↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Universal Transformers (UTs) offer advantages in compositional generalization but suffer from a high parameter-compute ratio, hindering their use in large-scale tasks like language modeling. Existing methods to improve the parameter count either make the models computationally expensive or fail to achieve competitive performance.

This paper introduces MoEUT, a novel architecture that integrates mixture-of-experts (MoE) into UTs. MoEUT employs MoEs for both feedforward and attention layers, combined with layer grouping and a peri-layernorm scheme. This design dramatically improves UTs’ compute efficiency, enabling them to outperform standard Transformers in language modeling while using significantly fewer parameters and computational resources. The results demonstrate the efficacy of MoEUT across various datasets and tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical limitation of Universal Transformers (UTs) – their poor parameter-compute ratio – by using a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) approach. This makes UTs, known for superior compositional generalization, practical for large-scale language modeling. The research opens avenues for more efficient and powerful language models and advances MoE techniques in Transformer architectures. It also provides valuable insights into the design of shared-layer models, contributing to our understanding of the interplay between efficiency and performance.

Visual Insights#

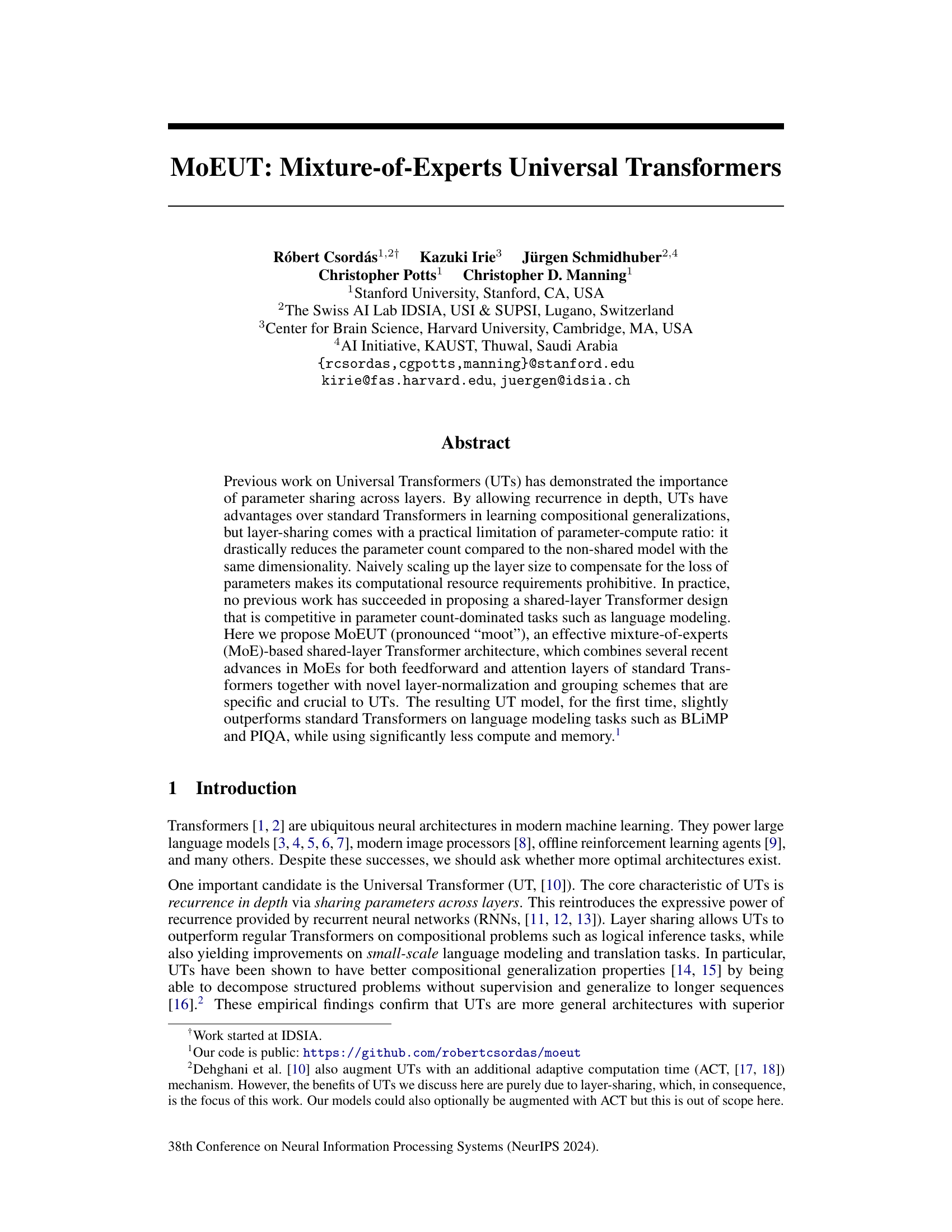

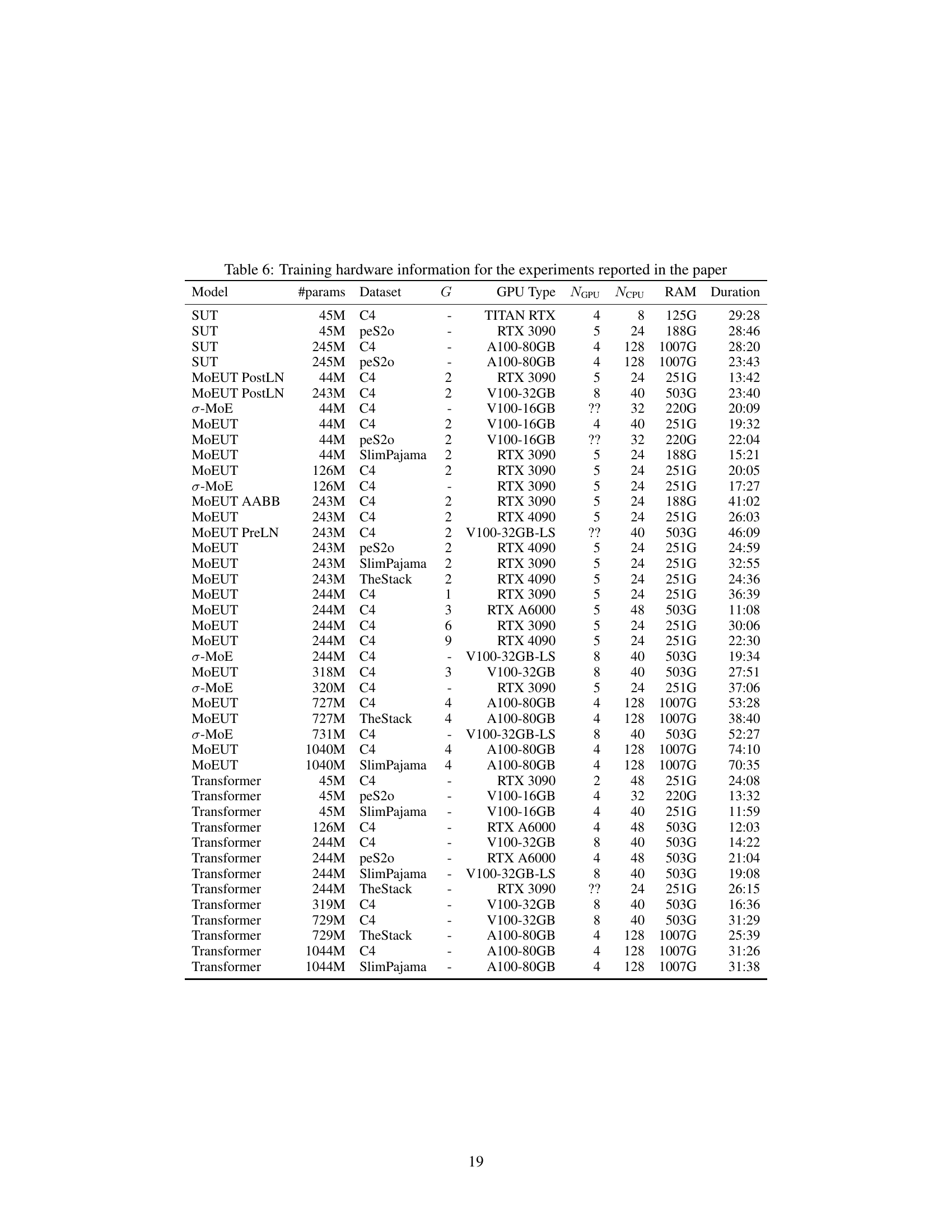

This figure illustrates the layer grouping concept used in the MoEUT architecture. It shows 8 layers stacked recurrently. The layers are grouped into pairs (G=2), where the layers within each group have different weights, but the groups themselves share parameters. This strategy balances the benefits of parameter sharing across layers for efficient computation, with the expressiveness gained from having multiple non-shared layers within a group, to mitigate limitations of shared-layer Transformer architecture. The diagram visually separates layers A and B within the groups to emphasize the weight sharing.

