↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The problem of inductive inference—whether one can make only finitely many errors when inferring a hypothesis from an infinite sequence of observations—has puzzled philosophers and scientists for centuries. Existing theories only offered sufficient conditions, such as a countable hypothesis class. This limitation restricted applications and theoretical understanding.

This paper provides a complete solution. By establishing a novel link to online learning theory and introducing a non-uniform online learning framework, it proves that inductive inference is possible if and only if the hypothesis class is a countable union of online learnable classes. This holds true even when the observations are adaptively chosen (not independently and identically distributed) or in agnostic settings (where the true hypothesis isn’t in the class). The results offer a precise characterization of inductive inference, going beyond previous sufficient conditions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it solves a long-standing philosophical problem: determining when inductive inference is possible. It bridges inductive inference and online learning theory, offering novel theoretical insights and a new learning framework. This opens new research avenues in both fields and impacts machine learning algorithm design. Its findings are significant for understanding human reasoning and scientific discovery.

Visual Insights#

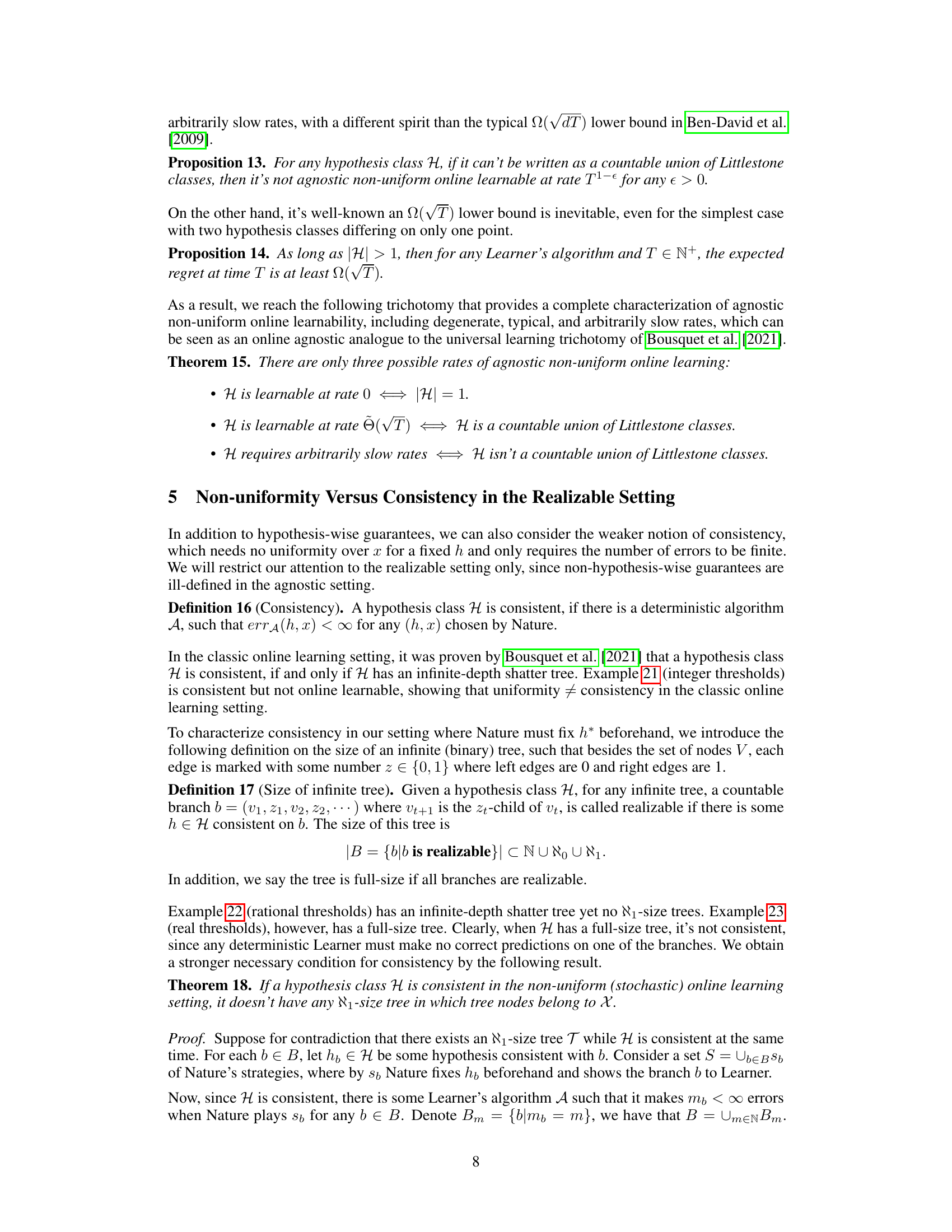

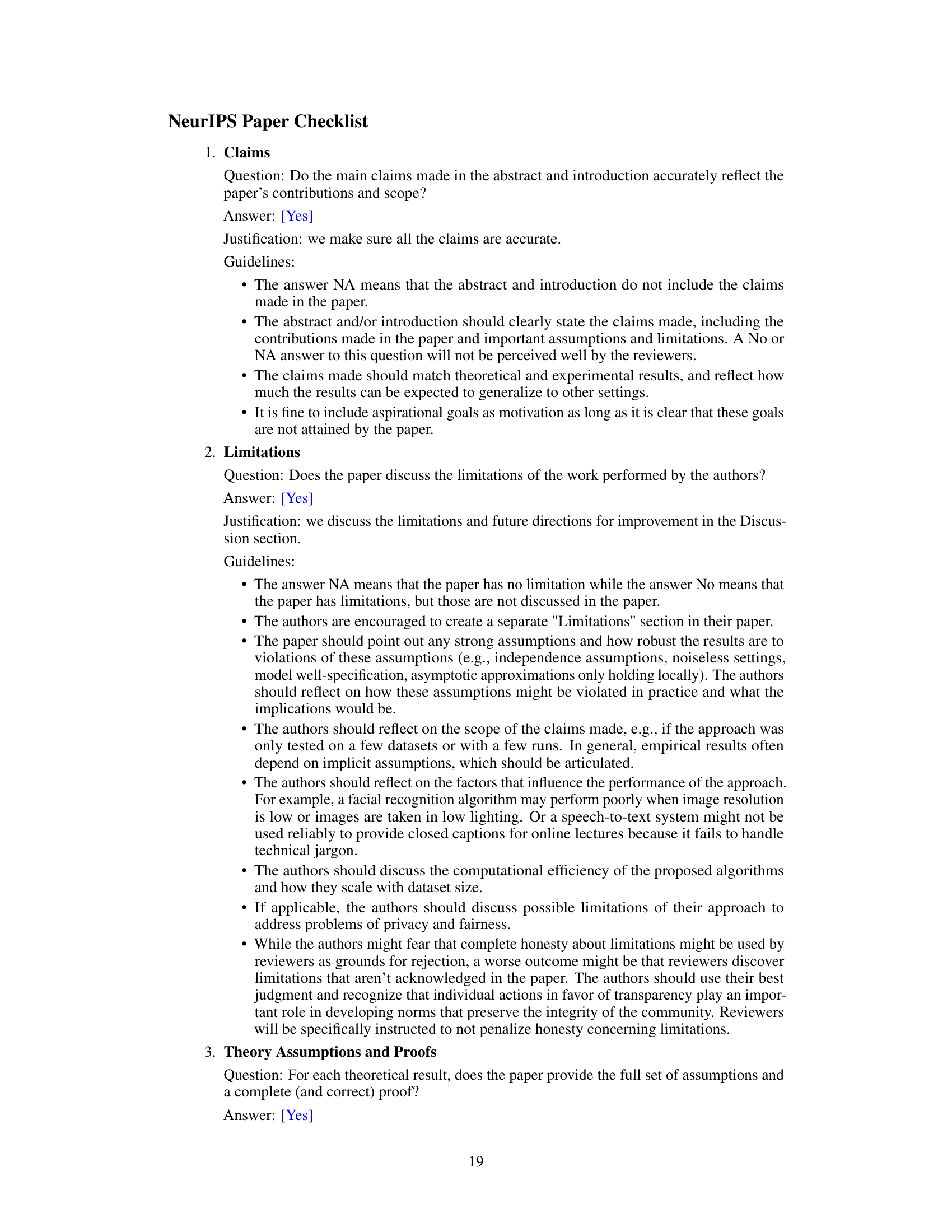

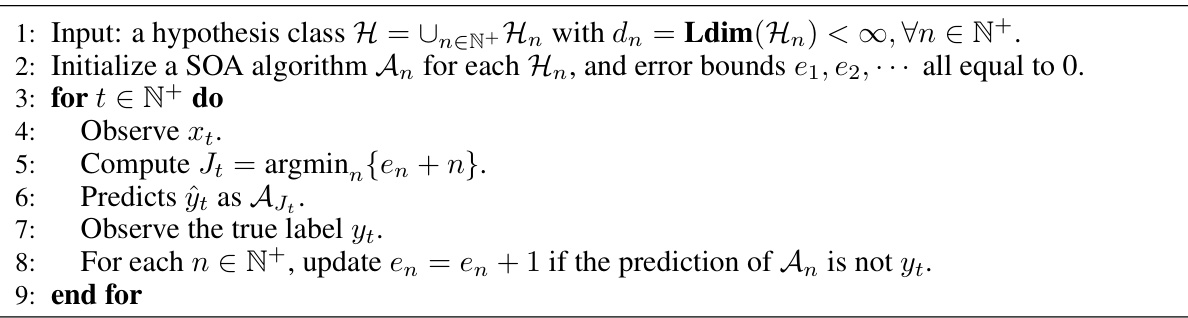

This figure illustrates the concept of V(i,j) nodes in an infinite tree. Each V(i,j) node represents a point in the tree, and the red paths indicate realizable branches, meaning branches for which there exists a hypothesis in the hypothesis class H that is consistent with all the labels along that branch.

