↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world problems involve estimating low-dimensional quantities using high-dimensional models. Traditional methods based on influence functions demand complex manual derivations, hindering widespread adoption. This limitation is particularly acute in high-dimensional settings where computational cost and analytical complexity dramatically increase.

This paper introduces Monte Carlo Efficient Influence Functions (MC-EIF), a fully automated method for approximating efficient influence functions. MC-EIF leverages automatic differentiation and probabilistic programming to efficiently compute EIFs, making complex calculations significantly easier. The method is shown to be consistent and achieves optimal convergence rates, outperforming existing automated approaches in empirical evaluations. MC-EIF offers a general and scalable solution, extending the reach of efficient statistical estimation to a far broader class of models and functionals than previously possible.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers seeking to automate efficient statistical estimation. It bridges the gap between theoretical advancements in efficient influence functions and practical implementation, opening avenues for research in high-dimensional models and improving the efficiency of existing estimators. The proposed MC-EIF method simplifies complex mathematical derivations, making efficient estimation accessible to a wider range of researchers.

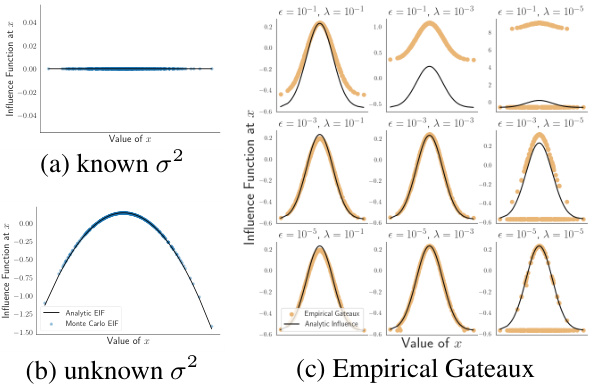

Visual Insights#

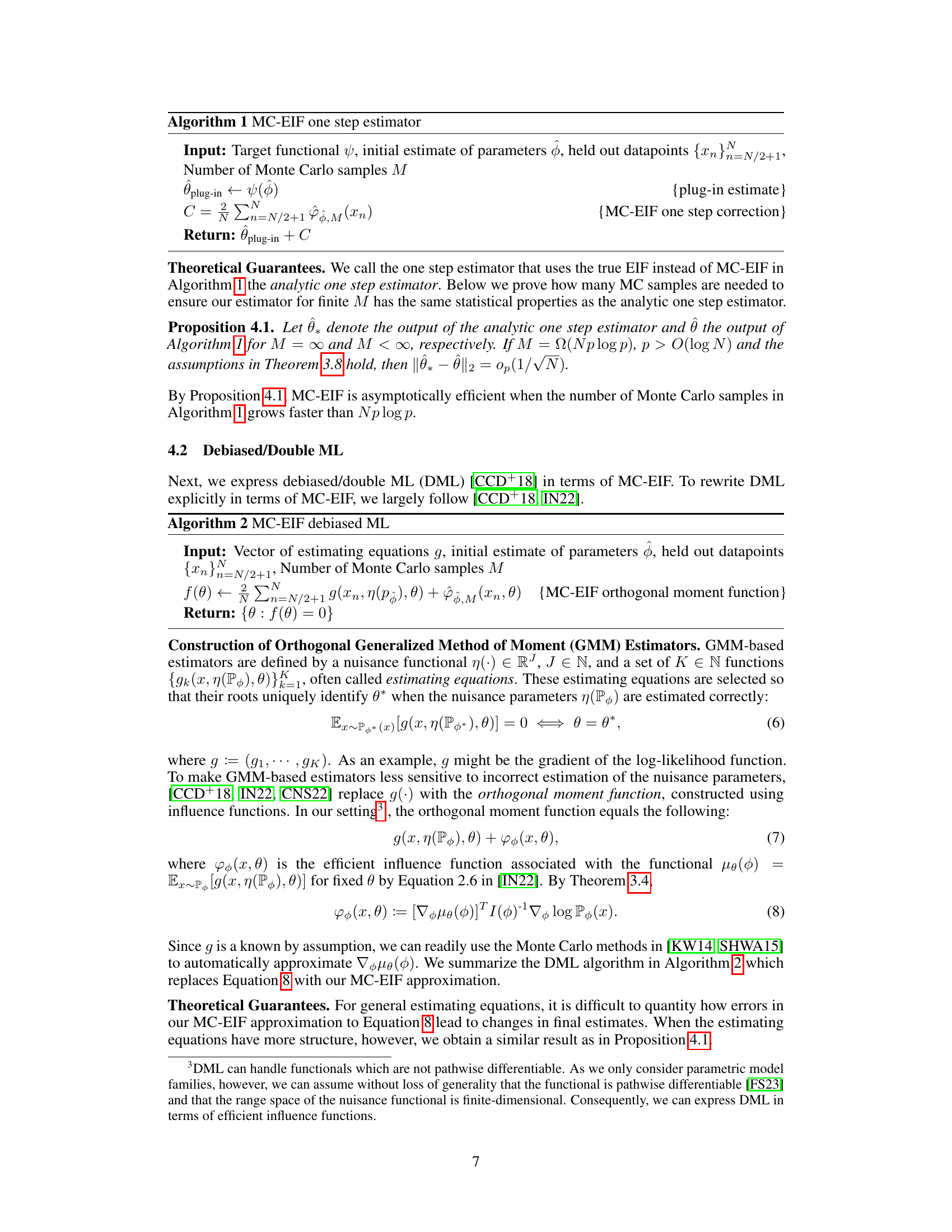

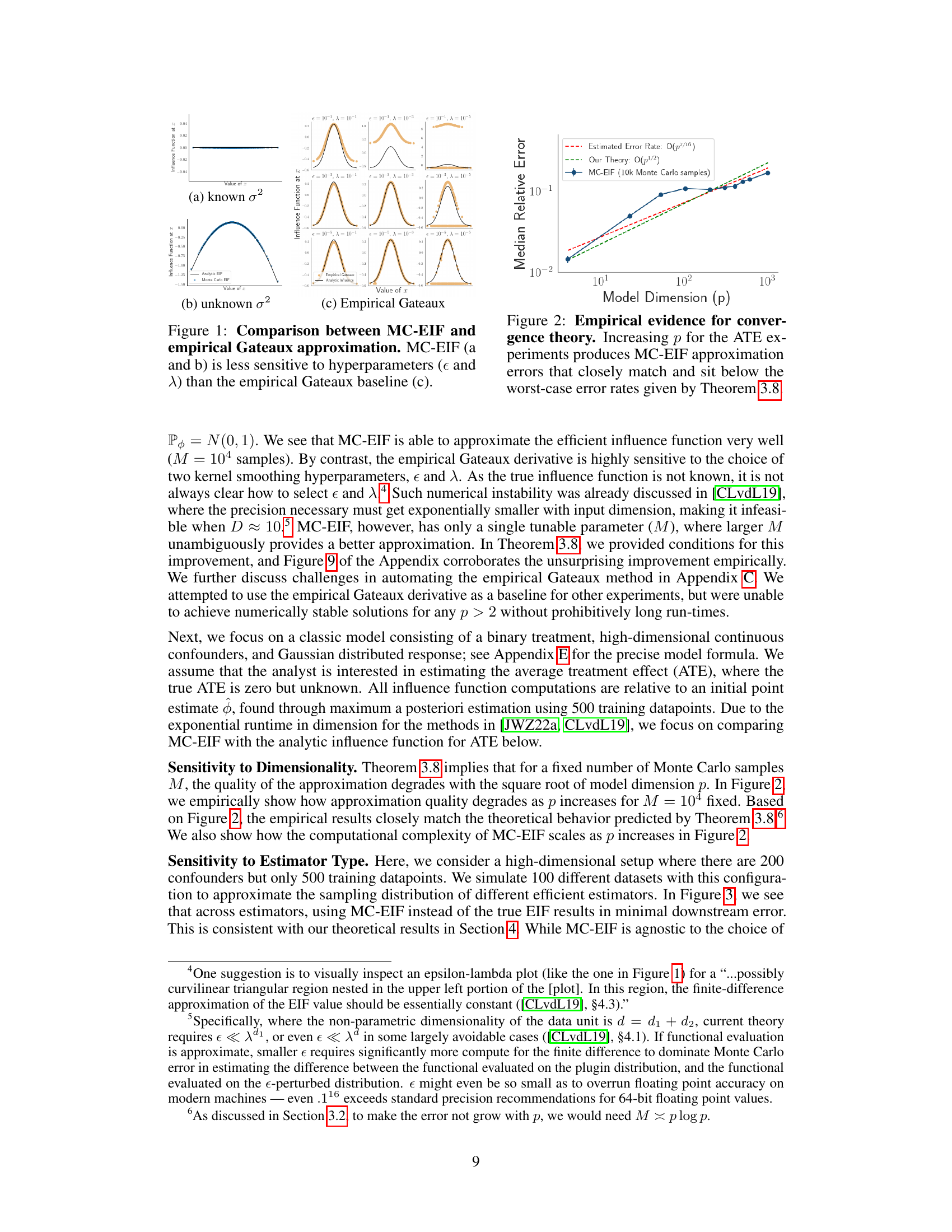

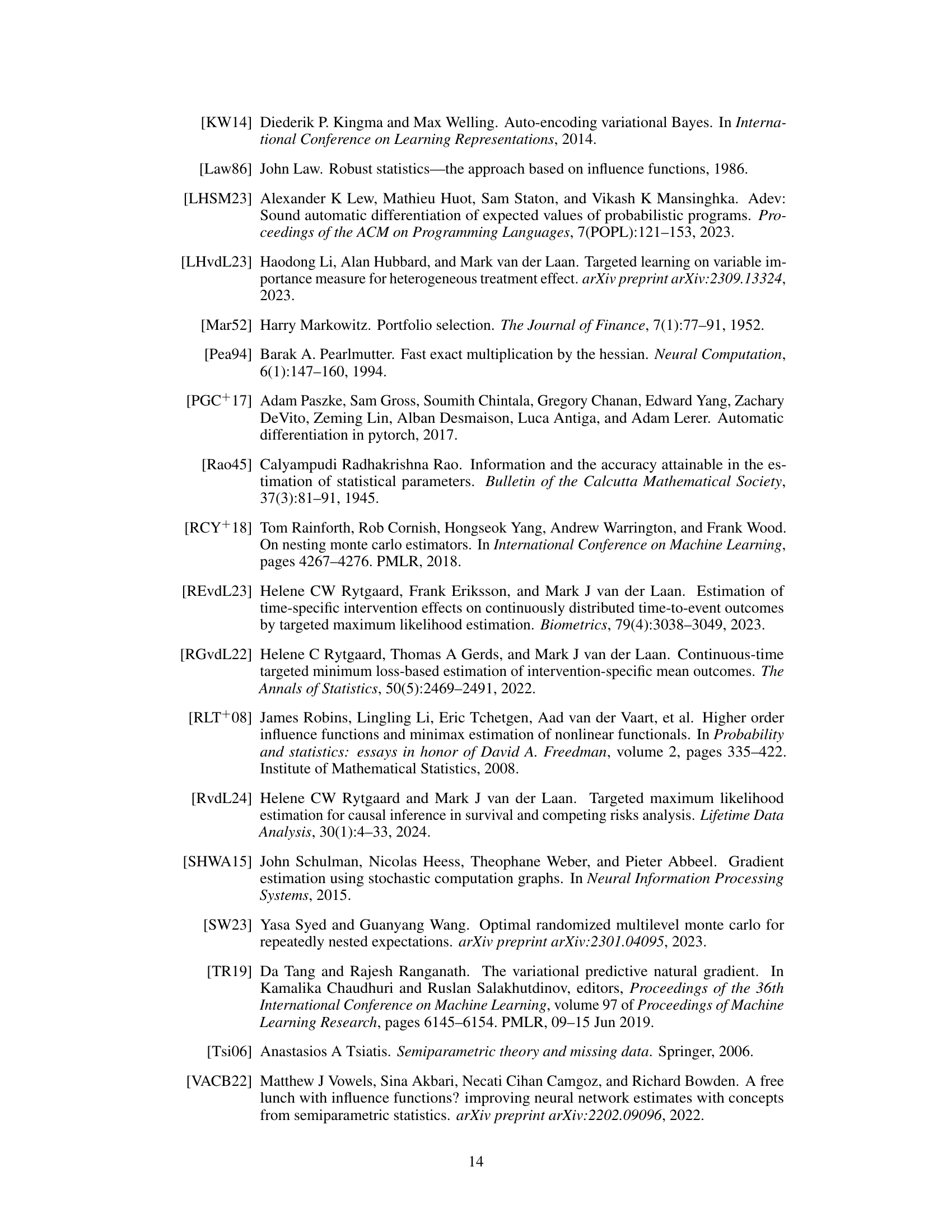

This figure compares the performance of Monte Carlo Efficient Influence Functions (MC-EIF) and the empirical Gateaux method for approximating influence functions. It shows that MC-EIF is less sensitive to the choice of hyperparameters (epsilon and lambda) than the empirical Gateaux method, which is highly sensitive to these parameters. The figure demonstrates that MC-EIF provides a more robust and accurate approach for approximating influence functions, particularly in high-dimensional settings.

