↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), while powerful, often use standard activation functions unsuitable for graph data’s unique characteristics. This leads to suboptimal performance across diverse graph tasks and datasets. Existing attempts at graph-specific functions have limitations in flexibility or differentiability.

This paper introduces DIGRAF, a novel activation function that overcomes these limitations. DIGRAF uses Continuous Piecewise-Affine Based (CPAB) transformations, dynamically learning its parameters via a secondary GNN. Experiments show DIGRAF consistently outperforms traditional activation functions on diverse tasks and datasets, highlighting its potential for improving GNN performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces DIGRAF, a novel and effective activation function for Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). It addresses limitations of existing activation functions by being graph-adaptive and flexible, consistently improving GNN performance across diverse tasks and datasets. This opens new avenues for GNN research and development, impacting various applications that leverage graph data.

Visual Insights#

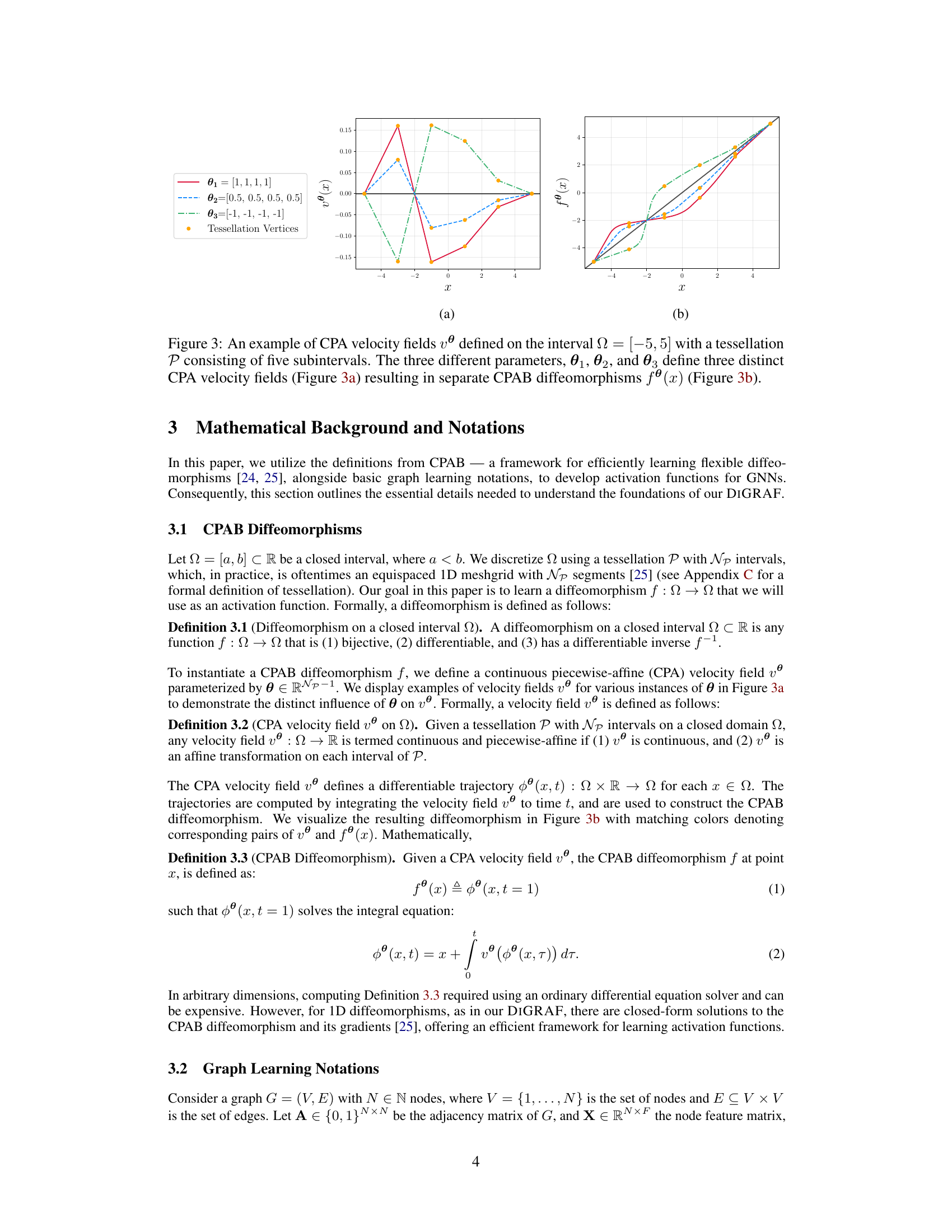

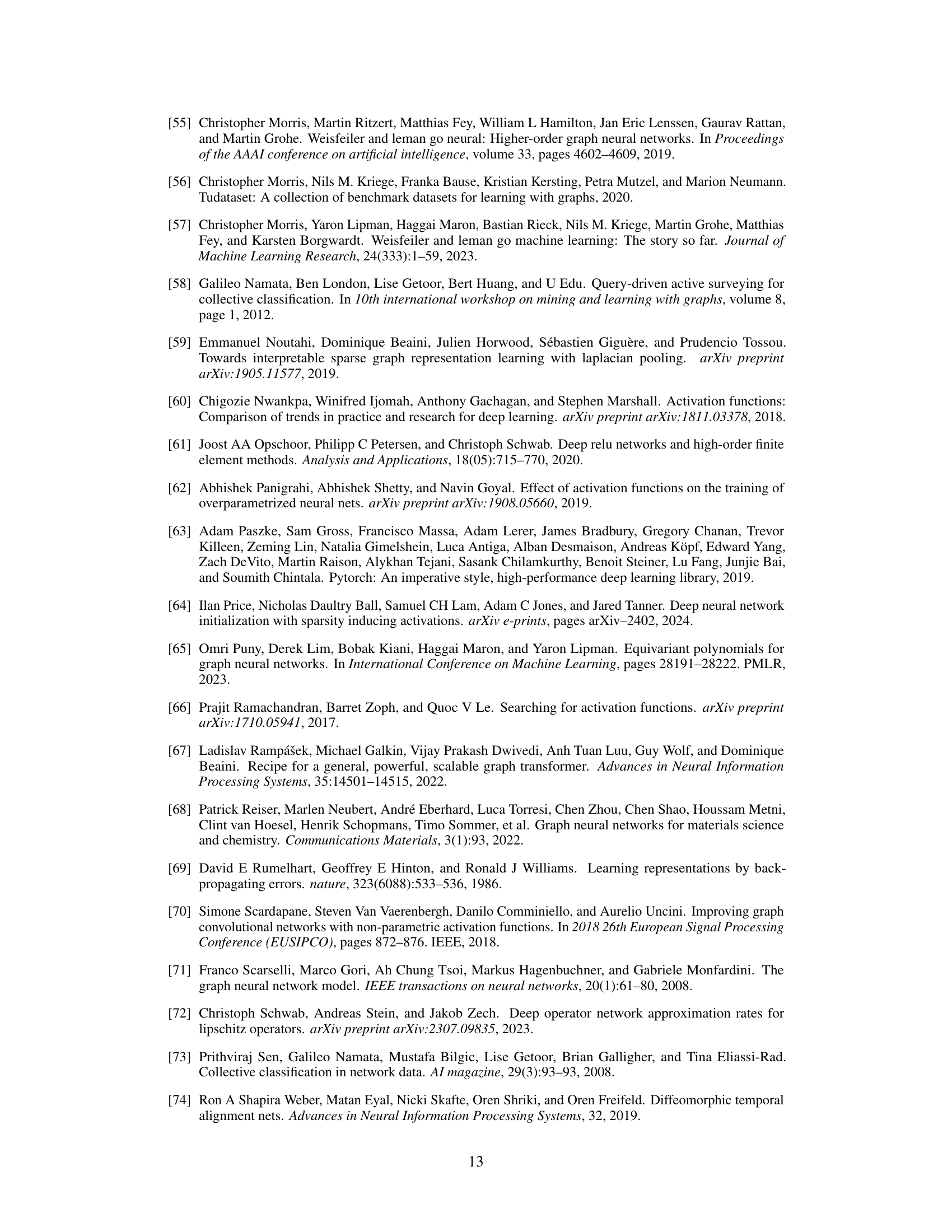

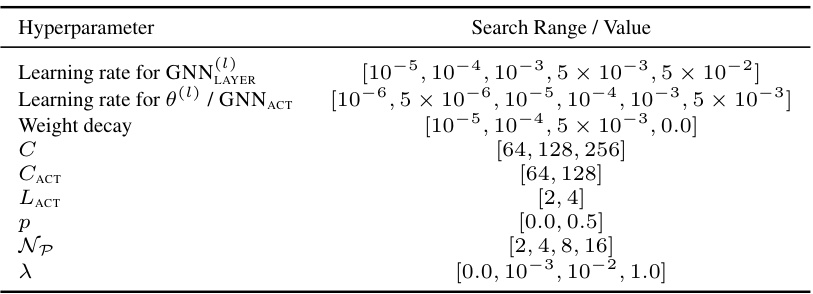

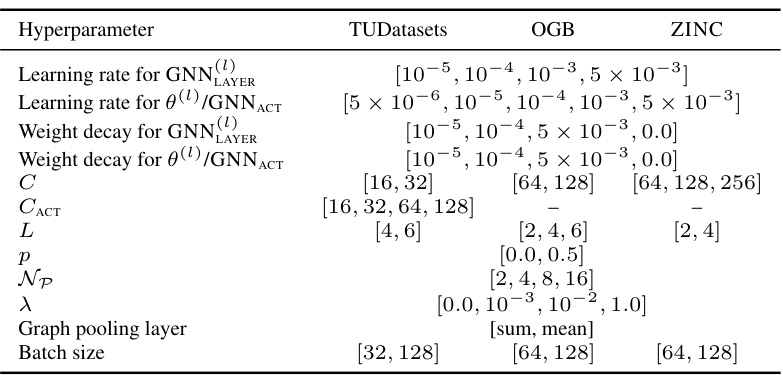

The figure illustrates the architecture of DIGRAF, a novel activation function for graph neural networks. It shows how node features and the adjacency matrix are processed through a GNN layer, then fed into the DIGRAF activation function. DIGRAF uniquely uses a second GNN (GNNACT) to learn graph-adaptive parameters (θ(l)) for the activation function, allowing it to dynamically adapt to different graph structures. These parameters are used in a transformation (T(l)) applied to the intermediate node features to produce the final activated node features.

