↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing occupancy prediction methods often struggle with the computational cost of processing massive dense voxel grids, especially considering that most voxels are empty. This paper addresses this issue by proposing a novel approach, termed OPUS, that reframes the problem from traditional dense voxel classification to a direct set prediction task. This means the model predicts only occupied locations and their classes, significantly reducing computational overhead.

OPUS leverages a transformer encoder-decoder architecture with learnable queries to achieve this. To handle the unordered nature of predicted sets, the authors decouple the set-to-set comparison into two parallel subtasks: aligning point distributions using Chamfer distance and assigning semantic labels via nearest-neighbor search. Further improvements are incorporated via coarse-to-fine learning, consistent point sampling, and adaptive re-weighting. The results show OPUS outperforming current state-of-the-art methods on the Occ3D-nuScenes dataset in terms of both accuracy (RayIoU) and speed, achieving real-time performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it offers a novel perspective on occupancy prediction, a crucial task in autonomous driving and robotics. By framing occupancy prediction as a set prediction problem and using a transformer-based architecture, OPUS achieves superior accuracy and real-time performance. This opens new avenues for research in sparse data representation, transformer networks, and efficient 3D scene understanding. Its real-time capability has significant implications for deploying such models in autonomous vehicles.

Visual Insights#

The figure illustrates the proposed occupancy prediction approach as a set prediction problem. Instead of classifying individual voxels, the method predicts sets of occupied point positions (P) and their corresponding semantic classes (C). The set-to-set matching is decoupled into two parts: 1) assessing the similarity between the predicted point distribution (P) and ground truth (Pg) using the Chamfer distance; and 2) aligning the predicted classes with ground truth classes by associating each predicted point with its nearest ground truth point’s class using a function Φ.

