↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Approximating the action of matrix functions (e.g., square root, logarithm) on vectors is crucial in many fields, including machine learning and statistics. While recent algorithms boast strong theoretical guarantees, a classic method called Lanczos-FA frequently outperforms them in practice. This lack of theoretical understanding motivates the need for improved analysis.

This research addresses this gap by proving that Lanczos-FA achieves near-optimal performance for a natural class of rational functions. The approximation error is shown to be comparable to that of the best possible Krylov subspace method, up to a multiplicative factor that depends on the function’s properties and the matrix’s condition number, but not on the number of iterations. This result provides a strong theoretical foundation for the excellent performance of Lanczos-FA, especially for functions well-approximated by rationals, like the matrix square root.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with matrix functions, especially those using Krylov subspace methods. It provides a theoretical justification for the surprising practical success of the Lanczos method, a classic algorithm often outperforming newer, theoretically-guaranteed methods. This work bridges the theory-practice gap, offering valuable insights and potential avenues for algorithm improvement and new theoretical guarantees.

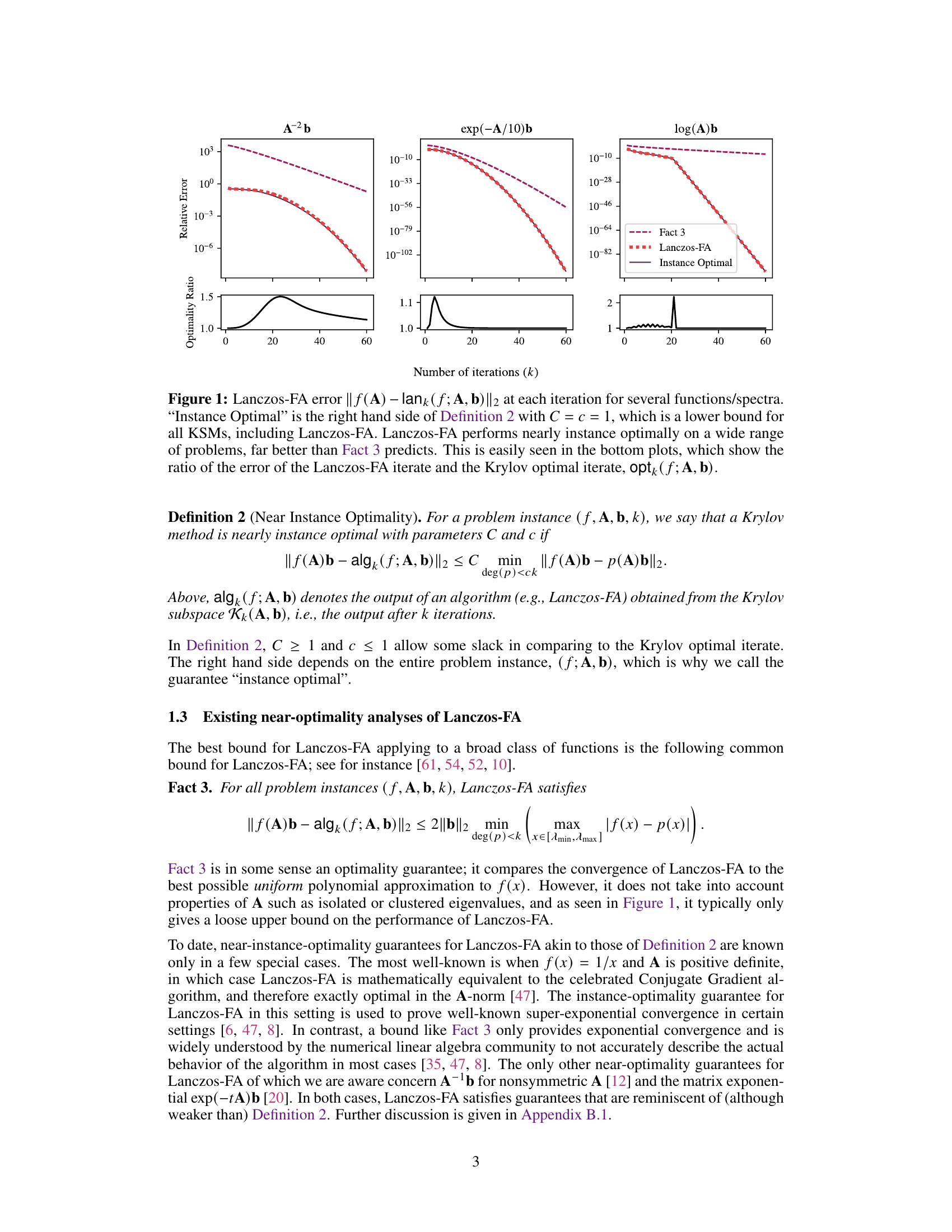

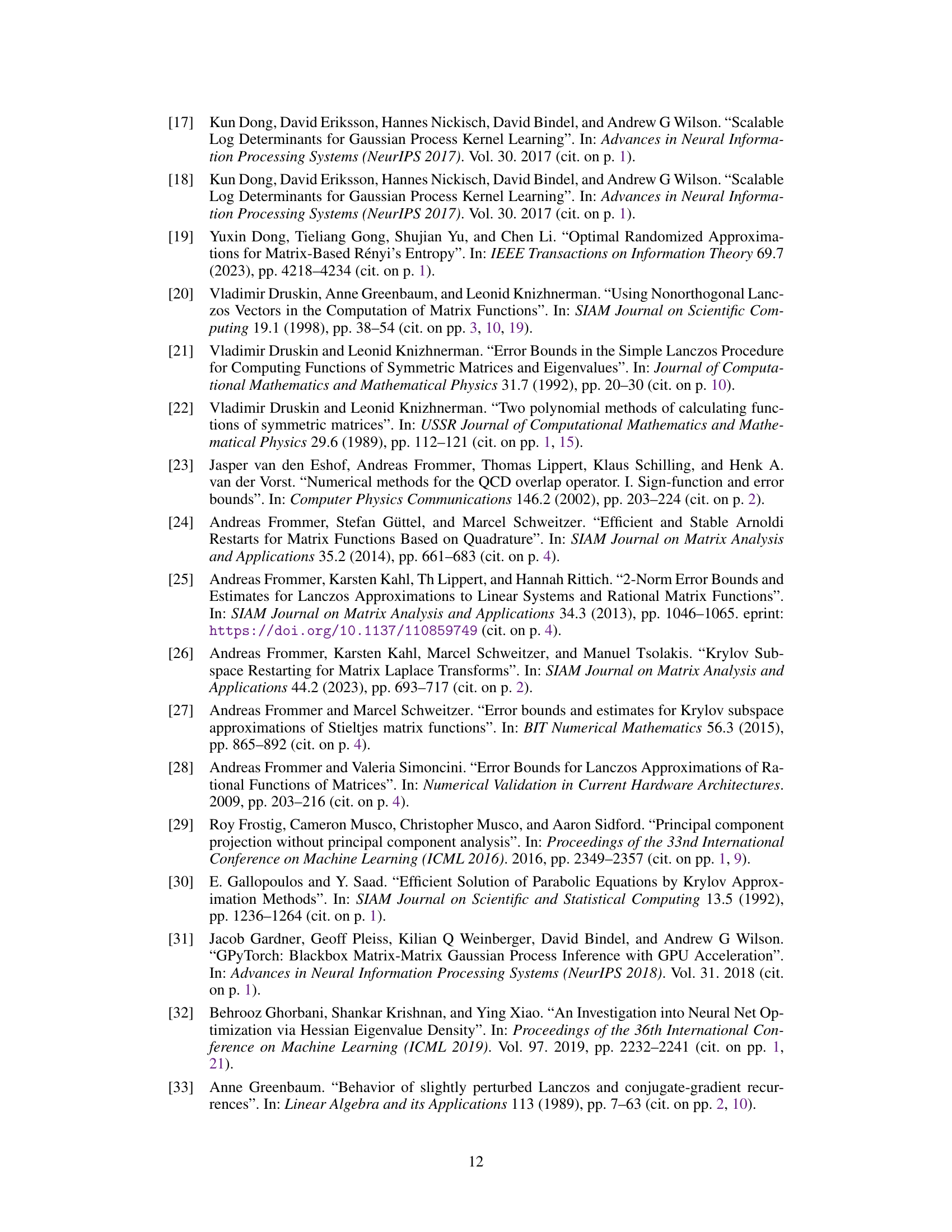

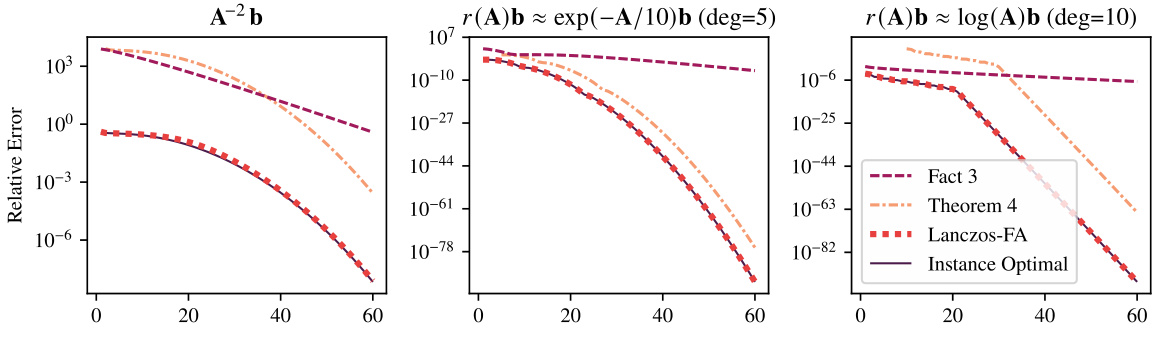

Visual Insights#

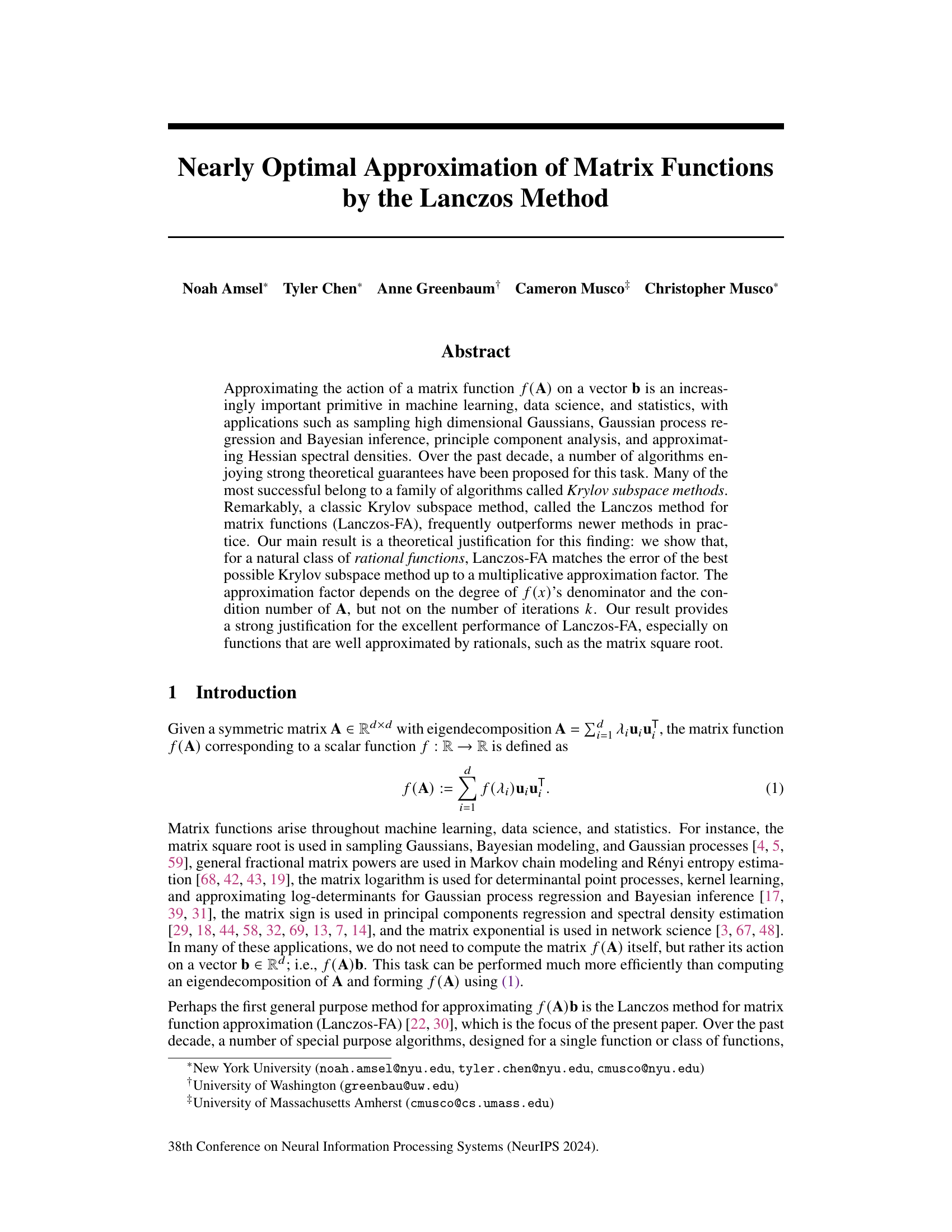

This figure compares the error of the Lanczos-FA algorithm to the instance optimal error for three different matrix functions: A⁻²b, exp(-A/10)b, and log(A)b. The top row shows the error of each method, while the bottom row shows the ratio of the Lanczos-FA error to the instance optimal error. The figure demonstrates that Lanczos-FA performs nearly optimally, achieving error very close to the best possible Krylov subspace method, significantly outperforming the theoretical bounds predicted by Fact 3.

In-depth insights#

Lanczos-FA Optimality#

The Lanczos-FA algorithm, while simple, surprisingly outperforms newer, theoretically-guaranteed methods for approximating matrix functions. This paper investigates this phenomenon by exploring Lanczos-FA’s optimality. The core contribution lies in establishing near instance optimality for a class of rational functions—showing Lanczos-FA’s error is comparable to the best possible Krylov subspace method (up to a multiplicative factor). This factor depends on the rational function’s degree and A’s condition number, but