↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current membership inference attacks (MIAs) often require numerous queries to a model, making them impractical. Existing label-only MIAs, which only utilize model predictions, further struggle with low accuracy. This paper addresses these issues by focusing on enhancing the accuracy of label-only MIAs.

The paper proposes OSLO, a novel one-shot label-only MIA. OSLO leverages transfer-based black-box adversarial attacks, exploiting the difference in robustness between member and non-member samples to training data. Through this, the method requires only one query to accurately infer membership. Evaluation shows that OSLO significantly outperforms previous methods across various datasets and model architectures, achieving higher precision and true positive rates under low false positive rates. The results demonstrate OSLO’s effectiveness and highlight the need for stronger defense mechanisms against this novel attack.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel one-shot label-only membership inference attack (OSLO), significantly advancing the state-of-the-art in privacy-preserving machine learning. Its high precision and efficiency, even with limited access, challenge current defense mechanisms and prompt researchers to develop more robust strategies. The work also opens new avenues for research into transfer-based black-box attacks and adaptive perturbation methods for MIA. This is relevant to ongoing trends in privacy-preserving AI and adversarial machine learning.

Visual Insights#

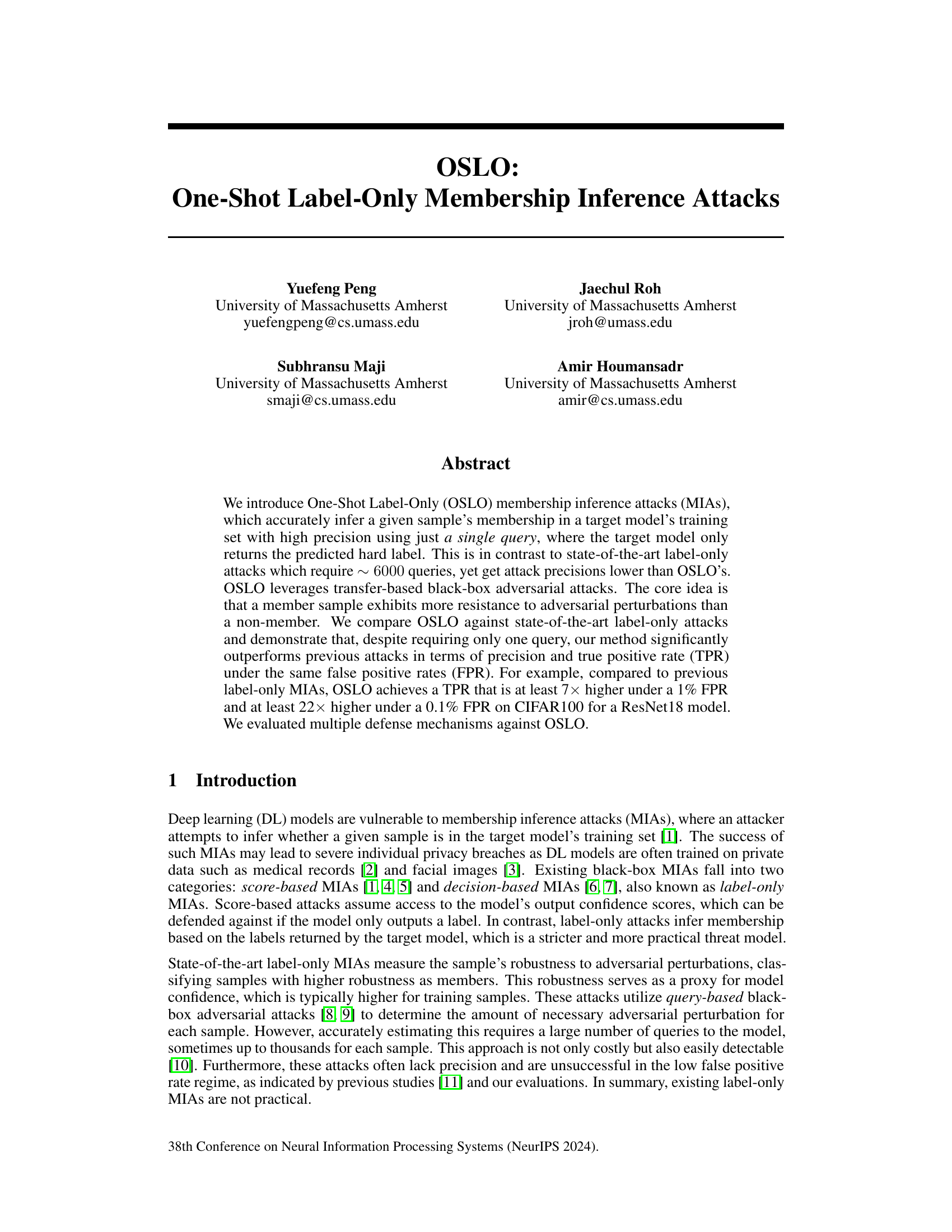

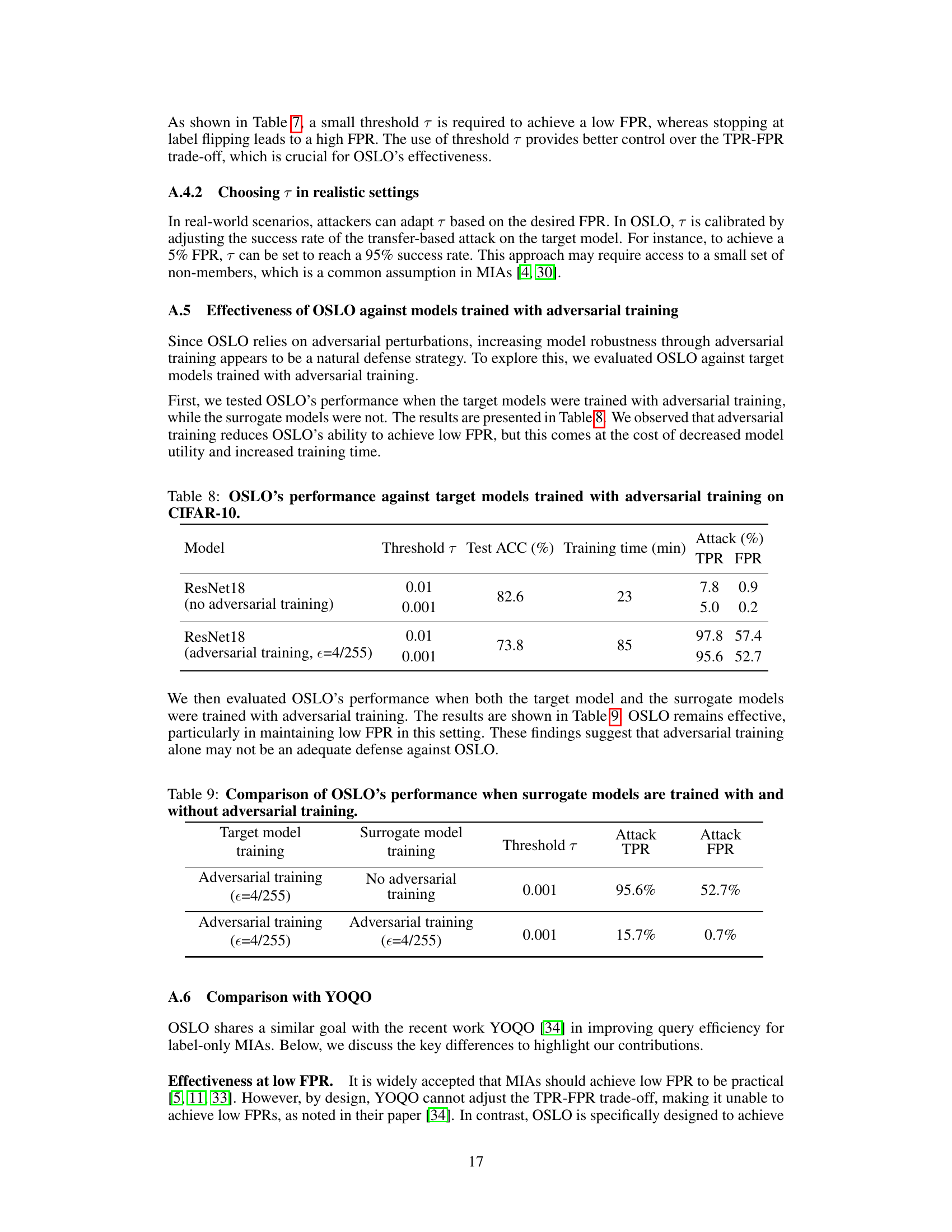

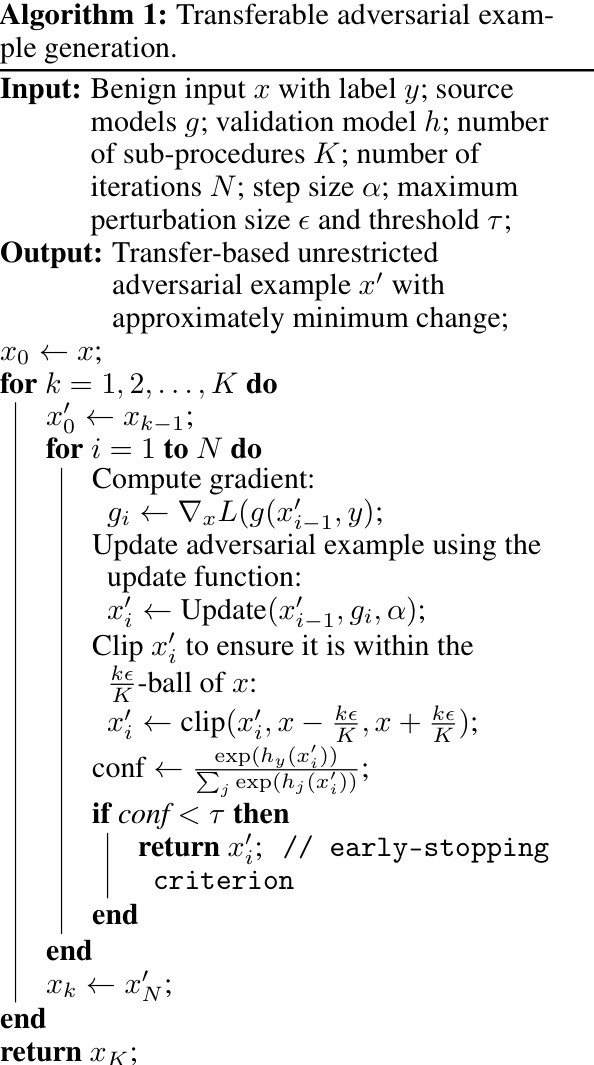

This figure compares the OSLO attack to existing state-of-the-art boundary attacks. The top half illustrates a boundary attack, showing multiple queries to the target model to iteratively adjust perturbations and determine membership. The bottom half shows the OSLO attack, which only requires a single query using transfer-based adversarial examples and a surrogate model to infer membership.

