↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Fairness in recommendation systems is a multifaceted problem involving both user satisfaction and equitable item exposure. Existing algorithms often prioritize one over the other, leading to suboptimal outcomes for some users or items. This research addresses this limitation by investigating the complex interplay between user fairness, item fairness, and overall recommendation quality. It identifies scenarios where one type of fairness might come “for free” and others where there are unavoidable tradeoffs, particularly for users with poorly estimated preferences.

The study develops a novel theoretical model to formally analyze user-item fairness tradeoffs. The model considers user preference diversity and accuracy of preference estimations as key factors influencing the trade-off. The researchers validate their theoretical findings through an empirical study using real-world data from arXiv preprints. Their framework provides valuable guidance for algorithm designers on optimizing for multi-sided fairness, offering concrete recommendations for building more equitable and effective recommendation systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on fairness in recommendation systems. It offers a novel theoretical framework for analyzing user-item fairness tradeoffs, providing valuable insights into the real-world effects of fairness constraints. The empirical results further validate the theoretical findings and highlight the importance of considering user preference diversity and the potential impact of estimation errors on fairness. This work will shape the development of more effective and equitable recommendation systems.

Visual Insights#

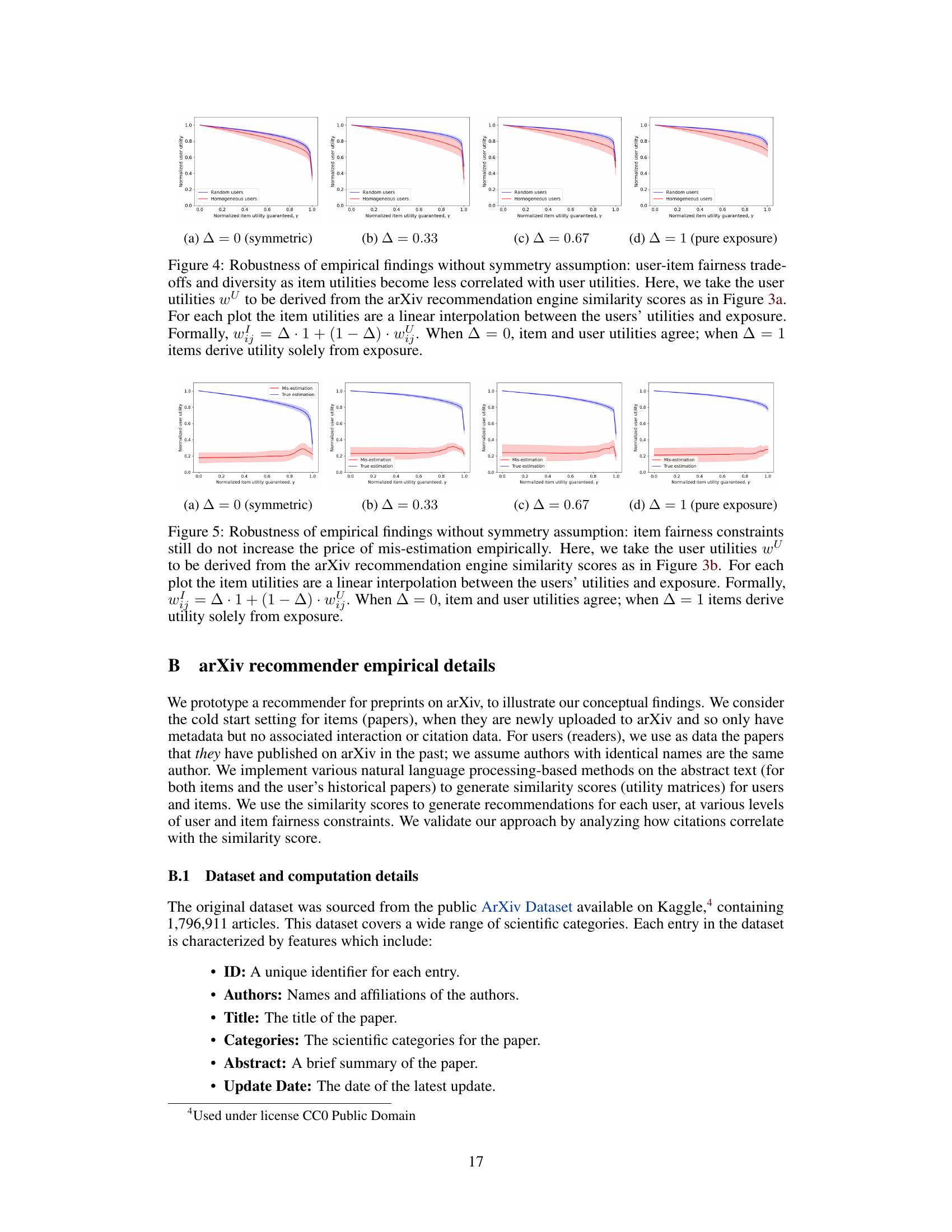

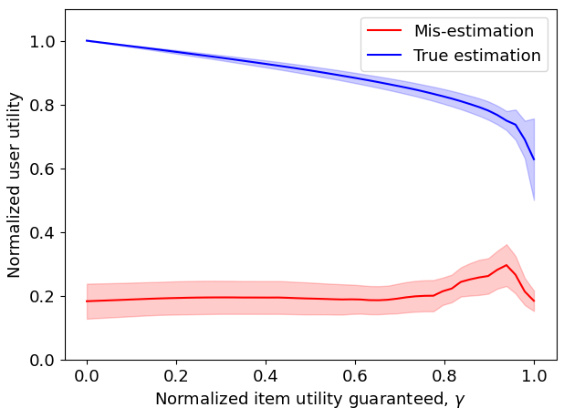

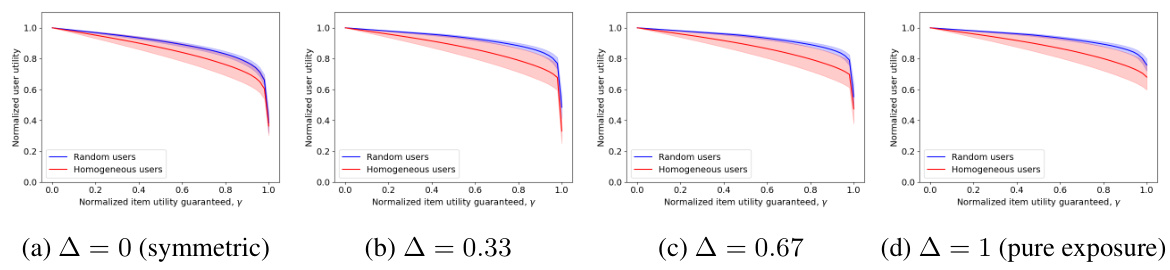

This figure shows the tradeoff between user and item fairness with and without the presence of misestimation. Panel (a) shows how the cost of achieving item fairness increases with more homogenous user populations, supporting a key theoretical finding (Theorem 3). Panel (b) illustrates the impact of misestimation on this tradeoff, demonstrating that while misestimation increases costs, the effect is not worsened by imposing item fairness constraints.

