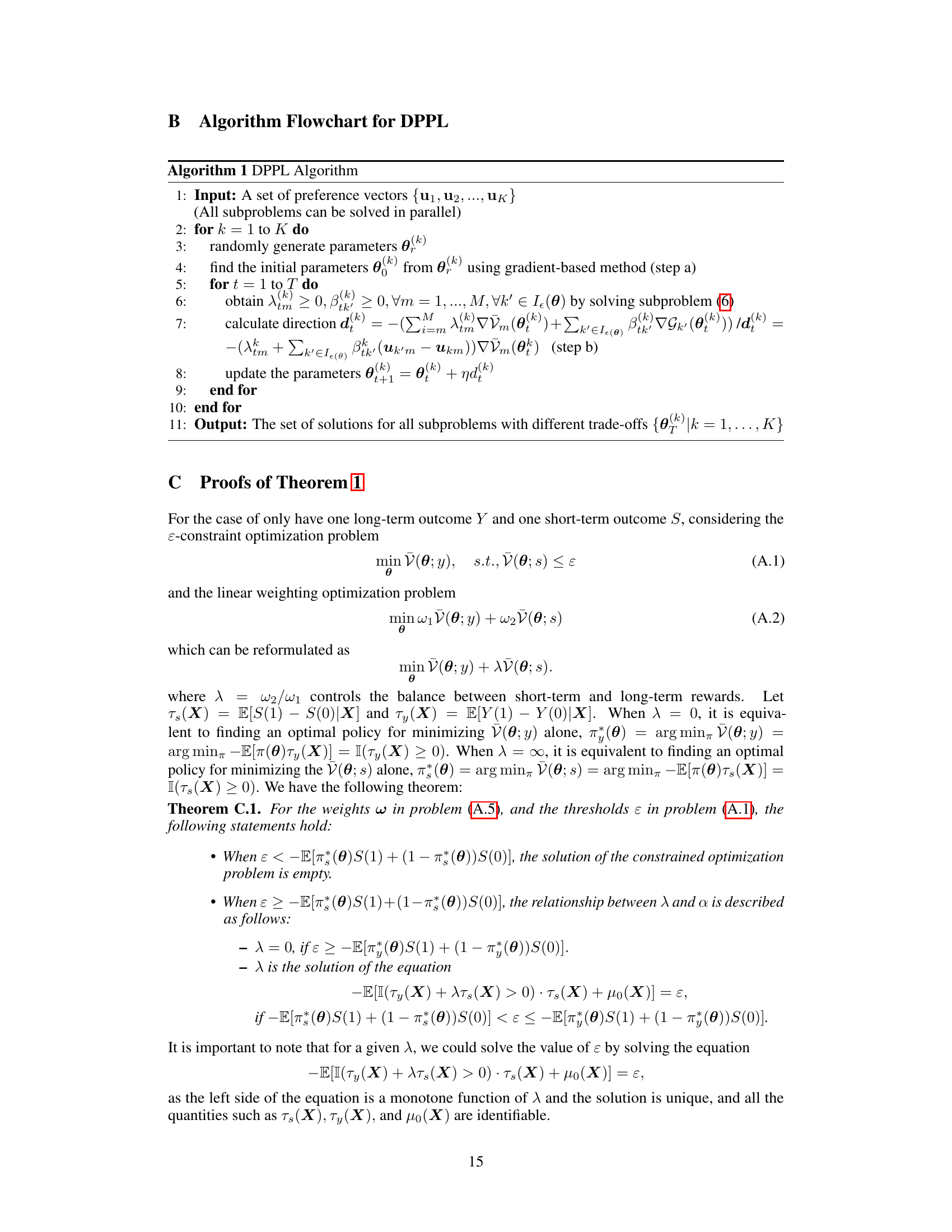

↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world applications require policies that effectively balance short-term and long-term rewards. However, existing linear weighting methods often fail to achieve optimality, especially when rewards are interconnected. This limitation is particularly problematic when long-term data is scarce due to the time and cost associated with data collection.

This paper introduces a novel Decomposition-based Policy Learning (DPPL) method to overcome these issues. DPPL decomposes the complex optimization problem into smaller, more manageable subproblems, allowing it to find optimal policies even with interconnected rewards and limited long-term data. The method’s effectiveness is demonstrated through extensive experiments, and its connection to the ε-constraint problem provides a practical framework for selecting appropriate preference vectors, adding to its utility and ease of implementation. The DPPL method represents a significant step towards achieving optimal, robust policies in situations where balancing multiple and potentially related rewards is crucial.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it tackles the significant challenge of balancing short-term and long-term rewards in policy learning, a crucial problem across many domains. It offers a novel solution, DPPL, showing improvements over existing methods. The theoretical connection to the ε-constraint problem provides practical guidance for choosing preference vectors, thus enhancing the applicability of the method and offering new avenues for research in multi-objective optimization and causal inference.

