↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning methods lack interpretability, making it hard to assess their performance. Researchers often compare models using a predictiveness criterion, but this approach suffers from a ‘degeneracy’ issue: even when two models perform equally, the test statistics may not have a standard distribution, leading to unreliable conclusions. This is especially problematic for black-box models such as deep learning and random forests.

This paper introduces ‘Zipper’, a new method to address this degeneracy. Zipper strategically overlaps testing data splits, creating a ‘slider’ parameter to control the overlap amount. This clever technique produces a test statistic with a standard distribution even when models perform equally well, while maintaining high power to detect differences. Through simulations and real-world examples, the authors show that Zipper provides reliable and more powerful results than other existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on algorithm-agnostic inference and goodness-of-fit testing. It directly addresses a significant limitation (degeneracy) in existing methods, improving the reliability and power of such tests. This opens avenues for more reliable model comparisons and variable importance assessments across diverse machine learning algorithms, advancing algorithm-agnostic inference significantly.

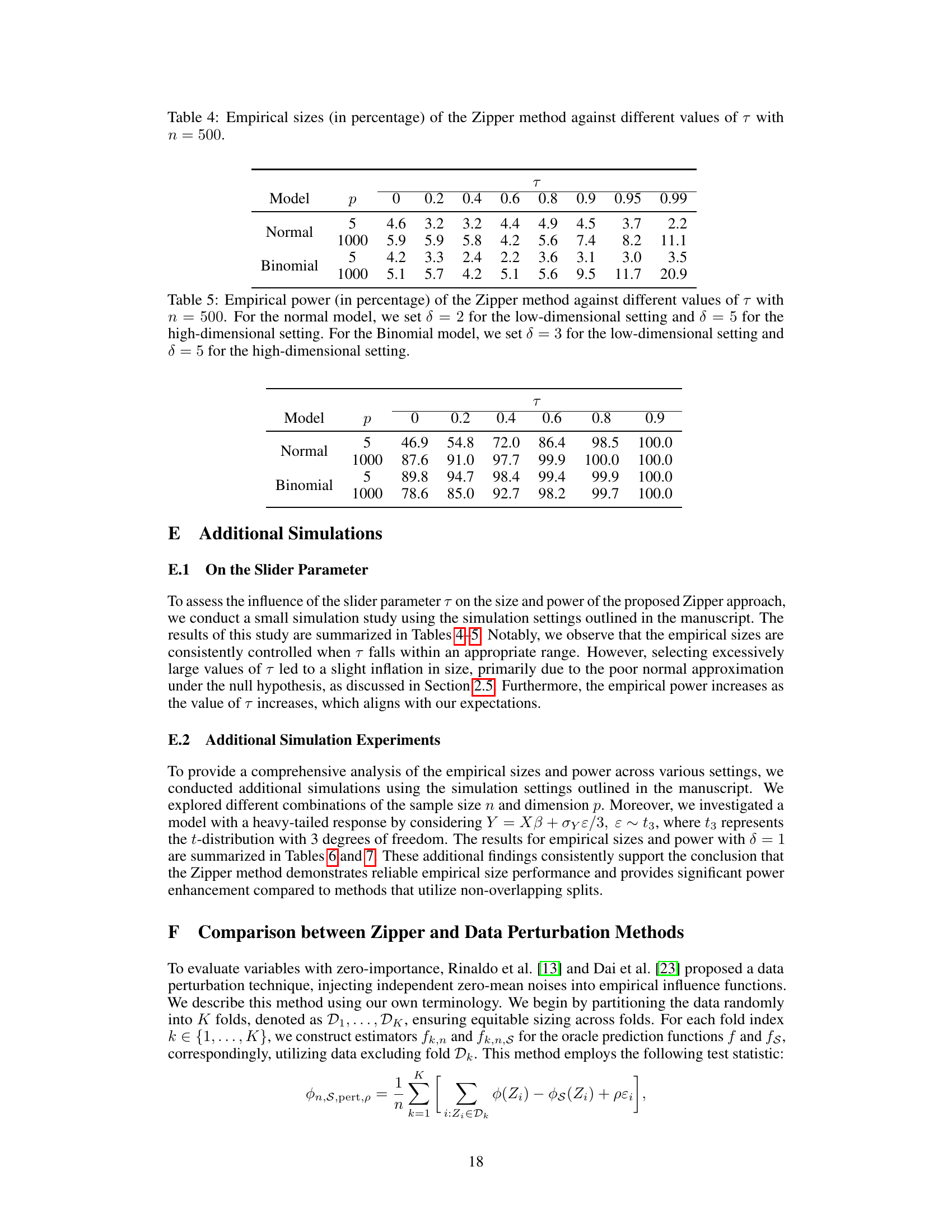

Visual Insights#

The figure illustrates how the Zipper device works on the kth fold of testing data. The data fold Dk is divided into two splits, Dk,A and Dk,B, with an overlapping part Dk,o. The parameter τ controls the proportion of the overlap. The predictiveness criteria C are evaluated on Dk,o, Dk,a (Dk,A \ Dk,o), and Dk,b (Dk,B \ Dk,o). When τ = 0, there is no overlap, representing the standard sample splitting approach. When τ = 1, there is complete overlap, which is known to cause degeneracy. The Zipper mechanism uses the slider parameter τ to control the amount of overlap and thus mitigate the degeneracy issue.