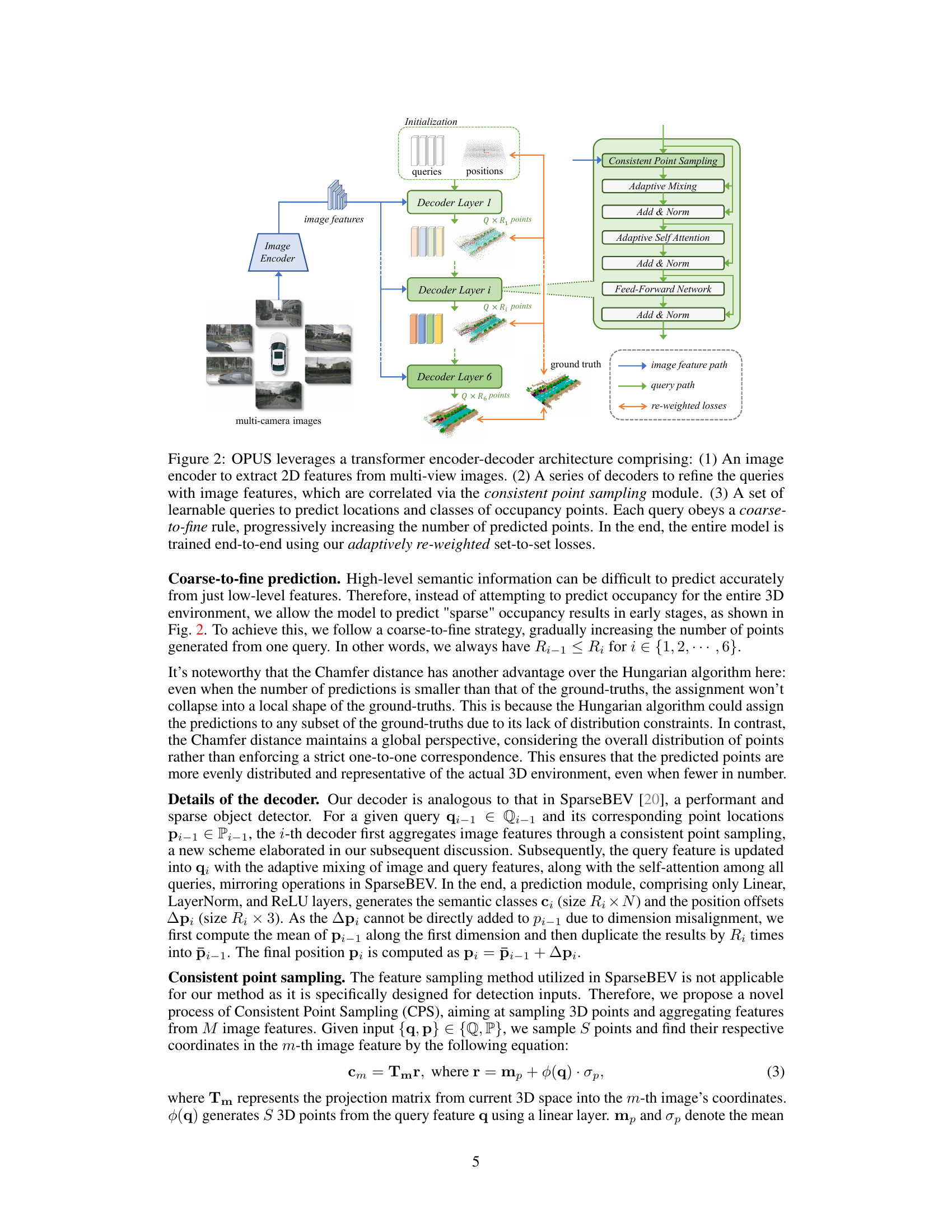

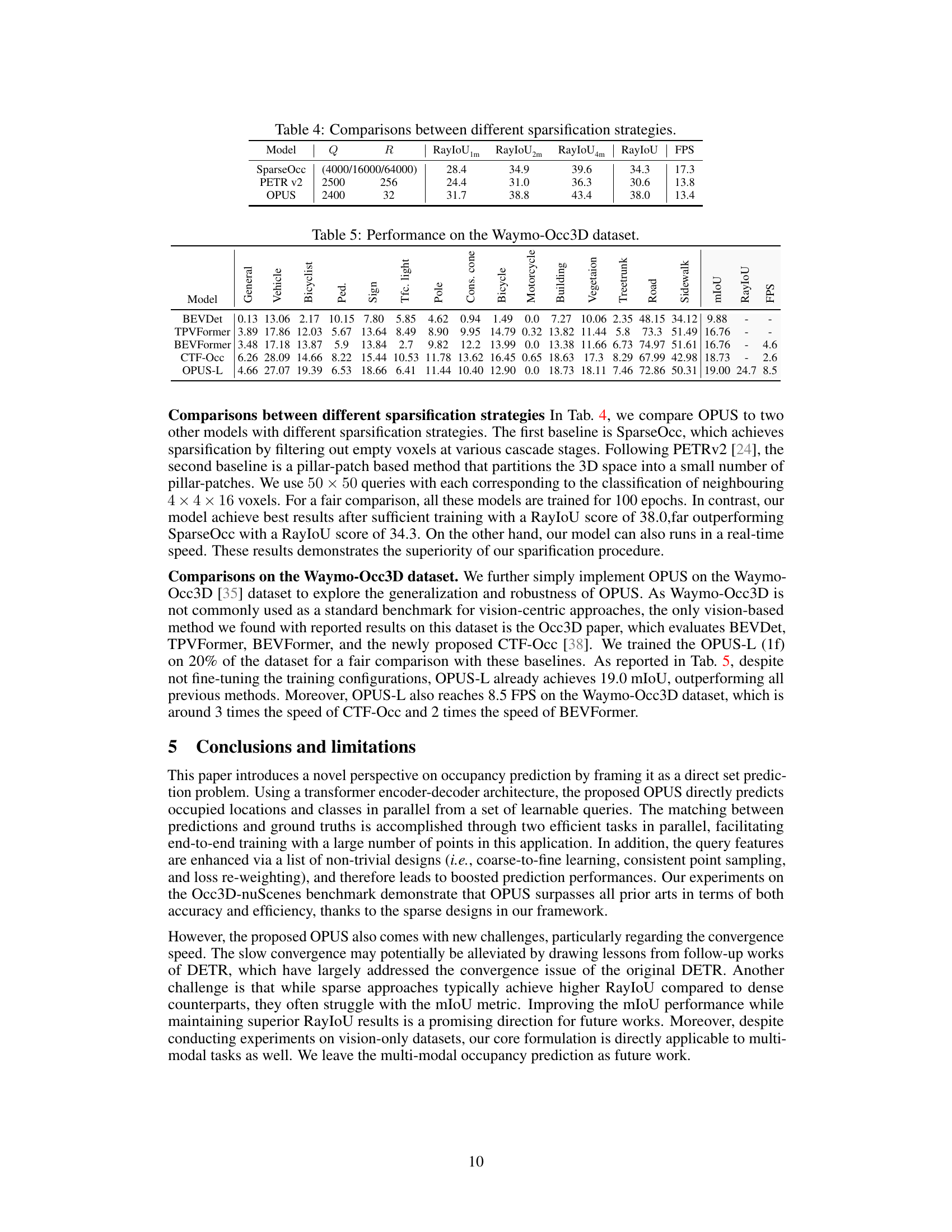

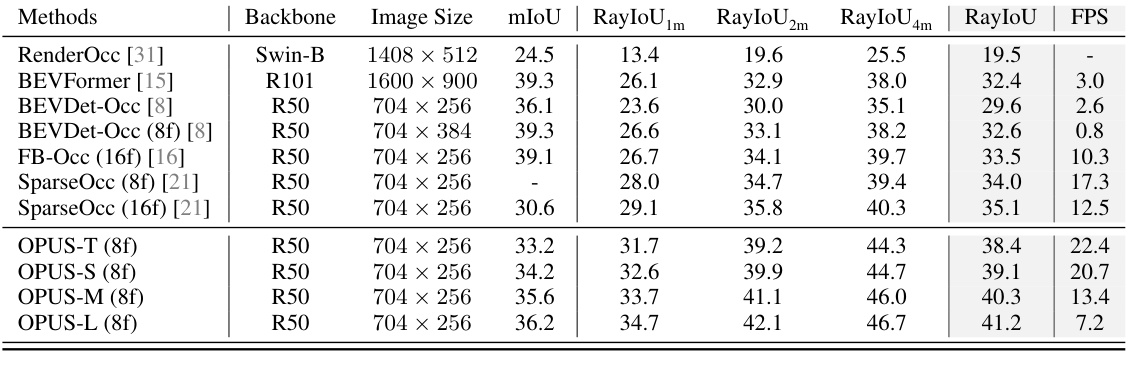

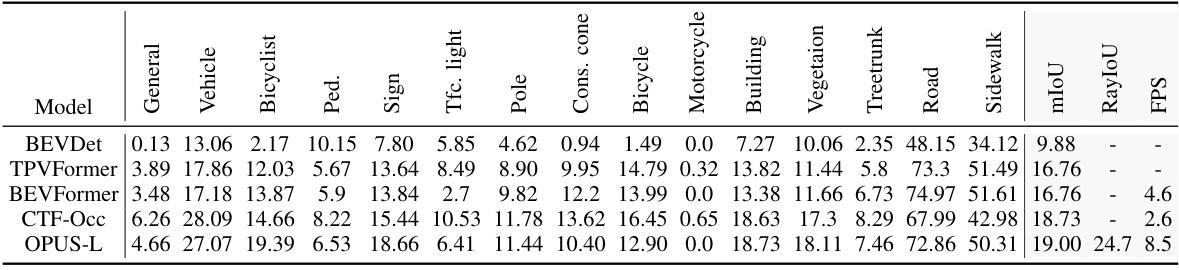

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed OPUS model with several state-of-the-art occupancy prediction methods on the Occ3D-nuScenes dataset. The table shows the performance metrics (mIoU, RayIoU at different distances, and FPS) for each method. It includes both dense and sparse methods, and also compares different versions of OPUS that incorporate more or fewer frames (8f and 16f) in the temporal fusion. FPS values are reported for comparison.

In-depth insights#

Sparse Set Prediction#

Sparse set prediction, a core concept in various machine learning domains, offers a powerful paradigm for handling data with inherent sparsity. It departs from traditional dense methods by focusing on explicitly modeling only the non-zero or relevant elements within a dataset, thereby significantly reducing computational costs and improving efficiency, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional data like 3D point clouds. The key advantage lies in its ability to efficiently capture essential information while ignoring irrelevant data points. This approach is crucial in applications such as occupancy prediction in autonomous driving and object detection in computer vision, where dealing with millions of sparsely distributed points is commonplace. However, challenges exist in effectively handling the variability and orderlessness of sparse sets, requiring innovative loss functions and architectural designs to ensure reliable training and accurate predictions. Further research could explore developing more efficient and robust set representation techniques, and exploring the application of sparse set prediction in novel areas like time series analysis and natural language processing.

Chamfer Dist. Loss#

The Chamfer distance loss function is a crucial component in the OPUS framework for occupancy prediction, addressing the challenge of comparing unordered point sets. Unlike the computationally expensive Hungarian algorithm, it efficiently measures the similarity between the predicted occupancy points and the ground truth by calculating the average minimum distances between points in each set. This allows for end-to-end training of the model, unlike multi-stage approaches requiring complex intermediate steps. By decoupling the supervision into location and class alignment, the Chamfer distance loss simplifies the training process, focusing solely on point distribution accuracy. The use of this loss is key to scaling the set prediction task to large magnitudes, handling thousands of voxels in an efficient manner and significantly contributing to the impressive efficiency and performance of OPUS.

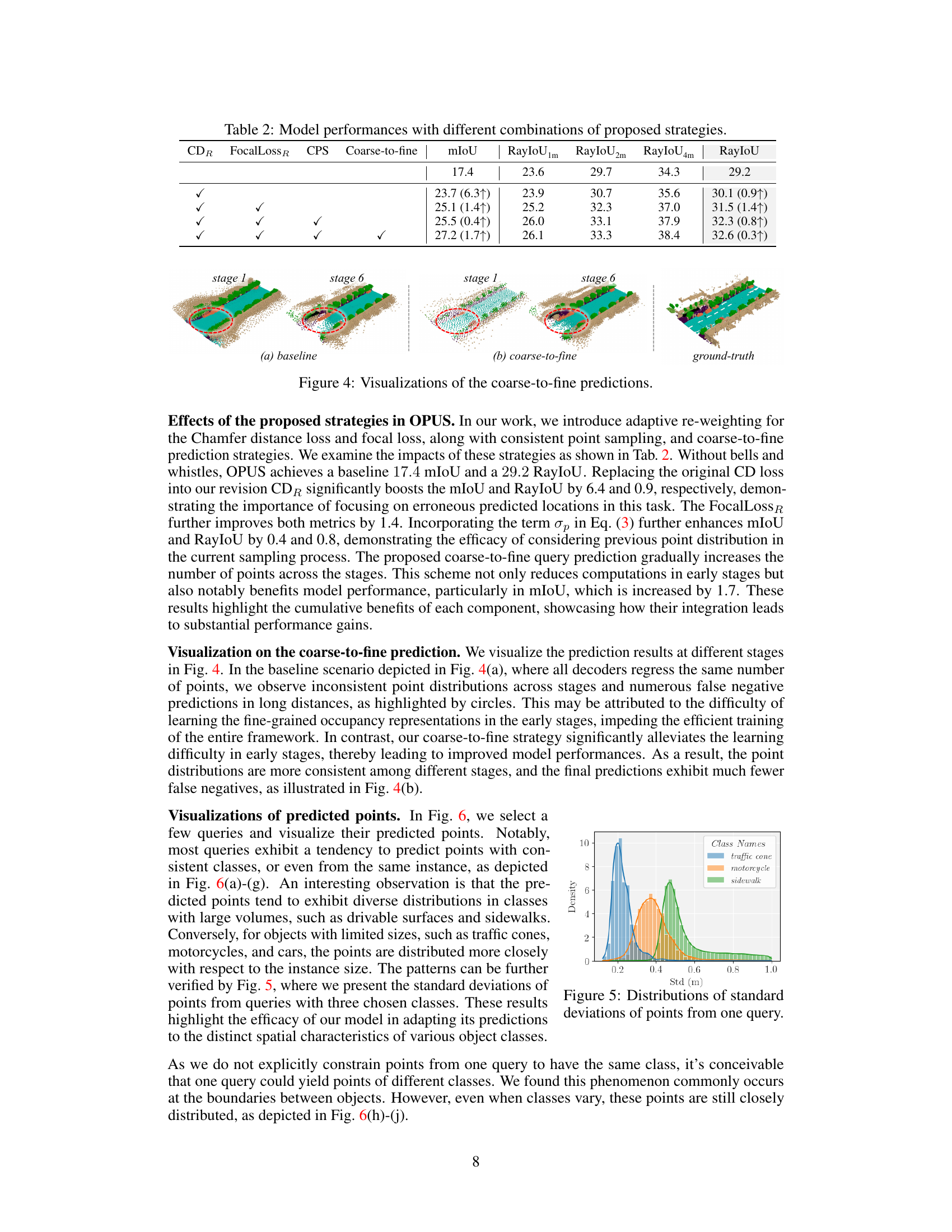

Coarse-to-Fine Learn#

A coarse-to-fine learning strategy in the context of occupancy prediction is a powerful technique to gradually increase the complexity of the prediction task. It starts by initially focusing on learning high-level semantic information and overall scene structure. Subsequently, it refines the prediction by incorporating more detailed geometric information and precise point locations. This approach is particularly beneficial in scenarios with highly sparse data, where a dense prediction would be computationally expensive and prone to overfitting on noise. By starting with a simpler task, the model can establish a robust foundational understanding before tackling the intricate details. The coarse stage might predict a few key points or regions which represent larger objects. Progressively, subsequent stages increase the granularity of prediction to capture finer details like individual points or small objects. This approach is not only more computationally efficient but also often leads to more accurate and robust predictions by mitigating the negative effects of noise and data sparsity.