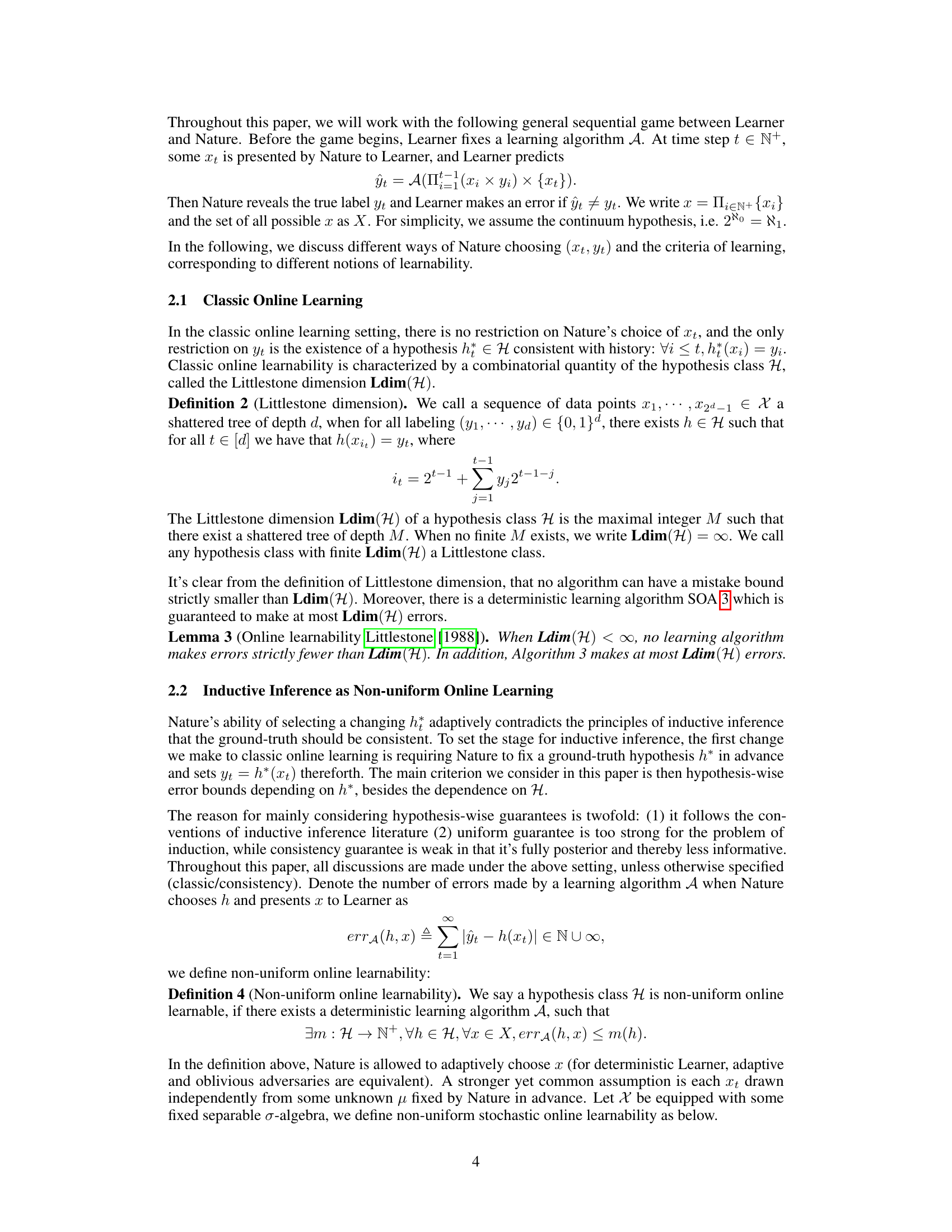

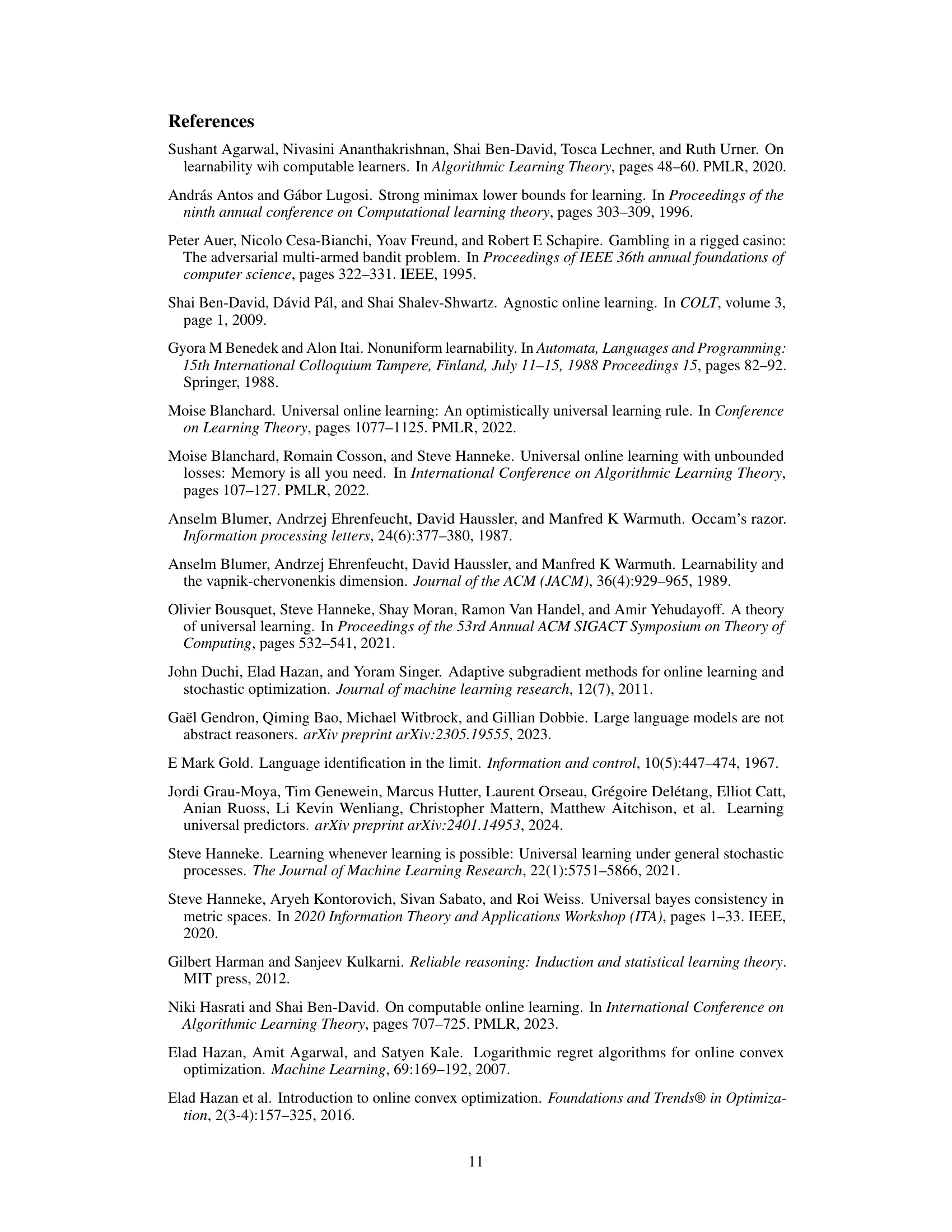

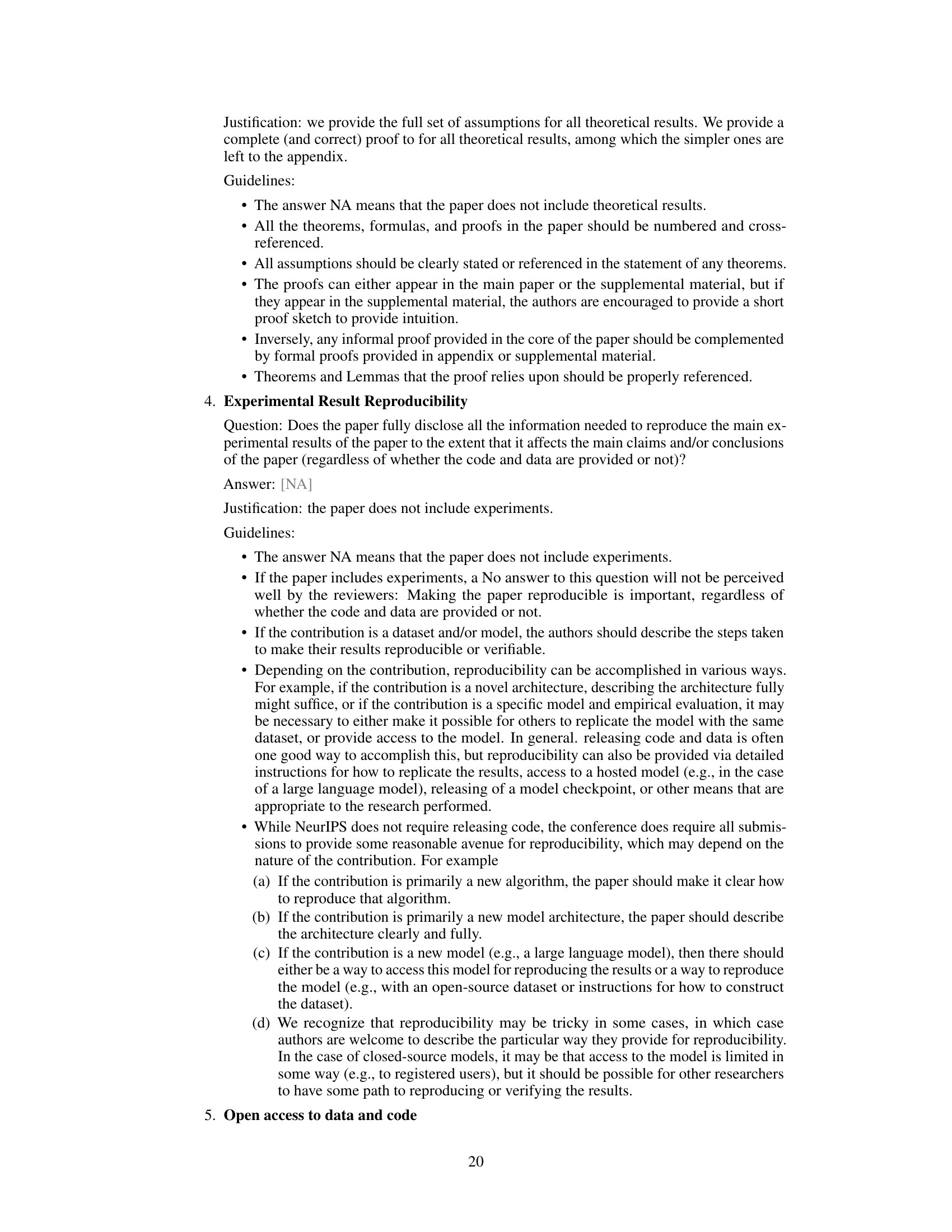

The table compares and contrasts classic online learning and non-uniform online learning (inductive inference). It highlights the key differences in the protocols followed by each learning paradigm. Classic online learning involves the learner predicting yt, Nature selecting a consistent hypothesis ht, and Nature revealing the true label ht(xt). The goal in classic online learning is to achieve a uniform error bound. In contrast, non-uniform online learning (inductive inference) differs in that Nature selects a ground-truth hypothesis h* before the learning process starts. Nature then presents an observation xt, the learner predicts yt, and Nature reveals the true label h*(xt). The goal here is to achieve an error bound that may depend on the chosen h*. This crucial difference underscores the distinction between the two learning frameworks and how their protocols cater to the specific goals of uniform versus non-uniform error bounds.

In-depth insights#

Inductive Inference#

Inductive inference, the process of moving from specific observations to general principles, is a cornerstone of scientific reasoning. Philosophically, its justification remains a challenge, as highlighted by Hume’s problem of induction. Mathematically, inductive inference is often formalized as a learner aiming to deduce a correct hypothesis from a class of possibilities, making at most a finite number of errors from an infinite