↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current state-of-the-art models for unsupervised object discovery often struggle with complex scenes and rely on unreliable cues like color. These models typically employ complex-valued activations but real-valued weights in feedforward architectures, which are computationally limited and prone to errors. This paper addresses these limitations.

The proposed model, SynCx, is a fully convolutional recurrent autoencoder using complex-valued weights. SynCx uses iterative constraint satisfaction to achieve robust object binding simply through matrix-vector multiplication without any additional mechanisms. The results show that SynCx outperforms or is competitive with current state-of-the-art models, especially when color is unreliable for grouping. Its superior performance highlights the advantages of recurrent architecture and complex-valued weights for unsupervised object discovery.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it proposes a novel recurrent complex-weighted autoencoder, SynCx, that significantly improves unsupervised object discovery. Its simplicity and superior performance over existing models, particularly its robustness to color cues, make it a valuable contribution to the field. It opens up new avenues for research in object-centric learning and synchrony-based approaches.

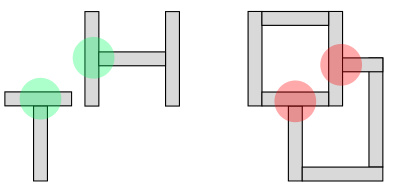

Visual Insights#

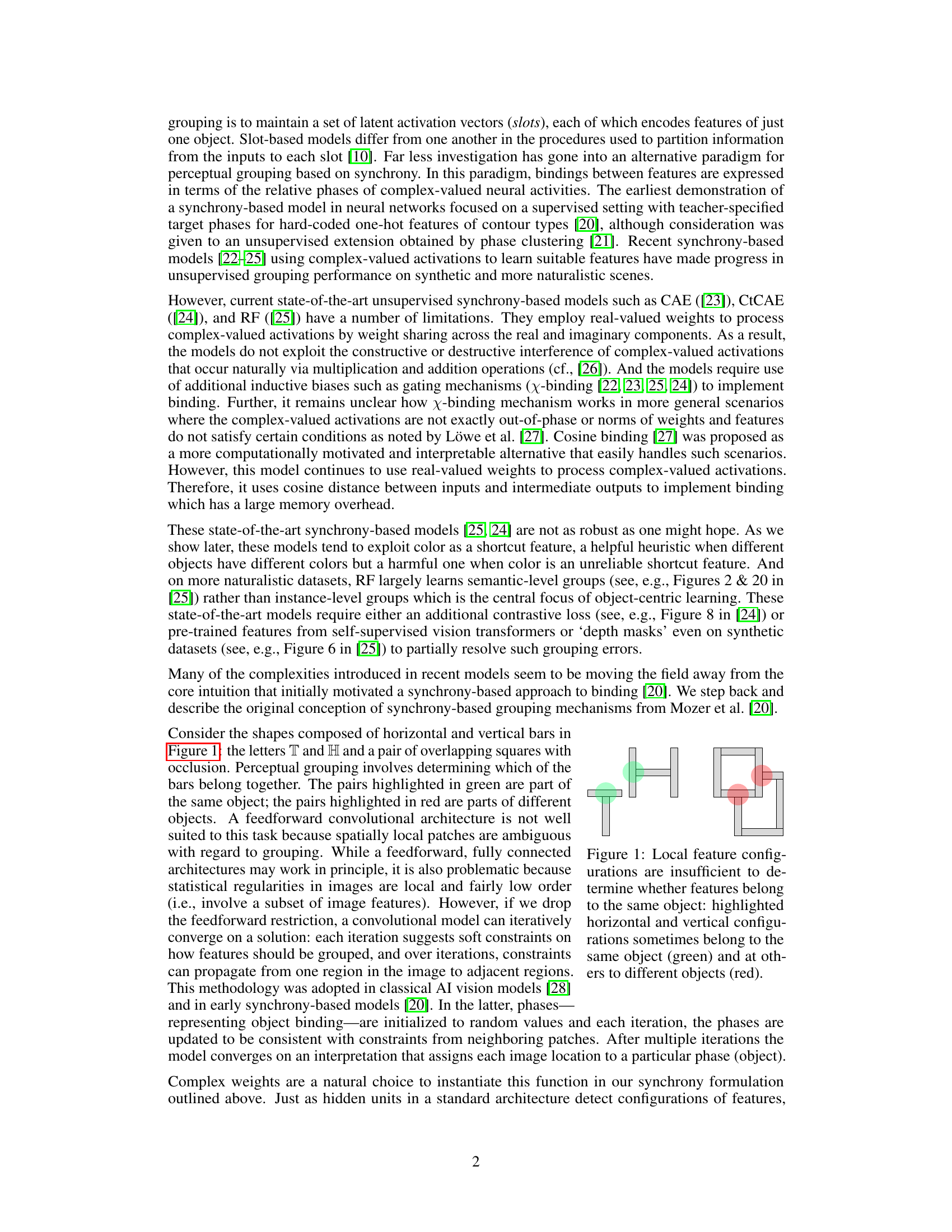

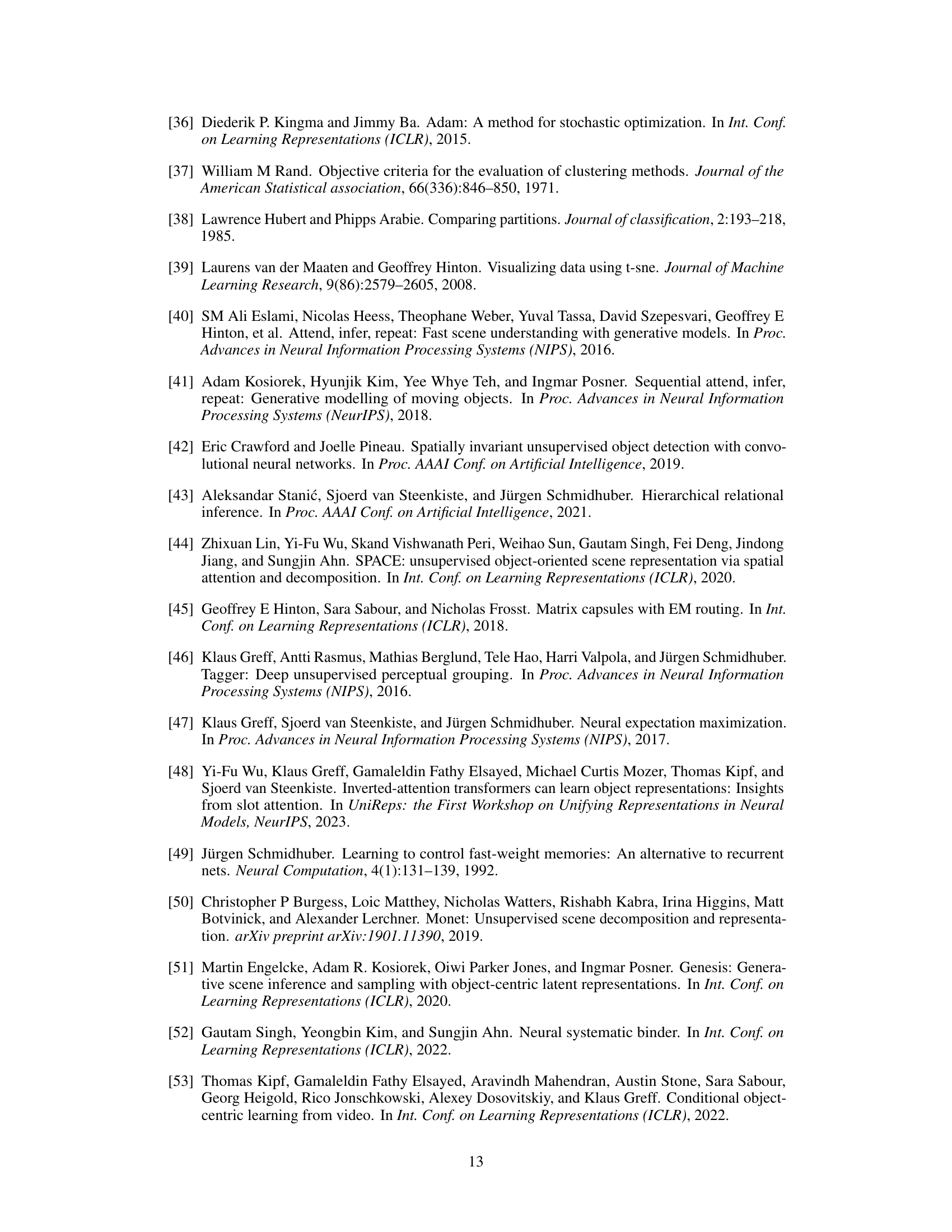

This figure illustrates the ambiguity of local image features regarding perceptual grouping. The example shows simple shapes (T, H, and overlapping squares) composed of horizontal and vertical bars. The green-highlighted bar pairs belong to the same object, while the red-highlighted bar pairs belong to different objects. This demonstrates the difficulty a feedforward convolutional network might face in discerning object boundaries based solely on local features, necessitating a more global or iterative approach.

