↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Clinical data often exists in various forms (e.g., clinical notes and structured clinical concepts), but privacy restrictions limit access. Existing large language models (LLMs) can improve clinical NLP tasks, but training them on detailed clinical data is time-consuming and resource-intensive. This necessitates methods for learning from limited data while respecting privacy constraints.

This paper proposes a novel teacher-teacher framework that uses two pre-trained LLMs, each processing a different data form, which are then harmonized using a lightweight alignment module (LINE). The LINE module excels at capturing key information from clinical notes using de-identified data. This framework showcases effective knowledge exchange between LLMs and improved performance on various downstream tasks, providing a practical and privacy-preserving approach to clinical language representation learning. This novel approach allows researchers to leverage the power of pretrained LLMs without requiring retraining on sensitive patient data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel and efficient teacher-teacher framework for clinical language representation learning, addressing the challenges of data scarcity and privacy in clinical settings. It offers a practical solution for leveraging existing large language models (LLMs) to improve clinical NLP tasks and opens new avenues for cross-form representation learning and knowledge transfer in other domains.

Visual Insights#

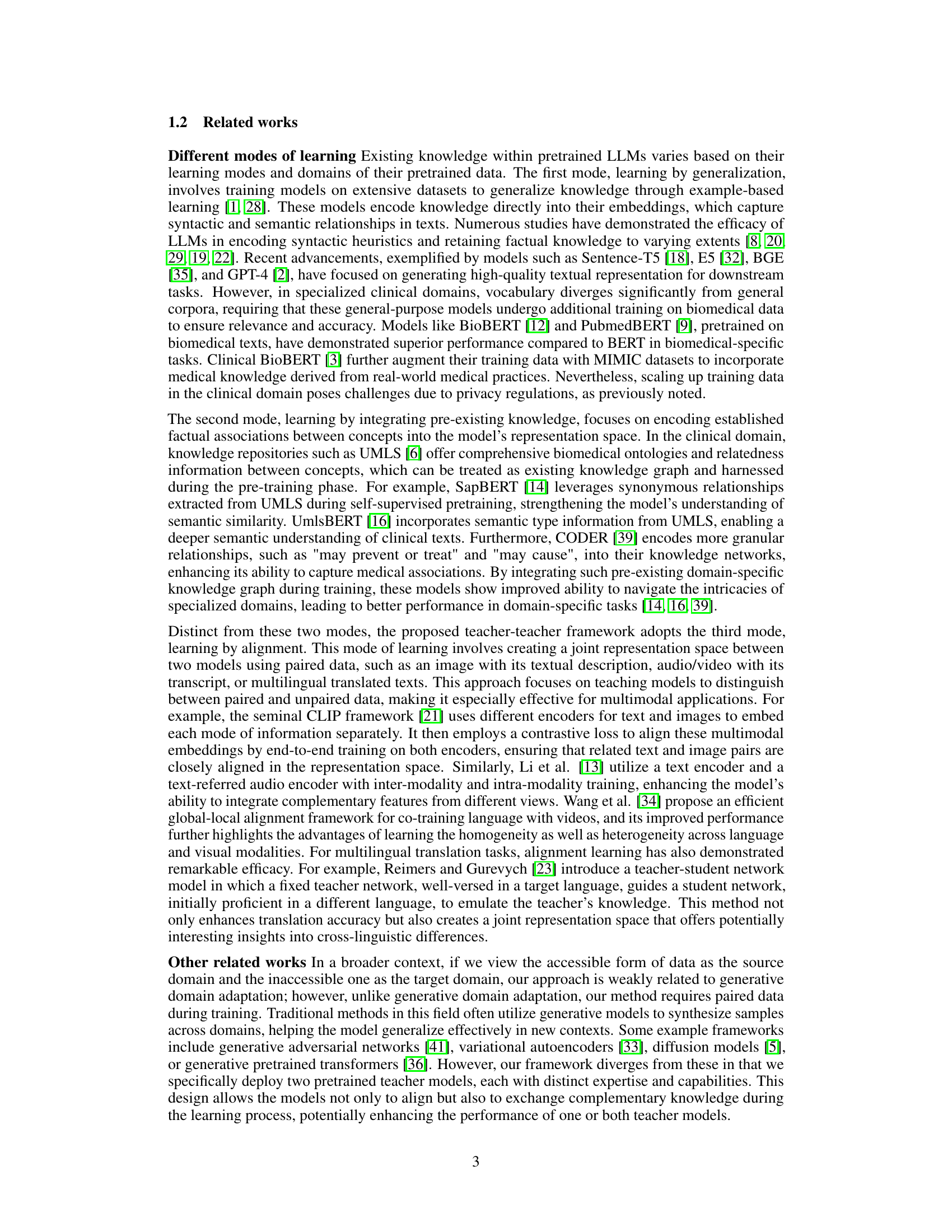

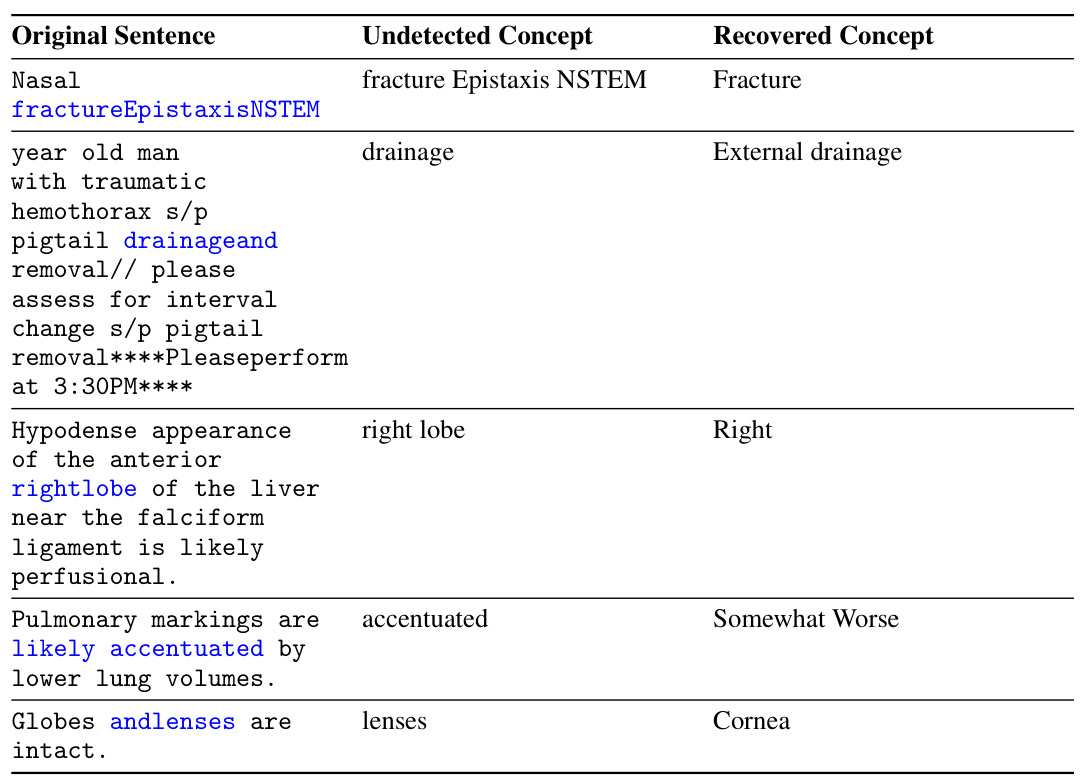

This figure illustrates the teacher-teacher framework for clinical representation learning. Two different types of clinical data (unstructured clinical notes and structured clinical concepts in a relational graph) are fed into two pretrained LLMs (Teacher 1: general purpose LLM and Teacher 2: LLM with domain knowledge). The LINE module then aligns the resulting representations from both models into a unified representation space. This alignment facilitates mutual learning and allows the model to capture critical information from both data sources, improving downstream tasks and allowing for cross-form representation.