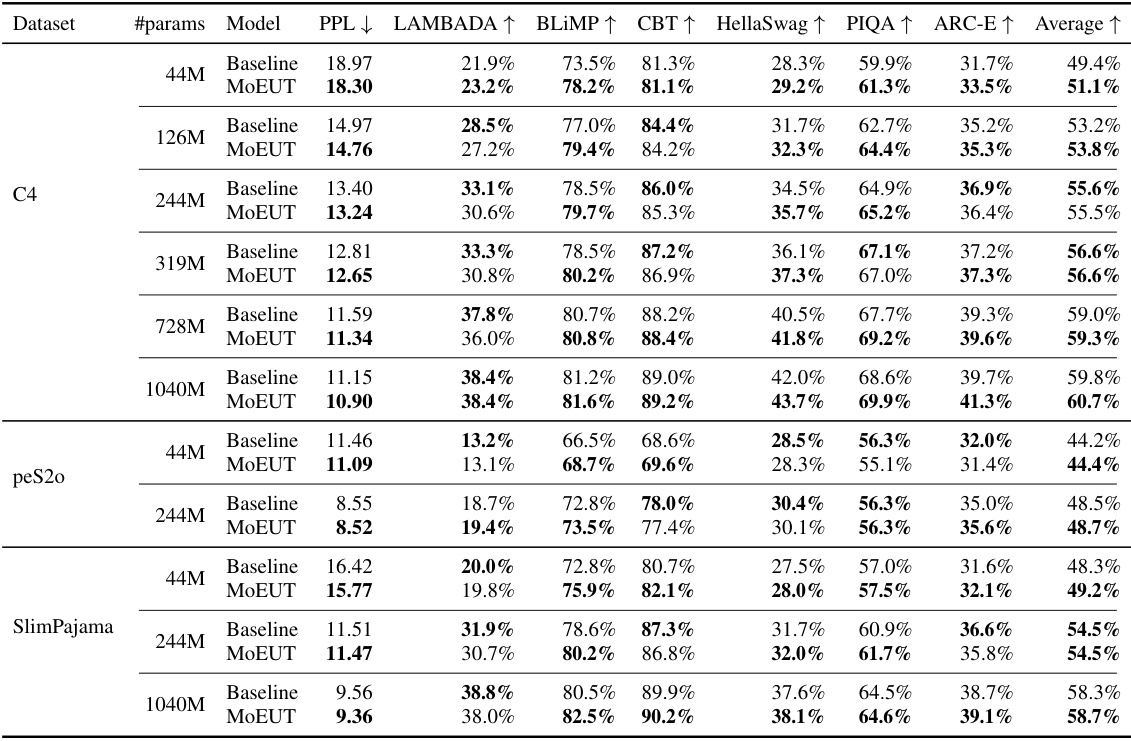

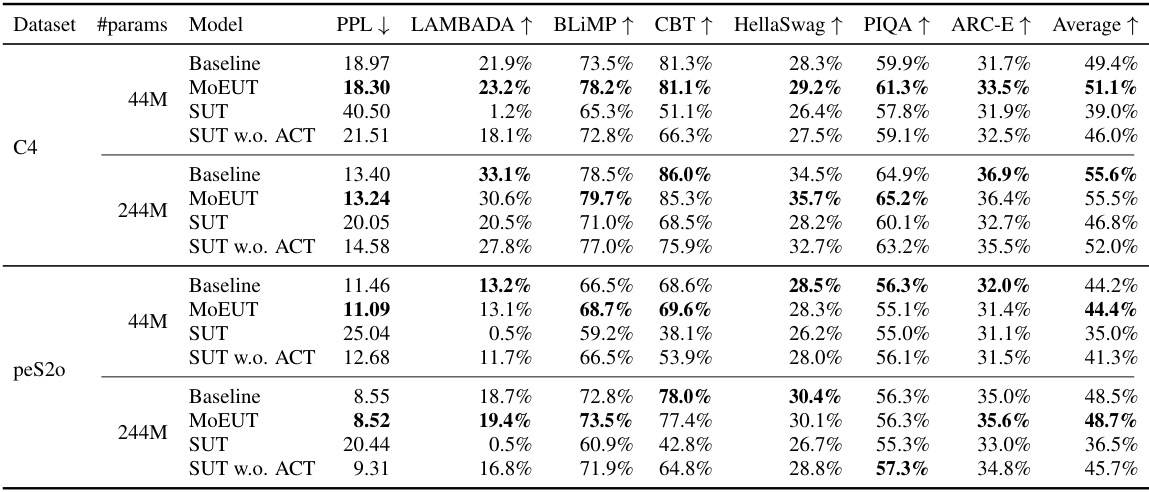

This table presents the zero-shot performance of MoEUT and baseline Transformer models on six downstream tasks (LAMBADA, BLIMP, Children’s Book Test, HellaSwag, PIQA, and ARC-E) across different datasets (C4, peS2o, SlimPajama) and model sizes. The results show that MoEUT achieves comparable or slightly better performance than the baseline Transformers on these tasks, highlighting its effectiveness even without specific training for the downstream tasks.

