↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing theories struggle to explain generalization in overparameterized neural networks, particularly when dealing with noisy labels, as kernel methods and benign overfitting theories are often suboptimal. This is because the theoretical assumptions of these frameworks (e.g., interpolating solutions) do not hold true in scenarios with noisy data where gradient descent often converges to local minima that are not global optimums.

This work introduces a new theory focusing on the stability of these local minima reached during the training process. The authors demonstrate that gradient descent with a fixed learning rate converges to local minima representing smooth functions, and these solutions generalize well even with noise. They rigorously prove near-optimal error bounds and experimentally validate their findings, showing how large step sizes implicitly induce sparsity and regularization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges existing theories of neural network generalization, particularly those relying on kernel methods and benign overfitting. It offers a novel theoretical framework for understanding generalization in non-interpolation scenarios, relevant to practical training setups where gradient descent doesn’t reach global optima. The near-optimal rates achieved open doors for further research on improving efficiency and robustness of neural network training.

Visual Insights#

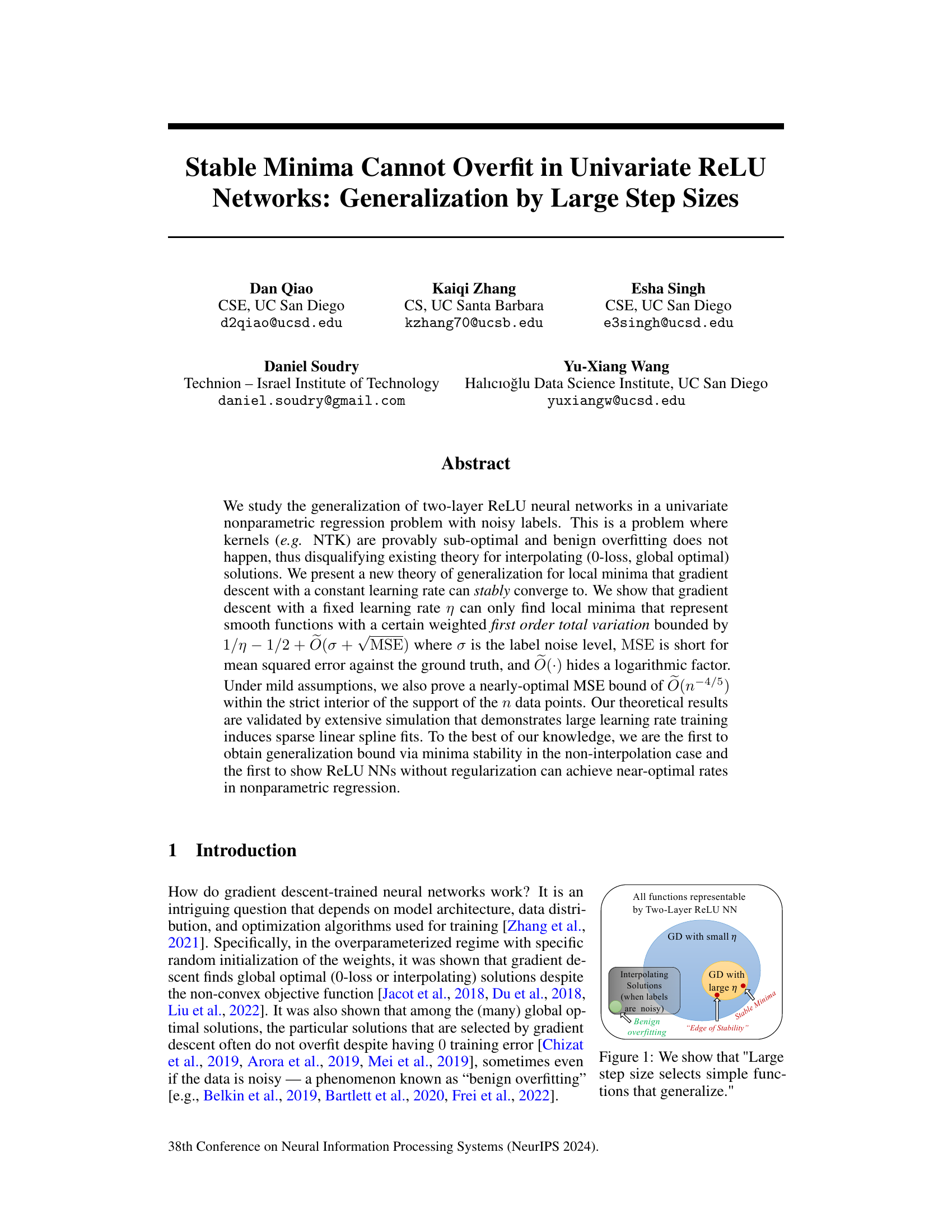

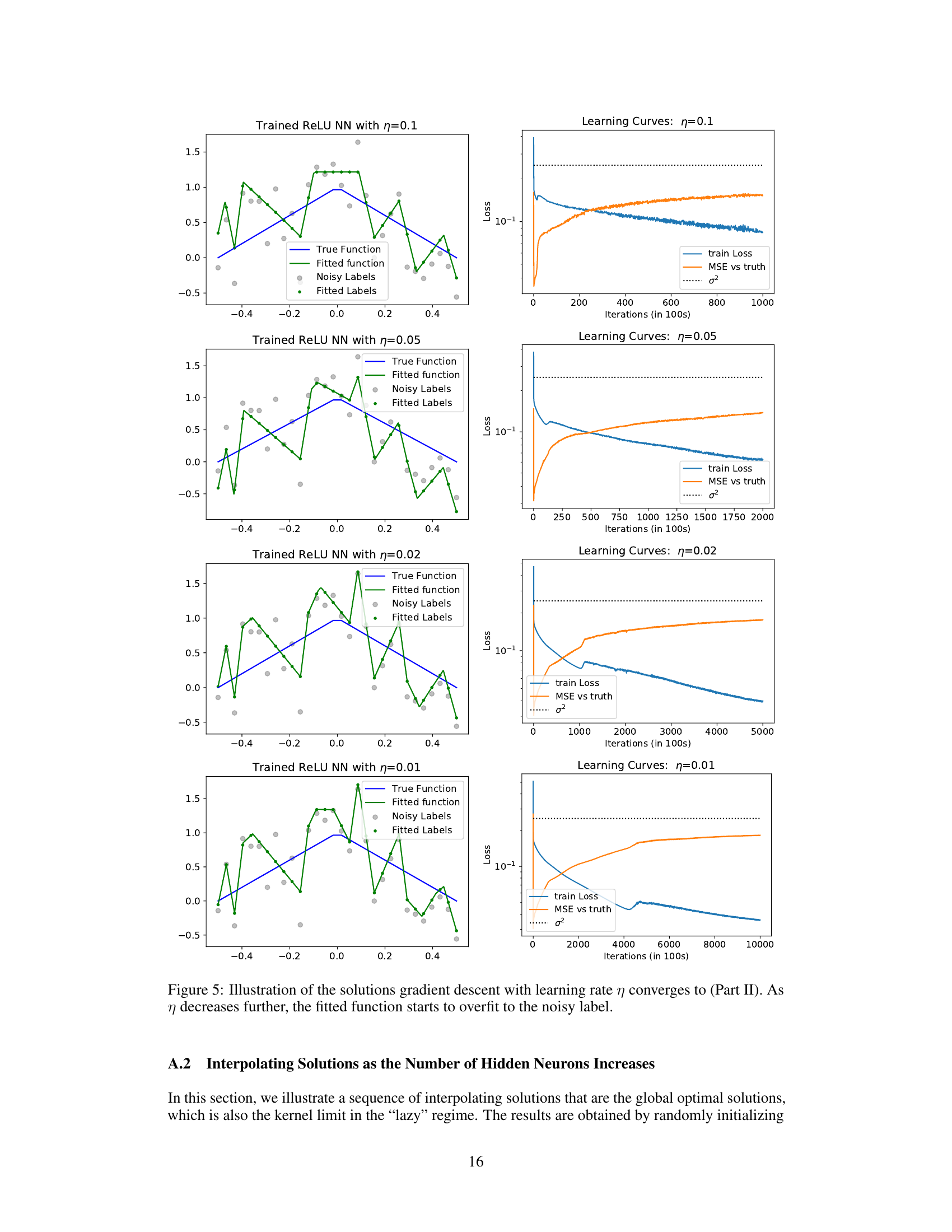

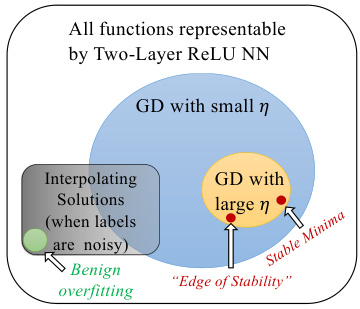

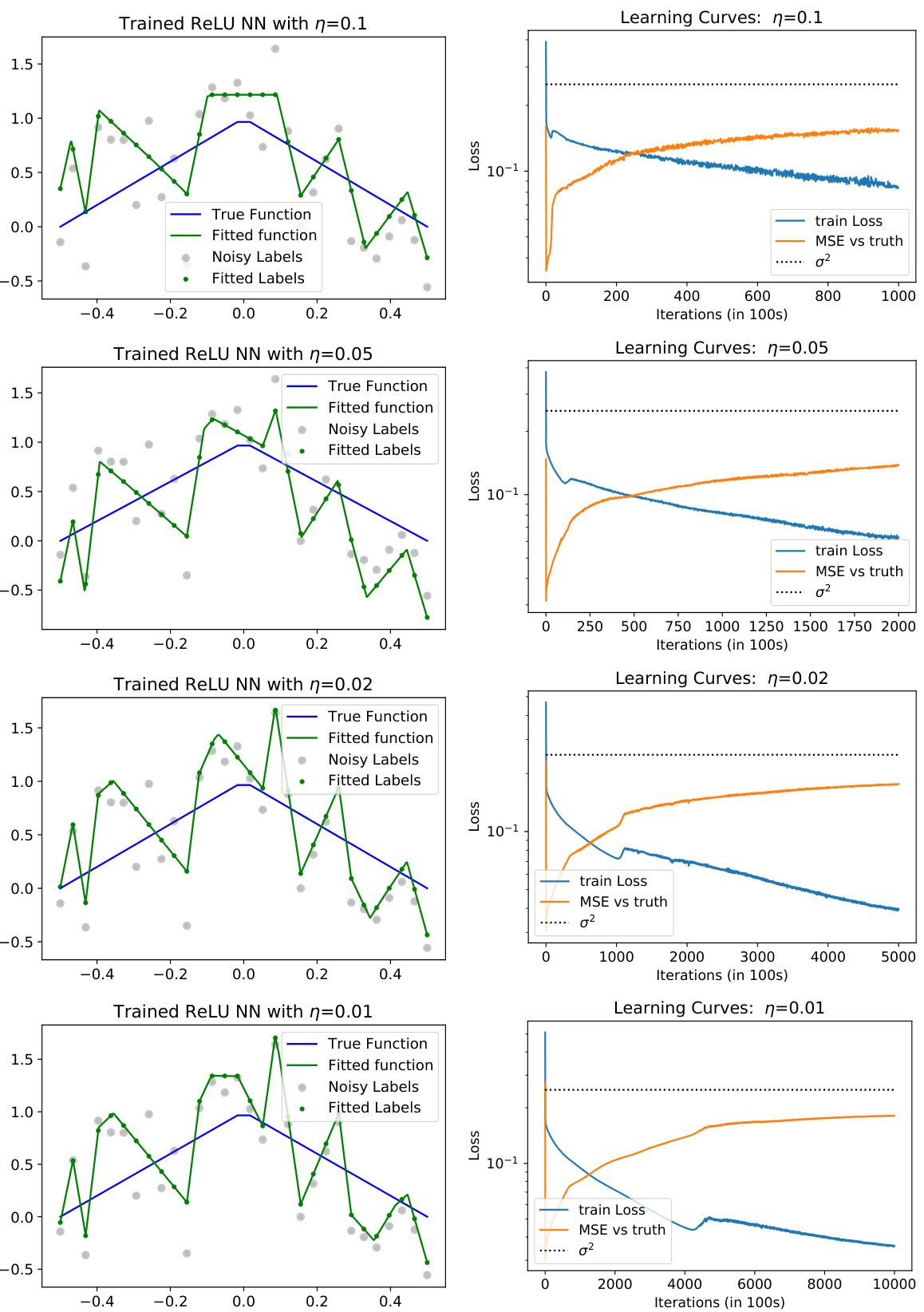

This figure illustrates the different types of solutions that can be found by gradient descent training of two-layer ReLU neural networks, depending on the step size (learning rate). When the learning rate is small, gradient descent can find interpolating solutions (i.e., solutions that perfectly fit the noisy training data). In the presence of noise, such solutions tend to overfit. However, when the learning rate is large, gradient descent is more likely to find stable minima that represent simpler functions. These stable minima exhibit good generalization, even in the presence of noisy labels. The figure shows the relationship between the step size and the type of solution found, highlighting the ‘Edge of Stability’ regime where the stability of the minima is related to the step size.

In-depth insights#

ReLU Generalization#

The ReLU activation function’s role in generalization is a complex issue in deep learning. Existing theories often struggle to fully explain ReLU networks’ generalization ability, especially in scenarios beyond the ‘kernel regime’ where interpolation occurs. This paper makes significant headway by focusing on the non-interpolating case with noisy labels, challenging conventional wisdom about benign overfitting. The authors propose a novel theory of generalization based on the stability of local minima found by gradient descent, showing that these stable solutions are inherently simple and smooth (low total variation), effectively preventing overfitting even without explicit regularization. This is a crucial departure from existing kernel-based theories. The research establishes near-optimal generalization bounds, suggesting ReLU networks can achieve optimal statistical rates in nonparametric regression under specific conditions. Their analysis provides insights into how gradient descent’s implicit bias toward simple functions contributes to robust generalization in real-world scenarios, highlighting the importance of large step sizes in this process.