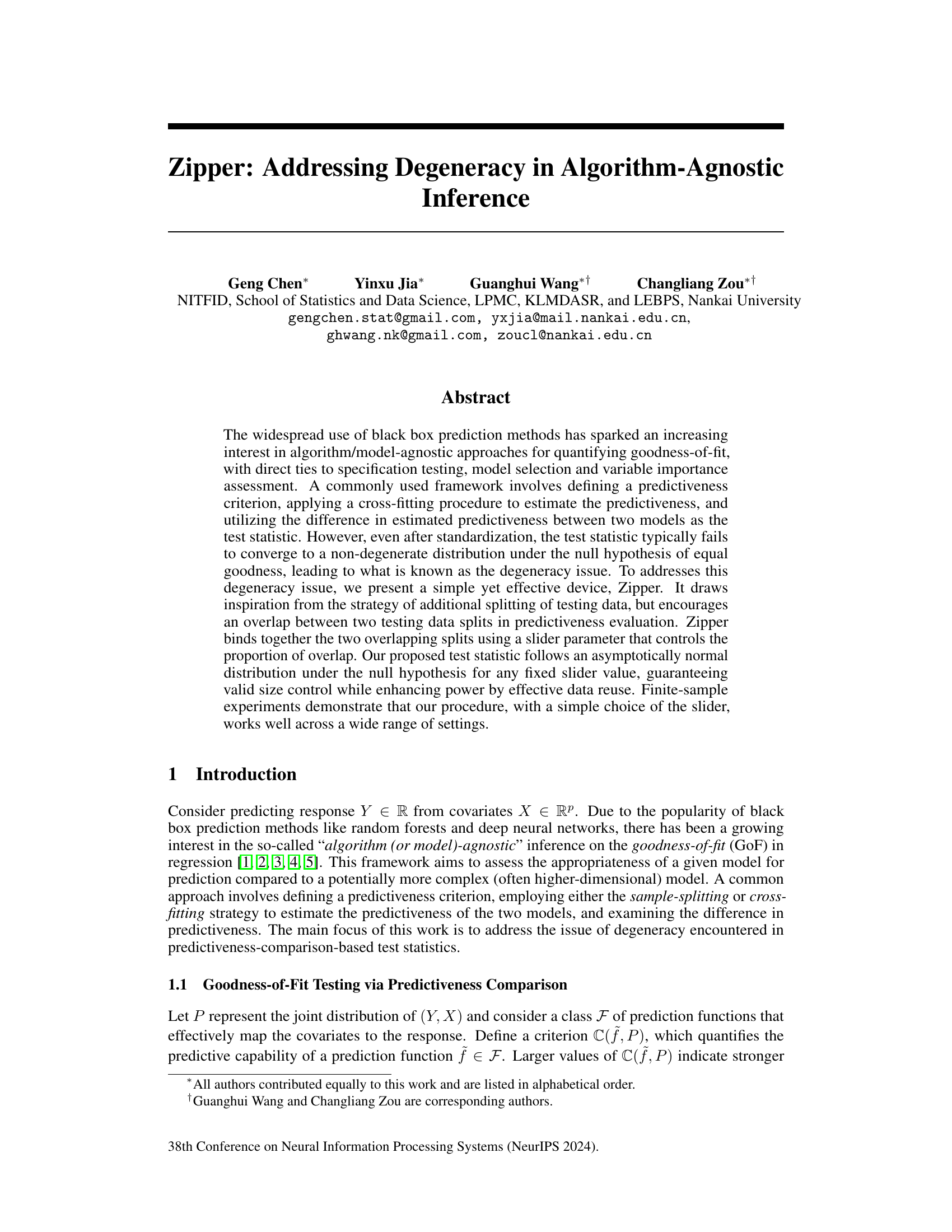

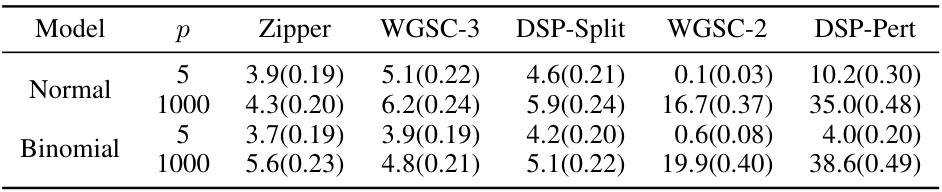

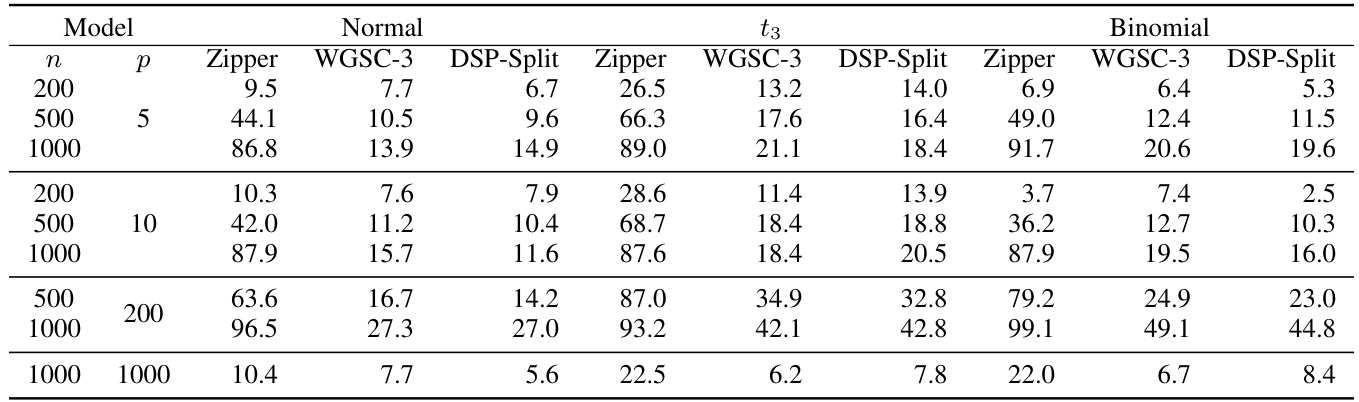

This table presents the empirical Type I error rates (size) of several goodness-of-fit testing procedures, including the proposed Zipper method and several benchmark methods. The results are shown for both normal and binomial response models, and for low-dimensional (p=5) and high-dimensional (p=1000) settings. Standard deviations are included to show the variability of the estimates.