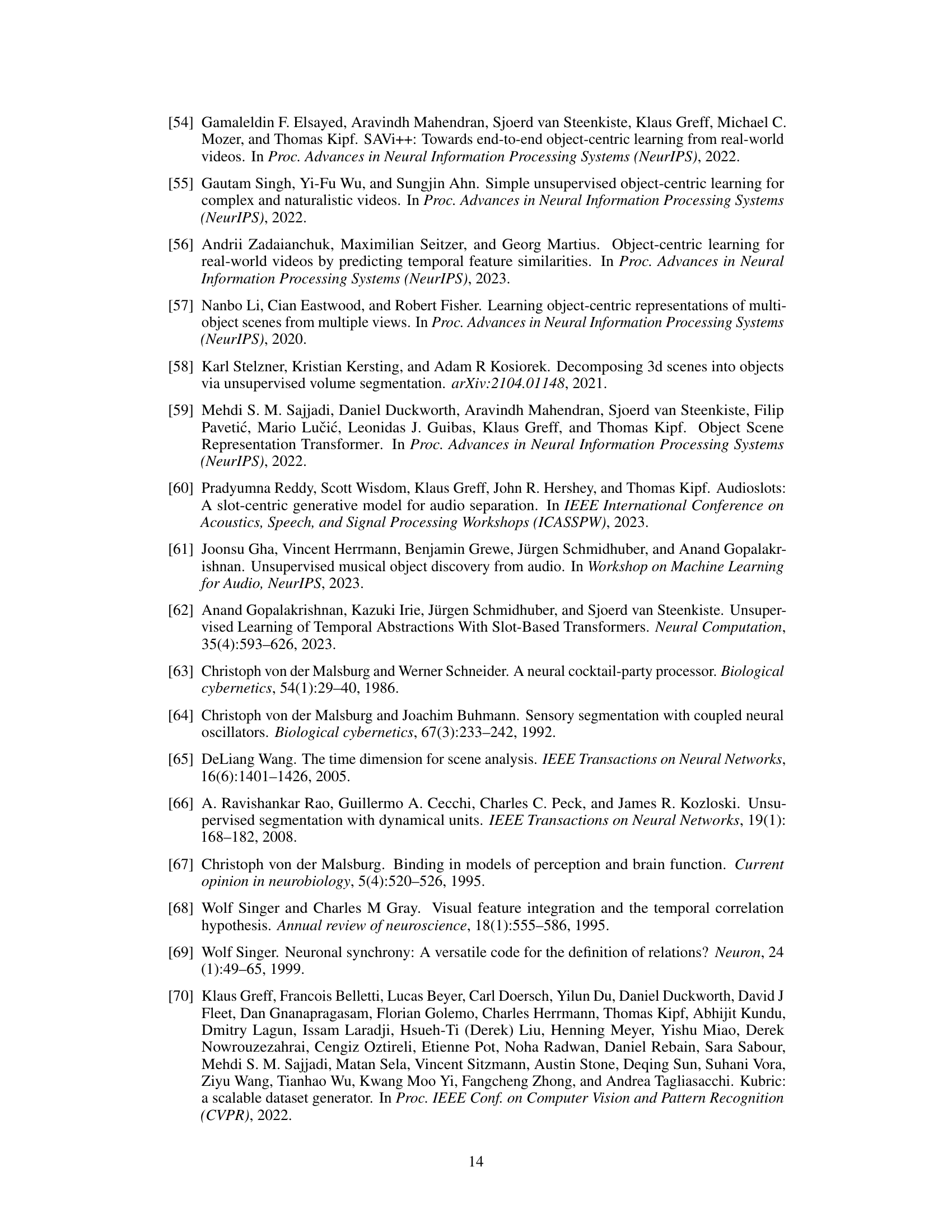

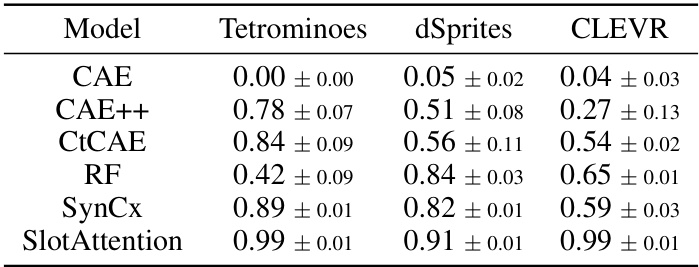

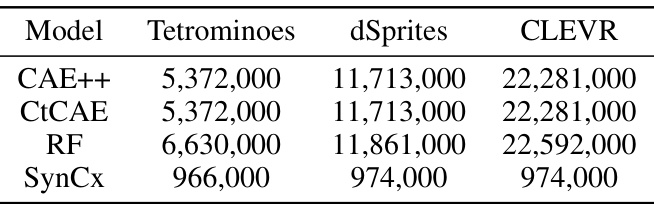

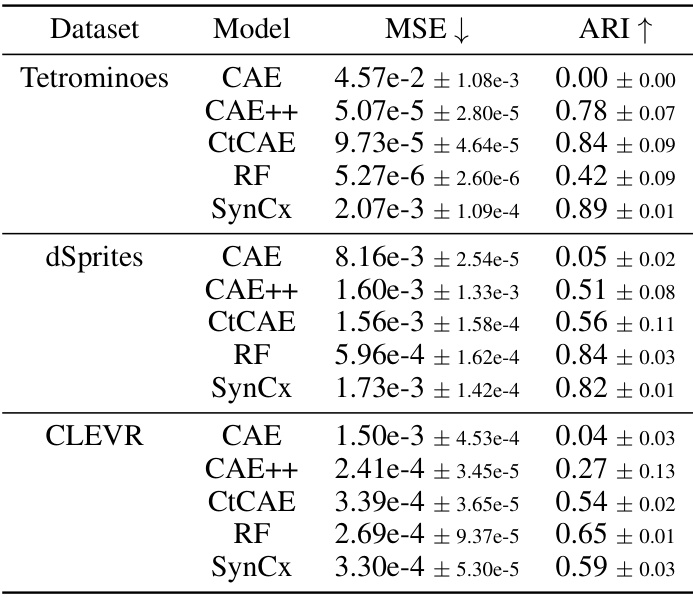

This table presents the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) scores achieved by different models on three datasets: Tetrominoes, dSprites, and CLEVR. ARI is used to measure the accuracy of object grouping. The models compared include CAE, CAE++, CtCAE, RF (all state-of-the-art synchrony-based models), SynCx (the proposed model), and SlotAttention (a state-of-the-art slot-based model). The results show SynCx’s performance compared to other models across the datasets and its relative strengths and weaknesses.

In-depth insights#

Complex Binding#

Complex binding in the context of this research paper likely refers to methods for representing and computing relationships between different features of an object or scene. Traditional methods struggle with this because it’s computationally expensive to encode the combinatorial possibilities. This paper explores complex-valued neural networks as a way to overcome this challenge. Using complex numbers (with real and imaginary parts), the network can naturally represent phase relationships between features. The binding problem is elegantly solved by multiplication operations. This allows the model to encode statistical regularities and learn how to combine features using interference patterns, similar to how the human visual system might bind features through neuronal synchrony. The use of recurrence further enhances the capacity for complex relationships and constraints propagation to aid in object discovery, which is essential for robust unsupervised learning. This approach offers a computationally efficient and elegant solution, avoiding the need for ad-hoc mechanisms like gating or contrastive training seen in other synchrony-based models. However, the paper also acknowledges limitations, particularly regarding the reliance on color cues in certain scenarios and the necessity of additional techniques for handling noisy data or complex scenes. Overall, the innovative approach to ‘complex binding’ presents a compelling argument for the use of complex-valued neural networks in addressing the binding problem.