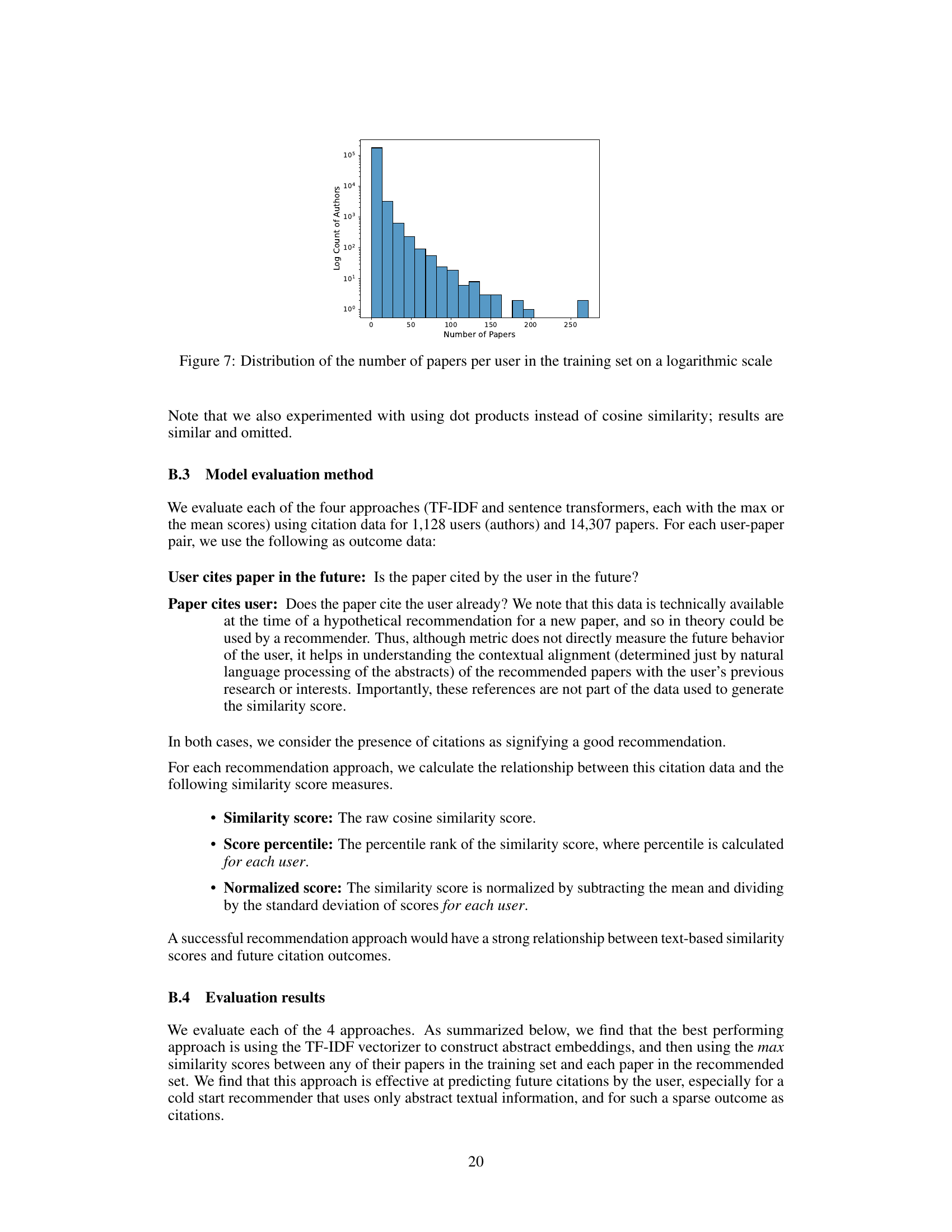

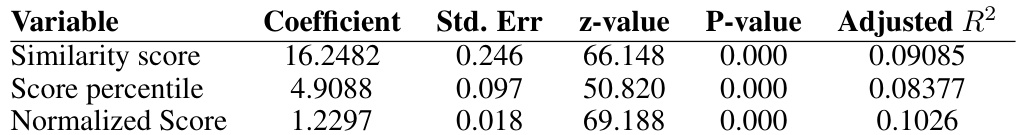

This table presents the results of logistic regression models used to predict whether a user (i) cites a paper (j) based on the similarity score (wij) between them. Four different models were used: Max score and Mean score with TF-IDF and Max score and Mean score with Sentence transformer. The table shows the coefficient, standard error, z-value, and adjusted R-squared for each model. The adjusted R-squared indicates the proportion of variance in citation behavior that is explained by the model, after adjusting for the number of predictors. Higher values of the coefficient indicate a stronger positive relationship between similarity score and citation.

In-depth insights#

Fairness Tradeoffs#

The concept of “Fairness Tradeoffs” in recommendation systems is a critical area of research. It explores the inherent tension between optimizing for user satisfaction (relevance) and ensuring fairness across users and items. Prioritizing user relevance often leads to skewed outcomes, where some items receive disproportionately less exposure, thus creating item unfairness. Conversely, enforcing item fairness necessitates compromising on individual user preferences, introducing user unfairness. Multi-sided fairness aims to balance these competing objectives, but the ideal tradeoff point is highly context-dependent, influenced by factors like user preference diversity and accuracy of user preference estimations. Diverse user preferences can alleviate fairness concerns, as it naturally allows a wider spread of item recommendations. However, imperfect knowledge of user preferences amplifies the challenge, potentially exacerbating unfairness for groups with less data. This highlights the need for a nuanced approach to fairness in recommendations, adapting strategies to specific settings rather than enforcing a one-size-fits-all solution.

