↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current zero-shot learning methods often struggle with the generalized zero-shot learning (GZSL) setting, where the model must classify images without knowing if they belong to seen or unseen classes. Existing methods utilizing VLMs (Vision-Language Models) like CLIP often either rely on a base-to-novel division or suffer from weak generalization to unseen classes after fine-tuning. This necessitates a more robust and practical solution.

The proposed Topology-Preserving Reservoir (TPR) method addresses these shortcomings. It introduces a dual-space feature alignment module that combines visual and linguistic features in a latent space and a novel attribute space, leading to better representation of complex relationships. Furthermore, TPR employs a topology-preserving objective to maintain the generalization ability of the pre-trained VLM, ensuring effective performance on both seen and unseen classes. Extensive experiments show that TPR outperforms existing methods on various GZSL benchmarks, demonstrating its effectiveness and practicality.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in zero-shot learning because it tackles the challenging generalized zero-shot learning (GZSL) problem, which is more realistic than the conventional setting. Its novel dual-space feature alignment module and topology-preserving objective significantly improve model generalization to unseen classes, offering a new approach for VLMs. This opens new avenues for improving zero-shot capabilities in various applications and addresses the limitation of current prompt-learning methods that struggle with GZSL.

Visual Insights#

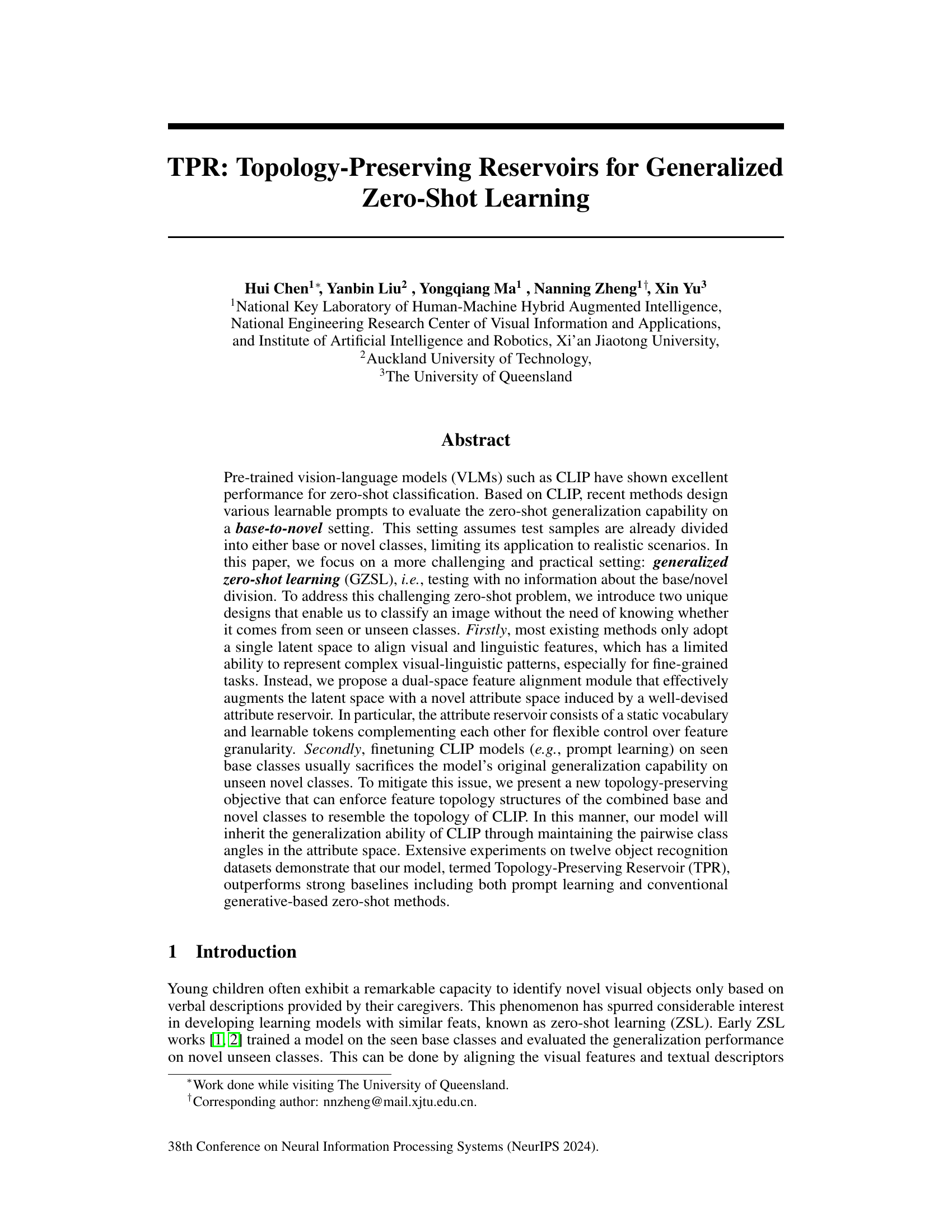

This figure shows a comparison of the performance of different methods on seen and unseen classes in a generalized zero-shot learning (GZSL) setting. Panel (a) presents a radar chart comparing the harmonic mean of seen and unseen class accuracies for several methods, highlighting the superior performance of the proposed method (‘Ours’). Panels (b), (c), and (d) illustrate feature space visualizations for CLIP (before finetuning), CLIP (after finetuning), and the proposed method, respectively, showing how finetuning can negatively impact generalization to unseen classes, and how the proposed method addresses this issue by preserving the original CLIP topology.