Real-time Inference#

Real-time inference in the context of occupancy prediction is crucial for autonomous driving applications. The speed at which predictions are generated directly impacts the responsiveness and safety of the system. A fast inference time allows the vehicle to react promptly to changes in its environment, avoiding potential collisions or accidents. Factors that influence real-time capability include model complexity (size and architecture), hardware used for processing, and the efficiency of algorithms. Balancing model accuracy with the speed of inference is a core challenge. Approaches such as model sparsification or quantization are often employed to accelerate prediction while minimizing accuracy loss. The specific FPS (frames per second) achieved is a key benchmark indicating real-time performance, with higher FPS suggesting better responsiveness. Real-time is not merely a matter of frame rates, but encompasses factors like latency and throughput. The system must be capable of handling the real-world data stream continuously without significant delays, to ensure effective and reliable operation. Therefore, evaluation must go beyond FPS and also include latency measurements to fully capture real-time performance.

Future of Occupancy#

The future of occupancy prediction hinges on addressing limitations of current methods. While impressive advancements leverage deep learning and sparse representations, challenges remain in handling highly dynamic environments and achieving perfect accuracy. Future work will likely focus on multi-modal integration, combining LiDAR, camera, and radar data for more robust scene understanding. This requires sophisticated sensor fusion techniques and more advanced model architectures that can efficiently process and integrate diverse data sources. Another critical area will be improving computational efficiency, making real-time predictions feasible for various applications like autonomous driving and robotics. Furthermore, research should explore methods to better handle uncertainty by explicitly modeling noise and ambiguity. This includes addressing limitations in data annotation, where sparsely sampled spaces or errors in labeling can significantly impact model performance. The development of new evaluation metrics beyond traditional IoU will be necessary to accurately gauge progress in a domain marked by sparsity and high dimensionality. Finally, attention should be paid to ethical implications, particularly in scenarios where occupancy prediction directly impacts safety-critical systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

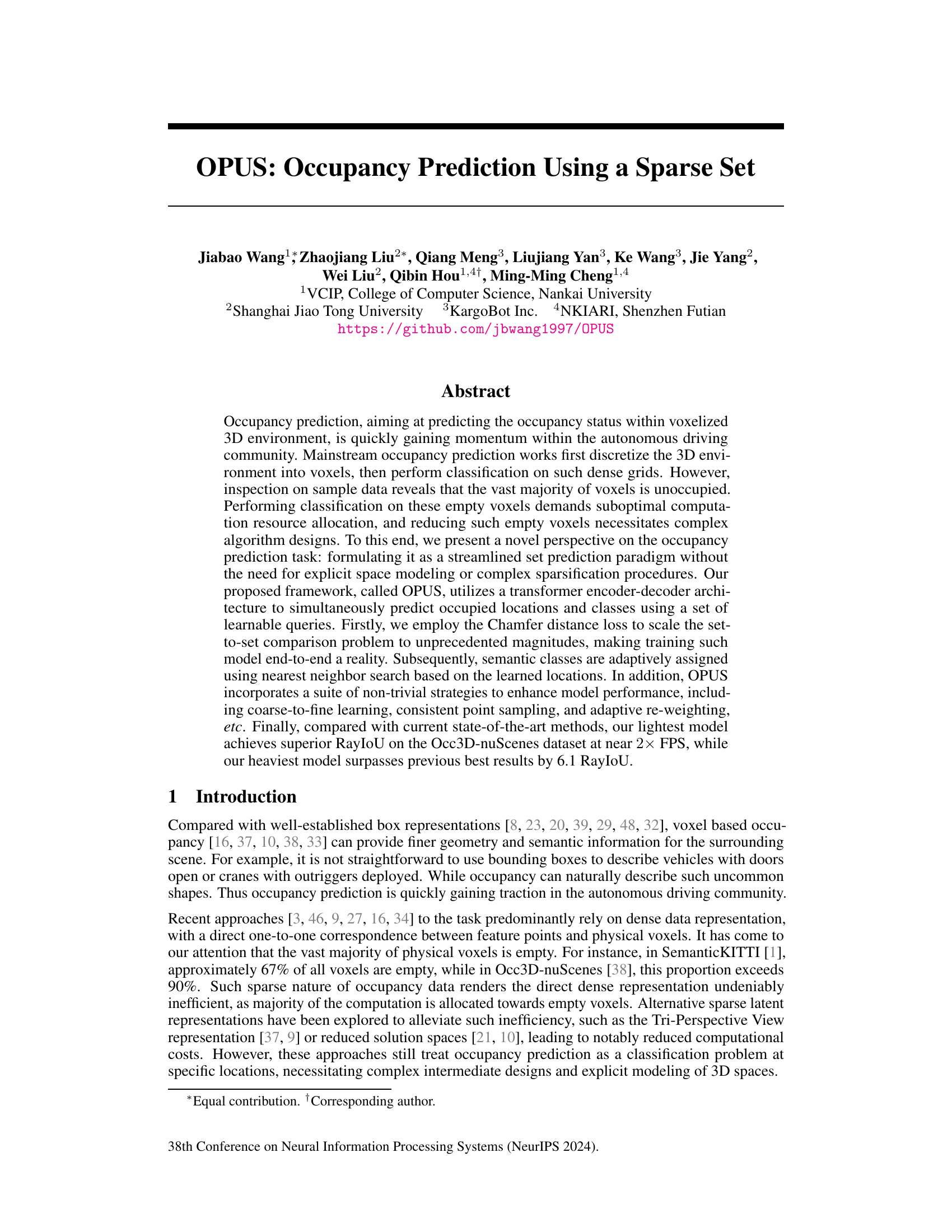

The figure illustrates the OPUS architecture. It shows a transformer encoder-decoder model that takes multi-camera images as input. The encoder extracts 2D features. These features are then processed by a series of decoders, which refine queries using a consistent point sampling module. The decoders output a set of learnable queries that predict the locations and classes of occupancy points. Each query follows a coarse-to-fine approach, gradually increasing the number of predicted points. The entire model is trained end-to-end using adaptively re-weighted set-to-set losses.