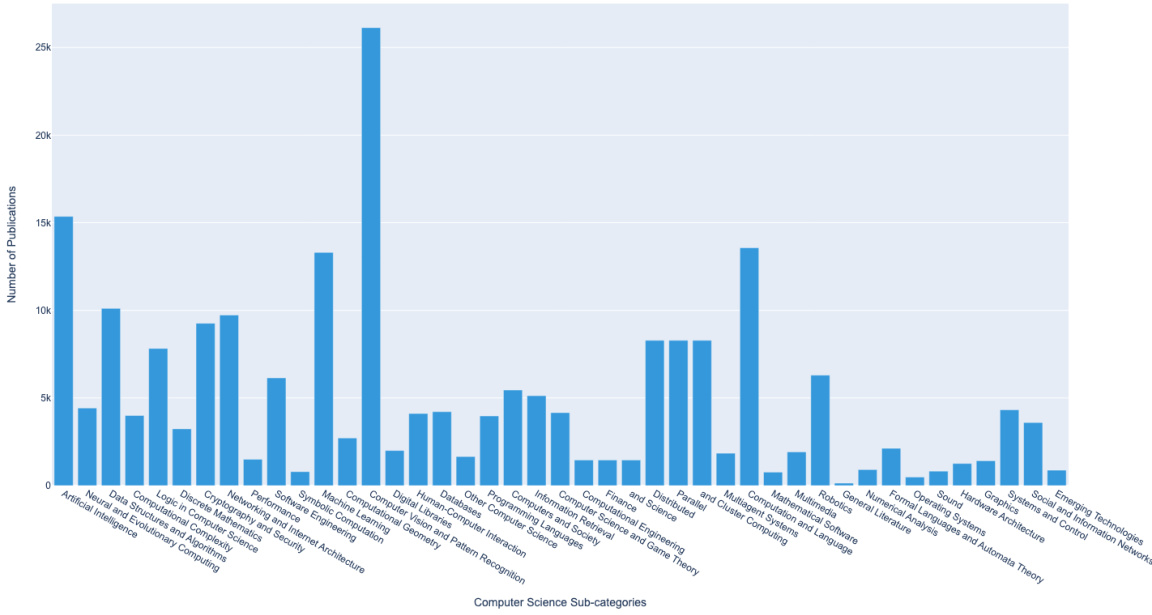

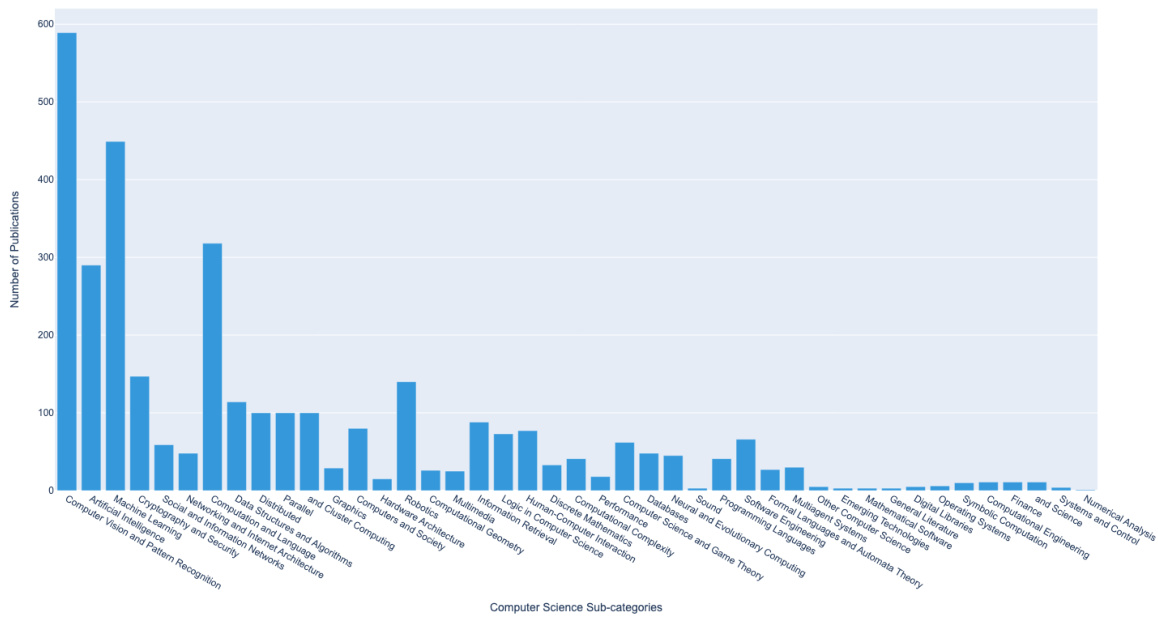

arXiv Preprint Engine#

The research paper details prototyping an arXiv preprint recommendation engine to empirically validate theoretical findings on user-item fairness tradeoffs. The engine leverages paper metadata and text to create embeddings, utilizing TF-IDF and Sentence Transformer models for feature extraction. Cosine similarity scores measure the relationship between user preferences (inferred from their past uploads) and new preprints, which are then used for recommendations. Two key observations are highlighted in the empirical findings: The impact of user preference diversity on fairness tradeoffs and the cost of mis-estimated user preferences (cold-start problem). The empirical findings confirm some theoretical results, such as the decrease in price of fairness with increased user diversity. However, they also reveal some important limitations of current fairness models and highlight the need to consider the effects of user preference uncertainty on the real-world efficacy of fairness-aware recommendation systems. The engine showcases a practical application of the theoretical framework, bridging the gap between theoretical analysis and real-world implementation of fairness-constrained recommendation systems.