Visual Insights#

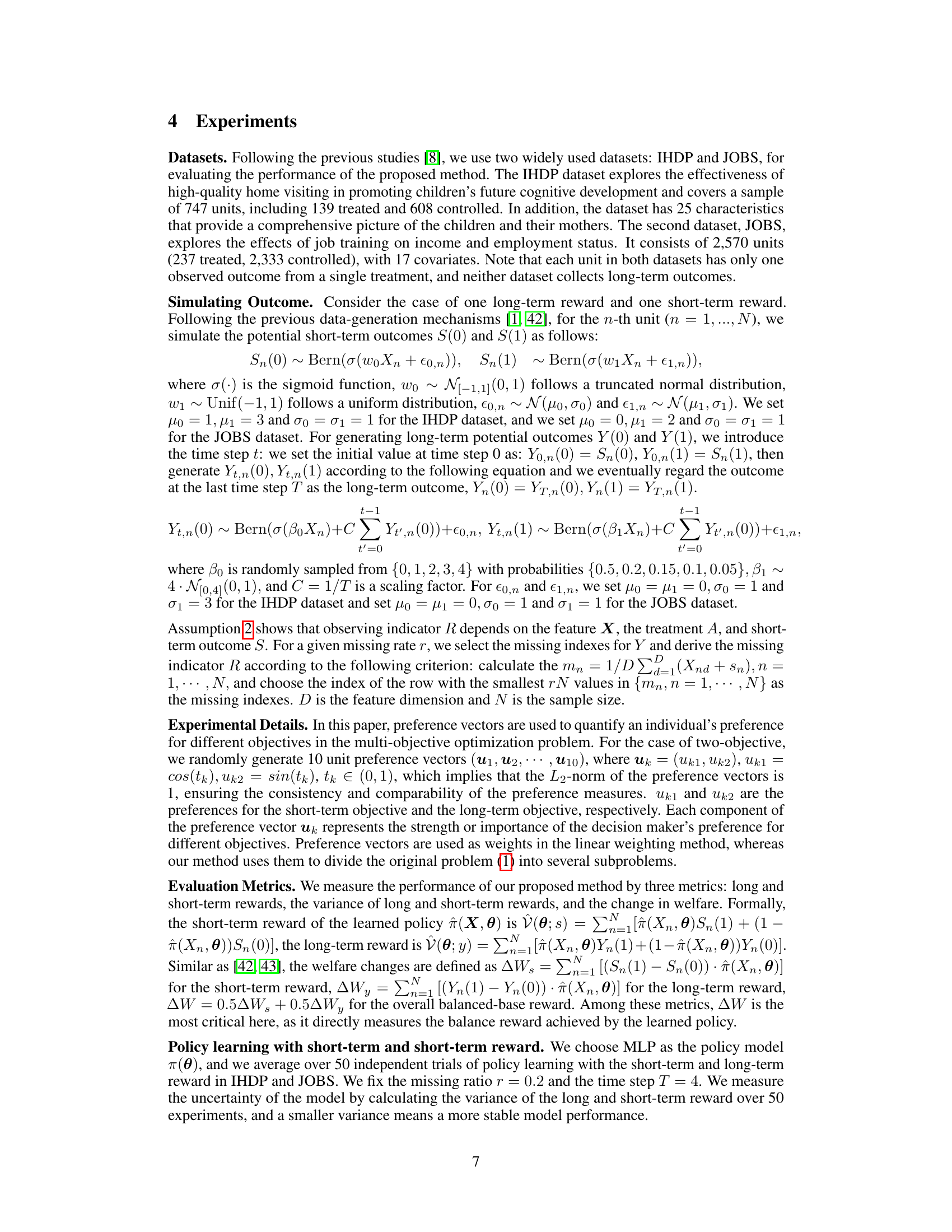

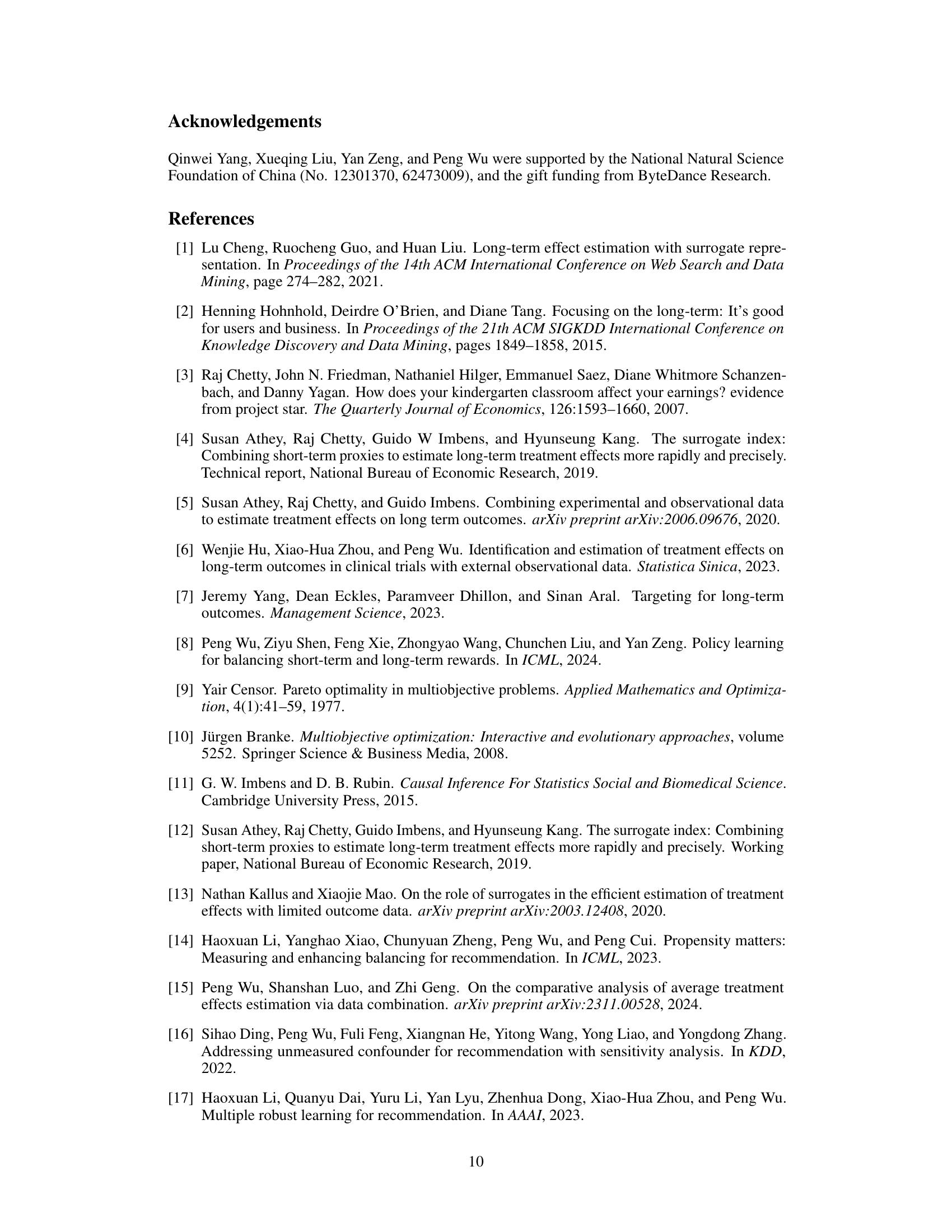

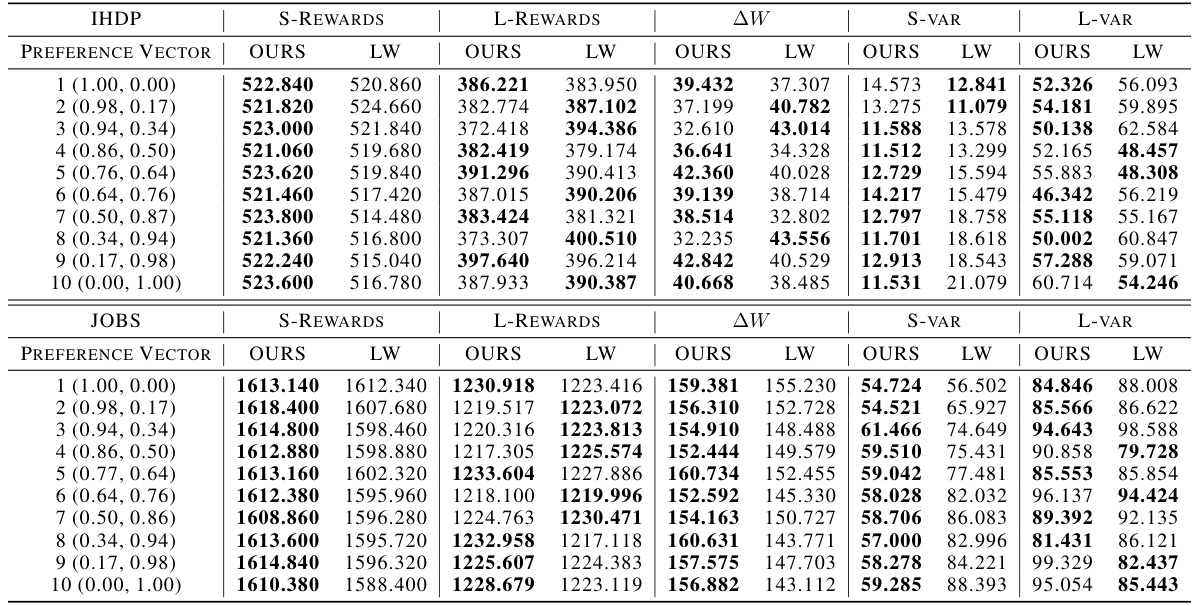

This figure compares the performance of the proposed DPPL method and the linear weighting method on the JOBS dataset under different missing ratios (0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5) for balancing short-term and long-term rewards. For each missing ratio, the plot shows the average welfare change (Delta_W) achieved by each method across ten different preference vectors. The x-axis represents the index of the preference vector and the y-axis represents the welfare change, which reflects the effectiveness of the methods in balancing multiple objectives. The results demonstrate the superiority of the DPPL method over the linear weighting method in terms of achieving higher welfare change, particularly under higher missing ratios.