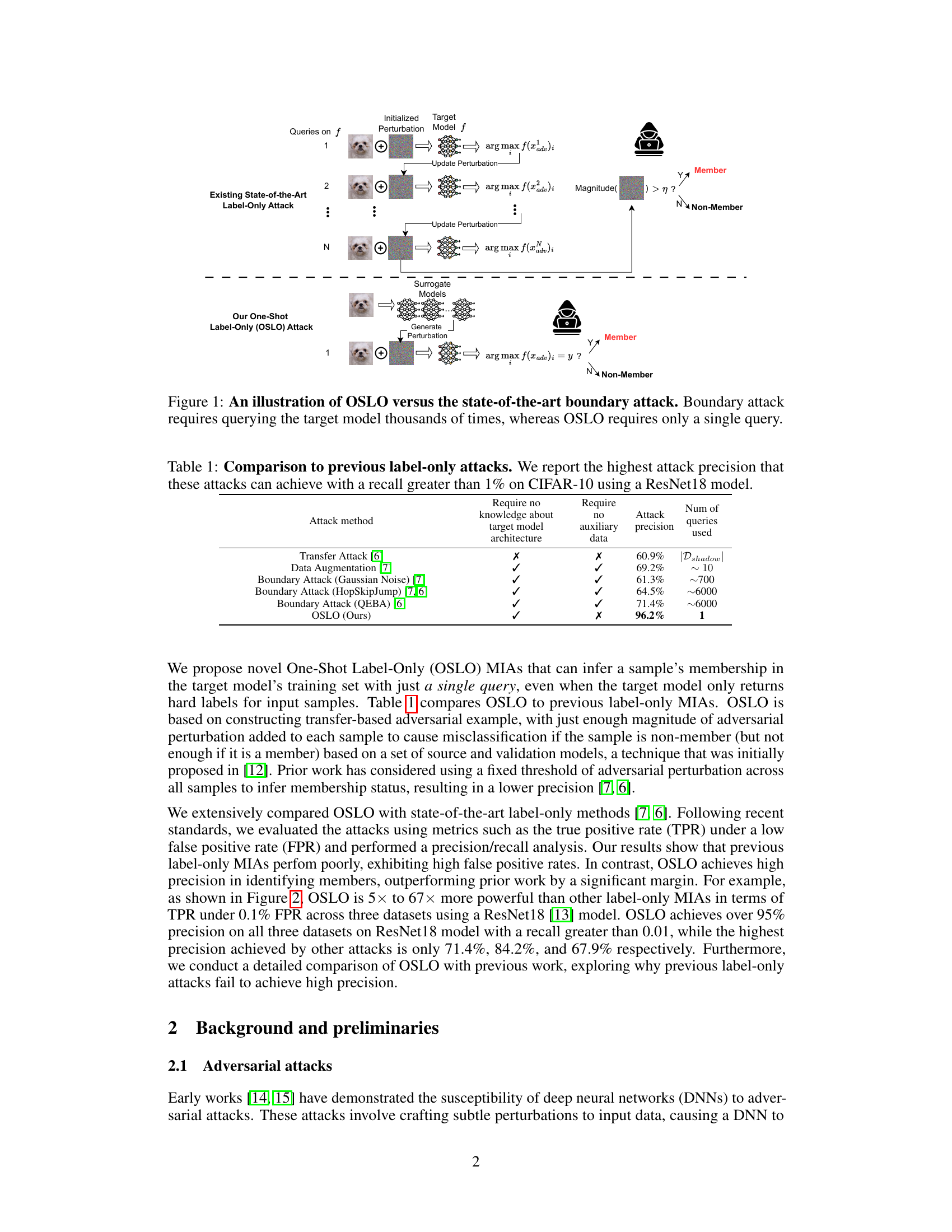

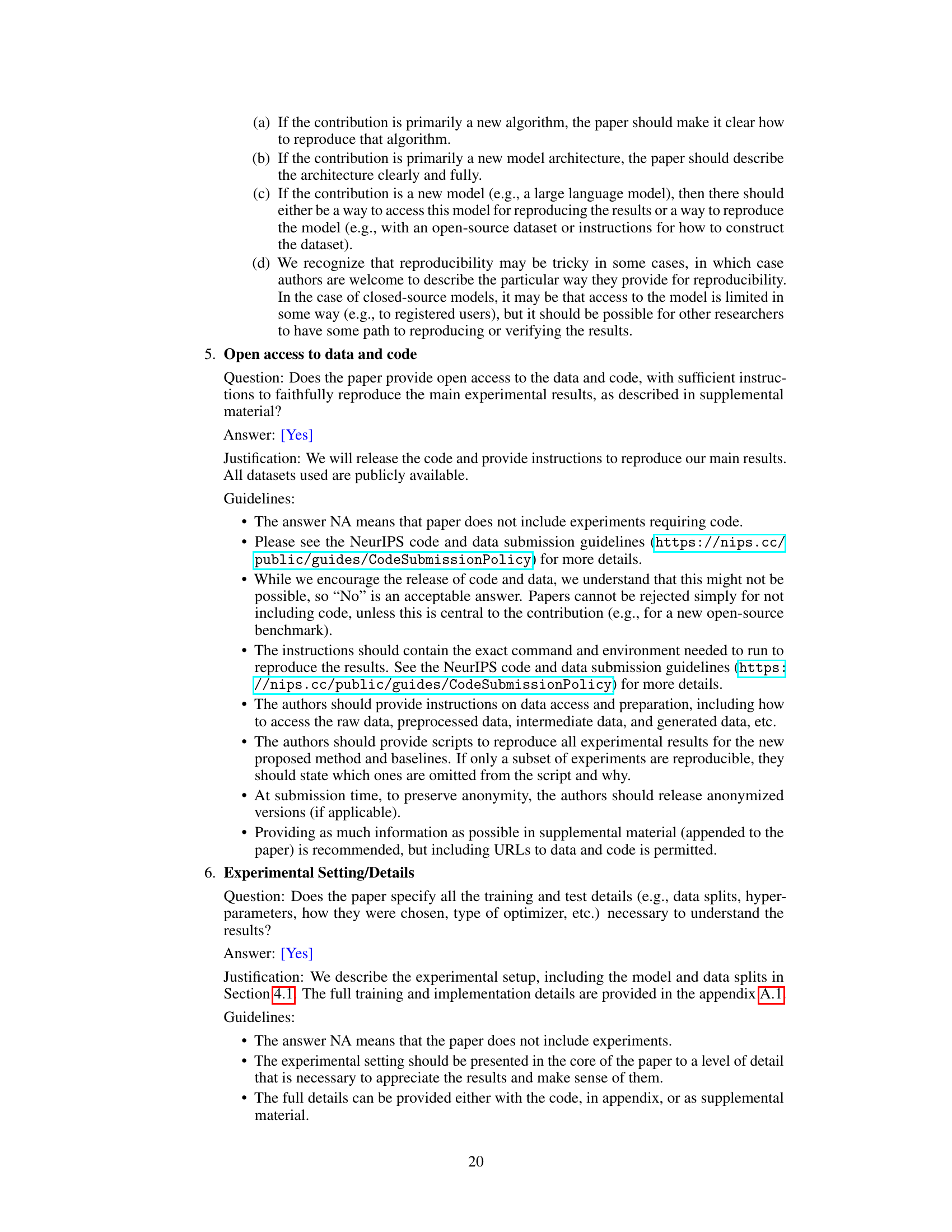

This table compares the proposed One-Shot Label-Only (OSLO) membership inference attack with existing state-of-the-art label-only attacks. It shows that OSLO significantly outperforms existing methods in terms of attack precision while requiring only a single query, in contrast to thousands of queries needed by other methods.

In-depth insights#

OSLO: One-Shot MIA#

The heading “OSLO: One-Shot MIA” suggests a novel membership inference attack (MIA) method. One-Shot highlights its efficiency, requiring only a single query to the target model, a significant improvement over existing label-only MIAs needing thousands. This implies high efficiency and reduced detection risk. The acronym “OSLO” likely represents a specific technique name; its effectiveness is further underscored by its ability to achieve higher precision and true positive rates (TPR) compared to previous methods, even under stringent low false positive rate (FPR) conditions. The core idea likely involves leveraging transfer-based black-box adversarial attacks, exploiting the difference in robustness to perturbations between member and non-member samples. This implies OSLO is a transfer-learning based approach, focusing on the magnitude of adversarial perturbation required to misclassify a sample. The single-query nature is a crucial advantage, suggesting significant improvements in the practicality and stealth of membership inference attacks.