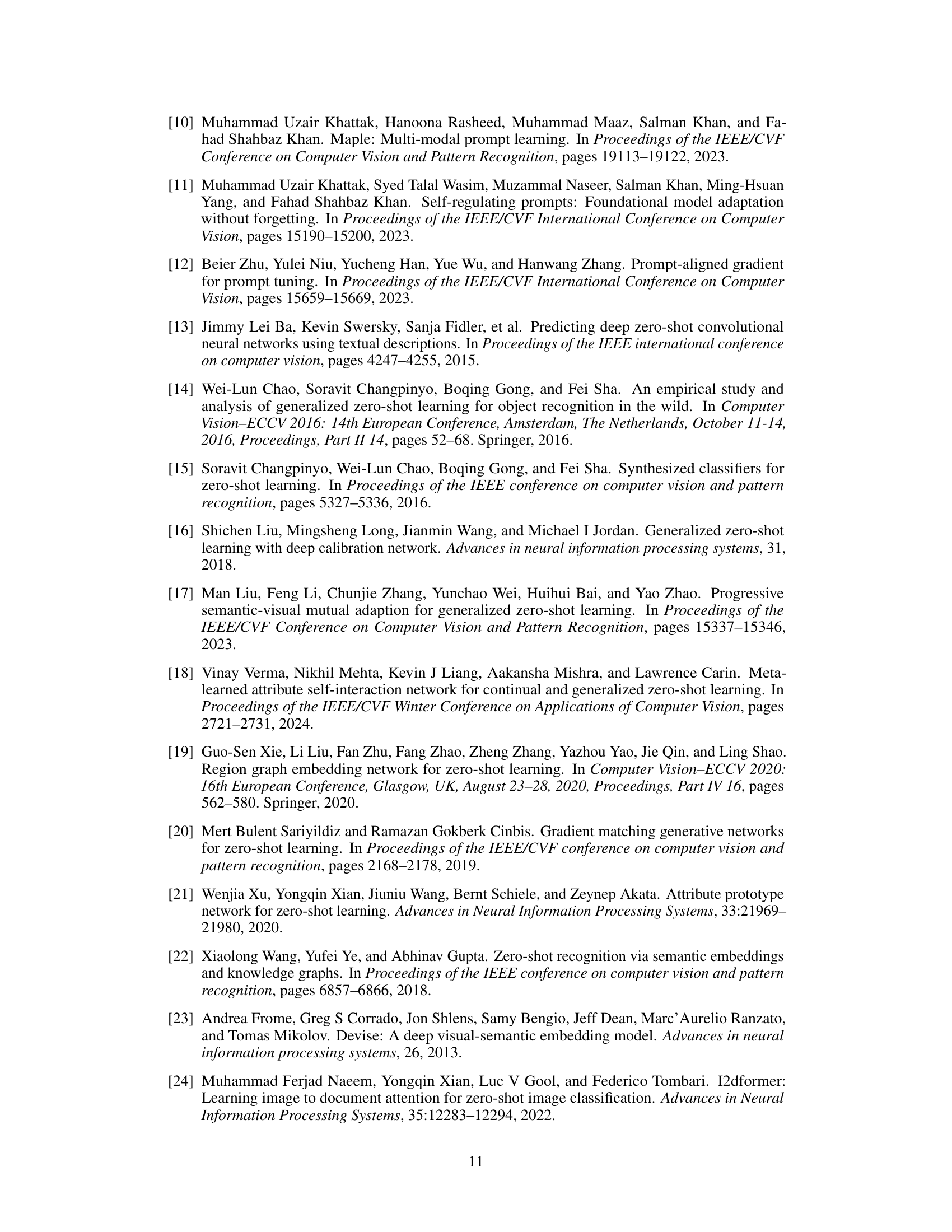

This table compares the performance of the proposed TPR model with various state-of-the-art methods on twelve datasets for generalized zero-shot learning (GZSL). The results show that TPR achieves the best harmonic mean (H) in most datasets and significantly outperforms other methods on fine-grained datasets. It also demonstrates the model’s compatibility with other vision-language models (VLMs).

In-depth insights#

Topology Preserving#

The concept of “Topology Preserving” in the context of a research paper likely refers to a method or technique that maintains the fundamental relationships or structures within a dataset during a transformation or learning process. This is crucial when dealing with high-dimensional data, such as in machine learning, where preserving the inherent relationships between data points is vital for maintaining the model’s performance and generalizability. Topology preservation often involves techniques that focus on preserving distances or similarities between data points, preventing distortions that could negatively impact the model’s ability to accurately learn and classify new unseen data. The goal is typically to avoid a situation where a model trained on a specific dataset becomes overly sensitive or specialized for the training set and fails to generalize well to new data instances that were not present in the initial training data. A topology-preserving approach seeks to achieve robustness and maintain the model’s initial generalization performance by preserving the structure of the original feature space.

Dual-Space Alignment#

The concept of “Dual-Space Alignment” in a research paper likely refers to a method that simultaneously aligns features in two distinct spaces, aiming for improved performance in tasks like zero-shot learning. One space might represent visual features extracted from an image, while another captures semantic or linguistic information from text. By aligning these two spaces, the model learns a mapping between visual appearance and textual descriptions, enabling it to classify unseen objects based on their textual descriptions alone. This dual-space approach addresses limitations of single-space methods, which may struggle to capture complex relationships between visual and textual data. The effectiveness hinges on the design of the two spaces and the alignment technique. Successful alignment will allow the model to generalize effectively to novel classes that were not seen during training, showcasing strong zero-shot capabilities. The choice of appropriate projection methods and loss functions for this alignment is crucial for overall performance. This dual-space strategy can improve model robustness and generalization by providing a richer feature representation that encapsulates both visual and semantic information more comprehensively.

GZSL Benchmark#

A generalized zero-shot learning (GZSL) benchmark is a crucial element for evaluating the performance of algorithms designed to classify images into categories they haven’t been explicitly trained on. A robust benchmark must encompass a diverse set of datasets, carefully chosen to represent various levels of visual complexity, inter-class similarity, and attribute ambiguity. The selection of these datasets should reflect considerations such as class balance, fine-grained vs. coarse-grained categories, and the quality of available annotations (e.g., textual descriptions, attributes). The evaluation metrics employed within the benchmark must be carefully considered and should go beyond simple accuracy. Standard metrics for GZSL frequently involve harmonic mean to account for potential biases towards seen classes. Additionally, a strong benchmark should provide clear guidelines on data splits and preprocessing steps to ensure consistent and comparable results across different research efforts. Finally, a well-designed GZSL benchmark should be regularly updated to include newer datasets and evaluation metrics to account for advancements in the field. This ensures the benchmark remains a relevant and challenging tool for evaluating the progress of GZSL research.

CLIP Generalization#

CLIP’s zero-shot capabilities, while impressive, suffer from limitations in generalization, especially to unseen classes. Fine-tuning CLIP models often compromises their original generalization ability, leading to poor performance on novel data. This paper addresses this challenge by proposing a novel method that leverages a dual-space feature alignment to enrich feature representations. A key aspect of this strategy is a topology-preserving objective which ensures that the learned feature space maintains the original relationship between classes found in pre-trained CLIP’s embedding space. This is crucial for preserving the model’s inherent generalization strength. The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated through extensive experiments which showcase the superiority of the proposed method compared to baselines and state-of-the-art approaches on numerous datasets. The dual-space approach allows for better capture of visual-linguistic relationships, crucial for zero-shot tasks. Maintaining CLIP’s topology helps to mitigate the overfitting to seen classes often observed in fine-tuned models, directly addressing the weakness of CLIP generalization.

