↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) struggle with complex reasoning, particularly in mathematics. Existing methods for improving their mathematical abilities often rely on datasets with a bias towards easier problems, limiting performance on challenging queries. This bias arises from the common rejection-tuning approach of equally sampling from all problems, resulting in insufficient data from hard questions.

The DART-Math project tackles this issue by introducing Difficulty-Aware Rejection Tuning (DART). DART prioritizes difficult problems during data synthesis, creating smaller, higher-quality datasets. Experiments show that models trained on DART-Math datasets significantly outperform those trained on existing datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness of focusing on harder problems. This research contributes high-quality, publicly available resources that significantly advance mathematical problem-solving in LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in natural language processing and machine learning due to its focus on improving mathematical reasoning in LLMs. It introduces a novel technique to address the biases in existing datasets and offers cost-effective, publicly available resources to advance this challenging field. The findings and datasets contribute significantly to overcoming the limitations of current methods, opening up new avenues for creating more capable LLMs.

Visual Insights#

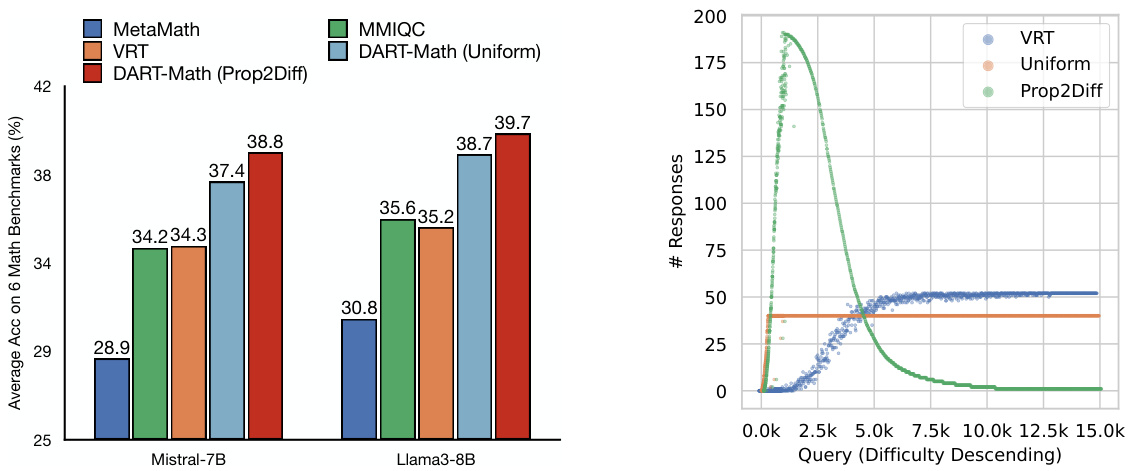

The figure presents a comparison of the average accuracy of different models on six mathematical benchmarks (left panel) and an analysis of the number of responses generated for queries of varying difficulty using three different synthesis strategies (right panel). The left panel shows that DART-Math models outperform other models, including those trained on larger datasets. The right panel illustrates the impact of different sampling strategies on the coverage of difficult queries, highlighting the advantage of the proposed difficulty-aware rejection tuning.

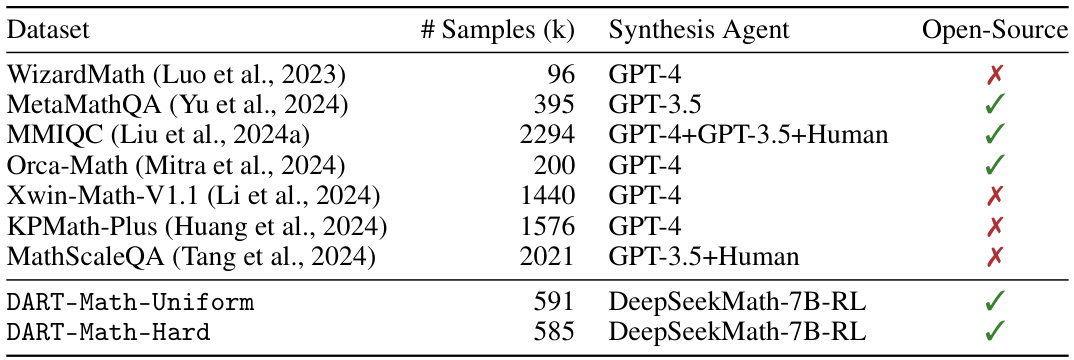

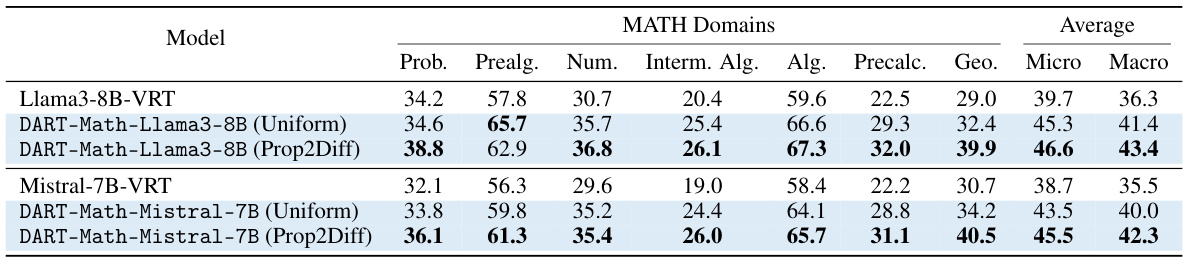

This table compares the DART-Math datasets with other existing mathematical instruction tuning datasets. It highlights key differences such as the number of samples, the model used for synthesis (many use proprietary models like GPT-4, while DART uses an open-weight model), and whether the dataset is publicly available (open-source). The table shows that DART-Math is significantly smaller than most other datasets, yet still achieves state-of-the-art performance, making it a more efficient and accessible resource.