In-depth insights#

MoEUT Architecture#

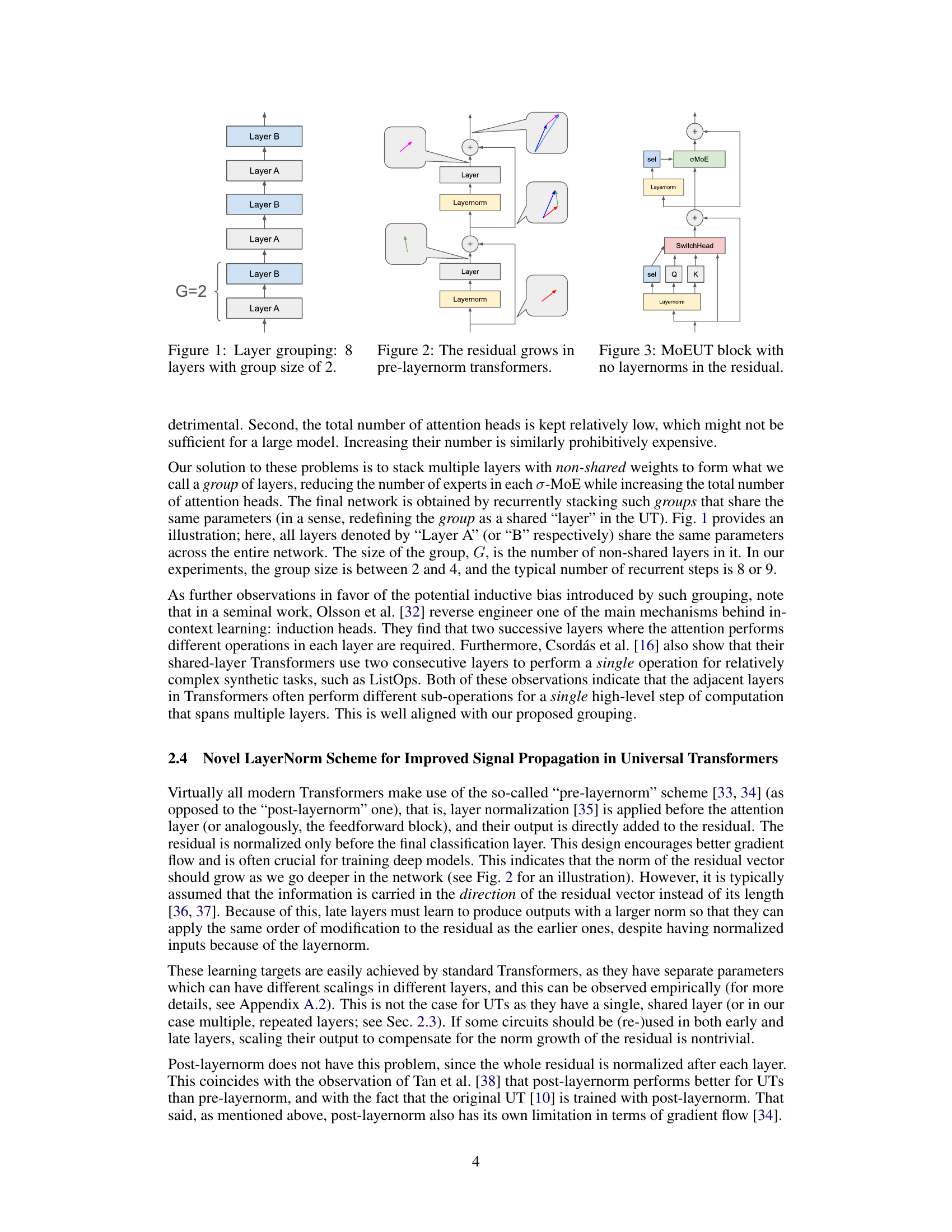

The MoEUT architecture cleverly tackles the parameter-compute ratio problem inherent in Universal Transformers (UTs) by integrating a mixture-of-experts (MoE) approach. This innovative design allows MoEUT to leverage the benefits of parameter sharing across layers, a key strength of UTs for compositional generalization, while simultaneously addressing the computational burden associated with scaling up shared-layer models. Key innovations within MoEUT include the use of MoEs in both feedforward and self-attention layers, layer normalization strategically placed before activation functions, and a novel layer grouping scheme. This grouping method facilitates efficient scaling by stacking groups of MoE-based layers, managing expert selection and resource allocation more effectively. The combination of these techniques results in a UT model that not only achieves competitive performance on various language modeling tasks but also significantly improves parameter and compute efficiency.

Parameter Efficiency#

The core of the paper revolves around enhancing parameter efficiency in Universal Transformers (UTs). Standard UTs, while boasting strong compositional generalization capabilities, suffer from a parameter-compute ratio problem: parameter sharing across layers, although beneficial for generalization, drastically reduces the overall parameter count compared to non-shared models. This limitation hinders UTs’ competitiveness, especially in parameter-intensive tasks like language modeling. The authors introduce Mixture-of-Experts Universal Transformers (MoEUTs) as a solution. MoEUTs cleverly utilize mixture-of-experts (MoE) techniques for both feedforward and attention layers, allowing for greater expressiveness while maintaining parameter efficiency. The design further incorporates novel layer normalization and grouping schemes, crucial for mitigating the performance trade-offs associated with shared-layer MoEs. This approach is shown to yield UT models that outperform standard Transformers, particularly at larger scales, while demanding significantly less compute and memory. The parameter efficiency gains are particularly significant considering the inherent challenges of scaling up shared-parameter models.

Layer Grouping#

The concept of ‘Layer Grouping’ in the context of Mixture-of-Experts Universal Transformers (MoEUTs) addresses a critical limitation of traditional Universal Transformers (UTs): the parameter-compute ratio. By grouping multiple layers with non-shared weights, MoEUTs reduce the number of experts required in each MoE layer while increasing the overall number of attention heads. This approach is particularly beneficial for larger models, preventing issues related to diminishing returns from increasing the number of experts and enabling the model to scale more efficiently. The authors hypothesize that this grouping aligns with the inherent inductive bias of UTs, which suggests that adjacent layers often perform different sub-operations within a single high-level computation. Empirical evidence strongly supports this layer grouping strategy, demonstrating improved performance at larger scales. The grouping scheme, combined with a novel peri-layernorm approach, allows MoEUTs to achieve better signal propagation and gradient flow, enhancing the overall performance of shared-layer models.

Empirical Results#

An Empirical Results section in a research paper would typically present quantitative findings that support or refute the study’s hypotheses. A strong Empirical Results section would begin by clearly stating the metrics used to assess performance, for example, accuracy, precision, recall, or F1-score, depending on the nature of the task. The results would then be presented in a clear and concise manner, using tables, graphs, or figures to visualize the data. Statistical significance testing is crucial to determine if observed differences in performance are meaningful or due to chance. The discussion of the results should connect them back to the hypotheses, explaining why certain results were obtained and highlighting any unexpected or surprising findings. Comparisons to prior state-of-the-art techniques are also commonly included, demonstrating the advancements made by the research. Finally, any limitations or potential biases of the experimental setup should be openly acknowledged, promoting transparency and scientific rigor.

Future of UTs#

The future of Universal Transformers (UTs) hinges on addressing their current limitations. Computational efficiency remains a significant hurdle, as UTs’ parameter sharing, while beneficial for generalization, leads to a parameter-compute ratio disadvantage compared to standard Transformers. Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) approaches, as explored in MoEUT, offer a promising avenue for scaling UTs efficiently by distributing computation across specialized experts. Further research into optimized MoE implementations and novel architectures tailored for UTs is needed. Improving signal propagation in shared-layer models, such as through refined layer normalization schemes, is also critical. Additionally, further investigation into the inductive biases inherent in UTs, especially the potential for superior compositional generalization, is warranted. By addressing these challenges, UTs could surpass standard Transformers in performance on complex tasks while maintaining computational feasibility.