Future of TPR#

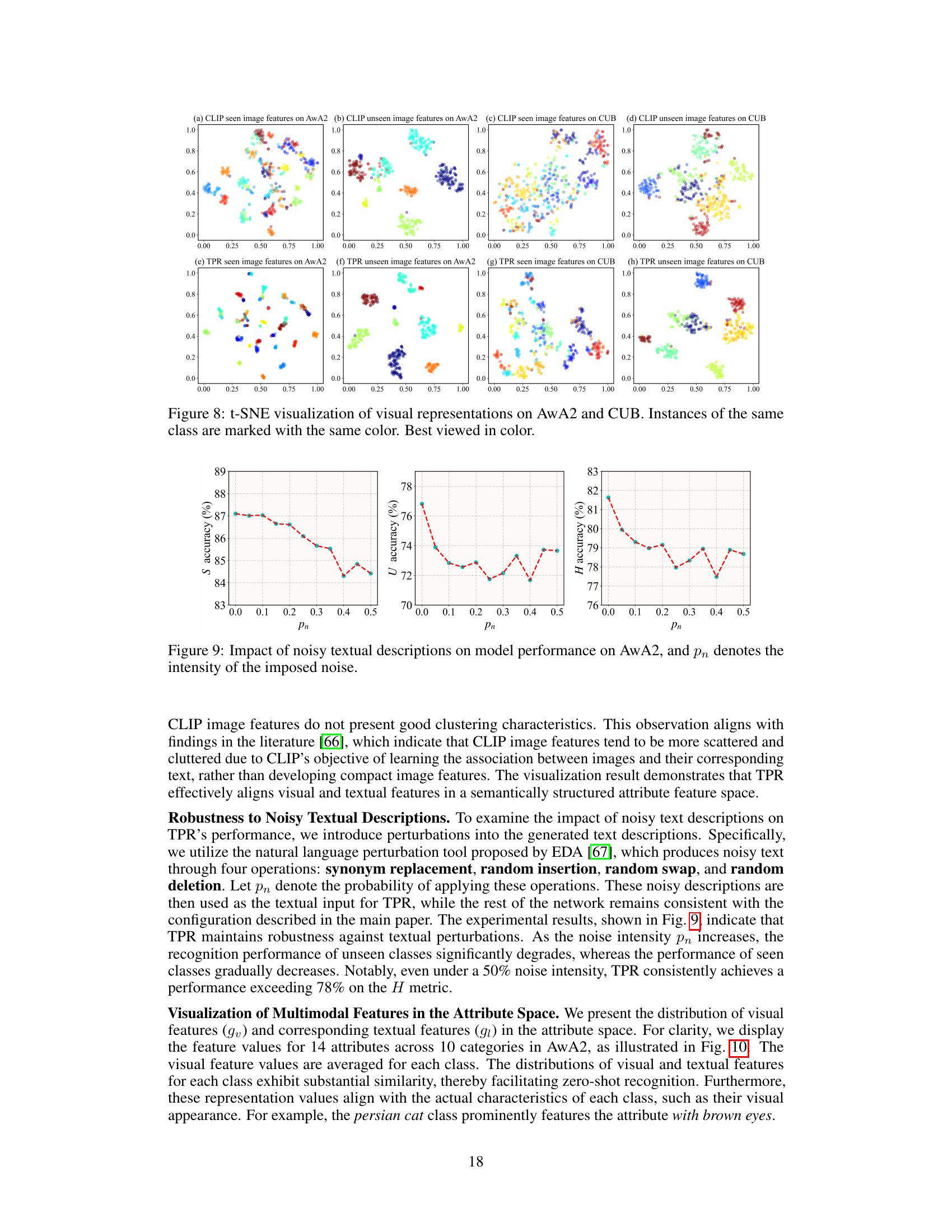

The future of Topology-Preserving Reservoirs (TPR) looks promising, particularly in addressing the limitations of current zero-shot learning (ZSL) methods. Further research could focus on enhancing the attribute reservoir, perhaps by incorporating more sophisticated methods for feature extraction and selection, or by dynamically adapting the reservoir based on the specific task or domain. Exploring different attention mechanisms within the dual-space alignment module could improve fine-grained feature alignment and boost performance on complex or fine-grained tasks. Investigating the robustness of TPR to noisy or incomplete data is crucial for real-world applications. Extending TPR beyond image classification to other modalities like video or audio would significantly broaden its applicability. Finally, a thorough investigation into the computational efficiency and scalability of TPR is necessary to make it practical for large-scale deployment.

More visual insights#

More on figures

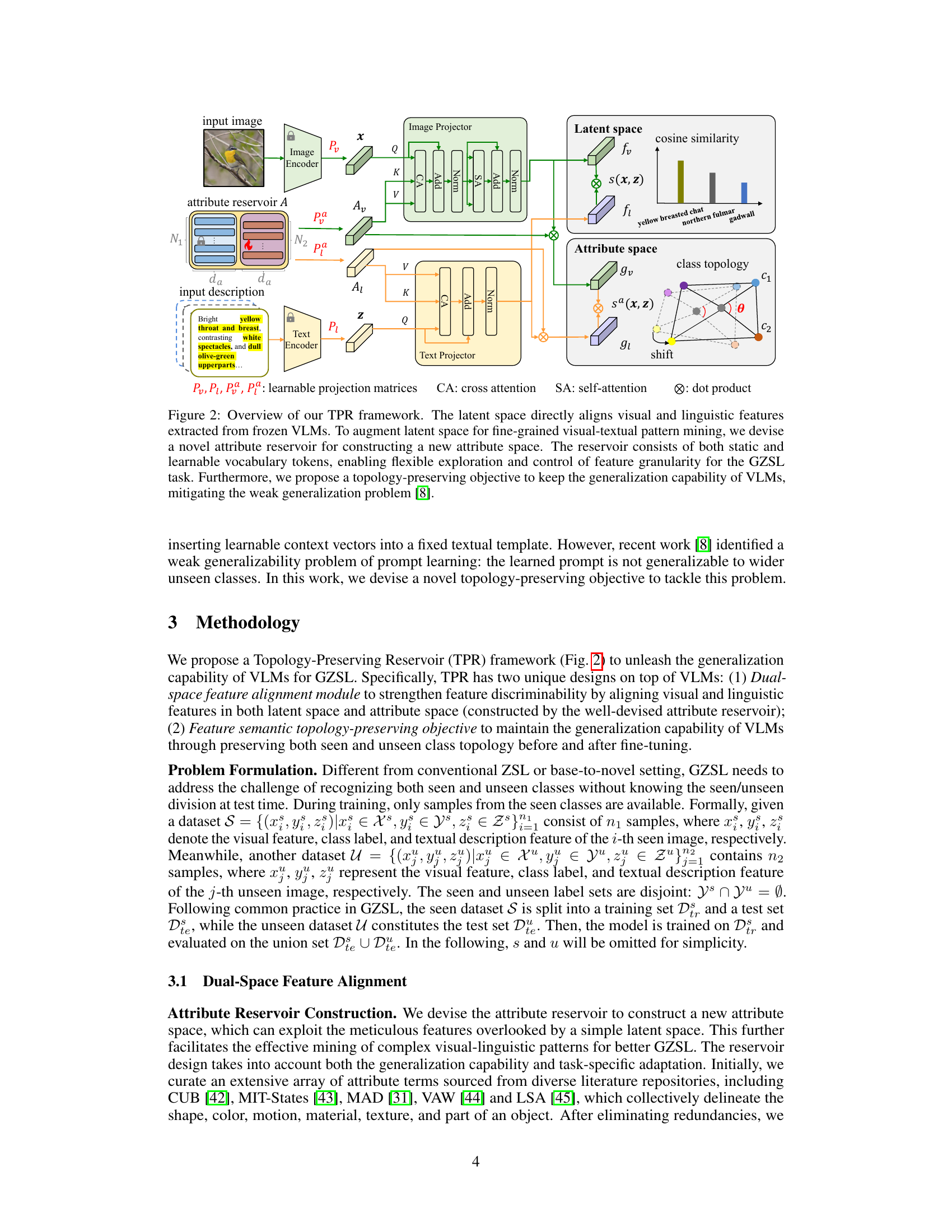

This figure shows the architecture of the Topology-Preserving Reservoir (TPR) framework, which is the core method proposed in the paper. It uses a dual-space feature alignment module with a novel attribute reservoir to improve visual-linguistic feature representation and a topology-preserving objective to maintain the generalization capability of pre-trained Vision-Language Models (VLMs).

