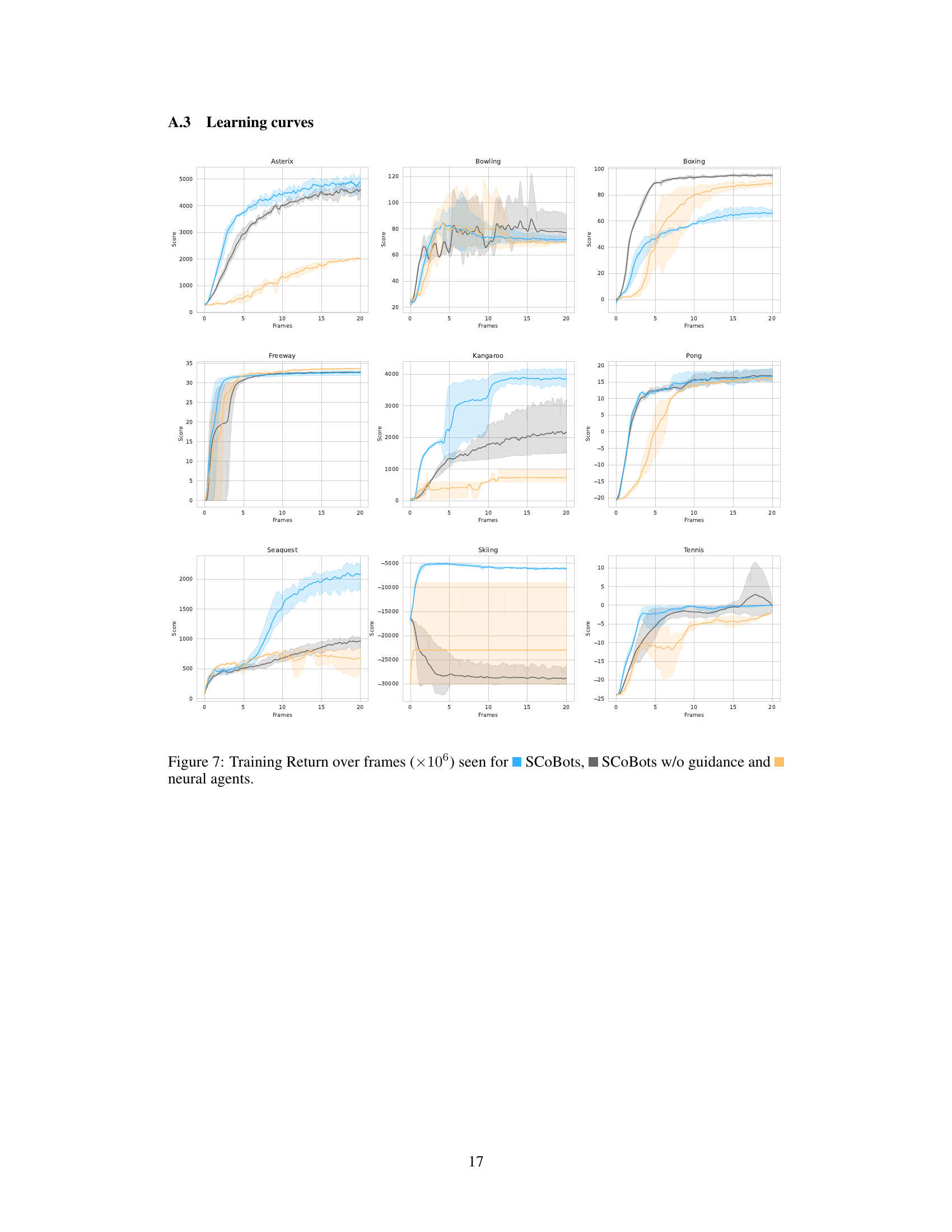

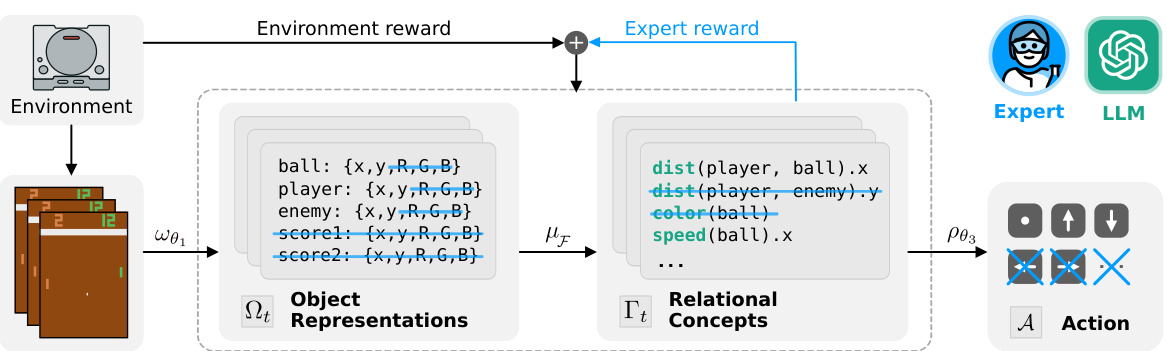

This figure illustrates the architecture of Successive Concept Bottleneck Agents (SCoBots). SCoBots break down the reinforcement learning policy into several interpretable concept bottleneck layers. The process begins with extracting object properties from raw inputs (e.g., images). Then, relational concepts are derived using human-understandable functions applied to these objects (e.g., distance between objects). These relational concepts are used by an action selector to choose the optimal action. The key feature is the interactivity at each layer; experts can modify the concepts or reward signals to align the agent’s behavior with desired goals.

