↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing methods for interpreting language models using Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) suffer from a shrinkage bias, systematically underestimating feature activations. This bias negatively impacts reconstruction fidelity and the interpretability of extracted features. Addressing this limitation is crucial for advancing research in mechanistic interpretability.

The paper introduces Gated Sparse Autoencoders (GSAEs), which overcome the limitations of SAEs by separating feature selection and magnitude estimation. The key is applying the L1 penalty only to the feature selection process. Results show that GSAEs achieve Pareto improvements over baseline SAEs across various models and layers, offering better reconstruction fidelity at similar sparsity levels, thus resolving the shrinkage issue. Human evaluation suggests comparable interpretability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on mechanistic interpretability of large language models. It introduces a novel approach that directly addresses the limitations of existing methods, paving the way for more accurate and efficient techniques in understanding complex neural networks. The improved interpretability and efficiency offered by this method significantly advance research in this growing field.

Visual Insights#

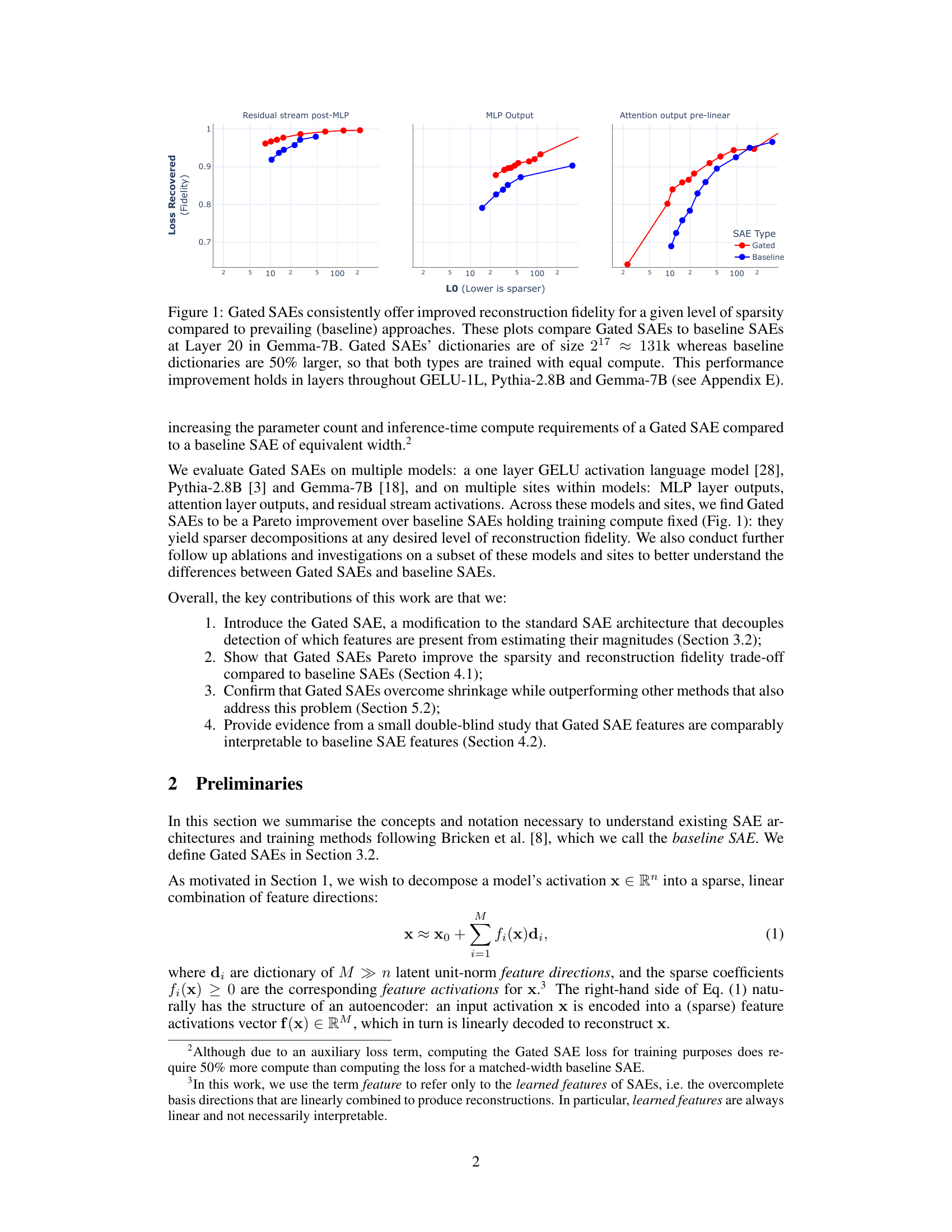

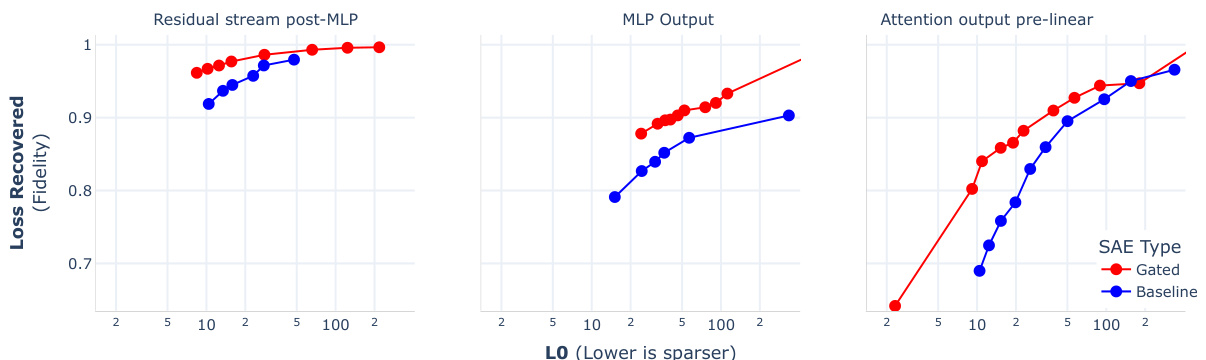

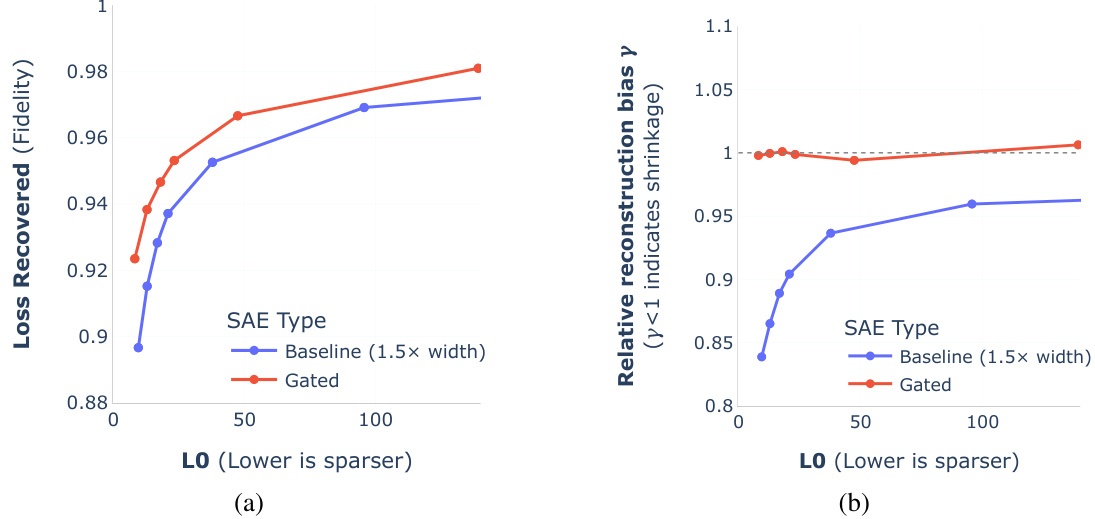

This figure compares the performance of Gated Sparse Autoencoders (Gated SAEs) and baseline SAEs in terms of reconstruction fidelity (Loss Recovered) and sparsity (L0). The plots show that Gated SAEs achieve better reconstruction fidelity for a given level of sparsity across different layers (Layer 20 shown, but similar results across layers in other models) and model types (Gemma-7B, GELU-1L, Pythia-2.8B). The dictionaries used for Gated SAEs are smaller than the baseline SAEs (131k vs 50% larger), demonstrating a Pareto improvement where Gated SAEs offer better performance with less computational cost.