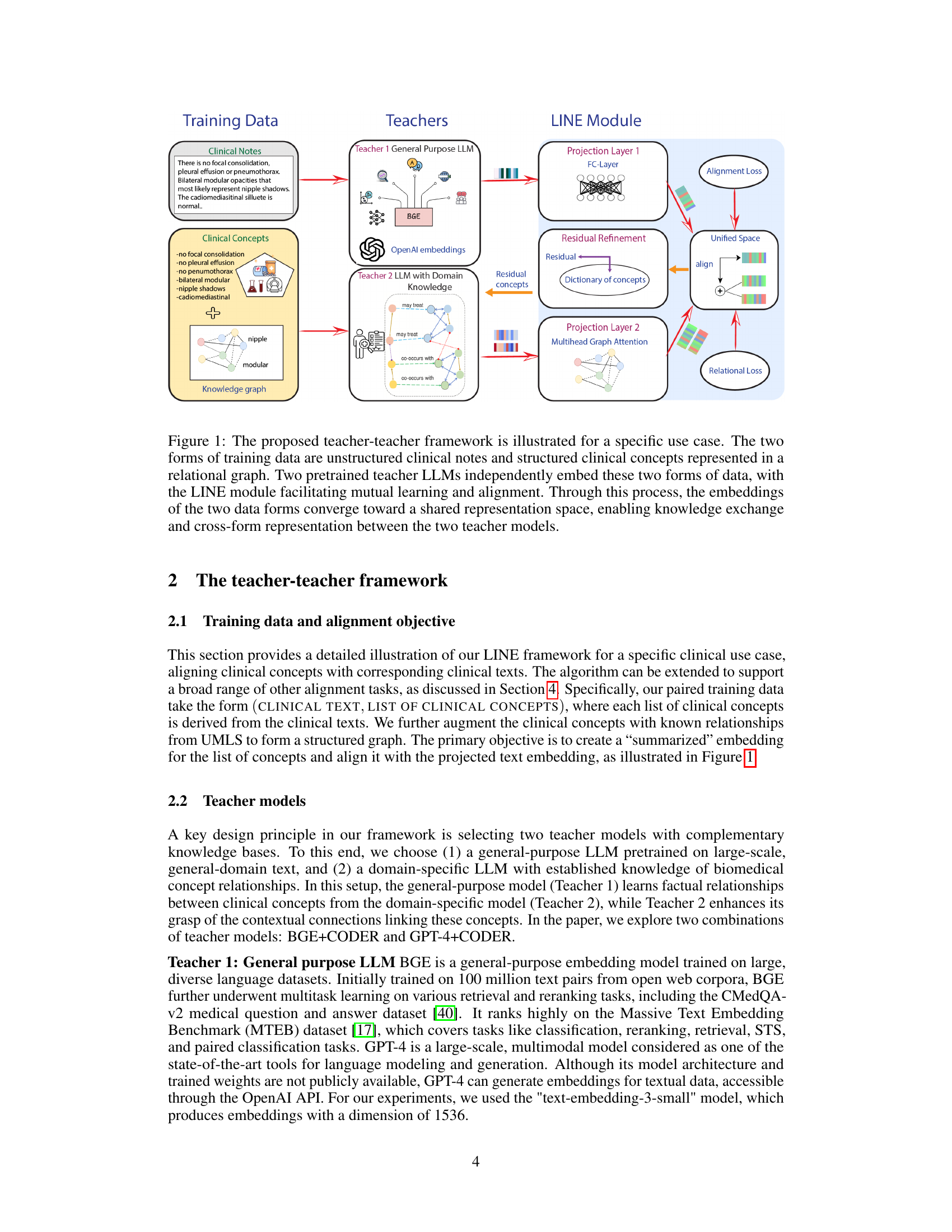

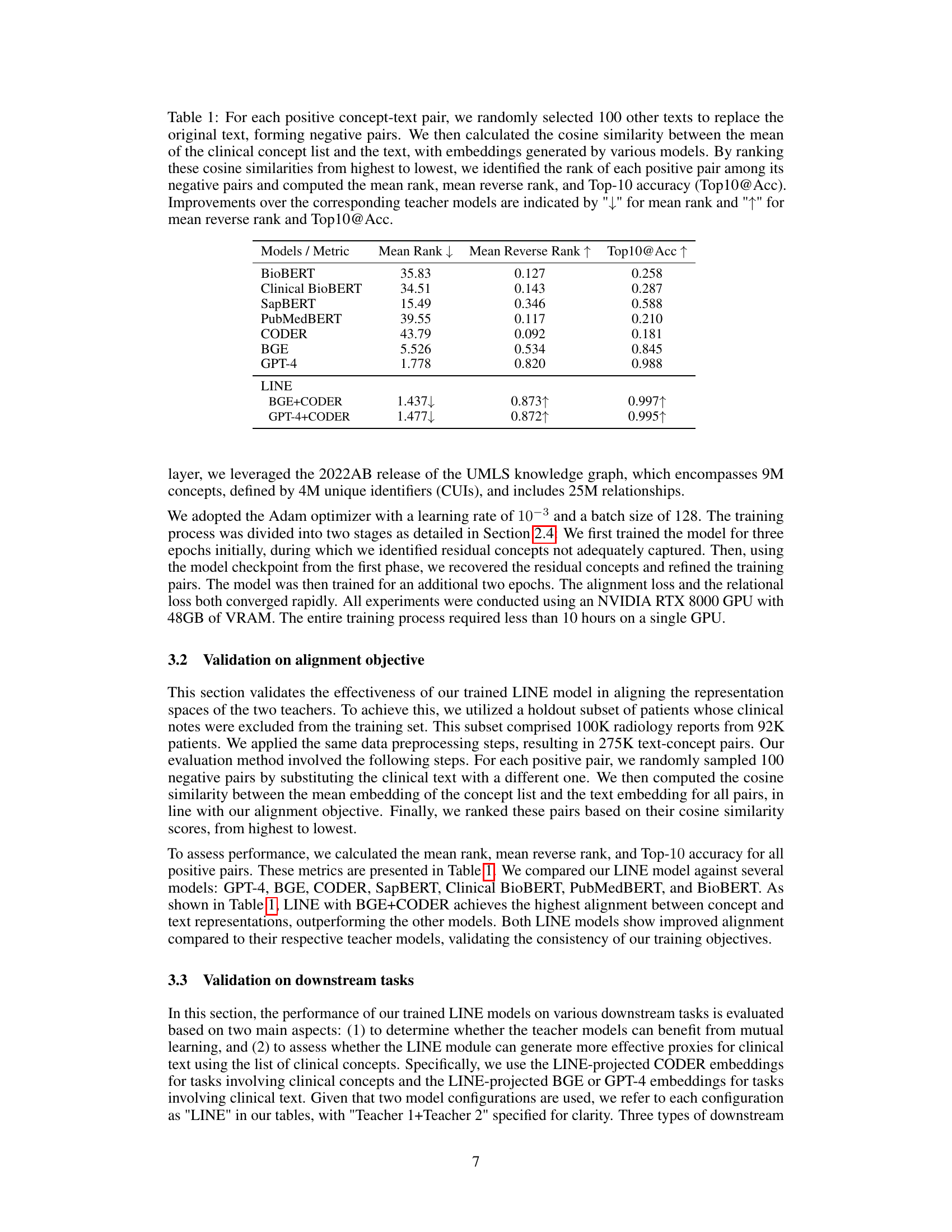

This table presents the results of a cosine similarity experiment designed to evaluate the alignment of clinical text embeddings with their corresponding clinical concept embeddings. It compares various models (including BioBERT, Clinical BioBERT, SapBERT, PubMedBERT, CODER, BGE, GPT-4, and two versions of the LINE model) by calculating their mean rank, mean reverse rank, and Top-10 accuracy in correctly aligning positive text-concept pairs against randomly selected negative pairs. Lower mean rank and higher mean reverse rank and Top10@Acc indicate better alignment.

In-depth insights#

Teacher-Teacher LLM#

The concept of a ‘Teacher-Teacher LLM’ presents a novel approach to leveraging pre-trained large language models (LLMs). Instead of training a single model from scratch or continuously fine-tuning an existing one, this framework proposes a mutual learning process between two pre-trained LLMs. Each LLM acts as a ’teacher,’ specializing in processing different data modalities or possessing complementary knowledge. A lightweight alignment module harmonizes their knowledge representations, resulting in a unified and improved representation space. This is particularly valuable for domains like clinical language processing, where data privacy and regulatory constraints limit access to large, comprehensive datasets. The benefits include faster training times, reduced resource requirements, and the ability to generate proxies for missing data, thus enhancing model effectiveness and expanding potential applications for LLMs.

LINE Module#

The LINE (LIghtweight kNowledge alignmEnt) module is a central component of the proposed teacher-teacher framework, acting as a bridge between two pre-trained LLMs. Its primary function is to align the knowledge representations from these two models, which may possess complementary knowledge due to differences in training data or model architectures, into a unified representation space. This alignment is achieved through a two-stage training process. The first stage focuses on initial alignment and capturing residual information (complementary knowledge), while the second stage refines this alignment using the captured residuals to further improve the unified representation. Efficiency is a key design principle, with the LINE module’s training being focused solely on aligning the two LLMs’ representations without retraining the base models. The framework’s use of LINE enables cross-form representation, meaning the ability to generate a representation of one data form based solely on the other, opening possibilities for applications where only one form of data is available.

Clinical Use Case#