stream of observations. Countability of the hypothesis class has historically been considered a sufficient condition for successful inductive inference. However, this paper presents a novel and tighter characterization, establishing a connection between inductive inference and online learning theory. It shows that inductive inference is possible if and only if the hypothesis class is representable as a countable union of online learnable classes, even allowing for uncountable class sizes and agnostic settings. This crucial finding significantly advances our understanding of the conditions required for successful inductive inference, broadening its applicability beyond previous limitations. The paper introduces a non-uniform online learning framework which is essential for bridging the gap between classic online learning and inductive inference, thereby providing a fresh perspective and potential avenues for future research.

Online Learning Link#

The “Online Learning Link” section likely explores the connection between inductive inference and online learning, revealing a powerful bridge between philosophical inquiry and machine learning theory. It probably demonstrates how the framework of online learning, particularly its ability to handle sequential data and adapt to new information, provides a rigorous mathematical structure to analyze and understand the challenges of inductive inference. This link likely involves formalizing the inductive inference problem within the online learning setting, defining relevant metrics (like regret) to measure learner performance, and proving theorems establishing necessary and sufficient conditions for successful inductive inference based on properties of the hypothesis class. The analysis might encompass both realizable and agnostic settings, showing how the theoretical guarantees of online learning provide valuable insights into the possibilities and limitations of learning from data. The discussion likely highlights the implications of this connection for both fields, suggesting new avenues of research at the intersection of philosophy, statistics, and machine learning. A key outcome could be a novel characterization of inductive inference, moving beyond previous results by providing more nuanced and complete conditions for learnability.

Non-uniform Learning#

Non-uniform learning offers a valuable perspective shift in machine learning. Instead of seeking uniform guarantees that apply equally across all instances, it focuses on hypothesis-specific bounds. This is especially relevant when dealing with complex scenarios where the difficulty of learning varies significantly depending on the underlying data generating process or true hypothesis. The flexibility to provide different performance guarantees for different hypotheses is a key strength, and models the inductive inference problem more realistically. The non-uniform approach enhances the ability to manage learning complexity and allows for more nuanced analysis, potentially leading to more efficient algorithms and a deeper understanding of learning dynamics.