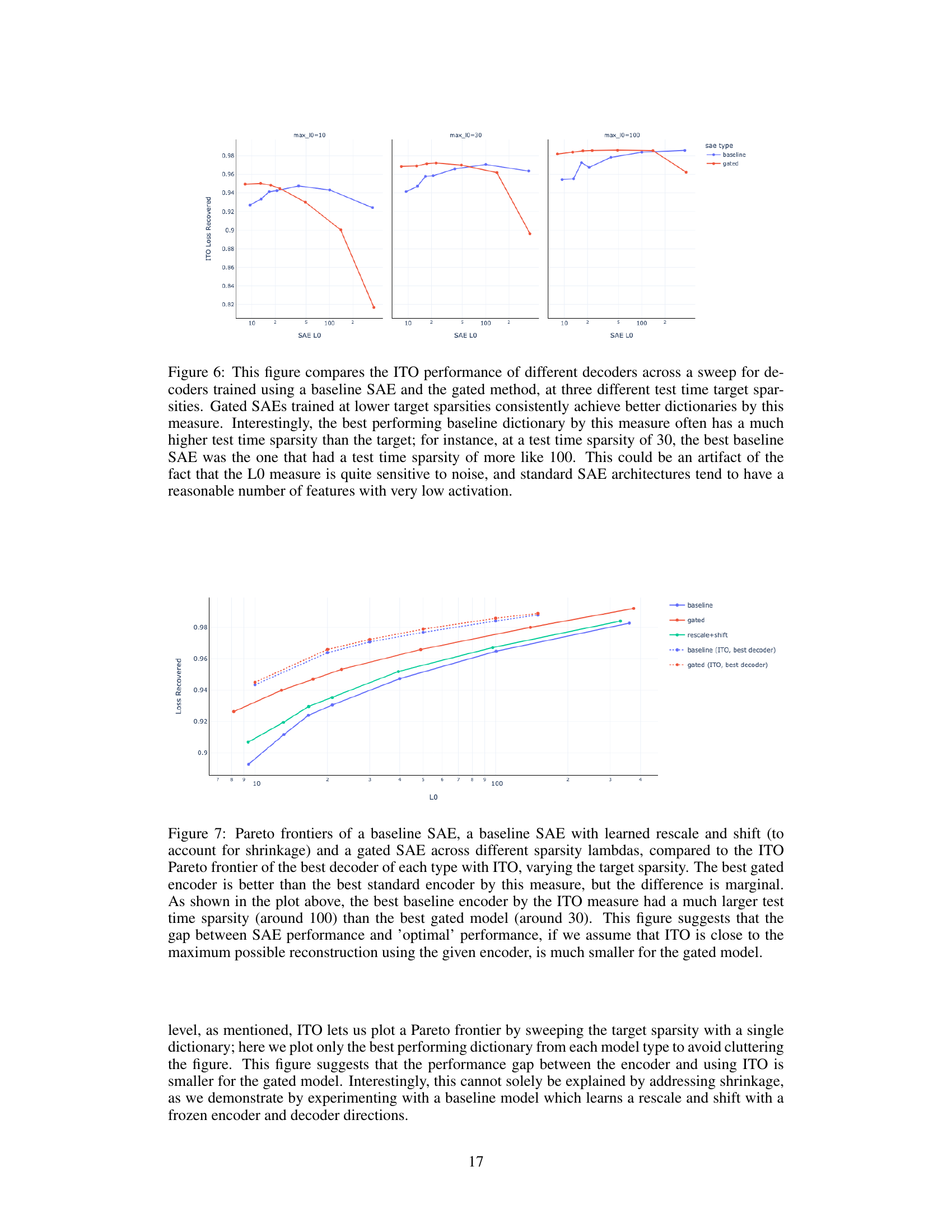

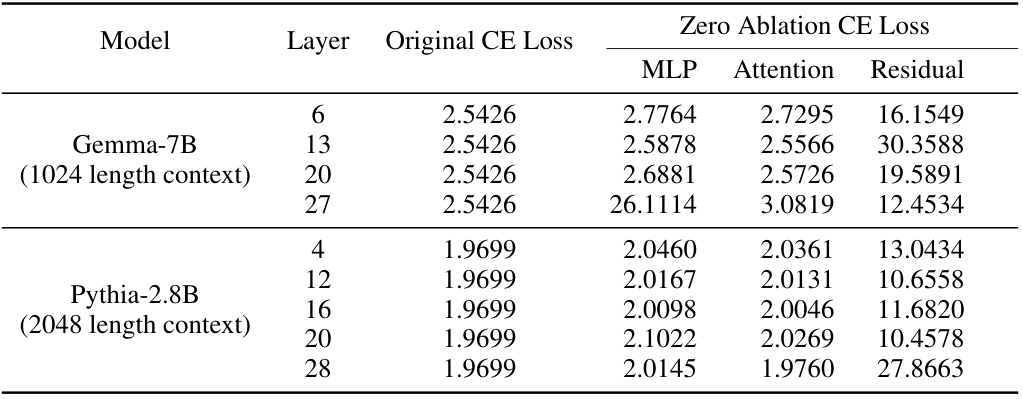

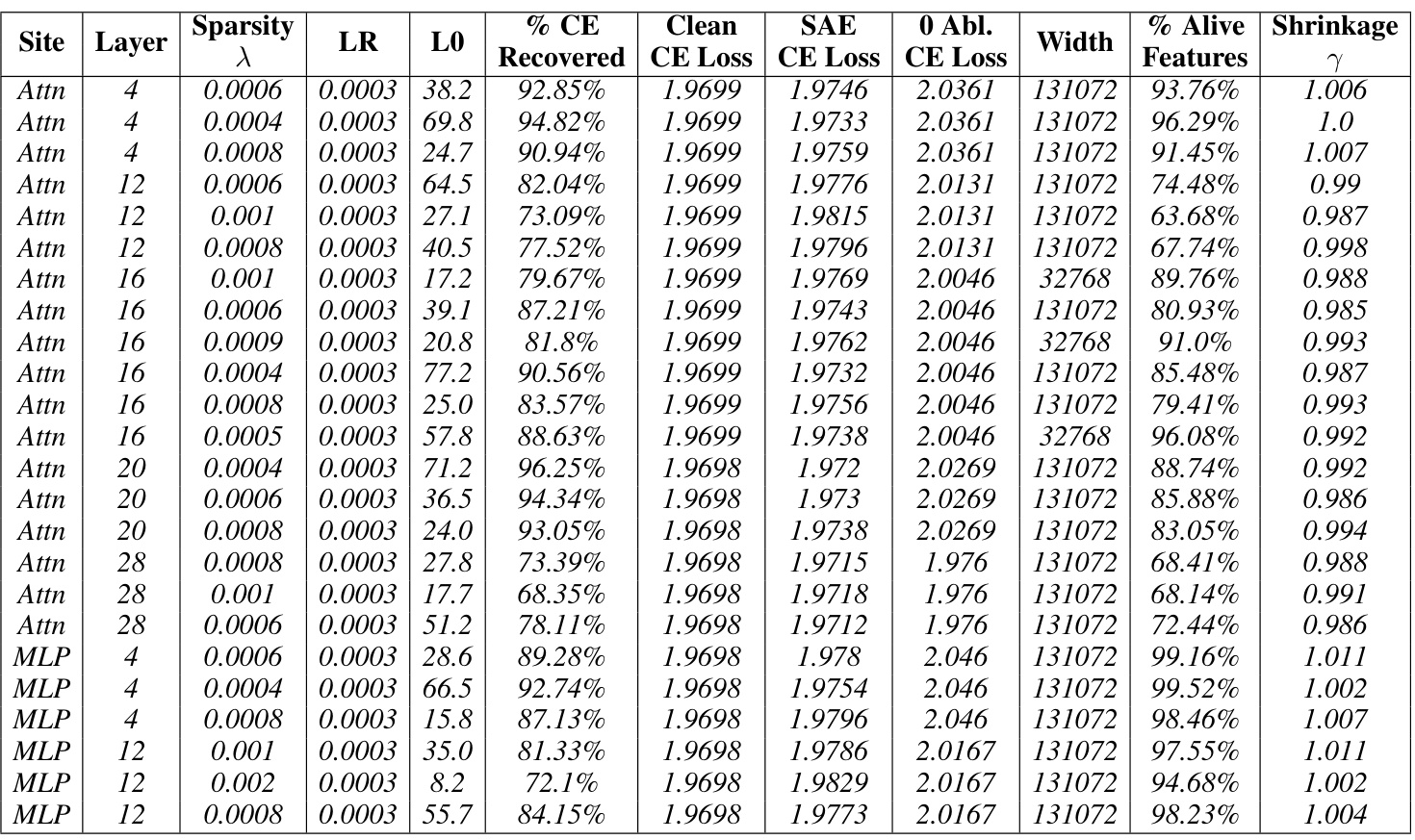

This table presents the cross-entropy loss for the original language models (Pythia-2.8B and Gemma-7B) and the loss after zeroing out specific layers (MLP, Attention, Residual) within those models. This helps quantify the impact of each layer on the model’s overall performance and is used to contextualize and interpret the loss recovered metric used in other tables.

In-depth insights#

Gated SAE Design#

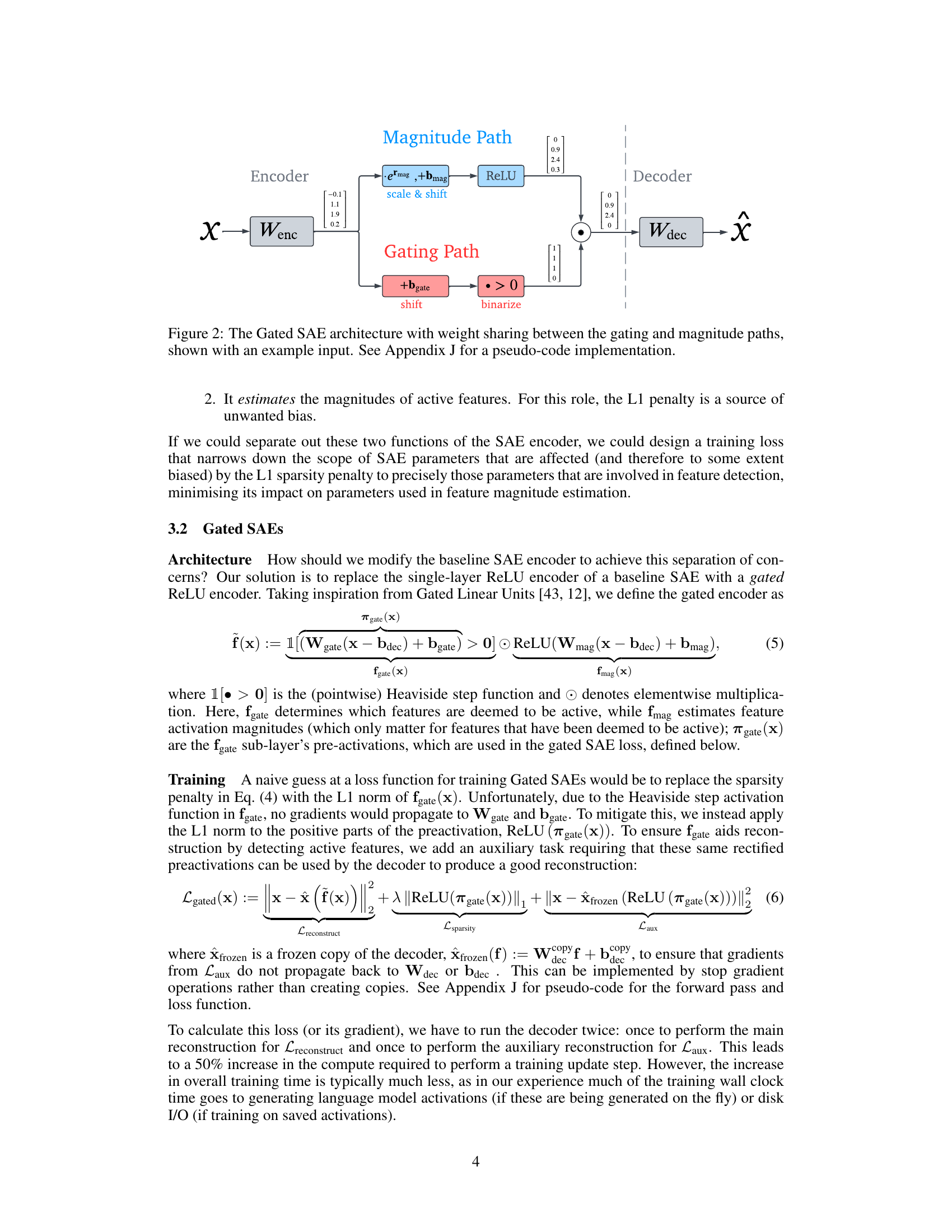

The Gated SAE design is a novel approach to sparse autoencoding that addresses limitations of standard SAEs by decoupling feature selection from magnitude estimation. The core innovation lies in the use of a gated ReLU activation in the encoder. This separates the encoder into two pathways: a ‘gating’ path which determines which features to activate (applying an L1 penalty here to encourage sparsity), and a ‘magnitude’ path which estimates the magnitude of those activated features. Weight sharing between these paths reduces the parameter count, improving efficiency. This design effectively mitigates the shrinkage bias inherent in standard SAEs, allowing for more faithful reconstructions at a given level of sparsity. By isolating the L1 penalty to feature selection, Gated SAEs achieve a Pareto improvement over baseline methods, demonstrating better reconstruction fidelity for any given level of sparsity while also addressing shrinkage.

Pareto Frontier Gains#

The concept of “Pareto Frontier Gains” in the context of a research paper likely refers to improvements achieved in a multi-objective optimization problem. A Pareto improvement means enhancing one aspect without worsening any other. In this scenario, the paper likely demonstrates that a proposed method (e.g., a novel algorithm or model) provides a better trade-off between two or more competing objectives. For instance, the paper may show superior performance on metrics like reconstruction accuracy and sparsity simultaneously, exceeding the capabilities of previous methods. This means the new approach dominates existing techniques, achieving a superior balance of performance characteristics along the Pareto frontier. The gains are significant because they represent a true improvement, not merely a compromise in one aspect to enhance the other. Such findings signify a notable contribution to the research field, highlighting the practicality and efficiency of the proposed methodology. Further investigation might reveal the underlying reasons for the improvement, such as how architectural choices or algorithmic enhancements lead to this superior performance.

Shrinkage Mitigation#

The concept of ‘shrinkage mitigation’ in the context of sparse autoencoders (SAEs) for interpreting language models addresses a critical limitation of standard SAE training. The L1 penalty, while promoting sparsity, causes a systematic underestimation of feature activations, a phenomenon known as shrinkage. This leads to less accurate reconstructions and potentially hinders the interpretability of learned features. Gated SAEs offer a solution by separating the feature selection process (determining which features are active) from the estimation of their magnitudes. By applying the L1 penalty only to the gating mechanism, Gated SAEs effectively limit its undesirable side effects. The decoupling enables more precise feature representation, resulting in improved reconstruction fidelity at a given sparsity level and reduced shrinkage. This is demonstrated through experiments showing that Gated SAEs produce sparser decompositions with comparable or even better interpretability than baseline SAEs, while achieving higher reconstruction accuracy.

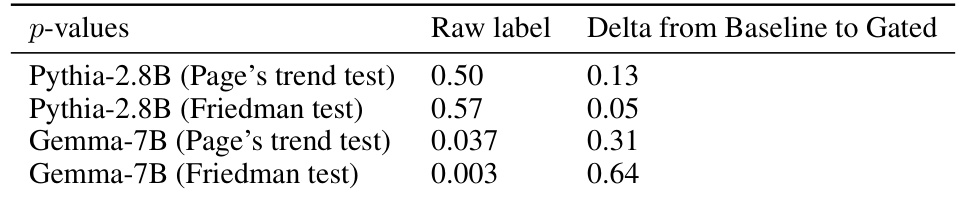

Interpretability Study#

This paper explores the mechanistic interpretability of large language models (LLMs) by employing sparse autoencoders (SAEs). A key aspect is the introduction of Gated SAEs, designed to mitigate biases inherent in traditional SAEs, specifically addressing the issue of shrinkage. The interpretability study, while not explicitly detailed in the provided text, likely involves a qualitative assessment and comparison of feature directions identified by both Gated and standard SAEs. This might include human evaluation of features (double-blind study), quantitative metrics comparing reconstruction fidelity and sparsity, and possibly visualizations to aid in understanding their semantic meaning. The results suggest that Gated SAEs offer Pareto improvements, meaning they achieve better reconstruction accuracy at equivalent sparsity levels compared to standard SAEs. This improvement indicates a greater ability to isolate interpretable directions within the high-dimensional activation spaces of LLMs. Importantly, while the study shows comparable interpretability between Gated and baseline SAEs, it underscores the value of a more robust methodology to precisely quantify and objectively assess the interpretability of the generated features. Ultimately, a strong focus on addressing the inherent biases in SAE training is essential for advancing mechanistic interpretability research.

Ablation Analysis#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model or system to assess their individual contributions. In the context of the provided research paper, an ablation analysis concerning Gated Sparse Autoencoders would likely involve removing key architectural features or training methodologies to determine their impact on performance. Removing the gating mechanism would show if the separation of feature detection and magnitude estimation is crucial for improved sparsity and reconstruction fidelity. Removing weight tying would evaluate the trade-off between computational efficiency and performance. Similarly, removing the auxiliary loss function or the sparsity-inducing L1 penalty would isolate their individual effects on shrinkage and overall performance. The results would be compared to the full Gated SAE model to quantify the impact of each removed component, ideally demonstrating a Pareto improvement offered by the complete Gated SAE architecture. The analysis should conclude by identifying which features contribute most significantly to the observed improvements over baseline models, and provide a strong mechanistic interpretation of how Gated SAEs work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

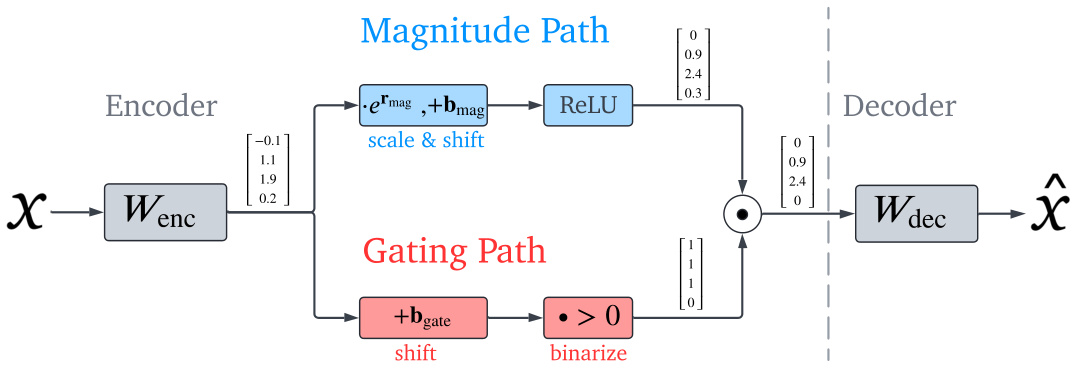

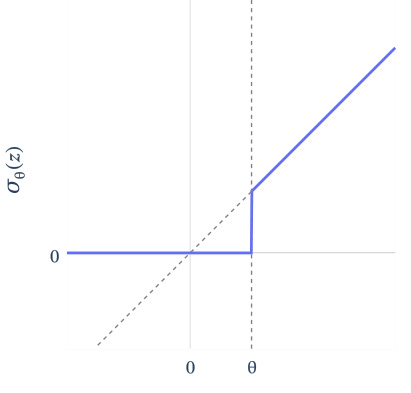

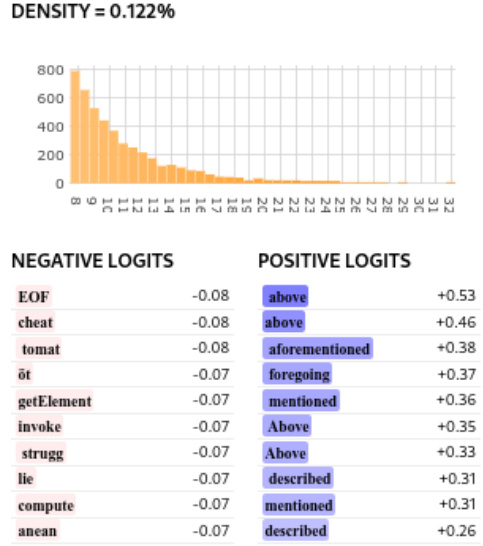

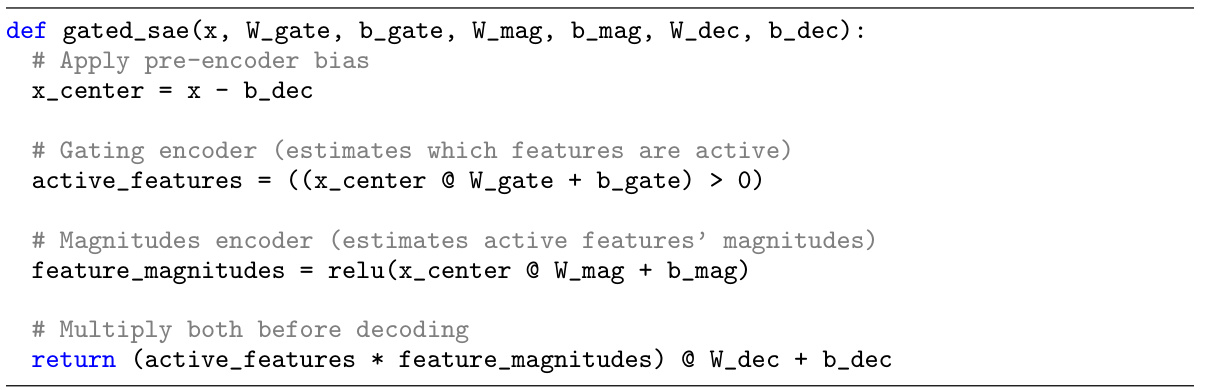

This figure shows the architecture of the Gated Sparse Autoencoder (Gated SAE). It illustrates how the input activation (x) is processed through two separate paths: a gating path and a magnitude path. The gating path determines which features are active using a linear transformation and a >0 threshold, producing a binary vector indicating active features. The magnitude path estimates the magnitudes of the active features using a linear transformation followed by a ReLU activation function. Crucially, the two paths share weights (Wenc), reducing the model’s parameter count. The output of the magnitude path, scaled by the gating path, is then fed into a decoder (Wdec) to reconstruct the original input (x̂). This design aims to overcome the shrinkage bias associated with traditional SAEs by decoupling feature activation from feature magnitude estimation.

