↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world applications involve reward allocation among multiple agents where the reward distribution is unknown or partially known. This poses a challenge to cooperative game theory, as many solutions require complete knowledge of reward functions. Learning the core, which represents the set of stable allocations, is crucial, but existing methods struggle in the face of uncertainty and bandit feedback, where agents only observe the reward of their own actions.

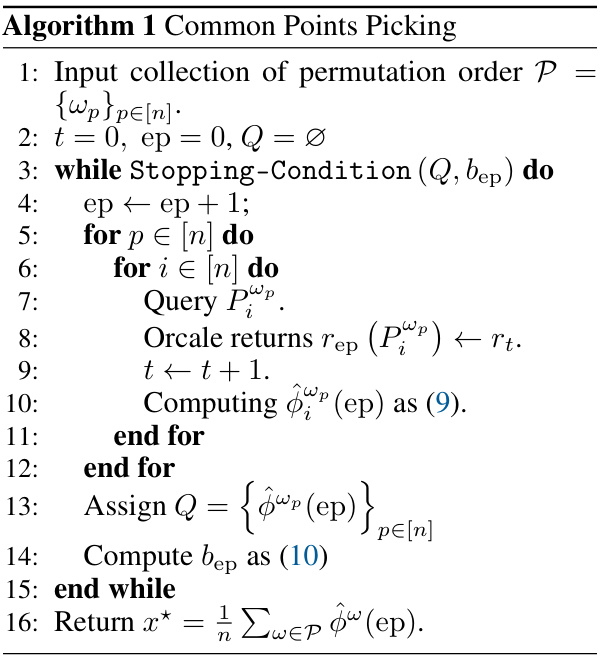

This paper tackles this challenge by focusing on learning the ’expected core’, a solution concept robust to uncertainty. The researchers propose a new algorithm, Common-Points-Picking, specifically designed for strictly convex games. This algorithm efficiently estimates the expected core by querying the rewards of specific coalitions, leveraging the game’s structure and employing a novel extension of the hyperplane separation theorem. The algorithm is proven to converge with high probability using a polynomial number of samples, offering a practical and theoretically sound solution for scenarios where reward distributions are unknown.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on reward allocation in multi-agent systems and cooperative game theory. It addresses the challenge of learning stable allocations in stochastic games with unknown reward distributions, a common and realistic scenario. The proposed algorithm and theoretical analysis offer practical solutions for real-world applications and opens new avenues for research in core learning and bandit optimization.

