↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) often struggle with catastrophic forgetting during sequential task learning. Existing parameter-efficient methods mainly focus on mitigating forgetting but often neglect knowledge transfer. This limits their ability to effectively learn new tasks and generalize well.

This paper introduces LB-CL, a novel parameter-efficient approach. LB-CL cleverly injects knowledge from previous tasks by analyzing low-rank matrix parameters’ sensitivity and injecting the knowledge into new tasks. To prevent forgetting, it maintains the orthogonality of each task’s low-rank subspace using gradient projection. Experiments show LB-CL significantly outperforms existing methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in both knowledge transfer and mitigating forgetting. This provides a significant advance in parameter-efficient continual learning for LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel parameter-efficient approach for continual learning in LLMs, a critical challenge in the field. The method significantly improves model performance and reduces forgetting, offering a practical solution for training LLMs on multiple tasks sequentially. The findings open new avenues for improving LLM adaptability and pave the way for more robust and versatile AI systems.

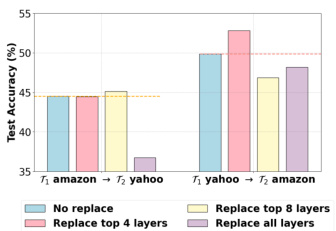

Visual Insights#

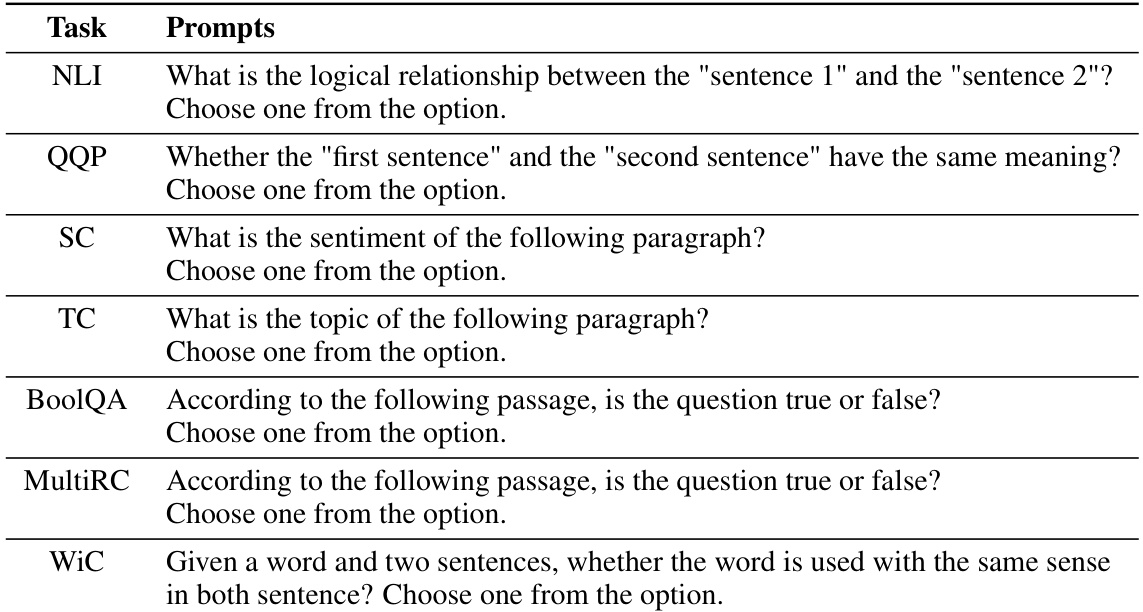

This figure shows the test accuracy on tasks T1 and T2 after training on T2 with different layer replacement strategies. The x-axis represents the task order (T1 -> T2) and the replacement strategy applied. T1 represents either the Amazon Reviews or Yahoo Answers dataset, and T2 represents the other. The y-axis shows the test accuracy. It demonstrates the impact of transferring knowledge from a previously learned task (T1) to a new task (T2) by selectively replacing layers in T2’s LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) parameters with those from T1. The results indicate that replacing certain layers from T1’s LoRA parameters can improve performance on both tasks.

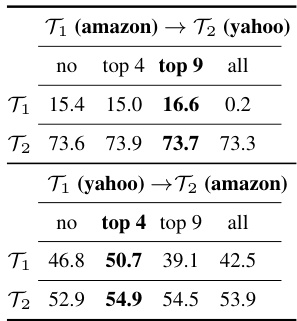

This table presents the results of an experiment designed to investigate the impact of replacing layers from a previously learned task’s LoRA-based layers during the initialization of a new task’s LoRA layers. It shows the testing accuracy for both the old task (T₁) and the new task (T₂) under different layer replacement strategies. The ’no replace’ column indicates the performance without any layer replacement. The other columns (’top 4’, ’top 9’, ‘all’) represent replacing the top 4, top 9, and all layers, respectively. The highest accuracy for both tasks is highlighted in bold, indicating the best replacement strategy.

In-depth insights#

Parameter-Efficient CL#

Parameter-efficient continual learning (CL) addresses the challenge of training large language models (LLMs) on multiple tasks sequentially without catastrophic forgetting or excessive computational costs. Existing methods often struggle to balance knowledge transfer between tasks and preventing the loss of previously learned information. Parameter-efficient approaches aim to overcome this limitation by focusing on updating only a small subset of the model’s parameters, thus reducing computational needs. This approach becomes crucial when dealing with LLMs because they contain numerous parameters that make full fine-tuning for each new task computationally expensive. Effective parameter-efficient CL techniques involve strategic parameter selection and optimization methods to minimize forgetting while maximizing knowledge retention and transfer across tasks. The design of such methods needs careful consideration of how to leverage information from previous tasks during the training of new tasks, while simultaneously preventing interference with already learned knowledge. Successful methods often incorporate mechanisms like low-rank matrix updates or orthogonal subspace learning, which allows for parameter-efficient fine-tuning without sacrificing model performance. The goal is to achieve a balance between model efficiency and continual learning performance, allowing for the efficient adaptation of LLMs to changing tasks without sacrificing prior knowledge.

Knowledge Transfer#

The concept of ‘knowledge transfer’ is central to the paper’s approach to parameter-efficient continual learning. The authors don’t explicitly use the term “knowledge transfer” as a heading, but it’s the underlying mechanism driving their method. They leverage sensitivity analysis to pinpoint knowledge-specific parameters within low-rank matrices from previously learned tasks. This allows them to selectively initialize these parameters in new tasks, effectively transferring relevant knowledge and avoiding catastrophic forgetting. The sensitivity-based selection of parameters is a key innovation, enabling the model to prioritize crucial knowledge for transfer. This intelligent initialization, combined with orthogonal gradient projection to maintain task-specific subspace independence, is what distinguishes their approach and enhances generalization. Essentially, the paper proposes a method of learning more efficiently by strategically utilizing past learning, rather than retraining from scratch. This targeted knowledge transfer is demonstrated to significantly boost performance and mitigate forgetting effects.