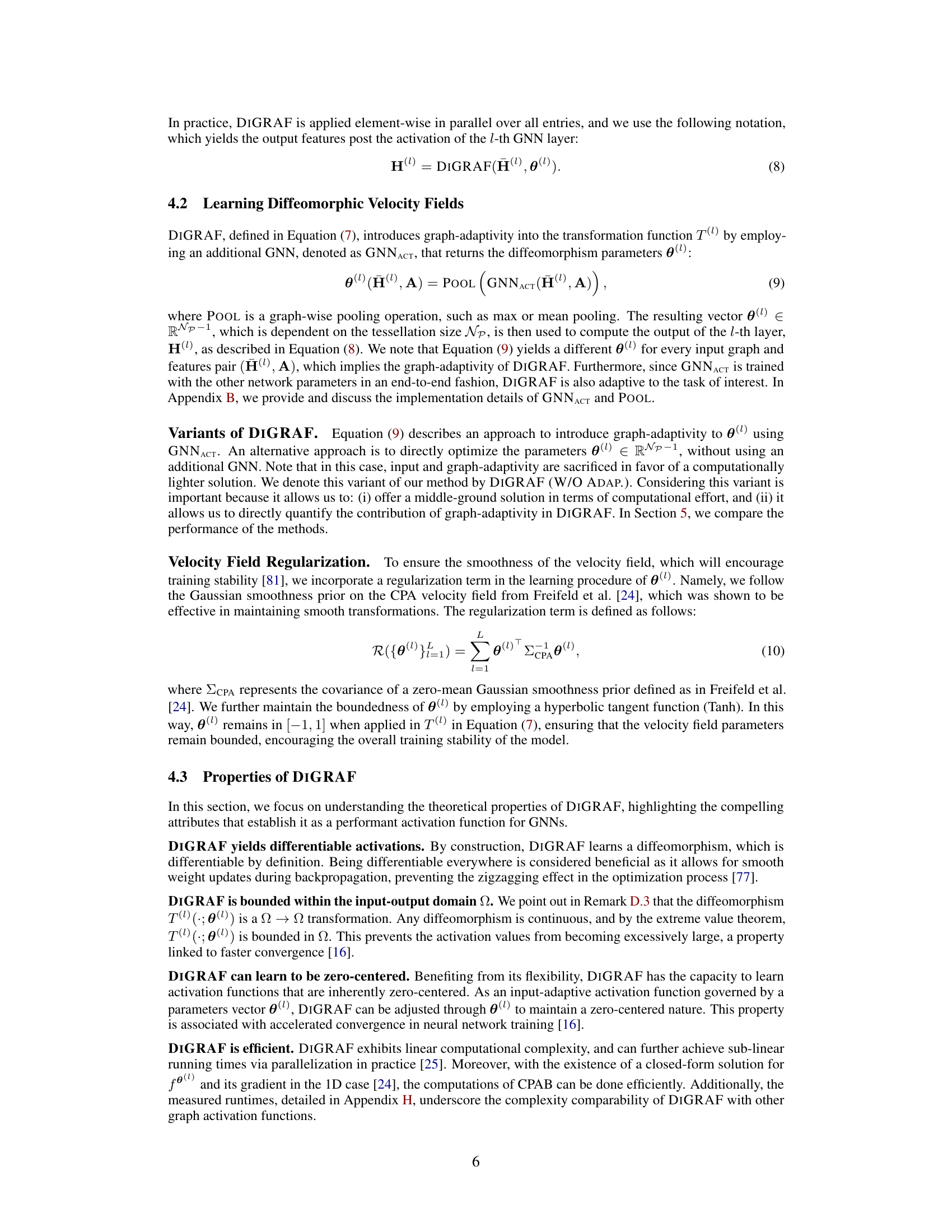

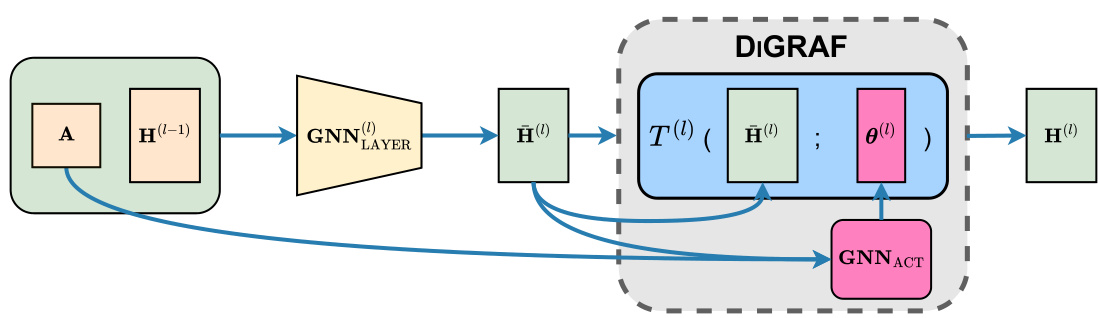

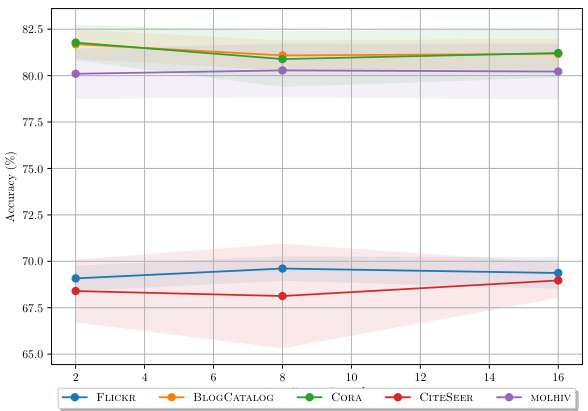

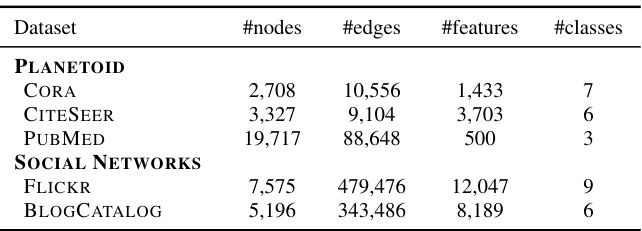

This table presents the results of node classification experiments on five different datasets using various activation functions. The goal is to compare the performance of DIGRAF, a novel graph-adaptive activation function, against several baseline activation functions, including standard activation functions (ReLU, Tanh, Sigmoid, etc.), learnable activation functions (PReLU, Maxout, Swish), and existing graph-specific activation functions (Max, Median, GReLU). The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method on each dataset. The top three performing methods for each dataset are highlighted.

In-depth insights#

DIGRAF’s Design#

DIGRAF’s design is a novel approach to graph activation functions within Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). It leverages Continuous Piecewise-Affine Based (CPAB) transformations, a powerful framework for learning flexible diffeomorphisms, to create a highly adaptable activation function. The key innovation is the incorporation of an additional GNN (GNNACT) to learn graph-adaptive parameters for the CPAB transformation, making the activation function dynamically adjust to the specific characteristics of each input graph. This contrasts sharply with traditional activation functions which have fixed forms. The resulting function, DIGRAF, is designed to be permutation equivariant, ensuring its behavior is consistent regardless of node ordering, a crucial property for GNNs. Differentiability, boundedness, and computational efficiency are further desirable properties incorporated into DIGRAF’s design, ensuring training stability and performance.

CPAB in GNNs#

The application of Continuous Piecewise-Affine Based (CPAB) transformations within Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) presents a novel approach to designing activation functions. CPAB’s inherent properties, such as bijectivity, differentiability, and invertibility, make it well-suited for this task, offering potential advantages over traditional activation functions. By incorporating a GNN to learn graph-adaptive parameters for the CPAB transformation, the resulting activation function, DIGRAF, dynamically adjusts to the unique structural features of each graph, potentially improving performance and generalization. This graph-adaptive mechanism is a key innovation, allowing the activation function to leverage the specific characteristics of the input data, rather than relying on a fixed, pre-defined function. The flexibility of CPAB also enables the approximation of a wide range of activation functions, offering a significant advantage in terms of adaptability. However, further investigation is needed to fully explore the trade-offs between the improved expressiveness and computational complexity introduced by this approach. Further research should focus on evaluating DIGRAF’s scalability and performance across diverse GNN architectures and datasets to fully understand its potential and limitations.