notably, not on the iteration count. The analysis extends to non-rational functions that are well-approximated by rationals, offering a theoretical basis for Lanczos-FA’s practical success. However, the analysis also reveals that for functions like the matrix square root, weaker near-optimality guarantees hold, highlighting the complexity of fully characterizing Lanczos-FA’s behavior. Experimental results confirm the superiority of Lanczos-FA over specialized algorithms, demonstrating the practical value of the theoretical findings.

Rational Approx.#

The heading ‘Rational Approx.’ likely refers to a section detailing the use of rational functions to approximate matrix functions. This is a crucial technique because rational functions often provide significantly better approximations than polynomials for certain matrix functions, especially those with singularities or branch cuts. The discussion likely covers how to choose appropriate rational functions, potentially using techniques like Padé approximants or best rational approximations. A key aspect would be analyzing the trade-off between approximation accuracy and computational cost: higher-degree rational functions offer better accuracy but increase complexity. The section would probably present error bounds for the rational approximations, comparing them to those of polynomial approximations, to demonstrate their superiority. The efficacy of Lanczos-FA in the context of rational approximations is likely a major focus, showcasing its ability to leverage these approximations effectively for efficient matrix function evaluation. Finally, the authors might discuss specific applications where using rational functions is particularly beneficial, like the computation of matrix square roots or other fractional powers, which often serve as building blocks for more complex algorithms.

Near-Optimal Bounds#

The concept of “Near-Optimal Bounds” in the context of a research paper likely refers to theoretical guarantees on the performance of an algorithm. These bounds would aim to show that the algorithm’s output is close to the best possible solution achievable within certain constraints, such as computational resources or a specific class of problems. The “near” aspect suggests that the bound might not be perfectly tight, but it provides a reasonable approximation. The value of near-optimal bounds lies in providing a theoretical justification for the effectiveness of an algorithm and helps to understand its behavior. This allows for comparisons between different approaches with proven optimality guarantees and offers valuable insights into the algorithm’s strengths and limitations. The strength of such bounds often depends on factors like the problem’s structure, the algorithm’s design, and the accuracy of the theoretical model. Sharper bounds are highly desirable but often challenging to obtain. Ultimately, such a result would increase confidence in an algorithm and direct future research towards improving specific aspects of the method.

