↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning models, even with similar accuracy, can produce vastly different predictions for the same input (Rashomon effect), leading to unreliable or unfair outcomes. This is particularly problematic in gradient boosting, a powerful but complex algorithm widely used in various applications. The Rashomon effect makes it hard to trust AI decisions and causes significant challenges in building fair and robust AI systems.

This research introduces RashomonGB, a new method to efficiently find and analyze these conflicting models. RashomonGB systematically analyzes the Rashomon effect in gradient boosting, providing theoretical derivations and an information-theoretic characterization. Empirically evaluated on various datasets, RashomonGB significantly improves the accuracy of predictive multiplicity estimates and facilitates better model selection under fairness constraints. Additionally, the study proposes effective techniques for mitigating predictive multiplicity, boosting the reliability and trustworthiness of gradient boosting models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical issue of predictive multiplicity in gradient boosting, a widely used machine learning algorithm. By providing a novel framework and technique (RashomonGB), it offers practical solutions for improving model selection and mitigating the risks associated with inconsistent predictions. This work opens new avenues for research in responsible machine learning and directly impacts the credibility and fairness of AI systems.

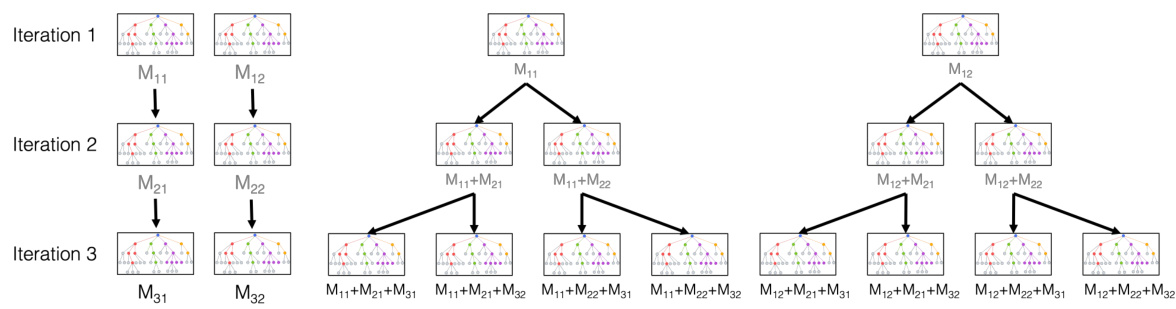

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the difference between standard gradient boosting and the proposed RashomonGB method. In gradient boosting, a sequence of weak learners (h1, …, hT) are trained iteratively to minimize the residual error. In contrast, RashomonGB constructs an empirical Rashomon set for each iteration (R1(H, S1, h1*, ε), …, RT(H, ST, hT*, ε)), where multiple models with similar performance are identified. The final model in RashomonGB is a combination of models selected from these empirical Rashomon sets.