This figure compares the performance of Gated SAEs and baseline SAEs in terms of reconstruction fidelity and sparsity. It shows that Gated SAEs consistently achieve better reconstruction fidelity (higher values on the y-axis) at any given level of sparsity (lower values on the x-axis), indicating a Pareto improvement. The experiment was conducted on layer 20 of the Gemma-7B language model, with Gated SAEs using dictionaries of size 217 (approximately 131k) and baseline SAEs using dictionaries 50% larger. Despite this size difference, both SAE types were trained with equal compute. The Pareto improvement observed holds across different layers and in other language models (GELU-1L and Pythia-2.8B), as detailed in Appendix E.

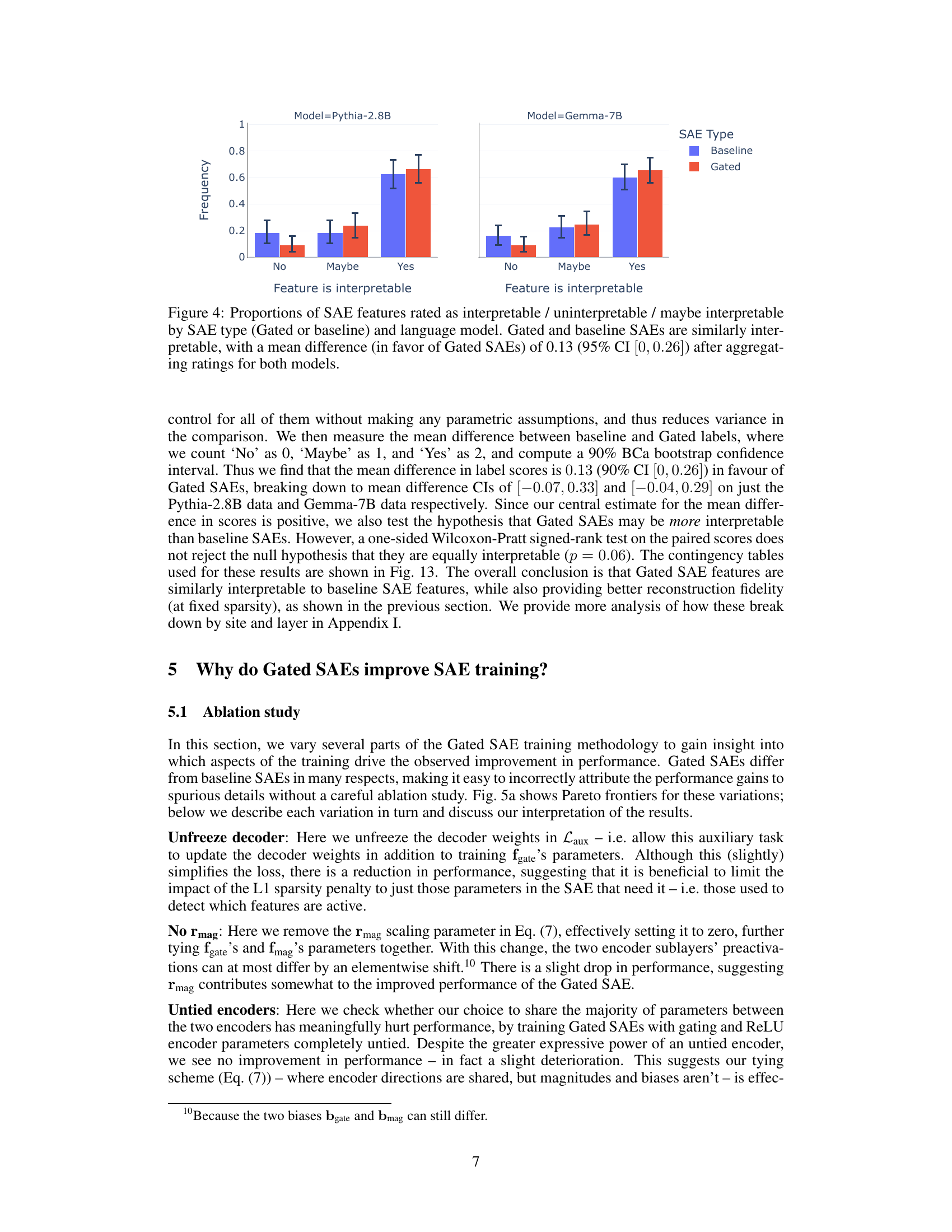

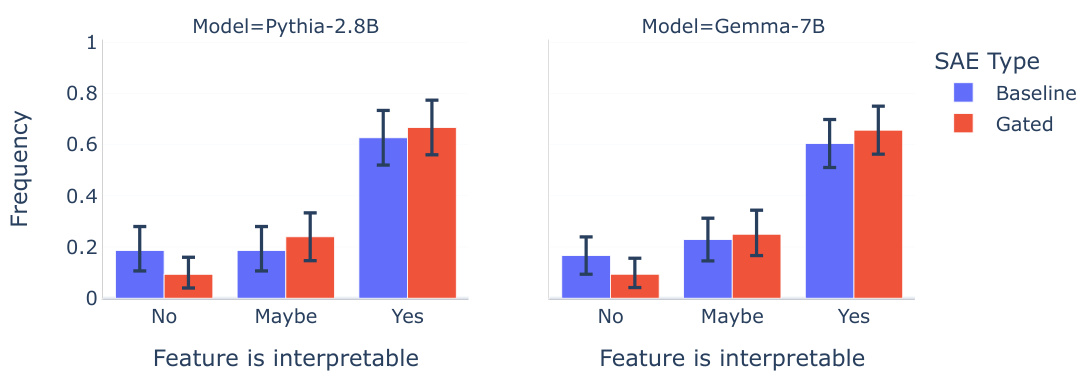

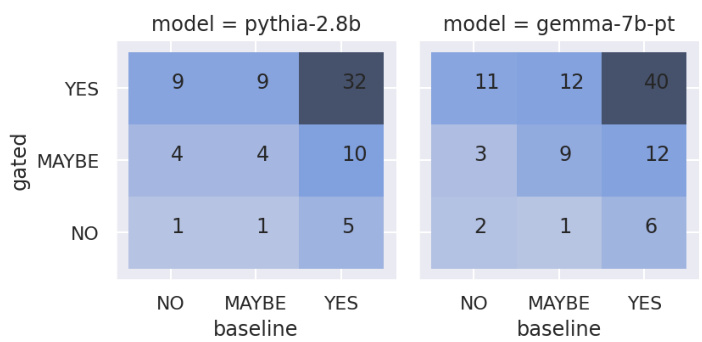

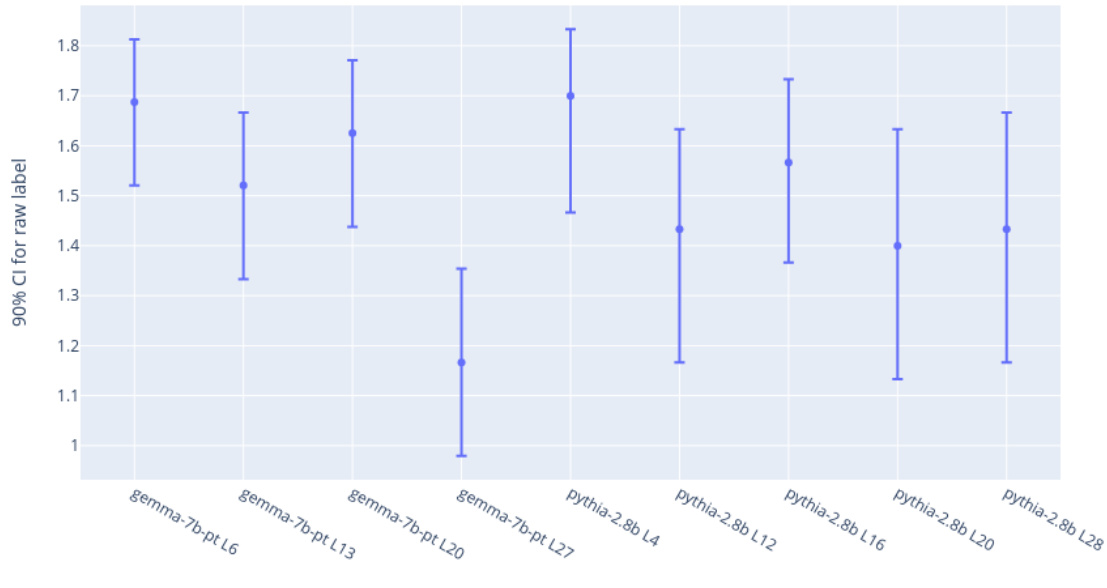

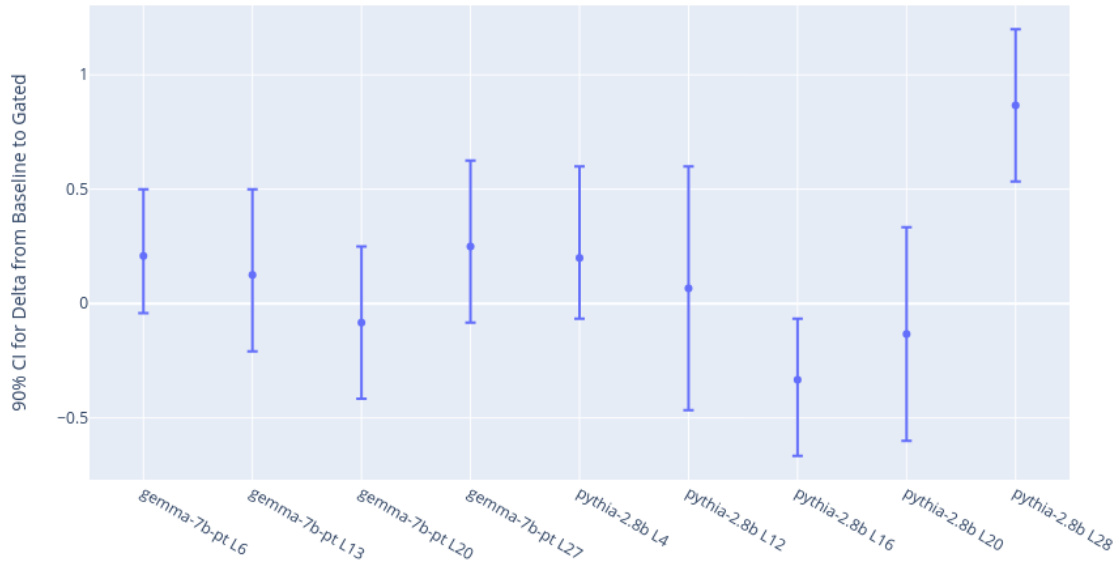

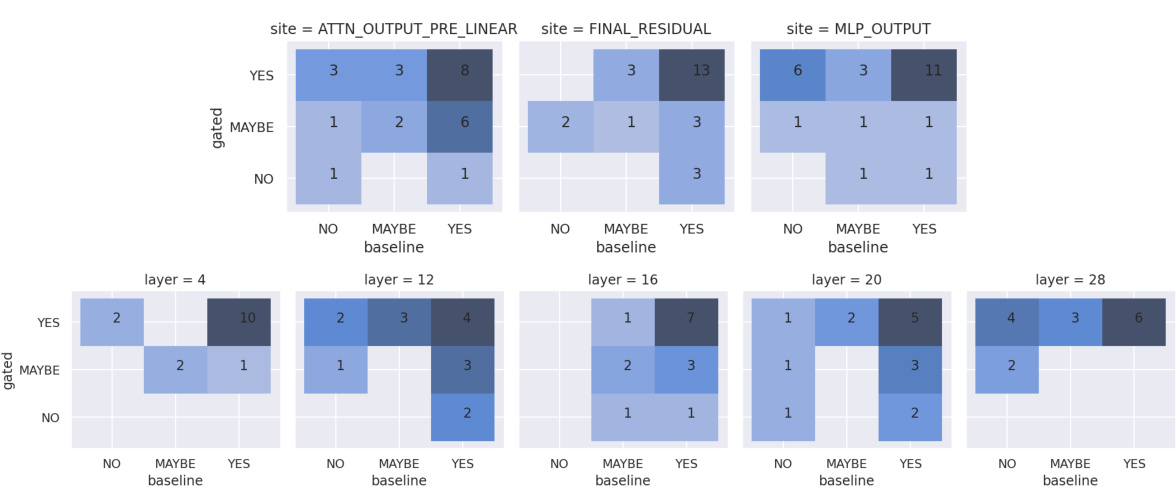

This figure presents the results of a double-blind human interpretability study comparing Gated SAEs and baseline SAEs. Raters assessed the interpretability of randomly selected features from both SAE types trained on two different language models (Pythia-2.8B and Gemma-7B). The figure shows the distribution of interpretability ratings (‘No’, ‘Maybe’, ‘Yes’) for each SAE type, for both models. The key takeaway is that, statistically speaking, there is no significant difference in the interpretability of features between Gated SAEs and baseline SAEs. Although Gated SAEs demonstrate a slight advantage, the confidence interval overlaps zero.

