↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Understanding how humans perceive smells from chemical structures has been challenging due to a lack of large, well-annotated datasets. Current machine learning approaches rely on expert-labeled data, introducing biases and requiring significant effort. The limited availability of methods for describing odorants quantitatively or qualitatively further complicates this problem.

This study employs MoLFormer, a pre-trained transformer model, to encode chemical structures of odorants. The researchers demonstrate that MoLFormer’s representations align remarkably well with various aspects of human olfactory perception. These include predicting expert-assigned labels, continuous perceptual ratings, and similarity ratings between odorants, surpassing other models trained on limited datasets and outperforming those that rely exclusively on physicochemical descriptors. This study showcases the potential of transformer models in modeling human perception, even without direct supervision, using readily available data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between the chemical structure of odorants and human olfactory perception. This opens avenues for developing more accurate predictive models in the field of olfaction, potentially revolutionizing areas like fragrance design, environmental monitoring, and even medical diagnostics.

Visual Insights#

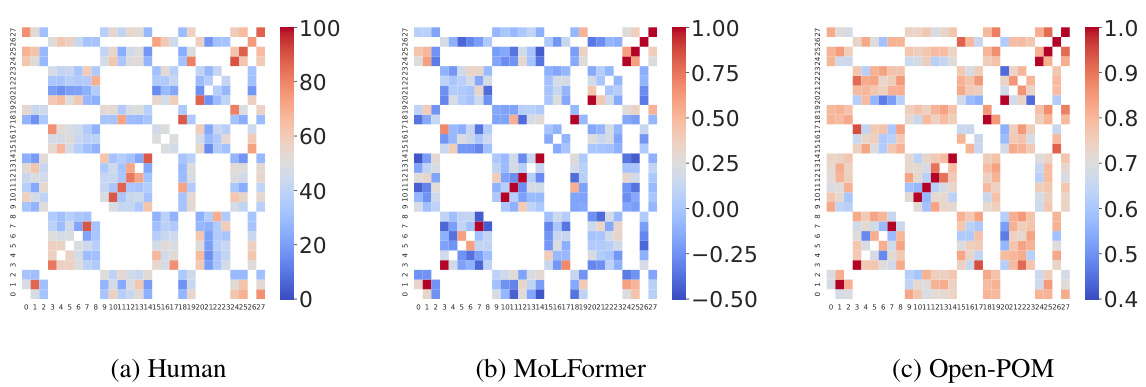

Human participants evaluate the perceptual similarity between two odorant substances. The same pair of odorants is encoded using MoLFormer, and the similarity between their representations is calculated. Finally, the alignment between human perceptual similarity and the MoLFormer-based similarity is measured.

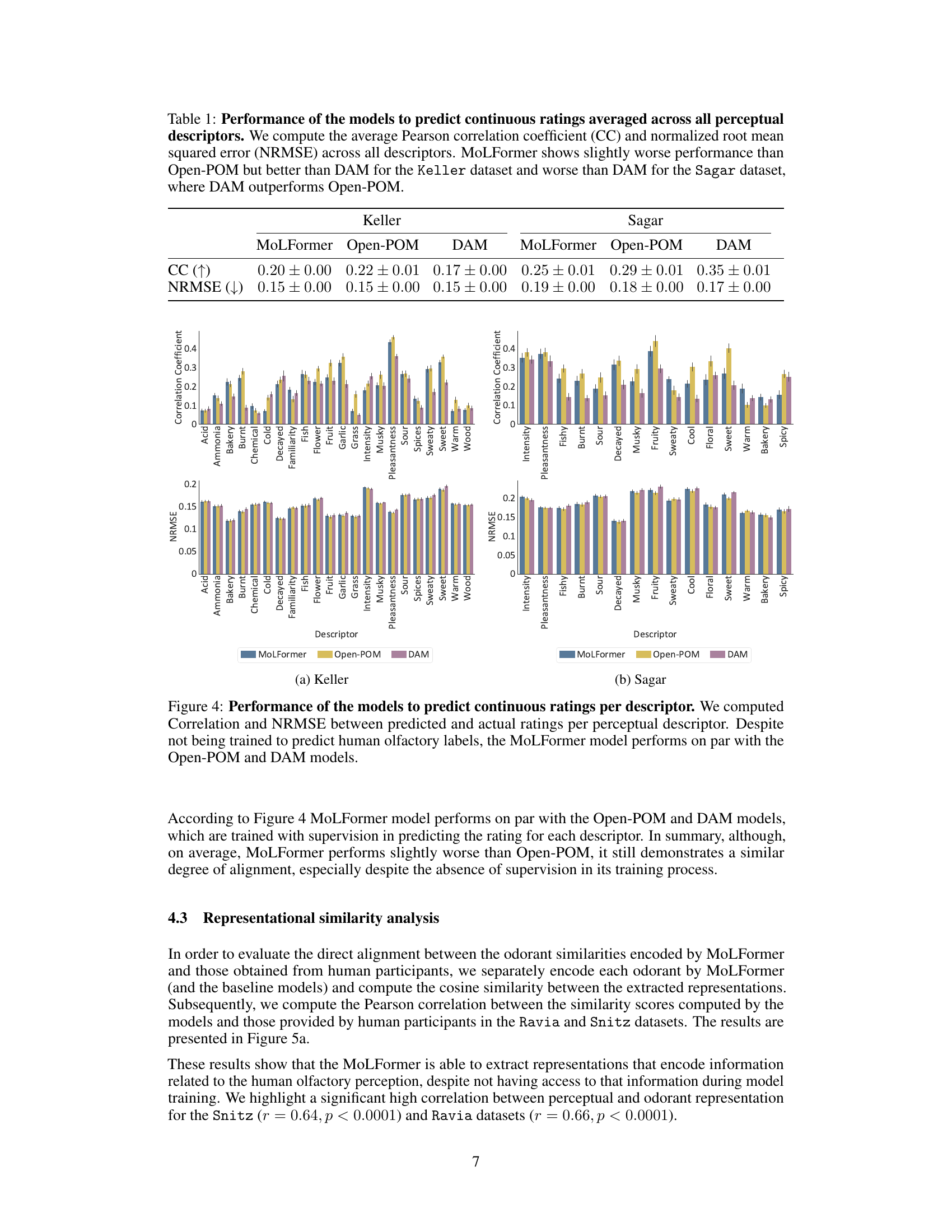

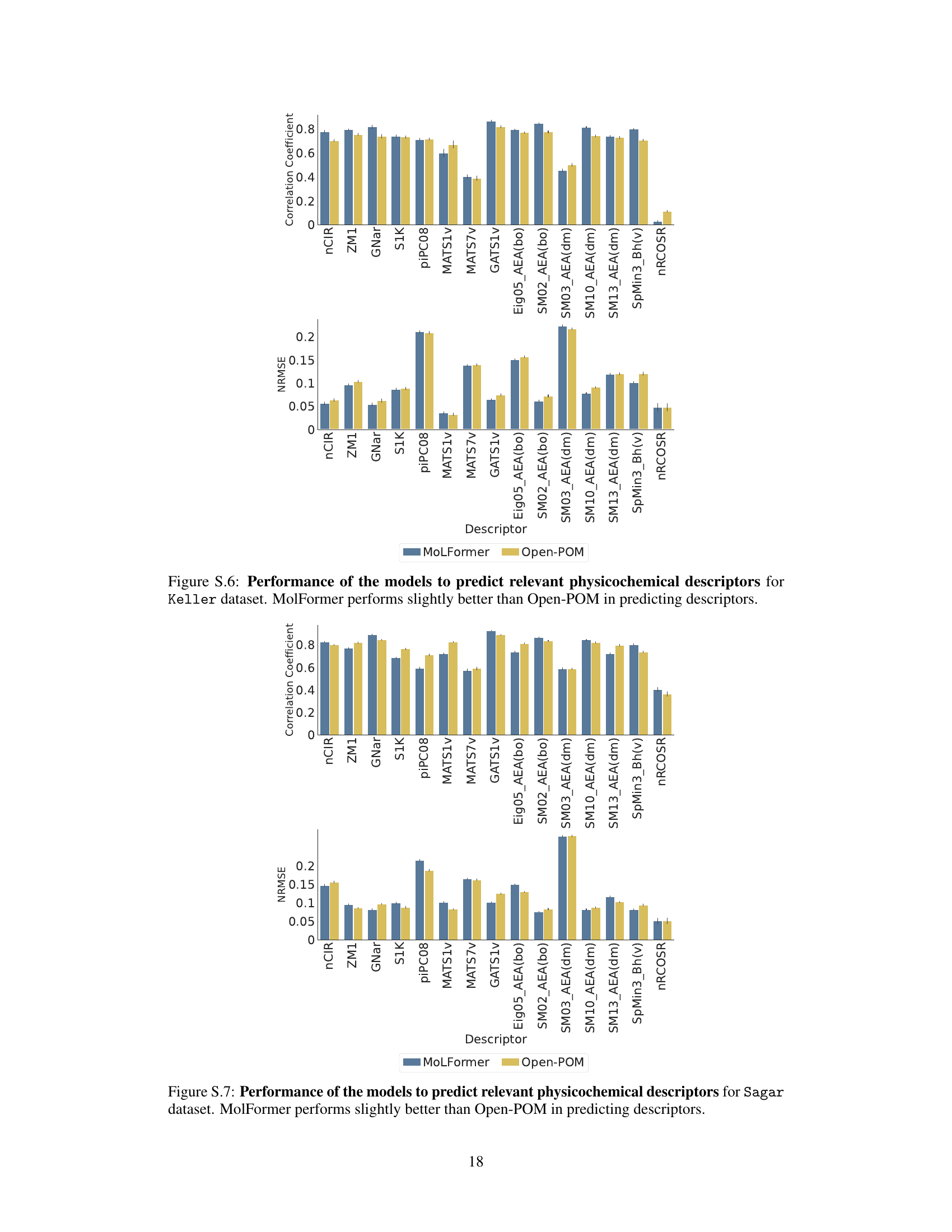

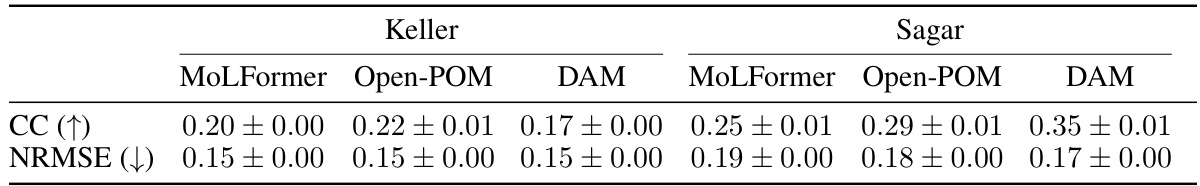

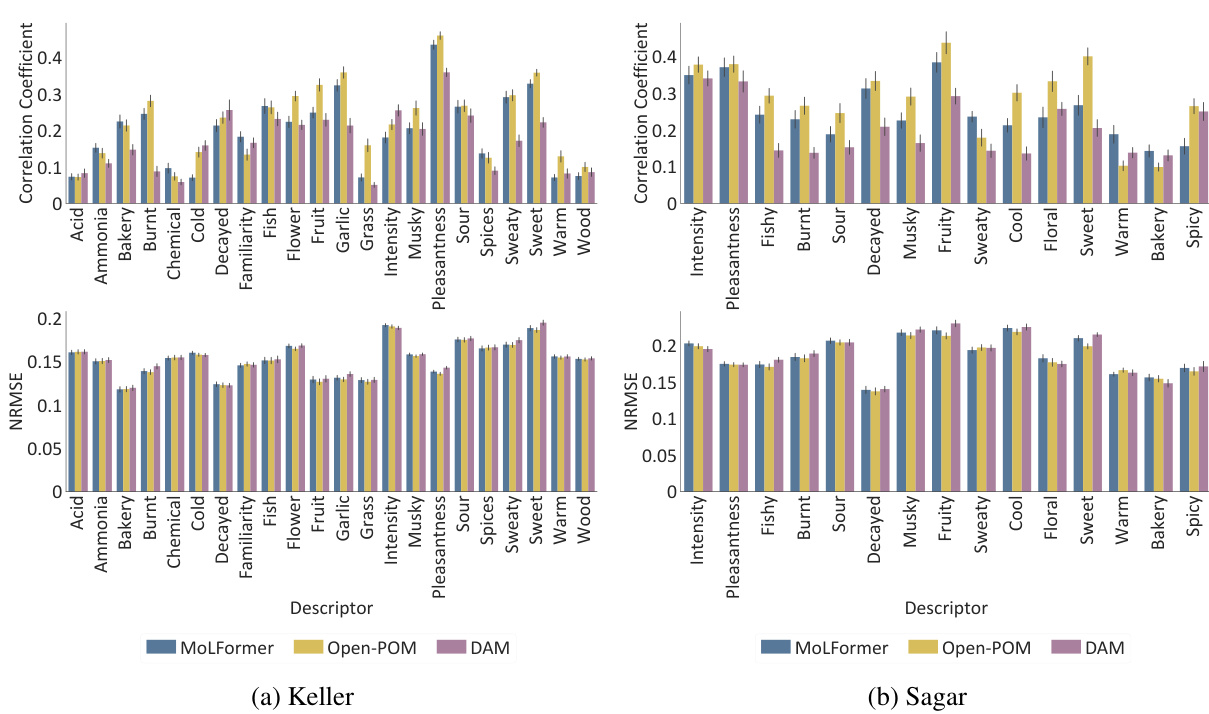

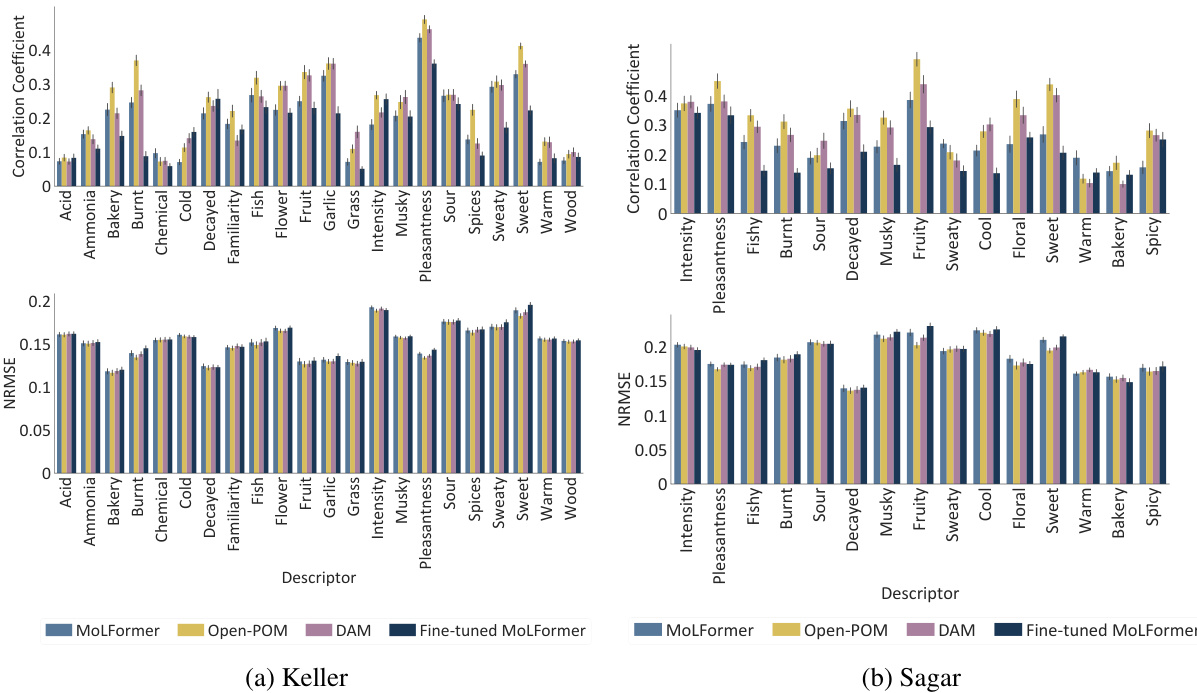

This table presents the performance of three different models (MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM) in predicting continuous perceptual ratings of odorants across two datasets (Keller and Sagar). The performance is measured using two metrics: Pearson correlation coefficient (CC) and Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE). Higher CC values indicate better prediction accuracy, while lower NRMSE values indicate better prediction accuracy. The table shows the average performance and standard deviation across all the descriptors in each dataset for each model.