In-depth insights#

Degeneracy in GoF#

The concept of ‘degeneracy in Goodness-of-Fit (GoF)’ testing arises when the test statistic, designed to measure the difference in predictive power between models, fails to follow a well-behaved distribution under the null hypothesis (i.e., both models are equally good). This leads to unreliable inference, making it difficult to distinguish between truly different models and those that simply appear different due to random chance. The paper highlights that this problem emerges due to the estimation procedures used (cross-fitting, sample-splitting), where the estimated predictiveness often collapses to zero under the null. This degeneracy issue is particularly concerning in algorithm-agnostic GoF settings, where the nature of the underlying algorithm adds further complexity to the analysis. To overcome degeneracy, methods that employ additional data splitting or noise perturbation are proposed. However, these approaches often come with reduced statistical power or a reliance on ad-hoc choices. The proposed ‘Zipper’ method tackles this issue by strategically encouraging overlap between data splits, which improves statistical power while maintaining the asymptotic normality needed for reliable inference. This is accomplished by introducing a ‘slider’ parameter to control the extent of this overlap, offering a flexible approach to achieve optimal results.

Zipper’s Mechanism#

The core of Zipper’s mechanism lies in its innovative approach to data splitting. Unlike traditional methods that use independent test sets, Zipper cleverly introduces an overlapping region between two data splits. This overlapping region, controlled by a slider parameter, allows for more efficient data utilization. By carefully weighting the overlapping and non-overlapping portions, Zipper effectively combines information from both splits. This strategy is crucial for addressing the degeneracy problem often encountered in algorithm-agnostic inference, where standard test statistics fail to converge to a non-degenerate distribution under the null hypothesis. The key advantage is improved power without sacrificing the test’s ability to control type I error. The slider parameter provides flexibility, allowing researchers to balance the trade-off between power and the risk of degeneracy. In essence, Zipper’s mechanism provides a robust and efficient way to extract predictive information from the data.

Asymptotic Linearity#

The section on Asymptotic Linearity is crucial because it establishes the foundation for the statistical validity of the proposed Zipper test. It demonstrates that under certain conditions, the test statistic’s behavior is asymptotically linear, meaning its large-sample distribution can be approximated by a normal distribution. This is essential for constructing valid hypothesis tests and confidence intervals, enabling reliable inferences about predictive capability differences. The asymptotic linearity result hinges on specific conditions relating to the estimator’s convergence rate, smoothness of the predictiveness measure, and the properties of the prediction function classes. The proof likely relies on sophisticated techniques from empirical process theory to handle the complexity of algorithm-agnostic prediction methods and data splitting. This rigorous mathematical justification is vital for ensuring the Zipper test maintains its type I error control and possesses adequate power for detecting real differences, which is a key advantage over existing methods that suffer from degeneracy issues under the null hypothesis.

Power & Efficiency#

The power and efficiency of a statistical method are crucial considerations. Power refers to the method’s ability to correctly reject a false null hypothesis, while efficiency relates to how much data is needed to achieve a certain level of power. In hypothesis testing, a high-power method is desirable because it minimizes the probability of Type II errors (failing to reject a false null hypothesis). However, achieving high power often requires larger sample sizes, which can be costly and time-consuming. Efficiency becomes important when balancing the need for power with resource constraints. A highly efficient method can achieve the same power with smaller sample sizes compared to a less efficient method, making it a more practical choice. The interplay between power and efficiency is a key factor in selecting appropriate statistical methods for specific research questions, and careful consideration of both is essential for sound data analysis.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending Zipper to handle more complex data structures such as time series or network data would significantly broaden its applicability. Investigating the optimal selection of the slider parameter

τ through theoretical analysis or adaptive methods could further improve performance. A deeper understanding of the relationship between Zipper and other variable importance measures, such as Shapley values, would enrich the framework and provide valuable insights into its strengths and limitations. Finally, exploring alternative predictiveness criteria and investigating the robustness of Zipper under various distributional assumptions would enhance its generality and reliability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