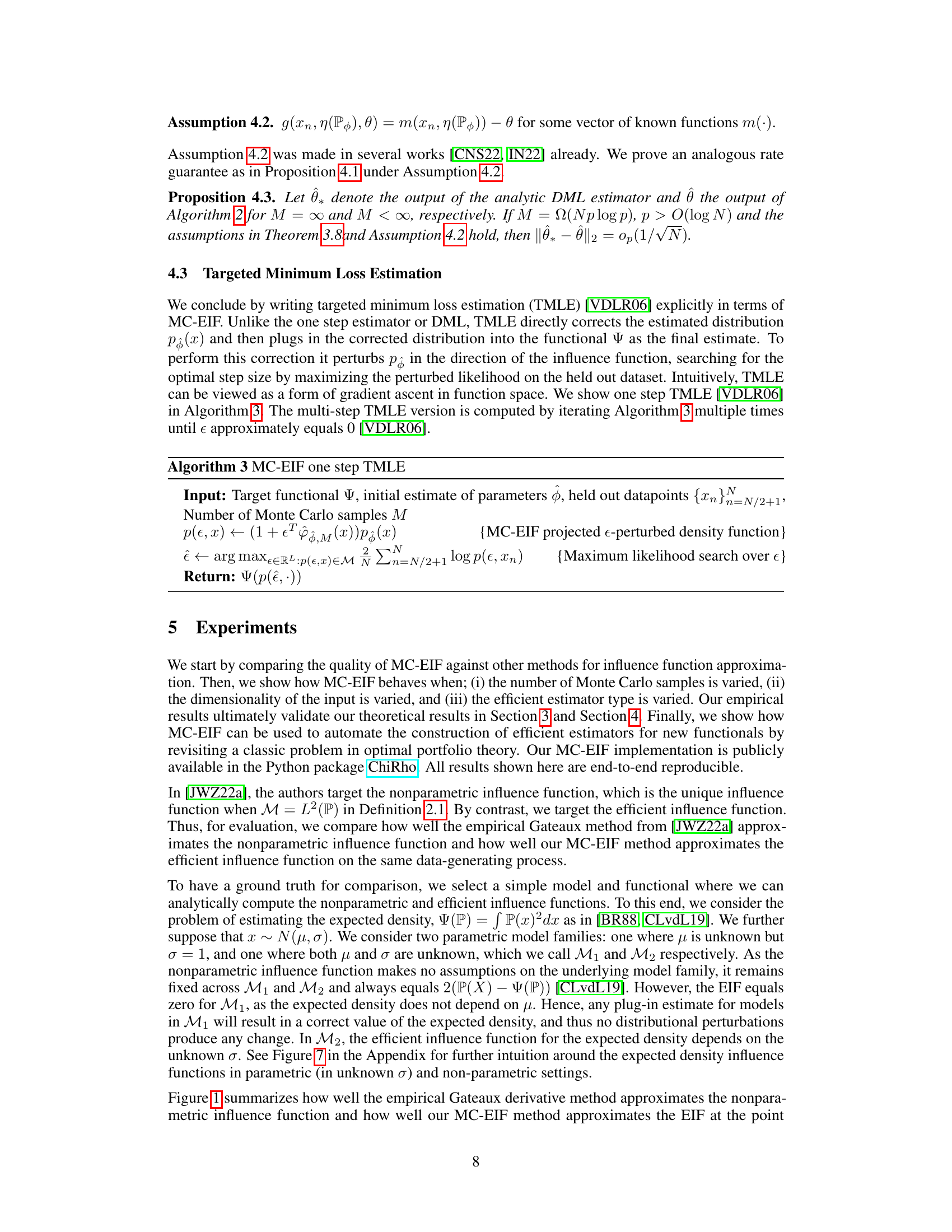

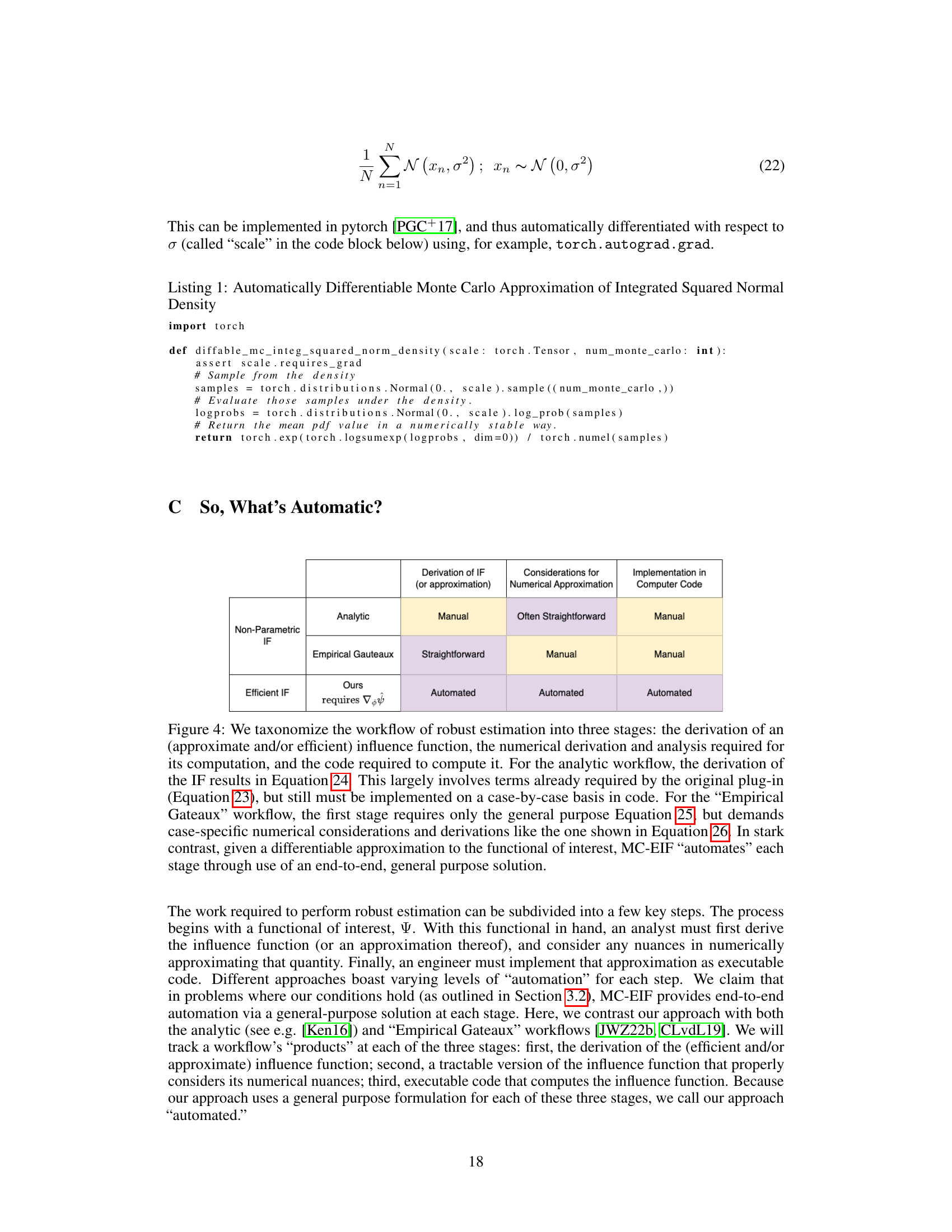

This table presents the empirical results of applying the Monte Carlo Efficient Influence Function (MC-EIF) method to the Markowitz optimal portfolio optimization problem. It compares the performance of the MC-EIF one-step estimator (Algorithm 1 from the paper) against a plug-in estimator and an oracle estimator (which uses the true, analytically derived efficient influence function). The results are presented in terms of Relative Expected Volatility (REV) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). Lower REV and RMSE values indicate better performance, suggesting MC-EIF achieves comparable or even better results than the oracle, especially in terms of reducing volatility.