In-depth insights#

Rejection Tuning Bias#

Rejection tuning, a method to enhance large language models (LLMs) by filtering out incorrect responses from a strong model, suffers from a significant bias. This bias disproportionately favors easy queries, leading to insufficient training on difficult problems. The consequence is that LLMs trained this way struggle with complex mathematical reasoning and may fail to generalize effectively. The core issue stems from a sampling strategy that allocates an equal number of trials to each query regardless of difficulty. This means challenging queries, which are often crucial for complex reasoning, are under-represented in the training data. Addressing this bias requires strategies that prioritize more trials for difficult queries, ensuring more extensive training data on challenging examples. This could involve dynamically adjusting sampling frequency based on query difficulty or employing methods that ensure sufficient coverage of the difficulty spectrum in training data. This approach has significant implications for improving LLMs in tasks requiring complex reasoning.

DART Methodology#

The core of the DART methodology centers on addressing the inherent biases within existing rejection-tuning datasets for mathematical problem-solving. These biases skew towards easier queries, leaving many challenging problems under-represented in the training data. DART innovatively introduces a difficulty-aware sampling strategy, allocating more synthesis trials to harder queries. This ensures a more balanced dataset enriched with solutions to complex problems. The approach uses a 7B-sized open-weight model, removing the reliance on expensive proprietary models. Two strategies, Uniform and Prop2Diff, are presented, allowing for control over the dataset’s difficulty distribution. Prop2Diff, in particular, prioritizes difficult problems, potentially leading to more robust and generalizable models. The effectiveness is demonstrated through significant performance improvements across various mathematical benchmarks, showcasing DART’s potential as a cost-effective and efficient method for advancing mathematical problem-solving in LLMs.

DART Datasets#

The DART datasets represent a significant contribution to the field of mathematical problem-solving with LLMs. Their key innovation lies in addressing the inherent bias towards easier problems found in existing datasets created via rejection sampling. By prioritizing the sampling of responses to more difficult queries, DART datasets achieve better coverage of challenging problems, leading to models that generalize better. The use of an open-weight model for data synthesis, rather than proprietary models like GPT-4, makes the DART methodology more accessible and cost-effective. The creation of both Uniform and Prop2Diff versions of the dataset, offering different response distributions, allows for flexibility in training, and the resulting models demonstrate significant improvements over baselines on various benchmarks. However, the reliance on a single metric (fail rate) for difficulty assessment might limit the dataset’s overall representativeness. Future work could explore incorporating multiple metrics and expanding the dataset’s scope further.

Empirical Evaluation#

A robust empirical evaluation section is crucial for validating the claims of a research paper. It should present a comprehensive assessment of the proposed method’s performance, comparing it against relevant baselines and state-of-the-art techniques on a diverse range of datasets and metrics. Careful selection of benchmark datasets is vital, encompassing both in-domain and out-of-domain tasks to establish generalizability. The evaluation should go beyond simple accuracy scores, exploring other relevant metrics such as efficiency (inference speed and computational cost) and robustness to various forms of noise or adversarial attacks. Statistical significance testing is necessary to determine if the observed performance differences are genuine rather than due to chance. The results should be presented clearly and transparently, potentially using visualizations like graphs and tables to enhance understanding. Detailed analysis of the results, including potential error sources and limitations of the method, will strengthen the evaluation’s credibility and contribute to future research. A well-executed empirical evaluation ultimately establishes the practical impact of the proposed approach.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore more sophisticated difficulty metrics beyond the fail rate, potentially incorporating human evaluation or leveraging advanced LLMs to assess problem complexity more accurately. Investigating alternative data synthesis strategies, including techniques that go beyond simple rejection sampling, could also be valuable. This might involve exploring methods like reinforcement learning or generative models specifically designed to create challenging and diverse mathematical problems. Additionally, the research could be extended to other reasoning tasks or domains, exploring the generalizability of the difficulty-aware rejection tuning approach beyond mathematics. Finally, a significant area for future work would be to fully analyze the impact of varying the number of training samples on the effectiveness of the model. This could involve exploring the optimal balance between the cost of data generation and the resulting performance improvements. By conducting a detailed cost-benefit analysis, researchers could determine the ideal size of the synthetic dataset.

More visual insights#

More on figures

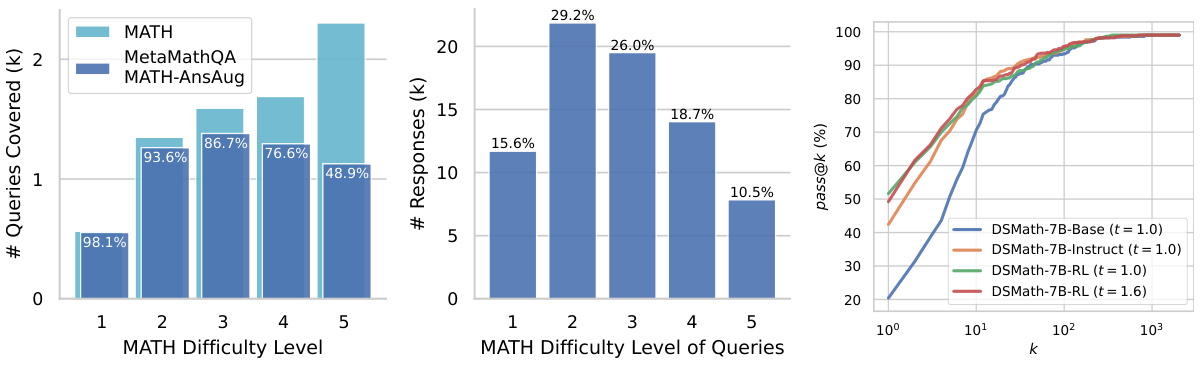

This figure shows the bias of rejection-based data synthesis towards easy queries. The left panel shows that the proportion of difficult queries (Level 5) decreases significantly in the synthetic dataset MetaMathQA compared to the original MATH dataset. The middle panel shows that the number of responses for difficult queries is also much smaller in MetaMathQA. The right panel shows that a strong model (DeepSeekMath-7B-RL) can generate correct responses for most queries given enough trials, suggesting that the bias in rejection-based data synthesis is not due to the inherent difficulty of the queries but rather to the sampling strategy.