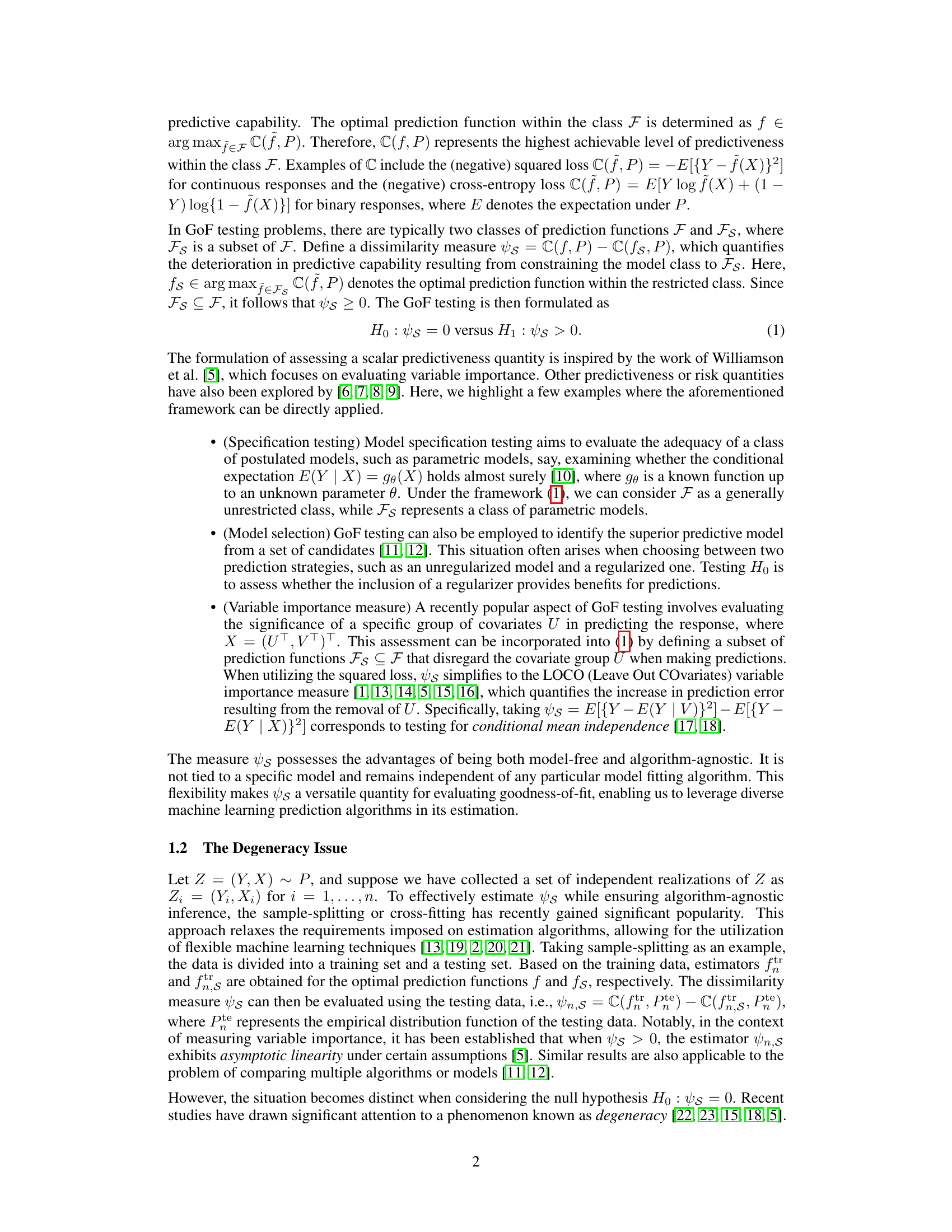

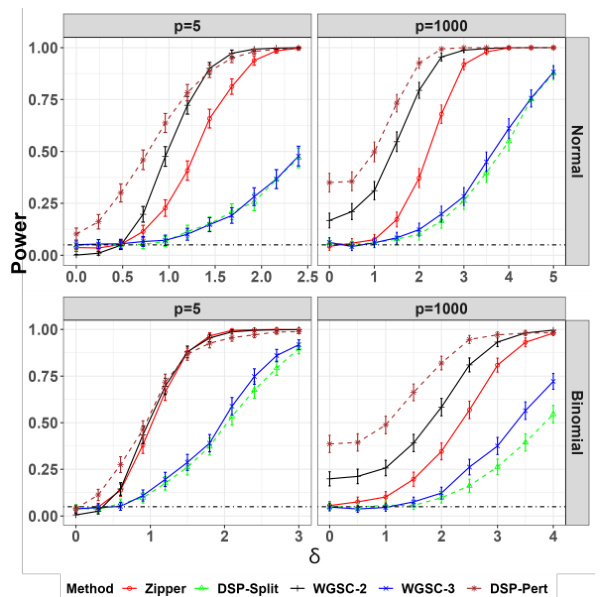

This figure compares the empirical power of six different variable importance testing methods (Zipper, WGSC-3, DSP-Split, WGSC-2, WGSC-3, and DSP-Pert) across two different sample sizes (n=500) and dimensions (p=5, 1000). The x-axis represents the magnitude of variable relevance (δ), and the y-axis represents the empirical power of each method. The figure shows that the Zipper method consistently outperforms other methods in terms of power, especially in higher dimensions. The dot-dashed line indicates the significance level (α = 0.05).