Transfer-Based Attacks#

Transfer-based attacks represent a significant class of adversarial attacks against machine learning models. They leverage the transferability of adversarial examples, meaning that perturbations crafted for one model (the source model) often successfully fool other models (the target models), even if the target model’s architecture or training data differs. This black-box characteristic is crucial as it circumvents the need for the attacker to have access to the target model’s internal parameters or training data. However, the effectiveness of transfer-based attacks depends heavily on several factors, including the similarity between source and target models, and the robustness of the adversarial examples generated. Techniques to enhance transferability include incorporating momentum into the iterative attack process, increasing input diversity during the attack, and creating translation-invariant perturbations. While powerful, transfer-based attacks are not foolproof. Defense mechanisms such as adversarial training can significantly reduce the effectiveness of these attacks, highlighting the ongoing arms race between attackers and defenders in the realm of adversarial machine learning.

Adaptive Perturbation#

The concept of “Adaptive Perturbation” in the context of membership inference attacks (MIAs) signifies a paradigm shift from traditional methods. Instead of employing a uniform perturbation magnitude across all samples, adaptive perturbation strategies dynamically adjust the perturbation strength based on individual sample characteristics. This approach is crucial because member samples, residing within the model’s training set, inherently exhibit greater robustness to perturbations compared to non-member samples. By intelligently tailoring the perturbation magnitude, adaptive methods aim to achieve a higher precision in identifying members. This precision is paramount in MIAs, as false positives can severely undermine the attack’s credibility and practical value. Adaptive perturbation, therefore, represents a promising direction in enhancing MIA effectiveness, particularly within the constraints of label-only attacks, where access to model confidence scores is unavailable.

Precision-Recall Tradeoffs#

The concept of “Precision-Recall Tradeoffs” is central to evaluating the effectiveness of membership inference attacks (MIAs). High precision is crucial because a false positive (incorrectly identifying a non-member) significantly reduces the attack’s credibility. High recall is desirable as it means more true members are identified, but this comes at the cost of potentially increased false positives. The optimal balance hinges on the specific security goals. In a high-stakes scenario like protecting sensitive medical data, minimizing false positives (maximizing precision) is paramount even if it means lower recall. Conversely, when the consequences of missing a member are severe, prioritizing high recall might be justified. OSLO’s achievement is notable, as it demonstrably outperforms previous methods by substantially improving precision at a given recall, thus successfully navigating this tradeoff more effectively.

Defense Mechanisms#

The paper evaluates the robustness of its novel one-shot label-only membership inference attack (OSLO) against various defense mechanisms. While the specific defenses aren’t explicitly named as a heading, the evaluation highlights their effectiveness. The results indicate that existing defenses, such as those based on confidence alteration, are largely ineffective against OSLO. This underscores the unique nature of OSLO, which leverages transfer-based adversarial attacks to infer membership with a single query. The study also shows that adversarial training, while providing some level of protection, does not completely mitigate the threat posed by OSLO. Further research is needed to explore and develop more robust defense strategies that can effectively counter the power and efficiency of this novel one-shot membership inference attack. The study highlights the need for stronger defenses, particularly those that address the underlying vulnerabilities exploited by transfer-based adversarial attacks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