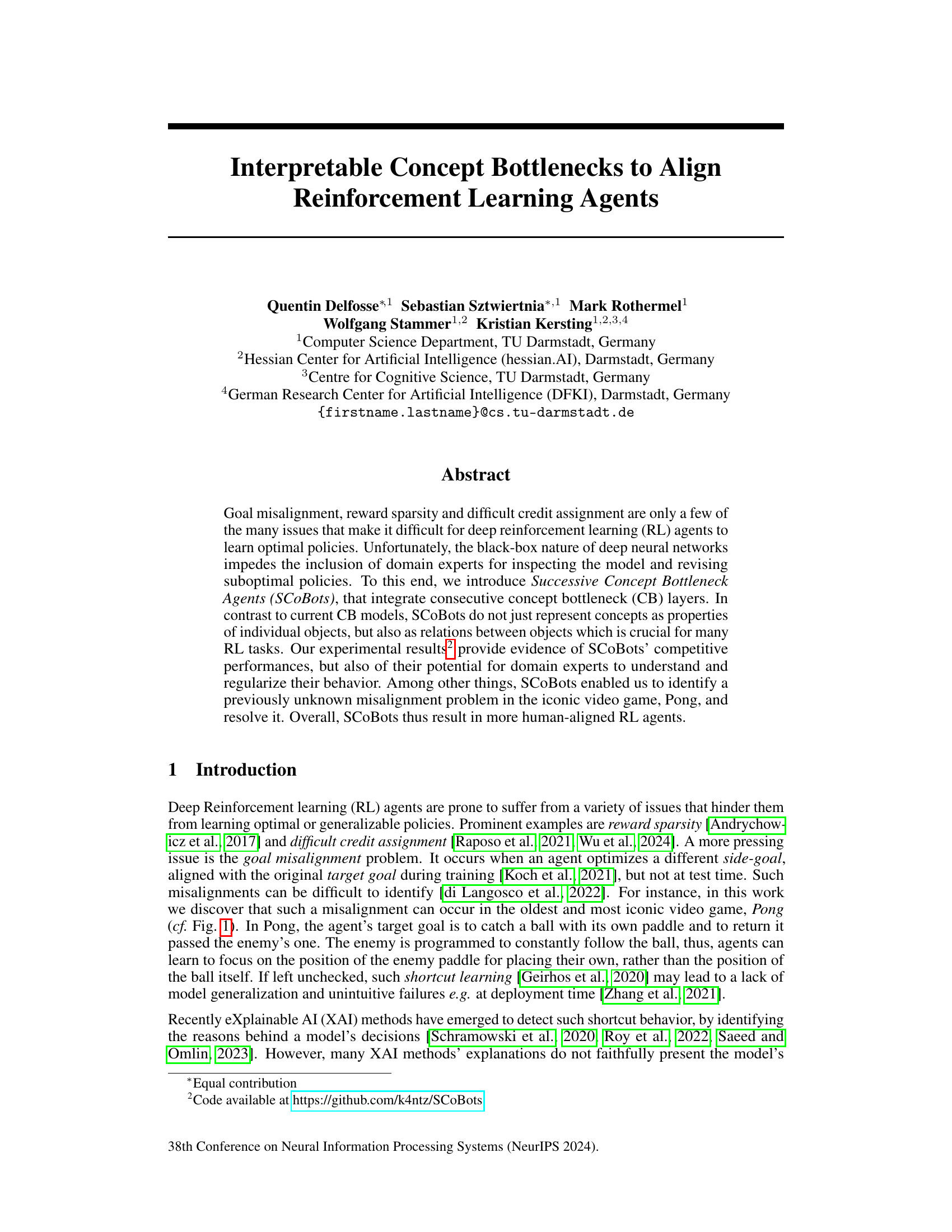

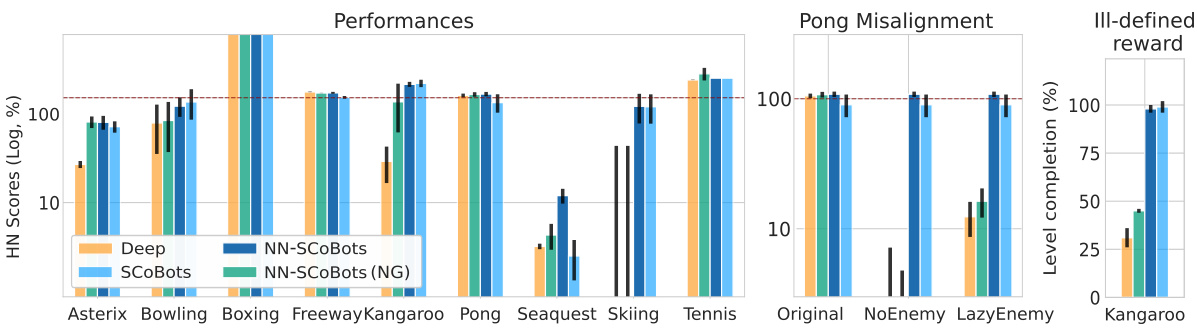

This figure presents a comparison of the performance of different RL agents across various Atari games. The left panel shows that SCoBots achieve comparable or better performance than standard deep RL agents. The middle panel demonstrates SCoBots’ ability to correct for misalignment issues, specifically in the Pong game. The right panel illustrates SCoBots’ capacity for achieving the intended goals in complex scenarios, as seen in the Kangaroo game.