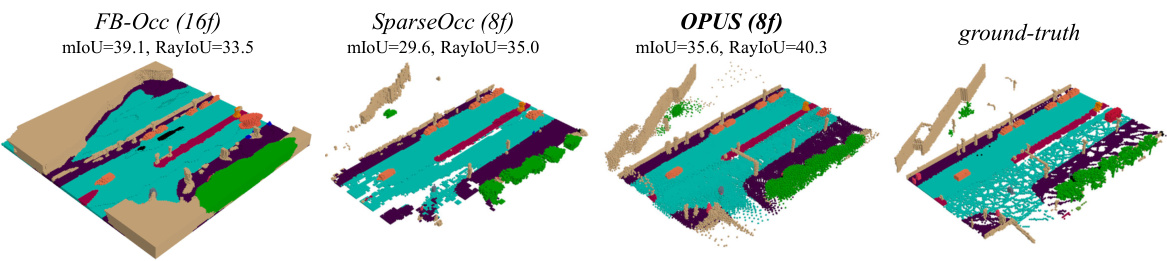

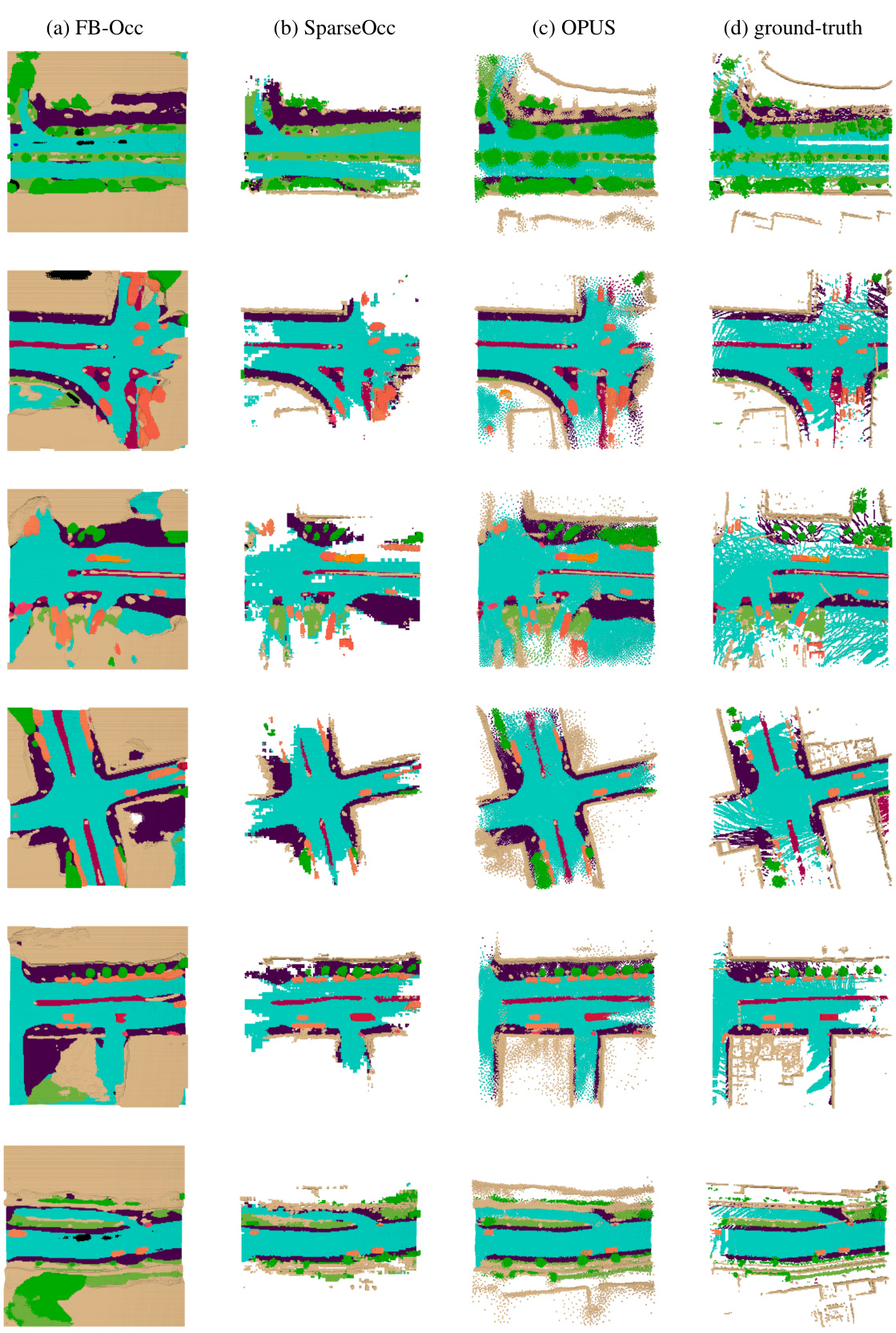

This figure presents a visual comparison of occupancy predictions generated by three different methods: FB-Occ, SparseOcc, and OPUS. It shows the predicted occupancy maps alongside the ground truth, highlighting the differences in prediction accuracy and sparsity. FB-Occ produces a dense prediction, SparseOcc provides a more sparse result but with missing parts, while OPUS strikes a balance by generating a sparse prediction that is more accurate and complete.

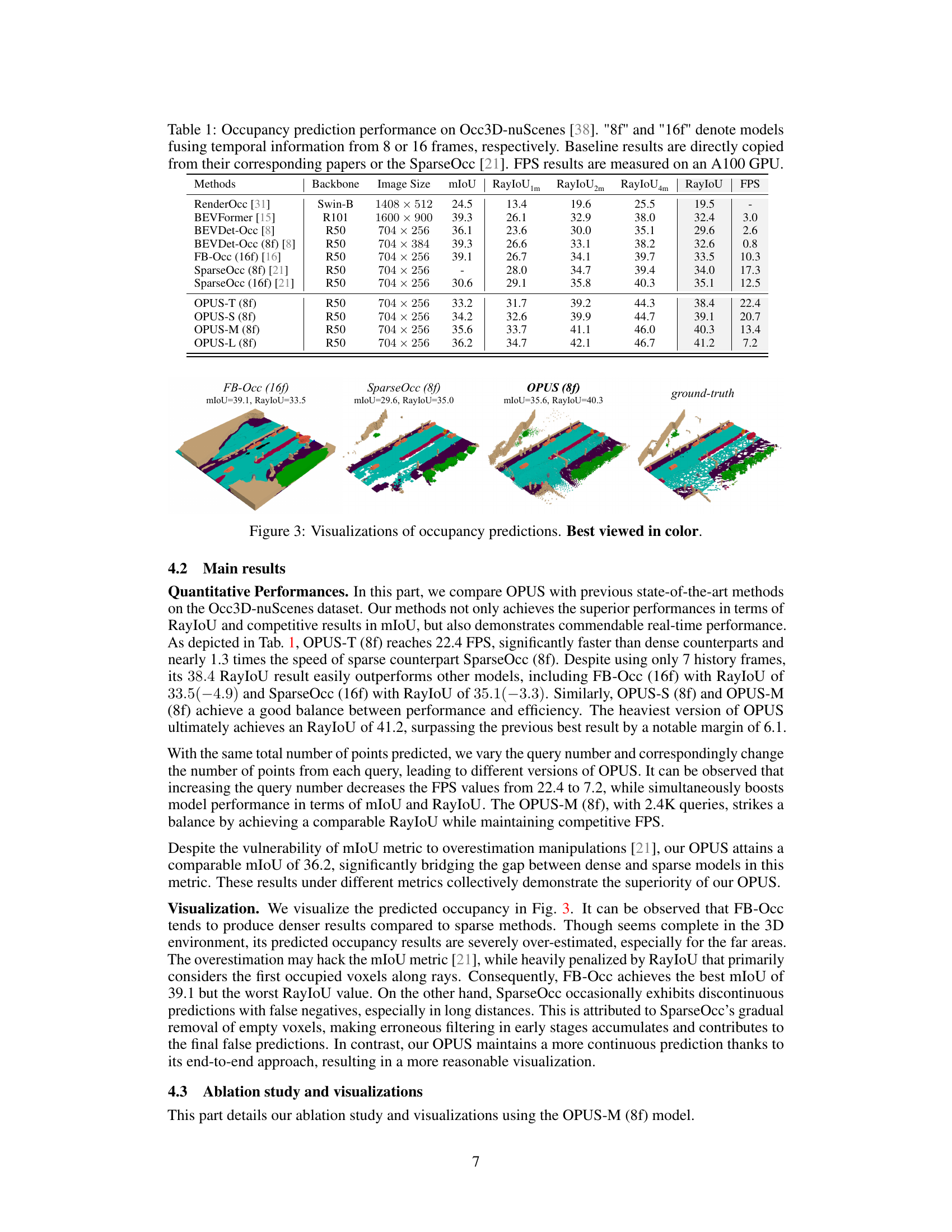

This figure visualizes the impact of the coarse-to-fine prediction strategy on occupancy prediction. It shows a comparison between a baseline approach (a) where all decoder layers regress the same number of points, and a coarse-to-fine approach (b) where the number of points gradually increases across the decoder layers. The ground truth is shown in (c). The baseline approach shows inconsistent point distributions across stages and a number of false negative predictions. The coarse-to-fine approach alleviates these issues, resulting in more consistent point distributions and fewer false negatives.

This figure shows the distribution of standard deviations of the distances of points predicted by a single query. The x-axis represents the standard deviation (in meters) of the distances. The y-axis represents the density of queries with that standard deviation. Three different classes are shown: traffic cone, motorcycle, and sidewalk. The distributions are different for each class, reflecting the different spatial extents of these objects. Traffic cones have the smallest standard deviations, while sidewalks have the largest, indicating that points belonging to the same traffic cone are clustered more tightly than points belonging to a sidewalk. This visualizes the way the model adapts its point prediction patterns based on the spatial characteristics of the objects.