Iterative Refinement#

The concept of “Iterative Refinement” in the context of unsupervised object discovery, as explored in the provided research paper, centers on the iterative process of adjusting phase relationships between features to achieve a globally consistent representation of objects. The core idea is that the model doesn’t directly solve the object binding problem in one step, but rather refines its understanding incrementally. Each iteration involves encoding statistically regular configurations of features and propagating local constraints across the model. This iterative approach allows for the gradual resolution of ambiguities and the convergence toward a globally coherent grouping of features. Complex-valued weights play a crucial role in this process, facilitating the encoding of phase relationships and the implementation of a natural binding mechanism through matrix-vector operations. Unlike simpler feedforward architectures, this iterative refinement allows for the propagation of information across the image and the correction of inconsistencies, leading to improved robustness and accuracy in the unsupervised object discovery task. The key advantage is that the model leverages the natural properties of complex numbers to encode relationships between features and avoid the need for supplementary mechanisms, which is a significant improvement over existing approaches. The iterative nature makes the method robust to noise and local inconsistencies, enabling more accurate object segmentation compared to single-step algorithms.

Bottleneck Impact#

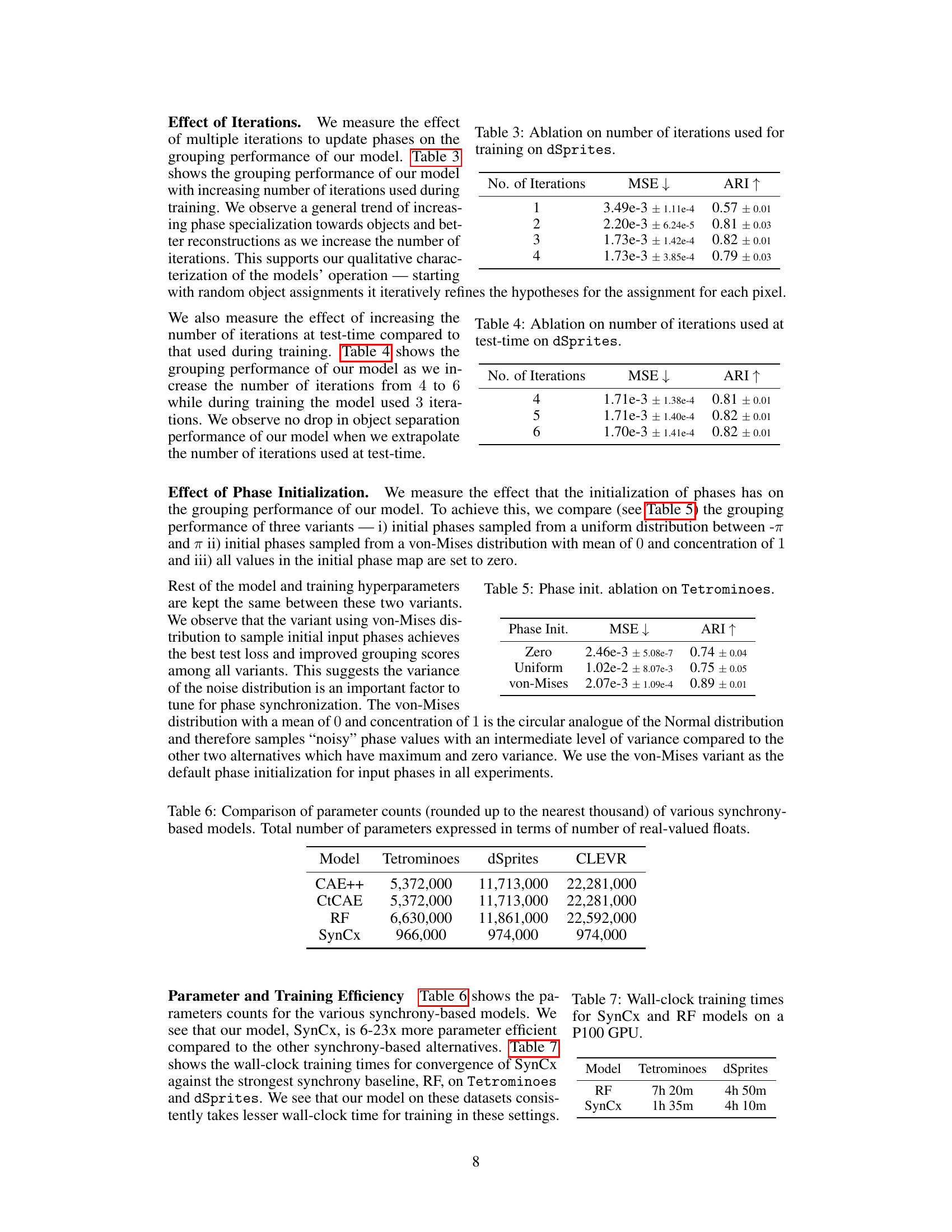

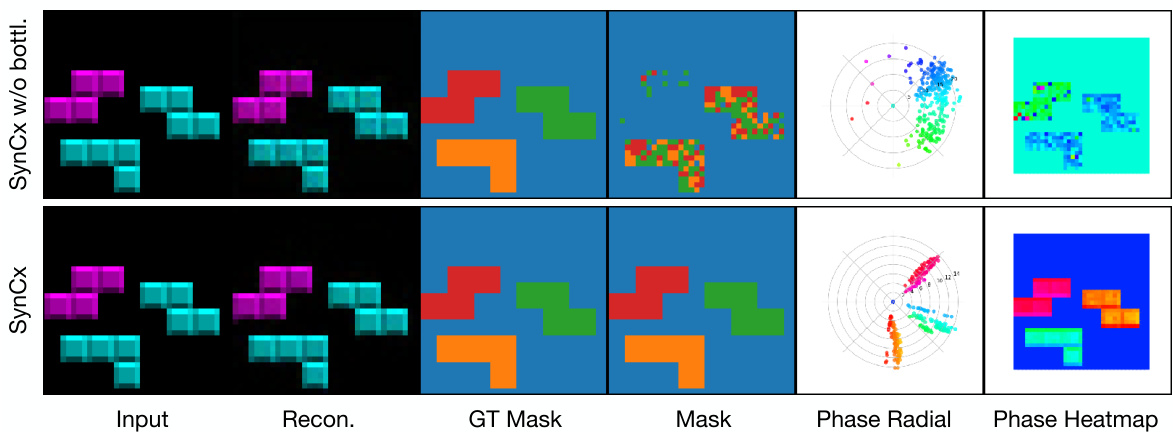

The experiment concerning bottleneck impact explores the effect of reducing the spatial resolution of feature maps in a model’s hidden layers. Reducing the spatial resolution acts as a bottleneck, forcing the model to learn more efficient representations to perform well. The results demonstrate a significant drop in grouping performance when bottlenecks are removed, suggesting that bottlenecks encourage the model to leverage phase relationships between features to achieve compression and improved object binding. This supports the hypothesis that the model’s ability to effectively separate objects, particularly those of similar color, relies on its ability to encode higher-order, phase-based relationships between features rather than solely relying on low-level feature distinctions. The bottleneck thus promotes the learning of more abstract and object-centric representations by constraining the model to utilize the phase information effectively. This finding highlights the importance of an appropriate level of abstraction and highlights that a carefully balanced bottleneck is crucial for successful unsupervised object discovery.

Phase Dynamics#

Phase dynamics in the context of object discovery using complex-valued neural networks is a fascinating area. The core idea revolves around representing object features not just by their magnitude (strength of activation), but also by their phase (relative timing or position within an oscillatory cycle). Changes in phase relationships between neurons can be interpreted as a form of communication or binding, enabling the network to dynamically associate features belonging to the same object, even if those features are spatially separated. The iterative nature of the proposed recurrent autoencoder allows for phase information to propagate across the network over time, leading to the gradual emergence of consistent phase relationships and, therefore, object segmentation. This is a departure from traditional feedforward architectures that rely heavily on spatial proximity or explicit mechanisms for linking features. The success of this approach hinges on the ability of the model to learn meaningful phase assignments that reflect underlying object structures, showing that the model encodes a holistic view of the data which is consistent with object formation in real life. The challenge lies in how to interpret and utilize this phase information effectively, and how to ensure that the learned phase dynamics are robust to noise and variations in input. A key research direction is to explore the connection between these computational phase dynamics and their potential biological relevance, particularly in the context of the brain’s mechanisms for perceptual binding and object recognition.

Future of SynCx#

The future of SynCx hinges on addressing its current limitations and capitalizing on its strengths. Improving robustness to color cues is crucial, potentially through architectural modifications that emphasize shape, texture, and spatial relationships more explicitly. Incorporating temporal dynamics would enhance its applicability to video data, allowing for the tracking of objects across frames. Exploring different phase initialization strategies could further optimize performance. Integration with other object-centric models could create a hybrid approach combining the benefits of both synchrony and slot-based methods. Finally, scaling SynCx to larger, more complex datasets and evaluating its performance on real-world images will be key to establishing its true potential as a robust and generalizable solution for unsupervised object discovery.