Minima Stability#

Minima stability, in the context of neural network training, refers to the phenomenon where a model’s parameters converge to a stable local minimum during optimization. A stable minimum is characterized by its resistance to small perturbations. This stability is crucial for generalization because it implies that the model’s performance won’t drastically change with slightly different initializations or noisy data. The paper explores this concept in the non-interpolation regime, which contrasts with existing theories often relying on interpolation (zero training error). The stability of local minima allows for generalization bounds to be derived, particularly important when dealing with noisy labels, demonstrating how the learned functions exhibit specific properties related to smoothness and sparsity. The key idea is that gradient descent, when using appropriately sized learning rates, preferentially converges to solutions that are not just locally optimal but also stable and generalizable. This research offers a theoretical framework that moves beyond kernel regimes and interpolation-based approaches to understand the performance of gradient-descent trained neural networks.

Large Step Sizes#

The concept of “Large Step Sizes” in the context of training neural networks is intriguing. It challenges the conventional wisdom that smaller, more cautious steps lead to better generalization. The research suggests that larger step sizes can drive the optimization process towards a different set of minima, ones that may be more stable and generalize better than those found using smaller learning rates. This is particularly interesting in non-parametric regression problems with noisy data, where interpolating solutions are known to overfit. The study’s findings indicate that the increased step size leads to solutions with smaller weighted first-order total variation, promoting sparsity and smoothness, characteristics favorable for generalization. This is a significant counterpoint to the current emphasis on benign overfitting and kernel regimes. The ability of large steps to select simple, generalizing functions offers a new perspective on training deep networks and raises questions about the implicit bias of gradient descent. Further investigation into the precise mechanisms driving this phenomenon could significantly impact training methodologies and our theoretical understanding of neural networks.

Optimal Rates#

The heading ‘Optimal Rates’ in a machine learning research paper likely refers to the theoretical efficiency of a model’s learning process. It examines whether the model’s generalization error (the difference between its performance on unseen data and training data) decreases at the fastest possible rate as the amount of training data increases. This is a crucial aspect because it helps determine how much data is needed to achieve a desired level of accuracy and whether a proposed method is competitive in terms of data efficiency. The analysis typically involves comparing the rate of decrease in generalization error to known lower bounds from statistical learning theory, hence demonstrating the model’s optimality within specific contexts such as nonparametric regression. Near-optimal rates may also be discussed when a model’s learning rate is slightly slower than the theoretical best but still highly efficient and better than existing algorithms. A strong theoretical result of ‘optimal rates’ would indicate the model’s potential for practical success when data is scarce and computational resources are limited.