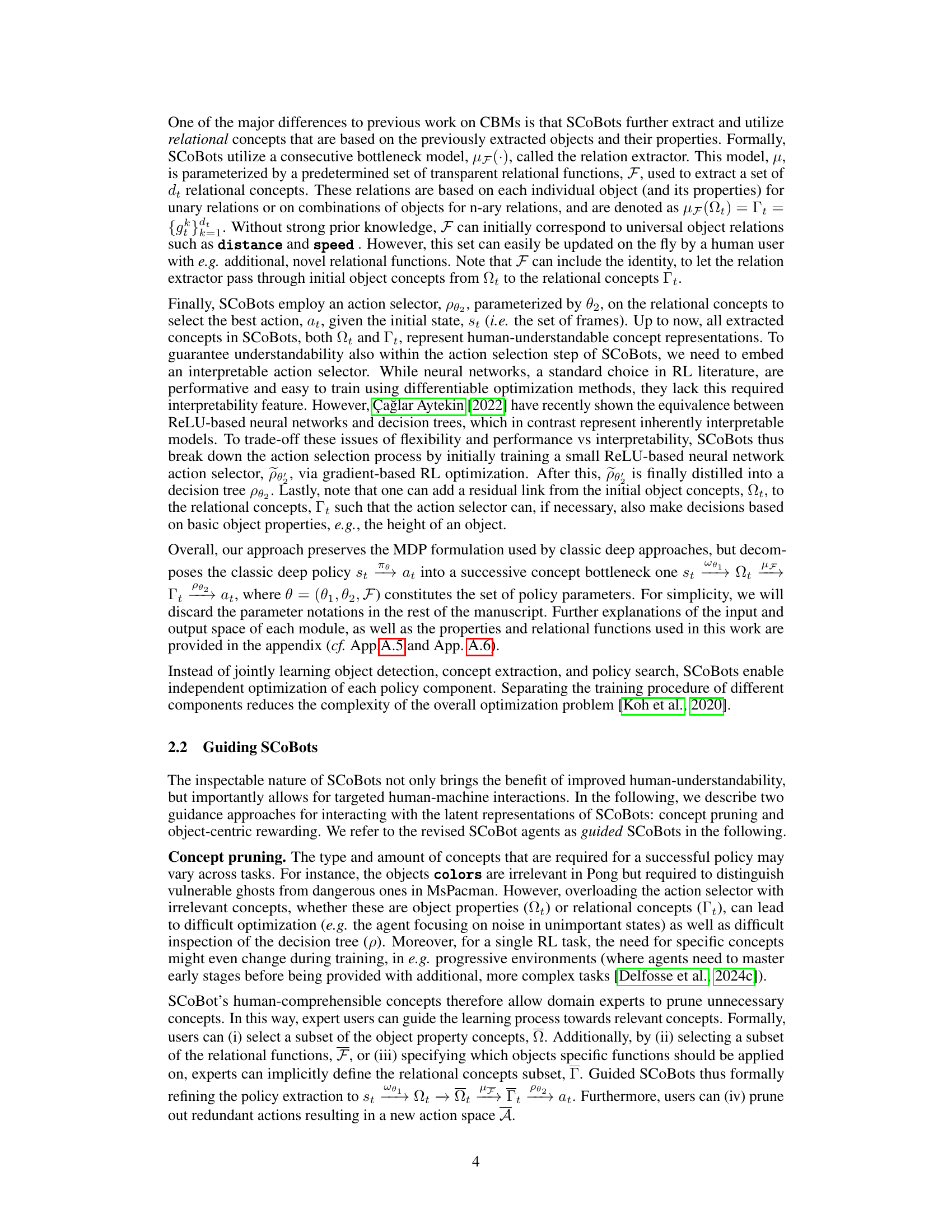

This figure shows three examples of how SCoBots’ interpretable concepts enable tracing the decision-making process. The left panel depicts Skiing, where the agent correctly chooses ‘RIGHT’ because the player’s distance from the left flag exceeds 15 pixels. The center panel illustrates the Pong misalignment; the agent focuses on the enemy’s paddle, not the ball. The right panel showcases Kangaroo, where the agent’s decision to ‘FIRE’ is based on the proximity to a monkey.