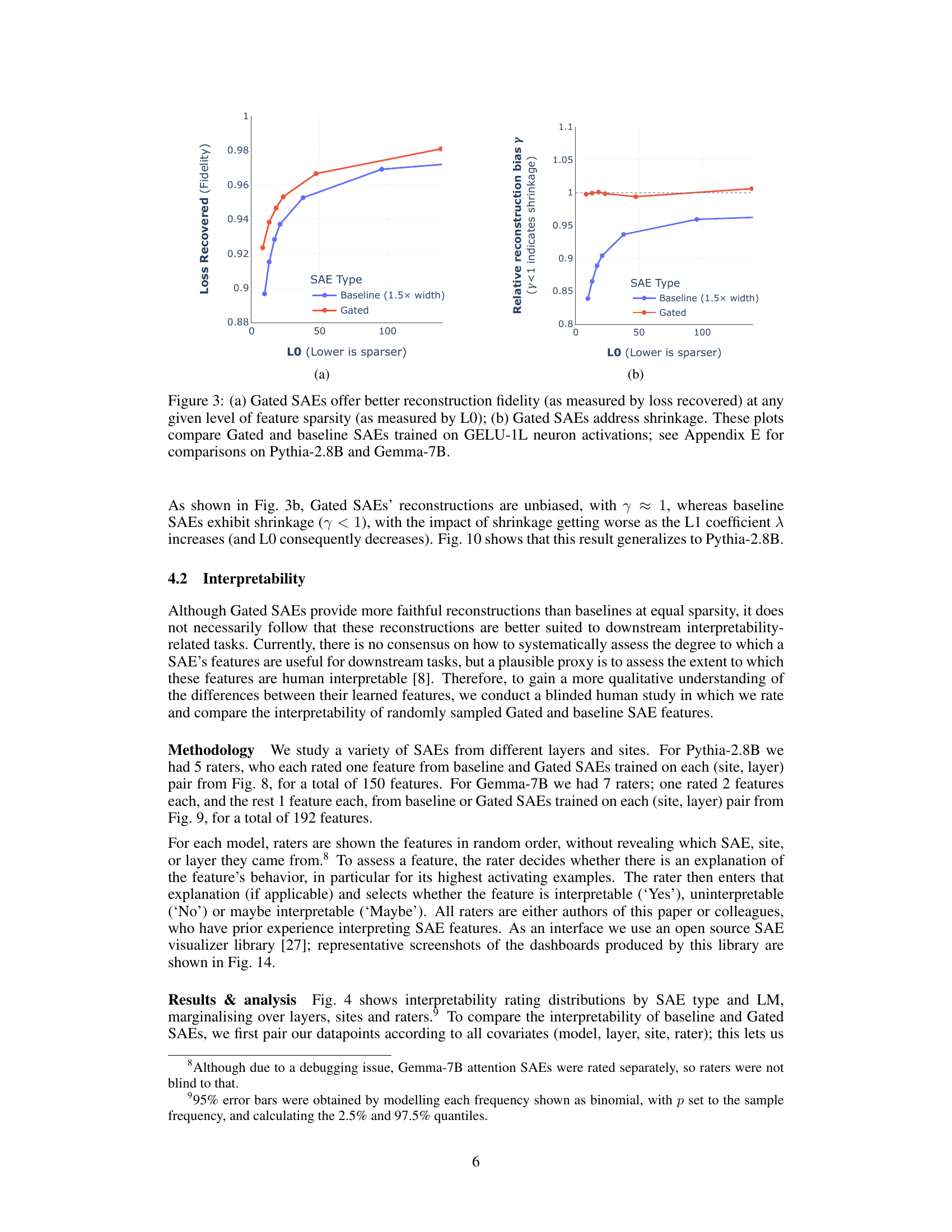

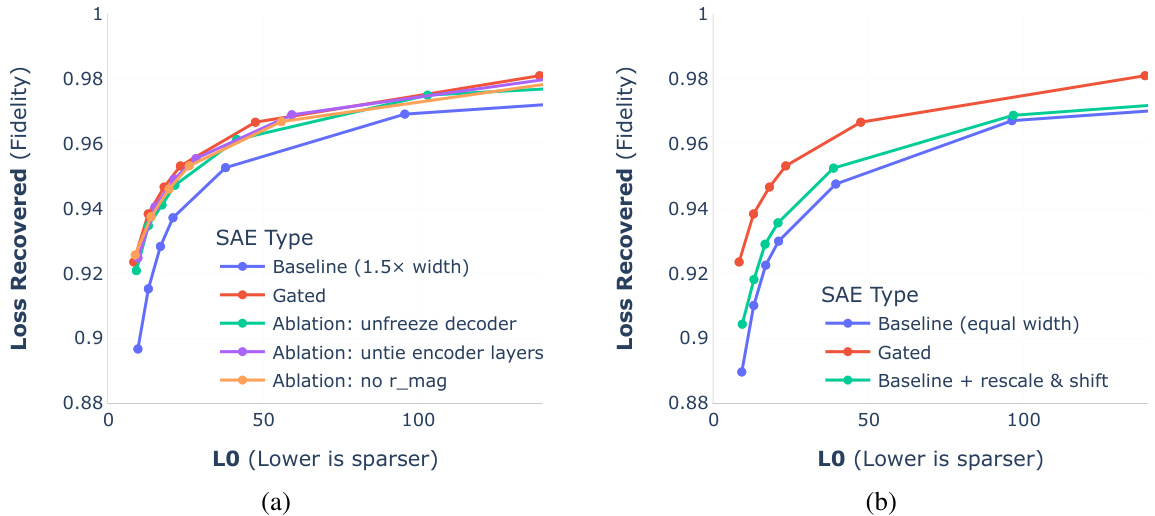

This figure presents the ablation study results for the Gated SAE model. The left panel (a) shows the Pareto frontiers for different variations of the Gated SAE training process, demonstrating the importance of specific aspects of the model and its training in achieving better performance. The right panel (b) further investigates the performance improvement by comparing the Gated SAE to an alternative approach that also resolves shrinkage but does so by only adjusting feature magnitudes. This analysis reveals that the improvements of the Gated SAE extend beyond merely addressing shrinkage, suggesting that other factors such as learning better encoder and decoder directions also contribute to its enhanced performance.

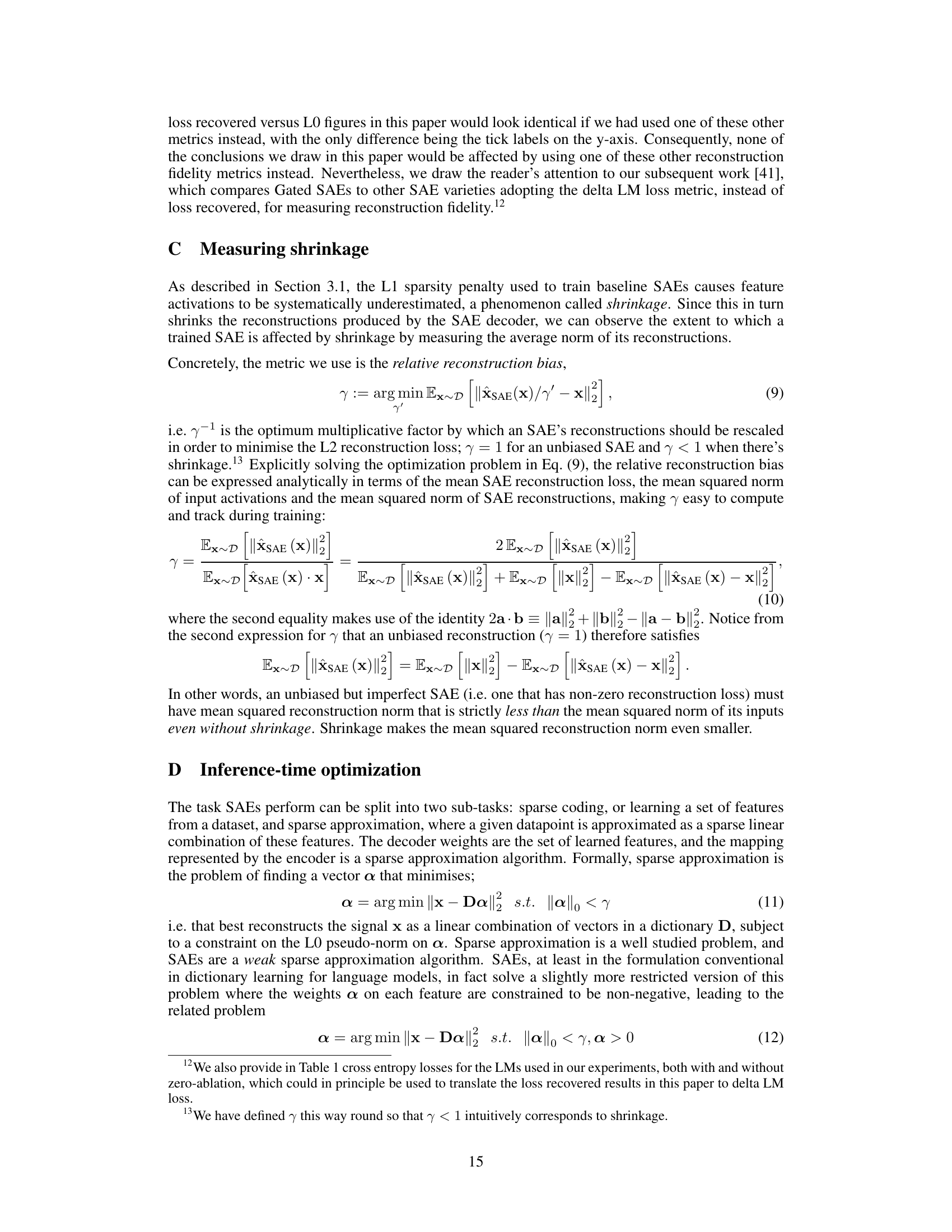

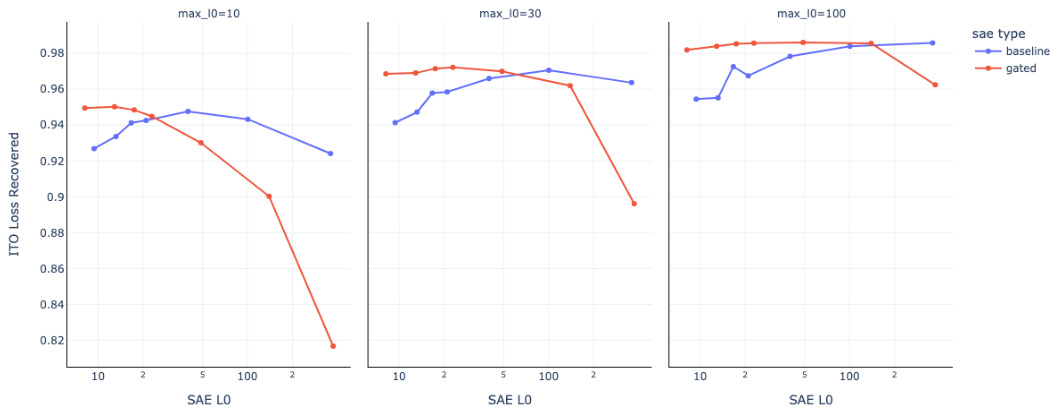

This figure compares the performance of baseline and gated SAEs when using an Iterative Thresholding Optimization (ITO) algorithm at inference time for different target sparsity levels. It shows that Gated SAEs trained with lower target sparsity levels consistently produce better dictionaries than baseline SAEs, as measured by loss recovered. Interestingly, the best-performing baseline SAE frequently has a higher test-time sparsity than the target sparsity, suggesting potential sensitivity of the L0 sparsity metric to noise, especially in standard SAE architectures where features with very low activation are common.

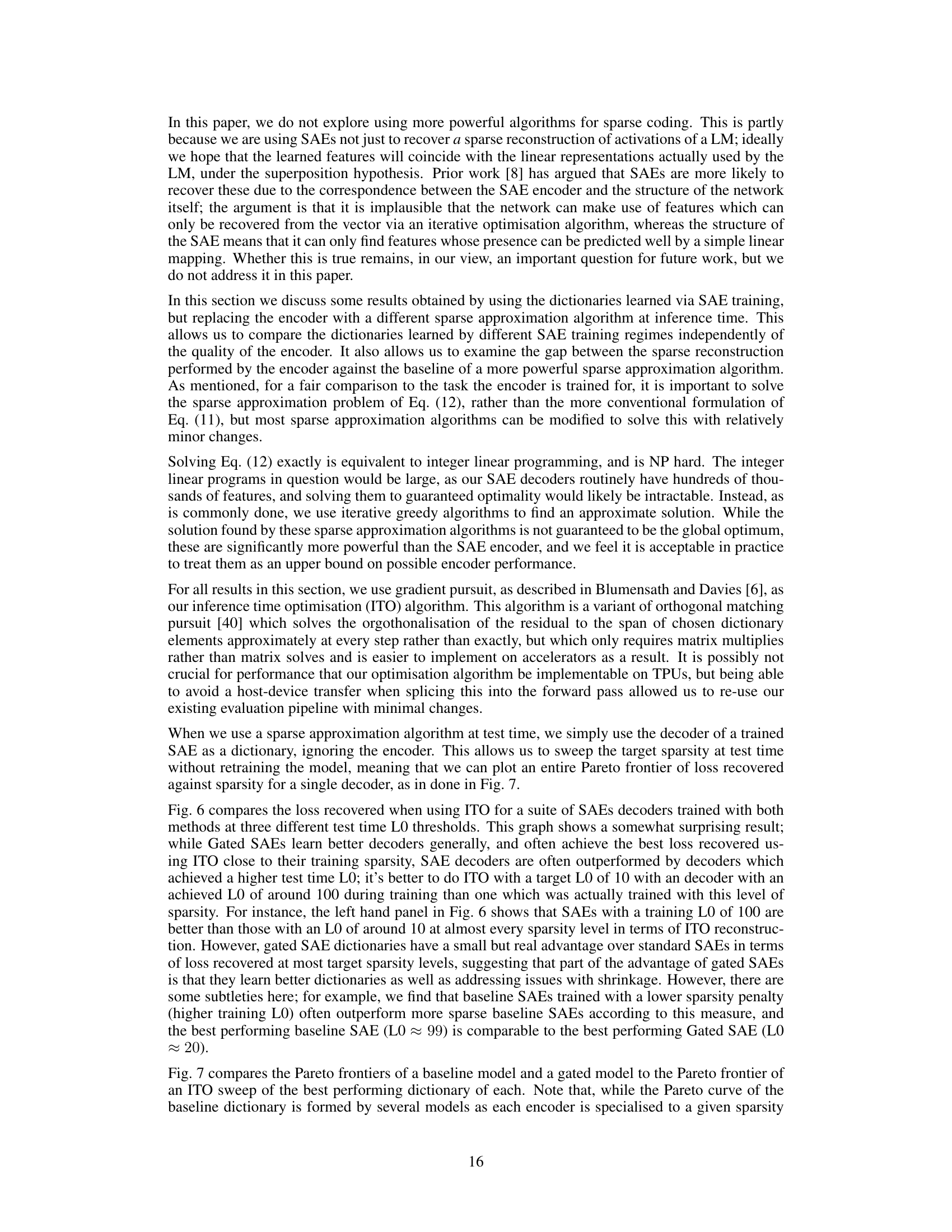

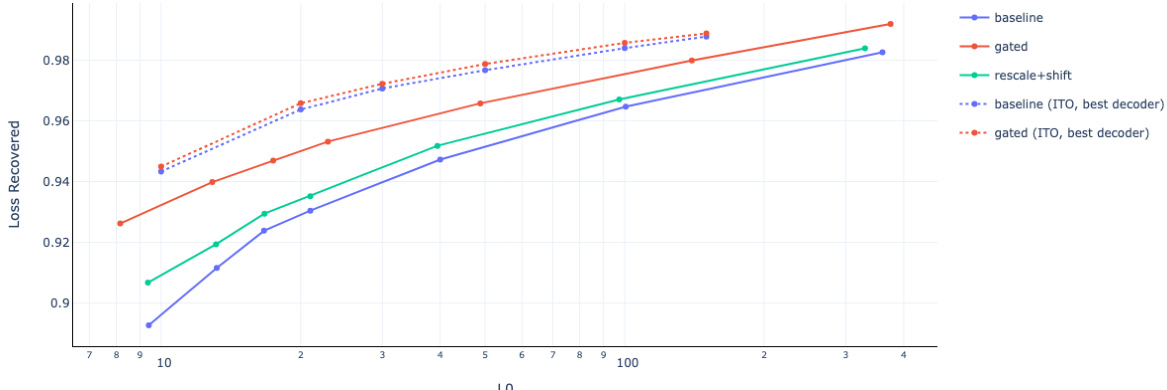

This figure compares the performance of baseline SAEs, gated SAEs and baseline SAEs with learned rescale and shift in terms of the Pareto frontier of loss recovered vs L0 at different target sparsities. The Pareto frontier represents the trade-off between reconstruction fidelity and sparsity. Gated SAEs consistently outperform baseline SAEs and the baseline SAEs with learned rescale and shift, demonstrating their effectiveness in achieving better reconstruction fidelity at a given sparsity level. Although the best-performing model with inference-time optimization (ITO) achieves slightly better results, the margin is minimal, showing that the gated SAE architecture’s advantage extends to ITO scenarios.