Future Work#

The paper’s exploration of generalization in univariate ReLU networks opens several promising avenues for future research. A natural extension would involve generalizing the findings to multivariate settings, which would significantly increase the practical relevance of the theoretical results. This would require overcoming substantial technical challenges associated with higher dimensional function spaces and their complexities. Another important direction is to expand the model architecture, examining deeper or more complex network structures beyond the two-layer ReLU network to see if similar generalization properties hold. It is also crucial to investigate the impact of different optimization algorithms, comparing gradient descent with other techniques (e.g., Adam, SGD with momentum) to understand the extent to which the observed phenomena are algorithm-specific or reflect more general principles. Finally, a rigorous empirical study incorporating diverse datasets and problem settings is necessary to validate the theory’s applicability and limitations in real-world scenarios. This would provide valuable insights into the conditions under which stable minima reliably generalize and identify any potential weaknesses in the proposed theoretical framework.

More visual insights#

More on figures

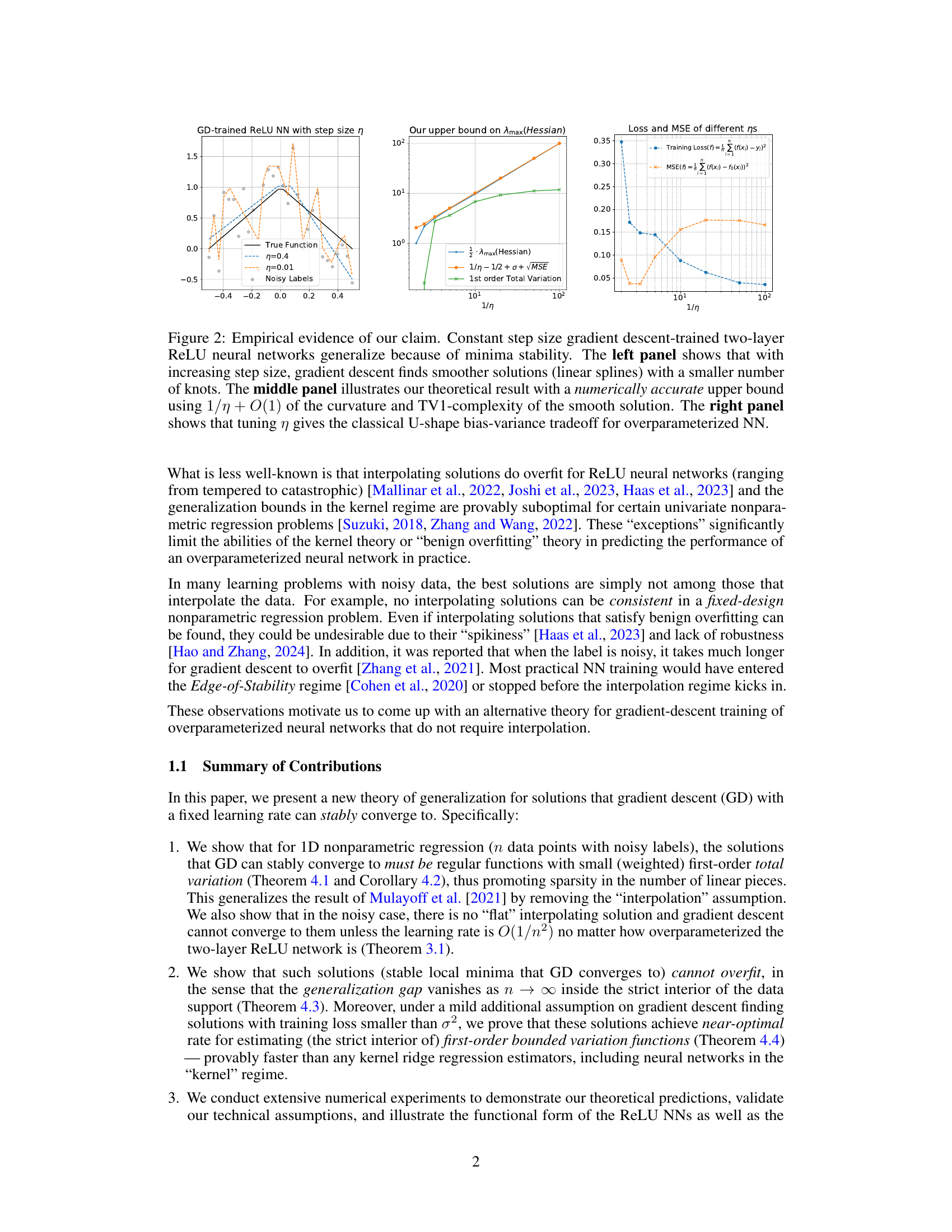

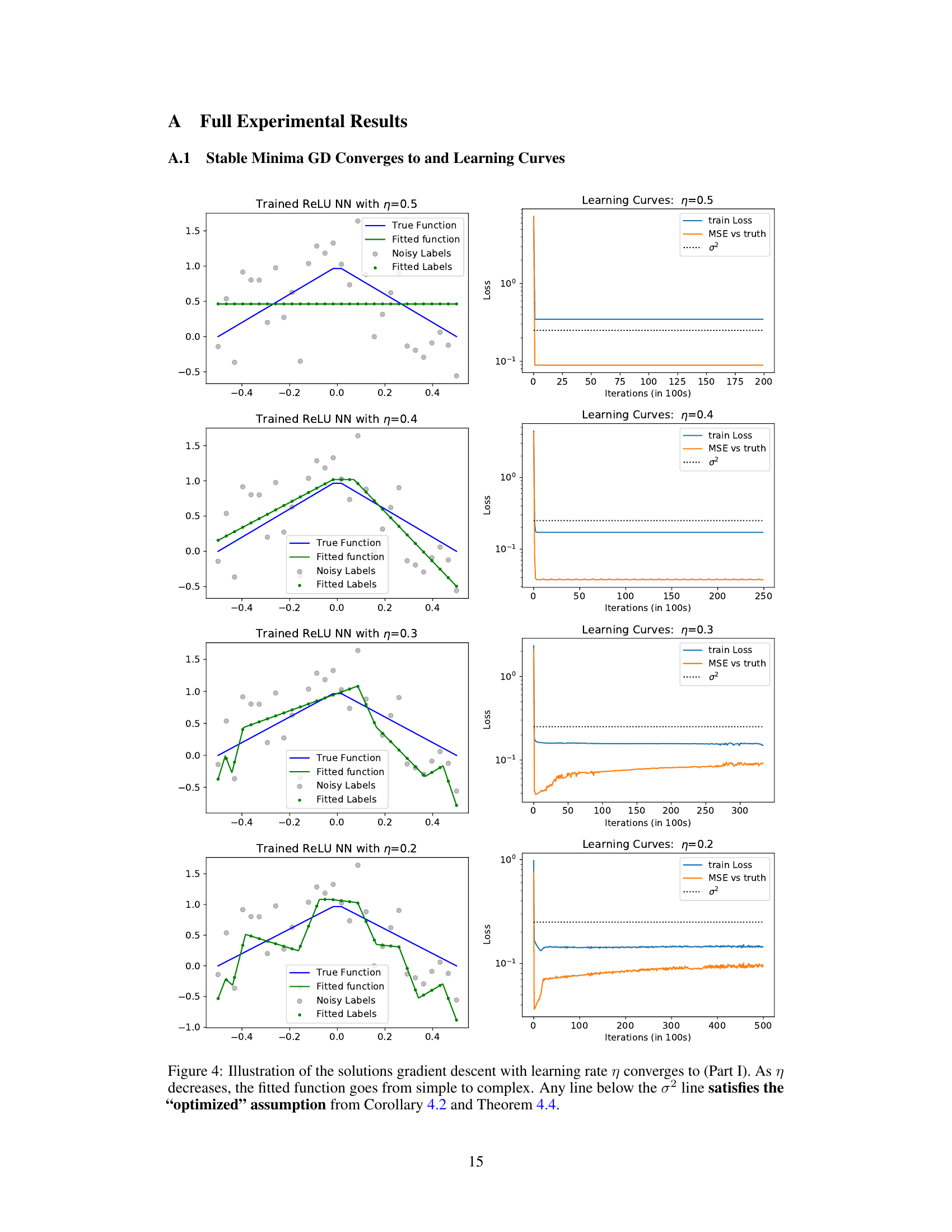

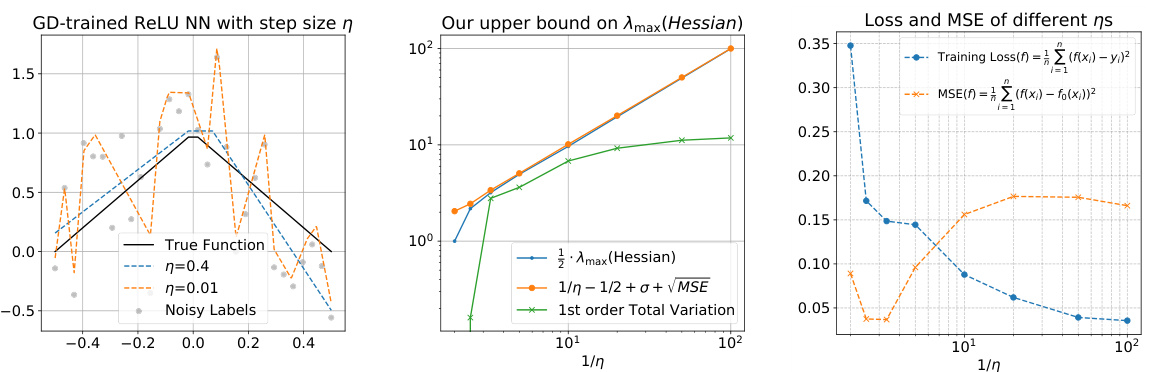

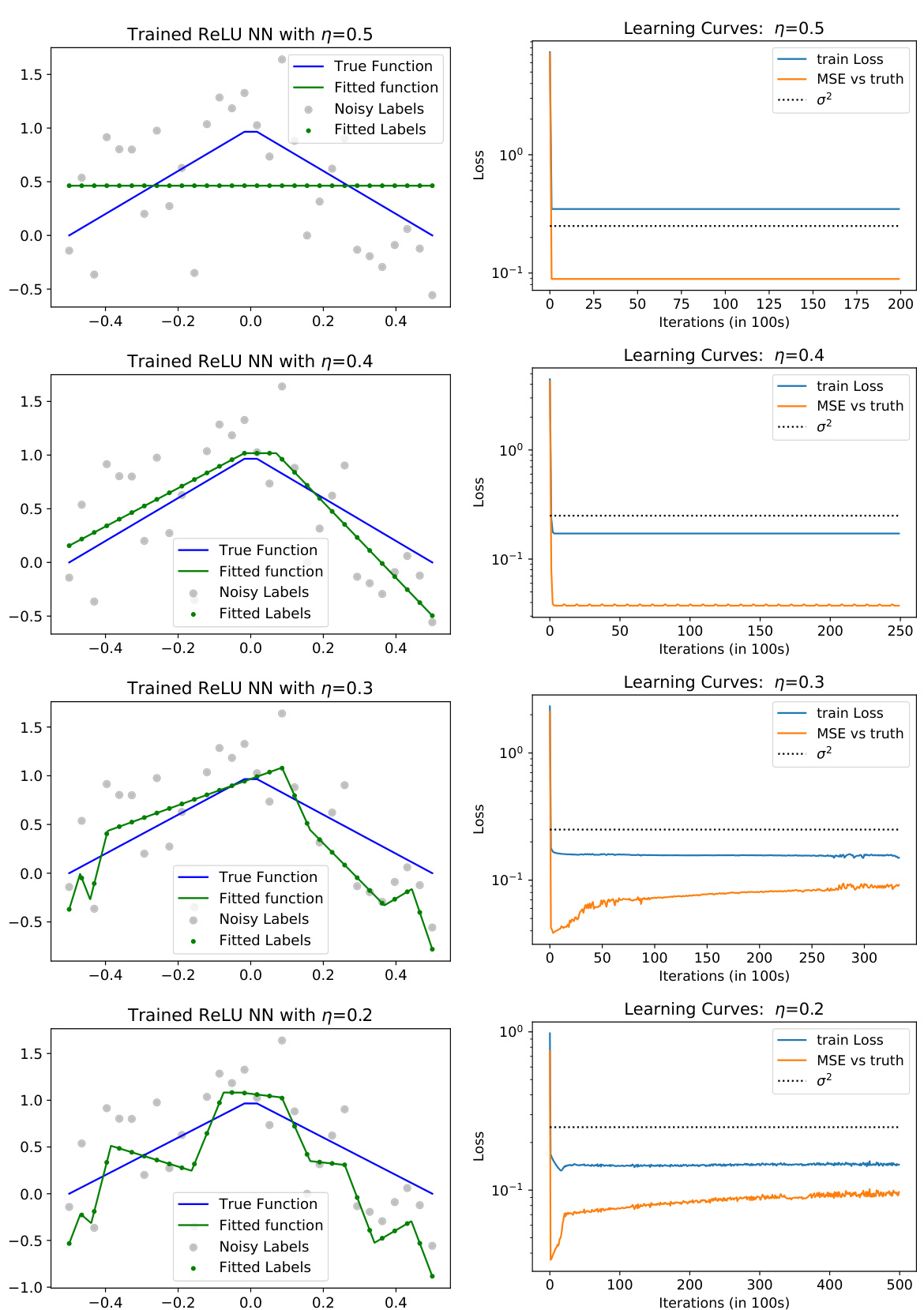

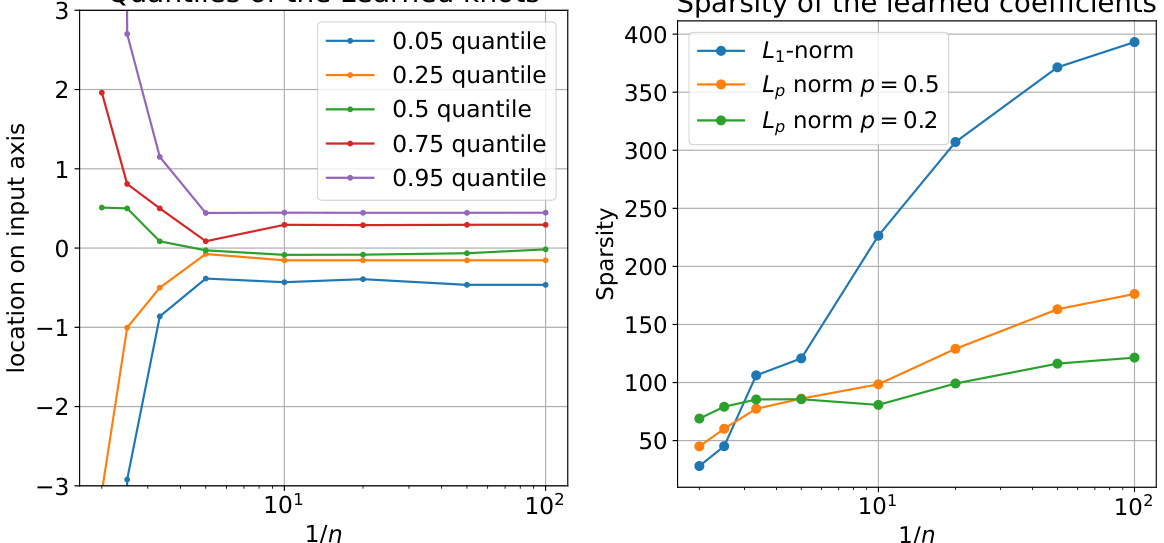

This figure demonstrates the empirical findings supporting the claim that stable minima in gradient descent training of two-layer ReLU networks generalize well. The left panel illustrates the relationship between step size (η) and solution smoothness, showing how larger step sizes lead to sparser, smoother solutions (represented as linear splines with fewer knots). The central panel validates the theoretical upper bound on the maximum eigenvalue of the Hessian, relating it to the step size and solution complexity (TV1). The right panel showcases the typical bias-variance tradeoff curve, demonstrating near-optimal performance through tuning the learning rate.