This figure visualizes the points predicted by different queries. Each subfigure shows a different class or a combination of classes. It highlights how the model focuses on different regions and details for various object categories, generating points that cluster together with consistent classes or from the same instance. It also demonstrates how points are distributed more diversely for larger areas like sidewalks and drivable surfaces, and are concentrated for smaller objects like traffic cones. The legend explains the color coding for various categories.

This figure visualizes points predicted by different queries in OPUS. Each color represents a different query, and the spatial distribution of points within each color group reflects the points predicted by that specific query. The figure demonstrates that queries tend to predict clusters of points with consistent semantic labels, and the density of points within each cluster varies depending on the object class. In some cases, a single query might predict points belonging to multiple classes, particularly at boundaries between objects.

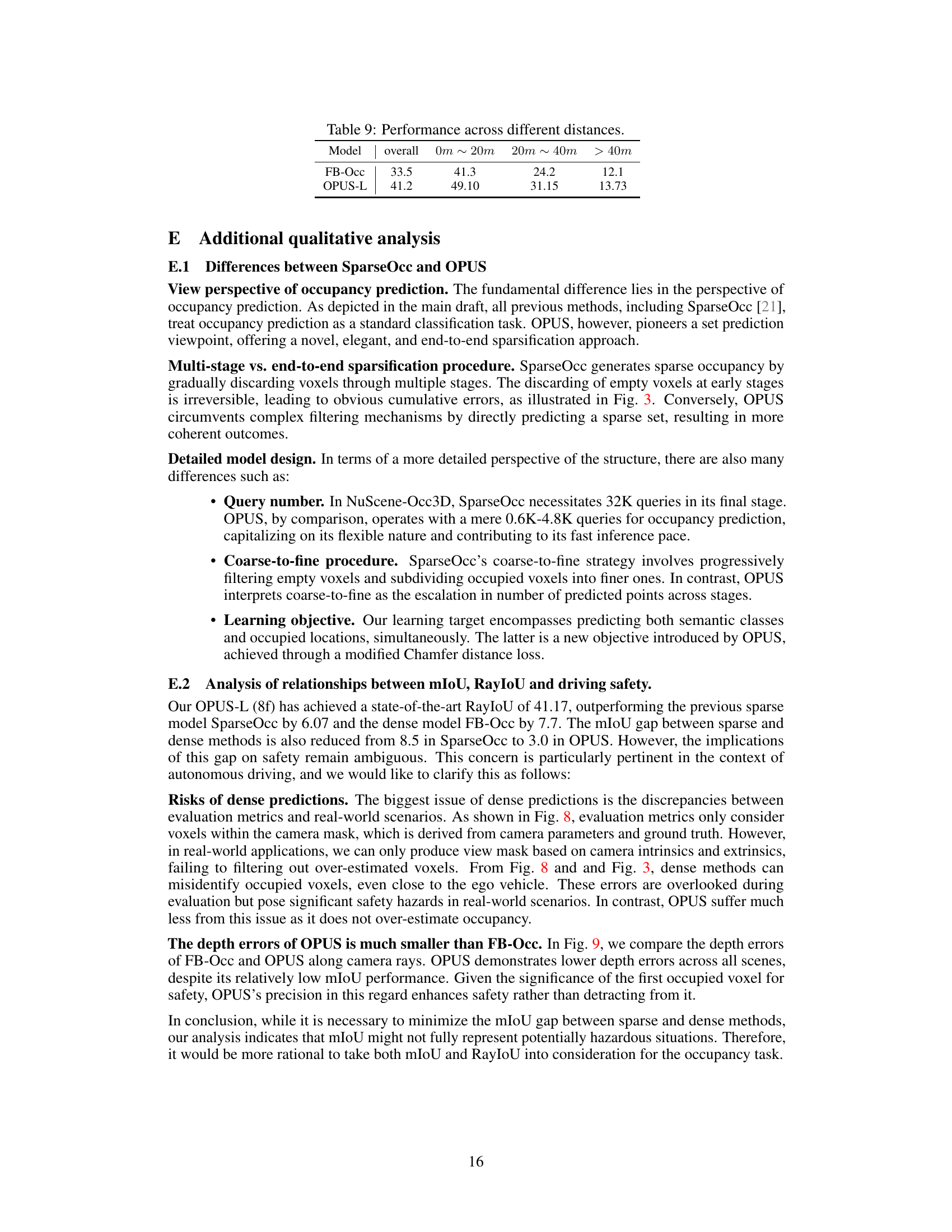

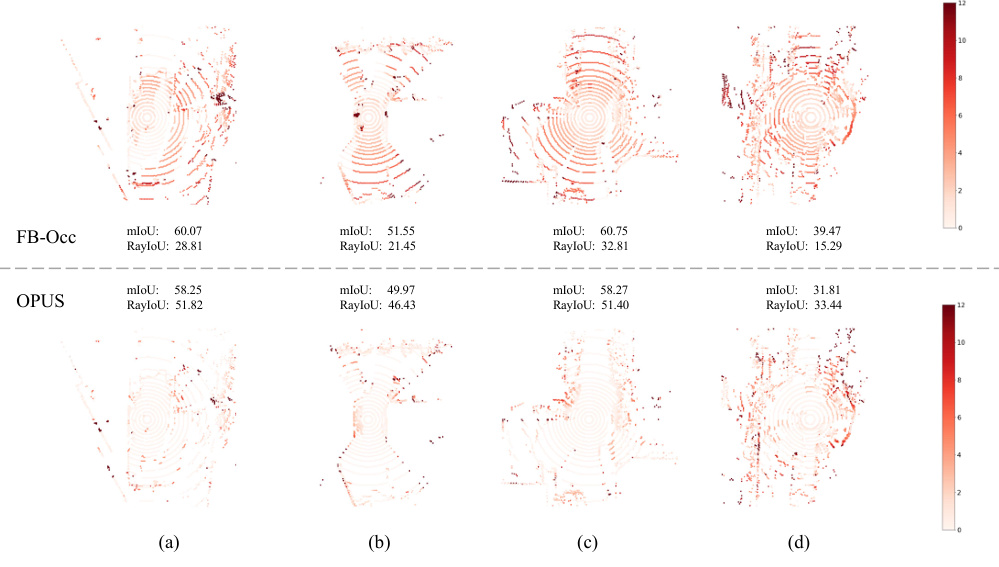

This figure illustrates a safety concern related to the discrepancy between evaluation metrics and real-world scenarios in occupancy prediction. It shows how dense prediction methods (like FB-Occ) can overestimate occupancy, leading to false positives near the ego vehicle that are filtered out during evaluation but pose a significant safety risk in real-world applications. In contrast, the sparse prediction method (OPUS) mitigates this risk due to its more accurate estimations.