Visual Insights#

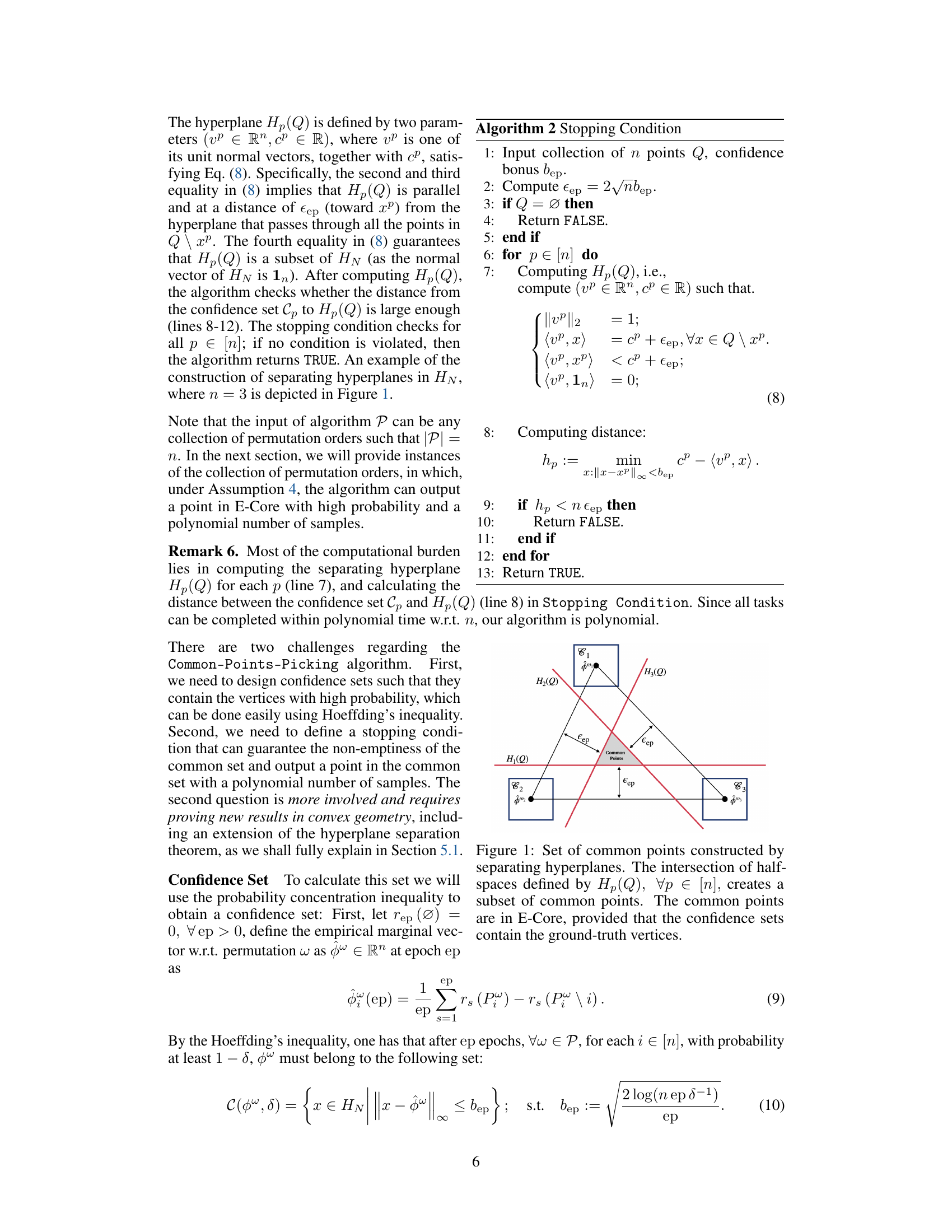

This figure illustrates the geometric intuition behind the Common-Points-Picking algorithm. It shows how, by finding separating hyperplanes for each confidence set, the algorithm can identify a region (the shaded triangle) representing the common points which are guaranteed to be in the expected core (E-Core). The key is that the confidence sets (squares) must be small enough relative to the distance between the hyperplanes to ensure that the intersection of the half-spaces is not empty.