More visual insights#

More on figures

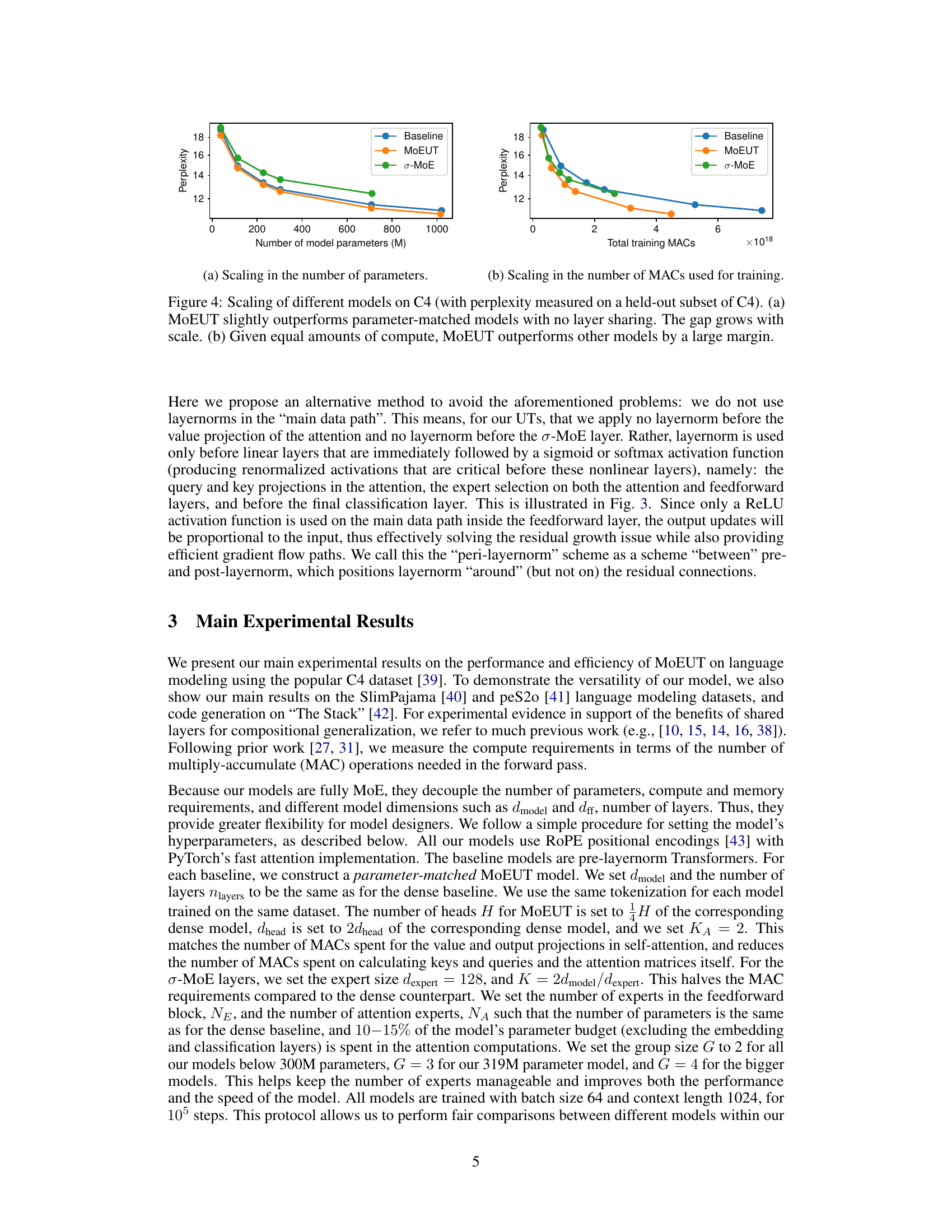

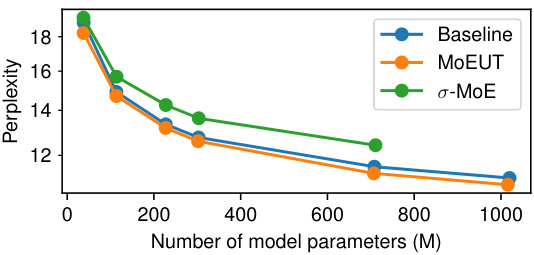

This figure compares the performance of MoEUT against standard Transformers and σ-MoE models on the C4 dataset. Two subfigures illustrate scaling performance: (a) shows that MoEUT slightly outperforms models with a similar number of parameters but without layer sharing, and this difference increases with model size. (b) demonstrates that for a given compute budget (measured in Multiply-Accumulate operations during training), MoEUT significantly surpasses other models in terms of perplexity.

This figure compares the performance of different Transformer models on the C4 dataset in terms of perplexity. Panel (a) shows that the MoEUT model slightly outperforms dense models with an equivalent number of parameters. The performance difference is larger with bigger models. Panel (b) demonstrates that given equal computational resources (measured in multiply-accumulate operations, or MACs), MoEUT significantly surpasses other models.

This figure demonstrates the scaling properties of different models on the C4 dataset. It shows perplexity on a held-out subset of C4, comparing MoEUT against standard Transformers and a σ-MoE model. Panel (a) compares the models with similar numbers of parameters, showing MoEUT performs slightly better, with the difference growing as the parameter count increases. Panel (b) compares models using equivalent compute resources (measured in Multiply-Accumulate operations), showing that MoEUT significantly outperforms the others.

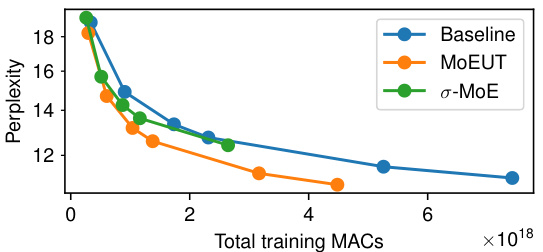

This figure shows the perplexity achieved by 244M parameter MoEUT models trained on the C4 dataset, with varying group sizes (G). The group size, G, represents the number of layers stacked together before parameter sharing is reintroduced. The results demonstrate that a small group size of G=2 yields the lowest perplexity, outperforming models with larger group sizes or no layer grouping. This finding highlights the benefit of carefully balancing the extent of parameter sharing in the MoEUT architecture to optimize performance.

This figure compares the performance of MoEUT against standard Transformers and σ-MoE models on the C4 dataset. Subfigure (a) shows that MOEUT performs slightly better than parameter-matched models without layer sharing, with the performance gap widening as model size increases. Subfigure (b) demonstrates MOEUT’s significant computational advantage, showcasing its superior performance when compared to other models given equivalent compute resources.

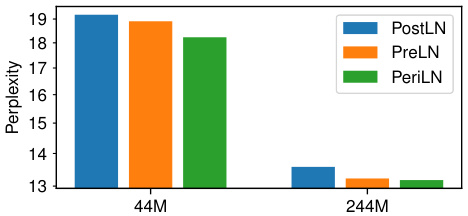

This figure compares the performance of three different layernorm schemes (pre-layernorm, post-layernorm, and peri-layernorm) on two different sized models (44M and 244M parameters). The y-axis represents perplexity, a measure of the model’s performance on a language modeling task. Peri-layernorm consistently achieves lower perplexity, indicating superior performance compared to the other methods. This suggests that the peri-layernorm scheme effectively balances gradient flow and residual signal propagation, leading to improved model training and generalization. The improvements are more significant for the smaller model (44M parameters), and the difference narrows as the model size grows.

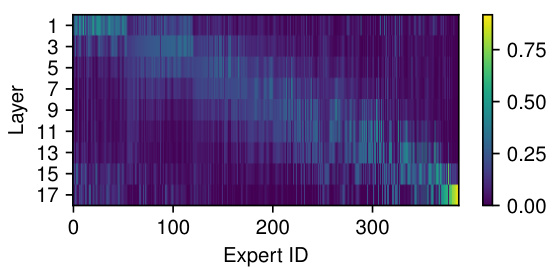

This figure visualizes the distribution of layers where each expert in the MLP layers is activated. The x-axis represents the expert ID, and the y-axis represents the layer number. The color intensity represents the frequency of expert activation in each layer. The figure demonstrates that while some experts are primarily activated in specific layers, most experts are used across multiple layers, highlighting the model’s flexibility in assigning experts to layers dynamically, based on the task’s needs.

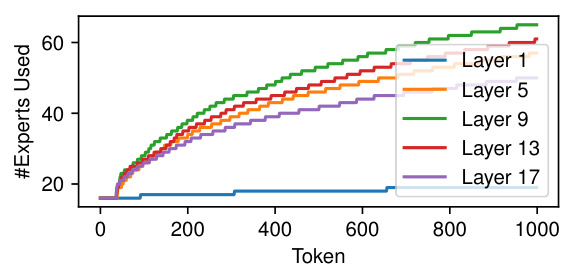

This figure shows the number of unique experts used for different tokens across various layers of the model. The x-axis represents tokens ordered by the number of experts used in layer 1. The y-axis shows the total number of unique experts used. The plot demonstrates that the number of unique experts used per token increases significantly in the middle layers (around layer 9), indicating that contextual information significantly influences expert selection. The diversity of experts used then decreases slightly towards the output layers.