Agnostic Setting#

In an agnostic setting for machine learning, the assumption that the true hypothesis is within the learner’s hypothesis class is relaxed. This contrasts with the realizable setting, where the learner’s hypothesis space contains the ground truth. The agnostic setting is more realistic, reflecting the uncertainty in real-world problems where the true hypothesis might be unknown or not even representable within the chosen model. This setting requires robustness and an ability to deal with uncertainty; rather than aiming for perfect accuracy, the learner seeks to minimize the difference between its predictions and the true outcome, which may not be perfectly captured by any hypothesis in the available class. Algorithms must therefore be designed to handle noisy or incomplete data and provide performance guarantees that hold regardless of the ground truth’s presence within the hypothesis space. Evaluating performance in this context often shifts from the number of errors to measures like regret, which considers the difference in performance between the learner and the best hypothesis in hindsight. This focus on generalization and robustness makes the agnostic setting crucial for understanding how machine learning performs in real-world applications.

Future Directions#

The ‘Future Directions’ section of this research paper would ideally delve into several key areas. Identifying sufficient conditions for consistency in inductive inference, beyond the established necessary condition, is paramount. The current work establishes a tight characterization for hypothesis-wise error bounds, but a more relaxed criterion of consistency, requiring only a finite number of errors without uniformity, needs further exploration. The theoretical findings suggest a possible connection between the notion of consistency and the existence of specific tree structures within the hypothesis class, warranting investigation. Another critical area for future exploration involves fully characterizing the relationship between different notions of learnability (uniform, non-uniform, and agnostic settings) and their implications for practical algorithms. Finally, bridging the gap between theoretical guarantees and computational feasibility is crucial. Specifically, exploring the application of these theoretical results within the context of computable learners and investigating practical bounds in light of constraints such as computational complexity and resource limitations will be valuable steps towards developing more practically applicable algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on tables