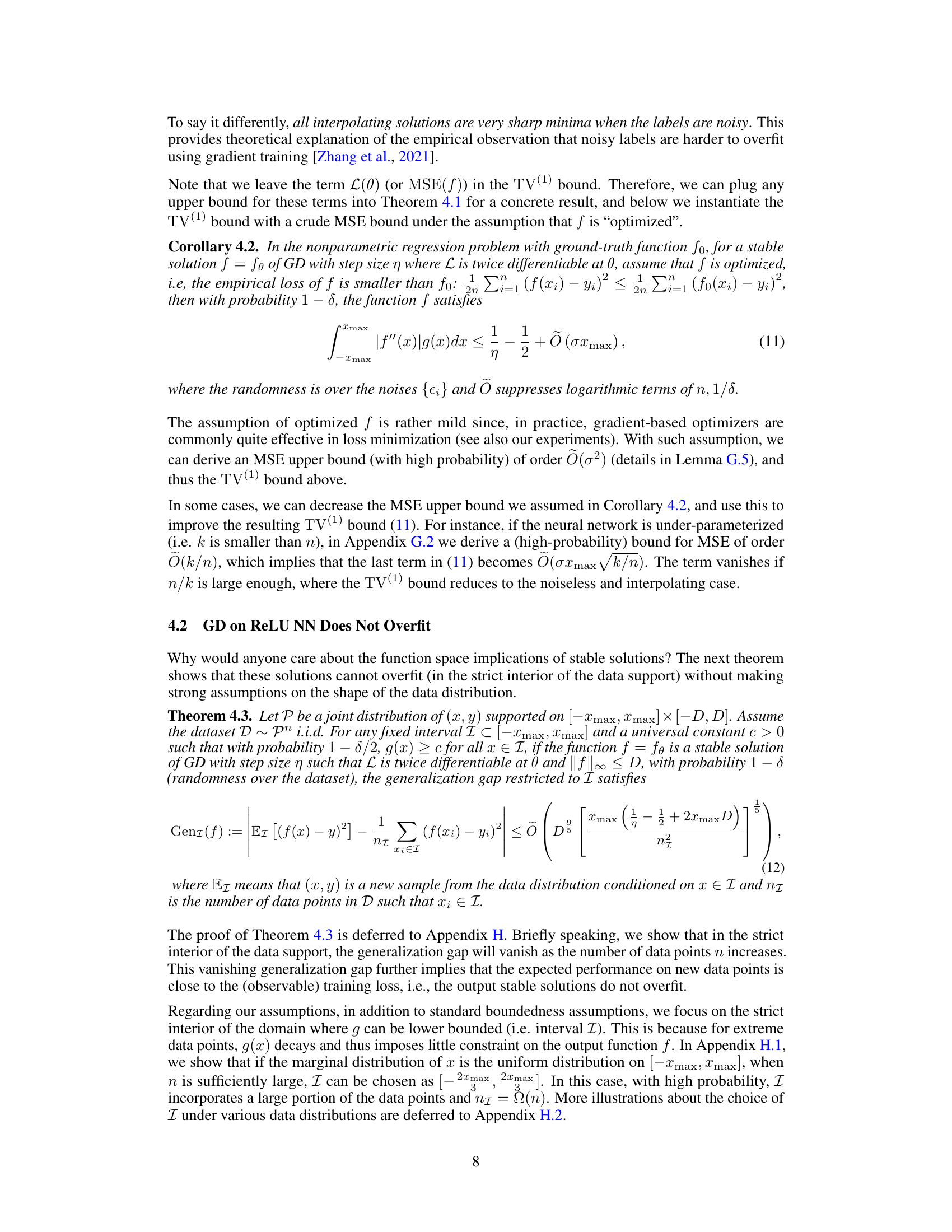

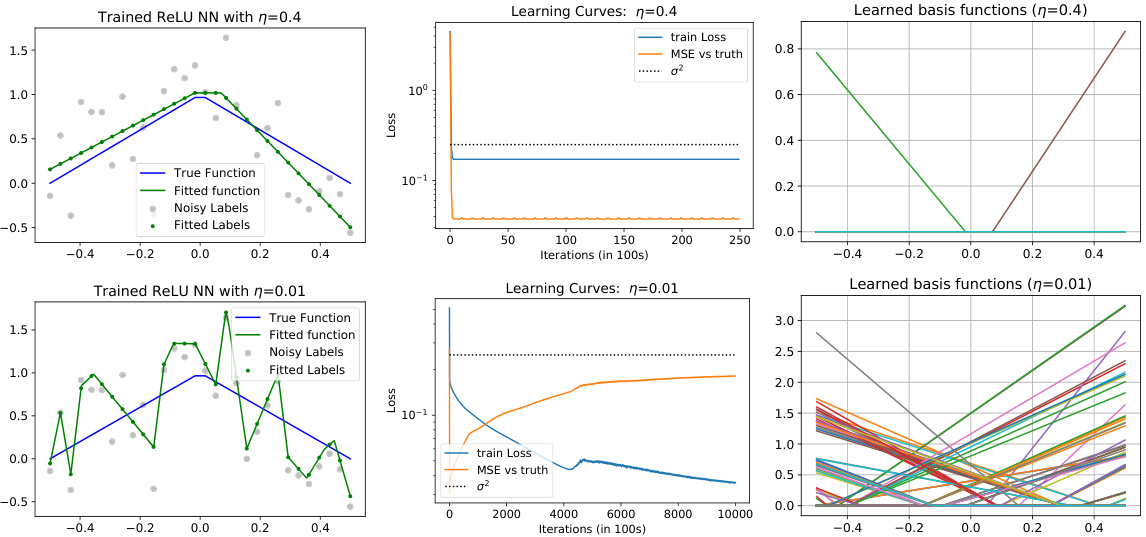

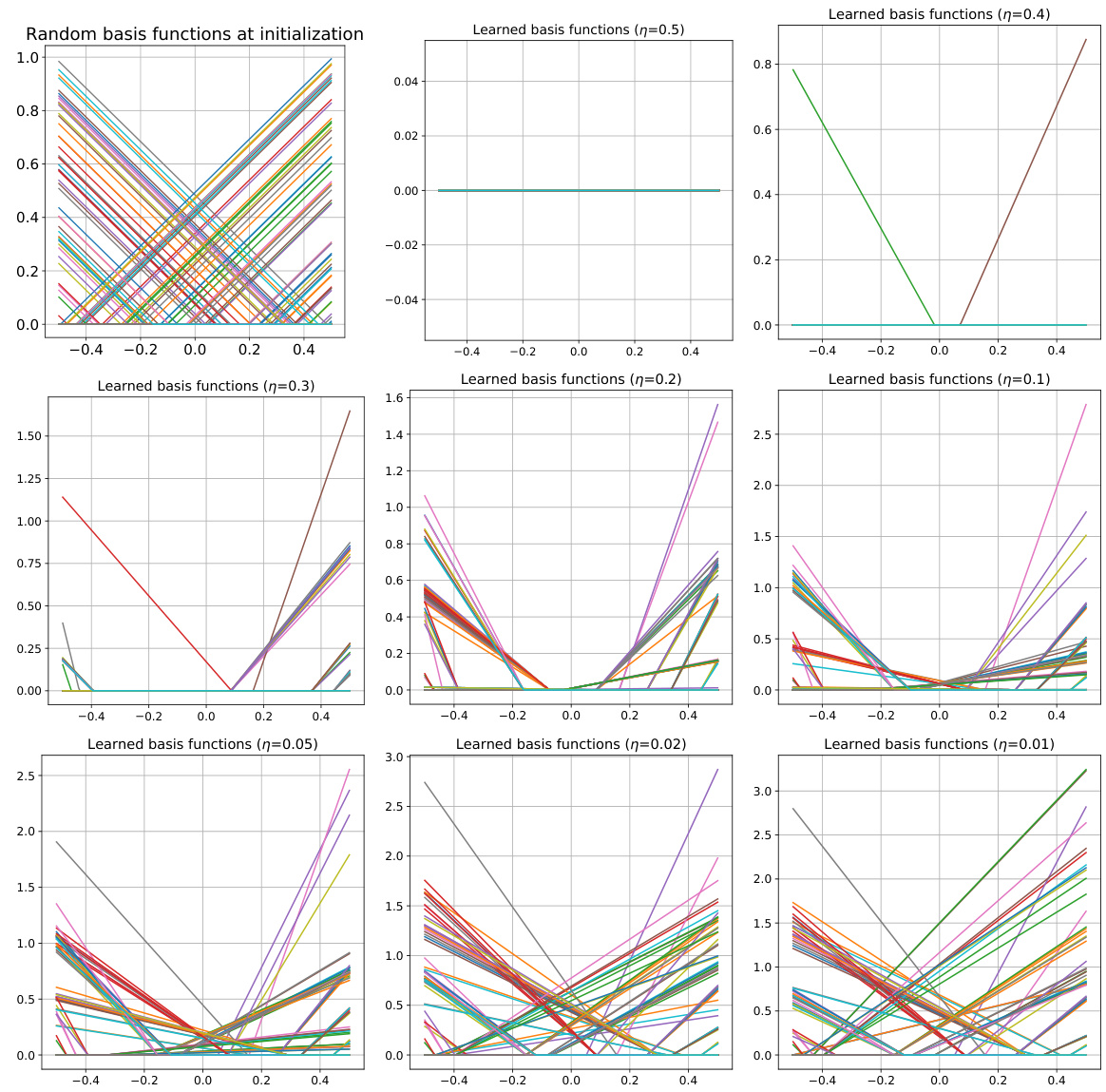

This figure shows the results of training a univariate ReLU neural network with different learning rates (η = 0.4 and η = 0.01). The top row illustrates the results for a large learning rate (η = 0.4), while the bottom row shows the results for a small learning rate (η = 0.01). Each row contains three subplots. The left subplot displays the trained neural network function along with the true function, noisy labels, and fitted labels. The middle subplot shows the learning curves, plotting the training loss and mean squared error (MSE) against the true function over iterations. The right subplot visualizes the learned basis functions of the neural network, offering insights into how the representation is learned at different learning rates. The visualization demonstrates how the choice of learning rate affects the learned model’s function, loss, and feature representations.

This figure shows the results of a numerical simulation using a two-layer ReLU neural network trained with gradient descent. The top row shows results for a large learning rate (η = 0.4), while the bottom row shows results for a small learning rate (η = 0.01). Each row consists of three subplots: (a) shows the learned neural network function compared to the true underlying function and noisy labels; (b) shows learning curves for training loss and mean squared error (MSE); (c) visualizes the learned basis functions of the neural network. The figure demonstrates that large learning rates lead to simpler functions, while small learning rates lead to overfitting.

This figure shows the results of training a univariate ReLU neural network with different learning rates. The top row shows the results for a large learning rate (η = 0.4), while the bottom row shows the results for a small learning rate (η = 0.01). For each learning rate, the figure shows the trained neural network function, the learning curves (training loss and MSE vs. truth), and the learned basis functions. The results demonstrate that large learning rates lead to simpler, smoother solutions, while smaller learning rates lead to more complex, less smooth solutions that overfit to the noisy data.