In-depth insights#

Olfactory AI#

Olfactory AI is a burgeoning field aiming to replicate and even surpass human olfaction using artificial intelligence. Current limitations in large-scale, accurately labeled olfactory datasets hinder progress. This paper cleverly addresses this by leveraging pre-trained transformer models trained on chemical structures. The core insight is that these models, without explicit olfactory training, already encode representations surprisingly aligned with human olfactory perception. This alignment is demonstrated through multiple tests: predicting expert-labeled odor descriptors, predicting continuous human odor ratings, and correlating with human perceptual similarity judgments. The success highlights the power of transfer learning and self-supervised methods in olfactory AI, suggesting that rich, general-purpose chemical representations implicitly capture aspects critical for olfactory perception. Further investigation into the hierarchical structure of these representations is warranted to fully understand how low-level chemical features translate to higher-level perceptual experiences. The results offer valuable insights for both chemists and neuroscientists, opening new avenues for understanding and leveraging AI in the field of olfaction.

Transformer Power#

The heading ‘Transformer Power’ suggests an exploration of the capabilities and potential of transformer models, likely within the context of a specific application or task presented in the research paper. A thoughtful analysis would delve into how the paper defines and measures this ‘power’. Is it computational efficiency? Accuracy on a benchmark dataset? Ability to generalize to unseen data? Or perhaps something more nuanced, such as the model’s capacity to uncover hidden relationships or patterns within the data? The key would be to understand the metrics used to evaluate transformer performance and what those metrics reveal about the strengths and limitations of the approach in comparison to existing methods. Furthermore, a deeper examination would investigate what aspects of the transformer architecture contribute most significantly to this ‘power’. Are specific layers or components particularly crucial? Does the success depend on pre-training strategies or fine-tuning techniques? A truly in-depth analysis would also consider the limitations. Does the observed ‘power’ hold across a variety of datasets and contexts, or is it specific to a narrow application? This section of the paper should offer valuable insights into the potential and limitations of transformer models.

Human Alignment#

The concept of “Human Alignment” in the context of AI, especially concerning olfactory perception models, is crucial. It probes how well an AI’s representation of smells matches human sensory experience. Achieving high alignment means the AI’s internal representation accurately reflects human perception of odorants, enabling better predictions of human responses to smells. The paper investigates this alignment using pre-trained transformer models, evaluating their ability to predict expert-labeled odor descriptors, continuous human rating scores, and similarity judgments between odorants. Key to this is understanding how the AI encodes chemical structures to capture the nuanced aspects of human olfactory perception. The alignment is also analyzed in relation to physicochemical properties of odorants, revealing connections between AI representations and the underlying chemical features that humans perceive. Ultimately, this research showcases a path towards building AI systems that can interpret and generate olfactory data in a human-like manner, bridging the gap between machine learning and human sensory experience.

Model Limits#

A dedicated ‘Model Limits’ section would delve into the inherent constraints of the transformer models used. This would include limitations stemming from the pre-training data, acknowledging that biases present in the chemical structure datasets could skew olfactory perception predictions. A discussion on the model architecture’s capacity to capture the full complexity of human olfactory perception is also crucial; transformers, while powerful, may not perfectly represent the high-dimensional and nuanced nature of smell. Addressing the generalizability of findings across diverse odorants and datasets is important; results from specific datasets might not universally apply. Finally, the reliance on indirect measures of olfactory perception (expert labels, similarity ratings) should be acknowledged as introducing potential inaccuracies. Further research could involve investigating more comprehensive datasets, advanced model architectures, and exploring the integration of physicochemical features more directly into the models for more comprehensive and accurate results.

Future AI Smell#

The prospect of “Future AI Smell” is exciting, hinting at significant advancements in AI’s ability to process and interpret olfactory information. Current limitations in data availability and the complexity of olfactory perception pose challenges. However, future breakthroughs could involve more sophisticated machine learning models, trained on larger, higher-quality datasets of odorant chemical structures and corresponding human perceptual responses. Combining AI with advanced sensor technology could lead to AI systems capable of identifying and classifying odors with unprecedented accuracy, opening doors for applications in many areas such as environmental monitoring, disease diagnosis, food safety, and personalized medicine. Progress in understanding the neural mechanisms of olfaction will play a crucial role, informing the design of more biologically plausible AI models. Ultimately, “Future AI Smell” promises a revolution in our interaction with the world, leveraging the power of AI to unlock the rich, complex information embedded within scents. This requires interdisciplinary collaboration between AI researchers, chemists, neuroscientists, and engineers.

More visual insights#

More on figures

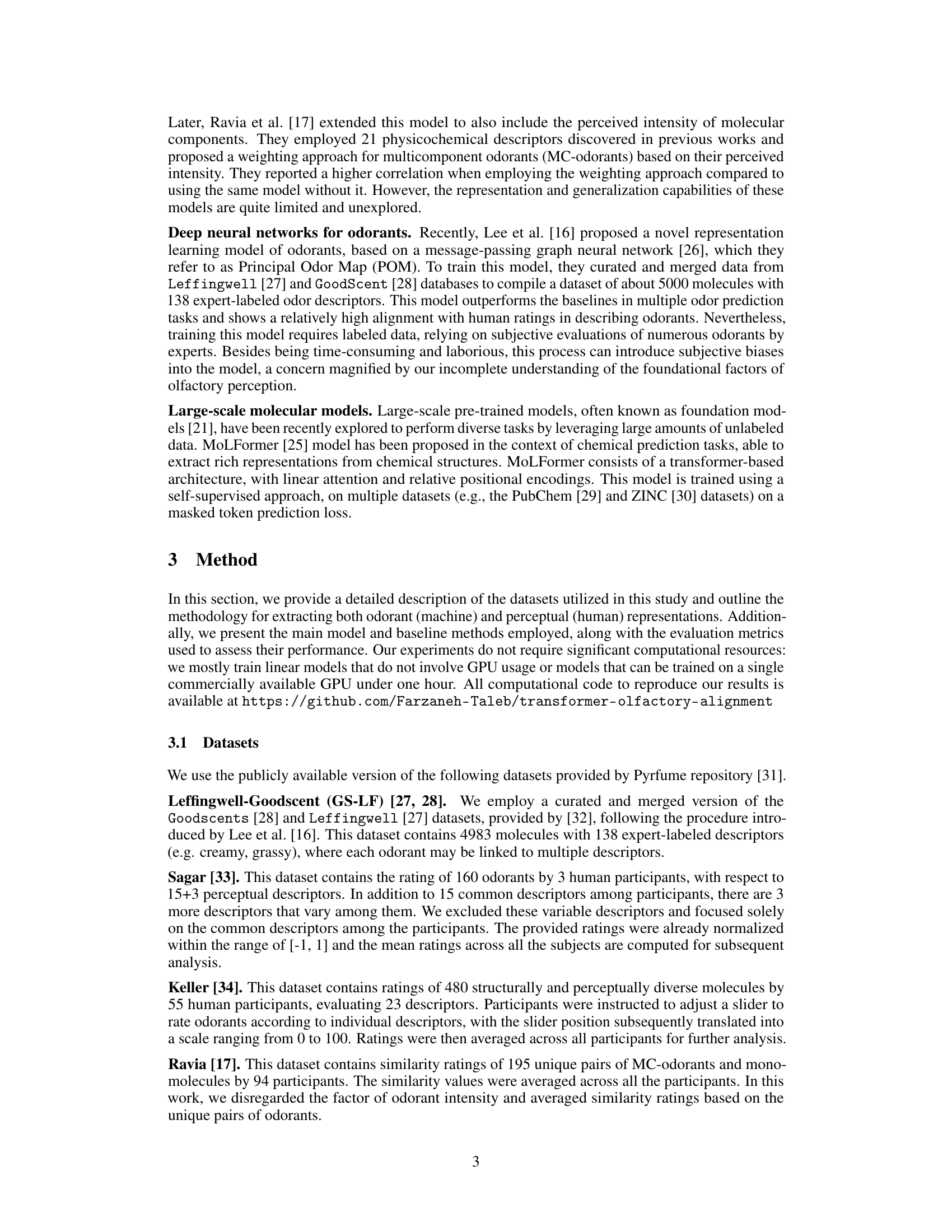

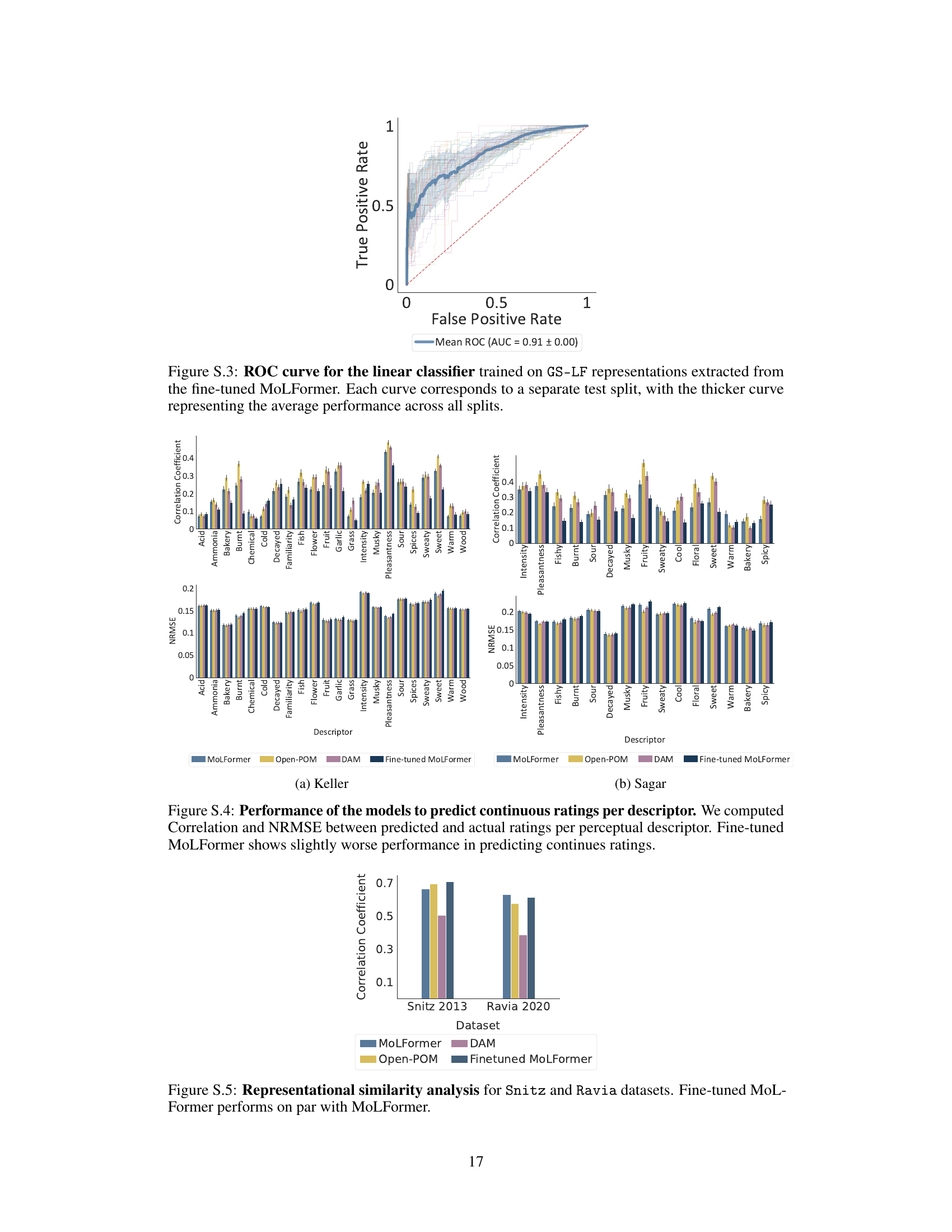

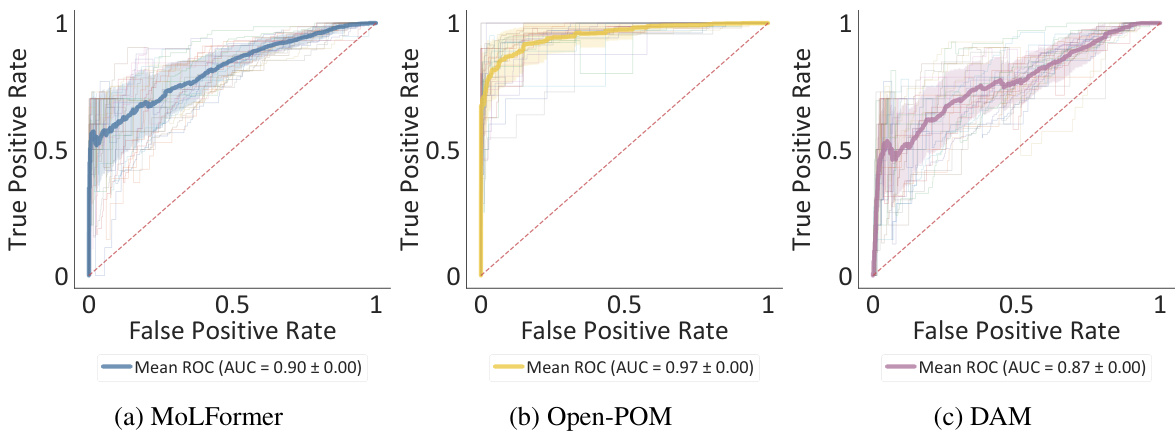

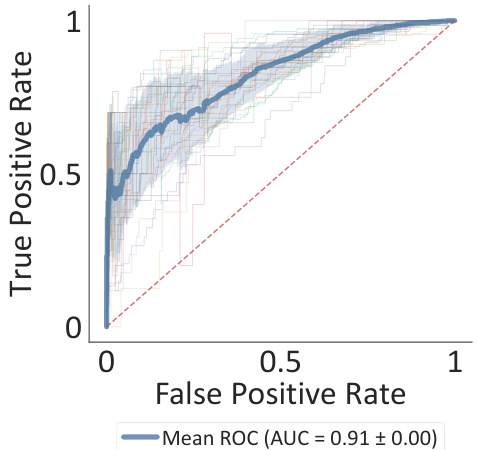

This figure shows the ROC curves for three different models (MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM) trained on the GS-LF dataset to predict expert-assigned odor labels. Each thin line represents a single train-test split, while the thicker line represents the average performance across all splits. The results demonstrate that MoLFormer outperforms DAM, even though it wasn’t explicitly trained for this task. However, Open-POM achieves the best performance, which is expected because it was trained for this specific task.