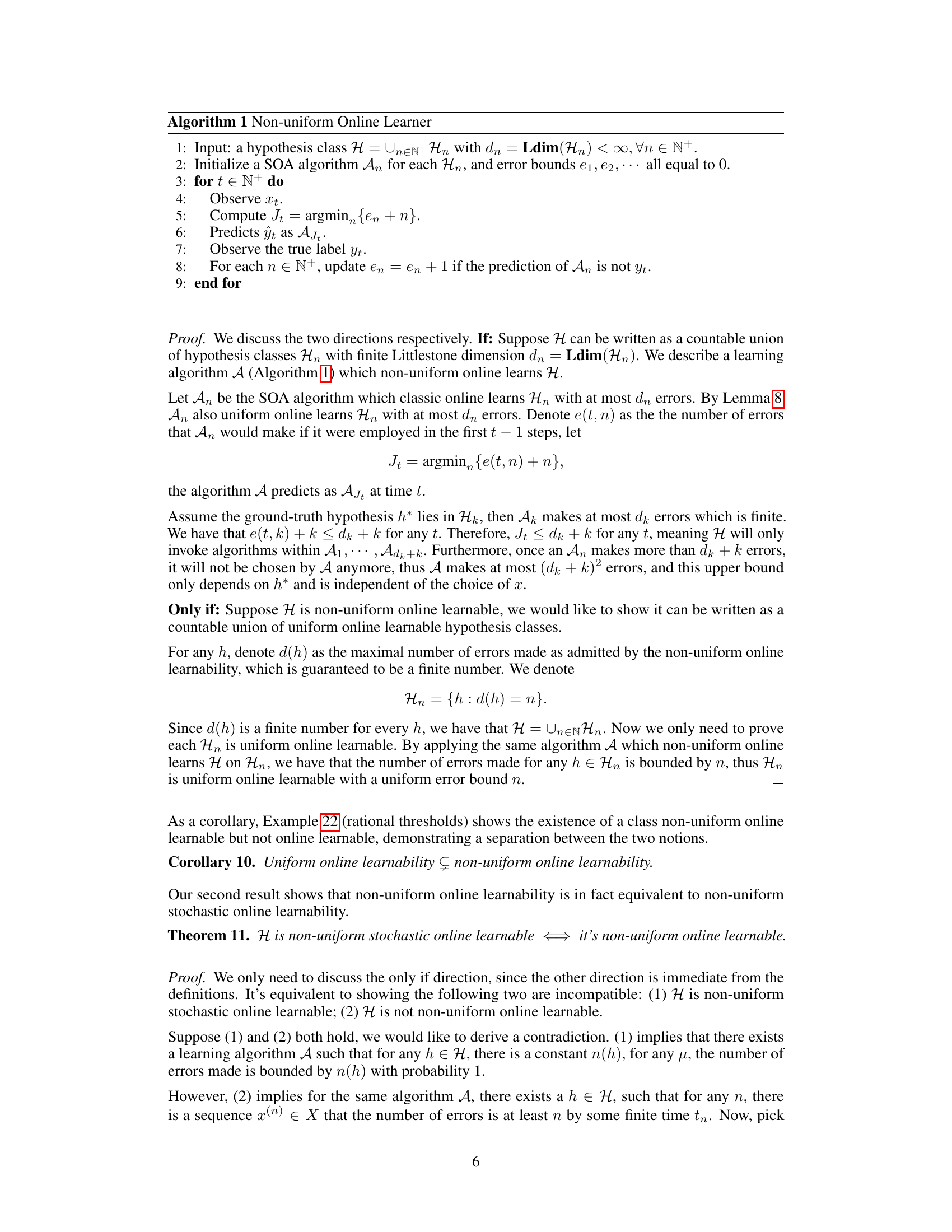

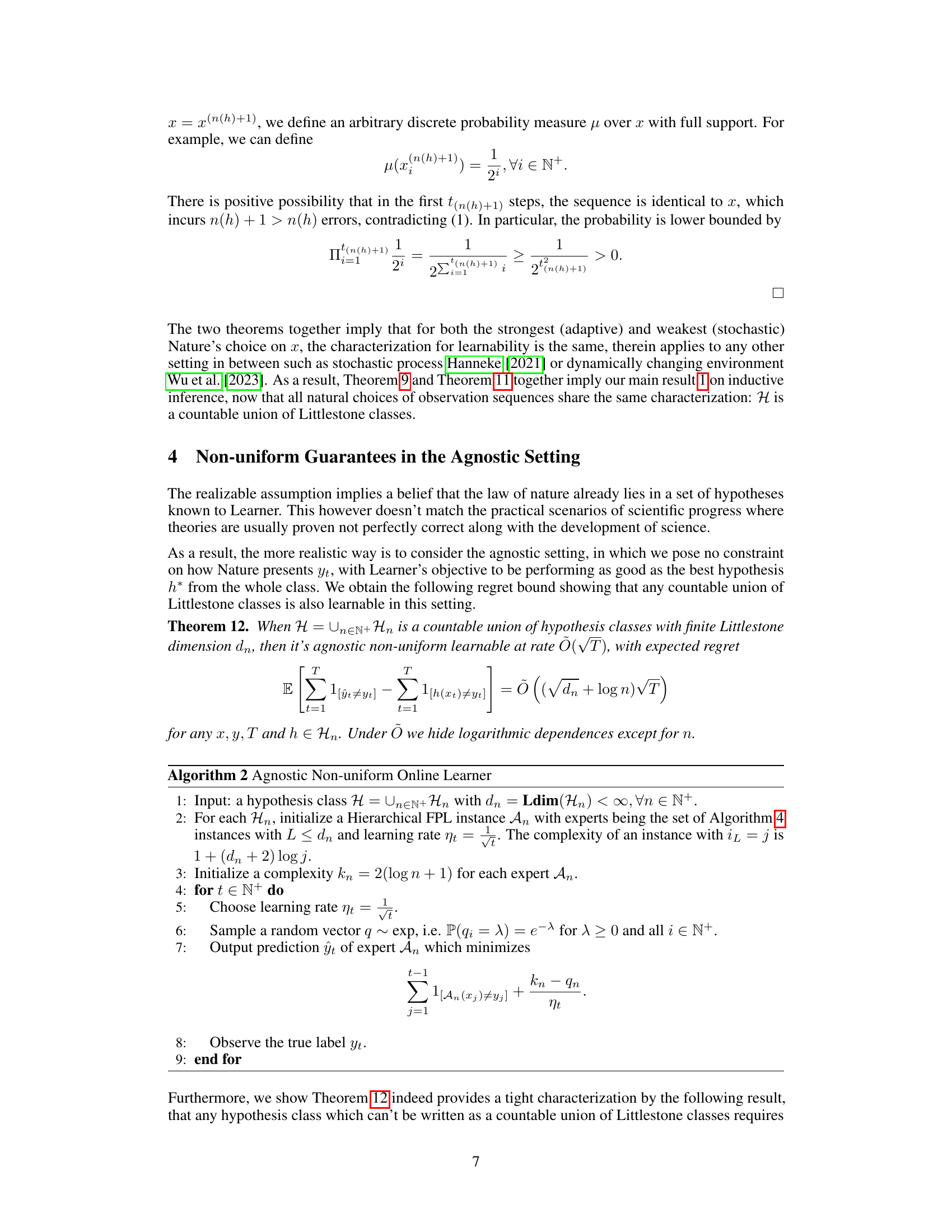

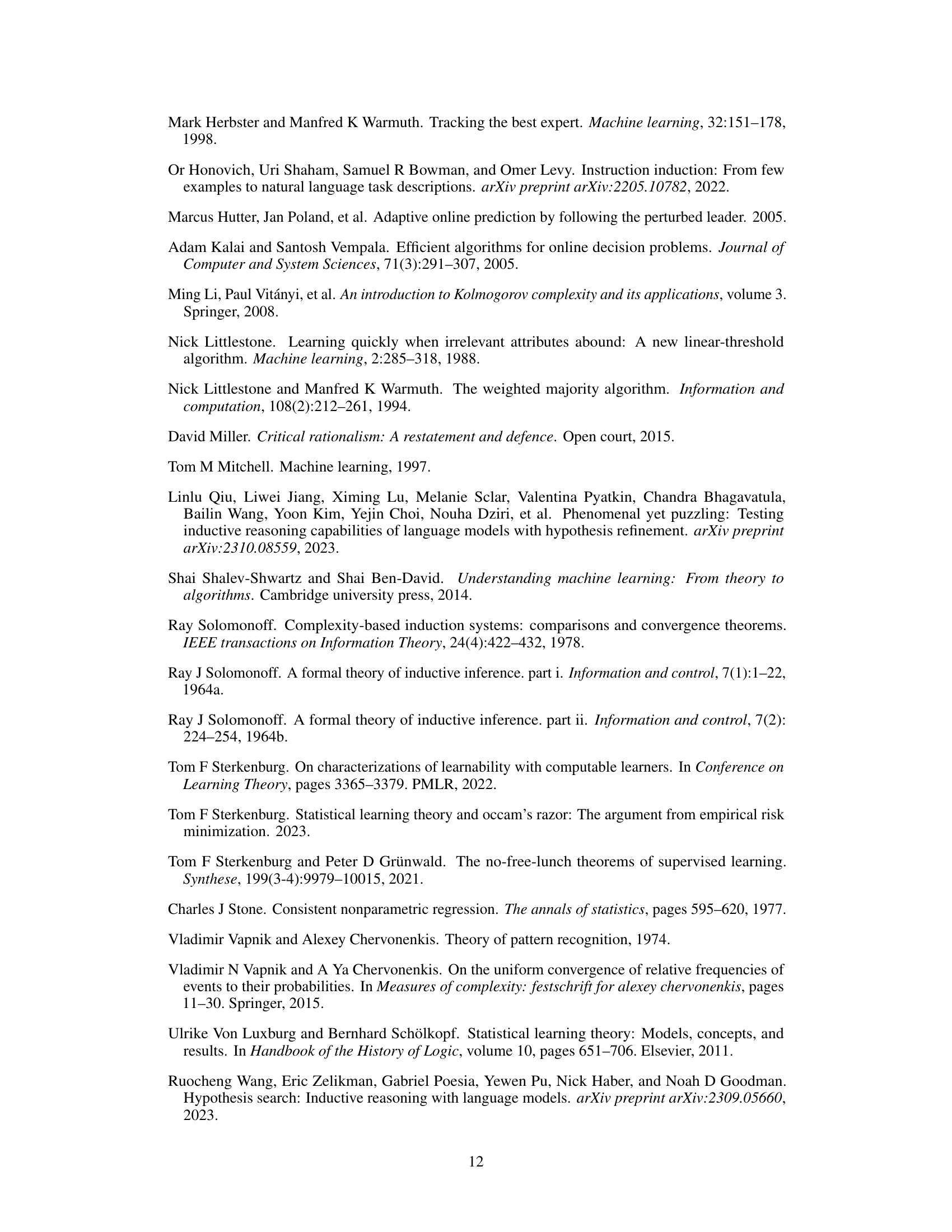

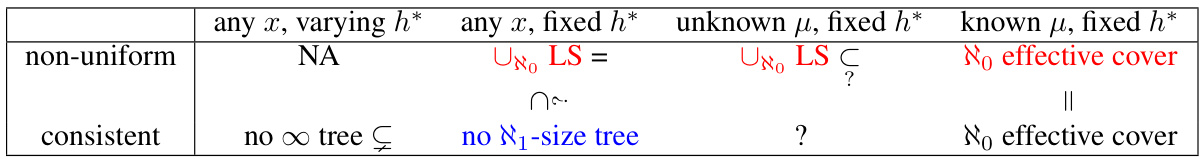

This table summarizes the results on various learnability notions in the non-uniform realizable setting of online learning. It compares the learnability of a hypothesis class H under different conditions: when the ground truth hypothesis h is fixed or varies across runs, whether the distribution μ is known or unknown to the learner, and based on various learning criteria such as uniform, non-uniform, and consistency. The table highlights the sufficient and necessary conditions established in the paper, indicating which cases are learnable and which require specific conditions. Results established by the authors are marked in red, whereas necessary conditions are highlighted in blue.

This table summarizes the learnability results for hypothesis classes under different conditions in the non-uniform realizable setting of online learning. It compares learnability under various conditions of Nature selecting the observations (any x, varying h*; any x, fixed h*; unknown μ, fixed h*; known μ, fixed h*) with the criterion being non-uniform or consistent. Our contributions (sufficient and necessary conditions) are highlighted in red, while necessary conditions are shown in blue. Each cell shows whether or not a condition is met for a hypothesis class to be learnable.

Full paper#