Price of Misestimation#

The section on “Price of Misestimation” delves into the critical impact of imperfect knowledge of user preferences on the fairness and effectiveness of recommendation systems. It highlights how the use of estimated utilities, rather than true preferences, significantly alters the trade-offs between user and item fairness. The core argument emphasizes that item fairness constraints can exacerbate the negative consequences of this misestimation, particularly affecting users with poorly estimated preferences, often those new to the platform (‘cold-start users’). The analysis underscores that algorithms striving for item fairness may inadvertently provide these users with items they least prefer, thus worsening their experience. This phenomenon, termed “reinforced disparate effects,” is a crucial insight for designers of fair recommendation systems, advocating for careful consideration of preference uncertainty, and underscoring the need for robust algorithms that can handle this lack of perfect information. The theoretical findings are supported by empirical evidence from a real-world implementation.

Diverse Preferences#

The concept of “diverse preferences” in recommendation systems is crucial for achieving fairness and efficiency. High preference diversity implies that users have varying tastes, leading to a scenario where it becomes easier to satisfy both user and item fairness simultaneously. This is because the system can more easily recommend less popular items to users without drastically harming their overall satisfaction. Conversely, low preference diversity, where many users share similar tastes, makes satisfying item fairness much more challenging. In such cases, satisfying item fairness often requires compromising user satisfaction by recommending less-preferred items to users, leading to a higher “price of fairness.” This highlights the importance of understanding user preference distributions when designing fair recommendation algorithms and demonstrates that, in diverse settings, algorithmic fairness can be achieved with minimal tradeoffs.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore relaxing the assumption of recommending only a single item per user, investigating how the price of fairness changes with the number of recommended items. Extending the theoretical framework to other fairness definitions, such as those beyond egalitarian fairness, and exploring the implications in diverse settings would be valuable. Addressing the tension between maximizing total platform utility and satisfying fairness constraints is another crucial direction, as a platform rarely optimizes for the worst-off user at the expense of overall user engagement. Further empirical work is needed to characterize user-item fairness tradeoffs across different platforms and contexts, as the real-world effects are likely context-dependent. A focus on better understanding the effects of user preference uncertainty is vital, considering how mis-estimation of preferences exacerbates the impact of fairness constraints on users, especially cold start users. Finally, investigating the fairness implications in dynamic settings, where user preferences and item availability evolve over time, would be a significant contribution.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure empirically illustrates the trade-off between user and item fairness in a recommendation system for arXiv preprints. Panel (a) shows that homogeneous user populations exhibit a steeper trade-off (higher price of fairness) compared to diverse user populations, supporting Theorem 3 from the paper. Panel (b) examines the impact of preference estimation uncertainty (‘misestimation’). It shows that the impact of estimation uncertainty remains significant regardless of the level of item fairness constraint, which contrasts with the theoretical worst-case analysis in the paper.

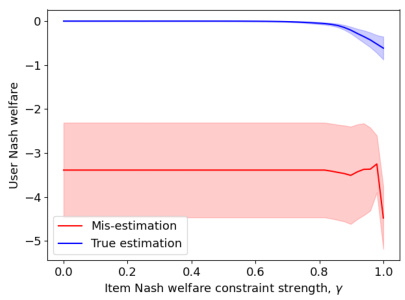

This figure shows the tradeoff between user and item fairness, using Nash welfare instead of max-min fairness as in Figure 1. It repeats the experiment comparing homogeneous and diverse user populations, and also shows how these tradeoffs are affected by misestimation of user preferences. The key difference is the use of Nash welfare, a more holistic measure of fairness than the original max-min approach. Note the change in the y-axis and different y-interpretation to accommodate the change in fairness measure.

This figure shows two subfigures, both illustrating the tradeoff between user and item fairness in a recommendation system for arXiv preprints. Subfigure (a) demonstrates that homogeneous user populations result in a steeper tradeoff (higher price of fairness) compared to diverse populations. Subfigure (b) compares the impact of misestimation on the tradeoff, showing that while the cost of misestimation is generally high, it’s not worsened by item fairness constraints.

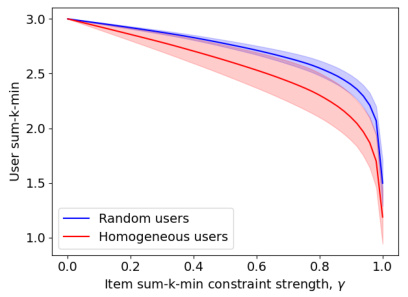

This figure shows the tradeoff between user fairness and item fairness in a random population and in a homogeneous population using the max-sum-k-min fairness measure with k=3. The x-axis represents the item fairness constraint strength (γ), and the y-axis represents the user fairness metric. Subplots show (a) tradeoff between user and item fairness for diverse and homogenous groups of users; (b) impact of misestimation on this tradeoff.