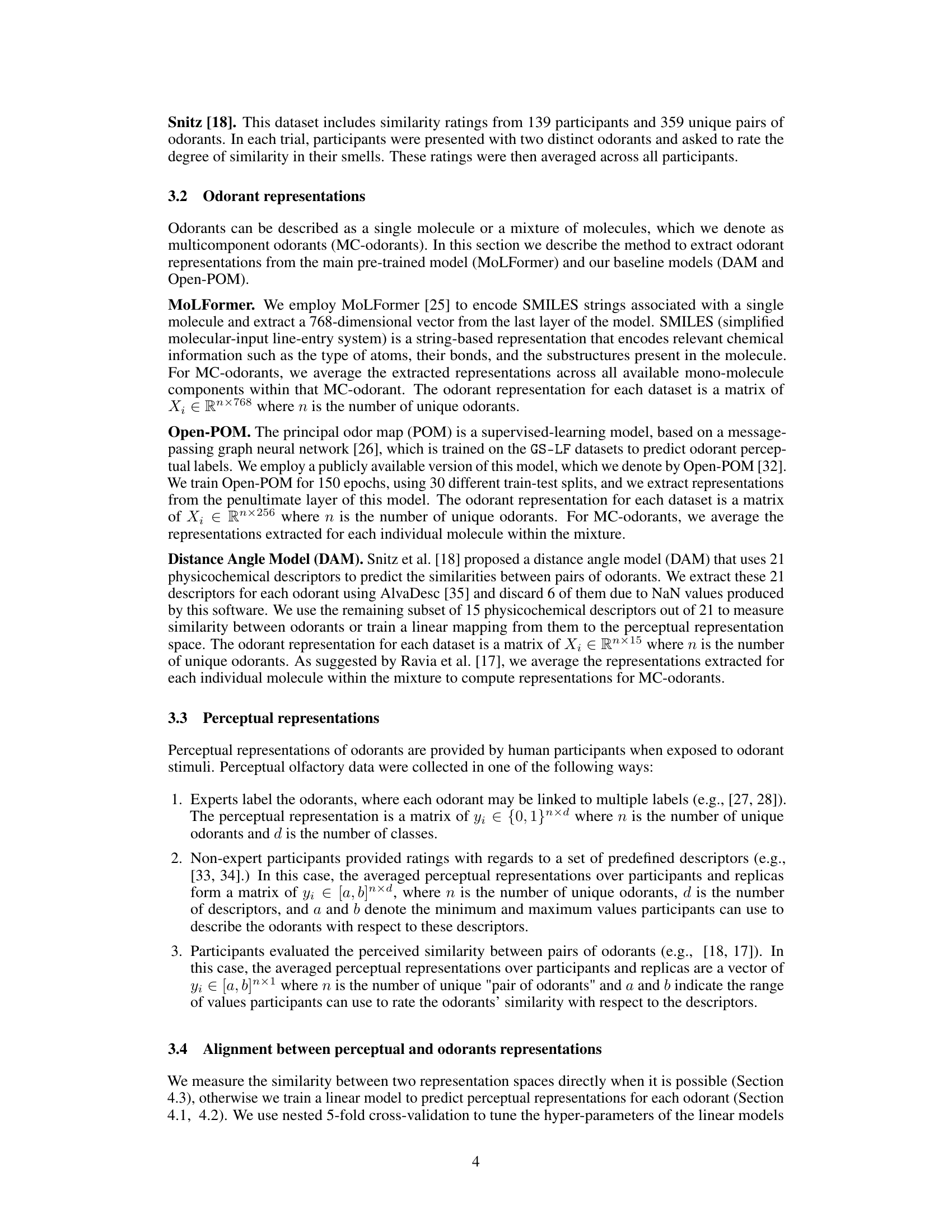

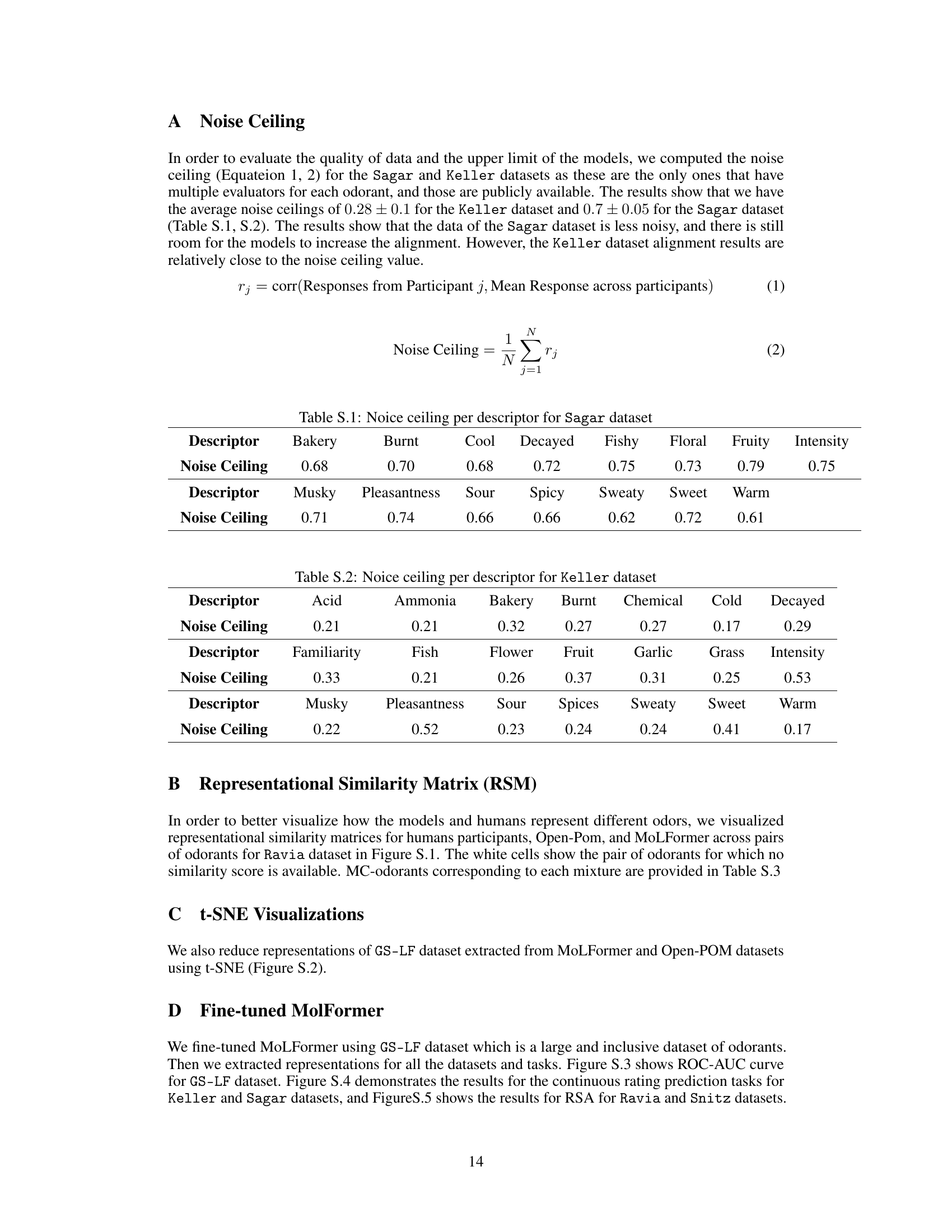

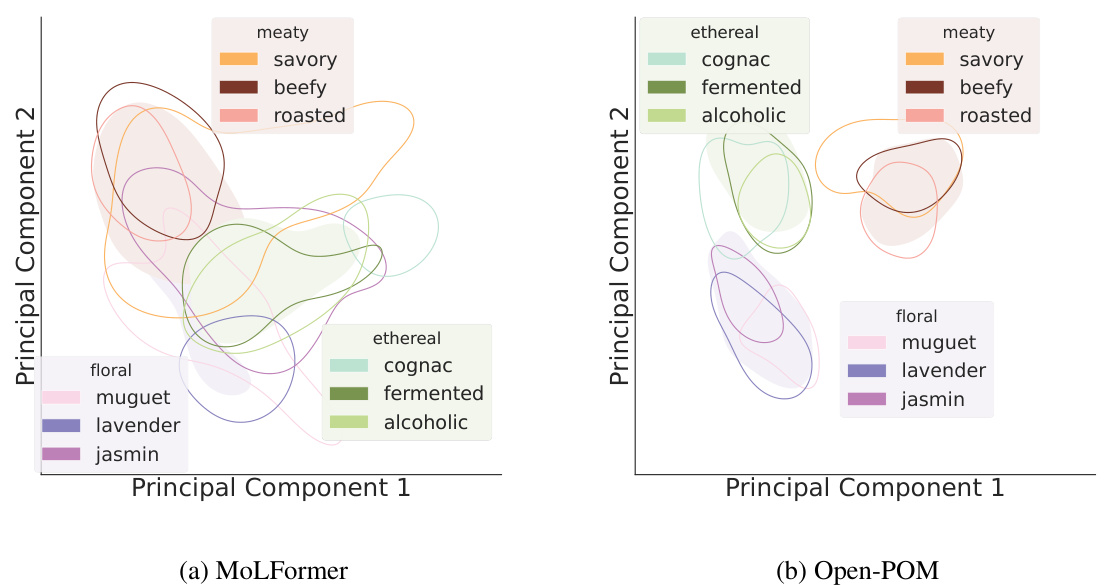

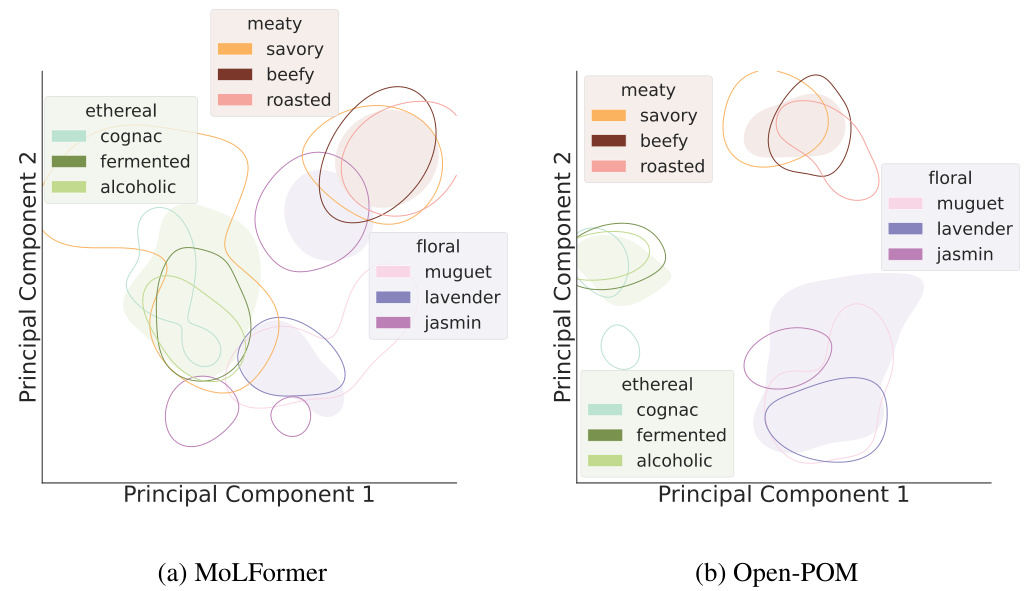

This figure visualizes the odorant representations generated by MoLFormer and Open-POM models on the GS-LF dataset. It uses the first two principal components to represent the data, showing clusters of molecules with similar broad or narrow perceptual labels. The visualization highlights MoLFormer’s ability to capture the perceptual relationships between odorants, even without explicit training for this task.

This figure visualizes how different models represent odorants in a two-dimensional space. The layout is inspired by a previous study. The plot shows the first two principal components of the odorant representations generated by MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM. The visualization highlights how MoLFormer, even without explicit training on perceptual data, manages to capture the relationships between different odorant categories.