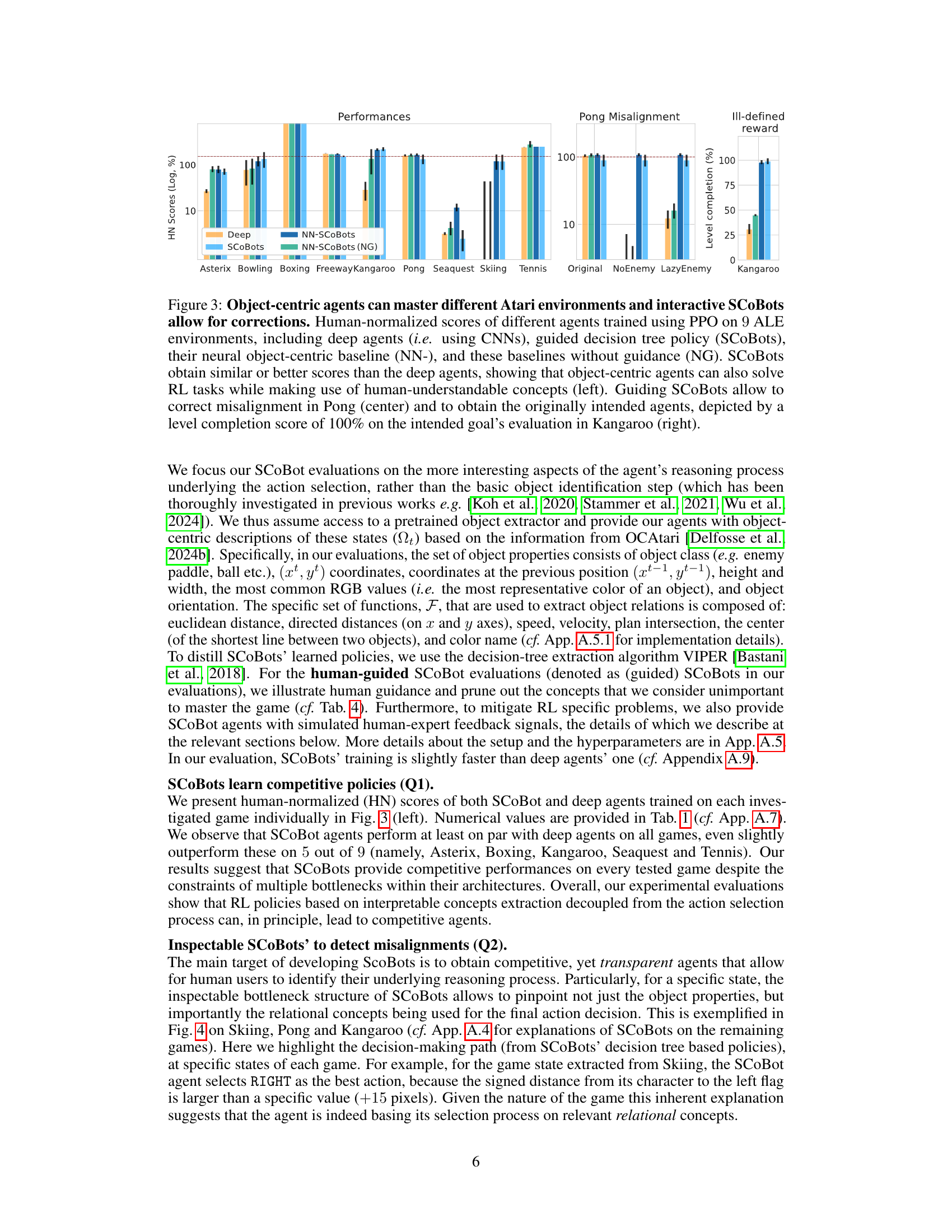

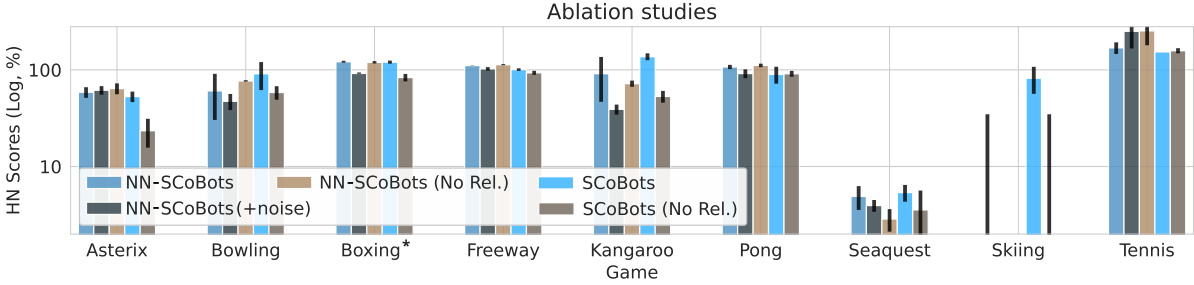

This figure compares the performance of different SCoBots configurations, including those with and without relational concepts and those trained with noisy object detectors. It shows that relational concepts improve performance, except in boxing and that the models are relatively robust to noisy inputs, except on the Kangaroo game.

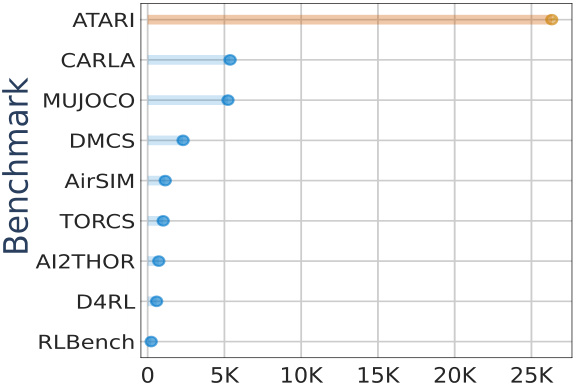

This figure is a bar chart showing the number of publications using different reinforcement learning benchmarks. The Atari benchmark significantly outperforms all other benchmarks in terms of publication count, indicating its widespread use in scientific research.

This figure demonstrates the performance of SCoBots and other RL agents (deep RL agents, NN-SCoBots, and NN-SCoBots(NG)) across 9 Atari games. The left panel compares the performance of SCoBots and deep RL agents, showing similar or better performance with SCoBots. The center panel showcases SCoBots ability to mitigate goal misalignment in Pong. The right panel demonstrates that guiding SCoBots can achieve the intended goal (100% level completion) in the Kangaroo game, suggesting that human-understandable concepts can resolve issues such as goal misalignment.