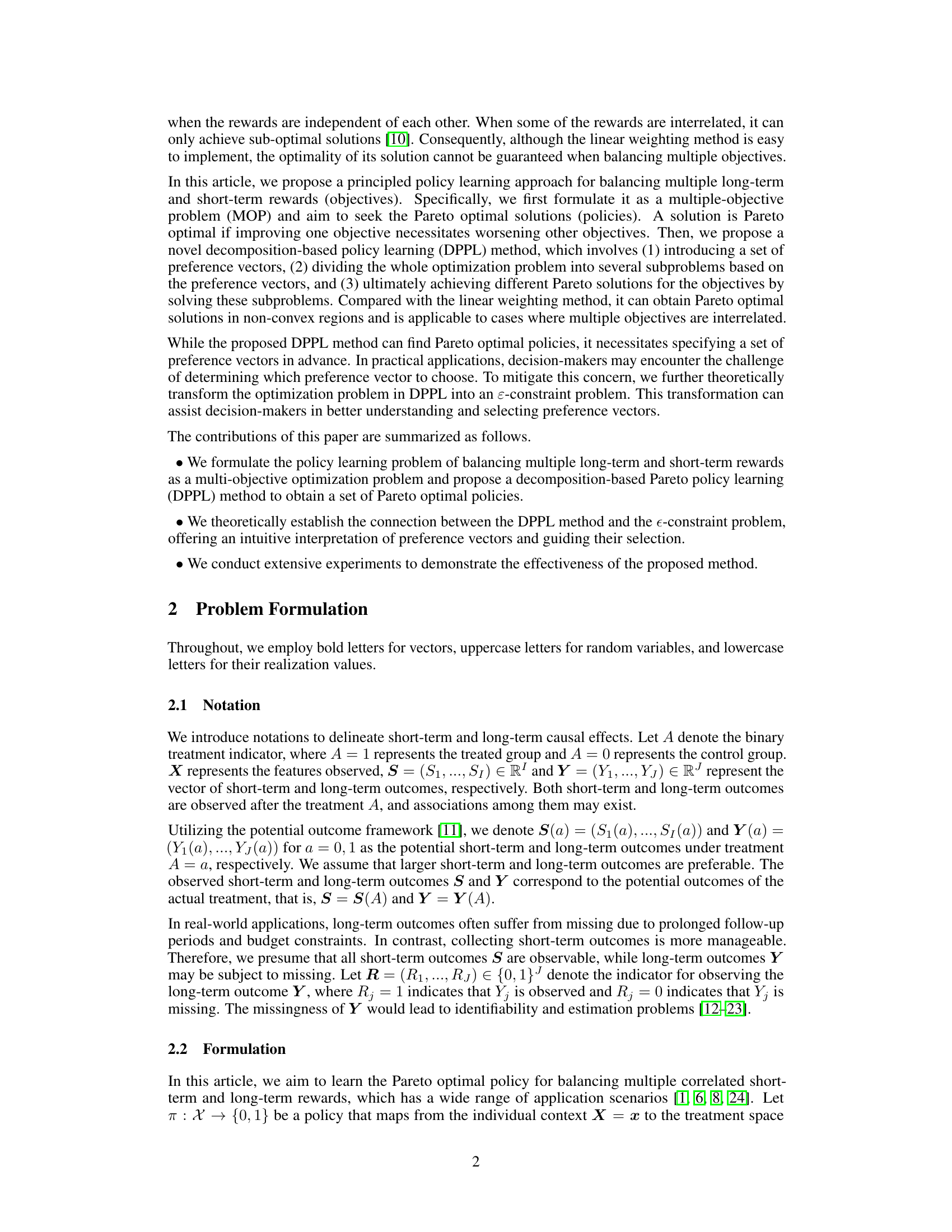

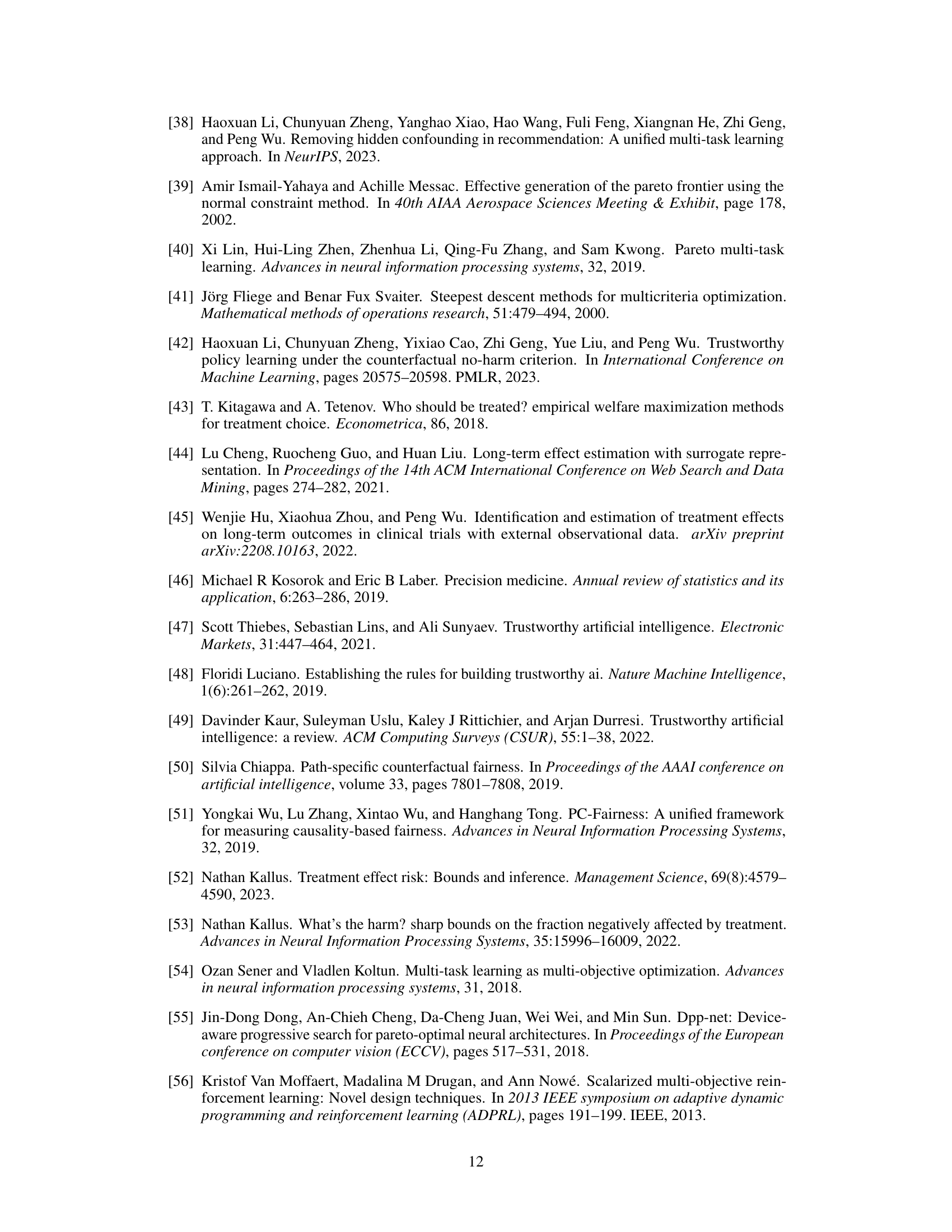

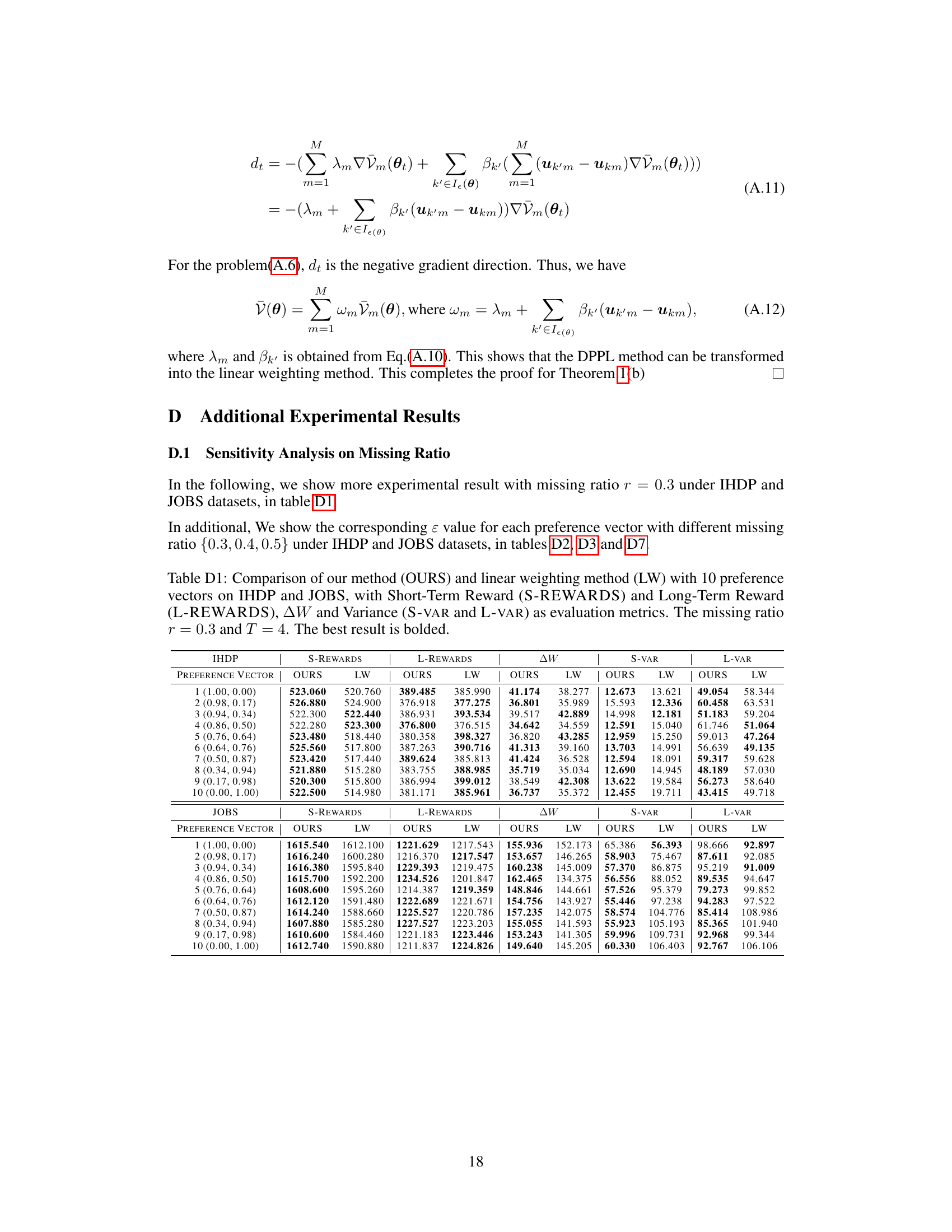

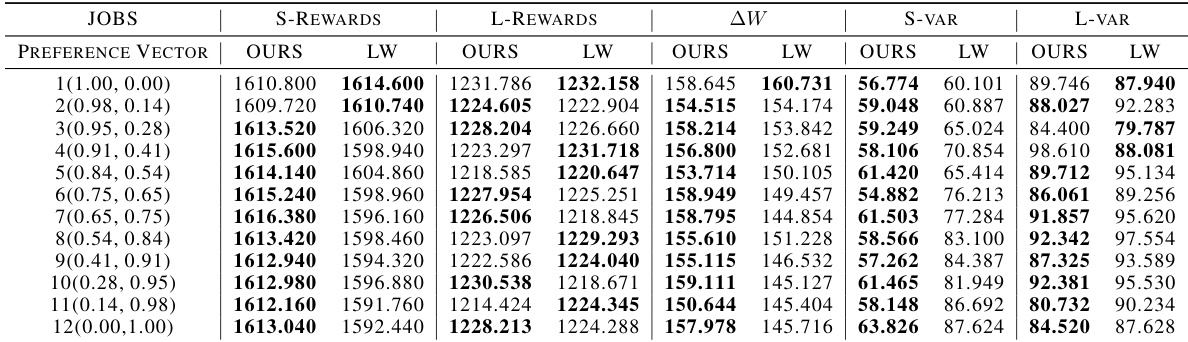

This table compares the performance of the proposed Decomposition-based Policy Learning (DPPL) method and the Linear Weighting method on two datasets (IHDP and JOBS). It shows the short-term rewards, long-term rewards, the change in welfare (AW), and the variance of short-term and long-term rewards for each method across ten different preference vectors. The best performing method for each metric is highlighted in bold. This helps to demonstrate the effectiveness of the DPPL method in balancing short-term and long-term rewards, especially when compared to the simpler linear weighting approach.

In-depth insights#

Reward Balancing#

Reward balancing in reinforcement learning (RL) presents a significant challenge, especially when dealing with conflicting short-term and long-term objectives. The core problem lies in designing policies that achieve a desirable balance between immediate gratification and delayed, potentially more significant, rewards. A naive approach of simply summing weighted rewards often fails, particularly when rewards are interdependent. Sophisticated methods like decomposition-based policy learning (DPPL) aim to overcome this by breaking down the problem into more manageable subproblems, each focused on optimizing a specific aspect of the reward structure. However, even advanced techniques face hurdles. DPPL requires predefined preference vectors, which represent subjective prioritization of rewards, and selecting these vectors appropriately can be challenging. Connecting DPPL to the epsilon-constraint method provides a theoretical framework for selecting more intuitive preference vectors, allowing for a more principled and effective reward balancing strategy. This ultimately leads to better-performing agents capable of navigating complex reward landscapes successfully.

DPPL Method#