More visual insights#

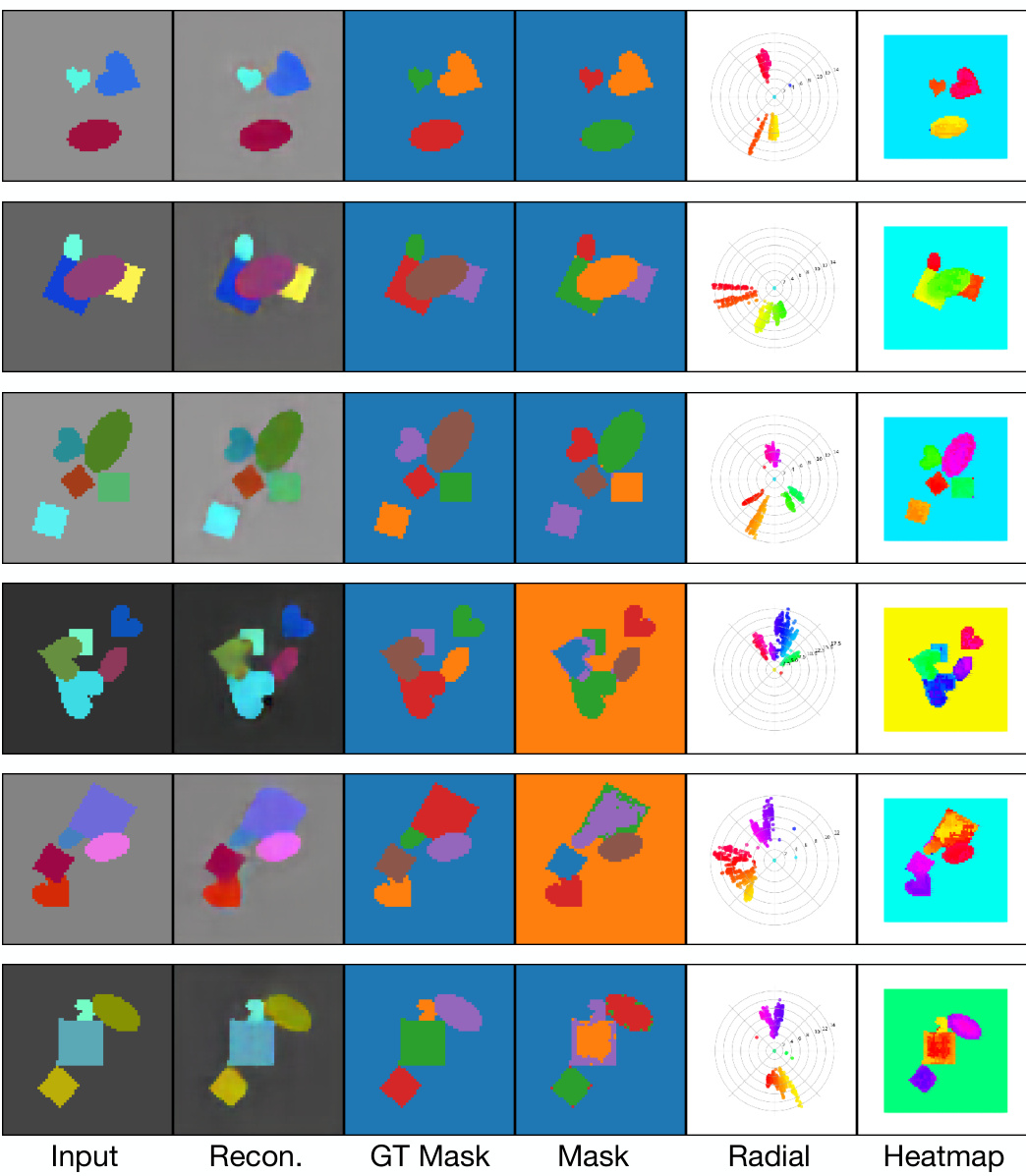

More on figures

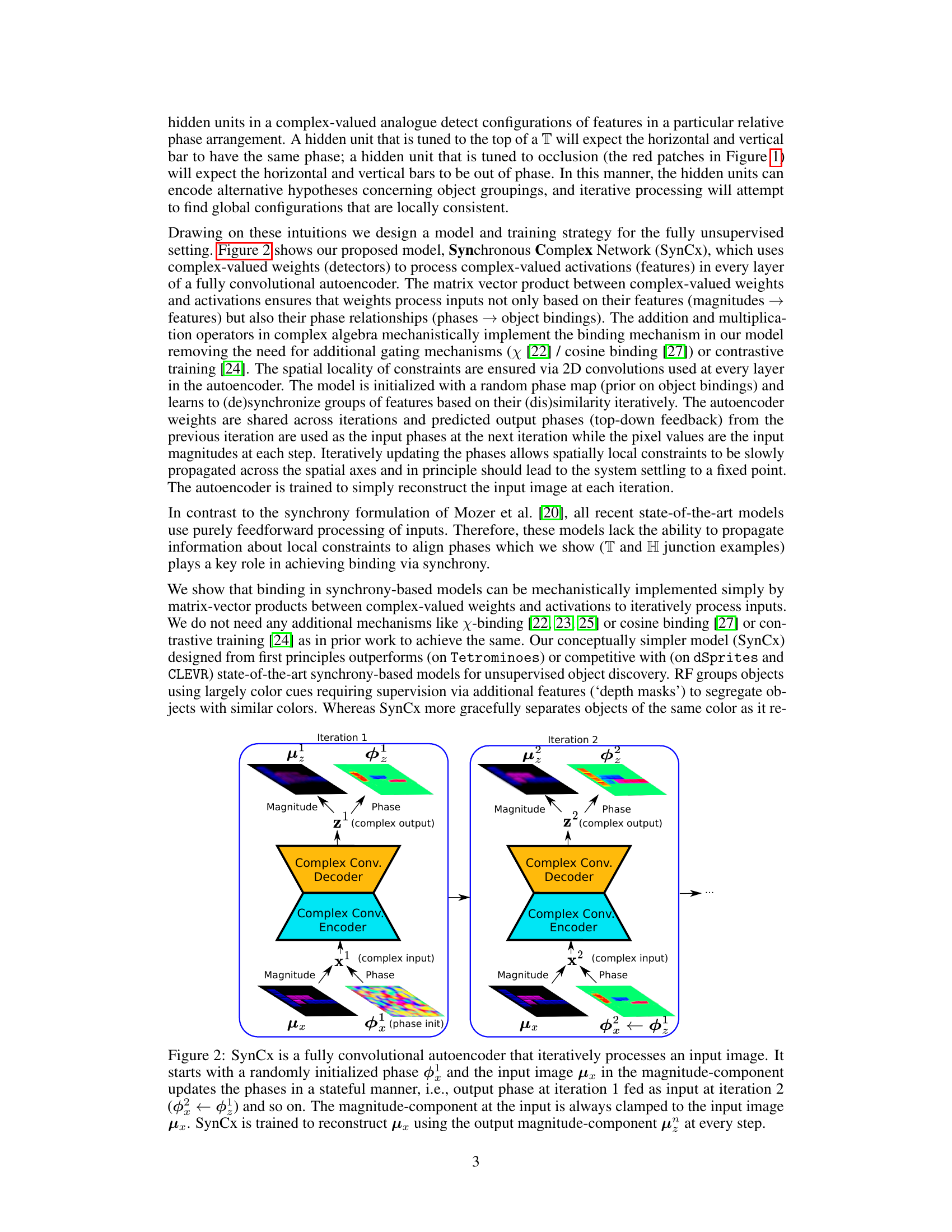

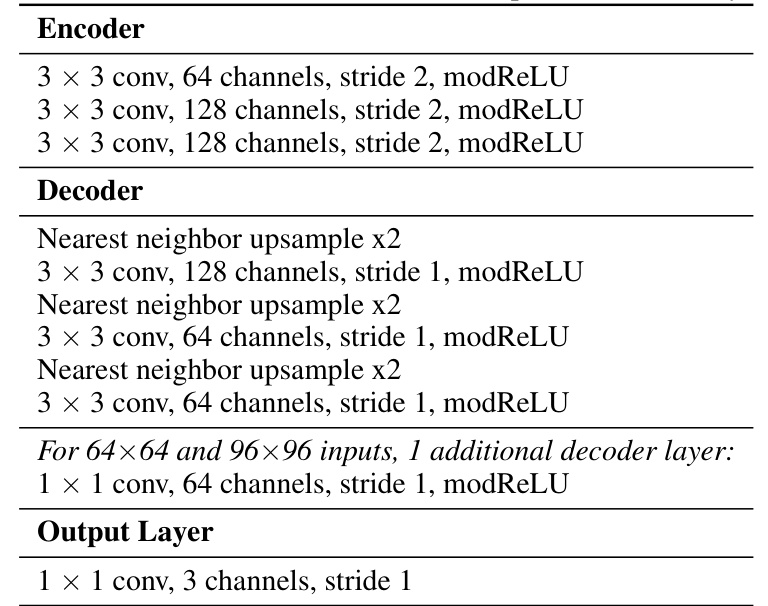

This figure illustrates the SynCx model, a fully convolutional autoencoder that iteratively processes input images. It uses complex-valued weights and activations. The model begins with random phase initialization (Φ¹) and iteratively refines these phases through multiple iterations. The input image’s magnitude (μˣ) remains constant across iterations, acting as a constraint. The output phase from one iteration becomes the input phase for the next (e.g., Φ¹ to Φ²), and the goal is to reconstruct the input image’s magnitude (μˣ) using the output magnitude (μᶻ) at each step. This iterative process allows for constraint propagation and the refinement of object groupings via phase relationships.