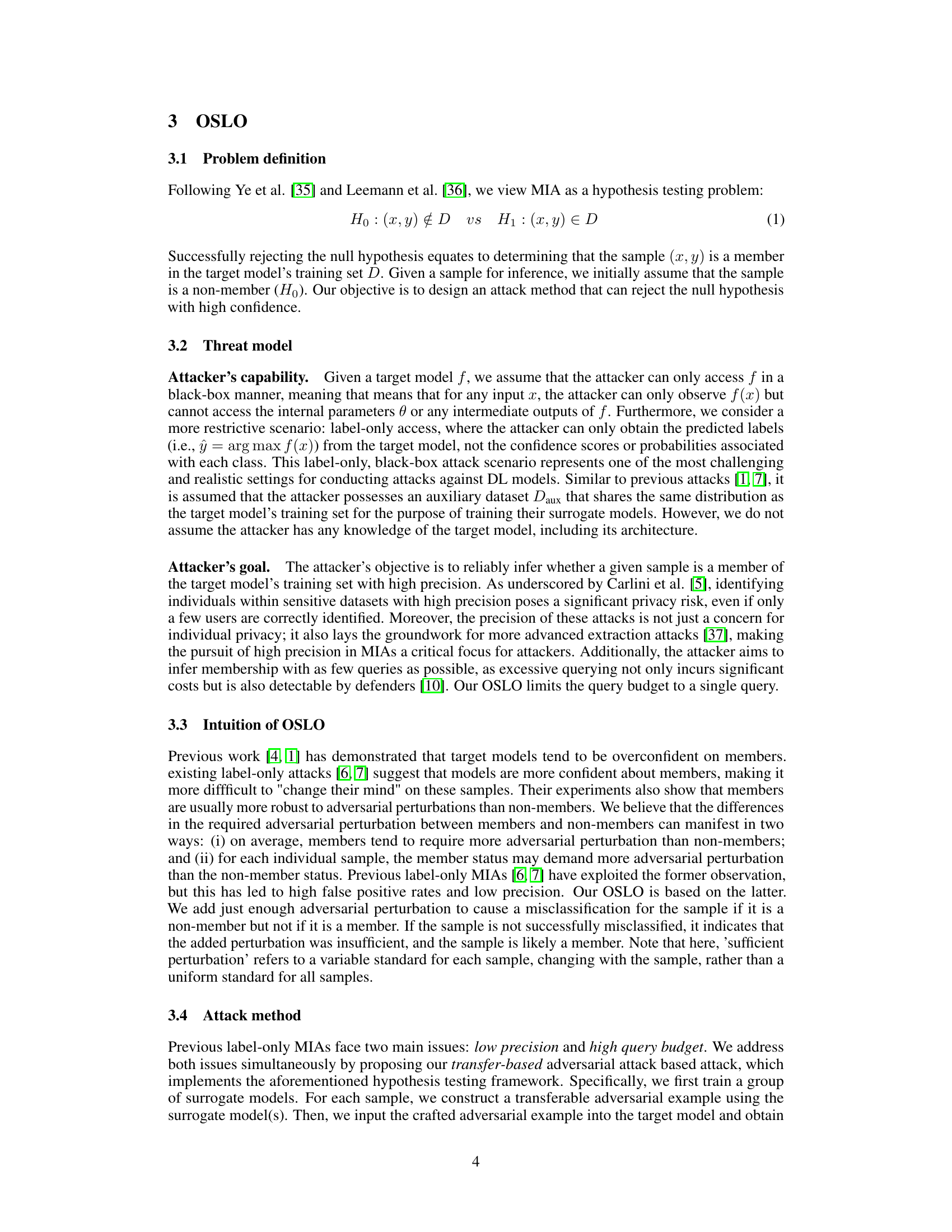

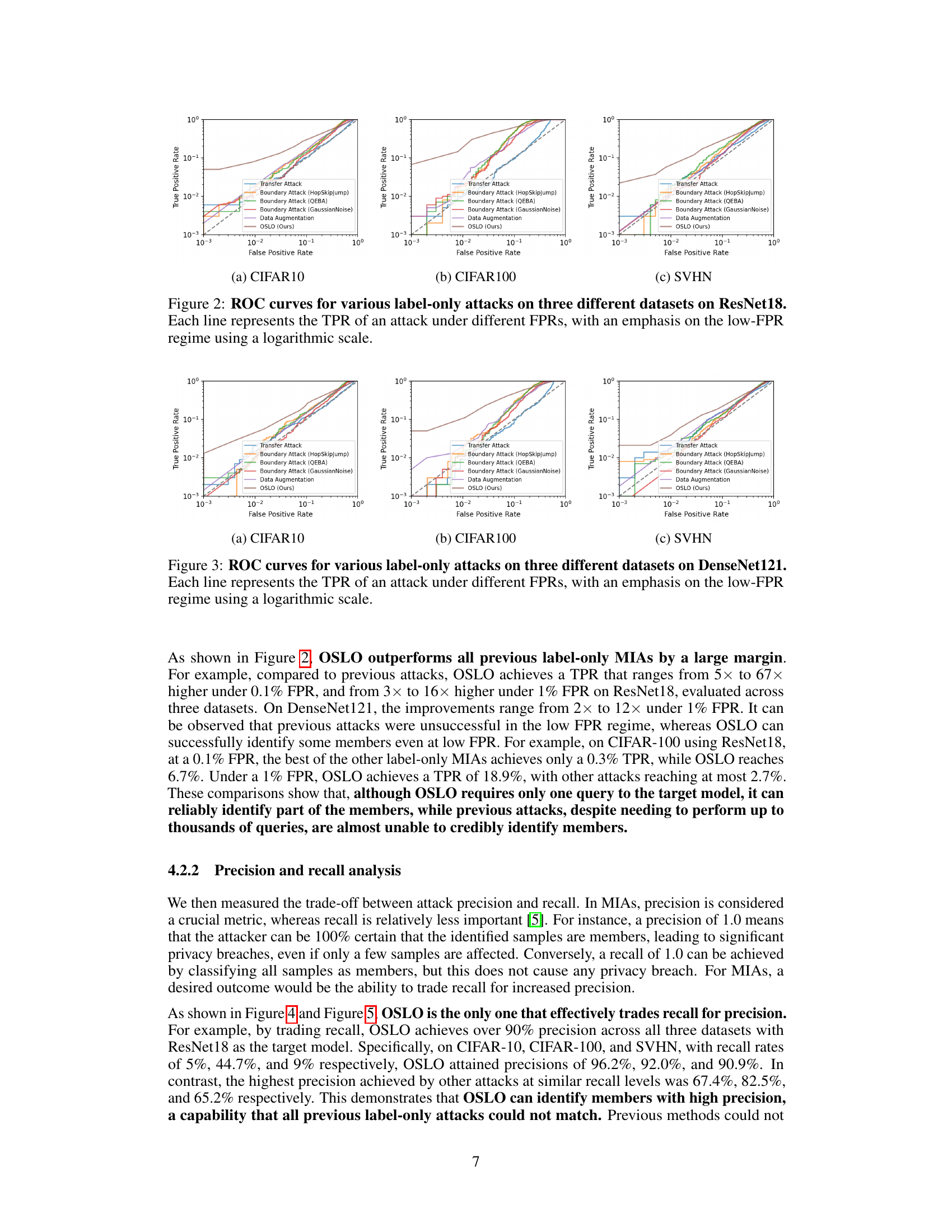

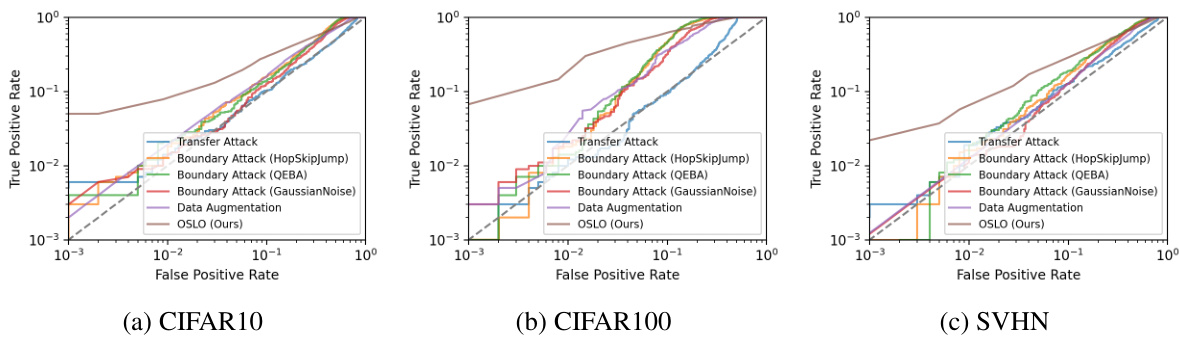

This figure shows the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for several label-only membership inference attacks on three datasets (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and SVHN) using a ResNet18 model. The x-axis represents the False Positive Rate (FPR), and the y-axis represents the True Positive Rate (TPR). Each line represents a different attack method, with OSLO (the proposed method) shown for comparison. The logarithmic scale emphasizes the performance at low FPR values, highlighting OSLO’s superiority in identifying members with high accuracy while maintaining a low false positive rate.

This figure displays the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for several label-only membership inference attacks on three datasets (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and SVHN) using a ResNet18 model. The x-axis represents the False Positive Rate (FPR), and the y-axis represents the True Positive Rate (TPR). Each line corresponds to a different attack method. The logarithmic scale emphasizes performance at low FPRs, which is crucial for effective attacks.

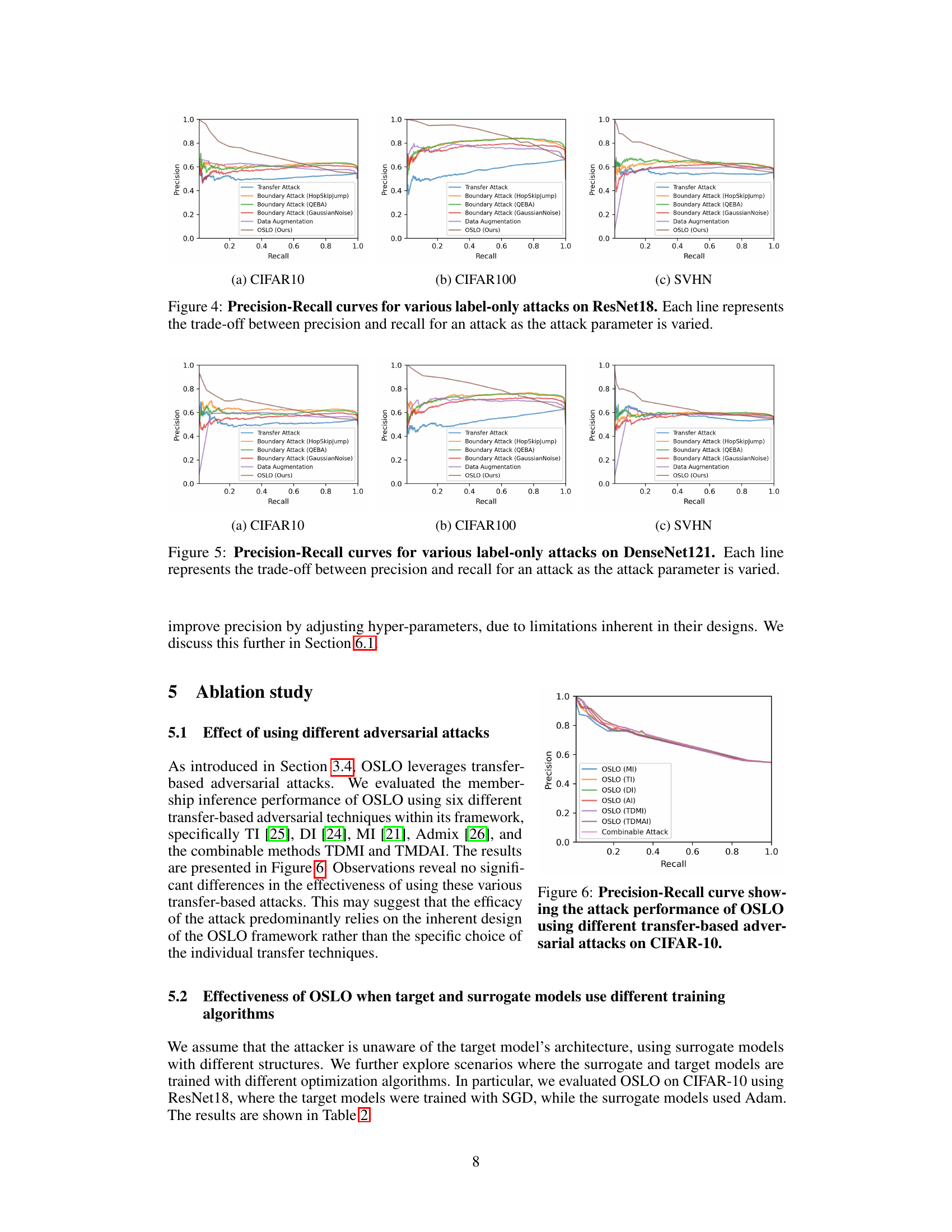

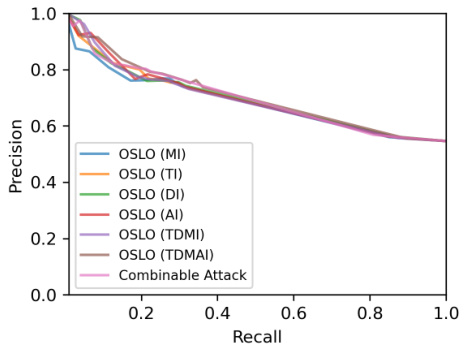

This figure shows the precision-recall curves for six different label-only membership inference attacks on a ResNet18 model. The attacks are: Transfer Attack, Boundary Attack (HopSkipJump), Boundary Attack (QEBA), Boundary Attack (Gaussian Noise), Data Augmentation, and OSLO. Each curve represents how the attack’s precision and recall change as the attack’s parameter is adjusted. OSLO demonstrates a significantly improved ability to trade-off recall for high precision compared to the other attacks.

This figure compares the performance of OSLO against other state-of-the-art label-only membership inference attacks. It shows precision and recall for each method across various settings. The key takeaway is that OSLO demonstrates a superior ability to achieve high precision while trading off some recall, unlike previous approaches which struggle to achieve high precision, especially at low recall values.