The core of this research paper revolves around the proposed Decomposition-based Policy Learning (DPPL) method for balancing short-term and long-term rewards in policy learning. DPPL addresses the limitations of traditional linear weighting methods, which often yield suboptimal policies when rewards are interdependent. DPPL’s key innovation lies in decomposing the complex problem into smaller, more manageable subproblems, each guided by a preference vector. This decomposition allows the algorithm to find Pareto optimal policies, even in non-convex objective spaces. While effective, DPPL requires pre-specified preference vectors, introducing a challenge in practical applications. To address this, the authors elegantly transform the DPPL optimization into an ε-constraint problem, providing a more intuitive way to select preference vectors and interpret the resulting trade-offs between rewards. The theoretical connection between DPPL and the ε-constraint problem is a significant contribution, enhancing the method’s practicality and interpretability. Experimental results on real-world datasets validate the effectiveness of DPPL in achieving better balance and stability compared to existing methods.

Preference Vectors#

Preference vectors are crucial for the decomposition-based policy learning (DPPL) method proposed in the paper. They represent the decision-maker’s preferences among multiple, often conflicting, short-term and long-term rewards. The choice of preference vectors directly influences the resulting Pareto optimal policies, as each vector guides the optimization process toward a specific trade-off between objectives. The paper acknowledges the non-trivial nature of selecting these vectors in practice. Therefore, it establishes a crucial theoretical link between the preference vectors and the epsilon-constraint problem. This helps decision-makers understand the implication of their choices, making the selection process more intuitive and informed. The DPPL method’s effectiveness hinges on appropriately chosen preference vectors; the epsilon-constraint transformation provides an insightful framework for selecting them, bridging the gap between theoretical optimality and practical implementation.

Empirical Analysis#