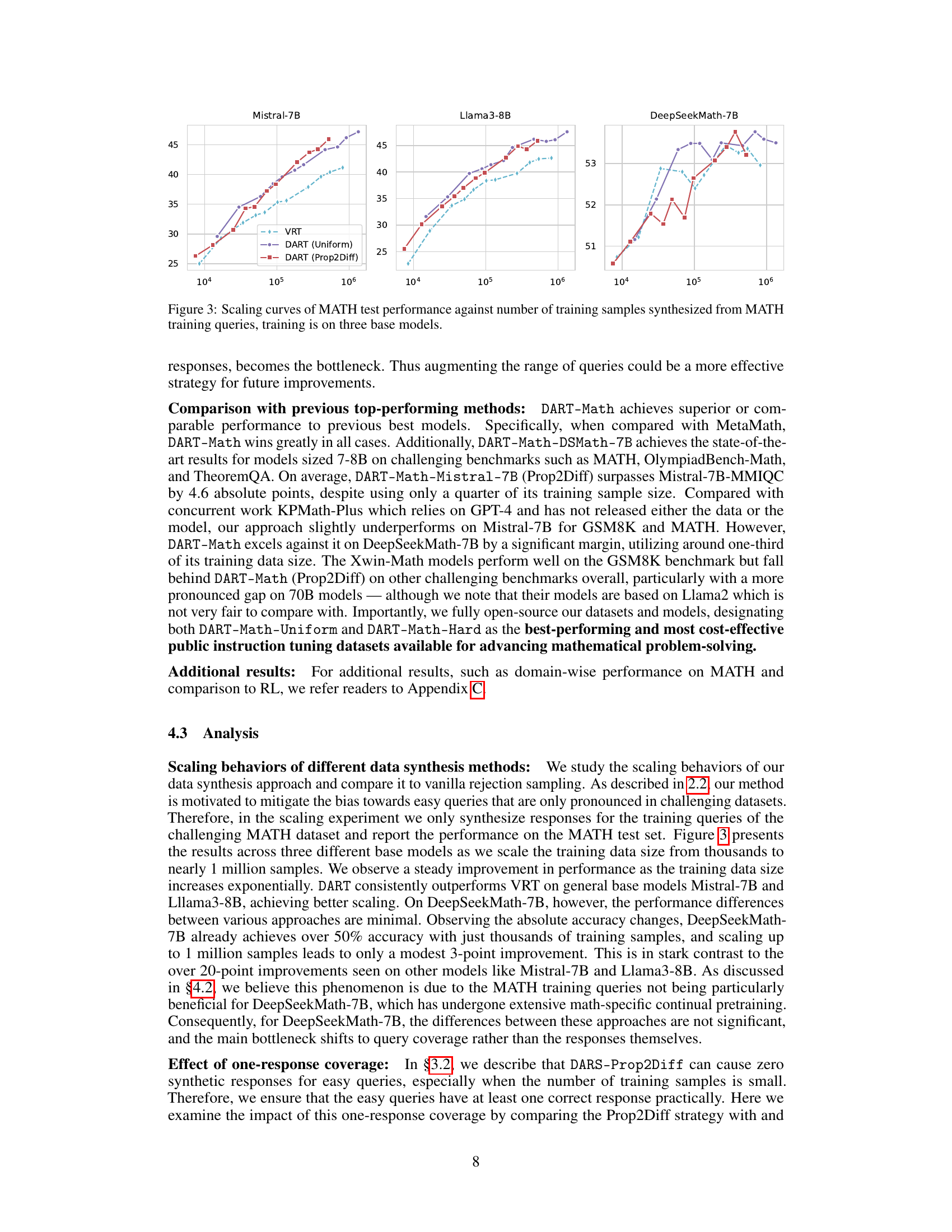

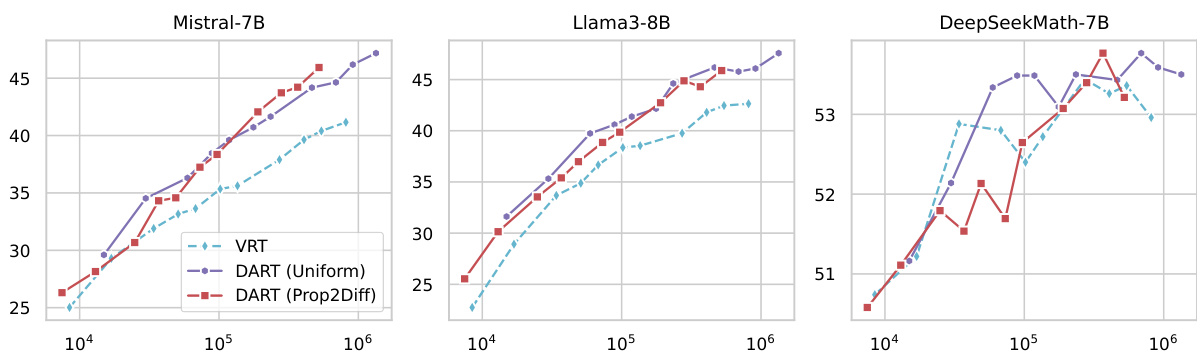

This figure shows the scaling curves of MATH test performance for three different base models (Mistral-7B, Llama3-8B, and DeepSeekMath-7B) as the number of training samples increases. The x-axis represents the number of training samples (log scale), and the y-axis represents the accuracy on the MATH test set. Three lines are plotted for each model, representing the performance of vanilla rejection tuning (VRT), DART with uniform sampling, and DART with difficulty-proportional sampling. The figure demonstrates that DART, particularly the difficulty-proportional version, consistently outperforms VRT across all three models and across a wide range of training data sizes, highlighting the effectiveness of the difficulty-aware rejection tuning technique.