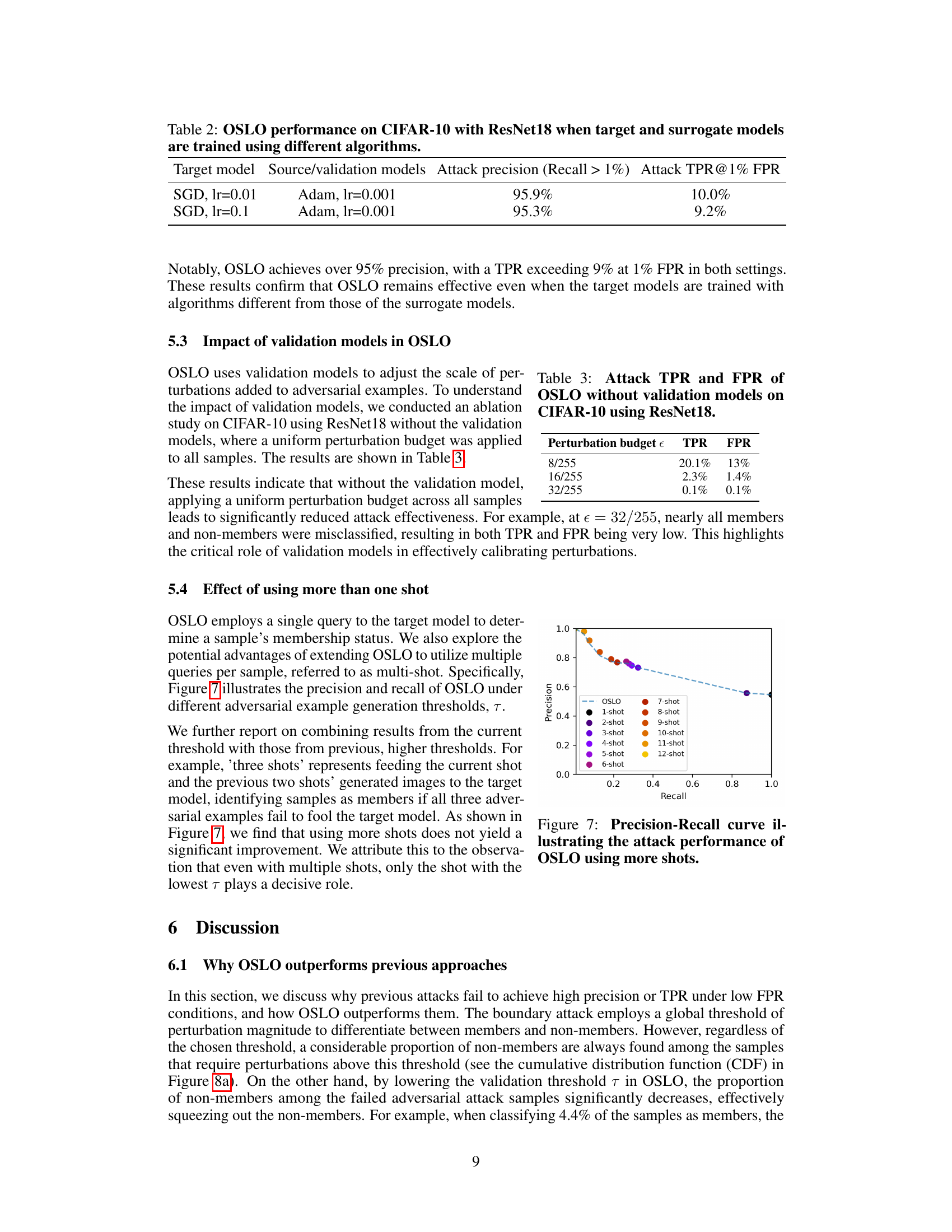

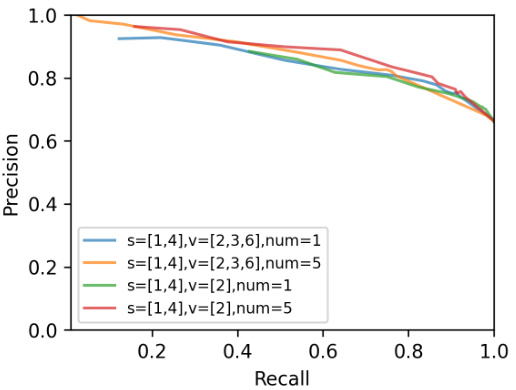

This figure shows the precision-recall curve for OSLO using six different transfer-based adversarial attacks on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The attacks are Momentum Iterative Fast Gradient Sign Method (MI-FGSM), Translation-Invariant Fast Gradient Sign Method (TI-FGSM), Diverse Inputs Iterative Fast Gradient Sign Method (DI2-FGSM), Admix, and the combinable methods TDMI and TMDAI. The figure illustrates the trade-off between precision (the proportion of correctly identified members among all positively predicted members) and recall (the proportion of correctly identified members among all actual members) for each attack. The results suggest that the choice of specific transfer-based attack has minimal impact on the overall performance of OSLO.

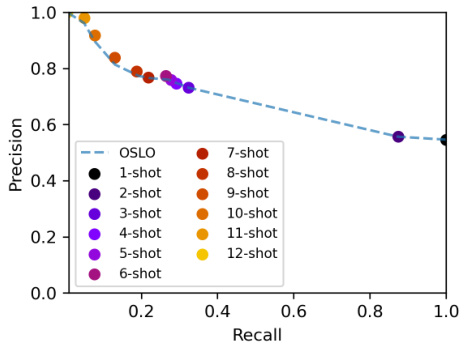

This figure shows the precision-recall curve for the OSLO attack using different numbers of queries (shots). It demonstrates that while OSLO’s performance increases with more shots, the gains diminish beyond a certain point. The one-shot approach remains remarkably effective, highlighting the efficiency of OSLO in achieving high precision and recall even with a single query.

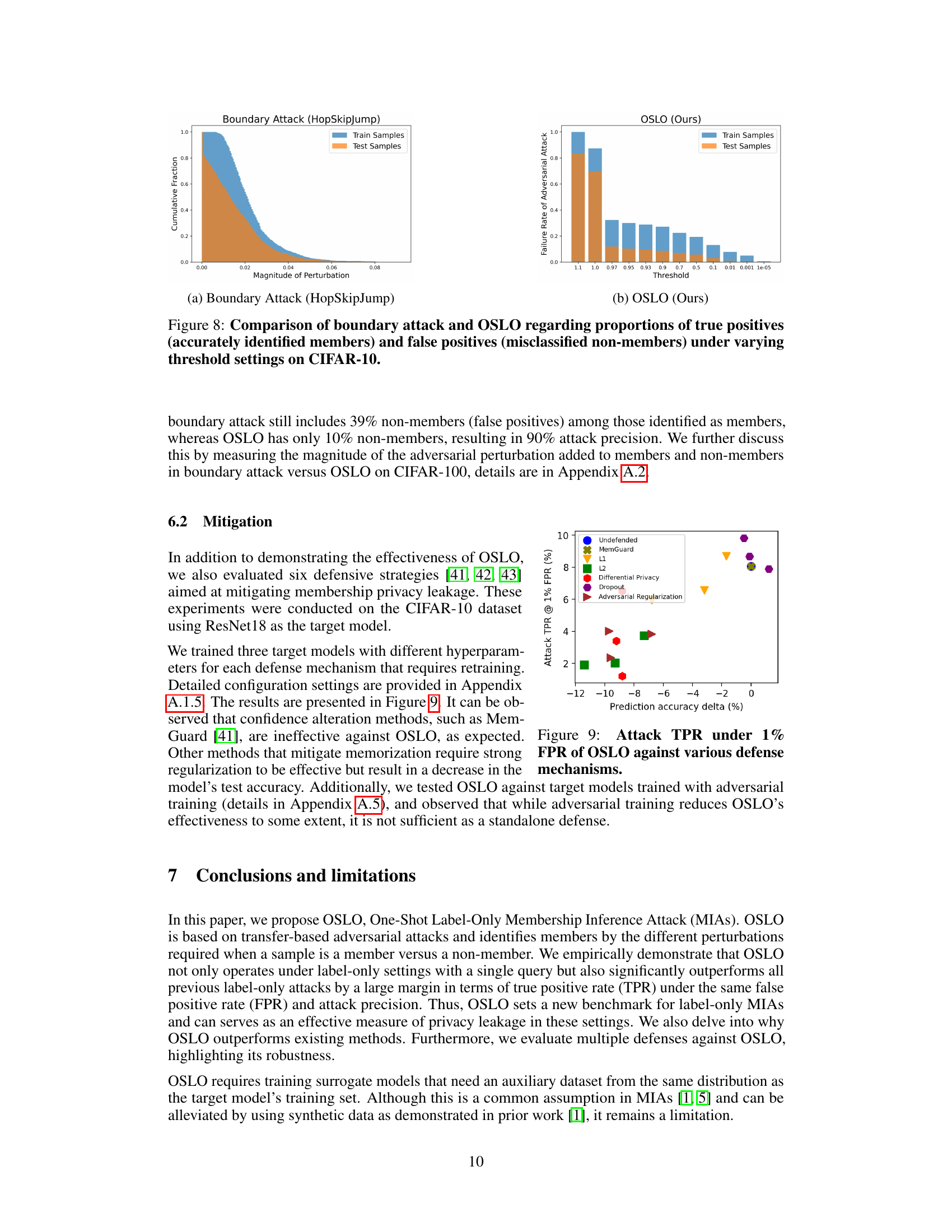

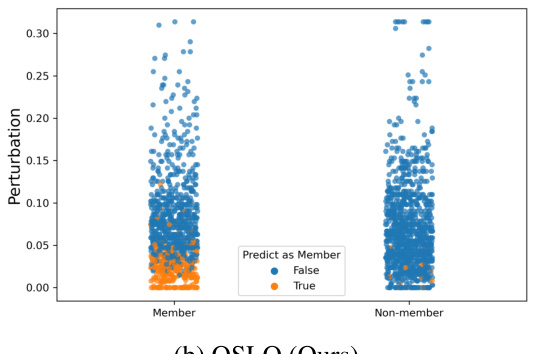

This figure compares the performance of the Boundary Attack (HopSkipJump) and OSLO methods in terms of their ability to correctly identify members and non-members of a training dataset. It shows the cumulative distribution of the magnitude of adversarial perturbation needed to misclassify samples. The key observation is that OSLO has a much sharper separation between the distributions of members and non-members, leading to higher precision in identifying members even at low false positive rates.

This figure compares the performance of the Boundary Attack and OSLO methods in terms of identifying members (true positives) and non-members (false positives) in a dataset. It shows the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the magnitude of adversarial perturbations required to misclassify samples for each method. The Boundary Attack uses a global threshold for perturbation, while OSLO adapts the threshold per sample. The plots illustrate that OSLO has a much lower rate of false positives compared to the Boundary Attack for similar true positive rates.