In-depth insights#

MC-EIF Algorithm#

The Monte Carlo Efficient Influence Function (MC-EIF) algorithm offers a novel, fully automated approach to approximating efficient influence functions. Its key innovation lies in leveraging readily available quantities from differentiable probabilistic programming systems, eliminating the need for complex manual derivations often required by traditional methods. MC-EIF seamlessly integrates with automatic differentiation, enabling efficient statistical estimation for a broader class of models and functionals. Theoretical guarantees are established, proving consistency and optimal convergence rates, indicating that estimators using MC-EIF achieve comparable accuracy to those employing analytically derived EIFs. Empirical results corroborate these findings, showcasing the method’s accuracy and general applicability. While MC-EIF handles high-dimensional parametric models effectively, it relies on differentiability assumptions about the model and functional, potentially limiting its application to certain non-parametric or latent variable models. The algorithm’s practical significance lies in its potential to democratize efficient statistical estimation, removing significant mathematical barriers and making advanced statistical methods accessible to a wider range of researchers and practitioners.

Asymptotic Efficiency#

Asymptotic efficiency, in the context of statistical estimation, describes how well an estimator performs as the sample size grows infinitely large. The core idea is that an asymptotically efficient estimator converges to the true value of the parameter being estimated at the fastest possible rate, achieving the Cramér-Rao lower bound. This implies that the estimator’s variance shrinks as quickly as theoretically possible. The paper likely demonstrates that, under specific conditions, their Monte Carlo Efficient Influence Function (MC-EIF) method produces estimators that achieve asymptotic efficiency. This is a significant result, as it suggests that even without the complexity of deriving analytic Efficient Influence Functions (EIFs), MC-EIF can still provide optimal statistical properties in large samples. However, it’s crucial to understand that asymptotic efficiency is a large-sample property. It doesn’t guarantee good performance with limited data. Furthermore, the assumptions underlying the proof of asymptotic efficiency are key; violations could significantly impact the practical performance. The paper should clearly state these assumptions and discuss their plausibility in real-world applications. The practical advantages of MC-EIF are significant if it maintains efficiency even under violations or relaxations of the assumptions. The paper should showcase empirical evidence demonstrating MC-EIF’s performance in finite samples to complement the theoretical asymptotic analysis. The balance between theoretical guarantees and practical performance in finite samples is crucial for the overall impact of the MC-EIF method.

Empirical Validation#

An Empirical Validation section in a research paper would rigorously assess the claims made. It would present concrete evidence supporting the theoretical contributions and algorithms. This might involve demonstrating the accuracy and efficiency of a proposed method through simulations and experiments on real-world datasets. Crucially, it should include comparisons against existing state-of-the-art approaches. The results should be presented clearly, typically through tables, graphs, and statistical measures like confidence intervals, highlighting the practical significance and reliability of the findings. Addressing potential limitations of the empirical evaluation is vital, such as the choices of datasets, the use of specific hyperparameters, or whether the findings hold under varying conditions, would provide a more robust and complete validation.

Limitations of MC-EIF#

The Monte Carlo Efficient Influence Function (MC-EIF) method, while powerful, has limitations. Its reliance on the differentiability of both the likelihood and the target functional restricts its applicability to certain model classes and functionals. While MC-EIF handles high-dimensional nuisance parameters effectively, its computational cost scales with model complexity. The approximation error in MC-EIF, while theoretically bounded, can impact the accuracy of estimates, especially with fewer Monte Carlo samples. Furthermore, the method’s dependence on the invertibility of the Fisher information matrix necessitates careful consideration in cases of high-dimensional or poorly conditioned problems. Finally, while MC-EIF automates efficient estimation for a large class of problems, it may not offer advantages in situations where analytic solutions are readily available, or when dealing with very high dimensional data where computational challenges outweigh efficiency benefits.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this Monte Carlo Efficient Influence Functions (MC-EIF) paper are multifaceted. Extending MC-EIF to handle non-differentiable functionals is crucial, as many real-world problems involve such scenarios. This might involve exploring techniques like smoothing or using alternative approximation methods. Improving the efficiency of MC-EIF is another key area; current scaling with plog(p) is a limitation. Investigating advanced linear algebra methods and alternative estimators for the Fisher Information Matrix could yield significant performance gains. Finally, applying MC-EIF to a broader range of models and functionals, particularly within complex causal inference settings and high-dimensional Bayesian models, would demonstrate its full potential and expand its practical utility. The exploration of theoretical guarantees in these expanded domains needs careful consideration. Also, comparing MC-EIF’s performance against other automated EIF approximation techniques under diverse circumstances would solidify its standing. Ultimately, the development of a comprehensive, user-friendly software package implementing MC-EIF could significantly enhance its accessibility and impact within the statistical community.