Empirical Validation#

An empirical validation section in a research paper would rigorously test the theoretical claims. It would involve designing experiments to assess the performance of Lanczos-FA against existing methods. Key aspects would include selecting diverse test matrices reflecting varied eigenvalue distributions and condition numbers. The choice of matrix functions (e.g., square root, logarithm, exponential) would also be important, considering functions that are well-approximated by rationals and others that are not. Careful selection of test vectors (b) is critical; both random and specially constructed vectors might be used to explore different scenarios. The validation would compare the error and runtime of Lanczos-FA against those of competing algorithms, possibly using different error metrics (e.g., 2-norm). Statistical significance should be addressed, considering the stochastic nature of some algorithms. Visualization of the results, such as convergence plots showing error versus iterations, are crucial for demonstrating the practical performance. Finally, the discussion should interpret the results in light of the theoretical analysis, explaining both successes and any discrepancies observed. Analyzing the scaling behavior of the methods with respect to problem size (dimensionality) and other parameters is essential for assessing their practical applicability.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the near instance-optimality results beyond rational functions to encompass broader classes, such as Markov functions or functions with complex poles. Investigating the impact of finite-precision arithmetic on the optimality guarantees is crucial for practical applications. A deeper understanding of the dependence on rational function degree in current bounds is needed to improve their tightness. Developing tighter bounds that accurately capture Lanczos-FA’s rapid convergence in practice is another key area. Finally, exploring the connection between Lanczos-FA’s performance and specific spectral properties of matrices could reveal further insights into its remarkable effectiveness, especially concerning matrices with clustered or isolated eigenvalues. This could lead to more accurate predictions of its performance in various scenarios and the development of improved algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