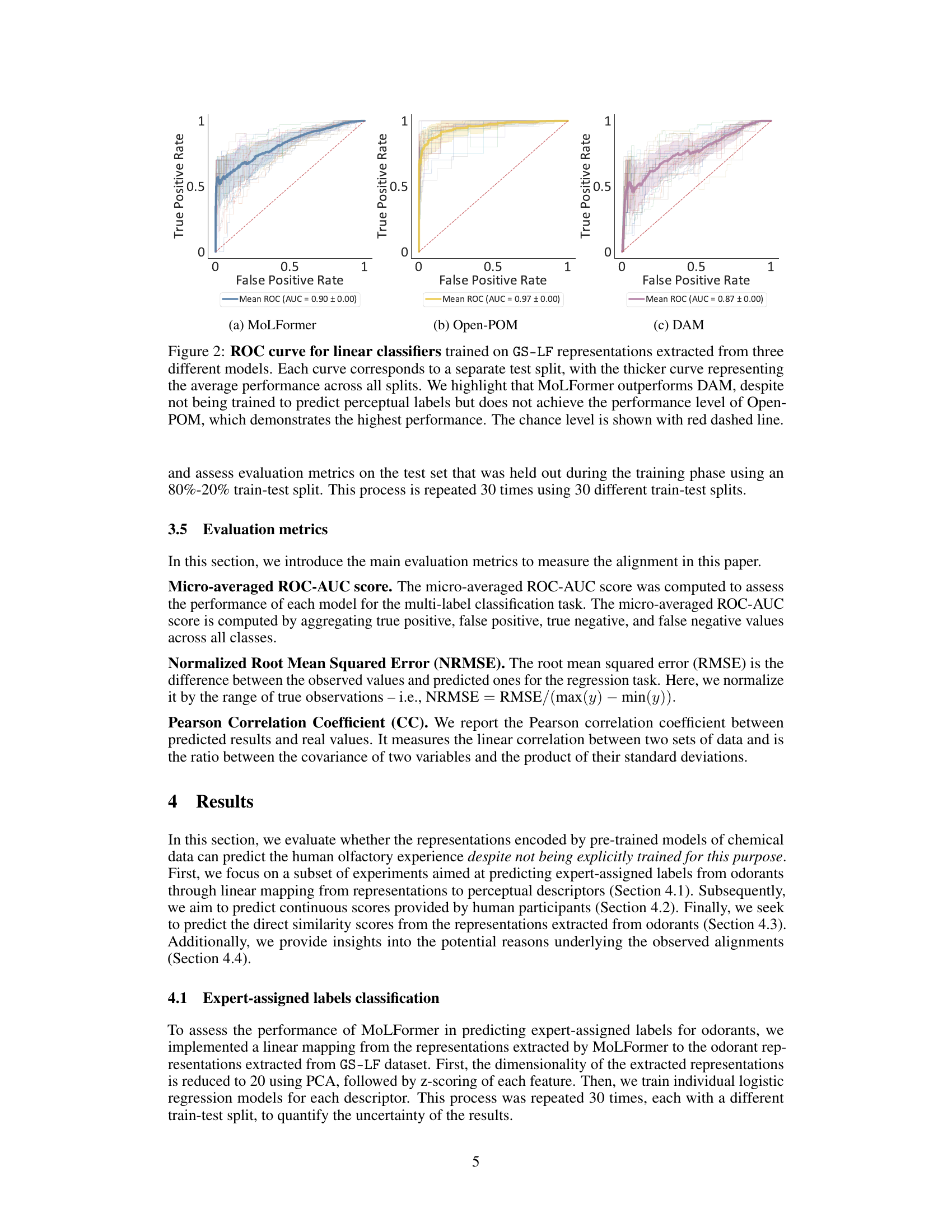

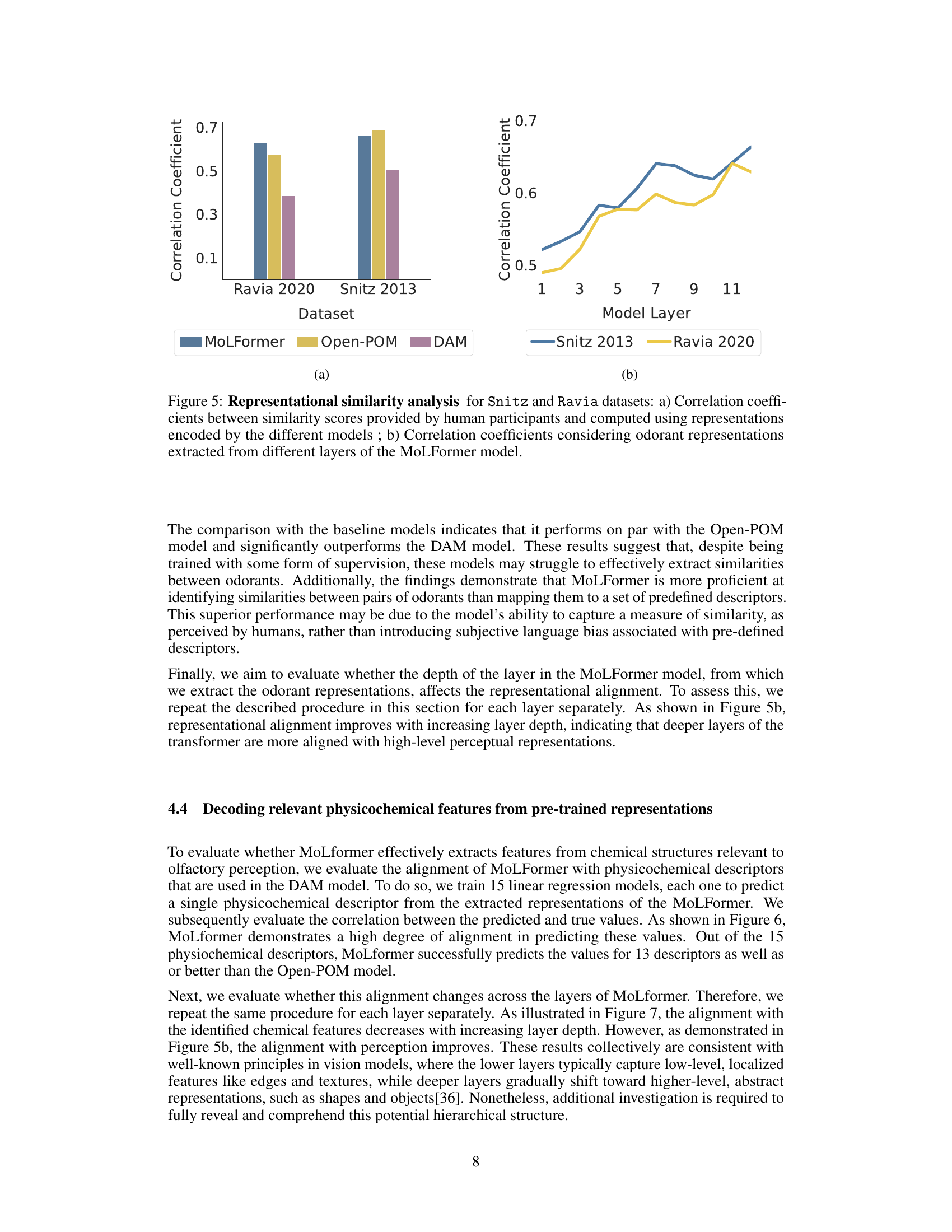

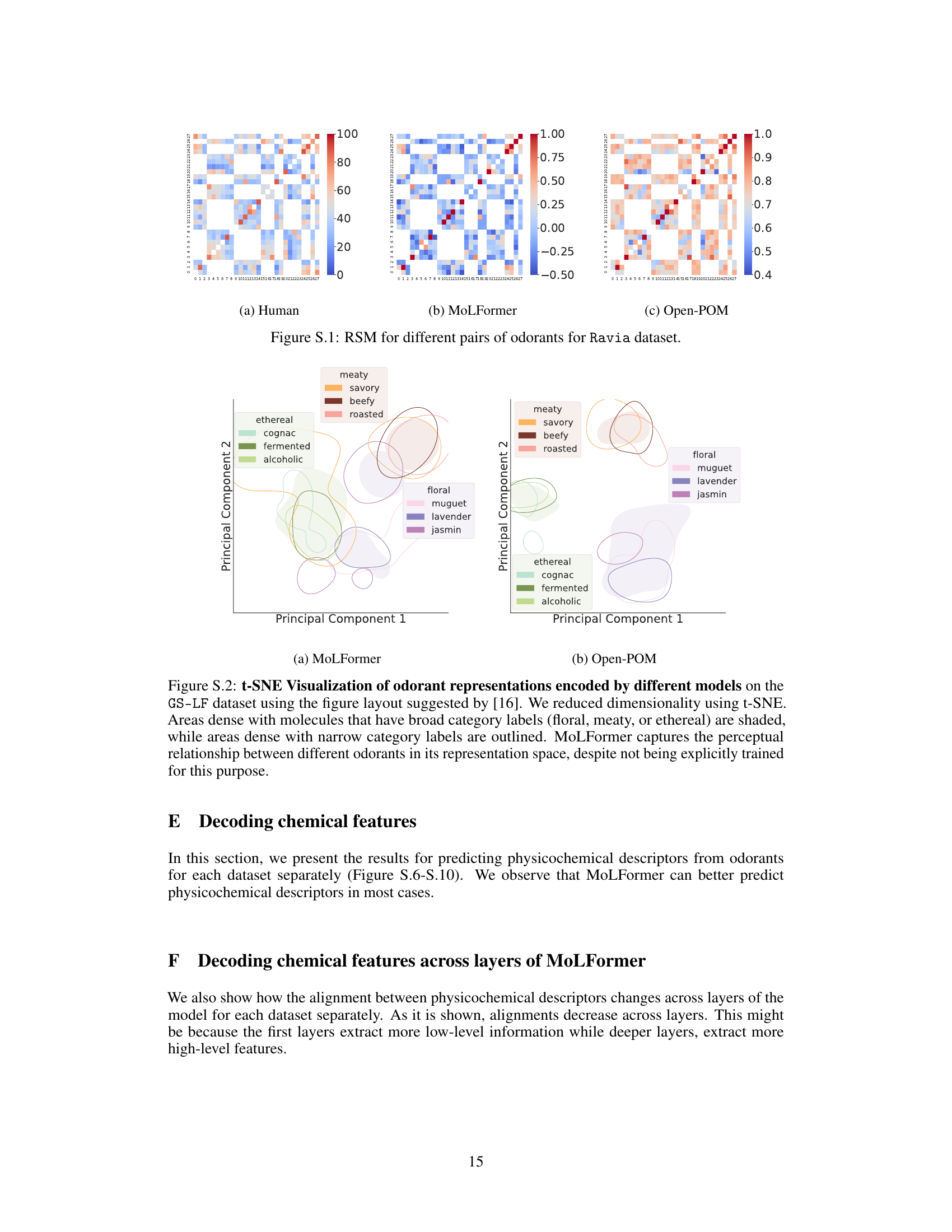

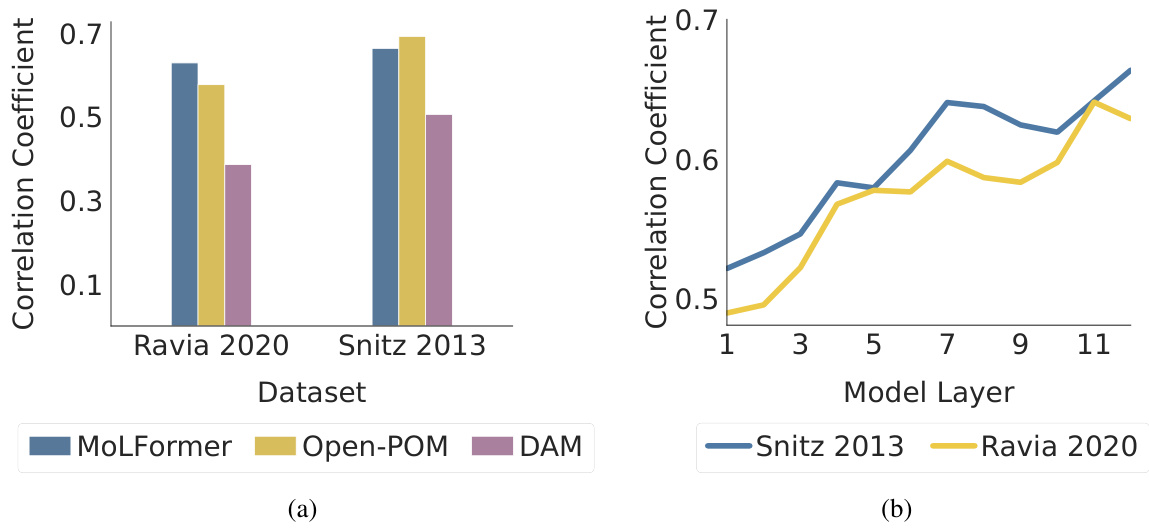

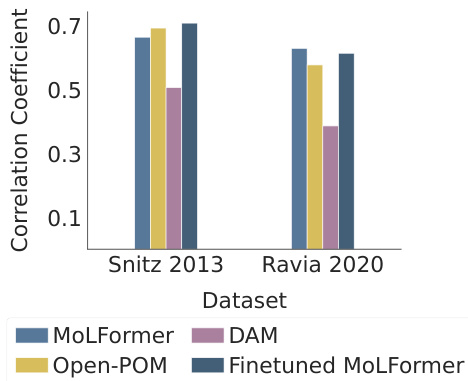

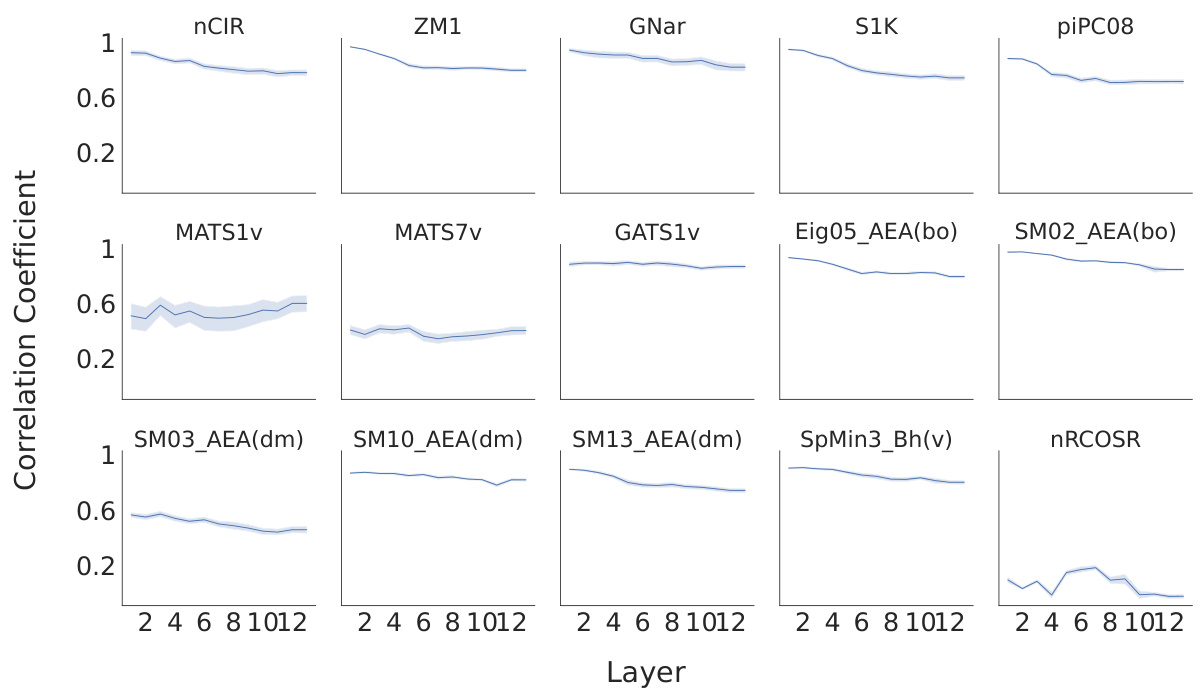

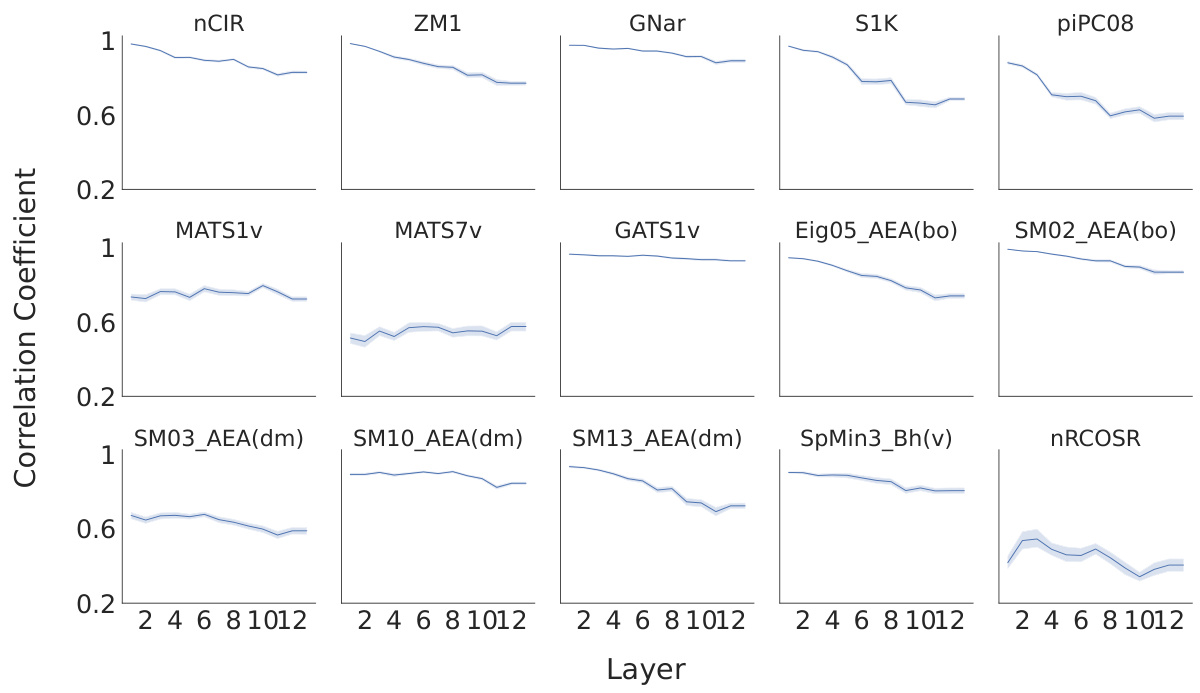

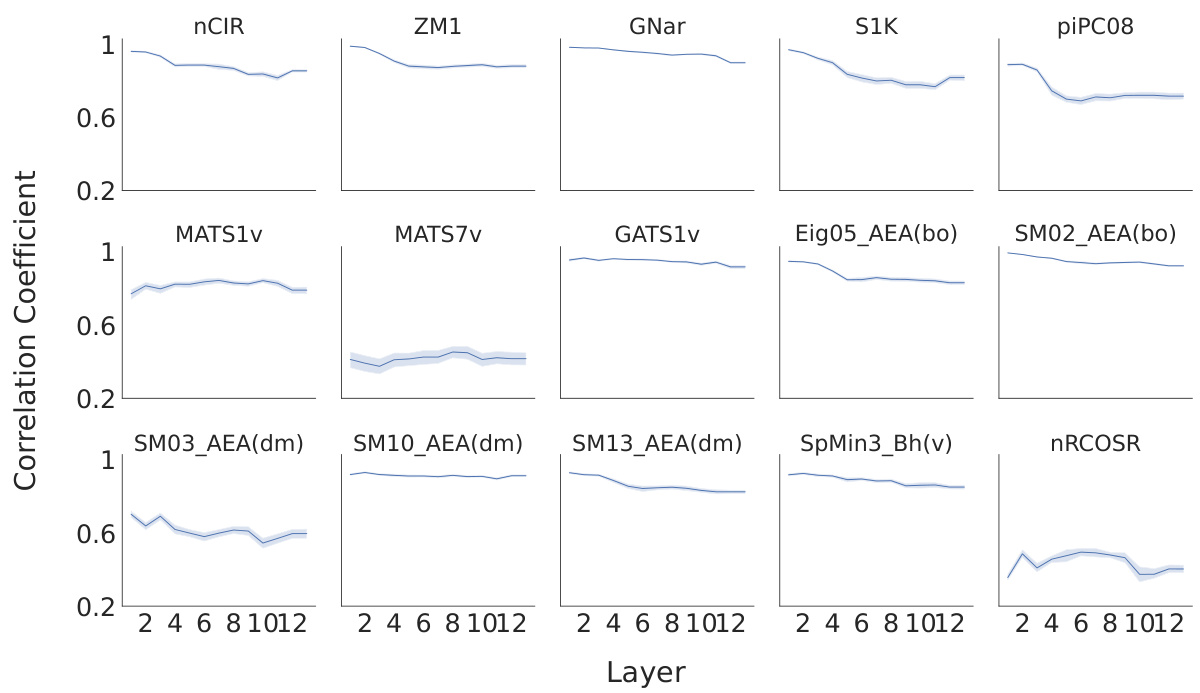

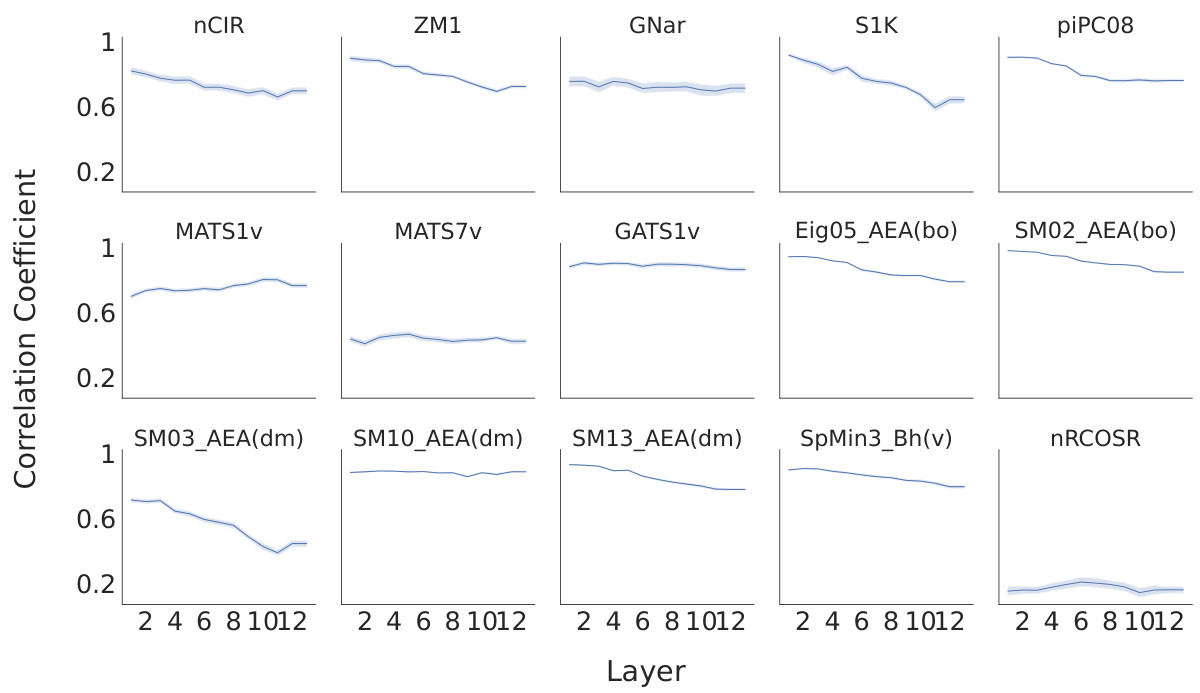

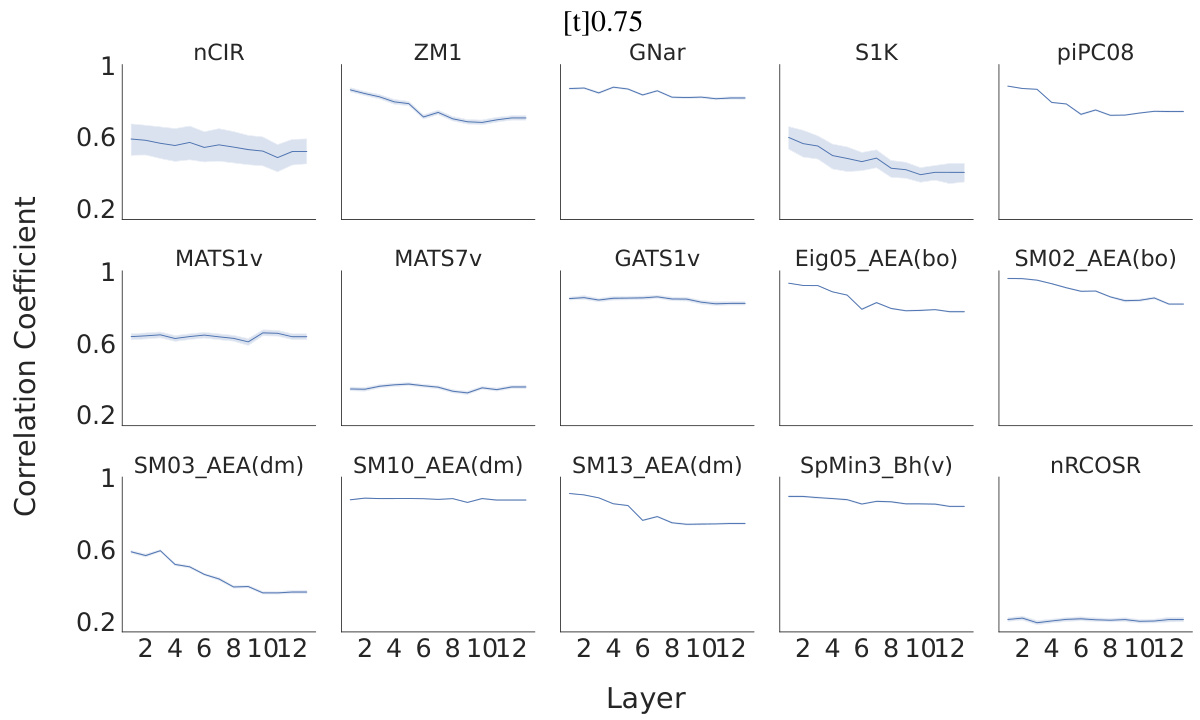

This figure presents a representational similarity analysis (RSA) to evaluate the alignment between human perception and the model’s representations. Panel (a) compares the correlation coefficients between human perceptual similarity ratings and similarity scores computed from the odorant representations extracted from three models: MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM, using two different datasets (Snitz 2013 and Ravia 2020). Panel (b) shows how the correlation between human perceptual similarity and MoLFormer’s representation changes across different layers of the MoLFormer model, for each of the two datasets.

This figure visualizes how different models represent odorants using the first two principal components. It shows that MoLFormer, despite not being trained on perceptual data, can capture the perceptual relationships between odorants, similar to Open-POM, which was trained with supervision.

This figure visualizes how different models represent odorants in a 2D space using principal component analysis (PCA). It compares the representations from MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM, highlighting that MoLFormer captures the perceptual relationships between odorants, despite lacking explicit training for this.

This figure displays the results of a representational similarity analysis (RSA) comparing human olfactory perception with the odorant representations generated by various models, including MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM. Panel (a) shows the correlation between human-rated odor similarity scores and model-generated similarity scores for the Snitz and Ravia datasets. Panel (b) specifically examines the correlation for MoLFormer, assessing the effect of different layers within the model on the results.

This figure visualizes how different models represent odorants in a 2D space using principal component analysis. It compares MoLFormer and Open-POM, highlighting MoLFormer’s ability to capture perceptual relationships between odorants even without explicit training for this.

This ROC curve compares the performance of three different models (MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM) in predicting expert-assigned odorant labels from the GS-LF dataset. Each thin line represents a single train-test split, showing the variability in performance. The thicker line shows the average ROC curve across all splits. MoLFormer outperforms DAM, despite not being trained for this task, but Open-POM achieves the best performance, highlighting the benefit of supervised training.

This figure visualizes how different models represent odorants. It shows the first two principal components of the odorant representations from MoLFormer and Open-POM models, highlighting how each model captures the perceptual relationships between odorants, even though MoLFormer wasn’t explicitly trained for this purpose.

This figure shows the results of a representational similarity analysis (RSA) comparing human perceptual similarity judgments with those predicted by different models (MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM) for two datasets: Snitz 2013 and Ravia 2020. Panel (a) presents the correlation coefficients between human ratings and model predictions, demonstrating that MoLFormer and Open-POM achieve high alignment with human perceptions. Panel (b) shows how this alignment varies across different layers of the MoLFormer model, indicating that deeper layers show a stronger alignment with human judgments.