DIGRAF’s Benefits#

DIGRAF offers several key benefits stemming from its unique design. Its graph-adaptivity, achieved through a learned diffeomorphism parameterized by a graph-specific GNN, allows it to capture intricate graph structural information, leading to improved performance across diverse graph tasks. This adaptivity distinguishes DIGRAF from traditional activation functions that lack this crucial feature. Further, DIGRAF’s foundation in diffeomorphic transformations provides inherent desirable properties for activation functions: differentiability, boundedness, and computational efficiency. These properties contribute to improved training stability and faster convergence during model training. The flexibility of the CPAB framework enables DIGRAF to effectively learn and approximate various activation function behaviors, significantly outperforming activation functions with fixed blueprints. Finally, the consistent superior performance across various datasets and tasks, shown empirically, strongly indicates DIGRAF’s effectiveness as a versatile and robust activation function for GNNs.

DIGRAF’s Limits#

DIGRAF, while demonstrating strong performance, is not without limitations. Its reliance on CPAB transformations, though flexible, might restrict its ability to model activation functions outside the diffeomorphism family. This could limit its applicability to certain GNN architectures or tasks where non-diffeomorphic activation functions are preferred. The need for an additional GNN (GNNACT) to learn graph-adaptive parameters adds computational overhead, potentially offsetting performance gains, especially with large graphs. The effects of hyperparameters, notably the tessellation size and regularization strength, require careful tuning and might not generalize seamlessly across diverse datasets. Furthermore, the paper doesn’t address the extent to which DIGRAF’s performance advantage stems from its inherent properties versus the end-to-end training approach; disentangling these factors would be crucial for a complete understanding. Finally, future research should investigate its robustness against noisy or incomplete graph data, a common challenge in real-world applications.

Future of DIGRAF#

The future of DIGRAF, a novel graph-adaptive activation function, appears promising. Extending DIGRAF to handle dynamic graphs is a key area for future work, as many real-world graph datasets evolve over time. This could involve incorporating temporal information into the GNNACT module, allowing for activation functions that adapt not only to graph structure but also to changes in that structure. Investigating different diffeomorphic transformation techniques beyond CPAB could lead to even greater flexibility and expressiveness, potentially enabling DIGRAF to model more complex graph phenomena. Exploring the applications of DIGRAF in other graph-based tasks beyond those tested in the paper is another area of great potential. DIGRAF’s superior performance on various benchmarks suggest it could be beneficial in other domains like molecular design, recommendation systems, and drug discovery. Finally, developing a more efficient implementation of DIGRAF would allow for its application to larger and more complex graphs, a crucial requirement for wide-scale adoption. The current approach’s linear complexity represents a good starting point, but optimization work to improve speed and scalability could significantly broaden DIGRAF’s impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