Orthogonal Subspaces#

The concept of orthogonal subspaces is crucial for continual learning, particularly within the context of large language models (LLMs). Orthogonality ensures that the knowledge acquired during the learning of one task does not interfere with the learning of subsequent tasks, thus mitigating the catastrophic forgetting problem. By projecting gradients onto orthogonal subspaces, new task-specific information is incorporated without overwriting previously established knowledge. This method preserves the model’s ability to perform well on all encountered tasks, enhancing both generalization and performance. The use of low-rank parameter updates within these orthogonal subspaces further contributes to parameter efficiency, making continual learning feasible for resource-intensive LLMs. Careful construction of these orthogonal subspaces is key to the success of this approach, requiring strategies that balance the independence of the subspaces (to minimize interference) with the need to leverage prior knowledge effectively (to promote generalization).

Initialization Strategies#

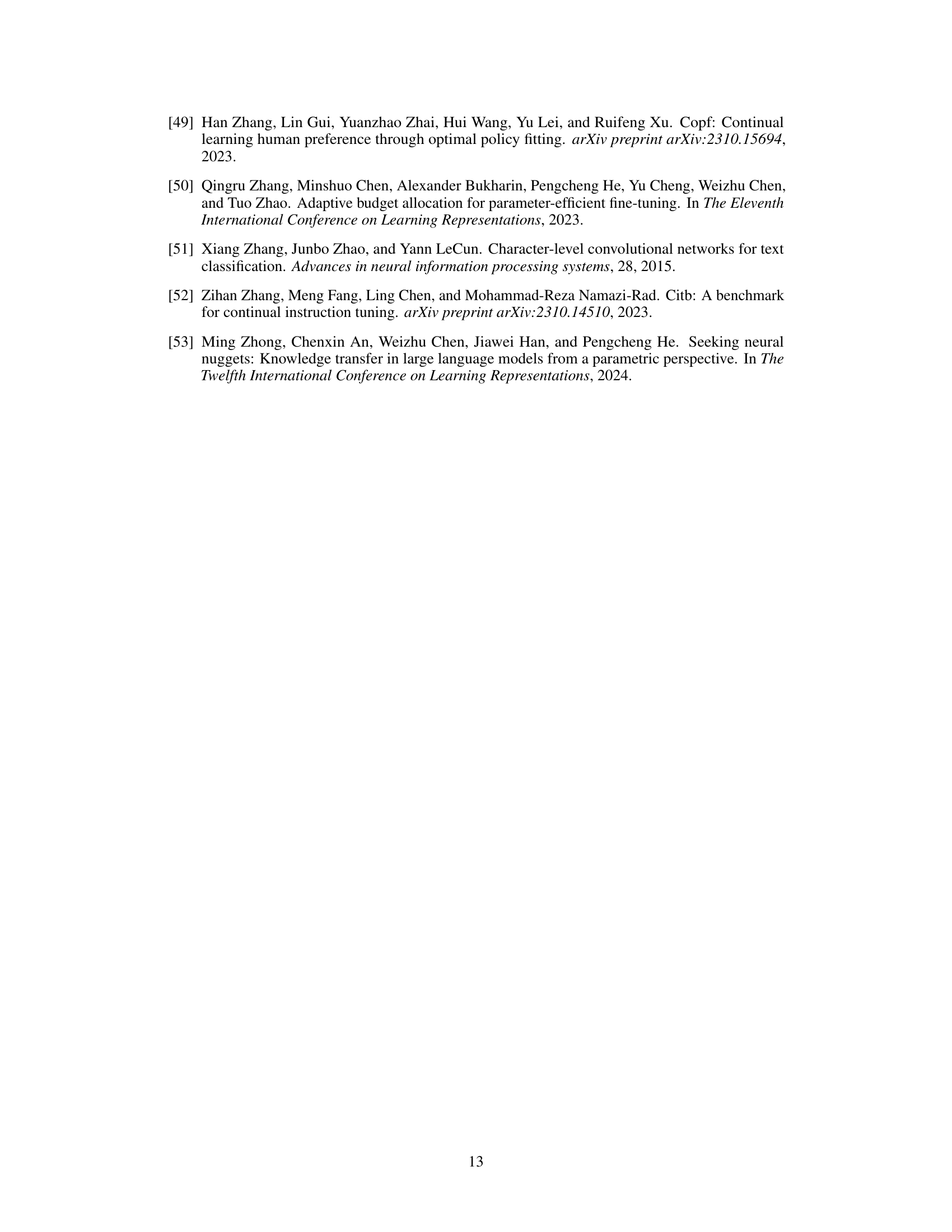

Effective initialization strategies are crucial for successful continual learning, particularly in parameter-efficient approaches for LLMs. Careful selection of initial parameters for new tasks can significantly impact performance by leveraging knowledge from previously learned tasks while minimizing catastrophic forgetting. The paper explores different initialization methods, including transferring knowledge from previous tasks via sensitivity-based analysis and SVD-based low-rank parameter injection. The choice of initializing with only the singular vectors (U, V) instead of the full triplets (U, Σ, V) proves more robust across different tasks, suggesting a trade-off between utilizing complete previous knowledge and improving generalization. The number of seed samples also affects performance, suggesting that a balanced number is needed to optimize efficiency and reliability. The study highlights the importance of initialization strategies in reducing forgetting and improving generalization by carefully injecting relevant knowledge from past tasks, demonstrating that even parameter-efficient methods require meticulous attention to initialization to achieve high performance in continual learning.

Future of LB-CL#

The future of LB-CL (Learn More but Bother Less Continual Learning) looks promising, particularly in addressing the limitations of current continual learning methods for LLMs. Improving generalization across diverse tasks remains a key focus; exploring advanced knowledge transfer techniques beyond sensitivity-based analysis could unlock enhanced performance. Investigating alternative initialization strategies that go beyond SVD-based low-rank parameters may be crucial. For example, incorporating techniques from meta-learning or self-supervised learning could lead to more robust and efficient knowledge injection. Scalability remains a challenge, especially for handling an increasingly large number of tasks and increasingly larger LLMs. Exploring techniques like model compression or efficient memory management will be vital for practical applications. Furthermore, thorough analysis of the sensitivity metric’s impact on different tasks and model architectures should improve performance. Finally, assessing the robustness of LB-CL under various conditions like noise in data and distribution shifts is crucial. Addressing these aspects will strengthen LB-CL’s applicability and utility within the field of continual learning.