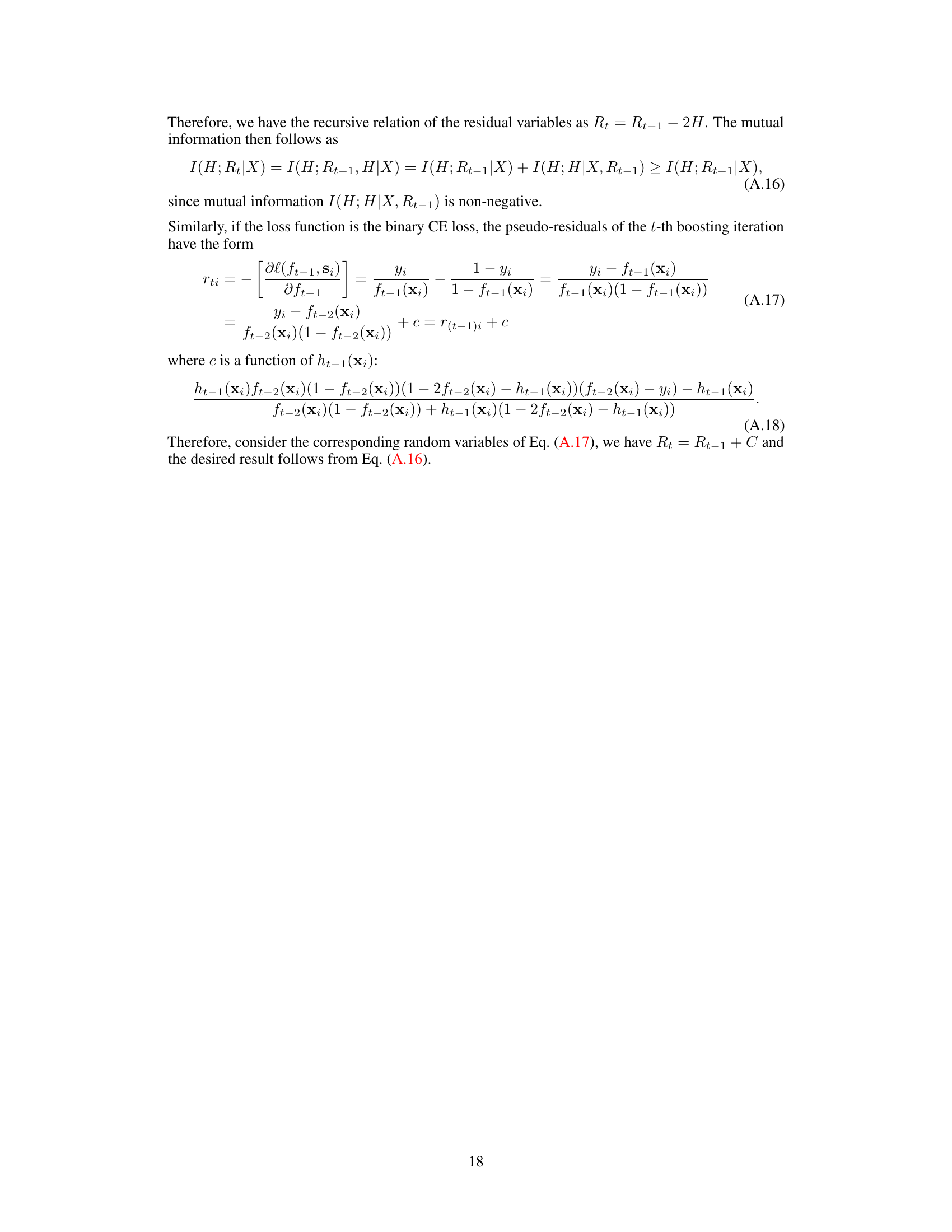

This table presents decision-based predictive multiplicity metrics, which quantify the conflicts in decisions made by competing models in a Rashomon set. Ambiguity measures the proportion of samples with conflicting decisions. Discrepancy represents the maximum number of decisions that could change by switching models within the Rashomon set. Disagreement calculates the probability of conflicting predictions for a given sample.

In-depth insights#

RashomonGB Intro#

RashomonGB, introduced in this research paper, tackles the challenge of predictive multiplicity in gradient boosting models. Predictive multiplicity, arising from the Rashomon effect, refers to the existence of multiple models with similar predictive performance but differing internal structures. This phenomenon poses risks to the credibility and fairness of machine learning models. RashomonGB offers a novel approach by systematically analyzing the Rashomon effect within gradient boosting, leveraging its iterative structure to efficiently explore the space of competing models. Information-theoretic analysis is used to characterize the impact of dataset properties on predictive multiplicity. The method is empirically evaluated on numerous datasets, demonstrating improved estimation of multiplicity metrics and effective model selection, even under fairness constraints. A key contribution is the framework for mitigating predictive multiplicity, enhancing the reliability and trustworthiness of gradient boosting predictions. The integration of information theory makes the approach unique and theoretically grounded, allowing for insights into data quality and its influence on model uncertainty.

Info-Theoretic Bounds#

Info-theoretic bounds, in the context of machine learning, offer a powerful lens for analyzing the Rashomon effect and predictive multiplicity. By leveraging concepts from information theory, such as mutual information, we can quantify the uncertainty inherent in the learning process and establish connections between data quality, model complexity, and the size of the Rashomon set. This approach moves beyond traditional statistical learning perspectives, providing a deeper understanding of the factors contributing to the existence of multiple high-performing models. A key advantage is the ability to formally bound the size of the Rashomon set, providing a probabilistic guarantee on the number of models satisfying a given performance threshold. This theoretical framework is particularly valuable in situations where the hypothesis space is vast (like in deep learning), and exhaustive exploration is computationally infeasible. Furthermore, by decomposing the mutual information, we can isolate the influence of data quality and inherent model uncertainty, leading to a more nuanced understanding of the Rashomon effect and its implications for responsible machine learning.

Model Selection#

Model selection is a crucial aspect of machine learning, especially when dealing with the Rashomon effect and predictive multiplicity. The Rashomon effect highlights the existence of multiple models with similar performance, posing challenges for selecting a single ‘best’ model. Traditional model selection metrics might not be sufficient in this context, because they often fail to account for the variety and characteristics of competing models. Fairness and interpretability concerns add another layer of complexity to model selection, requiring careful consideration of ethical implications. An effective model selection process should incorporate not just accuracy, but also considerations such as predictive multiplicity, fairness, and interpretability. The paper explores novel methods to address this challenge, such as using the RashomonGB technique to improve the identification and estimation of predictive multiplicity, and selecting models that fulfill fairness constraints. The exploration of various methods to mitigate predictive multiplicity, including model averaging and selective averaging techniques, further enhances the model selection process. Ultimately, model selection aims at a balance between optimal performance and responsible practices.

Multiplicity Metrics#

Predictive multiplicity, a phenomenon where multiple models achieve similar performance despite significant differences, necessitates robust metrics for evaluation. Decision-based metrics, such as ambiguity and discrepancy, quantify the extent of conflicting predictions across samples. Score-based metrics, like variance and viable prediction range (VPR), focus on the spread of prediction scores. The choice of metric depends on the specific goal; decision-based metrics highlight the impact on final decisions, while score-based metrics reveal the uncertainty inherent in the model predictions. Information-theoretic measures offer a principled way to connect dataset properties with the size and structure of the Rashomon set. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis needs multiple metrics to capture the multifaceted nature of predictive multiplicity.

Future Directions#

The “Future Directions” section of this research paper on the Rashomon effect in gradient boosting would ideally delve into several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis beyond gradient boosting to encompass other ensemble methods like adaptive boosting is crucial for broader applicability. The current work’s focus on gradient boosting is a strength, providing a deep understanding of that specific algorithm; however, generalizing these findings is paramount. Addressing the computational challenges posed by the large model sets generated by RashomonGB is vital. Exploring efficient data structures and algorithms to manage these sets would significantly enhance the practical utility of the approach. Finally, a key area to explore is adaptive model selection within the Rashomon set, potentially leveraging techniques from active learning to focus exploration and reduce computational overhead. Investigating the interplay between dataset properties, model complexity, and the size of the Rashomon set offers significant potential to optimize model selection for both accuracy and fairness. Developing practical guidelines on selecting the optimal Rashomon parameter (€) based on dataset characteristics and desired levels of predictive multiplicity would be a significant contribution, bridging the gap between theoretical understanding and practical application.