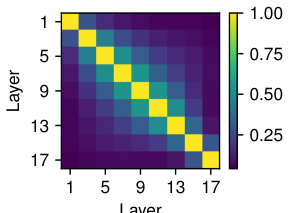

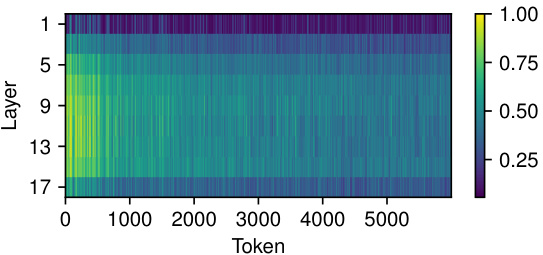

This figure visualizes the similarity of expert selection between different layers for individual input tokens. The heatmap shows the Jaccard similarity (intersection over union) of the sets of experts used for each token across various layers. High values (yellow) indicate high similarity, meaning that the same or very similar sets of experts are selected for that token across multiple layers. Lower values (darker colors) suggest more variation in expert selection across layers. The figure illustrates the dynamic nature of expert selection in MoEUT, where expert use varies depending on the context and layer.

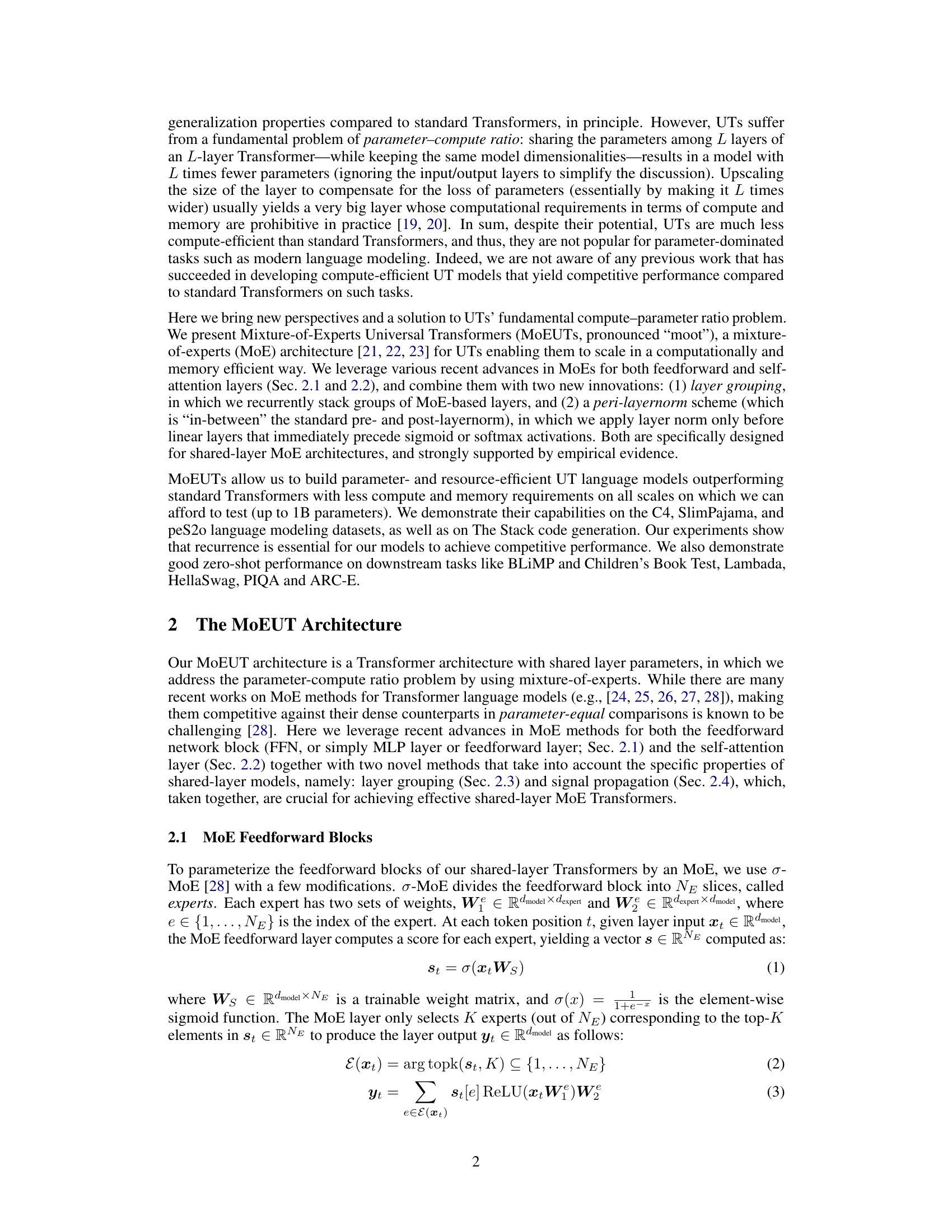

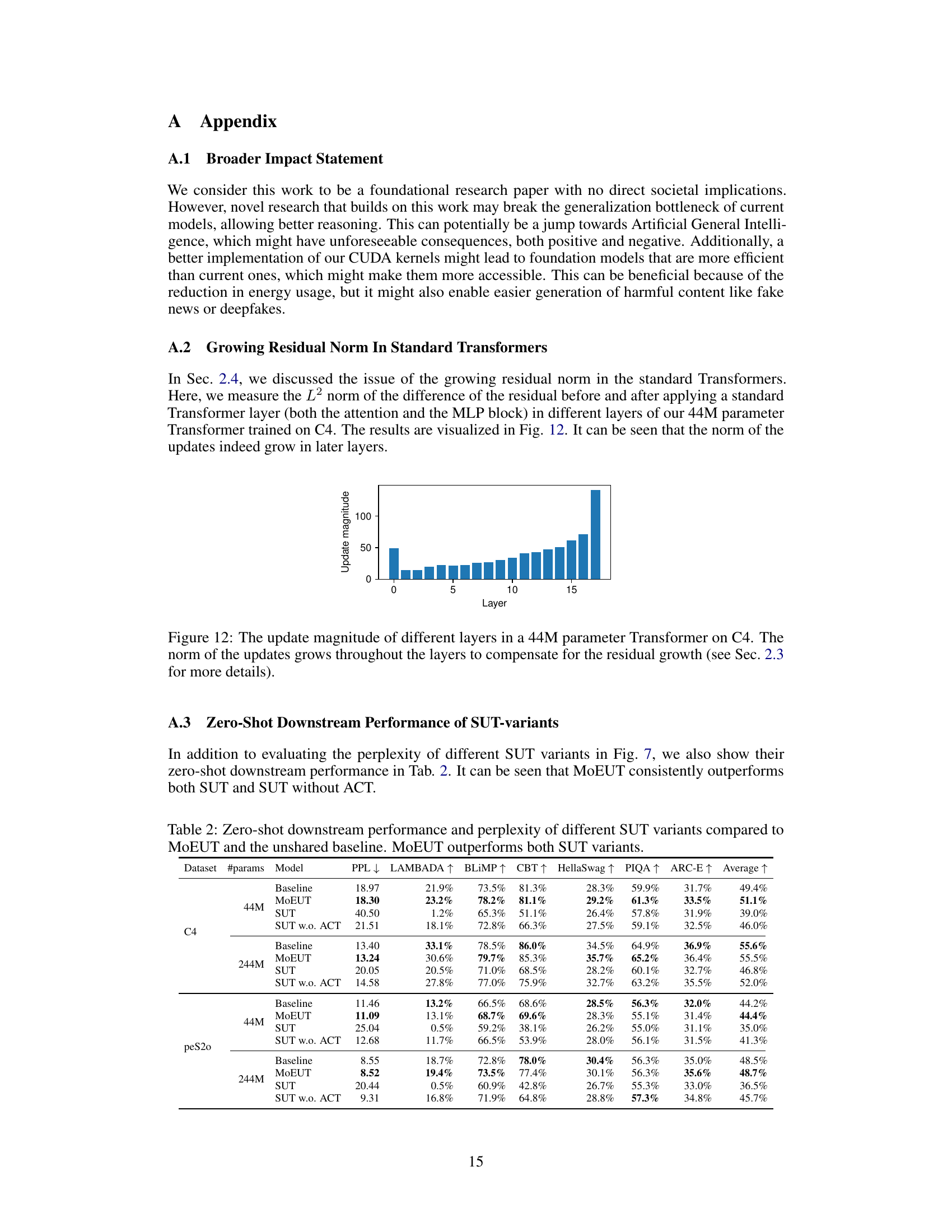

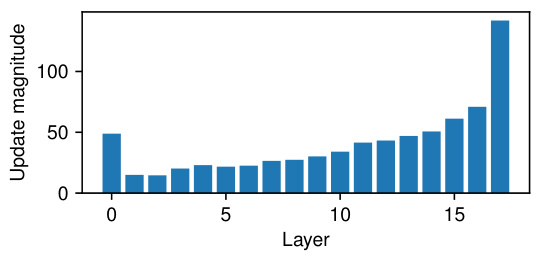

This figure shows the L2 norm of the difference between the residual before and after applying a standard Transformer layer (both attention and MLP block) in different layers of a 44M parameter Transformer trained on C4 dataset. The y-axis represents the update magnitude, and the x-axis represents the layer number. The figure demonstrates that the norm of these updates increases as the layer number increases, illustrating the phenomenon of growing residual norm in standard Transformers. This growth necessitates a compensatory mechanism, which is addressed in Section 2.3 of the paper.