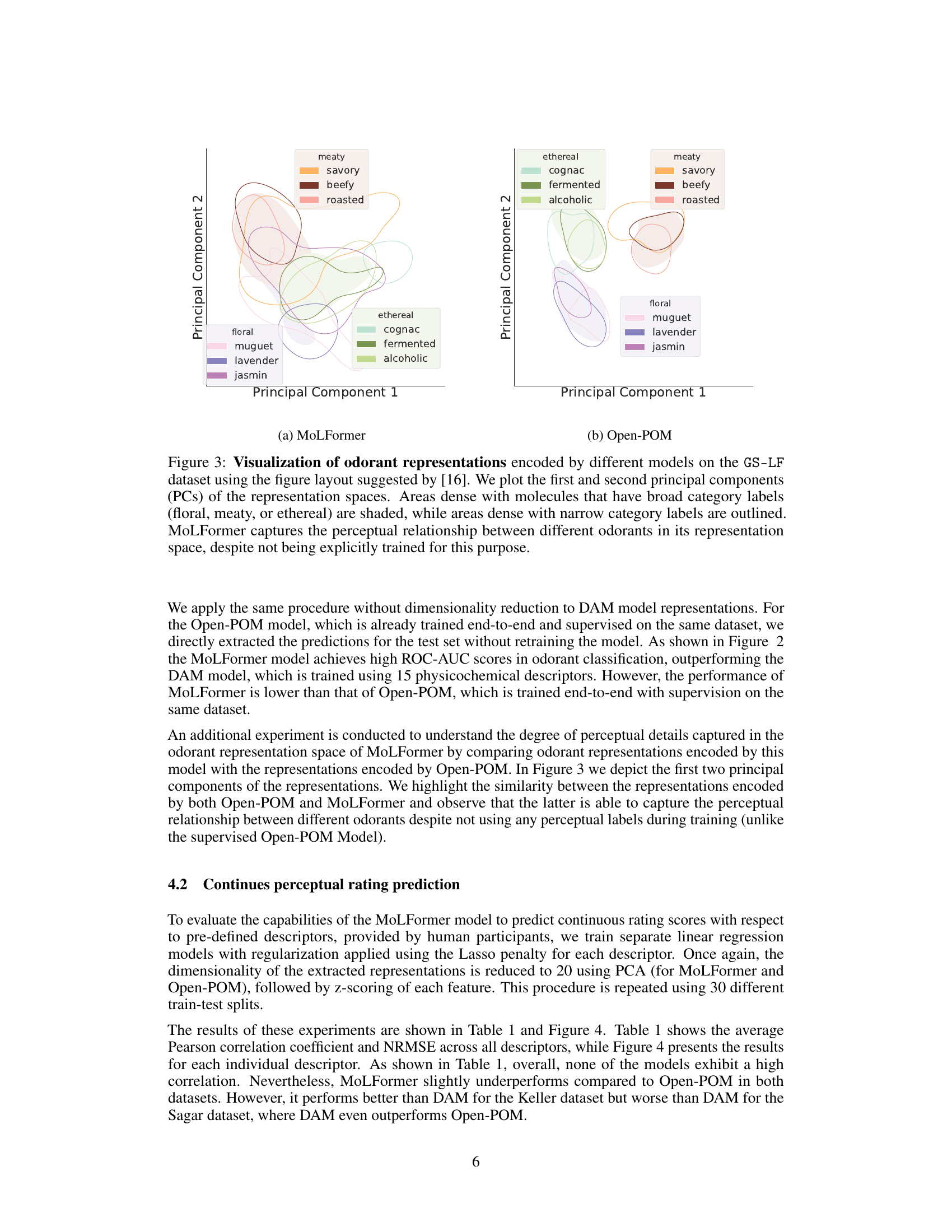

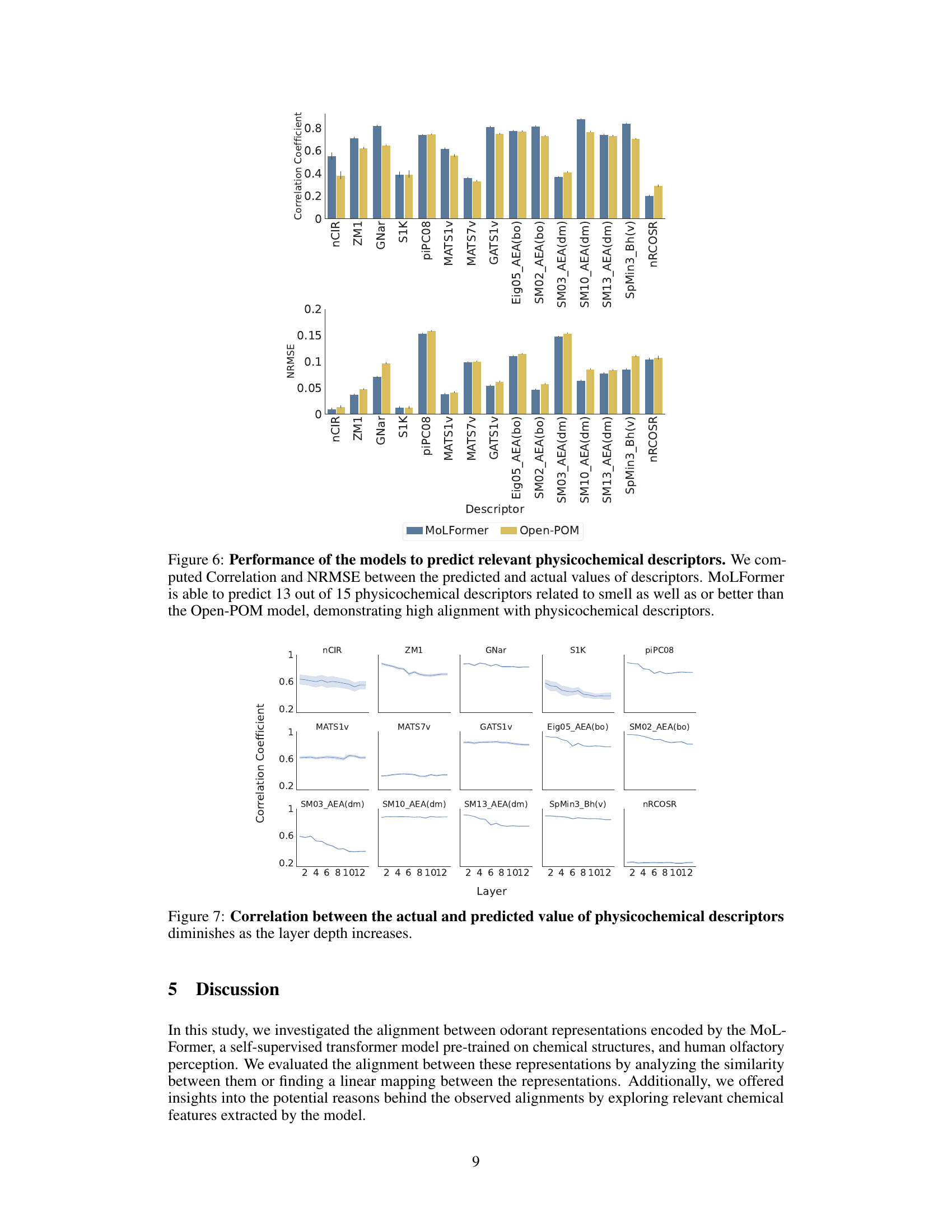

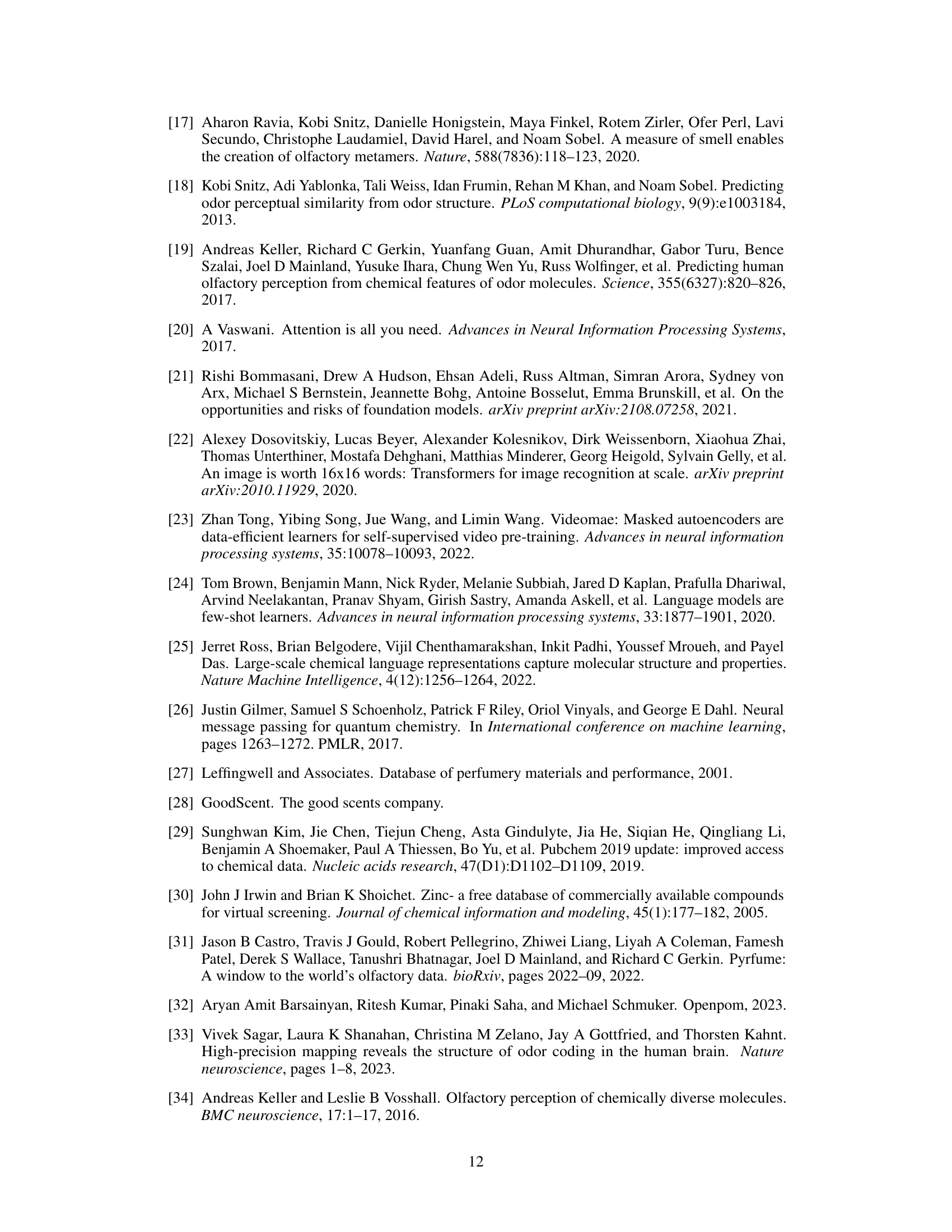

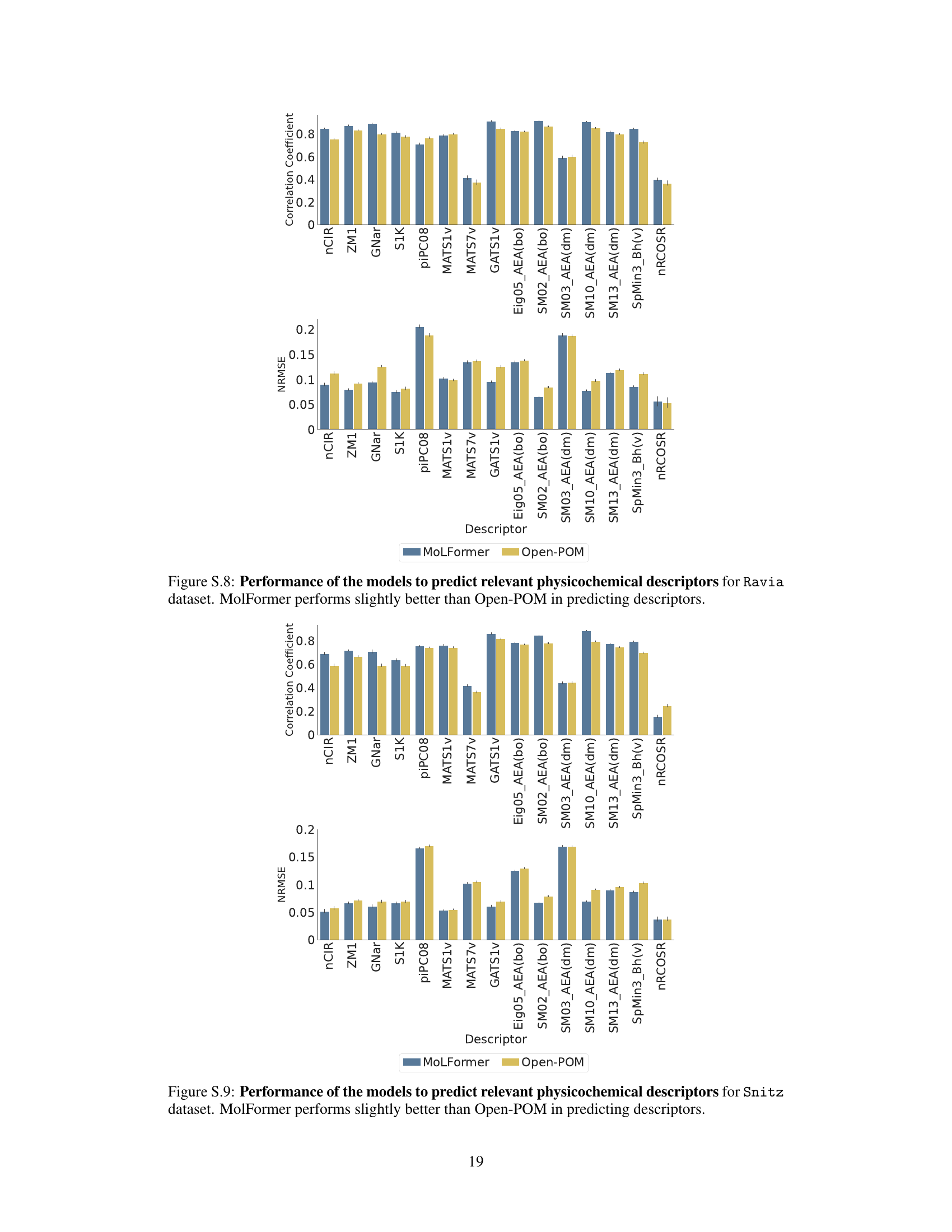

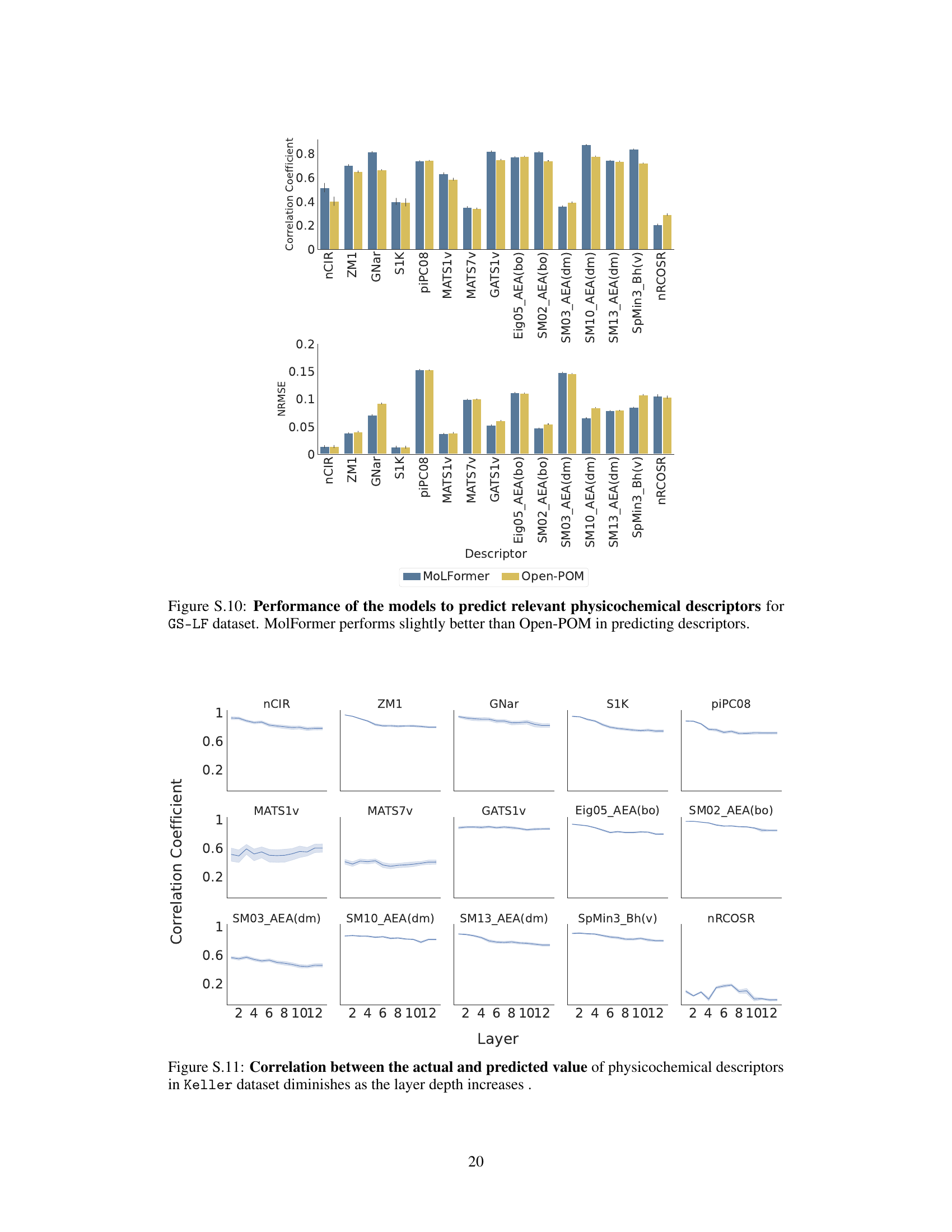

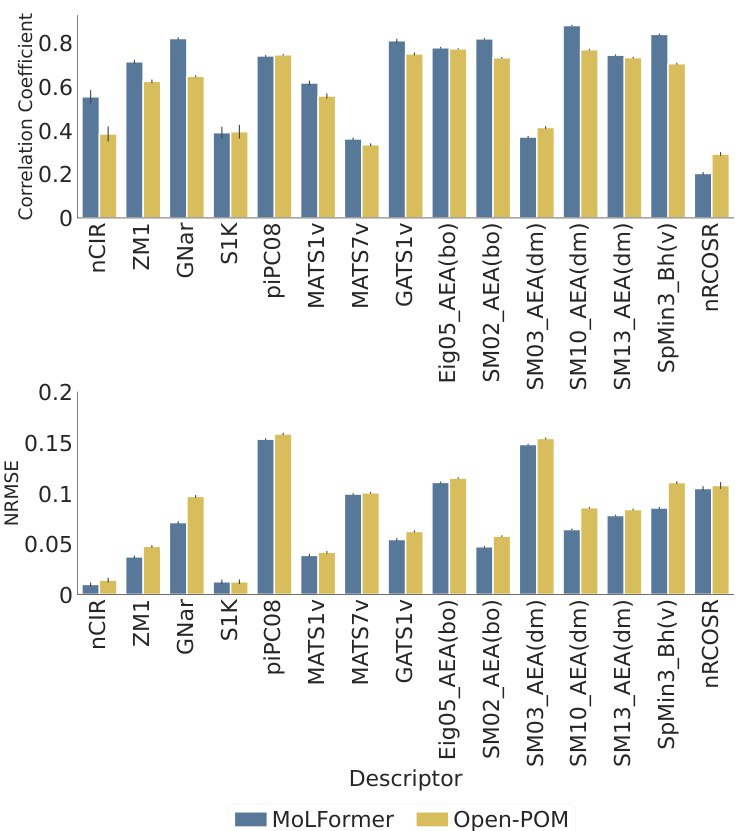

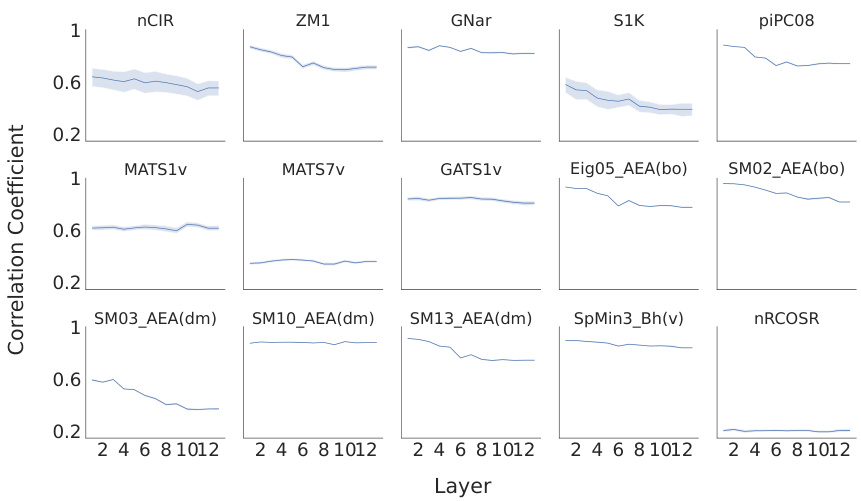

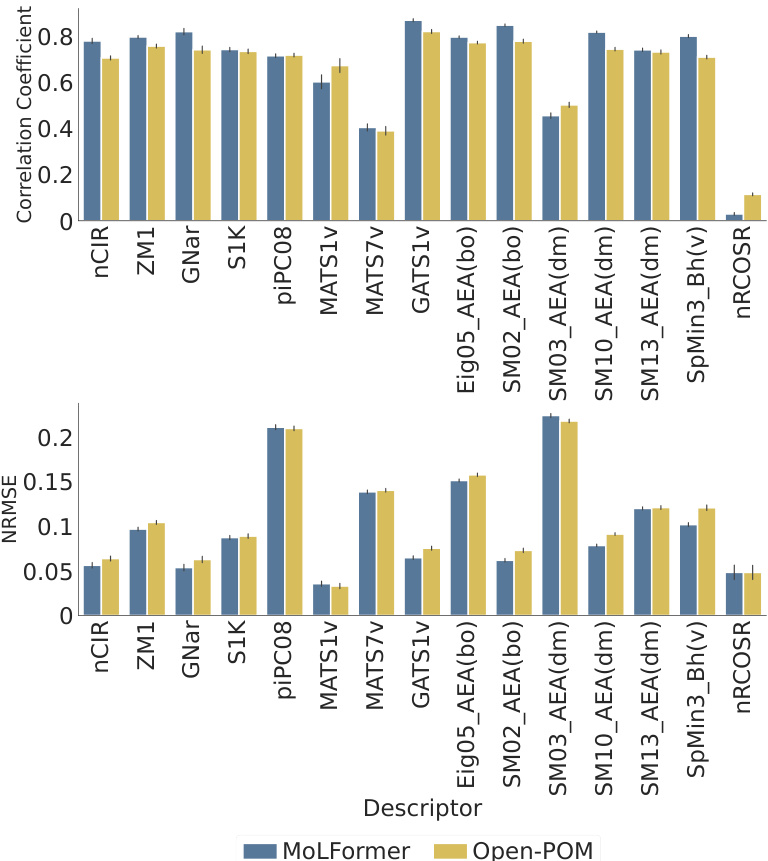

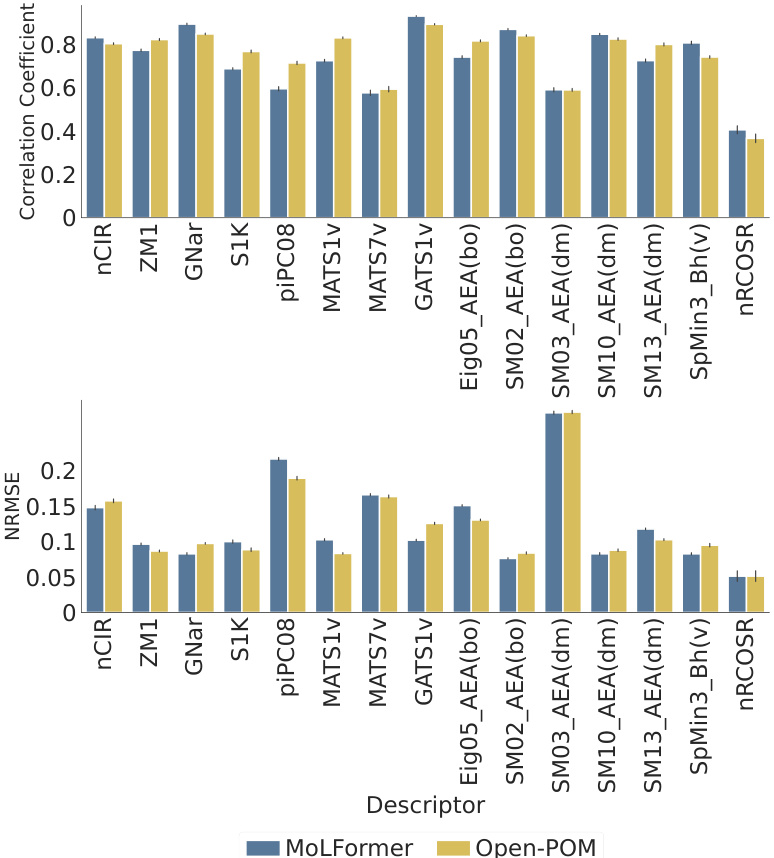

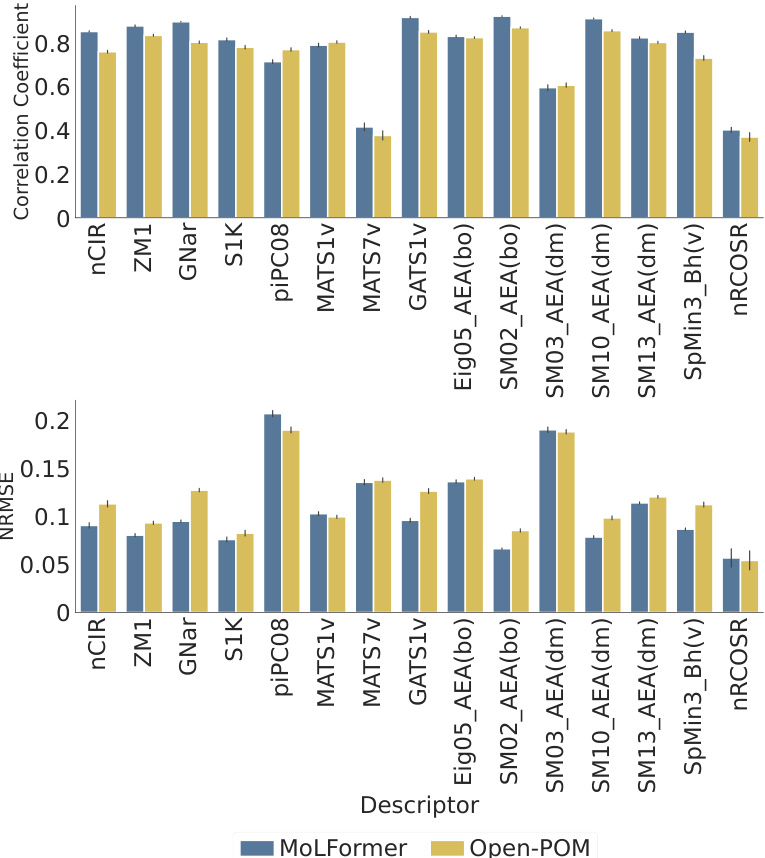

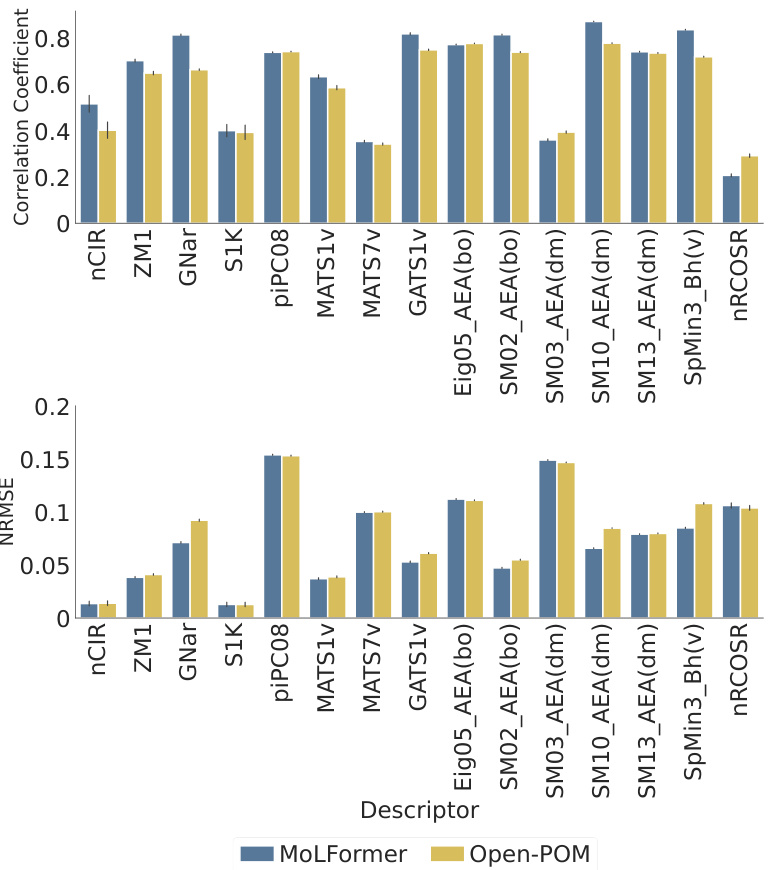

This figure shows the performance comparison between MoLFormer and Open-POM models in predicting 15 physicochemical descriptors relevant to odor perception using the Keller dataset. For each descriptor, it displays both the Pearson correlation coefficient (a measure of the linear relationship between predicted and actual values) and the Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE, which quantifies prediction accuracy). The results show that MoLFormer generally performs slightly better than Open-POM across most descriptors, indicating a stronger ability to capture the physicochemical features relevant to odor perception.