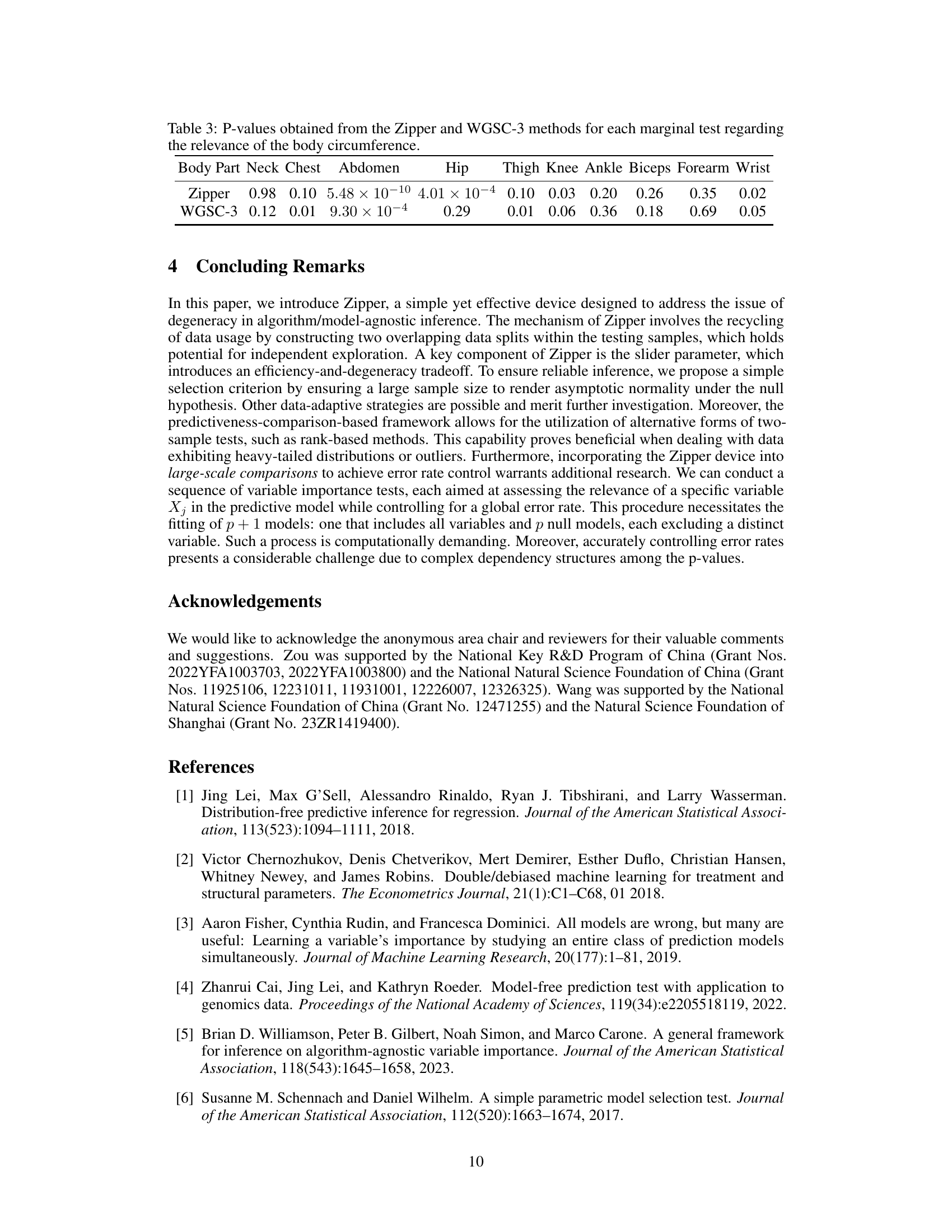

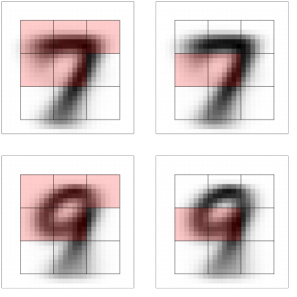

This figure visually presents a comparison of the Zipper method and the WGSC-3 method in identifying important regions for distinguishing between the digits 7 and 9 in the MNIST handwritten digit dataset. Each image is divided into nine regions. The Zipper method (left column) highlights regions (in red) deemed significant for distinguishing the two digits, while the WGSC-3 method (right column) shows its respective findings. The comparison suggests that Zipper identifies more key regions.

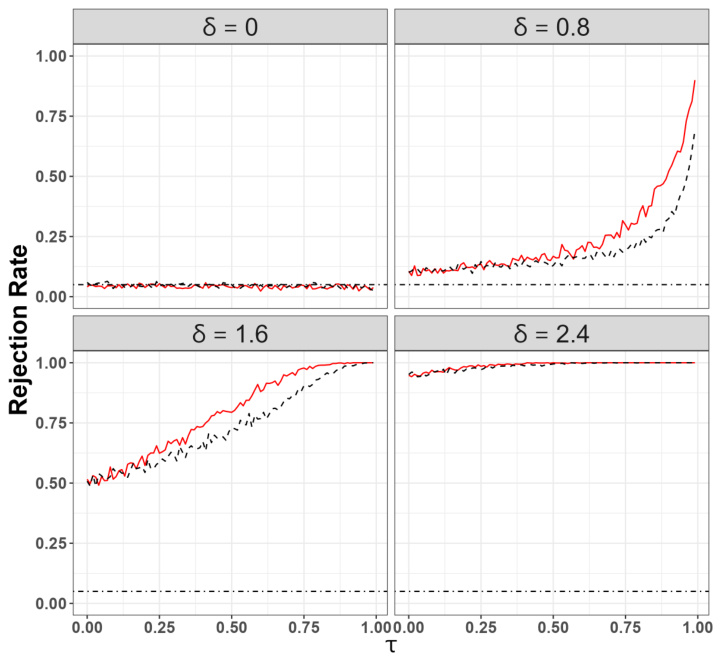

This figure shows the empirical size and power comparison between the Zipper method and the data perturbation method. The x-axis represents the slider parameter (τ) in the Zipper method, which controls the overlap between two data splits. The y-axis represents the rejection rate (power). Different lines represent different values of δ which reflects the magnitude of variable importance in the model. The dot-dashed horizontal line indicates the significance level (α = 0.05). The figure demonstrates that the Zipper method generally shows improved power compared to the data perturbation method, particularly when τ is not close to 0 or 1, while maintaining a valid size.