More visual insights#

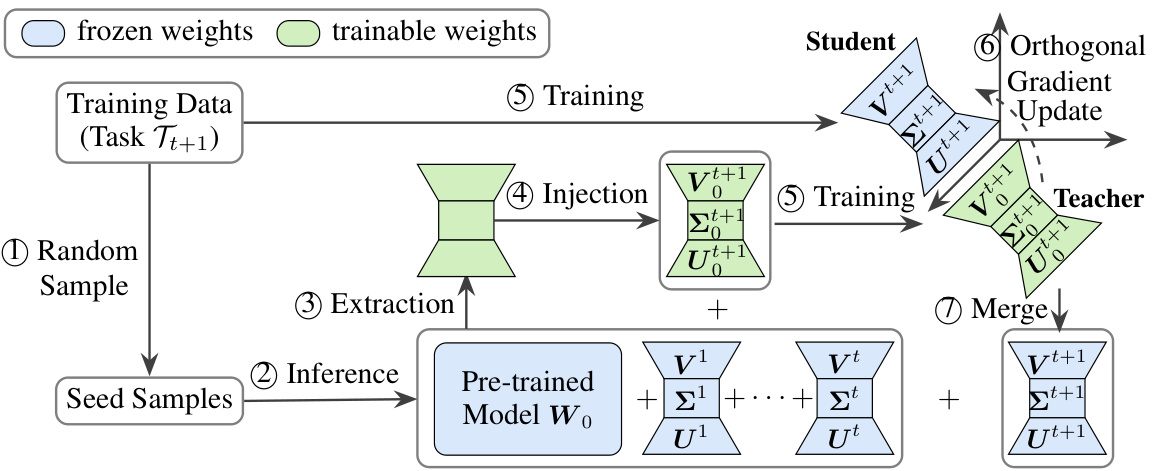

More on figures

This figure illustrates the LB-CL (Learn more but bother less Continual Learning) framework for continual learning in LLMs. It starts with a pre-trained model. Seed samples from the new task are used to calculate sensitivity metrics for SVD weights from previous tasks, extracting task-specific knowledge. This knowledge initializes the new task’s SVD weights. The new task is then trained in an orthogonal subspace to the previous tasks, using orthogonal gradient projection to minimize forgetting.

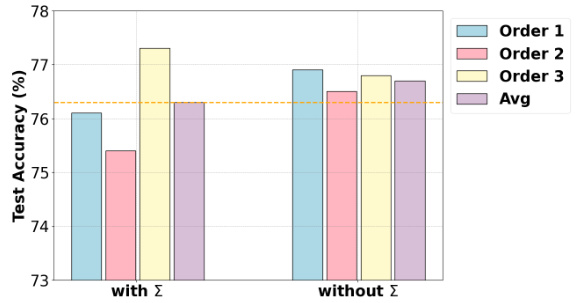

This figure compares two different initialization strategies for the LB-CL model in a continual learning setting. The strategies are: (i) using the full low-rank matrix triplets (with Σ) from previous tasks, and (ii) using only the left and right singular vectors (without Σ) from the previous tasks’ triplets. The comparison is made across three different task orders in a standard continual learning benchmark, and the average accuracy is presented. The figure shows that the initialization strategy without Σ outperforms the other in average accuracy. The results demonstrate the impact of initialization strategies on model performance and stability during continual learning.

This figure shows the impact of the number of seed samples used for sensitivity analysis on the performance of the LB-CL model. The x-axis represents different numbers of seed samples (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64), and the y-axis represents the average testing accuracy across three different task orders in the standard continual learning benchmark. Error bars represent the standard deviation. The results indicate that increasing the number of seed samples generally improves performance, but the gains diminish beyond a certain point, suggesting a diminishing return on increasing the number of samples. An optimal number of seed samples should be selected based on the balance between performance and computational cost.