An empirical analysis section in a research paper would typically present the results of experiments designed to test the paper’s hypotheses or claims. It should meticulously describe the datasets used, clearly detailing their characteristics and any preprocessing steps. The experimental setup needs to be explained, including the methodology, parameters, and evaluation metrics. A robust analysis requires comparing the proposed method’s performance against relevant baselines, demonstrating its advantages or unique capabilities. The results should be presented with appropriate visualizations, such as graphs or tables, and statistical significance should be addressed (e.g., p-values, confidence intervals). Crucially, the analysis should connect the empirical findings back to the theoretical claims and discuss the observed limitations and potential biases. A thoughtful analysis goes beyond merely reporting numbers; it interprets the results in context, providing insights into the research problem and suggesting directions for future work. The inclusion of sensitivity analyses demonstrating the robustness of results to variations in parameters or data conditions further strengthens the empirical analysis.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending the DPPL method to handle continuous treatments would significantly broaden its applicability. Currently limited to discrete treatments, expanding to continuous scenarios would unlock a wider range of real-world applications where treatment intensity is a key variable. Another crucial direction involves developing more sophisticated methods for selecting preference vectors. While the ɛ-constraint approach provides helpful intuition, more robust and data-driven techniques could enhance the practical applicability of the DPPL method. Investigating the impact of different missingness mechanisms on long-term outcome estimation is also vital. The current assumptions might not always hold in real-world settings, therefore, a more robust framework that accounts for various forms of missing data is necessary. Finally, applying the DPPL framework to diverse domains such as personalized medicine, recommendation systems, and reinforcement learning could demonstrate its generalizability and highlight unique challenges and opportunities in each field. These investigations would add to a robust and flexible framework for balancing multiple short-term and long-term rewards in complex decision-making problems.