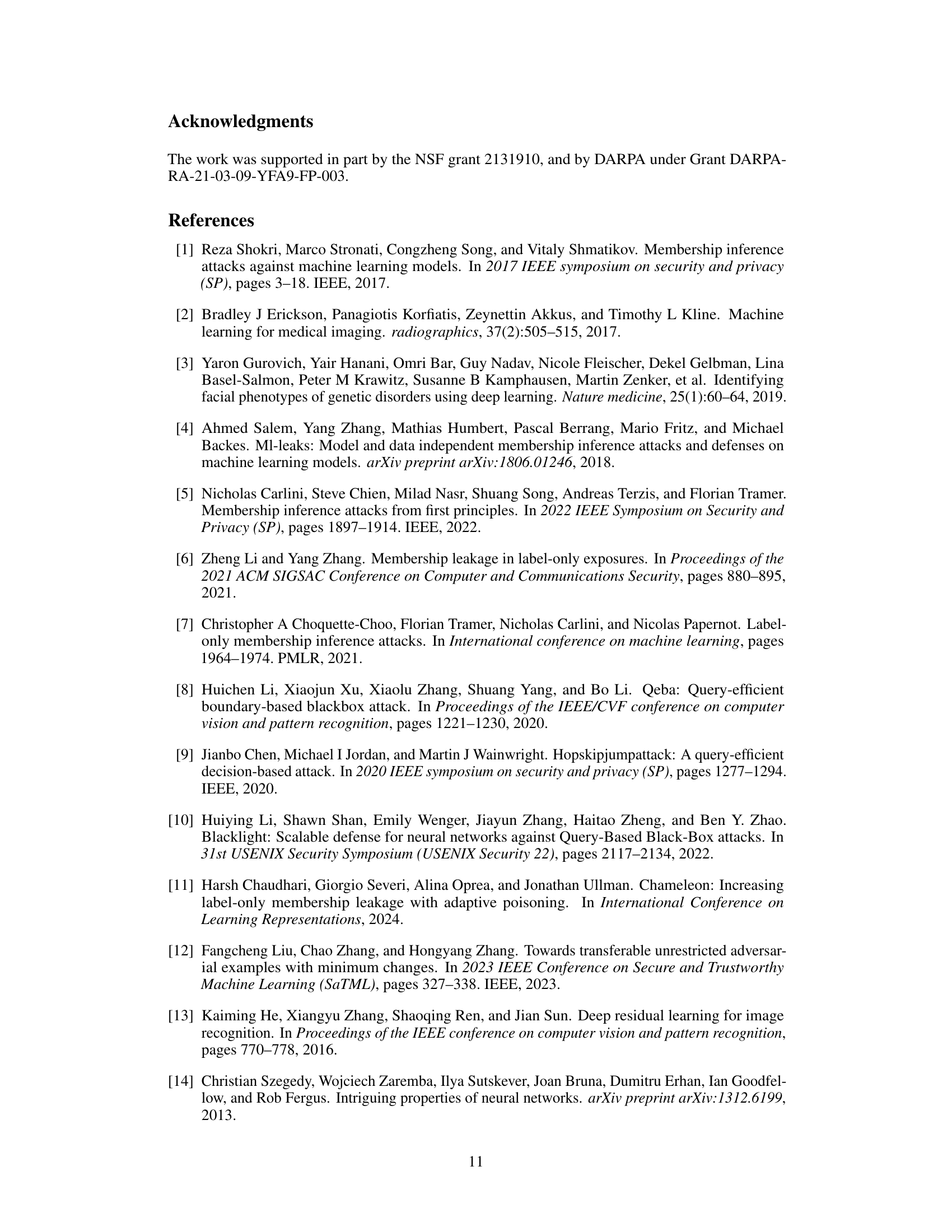

This figure displays the performance of OSLO, a One-Shot Label-Only Membership Inference Attack, against various defense mechanisms. The x-axis represents the change in prediction accuracy (delta) caused by the defense mechanism, while the y-axis represents the true positive rate (TPR) of OSLO at a 1% false positive rate (FPR). Each point on the graph corresponds to a different defense mechanism, showing how effectively each defense mitigates the attack’s success rate. The figure helps to determine which defense mechanisms are more robust against this specific type of attack.

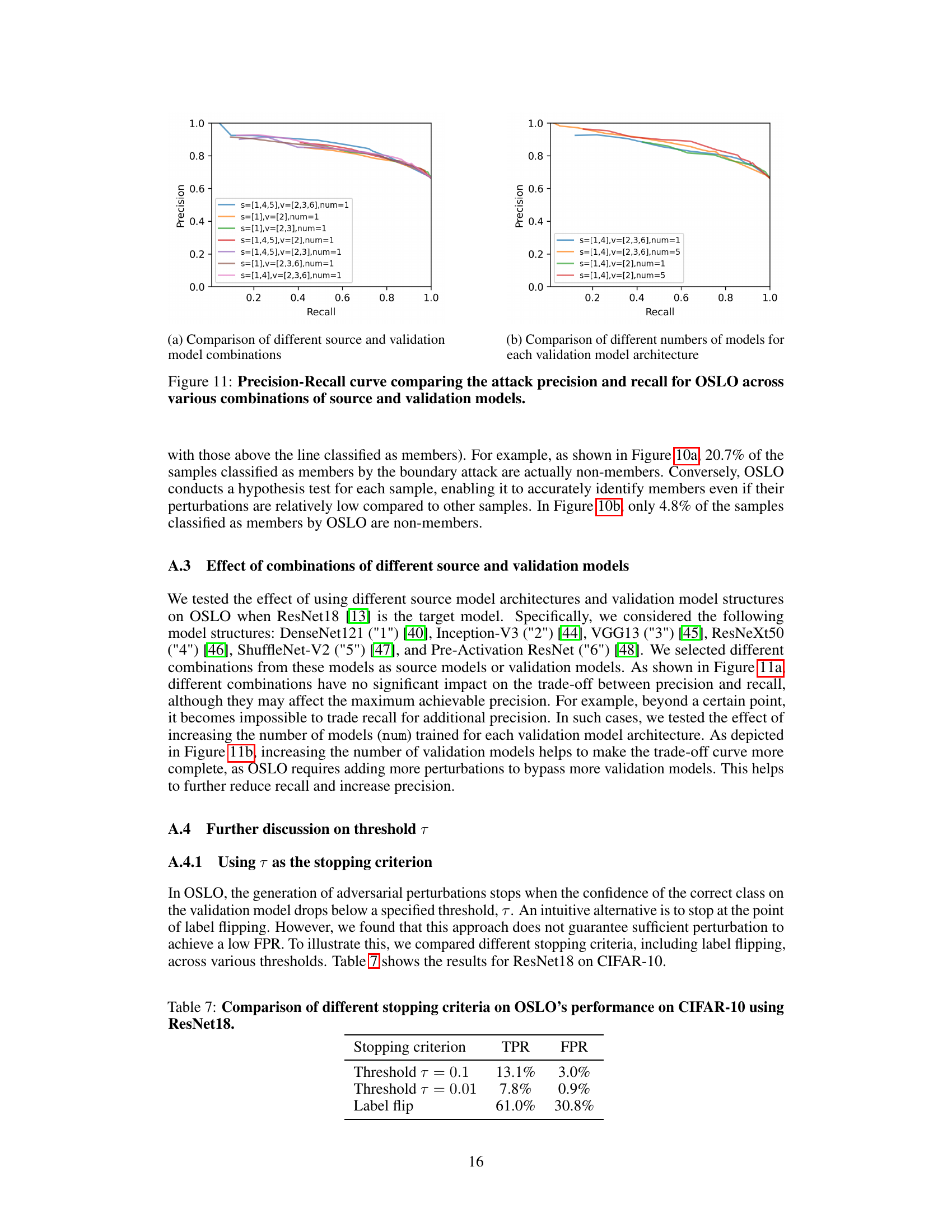

This figure compares the magnitude of adversarial perturbations used by the boundary attack and OSLO methods on the CIFAR-100 dataset. Both methods were tuned to classify 15.8% of samples as members. The plot shows that OSLO achieves a much higher precision (95.2%) compared to the boundary attack (79.3%) because it uses a more precise method for determining the required perturbation for each sample, rather than applying a uniform threshold. This highlights OSLO’s improved ability to distinguish members from non-members, even when a similar number of samples are classified as members.

This figure compares the magnitude of adversarial perturbations used by the boundary attack and OSLO methods on CIFAR-100. The parameters of both attacks were tuned to achieve a similar recall (15.8% of samples correctly identified as members). The plot reveals that OSLO achieves a much higher precision (95.2%) compared to the boundary attack (79.3%), highlighting OSLO’s superior ability to distinguish between members and non-members based on perturbation magnitude.

This figure compares the precision and recall of the OSLO attack under different configurations of source and validation models. The x-axis represents recall (the proportion of actual members correctly identified), and the y-axis represents precision (the proportion of identified members that are actually members). Each line represents a different combination of source and validation model architectures and the number of models used for each architecture. The results demonstrate how different combinations of models affect the trade-off between precision and recall in the OSLO attack.

This figure compares different configurations of OSLO’s source and validation models. It shows the precision-recall curves for OSLO when using different numbers and types of source models (indicated by ’s’) and validation models (indicated by ‘v’). ’num’ represents the number of models used for each architecture. The results illustrate how these choices impact OSLO’s ability to accurately identify members while controlling the rate of false positives. Variations in precision and recall across different model combinations highlight the sensitivity of OSLO’s performance to its model setup.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of the proposed One-Shot Label-Only (OSLO) membership inference attack against existing state-of-the-art label-only attacks. It shows that OSLO significantly outperforms previous methods in terms of attack precision, even though it requires only a single query to the target model, while others need thousands of queries. The table highlights the number of queries each attack requires and the highest attack precision achieved with a recall above 1% on the CIFAR-10 dataset using a ResNet18 model.