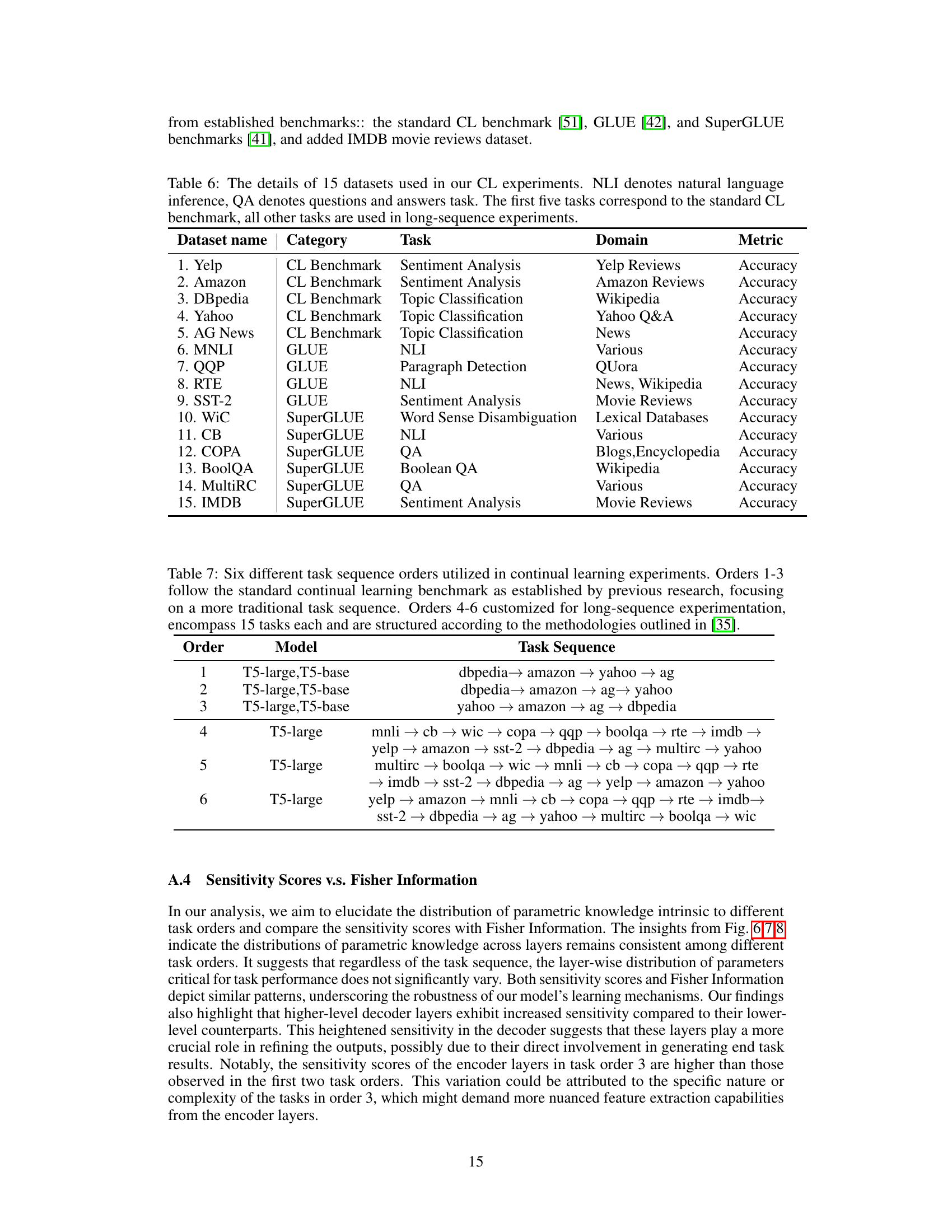

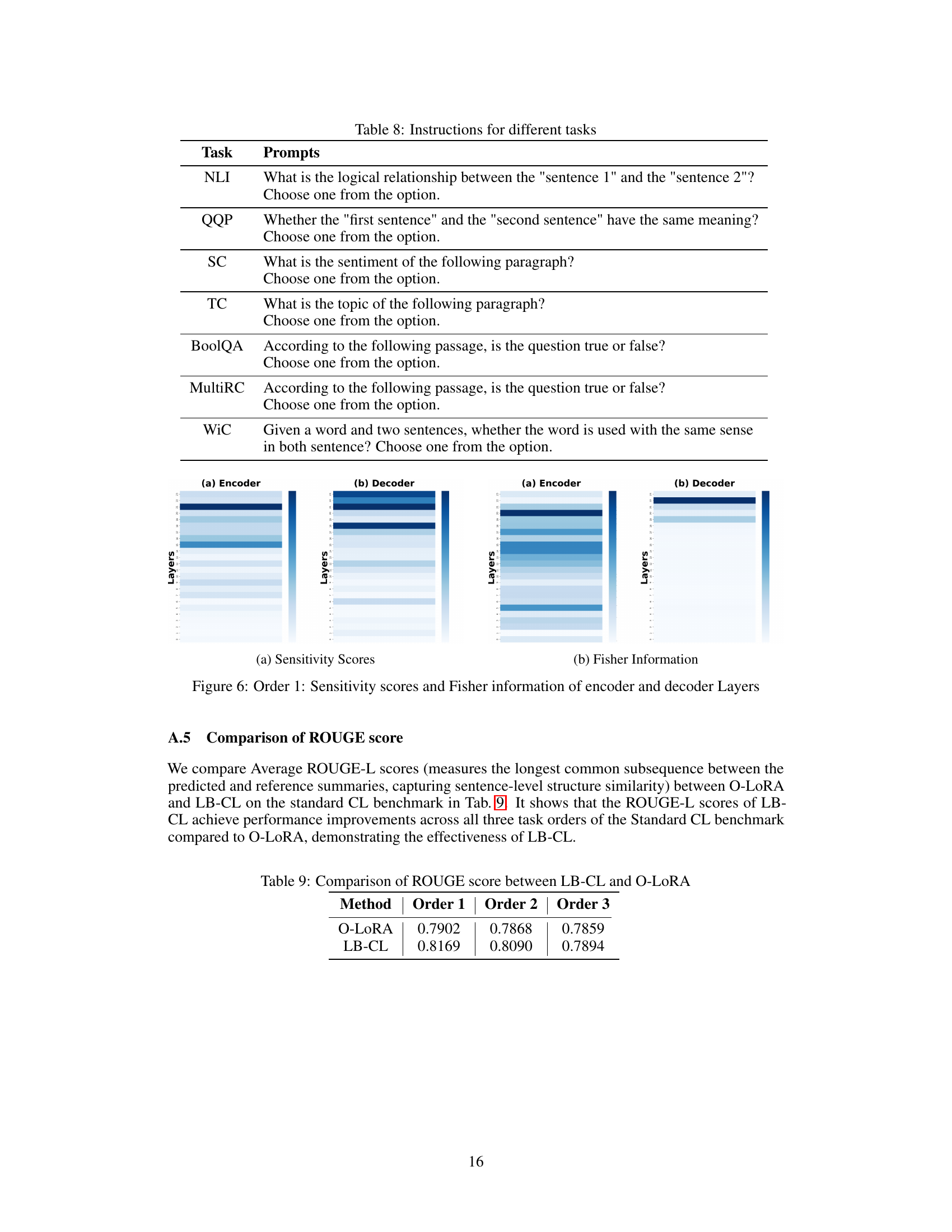

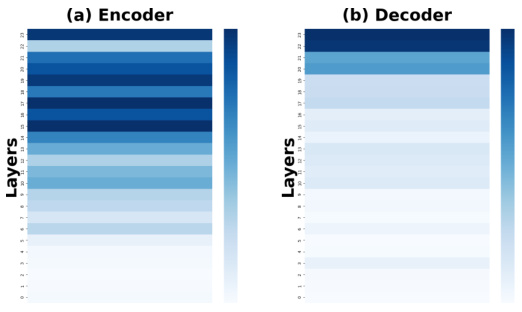

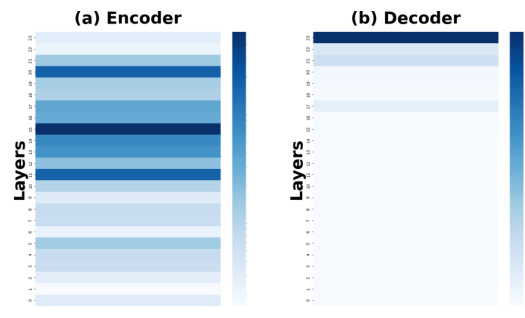

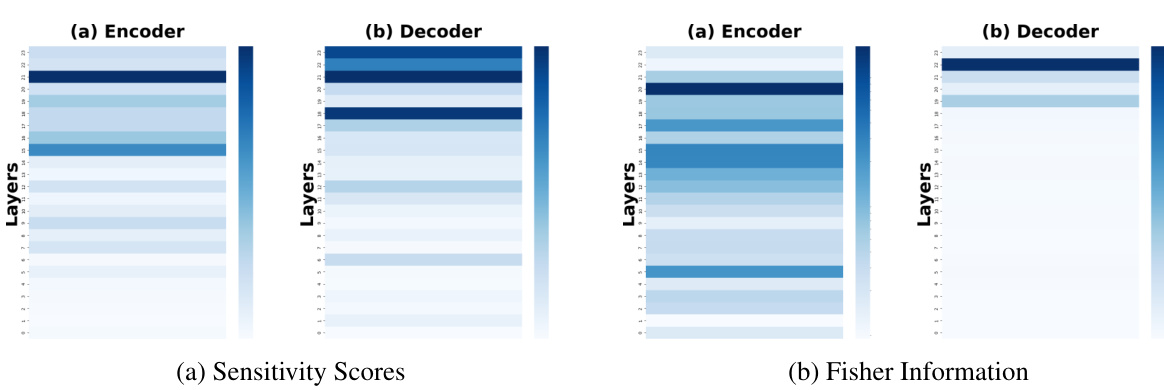

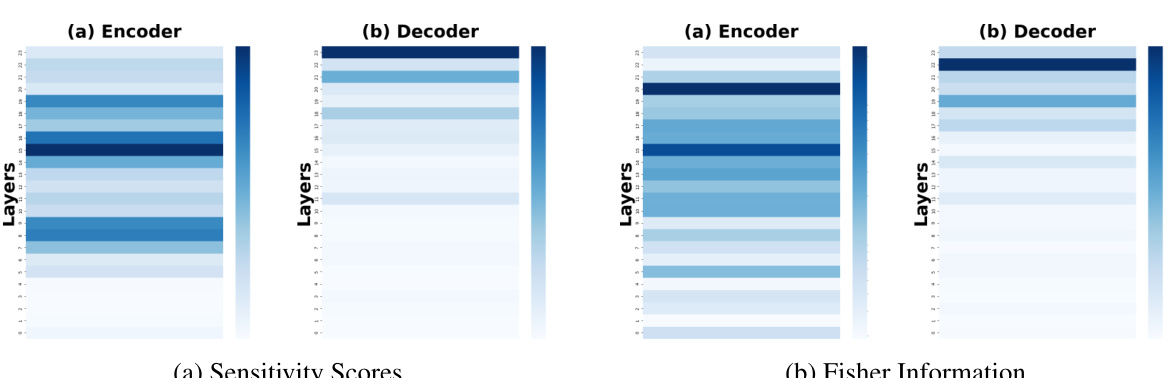

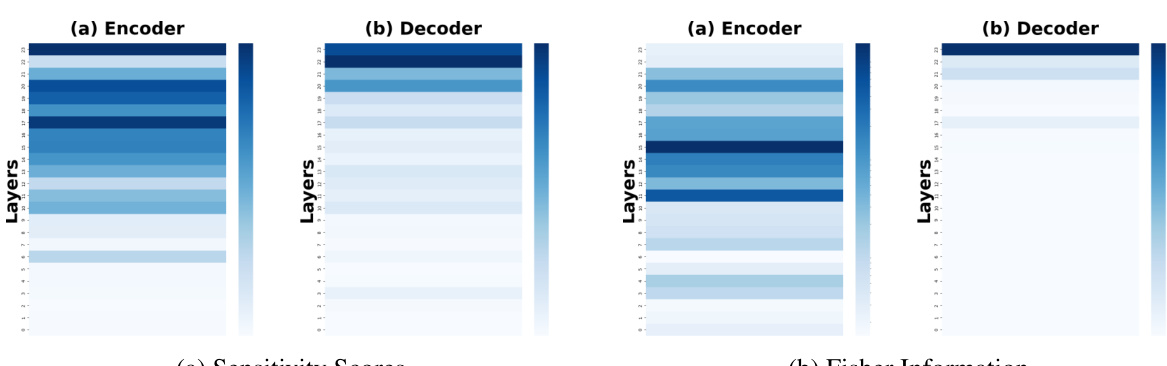

This figure compares the sensitivity scores and Fisher information across different layers (both encoder and decoder) of a model trained on a continual learning benchmark. The data shown is averaged across three different task orders to showcase the general trends. The color intensity represents the magnitude of sensitivity or Fisher information, with darker colors indicating higher values. This visualization helps to identify which layers are most