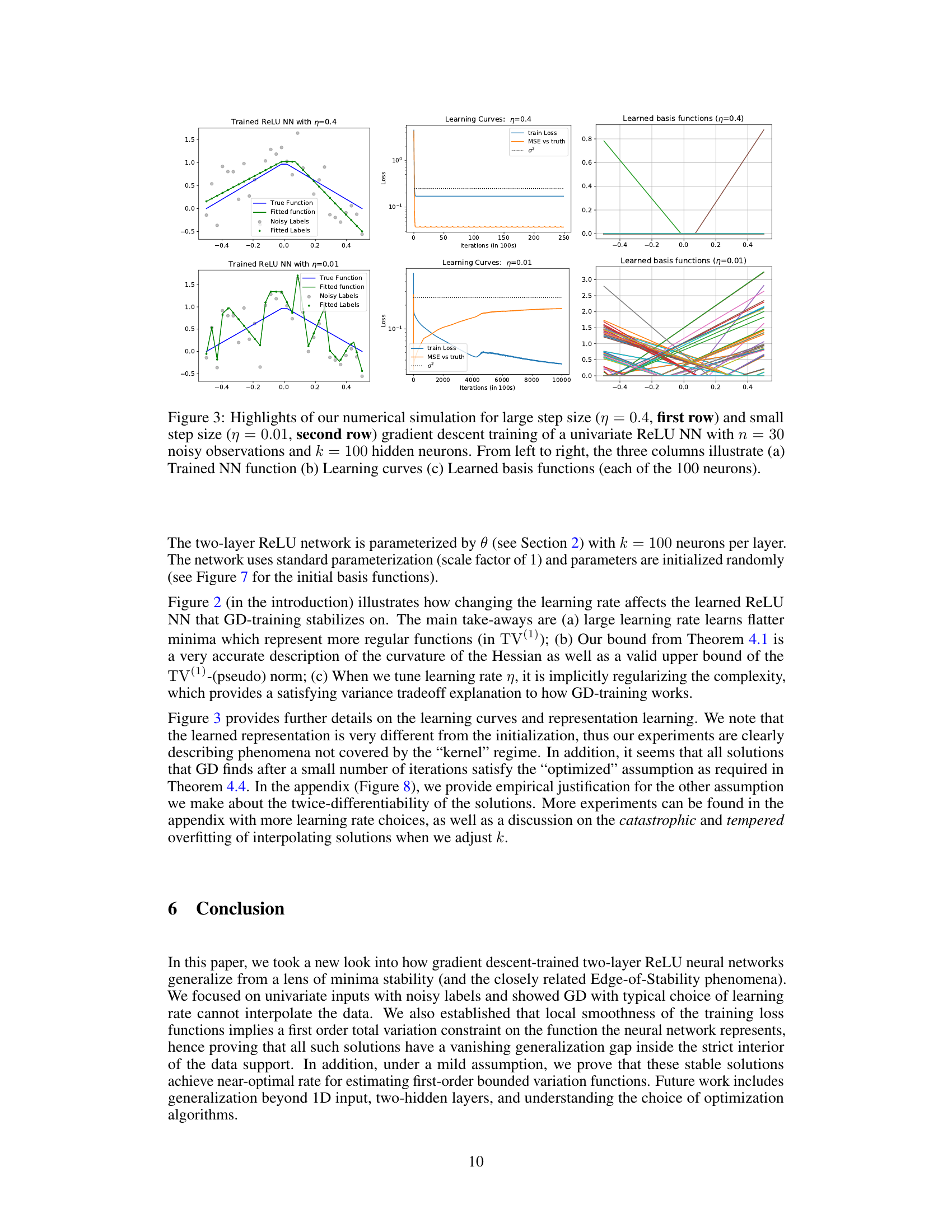

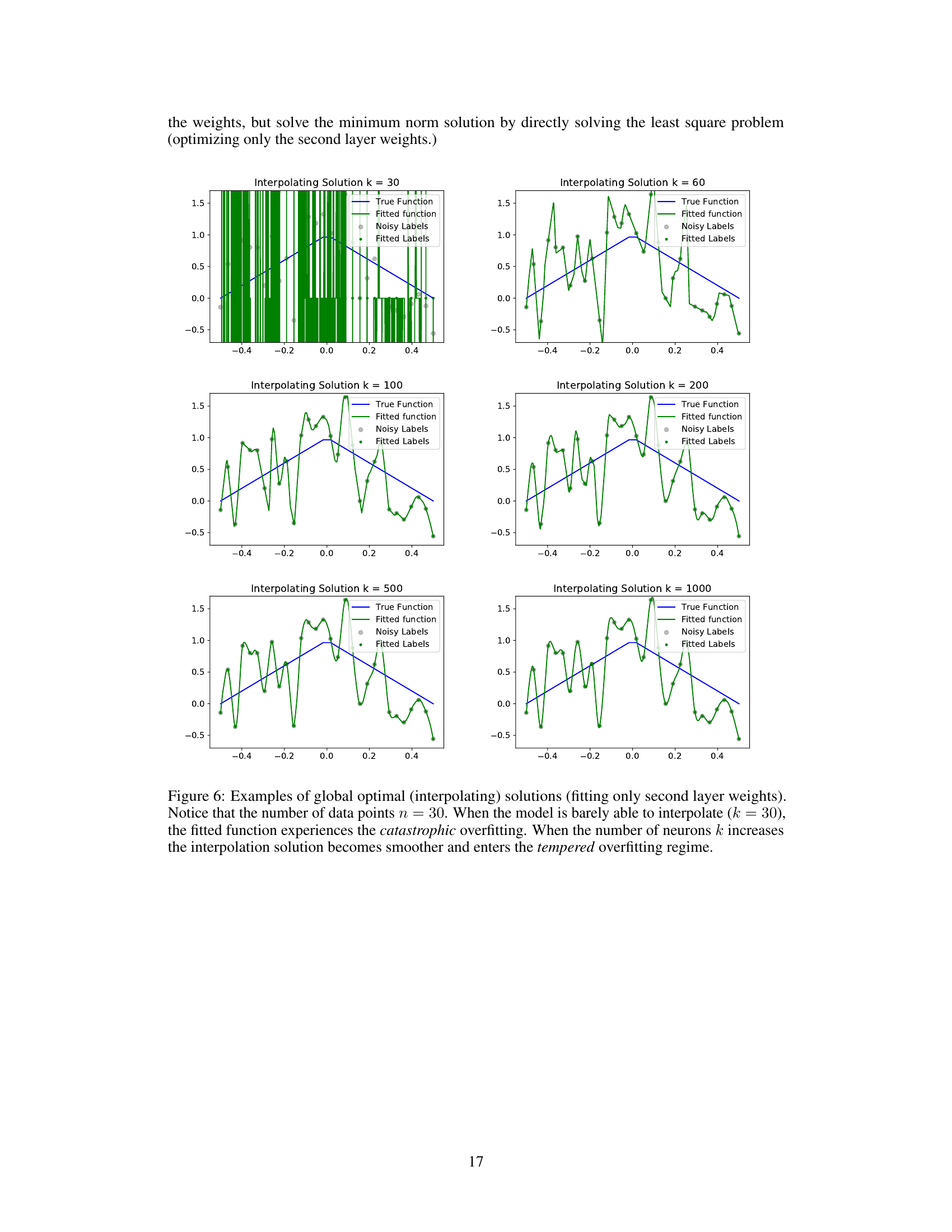

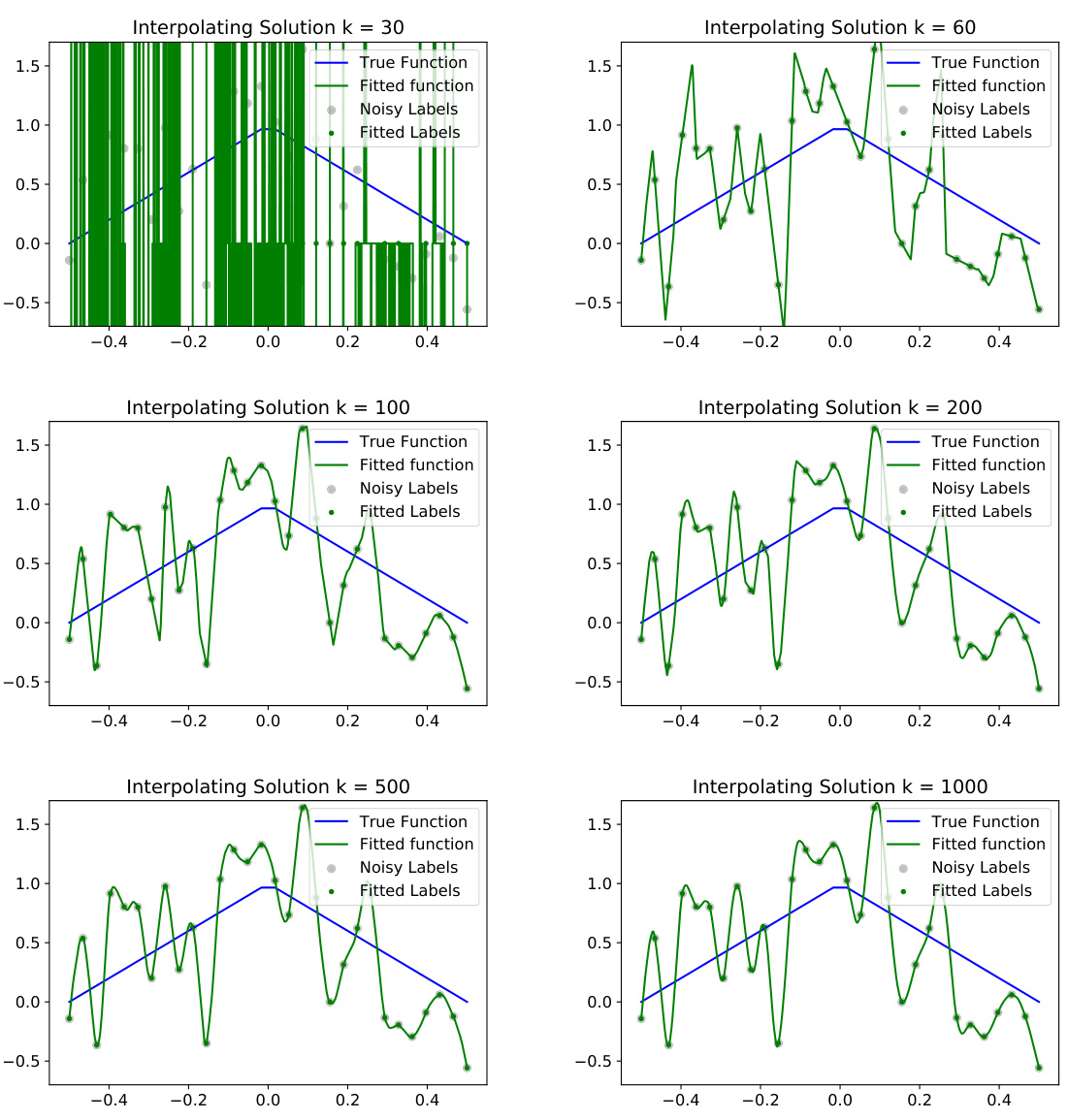

This figure empirically demonstrates the effect of model capacity on the ability of an interpolating solution to generalize. By keeping the number of data points fixed at 30 but increasing the number of neurons in the hidden layer (k), the plots show how the interpolating solutions transition from catastrophic overfitting (high variance, poor generalization) for small k to tempered overfitting (less variance, improved generalization) for larger k. The smooth blue line represents the true function, the green line is the learned model’s output, and the dots show the noisy training labels.

This figure shows the results of a numerical simulation of training a univariate ReLU neural network with gradient descent using two different learning rates (η = 0.4 and η = 0.01). The top row shows the results for the large learning rate (η = 0.4), and the bottom row shows the results for the small learning rate (η = 0.01). Each row shows three plots: (a) trained NN function, (b) learning curves, and (c) learned basis functions. The plots demonstrate the effects of learning rate on the trained function’s smoothness, convergence speed, and the nature of the learned basis functions.

This figure shows the results of a numerical simulation with different learning rates (η = 0.4 and η = 0.01) for training a univariate ReLU neural network (NN) with noisy labels. The left column displays the trained NN function, showing how it fits to the noisy data. The middle column presents the learning curves of the training loss and mean squared error (MSE), which illustrate the model’s training process. The right column visualizes the learned basis functions of the NN, providing insight into how the network represents learned features. The comparison of results with different learning rates indicates the impact of learning rate on model generalization and implicit sparsity.