This figure shows empirical results from an arXiv preprint recommender system. Panel (a) shows the tradeoff between minimum user utility and minimum item utility under different levels of item fairness constraints. It supports Theorem 3, indicating a higher price of fairness for homogeneous user populations. However, the price is generally low unless extremely strict item fairness constraints are used. Panel (b) compares the effect of misestimation (estimated utilities instead of true utilities) on user fairness, revealing a significant increase in cost when utilities are misestimated.

This figure empirically demonstrates the tradeoffs between user and item fairness in a real-world recommendation system for arXiv preprints. Subfigure (a) shows how homogeneous user populations experience a much steeper tradeoff (higher ‘price of fairness’) than diverse populations. Subfigure (b) explores the impact of mis-estimated user preferences on the tradeoff, demonstrating that the cost of misestimation is already significant, and is not exacerbated by item fairness constraints.

This figure empirically shows the tradeoffs between user and item fairness, and how these tradeoffs are affected by misestimation. Part (a) shows that homogeneous user populations have a steeper tradeoff curve than diverse populations, illustrating Theorem 3. Part (b) demonstrates the cost of mis-estimating user preferences. The results suggest that this cost can be high even without item fairness constraints, and it does not necessarily get worse with the addition of those constraints.

This figure shows the empirical tradeoff between user and item fairness in a recommendation system for arXiv preprints. Panel (a) demonstrates that homogeneous user populations experience a higher price of fairness (greater loss in user utility for a given increase in item fairness) than diverse populations. Panel (b) illustrates the impact of misestimating user preferences (e.g., cold start users) on the fairness tradeoff, revealing that while the cost of misestimation is high, it is not exacerbated by item fairness constraints.

This figure empirically shows the tradeoff between user and item fairness in a recommendation system. Subfigure (a) demonstrates that homogeneous user populations exhibit a higher price of fairness than diverse populations, aligning with Theorem 3. Subfigure (b) compares the impact of misestimation on user fairness with and without item fairness constraints.