crucial for retaining knowledge from previous tasks (higher sensitivity/Fisher information) during continual learning, which can inform model optimization strategies.

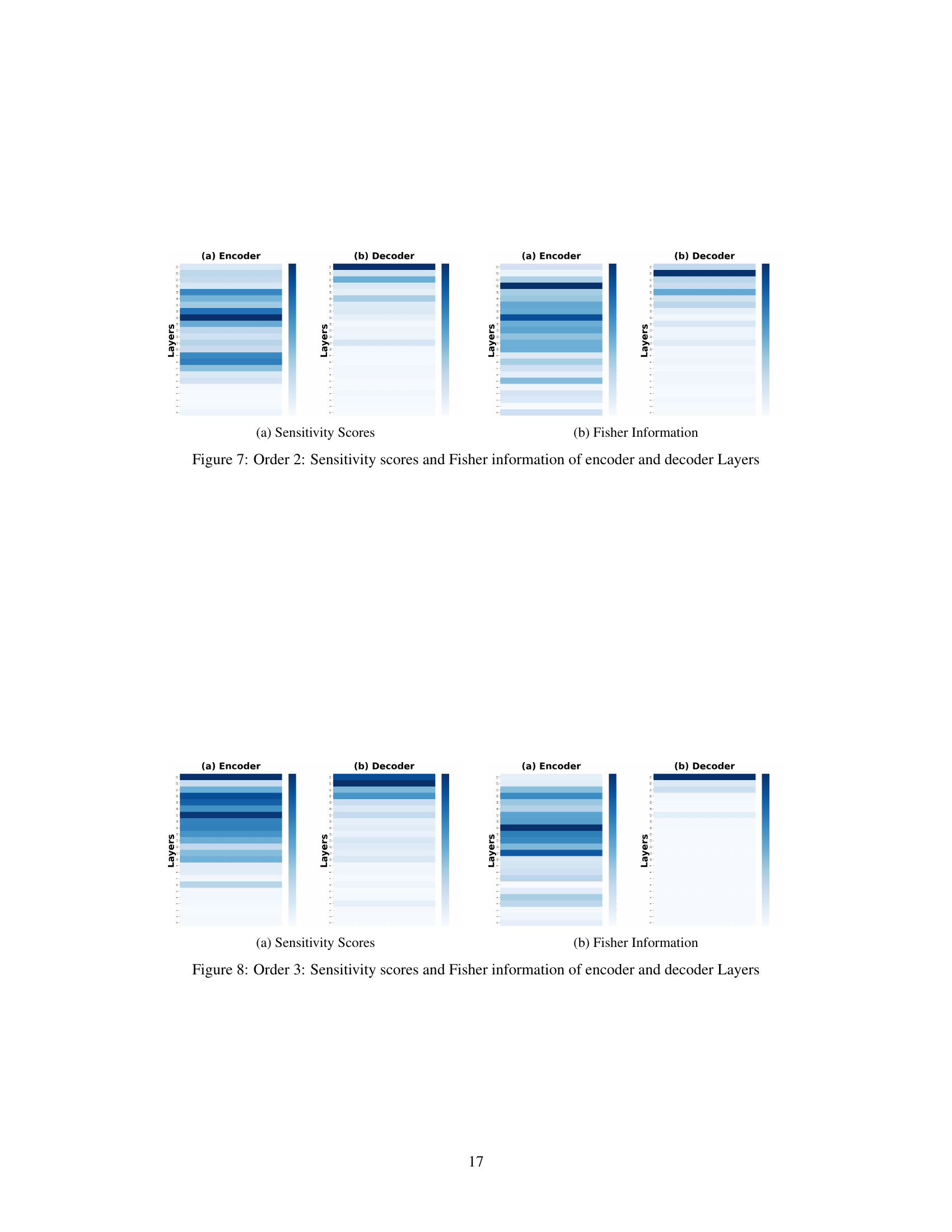

The figure shows a comparison of sensitivity scores and Fisher information for encoder and decoder layers across three different task orders in the standard continual learning benchmark. The heatmaps illustrate the distribution of sensitivity and Fisher information across layers, offering insight into which layers are most sensitive to changes in input data. This visualization aids in understanding which layers are most crucial for preserving previously learned knowledge during continual learning and effective knowledge transfer.