More visual insights#

More on figures

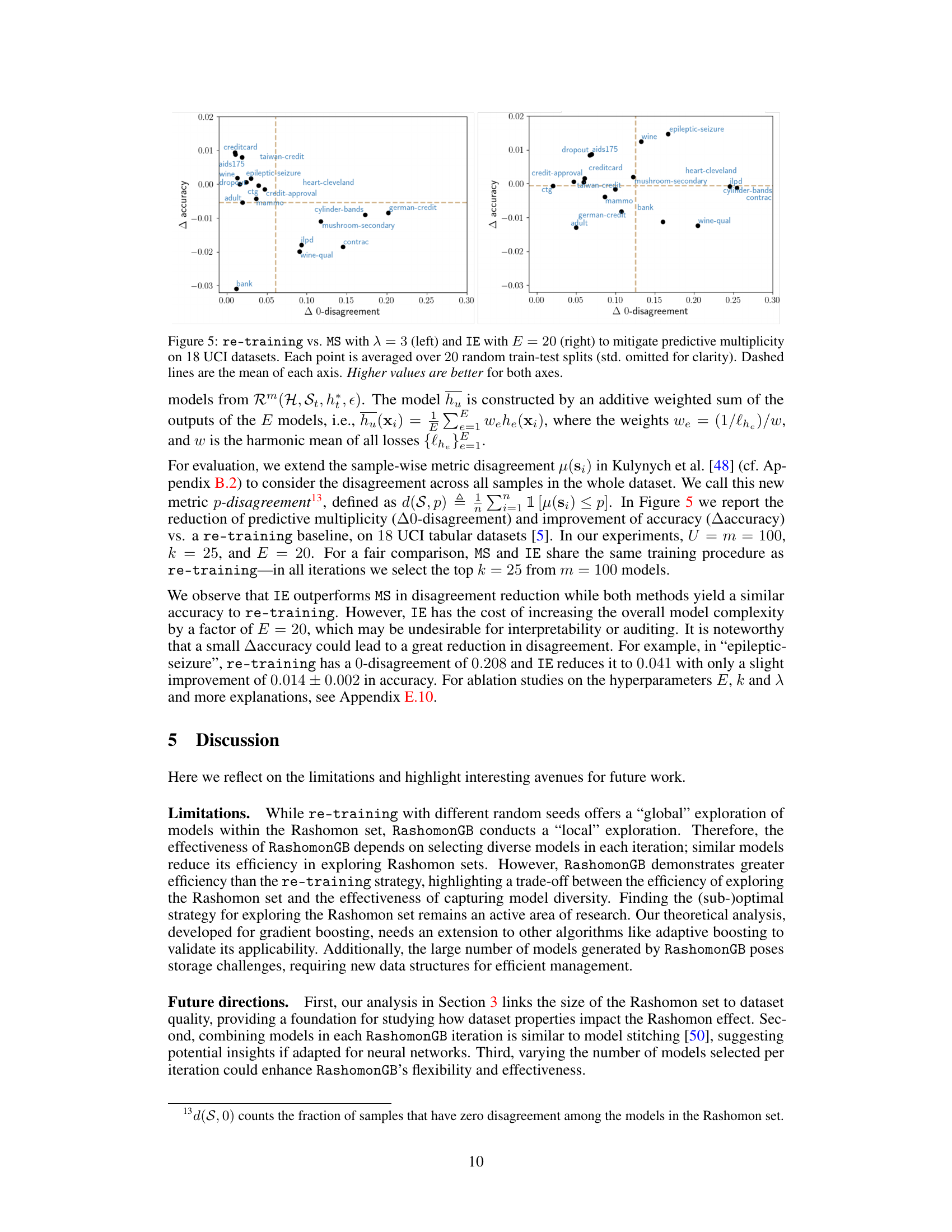

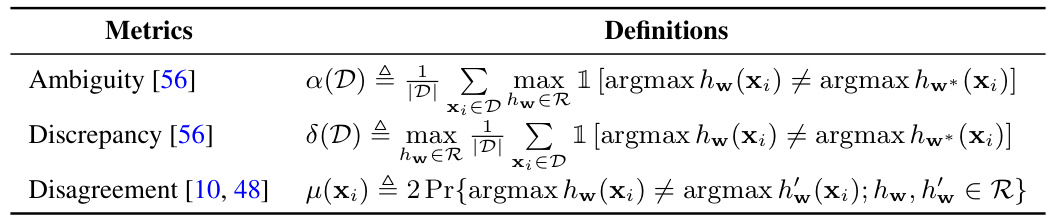

This figure shows the results of a gradient boosting experiment on a binary classification task. The x-axis represents the boosting iteration number (1 through 10). The y-axis on the left shows the loss (CE loss) and accuracy, while the y-axis on the right shows the conditional entropy g(Rt|X) and the VPR (Viable Prediction Range), a measure of predictive multiplicity. The plot demonstrates that as the number of boosting iterations increases, both the conditional entropy of the residuals and the predictive multiplicity (as measured by VPR) also increase. This observation supports Proposition 1 of the paper, which establishes a theoretical relationship between the size of the Rashomon set and data quality using mutual information.