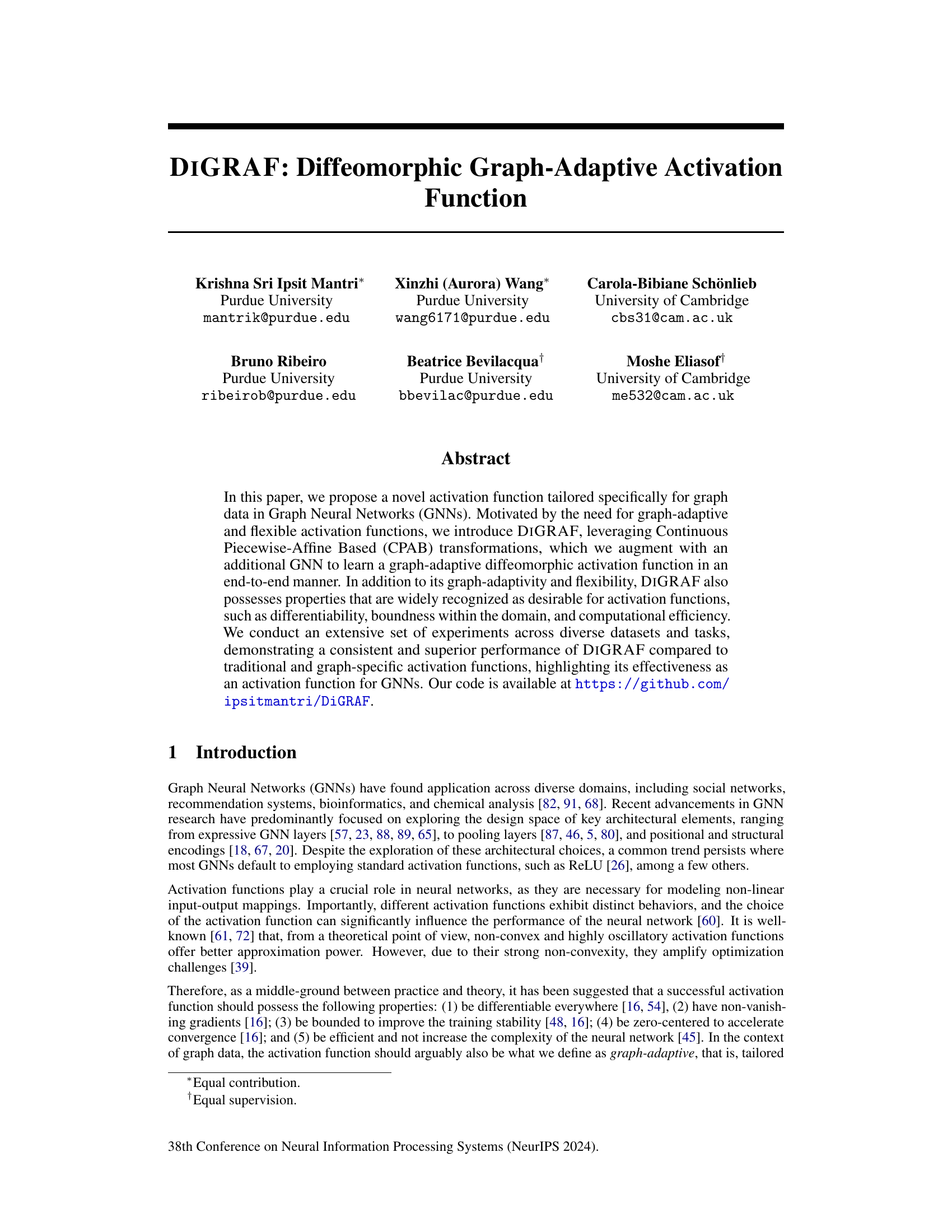

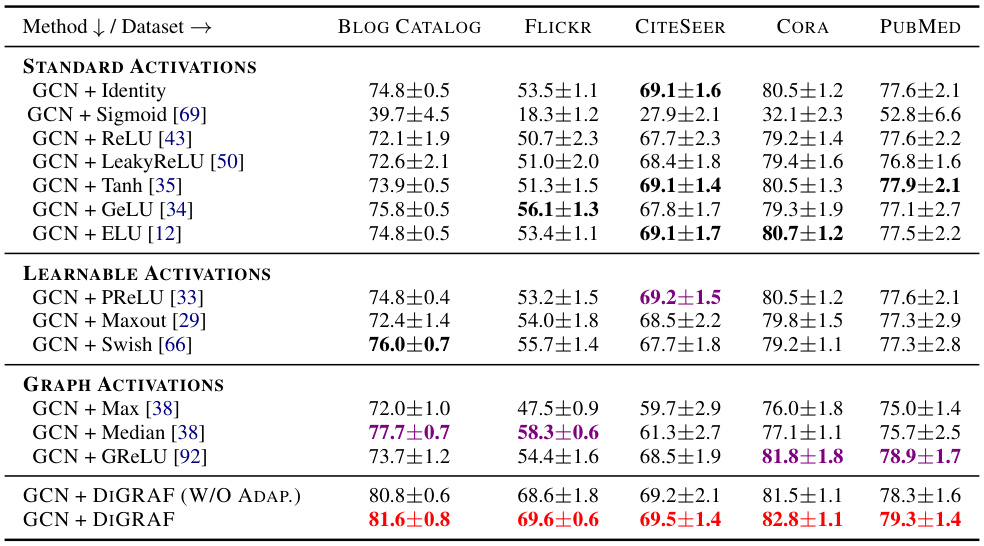

This figure demonstrates the ability of Continuous Piecewise-Affine Based (CPAB) transformations and Piecewise ReLU to approximate traditional activation functions like ELU and Tanh. It showcases the flexibility of CPAB, which can model various activation functions by adjusting the number of segments (K). The plots show how well CPAB and Piecewise ReLU, with different numbers of segments, approximate the shapes of the ELU and Tanh activation functions. It highlights the benefit of using CPAB to model activation functions.

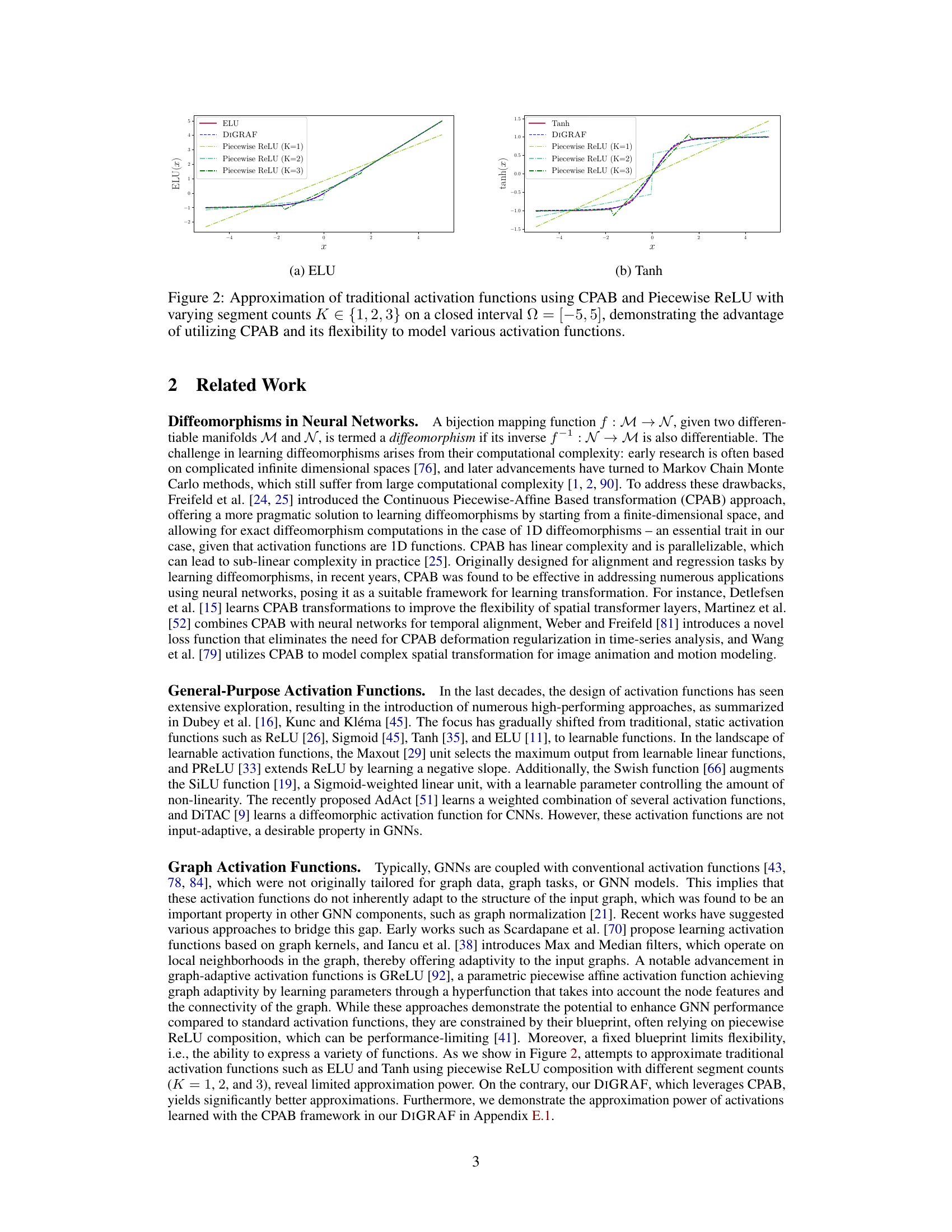

This figure shows examples of how different CPA velocity fields are generated using different parameters (θ1, θ2, θ3) and how these fields lead to different CPAB diffeomorphisms. The left panel (a) displays the velocity fields, demonstrating the piecewise-affine nature, and showing how different parameterizations yield different velocity profiles. The right panel (b) shows the resulting diffeomorphisms, illustrating the effect of the velocity fields on the transformation of the input space. Each colored curve in (b) corresponds to the velocity field with the same color in (a), highlighting the relationship between the velocity field and the resulting diffeomorphic transformation.