The paper highlights a crucial clinical application focusing on patient data privacy. It leverages two forms of clinical data: unstructured clinical notes and structured lists of clinical concepts. The core challenge is that using raw clinical notes is hindered by strict regulations, while concept lists, though easier to share, lack the rich contextual information found in the notes. The framework aims to generate proxies for clinical notes using concept lists, enabling research and analysis while adhering to privacy standards. This approach cleverly addresses the trade-off between data accessibility and privacy concerns, demonstrating the framework’s practical value in real-world clinical settings. The use case strongly suggests that the method is relevant to other scenarios where access to one data type is readily available, but the other is restricted, making it a broadly applicable technique beyond its initial clinical focus.

Downstream Tasks#

The evaluation of a clinical language representation learning framework often involves assessing its performance on downstream tasks. These tasks, which utilize the learned representations, are crucial for demonstrating the framework’s practical utility and generalizability. Effective downstream tasks should reflect real-world clinical applications, such as clinical concept similarity assessment, named entity recognition in clinical texts, or disease prediction. A strong framework should exhibit improved performance on these tasks compared to existing methods. A key consideration is the selection of diverse downstream tasks, covering a range of complexities and data types, to provide a comprehensive evaluation. Careful analysis of results across multiple tasks, including error metrics and statistical significance, is essential to establish the framework’s reliability and robustness. The inclusion of baseline models allows a direct comparison, showcasing the advantages of the proposed approach. Ultimately, strong performance on relevant downstream tasks reinforces the practical value and potential impact of the proposed framework in clinical settings.

Future Work#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending LINE to handle diverse data modalities beyond text and structured concepts, such as images or signals, would broaden its applicability. Investigating more sophisticated alignment techniques than cosine similarity could improve the accuracy and robustness of knowledge transfer. The impact of different pretrained models on LINE’s performance warrants further investigation. Analyzing the effects of variations in training data size and composition on model effectiveness would refine practical guidelines for implementation. Finally, rigorous evaluation across a wider array of clinical tasks is crucial to establish LINE’s generalizability and clinical utility.