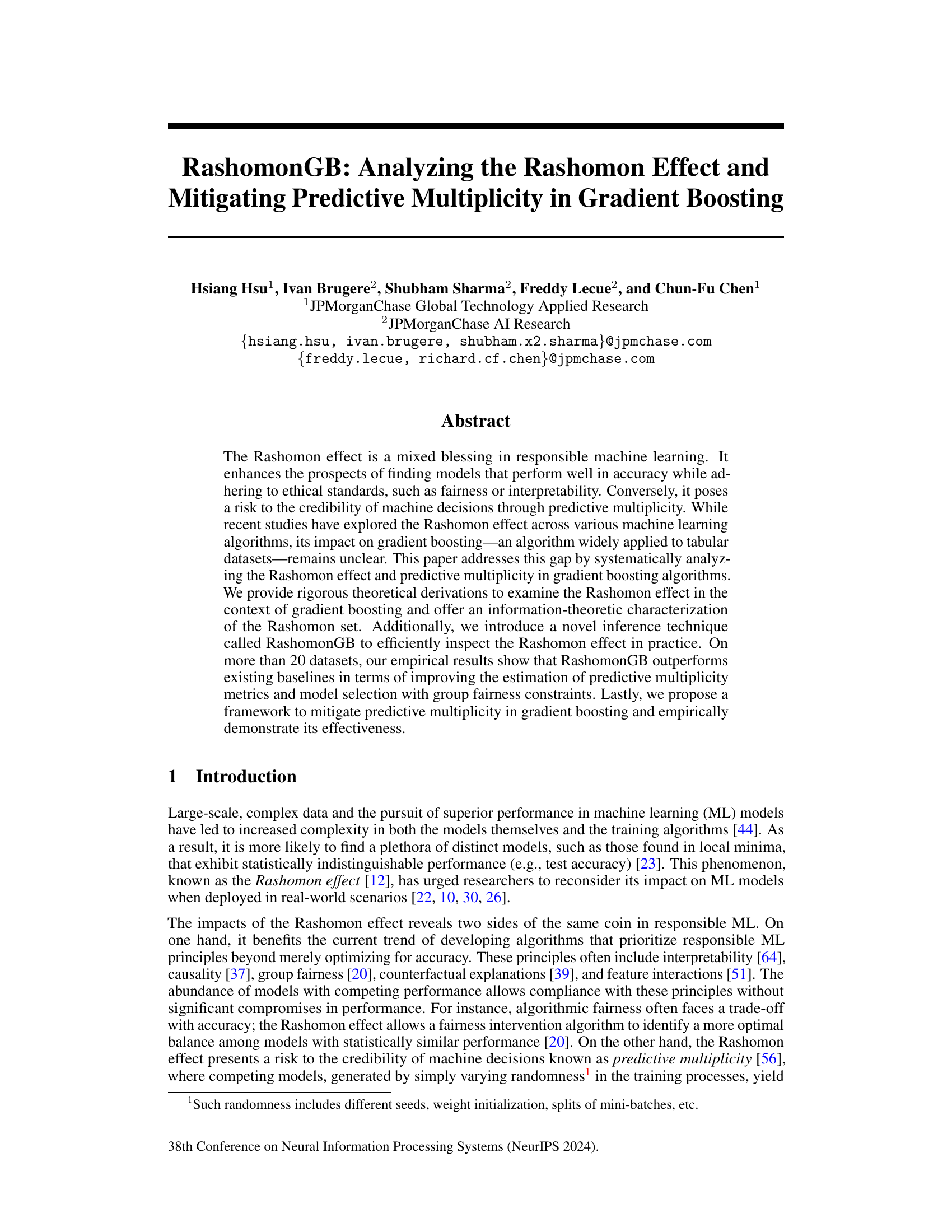

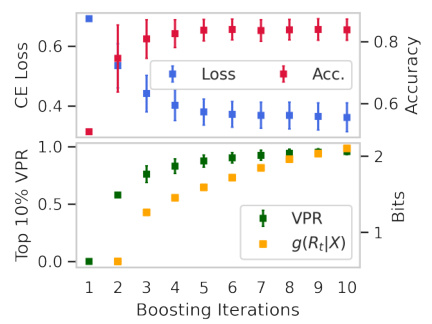

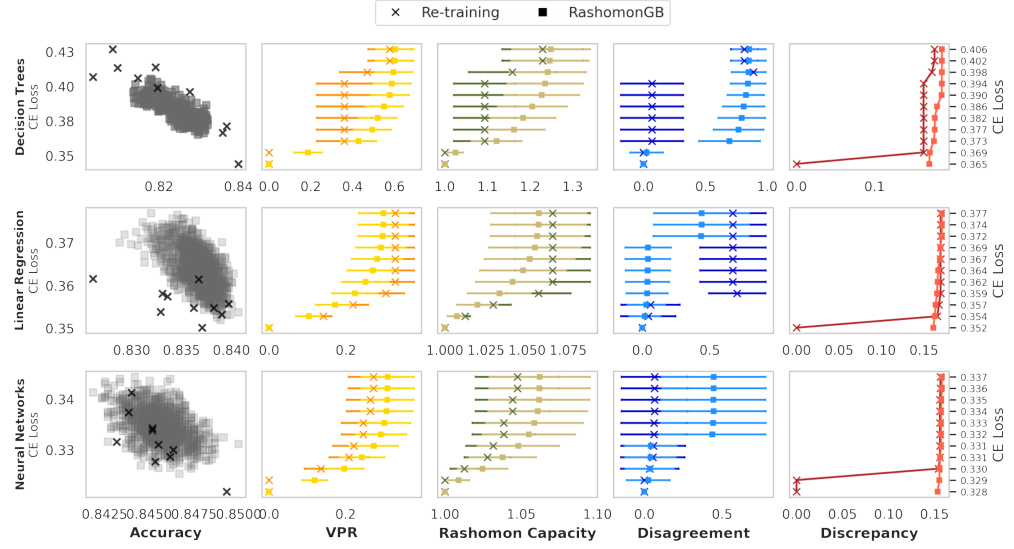

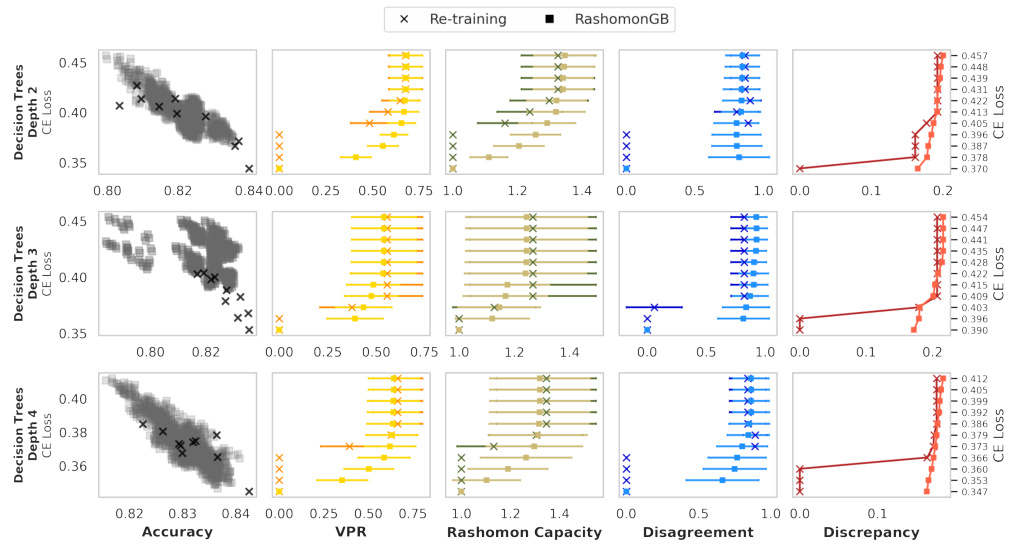

The figure compares two methods for estimating predictive multiplicity metrics: re-training and RashomonGB. It shows that RashomonGB, by generating a larger number of models within the Rashomon set (models with similar performance), provides more accurate estimates of these metrics, even under the same loss deviation constraints. The leftmost column displays the accuracy vs. loss of the models generated by each method. The other four columns show the estimates of four different predictive multiplicity metrics (VPR, Rashomon Capacity, Disagreement, Discrepancy) for different loss deviation thresholds.