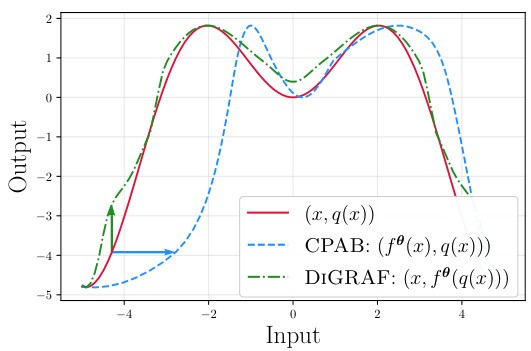

This figure illustrates the conceptual difference between CPAB and DIGRAF transformations. CPAB transforms the input function horizontally, while DIGRAF transforms it vertically. This highlights DIGRAF’s unique application of CPAB, adapting it to function as a graph activation function by modifying the output rather than the input. Both methods use CPAB, but their applications and the resulting effects differ.

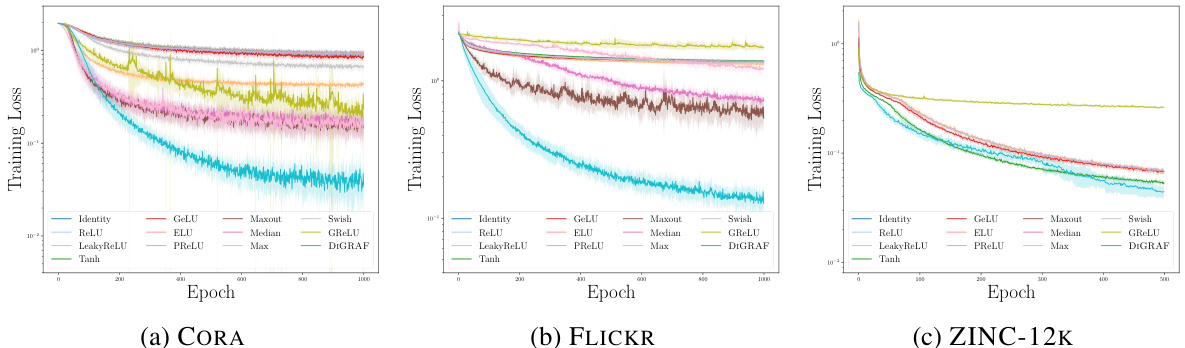

This figure shows the training loss curves for various activation functions, including DIGRAF, across three different datasets: CORA, FLICKR, and ZINC-12K. The plots demonstrate that DIGRAF generally converges faster than other activation functions, indicating improved training stability and efficiency.

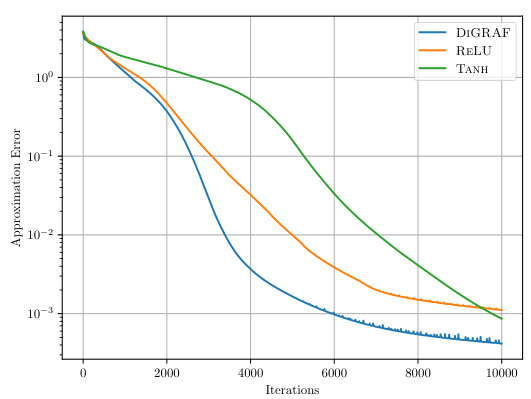

The figure shows the approximation error of the Peaks function using three different activation functions: ReLU, Tanh, and DIGRAF. The x-axis represents the number of iterations during the training process of a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) designed to approximate the Peaks function. The y-axis (on a logarithmic scale) shows the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the approximated function and the actual Peaks function. The plot visually demonstrates the superior approximation power of DIGRAF compared to both ReLU and Tanh, achieving a significantly lower MSE after the same number of training iterations.

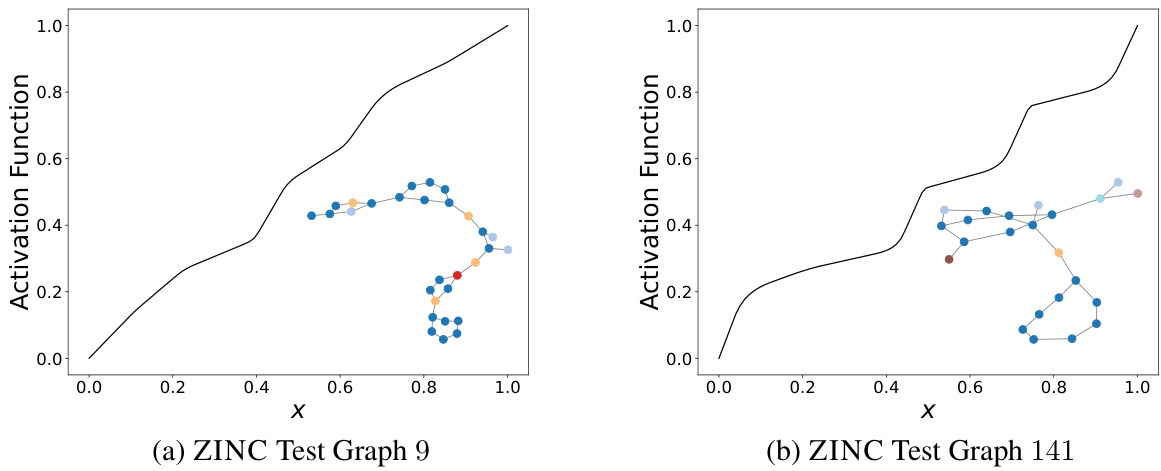

This figure shows the activation function learned by DIGRAF for two different graphs from the ZINC dataset after the last GNN layer. Each node in the graphs is represented by a different color, indicating its feature. The plot shows that DIGRAF produces different activation functions for different graphs, highlighting its adaptivity to different graph structures.