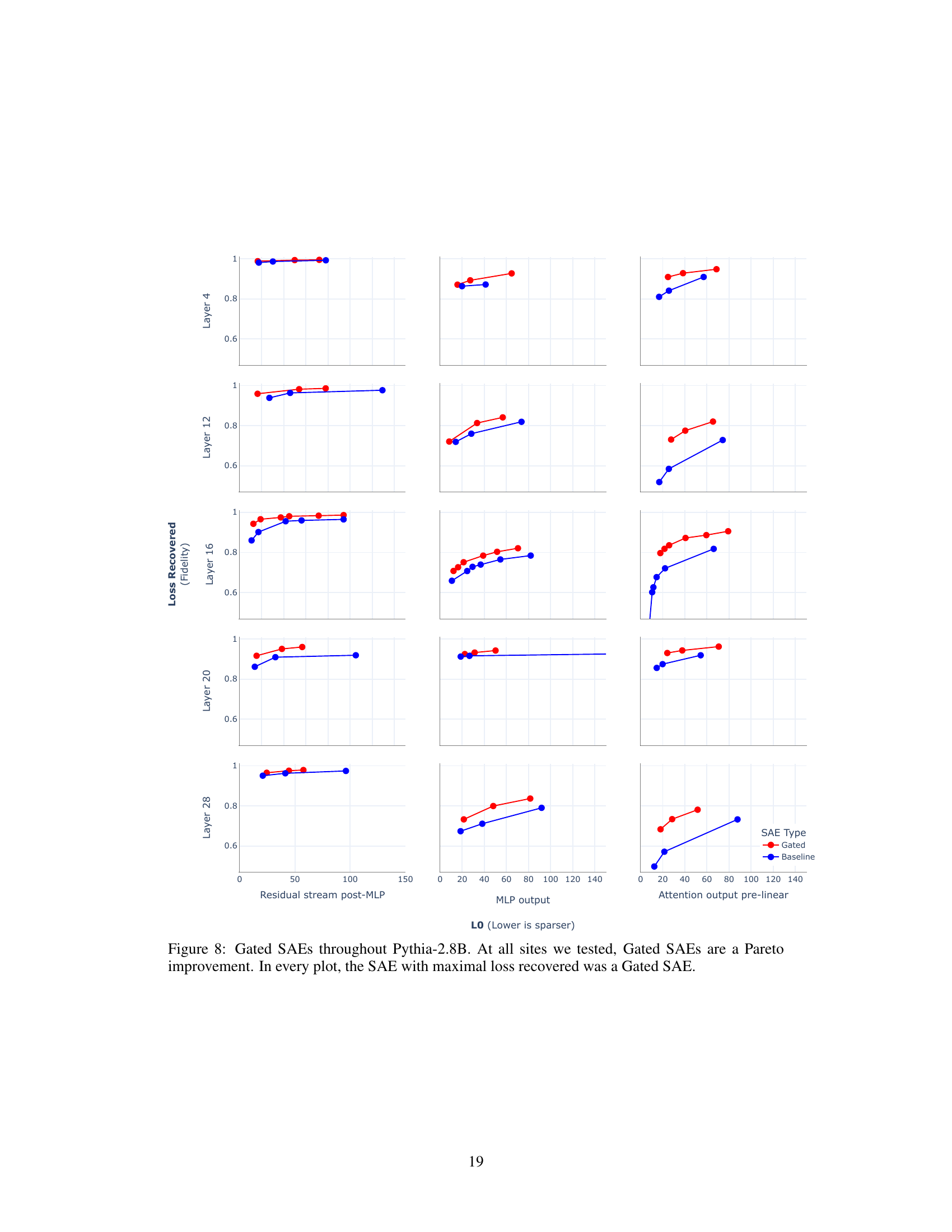

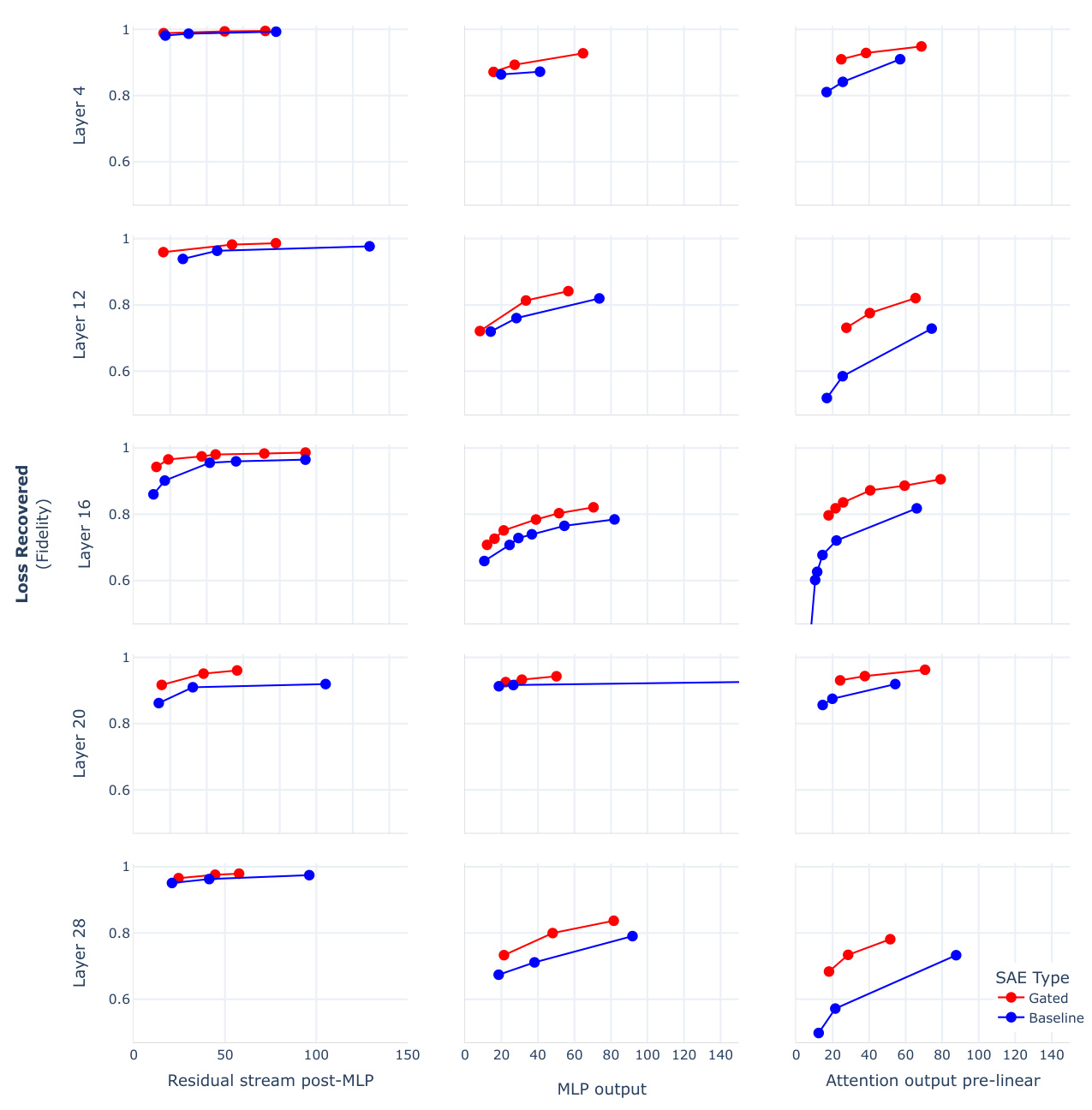

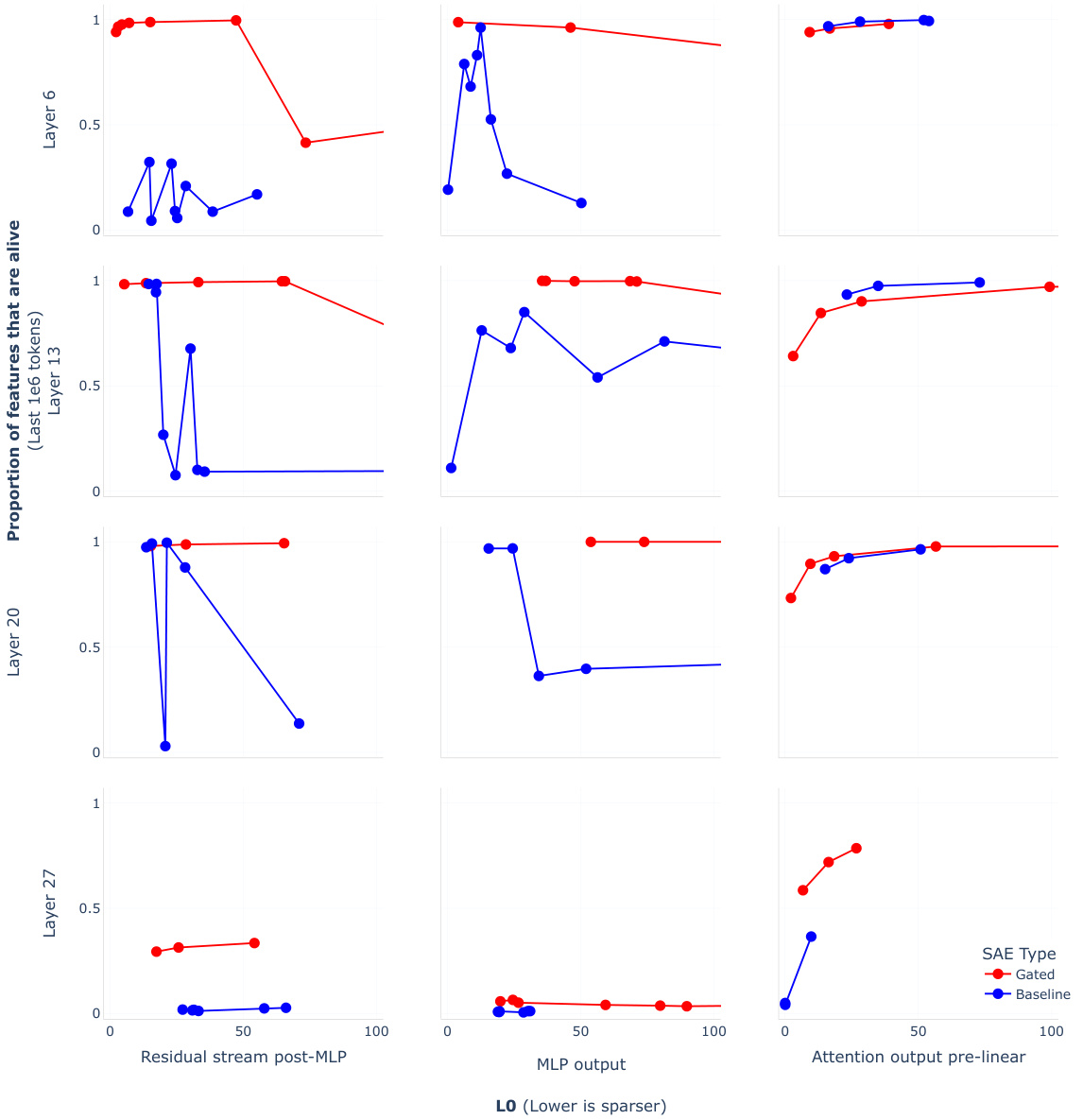

This figure compares the performance of Gated SAEs and baseline SAEs across different layers and sites within the Pythia-2.8B language model. The x-axis represents the sparsity (L0, lower is sparser), and the y-axis represents the reconstruction fidelity (Loss Recovered). Each subplot shows the results for a specific layer and site (MLP output, attention output pre-linear, and residual stream post-MLP). The plots demonstrate that Gated SAEs consistently outperform baseline SAEs, achieving higher reconstruction fidelity for the same level of sparsity. This Pareto improvement is observed across all layers and sites tested, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed Gated SAE architecture.

This figure compares the performance of Gated SAEs and baseline SAEs in terms of reconstruction fidelity and sparsity. The plots show that Gated SAEs consistently achieve better reconstruction fidelity (higher loss recovered) for a given level of sparsity (lower L0) compared to baseline SAEs. The experiment was conducted on Layer 20 of the Gemma-7B model. The dictionaries used in Gated SAEs were smaller than the baseline SAEs (size 217 ≈ 131k vs 50% larger), while both types were trained with the same computational resources. The same trend was observed in other models (GELU-1L and Pythia-2.8B) as well.