More visual insights#

More on tables

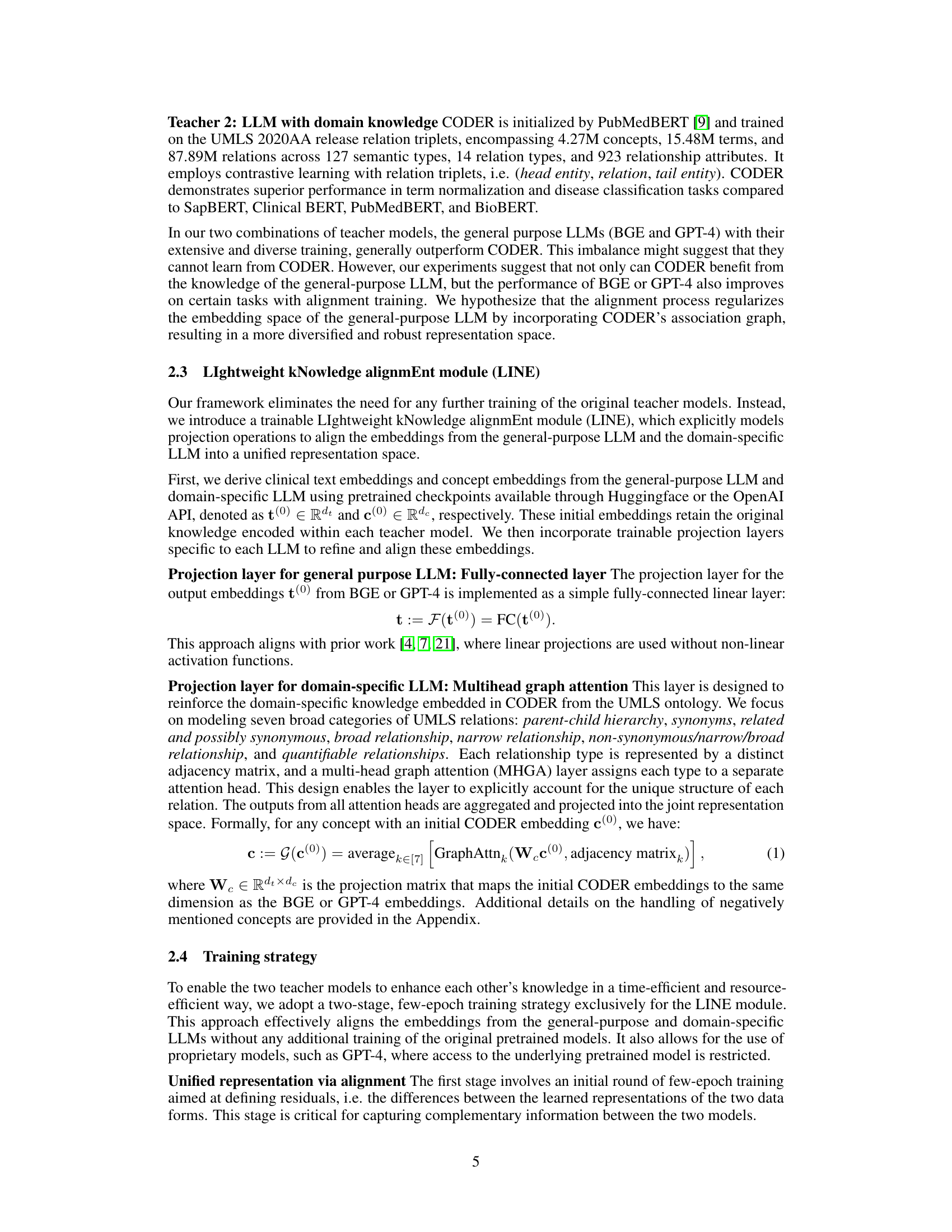

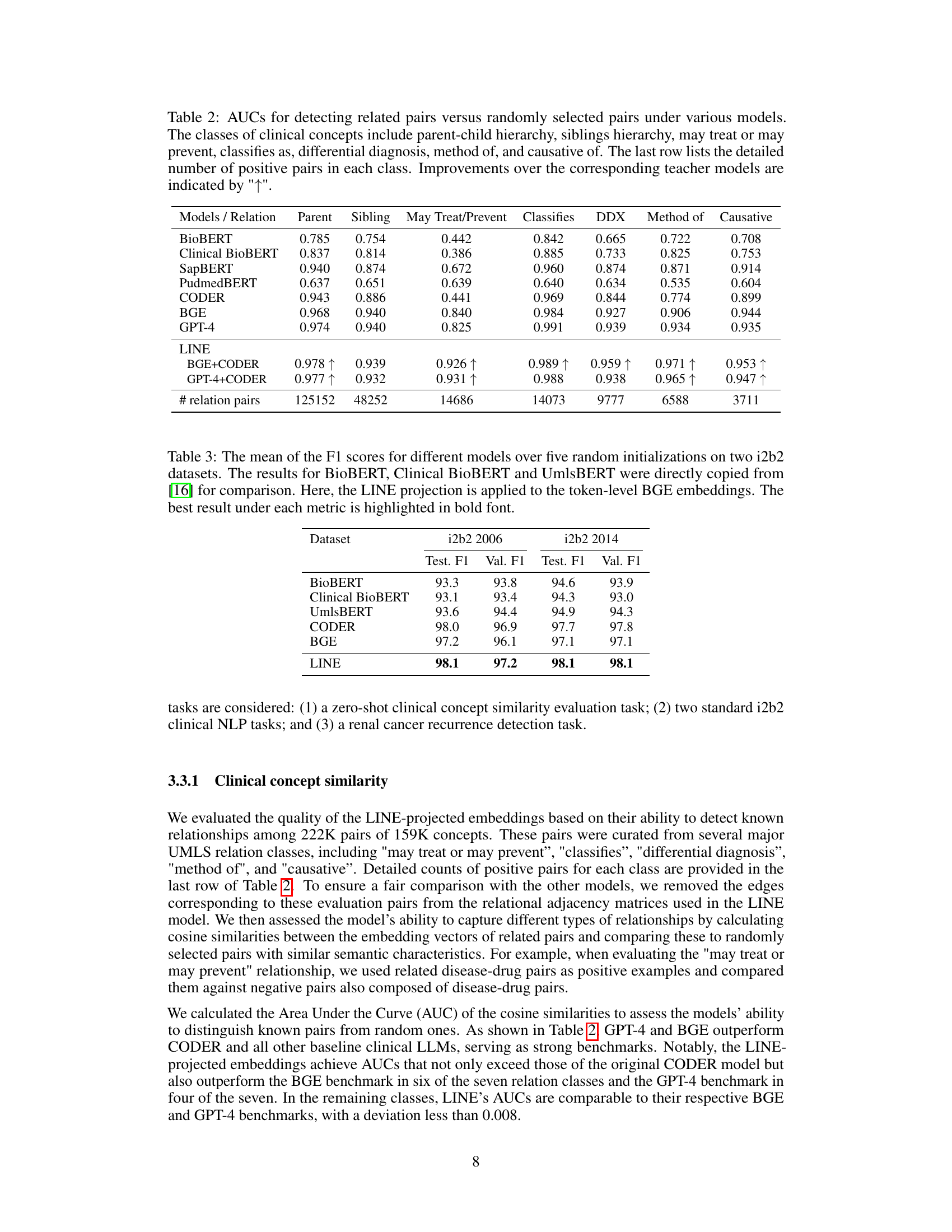

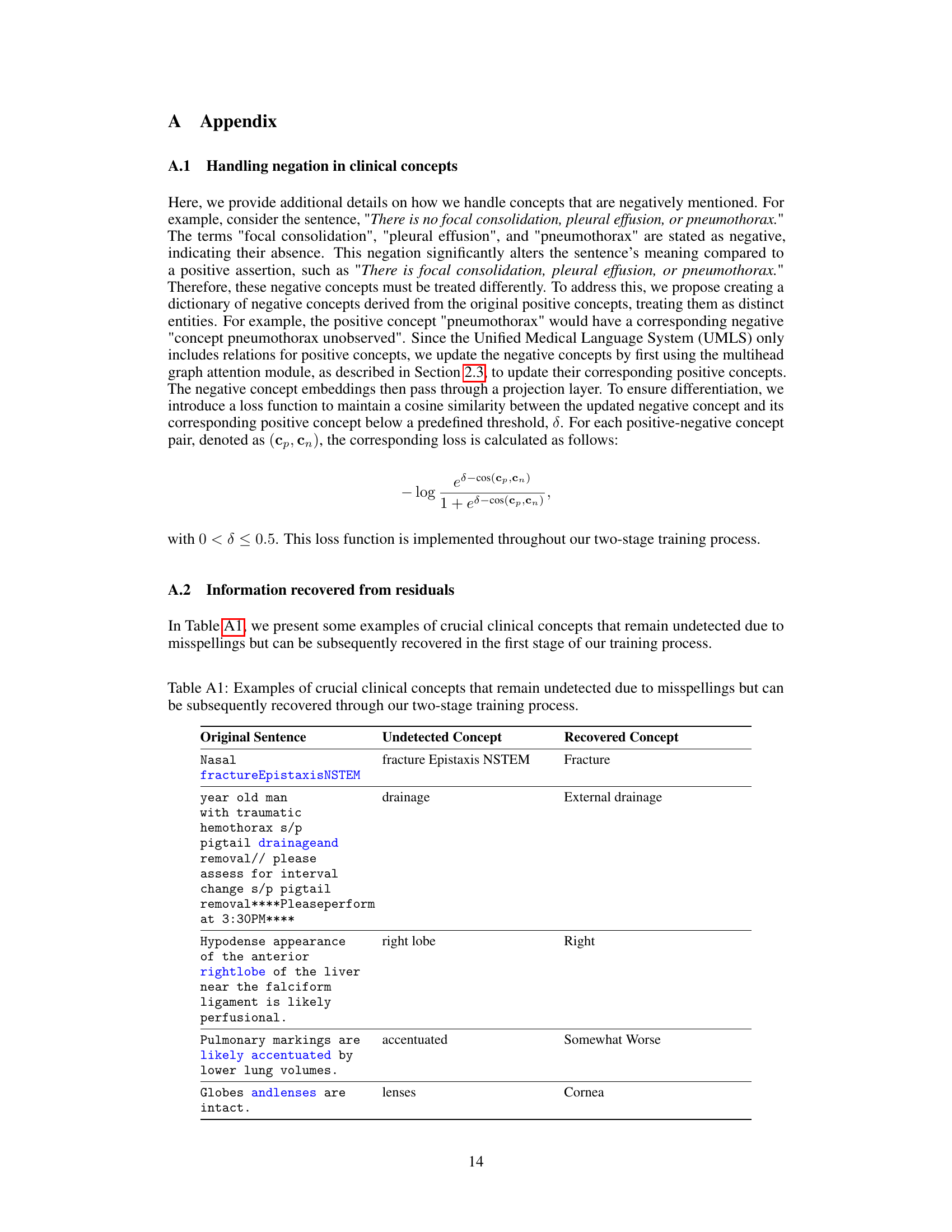

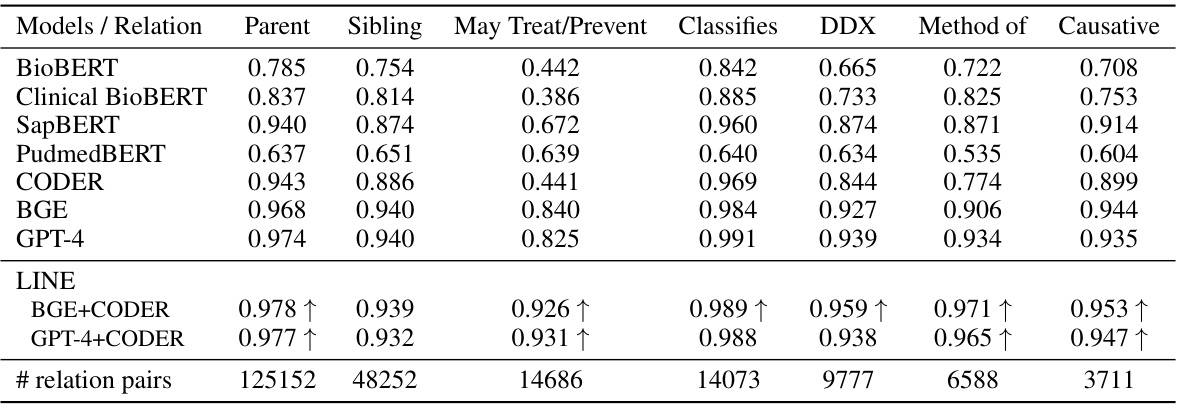

This table presents the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for various models in detecting related pairs of clinical concepts compared to randomly selected pairs. The clinical concepts are categorized into seven relationship types (parent-child, sibling, may treat/prevent, classifies as, differential diagnosis, method of, causative of). The AUC is calculated for each relationship type and model, showing the model’s ability to distinguish true relationships from random associations. Improvements achieved by the LINE model over its constituent teacher models (BGE and CODER or GPT-4 and CODER) are highlighted.