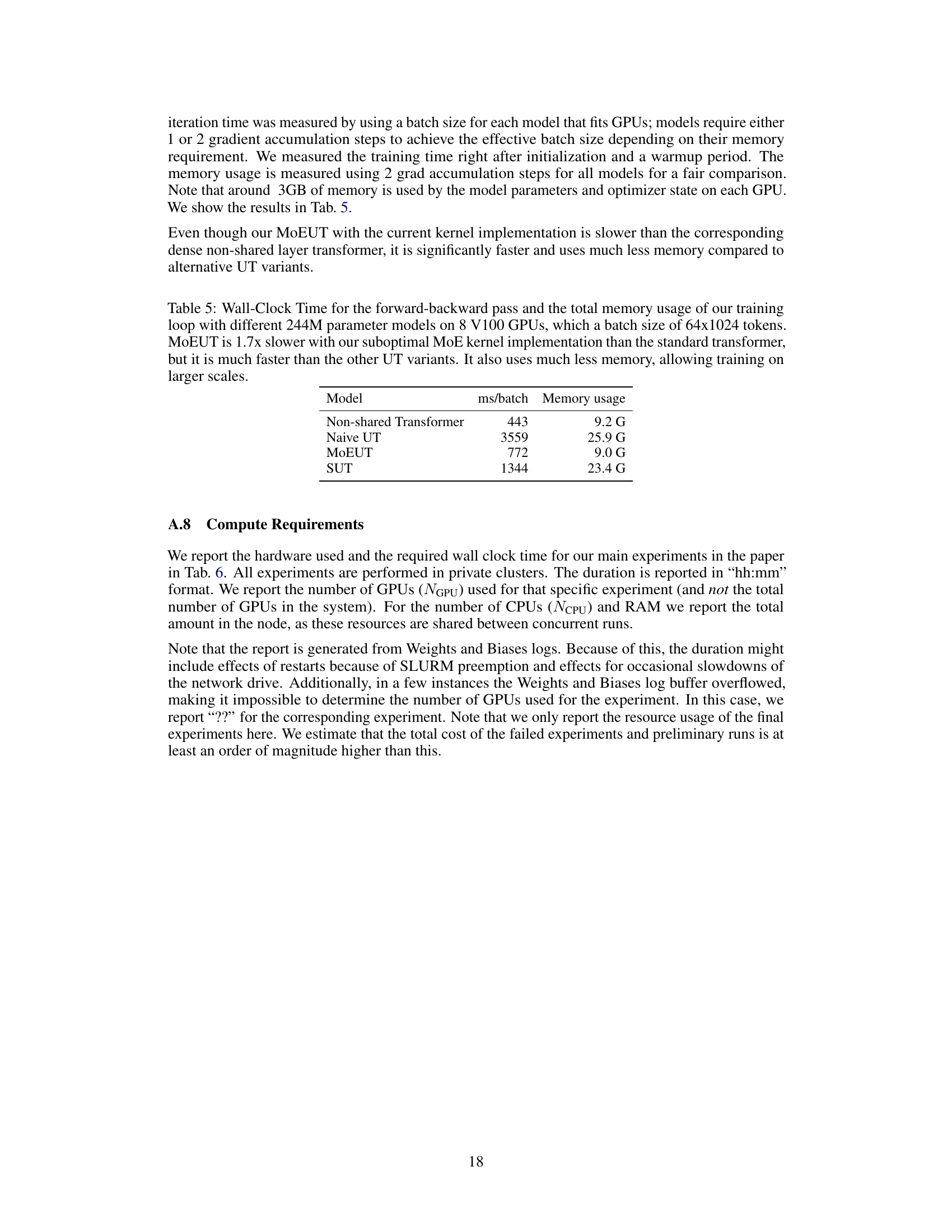

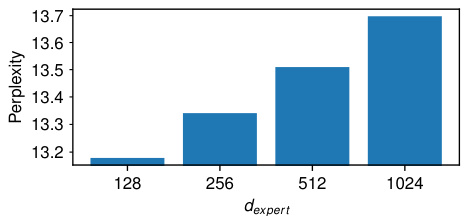

This figure shows the results of an experiment that tested the performance of the 244M MoEUT model on a held-out subset of the C4 dataset. The experiment varied the size of the experts (dexpert) in the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) layer of the model. The results show that the model performs best when the expert size is smallest (128).

The figure shows the perplexity on a held-out subset of the C4 dataset for a 244M parameter MoEUT model with different numbers of active experts (K) in the σ-MoE layer. As the number of active experts increases, the perplexity decreases, indicating improved performance. However, the rate of improvement diminishes as K increases, suggesting diminishing returns.

This figure visualizes the layer preference of different experts in the MoEUT model. The heatmap shows the frequency with which each expert is activated in each layer. Most experts are used across multiple layers, indicating versatility. However, some experts show a strong preference for specific layers, demonstrating the model’s capacity for both shared and specialized computations.