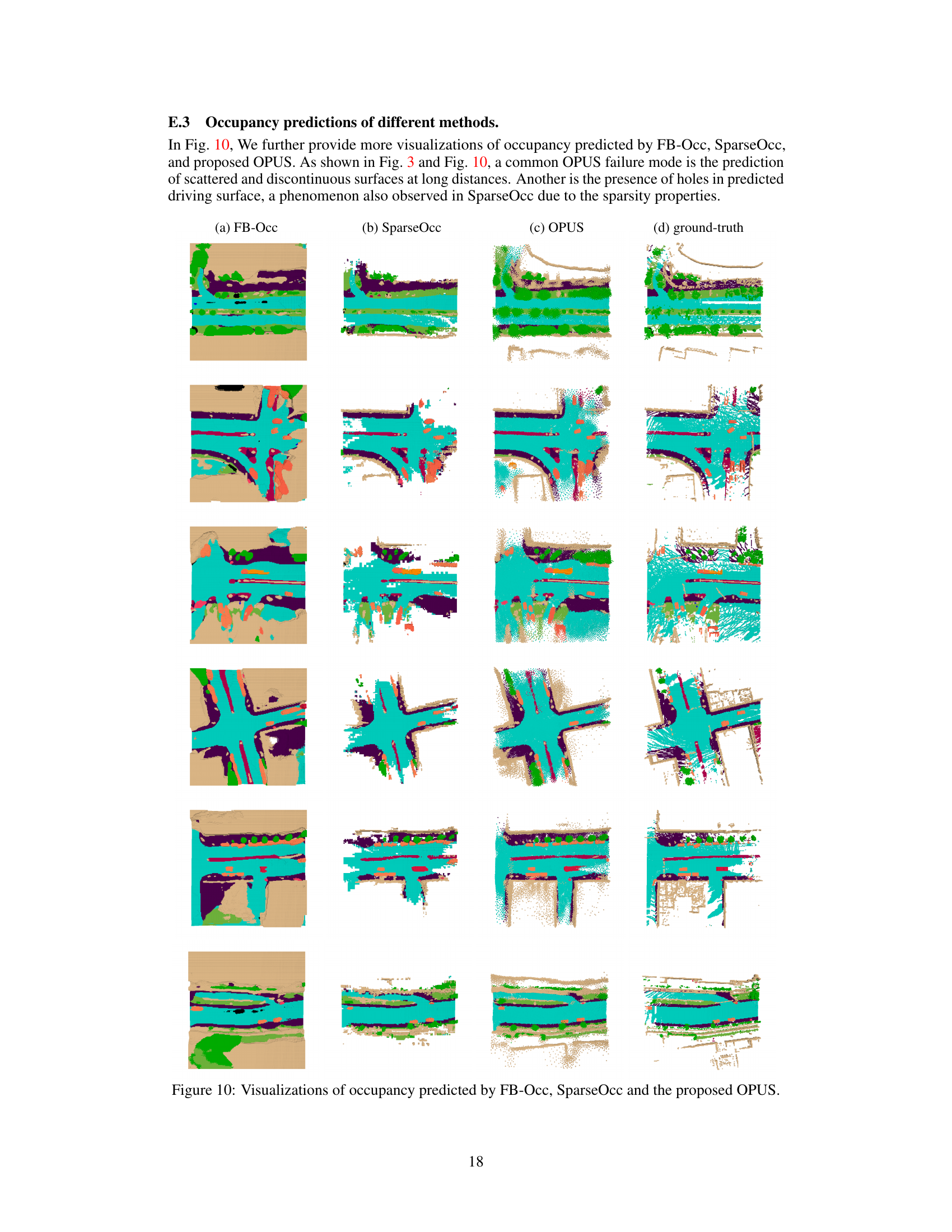

This figure visualizes the occupancy prediction results from three different methods: FB-Occ, SparseOcc, and OPUS. For each method, four sample scenes are shown, along with their corresponding ground truth occupancy maps. The visualizations highlight the differences in the prediction quality and density of points between the three methods, showing that OPUS provides a more balanced representation, avoiding the overestimation of FB-Occ and the discontinuity of SparseOcc.

This figure shows a comparison of occupancy prediction results from three different methods: FB-Occ, SparseOcc, and the proposed OPUS method. Each row represents a different scene. The ground truth is shown in the last column for reference. The visualizations highlight the differences in prediction quality and sparsity between the methods. FB-Occ tends to produce denser results with more overestimation than SparseOcc and OPUS. SparseOcc shows some missing details due to its sparse representation, while OPUS produces an intermediate result between the two in terms of detail and sparsity.

More on tables

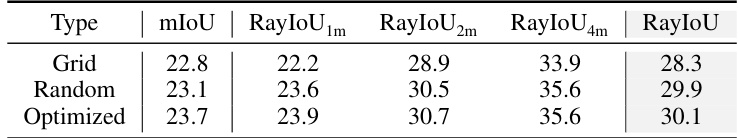

This table shows the performance comparison of three different initialization methods for the initial point locations (Pº) in the OPUS model. The three methods are: Grid initialization (uniformly sampling points in BEV space), Random initialization (randomly sampling points in 3D space), and Optimized initialization (random initialization with supervision from ground truth using Chamfer Distance loss). The table presents the mIoU and RayIoU (at different distances: 1m, 2m, 4m) for each initialization method, showing that the ‘Optimized’ method yields the best performance.

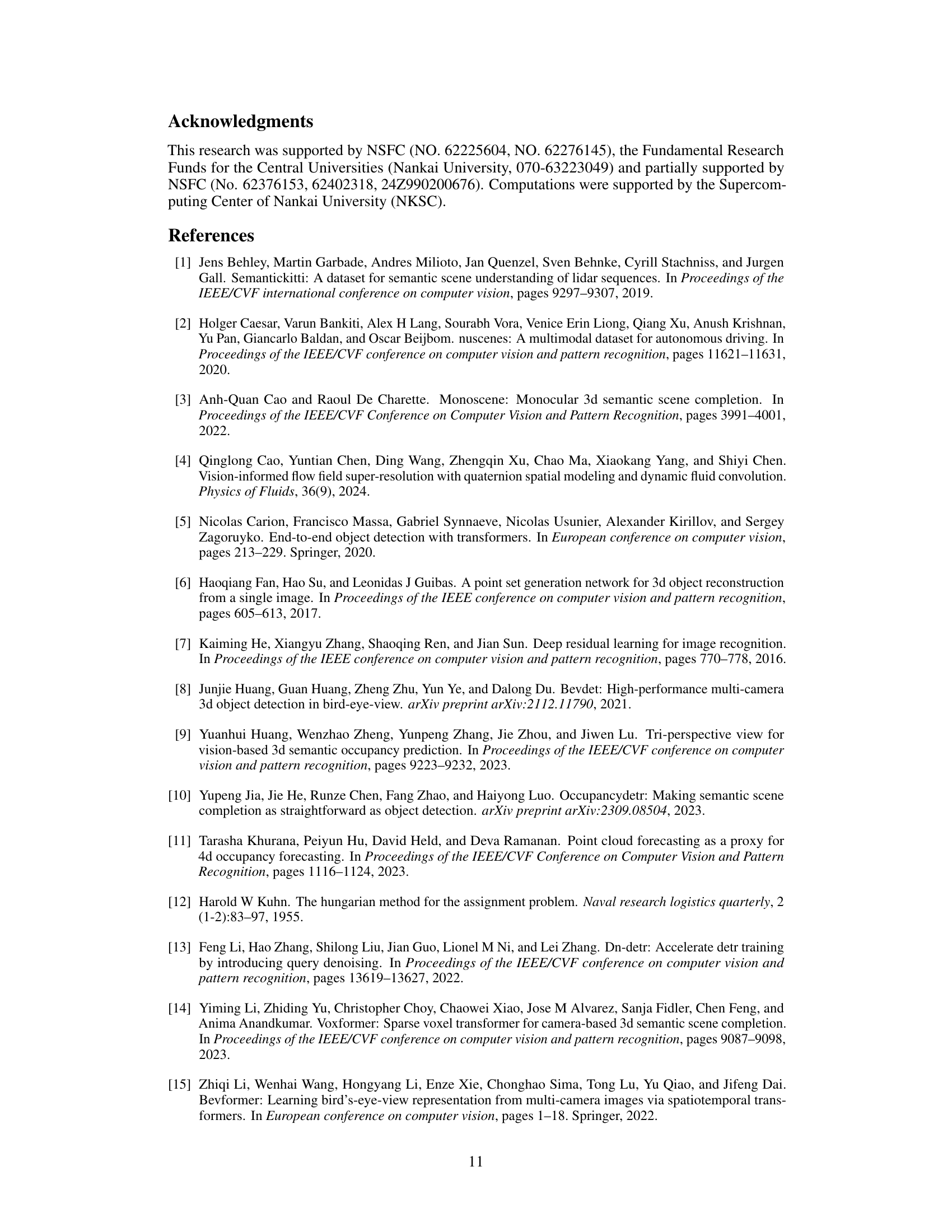

This table compares the performance of OPUS against two other models employing different sparsification strategies: SparseOcc, which uses a multi-stage approach to filter out empty voxels, and PETR v2, which uses a pillar-patch-based method. The metrics used for comparison include RayIoU at various distance thresholds (1m, 2m, 4m) and the overall RayIoU, as well as FPS (frames per second). The number of queries (Q) and the number of points predicted per query (R) are also shown for each method. The results demonstrate OPUS’s superior performance.