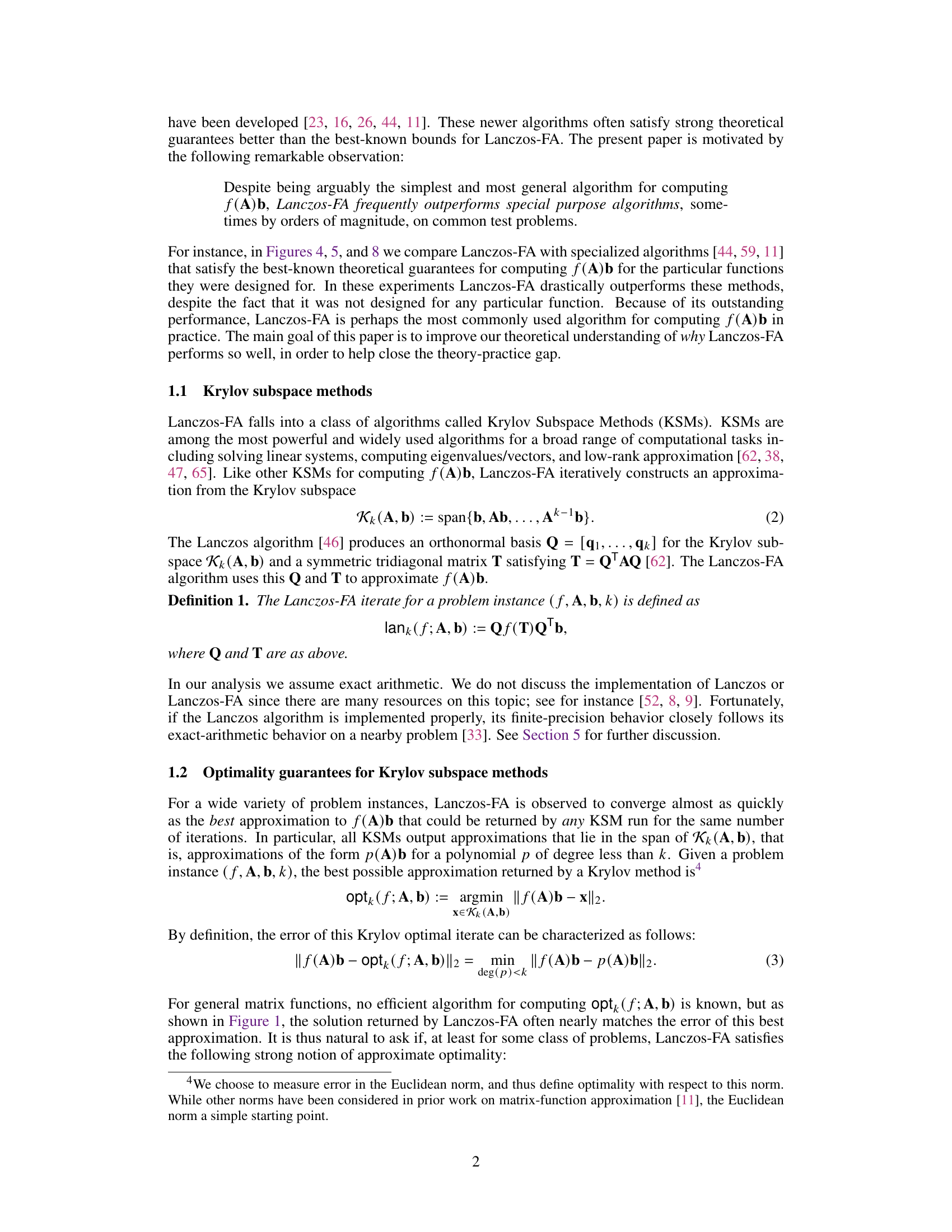

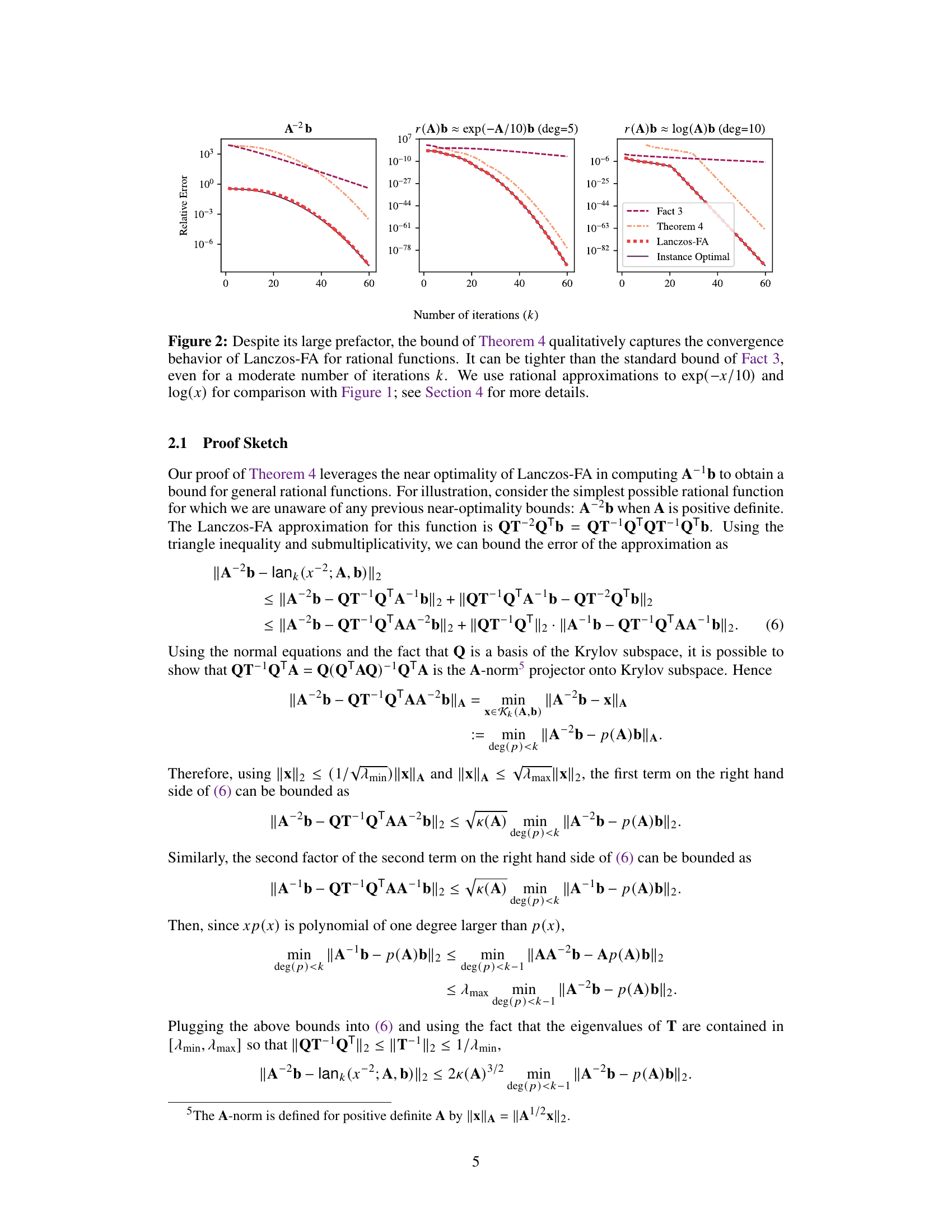

This figure compares the error bounds of Theorem 4 and Fact 3 with the actual error of Lanczos-FA and the instance optimal error for three different functions: A⁻², a rational approximation of exp(-A/10), and a rational approximation of log(A). It demonstrates that while Theorem 4 has a large prefactor, it more accurately reflects the convergence behavior of Lanczos-FA than the simpler Fact 3, especially for a larger number of iterations.