This figure shows the sensitivity scores and Fisher information for both encoder and decoder layers in the first task order. It visually represents how sensitive different layers of the model are to changes in the parameters, indicating which layers are most important for learning in the first task. Darker colors represent higher sensitivity or Fisher information, indicating more importance. The visualization helps in understanding the distribution of knowledge across different layers and informs strategies for parameter-efficient continual learning.

This figure shows the sensitivity scores and Fisher information for each layer (both encoder and decoder) of the model for task order 1. The color intensity represents the magnitude of the sensitivity or Fisher information, with darker colors indicating higher values. This visualization helps to understand which layers are most important for learning in the continual learning setting, as indicated by their higher sensitivity scores.

This figure shows the sensitivity scores and Fisher information for each layer of both encoder and decoder in task order 1. It visually represents the importance of different layers in the model for the first task in the continual learning sequence. Darker colors indicate higher sensitivity or Fisher information, suggesting that these layers are more important for learning and retaining knowledge from that task.

More on tables

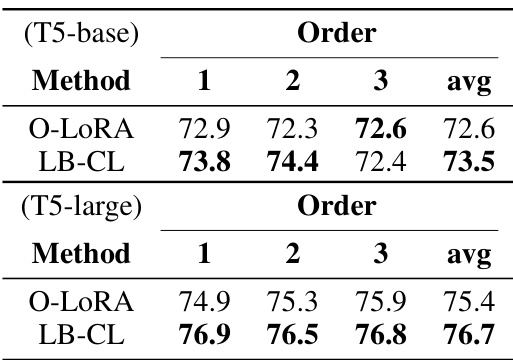

This table presents the results of continual learning experiments using the T5-large model on two benchmarks: a standard benchmark with three task orders and a large-number-of-tasks benchmark with three task orders. The table compares the performance of LB-CL against several baseline methods (SeqFT, SeqLoRA, IncLoRA, SeqSVD, Replay, EWC, LwF, L2P, LFPT5, L-CL, B-CL, NLNB-CL, O-LORA, ProgPrompt, PerTaskFT, and MTL). Average Accuracy (AA) is reported, which is the mean accuracy across all tasks after training on the last task.

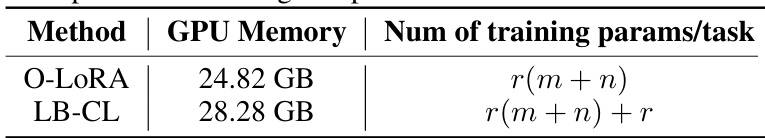

This table compares the GPU memory usage and the number of training parameters per task for both the O-LORA and LB-CL methods. It shows that LB-CL uses slightly more GPU memory but has a comparable number of training parameters compared to O-LORA, suggesting similar computational efficiency.

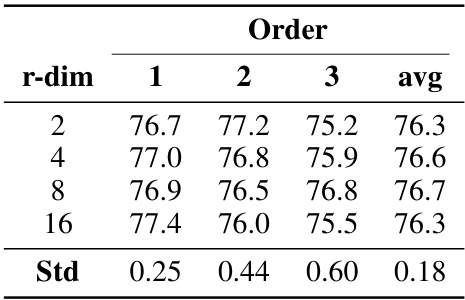

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing different ranks (r) of low-rank matrices in a continual learning setting using the T5-large model. The experiment is performed on a standard continual learning benchmark. The table shows the average accuracy across three different task orders (Order 1, Order 2, Order 3) for each rank (r=2,4,8,16). The ‘Std’ row shows the standard deviation across the three orders for each rank, providing a measure of the consistency of the performance.

This table presents the results of the continual learning experiments using the T5-large model on two benchmarks. The table compares the average accuracy across three different task orders for the LB-CL method against several baseline methods, including SeqFT, SeqLoRA, IncLoRA, SeqSVD, Replay, EWC, LwF, L2P, LFPT5, L-CL, B-CL, NLNB-CL, O-LORA, and ProgPrompt. PerTaskFT and MTL are also included as upper and lower performance bounds, respectively. The results show the performance of LB-CL compared to the baselines across different task sequences.

