↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current machine unlearning methods face challenges in balancing privacy, accuracy, and efficiency, particularly when handling frequent data removal requests. Existing methods often require complete model retraining, which is computationally expensive. Also, many approaches only support convex optimization problems.

This paper introduces Langevin unlearning, a new approach to machine unlearning that utilizes noisy gradient descent. The key innovation is its ability to provide strong privacy guarantees using Renyi Differential Privacy, while maintaining computational efficiency and handling both convex and non-convex problems effectively. The authors demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method through theoretical analysis and empirical evaluations on several benchmark datasets, showing its superior privacy-utility-complexity trade-off compared to existing methods. This technique is particularly relevant to addressing the increasing demands for data privacy compliance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents Langevin unlearning, a novel framework for machine unlearning that offers privacy guarantees and is applicable to both convex and non-convex problems. This addresses a critical limitation of existing methods and opens new avenues for research in privacy-preserving machine learning, particularly in the context of the growing importance of data privacy regulations.

Visual Insights#

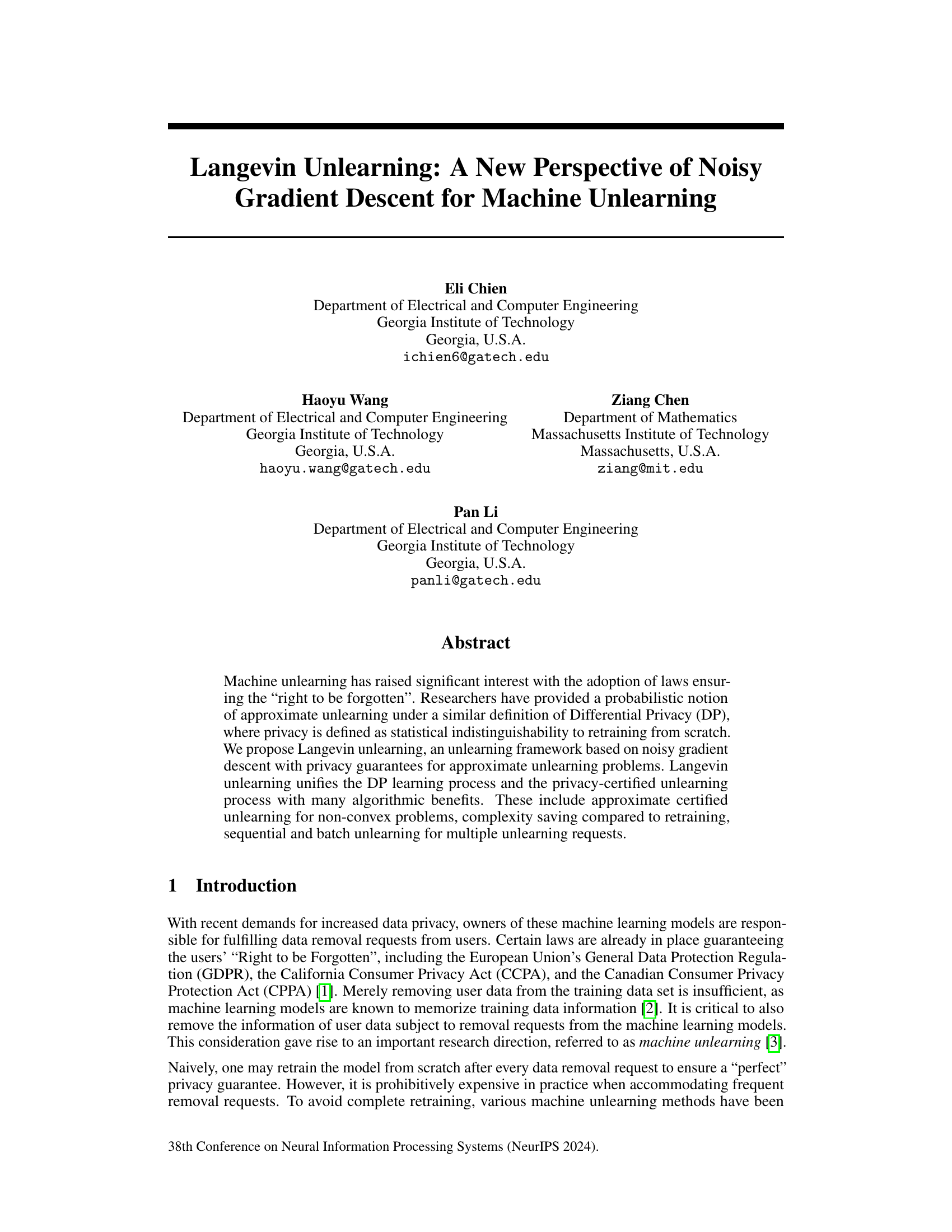

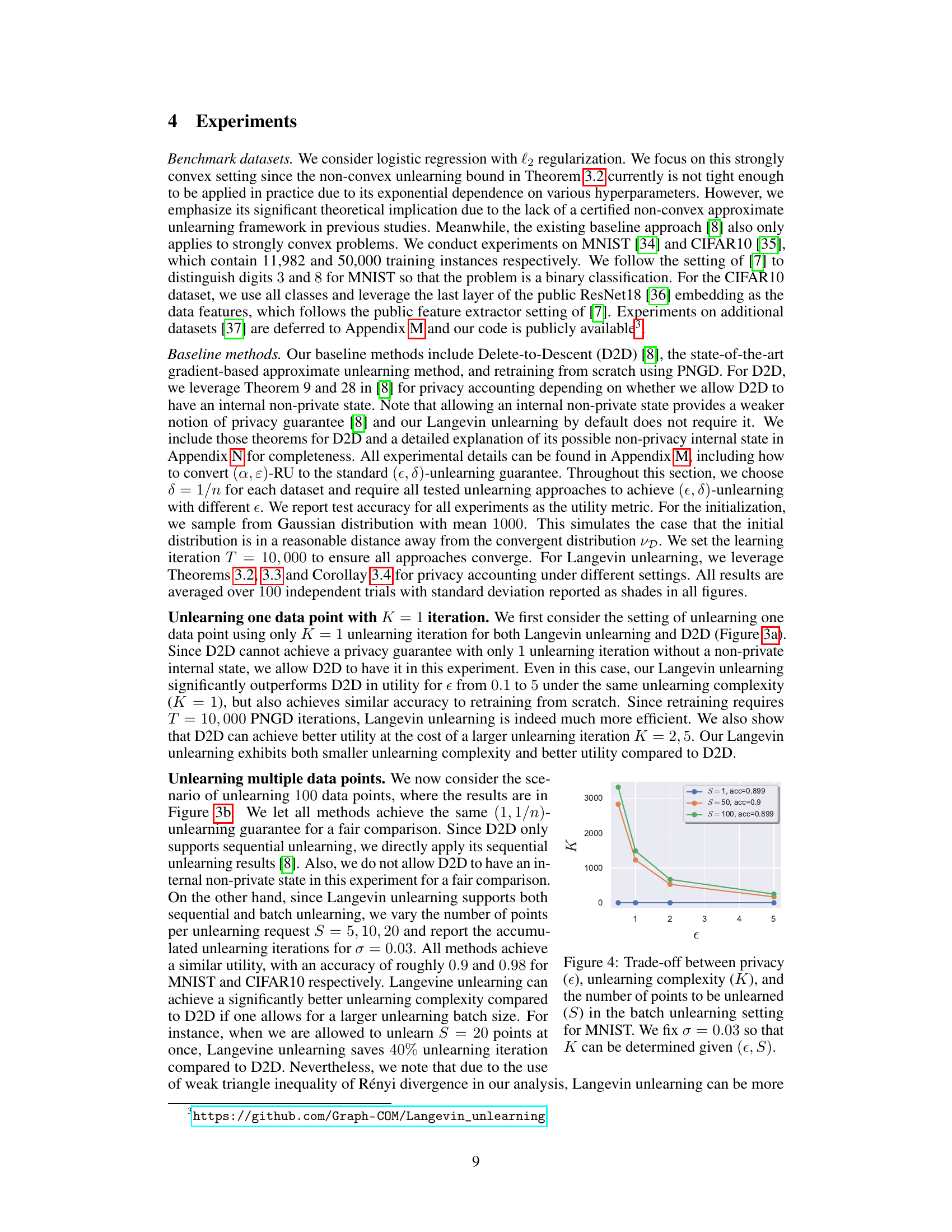

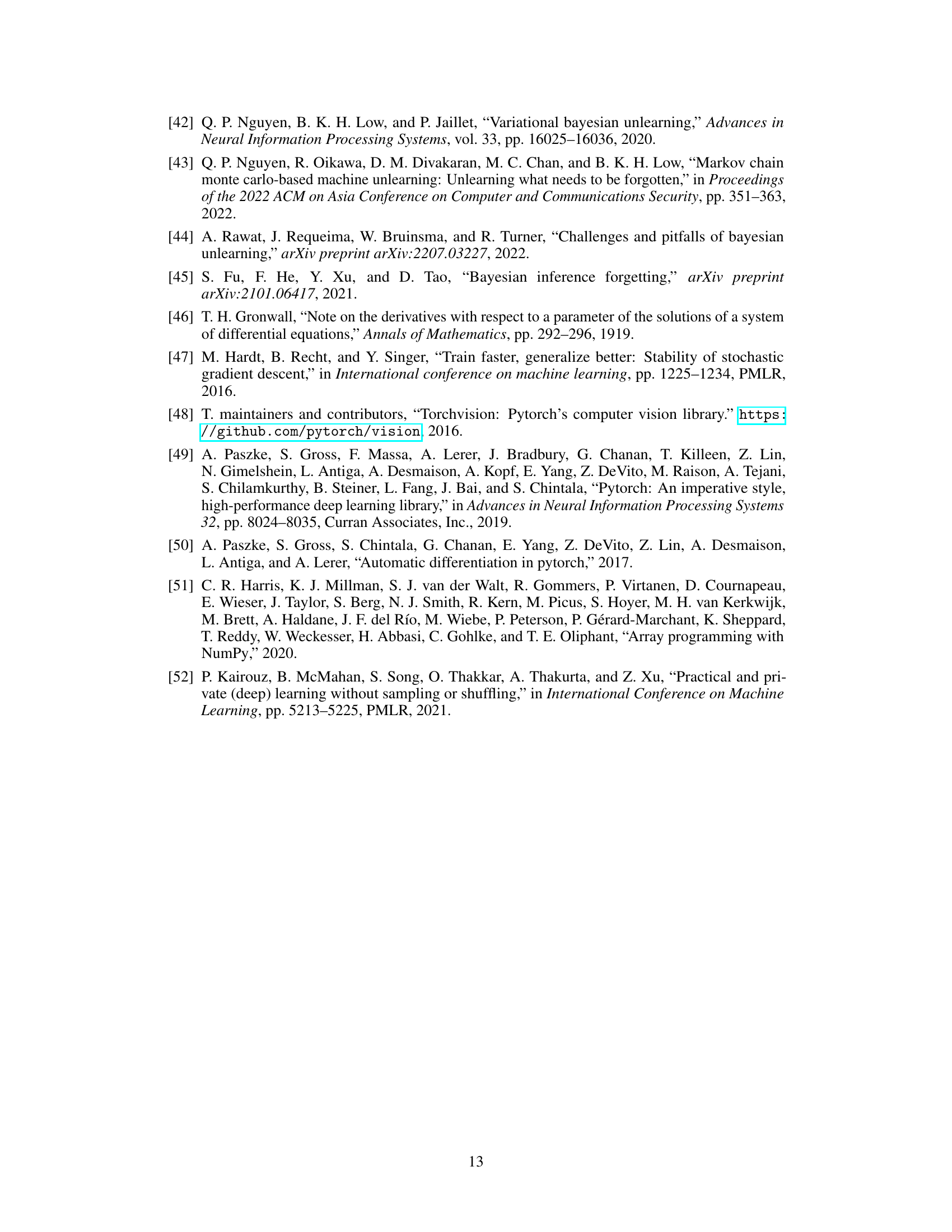

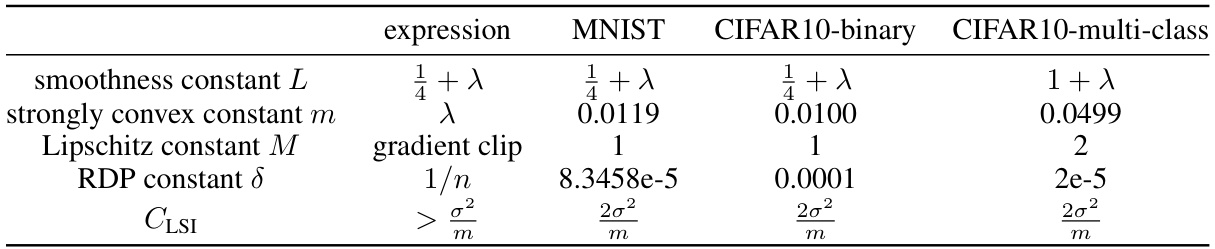

This figure provides a geometric interpretation of the relationship between the learning and unlearning processes within the context of differential privacy. The left panel illustrates how the stronger initial privacy guarantee from the learning process (smaller epsilon naught) results in a smaller polyhedron, making the unlearning process easier. The right panel shows how the learning process leads to privacy erosion (worse privacy as iterations increase) while the subsequent unlearning process leads to privacy recuperation (improved privacy as iterations increase). This visualization highlights the core idea of Langevin unlearning, showcasing how the unlearning process can effectively recover privacy lost during the learning phase.