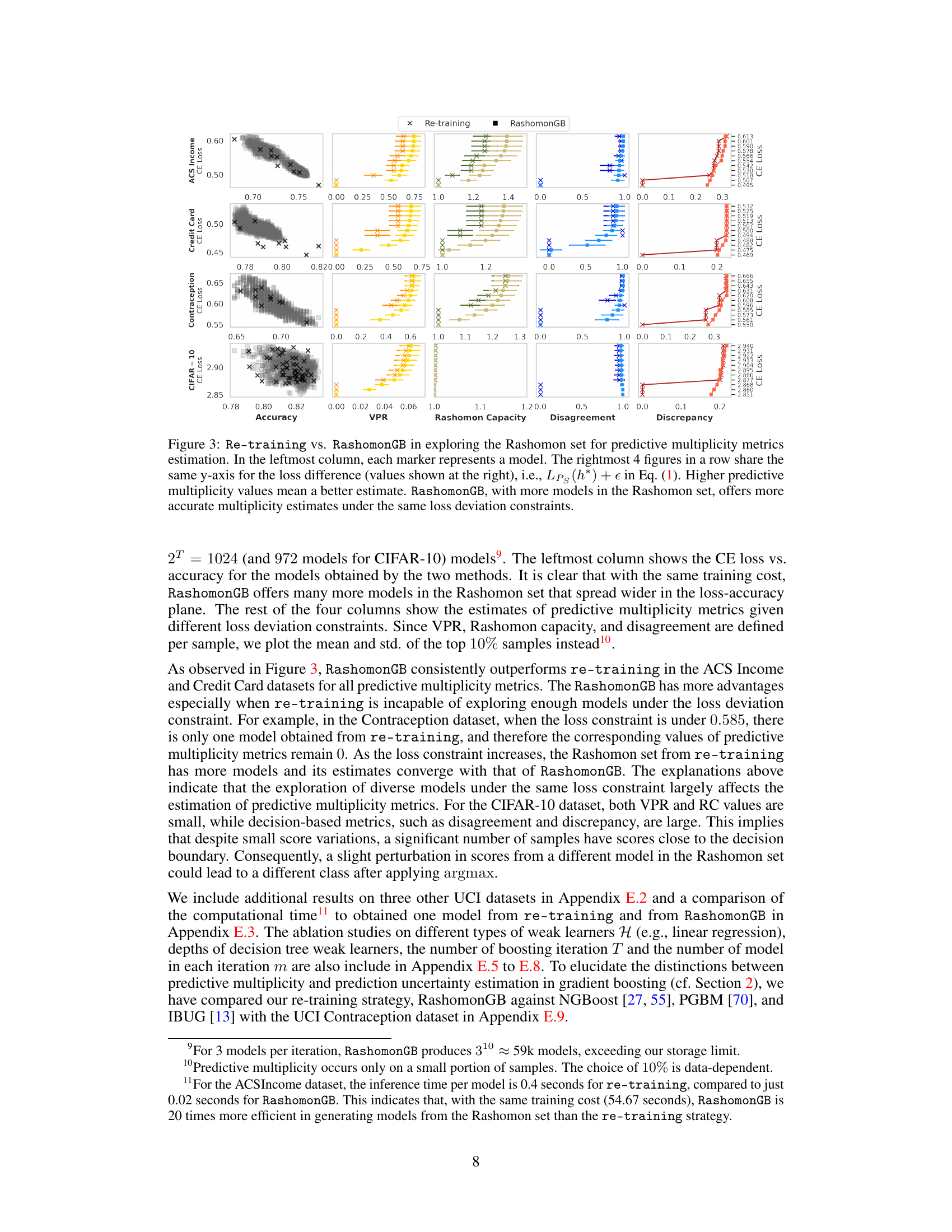

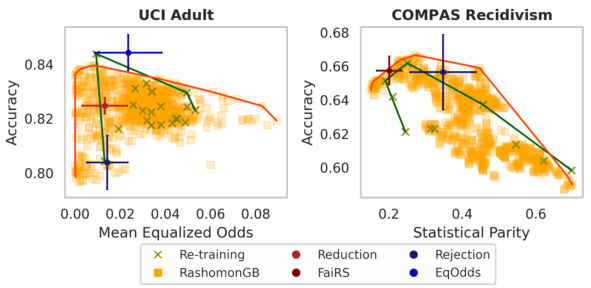

This figure compares the fairness-accuracy trade-off achieved by re-training and RashomonGB on the UCI Adult and COMPAS datasets. Each point represents a model, with the x-axis showing the group fairness metric (Mean Equalized Odds for UCI Adult and Statistical Parity for COMPAS) and the y-axis showing accuracy. A model that is both accurate and fair will be located in the top-left corner of the plot. The figure shows that RashomonGB provides models with better fairness-accuracy trade-offs (closer to the top left) than re-training, especially for the COMPAS dataset.