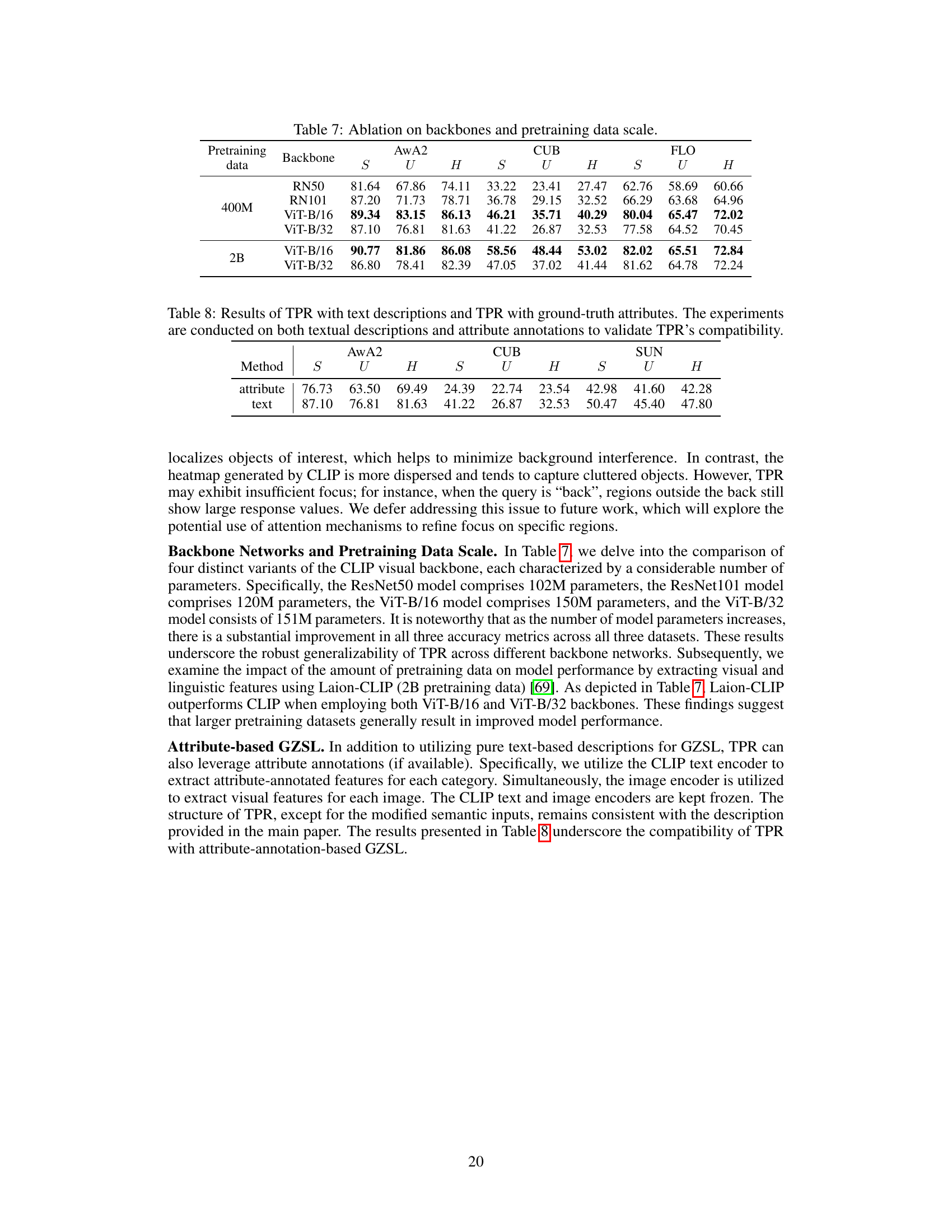

This figure shows the impact of the size of the attribute vocabulary on the model’s performance across three datasets (AwA2, CUB, and FLO). The x-axis represents the attribute vocabulary size, and the y-axis represents the accuracy (S, U, and H). The results indicate that increasing the attribute vocabulary size generally improves performance. The curves for each dataset show the separate performances on seen (S), unseen (U) and harmonic mean (H) data.

This figure shows the effect of varying the size of the attribute vocabulary on the performance of the TPR model. The x-axis represents the size of the vocabulary, and the y-axis represents the accuracy (S, U, and H metrics) achieved on three different datasets: AwA2, CUB, and FLO. The plots demonstrate how changing the size of the attribute vocabulary affects the model’s ability to generalize to seen and unseen classes in the generalized zero-shot learning setting. The trend shows that increasing the vocabulary size improves performance on unseen classes, while it may not always increase performance on seen classes.

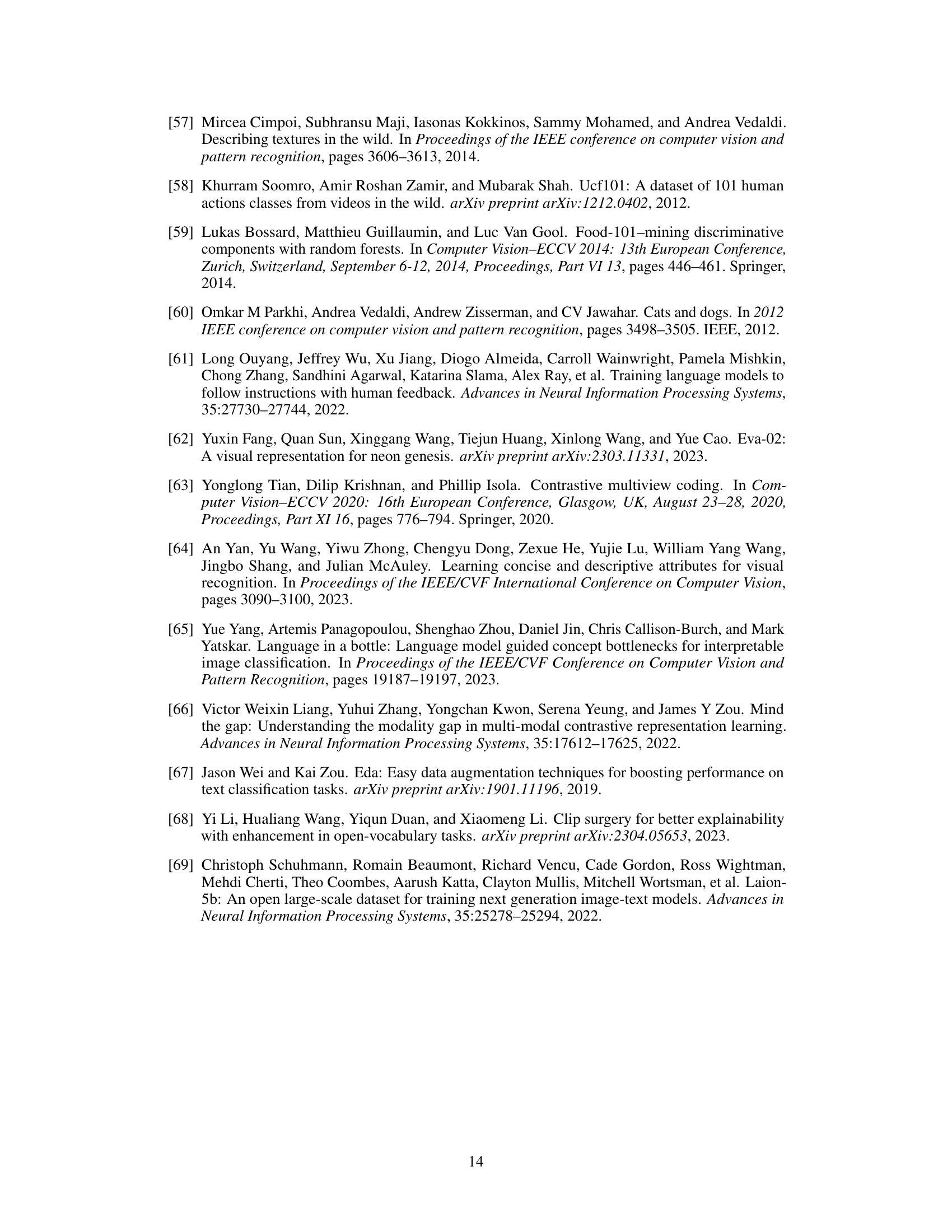

The figure shows the impact of using multiple textual descriptions (n=1 to 5) on the performance of the model for the CUB dataset. For each class, 10 random sets of n descriptions were used, and the average accuracy for seen (S), unseen (U), and harmonic mean (H) classes is plotted with error bars. The results indicate that increasing the number of descriptions generally improves performance, especially for unseen classes, and stabilizes the results. The most noticeable gain comes from increasing from 1 description to 2.