More visual insights#

More on figures

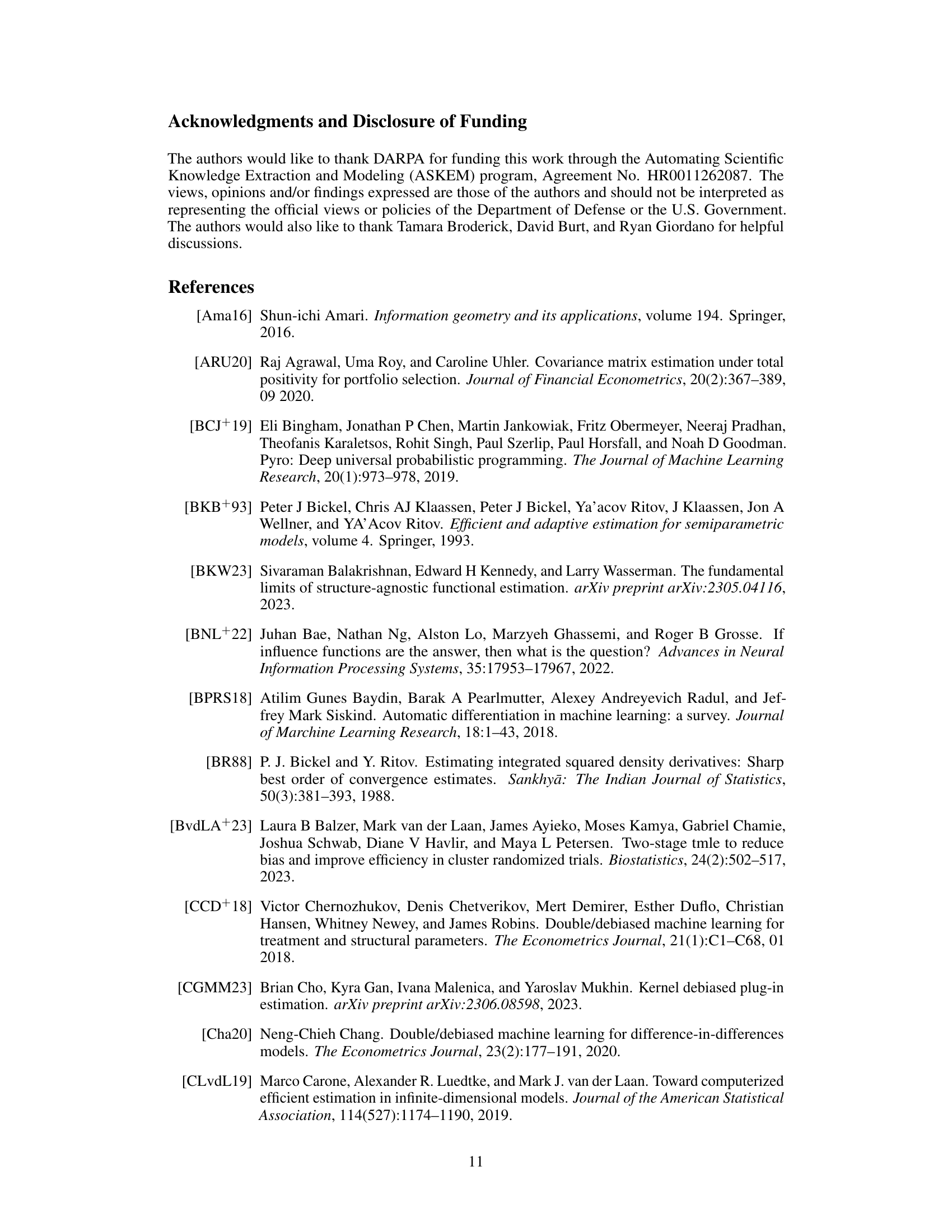

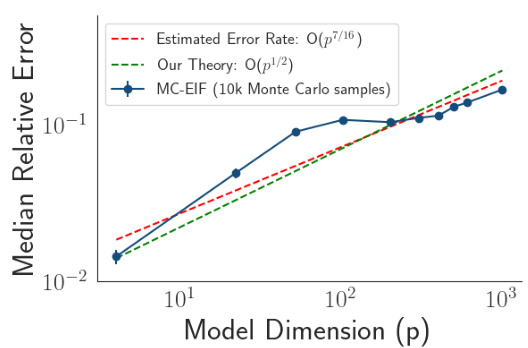

This figure empirically validates Theorem 3.8 in Section 3.2 by showing how the approximation error of MC-EIF scales with the model dimension (p) when estimating the average treatment effect (ATE). The plot shows that as p increases, the approximation error grows, but at a rate that closely matches and remains below the theoretical worst-case error bound derived in the theorem. This suggests that the MC-EIF estimator’s performance is consistent with the theoretical guarantees.

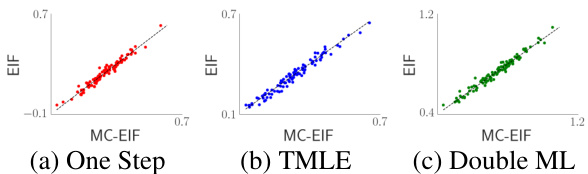

This figure compares the performance of three different efficient estimators (one-step, TMLE, and double ML) when using either the true efficient influence function (EIF) or the Monte Carlo approximation (MC-EIF). The plots show the estimated ATE on the y-axis against the MC-EIF estimate on the x-axis. Points close to the diagonal indicate that MC-EIF provides results similar to those obtained using the true EIF. The close proximity to the diagonal line for all three estimators suggests MC-EIF can be a very good replacement for the analytically derived EIF, regardless of which efficient estimation method is used.