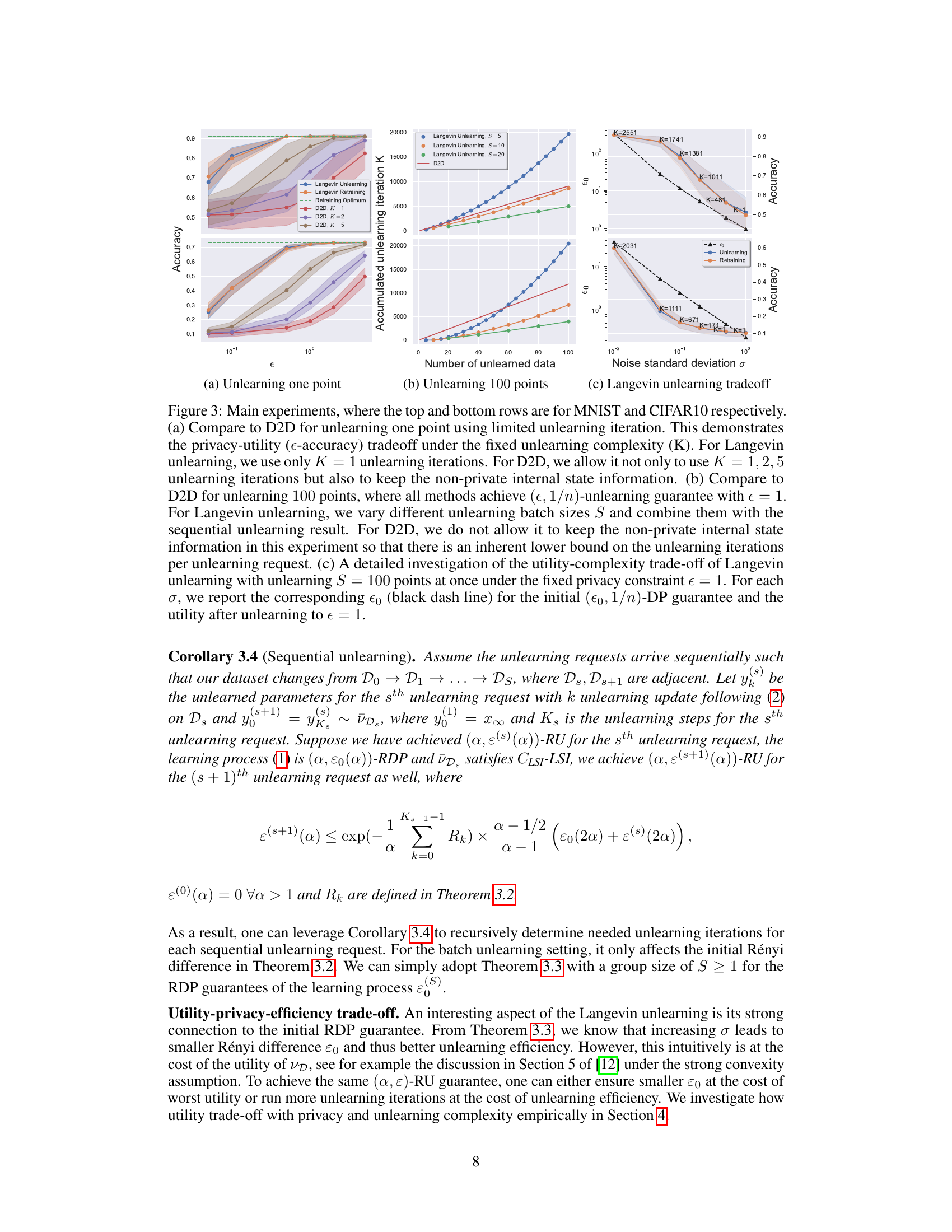

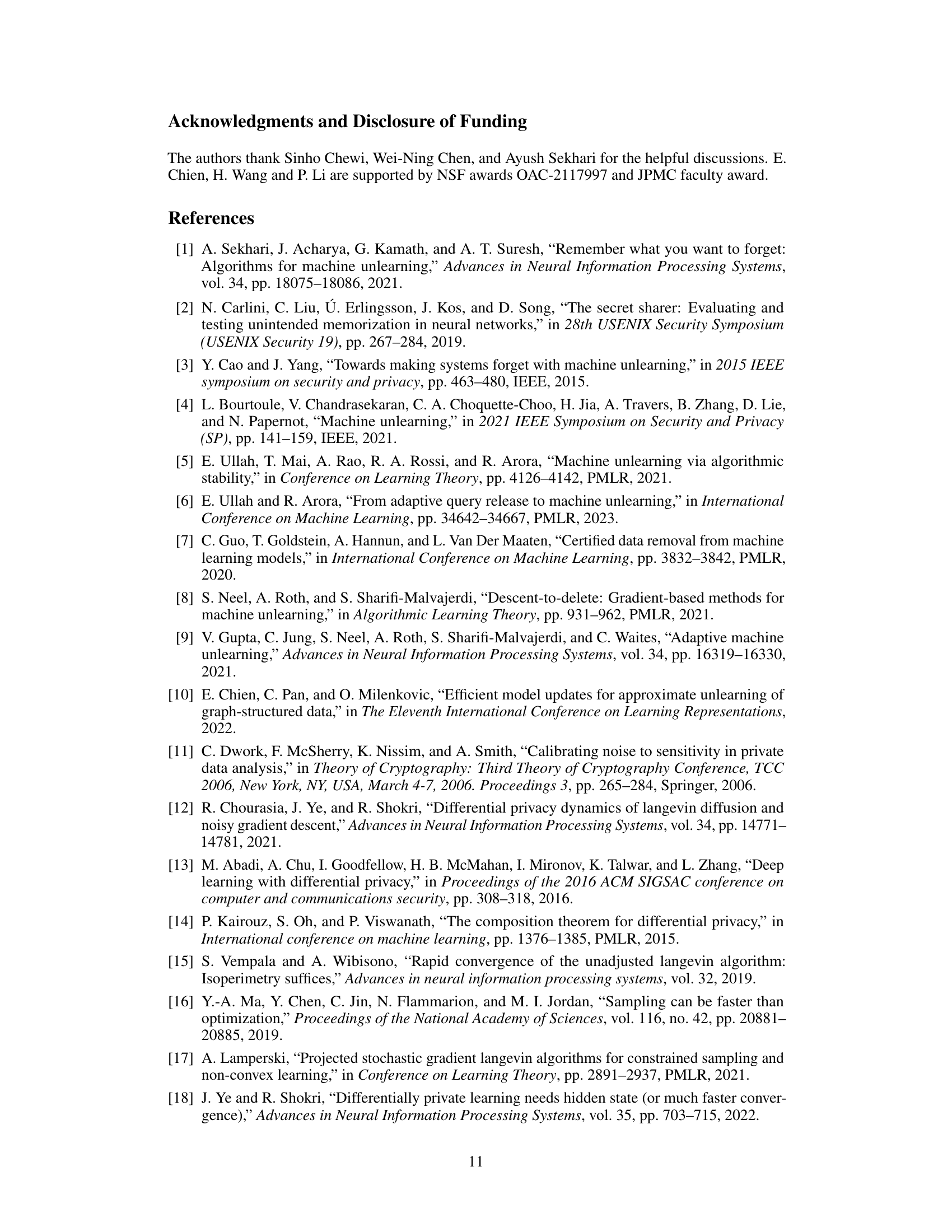

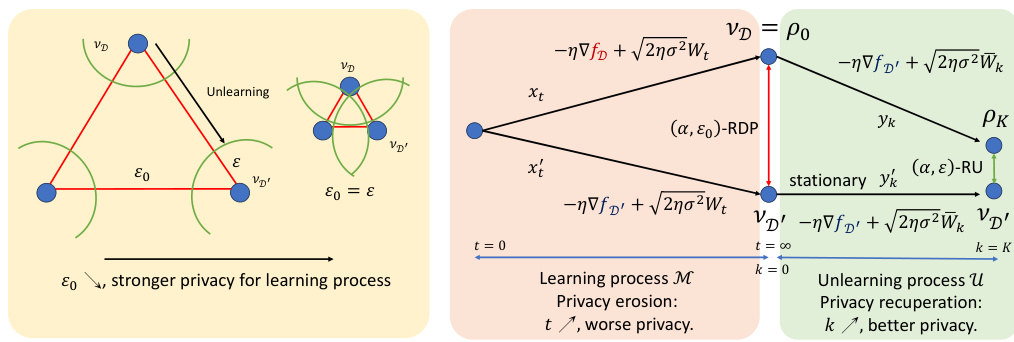

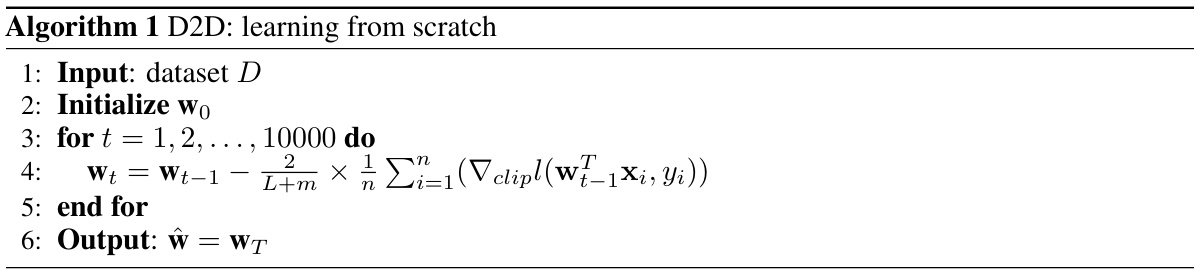

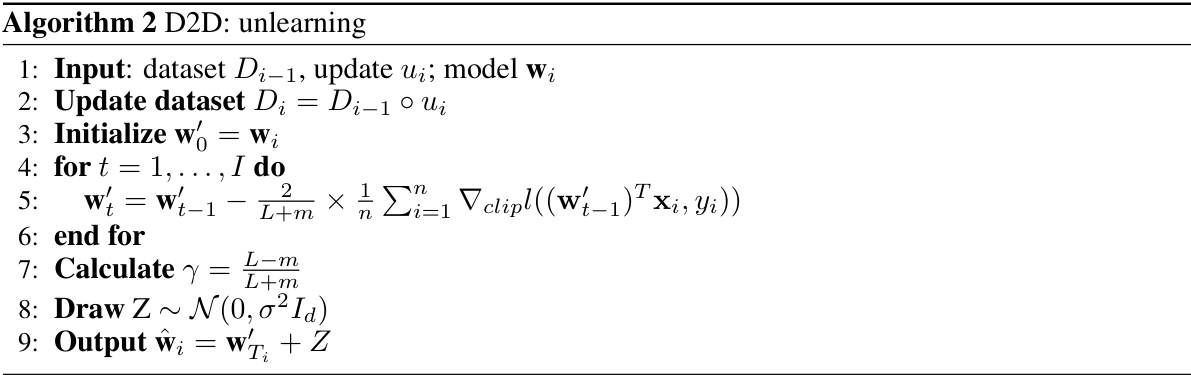

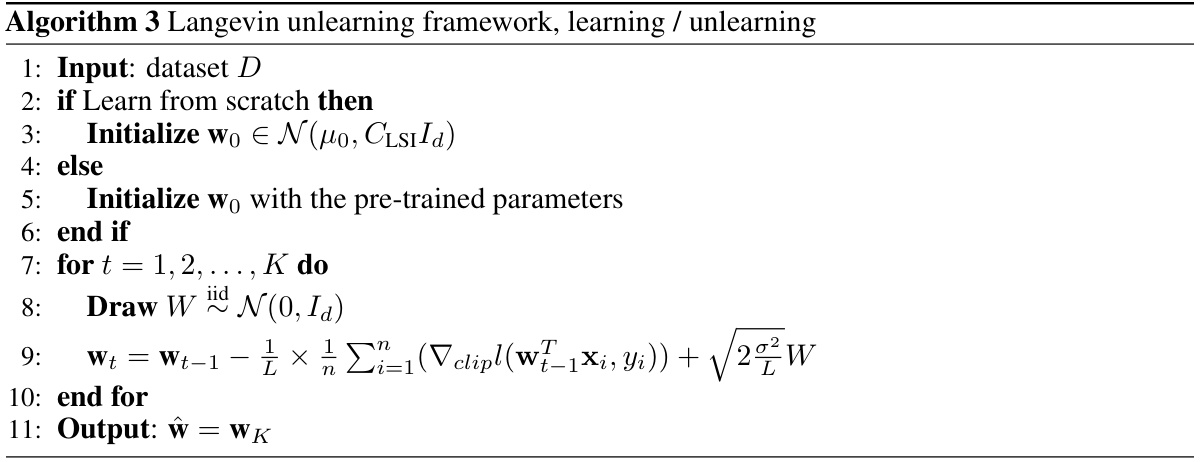

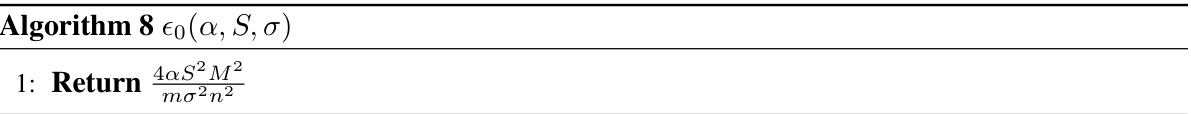

This table lists the values of hyperparameters used in the experiments, including the smoothness constant (L), strongly convex constant (m), Lipschitz constant (M), RDP constant (δ), and the lower bound of the LSI constant (CLSI). These constants are calculated for the MNIST, CIFAR10-binary, and CIFAR10-multi-class datasets.

In-depth insights#

Langevin Unlearning#

Langevin Unlearning presents a novel approach to machine unlearning by framing it as a noisy gradient descent process. This technique is particularly interesting because it unifies the learning and unlearning stages, offering a more efficient and potentially more private method than retraining from scratch. The core idea leverages the stationary distribution of the Langevin dynamics to guarantee approximate unlearning under differential privacy. The framework’s strength lies in its applicability to non-convex problems, unlike previous methods that usually depend on strong convexity assumptions, making it more suitable for complex machine learning tasks. Furthermore, it demonstrates advantages in computational efficiency and handling of sequential and batch unlearning requests, indicating potential to scale well in real-world scenarios. However, tightening the theoretical bounds for non-convex scenarios and addressing potential issues with the LSI constant remain as crucial areas for future research.