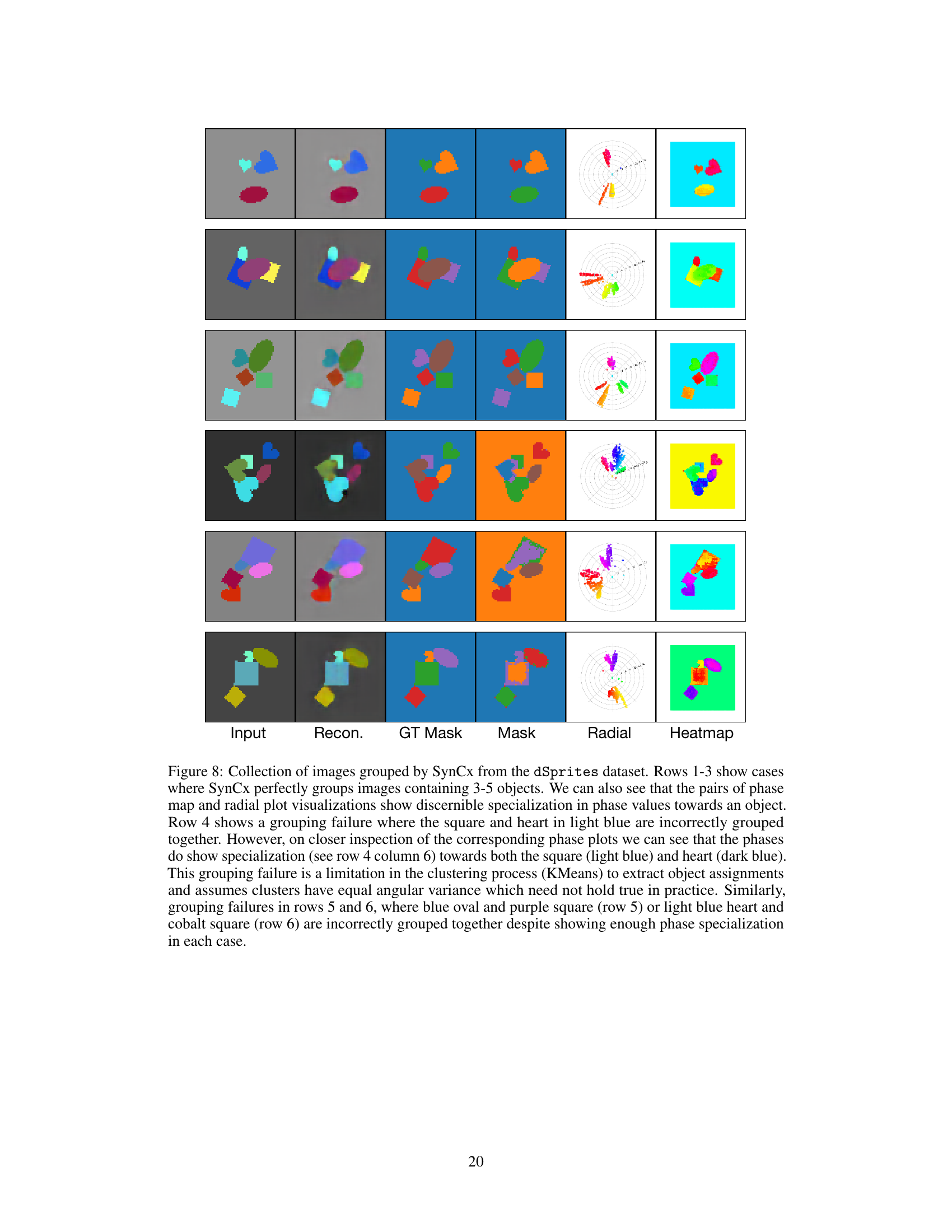

This figure visualizes the evolution of phase maps across iterations for two example inputs, one from the Tetrominoes dataset and one from the dSprites dataset. Each row represents a different dataset. For each input, the figure shows the input image, followed by the phase maps at iterations 1, 2, and 3. The phase maps are presented in two formats: a radial plot which shows the phase distribution spatially, and a heatmap which color-codes the phases. The evolution of the phase maps across iterations demonstrates how SynCx iteratively refines its object binding hypotheses. The color matching between the radial plots and heatmaps allows easy comparison.