This figure demonstrates the advantages of SCoBots over traditional deep RL agents in terms of interpretability and goal alignment. The top panel shows that while a deep RL agent performs well in the standard Pong game, it fails when the opponent is hidden, highlighting a hidden misalignment problem. The bottom panel illustrates how SCoBots, through their multi-level concept bottleneck architecture, allow for easy inspection and intervention, enabling better understanding and mitigation of such issues.

This figure shows three examples of how SCoBots make decisions in different Atari games: Skiing, Pong, and Kangaroo. Each example displays a game state and the corresponding decision tree path used by the SCoBot agent to reach its chosen action. The key takeaway is the interpretability of the SCoBots model, allowing for easy inspection and understanding of the reasoning behind the agent’s actions. The Pong example, in particular, highlights a case of goal misalignment where the agent focuses on a spurious correlation between the positions of paddles instead of directly using the ball’s position, showcasing a previously unknown issue with the game.

This figure illustrates the core idea of the paper. The top part shows that standard deep RL agents, when trained on the Pong game, may develop strategies that rely on the enemy’s paddle position, even though the ball’s position is more relevant. When the enemy is hidden, the agent fails. The bottom part illustrates how SCoBots, by introducing intermediate concept layers, allow for better interpretability and mitigation of such issues. The figure depicts how SCoBots allow inspecting and revising the reasoning process at multiple levels. This enables users to identify and address misleading concepts. It highlights that SCoBots allow for human intervention in model learning to prevent the agent from relying on shortcuts.

This figure shows examples of the decision-making process used by SCoBots agents on three different Atari games: Skiing, Pong, and Kangaroo. The decision trees, extracted from the trained models, show how the agent selects an action based on a series of interpretable concepts. Each game example highlights how different relational concepts, such as distances between objects, are used by the agent in their reasoning process. This is particularly important for highlighting the interpretability advantage of SCoBots over traditional deep RL agents, which often provide opaque and inscrutable explanations.

The figure shows the number of steps needed for a random agent and a guided agent to receive a reward in the Pong game. The original Pong environment has a sparse reward, meaning that the agent only gets a reward when it scores a point. The assisted agent has an additional reward signal that is inversely proportional to the distance between its paddle and the ball, which incentivizes the agent to keep a vertical position close to the ball. As a result, the assisted agent receives rewards more frequently than the original agent.