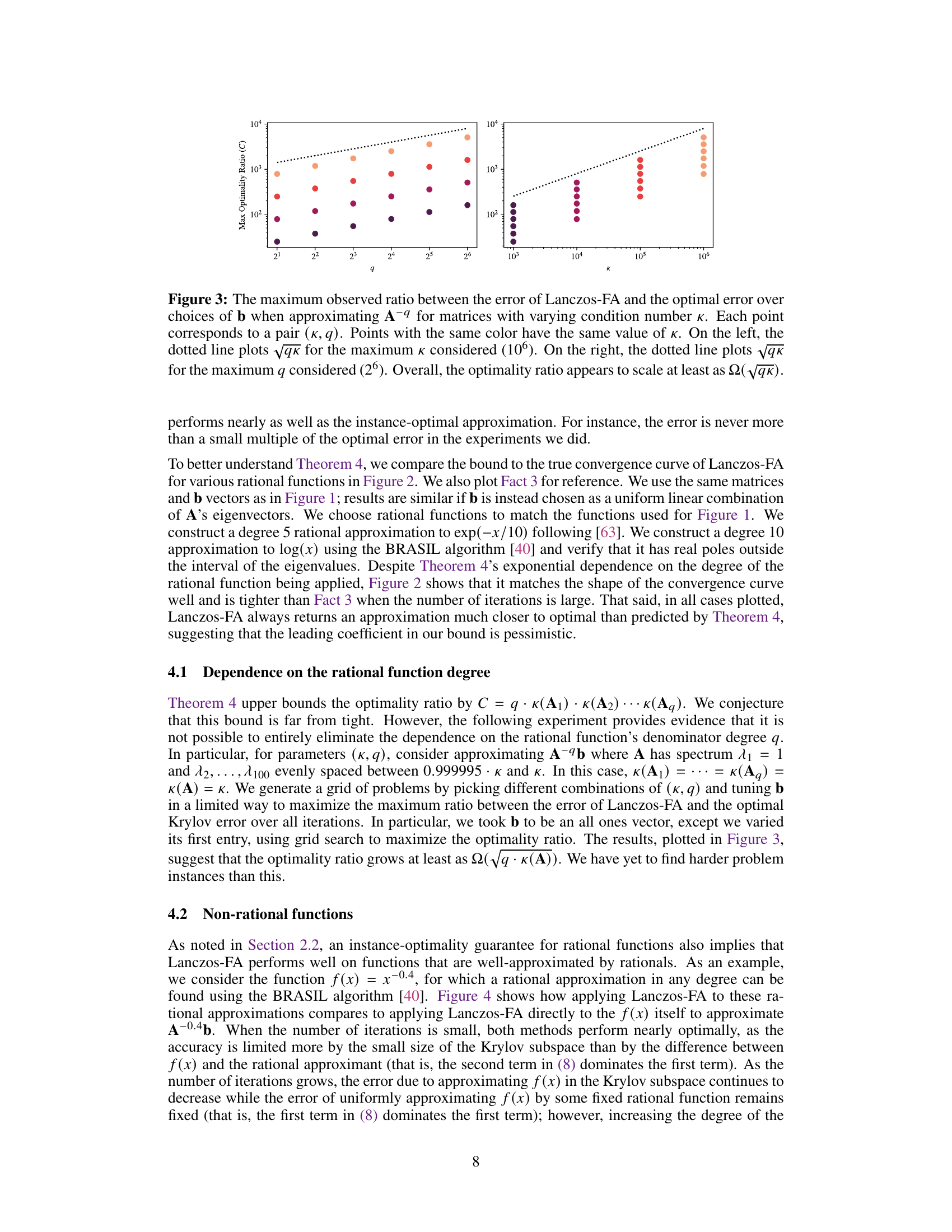

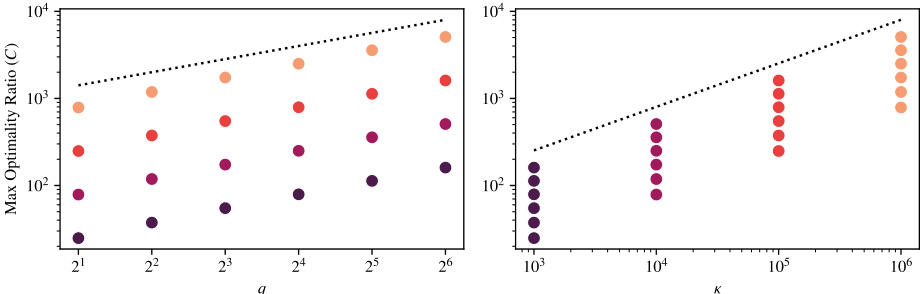

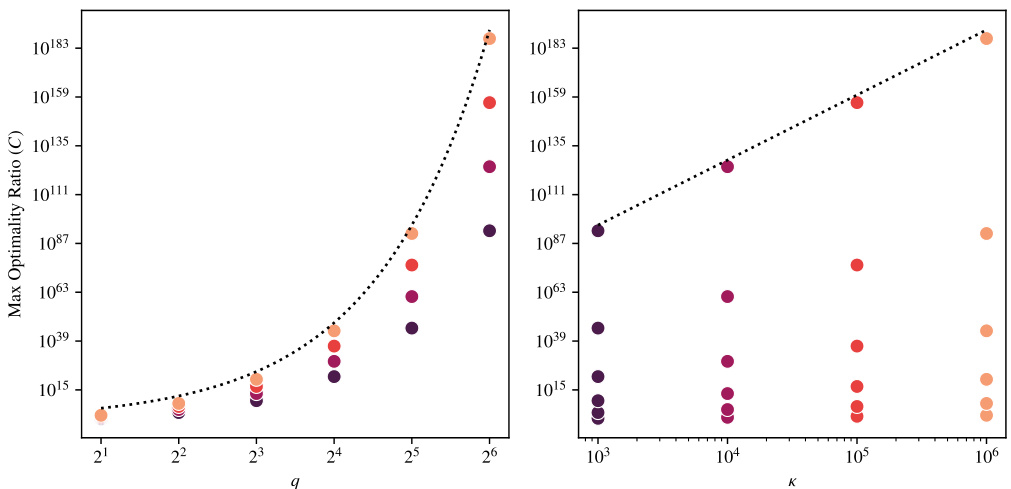

This figure shows the maximum observed ratio between the error of Lanczos-FA and the optimal error when approximating the inverse of A raised to the power of q (A⁻q). The experiment is run for matrices with various condition numbers (κ). Each point represents a pair of (k, q) values, where k is the number of iterations and q is the degree of the rational function. Points of the same color share the same condition number. The dotted lines show the scaling of √qκ, suggesting the optimality ratio scales