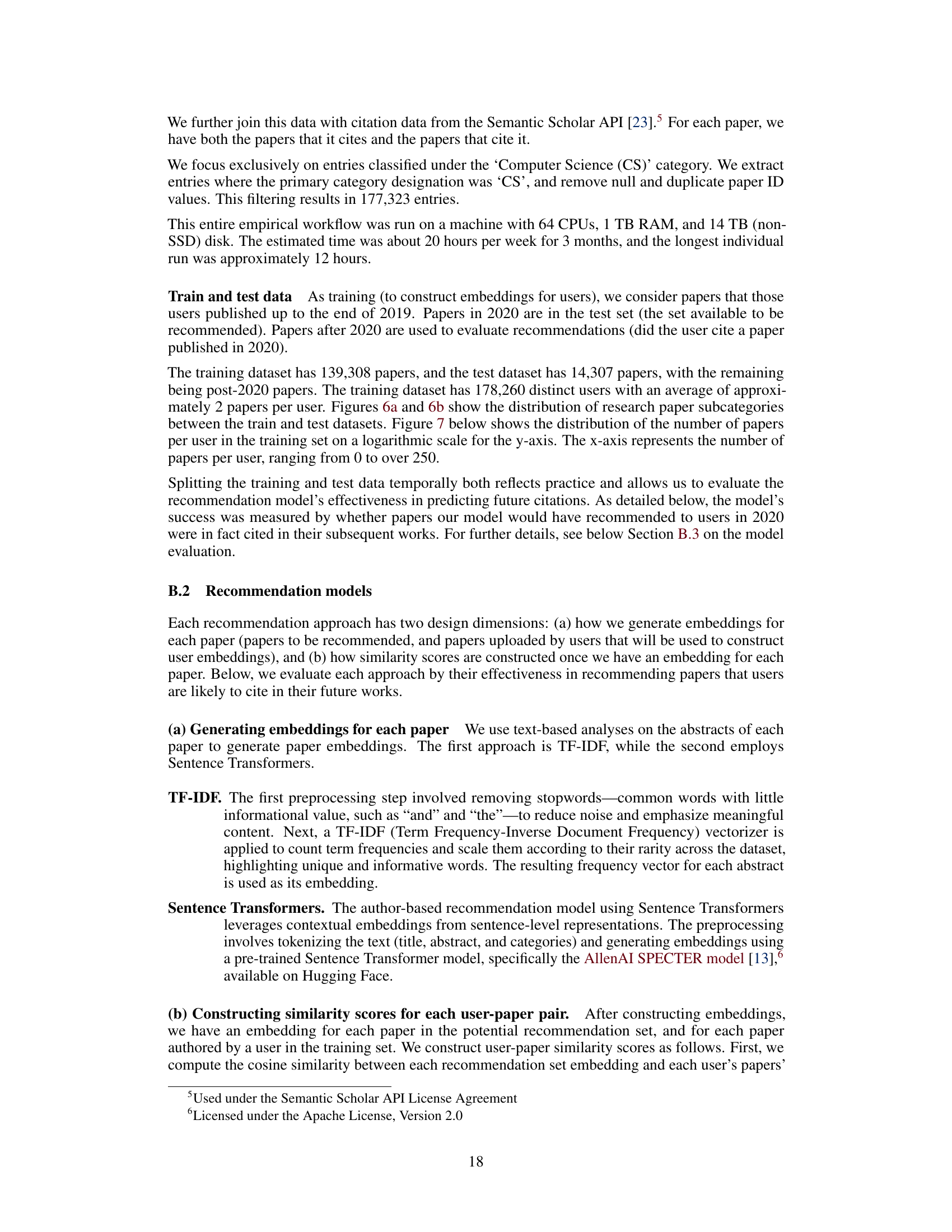

This figure shows the distribution of the number of papers per user in the training dataset using a logarithmic scale for the y-axis. The x-axis represents the number of papers per user. The data is visualized using a histogram, where the height of each bar represents the number of authors who have published that specific number of papers. The figure notes that the authors also conducted experiments with dot products instead of cosine similarity, but those results are not included in the figure due to similarity with the presented cosine similarity results.

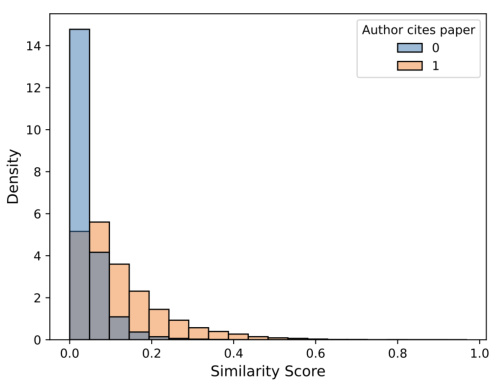

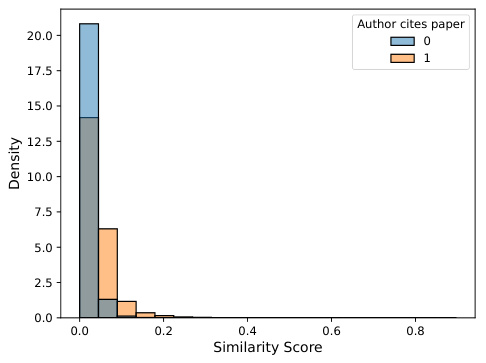

This figure shows the distribution of similarity scores for user-paper pairs, broken down by whether the user cited the paper in the future. The plot shows the probability density of similarity scores, conditioned on whether the user cited the paper. It uses data from the Max score, TF-IDF model, illustrating the relationship between predicted similarity and actual citation behavior.

This figure shows the distribution of similarity scores for papers that were cited (orange) versus those that were not cited (blue) by the user in the future. The figure demonstrates that the density for cited papers is higher at higher levels of similarity scores compared to non-cited papers, indicating that higher similarity scores are associated with a greater likelihood of citation.