More on tables

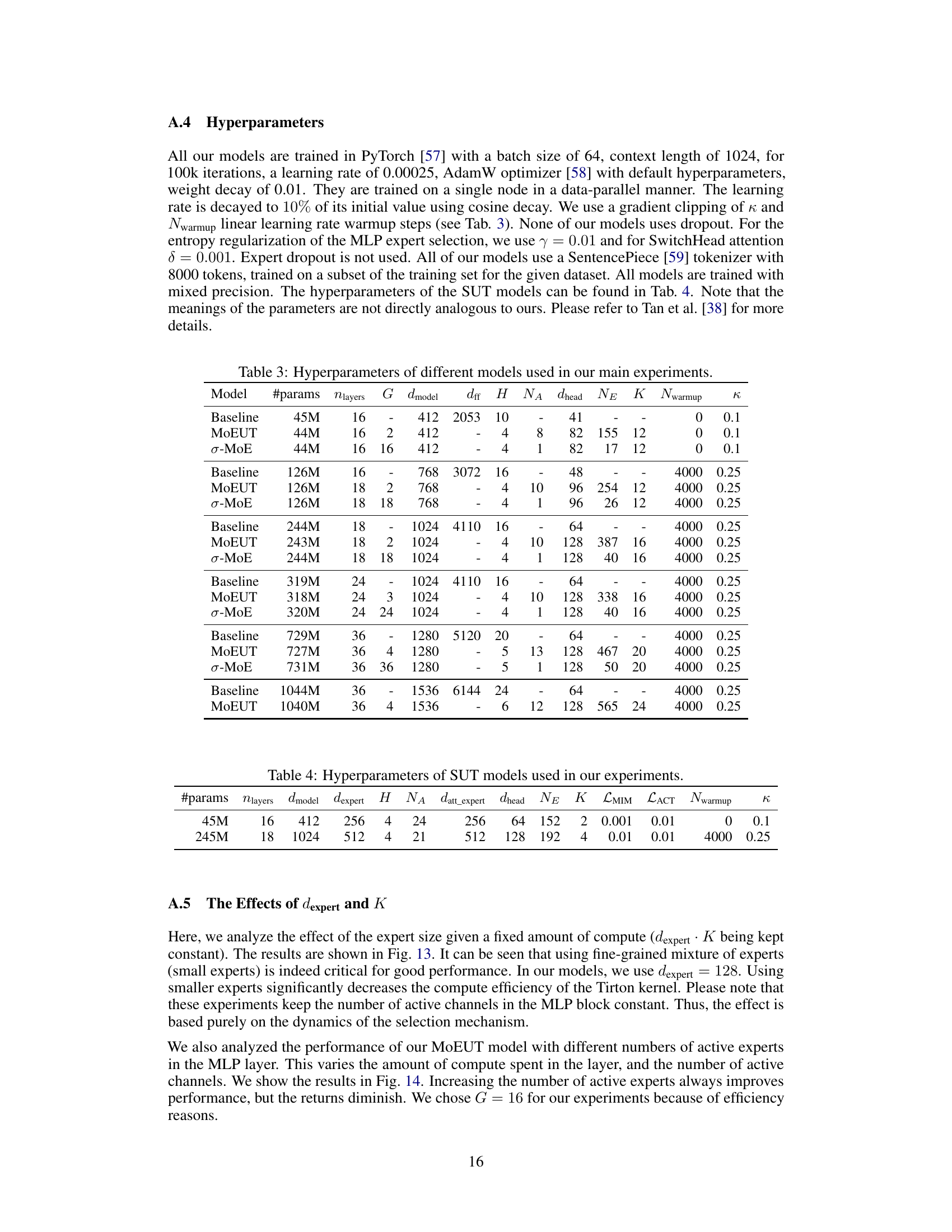

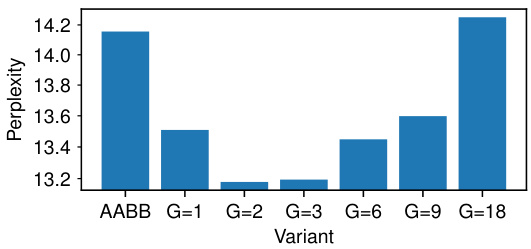

This table presents the results of zero-shot evaluations on six downstream tasks (LAMBADA, BLIMP, CBT, HellaSwag, PIQA, and ARC-E) for different language models (Baseline, MoEUT, SUT, and SUT w.o. ACT) trained on various datasets (C4, peS2o, and SlimPajama). It demonstrates that MoEUT achieves competitive or slightly better performance than the baseline on multiple tasks, highlighting its capabilities as a general-purpose language model.