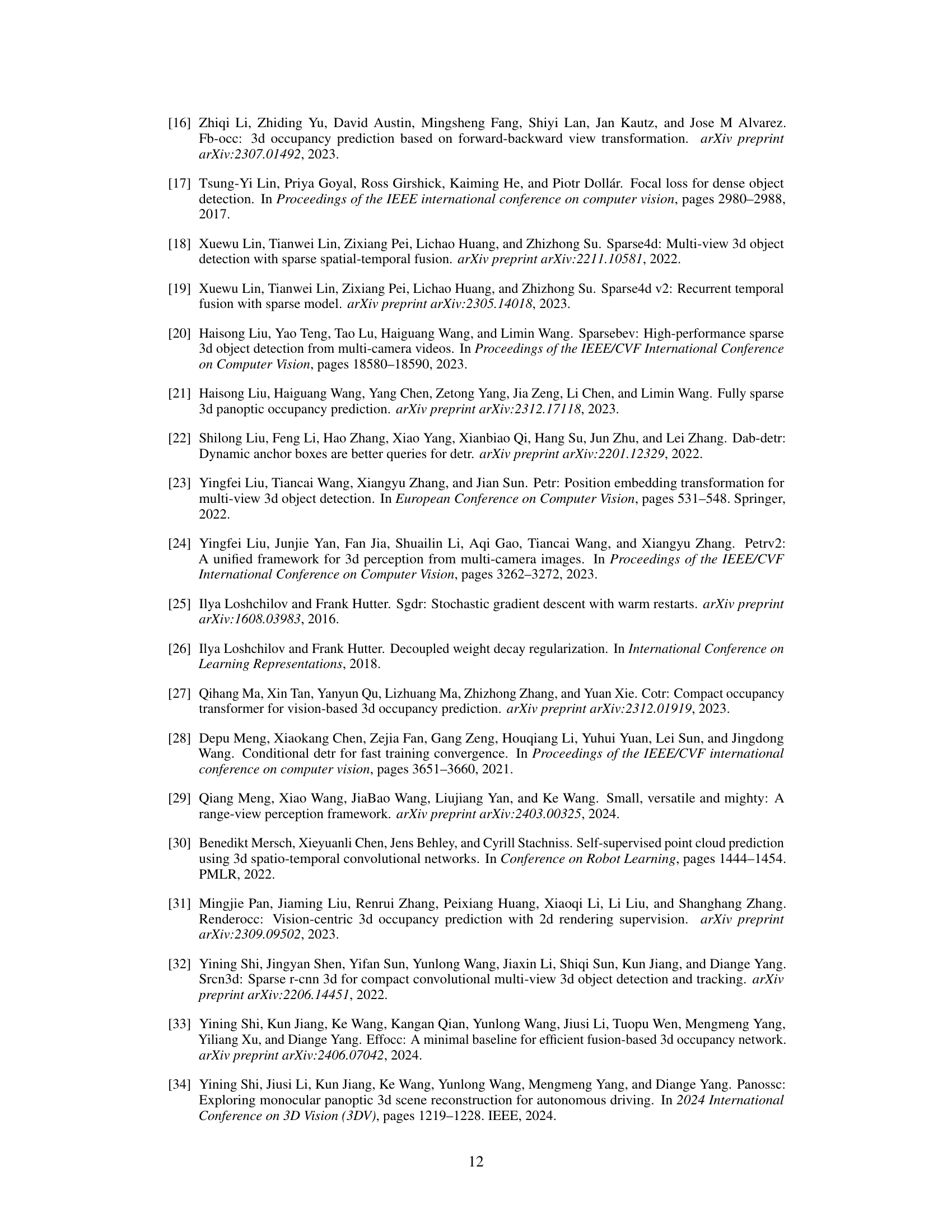

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the OPUS model’s performance against other state-of-the-art occupancy prediction methods on the Waymo-Occ3D dataset. The results are broken down by semantic class (e.g., vehicle, pedestrian, bicycle) and include metrics such as mIoU and RayIoU, showing the model’s accuracy and efficiency.

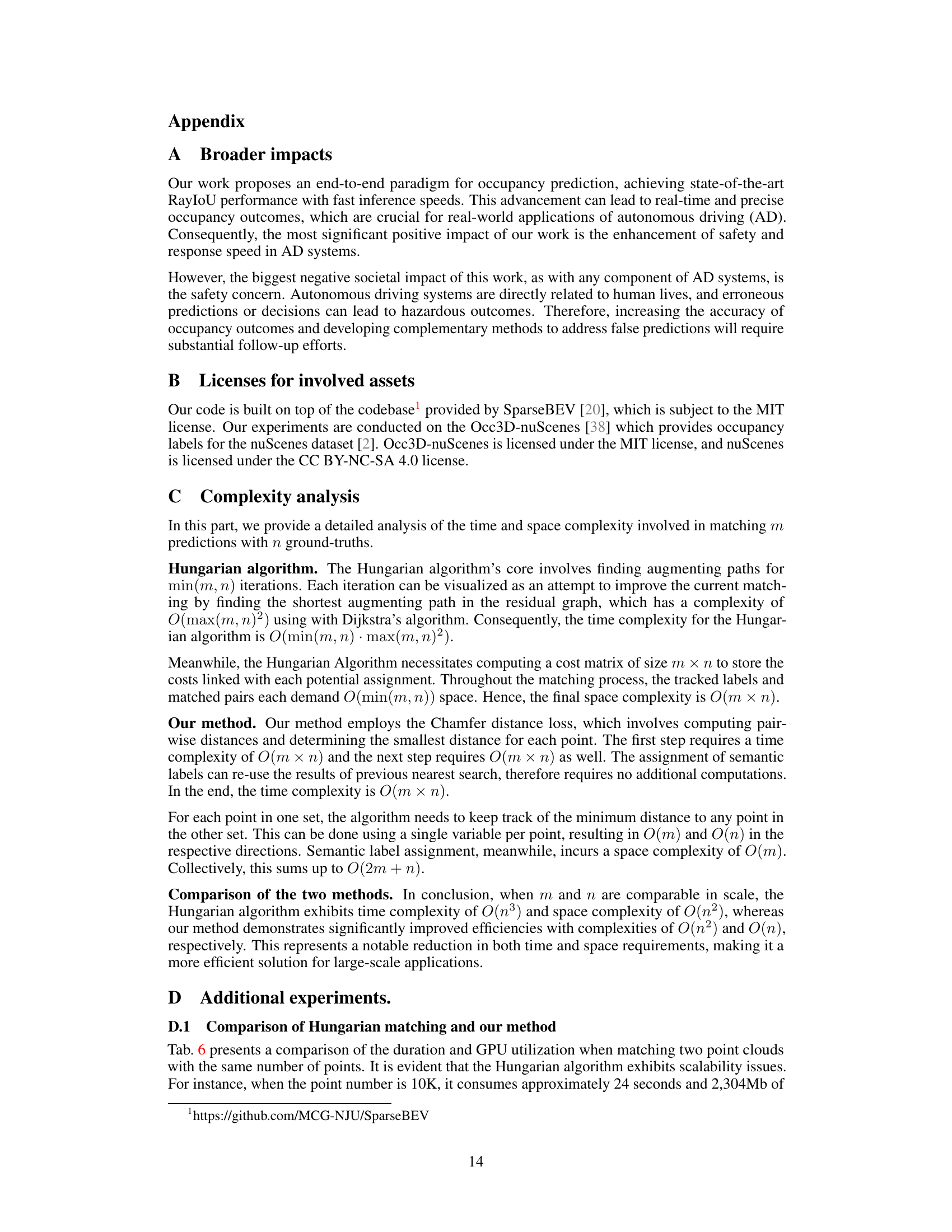

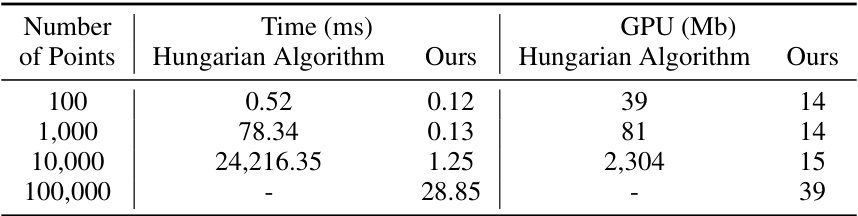

This table compares the performance of the Hungarian algorithm and the proposed label assignment method in terms of time and GPU memory consumption for matching point clouds of different sizes (100, 1000, 10000, and 100000 points). The results show that the proposed method is significantly faster and more memory-efficient, especially for larger point clouds.