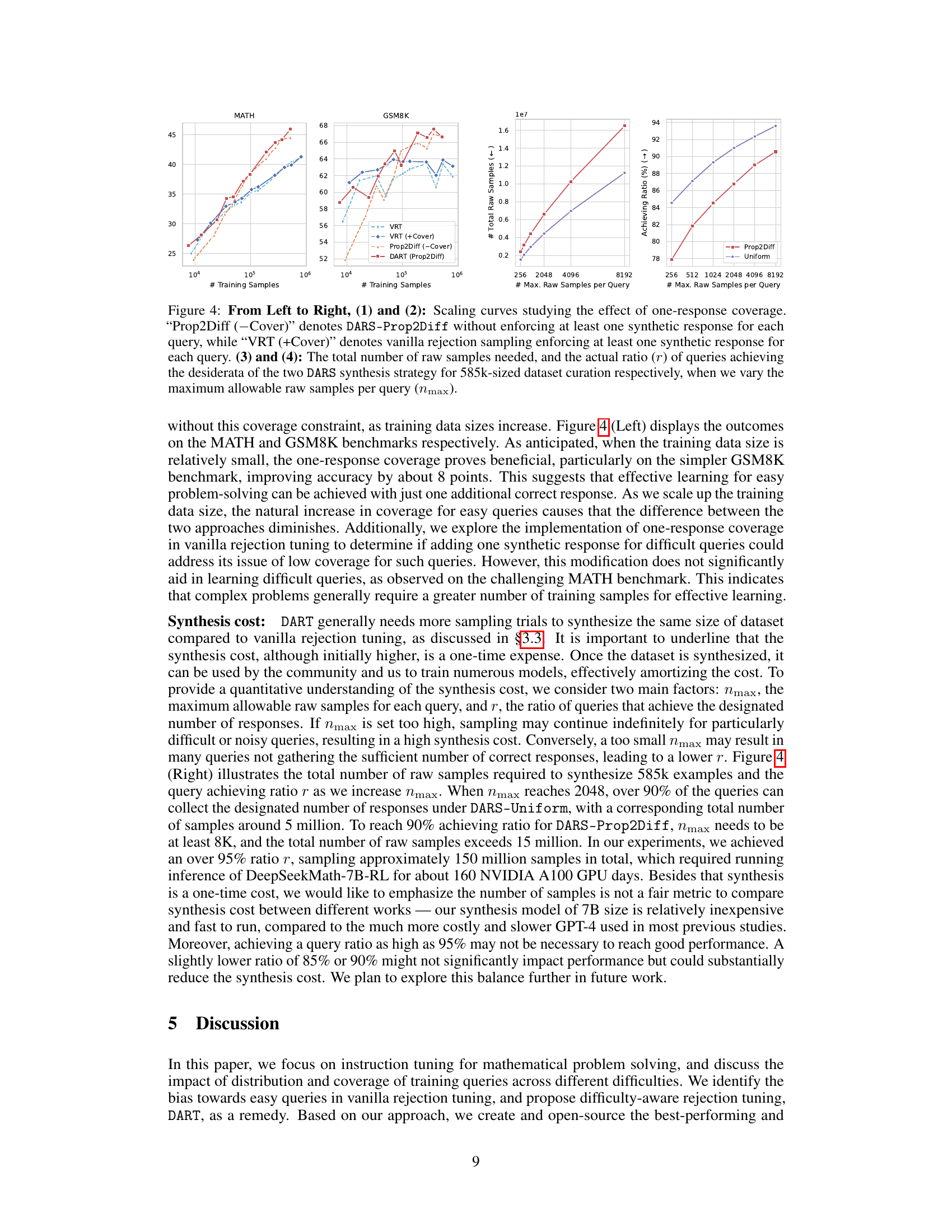

This figure analyzes the impact of ensuring at least one synthetic response for each query during data synthesis. It shows scaling curves for MATH and GSM8K benchmarks comparing vanilla rejection tuning (VRT) with and without the one-response constraint, and DARS-Prop2Diff with and without the constraint. Additionally, it illustrates the total number of raw samples needed and the ratio of queries achieving the desired number of correct responses for both DARS strategies, varying the maximum number of raw samples per query.