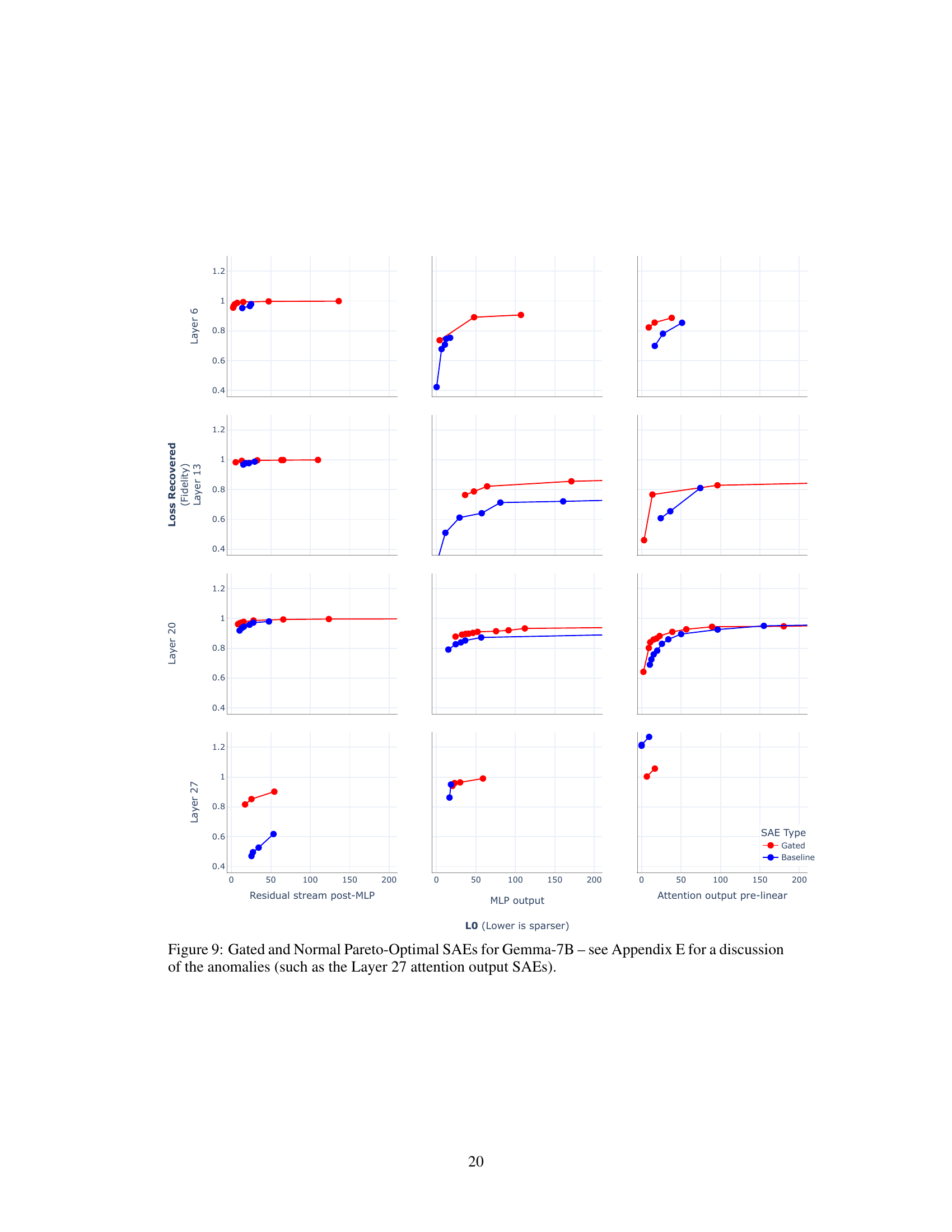

This figure compares the performance of Gated Sparse Autoencoders (Gated SAEs) and baseline SAEs in terms of reconstruction fidelity and sparsity. Three plots show the results for different input types (residual stream post-MLP, MLP output, attention output pre-linear) from layer 20 of the Gemma-7B language model. The Gated SAE consistently outperforms the baseline SAE, achieving higher reconstruction fidelity (lower loss) at the same level of sparsity (lower L0). The dictionaries used by the Gated SAE are smaller (217 ≈ 131k) than the baseline SAEs (50% larger), indicating better efficiency.

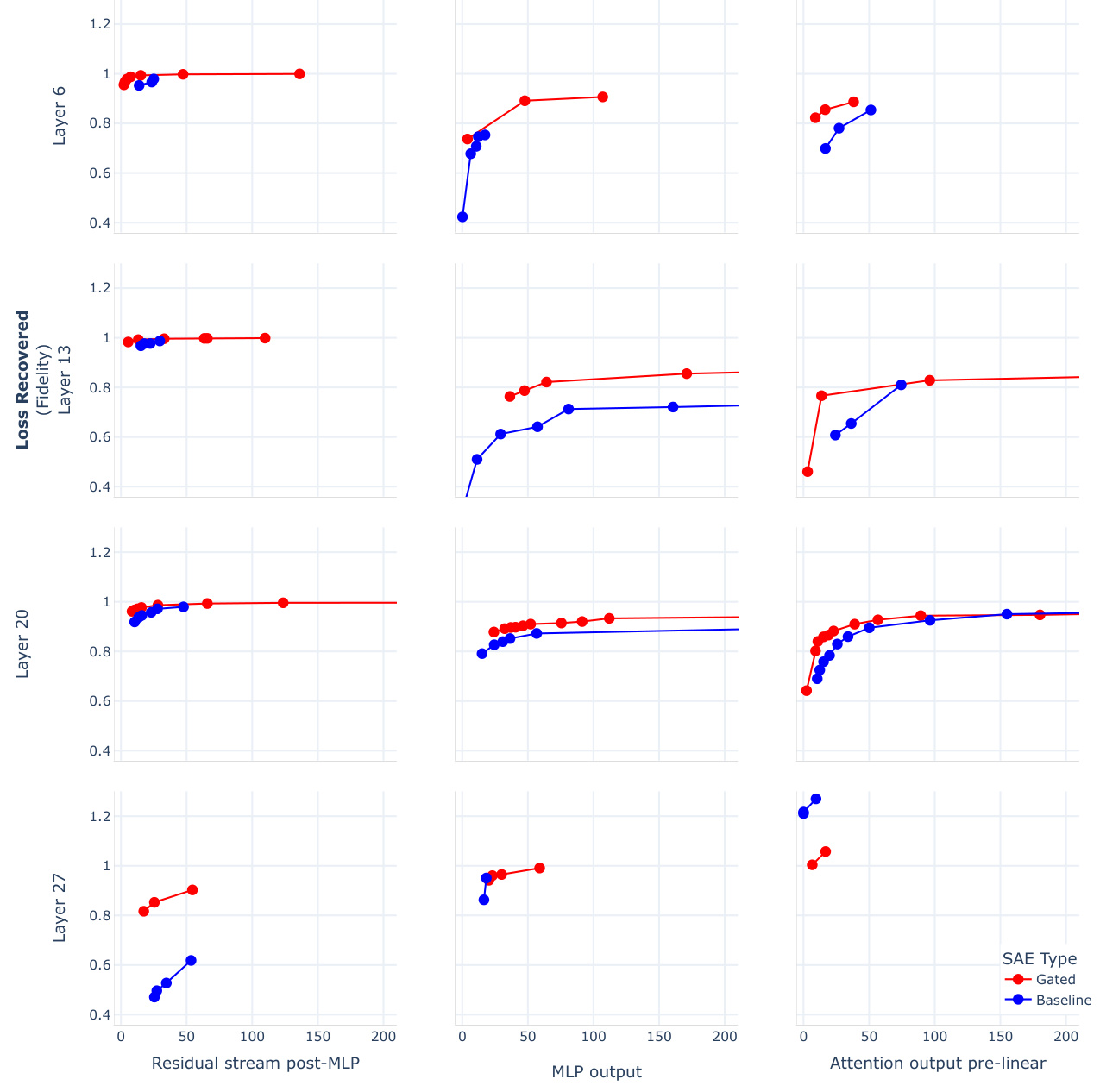

This figure compares the performance of Gated SAEs and baseline SAEs across various layers and sites (MLP output, attention output pre-linear, and residual stream post-MLP) within the Pythia-2.8B language model. The plots show the trade-off between sparsity (measured by L0, lower is sparser) and reconstruction fidelity (measured by loss recovered). Gated SAEs consistently outperform baseline SAEs, achieving better reconstruction fidelity at the same level of sparsity or lower sparsity for comparable fidelity. In all cases, the Gated SAE shows the highest reconstruction fidelity (loss recovered) among the SAEs.

This figure shows that with the weight sharing scheme applied in the paper, the gated encoder is mathematically equivalent to a linear layer with a specific non-standard activation function called JumpReLU. The graph displays the shape of this activation function which is a piecewise linear function with a discontinuity or a gap at theta.

The figure compares the performance of Gated Sparse Autoencoders (Gated SAEs) and baseline SAEs in terms of reconstruction fidelity and sparsity. Gated SAEs demonstrate improved reconstruction fidelity (how well the model reconstructs the original data) for a given level of sparsity (how many features are used in the reconstruction). This improvement is consistent across multiple layers of different language models (Gemma-7B, GELU-1L, Pythia-2.8B). The dictionaries used in Gated SAEs are smaller than those in baseline SAEs, demonstrating a Pareto improvement (better performance in both metrics).

This figure demonstrates the Pareto improvement of Gated SAEs over baseline SAEs in terms of reconstruction fidelity and sparsity. Three subplots show the results of training SAEs on different parts of a Gemma-7B language model, comparing the loss recovered (reconstruction fidelity) against L0 (sparsity) for Gated SAEs and baseline SAEs. The results reveal that Gated SAEs consistently achieve higher reconstruction fidelity at any given level of sparsity compared to baseline SAEs. The experiments were conducted ensuring both models used equal compute by adjusting the dictionary size, showing that the improvement is not due to an increase in parameters.

The figure displays the performance of Gated Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) against baseline SAEs across different sparsity levels. It shows that Gated SAEs achieve better reconstruction fidelity (higher loss recovered) for any given sparsity level (lower LO) compared to baseline SAEs. The experiment was conducted on Layer 20 of the Gemma-7B language model, and the findings are consistent across other models (GELU-1L, Pythia-2.8B), as detailed in Appendix E. The dictionary size of Gated SAEs was approximately 131k, while the baseline SAEs had dictionaries 50% larger, ensuring fair comparison in computational resources.

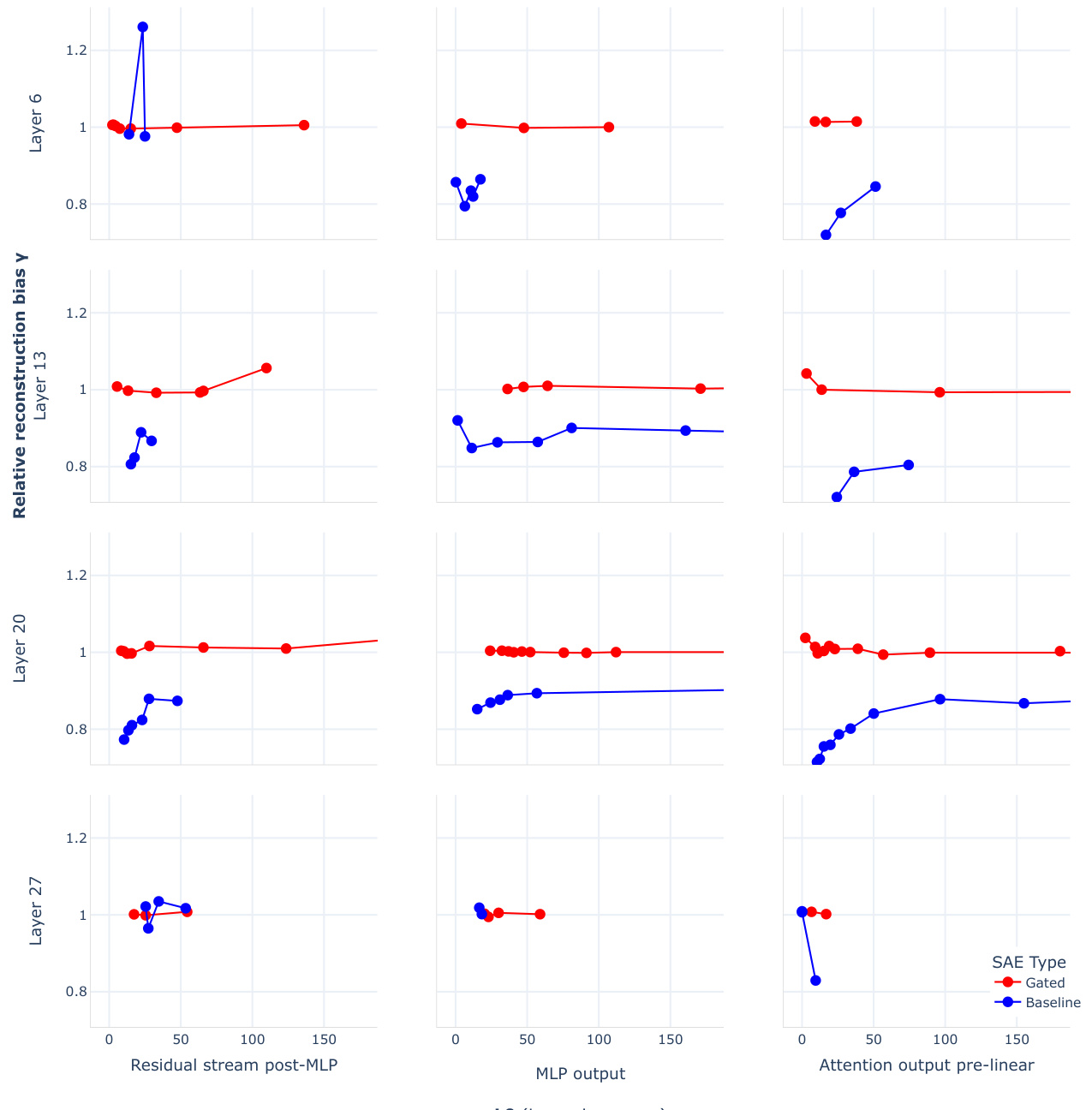

This figure shows the relative reconstruction bias (y) for Gated SAEs and baseline SAEs across different layers and sites in the Pythia-2.8B model. The relative reconstruction bias is a metric that measures the extent to which the reconstructions produced by a SAE are systematically underestimated. A value of y=1 indicates unbiased reconstructions, while values of y<1 indicate shrinkage. The plots show that Gated SAEs largely resolve shrinkage, obtaining values of y close to 1 across different layers and sites, even at high sparsity levels. In contrast, baseline SAEs show significant shrinkage, especially at high sparsity levels, as indicated by their y values well below 1. The plots highlight a key advantage of Gated SAEs over baseline SAEs: Gated SAEs effectively mitigate the bias of shrinkage introduced by the L1 sparsity penalty, allowing them to achieve more faithful reconstructions at the same sparsity levels.