More on tables

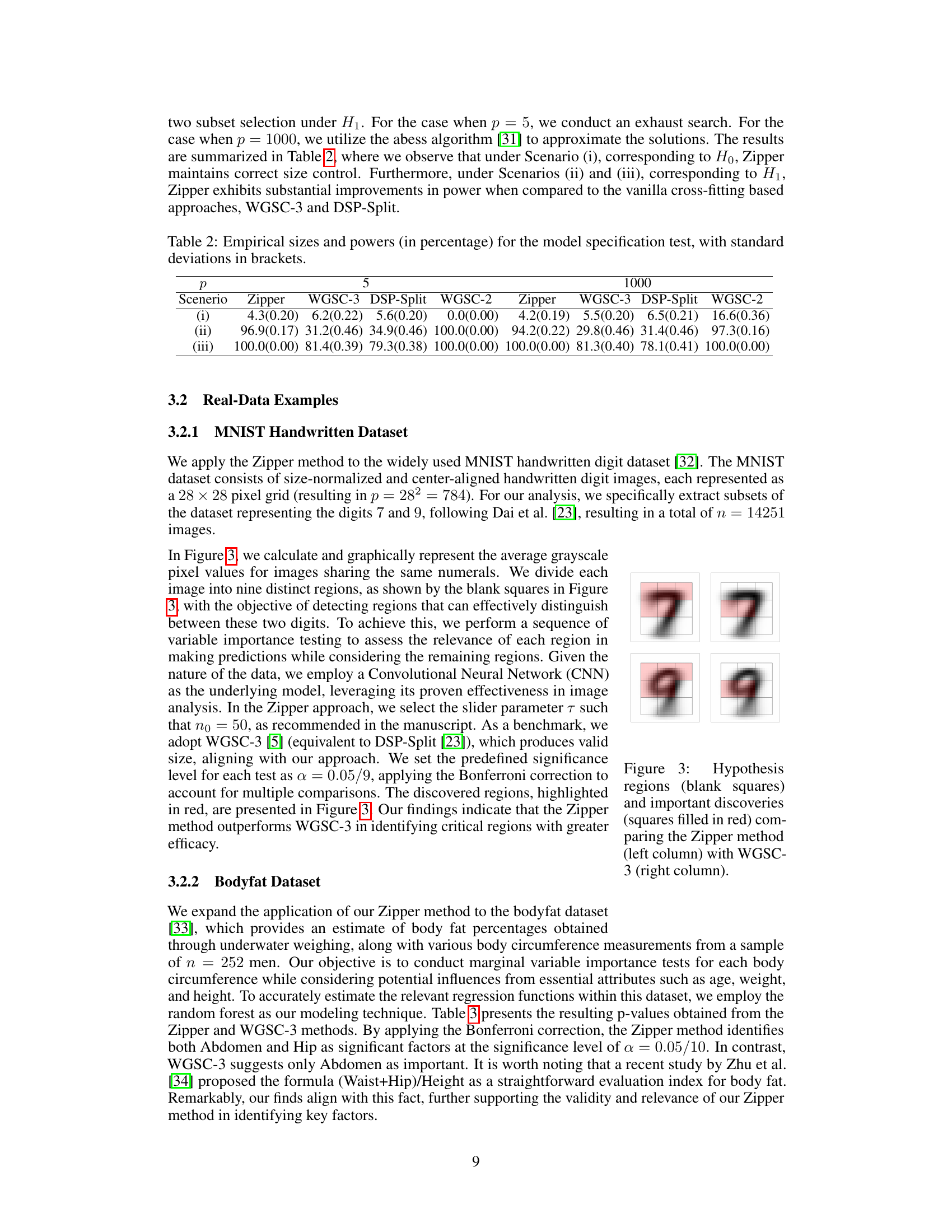

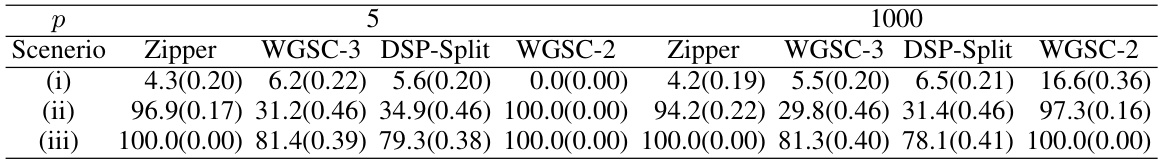

This table presents the empirical sizes and powers of four different testing procedures (Zipper, WGSC-3, DSP-Split, and WGSC-2) for a model specification test. The empirical size represents the percentage of times the null hypothesis (Ho) is rejected when it is actually true, while the empirical power represents the percentage of times the alternative hypothesis (H1) is correctly rejected. Three different scenarios (i), (ii), and (iii) are considered, each corresponding to a different configuration of the model parameters. The results are shown for both low-dimensional (p=5) and high-dimensional (p=1000) settings.