This figure shows the distribution of similarity scores for papers that were cited versus those that were not cited by the user. The density for cited papers is higher at higher levels of similarity scores compared to non-cited papers.

This figure shows the distribution of similarity scores for papers that were cited (orange) versus those that were not cited (blue) by the user in the future, for the Max score TF-IDF model. The higher density for the cited papers at higher levels of similarity scores compared to non-cited papers suggests that the TF-IDF similarity scores are effective for predicting future citations.

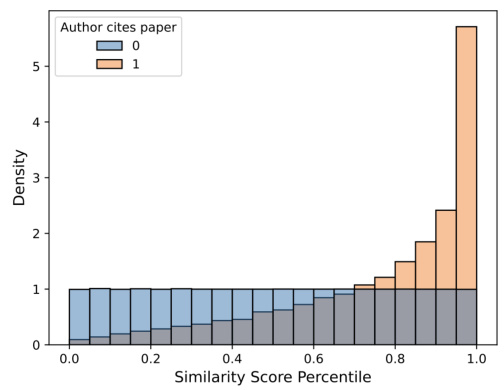

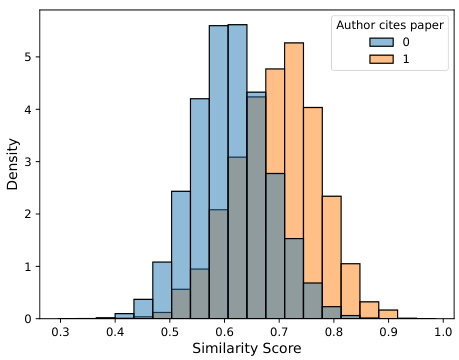

This figure shows the distribution of similarity scores for user-paper pairs, broken down by whether or not the user cited the paper in the future. The data is from the Max score, TF-IDF model. The figure shows two plots: (a) a histogram of similarity scores and (b) a histogram of similarity score percentiles. In both plots, the orange bars represent pairs where the user cited the paper, and the blue bars represent pairs where the user did not cite the paper. The figure illustrates that higher similarity scores are associated with a higher probability of citation.