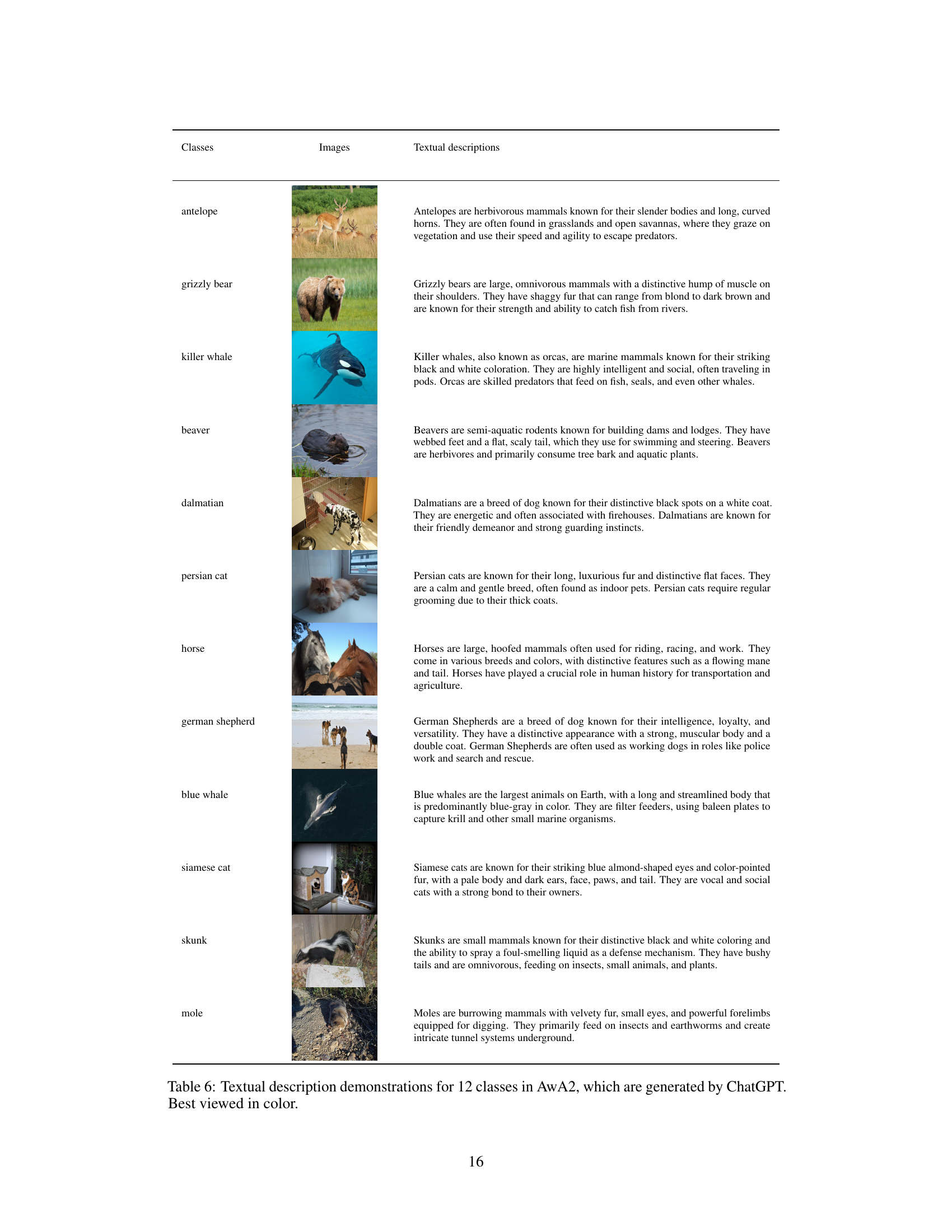

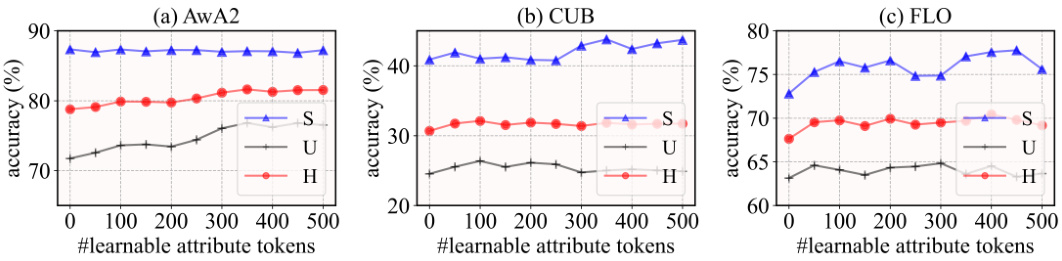

This figure displays bar charts illustrating the cosine similarity between automatically generated textual descriptions and ground-truth attribute annotations. The left chart shows the distribution for the AwA2 dataset, while the right chart shows the distribution for the CUB dataset. Each bar represents a different class, and the height of the bar corresponds to the cosine similarity between the textual and attribute feature vectors for that class. A higher bar indicates a greater similarity between the descriptions and annotations for that class. The charts aim to demonstrate the quality of the automatically generated descriptions, showing that they capture attributes similar to those in the ground truth.

This figure shows the architecture of the proposed TPR (Topology-Preserving Reservoir) framework. It highlights the dual-space feature alignment module which uses both a latent space and an attribute space (created from a novel attribute reservoir) to effectively align visual and linguistic features for fine-grained tasks. The topology-preserving objective is also shown, designed to maintain the generalization ability of the pre-trained Vision-Language Model (VLM) by preserving the relationships between classes. The attribute reservoir itself is composed of static vocabulary and learnable tokens, offering flexibility in feature granularity.