The figure shows the training loss curves for various activation functions (DIGRAF and baselines) across three different datasets (CORA, Flickr, and ZINC-12k). The plots demonstrate that DIGRAF converges faster than most baseline activation functions on all three datasets, indicating improved training efficiency.

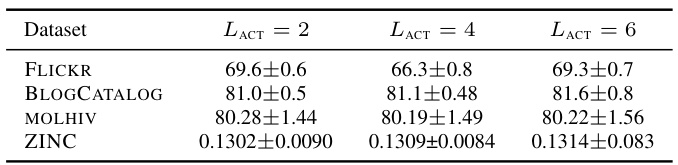

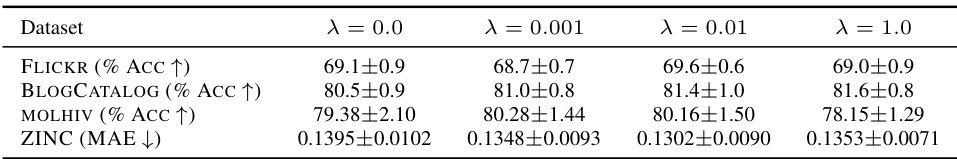

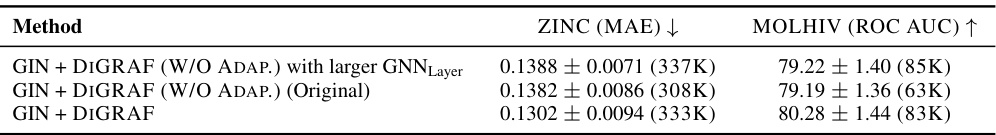

More on tables

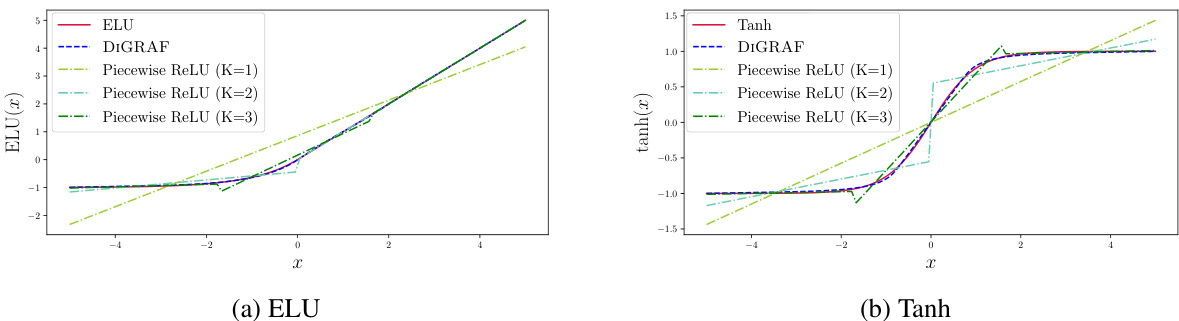

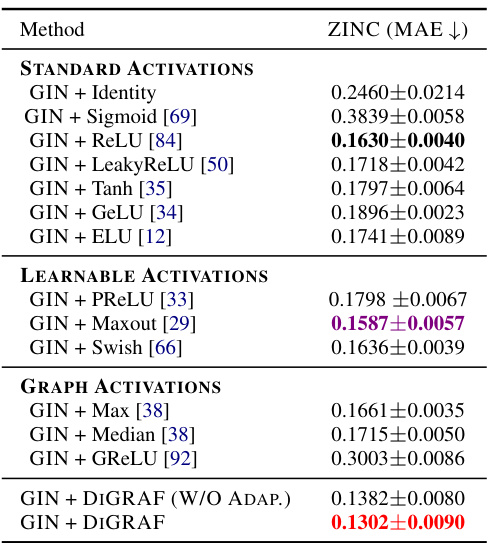

This table presents the results of a regression task on the ZINC-12K dataset, focusing on predicting the constrained solubility of molecules. It compares various activation functions within a Graph Neural Network (GNN) architecture, specifically using a GIN backbone. The table highlights the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) achieved by each activation function, indicating their performance in predicting molecular solubility. The best three performing methods are highlighted.

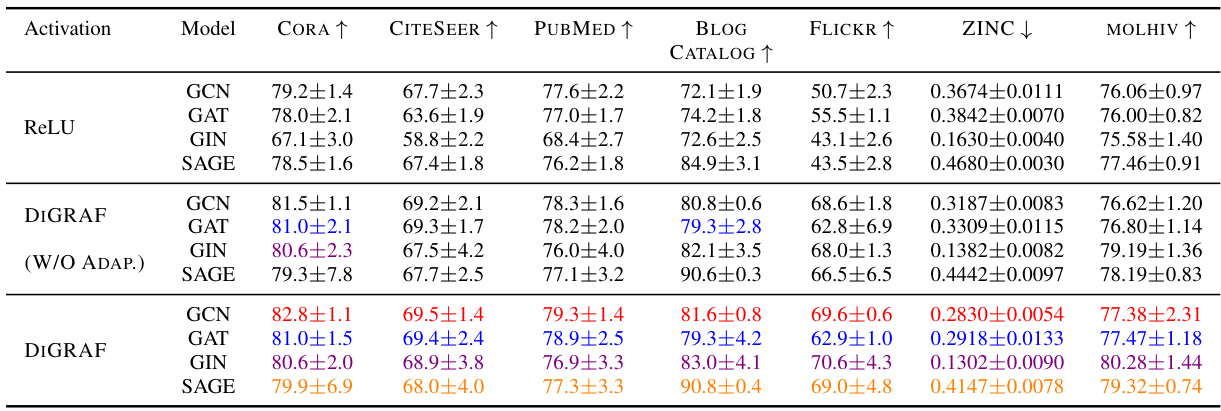

This table compares the performance of DIGRAF against various baseline activation functions on four datasets from the Open Graph Benchmark (OGB). The baselines include standard activation functions (Identity, Sigmoid, ReLU, LeakyReLU, Tanh, GeLU, ELU), learnable activation functions (PReLU, Maxout, Swish), and graph-specific activation functions (Max, Median, GReLU). The table shows that DIGRAF consistently outperforms the baselines across different evaluation metrics (RMSE and ROC-AUC) for various tasks, highlighting its effectiveness as a graph-adaptive activation function.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments on five different datasets (BLOGCATALOG, FLICKR, CITESEER, CORA, and PUBMED). It compares the performance of DIGRAF against various baselines, categorized as Standard Activations, Learnable Activations, and Graph Activations. The top three performing methods for each dataset are highlighted. The accuracy is measured as a percentage and higher values indicate better performance.