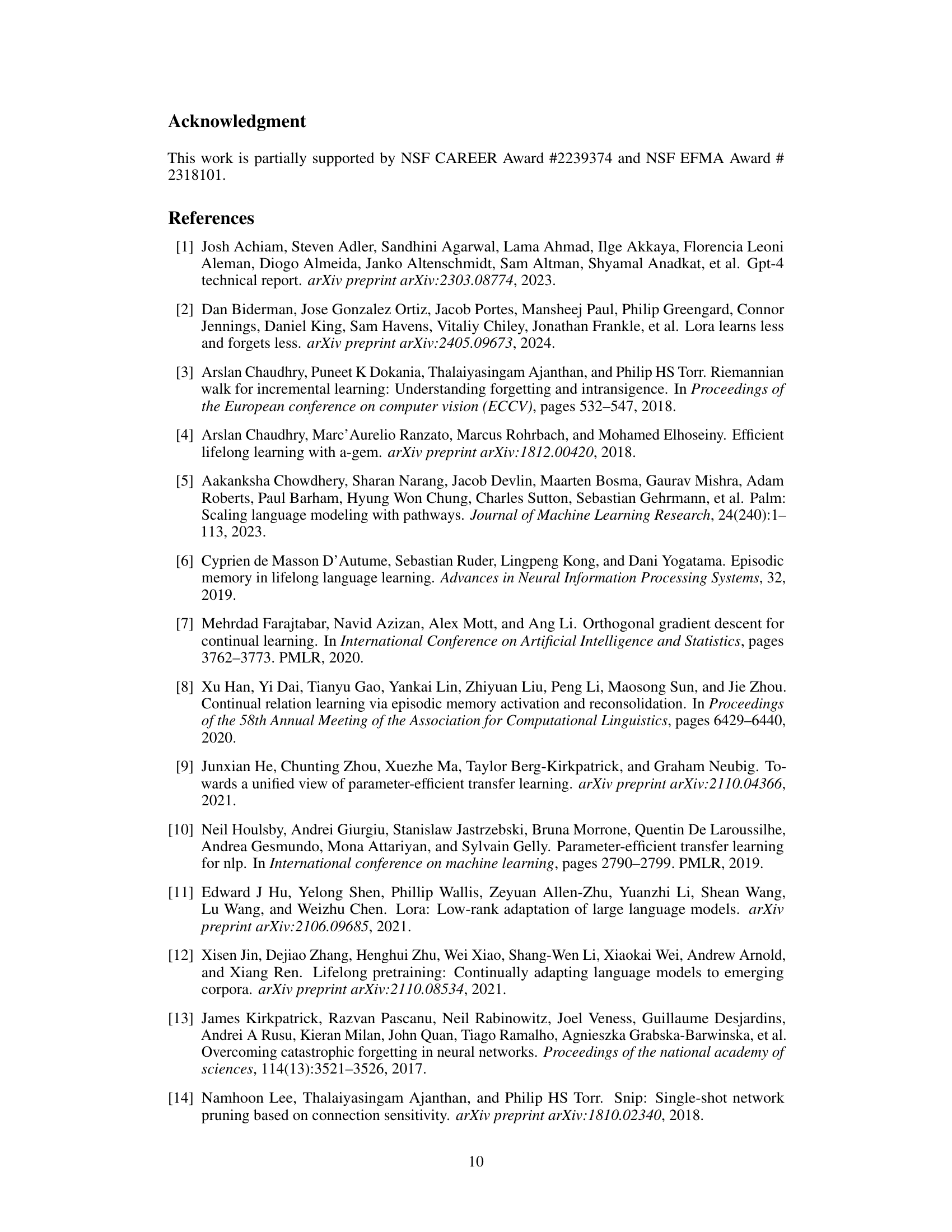

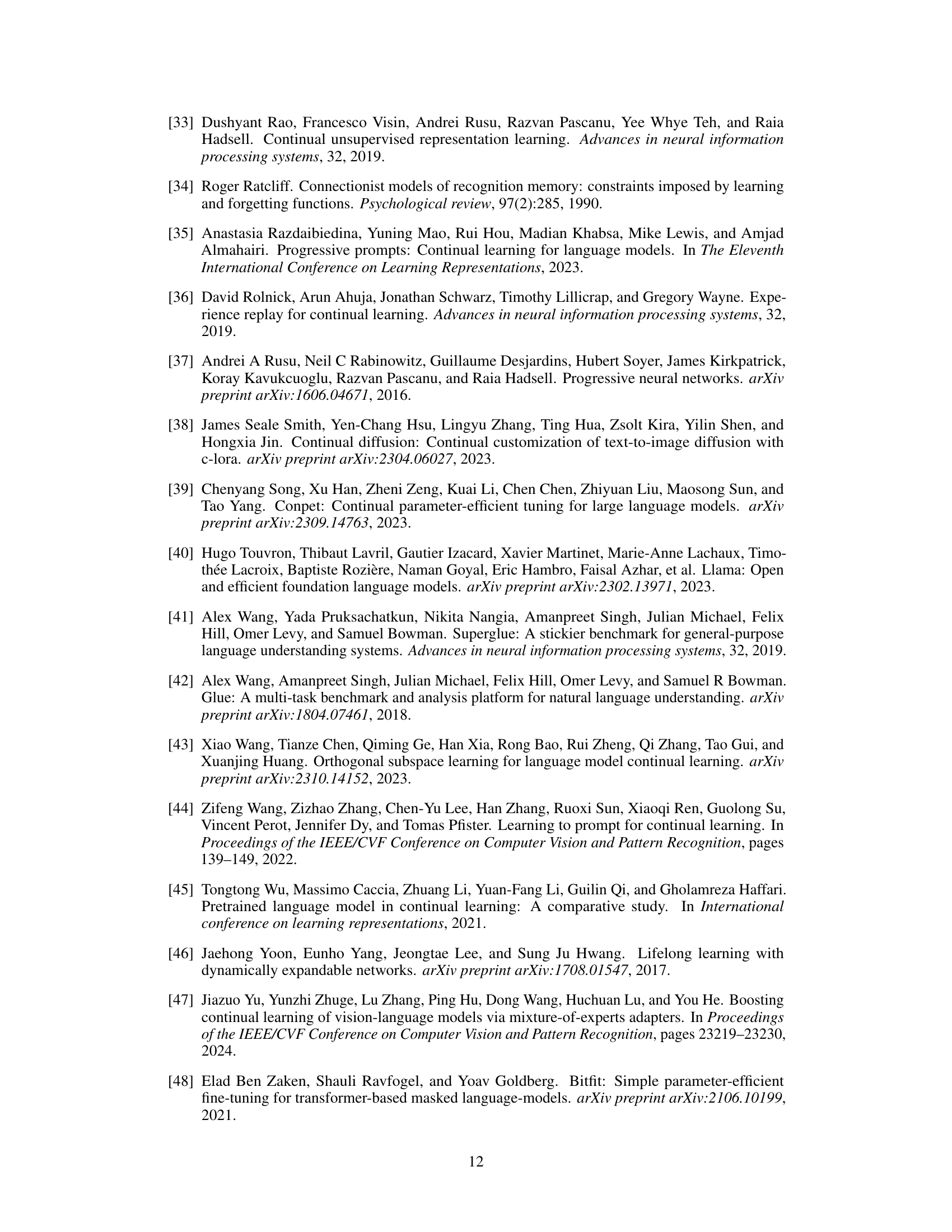

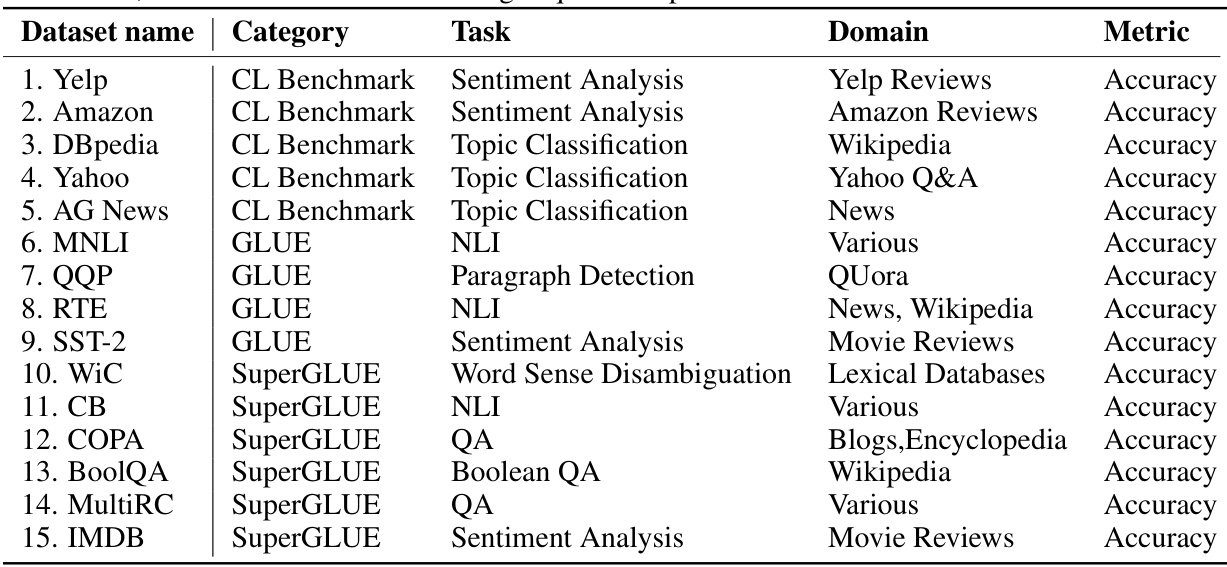

This table lists the 15 datasets used in the continual learning experiments of the paper. The first five datasets are from the standard continual learning benchmark, while the remaining 10 are from GLUE, SuperGLUE, and IMDB. Each dataset’s category, task type, domain, and evaluation metric (Accuracy) are specified.