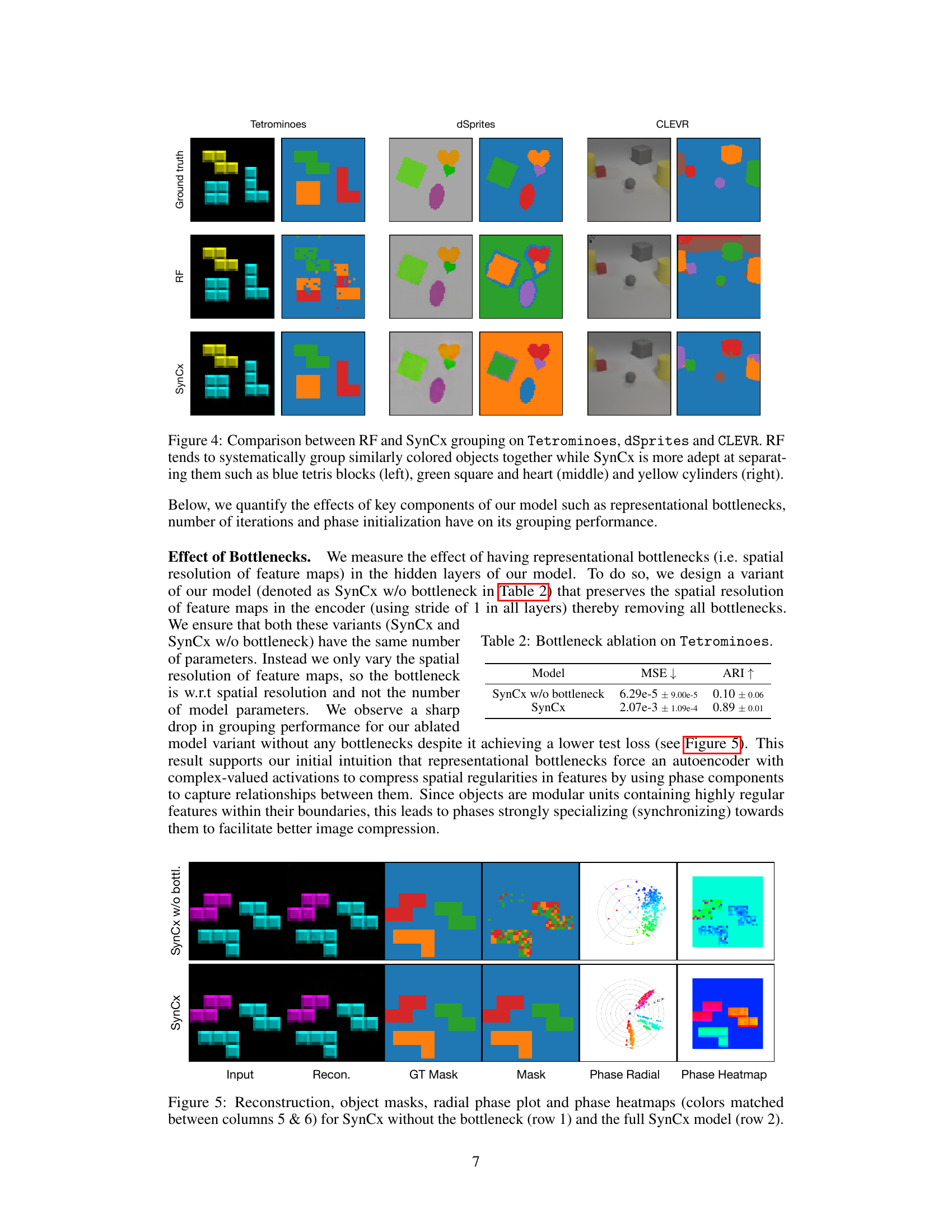

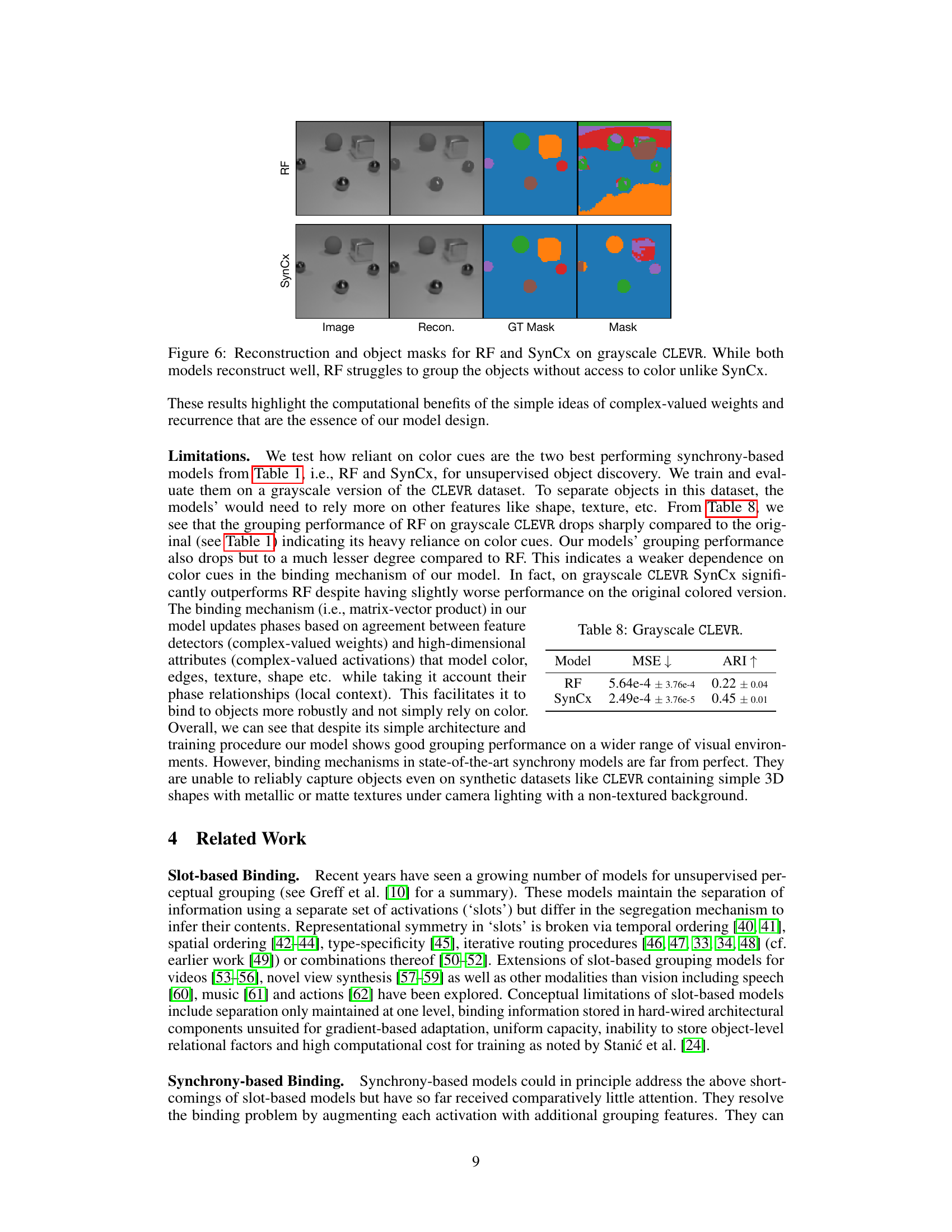

This figure compares the performance of RF and SynCx models on three different datasets: Tetrominoes, dSprites, and CLEVR. It visually demonstrates that RF tends to group objects based primarily on color, even when that leads to incorrect groupings. In contrast, SynCx demonstrates a superior ability to separate objects based on their shapes and spatial relationships, even those with similar colors. This highlights SynCx’s improved ability to perform unsupervised object discovery.

This figure shows the results of two versions of the SynCx model on the Tetrominoes dataset. The top row shows a version without a bottleneck, while the bottom row shows the full model with a bottleneck. The images compare the model’s reconstruction of the input image, the ground truth object masks, the model’s predicted object masks, a radial phase plot showing the phase distribution, and a heatmap visualization of the phases. The comparison demonstrates how the bottleneck affects the model’s ability to separate and group the objects based on phase synchronization, highlighting the importance of the bottleneck for successful object discovery.

This figure compares the performance of RF and SynCx models on three datasets: Tetrominoes, dSprites, and CLEVR. It highlights a key difference in how the models handle object grouping, specifically when objects share similar colors. RF shows a tendency to group objects based on color, even when they are distinct objects. SynCx, on the other hand, demonstrates a more refined ability to separate objects based on other features besides color, resulting in more accurate groupings.

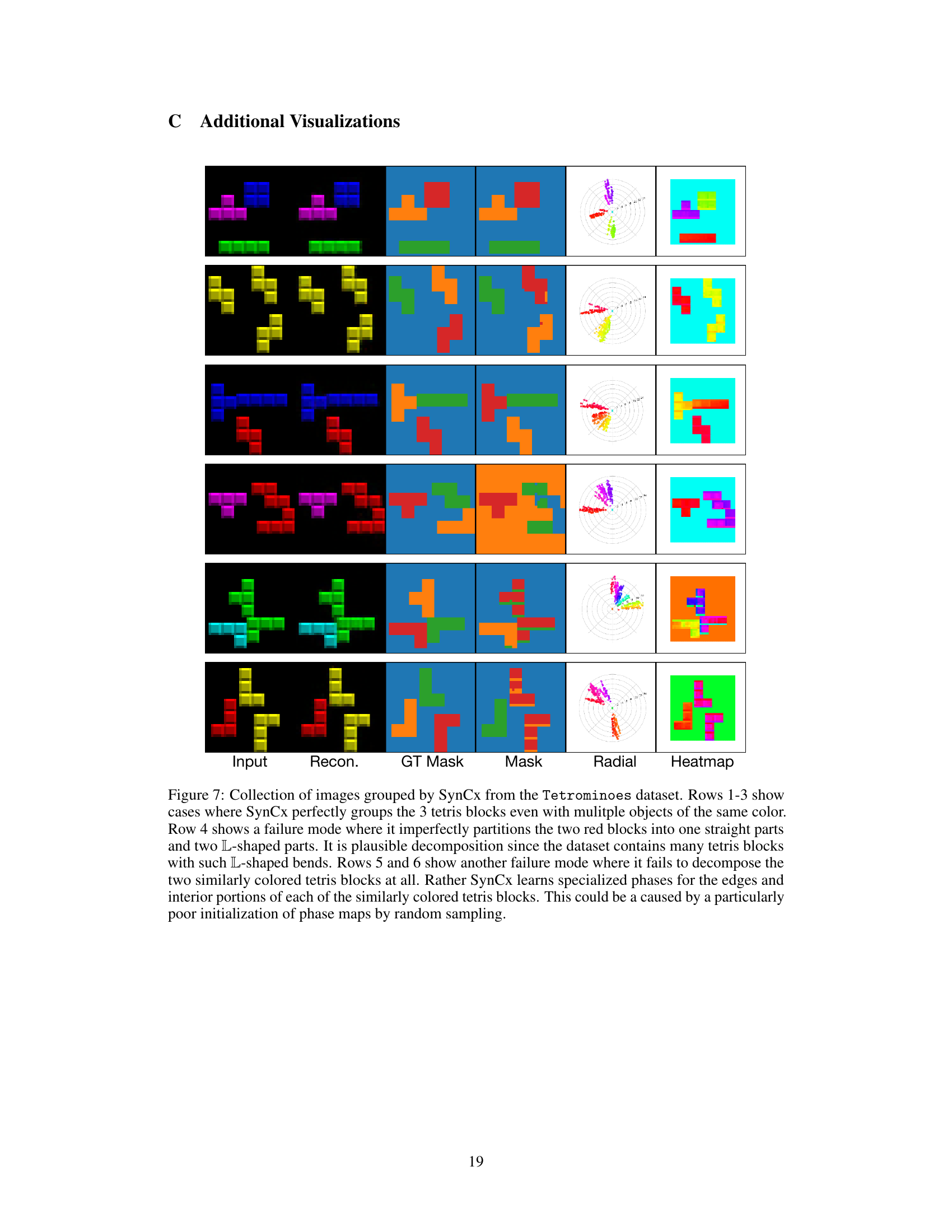

This figure shows several examples of how the SynCx model groups Tetrominoes. Most examples show successful grouping of the blocks, even when colors overlap. However, some examples illustrate cases where the model fails to correctly separate similarly colored objects. This is attributed to limitations in the model’s phase initialization.