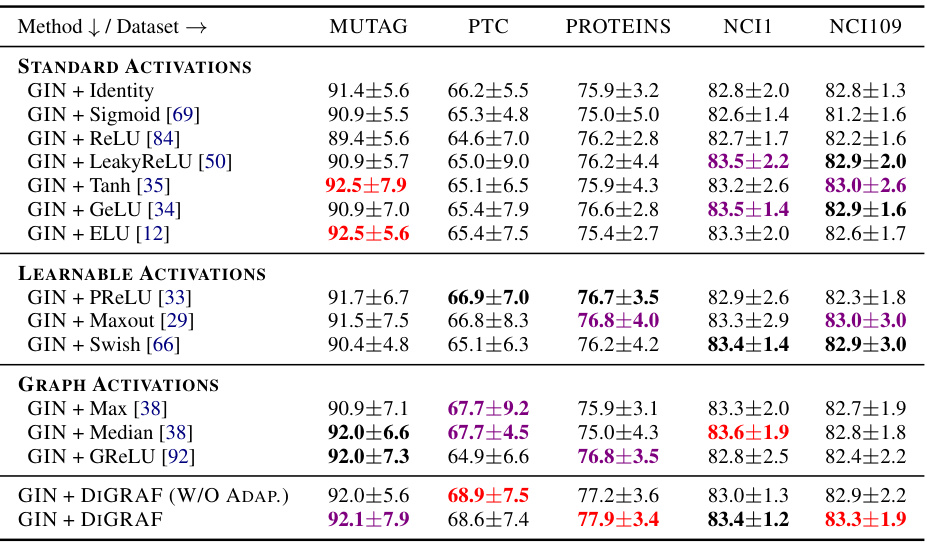

This table presents the results of graph classification experiments on five datasets from the TUDataset collection. The table compares the performance of DIGRAF against various baseline activation functions, including standard activation functions (ReLU, Tanh, Sigmoid, etc.), learnable activation functions (PReLU, Maxout, Swish), and other graph-adaptive activation functions (Max, Median, GReLU). The accuracy is reported as a percentage, and the top three performing methods for each dataset are highlighted. The table shows that DIGRAF consistently achieves high accuracy across the different datasets and often outperforms the other methods.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments on five different datasets (BLOGCATALOG, FLICKR, CITESEER, CORA, and PUBMED). The experiments compare the performance of DIGRAF against various baseline activation functions, categorized as standard activation functions (e.g., ReLU, Tanh, Sigmoid), learnable activation functions (e.g., PReLU, Maxout, Swish), and graph-specific activation functions (e.g., Max, Median, GReLU). The table shows the accuracy achieved by each activation function on each dataset. The top three performing methods for each dataset are highlighted.

This table compares the performance of DIGRAF against different ReLU variants with varying parameter budgets. It shows that increasing the number of parameters in ReLU does not significantly improve performance. DIGRAF consistently outperforms all ReLU variants, highlighting its efficiency and effectiveness even with a relatively smaller number of parameters.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments conducted on five different datasets using various activation functions. The results show the accuracy of each activation function on the datasets, allowing for a comparison of performance between traditional activation functions, learnable activation functions, graph-specific activation functions, and DIGRAF (both with and without adaptivity). The top three methods for each dataset are highlighted.

This table presents a comparison of node classification accuracy achieved using different activation functions on various benchmark datasets. The activation functions are categorized into standard, learnable, and graph-specific activations, with DIGRAF being the proposed method. The table shows that DIGRAF consistently achieves state-of-the-art performance across all the datasets, highlighting its effectiveness. The top three performing methods are clearly marked for each dataset.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments on five different datasets using various activation functions. The performance of DIGRAF is compared against baseline activation functions categorized as standard, learnable, and graph-specific. The table shows the accuracy achieved by each activation function on each dataset, highlighting DIGRAF’s superior performance.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments on several datasets using different activation functions. The performance of DIGRAF is compared against various baselines including standard activation functions (ReLU, Tanh, Sigmoid, etc.), learnable activation functions (PReLU, Maxout, Swish), and other graph-specific activation functions (Max, Median, GReLU). The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method on each dataset and highlights the top three performing methods.

This table compares the performance of DIGRAF against various baselines on five node classification datasets. The baselines include standard activation functions (Identity, Sigmoid, ReLU, LeakyReLU, Tanh, GeLU, ELU), learnable activation functions (PReLU, Maxout, Swish), and graph-specific activation functions (Max, Median, GReLU). The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method on each dataset, highlighting DIGRAF’s superior performance.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments on five different datasets using various activation functions, including DIGRAF and several baselines. The accuracy is measured and the top three performing methods for each dataset are highlighted. The baselines encompass standard activation functions, learnable activation functions, and graph-specific activation functions. This table demonstrates the superior performance of DIGRAF compared to the baselines across multiple datasets.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments on five datasets using different activation functions. The table compares the performance of DIGRAF against several baseline methods, including standard activation functions (Identity, Sigmoid, ReLU, LeakyReLU, Tanh, GeLU, ELU), learnable activation functions (PReLU, Maxout, Swish), and graph-specific activation functions (Max, Median, GReLU). The top three performing methods for each dataset are highlighted. It demonstrates DIGRAF’s superior performance and its consistent improvement across various graph datasets and tasks.

This table compares the performance of DIGRAF against various baseline activation functions (standard, learnable, graph-specific) on five different node classification datasets (BLOGCATALOG, FLICKR, CITESEER, CORA, PUBMED). The accuracy is reported as a percentage, with the top three methods for each dataset highlighted. This demonstrates DIGRAF’s performance advantage.

This table presents the results of a regression task on the ZINC-12K dataset, focusing on predicting the constrained solubility of molecules. It compares various activation functions within a Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) architecture, all under a 500K parameter budget. The table highlights the mean absolute error (MAE) achieved by each activation function, indicating the accuracy of the solubility prediction. The top three performing activation functions are identified as ‘First,’ ‘Second,’ and ‘Third.’

Full paper#