Noisy Gradient Descent#

Noisy gradient descent is a fundamental concept in the field of optimization and machine learning, particularly crucial when addressing issues related to privacy and robustness. The core idea involves adding noise to the gradient updates during the optimization process. This injection of noise helps prevent overfitting and enhances the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. In the context of privacy-preserving machine learning, differential privacy, this technique guarantees that individual data points do not significantly influence the final model. The noise is carefully calibrated to maintain a balance between the accuracy of the model and the desired level of privacy. By incorporating noise, the algorithm becomes less sensitive to individual data points, making it more resilient to adversarial attacks and outliers. The level of noise added needs to be carefully tuned; too little noise might not provide sufficient regularization or privacy, while too much noise could hinder convergence and severely affect model accuracy. Different noise distributions and strategies for injecting noise have been proposed and analyzed in the literature, each with its own trade-offs. Ultimately, noisy gradient descent serves as a powerful tool for achieving both improved generalization and stronger privacy in machine learning models.

Privacy Recuperation#

The concept of “Privacy Recuperation” introduces a novel perspective on machine unlearning. It posits that the privacy loss incurred during the learning process can be mitigated, or even reversed, through a carefully designed unlearning process. This contrasts with the common understanding of privacy erosion, where each additional learning iteration degrades the model’s privacy. Privacy recuperation suggests that by strategically removing data points and fine-tuning the model using techniques like noisy gradient descent, we can regain privacy lost during training. This implies a dynamic interplay between learning and unlearning, where the initial stronger privacy guarantee during training influences the efficiency of the subsequent unlearning. Furthermore, the unlearning process itself can be designed to have privacy guarantees, creating a framework for privacy-preserving machine unlearning that’s computationally more efficient than retraining from scratch. This approach opens exciting possibilities for managing privacy in machine learning applications that involve frequent data removal requests.

Non-convex Unlearning#

The concept of “Non-convex Unlearning” presents a significant challenge in machine unlearning. Unlike convex scenarios where a single global optimum exists, non-convex optimization landscapes contain multiple local minima, making the process of removing a data point’s influence significantly more complex. Standard unlearning techniques often rely on the gradient or Hessian of the loss function, which can be unreliable in non-convex settings due to the presence of saddle points and flat regions. A naive retraining approach is computationally expensive. Developing effective unlearning strategies for non-convex models requires novel approaches that can handle the complexities of multiple local optima. This may involve techniques such as advanced optimization algorithms capable of escaping local minima or employing probabilistic methods that are robust to the inherent noise and uncertainty in non-convex environments. Theoretical guarantees are particularly challenging to obtain in the non-convex case, requiring a more sophisticated analysis of the algorithm’s behavior and potentially relaxing the notion of “exact” unlearning to focus on approximate methods with provable privacy guarantees. Further research in this area is crucial for enabling the safe and responsible use of machine learning models in contexts with strict privacy regulations.

Future Directions#

The paper’s “Future Directions” section suggests several promising avenues for extending Langevin unlearning. Extending the framework to handle projected noisy stochastic gradient descent (SGD) is crucial for scalability, though theoretical challenges regarding mini-batching and LSI constant analysis remain. Improving convergence rates is a key priority; exploring techniques beyond current LSI bounds, considering weaker Poincaré inequalities, and employing more advanced sampling methods (Metropolis-Hastings, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo) could significantly enhance efficiency. Finally, while the theoretical contributions address non-convex problems, tightening the non-convex privacy bounds and demonstrating practical applicability for these scenarios remains an important next step. The authors acknowledge the empirical need for stronger assumptions, particularly in non-convex settings. Overall, the future directions highlight the need for both further theoretical refinement and more extensive empirical evaluation across a wider range of datasets and tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure geometrically illustrates the relationship between learning and unlearning. The left panel shows how the learning process’s Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) guarantee is represented as a polyhedron, where a smaller ε0 (initial privacy loss) indicates an easier unlearning task. The right panel demonstrates the learning and unlearning processes on neighboring datasets. It shows that increased learning iterations lead to privacy erosion, whereas increased unlearning iterations result in privacy recuperation.

