↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many applications, such as e-commerce and clinical trials, involve online experimentation where the outcome of one unit (e.g., a product or patient) depends on the treatments assigned to others (network interference). Existing methods struggle with this because the action space grows exponentially. The problem is even harder in online settings (multi-armed bandits), which require adaptive treatment decisions to minimize regret (lost revenue/utility).

This paper tackles this challenge by focusing on a sparse network interference model, where the reward of each unit is affected only by a small number of neighbors. They cleverly use discrete Fourier analysis to develop a sparse linear representation of the reward function, which is then exploited to design algorithms for minimizing regret. Importantly, these algorithms work well both when the network is known (e.g., a clear product relationship map exists) and unknown (e.g., complex social networks in clinical trials). Simulation results support the theoretical findings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in online experimentation and causal inference because it tackles the challenging problem of network interference in online settings, a largely unexplored area. It offers novel algorithms with proven low regret, bridges the gap between offline causal inference and online learning, and opens avenues for further research in high-dimensional bandit problems and sparse network analysis.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows a graph representing a sparse network interference model. Nodes represent units, and edges indicate interference between units. The color coding highlights the effect on a single unit (unit 2, colored orange) by its neighbors (colored blue). The gray nodes are not directly connected to unit 2 and do not affect its reward, demonstrating the sparsity of the interference.

Algorithm 1 details the steps involved in the explore-then-commit approach for multi-armed bandits with known network interference. It begins by sampling actions uniformly at random for E time steps to explore the action space. Then, it uses ordinary least squares (OLS) regression on the observed rewards to learn a sparse linear representation of the reward function for each unit. Finally, it selects the action that maximizes the estimated average reward for the remaining T-E time steps.

In-depth insights#

Sparse Network MAB#

The concept of “Sparse Network MAB” blends multi-armed bandit (MAB) problem with the idea of sparse networks. In essence, it tackles the challenge of adaptively assigning actions (treatments) to units (individuals, goods) in a networked system, where the reward of each unit depends on a limited number of its neighbors. This sparsity assumption is crucial because it makes the problem computationally tractable. Without sparsity, the action space grows exponentially, rendering standard MAB algorithms impractical. The key insight is to exploit the local nature of interference; the algorithm can use information about a unit’s immediate neighborhood (its neighbors) to make more informed decisions without needing the entire network structure. This leads to algorithms with provably low regret, which means the algorithm’s cumulative reward is close to the optimal strategy. The sparse network assumption makes the problem more realistic for many real-world applications, such as online advertising or clinical trials, where interference is often localized.

Fourier Analysis Use#

The application of Fourier analysis in this research paper is a key innovation, enabling a linear representation of complex, high-dimensional reward functions in multi-armed bandit problems with network interference. By transforming the reward functions into the Fourier domain, the authors cleverly exploit the sparsity inherent in the sparse network interference model. This transformation allows for efficient learning through linear regression, significantly reducing the dimensionality of the problem and improving computational efficiency. The use of Fourier analysis moves beyond simply representing the functions; it also facilitates the development of provably low-regret algorithms, which is a substantial theoretical contribution. Furthermore, the approach generalizes well to situations where the network structure is unknown, showcasing the robustness and practical applicability of the Fourier-based methodology. This innovative use of Fourier analysis effectively bridges the gap between theoretical analysis and practical algorithm design in a challenging domain.