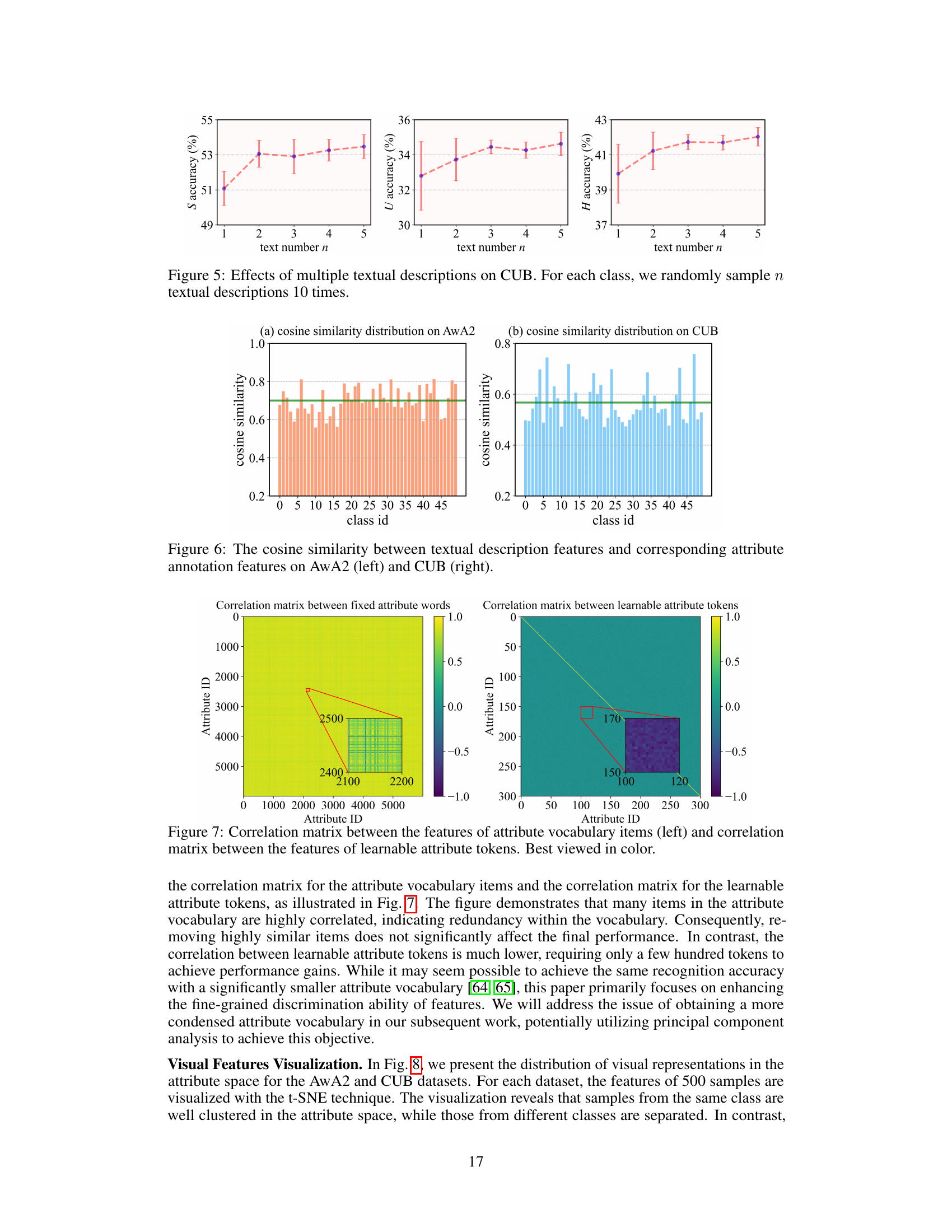

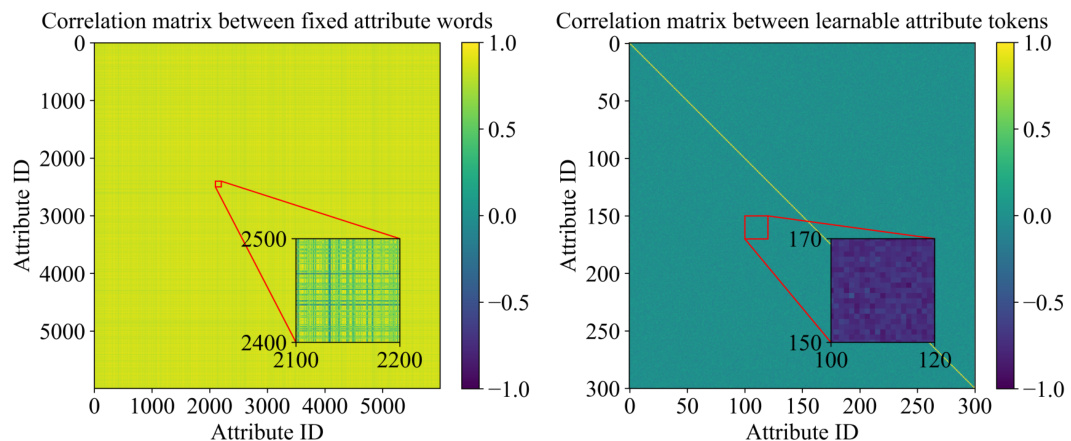

This figure visualizes the distribution of visual features in the attribute space learned by TPR and CLIP for both AwA2 and CUB datasets. The t-SNE algorithm is used to reduce the dimensionality of the features for visualization. Each point represents a sample, and points of the same color represent instances of the same class. The visualization demonstrates how well TPR groups samples of the same class together, compared to CLIP, indicating better feature separability and class clustering by TPR.

This figure visualizes the distribution of visual features extracted by both CLIP and TPR in the attribute space using t-SNE. It shows how well TPR clusters instances of the same class together compared to CLIP, demonstrating the effectiveness of TPR in aligning visual features and preserving the semantic topology of classes.

This figure shows the architecture of the Topology-Preserving Reservoir (TPR) framework proposed in the paper. It illustrates how visual and linguistic features are extracted from pre-trained vision-language models (VLMs), aligned in a latent space, and further enhanced by a novel attribute reservoir to improve fine-grained feature representation. The attribute reservoir uses both static and learnable tokens, allowing for flexible control over feature granularity. A topology-preserving objective ensures that the model maintains the generalization capability of the VLMs, addressing the problem of weak generalization after fine-tuning.

This figure shows the performance comparison of the proposed TPR method against state-of-the-art methods in the generalized zero-shot learning setting. (a) presents a clear visual demonstration of TPR’s superior performance on both seen and unseen classes, showcasing a significant improvement over existing methods. Subfigures (b), (c), and (d) illustrate the negative impact of fine-tuning CLIP models on unseen classes and how TPR addresses this ‘weak generalization’ problem by preserving the original CLIP feature space topology.