This figure shows the distribution of similarity scores for user-paper pairs, broken down by whether or not the user cited the paper in the future. The data is from the Max score, TF-IDF model. The x-axis represents the similarity score, and the y-axis represents the density of scores for a given similarity score. Two distributions are shown: one for papers that were cited by the user and another for papers that were not cited. This visualization helps understand the relationship between the predicted similarity scores and the actual citation behavior of users.

This figure shows the distribution of similarity scores for papers that were cited (orange) versus those that were not cited (blue) by the user in the future. The density for cited papers is higher at higher levels of similarity scores compared to non-cited papers. The figure is accompanied by two sub-figures, one showing the distribution of similarity scores grouped by citation presence, and the other showing the distribution of similarity score percentiles grouped by citation presence. Both figures are generated using the Max score, TF-IDF model.

This figure shows the distribution of similarity scores for papers that were cited (orange) versus those that were not cited (blue) by the user in the future. It uses the max score TF-IDF model and shows that higher similarity scores are associated with higher probabilities of citation.

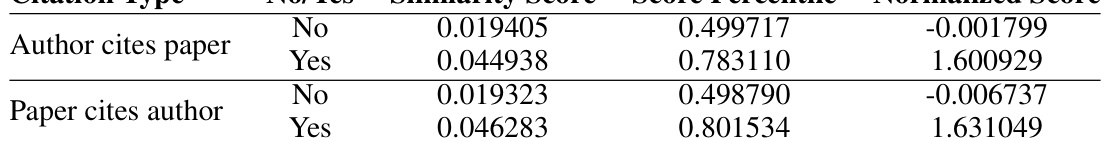

More on tables

This table shows the average similarity scores, score percentiles, and normalized scores obtained from the Max score TF-IDF model. The results are categorized by whether the user cited the paper in the future or if the paper cited the user. This allows for an analysis of how well the model predicts citations in both directions (user citing paper, paper citing user).

This table presents the results of logistic regression analyses performed to predict whether a user (i) cites a given paper (j) in the future, based on the similarity score (wij) between them. Four different models were used: TF-IDF and Sentence Transformer, each with max and mean score aggregation. The table shows the coefficients, standard error, z-value, p-value, and adjusted R-squared for each model. The statistically significant and positive coefficients for each model indicate a strong relationship between similarity scores and future citations.

This table shows the average similarity scores, score percentiles, and normalized scores from the Max score, Sentence transformer model. The results are categorized based on whether the user cited the paper in the future or whether the paper cited the user. Higher values indicate stronger similarity between the user and the paper, and are associated with a greater likelihood of citation in the future.

This table shows the results of a logistic regression to predict whether a user cites a paper. The model uses the maximum similarity score from the TF-IDF model. It includes the coefficient, standard error, z-value, p-value, and adjusted R-squared for the similarity score, score percentile, and normalized score.

This table shows the average similarity scores, score percentiles, and normalized scores from the Max score, Sentence Transformer model. The data is broken down by whether the author cited the paper in the future, or whether the paper cited the author. Higher scores indicate a stronger relationship between the similarity measure and citation presence, suggesting the model’s effectiveness in predicting future citations.

This table presents the results of a logistic regression model used to predict whether a user cites a paper. The model uses three different metrics derived from similarity scores (similarity score, score percentile, and normalized score) as predictor variables. The adjusted R-squared values indicate the goodness of fit for each model. The significant z-values and p-values show the predictive power of each of these variables in the model, indicating how well the model can predict citation likelihood based on each metric. The table belongs to the analysis of the arXiv recommendation engine and specifically evaluates the performance of a sentence transformer model in predicting citations.

This table presents the average similarity scores, percentiles, and normalized scores from the Mean score, Sentence Transformer model. The data is broken down by whether the user cited the paper in the future or if the paper cited the user. It shows the difference in these metrics between papers that were cited and those that were not.

This table presents the results of a logistic regression model used to predict whether a user will cite a specific paper. The model uses the mean similarity score, calculated using Sentence Transformer embeddings, as the predictor variable. The table shows the coefficient, standard error, z-value, p-value, and adjusted R-squared for each of three similarity score measures: raw similarity score, score percentile, and normalized score.

Full paper#