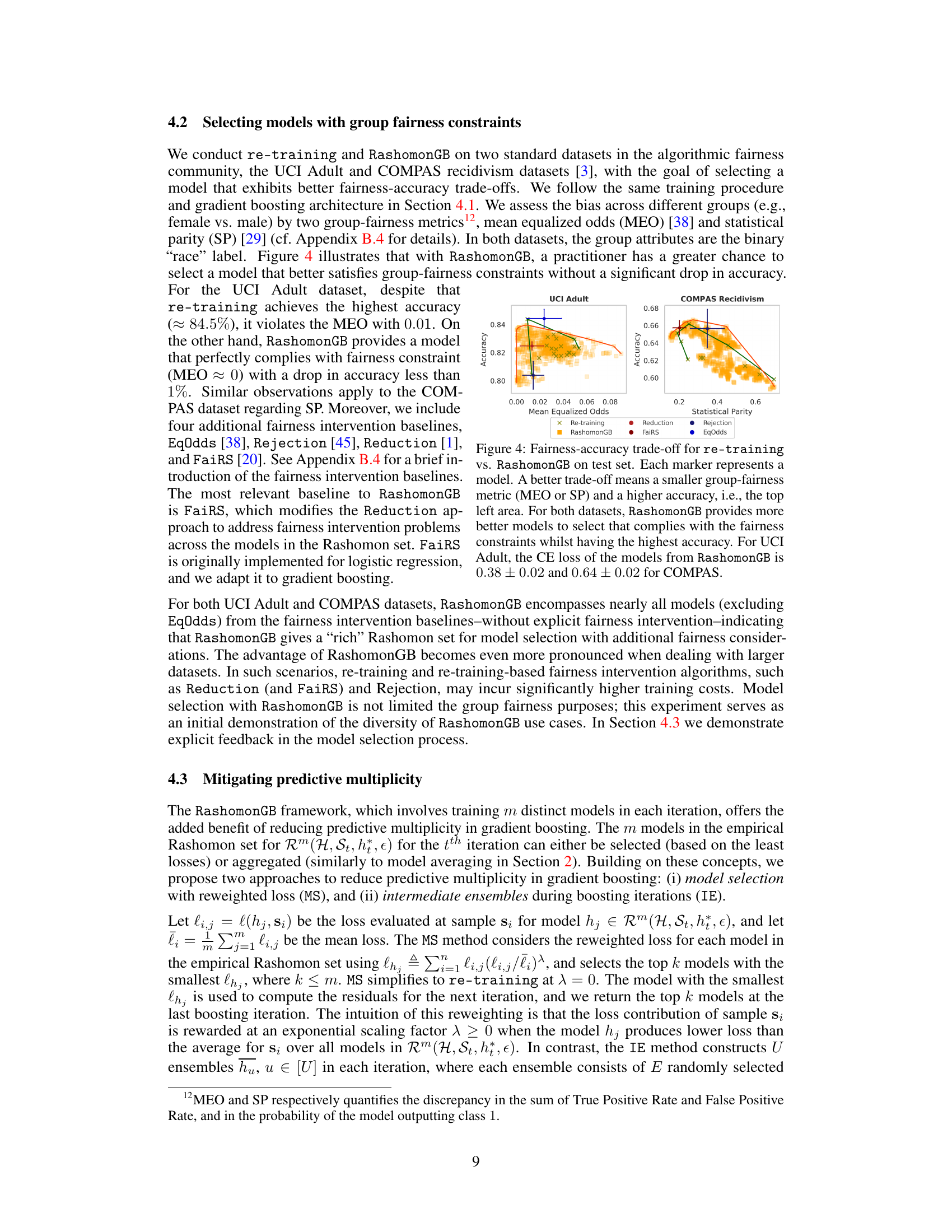

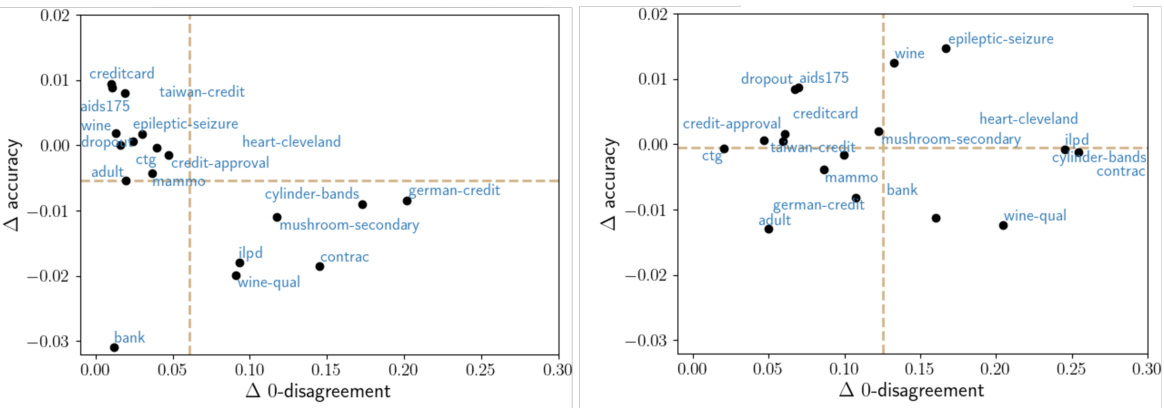

This figure compares the performance of two methods (MS and IE) for mitigating predictive multiplicity against a re-training baseline across 18 UCI datasets. The x-axis represents the reduction in 0-disagreement (a metric of predictive multiplicity), and the y-axis shows the improvement in accuracy. Each point represents an average over 20 train-test splits, and higher values on both axes indicate better performance. MS uses a model selection technique with reweighted losses, while IE uses intermediate ensembles during boosting iterations. The dashed lines represent the average performance across all datasets for each method.

This figure illustrates the difference between standard gradient boosting and the proposed RashomonGB method. Gradient boosting iteratively builds a model by adding weak learners. RashomonGB extends this by incorporating multiple weak learners at each iteration, creating an ensemble of models at each step. The final RashomonGB model encompasses exponentially more model variations compared to standard gradient boosting, enabling a more comprehensive exploration of the Rashomon set.

This figure compares the performance of two methods, re-training and RashomonGB, in estimating predictive multiplicity metrics. The leftmost panel shows the accuracy vs. loss for individual models generated by each method. The remaining panels show the estimated values of four predictive multiplicity metrics (VPR, Rashomon Capacity, Disagreement, Discrepancy) for different loss thresholds. RashomonGB consistently provides better estimates because it explores a larger set of models within the Rashomon set.

This figure compares the performance of the RashomonGB method against a re-training baseline in estimating predictive multiplicity metrics. The leftmost panel shows the accuracy and loss for individual models generated by each method. The remaining panels display four predictive multiplicity metrics (VPR, Rashomon Capacity, Disagreement, Discrepancy) calculated for each method across a range of loss difference thresholds. The figure demonstrates that RashomonGB, despite having the same training cost as re-training, consistently provides more accurate estimations of these metrics due to its ability to explore a richer set of models within the Rashomon set.