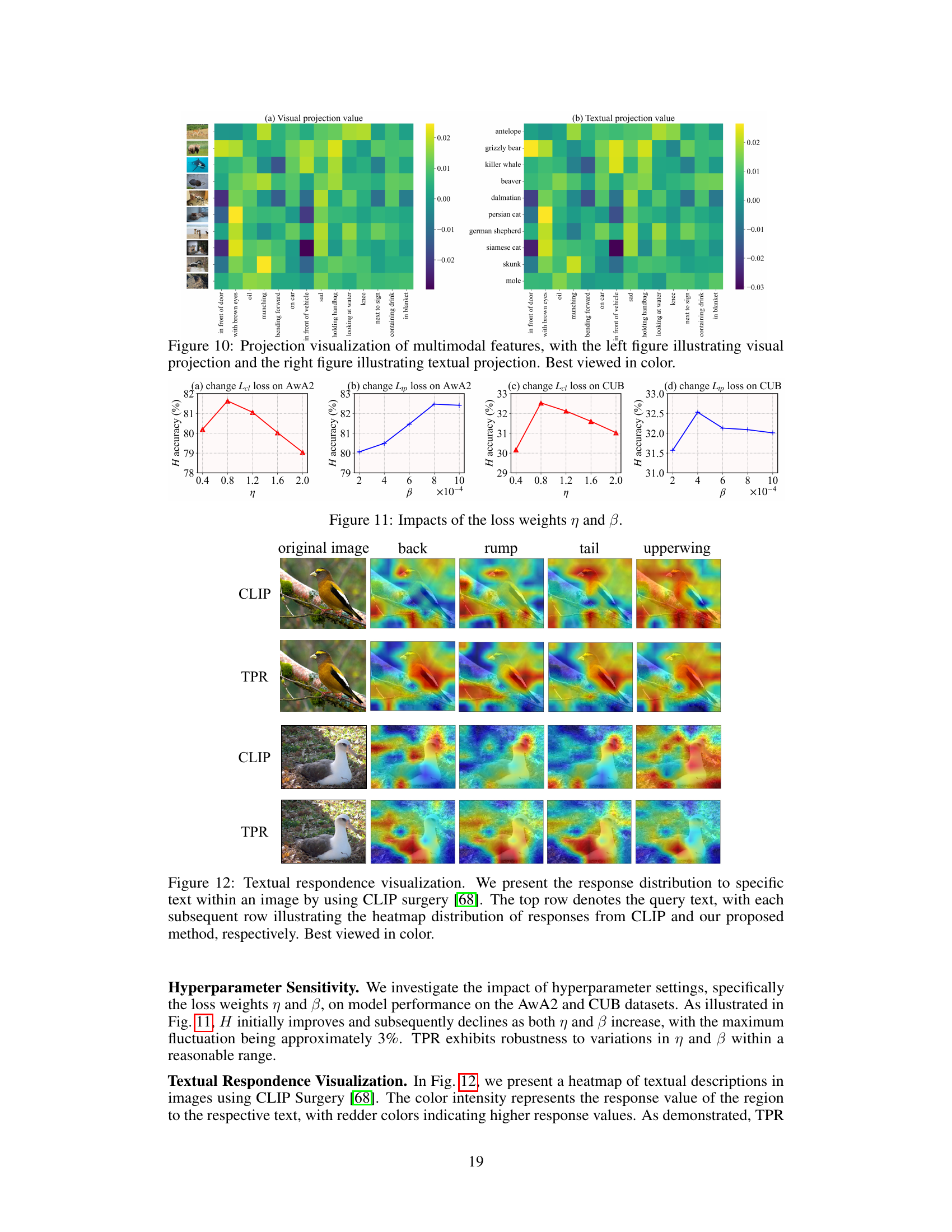

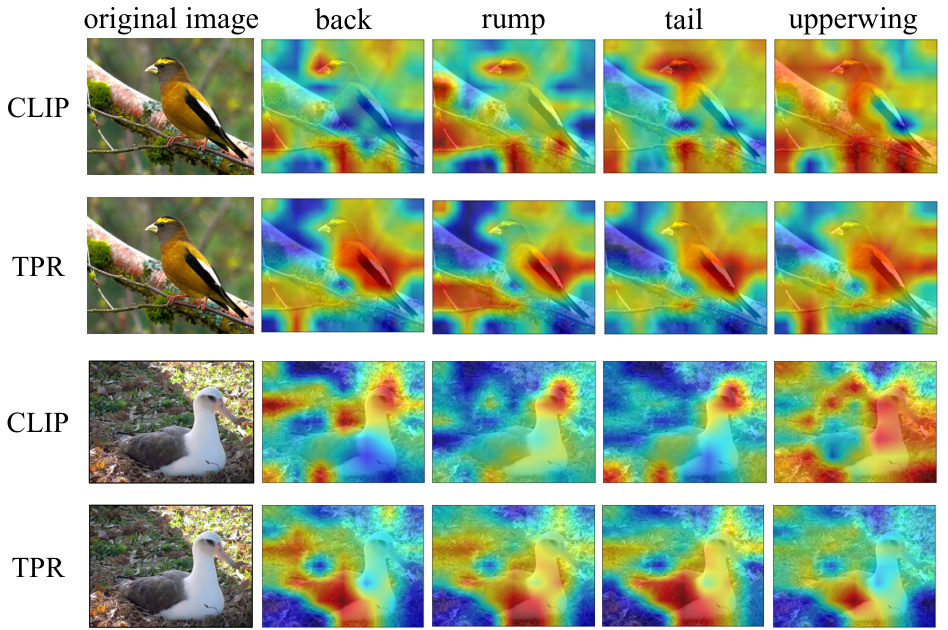

This figure visualizes the response distribution of CLIP and TPR to specific text within images using CLIP surgery. The heatmaps show the response intensity for each query word. The top row shows the query texts, and the subsequent rows show heatmaps for CLIP and TPR, respectively. The figure demonstrates that TPR better localizes the regions of interest mentioned in the texts compared to CLIP.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of the proposed TPR model against other state-of-the-art methods on twelve object recognition datasets using the generalized zero-shot learning (GZSL) setting. The GZSL setting is more challenging than the conventional zero-shot learning setting because it requires the model to classify images from both seen and unseen classes without knowing which is which. The table shows that TPR achieves the best harmonic mean (H) in 11 out of 12 datasets, indicating its superior performance in this challenging setting. Fine-grained datasets are also highlighted, with TPR showing the best performance.