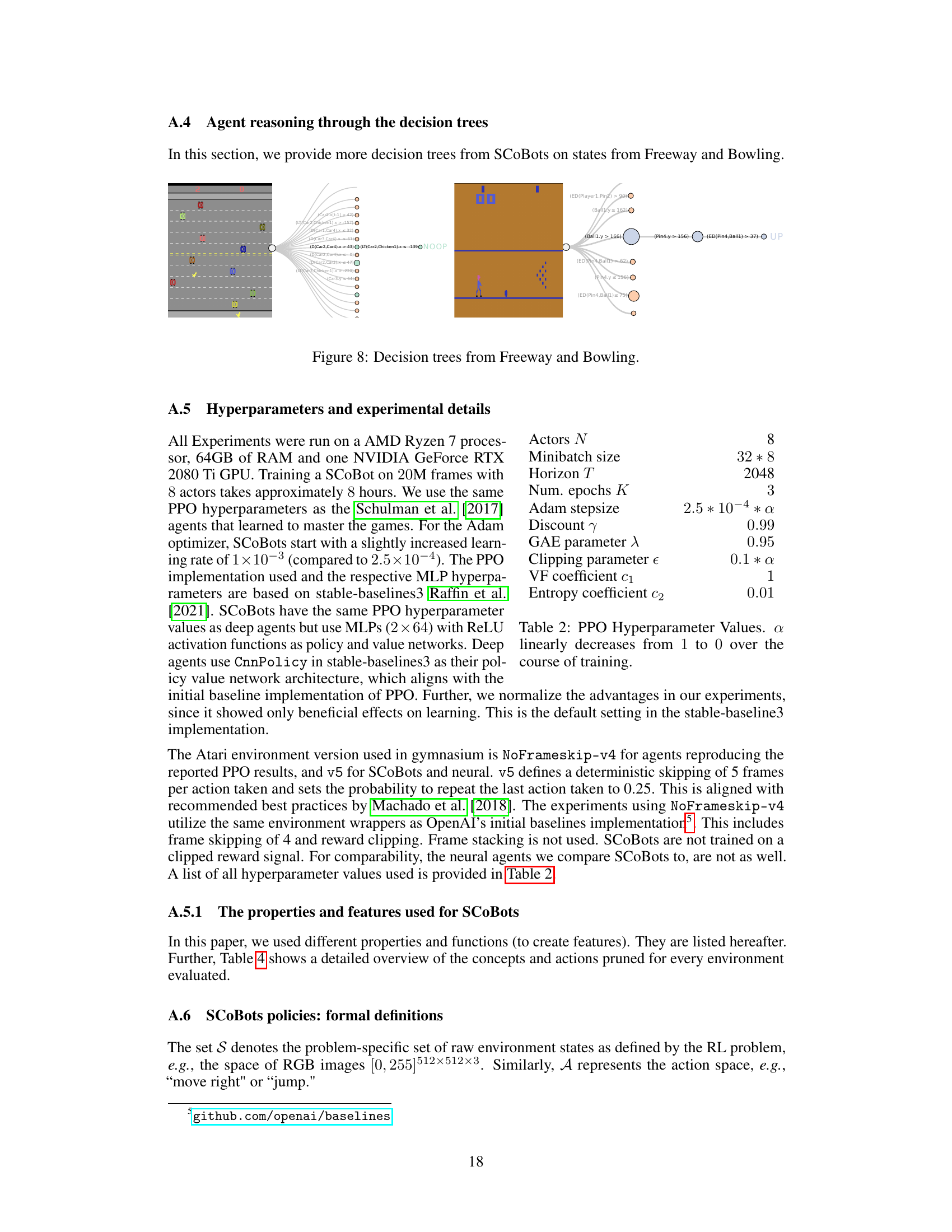

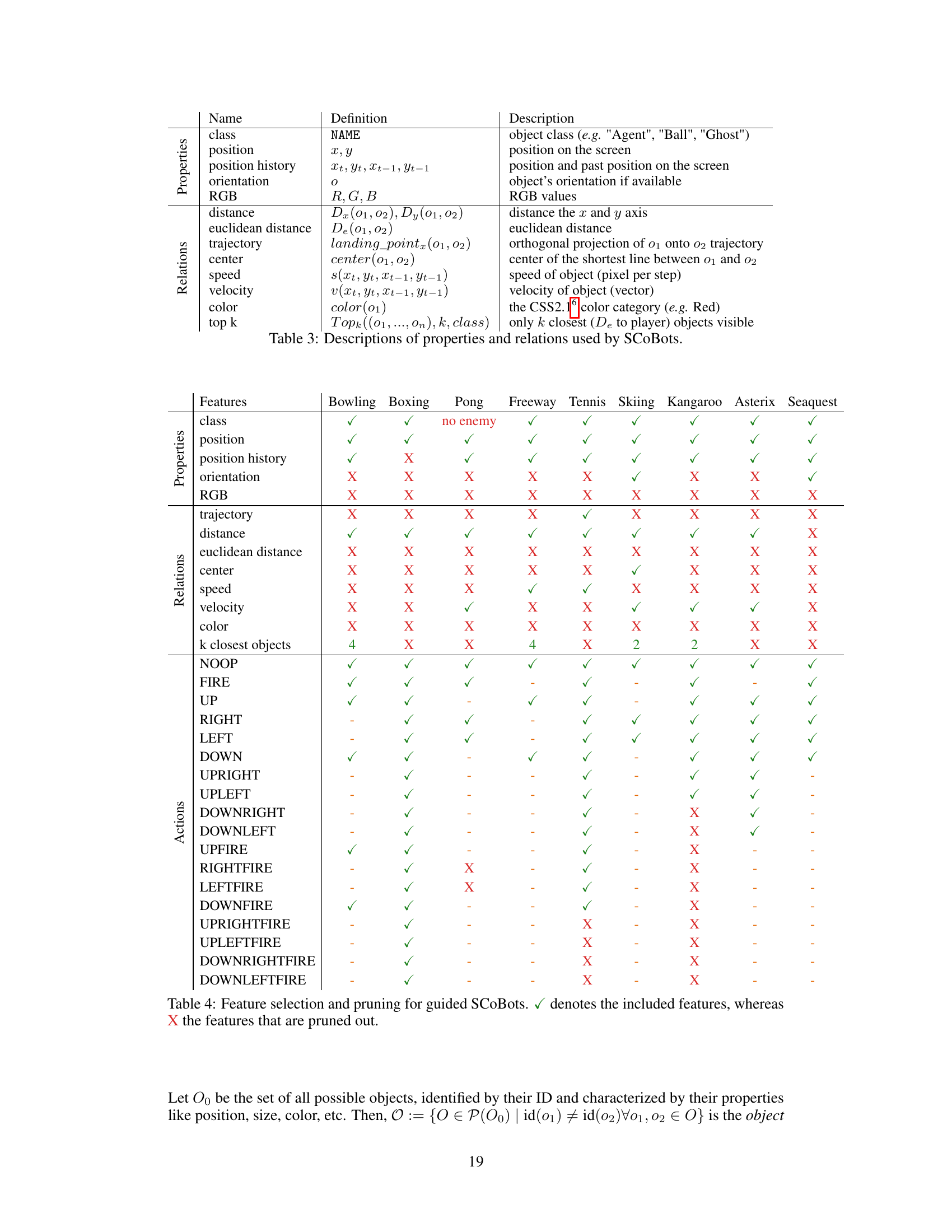

More on tables

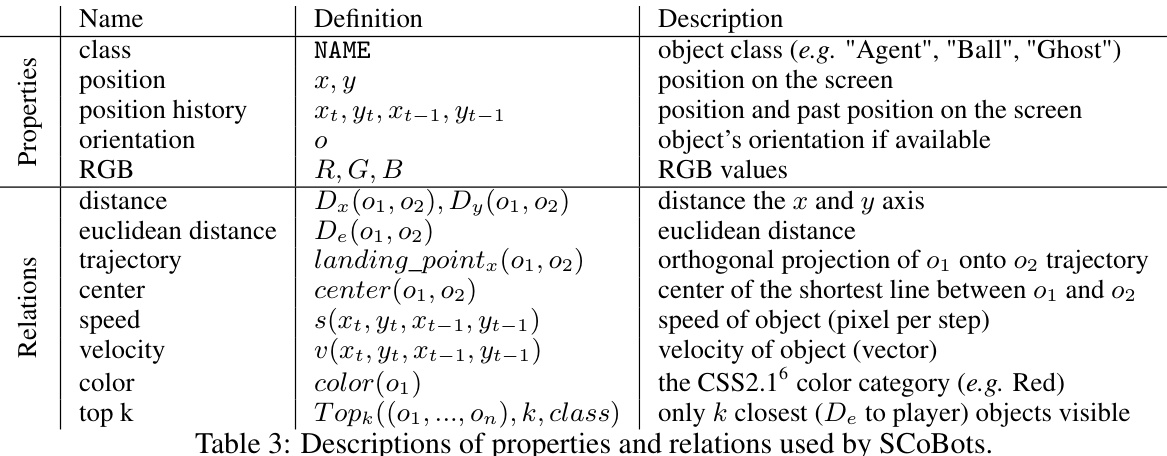

This table lists the properties and relations used by the Successive Concept Bottleneck Agents (SCoBots) in the paper. The properties describe individual features of objects in the environment (e.g., position, color), while relations capture the relationships between these objects (e.g., distance, speed). The table provides a detailed definition and description for each property and relation, including its mathematical notation or calculation method. This information is crucial for understanding how SCoBots process information from the environment to make decisions.

This table shows which features (properties and relations) are used by the SCoBots agents for each of the nine Atari games. It also indicates whether certain features were removed (pruned) during the guided SCoBots experiments. The pruning was done to reduce the complexity of the decision-making process and to test whether the removal of less-relevant features impacts the model’s ability to learn effective policies. The table is organized by game and feature category. For each feature, a checkmark indicates inclusion, while an ‘X’ indicates removal or pruning in the respective game.

This table presents a comparison of the training time for SCoBots (with OCAtari), deep agents, and SCoBots without guidance (NG) across nine different Atari games. The training times are given in hours and minutes (HH:MM). The results show that SCoBots generally require less training time compared to deep agents, especially in games with a smaller number of objects.

Full paper#