This figure shows examples of how SynCx groups Tetrominoes. In most cases, it correctly groups the blocks, even when blocks share a color. However, there are some failure modes shown, where SynCx either incompletely separates blocks of the same color or fails to separate them at all. These failures may be due to the random initialization of phases.

This figure visualizes how the phase maps evolve across iterations during the SynCx model’s grouping process. It shows two examples, one from the Tetrominoes dataset and one from the dSprites dataset. The visualizations use heatmaps and radial plots of the phase components of the model’s complex-valued output to illustrate the progressive separation of phases corresponding to different objects. The color scheme is consistent between the heatmaps and radial plots, showing how the phases of features related to each object become more synchronized over iterations.

This figure compares t-SNE and UMAP for dimensionality reduction in visualizing phase maps. It shows examples where t-SNE effectively groups phases according to the number of objects, while UMAP does not. This highlights t-SNE’s superiority for this specific visualization task in the paper.

More on tables

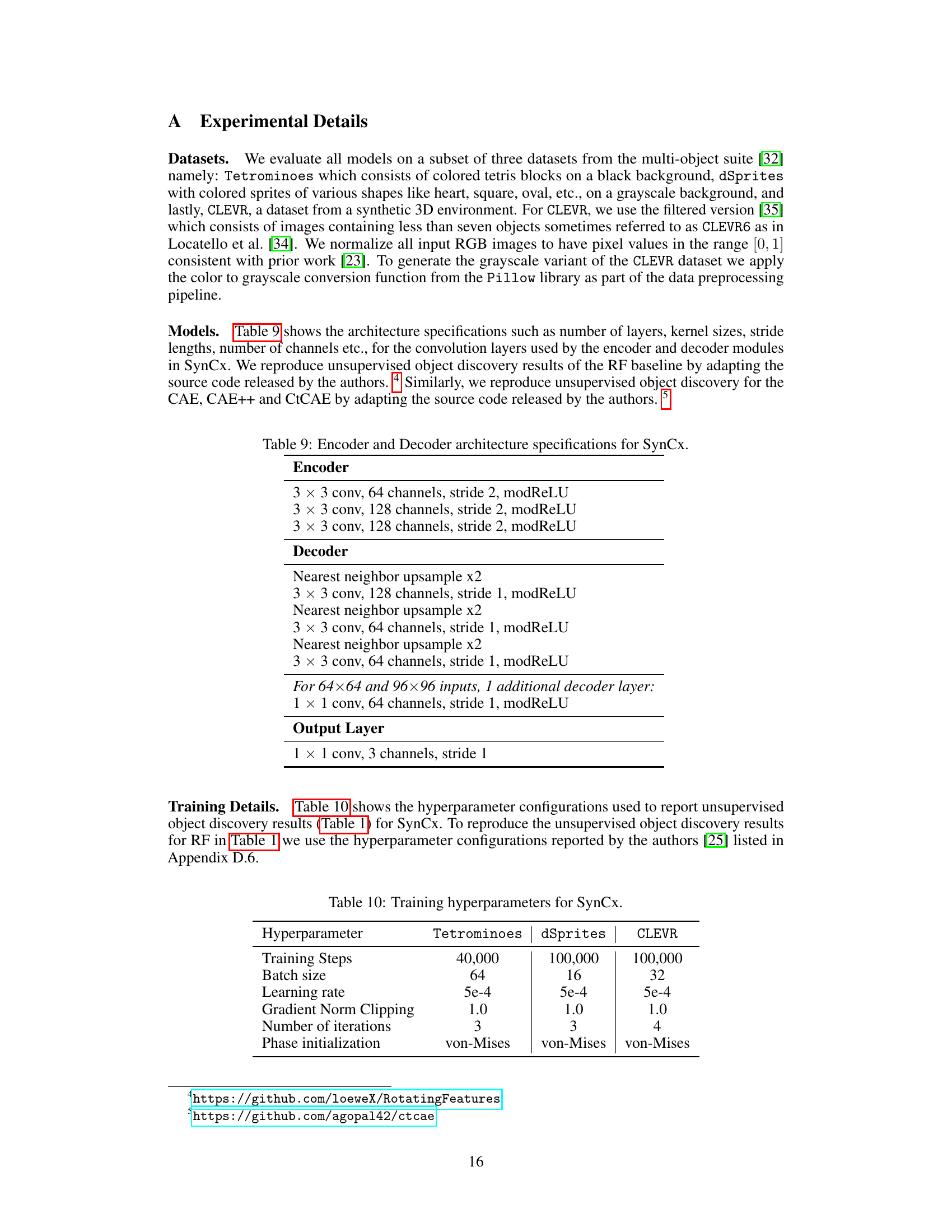

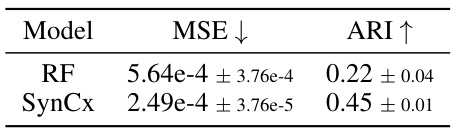

This table presents the result of an ablation study on the effect of bottlenecks in the SynCx model on the Tetrominoes dataset. It compares the mean squared error (MSE) and Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) for two model variants: SynCx with a bottleneck (the original model) and SynCx without a bottleneck (where the spatial resolution of feature maps is preserved). The results show a significant drop in ARI for the model without a bottleneck despite a lower MSE, suggesting that the bottleneck is crucial for effective object grouping by SynCx.

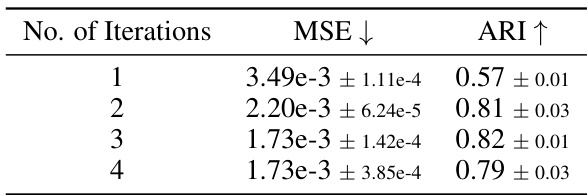

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the number of iterations used during training of the SynCx model on the dSprites dataset. It shows the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) for different numbers of iterations (1, 2, 3, and 4). The MSE measures the reconstruction error, while the ARI quantifies the accuracy of object grouping. Lower MSE indicates better reconstruction, and higher ARI suggests more accurate grouping. The results show that increasing the number of iterations generally improves grouping performance (ARI) but that the improvement diminishes after a certain point.

This table shows the effect of increasing the number of iterations at test time on the model’s performance. The model was trained using 3 iterations, and the test was performed with 4, 5, and 6 iterations to see if performance degraded. The results show that increasing the number of iterations at test time did not negatively impact performance.

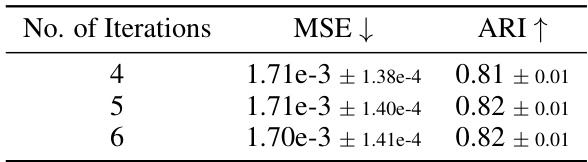

This ablation study compares the performance of three variants of the SynCx model with different phase initialization methods: zero, uniform, and von-Mises. The results show the mean and standard deviation of the MSE and ARI scores across 5 different random seeds for each phase initialization method. The von-Mises distribution shows the best performance, indicating that the variance of the noise distribution is important for phase synchronization in this model.

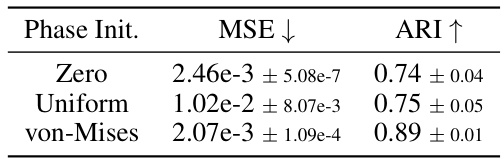

This table compares the number of parameters (in thousands) for different synchrony-based models across three datasets: Tetrominoes, dSprites, and CLEVR. The models compared are CAE++, CtCAE, RF, and the proposed SynCx model. The table highlights the significantly fewer parameters used in SynCx compared to the others.

This table shows the training time in hours and minutes for the SynCx and RF models on a P100 GPU for the Tetrominoes and dSprites datasets. It highlights the significant time savings achieved by SynCx compared to RF.