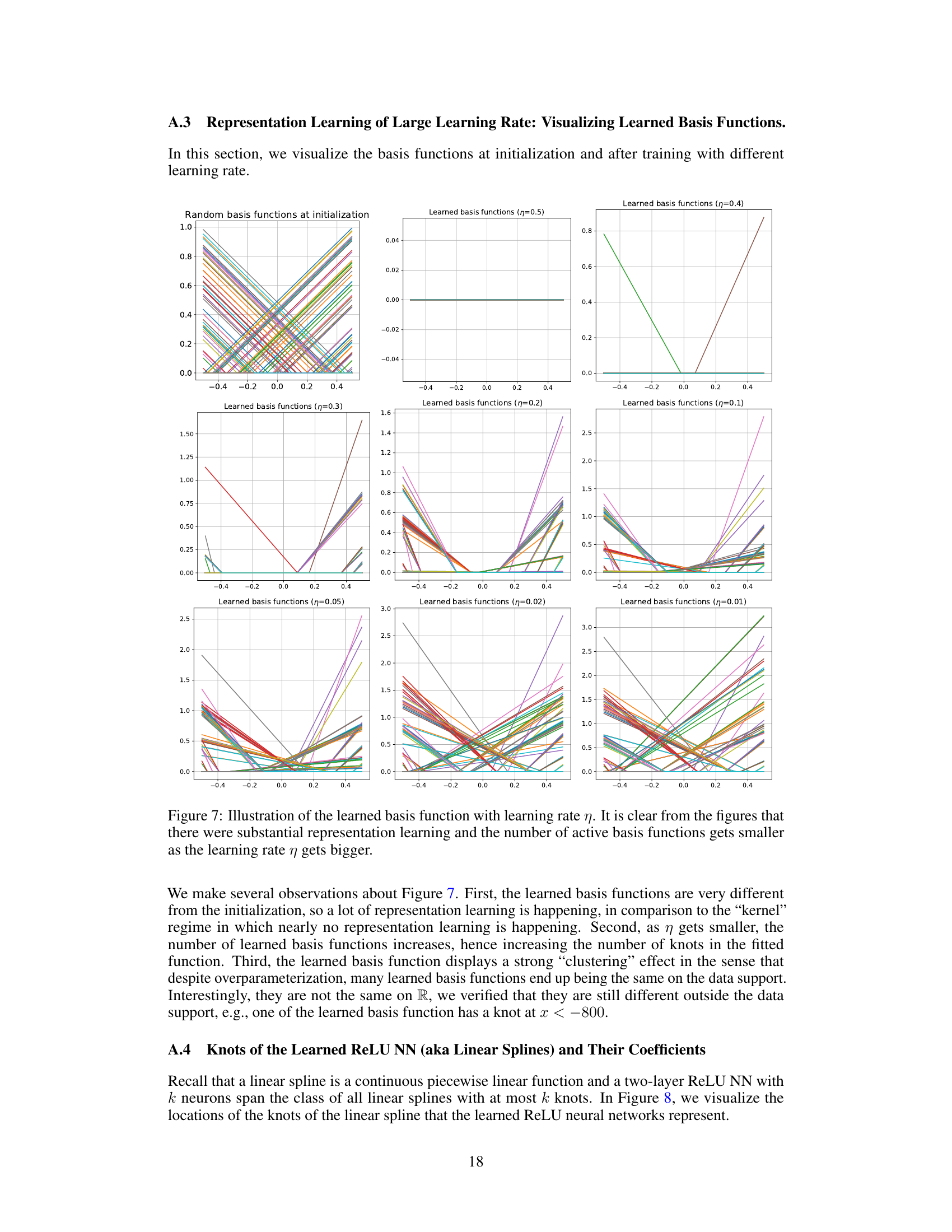

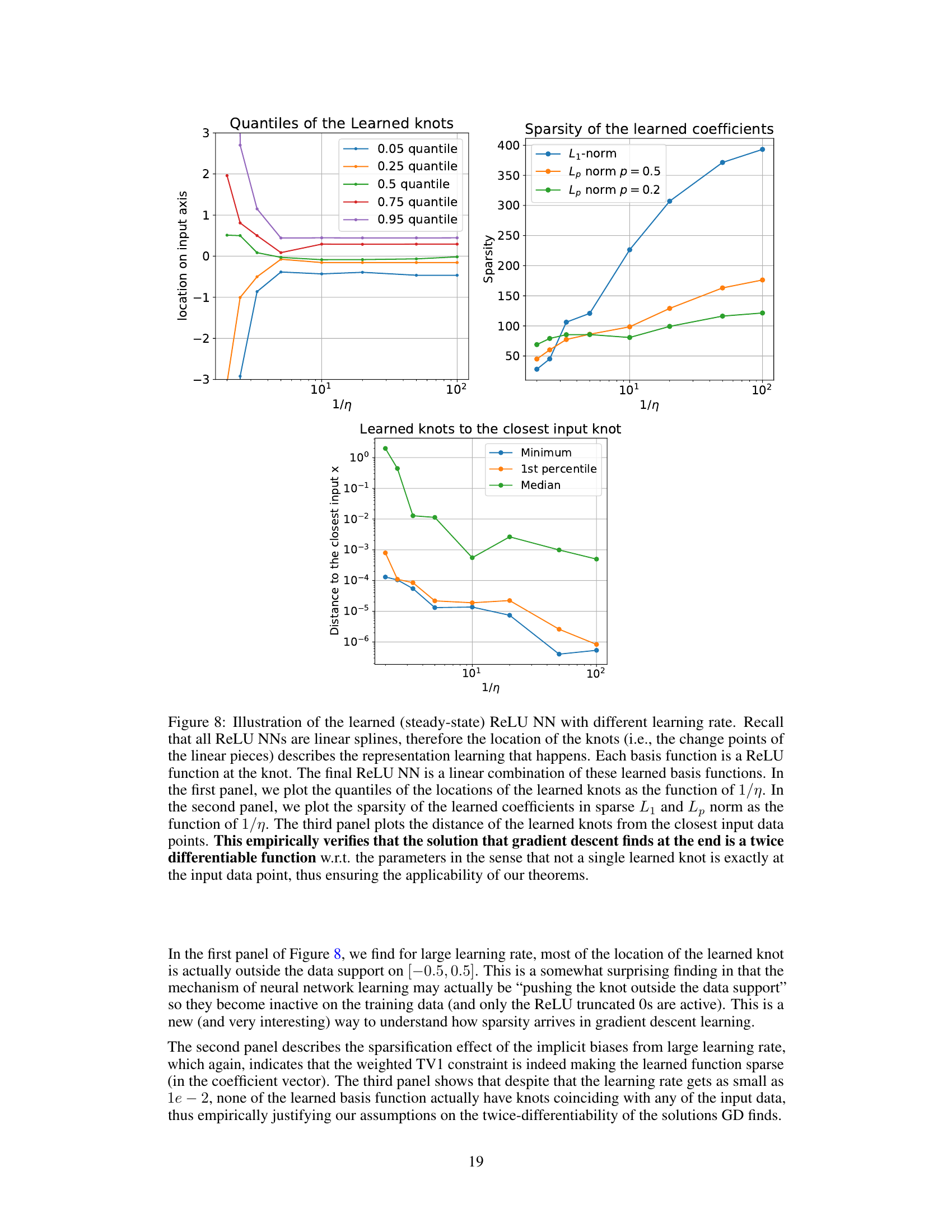

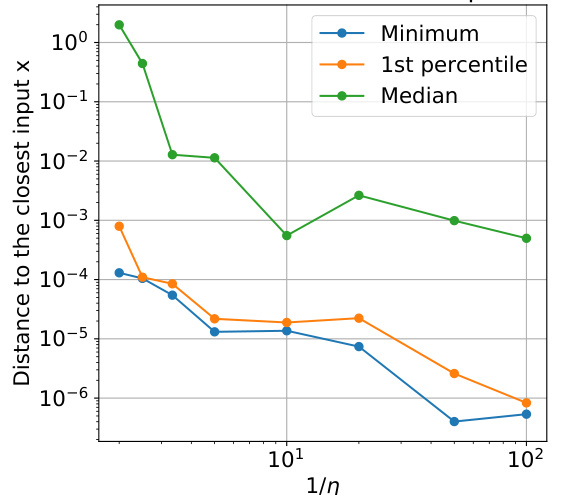

This figure empirically validates the theoretical claims of the paper by visualizing the learned basis functions of ReLU neural networks trained with gradient descent using different learning rates. The three subplots show the quantiles of learned knot locations, the sparsity of learned coefficients, and the distance of learned knots to the closest input knot, all as functions of the inverse learning rate (1/η). The results demonstrate the implicit regularization effect of large learning rates, showing that they lead to sparser solutions and avoid overfitting by preventing knots from being placed exactly on the data points.

This figure displays the results of a numerical simulation comparing the effects of large versus small learning rates (η) on the training of a univariate ReLU neural network. The top row shows results for η = 0.4, while the bottom row shows results for η = 0.01. Three columns show (a) the trained neural network function, (b) the learning curves (training loss and MSE against the ground truth), and (c) the learned basis functions for each of the 100 neurons. The experiment highlights how different learning rates impact the smoothness of the solution found, showing that a large learning rate produces smoother solutions while a small learning rate leads to less smooth, potentially overfit solutions.

Full paper#