More visual insights#

More on tables

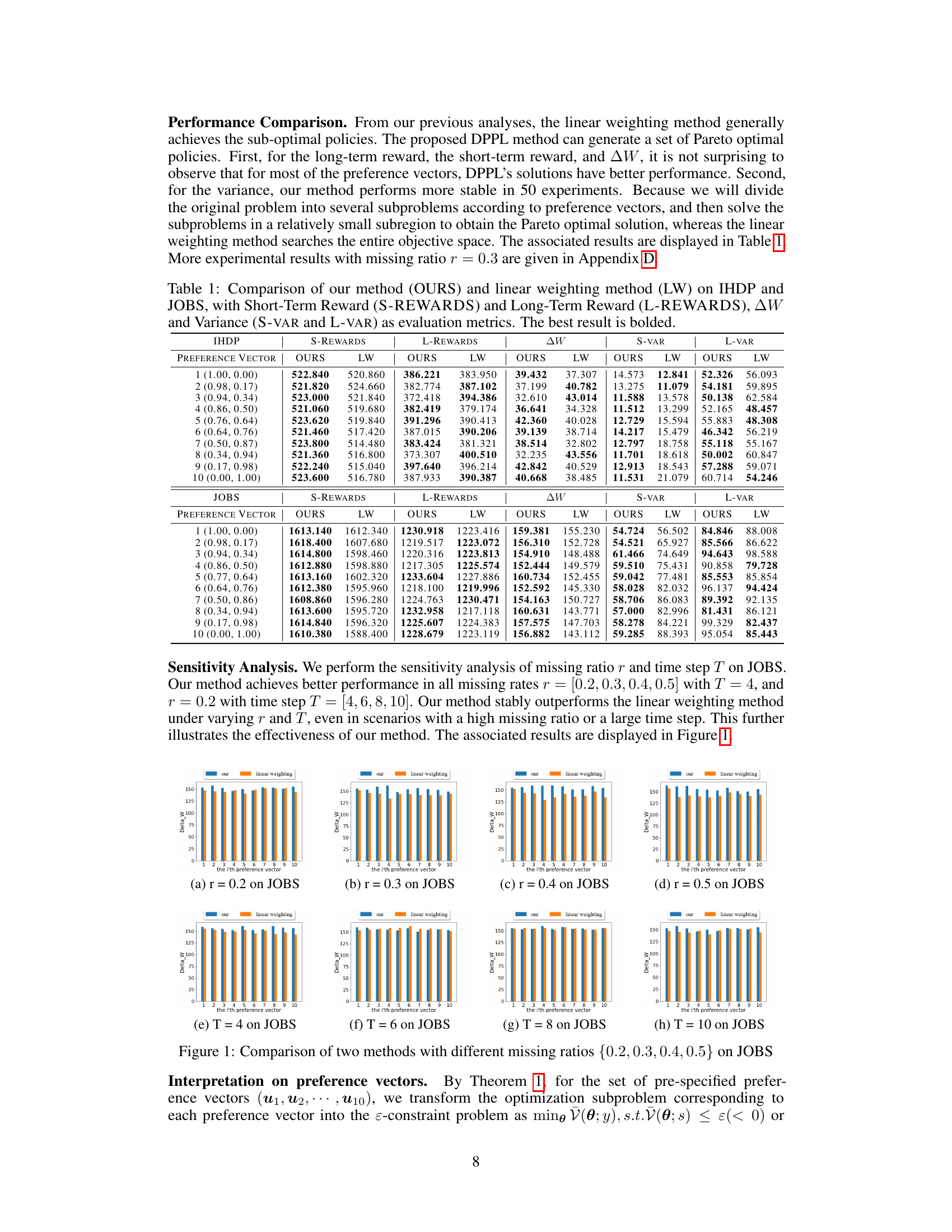

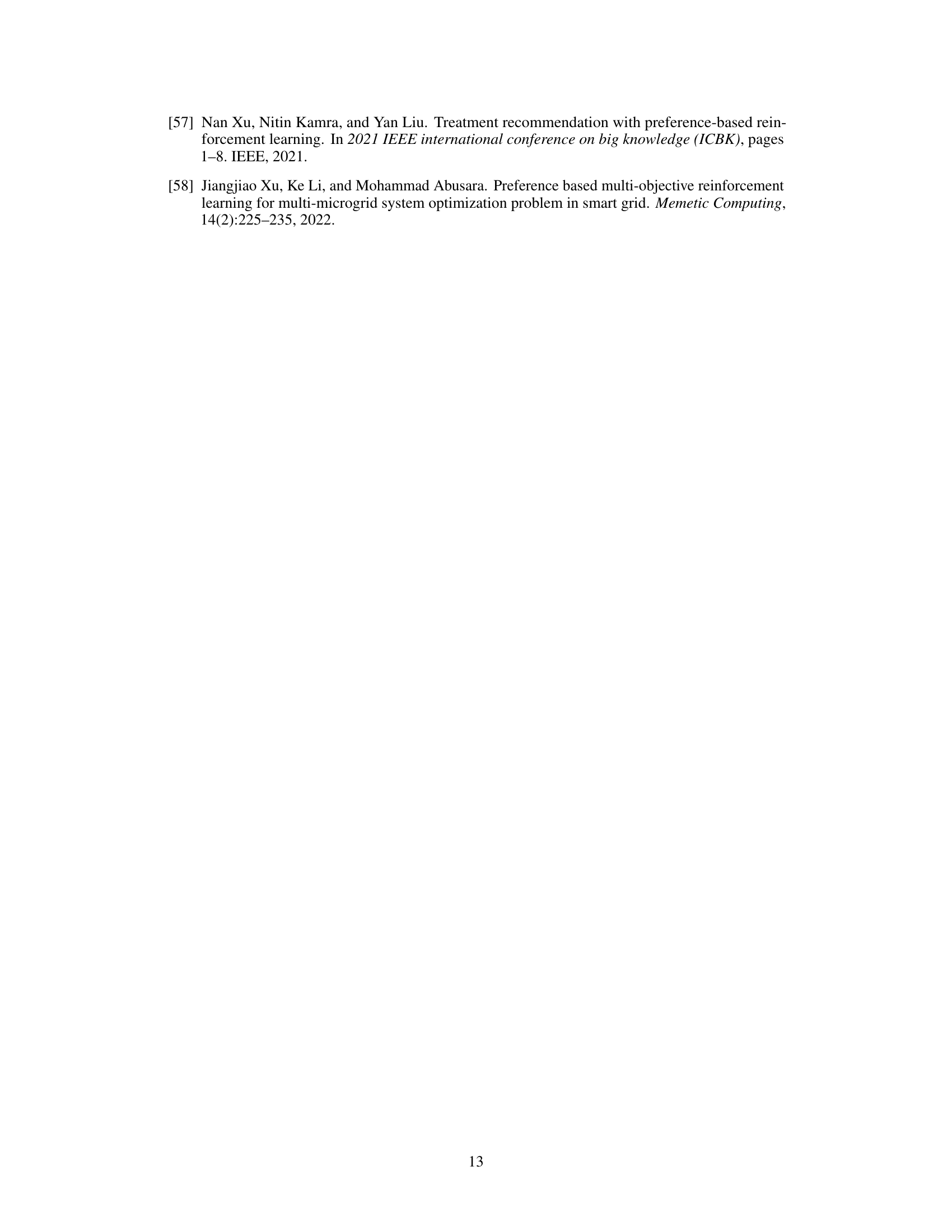

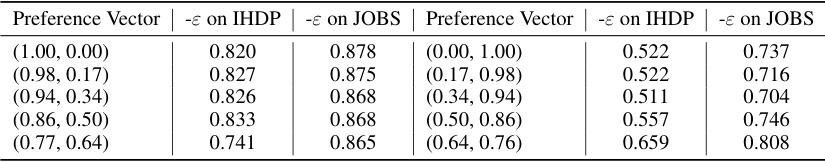

This table presents the minimum acceptable short-term reward (-ɛ) for different preference vectors, calculated using Theorem 1. The values are obtained from the IHDP and JOBS datasets, with a time step of 4 and a missing rate of 0.2. The table shows how the minimum acceptable short-term reward changes based on the preference given to long-term versus short-term rewards in the preference vector.

This table compares the performance of the proposed decomposition-based policy learning (DPPL) method and the linear weighting method on two benchmark datasets (IHDP and JOBS). For