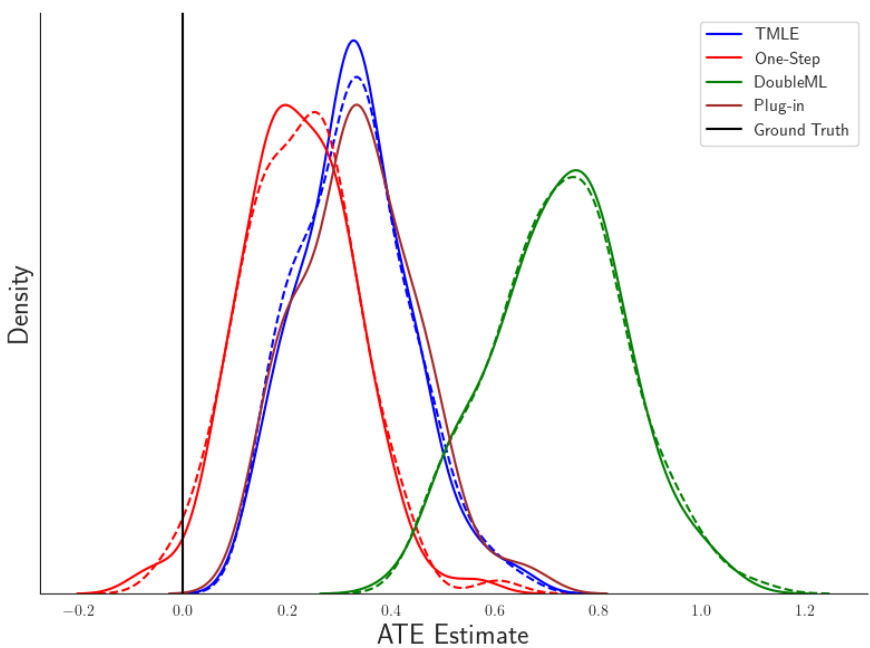

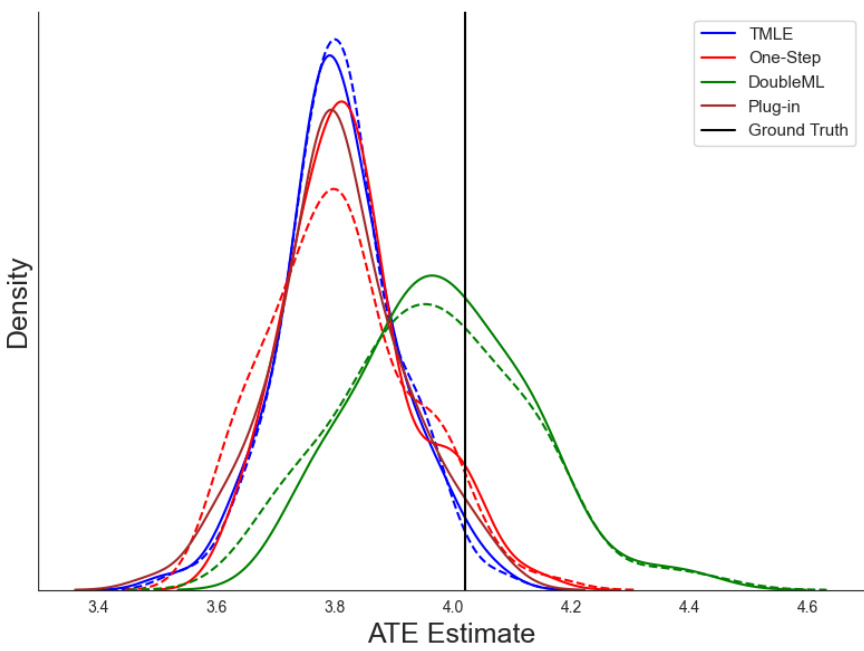

The figure shows the comparison of four different estimators (plug-in, one-step, doubleML, TMLE) for estimating the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) using both the analytical EIF and MC-EIF. The true ATE is 0. The results are based on 100 simulated datasets with high dimensionality, leading to some bias even after correction. The plot demonstrates that MC-EIF produces nearly identical results to using the analytical EIF for a variety of estimators. This highlights the effectiveness of MC-EIF in approximating the EIF in diverse settings.

The figure compares the performance of different ATE estimators (plug-in, one-step, double ML, TMLE) using both the true efficient influence function (EIF) and MC-EIF. The true ATE is 0, and the closer the estimate is to 0, the better. The distribution is based on 100 simulated datasets. Dashed lines represent estimates using the analytical EIF, while solid lines show MC-EIF results. The high dimensionality of the problem causes some bias to remain, even after influence function correction; this is inherent to influence-corrected estimators, not a flaw of MC-EIF. The figure illustrates MC-EIF produces comparable results to using the true EIF across various statistical tasks.