at least as Ω(√qκ). The left plot fixes the maximum κ, and the right plot fixes the maximum q.

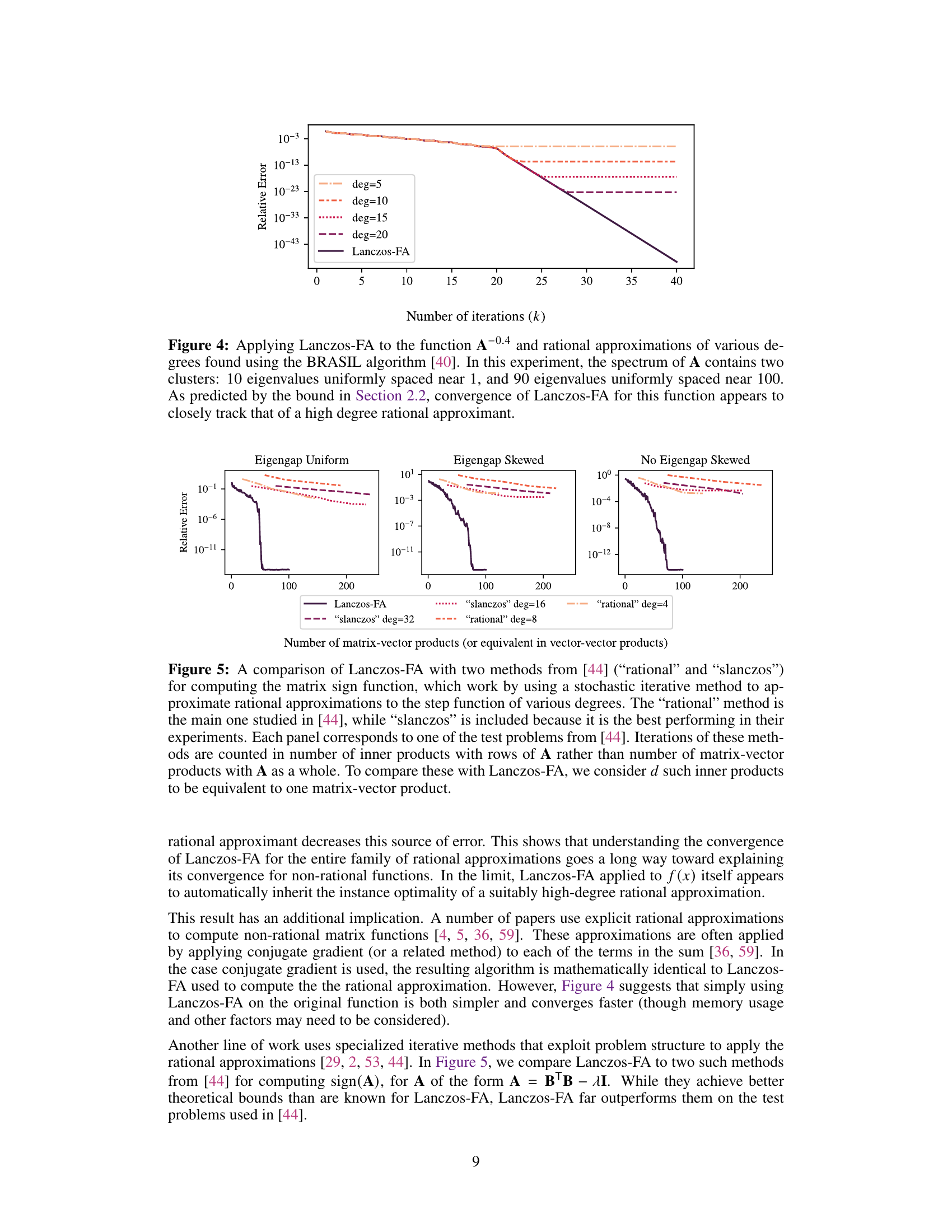

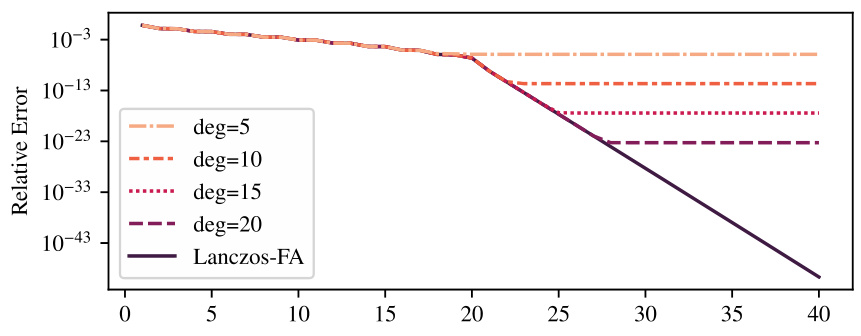

The figure compares the convergence behavior of Lanczos-FA algorithm for approximating A-0.4b with the convergence of rational approximations of various degrees. The spectrum of matrix A consists of two clusters of eigenvalues: one close to 1 and the other close to 100. The results show that the convergence of Lanczos-FA closely matches that of the high degree rational approximant, consistent with theoretical prediction of Section 2.2 of the paper.