Regret Bounds#

Regret bounds are crucial in evaluating the performance of online learning algorithms, particularly in multi-armed bandit problems. In the context of network interference, where the reward of an action depends on the actions taken for other units, achieving tight regret bounds is particularly challenging. The paper likely presents regret bounds for its proposed algorithms, demonstrating how the regret scales with key parameters such as the time horizon (T), the number of actions (A), the number of units (N), and the sparsity of network interference (s). High-probability bounds are likely derived, showcasing the algorithms’ performance with strong theoretical guarantees. The analysis might involve techniques from Fourier analysis and linear regression, leveraging the sparse structure of the network to achieve better regret than naive approaches. Comparison to baselines, such as standard MAB algorithms, is also expected, highlighting the improvements provided by the novel algorithms in handling network interference. The bounds likely reveal a trade-off between exploration and exploitation. A tighter bound demonstrates more efficient learning, implying better scalability and robustness in complex settings. The presence of both known and unknown network interference scenarios is likely addressed, leading to distinct regret bounds depending on whether the learner has complete knowledge of the underlying network structure. The scaling of the regret with respect to each parameter is key to understanding the algorithm’s efficiency and practical applicability. For instance, a logarithmic or polylogarithmic dependence on N is a desirable result, indicating scalability to large-scale problems.

Algorithm Analysis#

The Algorithm Analysis section of a research paper would ideally delve into a rigorous mathematical examination of the proposed algorithms’ performance. This involves establishing theoretical guarantees on key metrics like regret, ideally providing upper and lower bounds. A crucial aspect would be demonstrating the algorithm’s scalability with respect to problem size (number of units, actions, time horizon). The analysis should clearly state the assumptions made and how they impact the results. For instance, assumptions of sparsity in network interference significantly influence the achieved regret bounds. The analysis should also compare the algorithm’s performance to existing baselines or optimal solutions, highlighting the improvements and any limitations. A well-written analysis would provide clear explanations of the proof techniques employed, justifying the chosen mathematical tools. Finally, it must clearly articulate the dependencies on various parameters and explain how these impact both computational complexity and the theoretical guarantees.

Future Work#

The paper’s exploration of multi-armed bandits with network interference opens several exciting avenues for future research. Extending the algorithms to handle contextual bandits would enhance their applicability to real-world scenarios where unit characteristics influence rewards. The current work assumes a known or unknown but fixed network structure, so investigating adaptive network learning is crucial for situations where the network evolves over time. Addressing the computational cost of the Lasso, particularly for large-scale problems, remains a significant challenge. While the work presents theoretical regret bounds, empirical evaluation across a wider range of network structures and interference patterns would bolster the findings. Finally, theoretical lower bounds on regret for these types of problems are needed to assess the optimality of current algorithms. Such investigations could significantly improve the efficacy and practicality of online learning techniques in the face of complex interference.