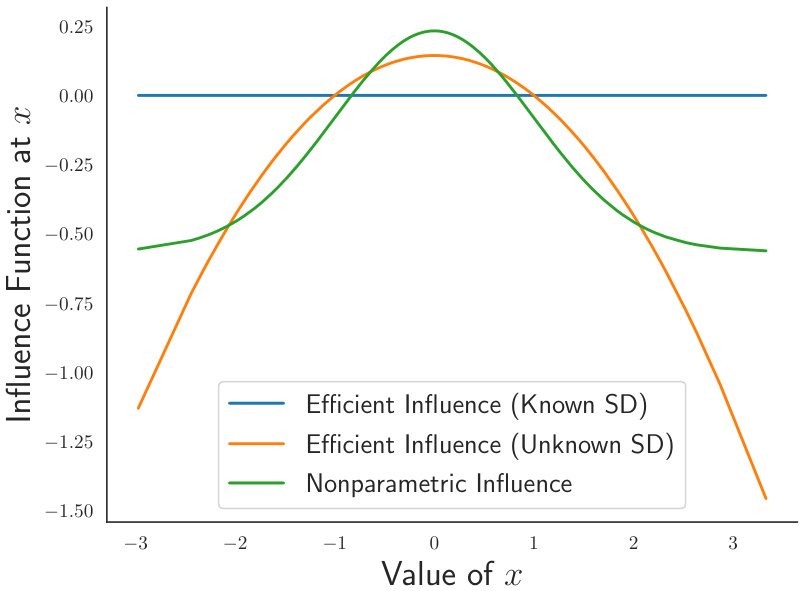

This figure compares three different influence functions for estimating the expected density. The nonparametric influence function makes no assumptions about the underlying data distribution. The efficient influence functions assume either that the standard deviation of the data is known or unknown. The figure shows how these different influence functions change as a function of the value of x. The efficient influence function with the known standard deviation is closest to zero, indicating that it is the most efficient estimator in this scenario. The nonparametric influence function is the least efficient.

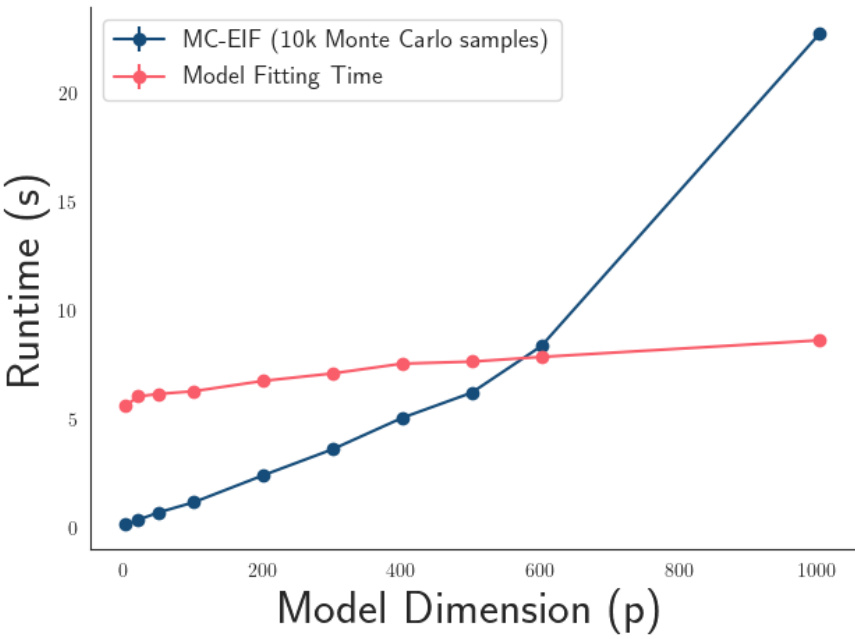

This figure shows how the runtime of the MC-EIF algorithm and the model fitting time scale with the model dimension (p). The x-axis represents the model dimension, and the y-axis represents the runtime in seconds. Two lines are plotted: one for the MC-EIF computation (with 10,000 Monte Carlo samples) and one for the time required to fit the model. The figure demonstrates that the MC-EIF runtime increases more rapidly than the model fitting time as the model dimension increases.

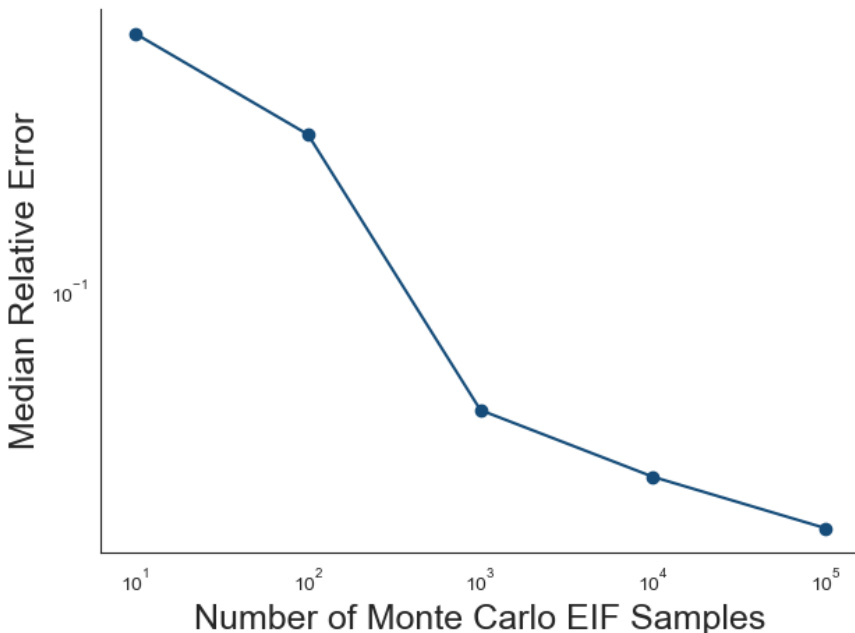

The figure shows the median relative error between the Monte Carlo Efficient Influence Function (MC-EIF) estimates and the true efficient influence function (EIF) values for an unknown variance model and the expected density functional. The median absolute error is calculated by randomly sampling points, computing the relative error at each point, and then taking the median across these errors. The x-axis represents the number of Monte Carlo samples used in the MC-EIF estimation, and the y-axis shows the median relative error. The plot demonstrates how the accuracy of the MC-EIF estimates improves as the number of Monte Carlo samples increases.

Full paper#