More on tables

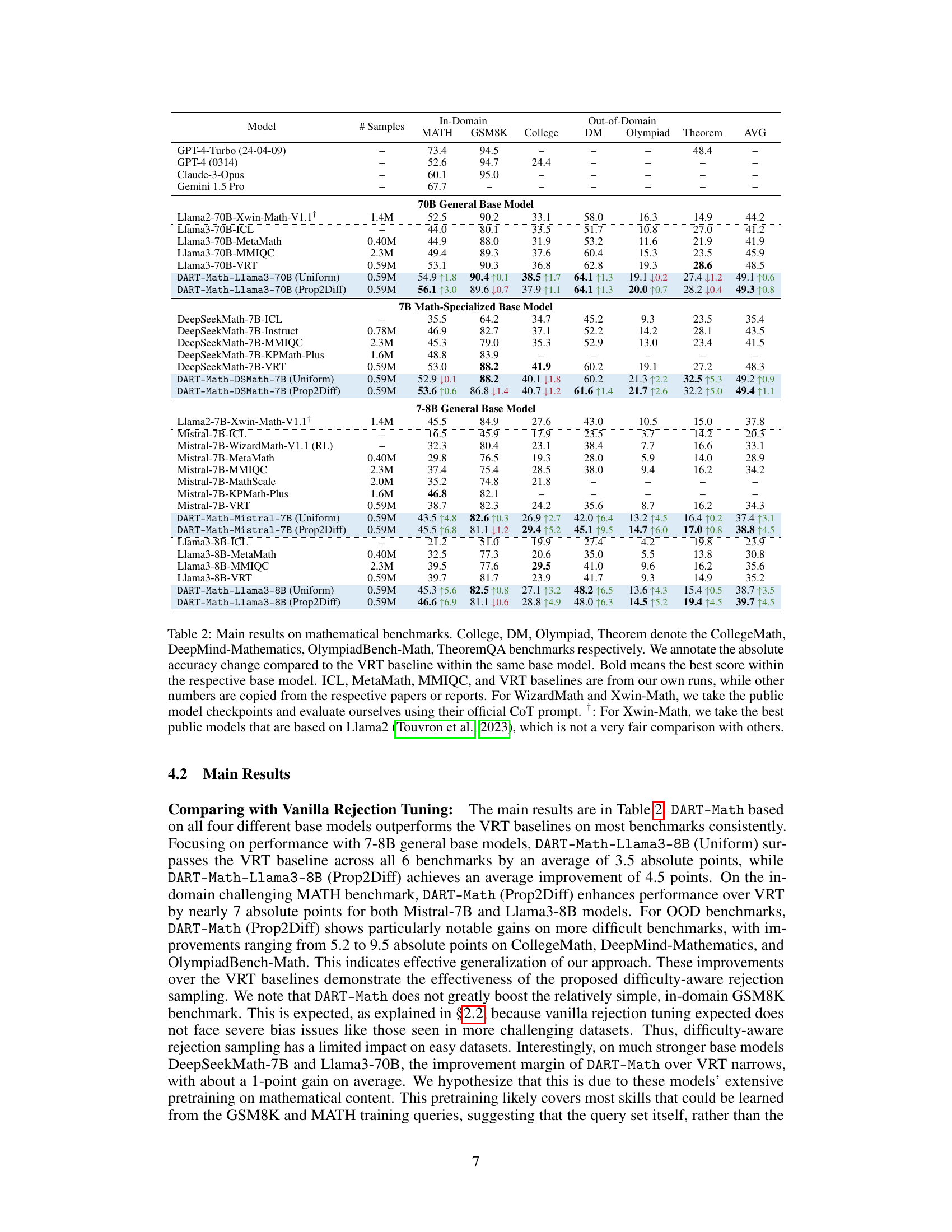

This table presents the main experimental results comparing the performance of DART-Math models with various baselines across six mathematical benchmarks (two in-domain and four out-of-domain). It shows the accuracy on each benchmark for different models (varying in size and architecture), including those fine-tuned with different datasets (MetaMath, MMIQC, KPMath-Plus, Xwin-Math, Vanilla Rejection Tuning, and DART-Math with Uniform and Prop2Diff strategies). The table highlights the improvements achieved by DART-Math, especially its superior performance on challenging out-of-domain benchmarks despite using smaller datasets. It also indicates the difference between DART-Math models trained using the Uniform and Prop2Diff sampling strategies.

This table compares the number of responses per query (RPQ) for datasets created using ToRA, MARIO, and DART-Math methods. It shows the RPQ for GSM8K queries and for different difficulty levels (1-5) within the MATH dataset. The MATH Coverage indicates the percentage of queries in the MATH dataset for which at least one response was generated. The table highlights that DART-Math generates a significantly larger number of responses, particularly for the more difficult MATH queries (levels 3-5), demonstrating its ability to overcome the bias towards easier queries that other methods suffer from.