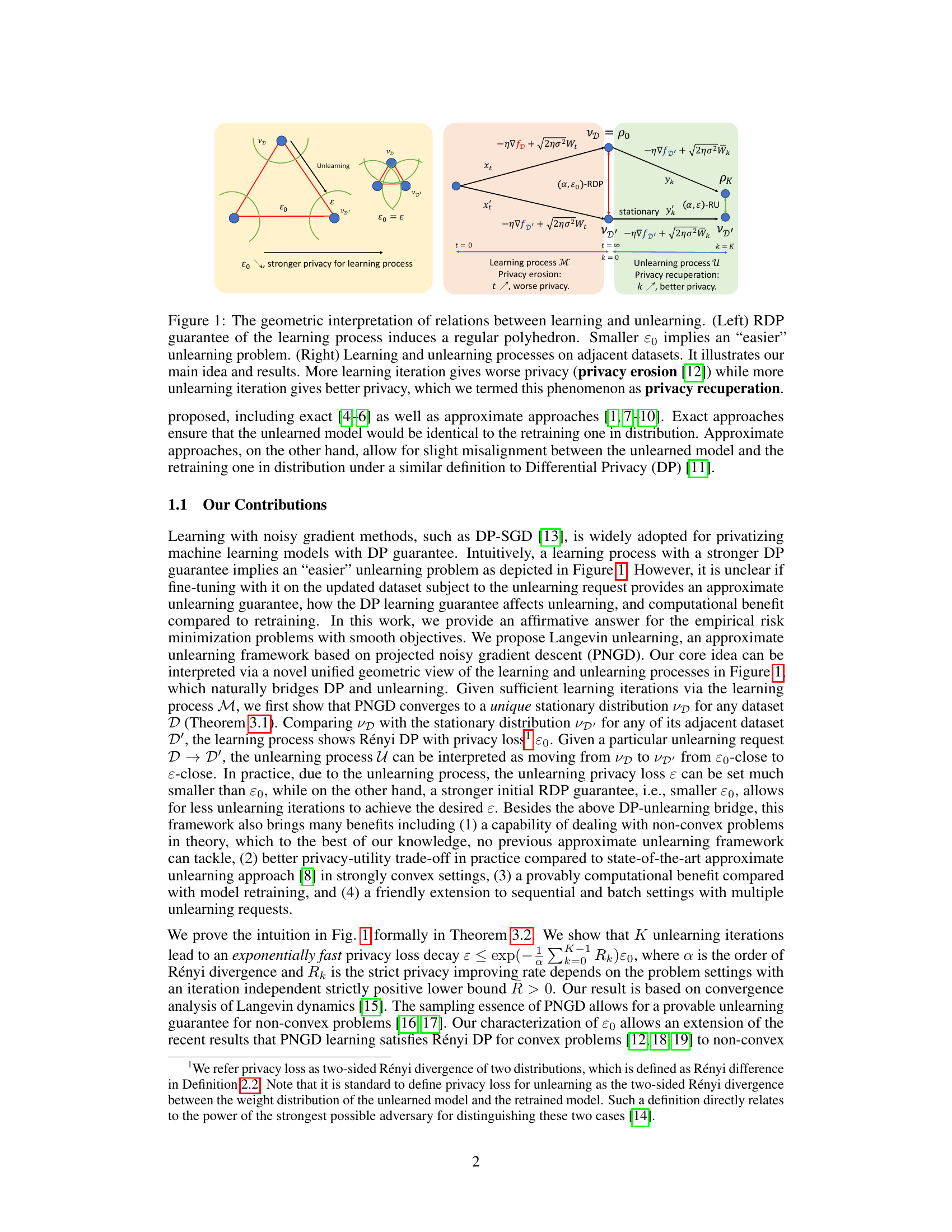

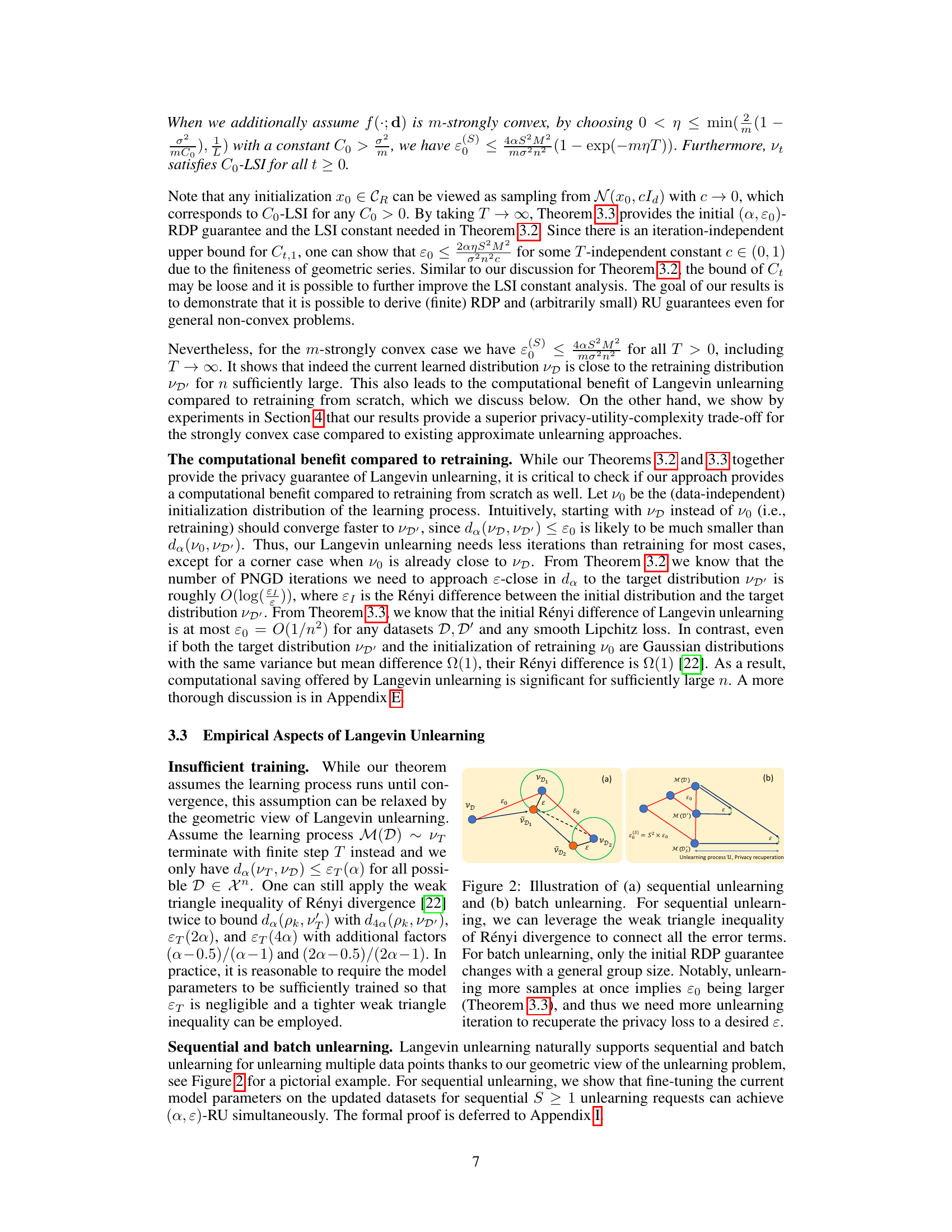

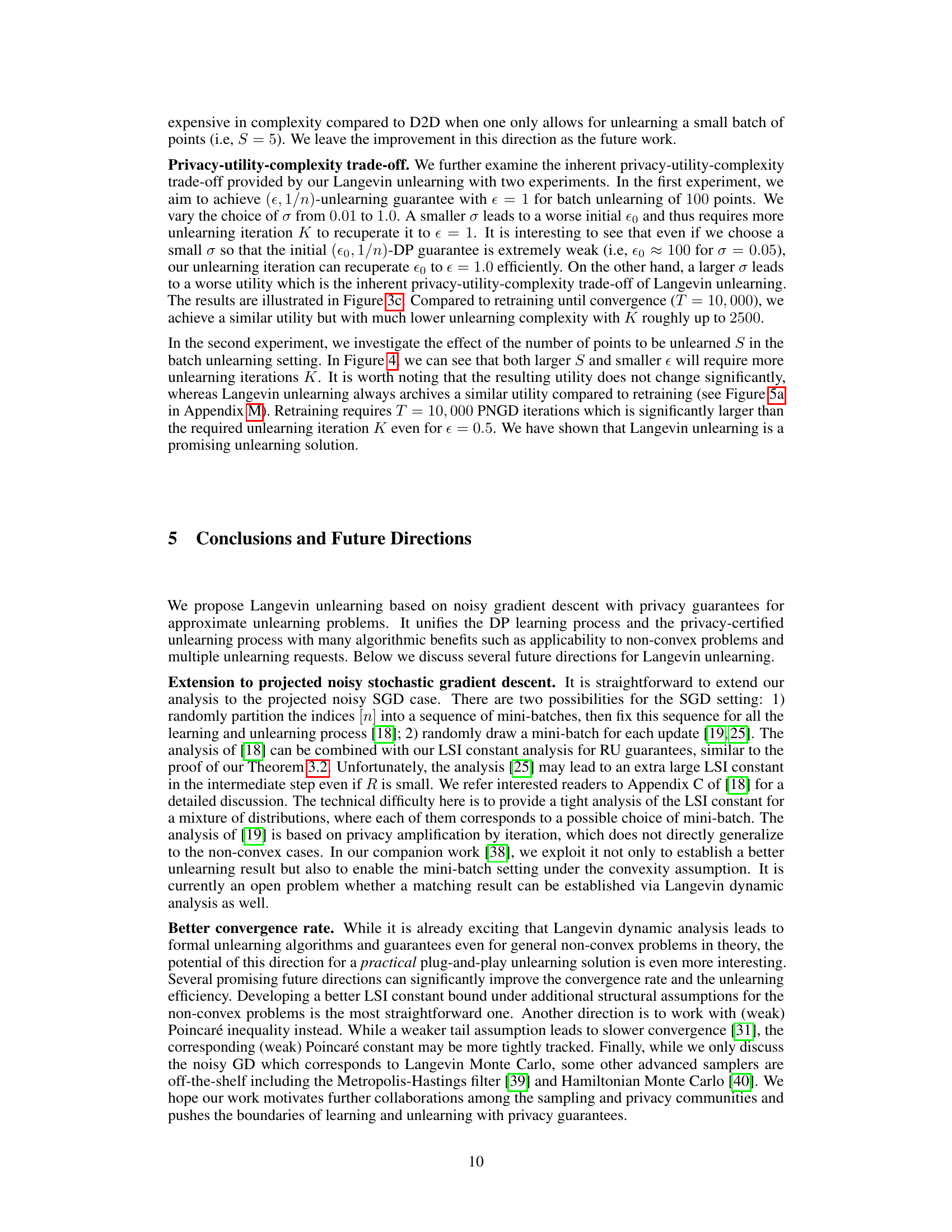

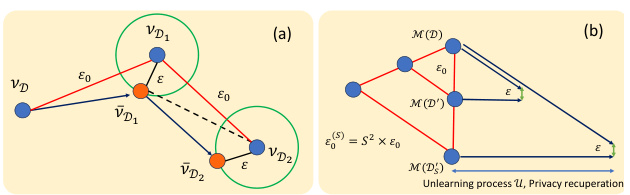

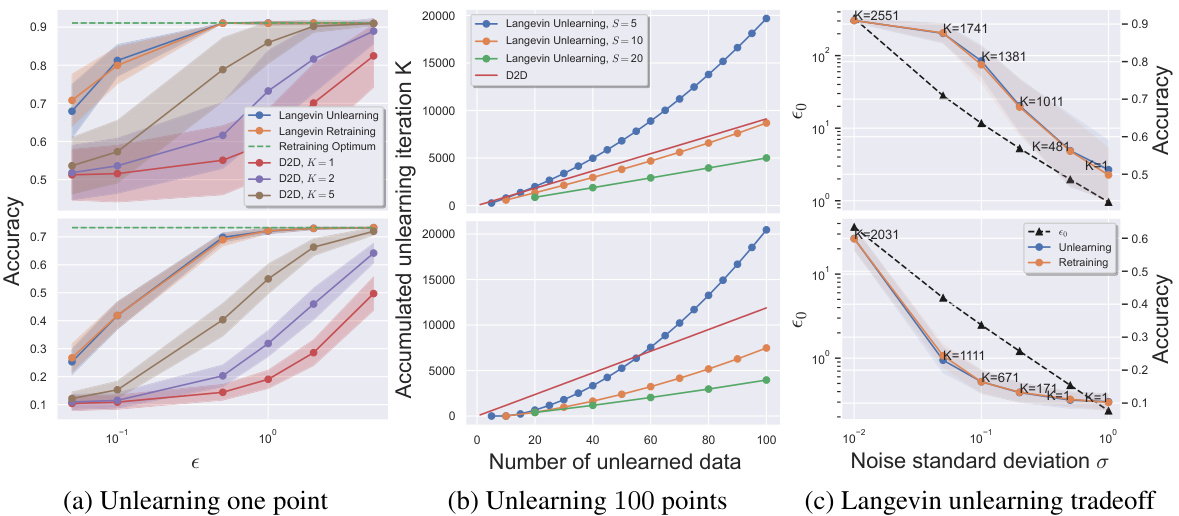

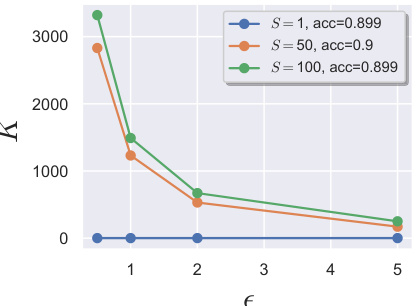

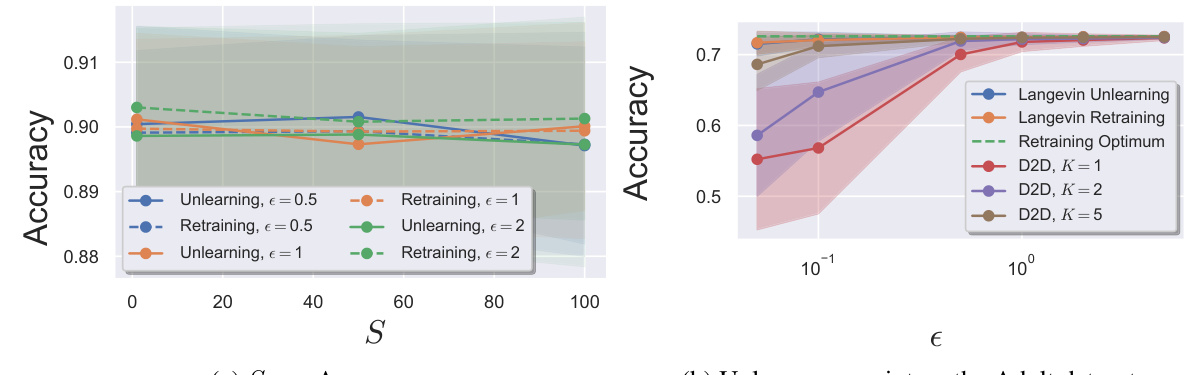

This figure compares the performance of Langevin Unlearning with D2D and Retraining methods on MNIST and CIFAR10 datasets. It shows the tradeoff between privacy, utility (accuracy), and computational complexity (number of iterations) for different unlearning scenarios: unlearning one point, unlearning 100 points, and the impact of noise variance on the tradeoff.

The figure compares the performance of Langevin Unlearning with Delete-to-Descent (D2D) and retraining from scratch for unlearning tasks on MNIST and CIFAR10 datasets. It shows the privacy-utility trade-off, considering different numbers of unlearned data points and unlearning iterations. Panel (a) focuses on unlearning a single point, (b) on unlearning 100 points, and (c) explores the impact of noise variance on utility.

The figure compares the performance of Langevin unlearning against Delete-to-Descent (D2D) and retraining for different unlearning scenarios. It shows the trade-off between privacy, utility (accuracy), and the complexity of the unlearning process under various settings, such as unlearning one or multiple data points, and batch vs. sequential unlearning requests. Subplots (a) and (b) compare the methods’ accuracy with different unlearning iterations. Subplot (c) analyzes the utility-complexity tradeoff of Langevin unlearning.

More on tables

This table lists the values of hyperparameters and constants used in the experiments for MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. It includes the smoothness constant (L), strong convexity constant (m), Lipschitz constant (M), RDP constant (δ), and Log-Sobolev Inequality (LSI) constant (CLSI). These values are essential for the theoretical analysis and practical implementation of the Langevin Unlearning algorithm, and are dataset-specific.

This table presents the values of hyperparameters and constants used in the experiments. These include the smoothness constant (L), strong convexity constant (m), Lipschitz constant (M), RDP constant (δ), and log-Sobolev inequality constant (CLSI) for both the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. The gradient clipping values (M) are also shown. This information is crucial for understanding and reproducing the experimental results.

This table presents the values of hyperparameters and constants used in the experiments. These values are crucial for configuring and understanding the results of the logistic regression models on the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. The table includes smoothness constant (L), strong convexity constant (m), Lipschitz constant (M), RDP constant (δ), and log-Sobolev inequality constant (CLSI).