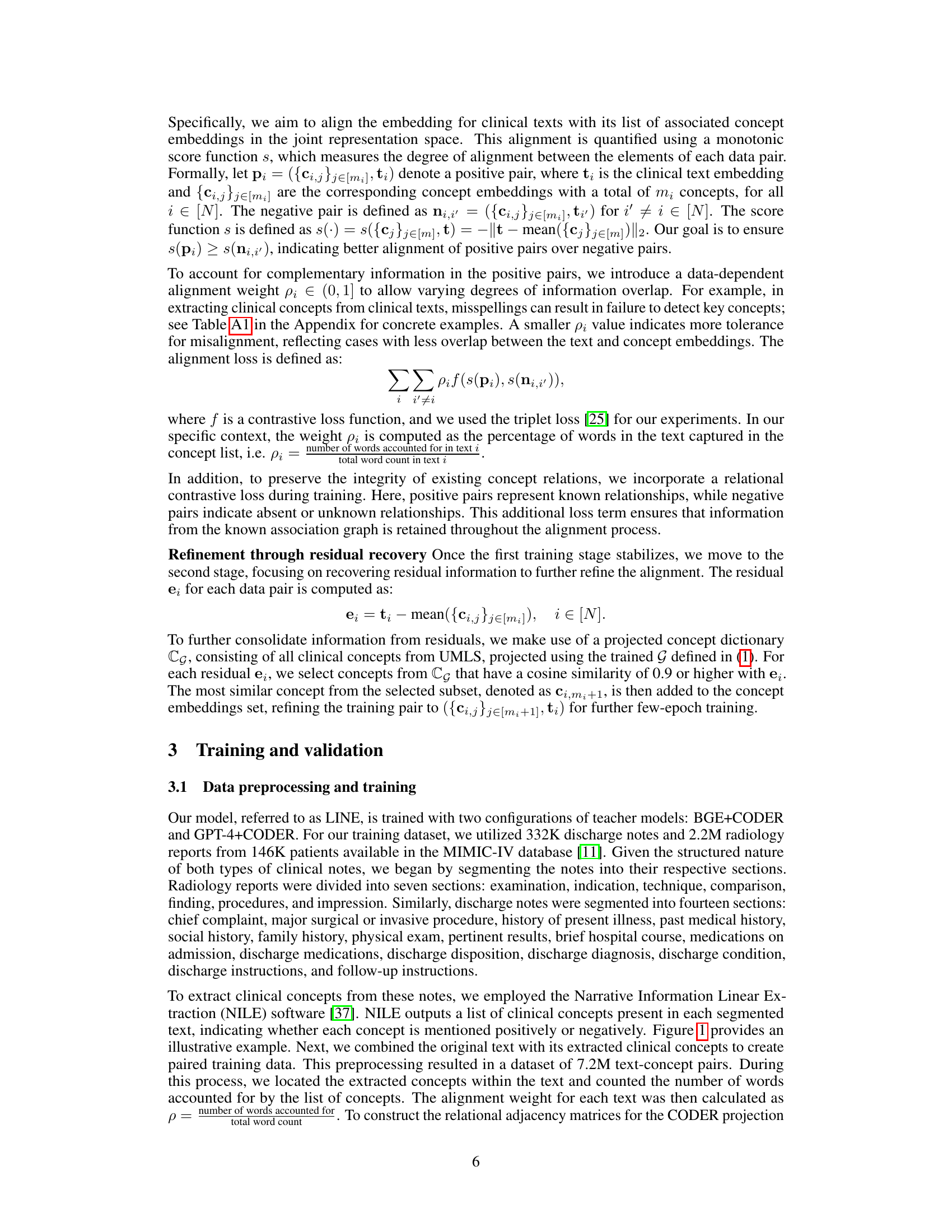

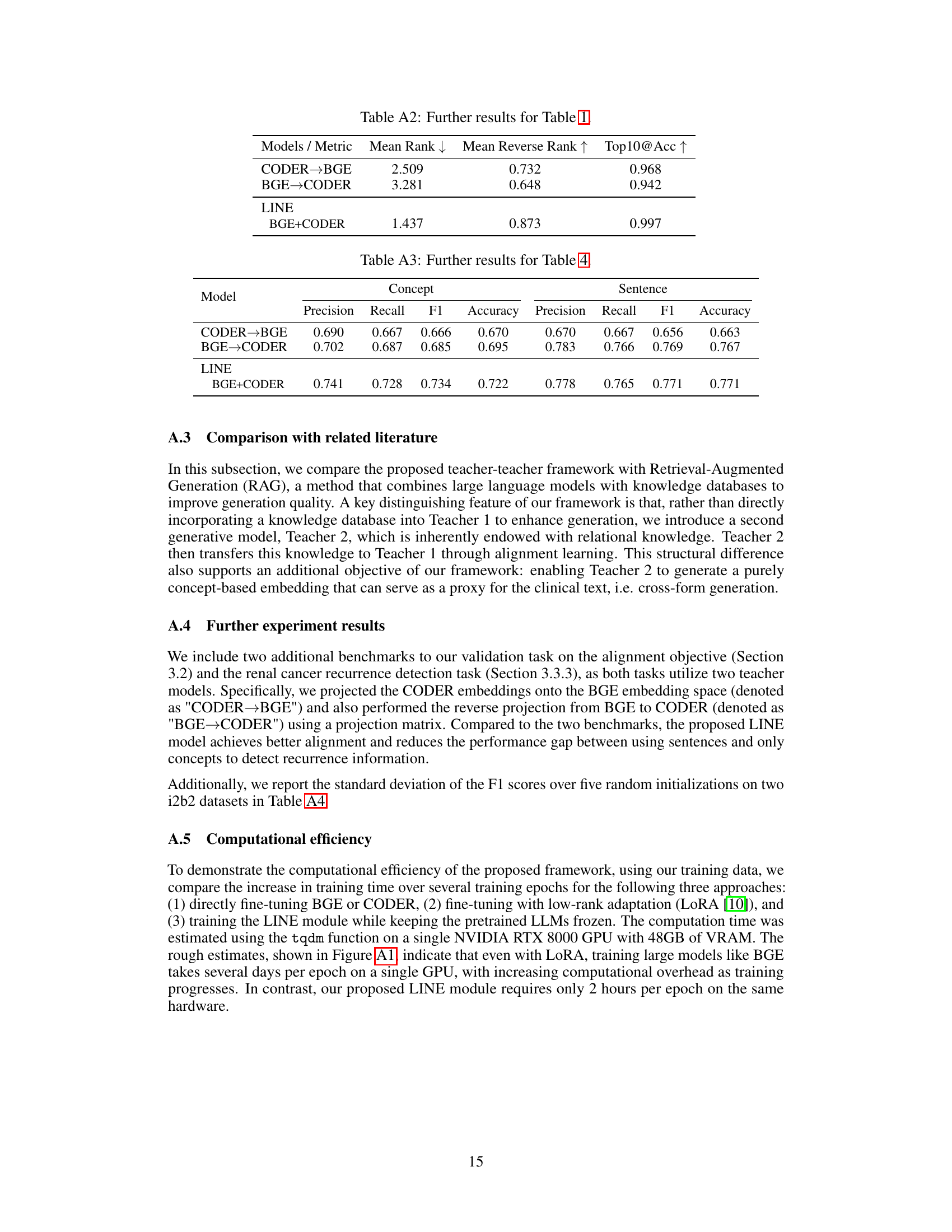

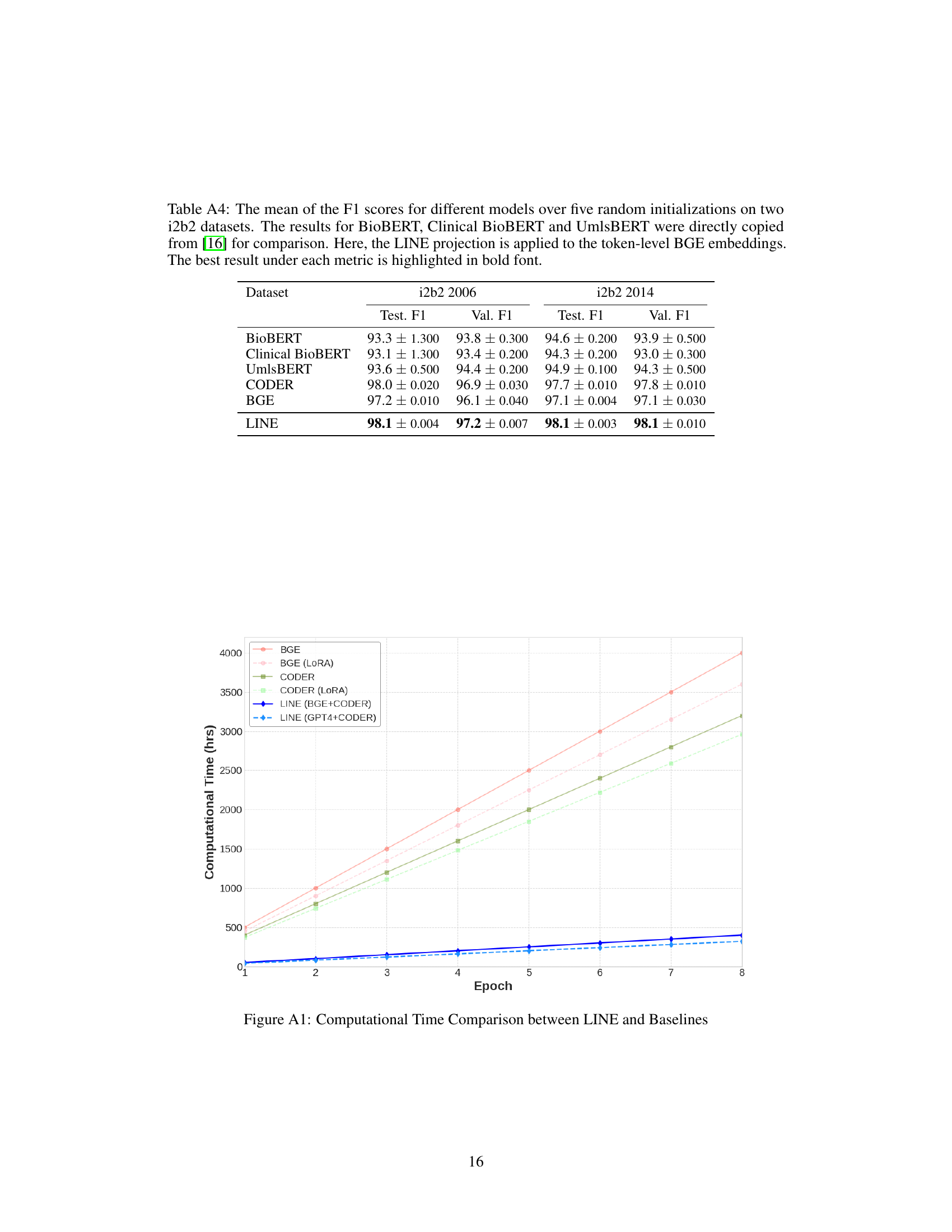

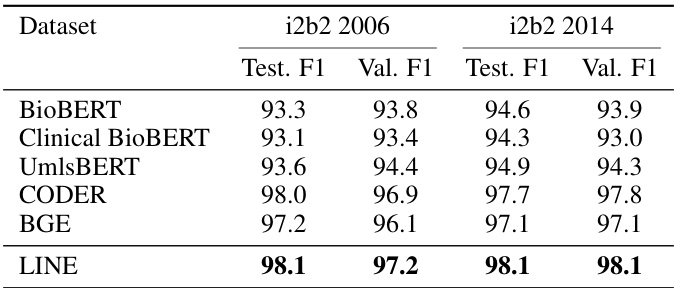

This table presents the mean F1 scores achieved by different models on two i2b2 datasets (i2b2 2006 and i2b2 2014). The models compared include BioBERT, Clinical BioBERT, UmlsBERT, CODER, BGE, and the proposed LINE model. The LINE model uses token-level BGE embeddings and the results are averaged over five runs with different random initializations. The best F1 scores for each dataset are highlighted in bold, allowing for easy comparison of model performance.