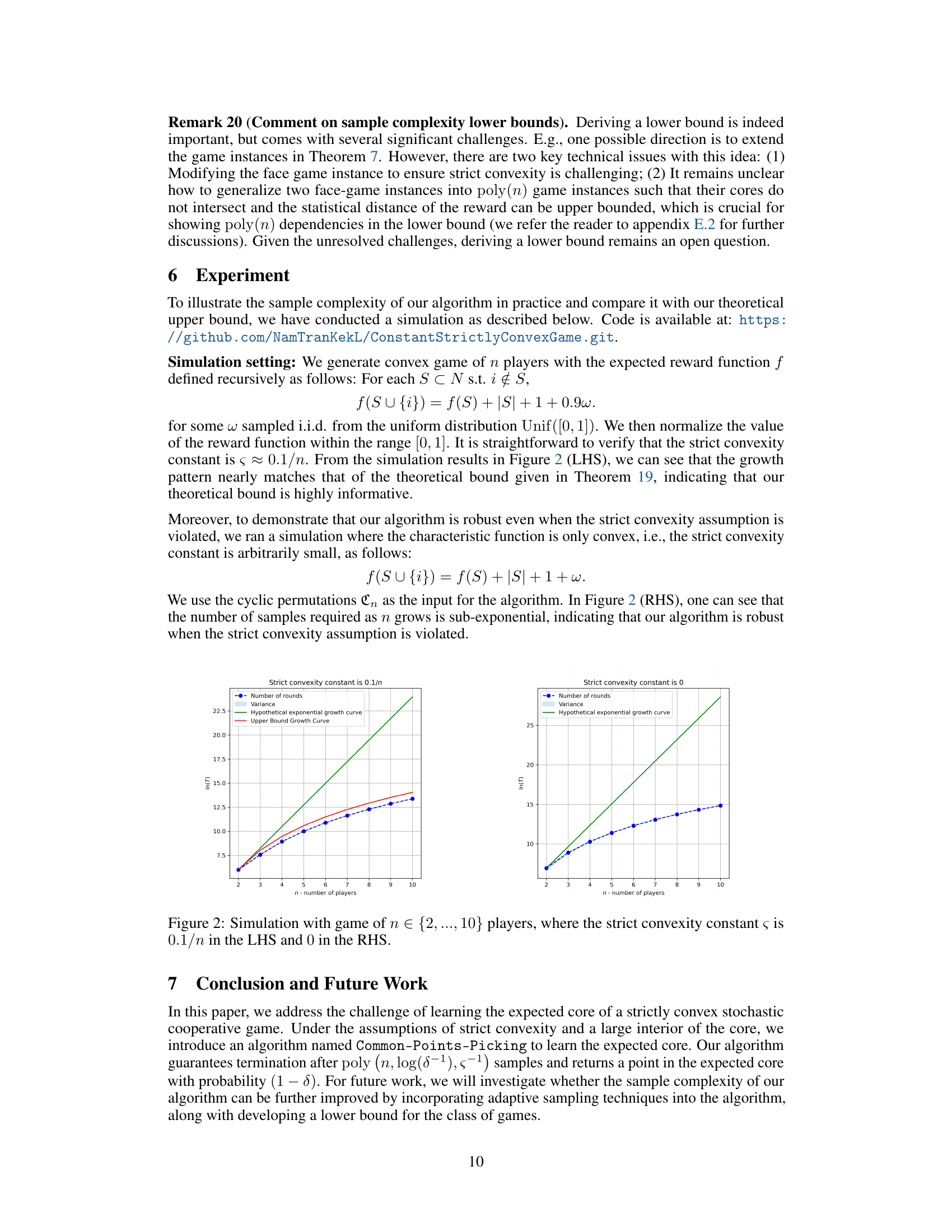

This table presents simulation results for games with varying numbers of players (n) and different strict convexity constants (s). It demonstrates the relationship between the number of samples required by the Common-Points-Picking algorithm and the number of players, under conditions of strict convexity and its absence. The LHS shows results for games with a strict convexity constant of 0.1/n, while the RHS shows results for games without strict convexity (s=0). The purpose is to empirically validate the algorithm’s efficiency and robustness in learning the expected core, comparing its performance against the theoretical upper bounds.

In-depth insights#

Expected Core Learning#

Expected core learning tackles the challenge of computing stable reward allocations in cooperative games where the reward distribution is uncertain. Unlike traditional core computation which assumes full knowledge of the reward function or distribution, this approach focuses on learning the core in expectation. This is crucial as it addresses the limitations of deterministic game theory in real-world applications with inherent uncertainty. The core itself represents the set of allocations where no coalition has an incentive to deviate. The problem’s complexity stems from handling the stochasticity of rewards, demanding novel techniques beyond standard optimization methods. Algorithms for expected core learning must efficiently use limited reward observations to approximate the expected core, often needing to incorporate probabilistic considerations and statistical guarantees. The field is rich with theoretical challenges concerning convergence rates, sample complexity, and the impact of assumptions like strict convexity on the algorithm’s efficacy. Practical applications span diverse domains including multi-agent reinforcement learning and explainable AI, where understanding stable reward sharing is critical for efficient cooperation and meaningful interpretation of model outputs.

Bandit Feedback Core#

In the context of cooperative game theory, the concept of a “Bandit Feedback Core” introduces a novel challenge to reward allocation. The core, representing a set of stable allocations, is typically calculated assuming complete knowledge of the reward function. However, in many real-world scenarios, this information is unavailable. Bandit feedback simulates this uncertainty, where an agent only observes the reward of its chosen coalition, not the rewards of all possible coalitions. This partial information significantly complicates the task of learning the core, demanding efficient algorithms capable of converging to a stable allocation despite the inherent uncertainty. The development of algorithms for learning the core under bandit feedback requires addressing the exploration-exploitation dilemma and overcoming the challenge of incomplete information. A successful algorithm must balance the need for exploration (trying out different coalitions) with exploitation (focusing on those seemingly optimal). This is a complex problem with potential implications for a wide range of cooperative multi-agent systems and applications.