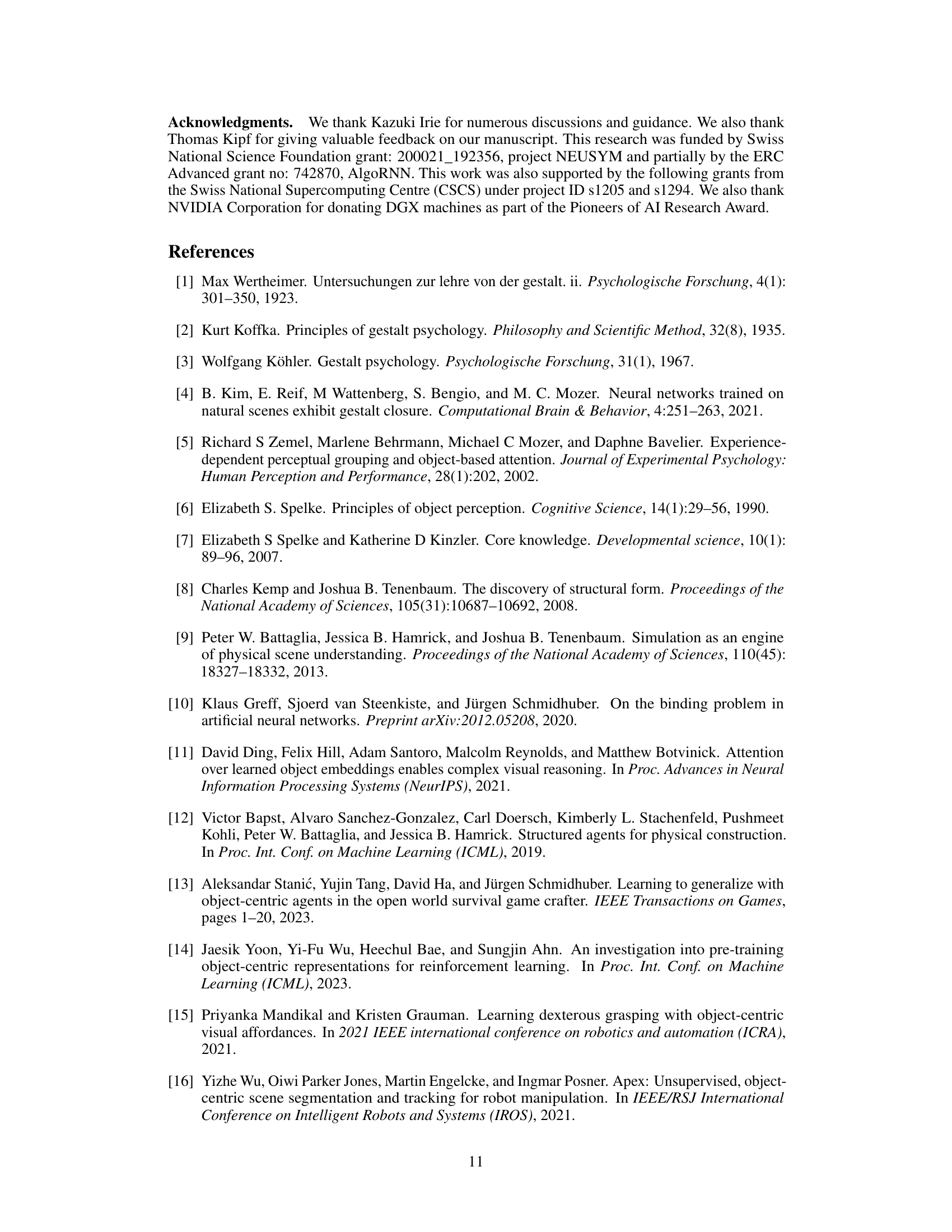

This table presents a comparison of the performance of RF and SynCx models on a grayscale version of the CLEVR dataset. It shows the mean squared error (MSE) and Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) for each model, highlighting the impact of removing color information as a shortcut cue on model performance. SynCx shows significantly better performance indicating it is less reliant on color cues for grouping compared to RF.

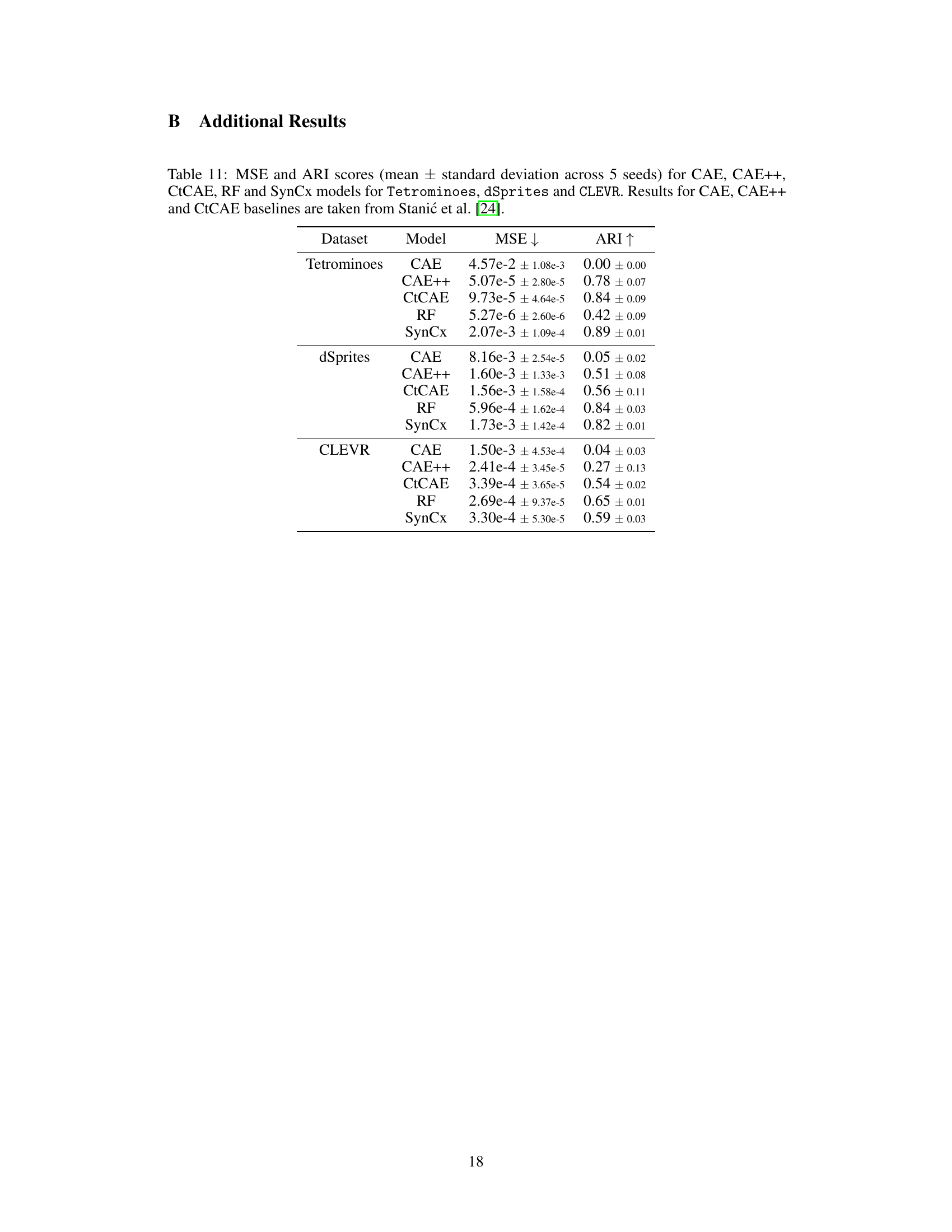

This table presents the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) scores achieved by different models on three datasets: Tetrominoes, dSprites, and CLEVR. ARI measures the similarity of the object groupings produced by the models compared to the ground truth. The table compares the performance of SynCx against other state-of-the-art synchrony-based models (CAE, CAE++, CtCAE, RF) and a leading slot-based model (SlotAttention). The scores are averaged over 5 different random seeds, with standard deviations also included, to provide a measure of robustness. The baseline model results from Stanić et al. [24] and Locatello et al. [34] are included for comparison purposes.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the SynCx model on three different datasets: Tetrominoes, dSprites, and CLEVR. The hyperparameters include the number of training steps, batch size, learning rate, gradient norm clipping, number of iterations, and phase initialization method. The values for each hyperparameter vary slightly depending on the dataset.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of several models on three different datasets (Tetrominoes, dSprites, and CLEVR) using the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) as a metric for evaluating unsupervised object discovery. The models compared include CAE, CAE++, CtCAE, RF, SynCx, and SlotAttention. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of ARI scores across five different seeds for each model and dataset. The results from Stanić et al. [24] and Locatello et al. [34] are included for comparison.

Full paper#