The figure displays the performance comparison between MoLFormer and Open-POM models in predicting 15 physicochemical descriptors for the Keller dataset. For each descriptor, two bars represent the performance metrics (correlation coefficient and NRMSE) of each model. The results suggest that MoLFormer generally outperforms Open-POM in predicting most of the physicochemical descriptors, although the difference isn’t always substantial.

This figure displays ROC curves for three different models (MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM) trained on the GS-LF dataset to predict expert-assigned odor labels. Each curve represents a different test split, with the thicker line representing the average performance across all splits. The results show MoLFormer outperforming DAM but falling short of Open-POM’s performance, indicating the potential of pre-trained models for olfactory perception prediction.

This figure shows the performance comparison between MoLFormer and Open-POM models in predicting 15 physicochemical descriptors related to odor perception for the Keller dataset. The performance is evaluated using Pearson correlation coefficient and NRMSE. The bar chart visually represents the correlation and NRMSE for each descriptor for both models, facilitating a direct comparison of their predictive capabilities. The results indicate that MoLFormer generally performs slightly better than Open-POM in predicting these physicochemical descriptors, demonstrating its ability to capture relevant chemical features.

This figure displays the performance of MoLFormer and Open-POM models in predicting 15 physicochemical descriptors relevant to olfaction for the Keller dataset. It shows the Pearson correlation coefficient and the Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) for each descriptor, indicating how well each model predicts the descriptor’s value. The results suggest MoLFormer performs slightly better overall than Open-POM.

This figure visualizes how different models represent odorants in a 2D space using the first two principal components. It shows that MoLFormer, despite not being trained for this, captures the perceptual relationship between odorants, similar to the supervised Open-POM model, but better than the DAM model. The visualization highlights the clustering of odorants based on their broad and narrow perceptual categories.

This figure visualizes how different models represent odorants in a two-dimensional space using principal component analysis (PCA). The models compared are MoLFormer and Open-POM. The visualization shows how odorants cluster according to their perceptual properties (e.g., floral, meaty, ethereal). Importantly, MoLFormer, despite not being trained on perceptual labels, still captures perceptual relationships, demonstrating its ability to learn meaningful representations of odorants.

This figure visualizes the odorant representations from three different models (MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM) using the first two principal components of the representation spaces. It highlights how MoLFormer, despite lacking explicit training for this, manages to capture the perceptual relationships between different odorants, as evidenced by the clustering of molecules with similar perceptual labels (floral, meaty, ethereal). The figure provides visual evidence supporting the claim that MoLFormer encodes representations aligned with human olfactory perception.

This figure visualizes the odorant representations generated by MoLFormer and Open-POM models trained on the GS-LF dataset. It uses principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensionality of the data to two dimensions, allowing for visualization in a 2D scatter plot. The plot shows how similar odorants cluster together based on their representation. The figure highlights MoLFormer’s ability to capture perceptual relationships between odorants, even without explicit training on such relationships.

This figure visualizes odorant representations from three different models (MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM) on the GS-LF dataset using principal component analysis (PCA). It shows how the models represent odorants in a 2D space, highlighting clusters of odorants with similar perceptual properties. The visualization demonstrates that MoLFormer, despite not being trained with perceptual labels, still captures the relationship between odorants, suggesting an inherent alignment with human olfactory perception.

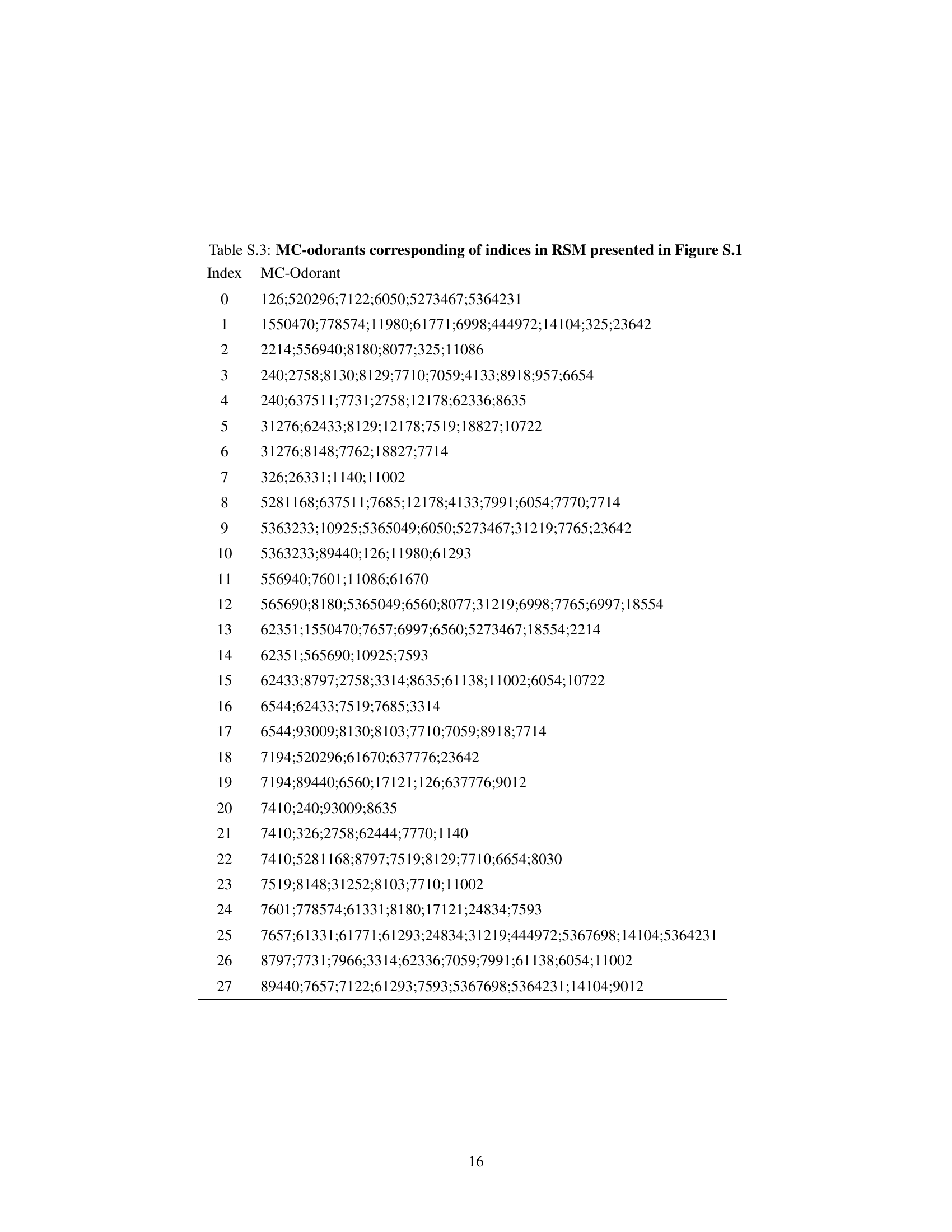

More on tables

This table presents the performance of three different models (MoLFormer, Open-POM, and DAM) in predicting continuous perceptual ratings of odorants. The performance is evaluated using two metrics: Pearson correlation coefficient (CC) and normalized root mean squared error (NRMSE). The table shows the average performance across all descriptors for two datasets (Keller and Sagar). It highlights the relative performance of each model on each dataset.

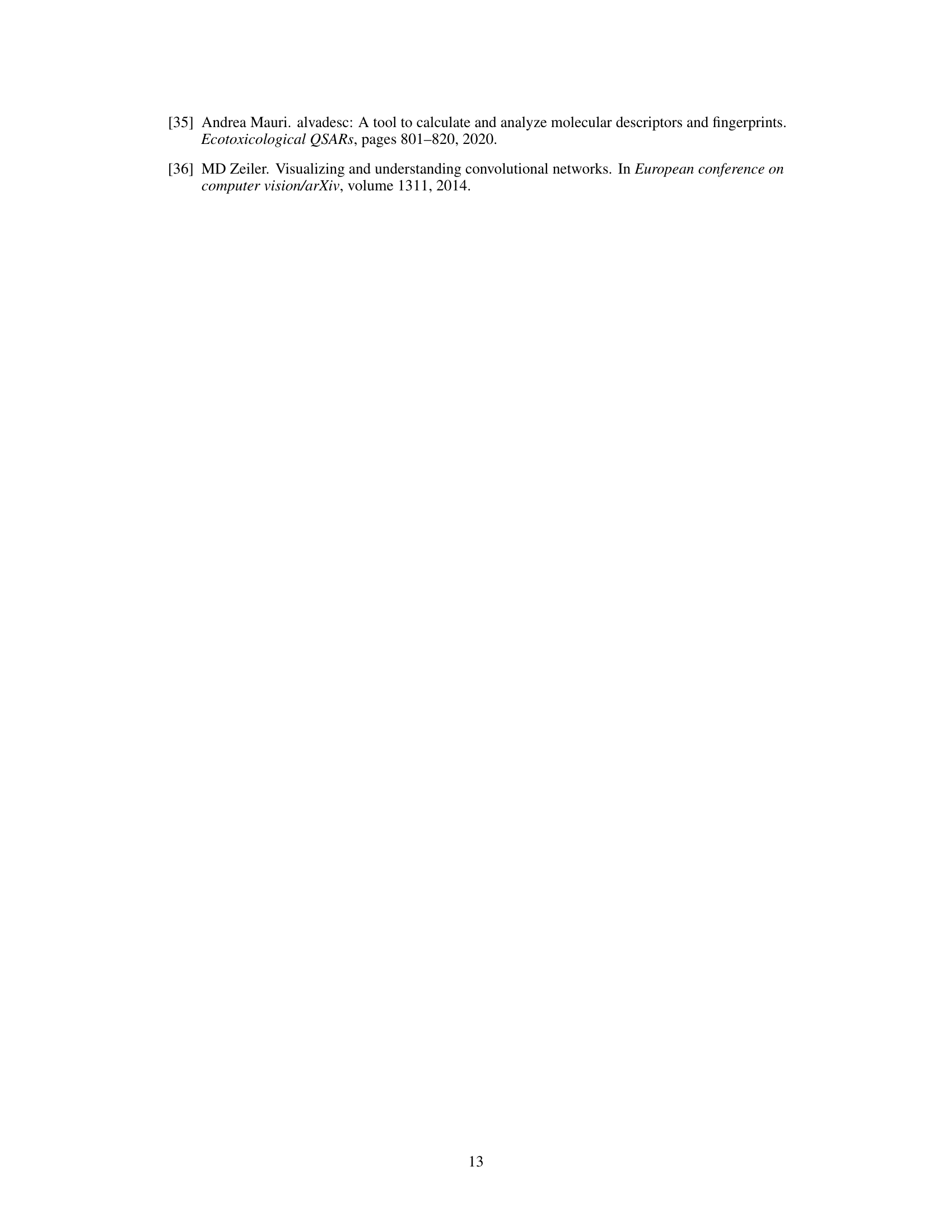

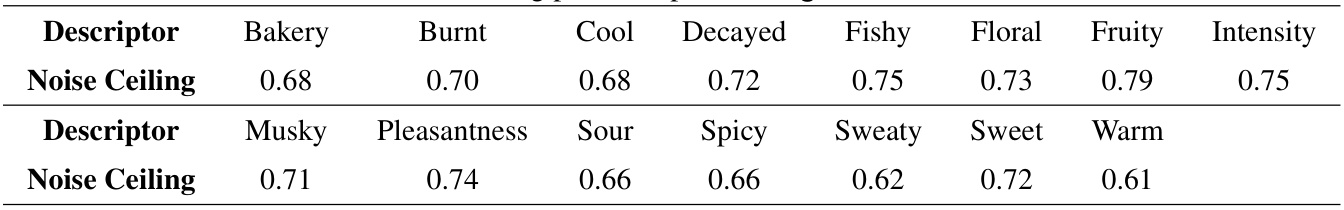

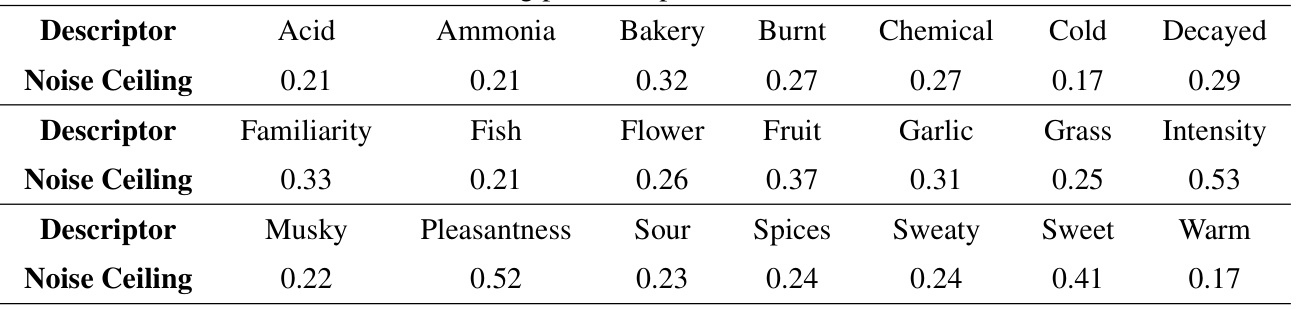

This table presents the noise ceiling for each descriptor in the Keller dataset. The noise ceiling represents the upper limit of performance for any model predicting olfactory perception based on these ratings, reflecting the inherent variability in human perception. Lower values indicate less noise and more potential for models to improve prediction accuracy.

Full paper#