More visual insights#

More on figures

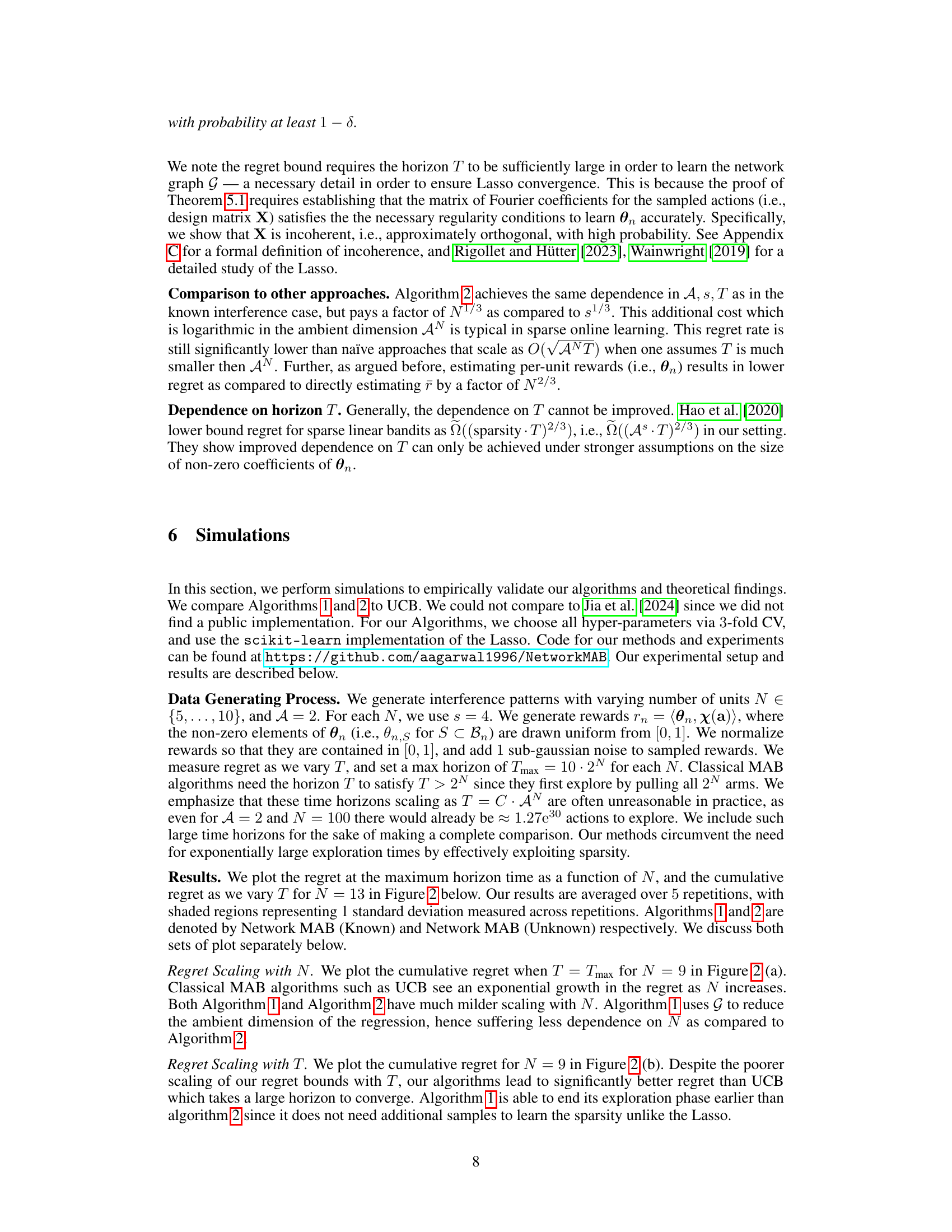

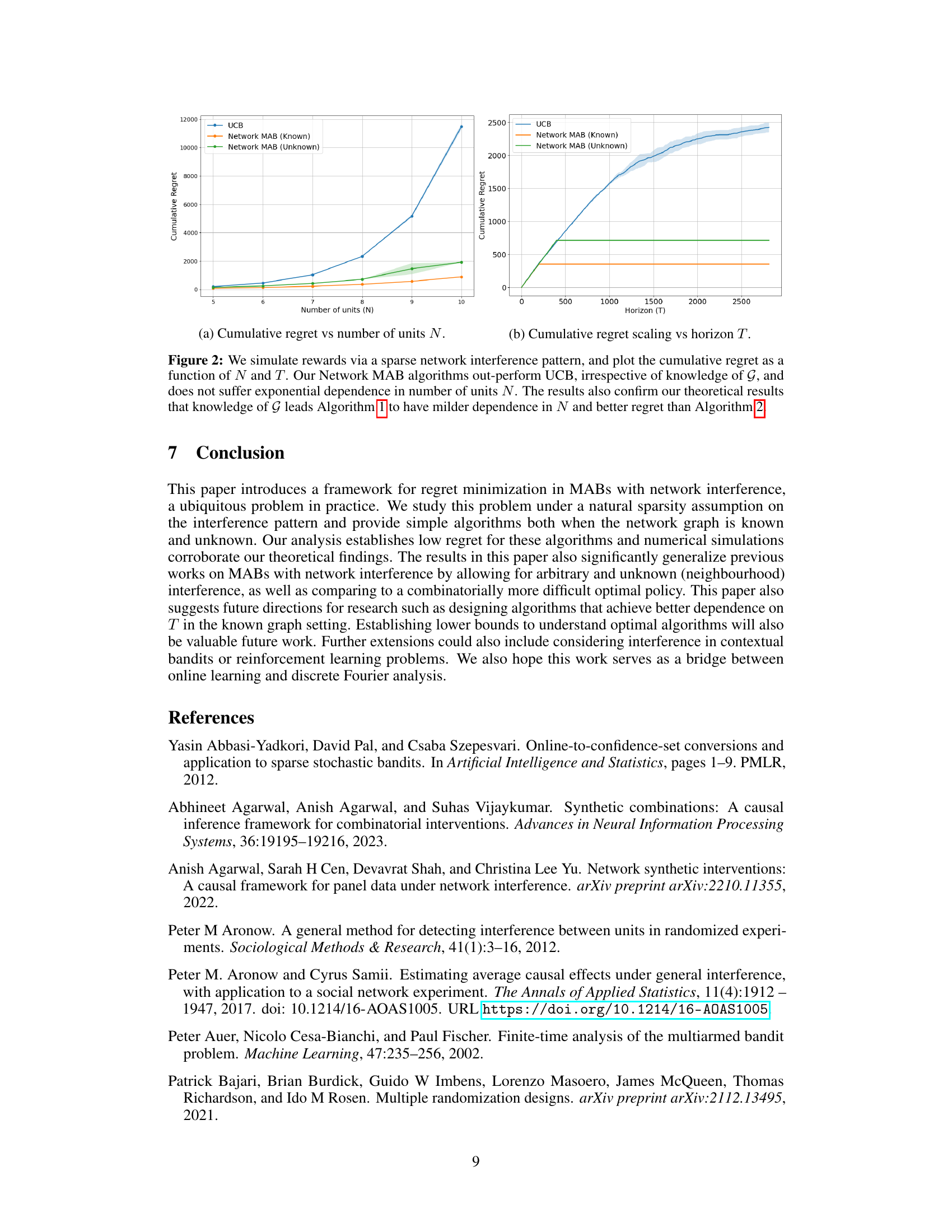

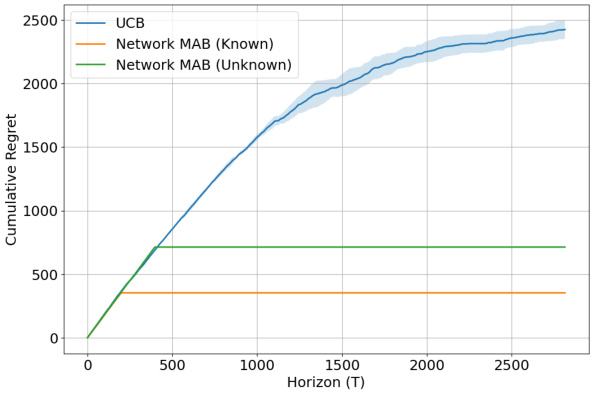

This figure displays the results of simulations comparing the performance of three algorithms for solving the multi-armed bandit problem with network interference: UCB, Network MAB (Known), and Network MAB (Unknown). The left panel shows how cumulative regret scales with the number of units (N) at a maximum time horizon. The right panel shows the cumulative regret over time (T) for a fixed number of units. Both panels demonstrate that the Network MAB algorithms significantly outperform UCB, particularly as the problem size increases.

This figure shows the cumulative regret of three algorithms (UCB, Network MAB (Known), and Network MAB (Unknown)) plotted against the time horizon (T) for a network with 9 units. The Network MAB algorithms demonstrate significantly lower regret compared to the standard UCB approach. Notably, the Network MAB (Known) algorithm, which leverages knowledge of the network structure, exhibits even lower regret than the Network MAB (Unknown) algorithm, highlighting the benefits of incorporating network information into the learning process. The results corroborate the paper’s theoretical findings demonstrating the effectiveness of their proposed algorithms in the presence of sparse network interference.

Full paper#