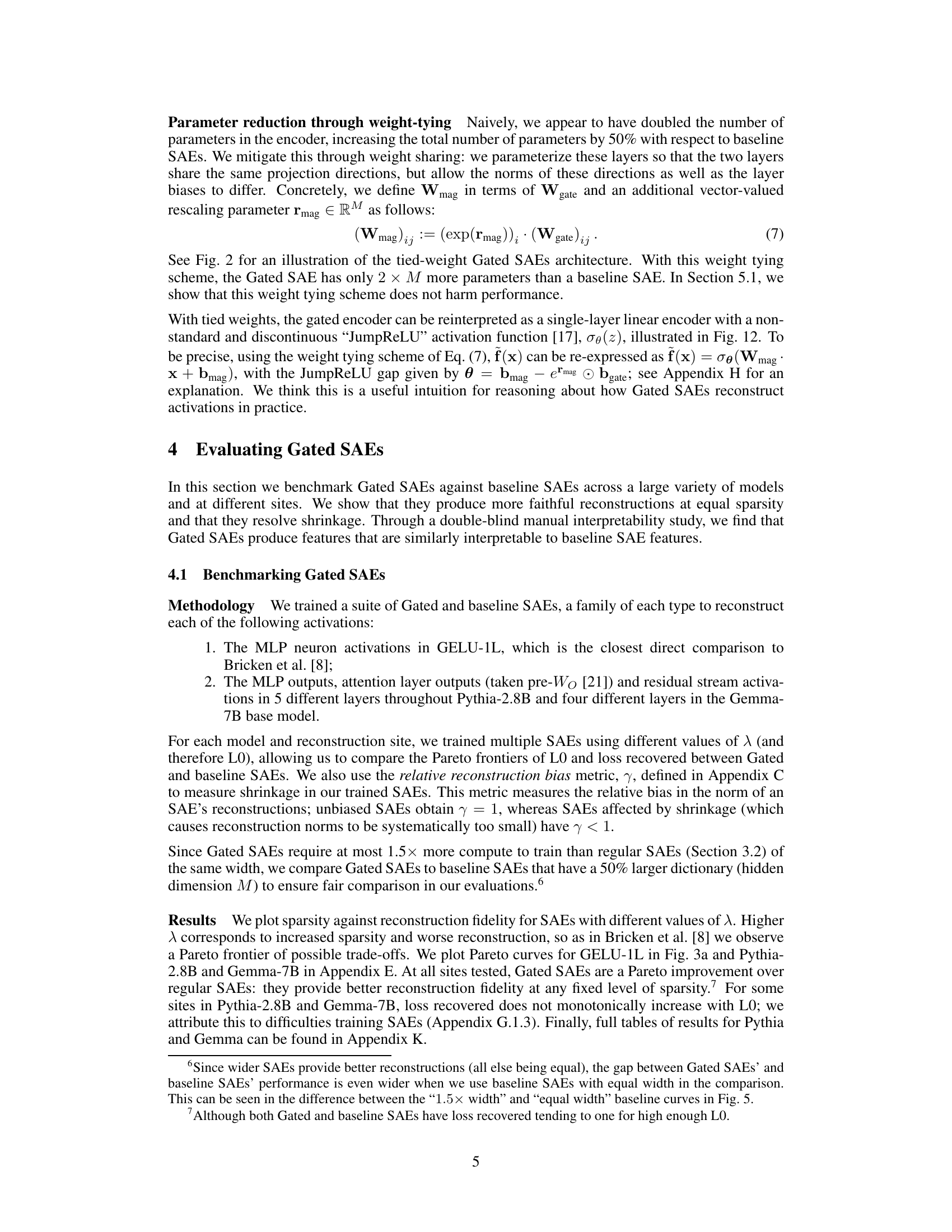

This figure shows two plots comparing the performance of Gated SAEs and baseline SAEs in terms of reconstruction fidelity (loss recovered) and sparsity (L0). The left plot (a) demonstrates that Gated SAEs achieve better reconstruction fidelity for any given level of sparsity, showing a Pareto improvement. The right plot (b) shows that Gated SAEs resolve the shrinkage bias observed in baseline SAEs, meaning that they don’t systematically underestimate feature activations. The results shown are for GELU-1L neuron activations, but similar results are shown in Appendix E for Pythia-2.8B and Gemma-7B.

This figure presents two plots visualizing the performance of Gated SAEs against baseline SAEs in terms of reconstruction fidelity and sparsity. Plot (a) shows that Gated SAEs achieve better reconstruction fidelity for any given level of sparsity (lower L0 means sparser). Plot (b) demonstrates that Gated SAEs mitigate the ‘shrinkage’ issue, a bias found in baseline SAEs where the magnitude of feature activations is systematically underestimated. The plots use GELU-1L neuron activations for comparison, with Appendix E providing similar results for Pythia-2.8B and Gemma-7B.

This figure compares the performance of Gated Sparse Autoencoders (Gated SAEs) and baseline SAEs in terms of reconstruction fidelity and sparsity. Three plots show the results for different locations within a Gemma-7B language model. Gated SAEs consistently achieve better reconstruction fidelity (y-axis) at any given level of sparsity (x-axis), indicating a Pareto improvement. The dictionaries used in Gated SAEs are smaller than those in baseline SAEs (131k vs. 50% larger), yet they achieve comparable performance with the same compute resources. This consistent improvement across different layers and models is further discussed in Appendix E.

The figure shows the Pareto frontier for Gated and Baseline Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) trained on layer 20 of the Gemma-7B language model. The plots compare reconstruction fidelity (loss recovered) against sparsity (L0). Gated SAEs consistently show improved reconstruction fidelity at any given sparsity level compared to the baseline SAEs. The dictionaries used for the Gated SAEs are smaller (217 ≈ 131k parameters) than those used for the baseline SAEs, which are 50% larger; however, the training compute is equivalent. The Pareto improvement is consistent across multiple models (GELU-1L, Pythia-2.8B, Gemma-7B) and layers.