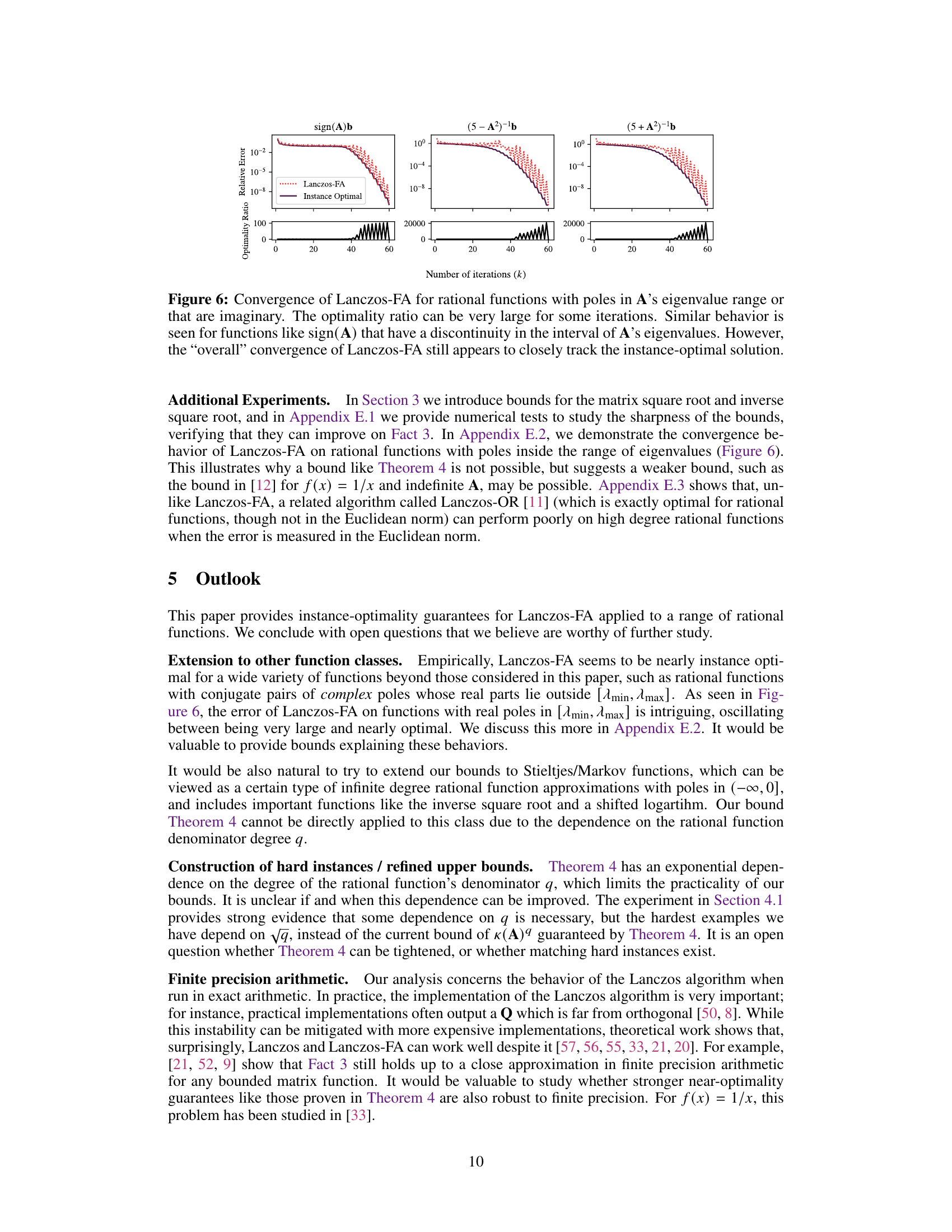

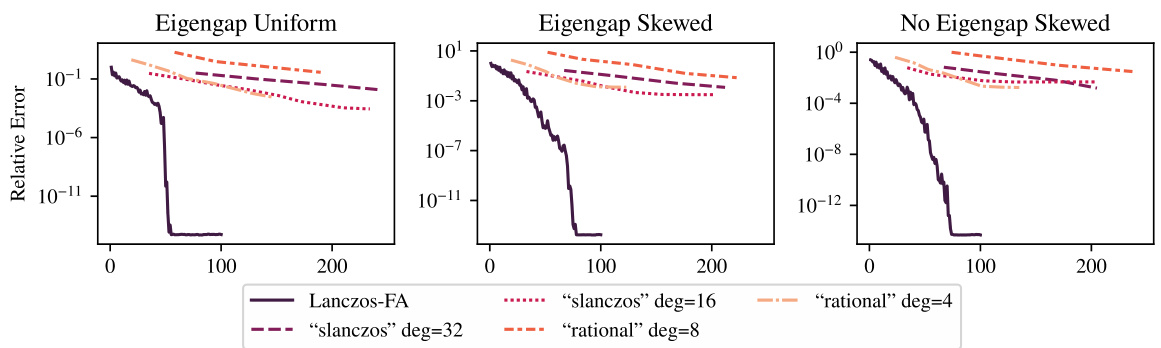

This figure compares the performance of Lanczos-FA to two other methods from a previous paper [44] for computing the matrix sign function. The other methods use a stochastic iterative approach to approximate rational approximations of the step function. The plot shows that Lanczos-FA significantly outperforms these other methods.