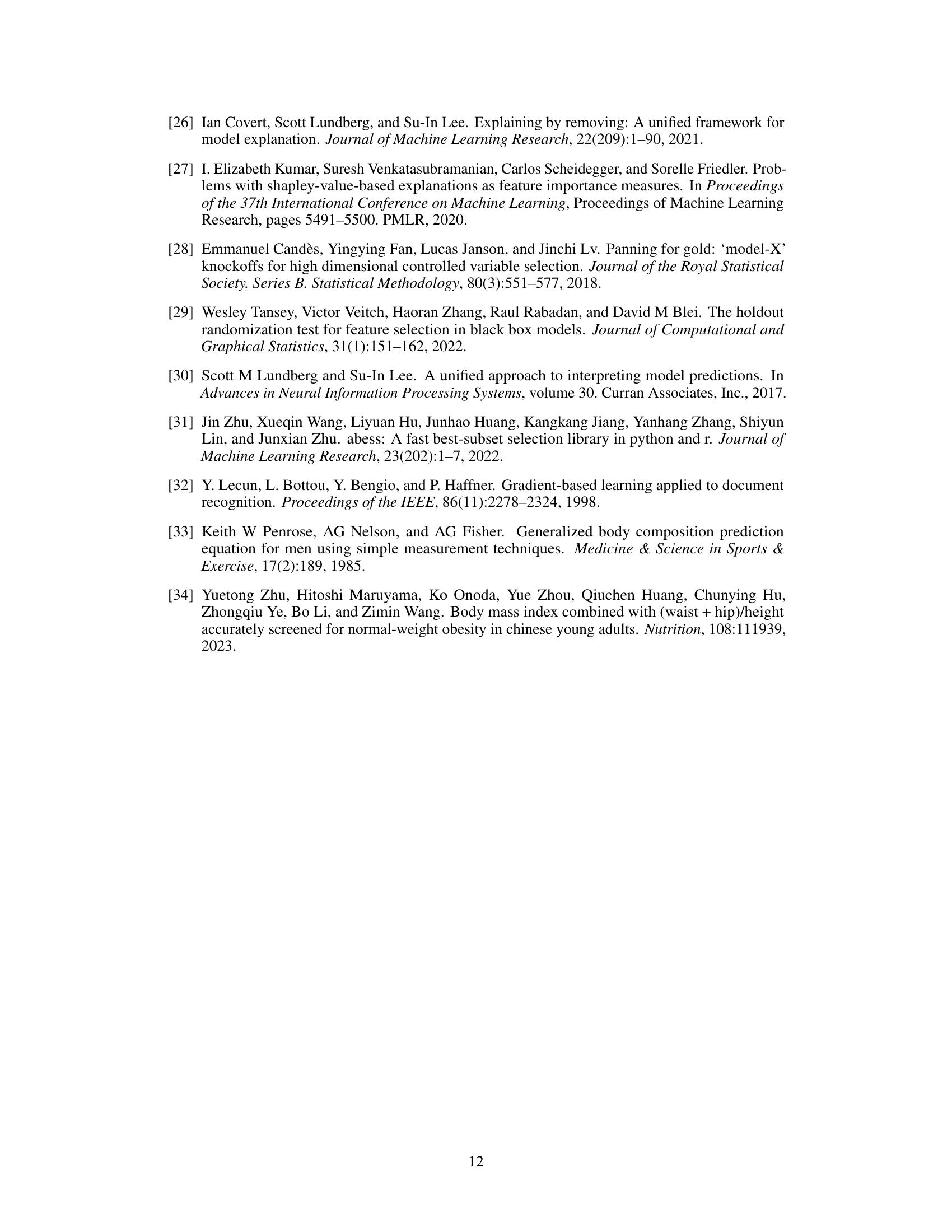

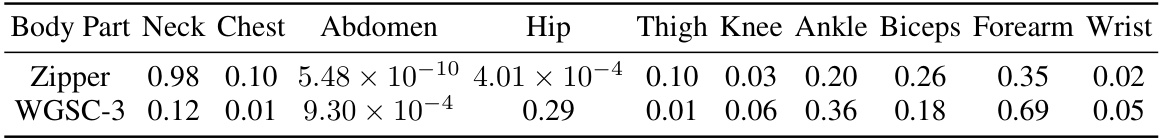

This table presents the p-values resulting from marginal variable importance tests for each body circumference variable in the bodyfat dataset. Two methods are compared: the proposed Zipper method and the WGSC-3 method (a benchmark). The p-values indicate the statistical significance of each body part’s contribution to predicting body fat percentage, considering the influence of other variables like age, weight, and height.

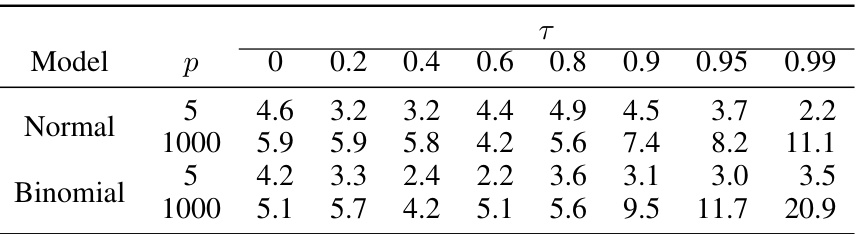

This table presents the empirical sizes of the Zipper method for various values of the slider parameter (τ) when the sample size is 500. The empirical size represents the percentage of times the null hypothesis (H0) is incorrectly rejected when it is actually true. The table shows that the empirical size remains relatively stable across a wide range of τ values, demonstrating the robustness of the Zipper method. It also shows some size distortion when τ gets very close to 1.

This table shows the empirical power of the Zipper method for different values of the slider parameter (τ) at a significance level of 5%, with a sample size of 500. The power is evaluated for both normal and binomial response models, across low and high-dimensional settings, and for varying effect sizes (δ). Larger values of τ generally lead to higher power.