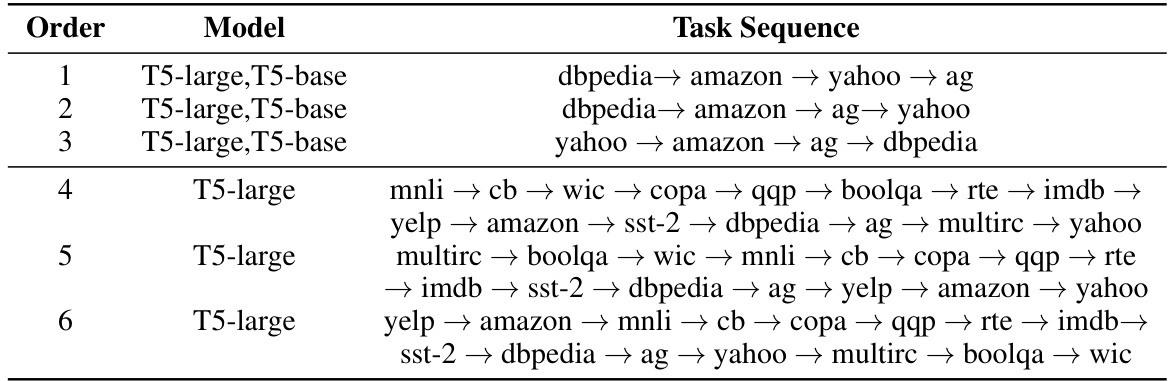

This table presents six different task sequences used in the continual learning experiments. The first three sequences are based on the standard continual learning benchmark, while the last three are designed for evaluating performance on a larger number of tasks. Each sequence specifies the order in which the 15 datasets (or a subset for the first three) are presented to the model during training.

This table presents the results of the proposed LB-CL method and several baseline methods on two continual learning benchmarks using the T5-large model. The first benchmark is a standard continual learning benchmark with five text classification tasks, evaluated across three different task orders. The second benchmark features fifteen datasets from three different sources and is evaluated with three different orders. The results show the average accuracy across all tasks after training on the final task for each method and task order. The table demonstrates the superior performance of LB-CL compared to existing state-of-the-art methods in continual learning for LLMs.

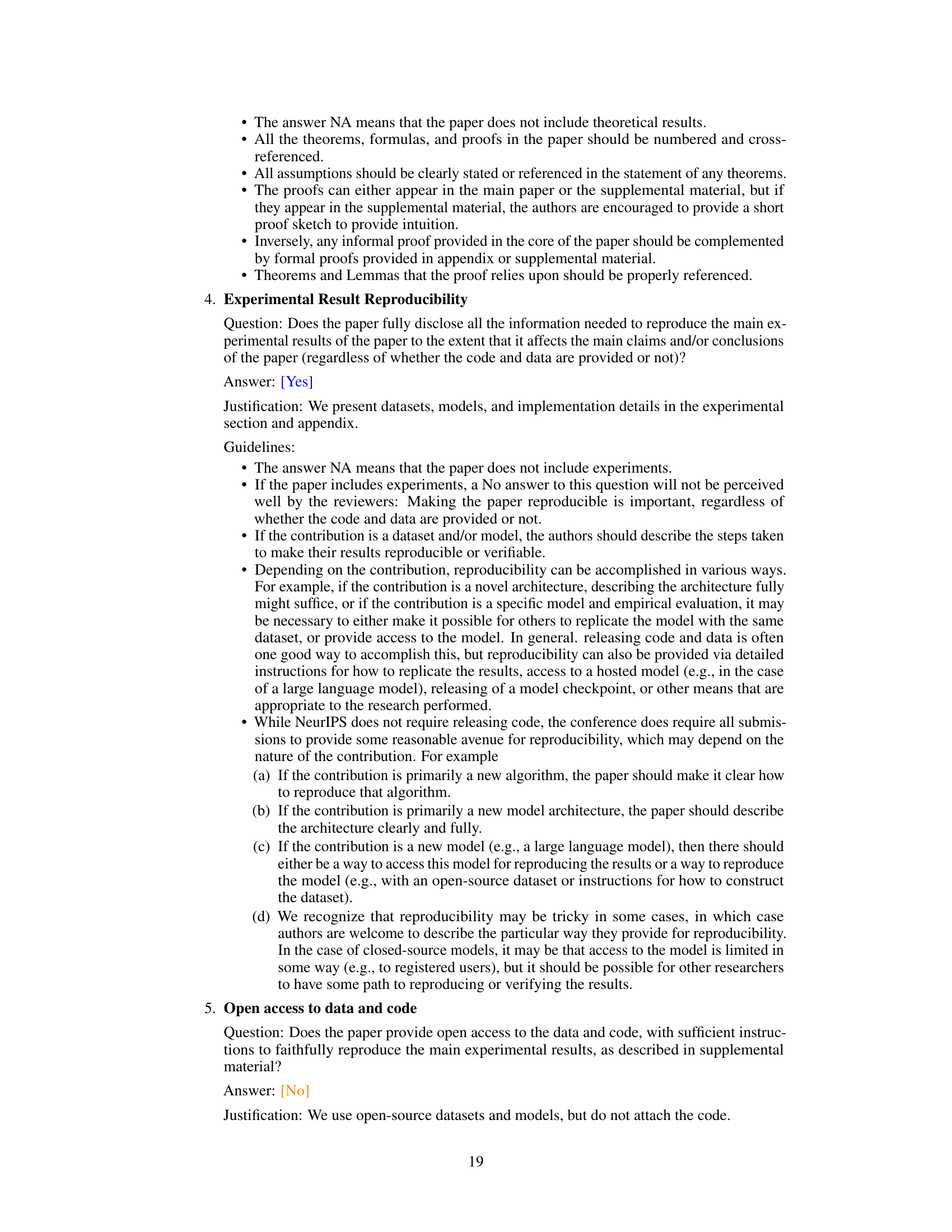

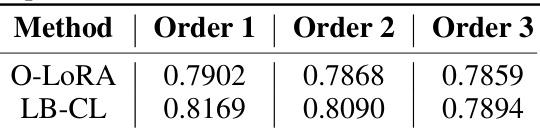

This table compares the average ROUGE-L scores (measuring the longest common subsequence between predicted and reference summaries) achieved by LB-CL and O-LORA across three different task orders in the standard Continual Learning benchmark. ROUGE-L is used to assess the quality of summaries generated by each method. The table demonstrates the improved performance of LB-CL compared to O-LORA across various ordering of tasks.

Full paper#