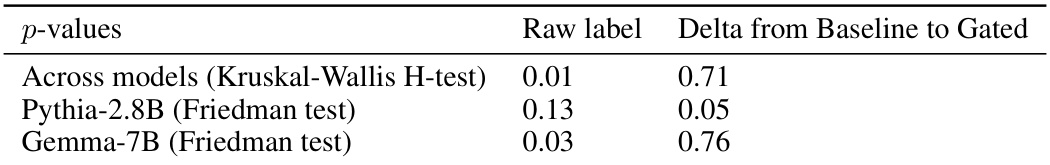

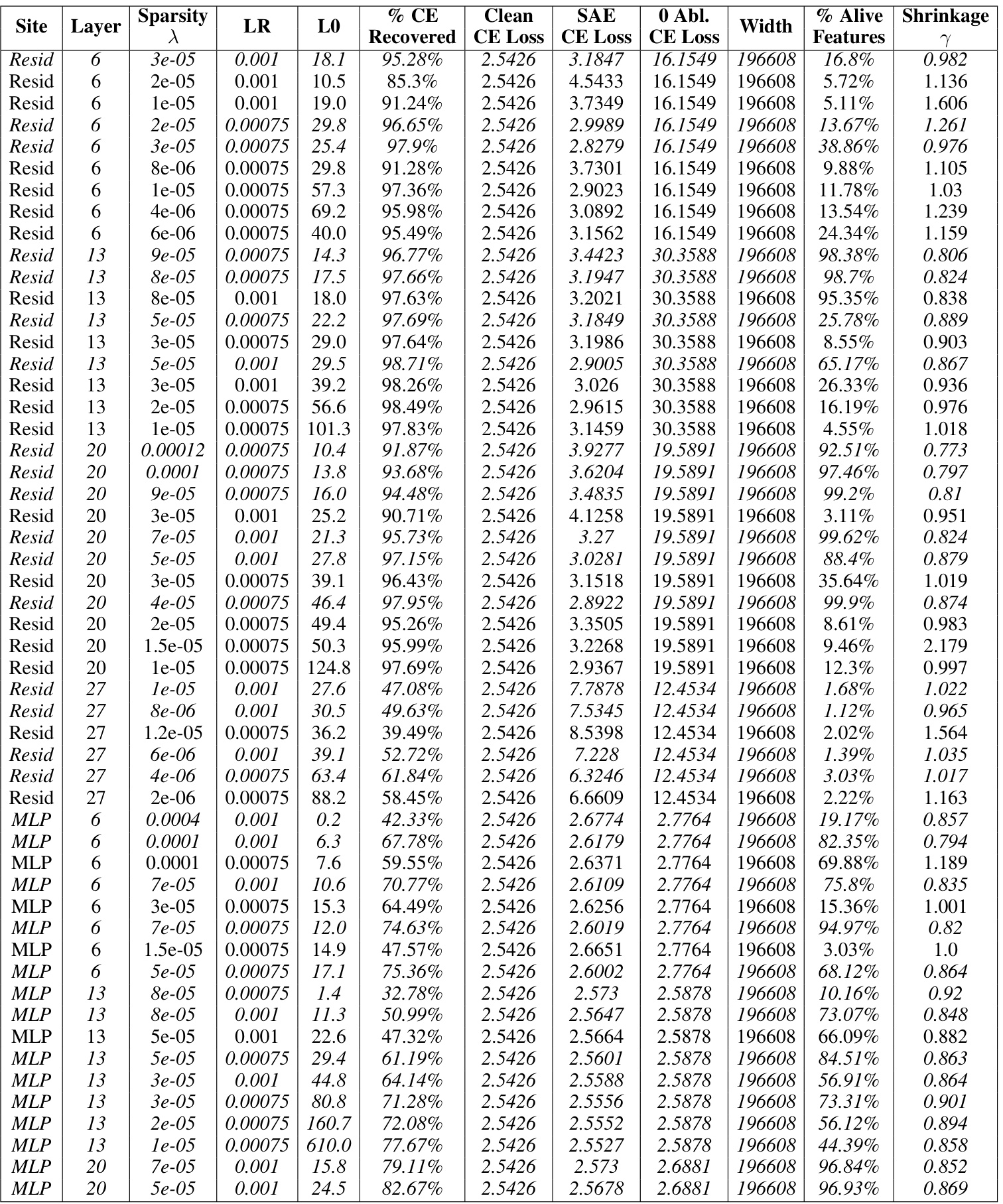

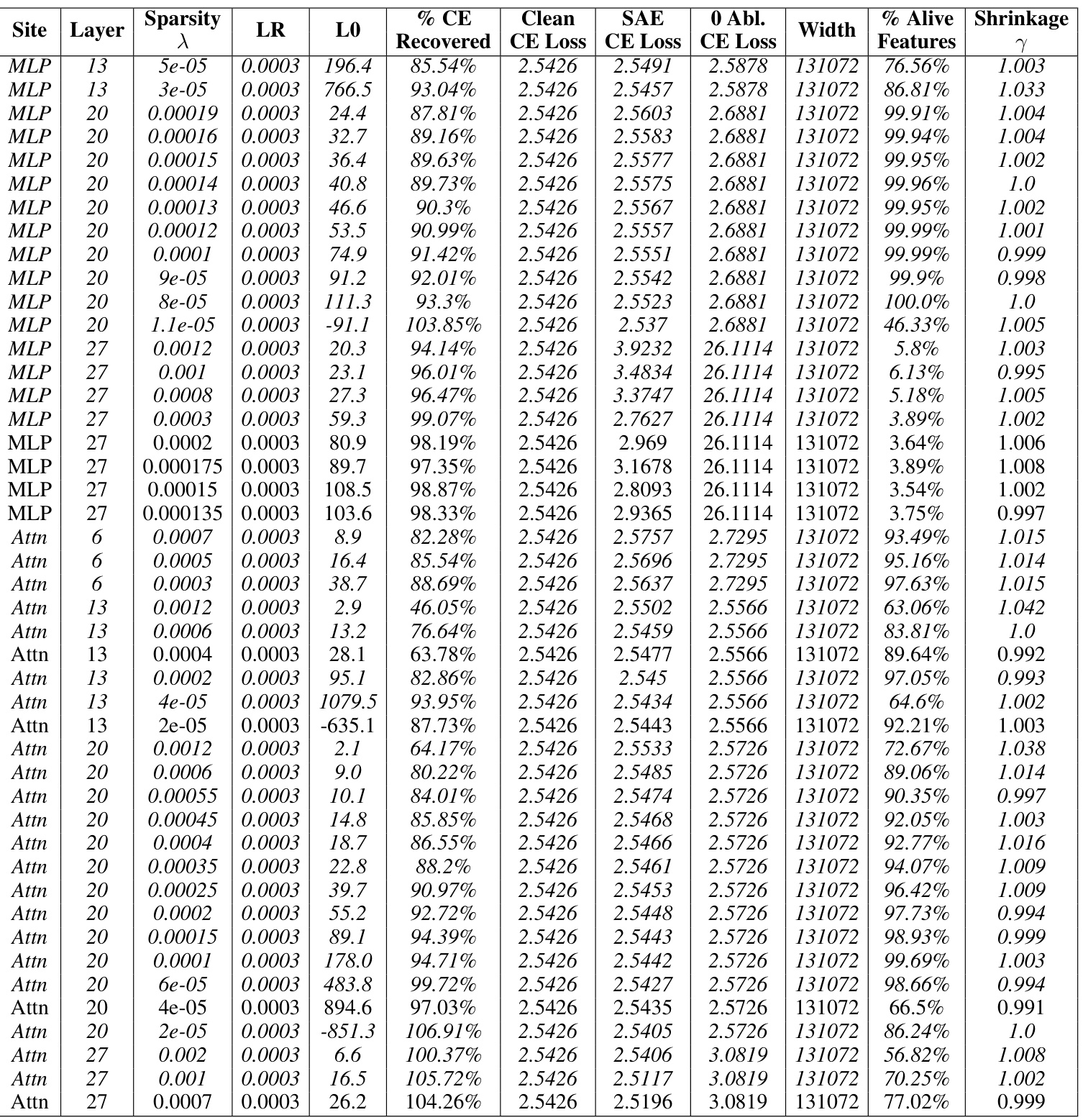

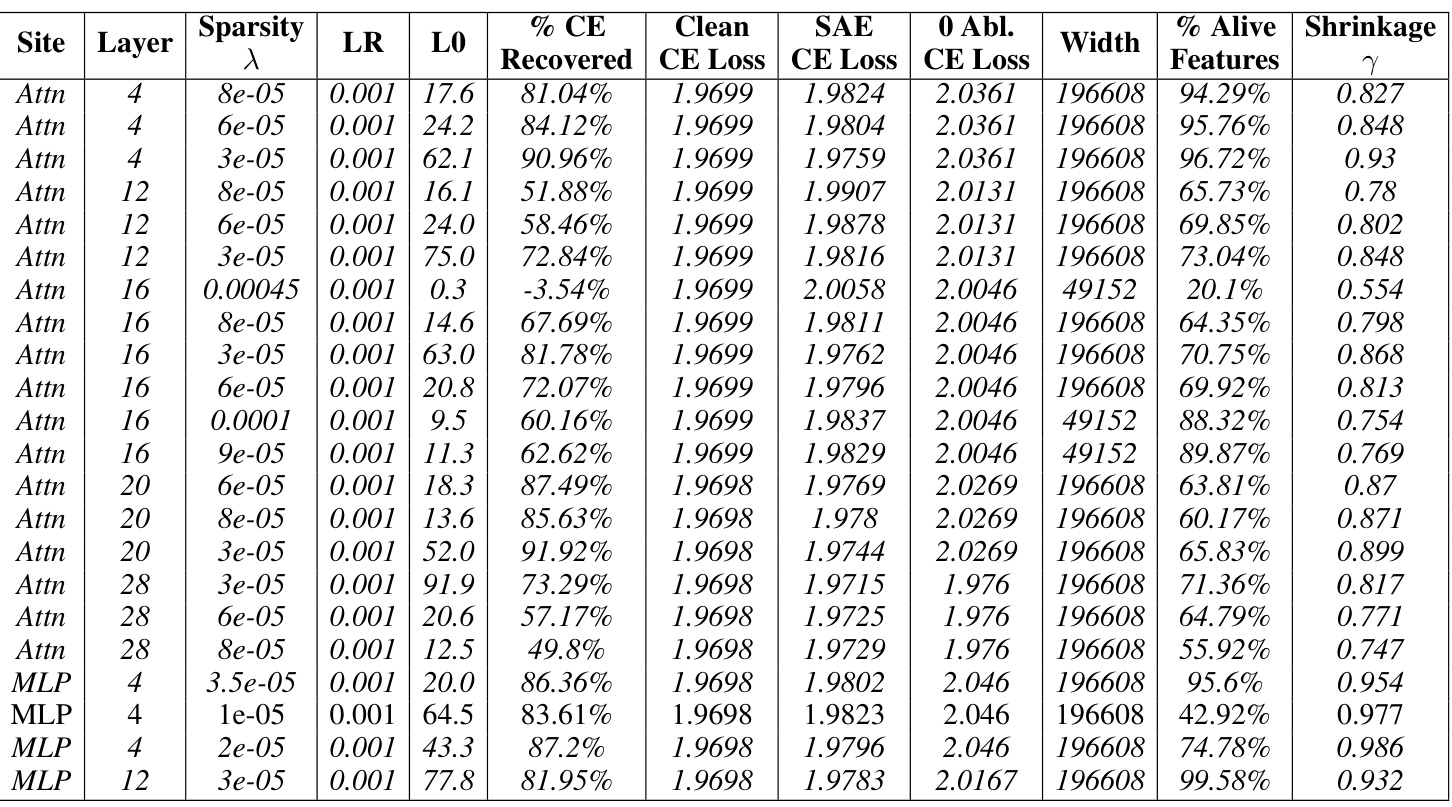

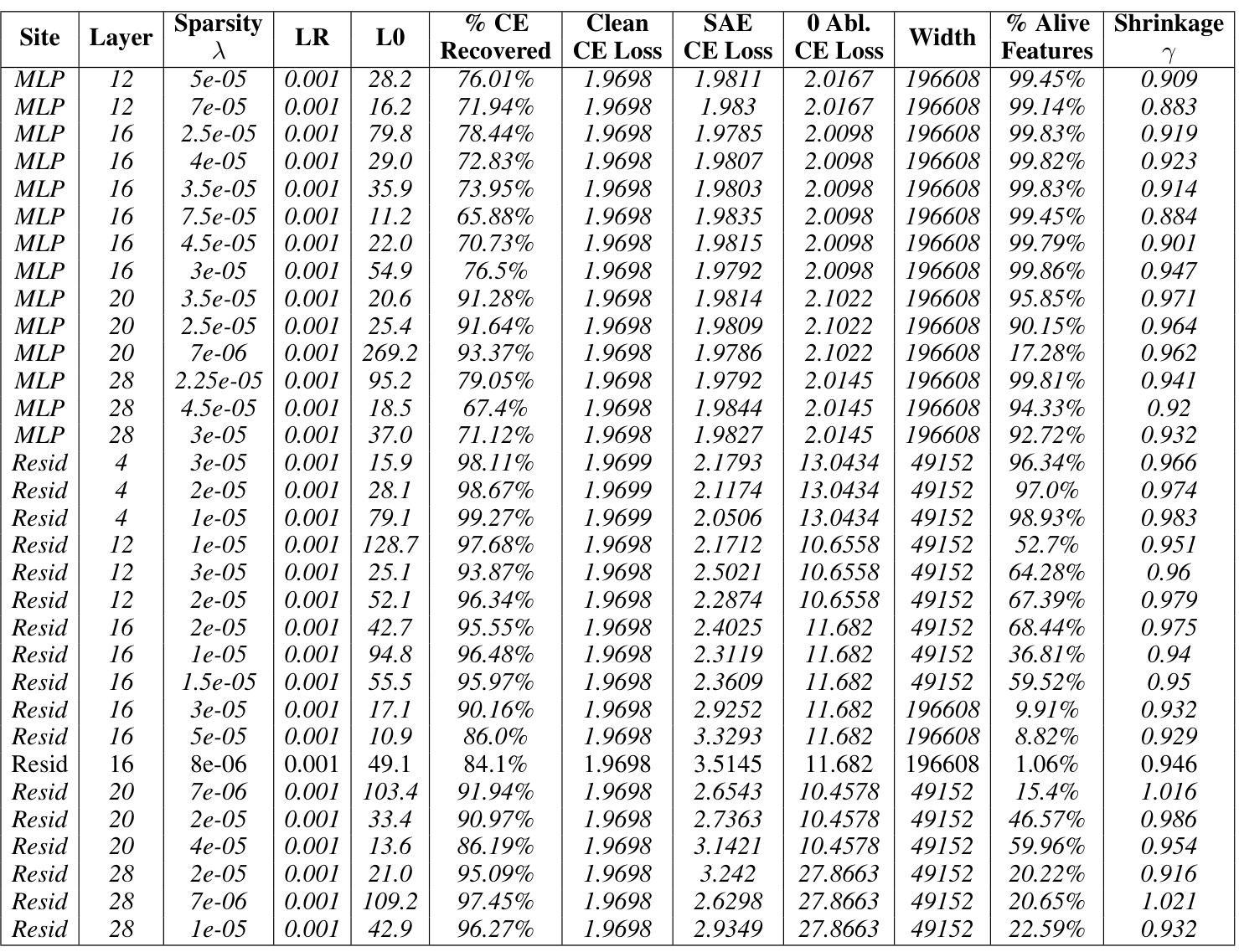

More on tables

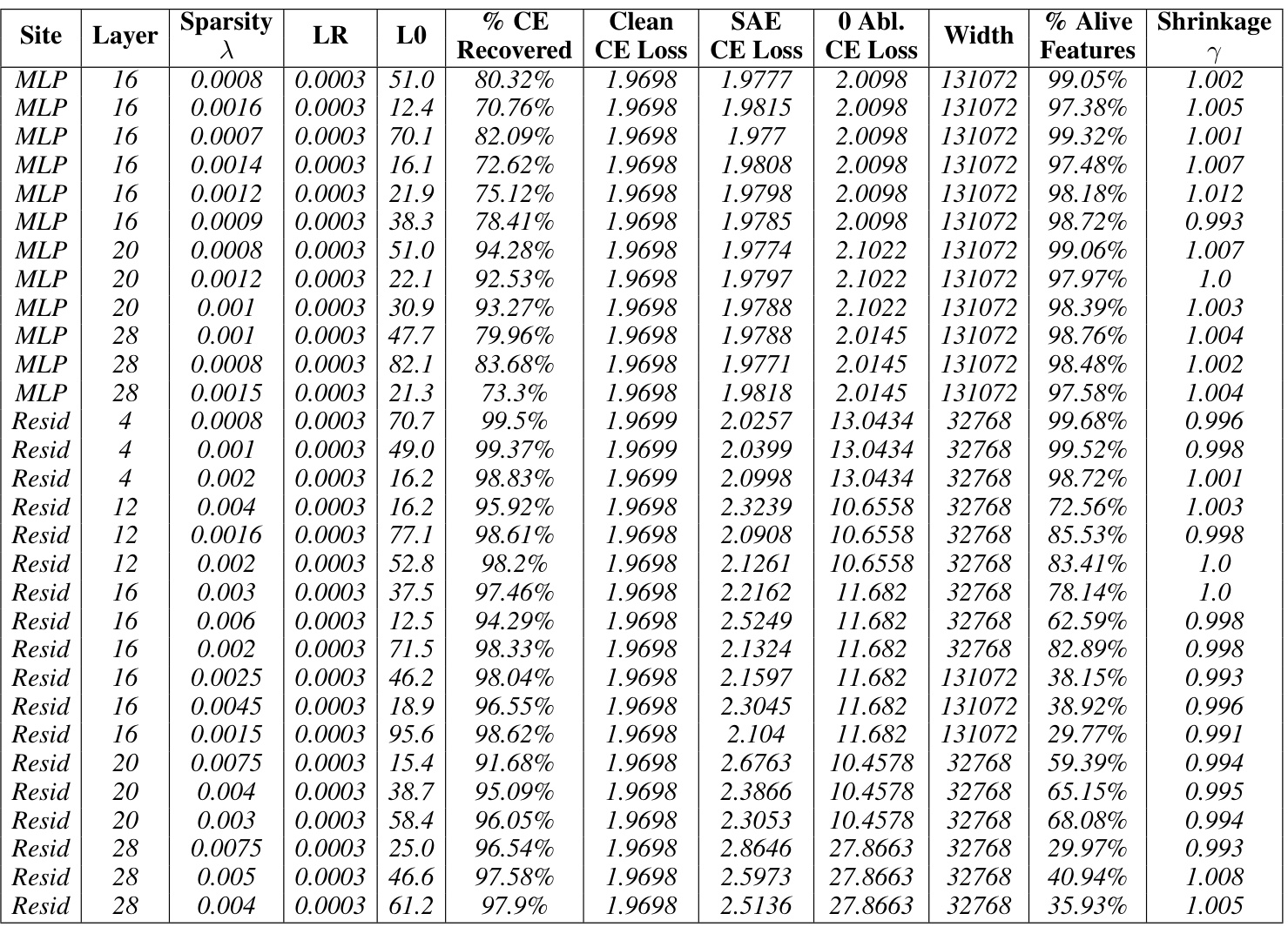

This table presents the results of training baseline sparse autoencoders (SAEs) on the Gemma-7B language model. It shows the hyperparameters used during training, along with key performance metrics and characteristics of the resulting SAEs. Key metrics include reconstruction fidelity (Loss Recovered), sparsity (L0), and the relative reconstruction bias (Shrinkage), indicating whether the SAE’s reconstructions systematically underestimate the true activation magnitudes. The table also specifies the model layer and site the SAEs were trained on, including MLP, attention, and residual stream activations. The Pareto optimal SAEs are italicized, representing a set of SAEs where no improvement can be achieved in reconstruction fidelity without sacrificing sparsity or vice versa. The data is used to compare the performance of baseline SAEs against Gated SAEs.

This table presents the results of training baseline sparse autoencoders (SAEs) on the Gemma-7B language model with 1024 sequence length. For each layer and site (Residual stream, MLP, Attention), various sparsity levels (λ) were tested, and the corresponding learning rate (LR), L0 norm (LO), percentage of loss recovered, clean cross-entropy loss, SAE cross-entropy loss, zero-ablation cross-entropy loss, width of the SAE, percentage of alive features, and shrinkage are reported. The italicized rows represent the Pareto optimal SAEs, indicating the best trade-off between sparsity and reconstruction fidelity.

This table presents the results of training baseline sparse autoencoders (SAEs) on the Gemma-7B language model. The table shows hyperparameters used during training, along with key performance metrics such as the percentage of loss recovered and the L0 sparsity. The italicized entries highlight the Pareto optimal SAEs, representing the best trade-off between reconstruction fidelity and sparsity for each hyperparameter setting. Results are provided for multiple layers and sites within the model.

This table presents the results for Gemma-7B Baseline SAEs, with a sequence length of 1024. It shows various hyperparameters used during training (λ, LR), the resulting sparsity (LO), the percentage of loss recovered, the clean cross-entropy loss, the SAE cross-entropy loss, and the 0-ablation cross-entropy loss. Additionally, the table indicates the width of the SAE, the percentage of alive features, the shrinkage factor (γ), and the number of features. The italicized entries indicate Pareto optimal SAEs, representing a trade-off between reconstruction accuracy and sparsity.

This table presents the results of training baseline sparse autoencoders (SAEs) on the Gemma-7B language model. The table shows the performance of different SAEs with varying sparsity levels (Sparsity), achieved by adjusting the L1 regularization parameter (λ). For each SAE, several metrics are reported: the learning rate (LR) used during training, the number of active features (LO), the percentage of loss recovered relative to a zero-ablation baseline (% CE Recovered), the cross-entropy loss for the original language model (Clean CE Loss), the cross-entropy loss after applying the SAE reconstruction (SAE CE Loss), the cross-entropy loss after zeroing out the activations before the SAE (0 Abl. CE Loss), the width of the SAE’s hidden layer (Width), the percentage of alive neurons (% Alive), the relative reconstruction bias (Shrinkage), and the total number of features used in the SAE dictionary (Features). The italicized entries represent SAEs that achieve a Pareto optimal balance between sparsity and reconstruction fidelity.

This table presents the results of training baseline sparse autoencoders (SAEs) on the Gemma-7B language model. It shows the performance of SAEs at different layers and sites within the model. The key metrics presented include sparsity (LO), reconstruction fidelity (% CE Recovered), and the relative reconstruction bias (Shrinkage). The table helps in understanding how the performance of baseline SAEs varies across different layers and locations within the model. The italicized entries indicate the Pareto optimal SAEs, representing the best tradeoff between sparsity and reconstruction quality.

This table presents the results for Gemma-7B baseline SAEs with a sequence length of 1024. It shows various hyperparameters used during training, including the L1 regularization strength (lambda), learning rate, and the resulting L0 sparsity (average number of active features). Key performance metrics are also listed: Loss Recovered (how well the model’s performance is preserved after using the SAE’s reconstruction), cross-entropy loss for the clean model, the SAE itself and for the zero-ablated (where the corresponding sub-layers activations are set to zero), the width of the SAE and how many features were actually alive (percentage of active features), and the relative reconstruction bias (shrinkage), which measures the extent of underestimation of feature activations. The italicized rows represent Pareto optimal SAEs; these represent trade-offs where improvement in one metric does not come at the cost of worsening another. This table helps to understand the performance of the baseline SAEs and serves as a basis of comparison against Gated SAEs later in the paper.

This table presents the results of training baseline sparse autoencoders (SAEs) on the Gemma-7B language model. The table shows the hyperparameters used for training, including the sparsity penalty (λ), learning rate (LR), and the resulting L0 (sparsity) and loss recovered (reconstruction fidelity). The table also shows the percentage of clean CE loss recovered, clean CE loss, SAE CE loss, 0 Abl. CE loss, the width of the SAE, the percentage of alive features, and the shrinkage observed. The italicized rows indicate the Pareto optimal SAEs, representing the best trade-off between sparsity and reconstruction fidelity.

This table presents the results of training baseline sparse autoencoders (SAEs) on the Gemma-7B language model. It shows the performance of SAEs at different layers (6, 13, 20, 27) and sites (residual stream, MLP, attention) within the model. The table includes hyperparameters (λ, LR), sparsity metrics (LO), reconstruction fidelity (% CE Recovered), cross-entropy loss for clean activations, SAE reconstructions, and zero-ablated activations, the width of the SAE, percentage of alive features, and a shrinkage metric. Italicized entries indicate Pareto optimal SAEs, representing the best trade-off between sparsity and reconstruction fidelity.

This table presents the results of training baseline sparse autoencoders (SAEs) on the Gemma-7B language model. It shows the hyperparameters used for training, the resulting model performance metrics (loss recovered, sparsity (L0), etc.), and whether the model was Pareto optimal. The table focuses on different layers and sites within the model and helps compare performance of different configurations.

Full paper#