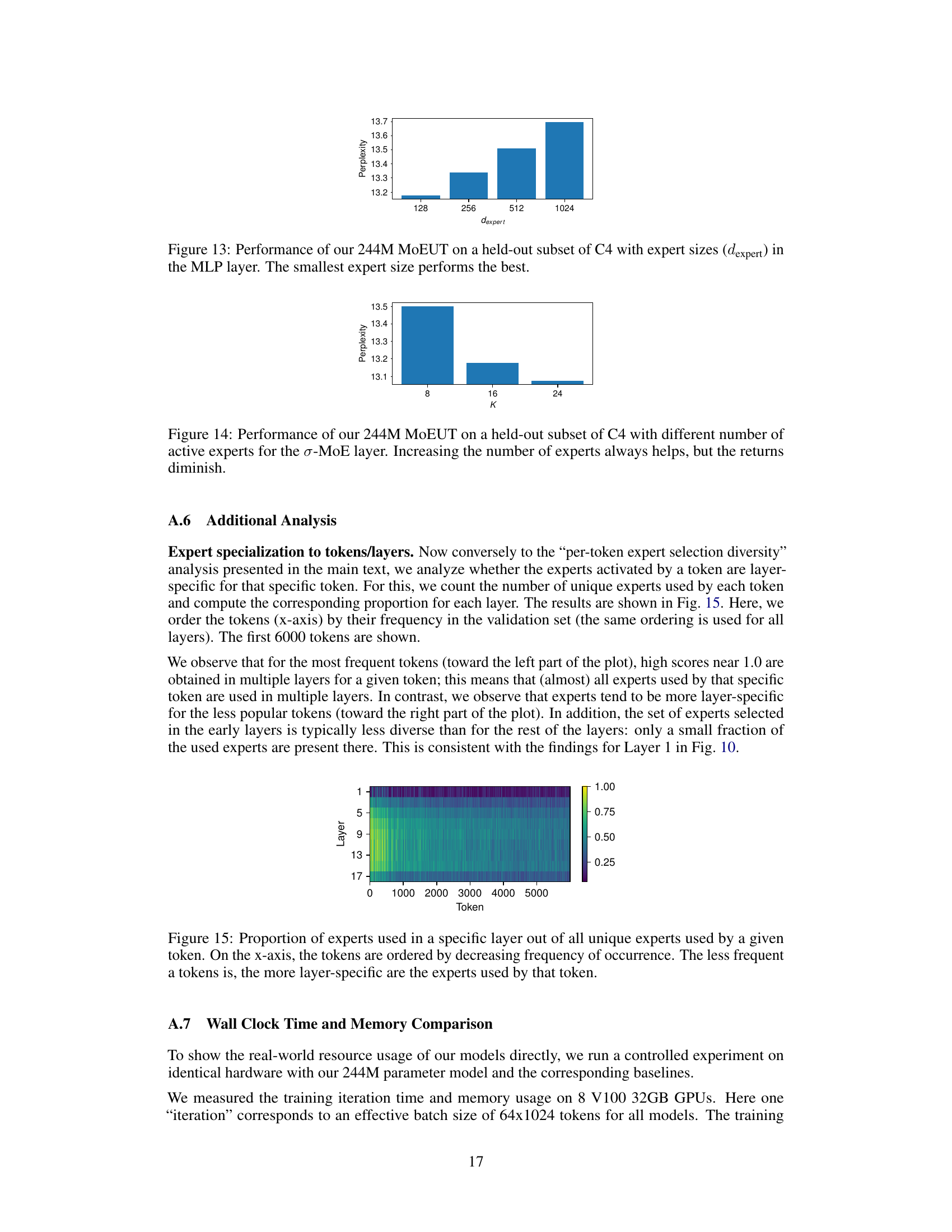

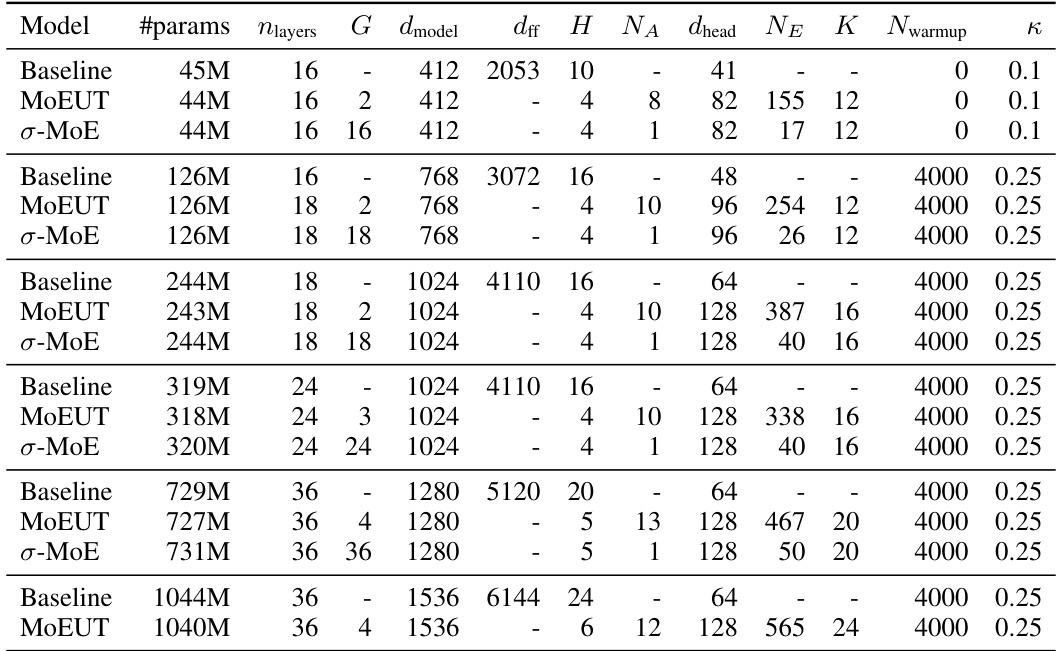

This table lists the hyperparameters used for various models in the main experiments of the paper. It includes different model sizes (indicated by #params), the number of layers (nlayers), group size (G), model dimension (dmodel), feed-forward dimension (dff), number of heads (H), number of attention experts (NA), expert head dimension (dhead), number of feedforward experts (NE), number of active experts (K), number of warmup steps (Nwarmup), and the coefficient for the entropy regularization (κ). The table shows hyperparameters for baseline Transformer models and for MoEUT models with different configurations. It provides a detailed breakdown of the settings used for comparative analysis in the paper.

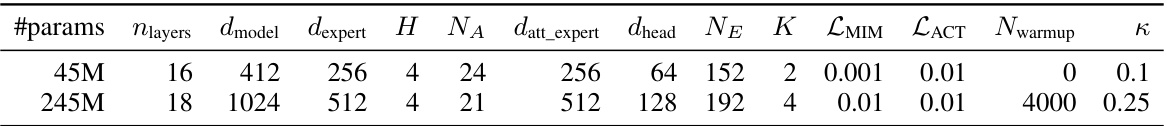

This table shows the hyperparameters used for the Sparse Universal Transformer (SUT) models in the paper’s experiments. It includes the number of parameters, number of layers, model dimension, expert dimension, number of heads, number of attention experts, dimension of attention experts, dimension of head, number of experts in the feedforward layer, number of active experts, coefficient for MLP loss, coefficient for attention loss, number of warmup steps and the kappa value. Note that the meanings of the parameters are not directly analogous to those used for MoEUT models in the paper.

This table presents the results of a controlled experiment to compare the real-world resource usage of different models. It shows the wall-clock time per batch and memory usage on 8 V100 32GB GPUs for four different models, each with 244M parameters. The models compared are a non-shared transformer, a naive universal transformer (UT), the proposed MoEUT, and the SUT. The experiment measures training iteration time and memory usage, demonstrating the improved efficiency of the MoEUT model in terms of training speed and memory usage compared to the other UT variants.

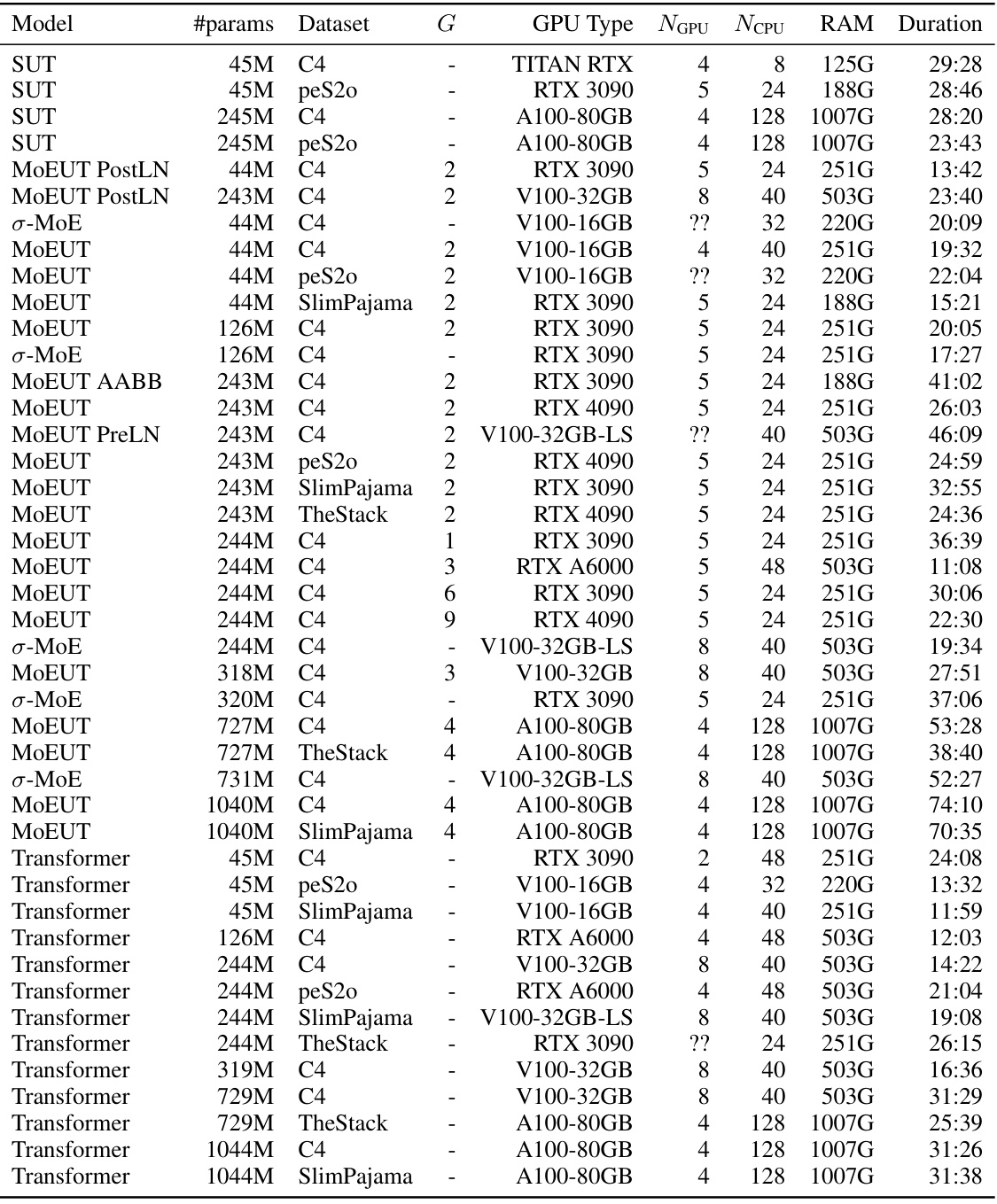

This table details the computational resources used for each experiment conducted in the study. It lists the model, its parameter count, dataset used, layer grouping size (G), GPU type, number of GPUs, CPUs, RAM used, and the duration of the training process. This information aids in understanding the scalability and resource requirements of the MoEUT model compared to other models. Note that some values are marked as ‘?’ indicating missing information.

Full paper#