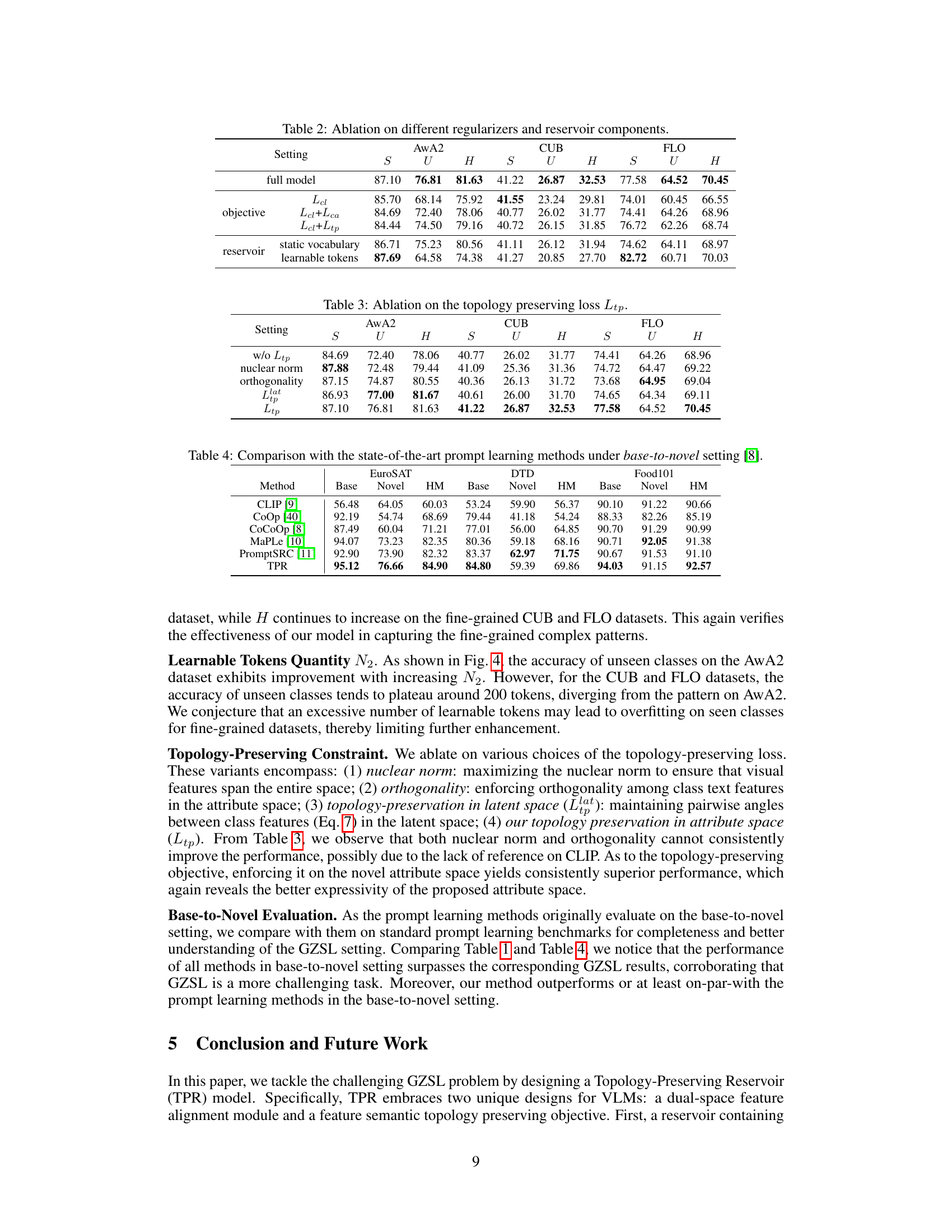

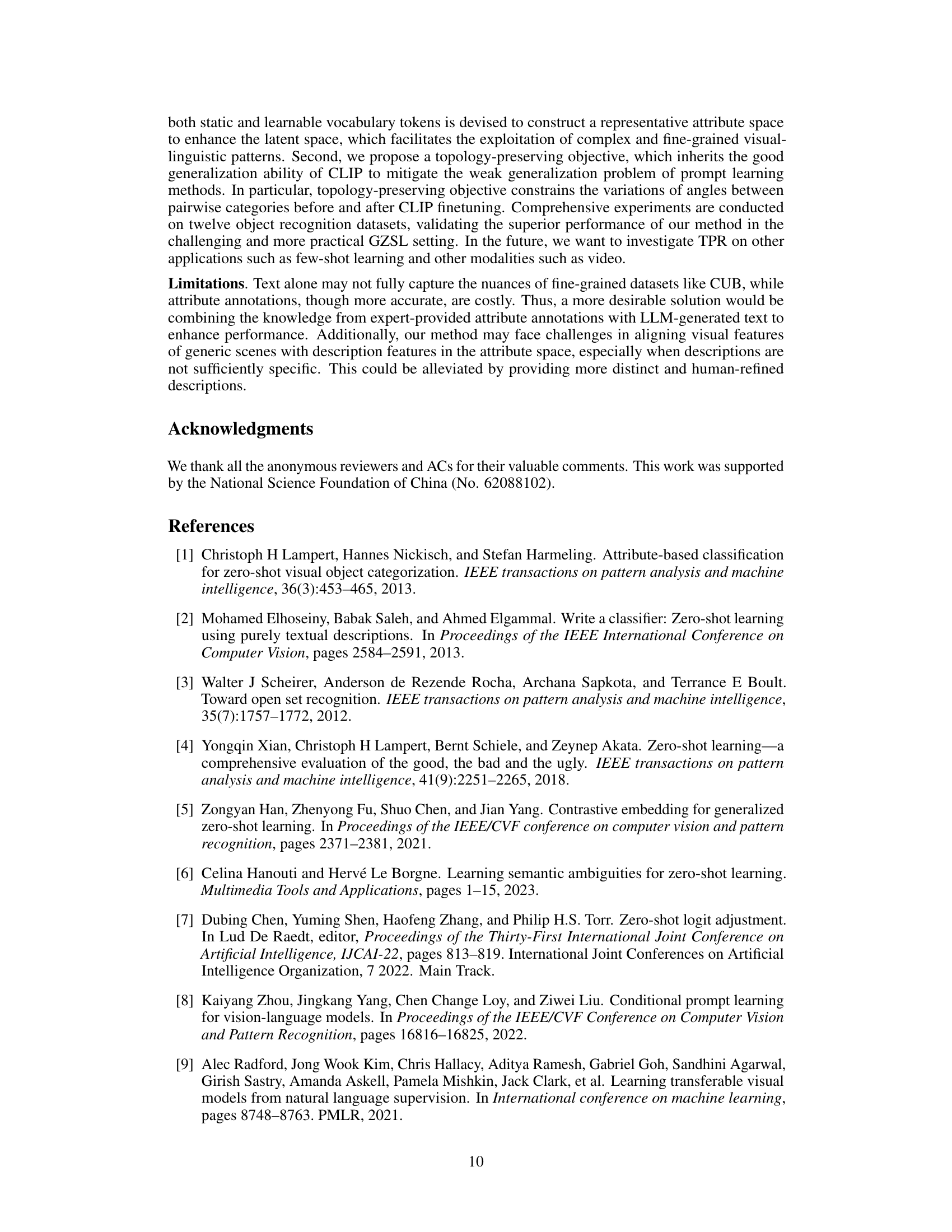

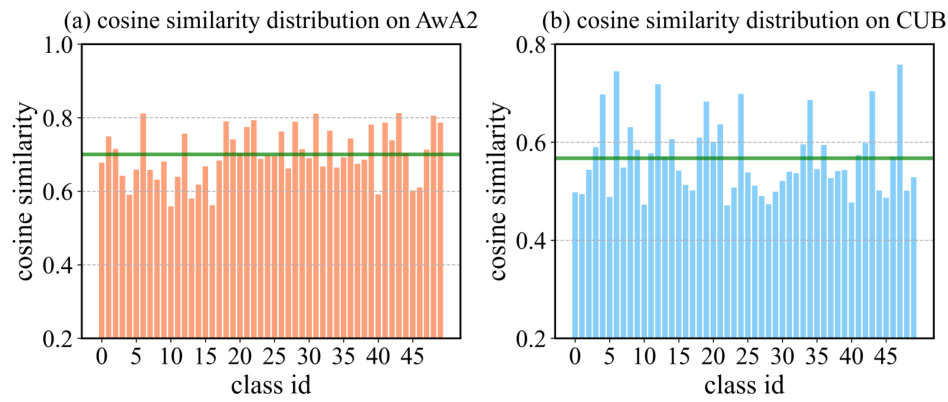

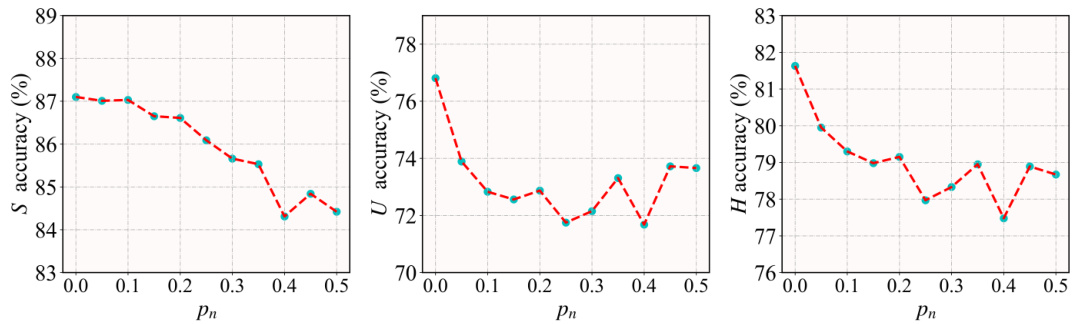

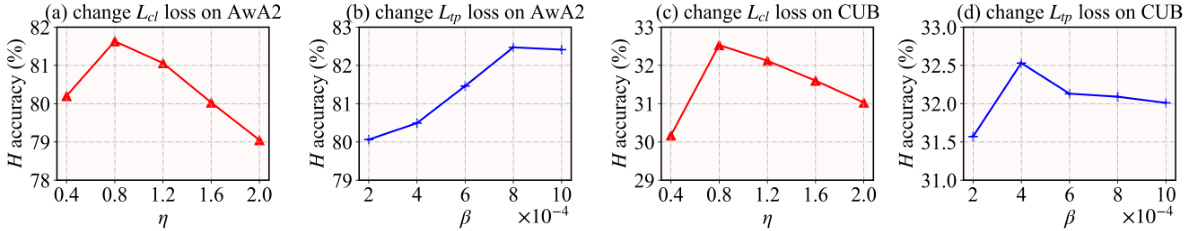

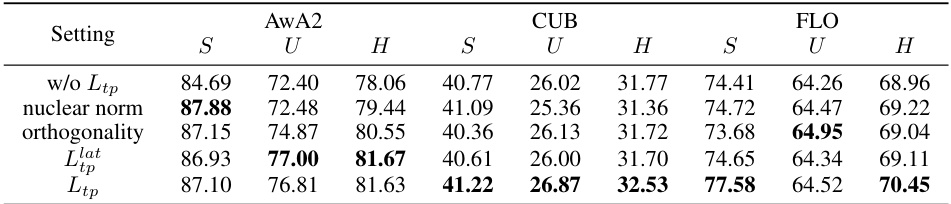

This table presents the ablation study of the proposed Topology-Preserving Reservoir (TPR) model. It shows the impact of different components and loss functions on the model’s performance across three datasets (AwA2, CUB, FLO). Specifically, it compares the full model’s performance against versions with only the latent space contrastive loss, with added attribute space contrastive loss, with added topology preserving loss, and with different reservoir configurations (static vocabulary only, learnable tokens only). The results demonstrate the contribution of each component to the overall performance improvement and highlight the effectiveness of the dual-space feature alignment and the topology-preserving objective.

This table compares the performance of the proposed TPR model with eleven other state-of-the-art methods on twelve object recognition datasets in a generalized zero-shot learning (GZSL) setting. The harmonic mean (H) of seen and unseen class accuracy is used as the main evaluation metric. The results show that TPR outperforms other methods on most datasets, particularly excelling on fine-grained datasets.

This table compares the performance of the proposed TPR model against several state-of-the-art methods on twelve object recognition datasets. The comparison is done using the harmonic mean (H) of the accuracies on both seen and unseen classes in a generalized zero-shot learning (GZSL) setting. The results show that TPR achieves superior performance, especially on fine-grained datasets.

This table presents a comparison of the proposed TPR model’s performance against other state-of-the-art methods on 12 object recognition datasets using the generalized zero-shot learning (GZSL) setting. The harmonic mean (H) of seen and unseen class accuracies is used as the primary evaluation metric. The table highlights TPR’s superior performance, achieving the best H score in 11 out of the 12 datasets, particularly excelling on fine-grained datasets.

This table compares the performance of the proposed TPR model with other state-of-the-art methods on twelve object recognition datasets in a generalized zero-shot learning setting (GZSL). The results are presented as the harmonic mean (H) of the accuracy on seen and unseen classes, along with individual seen (S) and unseen (U) class accuracies. The table highlights TPR’s superior performance, achieving the best harmonic mean in eleven out of twelve datasets and showcasing its strength particularly on fine-grained datasets.

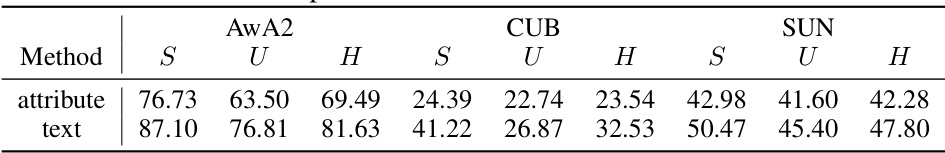

This table compares the performance of the proposed TPR model using two different types of semantic information: text descriptions and ground-truth attributes. The results are presented for three benchmark datasets (AwA2, CUB, and SUN), showing the accuracy (S) on seen classes, the accuracy (U) on unseen classes, and the harmonic mean (H) across seen and unseen classes. This comparison helps to assess the model’s robustness and how well it generalizes across different semantic representations.

Full paper#