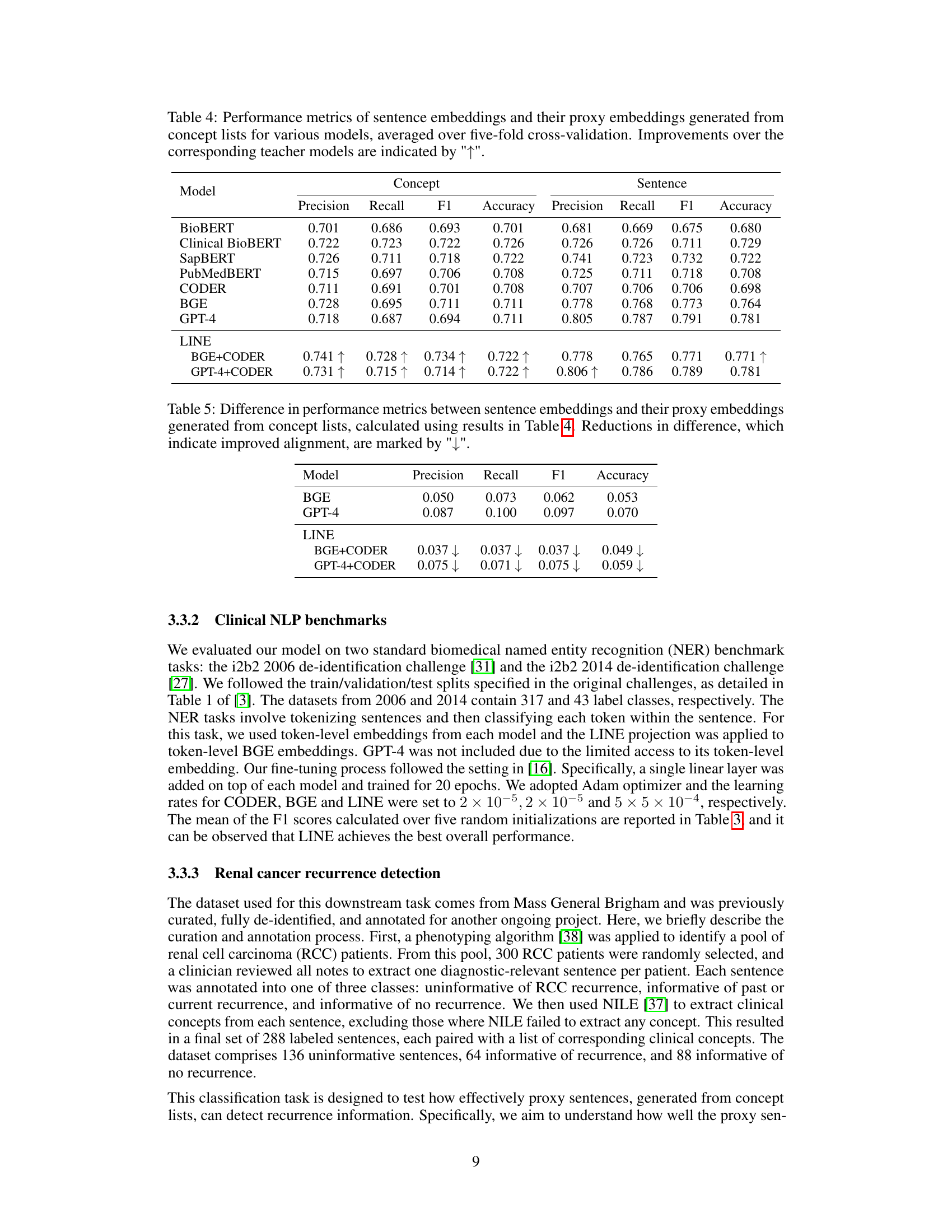

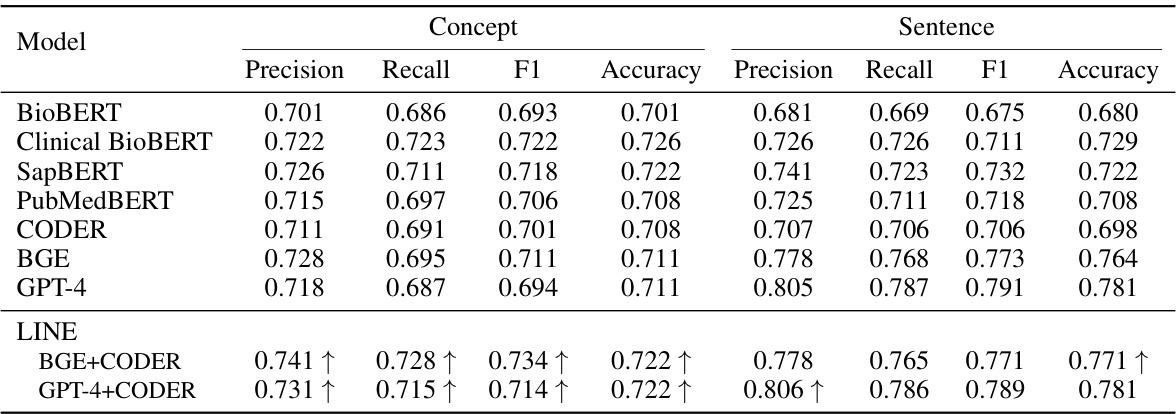

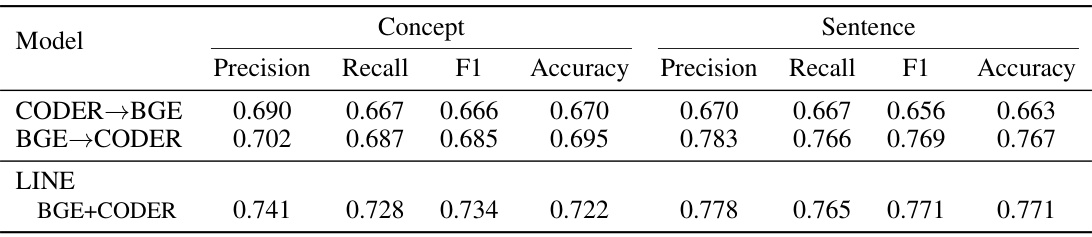

This table presents the performance of different models in generating sentence embeddings and proxy embeddings (from concept lists) using five-fold cross-validation. Metrics include precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy for both concept and sentence embeddings. The improvement of LINE over its base models is highlighted.

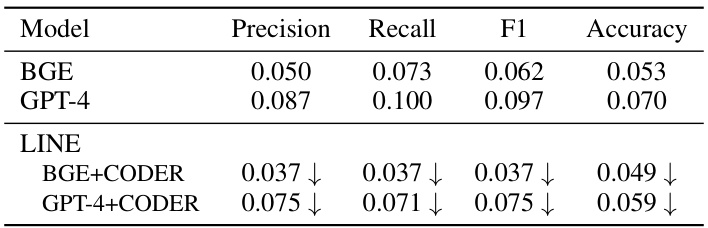

This table presents the differences in precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy between sentence embeddings and their proxy embeddings generated from concept lists. The results are calculated based on the data from Table 4. A reduction in the difference indicates that the alignment between the two types of embeddings has improved. The table shows the differences for two model configurations: BGE+CODER and GPT-4+CODER.

This table presents the results of an experiment to evaluate the alignment of clinical text and concept embeddings generated by different models. The experiment uses a contrastive approach, comparing the similarity of positive pairs (clinical text with its associated concepts) against negative pairs (clinical text with randomly selected concepts). The table shows the mean rank, mean reverse rank, and top-10 accuracy for each model, highlighting improvements achieved by the LINE framework.

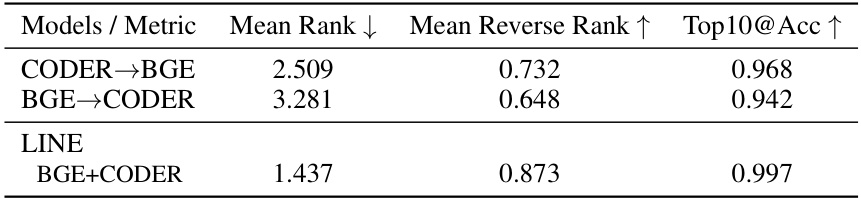

This table provides additional results for the alignment objective evaluation, comparing different models’ performance in aligning the embedding of clinical texts with their associated concept embeddings. The metrics used are Mean Rank, Mean Reverse Rank, and Top10@Acc, which measure the degree of alignment between positive and negative pairs. The table compares the performance of CODER→BGE, BGE→CODER, and the proposed LINE framework (BGE+CODER).

This table presents the performance comparison of different models in generating sentence embeddings and their proxy embeddings from concept lists. The models are evaluated using precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy metrics across five-fold cross-validation. Improvements achieved by the LINE model over its constituent teacher models are highlighted.

This table compares the performance of different models on two i2b2 datasets (i2b2 2006 and i2b2 2014) for a named entity recognition task. The models compared include BioBERT, Clinical BioBERT, UmlsBERT, CODER, BGE, and the proposed LINE model. The F1 score, a common metric for evaluating the performance of classification models, is reported for both the validation and test sets of each dataset. The LINE model uses token-level BGE embeddings, which are projected using the LINE module. The best F1 scores for each dataset and set (validation/test) are highlighted in bold.

Full paper#