This figure shows the results of an ablation study on the number of boosting iterations (T) in the Rashomon gradient boosting algorithm. The left panel displays the relationship between accuracy and cross-entropy (CE) loss for models generated at different iterations (T = 1 to 10). The right panel shows how the percentage of models within the Rashomon set changes as the CE loss constraint varies, for different boosting iterations. It illustrates that as the number of boosting iterations increases, the percentage of models in the Rashomon set also increases, especially at lower loss constraints.

This figure compares the performance of two methods, Re-training and RashomonGB, in estimating predictive multiplicity metrics. It shows that RashomonGB, despite having the same training cost, provides a much richer set of models within the Rashomon set, leading to significantly more accurate estimations of the metrics (VPR, Rashomon Capacity, Disagreement, Discrepancy) compared to Re-training, especially when the loss deviation constraint is relatively tight.

This figure compares the performance of two methods for estimating predictive multiplicity metrics: re-training and RashomonGB. The leftmost column shows the loss and accuracy for each model generated by the two methods. The remaining columns present four predictive multiplicity metrics (VPR, Rashomon Capacity, Disagreement, Discrepancy) calculated using the models from each method. The y-axis represents the loss difference, and higher values indicate better estimates of multiplicity. The figure demonstrates that RashomonGB generally provides more accurate estimates of these metrics compared to re-training, especially with tighter loss constraints.

This figure compares the performance of two methods for estimating predictive multiplicity metrics: re-training and RashomonGB. The leftmost column shows the accuracy and loss for each model obtained by the two methods. The other four columns show four different predictive multiplicity metrics (VPR, Rashomon Capacity, Disagreement, Discrepancy). The figure demonstrates that RashomonGB, while having the same training cost, provides more models within the Rashomon set leading to more accurate estimates of predictive multiplicity compared to the re-training method. The y-axis for the four rightmost plots represents the loss difference (Lps(h*) + ∈). Higher values in the rightmost four columns show better estimates of predictive multiplicity.