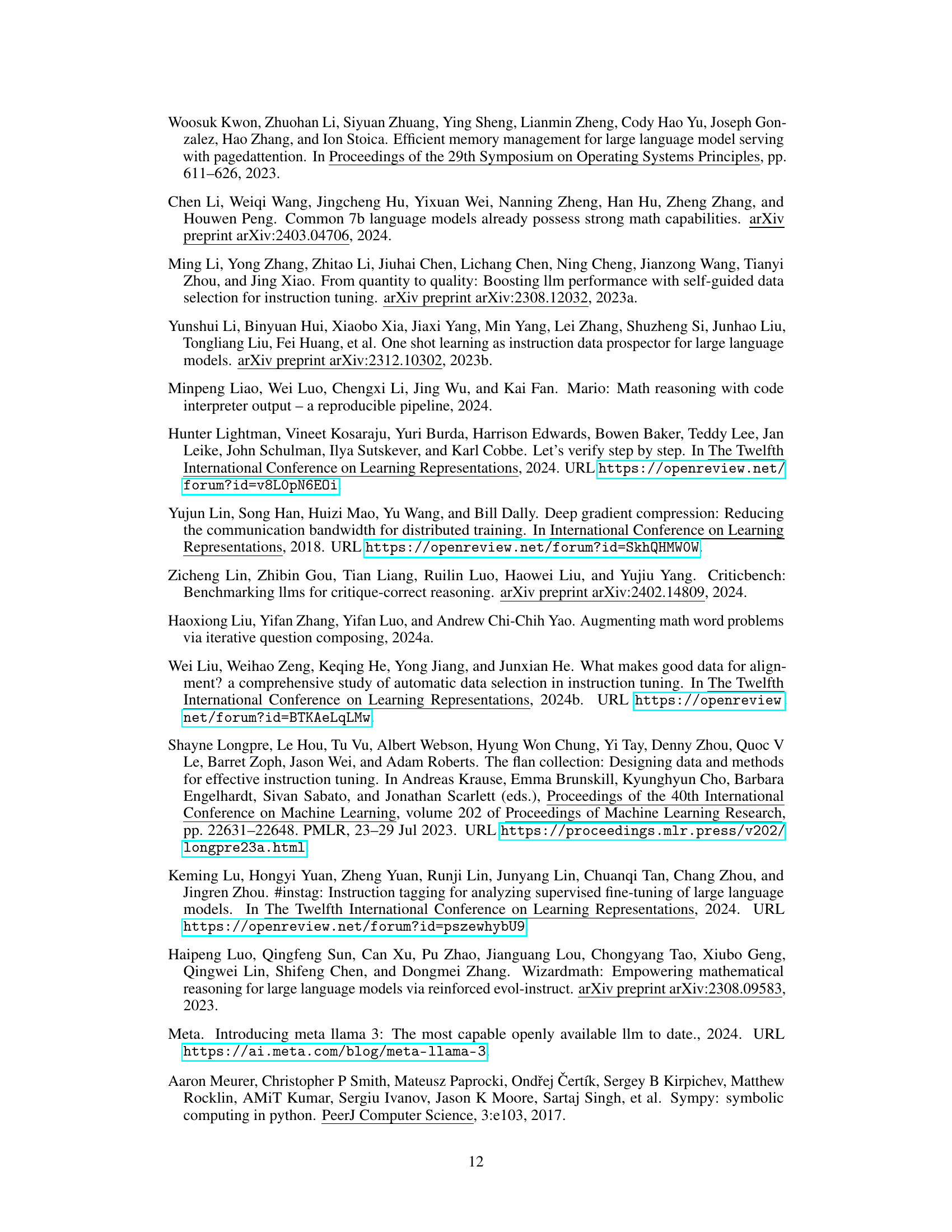

This table compares the coverage of different difficulty levels of MATH training queries across four different synthetic datasets: ToRA-Corpus-16k-MATH, MetaMathQA-MATH-AnsAug, a Vanilla Rejection Tuning (VRT) baseline, and the two DART-Math datasets (Uniform and Prop2Diff). It shows the percentage of queries covered at each difficulty level (1-5, with 5 being the most difficult). The DART-Math datasets achieve significantly higher coverage, especially at the most difficult level, demonstrating their effectiveness in addressing the class imbalance in mathematical problem-solving datasets.

This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted on six mathematical benchmarks. The table compares the performance of DART-Math models (using different base models and data synthesis strategies) against several baselines (Vanilla Rejection Tuning and state-of-the-art models from other papers). Both in-domain and out-of-domain benchmarks are included. Performance is measured by average accuracy, and improvements compared to the VRT baseline are highlighted.