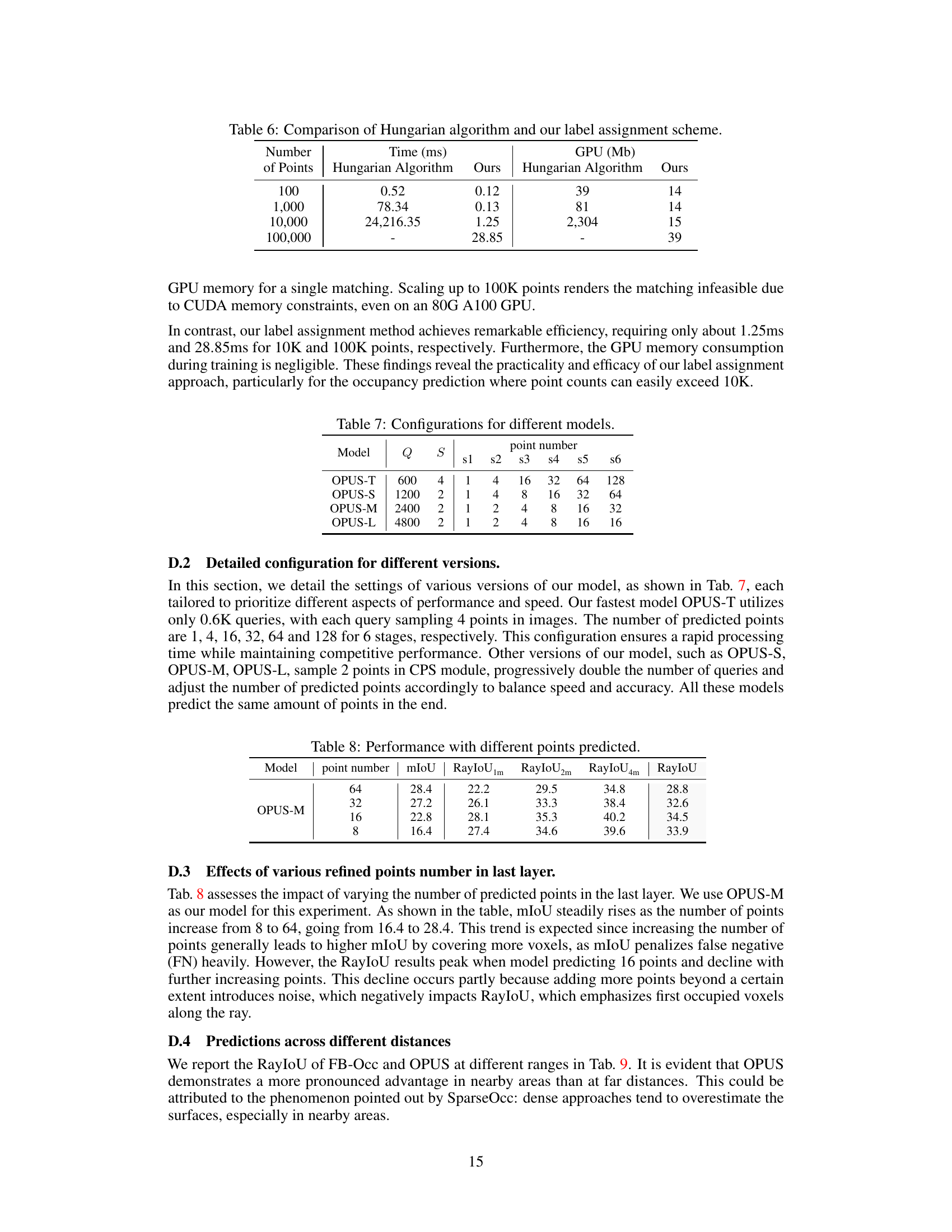

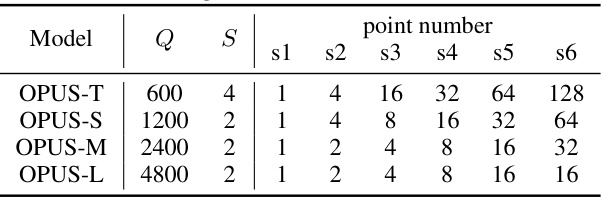

This table presents the hyperparameters used for training four different models of the OPUS architecture. Each row represents a different model variant (OPUS-T, OPUS-S, OPUS-M, OPUS-L), distinguished by the number of queries (Q) and the number of points sampled from each query (S) at different decoder layers. The columns ‘s1’ through ‘s6’ represent the number of points predicted at each of the six decoder layers. This design allows for coarse-to-fine learning in the occupancy prediction task, with varying computational demands and performance trade-offs.

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the number of points predicted in the last layer of the OPUS model. It shows how varying the number of points (8, 16, 32, 64) affects the model’s performance, measured by mIoU and RayIoU at different distance thresholds (1m, 2m, 4m). The results reveal a trade-off between accuracy (mIoU) and speed (RayIoU), with an optimal point number depending on the desired balance.

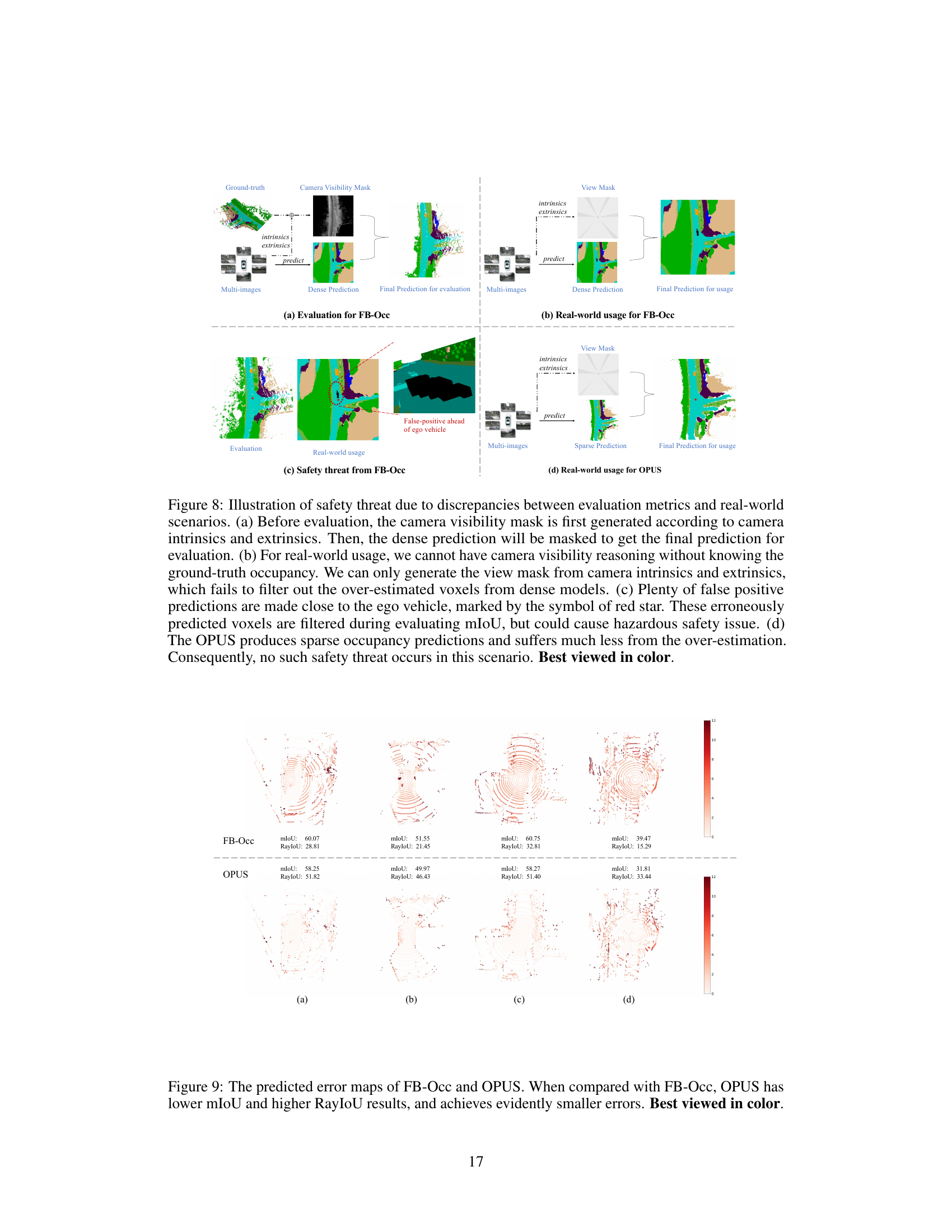

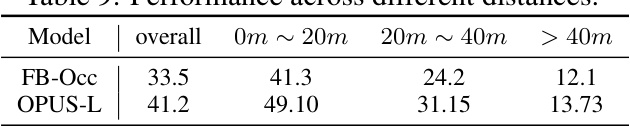

This table presents a comparison of the performance of FB-Occ and OPUS-L across different distance ranges. The overall RayIoU is shown, along with the RayIoU for distances 0-20 meters, 20-40 meters, and greater than 40 meters. The results indicate that OPUS-L significantly outperforms FB-Occ across all distance ranges, particularly in close proximity to the sensor.

Full paper#