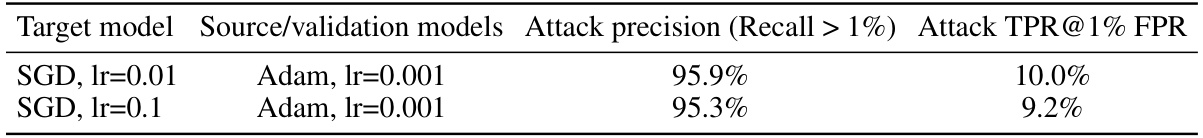

This table presents the results of the OSLO attack on the CIFAR-10 dataset using a ResNet18 model. The experiment investigates the impact of training the target and surrogate models with different optimization algorithms (SGD vs. Adam) on the attack’s performance. It reports the attack precision (when recall is greater than 1%) and the true positive rate (TPR) at a 1% false positive rate (FPR). The results show that OSLO maintains high precision and TPR even when the target and surrogate models are trained with different optimizers.

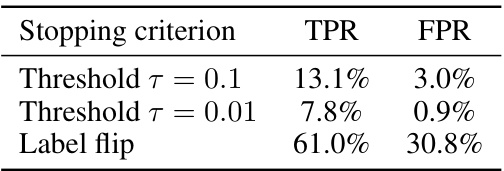

This table presents the results of the OSLO attack on CIFAR-10 using a ResNet18 model without the use of validation models. It shows the true positive rate (TPR) and false positive rate (FPR) achieved by the attack at different perturbation budgets (epsilon). The absence of validation models causes significantly reduced attack effectiveness as the TPR and FPR are very low at all perturbation budgets.

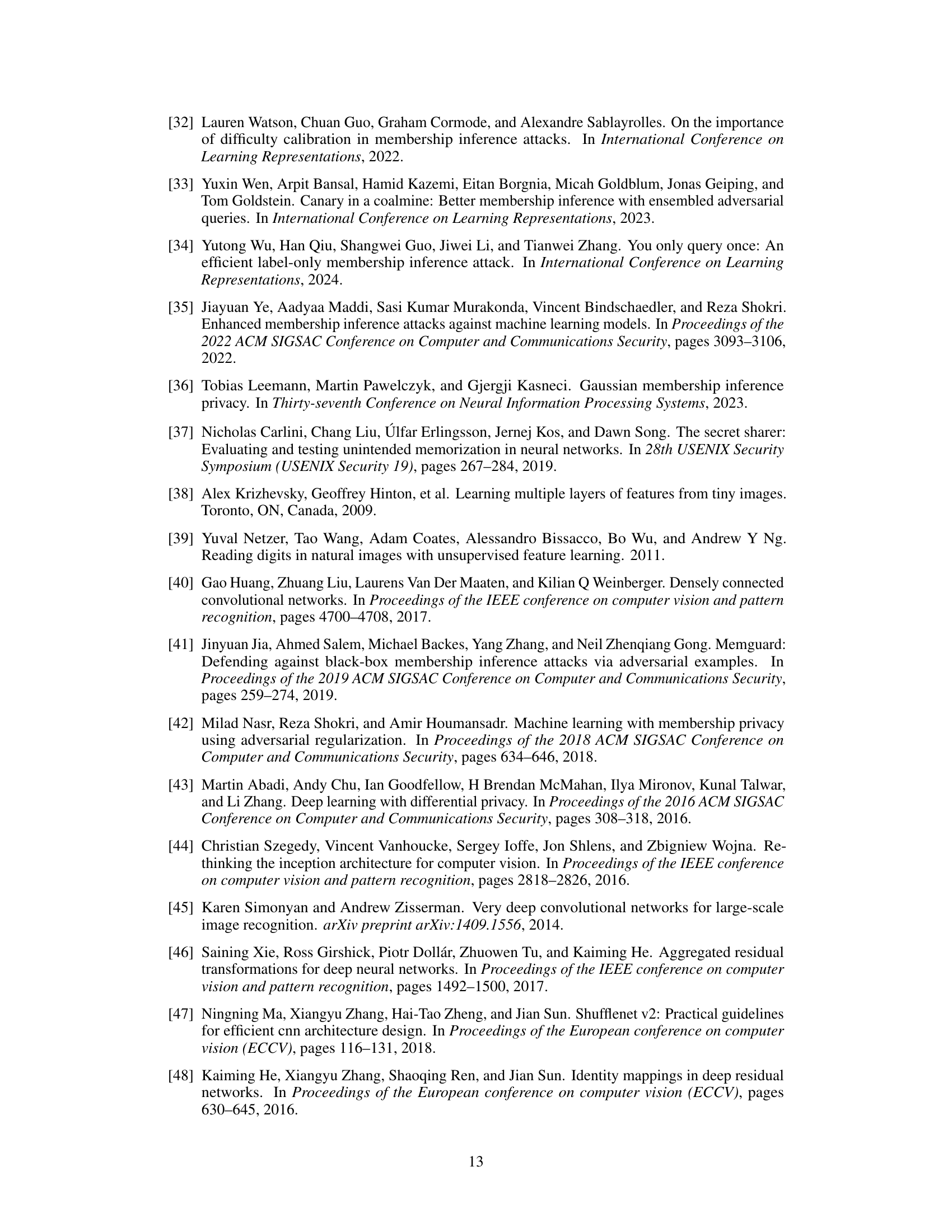

This table details the data split used for training the target model and the source/validation models for the experiments. For CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100, half of the training set (25,000 samples) was used for each. For SVHN, two disjoint subsets of 5,000 samples were created. The table shows the number of samples used for training the target model, the number of samples used for training the source and validation models, and the number of samples used for evaluation (1,000 members and 1,000 non-members for each dataset).

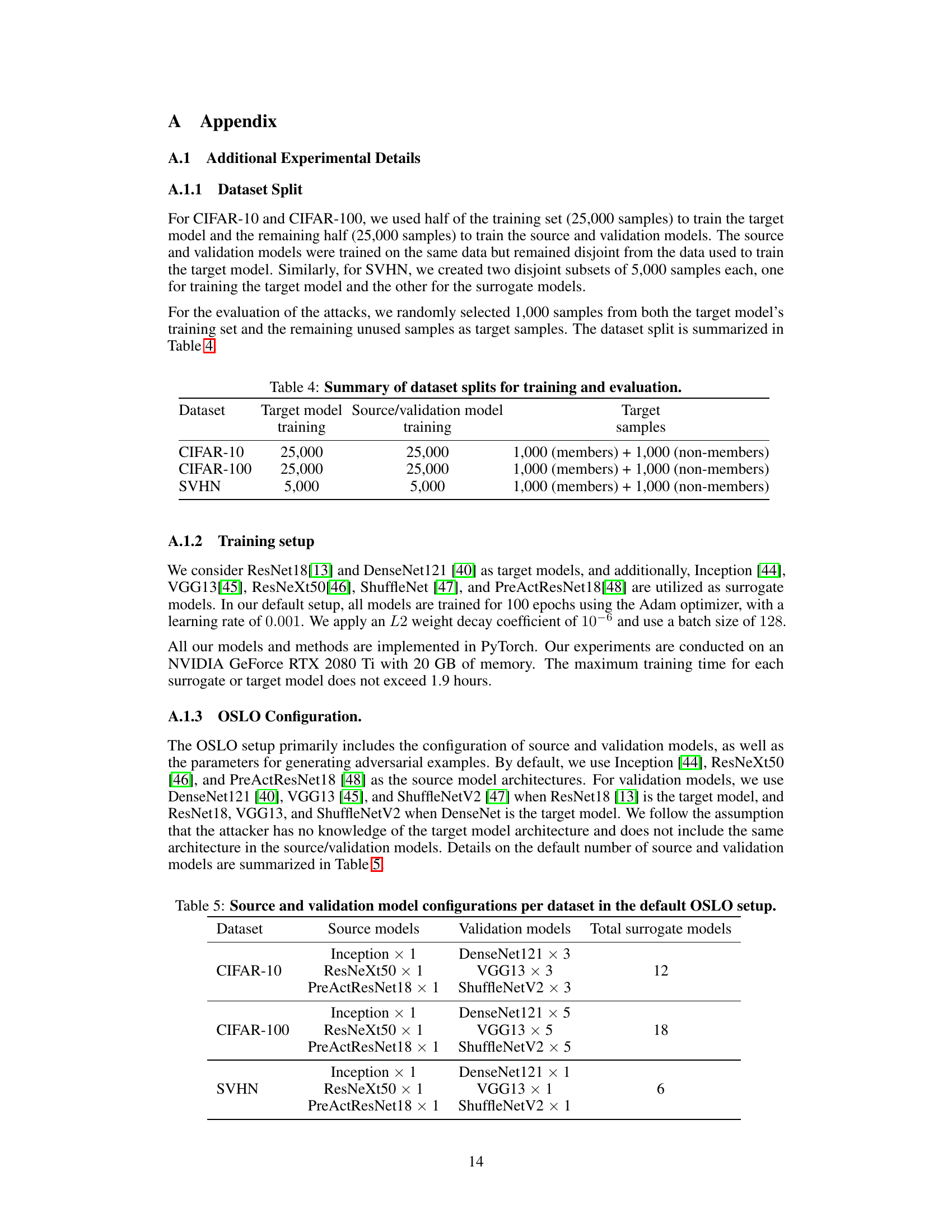

This table details the specific model architectures used for both source and validation models in the OSLO attack. For each dataset (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and SVHN), it lists the number of models of each architecture type used for generating adversarial examples (source models) and for regulating the perturbation magnitude (validation models). The total number of surrogate models used in the attack for each dataset is also provided.