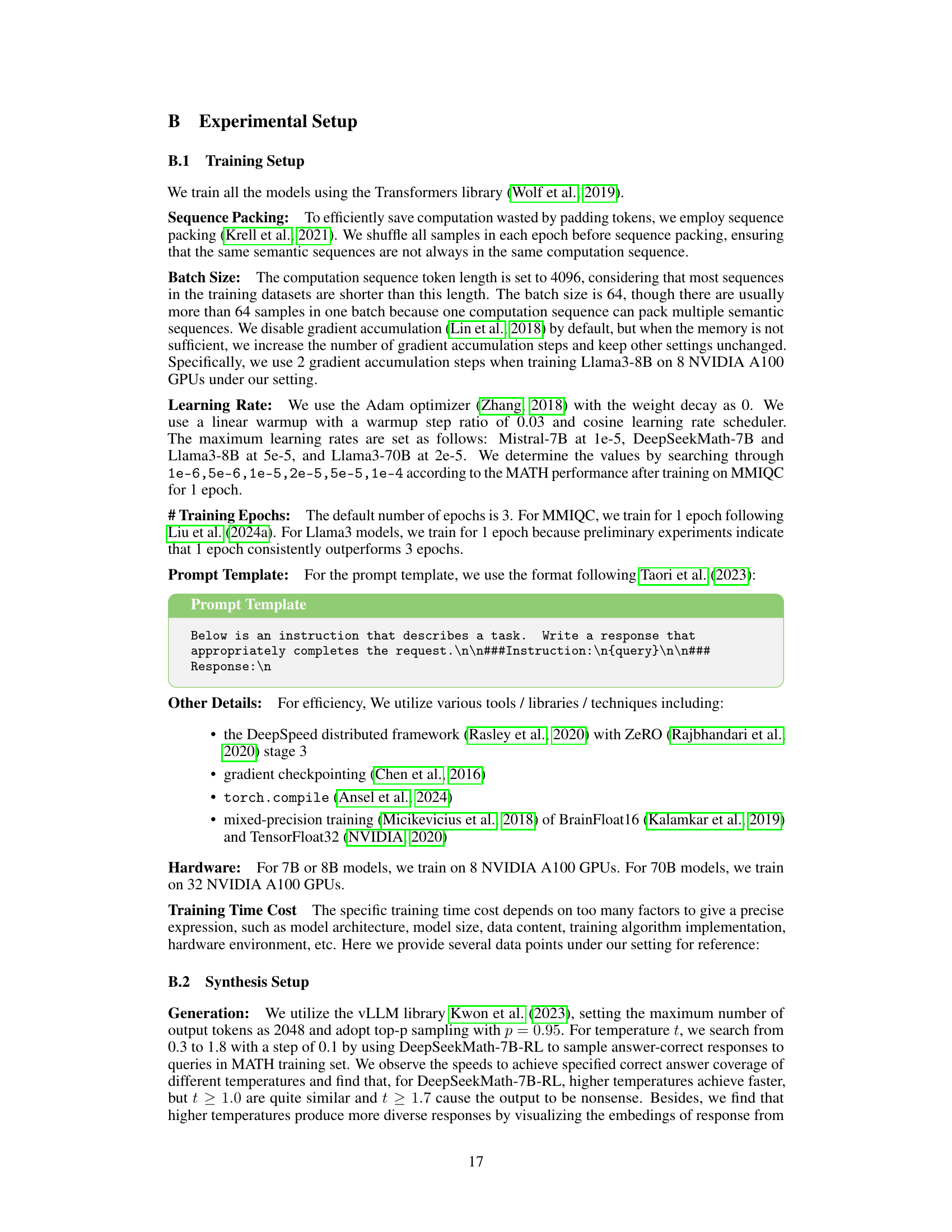

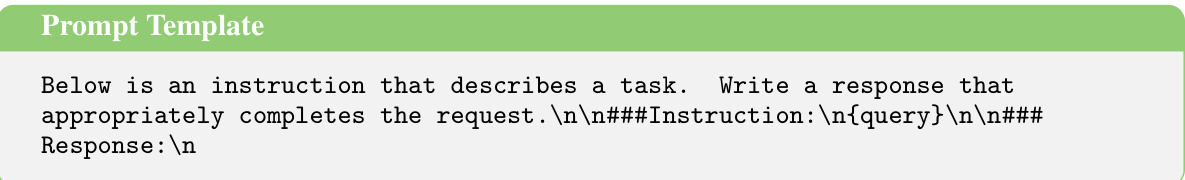

This table shows the training time cost for different models on the DART-Math-Hard dataset. The training time cost varies depending on the model size and the hardware used. For example, training DeepSeekMath-7B on 8 A100 GPUs takes 3 hours per epoch, while training Llama3-70B on 32 A100 GPUs takes 6 hours per epoch.