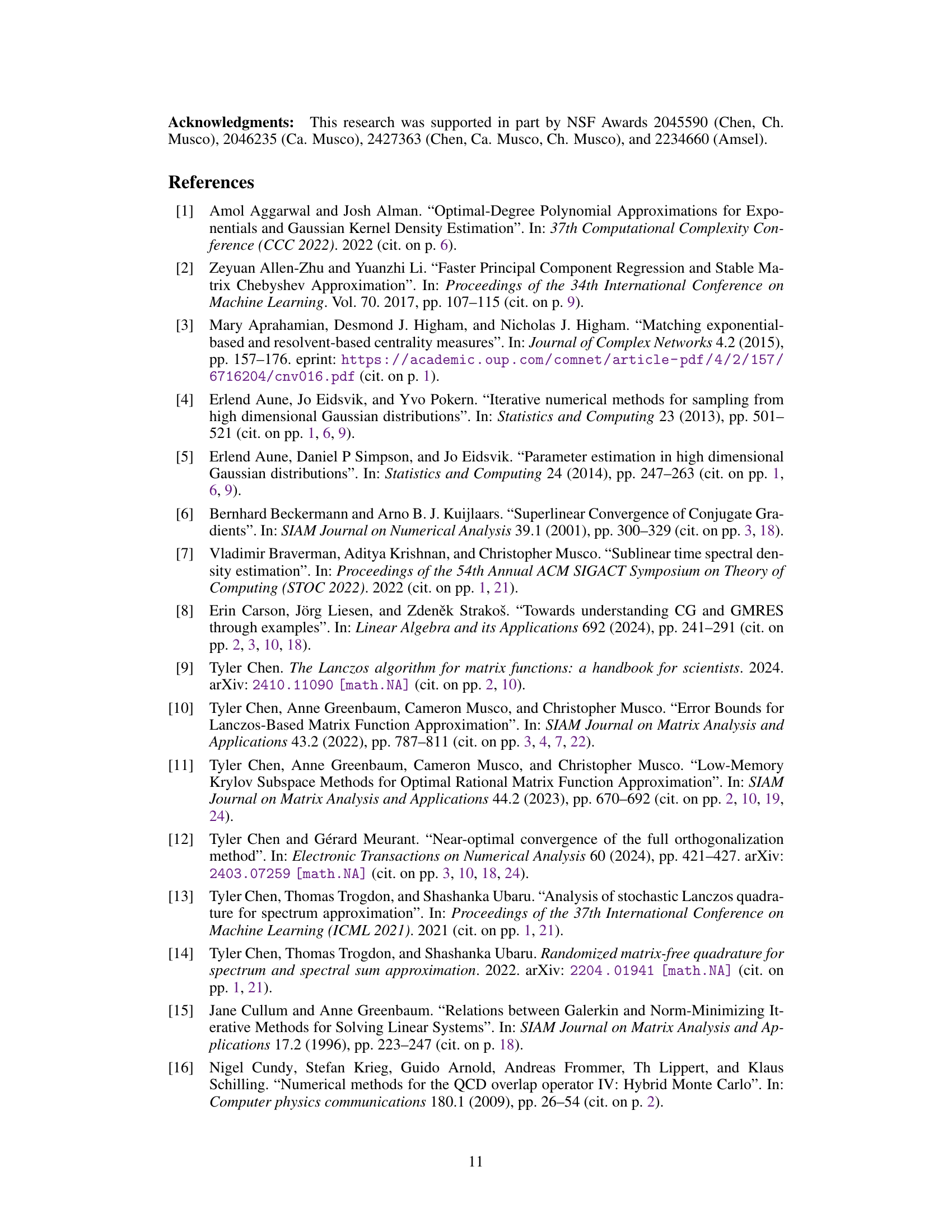

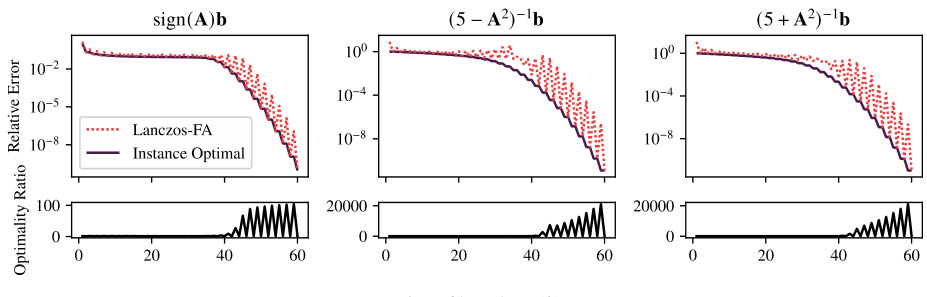

This figure displays the convergence behavior of the Lanczos-FA algorithm for three different rational functions. Each function has poles (discontinuities) within the range of the eigenvalues of the matrix A. The top row shows plots of the relative error, comparing the Lanczos-FA approximation to the instance-optimal Krylov subspace approximation, while the bottom row shows the ratio of these errors. Despite the fact that the optimality ratio is high at certain iterations (meaning that the algorithm’s error significantly exceeds the optimal error), the overall error convergence of Lanczos-FA remains close to the instance optimum.

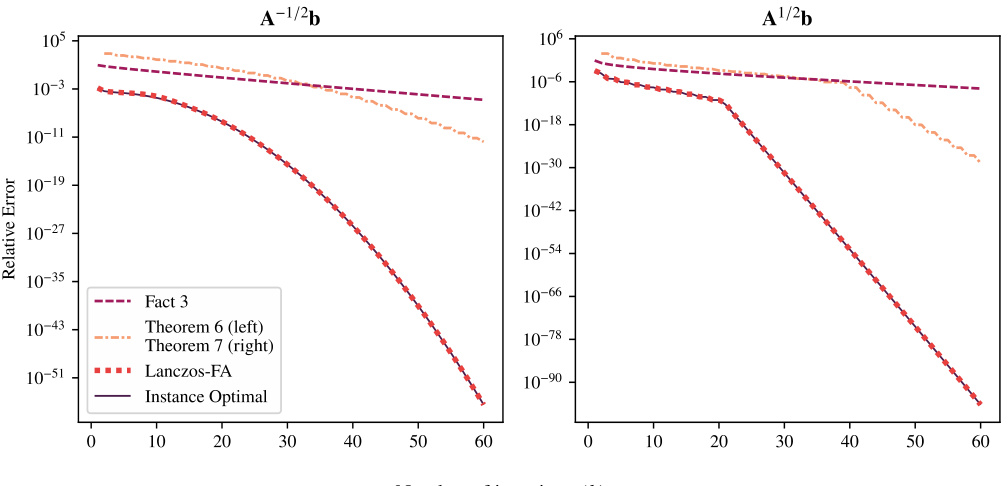

This figure compares the error bounds from Theorems 6 and 7 with the actual error of the Lanczos-FA algorithm and the optimal error when applied to compute A1/2b and A-1/2b. It shows that the bounds from Theorems 6 and 7 are tighter than Fact 3, a previously known bound, although they predict a slower convergence rate than what’s actually observed.

This figure shows the maximum observed ratio between the error of the Lanczos-FA algorithm and the optimal error for different values of condition number (κ) and rational function degree (q). The x-axis represents either k (iterations) or κ, while the y-axis is the maximum optimality ratio observed. Points of the same color represent the same κ or q value. The dotted lines show the theoretical lower bound of the optimality ratio.

Full paper#