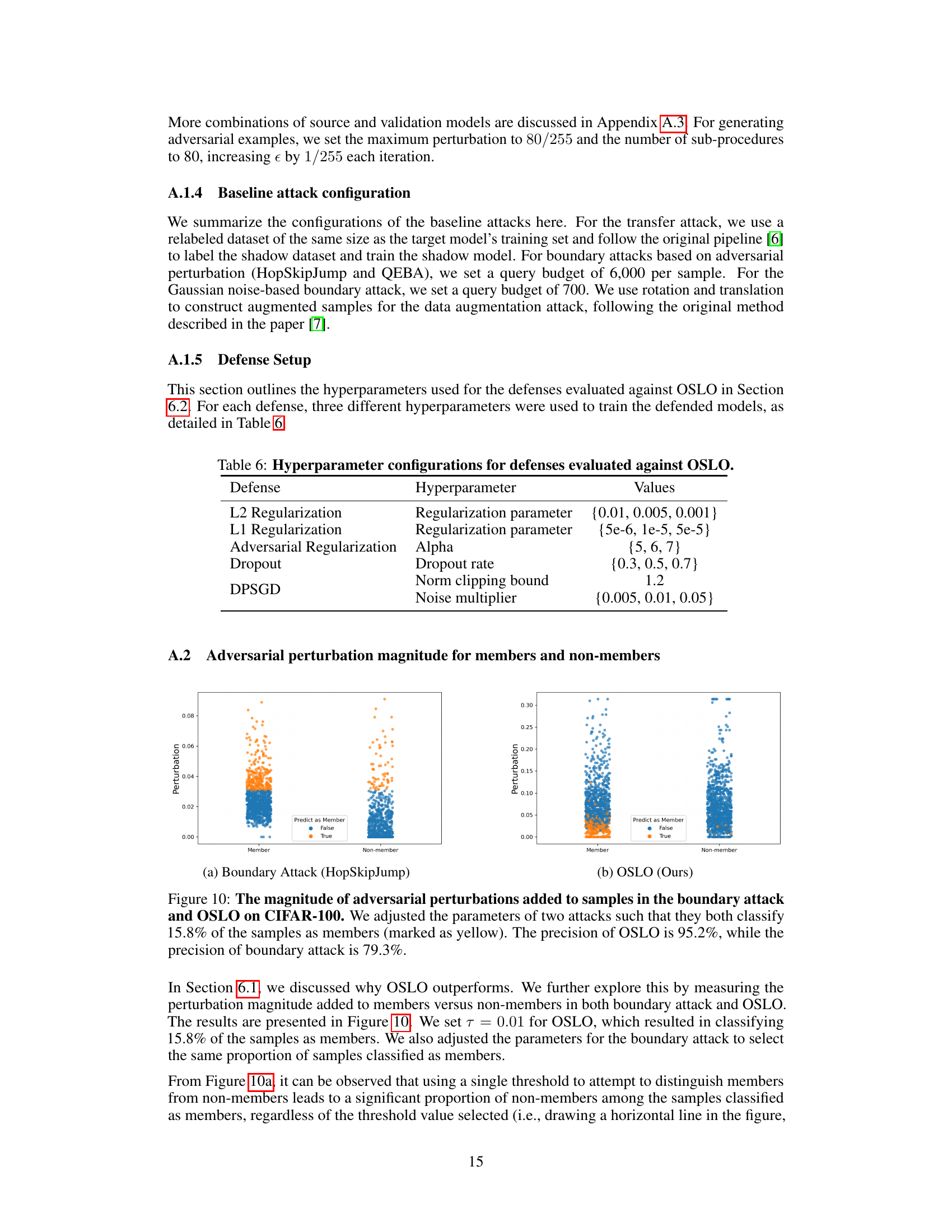

This table presents the hyperparameter configurations used for evaluating six different defense mechanisms against OSLO. For each defense, three different hyperparameter values were used to train the defended models. The defenses include L2 Regularization, L1 Regularization, Adversarial Regularization, Dropout, and DPSGD. The hyperparameters for each defense are listed, along with the specific values used in the experiments. This allows reproducibility of the experiments and better understanding of the experimental setup.

This table compares the performance of the proposed OSLO attack against existing state-of-the-art label-only membership inference attacks. It shows that OSLO achieves significantly higher attack precision than previous methods, even though it only requires a single query to the target model, while others require many more queries (~6000). The table highlights the significant improvement in attack precision of OSLO even under strict conditions (recall greater than 1% on CIFAR-10 using a ResNet18 model).

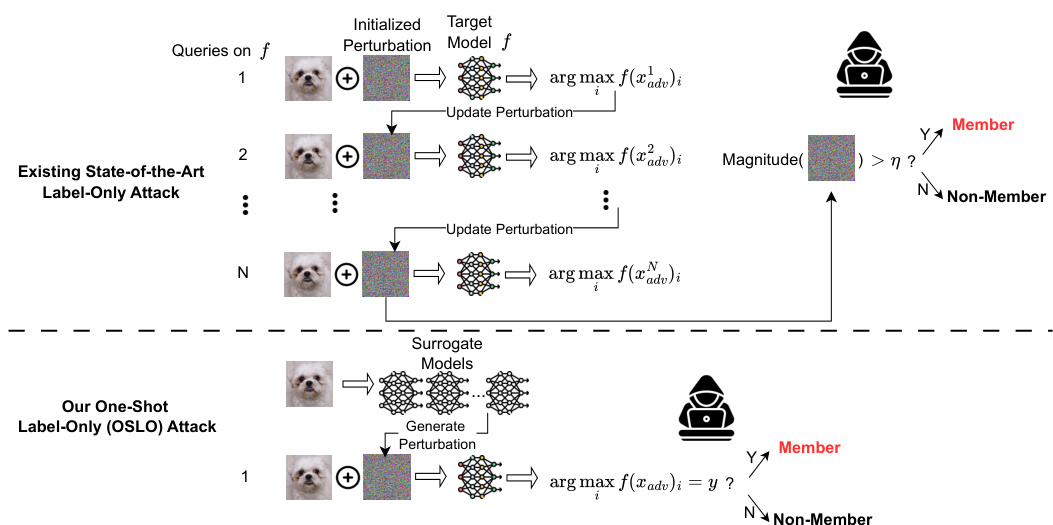

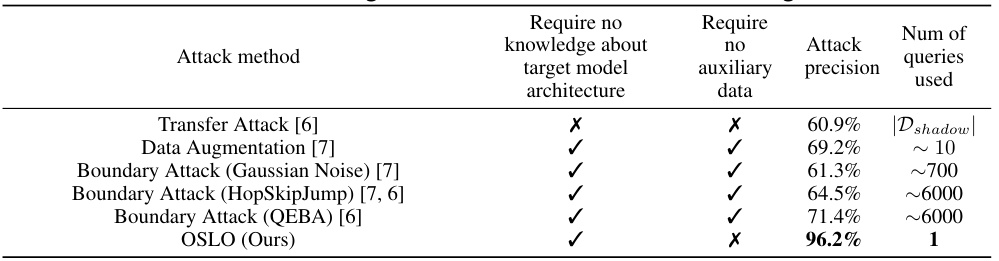

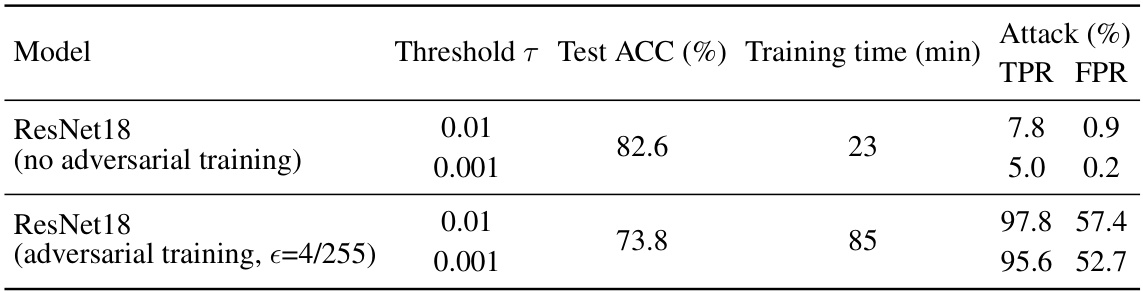

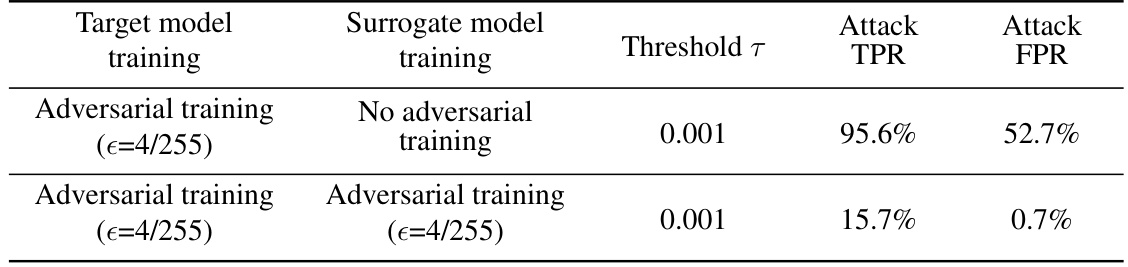

This table presents the results of evaluating OSLO’s performance against ResNet18 target models that were trained with and without adversarial training. The table shows the test accuracy (ACC), training time, and OSLO’s attack performance (TPR and FPR) at different thresholds (T) for both scenarios. It demonstrates the impact of adversarial training on the effectiveness of the OSLO attack.

This table presents the results of evaluating OSLO’s performance against target models trained with adversarial training using ResNet18 on CIFAR-10. It shows the attack’s TPR and FPR under different thresholds (T) when the target model was trained without adversarial training or with adversarial training (€=4/255). This highlights the impact of adversarial training on OSLO’s effectiveness.

Full paper#