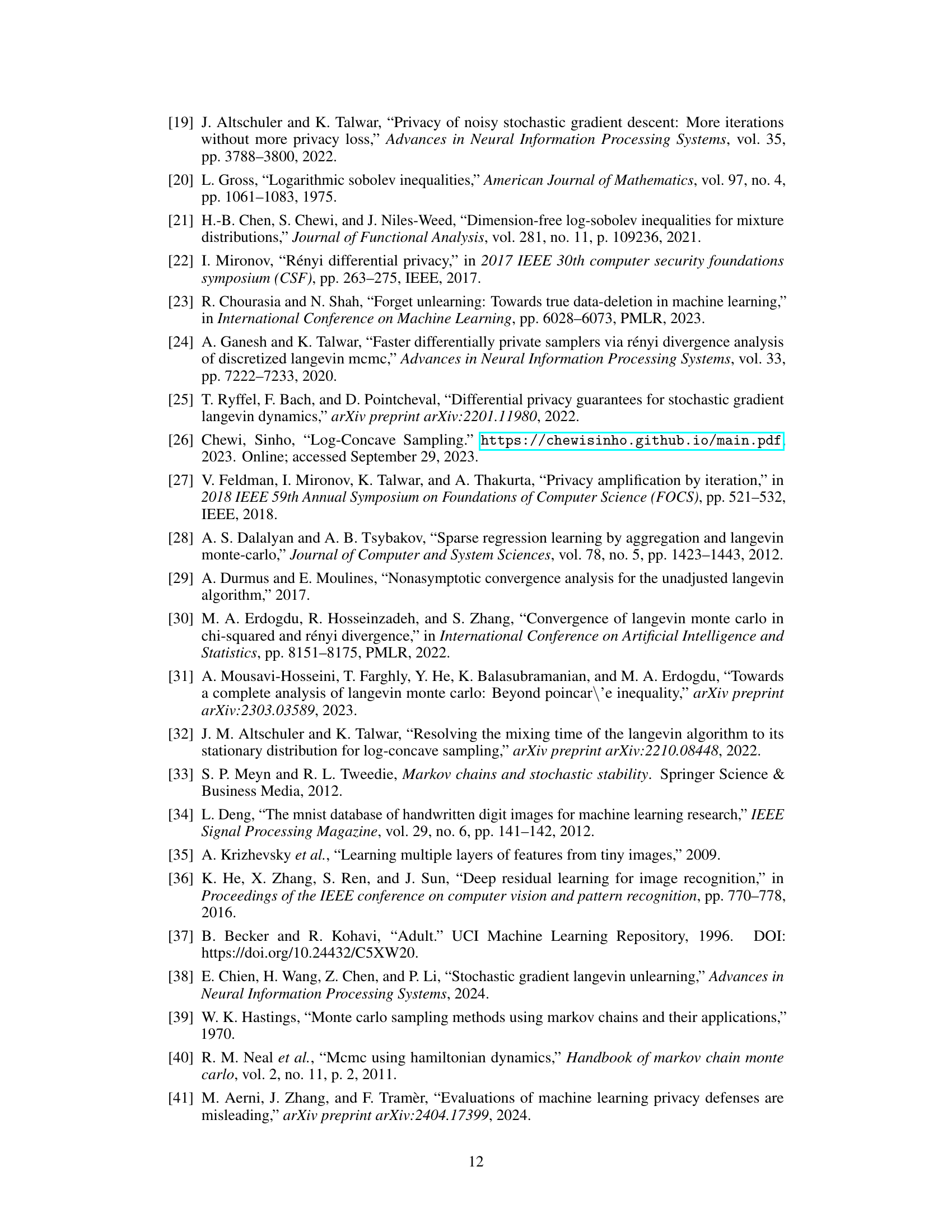

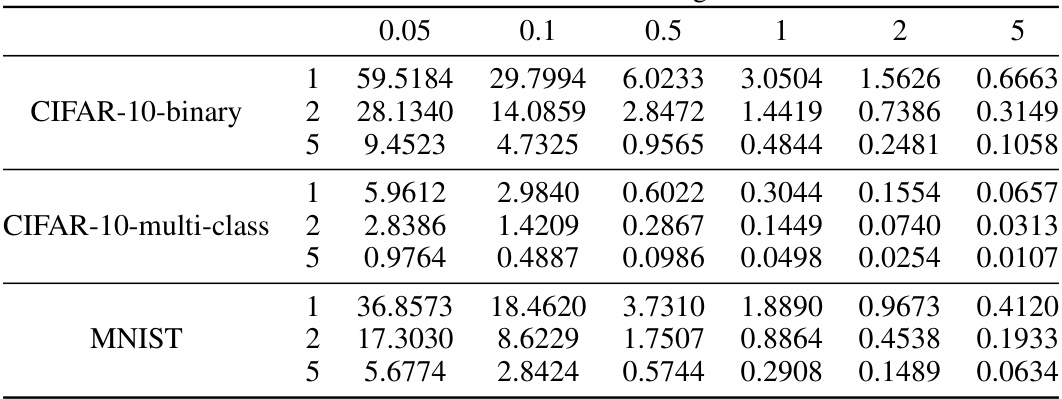

This table shows the noise standard deviation (σ) values used for the Delete-to-Descent (D2D) baseline method in Figure 3a of the paper. Different values of σ were used for different datasets (CIFAR-10-binary, CIFAR-10-multi-class, MNIST) and different numbers of unlearning iterations (1, 2, 5). The values are presented to show how the noise parameter was adjusted for varying levels of privacy requirements. These parameters are crucial in understanding the privacy-utility trade-offs in the experiments.

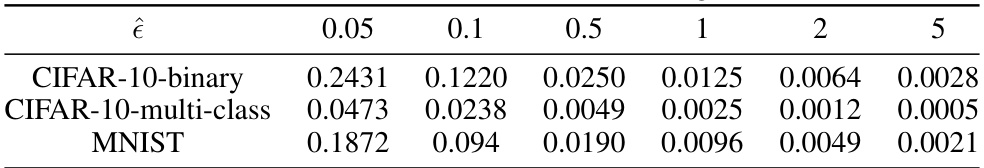

This table presents the optimal noise standard deviation (σ) values determined through a binary search for various target privacy loss parameters (ê). Different values of ê are tested and the corresponding σ is calculated for three datasets: CIFAR-10-binary, CIFAR-10-multi-class, and MNIST. Each dataset has a different set of σ values depending on the target ê.

This table presents the values of hyperparameters and constants used in the experiments. These values are calculated based on the specific properties of the datasets used (MNIST and CIFAR-10) and the loss function used in the experiments. The table includes the smoothness constant (L), strong convexity constant (m), Lipschitz constant (M), RDP constant (δ), and CLSI (logarithmic Sobolev inequality constant). These constants are crucial for the theoretical analysis and privacy guarantees provided in the paper. The gradient clip value (M) is used to control the norm of the gradients during the training process, and the RDP constant is a parameter that determines the level of privacy provided by the algorithm. The CLSI constant is a measure of how well the probability distribution over model parameters satisfies the log-Sobolev inequality, a crucial property for the convergence analysis.

Full paper#