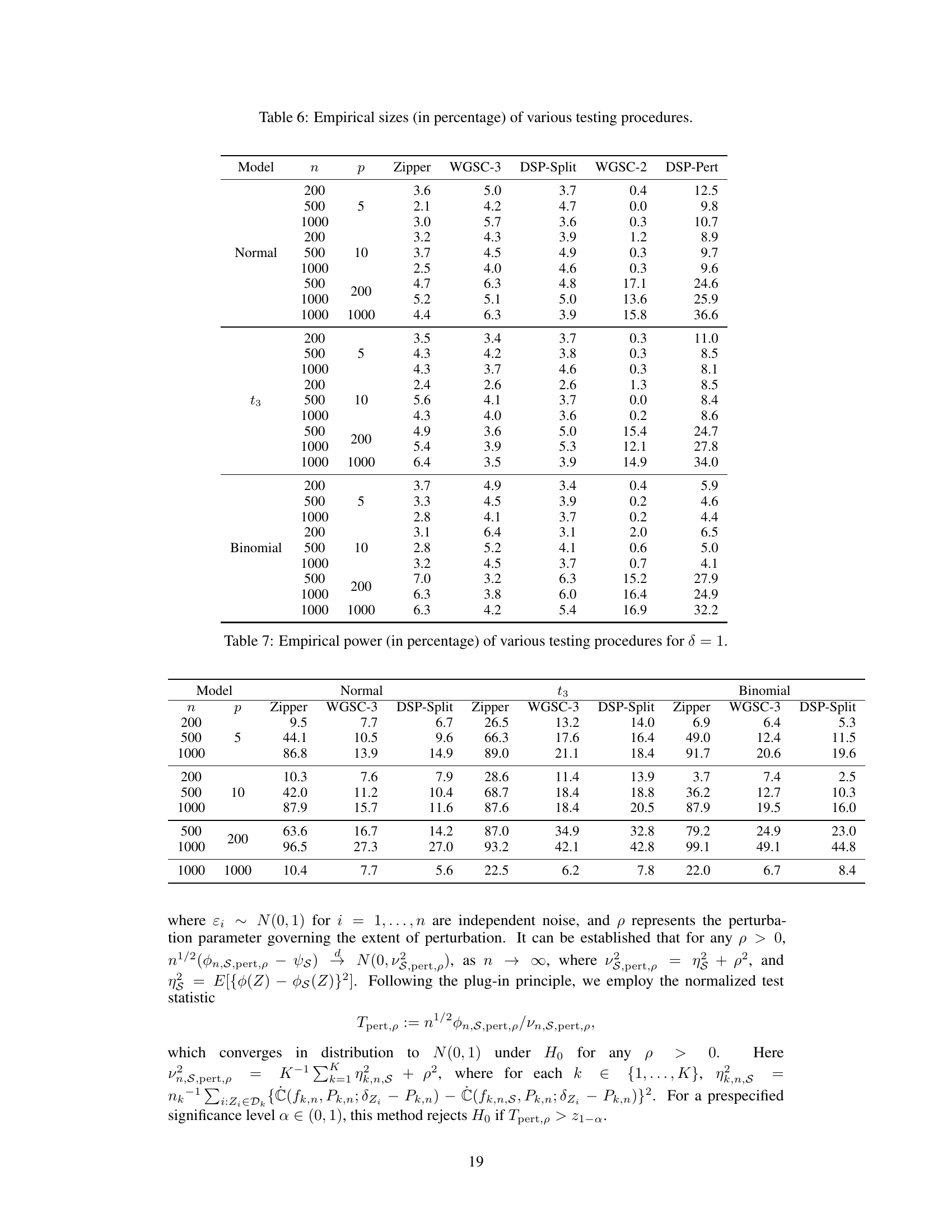

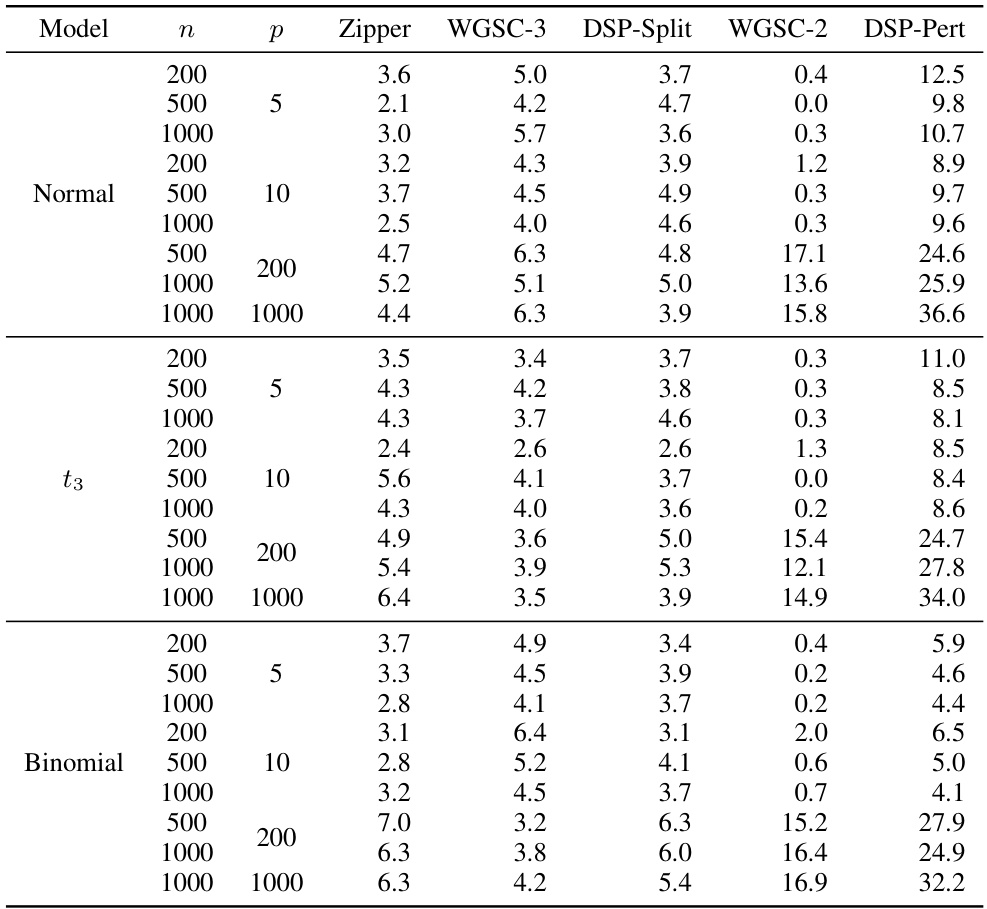

This table presents the empirical Type I error rates (size) for different hypothesis testing procedures in various simulation settings. It compares the proposed Zipper method to several existing methods (WGSC-3, DSP-Split, WGSC-2, DSP-Pert) under different sample sizes (n) and dimensions (p). The models considered include normal, t3 (t-distribution with 3 degrees of freedom), and binomial distributions.

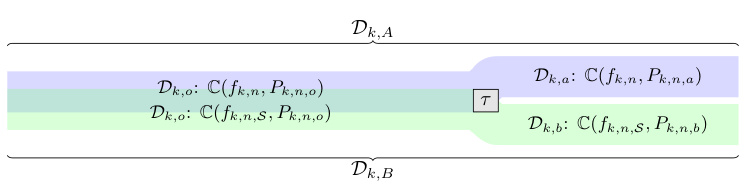

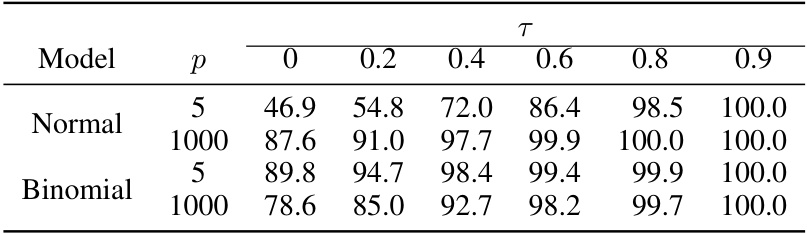

This table shows the empirical power of different testing procedures (Zipper, WGSC-3, DSP-Split) for various sample sizes (n = 200, 500, 1000) and dimensions (p = 5, 10, 200, 1000). The results are presented for three response types (Normal, t3, Binomial). Higher power indicates a greater ability to correctly reject the null hypothesis when it is false. The table helps compare the power of the Zipper method to existing methods.

Full paper#