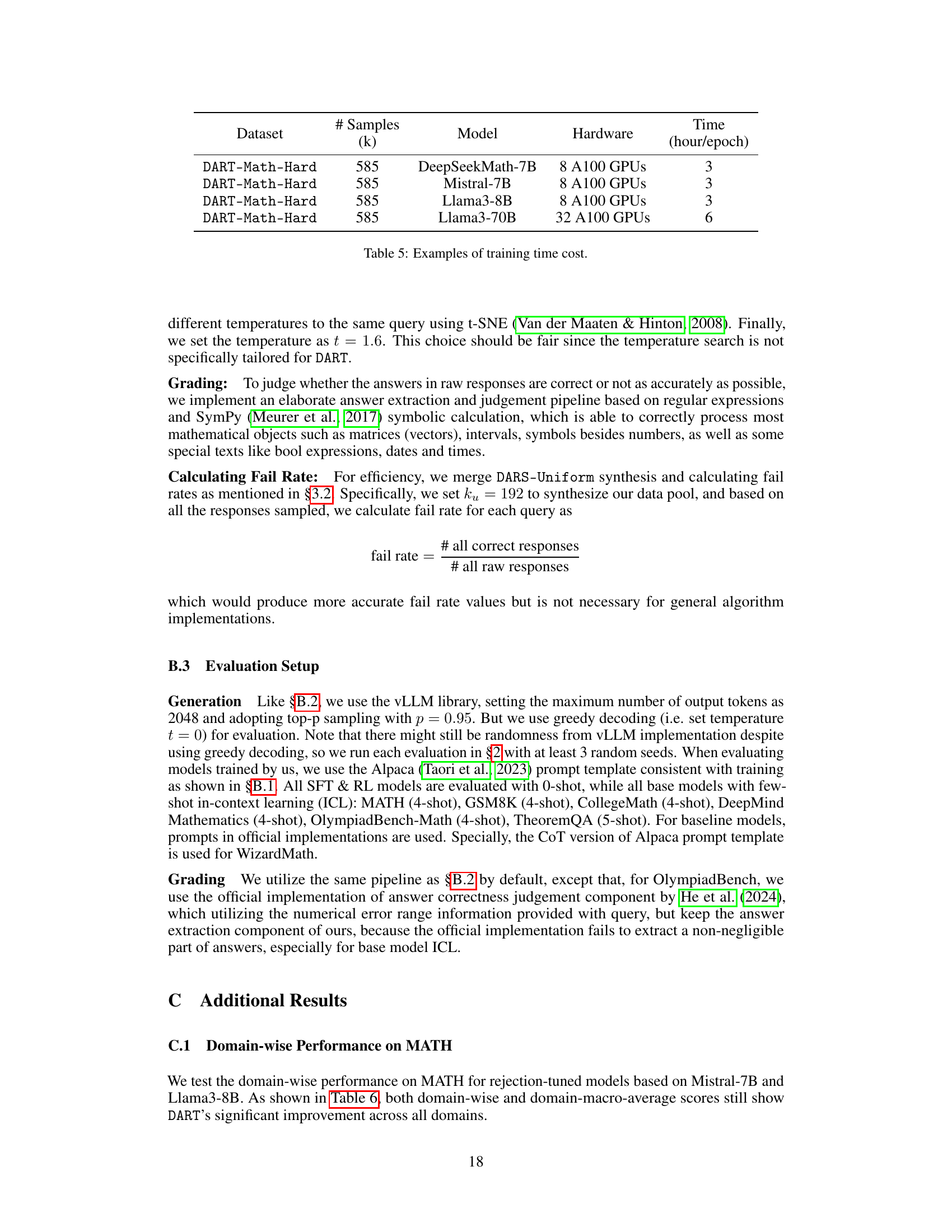

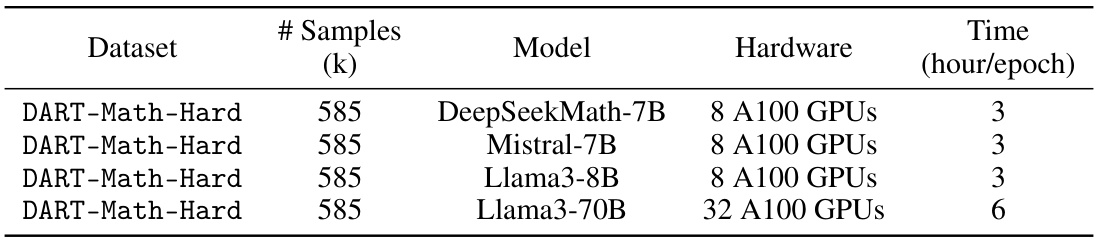

This table presents a detailed breakdown of the performance of different models on six mathematical domains within the MATH benchmark. It compares the vanilla rejection tuning (VRT) baseline with the DART-Math models using both uniform and difficulty-proportional sampling strategies. The results are shown for both micro and macro averages, providing insights into the model’s performance across different query types and overall.

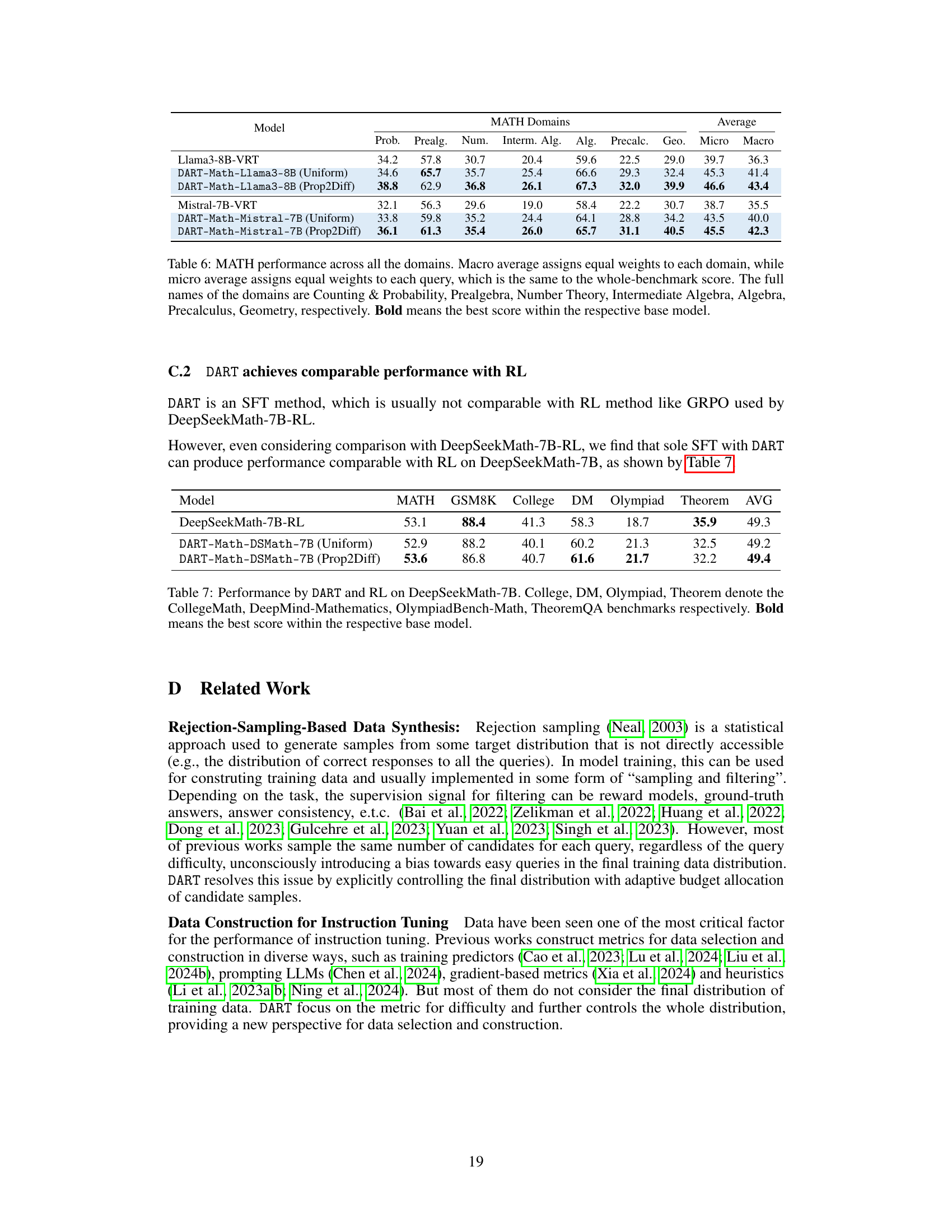

This table compares the performance of DART-Math models with a reinforcement learning (RL) model, DeepSeekMath-7B-RL, on six mathematical benchmarks. It shows that DART-Math, despite being a supervised fine-tuning (SFT) method, achieves comparable performance to DeepSeekMath-7B-RL, a reinforcement learning model. The results highlight that DART-Math’s performance is competitive, even when compared to approaches utilizing RL.

Full paper#