each method and dataset, it shows the short-term reward, long-term reward, the overall balanced reward (AW), and the variance of the short-term and long-term rewards across multiple runs. The best performance for each metric is highlighted in bold, demonstrating the superiority of the DPPL approach.

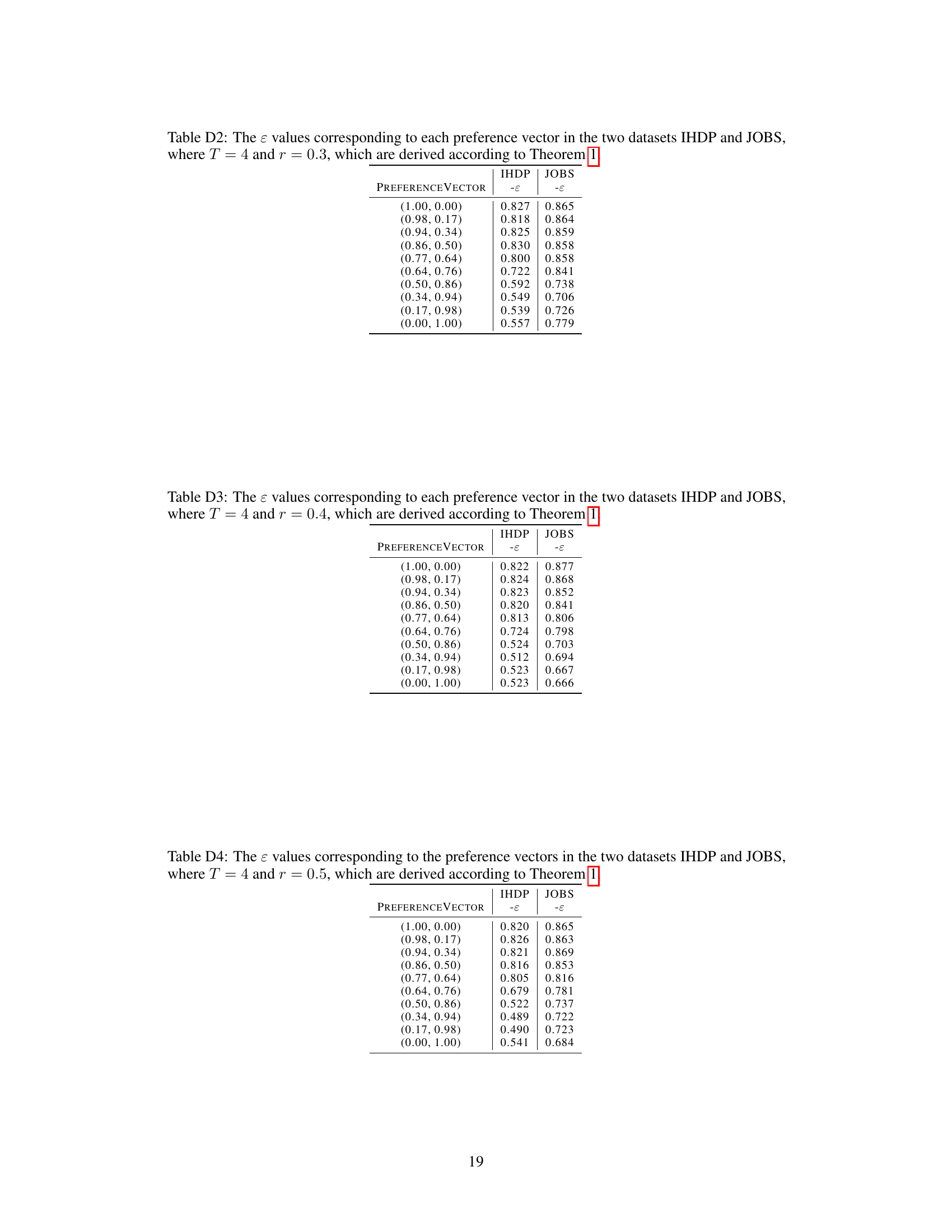

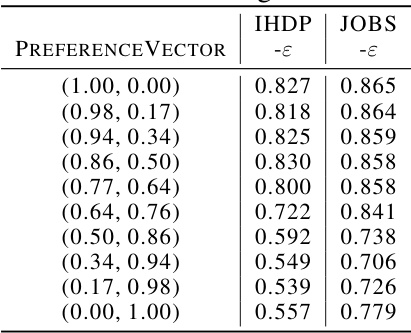

This table shows the minimum acceptable short-term reward (ε) for different preference vectors, calculated using Theorem 1. The table displays the results for both the IHDP and JOBS datasets under the condition of T=4 and r=0.3. Each row represents a specific preference vector, and the corresponding ε values for IHDP and JOBS are listed in separate columns.