Convex Game Analysis#

In the hypothetical “Convex Game Analysis” section, a deep dive into the mathematical properties of convex games would be expected. This would likely involve exploring the core concept, focusing on its existence, uniqueness, and computational aspects for various types of convex games. The core, a key solution concept in cooperative game theory, represents stable allocations where no coalition has an incentive to deviate. The analysis might delve into the relationship between the core and other solution concepts like the Shapley value, demonstrating how they complement each other in providing insights into fair resource allocation. Furthermore, the analysis would likely showcase the use of algorithms and computational techniques to find core solutions, considering the impact of computational complexity and efficiency. Specific examples of convex game applications, such as resource allocation or cost-sharing problems, could be used to illustrate practical scenarios. The limitations of relying solely on core analysis, perhaps due to its potential emptiness or the complexity of computation for large games, would also be addressed. Finally, the section could conclude by highlighting avenues for future research, including exploring more sophisticated approaches to analyzing non-convex games, extending the analysis to dynamic or stochastic games, and developing computationally tractable methods for solving practical problems.

Sample Complexity#

The sample complexity analysis is crucial for evaluating the efficiency and practicality of any algorithm that learns from data. This paper focuses on the number of samples needed to guarantee that the algorithm finds a point in the expected core with high probability. The analysis hinges on the algorithm’s ability to find a common point within several confidence sets. The size of these confidence sets is directly related to the number of samples; more samples lead to smaller sets and higher probability of finding a common point. A key innovation is a novel extension of the hyperplane separation theorem, enabling the analysis of the algorithm’s finite sample performance. The strict convexity of the game is also a critical factor, ensuring the core is full dimensional, facilitating the learnability. The theoretical findings are supported by experimental simulations demonstrating a near-match between the theoretical bound and empirical observations. However, the paper acknowledges limitations in establishing lower bounds on sample complexity, highlighting a direction for future research. The overall analysis offers valuable insights into the interplay between sample size, algorithm design, and the properties of the game.

Future Research#

The paper’s ‘Future Research’ section would ideally delve into several key areas. Extending the algorithm to handle non-strictly convex games is crucial, as strict convexity is a strong assumption limiting real-world applicability. Exploring alternative ways to address the bandit feedback setting, perhaps by incorporating more sophisticated sampling techniques or leveraging techniques from online learning, warrants investigation. Developing theoretical lower bounds on sample complexity is necessary to better understand the algorithm’s efficiency and limitations. Finally, empirical evaluation on diverse real-world applications (beyond the simulations presented) is critical to assess the algorithm’s practicality and robustness in various scenarios, particularly those with noisy or incomplete data. Addressing these points would significantly enhance the paper’s contribution to the field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure shows two graphs. Each graph plots the natural logarithm of the number of rounds (T) against the number of players (n) for a cooperative game. The left-hand side (LHS) graph represents a strictly convex game where the strict convexity constant is 0.1/n. The right-hand side (RHS) graph represents a convex game where the strict convexity constant is 0. Both graphs include the variance and growth curves for reference. The LHS graph demonstrates that the algorithm’s sample complexity grows polynomially. The RHS graph shows that even when strict convexity is not satisfied, the algorithm remains robust, with sub-exponential sample complexity.

This figure shows the results of simulations performed to evaluate the sample complexity of the proposed Common-Points-Picking algorithm. The left-hand side (LHS) displays results for games where the strict convexity constant (s) is 0.1/n, while the right-hand side (RHS) shows results for games with s=0 (i.e., only convex). The x-axis represents the number of players (n), and the y-axis represents the number of samples required. The plots demonstrate how the number of samples scales with the number of players under different convexity conditions. The results suggest that the algorithm’s sample complexity grows sub-exponentially even when the strict convexity condition is relaxed.

Full paper#