This figure compares the performance of two methods, re-training and RashomonGB, in estimating predictive multiplicity metrics. The leftmost panel shows the accuracy and loss for each model produced by each method. The other four panels show four different predictive multiplicity metrics (VPR, Rashomon Capacity, Disagreement, and Discrepancy) calculated for different loss thresholds. Each point in these panels represents a single model, and the plots demonstrate that RashomonGB tends to produce a richer set of models in the Rashomon set, allowing for more precise estimations of the metrics.

This figure compares the performance of two methods, re-training and RashomonGB, in estimating predictive multiplicity metrics. The leftmost panel shows the test accuracy and loss for individual models generated by each method. The remaining four panels display four different predictive multiplicity metrics (VPR, Rashomon Capacity, Disagreement, Discrepancy) for a range of loss difference thresholds (epsilon). The results demonstrate that RashomonGB, by generating a more diverse set of models within the Rashomon set, yields more accurate estimates of predictive multiplicity compared to the standard re-training approach, especially when the loss constraint is tighter and fewer models are found using the re-training approach.

This figure compares the performance of RashomonGB and the re-training method in estimating predictive multiplicity metrics. The leftmost column shows the accuracy and loss for each model generated by each method. The remaining four columns display four different predictive multiplicity metrics (VPR, Rashomon Capacity, Disagreement, Discrepancy) calculated for both methods, under various loss difference constraints. The plot demonstrates that RashomonGB produces significantly better estimates of these metrics compared to the re-training method, especially when the loss constraint is tighter, due to its ability to generate a more diverse range of models within the Rashomon set.

More on tables

This table presents a summary of score-based predictive multiplicity metrics. These metrics focus on the spread or variability of predicted scores (rather than the final classification decisions) across multiple models within the Rashomon set. It includes mathematical definitions for standard deviation/variance, viable prediction range (VPR), and Rashomon capacity (RC). Each metric offers a different perspective on the extent of score variability and the degree to which model predictions diverge.

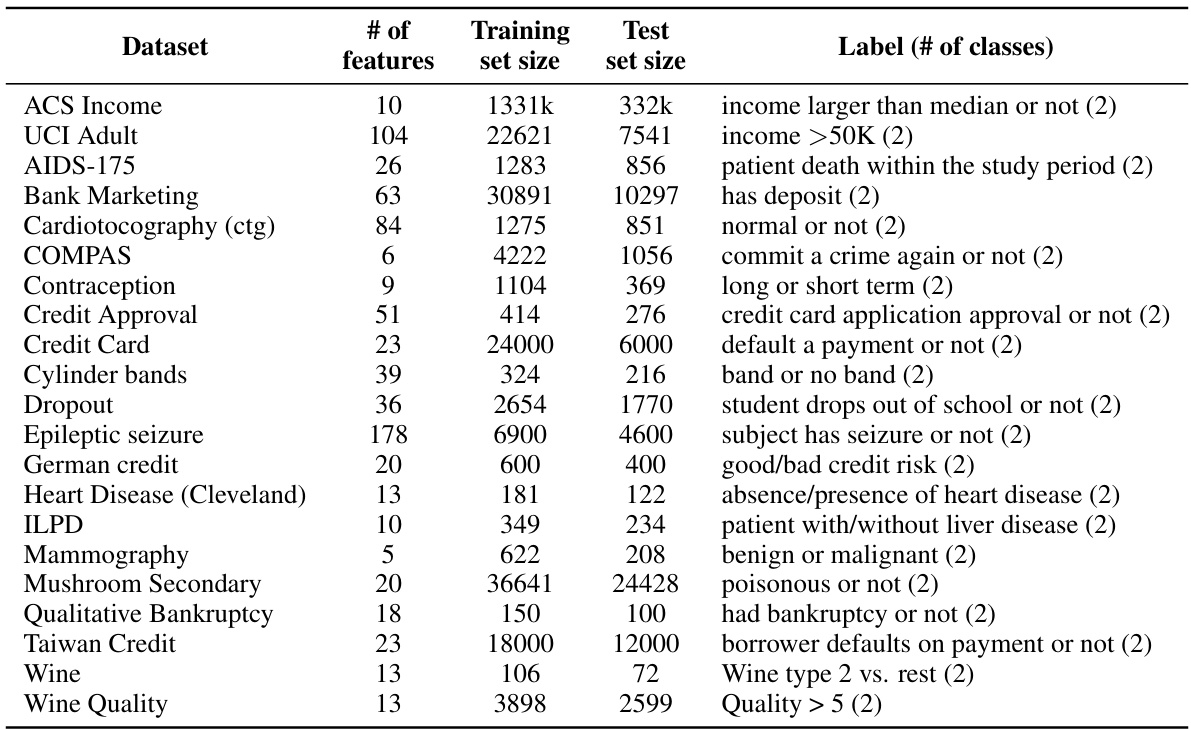

This table lists 18 tabular datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it provides the number of features, the size of the training and test sets, and a description of the label (outcome variable). The datasets cover a variety of domains including medicine, finance, and social science, and are chosen to evaluate different aspects of predictive multiplicity and responsible machine learning.

This table compares the training time and the time needed to obtain one model using the retraining and RashomonGB methods. The experiment used decision trees as weak learners with 10 iterations and 10 models in each iteration. The experiment was repeated 3 times using different random seeds to obtain the mean and standard deviation of the time for each dataset, providing a statistical measure of the variability.

Full paper#