This table shows the minimum acceptable value (ε) of the short-term reward for each preference vector, while maximizing the long-term reward. These values are calculated based on Theorem 1 in the paper, with a time step (T) of 4 and a missing ratio (r) of 0.3. The table helps decision-makers select preference vectors based on their acceptable short-term reward thresholds.

This table shows the minimum acceptable level of short-term reward (ε) for different preference vectors, considering the trade-off between short-term and long-term rewards. The values are calculated based on Theorem 1, with a missing ratio (r) of 0.3 and a time step (T) of 4. It helps to understand how the preference for long-term versus short-term rewards affects the acceptable minimum short-term reward.

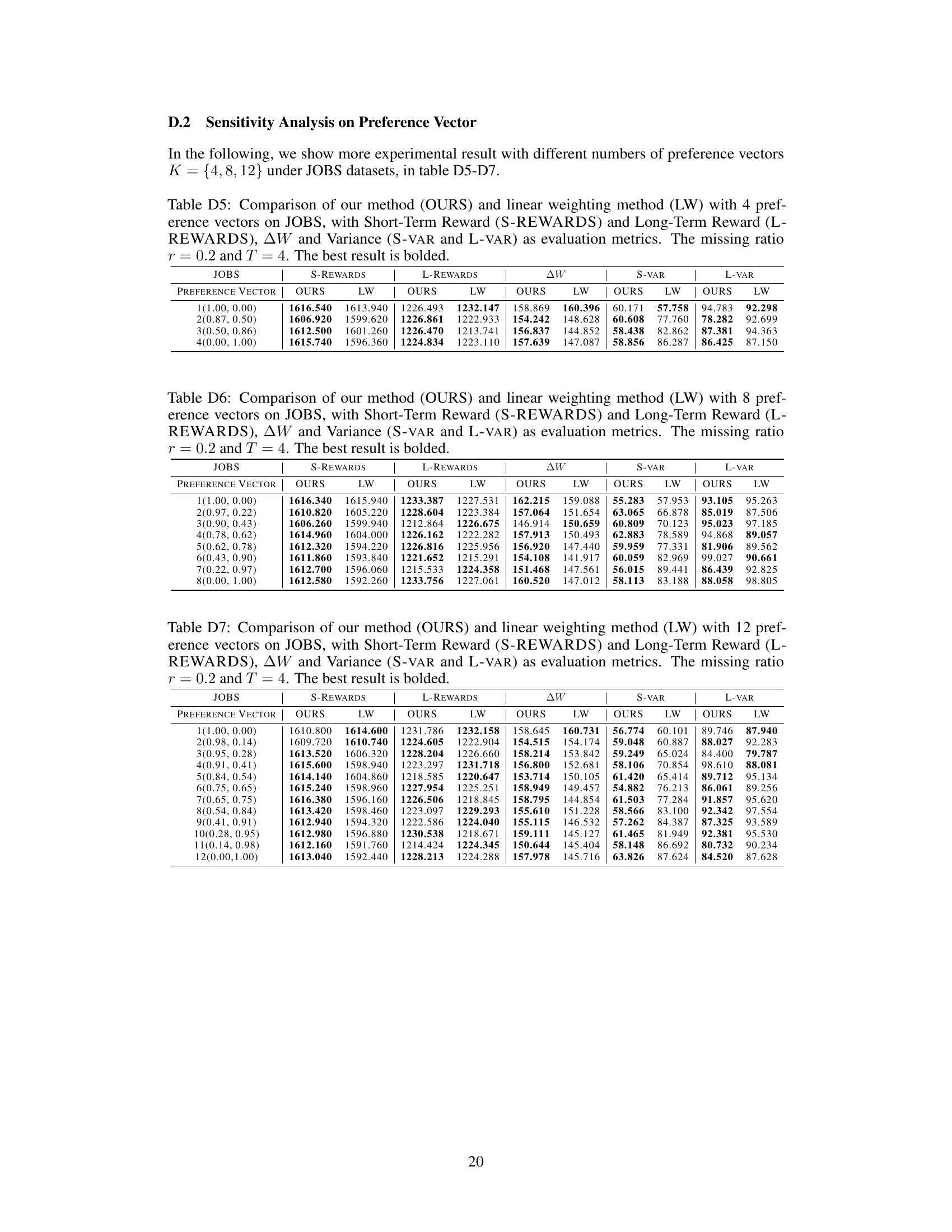

This table presents a comparison of the proposed Decomposition-based Policy Learning (DPPL) method and the Linear Weighting method for balancing short-term and long-term rewards. The comparison is made using two datasets (IHDP and JOBS) across multiple evaluation metrics. The metrics include short-term rewards, long-term rewards, a welfare change metric (AW), and the variance of both short and long-term rewards. The best performing method for each metric in each dataset is highlighted in bold.

This table compares the performance of the proposed Decomposition-based Policy Learning (DPPL) method and the traditional linear weighting method on two benchmark datasets (IHDP and JOBS) using several metrics including short-term rewards, long-term rewards, the combined welfare change (AW), and the variance of short-term and long-term rewards. The best performance for each metric is highlighted in bold. The table demonstrates the DPPL method’s superior performance and stability across various preference vectors.

This table compares the performance of the proposed Decomposition-based Policy Learning (DPPL) method and the traditional linear weighting method on two benchmark datasets, IHDP and JOBS. The comparison is based on several metrics: short-term rewards, long-term rewards, a combined welfare change (AW), and the variance of both short-term and long-term rewards. The best result for each metric is highlighted in bold, illustrating DPPL’s superiority in most cases.

Full paper#